Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

20 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The State of the Art

1.2. Geographical Area

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Archaeological Approach

2.2. DNA Purification

2.3. Sequencing, Alignment and Quality Control

2.4. Variant Calling

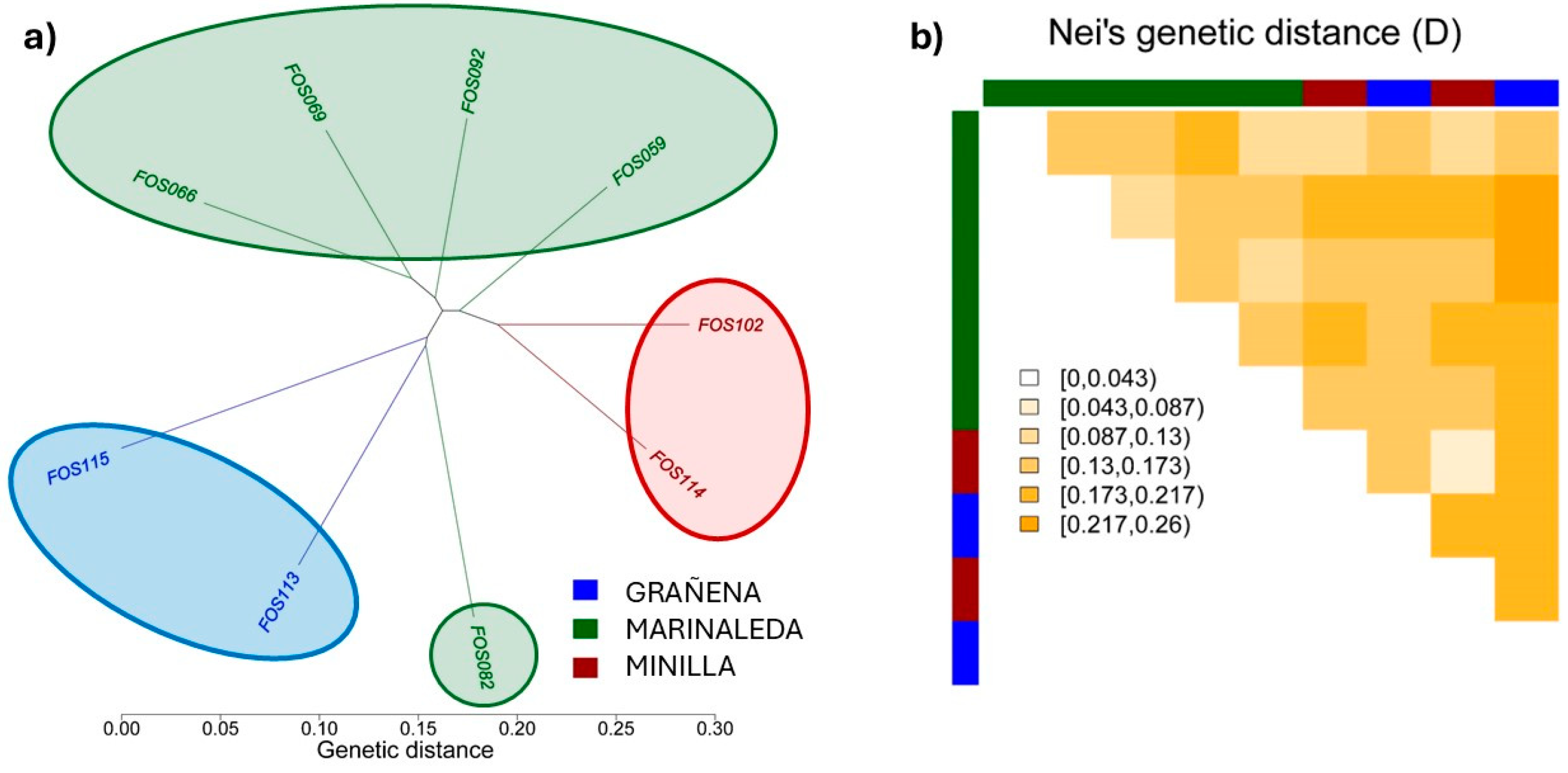

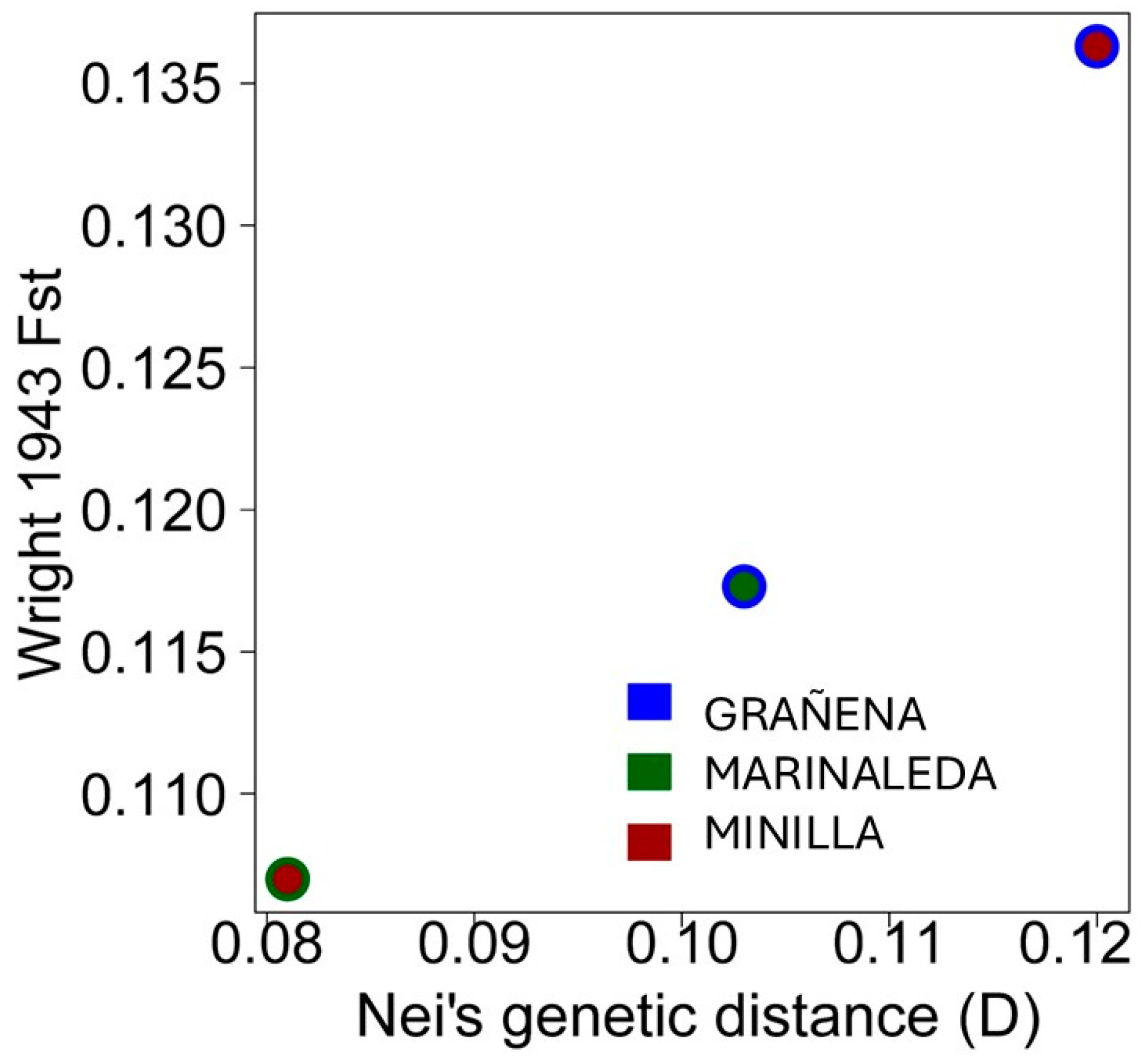

2.5. Genomic Comparison Between Ancient Samples

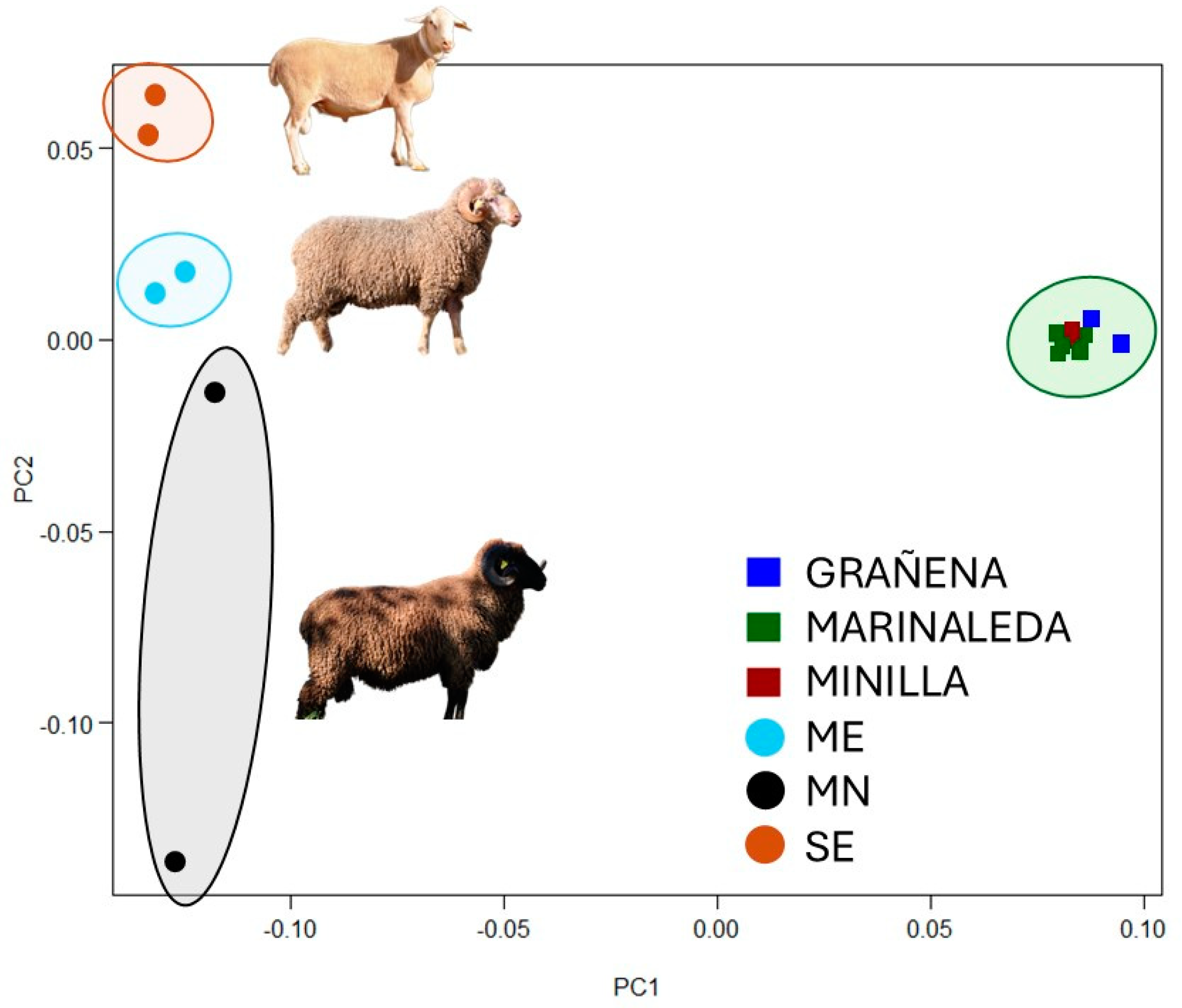

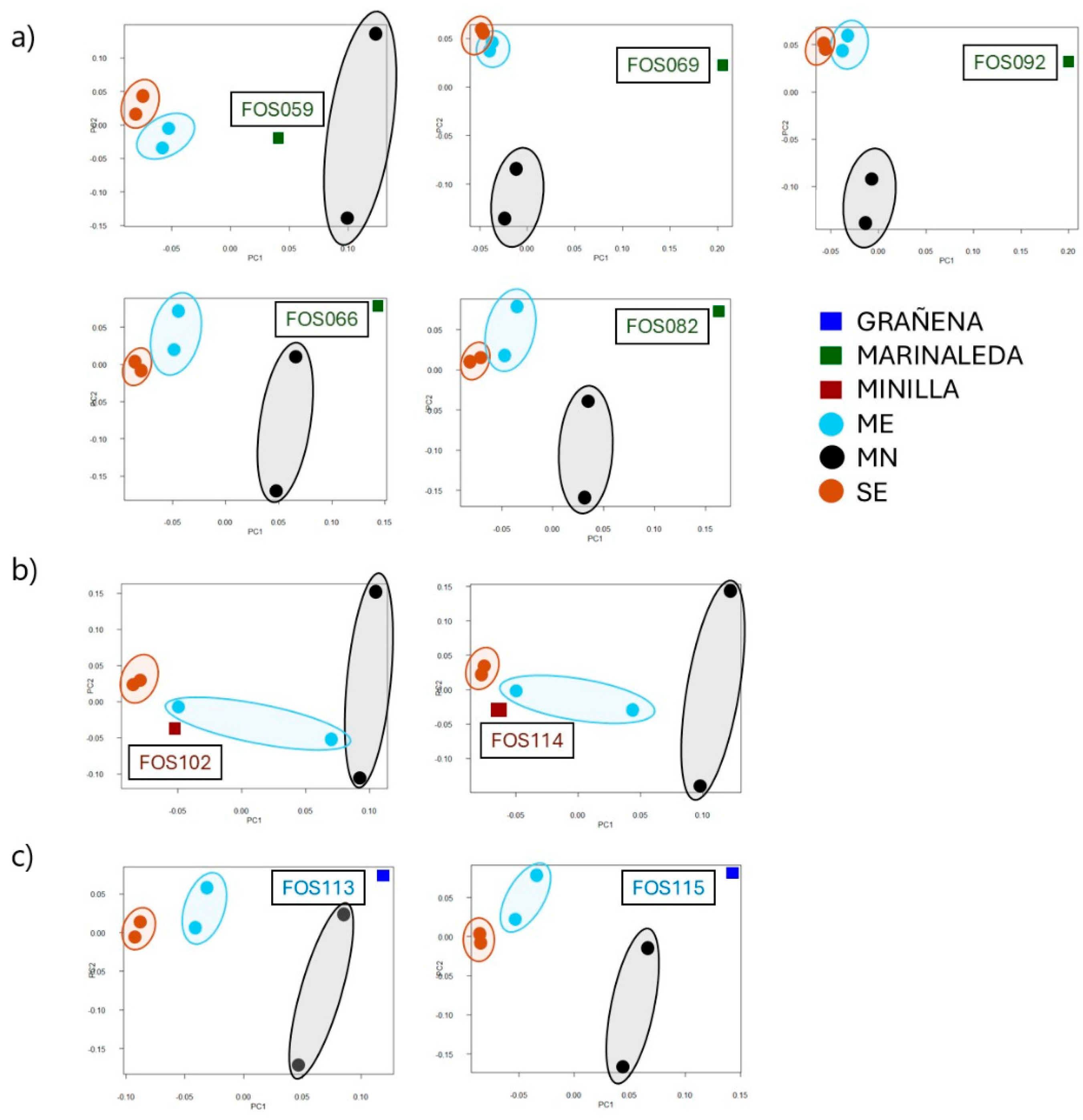

2.6. Genomic Homology with Modern Breeds

3. Results

3.1. Genomic Comparison Between Samples from the Different Sites

3.2. Genomic Comparison Between Ancient Remains and Modern Breeds

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Harrison, R.J.; Moreno Lopez, G. El policultivo ganadero o la revolución de los productos secundarios. Trabajos de Prehistoria 1985, 42, 51.

- Riquelme, J.A.; Calvo, F. Aspectos socioeconómicos basados en el estudio de los restos óseos del yacimiento del III Milenio de Cabezo Juré, Alosno (Huelva). In Proceedings of the II-III simposios de prehistoria Cueva de Nerja, Málaga, 2004; pp. 379-385.

- Martínez, R.M.; Conlin, E.; Delgado, A.; Guijo, M.; Granados, A.; Cámara, J.A. Into the circle. Animal and human deposits in a new Upper Guadalquivir site from the beginning of the 3rd millennium Cal BC (Grañena Baja, Jaén). Archaeofauna 2023, 32 (1), 113-128.

- Caro, J.A.; Cruz-Aúñon, R.; García, L. Excavación de urgencia en el asentamiento de la edad del cobre de Marinaleda (Marinaleda, Sevilla). In Proceedings of the Anuario arqueológico de Andalucía 2001, Sevilla, 2004; pp. 920-928.

- Martínez, R.M.; Ruiz, D. Bones in ditches: animal remains at the Copper Age enclosure of La Minilla (La Rambla, Andalusia) in the middle Guadalquivir Valley. Estudos & Memórias 2022, 77. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, R.M. El IV milenio ANE en el Guadalquivir Medio. Intensificación agrícola y fragua de la comunidad doméstica aldeana; Archaeopress: Oxford, 2013.

- Driesch, A.v.d.; Boessneck, J. Die fauna vom Castro do Zambujal. Studien über frühe Tierknochenfunde von der Iberischen Halbinsel 1976, 5, 4-129.

- Driesch, A.v.d. Osteoarchäologische untersuchungen auf der Iberischen Halbinsel; Uni-Druck Muünchen: Muünchen, 1972.

- Hain, F.H. Kupferzeitliche tierknochenfunde aus Valencina de la Concepción; 1982.

- ANTUNES, M.T. O povoado fortificado calcolítico do Monte da Tumba. IV-Mamíferos (nota preliminar). Setúbal Arqueológica 1987, 8, 103-144.

- Cruz-Auñón, R.; Moreno, E.; Rivero, E. Experiencias arqueológicas en Gilena (Sevilla). In Proceedings of the IInd Deya international conference of prehistory. Recent developments in Western Mediterranean prehistory: archaeological techniques, technology and theory, 1991; pp. 313-337.

- Riquelme, J.A. Contribución al estudio arqueofaunístico durante el Neolítico y la Edad del Cobre en las Cordilleras Béticas: el yacimiento arqueológico de Los Castillejos en Las Peñas de los Gitanos, Montefrío (Granada); Universidad de Granada: Granada, 1996.

- Riquelme, J.A. Informe sobre los restos óseos recuperados en la IAP El Corte Inglés" de Jaén. Historia de un arroyo. De Marroquíes Bajos al Centro Comercial El Corte Inglés de Jaén 2011, 310-331.

- Morales, A.; Riquelme, J.A. Faunas de mamíferos del Neolítico Andaluz. In Proceedings of the II-III simposios de prehistoria Cueva de Nerja, 2004; pp. 41-51.

- Abril, D.; Nocete, F.; Riquelme, J.A.; Bayona, M.; Inacio, N. Zooarqueología del III Milenio A.N.E.: El barrio metalúrgico de Valencina de la Concepción (Sevilla). Complutum 2010, 21, 87-100.

- Costa, C. Tafonomia em contexto pré-histórico: a zooarqueologia como recurso para a compreensão das" estruturas em negativo" da pré-história recente. 2013.

- Pajuelo Pando, A.; López Aldana, P.M. Estudio arqueozoológico de estructuras significativas de c/Mariana de Pineda s/n (Valencina de la Concepción, Sevilla). In Proceedings of the El asentamiento prehistórico de Valencina de la Concepción (Sevilla): Investigación y Tutela en el 150 Aniversario del Descubrimiento de La Pastora, 2013; pp. 445-458.

- Martínez, R.M.; Pérez, G.; Peña-Chocarro, L. La campiña de Córdoba entre el IV y el I milenio ANE. Apuntes sobre la ocupación prehistórica del yacimiento de Torreparedones (Baena-Castro del Río, Córdoba). El sondeo 3, al norte del foro. ANTIQVITAS 2014, 26, 135-153.

- Moreno-García, M. Estudo arqueozoológico dos restos faunísticos do povoado calcolítico do Mercador (Mourão). As sociedades agropastoris na margem esquerda do Guadiana (2ª metade do IV e inícios do II milénio AC), Memórias d’Odiana, 2ª série 2013, 321-349.

- Moreno-Garcia, M.; Sousa, A.C. A exploração de recursos faunísticos no Penedo do Lexim (Mafra) durante o Neolítico Final. In Proceedings of the 5. º Congresso do Neolítico Peninsular. Actas., 2015; pp. 67-76.

- Almeida, N.J.; Texugo, A.; Basilio, A.C. ‘Animal farm’: the faunal record from the Chalcolithic Ota site (Alenquer, Portugal) and its regional significance. Documenta Praehistorica 2022, 49, 124-149. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, N.J.; Valera, A.C. Animal consumption and social change: the vertebrates from Ditch 7 in the context of a diachronic approach to the faunal remains at Perdigöes enclosure (3400-2000 BC). Archaeofauna 2021, 30, 75-106. [CrossRef]

- Iborra Eres, M.P. Caza y animales domésticos en el poblado de Les Moreres: análisis arqueozoológico. In Proceedings of the El poblado calcolítico de Les Moreres (Crevillent, Alicante), 2023; pp. 301-310.

- Rojano Simón, M. Principios de estratigrafía arqueológica y arqueometría. Contrastación y validación empírica en Papa Uvas (Aljaraque, Huelva). 2024.

- Morán, M.E. El asentamiento prehistórico de Alcalar (Portimāo, Portugal). La organización del territorio y el proceso de formación de un Estado prístino en la bahía de Lagos en el tercer milenio A.N.E.; UNIARQ WAPS: Lisboa, 2018; Volume 12.

- Martínez, R.M. Cerdos, caprinos y náyades. Aproximación a la explotación ganadera y fluvial en el Guadalquivir entre el Neolítico y la Edad del Cobre (3500-2200 ane). Spal. Revista de Prehistoria y Arqueología (2013, Vol. 22, p. 29-46) 2013.

- Morales Muñiz, A.; Cereijo Pecharromán, M. Consideraciones faunísticas en la transición Neolítico Final-Calcolítico: el yacimiento arqueológico de Papa Uvas (Huelva). Archaeofauna 1992, 1, 87-104.

- Álvarez, M.; Chaves, P. Informe faunístico del yacimiento de Aljaraque (Huelva). Cortes A- 7. 2 y A- 10.4 del Sector A. In Papa Uvas II. Aljaraque. Huelva. Campañas de 1981 a 1983. , Martín de la Cruz, J., Ed.; Ministerio de Cultura: Madrid, 1986.

- Lizcano Prestel, R.; Cámara Serrano, J.A.; Riquelme Cantal, J.A.; Cañabate Guerrero, M.L.; Sánchez Vizcaíno, A.; Afonso Marrero, J.A. El polideportivo de Martos. Producción económica y símbolos de cohesión en un asentamiento del Neolítico Final en las campiñas del Alto Guadalquivir. Cuadernos de prehistoria y arqueología de la Universidad de Granada 1991, 16, 5-101.

- Cámara Serrano, J.A.; Riquelme Cantal, J.A.; Pérez Bareas, C.; Lizcano Prestel, R.; Burgos Juárez, A.; Torres Torres, F. Sacrificio de animales y ritual en el polideportivo de Martos-La Alberquilla (Martos, Jaén). Cuadernos de Prehistoria y Arqueología de la Universidad de Granada 2012, 20, 295-328. [CrossRef]

- Pando, A.P. Usos pecuarios en la transición del IV al III milenio aC en la Sierra Norte de Sevilla. In Proceedings of the Actas del VII Congreso sobre Neolítico en la península ibérica, 2023; pp. 381-393.

- Antunes, M.T. O povoado fortificado calcolítico do Monte da Tumba IV: mamíferos (nota preliminar). Setúbal Arqueológica 1987, 8, 103-144.

- Riquelme, J.A. Anexo 2. Estudio de los restos óseos de vertebrados procedentes de las excavaciones arqueológicas del Poblado Calcolítico de Alcalar, sectores 15L y 16 L. . In El asentamiento prehistórico de Alcalar (Portimāo, Portugal). La organización del territorio y el proceso de formación de un Estado prístino en la bahía de Lagos en el tercer milenio A.N.E., Morán, M.E., Ed.; Estudios & Memorias; UNIARQ WAPS: Lisboa, 2018; Volume 12, pp. 254-302.

- Riquelme, J.A. Una aproximación a la utilización por el hombre de las especies animales documentadas en la Ciudad de la Justicia de Jaén. Ciudad de la Justicia de Jaén. Excavaciones Arqueológicas 2010, 117-133.

- Peters, J.; Driesch, A.v.d. Archäozoologische untersuchung der tierreste aus der kupferzeitlichen siedlung von Los Millares (Prov. Almeria). 1990.

- Detry, C.; Francisco, A.C.; Diniz, M.; Martins, A.; Neves, C.; Arnaud, J.M. Estudo zooarqueológico das faunas do Calcolítico final de Vila Nova de São Pedro (Azambuja, Portugal): Campanhas de 2017 e 2018. Arqueologia em Portugal 2020-Estado da Questão 2020, 925-941.

- Albarella, U.; Davis, S.; Detry, C.; Rowley-Conwy, P. Pigs of the “Far West”: the biometry of Sus from archaeological sites in Portugal. Anthropozoologica 2005, 40, 27-54.

- Conlin, E.; Mercado, L. Actividad Arqueológica Preventiva de excavación arqueológica extensiva y control de movimiento de tierras: “Proyecto de construcción de la Línea de Alta Velocidad Madrid-Alcázar de San Juan, Tramo Grañena-Jaén. Anuario Arqueológico de Andalucía 2013 2013.

- Ruiz, D. Excavación arqueológica de urgencia en La Minilla (La Rambla, Córdoba). Campaña de 1989. In Anuario arqueológico de Andalucía 89.III; Junta de Andalucia, Spain: Sevilla, 1991; pp. 157-163.

- Reimer, P.J.; Austin, W.E.; Bard, E.; Bayliss, A.; Blackwell, P.G.; Ramsey, C.B.; Butzin, M.; Cheng, H.; Edwards, R.L.; Friedrich, M. The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0–55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon 2020, 62, 725-757.

- Schmid, E. Atlas de huesos de animales Para prehistoriadores, arqueólogos y geólogos del Cuaternario. Knochenatlas. Für prähistoriker, archäologen und quartärgeologen. ; Elsevier: Ámsterdam, Nueva York, 1972.

- Barone, R. Anatomie comparée des mammifères domestiques-ostéologie; Vigot frères éditeurs: París, 1976.

- Rowley-Conwy, P.; Albarella, U.; Dobney, K. Distinguir a los jabalíes de los cerdos domésticos en la prehistoria: una revisión de los enfoques y los resultados recientes. Revista de Prehistoria Mundial 2012, 25, 1-44.

- Reitz, E.; Wing, E. Zooarqueología. Manuales de Arqueología de Cambridge; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2008.

- Grayson, D. Zooarqueología cuantitativa; Elsevier: 1984.

- Boessneck, J.; Müller, H.H.; Teichert, M. Osteologische Unterscheidungsmerkmale zwischen Schaf (Ovis aries Linné) und Ziege (Capra hircus Linné). Kün-Archiv 1964, 78, 1-129.

- Prummel, W.; Frisch, H.-J. A guide for the distinction of species, sex and body side in bones of sheep and goat. Journal of Archaeological Science 1986, 13, 567-577. [CrossRef]

- Halstead, P.; Collins, P.; Isaakidou, V. Sorting the Sheep from the Goats: Morphological Distinctions between the Mandibles and Mandibular Teeth of AdultOvis and Capra. Journal of Archaeological Science 2002, 29, 545-553. [CrossRef]

- Zeder, M.A.; Lapham, H.A. Assessing the reliability of criteria used to identify postcranial bones in sheep, Ovis, and goats, Capra. Journal of Archaeological Science 2010, 37, 2887-2905. [CrossRef]

- Zeder, M.A.; Pilaar, S.E. Assessing the reliability of criteria used to identify mandibles and mandibular teeth in sheep, Ovis, and goats, Capra. Journal of Archaeological Science 2010, 37, 225-242. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.Y.; Eng, B.; Waye, J.S.; Dudar, J.C.; Saunders, S.R. Improved DNA extraction from ancient bones using silica-based spin columns. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 1998, 105, 539-543. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884-i890.

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754-1760. [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.; Davies, R. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 2021, 10, giab008.

- Chang, C.; Chow, C.; Tellier, L.; Vattikuti, S.; Purcell, S.; Lee, J. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. GigaScience 2015, 4. [CrossRef]

- Nei, M. Genetic Distance between Populations. The American Naturalist 1972, 106, 283-292. [CrossRef]

- Pembleton, L.W.; Cogan, N.O.I.; Forster, J.W. StAMPP: an R package for calculation of genetic differentiation and structure of mixed-ploidy level populations. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2013, 13, 946-952. [CrossRef]

- Paradis, E.; Schliep, K. ape 5.0: an environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics 2018, 35, 526-528. [CrossRef]

- de Jong, M.J.; de Jong, J.F.; Hoelzel, A.R.; Janke, A. SambaR: An R package for fast, easy and reproducible population-genetic analyses of biallelic SNP data sets. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2021, 21, 1369-1379.

- Animut, G.; Goetsch, A.L. Co-grazing of sheep and goats: Benefits and constraints. Small Rumin. Res. 2008, 77, 127-145. [CrossRef]

- Miranda-de la Lama, G.C.; Mattiello, S. The importance of social behaviour for goat welfare in livestock farming. Small Rumin. Res. 2010, 90, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Égüez, N.; Zerboni, A.; Biagetti, S. Microstratigraphic analysis on a modern central Saharan pastoral campsite. Ovicaprine pellets and stabling floors as ethnographic and archaeological referential data. Quaternary International 2018, 483, 180-193. [CrossRef]

- Pilaar Birch, S.E.; Scheu, A.; Buckley, M.; Çakırlar, C. Combined osteomorphological, isotopic, aDNA, and ZooMS analyses of sheep and goat remains from Neolithic Ulucak, Turkey. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 2019, 11, 1669-1681. [CrossRef]

- Serjeantson, D. Review of animal remains from the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age of Southern Britain. 2011.

- Basso, R.E. Actividad textil en el asentamiento calcolítico de Les Moreres: Las pesas de telar y los crecientes de las campañas de 1988-1993. In El poblado calcolítico de Les Moreres (Crevillent, Alicante), González Prats, A., Lorrio Alvarado, A.J., Eds.; Universidad de Alicante: Alicante, 2024; pp. 277-300.

- Gleba, M.; Bretones-García, M.D.; Cimarelli, C.; Vera-Rodríguez, J.C.; Martínez-Sánchez, R.M. Multidisciplinary investigation reveals the earliest textiles and cinnabar-coloured cloth in Iberian Peninsula. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 21918.

- Cubas, M.; Lucquin, A.; Robson, H.K.; Colonese, A.C.; Arias, P.; Aubry, B.; Billard, C.; Jan, D.; Diniz, M.; Fernandes, R. Latitudinal gradient in dairy production with the introduction of farming in Atlantic Europe. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1-9.

- Möllers, S. Jungsteinzeit hautnah – Der Flintdolch von Wiepenkathen. In Fundsache: Archäologie zwischen Oste und Elbe, Nösler, D.a.S., A. , Ed.; MCE Verlag in Zusammenarbeit mit der Archäologischen Denkmalpflege des Landkreises Stade und der Stadtarchäologie der Hansestadt Stade.: Drochtersen, 2013; pp. 42-43.

- Prestel, R.L.; Serrano, J.A.C.; Cantal, J.A.R.; Guerrero, M.L.C.; Vizcaíno, A.S.; Marrero, J.A.A. El polideportivo de Martos. Producción económica y símbolos de cohesión en un asentamiento del Neolítico Final en las campiñas del Alto Guadalquivir. Cuadernos de prehistoria y arqueología de la Universidad de Granada 1991, 16, 5-101.

- Cámara, J.A.; Lizcano, R.; Pérez, C.; Gómez del Toro, E. Apropiación, sacrificio, consumo y exhibición ritual de los animales en el Polideportivo de Martos. Sus implicaciones en los orígenes de la desigualdad social. 2008.

- Sherratt, A. Plough and pastoralism: aspects of the secondary products revolution. 1981.

- Sherratt, A. La traction animale et la transformation de l’Europe néolithique. P. Pétrequin 2006, 329-360.

- Davis, S. La arqueología de los animales; Bellaterra: 1989.

- Molina González, F.; Rodríguez-Ariza, M.O.; Jiménez, S.; Botella López, M.C. La sepultura 121 del yacimiento argárico de el Castellón Alto (Galera, Granada). 2003.

- Alling, S. Foragers and Farmers. Prehistoric Archaeology Series 1988.

- Haenlein, G.F.W. About the evolution of goat and sheep milk production. Small Rumin. Res. 2007, 68, 3-6. [CrossRef]

- Gootwine, E.; Pollott, G.E. Factors affecting milk production in Improved Awassi dairy ewes. Animal Science 2000, 71, 607-615. [CrossRef]

- Medhi, D.; Das, P. Nutritional Influences on Wool Growth and Development. 2018.

- Kijas, J.W.; Lenstra, J.A.; Hayes, B.; Boitard, S.; Porto Neto, L.R.; San Cristobal, M.; Servin, B.; McCulloch, R.; Whan, V.; Gietzen, K.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of the world's sheep breeds reveals high levels of historic mixture and strong recent selection. PLoS Biol. 2012, 10, e1001258. [CrossRef]

- Ciani, E.; Lasagna, E.; D’Andrea, M.; Alloggio, I.; Marroni, F.; Ceccobelli, S.; Delgado, J.V.; Sarti, F.; Kijas, J.; Lenstra, J.; et al. Merino and Merino-derived sheep breeds: a genome-wide intercontinental study. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2015, 47, 64. [CrossRef]

- Ceccobelli, S.; Landi, V.; Senczuk, G.; Mastrangelo, S.; Sardina, M.T.; Ben-Jemaa, S.; Persichilli, C.; Karsli, T.; Bâlteanu, V.; Raschia, M.; et al. A comprehensive analysis of the genetic diversity and environmental adaptability in worldwide Merino and Merino-derived sheep breeds. Genet. Sel. Evol. 2023, 55, 24. [CrossRef]

- Scheu, A.; Hartz, S.; Schmölcke, U.; Tresset, A.; Burger, J.; Bollongino, R. Ancient DNA provides no evidence for independent domestication of cattle in Mesolithic Rosenhof, Northern Germany. Journal of Archaeological Science 2008, 35, 1257-1264. [CrossRef]

- Kahila Bar-Gal, G.; Ducos, P.; Kolska Horwitz, L. The application of ancient DNA analysis to identify neolithic caprinae: a case study from the site of Hatoula, Israel. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 2003, 13, 120-131. [CrossRef]

- Kaptan, D.; Atağ, G.; Vural, K.B.; Morell Miranda, P.; Akbaba, A.; Yüncü, E.; Buluktaev, A.; Abazari, M.F.; Yorulmaz, S.; Kazancı, D.D.; et al. The Population History of Domestic Sheep Revealed by Paleogenomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2024, 41. [CrossRef]

- Granero, A.; Anaya, G.; Demyda-Peyrás, S.; Alcalde, M.J.; Arrebola, F.; Molina, A. Genomic Population Structure of the Main Historical Genetic Lines of Spanish Merino Sheep. Animals 2022, 12, 1327.

- Arbuckle, B.; Atici, L. Initial diversity in sheep and goat management in Neolithic south-western Asia. Levant 2013, 45, 219-235. [CrossRef]

- Lianou, D.T.; Vasileiou, N.G.C.; Michael, C.K.; Valasi, I.; Mavrogianni, V.S.; Caroprese, M.; Fthenakis, G.C. Patterns of Reproductive Management in Sheep and Goat Farms in Greece. Animals 2022, 12, 3455.

- Anaya, G.; Granero, A.; Alcalde, M.J. Situación genética de las principales líneas puras del merino español. ITEA-Informacion Tecnica Economica Agraria 2024, 120 (2), 133-143. [CrossRef]

| Site | *MNI | **Dates | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valencina de la Concepción (Sevilla) | 114 [9], 4 [15], 8 [17] | III millennium BC | |

| Cabezo Juré (Alosno, Huelva) | 34 [2] | 2500 Cal BC. | |

| Papa Uvas (Aljaraque, Huelva) | 6 [27], 5 [28], 1 [24] | 3092-3052 Cal BC | |

| Gilena (Sevilla) | 3 [11] | End IV millennium/ Beginning III millennium BC | |

| Marinaleda (Sevilla) | 4 (this paper) | 2346-2138 Cal BC | |

| La Minilla (La Rambla, Córdoba) | 9 [5] | 2834-2470 Cal BC | |

| Torreparedones (Baena, Córdoba) | 2 [18] | 3020 Cal BC | |

| Iglesia Antigua de Alcolea (Córdoba) | 2 [6] | 3200 Cal BC | |

| Grañena Baja (Jaén) | 2 [3] | Beginning III millennium BC | |

| IA Corte Inglés (Jaén) | 1 [13] | III millennium BC | |

| Ciudad de la Justicia (Jaén) | 10 (Inédito) | III millennium BC | |

| Polideportivo de Martos (Martos, Jaén) | 4 [29,30] | Late IV millennium Cal BC | |

| Los Castillejos de Montefrío (Montefrío, Granada) | 24 [12] | 2325 Cal BC | |

| Cerro de la Virgen (Galera, Granada) | 8 [8] | Mid III millennium BC | |

| Les Moreres (Crevillent, Alicante) | 4 [23] | Mid/late III millennium BC | |

| Cueva de los Covachos (Almadén de la Plata, Sevilla) | 3 [31] | End IV millennium/ Beginning III millennium BC | |

| Zambujal (Torres Vedra) | 108 [7] | 2500 Cal BC | |

| Penedo do Lexim (Mafra) | 5 [20] | 2890-2620 Cal BC | |

| Ota (Alenquer, Portugal) | 6 [21] | First half of III millennium BC | |

| Perdigões (Reguengos de Monsaraz, Portugal). | 3 [16], 2 [22] | III millennium BC | |

| Monte da Tumba (Torrão, Portugal) | 33 [32] | First half of III millennium BC | |

| Mercador (Mourão, Portugal) | 14 [19] | Mid/late III millennium BC | |

| Alcalar (Portimão, Portugal). | 5 [33] | 2577-2335 Cal BC | |

| Sites | Code | BP | SD | Cal BC 95.4 % | m | Bone Sample | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| La Minilla | CNA-3151 | 3996 | 35 | 2619-2460 | 2525 | Cervus elaphus | [5] |

| La Minilla | CNA-3153 | 4034 | 36 | 2834-2470 | 2543 | Sus scrofa | [5] |

| La Minilla | CNA-3152 | 4040 | 35 | 2835-2472 | 2552 | Bos taurus | [5] |

| Grañena Baja | Beta-573496 | 4230 | 30 | 2910-2697 | 2858 | Human femur | [3] |

| Grañena Baja | Beta-573497 | 4330 | 30 | 3021-2891 | 2943 | Human tibia | [3] |

| Grañena Baja | CNA-3197 | 4347 | 35 | 3082-2895 | 2967 | Human bone | [3] |

| Grañena Baja | CNA-3194 | 4351 | 33 | 3083-2898 | 2968 | Human femur | [3] |

| Marinaleda | CIRAM-11738 | 3805 | 32 | 2346-2138 | 2244 | Ovis aries | This paper |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).