Introduction

Tourism has become a key driver of economic development for many regions, including South Borneo, one of the provinces of Indonesia. Tourism plays a significant role in the Indonesian economy, contributing significantly to national economic growth in 2022, reaching 5.31% and 4.1% of the Gross Domestic Product value (Hendriyani, 2023). Tourism foreign exchange increased drastically from 0.52 billion US dollars in 2021 to 4.26 billion US dollars in 2022 (Hendriyani, 2023).

However, tourism growth often comes with significant environmental challenges, particularly waste management. According to the National Waste Management Information System, South Borneo generated 803,794.32 tons of waste in 2023 (Banjarmasin.tribunnews.com, 2024). This alarming figure highlights the urgent need for effective waste management strategies in regional tourist destinations. One of the South Borneo tourist destinations is Batakan Baru Beach. The beach has experienced a decline in visitors since 2019, primarily attributed to persistent waste management issues. In response to this challenge, various environmentally conscious groups, including law enforcement agencies, have initiated clean-up efforts to restore the beach’s appeal and address the growing waste problem. Addressing this issue requires more than policy initiatives; it necessitates a fundamental shift in public behavior and engagement with environmental practices.

Moreover, integrating behavioral theories into environmental management has emerged as a promising strategy for promoting sustainable practices. Previous studies have applied Environmental Psychology, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991), and the Norm Activation Theory (NAT) (Schwartz, 1977) to understand and influence waste management behaviors (e.g., Adjei et al., 2023; Babazadeh et al., 2023; de Leeuw et al., 2015; Diaz Ruiz & Nilsson, 2023; Heidari et al., 2018; Z. Liu et al., 2022; Lou et al., 2024; Oh & Ki, 2023; Schultz, 2000; Wu et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2023). The theoretical frameworks provide valuable insights into the drivers of individual and collective actions, offering guidance for more effective waste management interventions in ecotourism contexts.

Theoretical Framework

Environmental psychology in waste management focuses on understanding the psychological and behavioral factors influencing waste sorting, recycling, and sustainable waste disposal practices. For example, Jiang et al. (2020) examined the impact of psychological factors, such as guilt and the anticipation of social rewards, on residents’ low-carbon consumption behaviors, thereby enriching the understanding of waste management practices. Similarly, Hu and He (2022) analyzed how cultural values and anticipated guilt influence rural Chinese residents’ willingness to adopt household waste disposal practices, offering insights through an Environmental Psychology framework. Lou et al. (2024) extended this investigation by employing the expanded Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) to explore further the behavioral drivers of low-carbon practices in waste management.

Another study applied a socio-psychological framework that combined personal norms and TPB to predict waste management behavior (Wu et al., 2022). It was found that personal norms, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control strongly influenced pro-environmental actions like recycling. The TPB has been extensively applied to explore pro-environmental behaviors such as recycling, reduction of plastic consumption, and sustainable waste management in diverse populations, including university students and households.

Research integrating the TPB often examines how attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control influence intentions and actual waste management behaviors. Earlier studies, such as those by Guagnano et al. (1995), Stern, Dietz et al. (1995), and Stern, Kalof et al. (1995), have demonstrated the utility of the TPB in understanding recycling behaviors. These studies identified that attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and subjective norms are critical factors in shaping intentions to manage waste effectively. Further studies have also demonstrated the efficacy of TPB in predicting recycling behaviors and reducing plastic usage (e.g., Hasan et al., 2020; Heidari et al., 2018; Tonglet et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2022).

Recent studies on waste management using TPB have explored various aspects of sustainable waste practices and behavioral intentions across diverse contexts. For instance, studies have applied TPB to predict household recycling behaviors, such as pharmaceutical waste recycling in China (Xu et al., 2023). Research in Iran also applied TPB to explore waste separation behaviors, demonstrating the theory’s efficacy in understanding pro-environmental behavior in different cultural settings (Babazadeh et al., 2023). These investigations demonstrate TPB’s versatility in explaining and promoting responsible waste management practices in many countries and cultures.

In addition, integrating personal norms from the Norm Activation Theory (NAT) has been instrumental in understanding moral obligations and their role in fostering pro-environmental actions (e.g., Harland et al., 1999). This perspective, often linked to altruistic behaviors, highlights the significance of personal responsibility in shaping waste management practices. For instance, de Leeuw et al. (2015) applied NAT alongside TPB to identify key beliefs and norms driving pro-environmental actions in educational settings, which has important implications for developing interventions to promote sustainable behavior.

Recent studies on waste management have increasingly utilized NAT to better understand pro-environmental behaviors, such as waste sorting. For example, a study by Setiawan et al. (2021) demonstrated that subjective and personal norms significantly influenced waste sorting behavior without relying on intention, suggesting that internalized norms can powerfully drive pro-environmental actions. Another study by Oh and Ki in 2023 extended the application of NAT by exploring how individuals’ awareness of environmental consequences influenced their support for environmentally responsible organizations, further highlighting the relevance of NAT in waste management and broader environmental responsibility contexts. The studies indicated that targeting normative beliefs could be a more effective strategy for encouraging responsible waste management than focusing solely on intentions or attitudes (Oh & Ki, 2023; Setiawan et al., 2021). The theoretical foundation for perceived environmental quality, attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control as key determinants of environmentally responsible behavior appears well-established and coherent (e.g., Liu et al., 2019).

Another study examined pro-environmental behavior using the TPB and Stern’s Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) Model, showing that personal moral norms significantly drive recycling and other waste management activities (Z. Liu et al., 2022). Investigations utilizing Environmental Psychology and related theories explore how psychological and social factors influence pro-environmental actions. For instance, Gkargkavouzi et al. (2019) integrated TPB with the VBN, emphasizing the role of self-identity and habit in shaping environmental behavior in private settings, and Adjei et al. (2023) employed NAT, which examines personal norms and awareness of consequences. Gkargkavouzi et al. conducted their research in Greece, focusing on general environmental behaviors in the European context, while Adjei focused on waste management behavior in Ghana, providing insight into waste management in a developing country. These studies highlight the complex interplay between cognitive, normative, and control beliefs in promoting sustainable waste management. They underscore the importance of integrating psychological theories to develop more effective waste management strategies.

The current study explores how these theoretical frameworks can be applied to develop more effective, community-driven strategies for reducing waste and fostering a cleaner, more sustainable tourism environment in South Borneo. By integrating principles from Environmental Psychology, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), and the Norm Activation Theory (NAT), this approach seeks to create a more profound, intrinsic motivation for environmental stewardship in South Borneo’s tourism sector. We follow Wilson’s idea of consilience (1999), which is particularly relevant in advancing this integrated framework because it encourages the breakdown of disciplinary silos, allowing for a holistic understanding of how human behavior interacts with environmental systems. For instance, environmental psychology’s focus on the individual’s interaction with the physical environment complements TPB, which focuses on social and cognitive factors, while norm activation theory bridges the moral dimension of behavior. Together, these theories provide a multi-faceted view of how individuals can be motivated to engage in pro-environmental behavior in tourist destinations like South Borneo.

We propose the concept of “Self-Social Engineering” (SSE) in the context of tourism environmental management. Self-social engineering involves individuals taking active roles in reshaping their behavior and the behavior of others within their social networks to promote sustainable environmental practices. The consilient approach strengthens the foundation of SSE by drawing on psychological, behavioral, and moral insights to create a more robust and dynamic model for driving sustainable tourism practices.

SSE can be seen as aligned with the concept of moral obligation as described in the Norm Activation Theory (NAT), which emphasizes internalizing moral norms as the basis for pro-social behaviors, such as environmental responsibility. NAT, proposed by Schwartz (1977), suggests that individuals are driven to act pro-social when they recognize a moral obligation and perceive that their actions can alleviate a perceived need or threat. In waste management, self-social engineering—where social transformation is driven from within the community—can reflect these moral imperatives. Communities that foster internal moral obligations toward environmental stewardship engage in actions that reflect a shared ethical responsibility, similar to the mechanism described by NAT.

This alignment between SSE and moral obligation can be further supported by empirical studies, such as those by Stern et al. (1999) and Schultz (2000), which suggest that activating personal norms is a significant predictor of environmental behavior. These personal norms, often driven by moral imperatives, catalyze behaviors that align with community-driven initiatives such as SSE, where individuals are motivated by internalized moral values to engage in sustainable practices. In essence, SSE mirrors NAT’s moral obligation concept, as both emphasize the power of internal motivations—driven by personal and collective ethical responsibility—in fostering pro-social behaviors like environmental conservation.

The advantage of self-social engineering over the concept of moral obligation lies in its proactive, dynamic approach. While moral obligation emphasizes an internal sense of duty or ethical responsibility to engage in environmentally responsible behavior, self-social engineering actively involves individuals in reshaping not only their actions but also influencing the behaviors of others within their social networks. This creates a ripple effect, fostering a collective shift toward sustainable practices. By leveraging social influence, self-social engineering has the potential to create more immediate and widespread changes in behavior, moving beyond personal conviction to drive broader environmental impact.

Self-Social Engineering

The concept of social engineering was coined by Marken in 1894 (Eisenhauer, 2019), who introduced the idea of changing people’s behavior with social engineering. However, this term began gaining widespread attention in information security through Mitnick’s work in the 1990s (Ahluwalia, 2023) on psychological manipulation to access computer systems. Later, Pound, a legal scholar in the early 20th century, also contributed to understanding this concept in the context of law and social sciences (Laksito & Bawono, 2024). Furthermore, social engineering has developed into an interdisciplinary concept, such as community empowerment for environmental conservation, where psychological manipulation techniques are used to motivate environmentally friendly behavior and promote awareness of environmental issues.

Social engineering is often characterized as a form of external domination over a community, leading not to empowerment but rather to social exploitation. In such cases, the community is positioned as an object, with the outcomes primarily serving the interests of external actors intervening in local affairs. In contrast, the concept of self-social engineering (SSE) with community empowerment has been explored in previous research, particularly within the framework of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programs (e.g., Sumardjo et al., 2022). However, these initiatives remain largely influenced by corporate intervention in the community.

The literature review reveals a significant gap in the research on social engineering at the individual level, particularly within the context of pro-environmental behavior. This gap highlights the need for further investigation into self-social engineering (SSE) as a critical component of sustainable ecotourism practices. This current study focuses on social engineering driven by the volunteerism of tourists, which positions individuals as active agents of social reform, thereby shifting the emphasis to their role as development subjects.

While social engineering involves exerting influence on others, it is also possible to socially engineer oneself (Rowles, 2023). Social engineering traditionally involves influencing the behavior of others, but the concept of applying it to oneself, particularly in the context of fostering environmentally responsible behavior, presents a novel approach. Pretexts—believable narratives designed to influence a target’s actions—are commonly used in social engineering. For instance, in a vishing campaign, one might impersonate an IT specialist to gain a target’s trust and elicit sensitive information. Success in such endeavors often requires the social engineer to believe in their pretext, thus projecting authenticity.

Similarly, self-social engineering can be applied to influence personal behavior. By crafting internal narratives, individuals can motivate themselves to act in ways that align with desired goals. For example, an introverted individual tasked with a public-facing role might overcome anxiety by mentally adopting the persona of a seasoned professional, thereby enhancing their confidence. This technique could be adapted to promote environmentally responsible behavior, with individuals creating internal stories that position them as environmental stewards, actively influencing their choices and actions.

By leveraging psychological insights, self-social engineering facilitates personal growth and empowers individuals to reshape their behavior in service of broader environmental goals. Understanding and manipulating one’s psychological processes can thus be a powerful tool for fostering sustainable practices.

We believe SSE is more robust than the moral obligation concept in explaining pro-environmental behavior because it integrates multiple factors that influence behavior rather than relying solely on moral or ethical considerations. SSE involves a broader approach that includes personal habits, social norms, incentives, and individual goals. It recognizes that a combination of internal motivations, social influences, and practical considerations influences pro-environmental behavior. SSE allows individuals to design their environments and routines to support sustainable behavior. SSE acknowledges the influential role of social norms and peer influence. It can involve strategies like public commitments or community-based programs that reinforce positive behavior, making it more likely to be sustained. Moral obligation tends to be more individualistic, focusing on personal ethical beliefs. It can be less effective in changing behavior if individuals are not embedded in a social context that supports these beliefs.

SSE is more robust than the moral obligation in NAT because it takes a holistic view of what drives behavior, combining moral, social, and practical elements. It recognizes that pro-environmental behavior is complex and multifaceted, requiring more than just a sense of moral duty to be effectively promoted and sustained.

The current study is critical in developing a foundational framework for the concept of self-social engineering within the context of ecotourism in the wetland environments of South Borneo. Self-social engineering refers to a process of social transformation that originates within, is driven by, and serves the community (Sumardjo et al., 2022; Sumardjo & Dharmawan, 2022). This approach is most effective when it harnesses and strengthens the community’s internal creative social energy, which includes shared values, innovative ideas, and social bonds.

In this case, tourism actors must increasingly emphasize motivation factors and environmentally responsible behavior (ERB) because the facts show that each stakeholder is working alone (Hasan & Aziz, 2024).

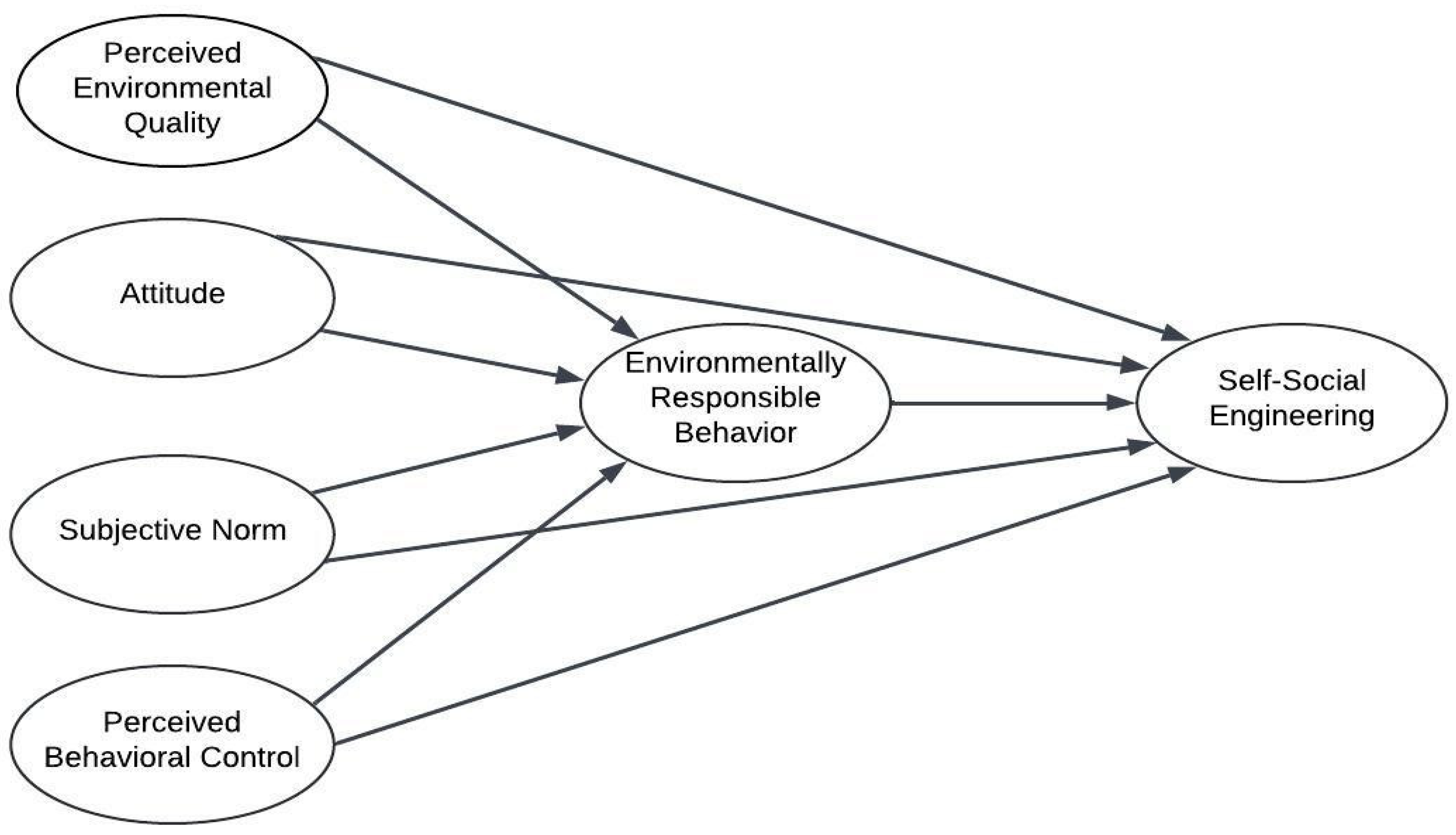

Figure 1 shows the theoretical framework of the current study. As shown in

Figure 1, motivational factors represented by perceived environmental quality, attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and ERB are important variables that increase self-awareness in nature conservation.

Wetland ecotourism has the potential to attract local and international tourists but requires public awareness of nature conservation (Rahmah et al., 2023), and it is crucial to understand the factors influencing consumers towards ecotourism experiences (Negacz et al., 2021). Motivation to travel is directly related to tourist behavior, and motivation drives individuals into goal-oriented behavioral activities (Sharpley, 2006).

The tourism experience in South Borneo consists of two categories: nature tourism and religious tourism (Prihatiningrum et al., 2024). However, studies on the social engineering of South Borneo wetland ecotourism are still minimal, and there have been no specific studies on Motivation, ERB, and self-social engineering.

Discussion

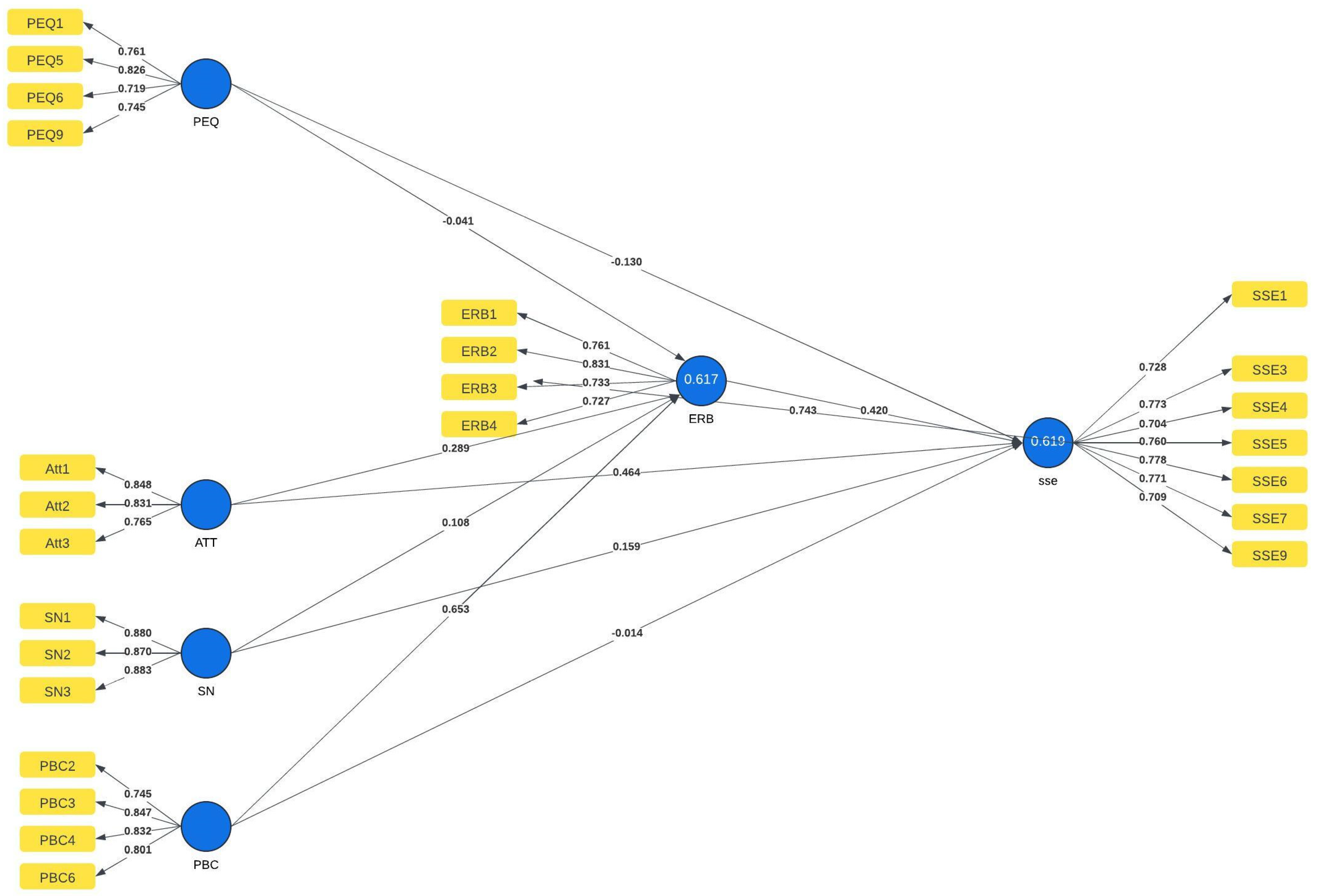

Self-social engineering is a concept that describes the efforts of individuals or groups to actively change their behavior and habits by applying psychological and social principles. This concept emphasizes the active role of individuals in creating positive change in society (Hadnagy, 2010). This study attempts to develop the idea of Self-Social Engineering in the field of tourism environment by combining Environmental Psychology Theory (Gifford, 2007) on Perceived Environment Quality, the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991) on Attitude, Subjective Norm, Perceived Behavioral Control, and Environmentally Responsible Behavior intention as Norm Activation Theory perspective (Schwartz, 1977) on Self Social Engineering.

Based on this study, Environmental Psychology Theory (Gifford, 2007), the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991), and Norm Activation Theory (Schwartz, 1977) can be combined into the concept of Self-Social Engineering in the field of tourism environment. The integration of the Environmental Psychology Theory (Gifford, 2007) is shown through the significant influence of perceived environmental quality on self-social engineering. Furthermore, the significant impact of attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control on self-social engineering is the integration of the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991) and Environmentally Responsible Behavior (Borden & Schettino, 1979).

The implementation of the development of the Self-Social Engineering concept in the field of tourism environment can be done through the improvement of moral obligation. Moral obligation is a demand or calling from within a person to act following ethical values that are believed to be true. This personal commitment is to do good, right, and fair things, regardless of legal rules or social sanctions. Moral obligation improvement can be made through attitude improvement engineering and Perceived behavioral control.

Moral obligation improvement can be done through Attitude improvement engineering. Attitude improvement engineering can be done by cultivating the principle that maintaining the tourism environment is a good and wise action. Good attitudes and deeds bring rewards, and wisdom can make others joyful.

Perceived behavioral control improvement engineering can also increase moral obligation. Perceived behavioral control is a person’s belief about how easy or difficult it is to do a particular action. Simply put, this is an individual’s perception of their ability to control behavior. Perceived behavioral improvement engineering can be done by increasing concern by having resources and time to be involved in environmental protection in tourist attractions.

Recommendations

This study opens up opportunities for further development of the concept of Self-Social Engineering (SSE) in the context of tourism. By understanding the psychological factors that influence behavior, we can design more effective intervention programs to change tourist behavior. This study can be a starting point for further research on other factors influencing tourists’ pro-environmental behavior, such as cultural, social, and economic influences. Tourism managers should develop environmental education programs emphasizing the importance of moral obligation in preserving the tourism environment. This program can include campaigns highlighting moral values and personal responsibility to behave pro-environmentally. Tourism managers should ensure the availability of resources, such as information, tools, and time, that make it easy for visitors to engage in environmental protection actively. This can be done by providing easily accessible facilities for recycling, clear information about conservation efforts, and opportunities for visitors to engage in environmental activities that have a real impact.

Conclusion

This study makes an important contribution to developing the concept of self-social engineering in tourism. By understanding the psychological mechanisms underlying pro-environmental behavior, more effective interventions can be designed to encourage tourists to behave more responsibly towards the tourism environment.

This study successfully integrated Environmental Psychology Theory, Theory of Planned Behavior, and Norm Activation Theory into the concept of Self-Social Engineering in the field of tourism environment. The significant influence of Perceived Environmental Quality on Self-Social Engineering and the role of Attitude, Subjective Norm, and Perceived Behavioral Control in forming Self-Social Engineering shows that the three theories can be effectively combined to create environmentally responsible behavior.

The study results indicate that Self-Social Engineering is critical in encouraging pro-environmental behavior. In other words, awareness of the moral obligation to maintain the tourism environment can be the primary driver for tourists to behave responsibly.

Increasing moral obligation by engineering attitude through cultivating positive values related to preserving the tourism environment can form a more positive attitude towards pro-environmental behavior. In addition, increasing perceived behavioral control by providing adequate support and resources can increase tourists’ confidence to carry out pro-environmental actions.