1. Introduction

The primary objective of this study is to investigate the role of financial literacy in enhancing economic resilience among Montenegrin households, focusing on behaviors such as savings, debt management, and financial planning. This research aims to provide actionable insights for policymakers and financial educators in Montenegro by identifying how improved financial literacy can foster economic stability at both the household and national levels.

In the global context, financial literacy has gained recognition as a critical factor for economic resilience, particularly in emerging markets facing heightened financial vulnerability. Montenegro’s economy, which heavily relies on tourism and service sectors, is highly susceptible to external economic fluctuations. By examining financial literacy within Montenegro’s unique socioeconomic landscape, this study contributes to a broader understanding of how financial education can serve as a stabilizing force in emerging economies, equipping citizens to navigate financial uncertainty and support sustainable growth.

Financial literacy, broadly defined as the understanding and effective use of financial concepts and products, plays a pivotal role in enhancing economic resilience and stability in individuals, households, and economies, especially in emerging markets [

1,

2]. Research consistently links higher financial literacy to positive financial behaviors such as increased savings, better debt management, and prudent investment decisions, all of which contribute to personal and economic stability [

3,

4]. For developing countries like Montenegro, where households face considerable economic uncertainties and where informal financial practices are prevalent, enhancing financial literacy could mitigate the impact of external economic shocks and provide a foundation for sustainable economic development [

5,

6,

7]. These effects are particularly relevant given Montenegro's reliance on vulnerable economic sectors, such as tourism, which make the economy susceptible to fluctuations, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic [

8].

Despite global evidence of financial literacy's benefits, limited research addresses its impact in Montenegro, where unique socioeconomic conditions may influence the relationship between financial knowledge and economic resilience [

9]. Studies in similar contexts, such as neighboring Balkan countries, show that financially literate individuals tend to make better financial decisions, particularly in times of economic uncertainty. These decisions, including higher savings rates and responsible borrowing, create a buffer against financial instability and help reduce the long-term impact of economic downturns [

10,

11,

12].

This study aims to explore the role of financial literacy in promoting economic stability and resilience among households in Montenegro, an under-researched area within the financial literacy literature. Using a data-driven approach, the research examines how financial literacy correlates with key indicators of economic stability—such as savings behavior, debt management, and financial planning practices—in Montenegro’s unique economic landscape. Ultimately, this research offers insights into the ways financial literacy can support sustainable development in emerging economies and provides actionable recommendations for policymakers aiming to strengthen Montenegro’s financial stability through education and resource access.

2. Literature Review

Literature review covers three important topics: relation between financial literacy and economic stability, importance of financial literacy in emerging economies and economic stability indicators.

Financial literacy is increasingly viewed as a key component of economic resilience, particularly in times of economic uncertainty. Research has shown that financially literate individuals are more likely to engage in behaviors that support economic stability, such as regular saving, prudent debt management, and effective financial planning. For instance, Lusardi and Mitchell (2014) emphasize that financial literacy enhances individuals' ability to make informed financial decisions, which is associated with increased savings rates, reduced debt, and more stable financial well-being over time [

1]. Financial literacy also contributes to better financial risk management. In a study by Klapper, Lusardi, and van Oudheusden (2015), individuals with higher financial literacy were more likely to engage in behaviors that minimize financial risk, such as diversifying investments and avoiding high-cost borrowing practices, helping them to better withstand financial shocks [

3]. Additionally, evidence suggests that financially literate individuals are more capable of aligning their personal financial goals with sustainable economic practices, such as environmentally conscious spending and investing [

13].

Empirical research highlights a strong correlation between financial literacy and economic resilience. Financially literate individuals tend to experience fewer economic hardships due to their proactive financial behaviors, which contribute to individual and collective economic stability (Atkinson & Messy, 2012) [

2]. The ability to make informed financial decisions enhances households' preparedness for economic downturns, underscoring the importance of financial education in building economic resilience at a societal level (OECD, 2020) [

11].

In emerging and transition economies, financial literacy plays a particularly significant role in enhancing economic resilience and stability. Studies in these regions have shown that limited financial knowledge often corresponds to high levels of indebtedness, low savings rates, and limited access to financial products, all of which hinder economic growth and stability. In the context of the Western Balkans, a region with varying degrees of economic development, financial literacy is relatively low compared to EU standards, which poses challenges for economic resilience. According to a study by the World Bank (2021), the Western Balkans, including Montenegro, show a consistent need for improved financial literacy to support economic stability amid regional vulnerabilities [

14]. For instance, in Montenegro, financial literacy is crucial for reducing reliance on informal financial services and promoting the use of formal financial institutions, which offer more reliable mechanisms for savings and investment (Bulatovic, 2020) [

5].

Emerging economies are generally more susceptible to financial shocks, which can exacerbate socioeconomic inequalities. Studies across various developing countries have illustrated that when individuals possess financial knowledge, they tend to save more consistently, use credit wisely, and participate more actively in the formal economy, reducing their financial vulnerability (Cole, Sampson, & Zia, 2011) [

10]. In the Western Balkans, financial literacy has been linked to positive economic behaviors, such as higher rates of savings and responsible credit usage, which are critical to individual and regional economic stability in the face of global economic challenges [

15].

Economic stability is often assessed using indicators that reflect financial health and resilience at the individual and household levels. Common indicators include income stability, savings rates, access to financial services, and the degree of reliance on debt. Income stability reflects regularity in income flows and is a fundamental aspect of financial security. Households with stable incomes are better equipped to manage financial shocks and maintain consistent consumption patterns. Savings rate, another critical indicator, reflects a household’s ability to build financial reserves and prepare for future expenses. Regular saving behavior is widely regarded as a key outcome of financial literacy, as it reflects individuals' ability to delay consumption and plan for the future (Beck & de la Torre, 2007) [

16].

Access to financial services is also essential, as it enables individuals to participate fully in the formal economy, which is often associated with better financial outcomes and reduced poverty rates. Studies have shown that limited access to banking services in emerging markets can constrain economic resilience by restricting individuals' ability to save securely, borrow prudently, and invest in growth opportunities (OECD, 2016) [

4]. Finally, reduced reliance on debt, especially high-interest or informal debt, is an indicator of financial health, as lower debt burdens are associated with more stable financial outcomes. Financial literacy has been linked to lower levels of unmanageable debt, as financially knowledgeable individuals tend to be more cautious with borrowing and better at managing credit, reducing their financial vulnerability over time [

2].

In developing and transition economies, where economic systems are often undergoing significant changes, financial literacy can play a transformative role in stabilizing household finances and contributing to overall economic growth. Financial education initiatives in countries like India, South Africa, and China have demonstrated measurable improvements in financial decision-making among low-income individuals, leading to enhanced savings rates, lower reliance on debt, and a higher likelihood of engaging with formal financial institutions (Cole, Sampson, & Zia, 2011; Karlan, Ratan, & Zinman, 2014) [

17,

18]. The positive impact of financial literacy on economic resilience is particularly evident in rural or underbanked areas, where financial literacy enables individuals to diversify income sources and adopt prudent financial practices that reduce vulnerability to income variability (Banerjee, Karlan, & Zinman, 2015) [

19].

While the Western Balkans region has historically faced financial literacy challenges, there is a growing awareness among policymakers of the role financial education can play in promoting financial inclusion and stability (OECD, 2020) [

20]. Studies in neighboring Western Balkan countries reveal similar trends. In Serbia, for example, low levels of financial literacy have been associated with high levels of debt and limited savings (Spiranec, Zorica and Simoncici, 2012), which has led policymakers to promote financial education as a means of supporting sustainable economic growth [

21]. Financial literacy initiatives in these regions focus not only on knowledge dissemination but also on behavior change, encouraging responsible financial habits that support long-term economic security.

Montenegro, like many emerging economies, faces unique economic challenges that amplify the importance of financial literacy for economic stability. Its small economy is highly susceptible to external shocks, such as global market fluctuations and crises affecting its tourism and service sectors (World Bank, 2021) [

22]. Financial literacy could thus play a vital role in enhancing resilience among Montenegrin households by promoting responsible financial behaviors and reducing over-reliance on high-interest credit sources. Research shows that in countries with similar economic profiles, financially literate populations tend to be more resilient to such external shocks, as they are better equipped to manage their finances during crises (Kempson, Finney, & Poppe, 2017) [

23].

Despite its potential benefits, financial literacy remains limited among certain Montenegrin demographic groups, particularly those with lower education levels and limited access to financial services (EBRD, 2018) [

24]. Surveys reveal that many individuals struggle with fundamental financial concepts, such as budgeting, saving, and managing debt, which hinders their ability to make effective financial decisions. Consequently, these populations are more vulnerable to economic instability, as they lack the knowledge necessary to buffer against financial shocks (Katnic, Katnic, Jakisic-Stojanovic, 2023) [

25]. Financial literacy in Montenegro, therefore, not only represents a means of individual empowerment but also serves as a critical component of the country’s broader economic stability framework.

Access to financial services is another essential element linked to financial literacy and economic resilience. In many emerging economies, financial literacy improves individuals' ability to understand and utilize financial services, leading to increased use of savings accounts, insurance products, and pension funds (Beck & de la Torre, 2007; Demirgüç-Kunt, Klapper, & Singer, 2017) [

26,

27]. Financially literate individuals are more likely to use these services effectively, which in turn supports their ability to manage risks, accumulate savings, and achieve long-term financial goals (Klapper et al., 2015) [

28]. Enhanced financial literacy thus contributes to sustainable economic development by increasing individuals’ access to resources that can stabilize their finances over time, reducing the need for unsustainable debt and fostering more stable economic growth.

In Montenegro, increasing financial literacy could significantly enhance access to and utilization of financial services, particularly among underbanked and rural populations. According to surveys, many Montenegrins still rely on informal borrowing methods due to limited awareness or understanding of formal financial products (OECD, 2020) [

13]. This reliance on informal lending can lead to debt cycles that diminish economic resilience. By improving financial literacy, individuals in Montenegro may be more likely to engage with formal financial institutions, access affordable credit, and build emergency savings, which can increase their economic resilience and contribute to sustainable development

The literature on financial literacy provides robust evidence of its role in promoting economic stability, resilience, and sustainable development, particularly in emerging and transition economies [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Financial literacy enables individuals to manage finances effectively, reduce vulnerability to economic shocks, and make informed decisions about financial products [

33,

34,

35,

36]. In the context of Montenegro, where economic challenges persist, improving financial literacy could empower individuals to contribute to the country's economic resilience and sustainable growth. By addressing these gaps, this study seeks to explore the specific impacts of financial literacy on economic stability in Montenegro, contributing to the broader body of knowledge on sustainable development in emerging economies.

3. Materials and Methods

This literature review frames financial literacy as important to economic resilience, particularly in Montenegro, where household stability could greatly benefit from better financial knowledge and behaviors. Additional data or recent studies specific to Montenegro could further enhance this section, adding depth to local financial literacy challenges and trends.

This study investigates the relationship between financial literacy and economic resilience in Montenegro, focusing on how financial literacy influences financial behaviors that contribute to household-level economic stability. A cross-sectional survey was conducted using a structured questionnaire designed to assess participants' financial literacy, financial behaviors, and resilience to economic shocks. The sample comprised 1,000 adult Montenegrin residents, recruited using a stratified random sampling approach to ensure that the sample accurately reflects the demographic and socioeconomic diversity of the Montenegrin population. The survey was structured to capture both financial literacy levels and financial behaviors among Montenegrin adults. It included several sections designed to assess participants' understanding of fundamental financial concepts and to gauge their financial habits and decision-making behaviors. The survey included both multiple-choice questions and Likert-scale items, allowing respondents to express levels of agreement or familiarity with certain financial terms and behaviors.

In the part about financial literacy assessment main goal was to measure knowledge of core financial concepts, such as interest rates, inflation, budgeting, debt management, and investment principles. Questions were drawn from established financial literacy assessments, including the OECD/INFE Toolkit for Measuring Financial Literacy, ensuring alignment with global standards. For instance, respondents were asked simple questions on interest calculation, inflation effects, and loan terms to gauge comprehension of basic financial terms and calculations. In order to assess financial behaviors, the survey included questions about saving practices, bill payment timeliness, budgeting habits, and attitudes toward risk in investment. These items were designed to capture both short-term and long-term financial practices. Respondents answered using a Likert scale, which allowed for an understanding of their behavioral tendencies and self-reported consistency in financial management. The survey also collected demographic data, such as age, gender, education level, employment status, and geographic location. This enabled stratification of results to analyze how financial literacy and behaviors may vary across different demographic groups within Montenegro.

This structured approach aimed to provide a comprehensive picture of financial literacy and behavior, facilitating insights into economic resilience and decision-making patterns. By using standardized questions and scales, the survey design allows for future replication and comparison with similar studies in other contexts or over time.

Data collection was conducted during spring and summer 2024 using in-person survey method and survey was conducted by scientific research organization Center for Finance from Montenegro. Respondents were required to provide informed consent before participating. The survey comprised sections measuring demographic variables (age, gender, education level, employment status), financial literacy (knowledge of interest rates, inflation, budgeting, and saving practices), financial behaviors (savings rates, debt management, investment activities), and resilience to financial stressors (ability to handle economic fluctuations and emergencies).

The financial literacy component of the survey was adapted from established scales, such as the OECD/INFE Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion Survey [

2,

20]. This instrument includes questions to assess core financial concepts and practical skills, enabling an evaluation of respondents’ understanding of interest rates, inflation, and financial planning.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 25) to explore the relationship between financial literacy and economic resilience in Montenegro. Descriptive statistics were computed to provide an overview of the demographic characteristics of the sample and general financial literacy levels.

Correlation analysis was also conducted. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the strength and direction of relationships between financial literacy and specific financial behaviors, including savings rate, debt management, and resilience to economic shocks. This analysis aimed to explore the extent to which financial literacy is associated with behaviors that contribute to economic stability.

All data associated with this publication will be made available in a publicly accessible repository at the Center for Finance upon acceptance of the manuscript. Data accession numbers will be provided before publication to allow for verification and replication by future researchers.

All procedures followed ethical guidelines for research involving human participants. Participants provided informed consent and were assured of their right to withdraw from the study at any time. Personal data were anonymized to protect confidentiality, and only aggregated data were analyzed and reported. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Therefore, based on the relevant literature and data obtained from the empirical research, general hypothesis of the paper is defined as: Financial literacy, shaped by demographic factors such as age, education level, marital status, and income, significantly influences household budgeting behavior, saving methods, and financial stability. Higher levels of financial literacy are associated with better financial management practices, including the likelihood of maintaining a budget and utilizing formal saving methods.

Several limitations may affect the interpretation and generalizability of the findings, such as sample bias, question interpretation and cross-sectional design. While the sample was designed to be representative, certain demographic groups may have been underrepresented, particularly individuals in rural areas or lower-income brackets who may have limited access to digital survey tools. This could skew results, especially in areas where financial literacy may be lower or financial behaviors differ from urban populations. Also, the survey relied on self-reported responses, which can introduce biases such as social desirability bias, where participants may answer questions in a way that they believe is more socially acceptable rather than truthful. This limitation is particularly relevant in questions related to responsible financial behavior, such as saving and budgeting. Given that financial literacy involves complex terminology, there is a possibility that some respondents may have misunderstood certain questions, particularly those involving technical financial terms. Although questions were simplified, variations in interpretation could still impact accuracy, especially among respondents with lower educational backgrounds. The survey’s cross-sectional nature captures data at a single point in time, which limits insights into how financial literacy and behaviors may evolve. OECD survey conducted in 2020 was used for some comparison. Future studies could benefit from a longitudinal approach to track changes over time, particularly as financial literacy initiatives and economic conditions evolve in Montenegro.

4. Results

In the contemporary economic landscape, marked by rapid market fluctuations, increasingly complex financial instruments, heightened consumer expectations, and escalating levels of private and public debt, personal financial management has gained critical importance [

37,

38,

39,

40]. Individuals equipped with foundational knowledge in financial concepts—such as savings, investments, credit assessment, and debt management—demonstrate a greater capacity to make informed financial choices that sustainably improve their living standards over time. Consequently, a society composed of financially literate individuals is inherently more resilient and better positioned for sustainable economic growth [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

Reflecting the necessity of financial education, the Center for Finance, a certified research institution, conducted a comprehensive Financial Literacy Survey of Adults in Montenegro (hereafter referred to as "the Survey"). The methodology of this survey is aligned with globally recognized standards set by the International Network on Financial Education (INFE) of the OECD, ensuring rigor and comparability across international benchmarks. The Survey's data and subsequent analysis provide policymakers and the general public with critical insights to:

Establish a foundational measure of national financial literacy levels;

Offer essential data to inform the development of national strategies and targeted financial literacy programs;

Determine financial literacy levels across key socio-demographic groups, aiding policymakers in identifying underserved populations and specific educational gaps;

Enable longitudinal research to identify trends and changes in financial literacy over time; and

Generate data that is compatible with global standards for cross-country comparisons.

To measure financial literacy, the Survey applies the OECD's definition: "a combination of awareness, knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors necessary to make sound financial decisions and ultimately achieve individual financial well-being."

Conducted on a representative, two-stage stratified sample of 1,000 Montenegrin adults aged 18–79, the study design ensured comprehensive geographic coverage (encompassing all Montenegrin municipalities) and balanced representation across primary demographic variables, including gender and age. This stratification allows for a nuanced analysis of financial literacy across the population, providing a robust dataset for policy development and educational interventions in Montenegro.

4.1. Assessing Financial Literacy, Attitudes and Inclusion in Montenegro: Insights into Economic Behavior and Stability Indicators

Results obtained about financial knowledge, attitudes, resilience, and access to financial services in Montenegro will be shortly presented bellow. Financial knowledge is a crucial component of financial literacy, enabling individuals to understand financial products, compare options, and make informed decisions. Studies in this area show that financial knowledge is positively associated with proactive behaviors, such as saving and retirement planning, and inversely related to debt levels [

46,

47,

48]. Greater financial knowledge contributes to overall financial stability, enhancing quality of life, particularly in later years. Individuals with higher financial knowledge tend to exhibit greater resilience to financial shocks and make better decisions related to saving, debt management, and investments.

4.1.1. Understanding Inflation: Accuracy of Responses on Inflation-Related Questions

Learning from personal experience appears to be particularly impactful, especially regarding inflation awareness in Montenegro. With historical periods of hyperinflation and recent high inflation rates, Montenegrins seem well-acquainted with the concept. Approximately 85% of respondents correctly acknowledged that with 5% inflation, they could afford less over time, and 82.4% correctly identified inflation itself. Around 7% of respondents were unsure on both questions, suggesting a broad understanding but also highlighting a minority who remain uncertain about inflation’s effects.

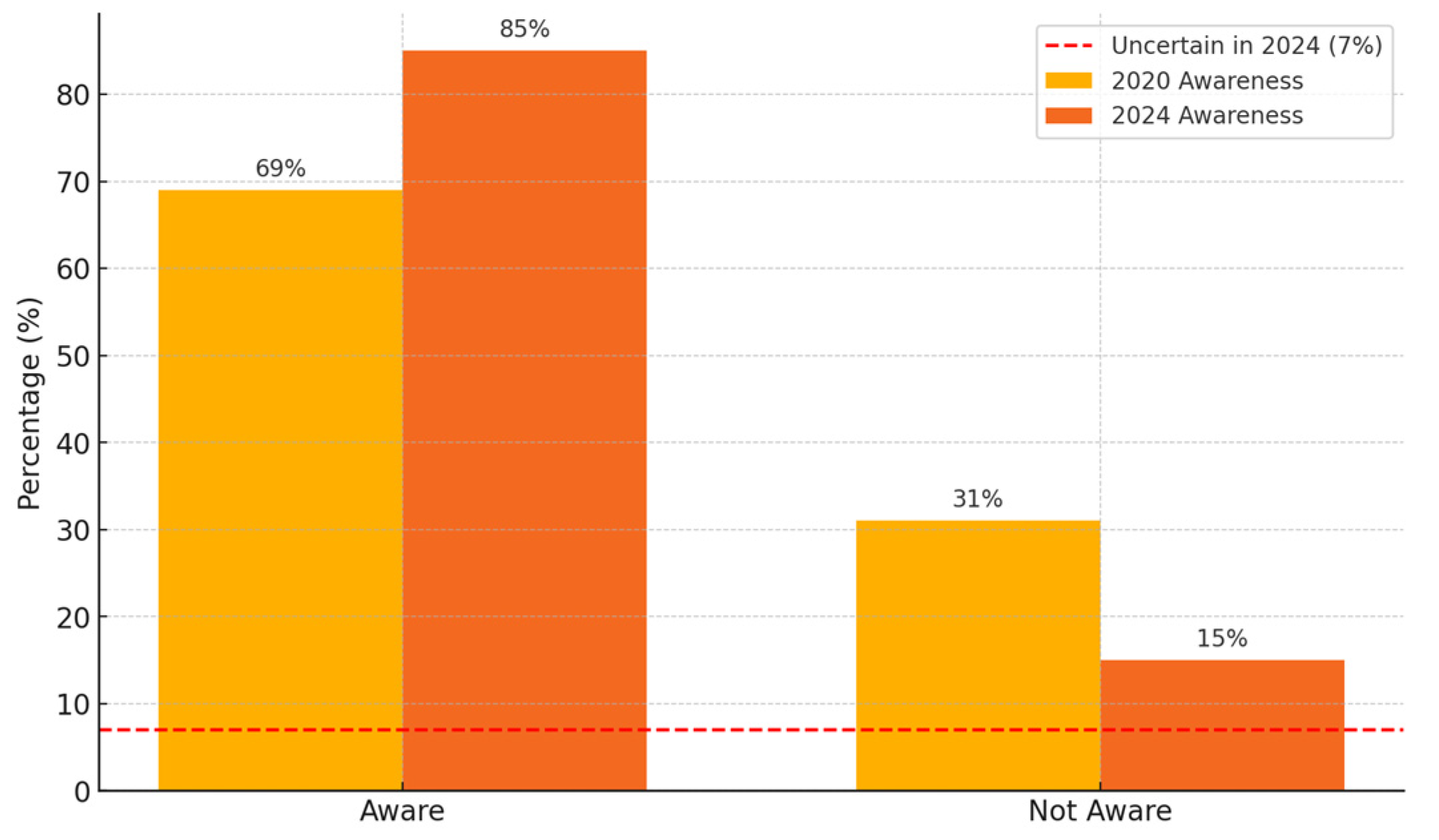

In recent years, inflation has become a prominent topic in Montenegro, affecting nearly every household due to significant price increases. Research data from 2024 show that a greater percentage of Montenegrins now understand inflation compared to four years prior. In a 2020 study, only 69% of respondents recognized that inflation means they could buy less with the same amount of money over time. As could be seen on

Figure 1, by 2024, that percentage had risen by 16 points to 85%, reflecting heightened public awareness due to lived experiences with inflation.

4.1.2. Financial Concepts and Calculation Comprehension

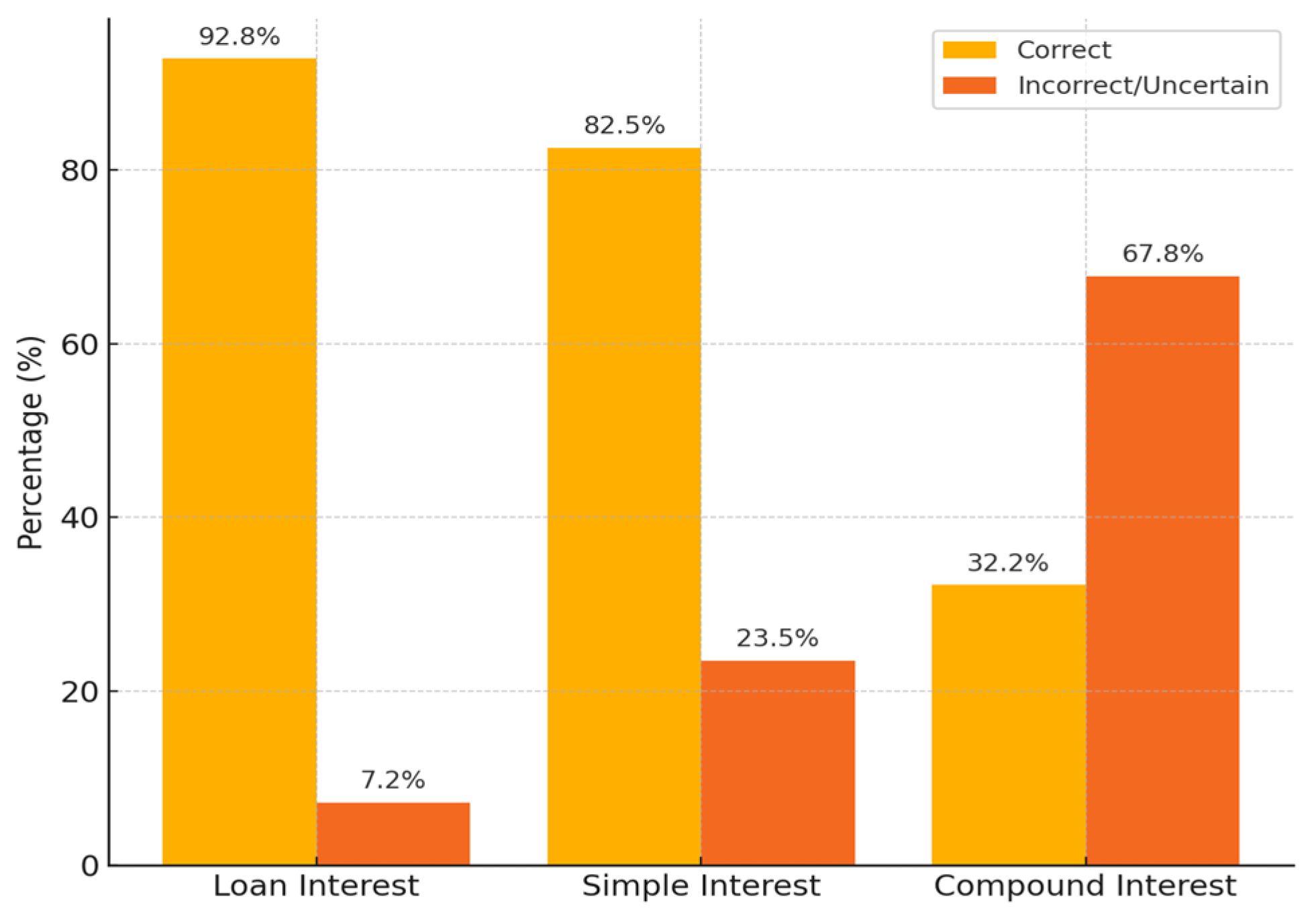

In Montenegro, the vast majority of individuals exhibit a basic understanding of interest concepts, with 92.76% of respondents recognizing the meaning of interest on loans or credit. However, comprehension declines as questions become more mathematically complex. For instance, 17.47% of participants incorrectly answered a question about simple interest calculation, and 6.08% reported uncertainty with the concept. The understanding of compound interest proved even lower; only one-third of respondents correctly answered a question on calculating compound interest over five years, while 67.76% either answered incorrectly or selected “don’t know.” This highlights the gap in financial literacy concerning more advanced interest concepts and the results are presented in

Figure 2.

A comparative analysis of data regarding respondents' correct answers to questions on interest calculation over a five-year period indicates a notable improvement in financial literacy in Montenegro. Specifically, the percentage of individuals correctly calculating interest increased from 24% in 2020, according to OECD research, to 32.24% in 2024. This four-year progress suggests a significant enhancement in understanding interest calculations among the population. Contributing factors may include the heightened relevance of the topic due to substantial increases in interest rates over recent years, alongside rising levels of household indebtedness to commercial banks. This trend underscores the potential impact of economic conditions on financial literacy outcomes.

4.1.3. Financial Knowledge and Beliefs Across Montenegro

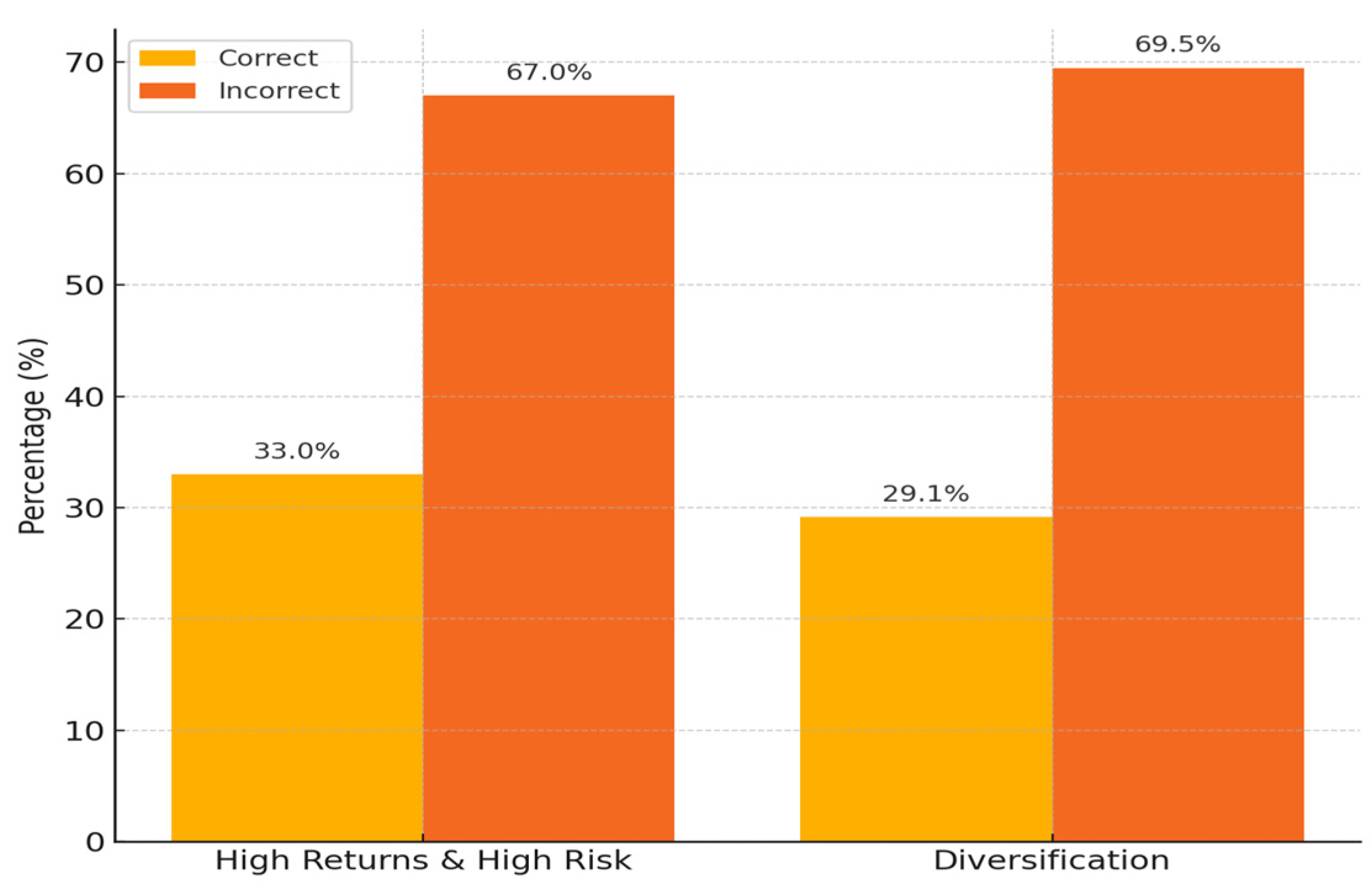

The research indicates that a significant proportion of adults in Montenegro lack a comprehensive understanding of key financial concepts, specifically risk, return, and investment. As presented in

Figure 3. approximately one-third of respondents incorrectly identified the relationship between high expected returns and high risk. Furthermore, over two-thirds demonstrated a lack of understanding regarding diversification, with 69.5% incorrectly responding that it is not possible to reduce risk in the stock market by purchasing multiple stocks. Only 29.15% correctly acknowledged this concept.

These findings align closely with results from the OECD study conducted in 2020, which reported that only 35% of respondents provided correct answers regarding these financial concepts. This consistency suggests a persistent gap in financial literacy among the adult population in Montenegro, highlighting the need for targeted financial education initiatives to enhance understanding of these fundamental investment principles.

4.1.4. Household Budgeting and Financial Decision-Making Roles

Financial behaviors, habits, and practices are critical determinants of individual financial stability and resilience to external shocks. Financial behavior encompasses how individuals manage their finances, including aspects of spending, saving, borrowing, and investing. The comprehension and implementation of responsible financial practices are essential not only for personal success but also for contributing to broader economic well-being. Rapid advancements in finance, including digitalization and tokenization, necessitate ongoing education to keep pace with changing financial landscapes [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55]. It is, therefore, imperative to assess and identify the financial behaviors of individuals in Montenegro to enhance understanding of their financial literacy levels.

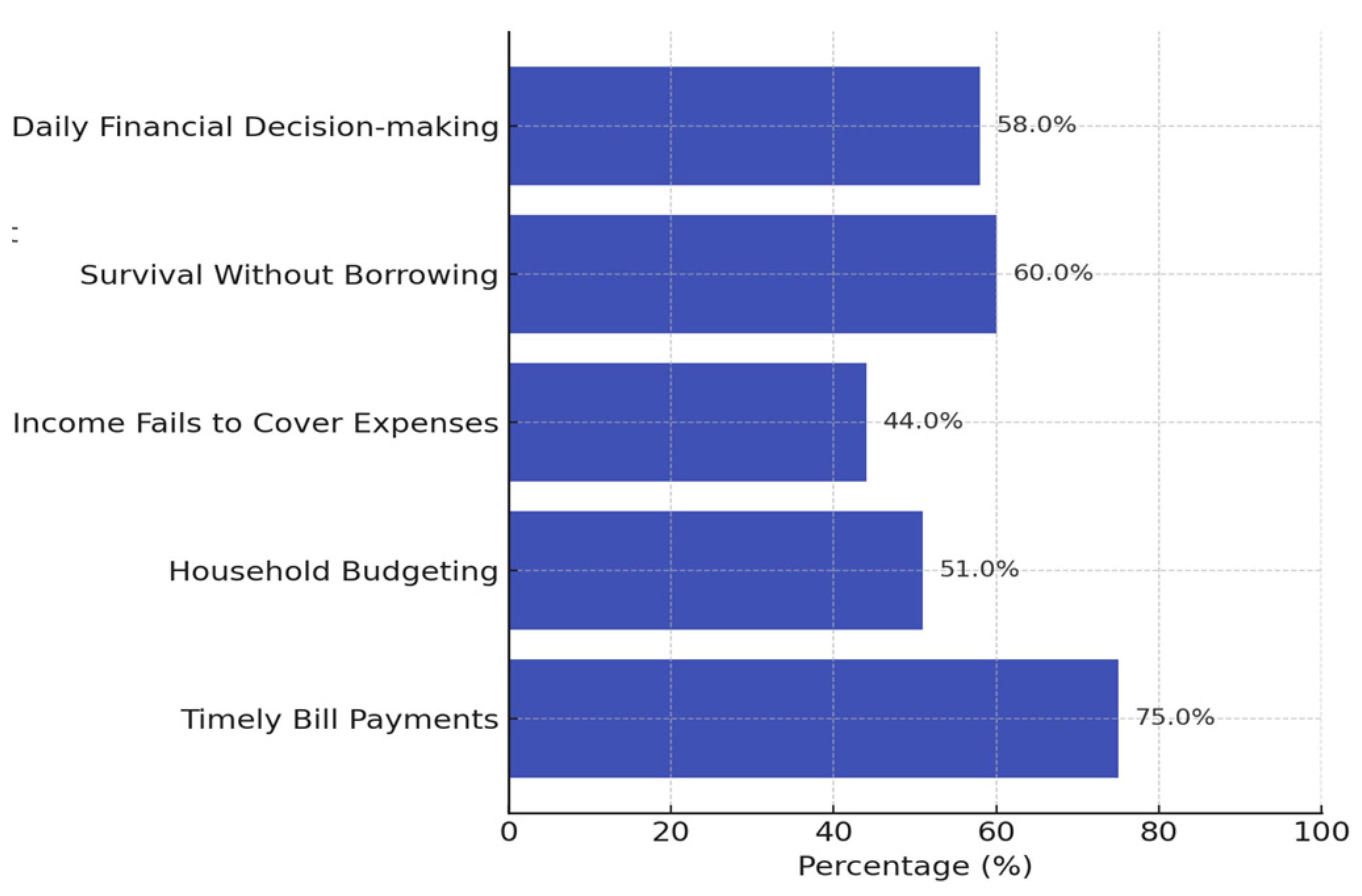

Survey results examines various financial habits of citizens, such as timely bill payments, household budgeting, the incidence of income failing to cover expenses, survival strategies during financial strain, and the ability to endure without borrowing money and results are presented in

Figure 4. The research reveals significant variations in financial behavior, influenced not only by respondents' age groups but also by their geographical origins. Additionally, responses differ notably from those recorded in the 2020 study, particularly regarding budgeting practices and daily financial decision-making. Given the multitude of daily decisions individuals face that can affect their financial resilience, especially during crises, this study explores these decision-making processes.

In a world vulnerable to various internal and external shocks, maintaining a clear overview of household financial status is crucial. Consequently, budgeting is an essential aspect of financial literacy, as highlighted in the G20/OECD INFE framework for adult financial literacy competencies developed in 2016. More than half of the respondents (50.97%) indicated that their households do have a budget, while 41.60% reported that they do not.

4.1.5. Financial Attitudes and Behavior Patterns

Data obtained from the current research diverge from the findings of the 2020 study, indicating a decline in the percentage of respondents maintaining a household budget. Specifically, in 2020, 61% of respondents reported having a budget, reflecting a decrease of 10 percentage points in the present study.

Furthermore, the data regarding decision-making related to household finances provide insights into both the current financial practices and the cultural patterns prevalent in Montenegro. Among respondents in multi-member households, particularly those who are married or in cohabiting relationships, 286 individuals (30%) indicated that they are responsible for financial decisions within the household. Gender analysis reveals that men more frequently assume responsibility for these financial decisions, comprising 55.6% of respondents.

This data not only underscores changes in budgeting habits but also highlights gender dynamics in financial decision-making, which may be influenced by cultural norms and values within Montenegrin society.

4.1.6. Savings, Income Adequacy and Financial Resilience

The literature on financial literacy emphasizes the significance of active saving, particularly during challenging economic times. Saving not only facilitates the achievement of long-term financial goals but also establishes a foundation for investment opportunities. When savings are directed toward investments, they can enhance financial growth through passive income and provide a buffer against inflation.

Traditionally, individuals have relied on keeping cash at home as their primary savings method. However, with the increasing stability of the banking sector and growing public confidence, a rising number of citizens are opting to deposit their savings into bank accounts. Financially literate individuals tend to diversify their investments across various financial instruments, including bonds, stocks, and funds, as well as riskier ventures. Notably, higher financial literacy does not necessarily correlate with a greater willingness to assume risk; often, those who invest in high-risk projects are less financially literate.

Current findings indicate that over one-third of respondents (39%) save money at home, while 25% save through bank accounts. This suggests that nearly two-thirds of the adult population in Montenegro either keeps excess funds at home or deposits them in banks. Given that much of the bank savings are held in non-interest-bearing or low-interest accounts, it can be inferred that a substantial portion of Montenegrin adults with surplus funds are not utilizing these resources for investment, thereby missing out on potential earnings. Such financial behaviors are particularly noteworthy in the context of high inflation rates and the depreciation of money value.

These insights underline the necessity for enhanced financial education and awareness, especially in light of the current economic climate where traditional saving methods may not suffice to preserve wealth.

4.1.7. Financial Product Awareness and Utilization

Financial literacy and financial inclusion are globally recognized as essential components for empowering individuals and ensuring overall financial stability. Therefore, it is crucial for policymakers to have access to data regarding both individual financial inclusion and financial literacy levels [

56,

57,

58]. This chapter provides insights into the understanding and utilization of financial products from a consumer perspective.

Financial inclusion is a bidirectional process requiring appropriate financial products on the supply side and consumer awareness on the demand side. Data indicates that over two-thirds of respondents (67%) are familiar with financial products, with 7% having made selections from available offerings in the recent past. Furthermore, a notable 35% of respondents reported seeking financial assistance from family during periods of financial distress. This statistic is consistent with findings from a 2020 study, where 36% of participants indicated they turned to family and friends for financial loans.

Banking products dominate the financial landscape, with increasing digitalization recognized as a necessity. The study found that 95% of respondents are aware of loans, while credit cards are recognized by 87% of participants. Additionally, 61% are familiar with mobile banking, and 80% have heard of stocks, a result likely influenced by ownership transformation processes and a growing interest among younger individuals in investing. Awareness of bonds was noted at 56%, though only 1% of respondents own them.

To evaluate access to finance and general financial literacy, indicators were used to assess the possession of savings, investment, and pension products, payment financial products (excluding credit cards), and various forms of insurance. The results indicate that 54% of respondents have a checking account, 47% own a credit card, and 34% use mobile banking. Notably, consumer debt has increased by 8.7% during 2023, reaching €1.69 billion, marking the highest historical level. This trend aligns with findings from the Financial Stability Report, which notes that an increasing number of citizens possess some form of credit (45%), reflecting a growing understanding of credit and interest rate concepts.

4.2. Exploring the Correlation Between Financial Literacy and Economic Stability: A Pearson Correlation Analysis of Financial Behaviors

The Pearson correlation analysis of financial behaviors reveals interesting insights into the relationship between financial literacy and economic stability. One of the strongest positive correlations is observed between individuals who "pay bills on time" and those who "carefully monitor personal finances" (correlation coefficient of 0.508). This suggests that diligent financial monitoring, a key component of financial literacy, is closely associated with responsible bill-paying behaviors, an indicator of economic stability. Timely bill payments are critical for maintaining a positive credit history and avoiding debt accumulation, both of which contribute to long-term financial security as shown in

Table 1. Most of these correlations presented in

Table 1. are highly significant (Sig. < 0.01), indicating that the relationships are unlikely to be due to chance.

Another significant finding is the negative correlation between the tendency to "live for today" and the habit of carefully checking affordability before making purchases (correlation of -0.490). This implies that individuals with a present-focused mindset are less likely to exercise cautious spending habits, potentially leading to impulsive financial decisions that could undermine economic resilience. Additionally, the tendency to "live for today" negatively correlates with paying bills on time (-0.438), which could reflect a short-term outlook that overlooks essential financial obligations, heightening the risk of financial instability.

Interestingly, there is a moderate positive correlation between those willing to take investment risks and those who set long-term financial goals (0.271). This association suggests that risk tolerance, when coupled with a long-term perspective, may be part of a more strategic approach to wealth-building and stability. However, high risk tolerance without proper financial planning might still lead to potential financial setbacks, especially in volatile economic conditions.

Moreover, individuals who prefer to spend rather than save money show a significant positive correlation with the belief that "money is there to be spent" (0.380). This reflects an attitude toward immediate consumption, which can reduce the capacity for long-term savings and emergency funds, essential elements of financial resilience. Conversely, those who carefully monitor personal finances and prioritize long-term goals tend to have lower correlations with these present-focused, spend-oriented behaviors, reinforcing the idea that financial literacy promotes prudent financial management.

In summary, the analysis highlights how financial literacy, as reflected in careful spending, financial monitoring, and goal-setting behaviors, is positively correlated with financial practices that enhance economic stability. Conversely, a preference for short-term consumption and a "live-for-today" mentality correlates negatively with indicators of financial stability. These findings suggest that fostering financial literacy could help individuals adopt habits that improve their economic resilience and security over time.

Our analysis reveals a clear age-related trend in household budgeting habits. Younger respondents, particularly those aged 18-19, show the lowest likelihood of maintaining a budget, with only 37.5% reporting having one. Budgeting practices increase significantly within the 20-39 age range, peaking among individuals aged 30-39, where 65.9% have established a budget. However, budgeting declines among older age groups, with only 40% to 48% of respondents aged 50 and above maintaining a budget. This trend suggests that middle-aged individuals may recognize the importance of budgeting as they assume more financial responsibilities, while younger and older groups may benefit from tailored financial education to emphasize the importance of long-term planning.

Education level strongly influences saving behaviors, with higher education correlating with more diversified saving methods. Among university graduates, a higher percentage utilize formal saving options, such as bank accounts, and some even invest in stocks or real estate (about 2-3% each), indicating a higher financial literacy level. In contrast, secondary school graduates predominantly save in cash, and 18.5% report not saving at all, revealing potential barriers to financial inclusion. Among those with only primary or elementary education, saving behaviors are even more limited; these respondents are more likely to save in cash or not save at all, underscoring a lack of engagement with formal financial institutions. This analysis underscores the importance of education in fostering financial literacy and highlights a need for targeted programs that promote formal savings methods and educate lower-educated groups on the benefits of diversified saving.

Marital status appears to play a role in respondents' perceptions of income sufficiency. Single and divorced individuals report the highest levels of income insufficiency, with around 50-60% indicating that their income does not meet their expenses. In contrast, married individuals exhibit better financial stability, with 57% able to meet their expenses, potentially due to shared household income. For individuals in "common-law" partnerships, 53% report income sufficiency, while widowed individuals present a more mixed financial picture, with both income sufficiency and shortfalls reported. These findings highlight the potential impact of marital status on economic stability, suggesting that single and divorced individuals may require more support in building financial resilience.

An analysis of budgeting habits across education levels reveals a positive correlation between higher education and budgeting practices. University graduates show the highest propensity for budgeting, with 60.4% maintaining a budget, while only 35.5% do not budget, indicating a strong inclination toward financial planning. Secondary school graduates, however, are split, with 44.2% budgeting and 45.7% not having a budget. Notably, 6.4% of secondary school graduates reported uncertainty about budgeting, possibly reflecting limited financial literacy. Among those with only primary education, 42.9% have a budget, while 44.3% do not, and a notable 10% are uncertain about budgeting. This uncertainty is even more pronounced among those with informal education, where 55% do not budget, and 3.3% are unsure. Interestingly, the small group without formal education reports the highest budgeting rate at 83.3%, though this group’s small size limits the representativeness of the finding.

These findings suggest that higher education correlates with a greater likelihood of budgeting, while lower education levels, particularly primary and informal education, are associated with inconsistent budgeting practices and higher uncertainty regarding financial planning [

59]. This reinforces the importance of integrating financial literacy education into early and secondary school curricula to foster budgeting habits and financial planning skills from a young age.

4.3. Understanding Financial Literacy in Montenegro Using Decision Tree Analysis

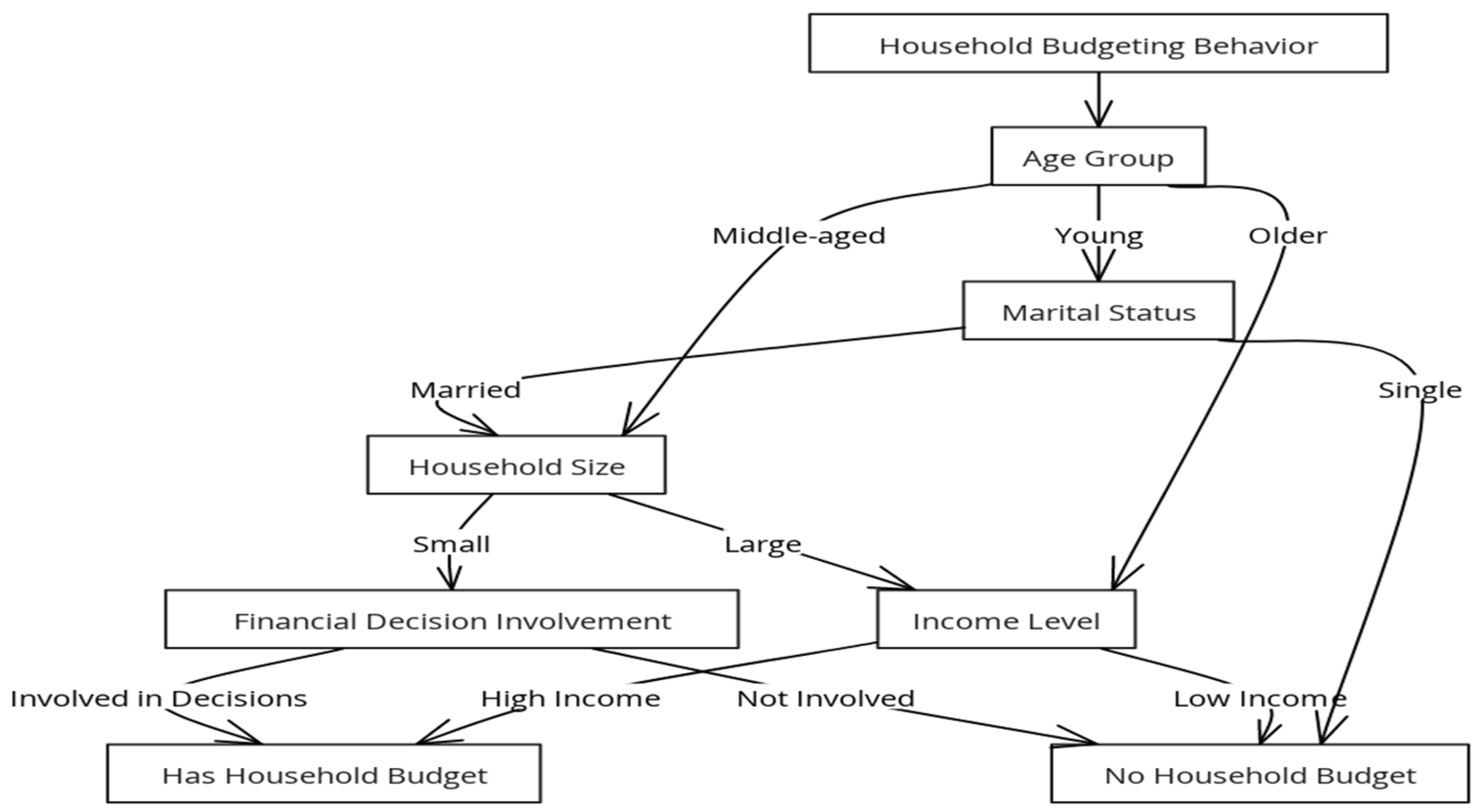

The decision-making process behind household budgeting behaviors based on demographic and financial factors. Here’s a step-by-step interpretation in a more scientific framework. The main objective or outcome of interest in the model is whether or not a household maintains a budget. This variable is influenced by several layers of demographic and financial characteristics, moving from general demographics to specific financial involvement.

The first level of segmentation is by age group, categorizing individuals as

Young,

Middle-aged, or

Older. This segmentation acknowledges that age often correlates with financial practices and stability, where, for instance, middle-aged individuals might be more likely to budget than younger or older age groups. For younger individuals, the model introduces marital status as the next determinant, dividing them into

Single and

Married categories. Marital status is a critical demographic factor, as marriage can lead to shared financial responsibilities, possibly increasing the propensity to budget. For married individuals,

Household Size becomes the next factor, dividing households into

Small and

Large. Household size impacts budgeting behaviors because larger households might require more structured financial management due to increased expenses and complexity. For small households, the model examines

Financial Decision Involvement — whether individuals in the household are actively involved in financial decisions. This is based on the assumption that involvement in financial decision-making enhances awareness and responsibility for budgeting practices. Those who are involved are more likely to have a household budget. For larger households or those with less decision-making involvement,

Income Level is considered next, categorized as

High Income and

Low Income. Income level is a significant predictor of budgeting behavior; higher income levels generally facilitate financial planning, while low-income households may prioritize immediate needs, reducing the likelihood of budgeting. The pathways lead to two potential outcomes — either the household maintains a budget or does not. The likelihood of each outcome depends on the pathway followed through demographic and financial characteristics as presented on

Figure 5.

In sum, this decision tree model identifies age, marital status, household size, financial decision involvement, and income level as critical factors that collectively influence the likelihood of household budgeting. This hierarchical model aligns with prior research emphasizing that socioeconomic and demographic factors play substantial roles in financial behavior [

60,

61,

62,

63,

64].

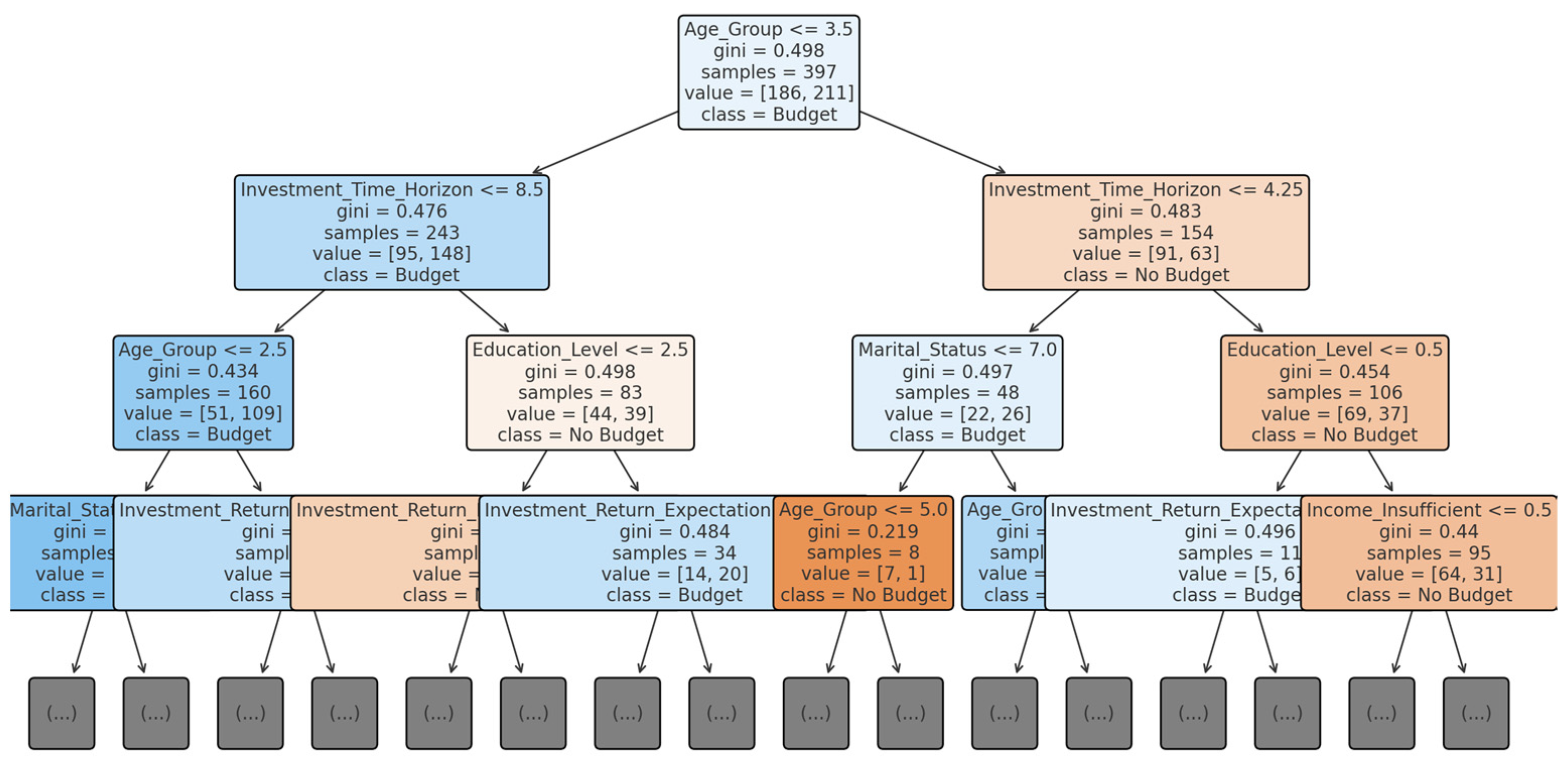

To examine the factors influencing household budgeting behavior, we developed a decision tree model that leverages demographic and financial characteristics as predictors. The primary objective of the model was to classify whether a household maintains a budget (1) or does not (0). Predictor variables included age group, education level, marital status, income sufficiency, expected investment return, and preferred investment time horizon. These factors were chosen based on their potential to influence financial planning behavior and simple decision tree model is presented on the

Figure 6 (depth limited to 3rd level).

Initially, a standard decision tree classifier was implemented to identify the relationships between these variables and budgeting tendencies. The model underwent further refinement through hyperparameter tuning to enhance predictive accuracy. Using Grid Search with cross-validation, we explored optimal settings for key parameters, including maximum depth, minimum samples split, and minimum samples leaf. This optimization yielded the following best-performing parameters: a maximum depth of 7, a minimum samples split of 2, and a minimum samples leaf of 1.

The optimized decision tree model achieved a test accuracy of approximately 54.4%, with balanced performance across both classes (budget vs. no budget). Although this accuracy indicates moderate predictive power, the model effectively captures some underlying patterns in budgeting behavior. Cross-validation accuracy for the optimized model was slightly higher at 58.2%, suggesting consistency in performance across different data subsets. While further improvements could enhance accuracy, these results are valuable in identifying influential factors for budgeting decisions.

To visualize the model’s decision-making process, we displayed the first three levels of the tree to highlight the most significant splits. The top nodes revealed that education level and income sufficiency are particularly influential in predicting whether a household maintains a budget. Age group also emerged as a significant predictor, underscoring that budgeting habits may vary substantially across different stages of life.

A closer examination of the decision tree structure shows that households with higher educational attainment are more likely to have a budget. This finding aligns with existing literature suggesting that financial literacy, often correlated with higher education levels, contributes to proactive financial planning. Income sufficiency, another key predictor in the model, further suggests that households with stable and sufficient income are more inclined to create and adhere to a budget. The tree’s structure additionally indicates the sequential importance of these predictors, with marital status and investment preferences also contributing meaningfully to the model’s predictions.

While the model’s moderate accuracy highlights room for improvement, it provides valuable insights into the demographic and financial characteristics associated with budgeting. The interpretability of the decision tree model offers a clear advantage, as it visually demonstrates the stepwise influence of these factors, allowing for intuitive understanding of how each variable contributes to budgeting behavior. The model’s findings indicate that education, income stability, and age are primary determinants in household financial planning, reflecting broader socio-economic trends in financial literacy and resource management.

In conclusion, this decision tree model offers a foundational approach to identifying the predictors of household budgeting behavior, highlighting the importance of demographic and behavioral factors in financial planning. Future work could focus on refining the model through additional feature engineering or incorporating other relevant financial variables, which may capture more nuanced aspects of budgeting decisions and improve model accuracy.

5. Discussion

In Montenegro, a positive correlation between financial literacy and regular savings behavior may be attributed to the country’s economic volatility and high inflation rates. Financially literate individuals are more likely to understand the importance of saving as a buffer against economic uncertainty. Given the limited access to formal social safety nets in emerging economies like Montenegro, households may rely on personal savings to mitigate risks, making financial literacy a crucial determinant of economic resilience. Financially literate individuals are thus better positioned to protect themselves from income fluctuations, especially in a country where economic shocks from global market trends can disproportionately impact household income.

The correlation between higher financial literacy and responsible debt management in Montenegro likely stems from an increased awareness of the consequences of high-interest debt and its impact on long-term financial stability. Financial literacy equips individuals with the knowledge to compare loan terms and avoid predatory lending practices, which are often more prevalent in emerging economies. In Montenegro, where reliance on informal financial services can lead to cycles of unmanageable debt, financially literate individuals are more capable of seeking out favorable credit terms from formal institutions, thereby reducing their overall debt burden and enhancing household stability.

The observed trend where financially literate individuals are more willing to take calculated investment risks may be linked to their understanding of diversified income sources as a means to enhance financial security. In Montenegro’s economy, which is heavily reliant on tourism and service sectors, economically informed individuals might see the value in investing as a way to reduce dependence on potentially unstable income streams. Financially literate individuals are more likely to comprehend concepts like risk diversification, which allows them to balance risk and reward, contributing to economic resilience by promoting alternative income opportunities during economic downturns.

The correlation between financial literacy and a future-oriented financial outlook, including budgeting and long-term goal-setting, could be attributed to the limited availability of formal financial planning resources in Montenegro. With restricted access to financial advisors or planning services, individuals with higher financial literacy may be more proactive in setting long-term financial goals independently. This trend aligns with findings in other emerging economies, where financial literacy compensates for gaps in public financial support, encouraging individuals to plan for major life expenses, including education, retirement, or health emergencies, thus enhancing overall economic resilience.

The association between financial literacy and lower impulsive spending behaviors may be rooted in Montenegro’s high exposure to economic fluctuations. Financially literate individuals, aware of the risks posed by sudden economic downturns, may adopt cautious spending habits as a preventive measure. This prudent financial behavior likely results from an understanding of budgeting principles and the need for financial reserves to withstand economic disruptions. In a socioeconomic context where financial instability can severely impact household well-being, financially literate individuals may avoid unnecessary expenses to maintain financial security.

A key finding from our decision tree model indicates that certain demographic factors, such as education level and income, serve as significant predictors of financial literacy, which is consistent with previous studies by OECD (2016) and Cole, Sampson, and Zia (2011) [

17]. These studies have shown that individuals with higher education levels and stable incomes tend to have better financial literacy, leading to more secure financial behaviors. In Montenegro’s context, where a substantial portion of the population has limited access to financial education resources, these findings highlight the critical need for targeted educational programs.

The observed relationship between financial literacy and risk tolerance in investment decisions provides further insight. Our analysis shows that individuals with higher financial literacy are more likely to engage in calculated risk-taking, consistent with findings from Karlan, Ratan, and Zinman (2014) [

18]. This risk-taking, when informed by financial knowledge, can lead to improved financial outcomes, such as investment in diversified portfolios, ultimately contributing to household economic resilience. However, it’s also noted that a lack of financial literacy may lead to either excessive caution or uncalculated risks, highlighting the importance of financial education in fostering informed decision-making.

One interesting deviation from initial hypotheses was the weak correlation between financial literacy and short-term spending attitudes. Despite prior research suggesting that financially literate individuals are less impulsive in their spending, our model shows that cultural and socio-economic factors may mediate this relationship in Montenegro. This insight aligns with work by Beckmann (2013) on financial behaviors in Eastern European countries, suggesting that regional socio-cultural factors play a role in financial decision-making, sometimes limiting the impact of financial literacy alone on spending habits [

30].

The decision tree model developed in this study provides a structured approach to understanding the demographic and financial factors associated with household budgeting behavior. The model's performance, with an accuracy of 54.4%, highlights that while some predictive power exists, budgeting behavior is influenced by complex, multifaceted factors that may not be fully captured by this model alone. Nevertheless, the insights derived from the decision tree reveal important patterns and associations that are valuable for both academic understanding and practical application in financial education.

One of the most notable findings from the model is the strong influence of education level on budgeting behavior. Households with higher educational attainment are significantly more likely to maintain a budget, suggesting that financial literacy, which often accompanies higher education, is crucial for financial planning. This result aligns with existing research indicating that individuals with greater financial knowledge are more inclined to engage in proactive financial management practices, such as budgeting. This insight suggests that targeted financial literacy programs, particularly for individuals with lower levels of formal education, could improve financial planning behaviors and overall economic resilience.

Income sufficiency also emerged as a key determinant of budgeting behavior in the model, with households reporting stable and sufficient income being more likely to maintain a budget. This finding is consistent with economic theories suggesting that individuals with greater financial security are more capable of engaging in forward-looking financial planning, as they have the necessary resources to allocate toward future needs. Conversely, households facing income instability may focus on immediate expenses rather than long-term planning, which could hinder their ability to establish a budget. This insight emphasizes the importance of economic policies that support income stability, as a means to empower households to take a more structured approach to financial management.

Age group also proved to be a meaningful predictor, reflecting potential generational or life-stage differences in financial behavior. Younger individuals were generally less likely to budget, which could reflect limited experience with financial planning or lower income levels in early career stages. In contrast, middle-aged individuals, particularly those in their 30s and 40s, displayed higher rates of budgeting, likely reflecting increased financial responsibilities and the need to manage household expenses. This trend supports the view that financial behaviors evolve over the life course, underscoring the value of early financial education to instill budgeting habits before major financial responsibilities arise.

While the model’s interpretability is a strength, the moderate accuracy suggests limitations in its predictive power. This could be attributed to the complexity of financial behaviors, which are influenced by both observable characteristics and unobservable psychological and situational factors. For instance, attitudes toward risk, individual financial goals, and cultural norms surrounding financial practices are factors that likely impact budgeting but were not directly measured in this study. Future research could benefit from incorporating a broader range of variables, including psychological factors and personal financial attitudes, to enhance model accuracy.

These findings have practical implications. For policymakers in Montenegro, they underline the importance of tailoring financial education initiatives to address demographic-specific needs, such as targeting youth, lower-income households, and rural populations. Implementing financial literacy programs within school curricula, for instance, could improve long-term economic stability at a population level. Financial institutions might also use these insights to develop tools that support individuals in making informed decisions, thereby fostering economic resilience within vulnerable groups.

The impact of socio-cultural factors on financial behavior in Montenegro warrants further exploration. Cultural attitudes towards debt, saving, and investment can significantly influence individuals' financial decisions. For example, in communities where cash transactions are preferred over banking, financial literacy programs need to be tailored to address these cultural norms, ensuring better acceptance and effectiveness.

Future research should consider longitudinal studies to observe how financial literacy impacts economic stability over time, especially as Montenegro’s economy evolves. Additionally, further exploration into the socio-cultural factors influencing financial behaviors could provide a deeper understanding of how these elements interact with financial knowledge. Integrating qualitative methods to capture individuals’ perspectives on financial decision-making could also enrich the data, offering a comprehensive view of financial literacy’s role in economic resilience in Montenegro and comparable regions. At the same time exploring the effectiveness of various delivery methods for financial education—such as digital platforms versus in-person training—could yield valuable insights into the most effective means of enhancing financial literacy in diverse populations.

6. Conclusions

This study highlights the critical role of financial literacy in enhancing economic resilience and stability among individuals in Montenegro. By examining various financial behaviors, such as savings rates, debt management, and risk tolerance, the analysis shows a clear correlation between financial literacy and responsible financial decision-making. Financially literate individuals tend to have higher savings, better debt management skills, and are less vulnerable to economic shocks, indicating that financial education can be an essential tool in building financial security at the household level. The decision tree model developed in this study provides a foundational approach to understanding household budgeting behavior, highlighting the role of education, income sufficiency, and age in financial planning. These findings suggest that educational initiatives, income stability policies, and early financial education could positively influence budgeting practices and, by extension, financial resilience. While the model offers valuable insights, future studies should consider additional factors, including psychological and cultural variables, to more fully capture the complexity of budgeting behavior.

The results obtained from the research on targeted financial literacy programs support the hypothesis outlined in the paper regarding financial behaviors across different demographic groups. Financial literacy and budgeting practices across age groups demonstrate that middle-aged individuals exhibit higher financial literacy, as reflected in their greater propensity to maintain budgets. In contrast, younger and older individuals may lack the necessary knowledge or skills to plan effectively. Similarly, higher education levels correlate with increased financial literacy, enabling individuals to adopt diverse saving strategies, such as investments in financial instruments. On the other hand, those with lower educational attainment often show limited understanding and reliance on informal saving methods. Married individuals display better financial literacy through shared decision-making processes, which lead to improved budgeting and expense management. Furthermore, individuals with higher incomes tend to demonstrate greater financial literacy, as evidenced by their structured financial planning. Conversely, lower-income groups are more likely to lack budgeting practices, potentially due to limited knowledge or resources.

The results align with previous research that underscores the importance of financial literacy in emerging economies, where limited access to financial education often leaves populations more vulnerable to financial instability. These findings suggest that expanding financial literacy initiatives could have significant benefits, particularly in underbanked and rural areas, by fostering more sustainable economic growth. Future research could explore targeted interventions and the impact of digital financial education tools, further strengthening Montenegro’s economic resilience in an increasingly volatile global economy. In today’s increasingly digital economy, the role of digital financial literacy cannot be overlooked. As more Montenegrins turn to online banking and digital financial products, understanding how to navigate these platforms becomes vital. Educational programs should incorporate digital literacy components to ensure that individuals can effectively manage their finances in an online environment, thus enhancing overall financial stability.

This study contributes to a growing body of literature on the importance of financial literacy in promoting economic stability, making a compelling case for policymakers in Montenegro to prioritize financial education as part of their broader economic development strategy. Additionally, community workshops should be organized, focusing on practical financial skills such as budgeting, saving, and responsible credit use, particularly in underrepresented regions. Finally, collaboration with local financial institutions could facilitate the development of resources aimed at enhancing financial knowledge among Montenegrin citizens.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K. and I.M.; methodology, I.K. and G.R.; software, I.K. and G.R.; validation, M.K. and I.M.; formal analysis I.K., M.R. and G.R.; investigation, M.K. and I.M.; resources, M.R. and M.O.; data curation, G.R. and M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K. and M.O.; writing—review and editing, M.R., G.R. and M.K.; visualization, I.M. and M.R.; supervision, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of CENTER FOR FINANCE.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because they were used exclusively for the purposes of this research.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude for the support provided throughout this research. We would like to thank all colleagues from Center for Finance, Podgorica, Montenegro and University of Donja Gorica, Montenegro.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lusardi, A.; Mitchell, O.S. The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence. Journal of Economic Literature 2014, 52, 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.; Messy, F.-A. Measuring Financial Literacy: Results of the OECD/International Network on Financial Education (INFE) Pilot Study; OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance, and Private Pensions No. 15; OECD Publishing, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, L.; Lusardi, A.; van Oudheusden, P. Financial Literacy Around the World: Insights from the Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services Global Financial Literacy Survey. 2015. Available online: https://books.google.me/books?id=jhw0jwEACAAJ.

- OECD. OECD/INFE International Survey of Adult Financial Literacy Competencies; OECD Publishing, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulatovic, J. Financial Literacy as a Factor of Financial Stability and Economic Development in Montenegro. Journal of Central Banking Theory and Practice 2020, 9, 5–23. Available online: https://www.cbcg.me/en/journal/journal-of-central-banking-theory-and-practice.

- Antwi, P.K.A.; Addai, B.; Duah, E.; Kubi, M. The impact of financial literacy on financial well-being: a systematic literature review. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chettri, D.; Mothey, A.; Chhetri, D. An Empirical Analysis Of Financial Literacy And Its Impact On Financial Wellbeing. Educational Administration Theory and Practices 2024, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Montenegro Economic Update: Spring 2021.

- Kempson, E.; Finney, A.; Poppe, C. Financial Well-being: A Conceptual Model and Preliminary Analysis; OECD Working Papers on Finance, Insurance, and Private Pensions No. 44.; 2017; Available online: https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/geography/pfrc/pfrc1705-financial-well-being-conceptual-model.pdf.

- Cole, S.; Sampson, T.; Zia, B. Prices or Knowledge? What Drives Demand for Financial Services in Emerging Markets? Journal of Finance 2011, 66, 1933–1967. Available online: https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/09-117.pdf. [CrossRef]

- OECD. Financial Literacy in Eastern Europe and Central Asia: Results of OECD/INFE Survey of Adult Financial Literacy Competencies; OECD Publishing, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; de la Torre, A. The Basic Analytics of Access to Financial Services; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4026; 2007; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/586361468166156750/pdf/wps4026.pdf.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). Financial Literacy and Sustainable Development. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Financial Inclusion in the Western Balkans. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. The Role of Financial Literacy in Socioeconomic Development in Southeast Europe. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, T.; de la Torre, A. The Basic Analytics of Access to Financial Services; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 4026; 2007; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/586361468166156750/pdf/wps4026.pdf.

- Cole, S.; Sampson, T.; Zia, B. Prices or Knowledge? What Drives Demand for Financial Services in Emerging Markets? The Journal of Finance 2009, 66, 1933–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlan, D.; Ratan, A.; Zinman, J. Savings by and for the Poor: A Research Review on Financial Inclusion, NBER Working Paper No. 19762. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.V.; Karlan, D.; Zinman, J. Six Randomized Evaluations of Microcredit: Introduction and Further Steps. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 2015, 7, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Policy handbook on financial education in the workplace; OECD Business and Finance Policy Papers No. 7; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Špiranec, S.; Zorica, M.B.; Simončić, G.S. Libraries and financial literacy: Perspectives from emerging markets. Journal of Business & Finance Librarianship 2012, 17, 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Montenegro Economic Update: Managing the Impact of COVID-19. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kempson, E.; Finney, A.; Poppe, C. Financial well-being a conceptual model and preliminary analysis. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EBRD. Financial Inclusion in the Western Balkans; European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Katnic, M.; Katnic, I.; Jaksic-Stojanovic, A. From Negativne Interest Rates Toward Old Normality. 2023; 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; de la Torre, A. Financial Literacy and Financial Inclusion: The Role of Financial Education; World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 6864; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.F.; Singer, D. Financial Inclusion and Inclusive Growth: A Review of Recent Empirical Evidence. The World Bank Research Observer 2017, 32, 45–61. Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/pt/403611493134249446/pdf/WPS8040.pdf.

- Klapper, L.F.; Lusardi, A.; Panos, G.A. Financial Literacy and Its Consequences: Evidence from Russia during the Financial Crisis. Journal of Banking & Finance 2015, 50, 192–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathri, T.; Ganesan, S. Impact of Financial Education and Literacy on Investment Behaviour. International Journal for Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology 2023, 11, 2668–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckmann, E. Financial literacy and household savings in Romania. Numeracy 2013, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sconti, A. Having Trouble Making Ends Meet? Financial Literacy Makes the Difference. Italian Economic Journal 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choung, Y.; Chatterjee, S.; Pak, T.-Y. Digital financial literacy and financial well-being. 2023; 104438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, N.; Alagarsamy, S.; Hawaldar, A. Demographic characteristics influencing financial wellbeing: a multigroup analysis. Managerial Finance 2022. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, O.; Lusardi, A. Financial Literacy and Economic Outcomes: Evidence and Policy Implications. The Journal of Retirement 2015, 3, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; et al. The Interplay of Skills, Digital Financial Literacy, Capability, and Autonomy in Financial Decision Making and Well-Being. Borsa Istanbul Review 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riitsalu, L.; van Raaij, F. Current and Future Financial Well-Being in 16 Countries. Journal of International Marketing 2022, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, T.; et al. Competence, Confidence, and Gender: The Role of Objective and Subjective Financial Knowledge in Household Finance. Journal of Family and Economic Issues 2020, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J. Ability or opportunity to act: What shapes financial well-being? World Development 2020, 128, 104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrantes-Braga, F.D.; Veludo-de-Oliveira, T. Development and validation of financial well-being related scales. International Journal of Bank Marketing 2019, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggen, E.; et al. Financial well-being: A conceptualization and research agenda. Journal of Business Research 2017, 79, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooij, M.; Lusardi, A.; Alessie, R. Financial Literacy, Retirement Planning and Household Wealth*. Economic Journal 2011, 122, 449–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, A.; et al. Financial Literacy to Improve Sustainability: A Bibliometric Analysis. Studies in Business and Economics 2024, 18, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee Ying, T.; Tai, H.; Siang, T. Digital financial inclusion: A gateway to sustainable development. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-García, A.; et al. Financial literacy in SMEs: a bibliometric analysis and a systematic literature review of an emerging research field. Review of Managerial Science 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, J.; Salia, S.; Karimu, A. Is knowledge that powerful? Financial literacy and access to finance: An analysis of enterprises in the UK. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 2018, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frączek, B.; Monika, K. Financial literacy and its influence on young customers’ decision factors. Journal of Innovation Management 2015, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, M.; Bussoli, C.; Fattobene, L. Exploring financial graph literacy: determinants and influence on financial behavior. Qualitative Research in Financial Markets 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningtyas, M. The Role of Financial Literacy on Financial Behavior. JABE (Journal of Accounting and Business Education) 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Wellalage, N.; Hunjra, A.I. Digital Banking and Finance: A Handbook; 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Banerji, P. Systematic literature review on Digital Financial Literacy. SN Business & Economics 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhillar, N.; Arora, S.; Chawla, P. Measuring Digital Financial Literacy: Scale Development and Validation. 2024, 42, 145. [Google Scholar]

- Jose, J.; Ghosh, N. Digital Financial Literacy and Its Impact on Financial Behaviors: A Systematic Review. 2024, 147–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskelainen, T.; et al. Financial literacy in the digital age—A research agenda. Journal of Consumer Affairs 2023, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, A.; Kass-Hanna, J. A Methodological Overview to Defining and Measuring “Digital” Financial Literacy. Financial Planning Review 2021, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, N.; Singh, S. Financial literacy among youth. International Journal of Social Economics 2017, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, R.; Inclusion, F. Financial Literacy-The Demand Side of Financial Inclusion. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, O.; Lusardi, A. Financial Literacy and Economic Outcomes: Evidence and Policy Implications. SSRN Electronic Journal 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; et al. The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thosiac, S.-H. Why is Financial Literacy Important? SSRN Electronic Journal 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Chatterjee, S. Financial Socialization, Financial Education, and Student Loan Debt. Journal of Family and Economic Issues 2019, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, J.; Mylenko, N.; Ponce, A. Measuring Financial Access Around the World; The World Bank, Policy Research Working Paper Series; 2010. [Google Scholar]