Submitted:

26 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. International Impulses for Climate and Marine Research Since the 1980s

2. Material and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Some Background to the International Study of Climate Changes and Fluctuations in Fisheries (1914-1995)

3.2. Anthropogenic Global Warming vs Natural Global Warming

3.3. The Current Rapid Warming and Tropicalization in South European Atlantic Seas and Connecting African Regions

3.3.1. North Sea/Bay of Biscay/Iberian Coast

3.3.2. Fish Species Useful as Indicators of Environmental Changes

3.3.3. North West African Seas (Canary Current LME)

4. Some Examples and Proposals for the Future in a Global Warming Context

References

- Ocean Past Initiative. Tracing human interactions with marine ecosystems through deep time: implications for policy and management. In: Oceans Past VII. International Conference in Bremerhaven, Germany (22-26 October 2018). 2018. https://www.awi.de/forschung/besondere-gruppen/wissensplattform-erde-und-umwelt/opp7.html. https://www.tcd.ie/history/opi/.

- Pitcher, T.J. Fisheries managed to rebuild ecosystems? Reconstructing the past to salvage the future. Ecological Applications 2001, 11, 2, 601-617.

- Gordon, T.A.C.; Harding, H.R.; Clever, F.K.; Davidson, I.K.; Davison, W.; Montgomery, D.W.; Weatherhead, R.C.; Windsor, F.M.; Armstrong, J.D.; Bardonnet, A.; et al. Fishes in a changing world: learning from the past to promote sustainability of fish populations. J. Fish Biol. 2018, 92, 804–827. [CrossRef]

- Cooke, S.J.; Fulton, E.A.; Sauer, W.H.H.; Lynch, A.J.; Link, J.S.; Koning, A.A.; Jena, J.; Silva, L.G.M.; King, A.J.; Kelly, R.; et al. Towards vibrant fish populations and sustainable fisheries that benefit all: learning from the last 30 years to inform the next 30 years. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2023, 33, 317–347. [CrossRef]

- Holm, P.; Smith, T.D.; Starkey, D.J. The exploited seas: new directions for marine environmental history. International Maritime Economic History Association. St. John’s (Canada). 2001 .

- Holm, P.; Marboe, A.H; Poulsen, B.; MacKenzie, B. Marine animal populations: a new look back in time. In Life in the World's Oceans: Diversity, Distribution and Abundance. Wiley-Blackwell. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, 2010, pp. 3-23.

- Starkey, D.J.; Holm, P; Barnard, M. (eds.) 2008. Ocean Past: management insights from the history of marine animal populations. Earthscan. New York.

- Lotze, H.K.; Mcclenachan, L. Marine historical ecology: informing the future by learning from the past. Marine community ecology and conservation, 2013, 165-201.

- ICES. 2018. Report of the Working Group on the History of Fish and Fisheries (WGHIST), 4–7 September 2017, Lysekil, Sweden. ICES CM 2017/SSGEPI, 19. 56 p.

- Southward A.J.; Langmead O.; Hardman-Mountford, N.J.; Aiken J.; Boalch, G.T.; Dando, P.R.; Genner, M,J.; Joint, I.; Kendall, M.A.; Halliday, N.C.; Harris, R.P.; Leaper, R.; Mieszkowska, N.; Pingree, R.D.; Richardson, A.J.; Sims, D.W.; Smith, T.; Walne, A.W.; Hawkins, S.J. Long-term oceanographic and ecological research in the Western English Channel. Adv Mar Biol. 2005, 47, 1-105. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2881(04)47001-1.

- Poulsen, B.; Holm, P.; MacKenzie, B.R. A long-term (1667–1860) perspective on impacts of fishing and environmental variability on fisheries for herring, eel, and whitefish in the Limfjord, Denmark. Fish. Res. 2007, 87, 181–195. [CrossRef]

- Philippart, C.; Anadón, R.; Danovaro, R.; Dippner, J.; Drinkwater, K.; Hawkins, S.; Oguz, T.; O'Sullivan, G.; Reid, P.C. Impacts of climate change on European marine ecosystems: Observations, expectations and indicators. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2011, 400, 52–69. [CrossRef]

- Malta, T.; Santos, P.; Santos, A.; Rufino, M.; Silva, A. Long-term variations in Ibero-Atlantic sardine ( Sardina pilchardus ) population dynamics: Relation to environmental conditions and exploitation history. Fish. Res. 2016, 179, 47–56. [CrossRef]

- Van Beveren, E.; Fromentin, J.-M.; Rouyer, T.; Bonhommeau, S.; Brosset, P.; Saraux, C. The fisheries history of small pelagics in the Northern Mediterranean. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2016, 73, 1474–1484. [CrossRef]

- Fortibuoni, T.; Libralato, S.; Arneri, E.; Giovanardi, O.; Solidoro, C.; Raicevich, S. Fish and fishery historical data since the 19th century in the Adriatic Sea, Mediterranean. Sci. Data 2017, 4, 170104–170104. [CrossRef]

- Hernvann, P.-Y.; Gascuel, D. Exploring the impacts of fishing and environment on the Celtic Sea ecosystem since 1950. Fish. Res. 2020, 225, 105472. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Garrido, J.; Werner, F.; Fiechter, J.; Rose, K.; Curchitser, E.; Ramos, A.; Lafuente, J.G.; Arístegui, J.; Hernández-León, S.; Santana, A.R.; et al. Decadal-scale variability of sardine and anchovy simulated with an end-to-end coupled model of the Canary Current ecosystem. Prog. Oceanogr. 2018, 171, 212–230. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rubín, J.; A Historical Approach to Living Resources on the Spanish Coasts from the Alboran Sea Between the Sixteenth and Twentieth Centuries. In: Alboran Sea Ecosystems and Marine Resources. Báez, J.C; Vázquez, J-T.; Camiñas, J.A.; Malouli, M., Eds. Springer Nature, Switzerland. 2021, pp. 775-795.

- Thurstan, R.H. The potential of historical ecology to aid understanding of human-ocean interactions throughout the Anthropocene. J. Fish Biol. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Finney, B.P.; Alheit, J.; Emeis, K.-C.; Field, D.B.; Gutiérrez, D.; Struck, U. Paleoecological studies on variability in marine fish populations: A long-term perspective on the impacts of climatic change on marine ecosystems. J. Mar. Syst. 2010, 79, 316–326. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, J.H. An environmental (pre)history of European fishing: past and future archaeological contributions to sustainable fisheries. J. Fish Biol. 2019, 94, 1033–1044. [CrossRef]

- Pauly, D. Anecdotes and the shifting baseline syndrome of fisheries. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1995, 10, 430. [CrossRef]

- Pinnegar, J.K.; Engelhard, G.H. The ‘shifting baseline’ phenomenon: a global perspective. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2007, 18, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Bonebrake, T.C.; Christensen, J.; Boggs, C.L.; Ehrlich, P.R. Population decline assessment, historical baselines, and conservation. Conserv. Lett. 2010, 3, 371–378. [CrossRef]

- Soga, M.; Soga, M.; Gaston, K.J.; Gaston, K.J. Shifting baseline syndrome: causes, consequences, and implications. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2018, 16, 222–230. [CrossRef]

- Gilliland, R. L. Solar, volcanic and CO2 forcing of recent climatic changes. Climatic Change, 1982, 4, 111-131.

- Carbon Dioxide Review: 1982, W. C. Clark (ed.), Oxford University Press, 427 pp. Changing Climate: Report of the Carbon Dioxide Assessment Committee: 1983, National Research Council, National Academy Press, Washington D.C., 496 pp.

- Sherman K. and G. Hempel. 2008. Perspectives on Regional Seas and the Large Marine Ecosystem Approach. In: Sherman, K. and Hempel, G. (Editors) 2008. The UNEP Large Marine Ecosystem Report: A perspective on changing conditions in LMEs of the world’s Regional Seas. UNEP Regional Seas. Report and Studies, 182: 3-21.

- https://www.clivar.org/.

- http://www.ipcc.ch/.

- http://www.igbp.net/.

- Glantz, M.H.; Feingold, L.E. Climate variability, climate change, and fisheries: a summary. In: Climate Variability, Climate Change and Fisheries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1992, pp. 417-438.

- Everett, J.T.; A, Krovnin; D, Lluch-Belda.; E, Okemwa.; H.A, Regier.; and J.-P Troadec. Climate Change 1995: Impacts, Adaptations, and Mitigation of Climate Change: Scientific-Technical Analyses. In: Contribution of Working Group II to the Second Assessment Report of the IPCC. Watson, R.T.; Zinyowera M.C.; Moss, R.H. Eds. Cambridge University Press, New York, USA. 1996, 511-537.

- https://www.unep.org/unepmap/.

- https://eurogoos.eu/.

- http://www.esf.org/marineboard.

- https://argo.ucsd.edu/.

- IPCC. 2023. Climate Change 2021. The Physical Science Basis. Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press.

- Resumen Ejecutivo de CLIVAR-España 2019. El clima en la Península Ibérica.

- National Research Council (NRC). The Effects of Solar Variability on Earth's Climate: A Workshop Report; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Kusano, K. (ed.). Solar-Terrestrial Environmental Prediction. Springer Nature Singapore. 2023, XXIV, pp. 462. [CrossRef]

- Barange, M.; Bahri, T.; Beveridge, M. C. M.; Cochrane, K. L.; Funge-Smith, S.; Poulain, F. Impacts of climate change on fisheries and aquaculture. Synthesis of current knowledge, adaptation and mitigation options. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper, 2018, 627,1-628.

- IPCC, 2019. IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, M. Tignor, E. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Nicolai, A. Okem, J. Petzold, B. Rama, N.M. Weyer (eds.)].

- Bindoff, N. L.; Cheung, W. W. L.; Arístegui, J. G. K. J.; Guinder, V. A.; Hallberg, R.; Hilmi, N.; Williamson, P. Chapter 5: Changing Ocean, Marine Ecosystems, and Dependent Communities. In: IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. Pörtner, D.C.; Roberts, V.; Masson-Delmotte, P.; Zhai, M.; Tignor, E.; Poloczanska, K.; Mintenbeck, A.; Alegría, M.; Nicolai, A.; Okem, J.; Petzold, B.; Rama, N.M. Weyer.; Eds. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2019; vol 1155, 447-587. [CrossRef]

- Cooley, S.; Schoeman, D.; Bopp, L.; Boyd P.; Donner, S.; Ghebrehiwet, D.Y.; Ito, S.I.; Kiessling, W.; Martinetto, P.; Ojea, E.; Racault, M.-F.; Rost, B.; Skern-Mauritzen, M. 2022: Oceans and Coastal Ecosystems and Their Services. In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, M. Tignor, E.S. Poloczanska, K. Mintenbeck, A. Alegría, M. Craig, S. Langsdorf, S. Löschke, V. Möller, A. Okem, B. Rama (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 2023, 379–550. [CrossRef]

- Global Environment Monitoring System & World Water Quality Alliance: Freshwater, Air and Ocean. 2022. https://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/35879.

- https://marine.copernicus.eu/about#copernicus-marine-service.

- www.oceandecade.org.

- https://climate.copernicus.eu/.

- https://climate.copernicus.eu/sites/default/files/custom-uploads/ESOTC%202023/Summary_ESOTC2023.pdf.

- https://climate.copernicus.eu/esotc/2023/european-ocean.

- Ocean Decade Vision 2030. Draft Outcomes Report and White Papers (January 2024). https://oceanexpert.org/document/33599.

- UNESCO-IOC. The United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021-2030): Implementation Plan. Ocean Decade Science-Policy Interface Guidelines. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2021. url: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000377082.

- UNESCO-IOC. Ocean Decade Progress Report 2022–2023. UNESCO, Paris. The Ocean Decade Series, 2023, 46.

- UNESCO, 2017. Global Ocean Science Report—The current status of ocean science around the world.

- IOC-UNESCO. 2020. Global Ocean Science Report 2020–Charting Capacity for Ocean Sustainability.

- Potter, R.W.K.; Pearson, B.C. Assessing the global ocean science community: understanding international collaboration, concerns and the current state of ocean basin research. npj Ocean Sustain. 2023, 2, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- https://oceanexpert.org/event/3430.

- Schroeder, K.; Cardin, V.; Font, J.; Fuda, J.; Garcia Lafuente J.; Puig, P.; Taupier-Letage, I; Bengara, L.; Ismail, S. B; Bensi, M.; et al. Hydrochanges network: latest observations and links between time series. Rapp. Comm. Int. Mer Medit. 2010, 39, 180.

- Schroeder, K.; Millot, C.; Bengara, L.; Ben Ismail, S.; Bensi, M.; Borghini, M.; Budillon, G.; Cardin, V.; Coppola, L.; Curtil, C.; et al. Long-term monitoring programme of the hydrological variability in the Mediterranean Sea: a first overview of the HYDROCHANGES network. Ocean Sci. 2013, 9, 301–324. [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, K.; Chiggiato, J.; Bryden, H.L.; Borghini, M.; Ben Ismail, S. Abrupt climate shift in the Western Mediterranean Sea. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23009. [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, K.; Chiggiato, J.; Josey, S.A.; Borghini, M.; Aracri, S.; Sparnocchia, S. Rapid response to climate change in a marginal sea. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4065. [CrossRef]

- CIESM 2008. Climate warming and related changes in Mediterranean marine biota. CIESM Workshop Monographs, 2008, 35: 1-152.

- https://www.ciesm.org/marine/programs/tropicalization.htm.

- https://ciesm.org/online/atlas/.

- Golani, D.; Azzurro, E.; Dulčić, J.; Massutí, E.; Orsi-Relini, L. Atlas of Exotic Fishes in the Mediterranean Sea. F. Briand.; Ed. CIESM Publishers, Monaco. 2021, pp. 365.

- Galil, B.; Froglia, C.; Noël, P. Vol. 2: Crustaceans: decapods and stomatopods. In: CIESM Atlas of Exotic Species in the Mediterranean. Briand, F.; Ed. CIESM Publishers, Monaco. 2002, pp. 192.

- Zenetos, A.; Gofas, S.; Russo, G.; Templado, J. Vol. 3: Molluscs. In: CIESM Atlas of Exotic Species in the Mediterranean. Briand, F. Ed. CIESM Publishers, Monaco. 2003, pp. 376.

- Verlaque, M.; Ruitton, S.; Mineur, F.; Boudouresque, Ch-F. Vol. 4: Macrophytes. In: CIESM Atlas of Exotic Species. Briand, F.; Ed, CIESM Publisher, Monaco. 2015, pp. 362.

- Rijnsdorp, A. D., Peck, M. A., Engelhard, G. H., Möllmann, C., and Pinnegar, J. K. (Eds). 2010. Resolving climate impacts on fish stocks. ICES Cooperative Research Report, 301: 1-371.

- Drinkwater, K.F. Marine European climate: past, present, and future. Resolving climate impacts on fish stocks. In: ICES Cooperative Research Report. Rijnsdorp, A. D.; Peck, M. A.; Engelhard, G. H.; Möllmann, C.; and Pinnegar, J. K.; Eds. 2010, 301, 49-65.

- Pinnegar, J.K.; Engelhard, G. H.; Daskalov, G.M. Changes in the distribution of fish. Resolving climate impacts on fish stocks. In: ICES Cooperative Research Report. Rijnsdorp, A. D.; Peck, M. A.; Engelhard, G. H.; Möllmann, C.; and Pinnegar, J. K.; Eds. 2010, 301, 94-110.

- Predragovic, M.; Cvitanovic, C.; Karcher, D.B.; Tietbohl, M.D.; Sumaila, U.R.; e Costa, B.H. A systematic literature review of climate change research on Europe's threatened commercial fish species. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 242. [CrossRef]

- Meckler, A.N.; Trofimova, T.; Risebrobakken, B. & S. De Schepper. 14th International Conference on Paleoceanography. Past Global Changes Magazine, 2023, 31, 2, 116-117. [CrossRef]

- https://www.historicalclimatology.com/cliwoc.html.

- https://pastglobalchanges.org/about/general-overview.

- https://water.europa.eu/marine.

- https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/figures/european-marine-climate-change-index-emcci.

- Heip, C.; Barange, M.; Danovaro, R.; Gehlen, M.; Grehan, A.; Meysman, F.; Oguz, T.; Papathanassiou, V.; Philippart, C.; She, J.; et al. Climate Change and Marine Ecosystem Research. Synthesis of European Research on the Effects of Climate Change on Marine Environments. Marine Board Special Report. 2011. Ostend, Belgium, 1-151.

- https://www.ecmwf.int/en/about.

- http://ciesm.org/online/GISBiblio.php.

- https://ices-library.figshare.com/.

- Grainger, R.J.R.; Garcia, S.M. Chronicles of marine fishery landings (1950-1994): Trend analysis and fisheries potential. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper, 1996, 359, 1-51.

- https://www.cprsurvey.org/1409.

- Richardson, A.; Walne, A.; John, A.; Jonas, T.; Lindley, J.; Sims, D.; Stevens, D.; Witt, M. Using continuous plankton recorder data. Prog. Oceanogr. 2006, 68, 27–74. [CrossRef]

- http://biblioteca.ieo.es/biblio_ext.html.

- https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/152009 ; https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/158325.

- Pérez-Rubín, J. 2020. Investigaciones ictiológicas y pesqueras de la familia Lozano en el MNCN y su faceta divulgadora (1912-1970). In: Martín Albaladejo C. (ed.). Del elefante a los dinosaurios. 45 años de historia del Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales 1940-1985: 105-171.

- Tel E. Los repositorios marinos del IEO: la larga trayectoria de la Red de Mareógrafos y el Centro Español de Datos Oceanográficos durante más de 50 años. In: El estrecho de Gibraltar: llave natural entre dos mares y dos continentes. Pérez-Rubín J. & Teodoro Ramírez T. Eds. Bol. R. Soc. Esp. Hist. Nat. 2023, 16, 385-394.

- Valdés, L.; Lavín, A.; Fernández de Puelles, M.L.; Varela, M.; Anadón, R.; Miranda, A.; Camiñas, J.; Mas, J. Spanish Ocean Observation System. IEO Core Project: Studies on time series of oceanographic data. In: Operational Oceanography. Implementation at the European and Regional Scales. Flemming N.; Vallerga S.; Pinardi N.; et al.; Eds. 2002, pp. 99-105.

- IGN. 1991. El Medio Marino. In: Atlas Nacional de España, Sección III (13). Instituto Geográfico Nacional, MOPT, Madrid.

- https://repositorio.aemet.es/.

- https://www.aemet.es/en/serviciosclimaticos/datosclimatologicos/atlas_climatico.

- https://www.ipcc.ch/reports/.

- http://clivar.es/?page_id=1253.

- https://obis.org/about/.

- Smith T. D. Scaling Fisheries. The Science of Measuring the Effects of Fishing, 1855-1955. Cambridge University Press. 1994.

- Bigelow, H. Oceanography. Its Scope, Problems, and Economic Importance. The Riverside Press Cambridge, Boston. 1931.

- Garstang, W. The Impoverishment of the Sea. A Critical Summary of the Experimental and Statistical Evidence bearing upon the Alleged Depletion of the Trawling Grounds. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingd. 1900, 6, 1–69. [CrossRef]

- Hjort, J. Fluctuations in the great fisheries of northern Europe viewed in the light of biological research. ICES. 1914, 20, 1–228.

- Petterson, O.; Pettersson, O. Climatic variations in historic and prehistoric time. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. 1914, 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.D.; Wigley, T.M.L.; Wright, P.B. Global temperature variations between 1861 and 1984. Nature 1986, 322, 430–434. [CrossRef]

- Johannessen, O.M.; Bengtsson, L.; Miles, M.W.; Kuzmina, S.I.; Semenov, V.A.; Alekseev, G.V.; Nagurnyi, A.P.; Zakharov, V.F.; Bobylev, L.P.; Pettersson, L.H.; Hasselmann, K.; Cattle, H.P. Arctic climate change: observed and modelled temperature and sea-ice variability. Tellus, 2004, 56, 4, 328–341.

- Hughes, S.L.; Holliday, N.P.; Gaillard, F. Variability in the ICES/NAFO region between 1950 and 2009: observations from the ICES Report on Ocean Climate. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2012, 69, 706–719. [CrossRef]

- Hodson, D.L.R.; Robson, J.I.; Sutton, R.T. An Anatomy of the Cooling of the North Atlantic Ocean in the 1960s and 1970s. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 8229–8243. [CrossRef]

- Lluch-Belda, D.; Lluch-Cota, S.; LLuch-Cota, D.; Hernández-Vázquez, S. La variabilidad oceánica interanual y su impacto sobre las pesquerías. Rev. Soc. Mex. Hist. Natural, 1999, 49, 219-227.

- Cort, J.L.; Abaunza, P. The fall of the tuna traps and the collapse of the Atlantic Bluefin Tuna, Thunnus thynnus L.; fisheries of Northern Europe from the 1960s. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquacult. 2015, 23, 4, 346-373. [CrossRef]

- Cort, J. L.; Abaunza, P. The bluefin tuna fishery in the Bay of Biscay. Its relationship with the crisis of catches of large specimens in the East Atlantic Fisheries from the 1960s. Springer Briefs in Biology. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Philippart, C.; Anadón, R.; Danovaro, R.; Dippner, J.; Drinkwater, K.; Hawkins, S.; Oguz, T.; O'Sullivan, G.; Reid, P.C. Impacts of climate change on European marine ecosystems: Observations, expectations and indicators. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2011, 400, 52–69. [CrossRef]

- Belkin, I.M. Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems. Prog Oceanogr. 2009, 81, 207–213. [CrossRef]

- Nykjaer, L. Mediterranean Sea surface warming 1985–2006. Clim. Res. 2009, 39, 11–17. [CrossRef]

- Mann, M.E.; Jones, P.D. Global surface temperatures over the past two millennia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30. [CrossRef]

- Moberg, A.; Sonechkin, D.M.; Holmgren, K.; Datsenko, N.M.; Karlén, W. Highly variable Northern Hemisphere temperatures reconstructed from low- and high-resolution proxy data. Nature 2005, 433, 613–617. [CrossRef]

- Bakun, A. Global Climate Change and Intensification of Coastal Ocean Upwelling. Science 1990, 247, 198–201. [CrossRef]

- Russell, F.S.; Southward, A.J.; Boalch, G.T.; Butler, E.I. Changes in Biological Conditions in the English Channel off Plymouth during the Last Half Century. Nature 1971, 234, 468–470. [CrossRef]

- Southward, A. Fluctuations in the “indicator” chaetognaths Sagitta elegans and Sagitta setosa in the Western Channel. Oceanol. Acta, 1984, 7 (2), 220-239.

- Hansen, P. M. The stock of cod in Greenland waters during the years 1924-1952. Rapp. Reun. Cons. int. Explor. Mer. 1954, 136, 65–71.

- Binet, D.; Leroy, C. La pêcherie du ton rouge (Thynnus thynnus) dans l’Atlantique nord-est était-elle liée au réchauffement séculaire. ICCAT/SCRS, 1986, 86 (52), pp. 16.

- MacKenzie, B.R.; Myers, R.A. The development of the northern European fishery for north Atlantic bluefin tuna Thunnus thynnus during 1900–1950. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT, 2009, 63, 233-234. [CrossRef]

- Crowley, T.J.; Lowery, T.S. How Warm Was the Medieval Warm Period?. AMBIO 2000, 29, 51–54. [CrossRef]

- Drinkwater, K. F. Comparing the response of Atlantic cod stocks during the warming period of the 1920s-1930s to that in the 1990s-2000s. Deep Sea Res, 2009, 56, 2087-2096.

- Polyakov, I.V.; Alexeev, V.A.; Bhatt, U.S.; Polyakova, E.I.; Zhang, X. North Atlantic warming: patterns of long-term trend and multidecadal variability. Clim. Dyn. 2010, 34, 439–457. [CrossRef]

- Yamanouchi, T. Early 20th century warming in the Arctic: A review. Polar Sci. 2011, 5, 53–71. [CrossRef]

- Fridiksson, A. Boreo-tended changes in the marine vertebrata fauna of Iceland during the last twenty five years. Rapports et Procès-verbaux des Réunions. ICES, 1949, 125, 30-32.

- Johansen, A.C. On the Remarkable Quantities of Haddock in the Belt Sea during the Winter of 1925-26, and Causes leading to the same. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 1926, 1, 140–156. [CrossRef]

- Walford, L. A. Northward occurrence of southern fish off San Pedro in 1931. Calif. Fish. Game. 1931, 17, 401-405.

- McKenzie, R. A.; Homans, R. Rare and interesting fishes and salps in the Bay of Fundy and off Nova Scotia. Proc. N. S. Inst. Sci. 1938, 19 (3), 277.

- Lumby, J.R.; Atkinson, G.T. On the unusual Mortality amongst Fish during March and April 1929, in the North Sea. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 1929, 4, 309–332. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A. S. Concerning a change of climate during recent decades in the artic and subarctic regions, from Greenland in the West to Eurasia in the East and contemporary biological and geophysical changes. Det Konglike Videnskabernes Selska Biologiske Meddelelser, 1939, 14 (8), 1-75.

- Cushing, D. H.; Dickson, R. R. Biological and hydrographic changes in British waters during the last thirty years. Biol. Rev. 1976a, 41 (2), 221-258.

- Stephen, A.C. Temperature and the Incidence of Certain Species in Western European Waters in 1932-1934. J. Anim. Ecol. 1938, 7, 125–129. [CrossRef]

- Desbrosses, P. Capture d’une Tortue (Dermatochelys coriacea) dans la baie d’Etel. Bull Soc Zool Fr. 1932, 57, 274-277.

- Desbrosses, P. Echouage d’un Tetrodon T. lagocephalus pres de Quiberon et remarques sur la présense de cette éspèce et de Balistes capriscus au nord du 44º L. N. Bull Soc Zool Fr. 1935, 60, 43-48.

- Desbrosses, P. Présence à l’entrée occidentale de la Manche de Callanthias ruber. Bull Soc Zool Fr. 1936, 61, 406-407.

- Buen, F. Fluctuaciones en la sardina Sardina pilchardus. Pesca y medidas. Notas Resum. 1929, 35, 1-80.

- Anadón, E. Sobre la sustitución alternativa en el litoral gallego de los llamados peces emigrantes sardina, espadín, anchoa y jurel. Bol. Inst. Esp. Oceanogr. 1950, 24, 1-20.

- ICES. Comparative Studies of the Fluctuations in the Stocks of Fish in the seas of North and West Europe. Conseil Internat. pour l’Explor. de la Mer. Rapp. Et Proc.-Verb. Des Réunions, 1936, CI, part 3.

- Kemp, S. Oceanography and the fluctuations in the abundance of marine animals. Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, 1938, 85-101.

- Carruthers, J, N. Fluctuations n the herrins of the East Anglian Autumm fishery, the yield of the Ostend spent herring fishery and the haddock of the North Sea in the light of the relevant wind conditions. Rapports et Procès-verbaux des Réunions. ICES, 1938, 107, 1-15.

- Simpson, A.C. Some Observations on the Mortality of Fish and the Distribution of Plankton in the Southern North Sea during the Cold Winter, 1946-1947. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 1953, 19, 150–177. [CrossRef]

- Woodhead, P. M. Changes in the behavior of the sole Solea vulgaris during cold winters and the relation between the winter catch and sea temperatures. Helgoländer wissenschaftliche Meeresuntersuchungen, 1964, 10, 328-342.

- ICES. Contributions to Special Scientific Meetings 1948. Climatic changes in the Arctic in relation to plants and animals. Rapp. Cons. Explor. Mer, 1949, 125, 5-51.

- Brooks, C. Climate through the ages. A study of the climatic factors and their variations. E. Benn limited, 1926. 395 pp.

- Hubbs, C. Changes in the fish fauna of Western North America correlated with changes in ocean temperature. J. Mar. Res. 1948, 459-482.

- Fitch, J. E. The decline of the pacific mackerel fishery. Calif. Fish Game 1952, 38, 381-403.

- Ketchen, K. Climate trends and fluctuations in yield of marine fisheries in the North Pacific. J. Fish. Res. Board. Can. 1956, 13, 357-374.

- Uda, M. On the relation between the variation of the important fisheries conditions and the oceanographical conditions in the adjacent waters of Japan. J. Tokyo. Univ. Fish. 1952, 38 (3), 364-389.

- Bell, F.H.; Pruter, A.T. Climatic temperature changes and commercial yields of some marine fishes. J. Fish. Res. Board. Can 1958, 15, 625-83.

- Schweigger E. Die Westküste Südamerikas im Bereich des Peru-Stroms. Keysersche Verlagsbuchhandlung GmbH, Heidelberg-München. 1959.

- Rollefsen, G. Fluctuations in two of the most important stocks of fish in northern waters, the cod and the herring. Rapports et Procès-verbaux des Réunions. ICES, 1949, 125, 33-35.

- Hansen, P. Studies on the biology of the cod in Greenland waters. Rapports et Procès-verbaux des Réunions. ICES, 1949, 5-77.

- Rasmussen, B. On the migration pattern of the West Greenland stock of cod. Ann. Biol. 1959, 14, 123.

- Cushing, D.H.; Burd, A.C. On the herring of the Southern North Sea. Fishery Invest. 1957, 20 (11), 1-31.

- Cushing, D.H. The number of pilchards in the Channel. Fishery Invest. 1957, 21 (5), 27.

- Rees, W.J. The Distribution of Octopus Vulgaris Lamarck in British Waters. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingd. 1950, 29, 361–378. [CrossRef]

- Rees, W.J.; Lumby, J. R. The abundance of Octopus in the English Channel J. Mar. Biol. Ass. UK. 1954, 33, 515-136.

- Holme, N.A. The Bottom Fauna of the English Channel. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingd. 1961, 41, 397–461. [CrossRef]

- Shurin, T.A. Characteristic features of the bottom fauna in the eastern Baltic in 1959. Ann. Biol. 1961, 16 (1959), 86.

- Meyer, P.F.; Kalle, K. Die biologische Umstimmung in der Ostsee in den letzen Jahrezenten, eine Folge hydrographischer Wasserumschictungen. Archiv für Fischereiwissenschaft, 1950, 2, 1-9.

- Wyrtki, K. Der grosse Salzeinbruch in die Ostsee im november un december 1951. Kieler Meeresforschungen, 1954, 10 (1), 19-25.

- Fischer-Piette, E. Sur les déplacements des frontièrs biogeographiques intercotidales observables en Espagne: situation en 1954-55. CR. Acad. Sci. Paris. 1955, 241, 447-449.

- Fisher-Piette E. Sur les déplacements des frontières biogéographiques intercotidales, actuellement en cours en Espagne: situation en 1956. CR. Acad. Sci. Paris. 1956, 242, 2782-2784.

- Fisher-Piette E. Sur les progrés des espèces septentrionales dans le bios inter-cotidale ibérique: situation en 1956-1957. CR. Acad. Sci. Paris. 1957a, 245, 373–375.

- Fisher-Piette E. Sur les déplacements de frontières biogéographiques, observables au long des cotes ibériques dans le domaine intercotidal. Inst. Biol. Aplic. 1957b, 26, 35–40.

- Fisher-Piette E. Sur l’écologie intercotidale ouest-ibérique. Comptes Rendus. Academie des Sciences, Paris, 1958, 245, 373–375.

- Fisher-Piette E. La distribution des principaux organismes nord iberiques en 1954-1955. Ann. Inst. Ocean. Monaco, 1963, 40 (3), 165-311.

- Navaz, J. Mª. Nuevos datos sobre la sustitución alternativa en la pesca de peces emigrantes en el litoral de Galicia. Notas Resum. 1946a, 132, 1-9.

- Navaz J. Mª. Sobre algunos peces poco frecuentes o desconocidos en las costas de Galicia. Notas Resum. 1946b, 133, 1-9.

- Navaz, J. Mª. Sobre algunos peces poco frecuentes o desconocidos en la costa vasca. Bol. Inst. Esp. Oceanogr. 1961, 106, 1-48.

- Carson. The Sea Around Us, Oxford University Press, USA, 1952, pp. 182.

- Conti A. Râcleurs d’Océans. Paris, Payot & Rivages. 1953.

- Sette, 0. E. The long term historical record of meteorological, oceanographic and biological data. Calif. Coop. Oceanic Fisheries Invest. Rep. 1960, 7, 181-194.

- Sette, 0. E. Problems in fish population fluctuations. Calif. Coop. Oceanic Fisheries Invest. Rep. 1961, 8, 21-24.

- Crisp, D.J. The Effects of the Severe Winter of 1962-63 on Marine Life in Britain. J. Anim. Ecol. 1964, 33, 165. [CrossRef]

- Rodewald, M. Sea-surface temperatures of the North Atlantic Ocean during the decade 1951–60. In: Changes of Climate, Proceedings of the Rome Symposium, Arid Zone Research, 1963, 20, 97–107. UNESCO, Paris.

- Stearns, F. Sea-surface temperature anomaly study of records from Atlantic coast stations. J. Geophys. Res. 1965, 70, 283–296. [CrossRef]

- Fairbridge, R.W. Mean sea level related to solar radiation during the last 20,000 years. In: Changes of Climate. Proceedings, Rome Symposium, 1960 UNESCO, Paris, 1963, 229–242.

- Beverton, R. J. H.; Lee, A. J. Hydrodynamic fluctuations in the North Atlantic Ocean and some biological consequences. In: Johnson C. G. & Smith L. P. eds. The Biological significance of Climatic Changes in Britain. Institute of Biology Symposia, 1965, 14, 79-107.

- Zupanovitch, S. Causes of fluctuations in sardine catches along the Eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea. Anali Jadranskog Instituta, 1968, 4, 401-489.

- Wyatt, T.; Porteiro, C. The Iberian Sardine Fisheries: Trends and Crises. In: Large Marine Ecosystems. Sherman, K.; Skjoldal, H.; Eds. Elsevier, 2002, 321-338.

- Cendrero, O. Sardine and anchovy crises in northern Spain: natural variations or an effect of human activities?. ICES Marine Science Symposia, 2002, 215, 279-285. [CrossRef]

- Hernvann, P.-Y.; Gascuel, D. Exploring the impacts of fishing and environment on the Celtic Sea ecosystem since 1950. Fish. Res. 2020, 225, 105472. [CrossRef]

- Lamb, H.H. Climate: Past, Present and Future. I. Fundamentals and Climate Now. 1972, pp. 1-624.

- Cushing, D.H. Marine Ecology and Fisheries. CUP Archive, 1975.

- Cushing, D.H.; Dickson R.R. The biological response in the sea to climatic changes. Adv. Mar. Biol. 1976b, 14, 1-122. [CrossRef]

- Mörner, N-A.; Karlén, W. 1984 Climatic changes on a yearly to millennial basis: geological, historical, and instrumental records. Proceedings of the II Nordic Symposium on Climatic Changes and Related Problems (Stockholm, Sweden, May 16-20, 1983). Reidel Pub., Dordrecht. 1984.

- Mörner, N.A. Oceanic circulation changes and redistribution of energy and mass on a yearly to centenary time-scale. Symposium Long Term Changes in Marine Fish Populations. Vigo, Spain. Contribution 3. 1986.

- Cushing, D.H. Climate and fisheries. Academic Press, London (UK). 1982. XIV, pp. 373.

- Caddy, J.; Gulland, J. Historical patterns of fish stocks. Mar. Policy 1983, 7, 267–278. [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, T.; Omori, M. Fluctuations in the three major sardine stocks in the Pacific and the global trend in temperature. In: Proc. Long Term Changes in Marine Fish Populations. Vigo, Spain: Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas de Vigo. 1988, 37–53.

- Dickson, R.R.; Meinecke, J.; Malmberg, S.A.; Lee, A.J. The "great salinity anomaly" in the northern North Atlantic 1968-1982. Prog Oceanogr. 1988, 20, 103-151.

- Cushing, D. Population, production and regulation in the sea: A fisheries perspective. Cambridge University Press. 1995.

- Bakun, A.; Parrish, R.H. Environmental inputs to fishery population models for eastern boundary current regions. In: Workshop on the effects of environmental variation on the survival of larval pelagic fishes. Sharp, G.D. Ed. UNESCO, Paris. IOC Workshop Rep. 1980, 28, 67-104.

- Southward, A.J.; Boalch, G.T.; Maddock, L. Fluctuations in the herring and pilchard fisheries of devon and cornwall linked to change in climate since the 16th century. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingd. 1988, 68, 423–445. [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, J.O. A three-dimensional model for the simulation of shelf sea dynamics. Dtsch. Hydrogr. Z. 1985, 38, 165–187. [CrossRef]

- Bartsch, J.; Brander, K.; Heath, M.; Munk, P.; Richardson, K.; Svendsen, E. Modelling the advection of herring larvae in the North Sea. Nature 1989, 340, 632–636. [CrossRef]

- Bardach, J.E.; Santerre, R.M. Climate and Aquatic Food Production. In: Food Climate Interactions. Bach, W.; Pankrath, I.; Schneider. S. H.; Eds. 1981, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- Frye, R. Climatic change and fisheries management. Nat. Resour. J. 1983, 23, 77-96.

- Sibley, T.H.; Strickland, R.M. Fisheries: Some Relationships to Climate Change and Marine Environmental Factors. In: Characterization of Information Requirements for Studies of CO2 Effects: Water, Resources, Agriculture, Fisheries, Forests and Human Health. White, M. R.; Ed. United States Department of Energy, Carbon Dioxide Research Division, Washington, D.C.; 1985, 95-143.

- Shepherd, J.G.; Pope, J.G.; Cousen, R.D. Variations in fish stocks and hypotheses concerning their links with climate. Rapp. Procès-Verb. Réun. Cons. Int. Explor. Mer, 1984, 185, 255-267.

- Pérez-Rubín J. El Ictioplancton del mar de Alborán: Relación de su distribución espacio-temporal y composición con diferentes parámetros ambientales y con la distribución de los peces adultos. PhD Thesis. 1996. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rubín, J.; Mafalda, P. Abnormal domination of gilt sardine (Sardinella aurita) in the middle shelf ichthyoplankton community of Gulf of Cádiz (SW Iberian Peninsula) in summer: related changes in the hydrologic structure and implications in the larval fish and mesozooplankton assemblages finded. ICES Annual Science Conference Vigo, Spain 22–25 September 2004. ICES CM 2004/Q: 23, 1-9.

- Pérez-Rubín, J.; Abad, R. La presencia masiva ocasional de larvas y adultos de Capros aper (Pisces) en el Golfo de Cádiz y Mar de Alborán. Gaia Rev Geociencias, 1994, 9, 23-26.

- Sharp, G.D.; Csirke, J. eds. Proceedings of the Expert Consultation to examine changes in abundance and species composition of neritic fish resources. San José, Costa Rica, 18-29 April 1983. FAO Fisheries Report, 1983, 291 (2-3), 1-1224.

- Csirke, J.; Sharp, G.D. eds. Reports of the Expert Consultation to examine changes in abundance and species composition of neritic fish resources. San José, Costa Rica, 18-29 April 1983. FAO Fisheries Report, 1984, 291 (1), 1-102.

- Wyatt, T.; Larrañeta, M.G. eds. Long Term Changes in Marine Fish Populations. International Symposium Vigo, Spain, 18-21 Nov, 1986. 1988.

- López-Areta, J.M.; Villegas, M.L. Annual and seasonal changes in the captures of Sardina pilchardus, Trachurus trachurus, Engraulis encrasicolus and Scomber scombrus on the coast of Asturias (1952-1985). International Symposium on Long Term Changes in Marine Fish Populations 18-21 November 1986, Vigo, Spain. 1986. Abstract nº 35.

- Villegas, M.L.; López-Areta, J.M. Annual and seasonal changes in captures of Brama raii, Pagellus bogaraveo, Thunnus alalunga, Micromesistius poutassou, Merluccius merluccius and Lophius piscatorius on the coast of Asturias (1952-1985). International Symposium on Long Term Changes in Marine Fish Populations 1986. 18-21 November 1986, Vigo, Spain. Abstract nº 39.

- Junquera, S. Changes in the anchovy fishery of the Bay of Biscay in relation to climatic and oceanographic variations in the Nort Atlantic. In: Long Term Changes in Marine Fish Populations. Wyatt, T.; Larrañeta, M.G.; Eds. International Symposium 1988. Vigo, Spain, 18-21 Nov. 1986, 543-554.

- Porteiro, C.; Álvarez, F.; Pérez, N. Variations in the sardine Sardina pilchardus stock of the Atlantic coast of the Iberian Peninsula (1976-1985). International Symposium on Long Term Changes in Marine Fish Populations, 1986, 18-21 November 1986, Vigo, Spain. Abstract nº 36.

- Wyatt, T.; Pérez-Gándaras, C. Ekman transport and sardine yields in western Iberia. International Symposium on Long Term Changes in Marine Fish Populations, 1986, 18-21 November 1986, Vigo, Spain. Abstract nº 37.

- Binet, D.; French sardine and herring fisheries: a tentative description of their fluctuations since the XVIII th century. In: Long Term Changes in Marine Fish Populations. Wyatt, T.; Larraneta, M.G. Eds. Symposium held 18-20 November 1986, Vigo, Spain, 1988, 253-272.

- Regier, H.A.; Magnuson, J.J.; Coutant, C.C. Introduction to Proceedings: Symposium on Effects of Climate Change on Fish. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 1990, 119, 173–175. [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, T.; Tanaka, S.; Toba, Y.; Taniguchi, A. eds. Long-term variability of pelagic fish populations and their environment. Proceedings of the international symposium, Sendai, Japan, 14-18 November 1989. Pergamon Press, Oxford UK, 1991, 402.

- Wyatt, T.; Cushing D.H.; Junquera, S. Stock distinctions and evolution of European sardine. In: T. Kawasaki, S. Tanaka, Y. Toba, and A. Taniguchi eds. Long-term Variability of Pelagic Fish Populations and their Environment. Pergamon Press, 1991, 229-238.

- Souter. A.; Isaacs, J. D. Abundance of pelagic fish during the 19th and 20th centuries as recorded in anaerobic sediments off California. Fish. Bull. 1974, 72, 257-275.

- De Vries, Th. J.; Pearcy, W. G. Fish debris in sediments of the upwelling zone off central Peru: a late Quaternary record. Deep. Sea. Res. Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers, 1982, 29 (1), 87-109.

- Shackleton, L.Y. Fossil pilchard and anchovy scales: indicators of past fish populations off Namibia. In: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Long Term Changes in Fish Populations. Vigo, Spain: Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas de Vigo, 1988, 55-68.

- Shackleton, L.Y. A comparative study of fossil fish scales from three upwelling regions. South Afr. J. Mar. Sci. 1987, 5, 79–84. [CrossRef]

- Sherman, K.; Alexander, L.M. Large marine ecosystems: Patterns, processes and yields. American Association for the Advancement of Science: Washington D.C. XIII, 1990, pp. 242.

- Bakun, A. Patterns in the Ocean: Ocean Processes and Marine Population Dynamics. La Jolla, CA: California Sea Grant. 1996, pp. 323.

- Beamish, R.J. ed. Climate change and northern fish populations. NRC Research Press, 1995, 121, pp. 739.

- Mörner, N.-.-A. Earth rotation, ocean circulation and paleoclimate. GeoJournal 1995, 37, 419–430. [CrossRef]

- Lean, J.; Beer, J.; Bradley, R. Reconstruction of solar irradiance since 1610: Implications for climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1995, 22, 3195–3198. [CrossRef]

- Mörner, N.A. Global Change and Interaction of Earth Rotation, Ocean Circulation and Paleoclimate. An. Acad. Bras. Ci.; 1996, 68 (1), 77-94.

- Mörner N.A. Solar wind, earth’s rotation and changes in terrestrial climate. Physical Review & Research International. 2013, 3 (2), 117-136.

- Friis-Christensen, E.; Lassen, K. Length of the Solar Cycle: An Indicator of Solar Activity Closely Associated with Climate. Science 1991, 254, 698–700. [CrossRef]

- Butler, C.; Johnston, D. A provisional long mean air temperature series for Armagh observatory. J. Atmospheric Terr. Phys. 1996, 58, 1657–1672. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, R.T.; Prokoph, A.; Wright, C.; Chang, A.S.; Thomson, R.E.; Ware, D.M. Holocene Solar Variability and Pelagic Fish Productivity in the NE Pacfic. Palaeontologia Electronica, 2004, 7 (4), 17 p. http://palaeo-electronica.org/paleo/2004_3/fish2/issue1_04.htm.

- Ganzedo, U.; Zorita, E.; Solari, A.P.; Chust, G.; del Pino, A.S.; Polanco, J.; Castro, J.J. What drove tuna catches between 1525 and 1756 in southern Europe?. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2009, 66, 1595–1604. [CrossRef]

- Ganzedo, U.; Polanco-Martínez, J.M.; Caballero-Alfonso, .M.; Faria, S.H.; Li, J.; Castro-Hernández, J.J. Climate effects on historic bluefin tuna captures in the Gibraltar Strait and Western Mediterranean. J. Mar. Syst. 2016, 158, 84–92. [CrossRef]

- Guisande, C.; Ulla, A.; Thejll, P. Solar activity governs abundance of Atlantic Iberian sardine Sardina pilchardus. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2004, 269, 297–301. [CrossRef]

- Boehlert G.W.; Schumacher J.D. Changing Oceans and Changing Fisheries: Environmental Data for Fisheries Research and Management. NOAA-TM-NMFS-SWFSC-239. U.S. Department of Commerce. 1997, pp. 147.

- Barnett, T.P.; Hasselmann, K.; Chelliah, M.; Delworth, T.; Hegerl, G.; Jones, P.; Rasmusson, E.; Roeckner, E.; Ropelewski, C.; Santer, B.; et al. Detection and Attribution of Recent Climate Change: A Status Report. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1999, 80, 2631–2659. [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2007. Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC, 2007, Geneva, Switzerland, 104 pp.

- IPCC. IPCC Third Assessment Report: Climate Change 2001. The Scientific Basis, Ginebra. 2001.

- Steffen W.; Sanderson A.; Tyson P.; Jäger J.; Matson P.; Moore B.; Oldfield F.; Richardson K.; Schellnhuber H.J.; Turner B.L.; Wasson R.J. Global Change and the Earth System: A Planet Under Pressure. Springer Berlin, Heidelberg. 2004, 336 pp. [CrossRef]

- Stef, W. Observed trends in Earth System behavior. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2010, 1, 428–449. [CrossRef]

- Pörtner H.-O.; Roberts, D.C; Eds. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. IPCC 2022. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 2022, pp. 3056. [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency. Climate change mitigation: reducing emissions (Modified 25 Mar 2024). URL: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/topics/in-depth/climate-change-mitigation-reducing-emissions.

- Palmer, M.D.; Domingues, C.M.; A Slangen, A.B.; Dias, F.B. An ensemble approach to quantify global mean sea-level rise over the 20th century from tide gauge reconstructions. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 044043. [CrossRef]

- Rind, D.; Shindell, D.; Perlwitz, J.; Lerner, J.; Lonergan, P.; Lean, J.; McLinden, C. The Relative Importance of Solar and Anthropogenic Forcing of Climate Change between the Maunder Minimum and the Present. J. Clim. 2004, 17, 906–929. [CrossRef]

- Mörner, N.-A. Our Oceans-Our Future: New Evidence-based Sea Level Records from the Fiji Islands for the Last 500 years Indicating Rotational Eustasy and Absence of a Present Rise in Sea Level. Int. J. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 2. [CrossRef]

- Mörner, N.A. Chapter 2: 2500 Years of Observations, Deductions, Models and Geoethics: Global Perspective. Boll. Soc. Geol. It, 2006, vol. 125, pp. 259-264. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Tinsley, B.; Chu, H.; Xiao, Z. Correlations of global sea surface temperatures with the solar wind speed. J. Atmospheric Solar-Terrestrial Phys. 2016, 149, 232–239. [CrossRef]

- Herrera, V.V.; Mendoza, B.; Herrera, G.V. Reconstruction and prediction of the total solar irradiance: From the Medieval Warm Period to the 21st century. New Astron. 2015, 34, 221–233. [CrossRef]

- Jardine, P.E.; Fraser, W.T.; Gosling, W.D.; Roberts, C.N.; Eastwood, W.J.; Lomax, B.H. Proxy reconstruction of ultraviolet-B irradiance at the Earth’s surface, and its relationship with solar activity and ozone thickness. Holocene, 2010, 30, 155–161.

- Miyahara H.; Ayumi Asai A.; Ueno S. Solar Activity in the Past and Its Impacts on Climate. In: Solar-Terrestrial Environmental Prediction. Kusano, K. Eds. Springer, Singapore, 2023, 403-419.

- Thiéblemont, R.; Matthes, K.; Omrani, N.-E.; Kodera, K.; Hansen, F. Solar forcing synchronizes decadal North Atlantic climate variability. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8268. [CrossRef]

- Patti, B.; Guisande, C.; Riveiro, I.; Thejll, P.; Cuttitta, A.; Bonanno, A.; Basilone, G.; Buscaino, G.; Mazzola, S. Effect of atmospheric CO2 and solar activity on wind regime and water column stability in the major global upwelling areas. Estuarine, Coast. Shelf Sci. 2010, 88, 45–52. [CrossRef]

- Landscheidt, T. New Little ICE Age Instead of Global Warming?. Energy Environ. 2003, 14, 327–350. [CrossRef]

- Mörner NA. Solar minima, earth’s rotation and little ice ages in the past and in the future. The North Atlantic – European case. Global Planet. Change. 2010, 72, 282-293.

- Mörner, N.-A. The Approaching New Grand Solar Minimum and Little Ice Age Climate Conditions. Nat. Sci. 2015, 07, 510–518. [CrossRef]

- Mörner, N.-A. Anthropogenic Global Warming (AGW) or Natural Global Warming (NGM). Voice Publ. 2018, 04, 51–59. [CrossRef]

- Meehl, G.A.; Arblaster, J.M.; Marsh, D.R. Could a future “Grand Solar Minimum” like the Maunder Minimum stop global warming? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 1789–1793. [CrossRef]

- Feulner, G.; Rahmstorf, S. On the effect of a new grand minimum of solar activity on the future climate on Earth. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37, L05707. [CrossRef]

- Arsenovic, P.; Rozanov, E.; Anet, J.; Stenke, A.; Schmutz, W.; Peter, T. Implications of potential future grand solar minimum for ozone layer and climate. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 18, 3469–3483. [CrossRef]

- Maycock, A.C.; Ineson, S.; Gray, L.J.; Scaife, A.A.; Anstey, J.A.; Lockwood, M.; Butchart, N.; Hardiman, S.C.; Mitchell, D.M.; Osprey, S.M. Possible impacts of a future grand solar minimum on climate: Stratospheric and global circulation changes. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2015, 120, 9043–9058. [CrossRef]

- Ineson, S.; Maycock, A.C.; Gray, L.J.; Scaife, A.A.; Dunstone, N.J.; Harder, J.W.; Knight, J.R.; Lockwood, M.; Manners, J.C.; Wood, R.A. Regional climate impacts of a possible future grand solar minimum. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7535. [CrossRef]

- Chiodo, G.; García-Herrera, R.; Calvo, N.; Vaquero, J.M.; A Añel, J.; Barriopedro, D.; Matthes, K. The impact of a future solar minimum on climate change projections in the Northern Hemisphere. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 034015. [CrossRef]

- Yoden, S.; Yoshida, K. Impacts of Solar Activity Variations on Climate. In: Kusano, K. eds Solar-Terrestrial Environmental Prediction. Springer, Singapore. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Tartaglione, N.; Toniazzo, T.; Otterå, O.H.; Orsolini, Y. Equilibrium Climate after Spectral and Bolometric Irradiance Reduction in Grand Solar Minimum Simulations. Climate 2023, 12, 1. [CrossRef]

- Scafetta, N. Empirical assessment of the role of the Sun in climate change using balanced multi-proxy solar records. Geosci. Front. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Kopp, G.; Lean, J.L. A new, lower value of total solar irradiance: Evidence and climate significance. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38. [CrossRef]

- Giralt, S.; Moreno, A.; Cacho, I.; Valero-Garcés, B. A comprehensive overview of the last 2,000 years Iberian Peninsula climate history. In: Special Issue on climate over the Iberian Peninsula: an overview of CLIVAR-Spain coordinated science. Clivar Exchanges, 2017, 73, 5-10.

- MacKenzie, B.; Christensen. Disentangling climate from antropogenic effects. In: Resolving climate impacts on fish stocks. Rijnsdorp A. D.; Peck M. A.; Engelhard G.H.; Möllmann C.; Pinnegar J. K. eds. ICES Cooperative Research Report, 2010, 301, 44-48.

- Belkin, I.M. Rapid warming of Large Marine Ecosystems. 2009, 81, 207–213. [CrossRef]

- Spalding, M.D.; Fox, H.E.; Allen, G.R.; Davidson, N.; Ferdaña, Z.A.; Finlayson, M.; Halpern, B.S.; Jorge, M.A.; Lombana, A.; Lourie, S.A.; et al. Marine Ecoregions of the World: A Bioregionalization of Coastal and Shelf Areas. Bioscience 2007, 57, 573–583. [CrossRef]

- Kämpf, J.; Chapman, P. 2016. The Canary/Iberia Current Upwelling System. In: Upwelling Systems of the World. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Sherman K.; Hempel, G. 2008. Perspectives on Regional Seas and the Large Marine Ecosystem Approach: pp. 3-21. In: Sherman, K. and Hempel, G. (Editors) 2008. The UNEP Large Marine Ecosystem Report: A perspective on changing conditions in LMEs of the world’s Regional Seas. UNEP Regional Seas. Report and Studies, 182. United Nations Environment Programme. Nairobi, Kenya.

- https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/figures/marine-regions-and-subregions.

- Zeller, D.; Hood, L.; Palomares, M.; Sumaila, U.; Khalfallah, M.; Belhabib, D.; Woroniak, J.; Pauly, D. Comparative fishery yields of African Large Marine Ecosystems. Environ. Dev. 2020, 36, 100543. [CrossRef]

- Chust, G.; González, M.; Fontán, A.; Revilla, M.; Alvarez, P.; Santos, M.; Cotano, U.; Chifflet, M.; Borja, A.; Muxika, I.; et al. Climate regime shifts and biodiversity redistribution in the Bay of Biscay. Sci. Total. Environ. 2022, 803, 149622. [CrossRef]

- Zenetos, A.; Tsiamis, K.; Galanidi, M.; Carvalho, N.; Bartilotti, C.; Canning-Clode, J.; Castriota, L.; Chainho, P.; Comas-González, R.; Costa, A.C.; et al. Status and Trends in the Rate of Introduction of Marine Non-Indigenous Species in European Seas. Diversity 2022, 14, 1077. [CrossRef]

- Png-Gonzalez, L.; Comas-González, R.; Calvo-Manazza, M.; Follana-Berná, G.; Ballesteros, E.; Díaz-Tapia, P.; Falcón, J.M.; Raso, J.E.G.; Gofas, S.; González-Porto, M.; et al. Updating the National Baseline of Non-Indigenous Species in Spanish Marine Waters. Diversity 2023, 15, 630. [CrossRef]

- Carreira-Flores, D.; Rubal, M.; Moreira, J.; Guerrero-Meseguer, L.; Gomes, P.T.; Veiga, P. Recent changes on the abundance and distribution of non-indigenous macroalgae along the southwest coast of the Bay of Biscay. Aquat. Bot. 2023, 189. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lloréns, J.L.; Brun F.G.; Hernández, I.; Bermejo R.; Vergara J.J. 2023. Macrofitos marinos (algas y angiospermas) de las costas de Cádiz. In: Pérez-Rubín J. & Ramírez T. (ed). El estrecho de Gibraltar: llave natural entre dos mares y dos continentes. R. Soc. Esp. Hist. Nat. Memorias, 2023, 16, 133-151.

- Heath, M. R. 2007. Responses of fish to climate fluctuations in the Northeast Atlantic. In: The Practicalities of Climate Change: Adaptation and Mitigation: 102-116. Ed. by L. E. Emery. Proceedings of the 24th Conference of the Institute of Ecology and Environmental Management, Cardiff, 14-16 November 2006.

- Kaimuddin, A.H.; Laë, R.; De Morais, L.T. Fish Species in a Changing World: The Route and Timing of Species Migration between Tropical and Temperate Ecosystems in Eastern Atlantic. Front. Mar. Sci. 2016, 3, 162. [CrossRef]

- NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies. https://science.nasa.gov/climate-change/scientific-consensus/.

- https://climate.copernicus.eu/esotc/2023https://climate.copernicus.eu/sites/default/files/custom-uploads/ESOTC%202023/Summary_ESOTC2023.pdf.

- https://www.ecmwf.int/en/about/media-centre/news/2024/europe-saw-widespread-flooding-and-severe-heatwaves-2023-report.

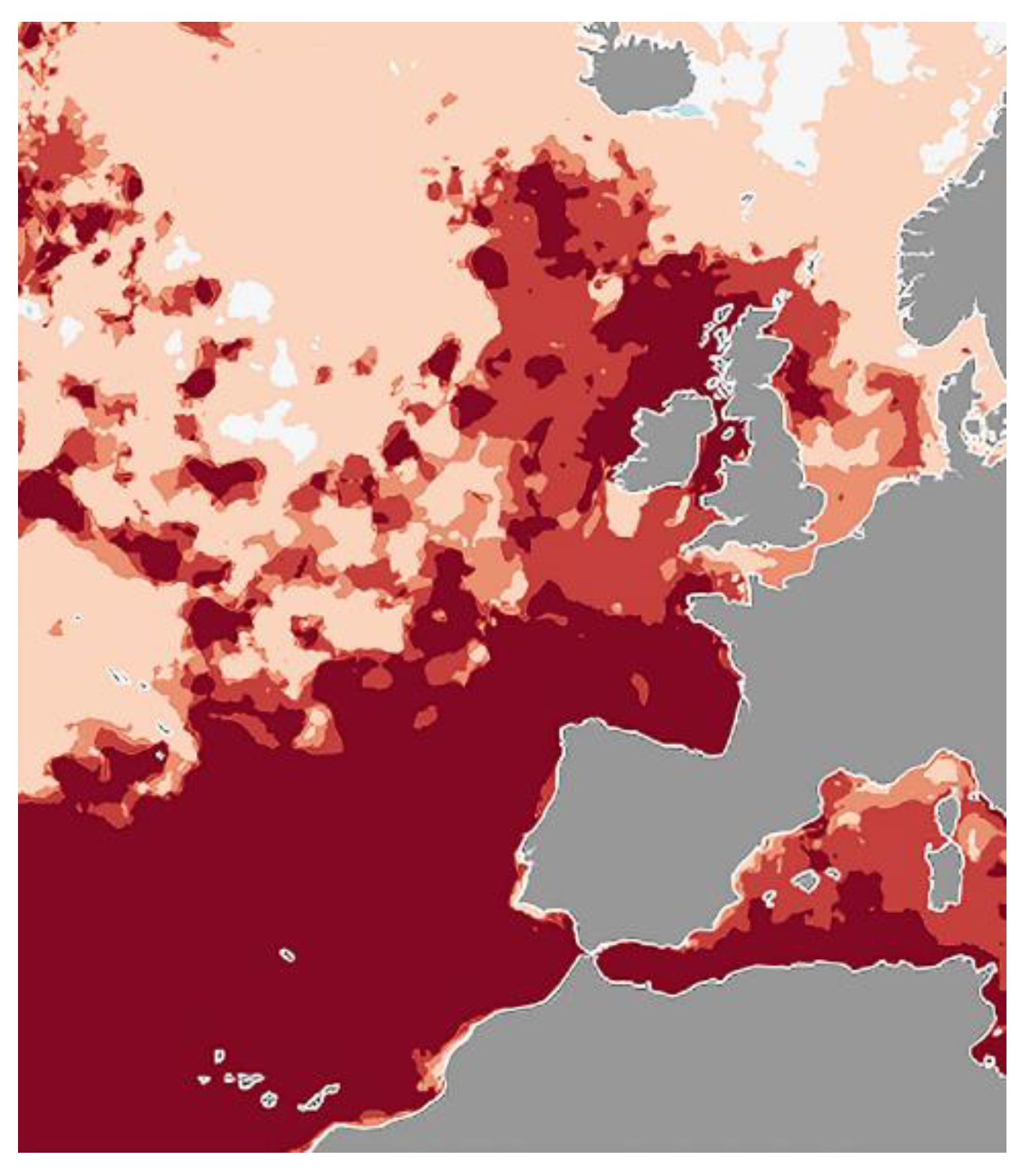

- ECMWF, 2024. Europe saw widespread flooding and severe heatwaves in 2023-Report [https://www.ecmwf.int/en/about/media-centre/news/2024/europe-saw-widespread-flooding-and-severe-heatwaves-2023-report]. https://www.ecmwf.int/sites/default/files/styles/wide/public/2024-04/Ranking-annual-sea-surface-temperatures-2023_690px.png?itok=02E1PCTC.

- The NOAA Fisheries Distribution Mapping and Analysis Portal (DisMAP). https://apps-st.fisheries.noaa.gov/dismap/.

- FAO. 2020. FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture - Aquatic Species Distribution Map Viewer. In: FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Division [online]. Rome. https://www.fao.org/figis/geoserver/factsheets/species.html.

- Domínguez-Petit, R.; Navarro, M.R.; Cousido-Rocha, M.; Tornero, J.; Ramos, F.; Jurado-Ruzafa, A.; Nunes, C.; Hernández, C.; Silva, A.V.; Landa, J. Spatial variability of life-history parameters of the Atlantic chub mackerel (Scomber colias), an expanding species in the northeast Atlantic. Sci. Mar. 2022, 86, e048–e048. [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.; Hidalgo, M.; Puerta, P.; Sánchez-Leal, R.; Rueda, L.; Sobrino, I. Concurrent changes in spatial distribution of the demersal community in response to climate variations in the southern Iberian coastal Large Marine Ecosystem. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2018, 607, 19–36. [CrossRef]

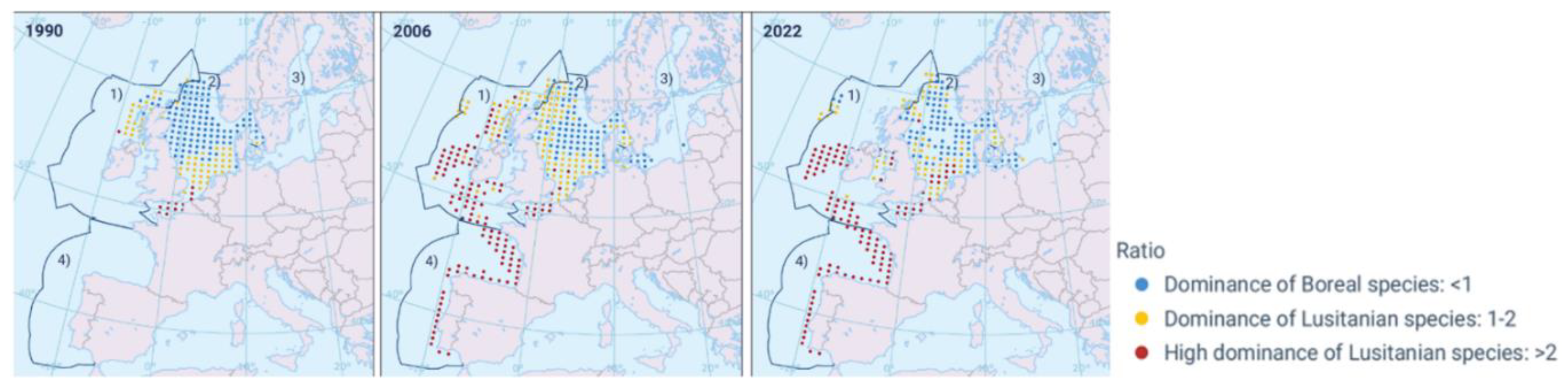

- European Environment Agency (EEA). 2024. “Changes in fish distribution in Europe’s seas” (published 16 Feb 2024): https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/indicators/changes-in-fish-distribution-in.

- https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/figures/temporal-development-of-the-ratio-1/.

- Rijnsdorp, A.D.; Peck, M.A.; Engelhard, G.H.; Möllmann, C.; Pinnegar J.K. (eds.). 2010. Resolving climate impacts on fish stocks. ICES Cooperative Research Report, 301. 371 p.

- Simpson, S.D.; Jennings, S.; Johnson, M.P.; Blanchard, J.L.; Schön, P.-J.; Sims, D.W.; Genner, M.J. Continental Shelf-Wide Response of a Fish Assemblage to Rapid Warming of the Sea. 2011, 21, 1565–1570. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.W.L.; Pinnegar, J.; Merino, G.; Jones, M.C.; Barange, M. Review of climate change impacts on marine fisheries in the UK and Ireland. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2012, 22, 368–388. [CrossRef]

- Jiming, Y. The dominant fish fauna in the North Sea and its determination. J. Fish Biol. 1982, 20, 635–643. [CrossRef]

- ter Hofstede, R.; Hiddink, J.; Rijnsdorp, A. Regional warming changes fish species richness in the eastern North Atlantic Ocean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2010, 414, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. An estimate of the fish biomass in the North Sea. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 1982, 40, 161–172. [CrossRef]

- Montero-Serra, I.; Edwards, M.; Genner, M.J. Warming shelf seas drive the subtropicalization of European pelagic fish communities. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2014, 21, 144–153. [CrossRef]

- Pinnegar, J.K.; Engelhard G.H.; Daskalov, G.M. Changes in the distribution of fish. In: Rijnsdorp A. D., Peck M. A., Engelhard G.H., Möllmann C., Pinnegar J. K. (eds.). Resolving climate impacts on fish stocks. ICES Cooperative Research Report, 2010, 301: 94-120.

- MacKenzie, B.R.; Payne, M.R.; Boje, J.; Høyer, J.L.; Siegstad, H. A cascade of warming impacts brings bluefin tuna to Greenland waters. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2014, 20, 2484–2491. [CrossRef]

- Alheit, J.; Pohlmann, T.; Casini, M.; Greve, W.; Hinrichs, R.; Mathis, M.; O’driscoll, K.; Vorberg, R.; Wagner, C. Climate variability drives anchovies and sardines into the North and Baltic Seas. Prog. Oceanogr. 2012, 96, 128–139. [CrossRef]

- Beare, D.; Burns, F.; Greig, A.; Jones, E.; Peach, K.; Kienzle, M.; McKenzie, E.; Reid, D. Long-term increases in prevalence of North Sea fishes having southern biogeographic affinities. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2004, 284, 269–278. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rubín J., 2008. Un siglo de historia oceanográfica del golfo de Vizcaya (1850-1950). Ciencia, técnica y vida en sus aguas y costas. Aquarium Donostia-San Sebastián, Spain.

- Pérez-Rubín J., 2023. 80 años de series de investigaciones periódicas del IEO en el ecosistema pelágico del estrecho de Gibraltar y mares adyacentes (1914-1995): zoología, biología, ecología y medio ambiente marino. Una revisión bibliográfica anotada. In: El estrecho de Gibraltar: llave natural entre dos mares y dos continentes (Pérez-Rubín J. & Ramírez T. (Eds.). Memorias de la Real Sociedad Española de Historia Natural, XVI: 337-383.

- Raybaud, V.; Bacha, M.; Amara, R.; Beaugrand, G. Forecasting climate-driven changes in the geographical range of the European anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus). ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2017, 74, 1288–1299. [CrossRef]

- Checkley, D.; Alheit, J.; Oozeki, Y.; Roy, C.; Csirke, J.; Glantz, M.H.; Hurrell, J.; Bakun, A.; MacCall, A.D.; Checkley, D.M.; et al. Climate Change and Small Pelagic Fish; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2001.

- Engelhard, G.H.; Peck, M.A.; Rindorf, A.; Smout, S.C.; van Deurs, M.; Raab, K.; Andersen, K.H.; et al.. Forage fish, their fisheries, and their predators: who drives whom?. ICES Journal of Marine Science: Journal Du Conseil, 2014, 71, 90–104.

- Blanchard, F.; Vandermeirsch, F. Warming and exponential abundance increase of the subtropical fish Capros aper in the Bay of Biscay (1973–2002). Comptes Rendus Biol. 2005, 328, 505–509. [CrossRef]

- Coad, J.O.; Hüssy, K.; Farrell, E.D.; Clarke, M.W. The recent population expansion of boarfish, Capros aper (Linnaeus, 1758): interactions of climate, growth and recruitment. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2014, 30, 463–471. [CrossRef]

- Egerton, S.; Culloty, S.; Whooley, J.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P. Boarfish (Capros aper): review of a new capture fishery and its valorization potential. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2017, 74, 2059–2068. [CrossRef]

- Oliver, P., Fernández, A.. Prospecciones pesqueras en la región suratlántica española. Biocenosis de la plataforma y del talud continental. Bol. Inst. Esp. Oceanor., 1974, 180: 1-31.

- Chlaida, M.; Fauvelot, C.; Ettahiri O.; Charouki, N.; Elayoubi, S. et al. Relationship between migratory behavior and environmental features revealed by genetic structure of Sardina pilchardus populations along the Moroccan Atlantic coast. Frontiers in Science and Engineering, 2021, 11 (1), 75 p. [CrossRef]

- Sambe, B.; Tandstad, M.; Caramelo, A.M.; Brown, B.E. Variations in productivity of the Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem and their effects on small pelagic fish stocks. Environ. Dev. 2016, 17, 105–117. [CrossRef]

- Malta, T.; Santos, P.; Santos, A.; Rufino, M.; Silva, A. Long-term variations in Ibero-Atlantic sardine ( Sardina pilchardus ) population dynamics: Relation to environmental conditions and exploitation history. Fish. Res. 2016, 179, 47–56. [CrossRef]

- Ba, A.; Schmidt, J.; Dème, M.; Lancker, K.; Chaboud, C.; Cury, P.; Thiao, D.; Diouf, M.; Brehmer, P. Profitability and economic drivers of small pelagic fisheries in West Africa: A twenty year perspective. Mar. Policy 2017, 76, 152–158. [CrossRef]

- Cury, P.; Fontana, A. Compétition et strategies démographiques comparées de deux espéces de sardinelles (S. aurita et S. maderensis) de cotes ouest-africaines. Aquat. Living Resour., 1988, 1, 165-180.

- Aggrey-Fynn, J. Distribution and Growth of Grey Triggerfish, Balistes capriscus (Family: Balistidae), in Western Gulf of Guinea. West Afr. J. Appl. Ecol. 2010, 15. [CrossRef]

- Bañón, R.; Pardo, P.C.; Álvarez-Salgado, X.A.; de Carlos, A.; Arronte, J.C.; Piedracoba, S. Tropicalization of fish fauna of Galician coastal waters, in the NW Iberian upwelling system. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 70. [CrossRef]

- Cury, P.; Roy, C. (eds.). 1991: Pêcheries Ouest-Africaines: Variabilité, Instabilité et Changement. ORSTOM, Paris, France, 525 p.

- Gulland, J.A., Garcia, S., 1984. Observed patterns in multispecies fisheries. In Exploitation of marine communities. In: May, R.M. (Ed.), Dahlem Konferenzen, Springler-Verlag, Berlin, 155–190.

- Binet, D.; Servain, J. Have the recent hydrological changes in the Northern Gulf of Guinea induced the Sardinella aurita outburst?. Oceanologica Acta, 1993, 16(3), 247-260.

- Asiedu, B.; Okpei, P.; Nunoo, F.K.E.; Failler, P. A fishery in distress: An analysis of the small pelagic fishery of Ghana. Mar. Policy 2021, 129, 104500. [CrossRef]

- Balguerías, E. Análisis de los descartes producidos en la pesquería española de cefalópodos del Banco Sahariano. Bol. Inst. Esp. Oceanogr., 1993, 9(1), 75-87.

- Balguerías E. The origin of the Saharan Bank cephalop fishery. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 2000, 57, 15-23.

- Caverivière, A. Étude de la pêche du poulpe (Octopus vulgaris) dans les eaux côtières de la Gambie et du Sénégal. L'explosion démographique de l'été 1986. Centre Rech. Oceanogr. Dakar-Thiaroye, Doc. Scient, 1990, 116, 1-42.

- Caverivière, A. Le poulpe (Octopus vulgaris) au Sénégal: une nouvelle ressource. In: Oiouf T. & Fonteneau A. (eds). L'évaluation des ressources exploitables par la pêche artisanale sénégalaise. Colloques et séminaires Orstom, 1994, 2, 245-256.

- Inejih, C.A.O.; Quiniou, L.; Dochi, T. Variabilite de la distribution spatio-temporelle du poulpe (octopus vulgaris) le long des côtes de Mauritanie. Bulletin Scientifique IMROP, 2002, 29, 19-38.

- Shelton, P.A.; Boyd, A.J.; Armstrong, M.J. The influence of large-scale environmental processes on neritic fish populations in the Benguela current system. Rep. Calif. Coop. Oceanic. Fish. Invest, 1985, 26, 72-92.

- Shannon, L.V.; Crawford, R.J.M.; Brundrit, G.B.; Underhill, L.G. Responses of fish populations in the Benguela ecosystem to environmental change. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 1988, 45, 5–12. [CrossRef]

- Shannon, L.V.; Tauton-Clark, J. Long-term environmental índices for the ICSEAF Area. Draganik B. (ed.). Sel. Pap. Int. Comm SE. Atl. Fish, 1989, 1, 5-15.

- https://www.ntnu.edu/museum/4-oceans.

- https://pastglobalchanges.org/science/wg/q-mare/intro.

- Lehodey, P.; Alheit, J.; Barange, M.; Baumgartner, T.; Beaugrand, G.; Drinkwater, K.; Fromentin, J.-M.; Hare, S.R.; Ottersen, G.; Perry, R.I.; et al. Climate Variability, Fish, and Fisheries. J. Clim. 2006, 19, 5009–5030. [CrossRef]

- Bograd, S.J.; Edwards, M.; Ito, S.; Nye, J.; Chappell, E. Fisheries Oceanography: The first 30 years and new challenges in the 21st century. Fish. Oceanogr. 2022, 32, 3–9. [CrossRef]

- Cacho, I.; Valero-Garcés, B.; González-Sampériz, P. Review of paleoclimate reconstructions in the Iberian Peninsula since the last glacial period. Report: Climate in Spain: Past, present and future.: Pérez, F.F.; Boscolo, R.; Eds.; 2010, 9-24.

- Real, R.; Gofas, S.; Altamirano, Mª.; Salas, C.; Báez, J.C.; Camiñas, J. A.; García-Raso, J. E.; Gil de Sola, L.; Olivero, J.; Reina-Hervás, J. A.; et al. Biogeographical and macroecological context of the Alboran Sea. In: Alboran sea-ecosystems and marine resources. Springer International Publishing, 2021, 431-457.

- Gómez, F. Endemic and Indo-Pacific plankton in the Mediterranean Sea: a study based on dinoflagellate records. J. Biogeogr. 2005, 33, 261–270. [CrossRef]

- Würtz, M. Mediterranean pelagic habitat: oceanographic and biological processes. An overview. 2010. UNCN, Malaga, Spain.

- Zazo, C.; Goy, J.L.; Dabrio, C.J.; Lario, J.; González-Delgado, J.A.; Bardají, T.; Hillaire-Marcel, C.; Cabero, A.; Ghaleb, B.; Borja, F.; et al. Retracing the Quaternary history of sea-level changes in the Spanish Mediterranean-Atlantic coasts: Geomorphological and sedimentological approach. Geomorphology, 2013, 196, 36-49. [CrossRef]

- Zazo, C.; Cendrero, A. Explorando las costas de un pasado reciente: los cambios del nivel del mar. Real Academia de Ciencias (Madrid). 2015, Discursos, 253, 1-112.

- Herbig, H. G.; Mamet, B. L. Stratigraphy of the limestone boulders, Marbella Formation Betic Cordillera, Southern Spain. In: Compte Rendu 10 Congrès International de Stratigraphie du Carbonifère, Madrid, 1985, 1, 199-212.

- Somerville, I.D.; Rodríguez, S. Rugose coral associations from the late Visean Carboniferous of Ireland and SW Spain. In: Fossil Corals and Sponges. Hubmann, B.; Piller, W.E. Eds.; Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Schriftenreihe der Erdwissenschaftlichen Kommissionen, 2007, 17, 329-351.

- Morales, A.; Rosello, E.; Cañas, J.M. Cueva de Nerja (Málaga), a close look at a twelve thousand year ichthyofaunal sequence from southern Spain. Annales du Musée Royal de l’Afrique centrale. Zool Sci, 1994, 274, 253-264.

- Morales-Muñiz, A. Twenty Thousand Years of Fishing in the Strait. Archaeological Fish and Shellfish assemblages from southern Iberia. In: Human Impacts on Ancient Marine Ecosystems: A Global Perspective. Torben C.; Erlandson, J. Ed. 2008. University of California Press.

- Jordá, J.; Maestro, A.; Aura, E.; Álvarez, E.; Avezuela, B.; Badal, E.; Morales, J.V.; Pérez, M.; Villalba, M.P. Evolución paleogeográfica, paleoclimática y paleoambiental de la costa meridional de la Península Ibérica durante el Pleistoceno superior. El caso de la Cueva de Nerja (Málaga, Andalucía, España). Bol. R. Soc. Esp. Hist. Nat. 2011, 105 (1-4), 137-147.

- Álvarez-Fernández, E.; Carriol, R.-P.; Jordá, J.F.; Aura, J.E.; Avezuela, B.; Badal, E.; Carrión, Y.; García-Guinea, J.; Maestro, A.; Morales, J.V.; et al. Occurrence of whale barnacles in Nerja Cave (Málaga, southern Spain): Indirect evidence of whale consumption by humans in the Upper Magdalenian. Quat. Int. 2014, 337, 163–169. [CrossRef]

- Cacho, I.; Grimalt, J.O.; Canals, M.; Sbaffi, L.; Shackleton, N.J.; Schönfeld, J.; Zahn, R. Variability of the western Mediterranean Sea surface temperature during the last 25,000 years and its connection with the Northern Hemisphere climatic changes. Paleoceanogr. 2001, 16, 40–52. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; Cacho, I.; Canals, M.; Grimalt, J.O.; Sánchez-Goñi, M.F.; Shackleton, N.; Sierro, F.J. Links between marine and atmospheric processes oscillating on a millennial time-scale. A multi-proxy study of the last 50,000yr from the Alboran Sea (Western Mediterranean Sea). Quat. Sci. Rev. 2005, 24, 1623–1636. [CrossRef]

- González-Mora, B.; Sierro, F.J.; Flores, J.A. Study of paleotemperatures in the Alboran Sea between 250 and 150 kyr with the modern analog technique. Geogaceta, 2006, 40, 219-222.

- Degroot, D. Climate change and society in the 15th to 18th centuries. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Holm, P.; Ludlow, F.; Scherer, C.; Travis, C.; Allaire, B.; Brito, C.; Hayes, P.W.; Al Matthews, J.; Rankin, K.J.; Breen, R.J.; et al. The North Atlantic Fish Revolution (ca. AD 1500). Quat. Res. 2019, 108, 92–106. [CrossRef]

- Edvardsson, R.; Patterson, W.P.; Bárðarson, H.; Timsic, S.; Ólafsdóttir, G.. Change in Atlantic cod migrations and adaptability of early land-based fishers to severe climate variation in the North Atlantic. Quat. Res. 2019, 108, 81–91. [CrossRef]

- Moullec, F.; Veleza, L.; Verley, P.; Barrier, N.; Ulses, C.; Carbonara, P.; Esteban, A.; Follesa, C.; Gristina, M.; Jadaud, A.; Ligas A.; López Díaz E.; Maiorano P.; Peristeraki P.; Spedicato Mª. T.; Thasitis I.; Valls, Mª.; Guilhaumon, F.; Shin, Y-J. Catching the big picture of the Mediterranean Sea biodiversity with an end-to-end model of climate and fishing impacts. BioRxiv. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Popova, E.; Yool, A.; Byfield, V.; Cochrane, K.; Coward, A.C.; Salim, S.S.; Gasalla, M.A.; Henson, S.A.; Hobday, A.J.; Pecl, G.T.; et al. From global to regional and back again: common climate stressors of marine ecosystems relevant for adaptation across five ocean warming hotspots. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016, 22, 2038–2053. [CrossRef]

- Arístegui, J.; Barton, E.D.; Álvarez-Salgado, X.A.; Santos, A.M.P.; Figueiras, F.G.; Kifani, S.; Hernández-León, S.; Mason, E.; Machú, E.; Demarcq, H. Sub-regional ecosystem variability in the Canary Current upwelling. Progress in Oceanography 2009, 83, 33–48. [CrossRef]

- Gallego, D.; García-Herrera, R.; Losada, T.; Mohino, E.; de Fonseca, B.R. A Shift in the Wind Regime of the Southern End of the Canary Upwelling System at the Turn of the 20th Century. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2021, 126. [CrossRef]

- Gallego, D.; García-Herrera, R.; Mohino, E.; Losada, T.; Rodríguez-Fonseca, B. Secular Variability of the Upwelling at the Canaries Latitude: An Instrumental Approach. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 2022, 127. [CrossRef]

- Rosselló, P.; Pascual, A.; Combes, V. Assessing marine heat waves in the Mediterranean Sea: a comparison of fixed and moving baseline methods. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1168368. [CrossRef]

- Kodra, E.; Steinhaeuser, K.; Ganguly, A.R. Persisting cold extremes under 21st-century warming scenarios. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38. [CrossRef]

- Rollefsen & Tåning, 1948. Inquiry into the Problem of Climatic and Ecological Changes in Northern Waters. (mimeographed).

- McLean, M.; Mouillot, D.; Maureaud, A.A.; Hattab, T.; MacNeil, M.A.; Goberville, E.; Lindegren, M.; Engelhard, G.; Pinsky, M.; Auber, A. Disentangling tropicalization and deborealization in marine ecosystems under climate change. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, 4817–4823.e5. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.W.L.; Watson, R.; Pauly, D. Signature of ocean warming in global fisheries catch. Nature 2013, 497, 365–368. [CrossRef]

- Chust, G.; Villarino, E.; McLean, M.; Mieszkowska, N.; Benedetti-Cecchi, L.; Bulleri, F.; Ravaglioli, C.; Borja, A.; Muxika, I.; Fernandes-Salvador, J.A.; et al. Cross-basin and cross-taxa patterns of marine community tropicalization and deborealization in warming European seas. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Garrido, J.; Werner, F.; Fiechter, J.; Rose, K.; Curchitser, E.; Ramos, A.; Lafuente, J.G.; Arístegui, J.; Hernández-León, S.; Santana, A.R.; et al. Decadal-scale variability of sardine and anchovy simulated with an end-to-end coupled model of the Canary Current ecosystem. Prog. Oceanogr. 2018, 171, 212–230. [CrossRef]

- Derhy, G.; Macías, D.; Elkalay, K.; Khalil, K.; Rincón, M.M. Stochastic Modelling to Assess External Environmental Drivers of Atlantic Chub Mackerel Population Dynamics. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9211. [CrossRef]

- Townhill, B.L.; Couce, E.; Tinker, J.; Kay, S.; Pinnegar, J.K. Climate change projections of commercial fish distribution and suitable habitat around north western Europe. Fish Fish. 2023, 24, 848–862. [CrossRef]

- Allison, E.H.; Perry, A.L.; Badjeck, M.; Adger, W.N.; Brown, K.; Conway, D.; Halls, A.S.; Pilling, G.M.; Reynolds, J.D.; Andrew, N.L.; et al. Vulnerability of national economies to the impacts of climate change on fisheries. Fish Fish. 2009, 10, 173–196. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.W.L.; Pinnegar, J.; Merino, G.; Jones, M.C.; Barange, M. Review of climate change impacts on marine fisheries in the UK and Ireland. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2012, 22, 368–388. [CrossRef]

- Raybaud, V.; Bacha, M.; Amara, R.; Beaugrand, G. Forecasting climate-driven changes in the geographical range of the European anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus). ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2017, 74, 1288–1299. [CrossRef]

- Erauskin-Extramiana, M.; Alvarez, P.; Arrizabalaga, H.; Ibaibarriaga, L.; Uriarte, A.; Cotano, U.; Santos, M.; Ferrer, L.; Cabré, A.; Irigoien, X.; et al. Historical trends and future distribution of anchovy spawning in the Bay of Biscay. Deep. Sea Res. Part II: Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2018, 159, 169–182. [CrossRef]

- Townhill, B.L.; Couce, E.; Tinker, J.; Kay, S.; Pinnegar, J.K. Climate change projections of commercial fish distribution and suitable habitat around north western Europe. Fish Fish. 2023, 24, 848–862. [CrossRef]

- Failler, P. Fisheries of the Canary Current Large Marine Ecosystem: From capture to trade with a consideration of migratory fisheries. Environ. Dev. 2020, 36, 100573. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).