2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of UO22+-Diglycolamide Complex

Yellow prismatic crystals of the desired UO22+-TiPDGA complex, [UO2(TiPDGA)(DMF)2](ClO4)2⋅CH2Cl2, were successfully obtained in 80% yield after the reaction between [UO2(DMF)5](ClO4)2 and TiPDGA from a 1:1 stoichiometric mixture of CH2Cl2 solution and recrystallization by slow diffusion of Et2O vapor to the mother liquor. This compound was thoroughly characterized by 1H NMR, IR, elemental analysis, and X-ray crystallography as summarized in Experimental section.

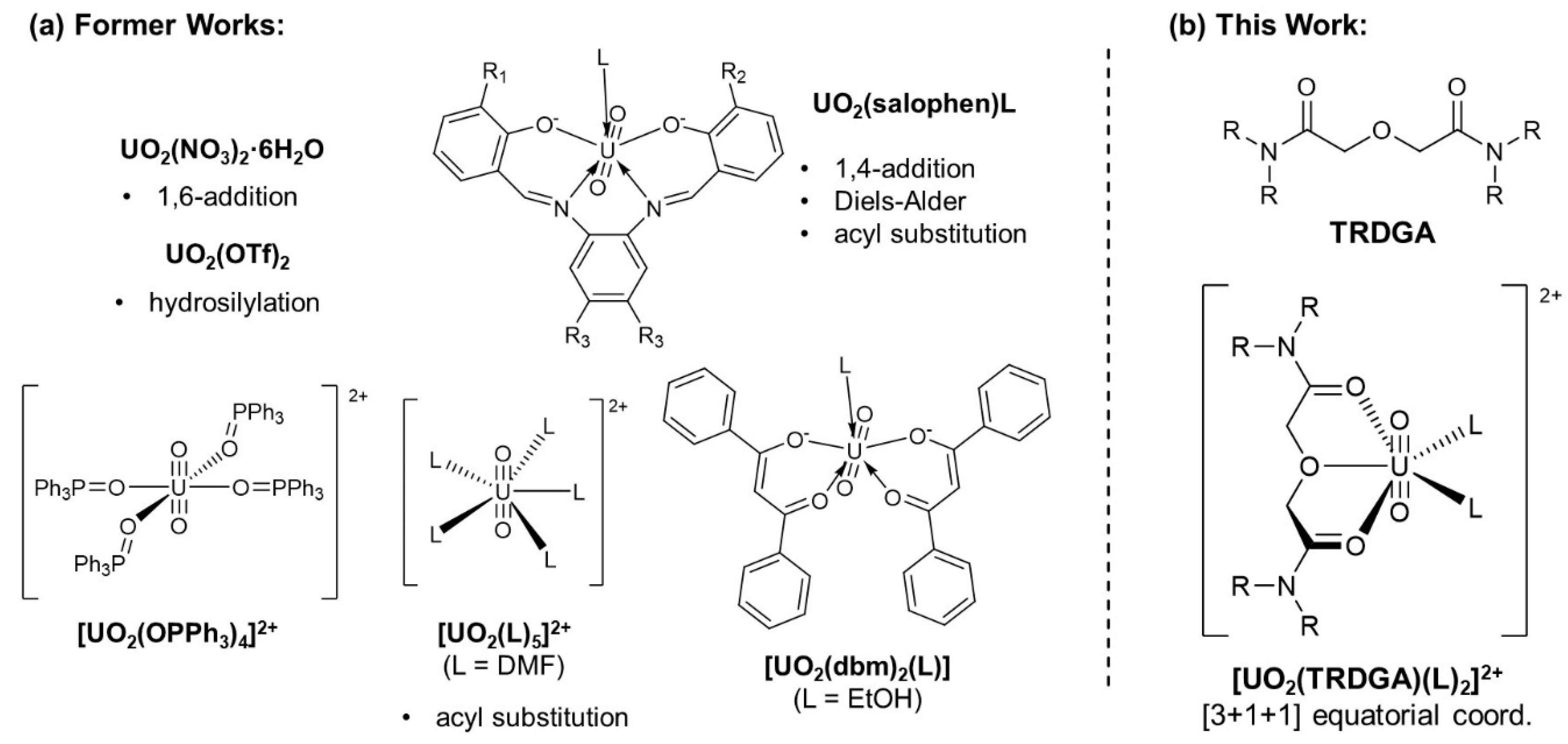

The molecular structure of [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ is illustrated in

Figure 2. A typical

trans-dioxo structure of UO

22+ was maintained in this complex, where the mean U≡O bond distance and the O≡U≡O angle are 1.75 Å and 179.46(19)°, respectively. This axial UO

22+ is further surrounded by additional ligands such as TiPDGA and DMF molecules in its equatorial plane to form pentagonal bipyramidal coordination geometry around the U centre. All O atoms of TiPDGA are bound to U in a tridentate manner to form two 5-membered chelate rings, which may play critical roles to stabilize this complex even under presence of excess DMF molecules arising from [UO

2(DMF)

5]

2+ [

17], a source of UO

22+ used in this work.

The interatomic distances from the U centre to O atoms of the amide (O

amide) and ether moieties (O

ether) of TiPDGA are 2.35 Å (mean) and 2.520(3) Å, respectively, implying stronger coordination of O

amide to U compared with that of O

ether in accordance with the stronger Lewis basicity of the former compared with the latter [

31]. Both U−O distances between UO

22+ and TiPDGA displayed in

Figure 2 are significantly shorter than those found in UO

2(TiPDGA)(NO

3)

2 reported by Kannan

et al. [

26] (U−O

amide = 2.40 Å (mean) and U−O

ether = 2.592(3) Å). In this another UO

22+-TiPDGA complex, two NO

3− are involved in the equatorial coordination around UO

22+. Due to the steric demands occurring in the equatorial plane of UO

2(TiPDGA)(NO

3)

2, these NO

3− exhibit different denticities; one is bidentate, while the other is monodentate, implying that there is no space wide enough to allow the bidentate coordination of both NO

3−. The same trend in U−O bond distances was also found between our [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ of

Figure 2 and [UO

2(TRDGA)

2]

2+ (R = Me) [

29,

30] showing U−O

amide = 2.42 Å (mean) and U−O

ether = 2.63 Å (mean). The equatorial plane of the latter complex was somewhat expanded despite the less-bulkier methyl substituents on the amide N atoms to maintain the planar hexa-coordination around UO

22+. In contrast, any steric constraints observed in the former related systems do not occur in the current [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+. This is because only one TiPDGA ligand is included in the coordination sphere, and also both DMF molecules are bound to U in monodentate manner (see below). This should be the reason why the shorter bond distances of U−O

amide and U−O

ether most probably associated with the stronger coordination of TiPDGA has been successfully attained by employing the non-coordinating ClO

4− as counteranions and stoichiometric loading of TiPDGA to UO

22+ in the reaction mixture.

As displayed in

Figure 2, the remaining coordination sites were occupied by two DMF molecules to saturate the equatorial plane of UO

22+, where the coordination of DMF molecules to U are as strong as those of O

amide of TiPDGA as pronounced by the similar bond distances (U(1)−O(6): 2.325(4) Å, U(1)−O(7): 2.343(4) Å), which are shorter than those in [UO

2(DMF)

5]

2+ (2.39 Å (mean) in ClO

4− salt, 2.37 Å (mean) in BF

4− salt) [

17,

32] and UO

2(salophen)DMF (2.410(3) Å) [

33]. This implies that the equatorial coordination sphere of [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ is sterically less-constrained. Indeed, sum of equatorial bond angles around the U centre (Σ

eq) is 360.28° to maintain nearly ideal planarity of the typical pentagonal equatorial coordination around UO

22+. Additionally, one CH

2Cl

2 molecule and two ClO

4− are included in this crystal structure (

Figure S1) as a crystalline solvent and non-coordinating counteranions of the positively charged [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+, respectively. Some of these isolated components were disordered even at 183 K.

In the above synthetic procedure, we have added 0.1 vol% of conc. HClO

4(aq) (10 μL) to the CH

2Cl

2-based mother liquor (10 mL) to successfully obtain [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2](ClO

4)

2⋅CH

2Cl

2 of

Figure 2. When this operation was skipped, another crystalline phase, [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)(H

2O)](ClO

4)

2⋅H

2O (

Figure S2) was obtained. Although hydrolysis of UO

22+ to give OH

− was once considered, all isolated O atoms (O(7), O(16)) were assigned to H

2O molecules because of electro-neutrality in its crystal lattice. The bond distances between U and O atoms at the apical positions were 1.76 Å (mean). The tridentate coordination of TiPDGA through amide and ether O atoms and their bond lengths (U−O

amide: 2.33 Å (mean), U−O

ether: 2.526(2) Å) almost remain unchanged from those of [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ shown in

Figure 2. The coordination of DMF seems to be stronger than that of H

2O in terms of bond lengths (U−O

DMF: 2.333(3) Å

vs. U−O

H2O: 2.379(3) Å). Additionally, a yellow chunk material also deposited together with the crystalline [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)(H

2O)](ClO

4)

2⋅H

2O. Although identity of this compound has not been determined yet due to its insolubility to any organic solvents, it would be of a hydrolytic product of UO

22+. This undesired reaction can be suppressed under an acidic condition, so that presence of the extra HClO

4 plays a crucial role to successfully provide [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ as a predominant product. For simplicity of the reaction system, we have hereafter employed the DMF solvate, [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2](ClO

4)

2⋅CH

2Cl

2 of

Figure 2, to explore its catalytic activity in the nucleophilic acyl substitution of acid anhydrides, the main topic of this work.

The molecular structure of [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ present in a CD

2Cl

2 solution was also studied by

1H NMR spectroscopy. The NMR signals arising from TiPDGA and DMF of this sample solution (see Experimental,

Figure S3) exhibited remarkable downfield shifts compared with those of their free forms (free DMF: 7.96 (s, 2H, C

HO), 2.91 (s, 3H, N(C

H3)

2), 2.82 (s, 3H, N(C

H3)

2); free TiPDGA: 4.22 (s, 4H OC

H2), 3.92 (septet, 2H, C

H(CH

3)

2), 3.45 (septet, 2H, C

H(CH

3)

2), 1.41 (d, 12H, CH(C

H3)

2), 1.18 (d, 12H, CH(C

H3)

2)). Therefore, both TiPDGA and DMF remain coordinated to UO

22+ even in the CD

2Cl

2 solution to maintain the original structure of [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ displayed in

Figure 2.

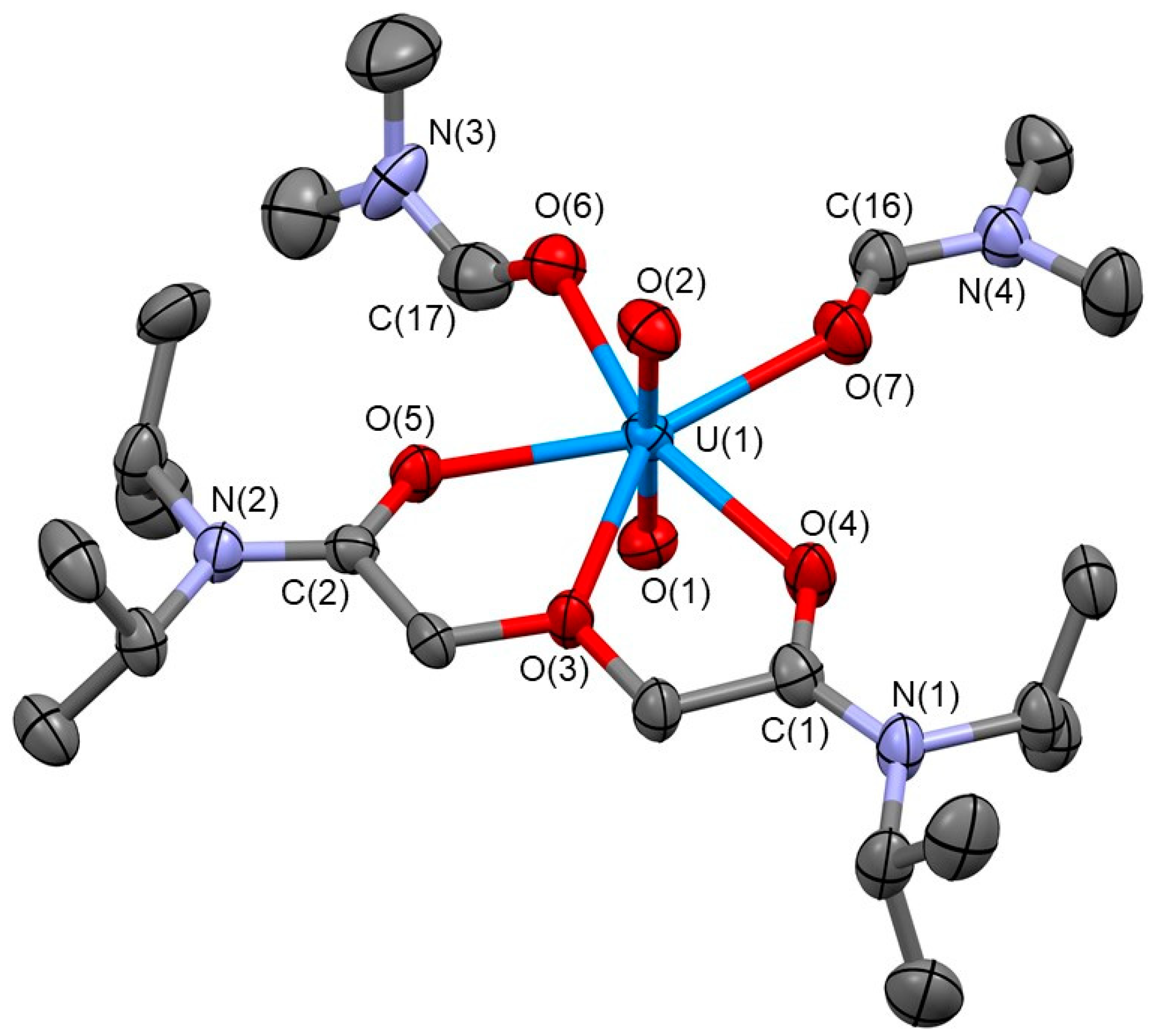

2.2. Nucleophilic Acyl Substitution Reactions Catalysed by [UO2(TiPDGA)(DMF)2]2+

In accordance with our former work [

22], we have first examined the catalytic activity of [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ in the reaction between acetic anhydride (Ac

2O) and 2-phenylethanol (PhetOH) to afford 2-phenylethyl acetate (PhetOAc) as shown in the reaction scheme of

Figure 3. Concentrations of the reactants and product at different time were determined by

1H NMR spectroscopy.

Figure 3(a) illustrates typical progress of the reaction. Both reactants were congruently consumed. Along with this, production of PhetOAc was observed, and reached 90% yield at 10 h (entry 1,

Table 1). Although even under absence of [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ the same product was generated, its yield was only 9% at 10 h (entry 2,

Table 1). Consequently, we have confirmed that this nucleophilic acyl substitution reaction was certainly catalysed by [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+. The reaction rate of the current system is actually slower than those reported in the former time, where the same reaction completed within 1 h to reach > 95% yield [

22]. Such a difference in the kinetic aspect would be ascribed to the equatorial plane sterically regulated by TiPDGA, the auxiliary tridentate ligand employed in this work. Based on the loading ratio of [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ (10 mM) with the substrates (0.5 M each) and the product yield (90% at 10 h) in entry 1 of

Table 1, the turnover number (TON) of the current catalytic system was 45.

We have further surveyed capabilities of [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ as a Lewis-acid catalyst in the current reaction system in use of different nucleophiles and different acid anhydrides. First, several aliphatic alcohols and phenol were tested as nucleophiles to be reacted with Ac

2O (entry 3-6,

Table 1). As a result, the corresponding acetate esters were generally afforded in high yields (88−100%) comparable with that of PhetOAc of entry 1 (90%), implying that a nucleophile would not largely affect the reaction mechanism.

An exception was found in use of

tBuOH (entry 7,

Table 1). While

tBuOAc was obtained in 78% yield at 10 h as expected, isobutylene ((CH

3)

2C=CH

2) was also generated as another product after the E1 elimination of

tBuOH. Note that both of

tBuOAc yield and its production rate in the current system are higher and faster than those observed in our former system catalysed by [UO

2(OPPh

3)

4]

2+ (

Figure 1, 63% yield at 72 h) [

22]. Furthermore, yield of isobutylene in the current system was less than 3%, which is much different from 32% yield in use of the [UO

2(OPPh

3)

4]

2+ catalyst [

22]. Because H

2O generated as a by-product of the E1 elimination of

tBuOH readily consumes Ac

2O, suppression of this side reaction is highly preferred. The steric control of the UO

22+ equatorial plane with TiPDGA drawn in

Figure 1 would also be favourable to prevent extra activation of bulky

tBuOH for the E1 path probably through its

O-coordination to the U centre of the catalyst.

In contrast to the nucleophiles, selection of acid anhydrides ((RCO)

2O) has significant impact to efficiency of the current catalytic acyl substitution. As shown in entry 1 and 8-11 of

Table 1, yields of the 2-phenylethyl esters of different acids remarkably decreased with an increase in length or bulkiness of R in the parent acid anhydrides. Most typically, pivalic (R =

tBu) and benzoic (R = Ph) anhydrides resulted in their corresponding esters only in 10% and 6% yields, respectively. Especially for the latter case, it is hard to know whether the reaction is catalysed by the UO

22+ complex or not. Even when MeOH was used as a sterically least-hindered nucleophile (entry 12,

Table 1), yield of its pivaloyl ester (14%) was only slightly higher than that of the 2-phenylethyl analogue (10%, entry 10). A series of these trends implies that the acid anhydride must be activated by the [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ catalyst to initiate the reaction, and that such an initial process is significantly controlled by steric effects. Details of the mechanistic aspects will be explored in the next section.

2.3. Reaction Kinetics and Catalysis Mechanism

From the data in

Table 1, we have already gained some qualitative insights about mechanistic aspects of the current reaction system. As mentioned above, an acid anhydride decides yield of its product, while a nucleophile has only small impact to the reaction efficiency. Herein, more detailed and quantitative assessment of its reaction kinetics and catalysis mechanism has been done by taking the acetylation of PhetOH with Ac

2O as a model reaction. Results are displayed in

Figure 3(b)-(d).

When the nucleophile concentration, [PhetOH], was varied from 100 mM to 480 mM (

Figure 3(b)), little differences in the reaction progress were observed unless PhetOH was consumed significantly. Indeed, the initial rate (

d[PhetOAc]/

dt =

kini) of this series were ranging from 22.7 μM⋅s

−1 to 27.5 μM⋅s

−1 despite 4.8-fold variation of [PhetOH]. This indicates that the nucleophile is not involved in the rate-determining step of this catalytic reaction.

We have also examined dependency of the reaction kinetics on the concentration of the other reactant, [Ac

2O]. As a result, the reaction kinetics became faster and faster with an increase in [Ac

2O] (

Figure 3(c)). Indeed,

kini in this series linearly increased with an increase in [Ac

2O]. Consequently, the rate of this catalytic reaction is first-order of [Ac

2O] with a slope equal to 4.0 × 10

−5 s

−1 (right panel of

Figure 3(c)), implying that one Ac

2O molecule is involved in the rate-determining step of this reaction, most probably activation of Ac

2O by the UO

22+ catalyst.

Activation of Ac

2O in this system would be attained through its coordination to the U centre of [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+. However, there would be no vacancies large enough to accept additional coordination in the equatorial plane of this UO

22+ complex as displayed in Figures 2 and S4 Therefore, some of the coordinating DMF molecules should be replaced with Ac

2O. If this assumption is correct, the reaction kinetics of the current catalytic system should be controlled by the concentration of DMF additionally loaded to the reaction system ([DMF]

add). As a matter of fact, the reaction rate significantly decreased with an increase in [DMF]

add (

Figure 3(d)). Therefore, the above hypothesis was found to be correct.

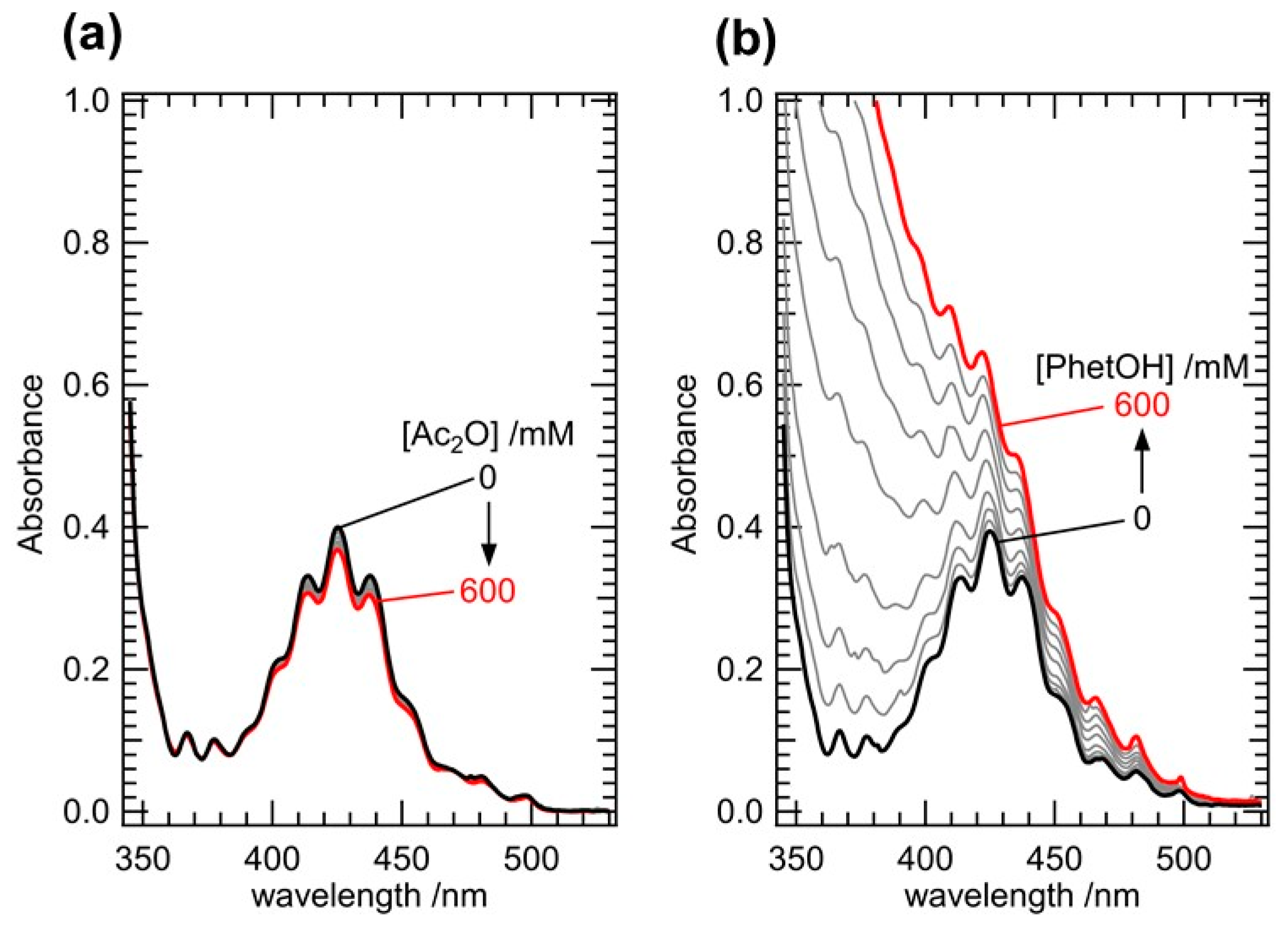

To precisely assess the dependency of

kini on [DMF] in this series, it is further necessary to know its net concentration in the sample solution, because the DMF molecules may be released from [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ to give extra free DMF in the reaction system. To resolve this problem, the UV-vis absorption spectra of a CH

2Cl

2 solution dissolving [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ were first recorded at different [Ac

2O], where PhetOH was absent. As a result, little variation was observed as shown in

Figure 4(a). It was confirmed that substitution of DMF with Ac

2O does not proceed predominantly. Note that the result observed in this UV-vis titration experiment just describes thermodynamic stability of the preferred coordination of DMF to the U centre superior to that of Ac

2O, and that it never rules out any possibility of the ligand substitution from DMF to Ac

2O to form a reaction intermediate in the catalytic process of

Figure 3.

We also collected UV-vis absorption spectra of the CH

2Cl

2 solution dissolving [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2](ClO

4)

2⋅CH

2Cl

2 (10 mM) at different [PhetOH], where Ac

2O was absent. In contrast to the little dependency on [Ac

2O] of

Figure 4(a), significant spectral variation was observed with an increase in [PhetOH] as shown in

Figure 4(b). Due to absence of any remarkable absorption of PhetOH at λ > 340 nm (

Figure S5), substitution of the coordinated DMF by PhetOH has been confirmed. We have analyzed this spectral series with the HypSpec software [

34] to assess the thermodynamic stabilities of the occurring species. Prior to this, the factor analysis [

35] for the data set of

Figure 4(b) revealed that this spectral variation consists of two principal components having meaningful eigenvalues (

Figure S6), suggesting that two UO

22+ complexes including the parent [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ are present in the titration series observed in

Figure 4(b). Consequently, the following ligand substitution equilibrium (Eq. (1)) with a logarithmic stability constant (log

βsub) should be considered.

Although the second substitution of the remaining DMF molecule would also be possible, its contribution in

Figure 4(b) should be negligibly small based on the above factor analysis of

Figure S6. Eq. (1) is further divided into the following equilibria, Eqs. (2) and (3), to describe formation of [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ and [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)(PhetOH)]

2+, respectively.

Herein, the desolvated UO22+ complex, [UO2(TiPDGA)]2+, is not an actual species occurring in the reaction system, but needs to be taken into account for expediency of the analysis.

As demonstrated by the

1H NMR spectroscopy (

Figure S3), we have already confirmed that [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ is present as a predominant species in the CD

2Cl

2 solution, indicating stability of this complex is high enough. Based on this fact, we derived log

β11 of Eq. (3) from the spectral variation of

Figure 4(b), where log

β20 of Eq. (2) was fixed to an arbitrary value (

e.g., log

β20 = 10, 15, 20) large enough to guarantee the predominance of [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ in the sample solution under absence of PhetOH. Consequently, the estimated log

β11 was always smaller by 0.28 than log

β20 with regardless of any above assumptions of log

β20,

i.e., log

βsub of Eq. (1) is equal to −0.28. Such a preferential solvation of DMF compared with PhetOH should be ascribed to difference in the Lewis basicity between them pronounced by the donor numbers (

DN) of DMF (26.6) and alcohols (~20) [

31].

The calculated speciation diagram of [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ and [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)(PhetOH)]

2+ at different [PhetOH] (

Figure S7) suggests that a mole fraction of [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)(PhetOH)]

2+ is 0.85 at [PhetOH] = 0.1 M for instance. At the same time, one of DMF molecules initially present in [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ is released in the same extent to give an extra concentration of DMF ([DMF]

sub). Accordingly, the total concentration of free DMF ([DMF]

total) in each sample solution of

Figure 3(d) is sum of [DMF]

add and [DMF]

sub. When

kini at different [DMF]

add was plotted against [DMF]

total−1, the linear relationship between these parameters was yielded (right panel of

Figure 3(d)). Finally,

kini is found to be first-order of [DMF]

total−1 with a slope equal to 7.8 × 10

−1 μM

2⋅s

−1.

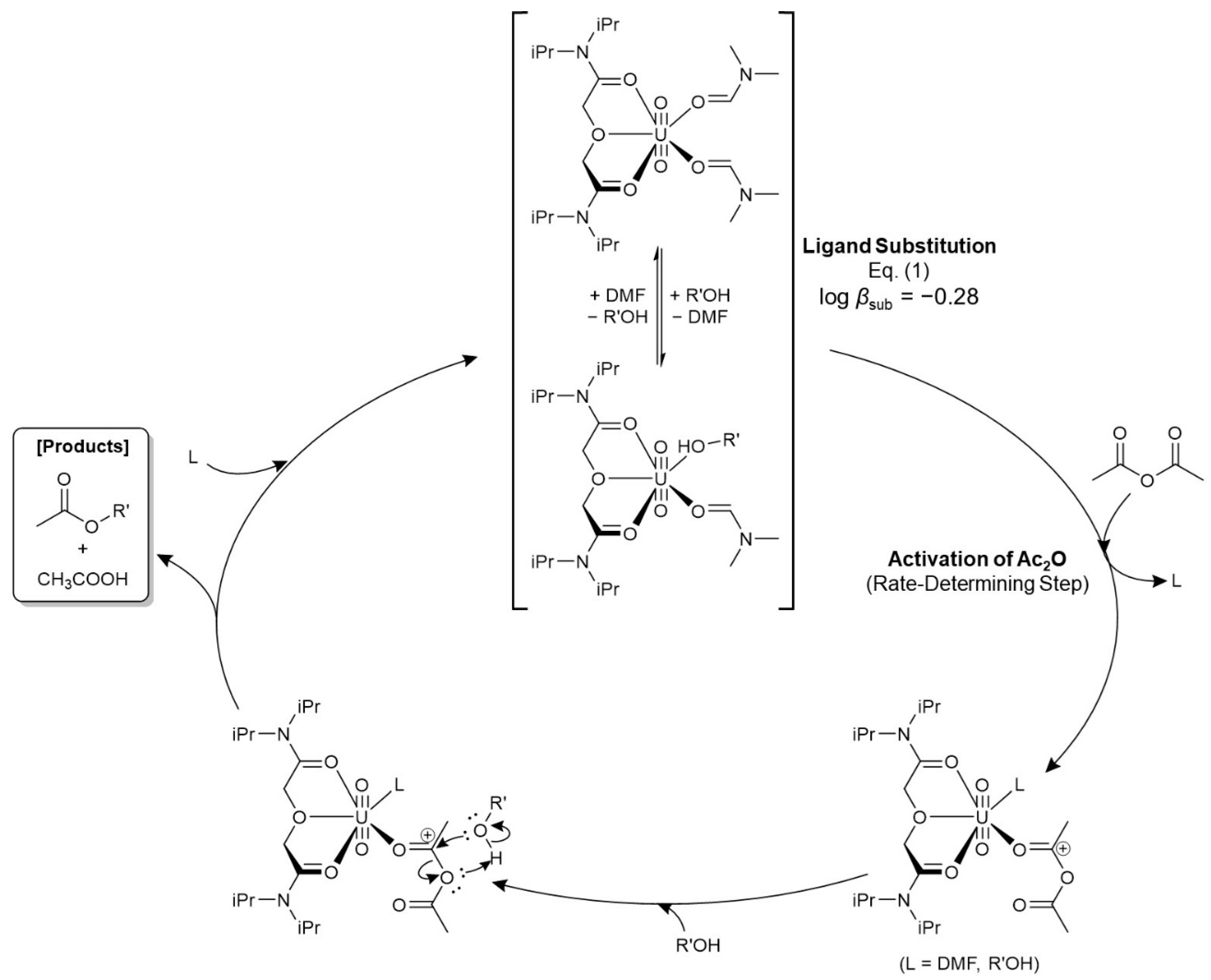

In summary, the overall rate equation of the current catalytic acyl substitution studied in

Figure 3 can be written down as follows.

where [U] denotes the concentration of the UO

22+ catalyst, [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ loaded. From the dependencies of

kini with [Ac

2O] and [DMF]

total in

Figure 3, the rate constant (

k5) of Eq. (5) was estimated to be 1.6 × 10

−4 s

−1 at 27.5°C. Based on this rate equation and additional mechanistic insight obtained above, the catalytic cycle of the acyl substitution reaction of Ac

2O with PhetOH mediated by [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ is proposed as shown in

Figure 5.

As a preliminary step of this catalytic system, the ligand substitution reaction between [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ and [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)(PhetOH)]

2+ (Eq. (1)) is rapidly equilibrated in a reaction mixture, where the second ligand substitution to form [UO

2(TiPDGA)(PhetOH)

2]

2+ is unlikely to occur probably due to steric hindrance between neighbouring PhetOH molecules. Ac

2O enters the equatorial plane of UO

22+ to replace one of the monodentate ligands. This is the rate-determining step of this catalytic reaction as defined by Eq. (5). It is hard to know which [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)

2]

2+ or [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)(PhetOH)]

2+ is an actual activator of Ac

2O, and which DMF or PhetOH is replaced by Ac

2O for its activation. Because of these circumstances, the monodentate ligands of intermediate species in

Figure 5 are simply denoted by “L”. Bidentate coordination of Ac

2O instead of both Ls as observed in our former system of [UO

2(OPPh

3)

4]

2+ [

22] is unlikely to occur, because

kini is independent of [PhetOH] as shown in

Figure 3(b) despite predominant formation of [UO

2(TiPDGA)(DMF)(PhetOH)]

2+ at the initial period of reaction as shown in

Figure S7 based on log

βsub of Eq. (1). The positively polarized carbonyl C of Ac

2O after its coordination to the U centre readily undergoes nucleophilic attack from PhetOH to afford PhetOAc and AcOH. These reaction products are immediately removed from UO

22+ due to weakly donating natures of esters (

DN ~17) and carboxylic acids (

DN = 10.5) [

31]. Finally, the UO

22+-TiPDGA complex returns to the initial state to repeat this catalytic cycle. The Lewis basicity of Ac

2O is actually not very strong as pronounced by

DN = 10.5 [

31]. This should be one of the reasons why the reaction kinetics currently observed are commonly slow. In connection with this, the equatorial plane of UO

22+ sterically constrained by tridentate TiPDGA would be another main cause of the slower reaction kinetics compared with that catalysed by [UO

2(OPPh

3)

4]

2+ we reported previously [

22].