Submitted:

20 November 2024

Posted:

21 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phase 1: Translation and Adaptation Process

2.2. Phase 2: Validation Process

2.3. Descriptive Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Cognitive Piloting

3.2. Psychometric Study

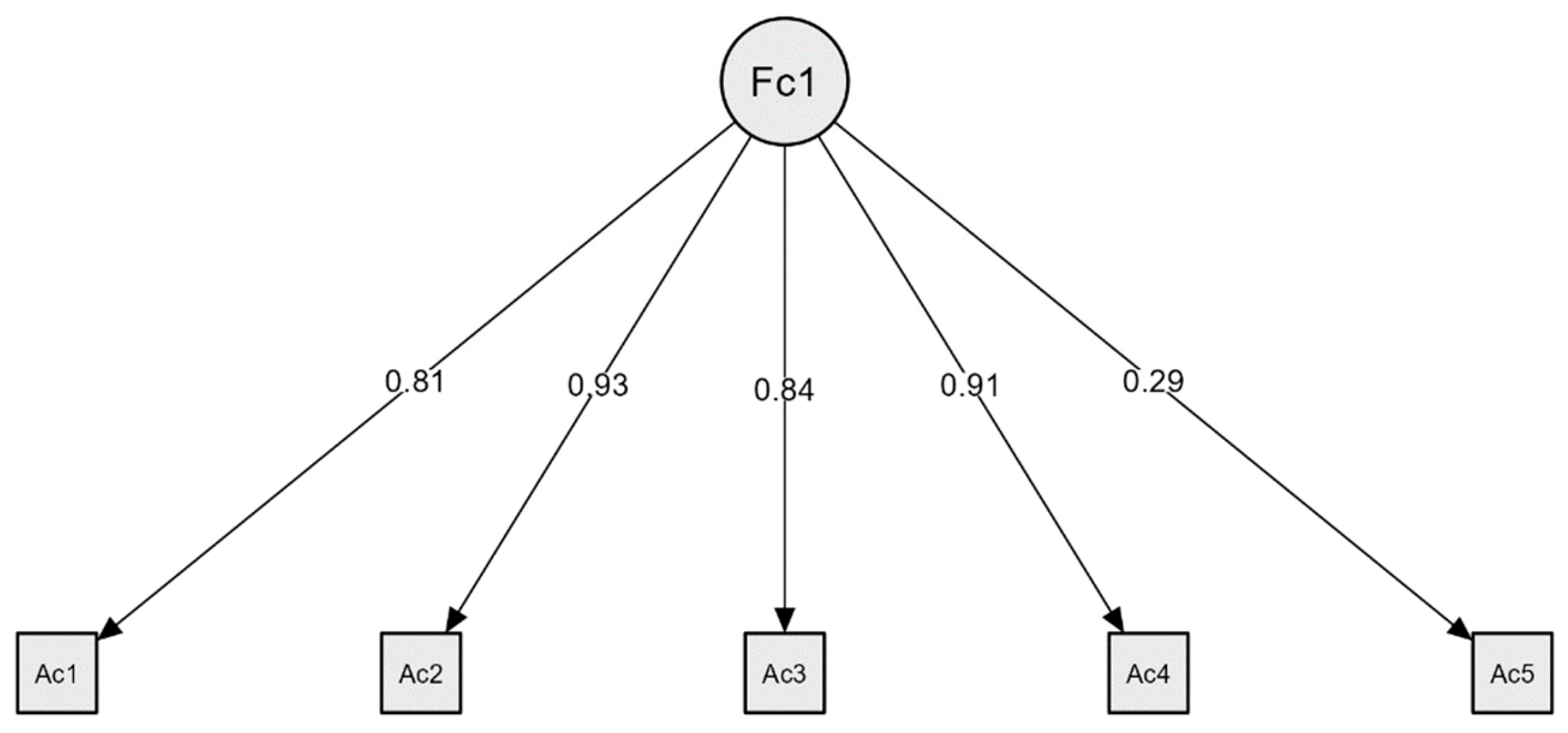

3.2.1. Attitude Scale (SANS_2)

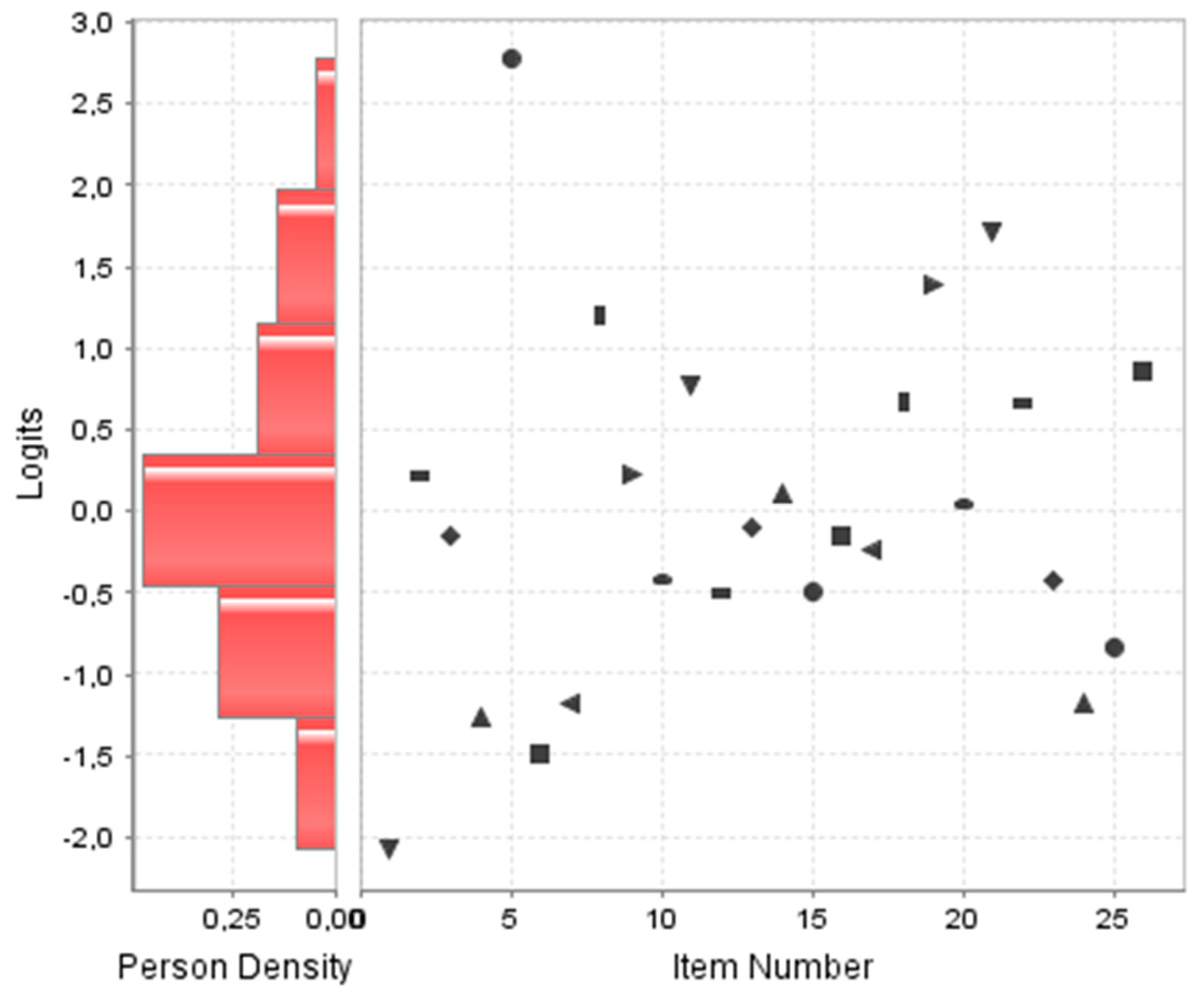

3.2.2. Rasch Model of the Knowledge Scale (ChEHK-Q)

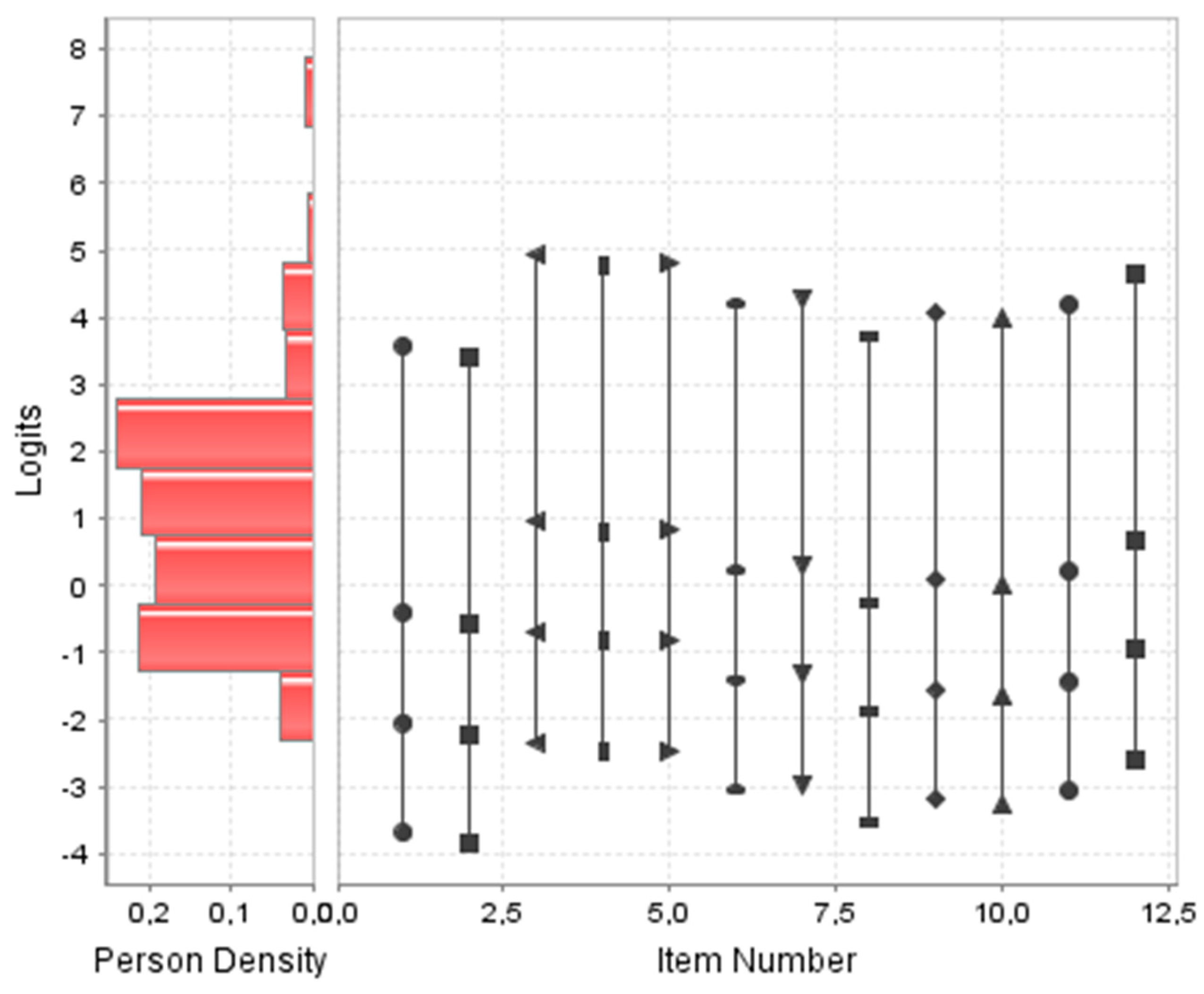

3.2.3. Rating Scaling Model of the Ability Scale (ChEHS-Q)

3.3. Descriptive Analysis of the Questionnaire

3.4. Bivariate analysis of the questionnaire

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix E

References

- World Meteorological Organization. State of the Global Climate 2023. Available online: https://library.wmo.int/viewer/68835/?offset=#page=1&viewer=picture&o=download&n=0&q (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- World Health Organisation. Climate change. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Arnell, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Belesova, K.; Berry, H.; et al. The 2018 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Shaping the health of nations for centuries to come. Lancet 2018, 392, 2479–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrís-i-Tortajada, J.; Ortega-García, J.A.; López-Andreu, J.A.; Ortí-Martín, A.; Aliaga-Vera, J.; García-i-Castell, J.; Cánovas-Conesa, A. Pediatric environmental health: A new professional challenge. Rev. Española Pediatr. 2002, 58, 304–314. [Google Scholar]

- McBridge, D.L. How Climate Change Affects Children´s Health. J. Peadiatr. Nurs. 2016, 31, 350–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zayas-Mujica, R.; Cabrera-Cárdenas, U. Environmental toxics and their impact on children's health. Rev. Cubana Pediatr. 2007, 79, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega García, J.A.; Ferrís-i-Tortajada, J.; Sánchez-Solís-de-Querol, M. Healthy environments for children and adolescents. In Outpatient Pediatrics; Ergón: Madrid, España, 2008; pp. 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children's Fund. In The impact of climate change on children in Spain; Madrid, Spain, 2017.

- Parsons, E.S.; Jowell, A.; Veidis, E.; Barry, M.; Israni, S.T. Climate change and inequality. Pediatr. Res. in press. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzel, R.A. Environmental Hazards that Matter for Children's Health. Hong Kong J. Paediatr. 2015, 20, 86–94. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, E.; Walpole, S.; McLean, M.; Alvarez-Nieto, C.; Barna, S.; Bazin, K.; et al. AMEE consensus statement: Planetary health and education for sustainable healthcare. Med. Teach. 2021, 43, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-García, C.; Álvarez-Nieto, C.; Sanz-Martos, S.; Puente-Fernández, D.; López-Leiva, I.; Gutiérrez-Puertas, L.; et al. Undergraduate nursing students' attitudes, knowledge, and skills related to children's environmental health. J. Nurs. Educ. 2019, 58, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J.; Heidenreich, T.; Álvarez-Nieto, C.; Fasseur, F.; Grose, J.; Huss, N.; et al. Including sustainability issues in nurse education: A comparative study of first year student nurses' attitudes in four European countries. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 37, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-García, C.; Álvarez-Nieto, C.; Pancorbo-Hidalgo, P.L.; Sanz-Martos, S.; López-Medina, I.M. Student nurses’ knowledge and skills of children’s environmental health: Instrument development and psychometric analysis using item response theory. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 69, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.J.; Jang, S.J.; Lee, H. Validation of the Sustainability Attitudes in Nursing Survey-2 for nurses: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ. Prac. 2024, 75, 103898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, K.; Chen, Q.; Fang, H.; Liu, S. Psychometric validation of the children's environmental health questionnaires in community nurses. Public Health Nurs. 2022, 39, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-García, C.; Álvarez-Nieto, C.; Carter, R.; Kelsey, J.; Sanz-Martos, S.; López-Medina, I.M. Cross-cultural adaptation of children’s environmental health questionnaires for nursing students in England. Health Educ. J. 2020, 79, 826–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Test Commission. The ITC Guidelines for Translating and Adapting Tests, 2nd ed.; 2017. Available online: https://www.intestcom.org/files/guideline_test_adaptation_2ed.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. Developing and testing self-report scales. In Nursing Research, Generating and Assessing Evidence for Nursing Practice, 8th ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, United States of America; pp. 474–505.

- Navas, M.J. Classical Test Theory vs. Item Response Theory. Psicol. 1994, 15, 175–208. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Alfaro, K.; Montero-Rojas, E. Application of the Rasch model in the psychometric analysis of a mathematical diagnostic test. Rev. Digi. Mat. 2013, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Ledesma, R.D.; Valero-Mora, P. Determining the Number of Factors to Retain in EFA: An easy-to-use computer program for carrying out Parallel Analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2007, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto Adánez, G.A.; Delgado González, A.R. Analysis of a test using the Rasch model. Psicotema 2003, 15, 94–100. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, K.B.; Makransky, G.; Horton, M. Critical values for Yen’s Q3: Identification of local dependence in the Rasch model using residual correlations. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 2017, 41, 178–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackman, I.R.; Giles, T. Psychometric evaluation of a self-report evidence-based practice tool using Rasch analysis. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 2015, 12, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P. Applied measurement with JMetrik. Routledge: New York, United Stated of America; 2014.

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I.H. Psychometric theory, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: Mexico, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Efstathiou, G. Translation, adaptation and validation process of research instruments. In Individualized care: Theory, measurement, research and practice; Suohnen, R., Stolt, M., Papatravou, E., Eds.; Springer: New Zealand, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- American Educational Research Association. Test design and development. In Standards for educational and psychological testing; 2014; pp. 81–84.

- Muñiz Fernández, J. Test theories: Classical theory and item response theory. Pap. Psi. 2010, 31, 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- International council of nurses. ICN code of ethics for nurses. Available online: https://www.icn.ch/resources/publications-and-reports/icn-code-ethics-nurses (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J.W. Best Practices in Exploratory Factor Analysis: Four Recommendations for Getting the Most From Your Analysis. Practical Assessment 2004, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.J.; Price, A.M. Comparing undergraduate student nurses' understanding of sustainability in two countries: A mixed method study. Nurse Educ. Today 2020, 88, 104363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siemon, M.; Diekema, A.R.; Calabria, R.A. Cross sectional survey of attitudes on sustainability and climate change among baccalaureate nursing faculty and students. Nurse Educ. Today 2024, 140, 106268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, personality, and behavior; McGraw-Hill Education: United Kingdom, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Madden, T. Prediction of goal directed behaviour: Attitudes, intentions and perceived behavioural control. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 22, 453–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, J.P.; Felicilda-Reynaldo, R.F.D.; Alshammari, F.; Alquwez, N.; Alicante, J.G.; Obaid, K.B.; et al. Factors influencing Arab nursing students’ attitudes toward climate change and environmental sustainability and their inclusion in nursing curricula. Public Health Nurs. 2018, 35, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amerson, R.M.; Boice, O.; Mitchell, H.; Bible, J. Nursing faculty’s perceptions of climate change and sustainability. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2022, 43, 277–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.D.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Butterfield, P.; Leffers, J.; Vasquez, M.D. Nursing’s pivotal role in global climate action. Brit. Med. J. 2021, 373, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Nieto, C.; Parra-Anguita, L.; Álvarez-García, C.; Montoro Ramírez, E.M.; López-Franco, M.D.; Sanz-Martos, S.; López Medina, I.M. Sustainability education in nursing degree for climate-smart healthcare: A quasi-experimental study. Int J Sustain High Educ 2024, 25, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Medina, I.M.; Álvarez-García, C.; Parra-Anguita, L.; Sanz-Martos, S.; Álvarez-Nieto, C. Perceptions and concerns about sustainable healthcare of nursing students trained in sustainability and health: A cohort study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2022, 65, 10348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Nieto, C.; Álvarez-García, C.; Parra-Anguita, L.; Sanz-Martos, S.; López-Medina, I.M. Effectiveness of scenario-based learning and augmented reality for nursing students’ attitudes and awareness toward climate change and sustainability. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez-García, C.; Álvarez-Nieto, C.; Kelsey, J.; Carter, R.; Sanz-Martos, S.; López-Medina, I.M. Effectiveness of the e-Nursus children intervention in the training of nursing students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019, 16, 4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, J.P.; Felicilda-Reynaldo, R.F.D.; Alshammari, F.; Alquwez, N.; Alicante, J.G.; Obaid, K.B.; et al. Factors influencing Arab nursing students’ attitudes toward climate change and environmental sustainability and their inclusion in nursing curricula. Public Health Nurs. 2018, 35, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component | Eigenvalues | Parallel Horn analysis | ||

| Total | % variance | % cumulative | Simulation | |

| 1* | 3.14 | 56.10 % | 56.10 % | 1.16 |

| 2 | 0.94 | 1.07 | ||

| 3 | 0.41 | 0.99 | ||

| 4 | 0.35 | 0.93 | ||

| 5 | 0.16 | 0.85 | ||

| Component | Eigenvalues | Parallel Horn analysis | ||

| Total | % variance | Total | ||

| 1* | 4.06 | 12.90 % | 12.90 % | 1.56 |

| 2* | 2.23 | 5.80 % | 18.70 % | 1.46 |

| 3* | 1.53 | 2.90 % | 21.60 % | 1.41 |

| 4* | 1.38 | 2.20 % | 23.80 % | 1.35 |

| 5 | 1.27 | 1.29 | ||

| 6 | 1.19 | 1.26 | ||

| 7 | 1.12 | 1.21 | ||

| 8 | 1.06 | 1.18 | ||

| 9 | 0.97 | 1.14 | ||

| 10 | 0.95 | 1.11 | ||

| 11 | 0.93 | 1.07 | ||

| 12 | 0.87 | 1.03 | ||

| 13 | 0.82 | 0.99 | ||

| 14 | 0.78 | 0.96 | ||

| 15 | 0.77 | 0.93 | ||

| 16 | 0.68 | 0.90 | ||

| 17 | 0.66 | 0.86 | ||

| 18 | 0.65 | 0.83 | ||

| 19 | 0.61 | 0.80 | ||

| 20 | 0.58 | 0.77 | ||

| 21 | 0.56 | 0.73 | ||

| 22 | 0.51 | 0.70 | ||

| 23 | 0.50 | 0.67 | ||

| 24 | 0.46 | 0.64 | ||

| 25 | 0.44 | 0.61 | ||

| 26 | 0.42 | 0.56 | ||

| Item | Difficulty | Standard error | Infit: Weighted Mean Square Fit | Infit: Standardized Weighted Mean Square Fit | Outfit: Weighted Mean Square Fit | Outfit: Standardized Weighted Mean Square Fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -2.08 | 0.21 | 1.03 | 0.22 | 1.07 | 0.37 |

| 2 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 1.05 | 1.09 | 1.05 | 0.79 |

| 3 | -0.16 | 0.14 | 1.23 | 4.13 | 1.23 | 2.79 |

| 4 | -1.27 | 0.16 | 0.87 | -1.32 | 0.71 | -2.15 |

| 5 | 2.78 | 0.20 | 0.95 | -0.33 | 1.04 | 0.25 |

| 6 | -1.49 | 0.17 | 1.02 | 0.26 | 1.06 | 0.41 |

| 7 | -1.19 | 0.16 | 1.11 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 1.15 |

| 8 | 1.20 | 0.14 | 0.97 | -0.47 | 1.00 | 0.07 |

| 9 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.90 | -2.28 | 0.89 | -1.64 |

| 10 | -0.43 | 0.14 | 1.02 | 0.37 | 1.05 | 0.57 |

| 11 | 0.77 | 0.13 | 1.07 | 1.53 | 1.05 | 0.62 |

| 12 | -0.50 | 0.14 | 0.95 | -0.81 | 0.91 | -0.98 |

| 13 | -0.11 | 0.13 | 0.85 | -3.01 | 0.79 | -2.95 |

| 14 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.94 | -1.40 | 0.89 | -1.61 |

| 15 | -0.50 | 0.14 | 0.97 | -0.39 | 1.02 | 0.21 |

| 16 | -0.16 | 0.14 | 0.97 | -0.47 | 0.96 | -0.43 |

| 17 | -0.25 | 0.14 | 0.88 | -2.21 | 0.87 | -1.61 |

| 18 | 0.67 | 0.13 | 0.93 | -1.54 | 0.89 | -1.49 |

| 19 | 1.38 | 0.14 | 0.96 | -0.58 | 0.90 | -0.86 |

| 20 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.94 | -1.34 | 0.97 | -0.40 |

| 21 | 1.71 | 0.15 | 0.98 | -0.19 | 0.93 | -0.44 |

| 22 | 0.65 | 0.13 | 0.92 | -1.80 | 0.87 | -1.82 |

| 23 | -0.43 | 0.14 | 0.97 | -0.44 | 0.96 | -0.38 |

| 24 | -1.19 | 0.16 | 0.89 | -1.23 | 0.91 | -0.57 |

| 25 | -0.84 | 0.15 | 0.94 | -0.80 | 1.02 | 0.20 |

| 26 | 0.85 | 0.13 | 1.05 | 1.06 | 1.02 | 0.23 |

| Component | Eigenvalues | Parallel Horn analysis | ||

| Total | % variance | Total | ||

| 1* | 5.25 | 39.70 % | 39.70 % | 1.33 |

| 2* | 1.61 | 9.20 % | 48.90 % | 1.23 |

| 3 | 0.86 | 1.17 | ||

| 4 | 0.72 | 1.12 | ||

| 5 | 0.71 | 1.07 | ||

| 6 | 0.59 | 1.01 | ||

| 7 | 0.48 | 0.96 | ||

| 8 | 0.44 | 0.92 | ||

| 9 | 0.40 | 0.87 | ||

| 10 | 0.36 | 0.83 | ||

| 11 | 0.33 | 0.78 | ||

| 12 | 0.27 | 0.72 | ||

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | 0.81 | |

| 6 | 0.78 | |

| 11 | 0.74 | |

| 12 | 0.69 | |

| 2 | 0.63 | |

| 4 | 0.42 | |

| 7 | 0.75 | |

| 5 | 0.75 | |

| 9 | 0.70 | |

| 10 | 0.64 | |

| 3 | 0.63 | |

| 1 | 0.57 |

| Item | Difficulty | Standard error | Infit: Weighted Mean Square Fit | Infit: Standardized Weighted Mean Square Fit | Outfit: Weighted Mean Square Fit | Outfit: Standardized Weighted Mean Square Fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -0.32 | 0.10 | 1.04 | 0.42 | 0.98 | -0.19 |

| 2 | -0.41 | 0.11 | 1.47 | 4.39 | 1.44 | 3.96 |

| 3 | 0.35 | 0.10 | 1.22 | 2.35 | 1.23 | 2.28 |

| 4 | 0.28 | 0.10 | 0.99 | -0.12 | 1.05 | 0.55 |

| 5 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 0.95 | -0.50 | 0.92 | -0.80 |

| 6 | -0.00 | 0.10 | 0.91 | -1.00 | 0.88 | -1.31 |

| 7 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.82 | -2.03 | 0.82 | -1.97 |

| 8 | -0.24 | 0.10 | 1.01 | 0.12 | 1.01 | 0.18 |

| 9 | -0.07 | 0.10 | 0.77 | -2.68 | 0.73 | -3.06 |

| 10 | -0.12 | 0.10 | 0.89 | -1.25 | 0.87 | -1.37 |

| 11 | -0.01 | 0.10 | 0.76 | -2.76 | 0.74 | -2.93 |

| 12 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 1.16 | 1.67 | 1.27 | 2.66 |

| Likert category | Threshold | Standard deviation | Infit | Outfit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | ||||

| 1 | -3.05 | 0.17 | 1.11 | 1.30 |

| 2 | -1.40 | 0.07 | 0.71 | 0.67 |

| 3 | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.80 | 0.82 |

| 4 | 4.21 | 0.08 | 1.30 | 1.05 |

| n | Completely disagree | Disagree | Partially disagree | Neutral | Partially agree | Agree | Completely agree | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

307 | 0.32% (1) |

0.98% (3) |

1.30% (4) |

5.86% (18) |

14.98% (46) |

44.30% (136) |

32.24% (99) |

5.96 |

|

307 | 2.28% (7) |

5.86% (18) |

3.58% (11) |

16.29% (50) |

26.06% (80) |

30.29% (93) |

15.63% (48) |

5.11 |

|

307 | 0.33% (1) |

0.33% (1) |

1.63% (5) |

5.54% (17) |

18.57% (57) |

43.32% (133) |

30.29% (93) |

5.93 |

|

307 | 1.63% (5) |

3.91% (12) |

5.21% (16) |

13.36% (41) |

22.15% (68) |

34.53% (106) |

19.22% (59) |

5.31 |

|

307 | 0.33% (1) |

0% (0) |

0.98% (3) |

6.52% (20) |

21.50% (66) |

47.56% (146) |

23.13% (71) |

5.84 |

| Items | Hits | Ignorance Index |

|---|---|---|

|

248/275 (90.18%) | 12/275 (4.36%) |

|

147/275 (53.46%) | 77/275 (28.00%) |

|

170/275 (61.82%) | 63/275 (22.91%) |

|

224/275 (81.46%) | 34/275 (12.36%) |

|

26/275 (9.46%) | 78/275 (28.36%) |

|

232/275 (84.36%) | 31/275 (11.27%) |

|

221/275 (80.36%) | 20/275 (7.27%) |

|

88/275 (32.00%) | 140/275 (50.91%) |

|

147/275 (53.46%) | 116/275 (42.18%) |

|

185/275 (67.27%) | 36/275 (13.09%) |

|

113/275 (41.09%) | 129/275 (46.91%) |

|

189/275 (68.73%) | 74/275 (26.91%) |

|

167/275 (60.73%) | 79/275 (28.73%) |

|

154/275 (56.00%) | 100/275 (36.36%) |

|

189/275 (68.73%) | 39/275 (14.18%) |

|

170/275 (61.82%) | 75/275 (27.27%) |

|

175/275 (63.64%) | 54/275 (19.64%) |

|

119/275 (43.27%) | 120/275 (43.64%) |

|

78/275 (28.36%) | 70/275 (25.46%) |

|

158/275 (57.46%) | 98/275 (35.64%) |

|

62/275 (22.55%) | 97/275 (35.27%) |

|

120/275 (43.64%) | 121/275 (44.00%) |

|

185/275 (67.27%) | 46/275 (16.73%) |

|

221/275 (80.36%) | 32/275 (11.64%) |

|

206/275 (74.91%) | 44/275 (16.00%) |

|

108/275 (39.27%) | 51/275 (18.54%) |

| n | Completely disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Completely agree | Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

265 | 1.13% (3) |

4.15% (11) |

27.55% (73) |

59.62% (158) |

7.55% (20) |

3.68 |

|

265 | 1.51% (4) |

8.68% (23) |

21.13 % (56) |

53.96% (143) |

14.72% (39) |

3.72 |

|

265 | 1.51% (4) |

13.21% (35) |

35.47% (94) |

45.28% (120) |

4.53% (0) |

3.38 |

|

265 | 1.51% (4) |

14.34% (38) |

32.83% (87) |

43.77% (116) |

7.55% (20) |

3.42 |

|

265 | 1.89% (5) |

12.83% (34) |

33.96% (90) |

44.91% (119) |

6.42% (17) |

3.41 |

|

265 | 0.76% (2) |

11.70% (31) |

26.42% (70) |

54.34 % (144) |

6.79% (18) |

3.55 |

|

265 | 0.76% (2) |

8.68% (23) |

32.83% (87) |

52.45% (139) |

5.28% (14) |

3.53 |

|

265 | 1.13% (3) |

7.55% (20) |

24.53% (65) |

58.87% (156) |

7.93% (21) |

3.65 |

|

265 | 0.76% (2) |

8.31% (22) |

29.82% (79) |

54.72% (145) |

6.42% (17) |

3.58 |

|

265 | 0.76% (2) |

5.66% (15) |

30.94% (82) |

58.49% (155) |

4.15% (11) |

3.60 |

|

265 | 2.13% (3) |

8.68% (23) |

32.45% (86) |

49.43% (131) |

8.30% (22) |

3.55 |

|

265 | 2.26% (6) |

12.83% (34) |

34.34% (91) |

39.25% (104) |

11.32% (30) |

3.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).