Submitted:

21 November 2024

Posted:

22 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

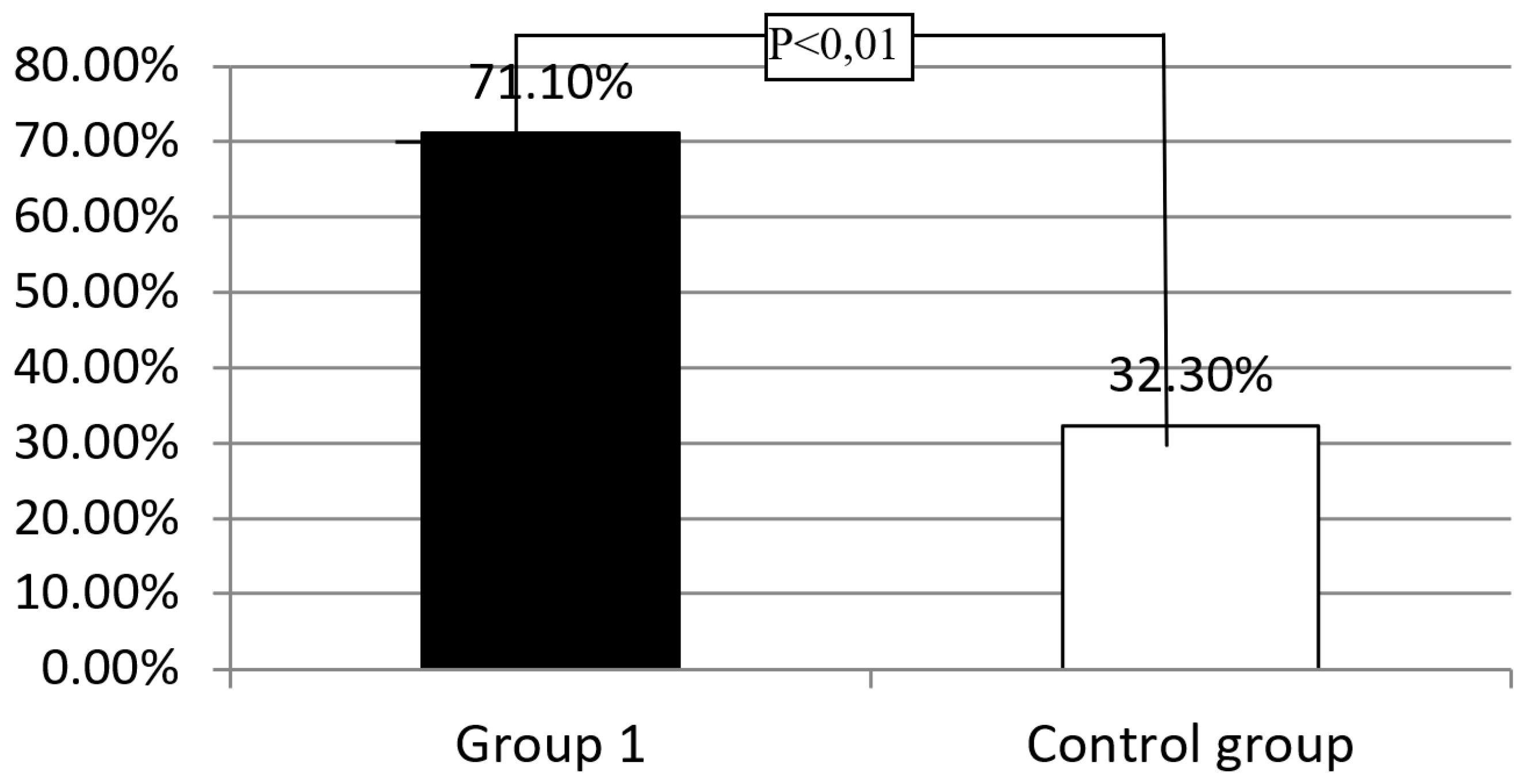

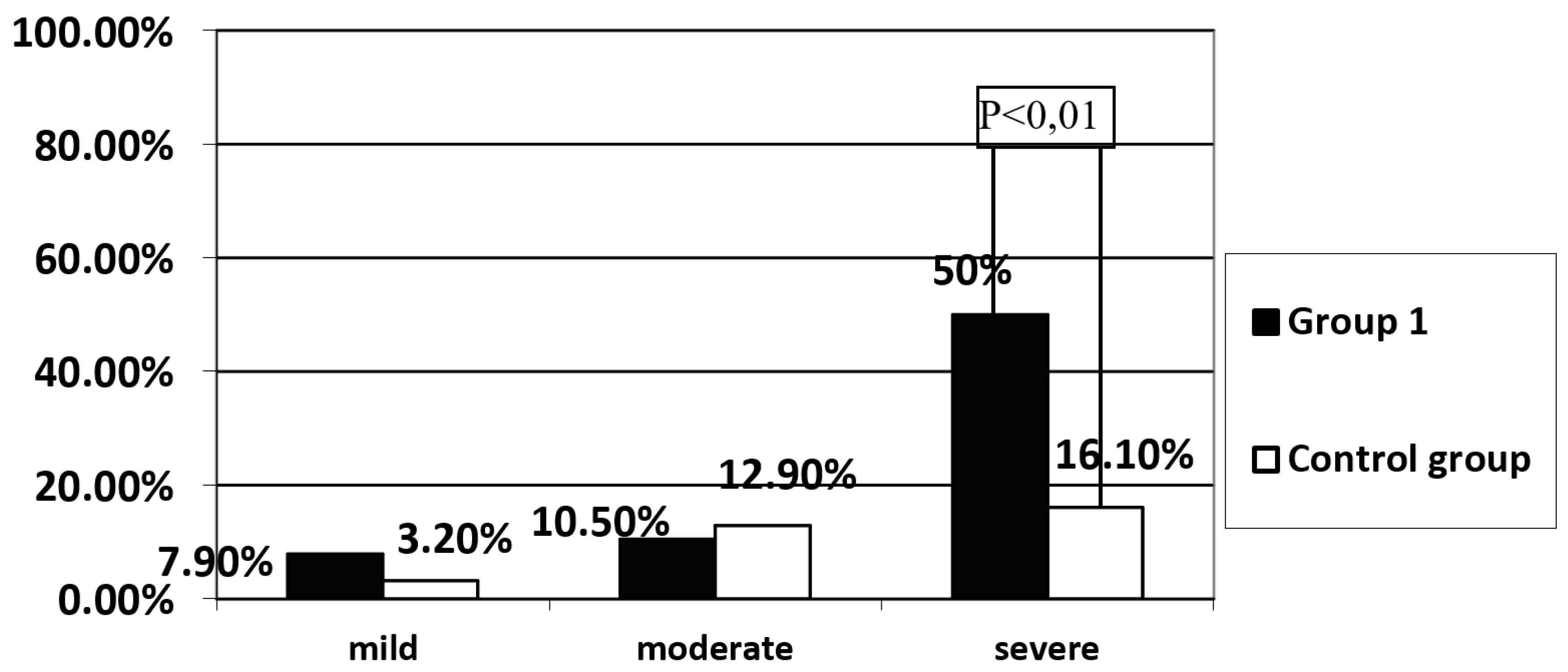

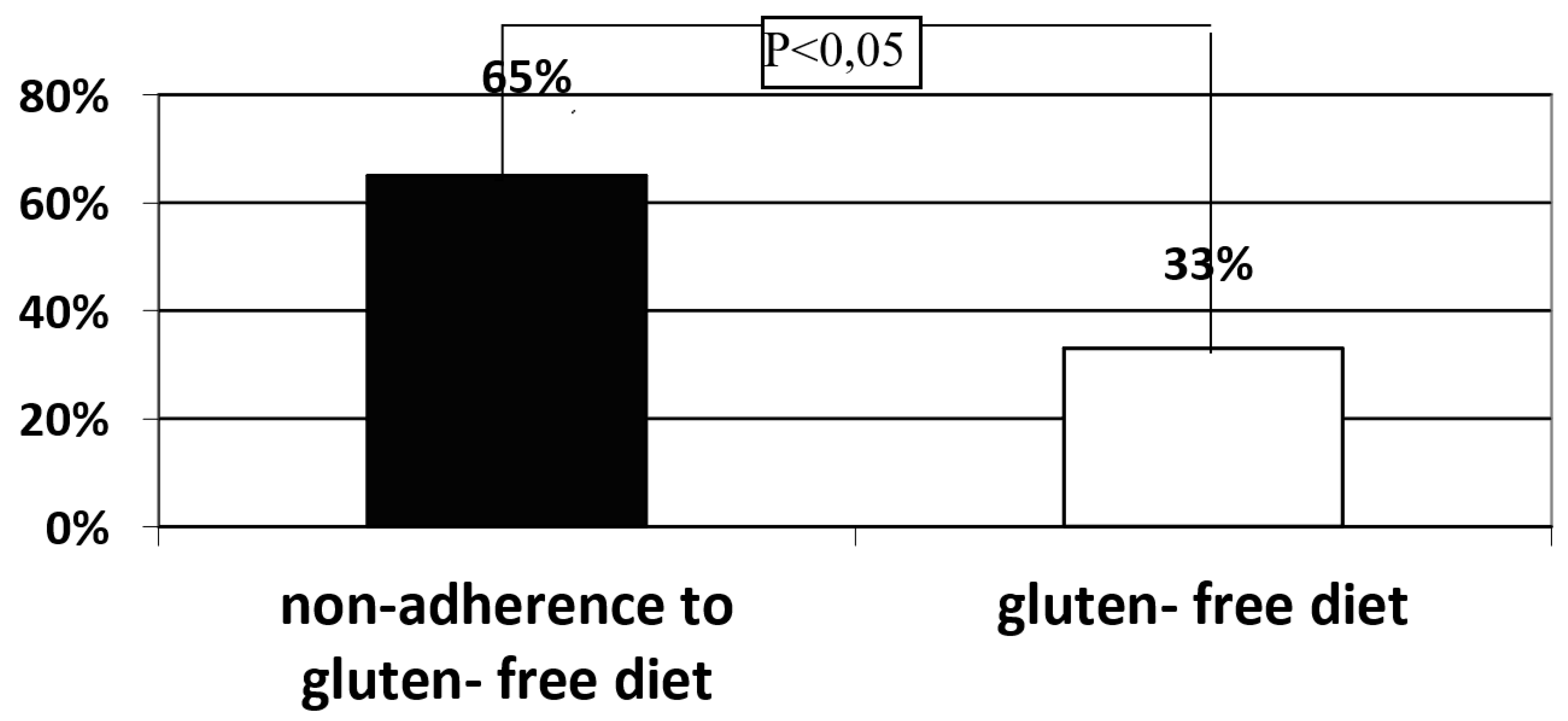

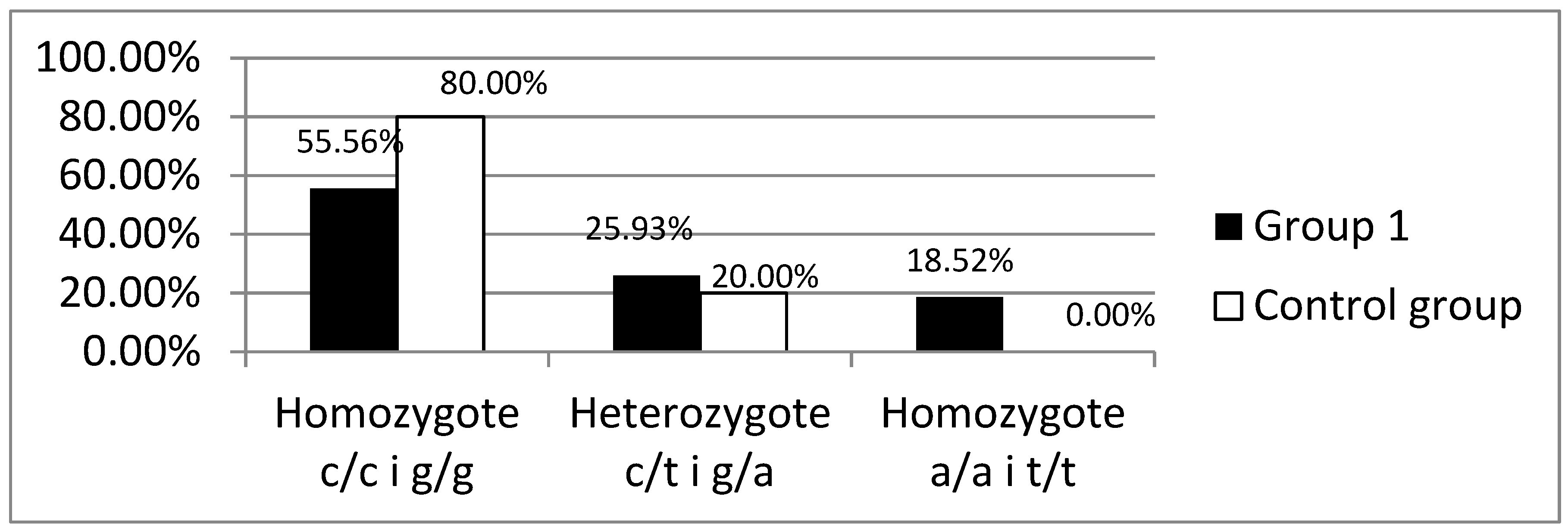

Background: Celiac disease (CD) is defined as a systemic autoimmune disorder induced by gluten and other prolamins, which leads to gradual histopathological damage of the duodenum mucosa, intestinal villous atrophy, in particular. The brush border of enterocytes produces disaccharidases, including lactase. Lactase deficiency may be primary - genetically determined or secondary- due to damage to the intestinal villi. To exclude the primary cause of lactase deficiency, LCT gene polymorphism is necessary to evaluate. Objective: In patients diagnosed with CD, the intestinal villi should recover after strict adherence to the gluten-free diet, and therefore no lactase enzyme deficiency secondary to the underlying disease should be observed. Methods: The study group consisted of 38 patients, 30 women and 8 men (Group 1), who presented symptoms suggesting CD at the time of diagnosis, histology of duodenal mucosa samples revealed Marsh grade 3 and had confirmed the presence of HLA-DQ2 or DQ8 genes and had the gluten-free diet recommended. The control group consisted of 31 healthy volunteers, 18 women and 13 men. A hydrogen breath test (HBT) was performed in all groups with 50 g of lactose dissolved in 250 ml of water. Among patients with a positive HBT in all groups, a blood sample was collected to determine the C/T (-13910) and G/A (-22018) polymorphism in the promoter of the LCT gene responsible for the synthesis of the lactase enzyme. Among patients with lactase deficiency confirmed in HBT, LCT gene analysis was performed by assessing the C/T (-13910) and G/A (-22018) polymorphisms.Results: A significantly higher incidence of lactase enzyme deficiency was found in Group 1 (n=27, 71.1%) compared to the control group (n=10, 32.3%) (p<0.01). Severe lactase deficiency was observed more frequently in the group 1 than in the control group (n=19 (50%) vs. n=5 (16.1%); p<0.01), while mild and moderate lactase enzyme deficiency was observed with similar prevalence. Severe deficiency of the lactase enzyme was found significantly more frequently in the group of patient who did not strictly follow the diet than in the group declaring a strict adherence to a gluten-free diet (n=13 (65%) vs. n=6 (33%); p<0.05). No significant difference was found in the frequency of the C/T (-13910) and G/A (-22018) polymorphism in the promoter of the LCT between the analyzed groups with previously positive HBT test. Only in group 1, in 5 (18.5%) patients presence of LCT gene variants responsible for lactase enzyme deficiency was not detected. Conclusions: Among patients with CD, lactase deficiency was confirmed in the majority of the study participants, of whom only about half had primary lactase deficiency. In the study group, a correlation was demonstrated between severe deficiency of the lactase enzyme and non-adherence to gluten- free diet.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Celiac Disease

Lactase Deficiency

2. Assumptions and Objectives

3. Aim

- Assessment of the prevalence of lactase deficiency and its severity among patients with celiac disease.

- Searching for the correlations between the lactase deficiency presence, non- adherence to gluten-free diet and high levels of the tissue transglutaminase 2 specific-antibodies.

4. Material and Methods

Study and Control Groups

Hydrogen Breath Test

Genetic Polymorphism in the LCT Gene

Statistical Analysis

5. Results

Assessment of the Prevalence of Lactase Enzyme Deficiency in the Study Group and the Control Group

C/T(-13910) and G/A(-22018) Polymorphisms in the Promoter of the LCT Gene

6. Discussion

7. Summary

8. Conclusions

- Among patients with celiac disease, lactase deficiency was confirmed in the majority of the study participants, of whom only 55% had primary lactase deficiency.

- In the study group, a correlation between severe lactase deficiency and non- adherence to the gluten- free diet was demonstrated.

Acknowledgments

References

- Husby, S.; Koletzko, S.; Korponay-Szabó, I.R.; Mearin, M.L.; Phillips, A.; Shamir, R.; Troncone, R.; Giersiepen, K.; Branski, D.; Catassi, C.; et al. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2012, 54, 136–160. [CrossRef]

- Husby, S.; Koletzko, S.; Korponay-Szabó, I.; Kurppa, K.; Mearin, M.L.; Ribes-Koninckx, C.; Shamir, R.; Troncone, R.; Auricchio, R.; Castillejo, G.; et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Guidelines for Diagnosing Coeliac Disease 2020. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 70, 141–156. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, M.N. Grains of truth: evolutionary changes in small intestinal mucosa in response to environmental antigen challenge.. Gut 1990, 31, 111–114. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, M.N., Studies of intestinal lymphoid tissue. III. Quantitative analyses of epithelial lymphocytes in the small intestine of human control subjects and of patients with celiac sprue. Gastroenterology, 1980. 79(3): p. 481-92.

- Oberhuber, G., G. Granditsch, and H. Vogelsang, The histopathology of coeliac disease: time for a standardized report scheme for pathologists. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 1999. 11(10): p. 1185-94.

- Oberhuber, G., et al., [Study Group of Gastroenterological Pathology of the German Society of Pathology. Recommendations for celiac disease/sprue diagnosis]. Z Gastroenterol, 2001. 39(2): p. 157-66.

- Oberhuber, G. Histopathology of celiac disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2000, 54, 368–372. [CrossRef]

- Kerber, M., et al., Hydrogen breath testing versus LCT genotyping for the diagnosis of lactose intolerance: a matter of age? Clin Chim Acta, 2007. 383(1-2): p. 91-6.

- Di Stefano, M., et al., Genetic test for lactase non-persistence and hydrogen breath test: is genotype better than phenotype to diagnose lactose malabsorption? Dig Liver Dis, 2009. 41(7): p. 474-9.

- Krawczyk, M.; Wolska, M.; Schwartz, S.; Gruenhage, F.; Terjung, B.; Portincasa, P.; Sauerbruch, T.; Lammert, F. Concordance of genetic and breath tests for lactose intolerance in a tertiary referral centre.. 2008, 17, 135–9.

- Högenauer, C.; Hammer, H.F.; Mellitzer, K.; Renner, W.; Krejs, G.J.; Toplak, H. Evaluation of a new DNA test compared with the lactose hydrogen breath test for the diagnosis of lactase non-persistence. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005, 17, 371–376. [CrossRef]

- Morales, E.; Azocar, L.; Maul, X.; Perez, C.; Chianale, J.; Miquel, J.F. The European lactase persistence genotype determines the lactase persistence state and correlates with gastrointestinal symptoms in the Hispanic and Amerindian Chilean population: a case–control and population-based study. BMJ Open 2011, 1, e000125. [CrossRef]

- Itan, Y.; Jones, B.L.; Ingram, C.J.; Swallow, D.M.; Thomas, M.G. A worldwide correlation of lactase persistence phenotype and genotypes. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010, 10, 36–36. [CrossRef]

- Bodlaj, G.; Stöcher, M.; Hufnagl, P.; Hubmann, R.; Biesenbach, G.; Stekel, H.; Berg, J. Genotyping of the Lactase-Phlorizin Hydrolase −13910 Polymorphism by LightCycler PCR and Implications for the Diagnosis of Lactose Intolerance. Clin. Chem. 2006, 52, 148–151. [CrossRef]

- Torres, E.M.; Prieto, L.L.V.; Camacho, J.L.V.; Torregroza, D.A.V. Diagnosis of adult-type hypolactasia/lactase persistence: genotyping of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP C/T-13910) is not consistent with breath test in Colombian Caribbean population. Arq. de Gastroenterol. 2012, 49, 5–8. [CrossRef]

- Raz, M.; Sharon, Y.; Yerushalmi, B.; Birk, R. Frequency of LCT-13910C/T and LCT-22018G/A single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with adult-type hypolactasia/lactase persistence among Israelis of different ethnic groups. Gene 2013, 519, 67–70. [CrossRef]

- Mądry, E.; Lisowska, A.; Kwiecień, J.; Marciniak, R.; Korzon-Burakowska, A.; Drzymała-Czyż, S.; Mojs, E.; Walkowiak, J. Adult-type hypolactasia and lactose malabsorption in Poland.. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2010, 57, 585–8. [CrossRef]

- Kuokkanen, M.; Butzow, R.; Rasinperä, H.; Medrek, K.; Nilbert, M.; Malander, S.; Lubinski, J.; Järvelä, I. Lactase persistence and ovarian carcinoma risk in Finland, Poland and Sweden. Int. J. Cancer 2005, 117, 90–94. [CrossRef]

- Wiecek, S.; Wos, H.; Radziewicz-Winnicki, I.; Komraus, M.; Grzybowska-Chlebowczyk, U. Disaccharidase activity in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 25, 185–191. [CrossRef]

- von Tirpitz, C., et al., Lactose intolerance in active Crohn's disease: clinical value of duodenal lactase analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2002. 34(1): p. 49-53.

- Pawłowska, K.; Umławska, W.; Iwańczak, B. Prevalence of Lactose Malabsorption and Lactose Intolerance in Pediatric Patients with Selected Gastrointestinal Diseases. Adv. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 24, 863–871. [CrossRef]

- Mądry, E.; Krasińska, B.; Drzymała-Czyż, S.; Sands, D.; Lisowska, A.; Grebowiec, P.; Minarowska, A.; Oralewska, B.; Mańkowski, P.; Moczko, J.; et al. Lactose malabsorption is a risk factor for decreased bone mineral density in pancreatic insufficient cystic fibrosis patients. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2012, 20, 1092–1095. [CrossRef]

- Mądry, E.; Fidler, E.; Sobczyńska-Tomaszewska, A.; Lisowska, A.; Krzyżanowska, P.; Pogorzelski, A.; Minarowski, .; Oralewska, B.; Mojs, E.; Sapiejka, E.; et al. Mild CFTR mutations and genetic predisposition to lactase persistence in cystic fibrosis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2011, 19, 748–752. [CrossRef]

- Marie, I.; Leroi, A.; Gourcerol, G.; Levesque, H.; Menard, J.; Ducrotte, P. Lactose malabsorption in systemic sclerosis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 44, 1123–1133. [CrossRef]

- Daileda, T.; Baek, P.; E Sutter, M.; Thakkar, K. Disaccharidase activity in children undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy: A systematic review. World J. Gastrointest. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 7, 283–293. [CrossRef]

- Hove, H.; Nørgaard, H.; Mortensen, P.B. Lactic acid bacteria and the human gastrointestinal tract. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 53, 339–350. [CrossRef]

- Usai-Satta, P., et al., Hydrogen Breath Tests: Are They Really Useful in the Nutritional Management of Digestive Disease? Nutrients, 2021. 13(3).

- Romagnuolo, J., D. Schiller, and R.J. Bailey, Using breath tests wisely in a gastroenterology practice: an evidence-based review of indications and pitfalls in interpretation. Am J Gastroenterol, 2002. 97(5): p. 1113-26.

- Portincasa, P.; Di Ciaula, A.; Vacca, M.; Montelli, R.; Wang, D.Q.; Palasciano, G. Beneficial effects of oral tilactase on patients with hypolactasia. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 38, 835–844. [CrossRef]

- Montalto, M., et al., Effect of exogenous beta-galactosidase in patients with lactose malabsorption and intolerance: a crossover double-blind placebo-controlled study, in Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005: England. p. 489-93.

- Ibba, I.; Gilli, A.; Boi, M.F.; Usai, P. Effects of Exogenous Lactase Administration on Hydrogen Breath Excretion and Intestinal Symptoms in Patients Presenting Lactose Malabsorption and Intolerance. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Ojetti, V.; Gigante, G.; Gabrielli, M.; E Ainora, M.; Mannocci, A.; Lauritano, E.C.; Gasbarrini, G.; Gasbarrini, A. The effect of oral supplementation with Lactobacillus reuteri or tilactase in lactose intolerant patients: randomized trial. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2010, 14, 163–70.

- Leis, R.; de Castro, M.-J.; de Lamas, C.; Picáns, R.; Couce, M.L. Effects of Prebiotic and Probiotic Supplementation on Lactase Deficiency and Lactose Intolerance: A Systematic Review of Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1487. [CrossRef]

- Eisenmann, A.; Amann, A.; Said, M.; Datta, B.; Ledochowski, M. Implementation and interpretation of hydrogen breath tests. J. Breath Res. 2008, 2, 046002–046002. [CrossRef]

- Gasbarrini, A.; Corazza, G.R.; Gasbarrini, G.B.; Montalto, M.; di Stefano, M.; Basilisco, G.; Parodi, A.; Usai-Satta, P.; Satta, P.U.; Vernia, P.; et al. Methodology and Indications of H2-Breath Testing in Gastrointestinal Diseases: The Rome Consensus Conference. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2009, 29 (Suppl. 1), 1–49. [CrossRef]

- Vernia, P., et al., Effect of predominant methanogenic flora on the outcome of lactose breath test in irritable bowel syndrome patients, in Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003: England. p. 1116-9.

- David John Walton, X.J., Craig Edward Banks, US 20120186999 A1. 2012, QuinTron Instrument CO.: Milwaukee.

- Tursi, A., G. Brandimarte, and G. Giorgetti, High prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in celiac patients with persistence of gastrointestinal symptoms after gluten withdrawal. Am J Gastroenterol, 2003. 98(4): p. 839-43.

- Ojetti, V.; Gabrielli, M.; Migneco, A.; Lauritano, C.; Zocco, M.A.; Scarpellini, E.; Nista, E.C.; Gasbarrini, G.; Gasbarrini, A. Regression of lactose malabsorption in coeliac patients after receiving a gluten-free diet. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 43, 174–177. [CrossRef]

- Mercer, J.; E Eagles, M.; Talbot, I.C. Brush border enzymes in coeliac disease: histochemical evaluation.. J. Clin. Pathol. 1990, 43, 307–312. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, U., et al., Lactase enzyme, detected immunohistochemically, is lost in active celiac disease, but unaffected by oats challenge. Am J Gastroenterol, 1999. 94(10): p. 2936-41.

- Lojda, Z. and J. Smídová, [Histochemistry of peptidases in jejunal biopsies of patients with malabsorption syndrome (author's transl)]. Sb Lek, 1981. 83(6-7): p. 153-61.

- Lojda, Z. Proteinases in pathology. Usefulness of histochemical methods. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1981, 29, 481–493. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.S., M. Sood, and T. Johnson, Use of the lactose H2 breath test to monitor mucosal healing in coeliac disease. Acta Paediatr, 2002. 91(2): p. 141-4.

- O'Grady, J.G.; Stevens, F.M.; Keane, R.; Cryan, E.M.; Egan-Mitchell, B.; McNicholl, B.; McCarthy, C.F.; Fottrell, P.F. Intestinal lactase, sucrase, and alkaline phosphatase in 373 patients with coeliac disease.. J. Clin. Pathol. 1984, 37, 298–301. [CrossRef]

- Mones, R.L.; Yankah, A.; Duelfer, D.; Bustami, R.; Mercer, G. Disaccharidase deficiency in pediatric patients with celiac disease and intact villi. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 46, 1429–1434. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K.K.; Thapa, B.R.; Nain, C.K.; Sharma, A.K.; Singh, K. Brush border enzyme activities in relation to histological lesion in pediatric celiac disease. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 23, e348–e352. [CrossRef]

- Nieminen, U., et al., Duodenal disaccharidase activities in the follow-up of villous atrophy in coeliac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol, 2001. 36(5): p. 507-10.

- Ojetti, V.; Nucera, G.; Migneco, A.; Gabrielli, M.; Lauritano, C.; Danese, S.; Zocco, M.A.; Nista, E.C.; Cammarota, G.; de Lorenzo, A.; et al. High Prevalence of Celiac Disease in Patients with Lactose Intolerance. Digestion 2005, 71, 106–110. [CrossRef]

- Kuchay, R.A.H.; Thapa, B.R.; Mahmood, A.; Anwar, M.; Mahmood, S. Lactase genetic polymorphisms and coeliac disease in children: a cohort study. Ann. Hum. Biol. 2014, 42, 101–104. [CrossRef]

- Basso, M.S.; Luciano, R.; Ferretti, F.; Muraca, M.; Panetta, F.; Bracci, F.; Ottino, S.; Diamanti, A. Association between celiac disease and primary lactase deficiency. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 66, 1364–1365. [CrossRef]

- Usai-Satta, P., et al., Lactose malabsorption and intolerance: What should be the best clinical management? World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther, 2012. 3(3): p. 29-33.

- Wilt, T.J., et al., Lactose intolerance and health. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep), 2010(192): p. 1-410.

- Usai-Satta, P.; Lai, M.; Oppia, F. Lactose Malabsorption and Presumed Related Disorders: A Review of Current Evidence. Nutrients 2022, 14, 584. [CrossRef]

- Leffler, D.A.; Dennis, M.; Hyett, B.; Kelly, E.; Schuppan, D.; Kelly, C.P. Etiologies and Predictors of Diagnosis in Nonresponsive Celiac Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007, 5, 445–450. [CrossRef]

- Penny, H.A.; Baggus, E.M.R.; Rej, A.; Snowden, J.A.; Sanders, D.S. Non-Responsive Coeliac Disease: A Comprehensive Review from the NHS England National Centre for Refractory Coeliac Disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 216. [CrossRef]

- Jankowiak, C. and D. Ludwig, [Frequent causes of diarrhea: celiac disease and lactose intolerance]. Med Klin (Munich), 2008. 103(6): p. 413-22; quiz 423-4.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).