Submitted:

19 November 2024

Posted:

21 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. INTRODUCTION

3. MATERIAL AND METHODS

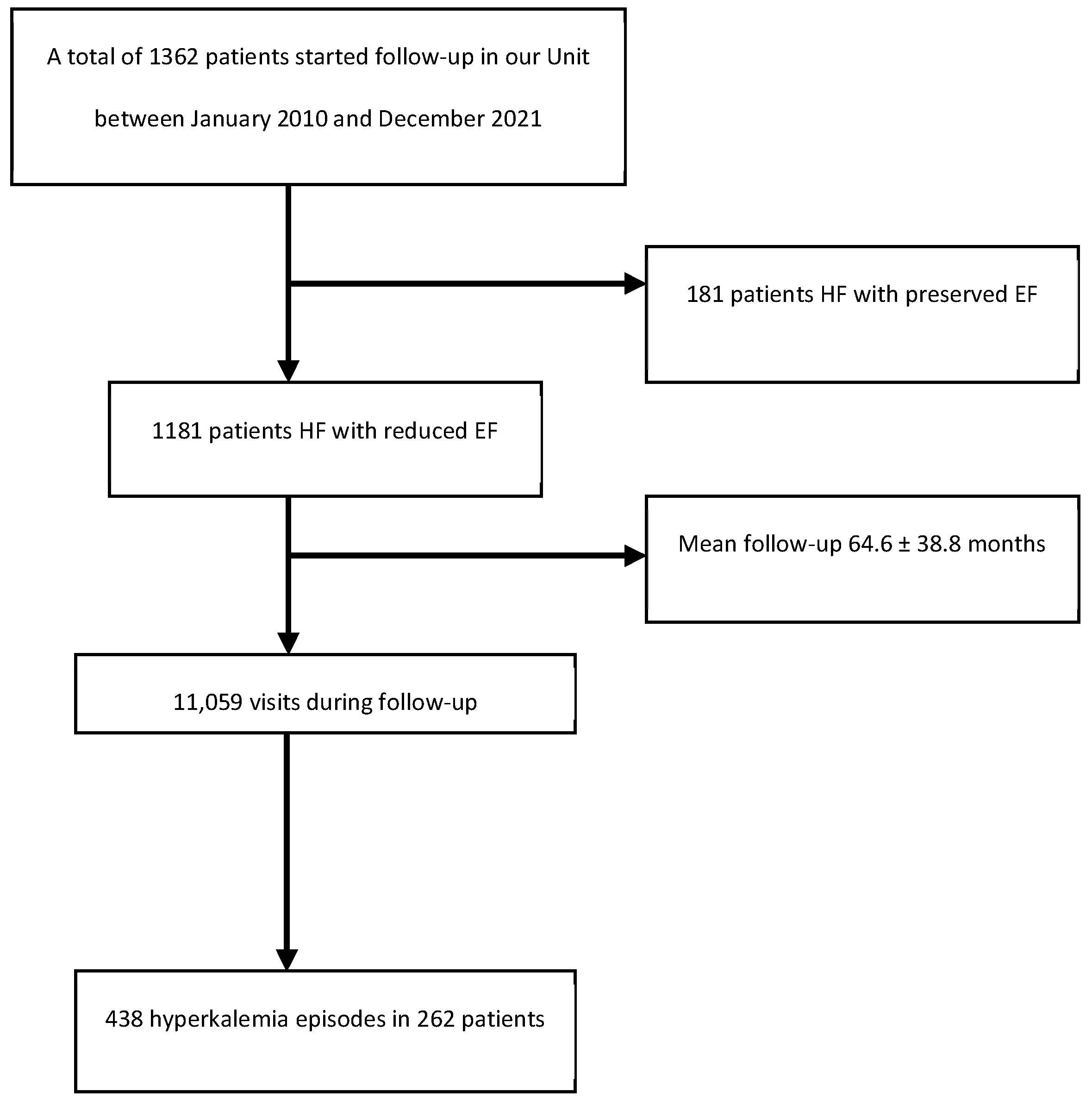

3.1. Study Design and Screening Criteria

3.2. Intervention and Data Collection

3.3. Ethical Particulars

3.4. Statistical Analysis

4. RESULTS

4.1. Baseline and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Sample

4.2. Management of Hyperkalemia and Need for Medical Care

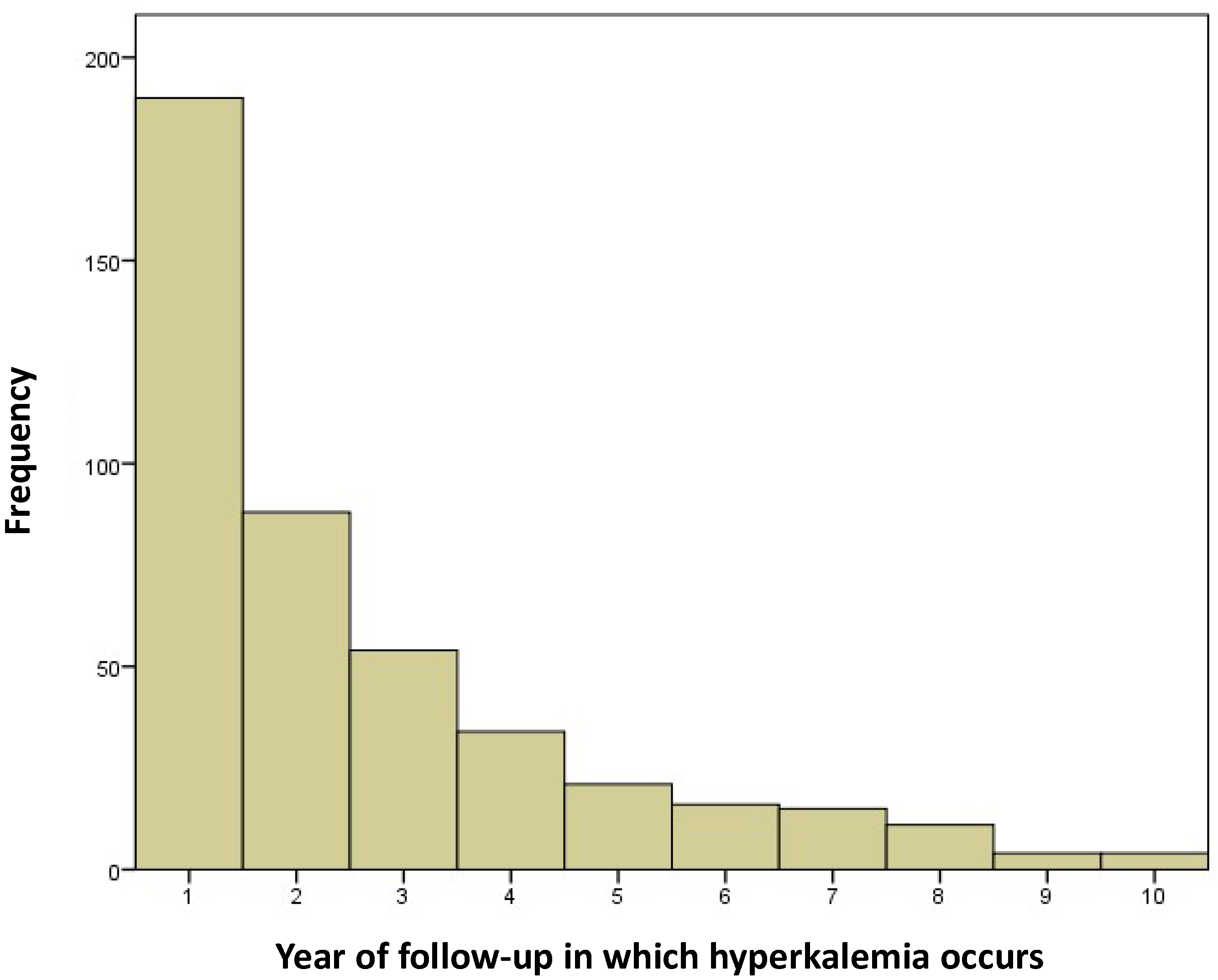

4.3. Hyperkalemia Episodes During the First Year of Follow-Up

4.4. Resource Utilization and Associated Costs

5. DISCUSSION

6. CONCLUSIONS

7. STUDY LIMITATIONS

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Crespo-Leiro MG, Barge-Caballero E, Segovia-Cubero J, González-Costello J, López-Fernández S, García-Pinilla JM, et al. Hyperkalemia in heart failure patients in Spain and its impact on guidelines and recommendations: ESC-EORP-HFA Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Revista Española de Cardiología (English Edition) 2020, 73, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021, 42, 3599–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisch C, Knoebel SB, Feigenbaum H, Greenspan K. Potassium and the monophasic action potential, electrocardiogram, conduction and arrhythmias. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 1966, 8, 387–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorriz JL, D’Marco L, Pastor-González A, Molina P, Gonzalez-Rico M, Puchades MJ, et al. Long-term mortality and trajectory of potassium measurements following an episode of acute severe hyperkalaemia. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2022, 37, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingelfinger, JR. A New Era for the Treatment of Hyperkalemia? New England Journal of Medicine 2015, 372, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes-Austin JM, Rifkin DE, Beben T, Katz R, Sarnak MJ, Deo R, et al. The Relation of Serum Potassium Concentration with Cardiovascular Events and Mortality in Community-Living Individuals. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2017, 12, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarese G, Xu H, Trevisan M, Dahlström U, Rossignol P, Pitt B, et al. Incidence, Predictors, and Outcome Associations of Dyskalemia in Heart Failure With Preserved, Mid-Range, and Reduced Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail 2019, 7, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, AS. Hyperkalemia in patients with heart failure: Incidence, prevalence, and management. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2009, 6, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarwar CMS, Papadimitriou L, Pitt B, Piña I, Zannad F, Anker SD, et al. Hyperkalemia in Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016, 68, 1575–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett H, Earley A, Voors AA, Senni M, McMurray JJV, Deschaseaux C, et al. Thirty Years of Evidence on the Efficacy of Drug Treatments for Chronic Heart Failure With Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circ Heart Fail 2017, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Bao J, Kan R, Chen J, Xuan H, Wang C, Li D, et al. Combination pharmacotherapies for cardiac reverse remodeling in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Pharmacol Res 2021, 169, 105573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir MR, Rolfe M. Potassium Homeostasis and Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Inhibitors. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2010, 5, 531–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouwerkerk W, Voors AA, Anker SD, Cleland JG, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, et al. Determinants and clinical outcome of uptitration of ACE-inhibitors and beta-blockers in patients with heart failure: a prospective European study. Eur Heart J 2017, 38, 1883–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epstein M, Reaven NL, Funk SE, McGaughey KJ, Oestreicher N, Knispel J. Evaluation of the treatment gap between clinical guidelines and the utilization of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. Am J Manag Care 2015, 21 (11 Suppl), S212–S220.

- Rosano GMC, Tamargo J, Kjeldsen KP, Lainscak M, Agewall S, Anker SD, et al. Expert consensus document on the management of hyperkalaemia in patients with cardiovascular disease treated with renin angiotensin aldosterone system inhibitors: coordinated by the Working Group on Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 2018, 4, 180–188. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott MJ, Ronksley PE, Clase CM, Ahmed SB, Hemmelgarn BR. Management of patients with acute hyperkalemia. Can Med Assoc J 2010, 182, 1631–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 2013, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sterns RH, Rojas M, Bernstein P, Chennupati S. Ion-Exchange Resins for the Treatment of Hyperkalemia. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2010, 21, 733–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponikowski A del G de TP, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, et al. Guía ESC 2016 sobre el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la insuficiencia cardiaca aguda y crónica. Rev Esp Cardiol 2016, 69, e1–e1167. [Google Scholar]

- Rosano GMC, Spoletini I, Agewall S. Pharmacology of new treatments for hyperkalaemia: patiromer and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate. European Heart Journal Supplements 2019, 21 (Supplement_A), A28–A33. [CrossRef]

- Anker SD, Kosiborod M, Zannad F, Piña IL, McCullough PA, Filippatos G, et al. Maintenance of serum potassium with sodium zirconium cyclosilicate ( <scp>ZS</scp> -9) in heart failure patients: results from a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2015, 17, 1050–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt B, Bakris GL, Bushinsky DA, Garza D, Mayo MR, Stasiv Y, et al. Effect of patiromer on reducing serum potassium and preventing recurrent hyperkalaemia in patients with heart failure and chronic kidney disease on <scp>RAAS</scp> inhibitors. Eur J Heart Fail 2015, 17, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Thomsen RW, Nicolaisen SK, Hasvold LP, Palaka E, Sørensen HT. Healthcare resource utilisation and cost associated with elevated potassium levels: a Danish population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://www.xunta.gal/dog/Publicados/2014/20140521/AnuncioC3K1-140514-0001_es.html.

- Lopez-López A, Franco-Gutiérrez R, Pérez-Pérez AJ, Regueiro-Abel M, Elices-Teja J, Abou-Jokh-Casas C, et al. Impact of Hyperkalemia in Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction: A Retrospective Study. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Marrero S, Cainzos-Achirica M, Monterde D, Vela E, Cleries M, García-Eroles L, et al. Impact on clinical outcomes and health costs of deranged potassium levels in patients with chronic cardiovascular, metabolic, and renal conditions. Revista Española de Cardiología (English Edition) 2021, 74, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olry de Labry Lima A, Díaz Castro Ó, Romero-Requena JM, García Díaz-Guerra M de los R, Arroyo Pineda V, de la Hija Díaz MB, et al. Hyperkalaemia management and related costs in chronic kidney disease patients with comorbidities in Spain. Clin Kidney J 2021, 14, 2391–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen RW, Nicolaisen SK, Hasvold P, Garcia-Sanchez R, Pedersen L, Adelborg K, et al. Elevated Potassium Levels in Patients With Congestive Heart Failure: Occurrence, Risk Factors, and Clinical Outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc 2018, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Clase CM, Carrero JJ, Ellison DH, Grams ME, Hemmelgarn BR, Jardine MJ, et al. Potassium homeostasis and management of dyskalemia in kidney diseases: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 2020, 97, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House AA, Wanner C, Sarnak MJ, Piña IL, McIntyre CW, Komenda P, et al. Heart failure in chronic kidney disease: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 2019, 95, 1304–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz A, del Arco Galán C, Fernández-García JC, Gómez Cerezo J, Ibán Ochoa R, Núñez J, et al. Documento de consenso sobre el abordaje de la hiperpotasemia. Nefrología 2023, 43, 765–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosano GMC, Tamargo J, Kjeldsen KP, Lainscak M, Agewall S, Anker SD, et al. Expert consensus document on the management of hyperkalaemia in patients with cardiovascular disease treated with renin angiotensin aldosterone system inhibitors: coordinated by the Working Group on Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother 2018, 4, 180–188. [Google Scholar]

- Sterns RH, Rojas M, Bernstein P, Chennupati S. Ion-Exchange Resins for the Treatment of Hyperkalemia. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2010, 21, 733–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir MR, Bakris GL, Bushinsky DA, Mayo MR, Garza D, Stasiv Y, et al. Patiromer in Patients with Kidney Disease and Hyperkalemia Receiving RAAS Inhibitors. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015, 372, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packham DK, Kosiborod M. Potential New Agents for the Management of Hyperkalemia. American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs 2016, 16, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir MR, Bakris GL, Bushinsky DA, Mayo MR, Garza D, Stasiv Y, et al. Patiromer in Patients with Kidney Disease and Hyperkalemia Receiving RAAS Inhibitors. New England Journal of Medicine 2015, 372, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinowitz BS, Fishbane S, Pergola PE, Roger SD, Lerma E V. , Butler J, et al. Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate among Individuals with Hyperkalemia. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2019, 14, 798–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agiro A, AN A, Cook EE, Mu F, Chen J, Desai P, et al. Real-World Modifications of Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Inhibitors in Patients with Hyperkalemia Initiating Sodium Zirconium Cyclosilicate Therapy: The OPTIMIZE I Study. Adv Ther 2023, 40, 2886–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi A, Pollack C V, Sánchez Lázaro IJ, Lesén E, Arnold M, Franzén S, et al. Maintained renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitor therapy with sodium zirconium cyclosilicate following a hyperkalaemia episode: a multicountry cohort study. Clin Kidney J 2024, 17. [Google Scholar]

- https://www.aemps.gob.es/medicamentosUsoHumano/informesPublicos/docs/IPT-patiromer-Veltassa-hiperpotasemia.pdf.

- Sharma A, Alvarez PJ, Woods SD, Fogli J, Dai D. Healthcare resource utilization and costs associated with hyperkalemia in a large managed care population. Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research 2021, 12, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein M, Alvarez PJ, Reaven NL, Funk SE, McGaughey KJ, Brenner MS, et al. Evaluation of clinical outcomes and costs based on prescribed dose level of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. Am J Manag Care 2016, 22 (11 Suppl), s311–s324.

| Characteristics | N = 1181 | |

| Males, n (%) | 913 (77.3%) | |

| Age (years) | 66.6 ± 11.0 | |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 721 (61.0%) | |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 448 (37.9%) | |

| Smoking (ex-smoker and active smoker), n (%) | 631(53.5%) | |

| Alcohol abuse (previous and current consumption: > 2 alcoholic beverage equivalents per day in males and > 1 in females), n (%) | 494(41.8%) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.8 ± 5.1 | |

| NYHA functional class ≥ 2, n (%) | 843 (71.4%) | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 128.2 ± 20.8 | |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 70.2 ± 11.2 | |

| Primary cause, n (%) | ||

| Ischemic | 467 (39.8%) | |

| Idiopathic | 204(17.4%) | |

| Alcoholic | 101 (8.6%) | |

| Tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy | 100 (8.5%) | |

| Hypertensive | 88 (7.5%) | |

| Others | 221(18.2%) | |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 31.5 ± 7.0 | |

| Hematocrit (%) | 41.7 ± 5.3 | |

| Creatinine clearance, MDRD (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 72.0 ± 24.7 | |

| Creatinine clearance < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, n (%) | 371(31.3%) | |

| Basal potassium (mEq/l) | 4.66 ± 0.4 | |

| Basal potassium > 5.5(mEq/l), n (%) | 24 (2.0%) | |

| Treatment (first consultation), n (%) | ||

| ARNi/ACEi/ARBi | 1149 (97.3%) | |

| BB | 1143 (97.8%) | |

| MRAs | 699 (59.1%) | |

| SGLT2i | 132 (11.2%) | |

| Loop diuretics | 703 (67.3%) | |

| Potassium supplements | 2(0.2%) | |

| Drug doses at first consultation (over 1, maximum dose according to ESC guidelines) | ||

| ARNi/ACEi/ARBi | 0.64 ± 0.49 | |

| BB | 0.77 ± 0.34 | |

| MRAs | 0.31 ± 0.26 | |

| Loop diuretics | 0.74 ± 0.77 | |

| Treatment (at 1 year), n (%) | ||

| ARNi/ACEi/ARBi | 955 (97.2%) | |

| BB | 947 (97.8%) | |

| MRAs SGLT2i |

622 (67.3%) 171 (17.4%) |

|

| Loop diuretics | 492 (55.2%) | |

| Drug doses at one year (over 1, maximum dose according to ESC guidelines) | ||

| ARNi/ACEi/ARBi | 0.88 ± 0.56 | |

| BB | 0.80 ± 0.34 | |

| MRAs Loop diuretics |

0.32 ± 0.28 0.63 ± 0.78 |

|

| Item | Health Service assigned cost | Total number | Total cost | Number, first year | Cost, first year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emergency care | €361.59 | 13 | €4700.65 | 8 | €2892.72 |

| Stay in ward (days) | €528.95 | 49 | €25,918.56 |

28 | €14,810.6 |

| Stay in ICU (days) | €1142.48 | 2 | €2284.95 | 0 | 0 |

| Follow-up laboratory test* | €14.52 + €34.52 + €9.91 | 953 | €56,274.65 | 437 | €25,804.85 |

| Total cost | €89,178.83 | €43,508.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).