Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

22 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

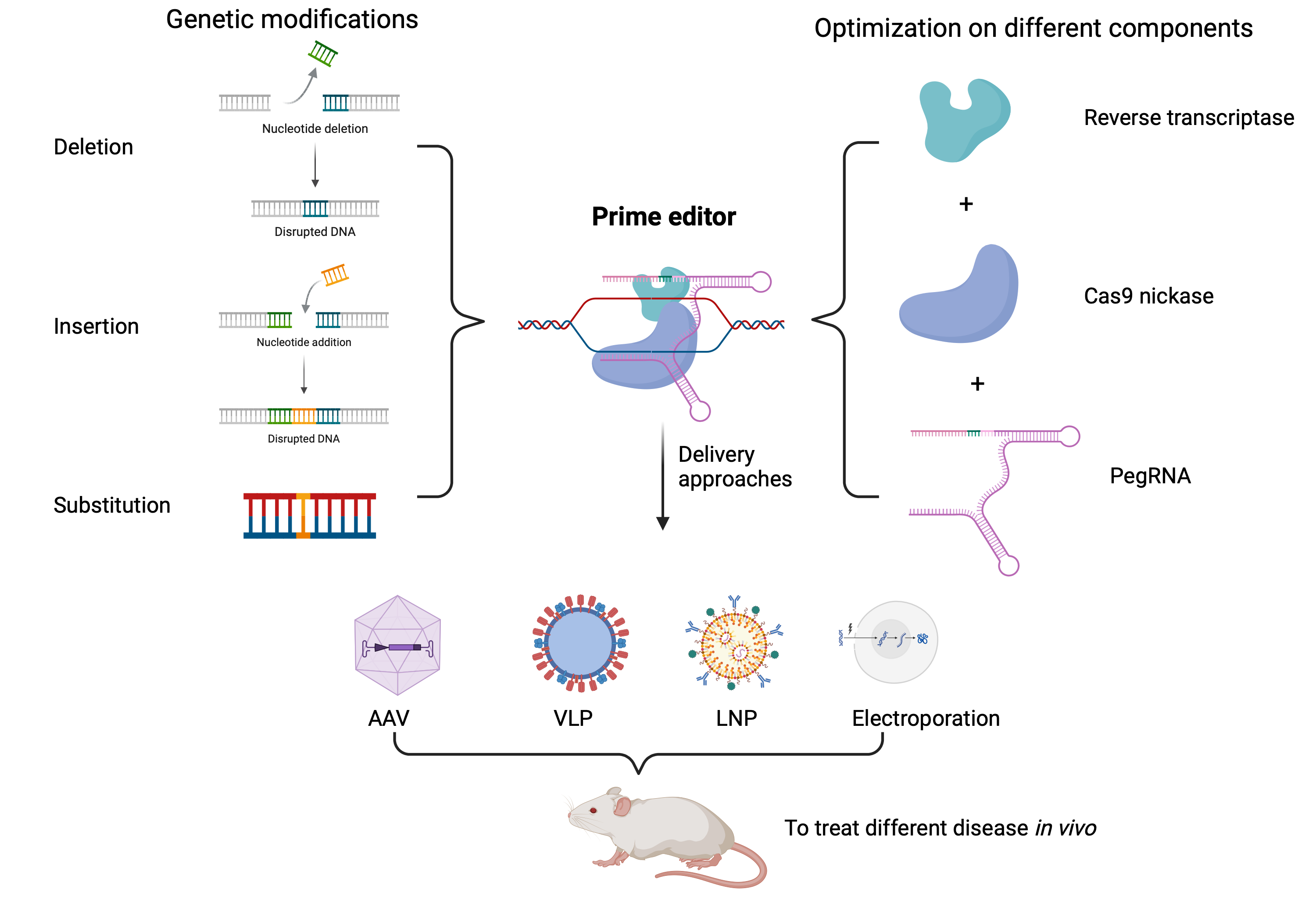

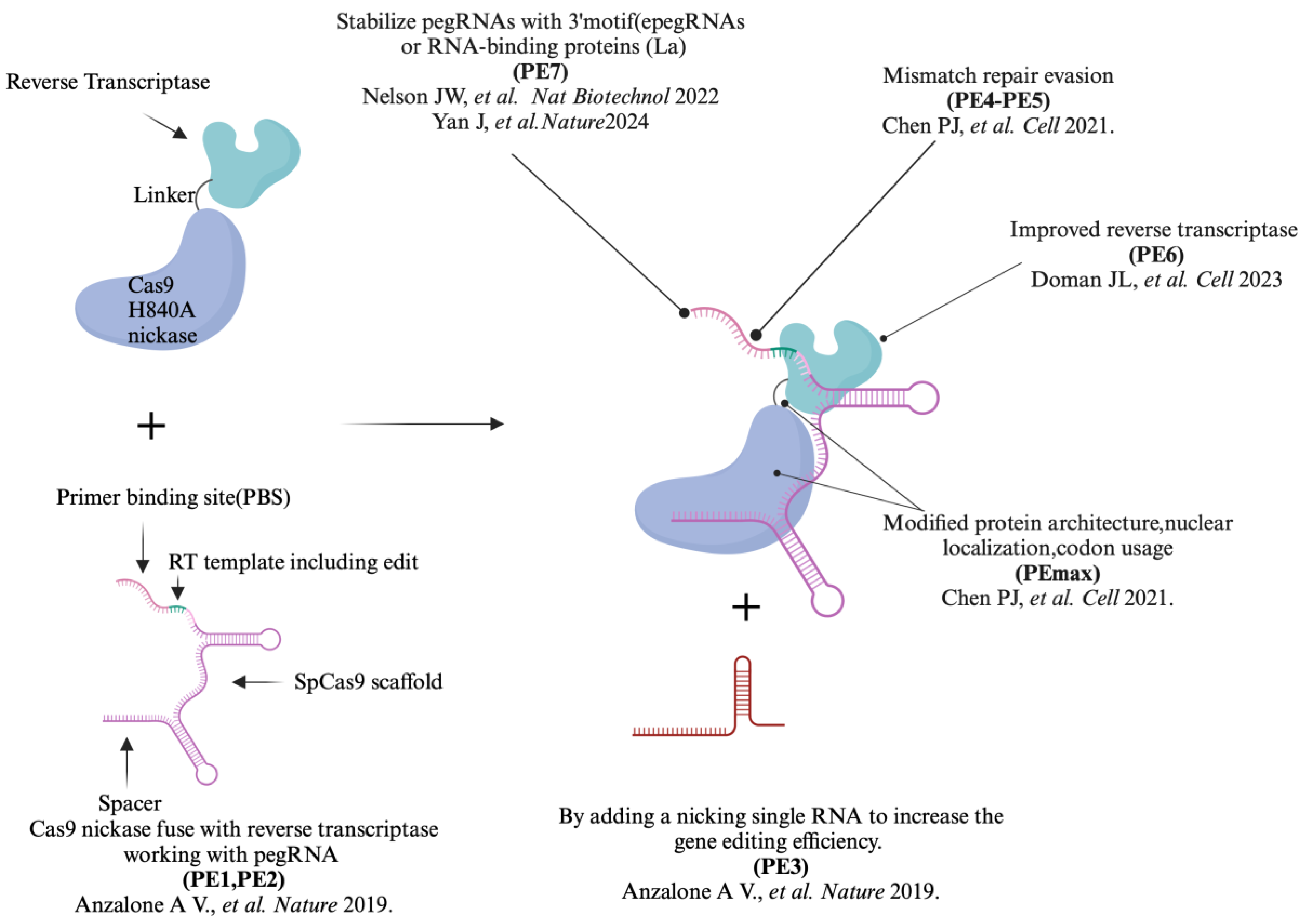

2. The Iteration of the Prime Editor from PE1 to PE7

3. Optimization of the Editing Range of Prime Editing

3.1. Insertion and Integration

3.2. Deletion

3.3. Transversion

4. Optimization of Prime Editor

4.1. Optimization of Cas Nickase

4.2. Optimization of RT

4.3. Optimization of pegRNA

5. PE Delivery Strategies

5.1. Viral Vectors

5.1.1. Adeno-Associated Viruses (AAV)

5.1.2. Adenovector Particles (AdVPs)

5.1.3. Helper-Dependent Adenovirus (HDAd)

5.2. Non-Viral Vectors

5.2.1. Lipid Nanoparticles

5.2.2. Virus-like Particles (VLPs)

6. Prime Editing in Therapeutic Applications

6.1. Creation of Pathogenic Cell Lines and Organoids

6.2. Creation of Pathogenic Animal Models

6.3. Correcting Mutations In Vitro

6.4. Correcting Mutations In Vivo

7. Conclusion and Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ran, F.A.; Hsu, P.D.; Wright, J.; Agarwala, V.; Scott, D.A.; Zhang, F. Genome Engineering Using the CRISPR-Cas9 System. Nat Protoc 2013, 8, 2281–2308. [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, A. V.; Randolph, P.B.; Davis, J.R.; Sousa, A.A.; Koblan, L.W.; Levy, J.M.; Chen, P.J.; Wilson, C.; Newby, G.A.; Raguram, A.; et al. Search-and-Replace Genome Editing without Double-Strand Breaks or Donor DNA. Nature 2019, 576, 149–157. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.J.; Hussmann, J.A.; Yan, J.; Knipping, F.; Ravisankar, P.; Chen, P.-F.; Chen, C.; Nelson, J.W.; Newby, G.A.; Sahin, M.; et al. Enhanced Prime Editing Systems by Manipulating Cellular Determinants of Editing Outcomes. Cell 2021, 184, 5635-5652.e29. [CrossRef]

- Doman, J.L.; Pandey, S.; Neugebauer, M.E.; An, M.; Davis, J.R.; Randolph, P.B.; McElroy, A.; Gao, X.D.; Raguram, A.; Richter, M.F.; et al. Phage-Assisted Evolution and Protein Engineering Yield Compact, Efficient Prime Editors. Cell 2023, 186, 3983-4002.e26. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Oyler-Castrillo, P.; Ravisankar, P.; Ward, C.C.; Levesque, S.; Jing, Y.; Simpson, D.; Zhao, A.; Li, H.; Yan, W.; et al. Improving Prime Editing with an Endogenous Small RNA-Binding Protein. Nature 2024, 628, 639–647. [CrossRef]

- Koeppel, J.; Weller, J.; Peets, E.M.; Pallaseni, A.; Kuzmin, I.; Raudvere, U.; Peterson, H.; Liberante, F.G.; Parts, L. Prediction of Prime Editing Insertion Efficiencies Using Sequence Features and DNA Repair Determinants. Nat Biotechnol 2023, 41, 1446–1456. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; He, Z.; Wang, G.; Zhang, R.; Duan, J.; Gao, P.; Lei, X.; Qiu, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Efficient Targeted Insertion of Large DNA Fragments without DNA Donors. Nat Methods 2022, 19, 331–340. [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, A. V.; Gao, X.D.; Podracky, C.J.; Nelson, A.T.; Koblan, L.W.; Raguram, A.; Levy, J.M.; Mercer, J.A.M.; Liu, D.R. Programmable Deletion, Replacement, Integration and Inversion of Large DNA Sequences with Twin Prime Editing. Nat Biotechnol 2022, 40, 731–740. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Liu, B.; Dong, X.; Gaston, N.; Sontheimer, E.J.; Xue, W. Template-Jumping Prime Editing Enables Large Insertion and Exon Rewriting in Vivo. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 3369. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.; Gao, X.D.; Krasnow, N.A.; McElroy, A.; Tao, Y.A.; Duby, J.E.; Steinbeck, B.J.; McCreary, J.; Pierce, S.E.; Tolar, J.; et al. Efficient Site-Specific Integration of Large Genes in Mammalian Cells via Continuously Evolved Recombinases and Prime Editing. Nat Biomed Eng 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yarnall, M.T.N.; Ioannidi, E.I.; Schmitt-Ulms, C.; Krajeski, R.N.; Lim, J.; Villiger, L.; Zhou, W.; Jiang, K.; Garushyants, S.K.; Roberts, N.; et al. Drag-and-Drop Genome Insertion of Large Sequences without Double-Strand DNA Cleavage Using CRISPR-Directed Integrases. Nat Biotechnol 2023, 41, 500–512. [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Lei, Y.; Li, B.; Gao, Q.; Li, Y.; Cao, W.; Yang, C.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; et al. Precise Integration of Large DNA Sequences in Plant Genomes Using PrimeRoot Editors. Nat Biotechnol 2024, 42, 316–327. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Chen, W.; Suiter, C.C.; Lee, C.; Chardon, F.M.; Yang, W.; Leith, A.; Daza, R.M.; Martin, B.; Shendure, J. Precise Genomic Deletions Using Paired Prime Editing. Nat Biotechnol 2022, 40, 218–226. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Zhang, X.-O.; Weng, Z.; Xue, W. Deletion and Replacement of Long Genomic Sequences Using Prime Editing. Nat Biotechnol 2022, 40, 227–234. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Happi Mbakam, C.; Song, B.; Bendavid, E.; Tremblay, J.-P. Improvements of Nuclease and Nickase Gene Modification Techniques for the Treatment of Genetic Diseases. Front Genome Ed 2022, 4. [CrossRef]

- Kweon, J.; Yoon, J.K.; Jang, A.H.; Shin, H.R.; See, J.E.; Jang, G.; Kim, J.I.; Kim, Y. Engineered Prime Editors with PAM Flexibility. Mol Ther 2021, 29, 2001–2007. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Gao, N.; Li, M.; Wang, D.; Wang, D.; Liu, D.; Liu, H.; Ong, S.-G.; et al. A Compact Cas9 Ortholog from Staphylococcus Auricularis (SauriCas9) Expands the DNA Targeting Scope. PLoS Biol 2020, 18, e3000686. [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Chen, H.; Tang, C.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. Mini-PE, a Prime Editor with Compact Cas9 and Truncated Reverse Transcriptase. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2023, 33, 890–897. [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.R.; Banskota, S.; Levy, J.M.; Newby, G.A.; Wang, X.; Anzalone, A. V.; Nelson, A.T.; Chen, P.J.; Hennes, A.D.; An, M.; et al. Efficient Prime Editing in Mouse Brain, Liver and Heart with Dual AAVs. Nat Biotechnol 2024, 42, 253–264. [CrossRef]

- Makarova, K.S.; Koonin, E. V. Annotation and Classification of CRISPR-Cas Systems. In; 2015; pp. 47–75.

- Chen, P.J.; Liu, D.R. Prime Editing for Precise and Highly Versatile Genome Manipulation. Nat Rev Genet 2023, 24, 161–177. [CrossRef]

- Liang, R.; He, Z.; Zhao, K.T.; Zhu, H.; Hu, J.; Liu, G.; Gao, Q.; Liu, M.; Zhang, R.; Qiu, J.-L.; et al. Prime Editing Using CRISPR-Cas12a and Circular RNAs in Human Cells. Nat Biotechnol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lim, K.; Kim, A.; Mok, Y.G.; Chung, E.; Cho, S.-I.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, J.-S. Prime Editing with Genuine Cas9 Nickases Minimizes Unwanted Indels. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 1786. [CrossRef]

- Gopalappa, R.; Suresh, B.; Ramakrishna, S.; Kim, H. (Henry) Paired D10A Cas9 Nickases Are Sometimes More Efficient than Individual Nucleases for Gene Disruption. Nucleic Acids Res 2018, 46, e71–e71. [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, V.P.; Sharp, P.A.; Langer, R. Engineered Prime Editors with Minimal Genomic Errors 2024.

- Oscorbin, I.P.; Filipenko, M.L. M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase: Selected Properties and Improved Mutants. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2021, 19, 6315–6327. [CrossRef]

- Telesnitsky, A.; Goff, S.P. RNase H Domain Mutations Affect the Interaction between Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus Reverse Transcriptase and Its Primer-Template. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1993, 90, 1276–1280. [CrossRef]

- Doman, J.L.; Pandey, S.; Neugebauer, M.E.; An, M.; Davis, J.R.; Randolph, P.B.; McElroy, A.; Gao, X.D.; Raguram, A.; Richter, M.F.; et al. Phage-Assisted Evolution and Protein Engineering Yield Compact, Efficient Prime Editors. Cell 2023, 186, 3983-4002.e26. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.J.; Hussmann, J.A.; Yan, J.; Knipping, F.; Ravisankar, P.; Chen, P.-F.; Chen, C.; Nelson, J.W.; Newby, G.A.; Sahin, M.; et al. Enhanced Prime Editing Systems by Manipulating Cellular Determinants of Editing Outcomes. Cell 2021, 184, 5635-5652.e29. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Ravendran, S.; Mikkelsen, N.S.; Haldrup, J.; Cai, H.; Ding, X.; Paludan, S.R.; Thomsen, M.K.; Mikkelsen, J.G.; Bak, R.O. A Truncated Reverse Transcriptase Enhances Prime Editing by Split AAV Vectors. Molecular Therapy 2022, 30, 2942–2951. [CrossRef]

- Mbisa, J.L.; Nikolenko, G.N.; Pathak, V.K. Mutations in the RNase H Primer Grip Domain of Murine Leukemia Virus Reverse Transcriptase Decrease Efficiency and Accuracy of Plus-Strand DNA Transfer. J Virol 2005, 79, 419–427. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Baker, S.L.; Bowler, M.W.; Chen, B.J.; Chen, C.; Hogg, J.R.; Goff, S.P.; Song, H. Structural Basis of Suppression of Host Translation Termination by Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 12070. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Liang, S.-Q.; Liu, B.; Liu, P.; Kwan, S.-Y.; Wolfe, S.A.; Xue, W. A Flexible Split Prime Editor Using Truncated Reverse Transcriptase Improves Dual-AAV Delivery in Mouse Liver. Molecular Therapy 2022, 30, 1343–1351. [CrossRef]

- Böck, D.; Rothgangl, T.; Villiger, L.; Schmidheini, L.; Matsushita, M.; Mathis, N.; Ioannidi, E.; Rimann, N.; Grisch-Chan, H.M.; Kreutzer, S.; et al. In Vivo Prime Editing of a Metabolic Liver Disease in Mice. Sci Transl Med 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Chen, H.; Tang, C.; Wei, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, M.; Zhou, X.; et al. Mini-PE, a Prime Editor with Compact Cas9 and Truncated Reverse Transcriptase. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2023, 33, 890–897. [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xue, C.; Li, B.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, G.; Huang, X.; Cao, X.; et al. An Engineered Prime Editor with Enhanced Editing Efficiency in Plants. Nat Biotechnol 2022, 40, 1394–1402. [CrossRef]

- Grünewald, J.; Miller, B.R.; Szalay, R.N.; Cabeceiras, P.K.; Woodilla, C.J.; Holtz, E.J.B.; Petri, K.; Joung, J.K. Engineered CRISPR Prime Editors with Compact, Untethered Reverse Transcriptases. Nat Biotechnol 2023, 41, 337–343. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Dong, X.; Cheng, H.; Zheng, C.; Chen, Z.; Rodríguez, T.C.; Liang, S.-Q.; Xue, W.; Sontheimer, E.J. A Split Prime Editor with Untethered Reverse Transcriptase and Circular RNA Template. Nat Biotechnol 2022, 40, 1388–1393. [CrossRef]

- Petrova, I.O.; Smirnikhina, S.A. The Development, Optimization and Future of Prime Editing. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 17045. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Yu, G.; Seo, S.-Y.; Yang, J.; Kim, H.H. SynDesign: Web-Based Prime Editing Guide RNA Design and Evaluation Tool for Saturation Genome Editing. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, W121–W125. [CrossRef]

- Mathis, N.; Allam, A.; Tálas, A.; Kissling, L.; Benvenuto, E.; Schmidheini, L.; Schep, R.; Damodharan, T.; Balázs, Z.; Janjuha, S.; et al. Machine Learning Prediction of Prime Editing Efficiency across Diverse Chromatin Contexts. Nat Biotechnol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.W.; Randolph, P.B.; Shen, S.P.; Everette, K.A.; Chen, P.J.; Anzalone, A. V.; An, M.; Newby, G.A.; Chen, J.C.; Hsu, A.; et al. Engineered PegRNAs Improve Prime Editing Efficiency. Nat Biotechnol 2022, 40, 402–410. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Liu, Y.; Huang, S.; Qu, S.; Cheng, D.; Yao, Y.; Ji, Q.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Liu, J. Enhancement of Prime Editing via XrRNA Motif-Joined PegRNA. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 1856. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Liu, S.; Mo, Q.; Xiao, X.; Liu, P.; Ma, H. Enhancing Prime Editing Efficiency and Flexibility with Tethered and Split PegRNAs. Protein Cell 2022. [CrossRef]

- Cirincione, A.; Simpson, D.; Ravisankar, P.; Solley, S.C.; Yan, J.; Singh, M.; Adamson, B. A Benchmarked, High-Efficiency Prime Editing Platform for Multiplexed Dropout Screening. bioRxiv 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ponnienselvan, K.; Liu, P.; Nyalile, T.; Oikemus, S.; Maitland, S.A.; Lawson, N.D.; Luban, J.; Wolfe, S.A. Reducing the Inherent Auto-Inhibitory Interaction within the PegRNA Enhances Prime Editing Efficiency. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, 6966–6980. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Petri, K.; Ma, J.; Lee, H.; Tsai, C.-L.; Joung, J.K.; Yeh, J.-R.J. Enhancing CRISPR Prime Editing by Reducing Misfolded PegRNA Interactions. Elife 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, L.; Gao, B.-Q.; Li, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Wei, J.; Han, W.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; et al. Highly Efficient Prime Editing by Introducing Same-Sense Mutations in PegRNA or Stabilizing Its Structure. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 1669. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, F.; Thornton, E.L.; Wang, B. An Expanded Library of Orthogonal Split Inteins Enables Modular Multi-Peptide Assemblies. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 1529. [CrossRef]

- She, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Jin, X.; Yang, Y.; Su, J.; Li, R.; Song, L.; Xiao, J.; Yao, S.; et al. Dual-AAV Split Prime Editor Corrects the Mutation and Phenotype in Mice with Inherited Retinal Degeneration. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 57. [CrossRef]

- Zhi, S.; Chen, Y.; Wu, G.; Wen, J.; Wu, J.; Liu, Q.; Li, Y.; Kang, R.; Hu, S.; Wang, J.; et al. Dual-AAV Delivering Split Prime Editor System for in Vivo Genome Editing. Molecular Therapy 2022, 30, 283–294. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Ravendran, S.; Mikkelsen, N.S.; Haldrup, J.; Cai, H.; Ding, X.; Paludan, S.R.; Thomsen, M.K.; Mikkelsen, J.G.; Bak, R.O. A Truncated Reverse Transcriptase Enhances Prime Editing by Split AAV Vectors. Molecular Therapy 2022, 30, 2942–2951. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Capelletti, S.; Liu, J.; Janssen, J.M.; Gonçalves, M.A.F. V Selection-Free Precise Gene Repair Using High-Capacity Adenovector Delivery of Advanced Prime Editing Systems Rescues Dystrophin Synthesis in DMD Muscle Cells. Nucleic Acids Res 2024, 52, 2740–2757. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Georgakopoulou, A.; Newby, G.A.; Chen, P.J.; Everette, K.A.; Paschoudi, K.; Vlachaki, E.; Gil, S.; Anderson, A.K.; Koob, T.; et al. In Vivo HSC Prime Editing Rescues Sickle Cell Disease in a Mouse Model. Blood 2023. [CrossRef]

- Rosewell, A.; Vetrini, F. Helper-Dependent Adenoviral Vectors. J Genet Syndr Gene Ther 2011, 2. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Kelly, K.; Cheng, H.; Dong, X.; Hedger, A.K.; Li, L.; Sontheimer, E.J.; Watts, J.K. In Vivo Prime Editing by Lipid Nanoparticle Co-Delivery of Chemically Modified PegRNA and Prime Editor MRNA. GEN Biotechnology 2023, 2, 490–502. [CrossRef]

- An, M.; Raguram, A.; Du, S.W.; Banskota, S.; Davis, J.R.; Newby, G.A.; Chen, P.Z.; Palczewski, K.; Liu, D.R. Engineered Virus-like Particles for Transient Delivery of Prime Editor Ribonucleoprotein Complexes in Vivo. Nat Biotechnol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Schene, I.F.; Joore, I.P.; Oka, R.; Mokry, M.; van Vugt, A.H.M.; van Boxtel, R.; van der Doef, H.P.J.; van der Laan, L.J.W.; Verstegen, M.M.A.; van Hasselt, P.M.; et al. Prime Editing for Functional Repair in Patient-Derived Disease Models. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 5352. [CrossRef]

- Binder, S.; Ramachandran, H.; Hildebrandt, B.; Dobner, J.; Rossi, A. Prime-Editing of Human ACTB in Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells to Model Human ACTB Loss-of-Function Diseases and Compensatory Mechanisms. Stem Cell Res 2024, 75, 103304. [CrossRef]

- Geurts, M.H.; de Poel, E.; Pleguezuelos-Manzano, C.; Oka, R.; Carrillo, L.; Andersson-Rolf, A.; Boretto, M.; Brunsveld, J.E.; van Boxtel, R.; Beekman, J.M.; et al. Evaluating CRISPR-Based Prime Editing for Cancer Modeling and CFTR Repair in Organoids. Life Sci Alliance 2021, 4, e202000940. [CrossRef]

- Petri, K.; Zhang, W.; Ma, J.; Schmidts, A.; Lee, H.; Horng, J.E.; Kim, D.Y.; Kurt, I.C.; Clement, K.; Hsu, J.Y.; et al. CRISPR Prime Editing with Ribonucleoprotein Complexes in Zebrafish and Primary Human Cells. Nat Biotechnol 2022, 40, 189–193. [CrossRef]

- Abuhamad, A.Y.; Mohamad Zamberi, N.N.; Sheen, L.; Naes, S.M.; Mohd Yusuf, S.N.H.; Ahmad Tajudin, A.; Mohtar, M.A.; Amir Hamzah, A.S.; Syafruddin, S.E. Reverting TP53 Mutation in Breast Cancer Cells: Prime Editing Workflow and Technical Considerations. Cells 2022, 11, 1612. [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Ureña-Bailén, G.; Mohammadian Gol, T.; Gratz, P.G.; Gratz, H.P.; Roig-Merino, A.; Antony, J.S.; Lamsfus-Calle, A.; Daniel-Moreno, A.; Handgretinger, R.; et al. Challenges in Gene Therapy for Somatic Reverted Mosaicism in X-Linked Combined Immunodeficiency by CRISPR/Cas9 and Prime Editing. Genes (Basel) 2022, 13, 2348. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Liu, X.; Lu, Z.; Huang, S.; Wu, S.; Yu, W.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Huang, X.; Sun, Q.; et al. Modeling a Cataract Disorder in Mice with Prime Editing. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2021, 25, 494–501. [CrossRef]

- Salem, A.R.; Bryant, W.B.; Doja, J.; Griffin, S.H.; Shi, X.; Han, W.; Su, Y.; Verin, A.D.; Miano, J.M. Prime Editing in Mice with an Engineered PegRNA. Vascul Pharmacol 2024, 154, 107269. [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Zhao, D.; Sui, T.; Chen, M.; Liu, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, T.; Chen, S.; Lai, L.; Li, Z. Efficient and Precise Generation of Tay–Sachs Disease Model in Rabbit by Prime Editing System. Cell Discov 2021, 7, 50. [CrossRef]

- Frisch, A.; Colombo, R.; Michaelovsky, E.; Karpati, M.; Goldman, B.; Peleg, L. Origin and Spread of the 1278insTATC Mutation Causing Tay-Sachs Disease in Ashkenazi Jews: Genetic Drift as a Robust and Parsimonious Hypothesis. Hum Genet 2004, 114, 366–376. [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Liu, Q.; Xu, J.; Xin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ye, Y.; Luo, H.; Zhang, X.; Xu, X.; Xu, P. Prime Editing of the α-Thalassemia Hb Constant Spring Mutation. Blood 2023, 142, 5001–5001. [CrossRef]

- Heath, J.M.; Stuart Orenstein, J.; Tedeschi, J.G.; Ng, A.; Collier, M.D.; Kushakji, J.; Wilhelm, A.J.; Taylor, A.; Waterman, D.P.; De Ravin, S.S.; et al. Prime Editing Efficiently and Precisely Corrects Causative Mutation in Chronic Granulomatous Disease, Restoring Myeloid Function: Toward Development of a Prime Edited Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Therapy. Blood 2023, 142, 7129–7129. [CrossRef]

- Happi Mbakam, C.; Rousseau, J.; Lu, Y.; Bigot, A.; Mamchaoui, K.; Mouly, V.; Tremblay, J.P. Prime Editing Optimized RTT Permits the Correction of the c.8713C>T Mutation in DMD Gene. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2022, 30, 272–285. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Qu, K.; Curci, B.; Yang, H.; Bolund, L.; Lin, L.; Luo, Y. Comparison of In-Frame Deletion, Homology-Directed Repair, and Prime Editing-Based Correction of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Mutations. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 870. [CrossRef]

- Bijker, L.E.; Uyttebroeck, S.; Hauser, B.; Vandenplas, Y.; Huysentruyt, K. Variants in DGAT1 Causing Enteropathy: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Belgian Journal of Paediatrics 2023, 23, 275–279.

- Peterkova, L.; Racková, M.; Svaton, M.; Riha, P.; Novotna, D.; Sedlacek, P.; Sramkova, L.; Skvarova, K. P754: PRIME EDITING AS A NOVEL TOOL FOR PRECISE CORRECTION OF CAUSAL MUTATIONS IN FANCONI ANAEMIA GROUP A PATIENT-DERIVED CELLS. Hemasphere 2023, 7, e27248b5. [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; Wang, F.; Tan, Z.; Zhang, S.; Lai, X.; Ou, W.; Yang, C.; Chen, H.; Peng, H.; Luo, P.; et al. Precise Correction of Lhcgr Mutation in Stem Leydig Cells by Prime Editing Rescues Hereditary Primary Hypogonadism in Mice. Advanced Science 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- da Costa, B.L.; Jenny, L.A.; Maumenee, I.H.; Tsang, S.H.; Quinn, P.M.J. Analysis of CRB1 Pathogenic Variants Correctable with CRISPR Base and Prime Editing. In; 2023; pp. 103–107.

- Jang, G.; Shin, H.R.; Do, H.-S.; Kweon, J.; Hwang, S.; Kim, S.; Heo, S.H.; Kim, Y.; Lee, B.H. Therapeutic Gene Correction for Lesch-Nyhan Syndrome Using CRISPR-Mediated Base and Prime Editing. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2023, 31, 586–595. [CrossRef]

- Godbout, K.; Rousseau, J.; Tremblay, J.P. Successful Correction by Prime Editing of a Mutation in the RYR1 Gene Responsible for a Myopathy. Cells 2023, 13, 31. [CrossRef]

- de Serres, F.J.; Blanco, I.; Fernández-Bustillo, E. Health Implications of A1-Antitrypsin Deficiency in Sub-Sahara African Countries and Their Emigrants in Europe and the New World. Genetics in Medicine 2005, 7, 175–184. [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Huang, Y.; Tian, F.; Li, J.; Xu, C.; Wei, Y.; Liu, J.; Guo, Q.; Xu, H.; Zhan, L.; et al. Prime Editing-Based Gene Correction Alleviates the Hyperexcitable Phenotype and Seizures of a Genetic Epilepsy Mouse Model. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2023, 44, 2342–2345. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Kelly, K.; Cheng, H.; Dong, X.; Hedger, A.K.; Li, L.; Sontheimer, E.J.; Watts, J.K. In Vivo Prime Editing by Lipid Nanoparticle Co-Delivery of Chemically Modified PegRNA and Prime Editor MRNA. GEN Biotechnology 2023, 2, 490–502. [CrossRef]

- Böck, D.; Rothgangl, T.; Villiger, L.; Schmidheini, L.; Matsushita, M.; Mathis, N.; Ioannidi, E.; Rimann, N.; Grisch-Chan, H.M.; Kreutzer, S.; et al. In Vivo Prime Editing of a Metabolic Liver Disease in Mice. Sci Transl Med 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, D.L.; Whittaker, M.N.; Qu, P.; Musunuru, K.; Ahrens-Nicklas, R.C.; Wang, X. Efficient in Vivo Prime Editing Corrects the Most Frequent Phenylketonuria Variant, Associated with High Unmet Medical Need. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2023, 110, 2003–2014. [CrossRef]

- An, M.; Raguram, A.; Du, S.W.; Banskota, S.; Davis, J.R.; Newby, G.A.; Chen, P.Z.; Palczewski, K.; Liu, D.R. Engineered Virus-like Particles for Transient Delivery of Prime Editor Ribonucleoprotein Complexes in Vivo. Nat Biotechnol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.-A.; Kim, S.-E.; Lee, A.-Y.; Hwang, G.-H.; Kim, J.H.; Iwata, H.; Kim, S.-C.; Bae, S.; Lee, S.E. Therapeutic Base Editing and Prime Editing of COL7A1 Mutations in Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa. Molecular Therapy 2022, 30, 2664–2679. [CrossRef]

- Everette, K.A.; Newby, G.A.; Levine, R.M.; Mayberry, K.; Jang, Y.; Mayuranathan, T.; Nimmagadda, N.; Dempsey, E.; Li, Y.; Bhoopalan, S.V.; et al. Ex Vivo Prime Editing of Patient Haematopoietic Stem Cells Rescues Sickle-Cell Disease Phenotypes after Engraftment in Mice. Nat Biomed Eng 2023, 7, 616–628. [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Jo, D.H.; Cho, C.S.; Shin, J.H.; Seo, J.H.; Yu, G.; Gopalappa, R.; Kim, D.; Cho, S.-R.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Application of Prime Editing to the Correction of Mutations and Phenotypes in Adult Mice with Liver and Eye Diseases. Nat Biomed Eng 2021, 6, 181–194. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, P.D.; Delgado, E.R.; Alencastro, F.; Leek, M.P.; Roy, N.; Weirich, M.P.; Stahl, E.C.; Otero, P.A.; Chen, M.I.; Brown, W.K.; et al. The Polyploid State Restricts Hepatocyte Proliferation and Liver Regeneration in Mice. Hepatology 2019, 69, 1242–1258. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Hong, S.-A.; Yu, J.; Eom, J.; Jang, K.; Yoon, S.; Hong, D.H.; Seo, D.; Lee, S.-N.; Woo, J.-S.; et al. Adenine Base Editing and Prime Editing of Chemically Derived Hepatic Progenitors Rescue Genetic Liver Disease. Cell Stem Cell 2021, 28, 1614-1624.e5. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Zhang, X.-O.; Weng, Z.; Xue, W. Deletion and Replacement of Long Genomic Sequences Using Prime Editing. Nat Biotechnol 2022, 40, 227–234. [CrossRef]

| Prime Editors |

Description | Efficiency | Key Features |

| PE1 | The original prime editor, utilizing a Cas9 nickase (H840A) fuse with reverse transcriptas (RT) and a pegRNA | 0.7-5.5% | Lower efficiency; foundational design for subsequent improvements. |

| PE2 | An improved version of PE1, incorporating 5 mutation points into RT changes | 1.6 to 5.1- fold compared to PE1 | Efficiency improved significantly and reduced off-target effects |

| PE3 | Further enhances PE2 by using additional sgRNA to achieve more precise editing | 3 - fold compare to PE2 | Increased targeting range, higher efficiency but with higher indels. |

| PE4 | A more advanced version of PE2 by adding a mismatch repair (MMR)-inhibiting protein | 7.7 - fold compared to PE2 | Enhance editing outcomes through co-expression of dominant negative MLH1 based on PE2 |

| PE5 | Advanced version of PE3 by adding a mismatch repair (MMR)-inhibiting protein | 2.0 - fold compared to PE3 | Enhance editing outcomes through co-expression of dominant negative MLH1 based on PE3 |

| PEmax | Advanced version of PE2, varying RT codon usage, SpCas9 nickase mutations, NLS sequences and the length and composition of peptide linkers between nCas9 and RT |

Higher than PE3 and PE5 | Further improvements in editing capabilities and versatility |

| PE6 | Optimization on Cas9 nickase and RT based on PEmax | 23 - fold compared to PEmax△RNaseH | PE6a to PE6d, which offered improvements in editor size (PE6a and b) and RT activity (PE6c and d); PE6e-g were based on using various evolved and engineered Cas9 variants |

| PE7 | PE7 is the PEmax system fused to a truncated La protein. | 5.2-fold improvement compared to PEmax | Stabilizing exogenous small RNAs therein, which avoid the pegRNA degradation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).