Submitted:

19 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Determination of Optimum Alkaline Treatment

2.2. Phenotypic Analysis of Alkaline Tolerance-Related Traits

2.3. Population Structure and LD Analysis

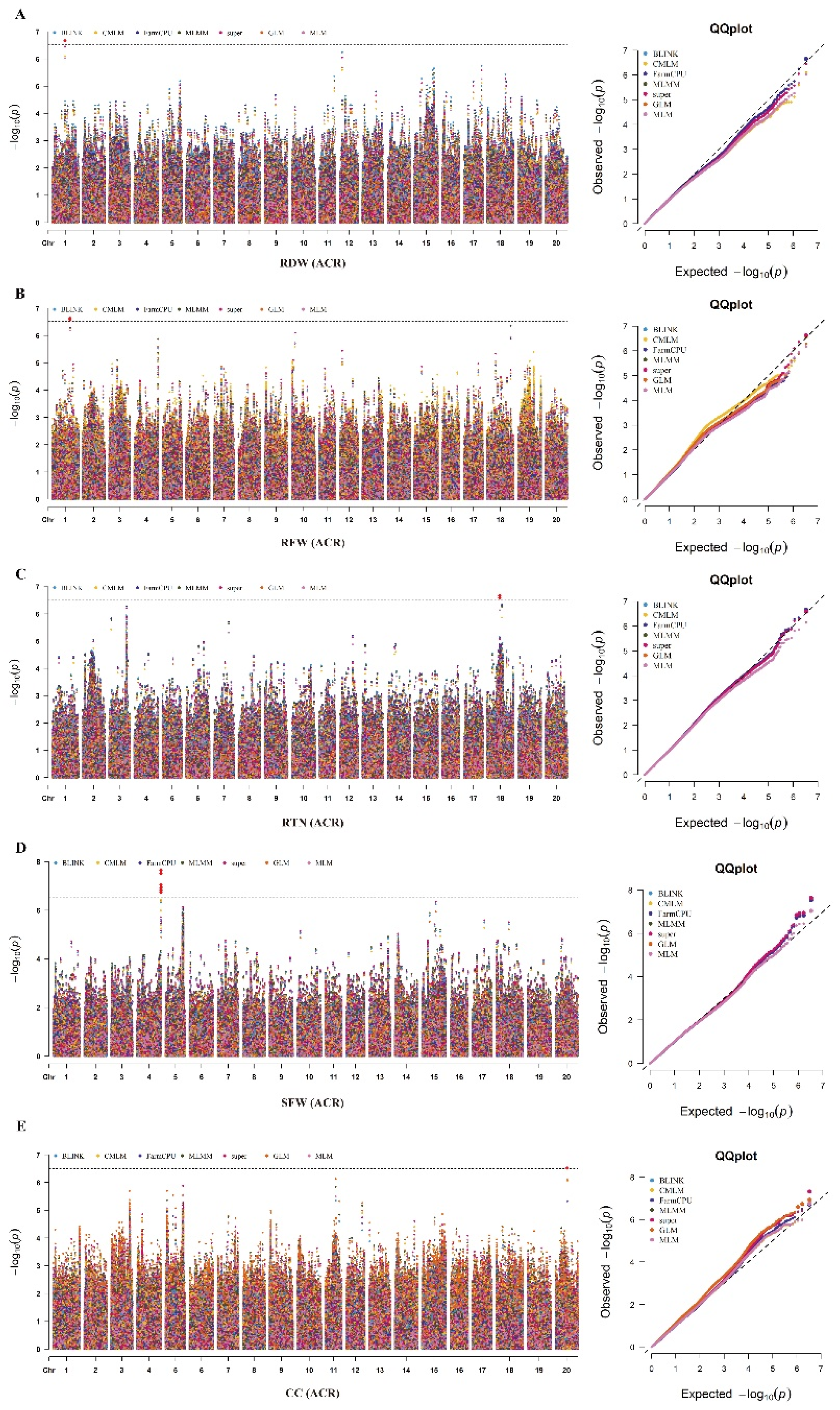

2.4. Association Mapping Analysis of Alkaline Tolerance

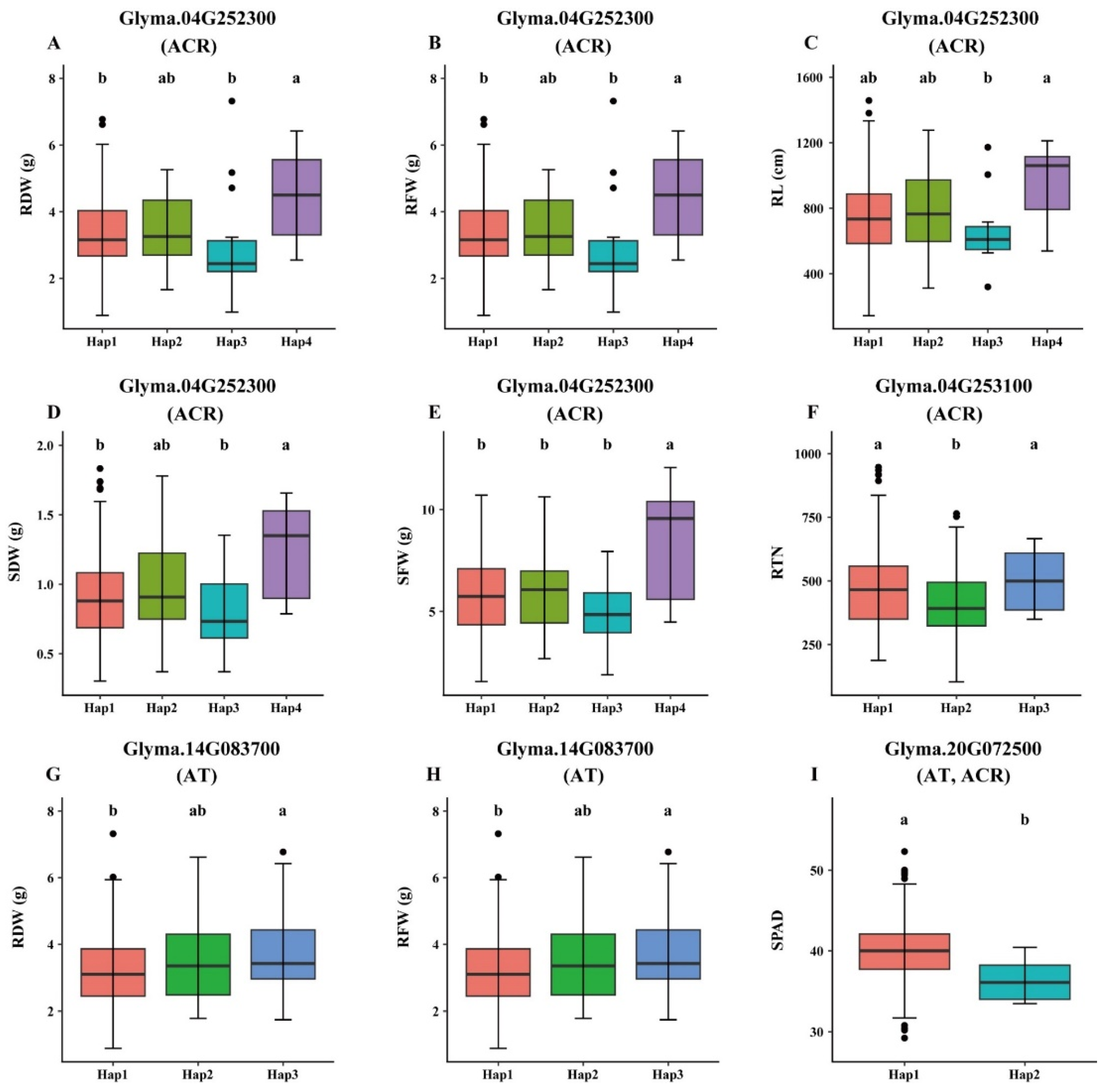

2.5. Candidate Genes Identification

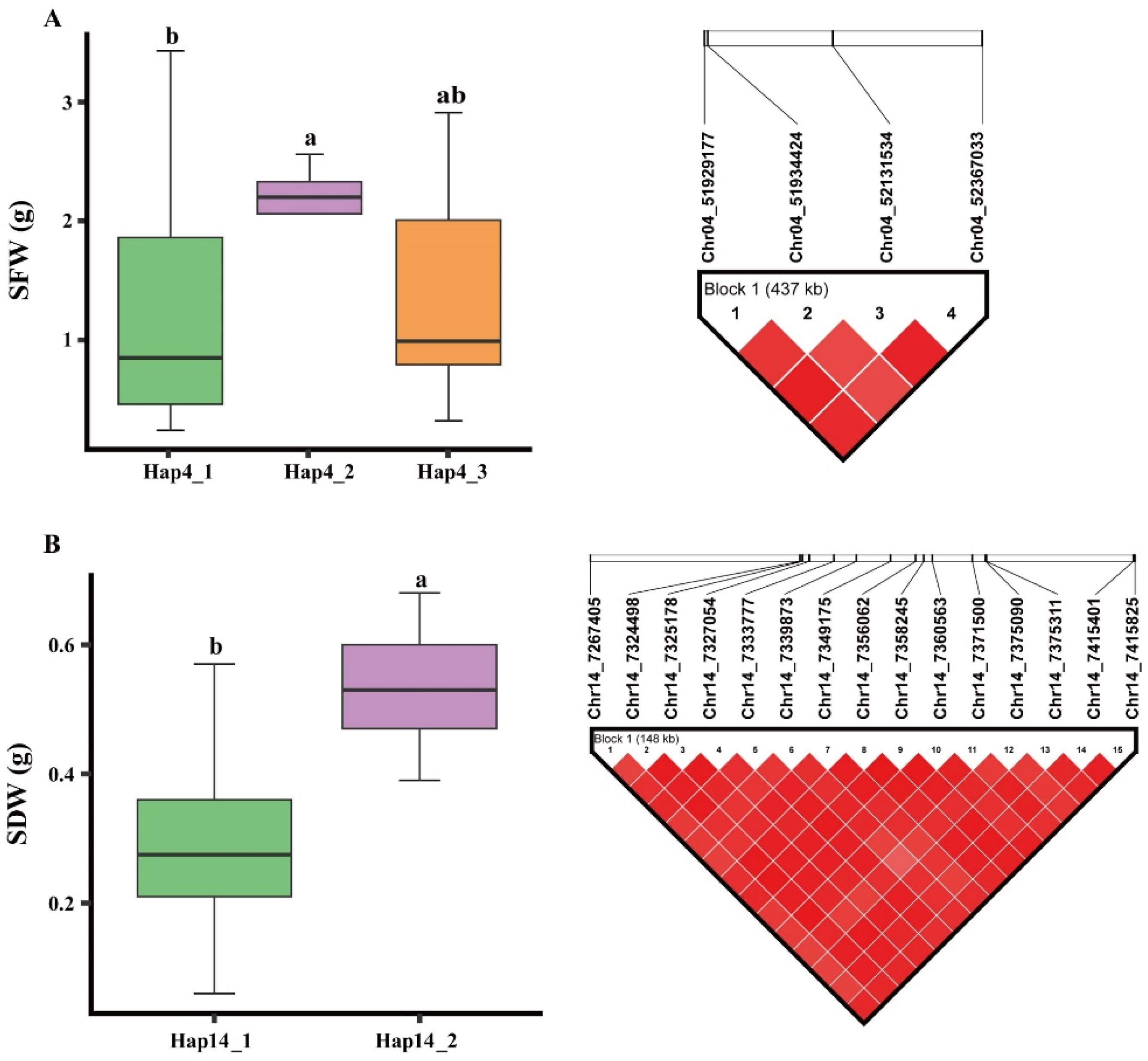

2.6. Haplotypes Identification for Alkaline Tolerance

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Experimental Design

4.2. Phenotypic Data Analysis

4.3. Genotyping, Population Structure and Linkage Disequilibrium (LD)

4.4. GWAS Analysis

4.5. Candidate Genes Identification

4.6. Haplotype Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, H.; Bhat, J.A.; Li, C.; Zhao, B.; Bu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, T.; Feng, X. Identification of superior and rare haplotypes to optimize branch number in soybean. Theor Appl Genet 2024, 137, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapa, S.; Bhandari, A.; Ghimire, R.; Xue, Q.; Kidwaro, F.; Ghatrehsamani, S.; Maharjan, B.; Goodwin, M. Managing Micronutrients for Improving Soil Fertility, Health, and Soybean Yield. Sustainability 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Bhat, J.A.; Li, C.; Zhao, B.; Guo, T.; Feng, X. Genome-wide survey identified superior and rare haplotypes for plant height in the north-eastern soybean germplasm of China. Mol Breeding 2023, 43, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, J.A.; Adeboye, K.A.; Ganie, S.A.; Barmukh, R.; Hu, D.; Varshney, R.K.; Yu, D. Genome-wide association study, haplotype analysis, and genomic prediction reveal the genetic basis of yield-related traits in soybean (Glycine max L.). Frontiers in genetics 2022, 13, 953833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuyen, D.; Lal, S.; Xu, D. Identification of a major QTL allele from wild soybean (Glycine soja Sieb. & Zucc.) for increasing alkaline salt tolerance in soybean. Theor Appl Genet 2010, 121, 229–236. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Nisa, Z.U.; Jin, X.; Jing, L.; Yu, L.; Chen, C. Transcriptional profiling of alkaline stress-induced defense responses in soybean (Glycine max).

- Cai, X.; Jia, B.; Sun, M.; Sun, X. Insights into the regulation of wild soybean tolerance to salt-alkaline stress. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 1002302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Shen, W.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, S.; Hu, J.; Feng, R.; Zhao, Q.; Du, J.; Du, Y. The Effect of Neutral Salt and Alkaline Stress with the Same Na+ Concentration on Root Growth of Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) Seedlings. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, J.A.; Yu, D. High-throughput NGS-based genotyping and phenotyping: Role in genomics-assisted breeding for soybean improvement. Legume Science 2021, 3, e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jia, S.; Karikari, B.; Zhang, M.; Xia, Z.; Zhao, T.; Liang, F. Genome-wide association among soybean accessions for the genetic basis of salinity-alkalinity tolerance during germination. Crop and Pasture Science 2021, 72, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zargar, S.M.; Raatz, B.; Sonah, H.; MuslimaNazir; Bhat, J.A.; Dar, Z.A.; Agrawal, G.K.; Rakwal, R. Recent advances in molecular marker techniques: insight into QTL mapping, GWAS and genomic selection in plants. Journal of crop science and biotechnology 2015, 18, 293–308.

- Bhat, J.A.; Yu, D.; Bohra, A.; Ganie, S.A.; Varshney, R.K. Features and applications of haplotypes in crop breeding. Communications biology 2021, 4, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, D.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Cui, X.; Li, W.; Hao, D.; Yang, Z.; Wu, F. Genetic dissection of ten photosynthesis-related traits based on InDel-and SNP-GWAS in soybean. Theor Appl Genet 2024, 137, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Shao, Z.; Kong, Y.; Du, H.; Li, W.; Yang, Z.; Li, X.; Ke, H.; Sun, Z.; Shao, J. High-quality genome of a modern soybean cultivar and resequencing of 547 accessions provide insights into the role of structural variation. Nat Genet 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Qian, Y.; Bai, D.; Zhao, X.; Bao, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, J. Genome-Wide association analysis reveals the gene loci of yield traits under drought stress at the rice reproductive stage. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, D.; Ali, M.; Shahid, M.; Arif, A.; Waheed, M.Q.; Xia, X.; Trethowan, R.; Tester, M.; Poland, J.; Ogbonnaya, F.C. Genetic networks underlying salinity tolerance in wheat uncovered with genome-wide analyses and selective sweeps. Theor Appl Genet 2022, 135, 2925–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jia, Y.; Zhou, R.; Liu, L.; Cao, M.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Z.; Di, H. GWAS and RNA-seq analysis uncover candidate genes associated with alkaline stress tolerance in maize (Zea mays L.) seedlings. Front Plant Sci 2022, 13, 963874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istanbuli, T.; Nassar, A.E.; Abd El-Maksoud, M.M.; Tawkaz, S.; Alsamman, A.M.; Hamwieh, A. Genome-wide association study reveals SNP markers controlling drought tolerance and related agronomic traits in chickpea across multiple environments. Front Plant Sci 2024, 15, 1260690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breria, C.M.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Yen, T.-B.; Yen, J.-Y.; Noble, T.J.; Schafleitner, R. A SNP-based genome-wide association study to mine genetic loci associated to salinity tolerance in mungbean (Vigna radiata L.). Genes-Basel 2020, 11, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalouf, F.; Abou-Khater, L.; Babiker, Z.; Jighly, A.; Alsamman, A.M.; Hu, J.; Ma, Y.; Rispail, N.; Balech, R.; Hamweih, A. Genetic dissection of heat stress tolerance in faba bean (Vicia faba L.) using GWAS. Plants 2022, 11, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafesse, E.G.; Gali, K.K.; Lachagari, V.R.; Bueckert, R.; Warkentin, T.D. Genome-wide association mapping for heat stress responsive traits in field pea. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Xu, J.; Yuan, Z.; Hao, Z.; Xie, C.; Li, X.; Shah, T.; Lan, H.; Zhang, S.; Rong, T. Comparative LD mapping using single SNPs and haplotypes identifies QTL for plant height and biomass as secondary traits of drought tolerance in maize. Mol Breeding 2012, 30, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’Diaye, A.; Haile, J.K.; Cory, A.T.; Clarke, F.R.; Clarke, J.M.; Knox, R.E.; Pozniak, C.J. Single marker and haplotype-based association analysis of semolina and pasta colour in elite durum wheat breeding lines using a high-density consensus map. Plos One 2017, 12, e0170941. [Google Scholar]

- Luján Basile, S.M.; Ramírez, I.A.; Crescente, J.M.; Conde, M.B.; Demichelis, M.; Abbate, P.; Rogers, W.J.; Pontaroli, A.C.; Helguera, M.; Vanzetti, L.S. Haplotype block analysis of an Argentinean hexaploid wheat collection and GWAS for yield components and adaptation. Bmc Plant Biol 2019, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, G.; Do, T.; Vuong, T.D.; Valliyodan, B.; Lee, J.-D.; Chaudhary, J.; Shannon, J.G.; Nguyen, H.T. Genomic-assisted haplotype analysis and the development of high-throughput SNP markers for salinity tolerance in soybean. Sci Rep-Uk 2016, 6, 19199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Wu, J.; Wang, M.; Shi, W.; Xia, G.; Jia, J.; Kang, Z.; Han, D. Haplotype variations in QTL for salt tolerance in Chinese wheat accessions identified by marker-based and pedigree-based kinship analyses. The Crop Journal 2020, 8, 1011–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koua, A.P.; Siddiqui, M.N.; Heß, K.; Klag, N.; Kambona, C.M.; Duarte-Delgado, D.; Oyiga, B.C.; Léon, J.; Ballvora, A. Genome-wide dissection and haplotype analysis identified candidate loci for nitrogen use efficiency under drought conditions in winter wheat. The Plant Genome 2024, 17, e20394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, T.D.; Vuong, T.D.; Dunn, D.; Clubb, M.; Valliyodan, B.; Patil, G.; Chen, P.; Xu, D.; Nguyen, H.T.; Shannon, J.G. Identification of new loci for salt tolerance in soybean by high-resolution genome-wide association mapping. BMC genomics 2019, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, A.; Chen, P.; Korth, K.; Hancock, F.; Pereira, A.; Brye, K.; Wu, C.; Shi, A. Genome-wide association study (GWAS) of salt tolerance in worldwide soybean germplasm lines. Mol Breeding 2017, 37, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, H.; Gou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Ren, H.; Wen, Z.; Kang, B.-K.; Li, Y.; Yu, L. Genome-wide association study of soybean seed germination under drought stress. Molecular Genetics and Genomics 2020, 295, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Chang, F.; Lv, W.; Sharmin, R.A.; Wang, Z.; Kong, J.; Bhat, J.A.; Zhao, T. Identification of QTN and candidate gene for seed-flooding tolerance in soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] using genome-wide association study (GWAS). Genes-Basel 2019, 10, 957. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Han, D.; Yang, Q.; Li, C.; Shi, X.; Zhang, M.; Yang, C.; Qiu, L.; Jia, H. Cold tolerance SNPs and candidate gene mining in the soybean germination stage based on genome-wide association analysis. Theor Appl Genet 2024, 137, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, C.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, Z.; Qi, Y.; Bai, Y.; Li, W.; Wang, W.; Ren, H. Identification of Gene–Allele System Conferring Alkali-Tolerance at Seedling Stage in Northeast China Soybean Germplasm. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alqudah, A.M.; Sallam, A.; Baenziger, P.S.; Börner, A. GWAS: fast-forwarding gene identification and characterization in temperate cereals: lessons from barley–a review. Journal of advanced research 2020, 22, 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, J.A.; Karikari, B.; Adeboye, K.A.; Ganie, S.A.; Barmukh, R.; Hu, D.; Varshney, R.K.; Yu, D. Identification of superior haplotypes in a diverse natural population for breeding desirable plant height in soybean. Theor Appl Genet 2022, 135, 2407–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganie, S.A.; Ahammed, G.J. Dynamics of cell wall structure and related genomic resources for drought tolerance in rice. Plant cell reports 2021, 40, 437–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganie, S.A.; Wani, S.H.; Henry, R.; Hensel, G. Improving rice salt tolerance by precision breeding in a new era. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2021, 60, 101996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagervanshi, A.; Geilfus, C.-M.; Kaiser, H.; Mühling, K.H. Alkali salt stress causes fast leaf apoplastic alkalinization together with shifts in ion and metabolite composition and transcription of key genes during the early adaptive response of Vicia faba L. Plant Science 2022, 319, 111253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, Y. How do plants maintain pH and ion homeostasis under saline-alkali stress? Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1217193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, H.-H.; Liu, W.-C.; Zhang, X.-W.; Lu, Y.-T. Ethylene inhibits root elongation during alkaline stress through AUXIN1 and associated changes in auxin accumulation. Plant Physiology 2015, 168, 1777–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Song, H.; Zhang, L. New insight into plant saline-alkali tolerance mechanisms and application to breeding. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 16048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Hou, X.; Liang, X. Response mechanisms of plants under saline-alkali stress. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 667458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Li, J.; Hao, R.; Guo, Y. Activation of catalase activity by a peroxisome-localized small heat shock protein Hsp17. 6CII. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 2017, 44, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Yin, T.; Zhang, M.; Yang, X.; Wu, J.; Cai, H.; Yang, N.; Li, X.; Wen, K.; Chen, D. Genome-wide identification and expression pattern analysis of the kiwifruit GRAS transcription factor family in response to salt stress. BMC genomics 2024, 25, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Saharin, R.; Hellmann, H.; Mooney, S. Plant E3 ligases and their role in abiotic stress response. Cells 2022, 11, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Q.; Dong, L.; Jiang, L.; Liu, X.; Cheng, P.; Liu, B.; Yu, G. Genome-wide association study and RNA-seq identifies GmWRI1-like transcription factor related to the seed weight in soybean. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1268511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Aligning sequence reads, clone sequences and assembly contigs with BWA-MEM. arXiv preprint 2013, arXiv:1303.3997. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.; et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Dong, S.-S.; Xu, J.-Y.; He, W.-M.; Yang, T.-L. PopLDdecay: a fast and effective tool for linkage disequilibrium decay analysis based on variant call format files. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 1786–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remington, D.L.; Thornsberry, J.M.; Matsuoka, Y.; Wilson, L.M.; Whitt, S.R.; Doebley, J.; Kresovich, S.; Goodman, M.M.; Buckler IV, E.S. Structure of linkage disequilibrium and phenotypic associations in the maize genome. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 2001, 98, 11479–11484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Z. GAPIT version 3: boosting power and accuracy for genomic association and prediction. Genomics, Proteomics and Bioinformatics 2021, 19, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, A.L.; Patterson, N.J.; Plenge, R.M.; Weinblatt, M.E.; Shadick, N.A.; Reich, D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 2006, 38, 904–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Pressoir, G.; Briggs, W.H.; Vroh Bi, I.; Yamasaki, M.; Doebley, J.F.; McMullen, M.D.; Gaut, B.S.; Nielsen, D.M.; Holland, J.B. A unified mixed-model method for association mapping that accounts for multiple levels of relatedness. Nat Genet 2006, 38, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Ersoz, E.; Lai, C.-Q.; Todhunter, R.J.; Tiwari, H.K.; Gore, M.A.; Bradbury, P.J.; Yu, J.; Arnett, D.K.; Ordovas, J.M. Mixed linear model approach adapted for genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 2010, 42, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Tian, F.; Pan, Y.; Buckler, E.S.; Zhang, Z. A SUPER powerful method for genome wide association study. Plos One 2014, 9, e107684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Huang, M.; Fan, B.; Buckler, E.S.; Zhang, Z. Iterative usage of fixed and random effect models for powerful and efficient genome-wide association studies. PLoS genetics 2016, 12, e1005767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Summers, R.M.; Zhang, Z. BLINK: a package for the next level of genome-wide association studies with both individuals and markers in the millions. Gigascience 2019, 8, giy154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; De Bakker, P.I.; Daly, M.J. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. The American journal of human genetics 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.C.; Fry, B.; Maller, J.; Daly, M.J. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 2005, 21, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, S.B.; Schaffner, S.F.; Nguyen, H.; Moore, J.M.; Roy, J.; Blumenstiel, B.; Higgins, J.; DeFelice, M.; Lochner, A.; Faggart, M. The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. science 2002, 296, 2225–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trait | Treatment | Min | Max | Mean±SE | Median | SD | CV% | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFW | CK | 0.89 | 7.32 | 3.35±0.06 | 3.16 | 1.09 | 32.54 | 0.56 | 0.28 |

| AT | 0.15 | 3.47 | 1.36±0.03 | 1.28 | 0.66 | 48.53 | 0.50 | -0.31 | |

| ACR | 0.04 | 1.33 | 0.42±0.01 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 47.62 | 0.98 | 1.57 | |

| RDW | CK | 0.08 | 2.07 | 0.27±0.01 | 0.26 | 0.13 | 48.15 | 7.98 | 106.01 |

| AT | 0.01 | 0.31 | 0.10±0.03 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 60.00 | 0.57 | -0.31 | |

| ACR | 0.04 | 2.38 | 0.41±0.01 | 0.37 | 0.26 | 63.41 | 2.24 | 10.48 | |

| SFW | CK | 1.56 | 12.06 | 5.90±0.11 | 5.77 | 1.95 | 33.05 | 0.49 | -0.12 |

| AT | 0.24 | 3.43 | 1.26±0.04 | 1.03 | 0.82 | 65.08 | 0.51 | -1.04 | |

| ACR | 0.04 | 1.04 | 0.22±0.01 | 0.18 | 0.14 | 63.64 | 1.29 | 2.77 | |

| SDW | CK | 0.3 | 1.83 | 0.91±0.02 | 0.88 | 0.30 | 32.97 | 0.58 | 0.13 |

| AT | 0.06 | 0.75 | 0.31±0.01 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 38.71 | 0.71 | 0.04 | |

| ACR | 0.10 | 1.11 | 0.36±0.01 | 0.34 | 0.15 | 41.67 | 1.34 | 3.33 | |

| RN | CK | 406.33 | 4269.33 | 2108.10±39.78 | 2030.50 | 718.17 | 34.07 | 0.29 | -0.26 |

| AT | 79.00 | 1666.33 | 587.59±18.58 | 505.16 | 335.61 | 57.12 | 0.78 | -0.08 | |

| ACR | 0.03 | 1.41 | 0.29±0.01 | 0.26 | 0.17 | 58.62 | 1.86 | 6.58 | |

| RL | CK | 143.85 | 1457.82 | 742.17±12.58 | 734.00 | 227.12 | 30.60 | 0.25 | -0.20 |

| AT | 41.37 | 621.99 | 248.98±6.72 | 226.25 | 121.32 | 48.73 | 0.59 | -0.36 | |

| ACR | 0.04 | 1.52 | 0.35±0.01 | 0.32 | 0.17 | 48.57 | 1.56 | 5.66 | |

| RTN | CK | 103.33 | 947.00 | 449.18±8.35 | 434.83 | 150.85 | 33.58 | 0.65 | 0.43 |

| AT | 61.00 | 534.00 | 204.29±4.26 | 199.83 | 77.06 | 37.72 | 0.55 | 0.33 | |

| ACR | 0.09 | 1.82 | 0.49±0.01 | 0.47 | 0.22 | 44.90 | 1.35 | 4.54 | |

| CC | CK | 29.22 | 52.33 | 39.95±0.21 | 39.98 | 3.87 | 9.69 | 0.11 | 0.19 |

| AT | 1.49 | 39.74 | 14.75±0.56 | 15.07 | 10.17 | 68.95 | 0.20 | -1.32 | |

| ACR | 0.04 | 0.98 | 0.36±0.01 | 0.38 | 0.24 | 66.67 | 0.19 | -1.30 |

| No. | Trait name | Significant SNPs | Chr | Pos | P Value | -log10(P) | Environment | Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RDW | Chr01_27555224 | 1 | 27555224 | 2.1839E-07 | 6.660769 | ACR | BLINK, FarmCPU |

| 2 | RFW | Chr01_38897254 | 1 | 38897254 | 2.3509E-07 | 6.628773 | ACR | MLMM, super, CMLM |

| 3 | RTN | Chr01_40473337 | 1 | 40473337 | 2.15E-07 | 6.667484 | AT | GLM |

| 4 | RTN | Chr01_41287221 | 1 | 41287221 | 2.40E-07 | 6.620192 | AT | GLM |

| 5 | RTN | Chr03_3442272 | 3 | 3442272 | 1.12E-07 | 6.952593 | AT | GLM |

| 6 | RTN | Chr18_27591088 | 18 | 27591088 | 2.1329E-07 | 6.671026 | ACR | BLINK, FarmCPU, MLMM, super |

| 7 | SDW | Chr02_4704111 | 2 | 4704111 | 4.56E-09 | 8.340861 | AT | BLINK, GLM |

| 8 | SDW | Chr14_7267405 | 14 | 7267405 | 2.15E-07 | 6.66829 | AT | GLM |

| 9 | SDW | Chr14_7324498 | 14 | 7324498 | 3.07E-07 | 6.513436 | AT | GLM |

| 10 | SDW | Chr14_7325178 | 14 | 7325178 | 3.02E-07 | 6.519871 | AT | GLM |

| 11 | SDW | Chr14_7327054 | 14 | 7327054 | 1.81E-07 | 6.7432 | AT | GLM |

| 12 | SDW | Chr14_7333777 | 14 | 7333777 | 2.96E-07 | 6.528176 | AT | GLM |

| 13 | SDW | Chr14_7339873 | 14 | 7339873 | 2.20E-07 | 6.6578 | AT | GLM |

| 14 | SDW | Chr14_7349175 | 14 | 7349175 | 5.78E-08 | 7.238409 | AT | GLM, BLINK |

| 15 | SDW | Chr14_7356062 | 14 | 7356062 | 2.29E-07 | 6.639446 | AT | GLM |

| 16 | SDW | Chr14_7358245 | 14 | 7358245 | 3.14E-07 | 6.502806 | AT | GLM |

| 17 | SDW | Chr14_7360563 | 14 | 7360563 | 2.09E-07 | 6.680071 | AT | GLM |

| 18 | SDW | Chr14_7371500 | 14 | 7371500 | 2.24E-07 | 6.649972 | AT | GLM |

| 19 | SDW | Chr14_7375090 | 14 | 7375090 | 9.43E-08 | 7.025661 | AT | GLM |

| 20 | SDW | Chr14_7375311 | 14 | 7375311 | 1.91E-07 | 6.720077 | AT | GLM |

| 21 | SDW | Chr14_7415401 | 14 | 7415401 | 1.55E-07 | 6.808744 | AT | GLM |

| 22 | SDW | Chr14_7415825 | 14 | 7415825 | 2.04E-07 | 6.69001 | AT | GLM |

| 23 | SDW | Chr15_10563710 | 15 | 10563710 | 1.02E-07 | 6.991182 | AT | BLINK |

| 24 | SFW | Chr04_51929177 | 4 | 51929177 | 2.2452E-08 | 7.648745 | ACR | BLINK, FarmCPU, MLMM, super, GLM, MLM, CMLM |

| 25 | SFW | Chr04_51934424 | 4 | 51934424 | 1.1781E-07 | 6.928811 | ACR | MLMM, super, BLINK, FarmCPU |

| 26 | SFW | Chr04_52131534 | 4 | 52131534 | 1.4328E-07 | 6.843804 | ACR | MLMM, super, BLINK, FarmCPU |

| 27 | SFW | Chr04_52367033 | 4 | 52367033 | 1.1385E-07 | 6.943677 | ACR | MLMM, super, BLINK, FarmCPU |

| 28 | CC | Chr20_25660093 | 20 | 25660093 | 8.432E-08 | 7.07407 | AT, ACR | MLMM, super, GLM, MLM, CMLM |

| No. | Gene ID | Arabidopsis ortholog | Gene function Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Glyma.01G113400 | AT4G00430 (plasma membrane intrinsic protein 1B) | Response to salt stress, response to temperature stimulus, response to water deprivation and water transport |

| 2 | Glyma.04G251900 | AT4G08250 (GRAS family transcription factor) | Regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent |

| 3 | Glyma.04G252100 | AT4G36020 (cold shock domain protein 1) | Response to cold, response to salt stress and response to water deprivation |

| 4 | Glyma.04G252300 | AT1G77690 (like AUX1 3) | Response to UV light, auxin polar transport, brassinosteroid biosynthetic process, response to auxin stimulus, response to cyclopentenone, root cap development and root hair elongation. |

| 5 | Glyma.04G252500 | AT4G08210 (Pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR-like) superfamily protein) | Biological process |

| 6 | Glyma.04G252600 | AT1G75710 (C2H2-like zinc finger protein) | NA |

| 7 | Glyma.04G252700 | AT1G77720 (PPK1, putative protein kinase 1) | DNA methylation, protein autophosphorylation and protein phosphorylation |

| 8 | Glyma.04G253000 | AT4G08180 (OSBP(oxysterol binding protein)-related protein 1C) | Abscisic acid mediated signaling pathway, response to cold, response to ethylene stimulus and systemic acquired resistance |

| 9 | Glyma.04G253100 | AT1G21980 (phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase 1) | Phosphatidylinositol metabolic process |

| 10 | Glyma.14G083700 | AT1G46264 (heat shock transcription factor B4) | Response to abiotic stress and response to heat |

| 11 | Glyma.14G083900 | AT1G45976 (S-ribonuclease binding protein 1) | biological process; hormone-mediated signaling pathway; photoperiodism, flowering; signal transduction |

| 12 | Glyma.14G084500 | AT4G34110 (poly(A) binding protein 2) | Response to salt stress |

| 13 | Glyma.18G150300 | AT5G10530 (Concanavalin A-like lectin protein kinase family protein) | Protein phosphorylation |

| 14 | Glyma.20G072500 | AT5G55830 (Concanavalin A-like lectin protein kinase family protein) | Protein phosphorylation |

| 15 | Glyma.20G072600 | AT5G03540 (exocyst subunit exo70 family protein A1) | Auxin transport, hyperosmotic response, protein localization involved in auxin polar transport, response to salt stress, response to temperature stimulus, root development and root hair elongation |

| 16 | Glyma.20G072700 | AT5G03540 (exocyst subunit exo70 family protein A1) | Auxin transport, hyperosmotic response, protein localization involved in auxin polar transport, response to salt stress, response to temperature stimulus, root development and root hair elongation |

| 17 | Glyma.20G072900 | AT5G03540 (exocyst subunit exo70 family protein A1) | Auxin transport, hyperosmotic response, protein localization involved in auxin polar transport, response to salt stress, response to temperature stimulus, root development and root hair elongation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).