Submitted:

28 November 2024

Posted:

29 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

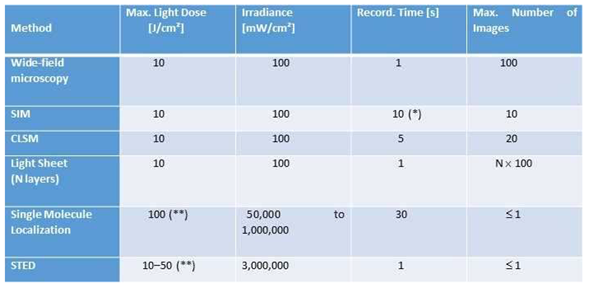

Light microscopy has emerged as one of the fundamental methods to analyze biological systems; novel techniques of 3D microscopy and super-resolution microscopy (SRM) with an optical resolution down to the sub-nanometer range have recently been realized. However, most of these achievements have been made with fixed specimens, i.e. direct information about the dynamics of the biosystem studied was not possible. This stimulated the development of live cell microscopy imaging approaches including Low Illumination Fluorescence Microscopy, Light Sheet Microscopy (LSM), or Structured Illumination Microscopy (SIM). Here we discuss perspectives, methods and relevant light doses of advanced fluorescence microscopy imaging to keep the cells alive at low levels of phototoxicity.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Whole Cell Illumination

2.1. Mechanisms involved

2.2. Microscopy methods and their compatibility with low light exposure

2.2.1. General

2.2.2. Super-resolution microscopy

3. Focused Illumination

3.1. Visible irradiation

3.2. UV irradiation

4. Discussion and Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cadet, J.; Berger, M.; Douki, T.; Morin, B.; Raoul, S.; Ravanat, J.L.; Spinelli, S. Effects of UV and visible radiation on DNA-final base damage. Biol. Chem. 1997, 378, 1275–1286. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nakanishi, M.; Niida, H.; Murakami, H.; Shimada, M. DNA damage responses in skin biology − implications in tumor prevention and aging acceleration. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2009, 56, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richa; Sinha, R.P.; Häder, D.P. Physiological aspects of UV-excitation of DNA. Top. Curr. Chem. 2015, 356, 203–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneckenburger, H.; Richter, V.; Wagner, M. Live-cell optical microscopy with limited light doses. SPIE Spotlight Series, Vol. SL 42, 2018, 38 pages, ISBN: 9781510622593.

- Berns, M.W. A history of laser scissors (microbeams). Methods Cell Biol. 2007, 82, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkin, A. Optical trapping and manipulation of neutral particles using lasers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 4853–4860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greulich, K.O. Micromanipulation by light in biology and medicine: the laser microbeam and optical tweezers. Birkhäuser, Basel-Boston-Berlin, 1999.

- Scott, T.G.; Spencer, R.G.; Leonard, N.J.; Weber, G. Emission properties of NADH. Studies of fluorescence lifetimes and quantum efficiencies of NADH, AcPyADH and simplified synthetic models. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 687–695. [Google Scholar]

- Galland, P.; Senger, H. The role of flavins as photoreceptors. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 1988, 1, 277–294. [Google Scholar]

- Ormond, A.B.; Freeman, H.S. Dye Sensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. Materials (Basel) 2013, 6, 817–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

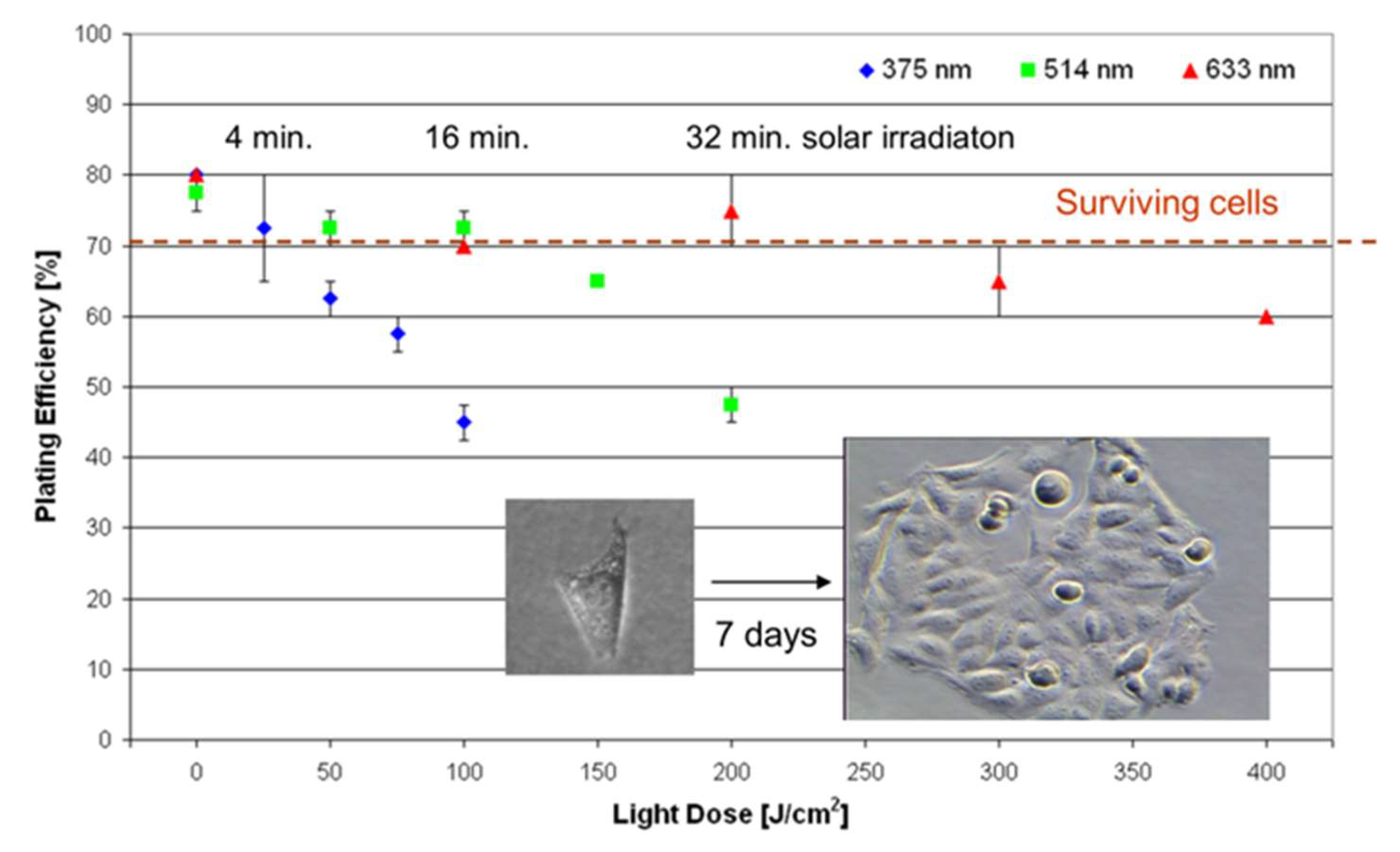

- Schneckenburger, H.; Weber, P.; Wagner, M.; Schickinger, S.; Richter, V.; Bruns, T.; Strauss, W.S.; Wittig, R. Light exposure and cell viability in fluorescence microscopy. J. Microsc. 2012, 245, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkman, J.; Brown, C.M.; Wright, G.D.; Anderson, K.I.; North, A.J. Tutorial: guidance for quantitative confocal microscopy. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 1585–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenberg, M. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2014 (Press Release). http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_ prizes/chemistry/laureates/2014/advanced-chemistryprize2014.pdf.

- Masters, B.R. 1996. Selected Papers on Confocal Microscopy, SPIE Milestone Series, volume MS 131, SPIE Optical Engineering Press, Bellingham.

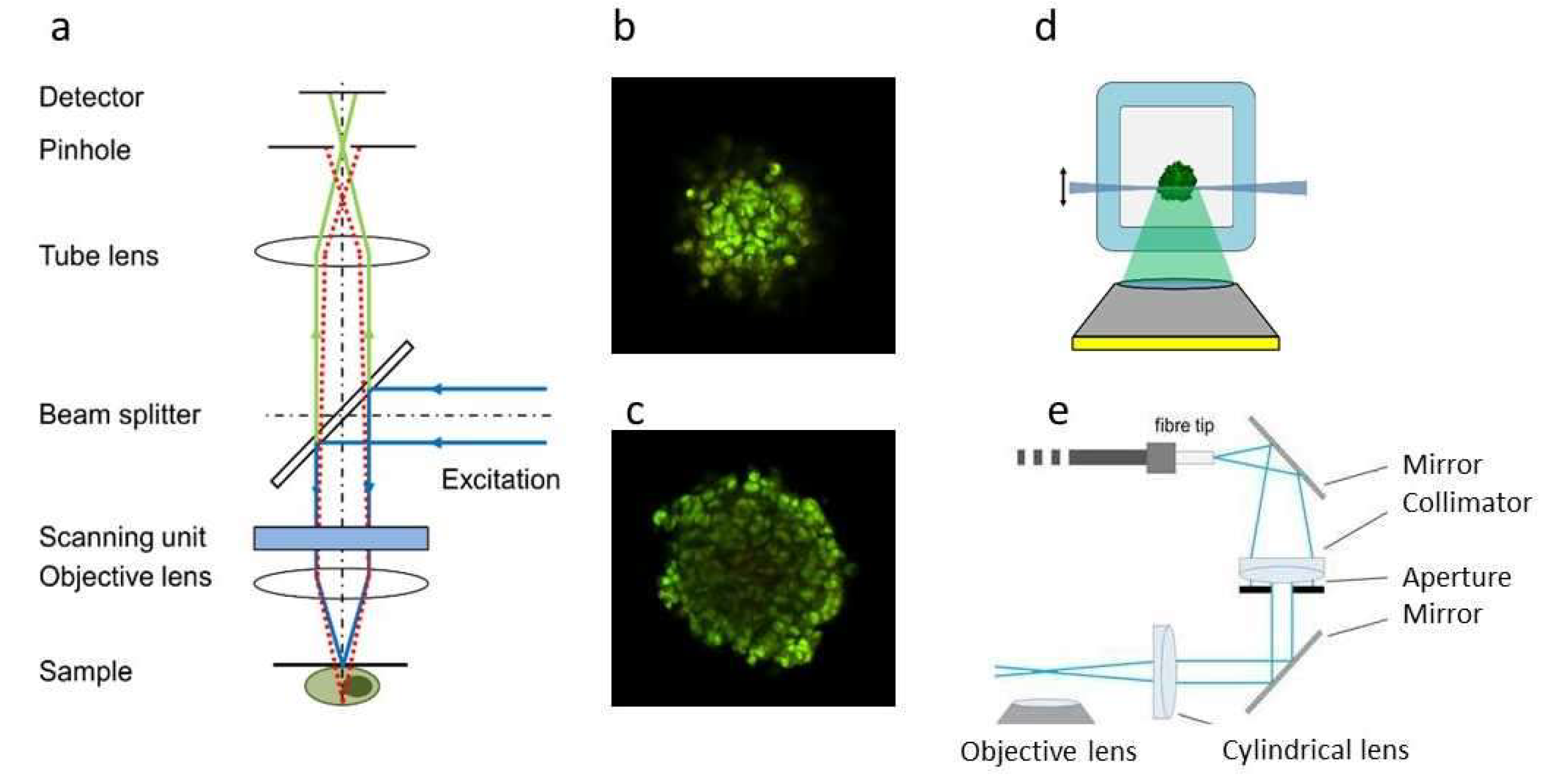

- Huisken, J.; Swoger, J.; del Bene, F.; Wittbrodt, J.; Stelzer, E.H.K. Optical sectioning deep inside live embryos by SPIM. Science 2004, 305, 1007–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santi, P.A. Light sheet fluorescence microscopy: a review. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2011, 59, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pampaloni, F.; Chang, B.-J.; Stelzer, E.H.K. Light sheet-based fluorescence microscopy (LSFM) for the quantitative imaging of cells and tissues. Cell Tissue Res. 2015, 360, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruns, T.; Schickinger, S.; Schneckenburger, H. Single plane illumination module and micro-capillary approach for a wide-field microscope. J. Vis. Exp. 2014, 15, e51993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbe, E. Beiträge zur Theorie des Mikroskops und der mikroskopischen Wahrnehmung. Arch. Mikrosk. Anat. 1873, 9, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayleigh, L. On the Theory of Optical Images, with Special Reference to the microscope. 1896. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science 42, Part XV, 1896, pp. 167−195.

- Wu, X.; Hammer, J.A. ZEISS Airyscan: Optimizing Usage for Fast, Gentle, Super-Resolution Imaging. Methods Mol. Biol. 2021, 2304, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisshart, K. The Basic Principle of Airyscanning. Carl Zeiss, 2014. https://pages.zeiss.com/rs/896-XMS-794/images/ZEISS-Microscopy.

- Müller, C.B.; Enderlein, J. Image Scanning Microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 198101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, C.; Masters, B.R. Resolution enhancement techniques in microscopy. Eur. Phys. J. H 2013, 38, 281–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sydor, A.M.; Czymmek, K.J.; Puchner, E.M.; Mennella, V. Super-resolution microscopy: from single molecules to supramolecular assemblies. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25, 730–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, C.G.; Galbraith, J.A. Super-resolution microscopy at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2011, 124, 1607–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toraldo di Francia, G. Resolving power and information. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1955, 45, 497–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S. Super-resolution imaging in live cells. Dev. Biol. 2015, 40, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremer, C.; Kaufmann, R.; Gunkel, M.; Pres, S.; Weiland, Y.; Müller, P.; et al. Superresolution imaging of biological nanostructures by spectral precision distance microscopy. Biotechnol. J. 2011, 6, 1037–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shtengel, G.; Galbraith, J.A.; Galbraith, C.G.; J. Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Gillette, J.M.; ManleyS.; et al. Interferometric fluorescent super-resolution microscopy resolves 3D cellular ultrastructure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birk, U. Super-Resolution Microscopy-A Practical Guide. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim/Germany, 2017. ISBN: 978-3-527-34133-7.

- Heintzmann, R. Answers to fundamental questions in superresolution microscopy. Phil. Trans. R.Soc. A 2021, 379, 20210105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermelleh, L.; Ferrand, A.; Huser, T.; Eggeling, C.; Sauer, M.; Biehlmaier, O.; Drummen, G. P. C. Super-resolution microscopy demystified. Nature Cell Biology 2019, 2, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornasiero, E. F.; Opazo, F. Super-resolution imaging for cell biologists: Concepts, applications, current challenges and developments. Bioessays 2015, 37, 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, M.G.; Shao, L.; Carlton, P.M.; Wang, C.J.R.; Golubovskaya, I.N.; Cande, W.Z.; Agard, D.A.; Sedat, J.W. Three-Dimensional Resolution Doubling in Wide-Field Fluorescence Microscopy by Structured Illumination. Biophys. J. 2008, 94, 4957–4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirvonen, L.M.; Wicker, K.; Mandula, O.; Heintzmann, R. Structured illumination microscopy of a living cell. Eur. Biophys. J. 2009, 38, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

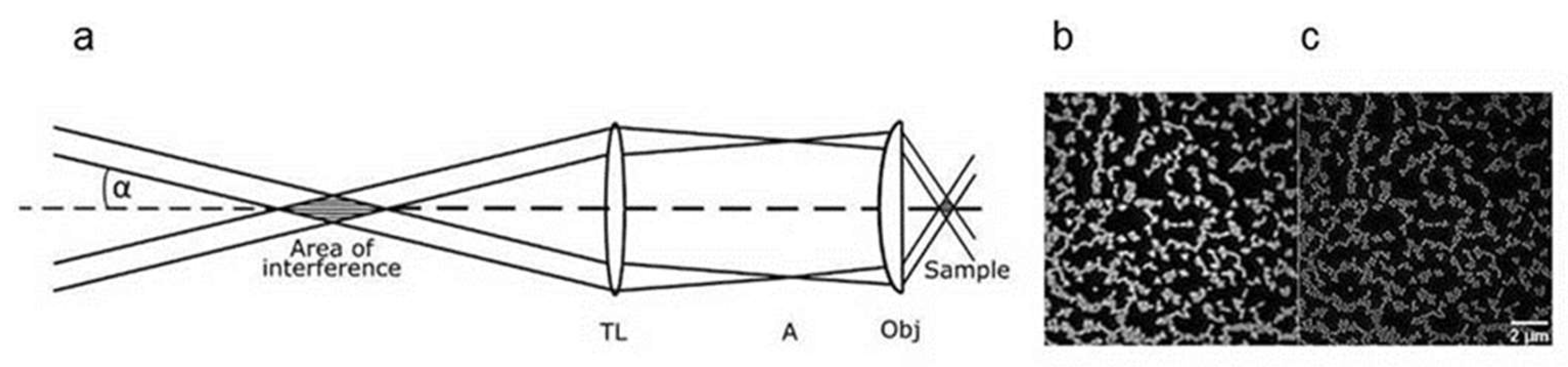

- Heintzmann, R.; Cremer, C. Lateral modulated excitation microscopy: Improvement of resolution by using a diffraction grating. Proc. SPIE 1999, 3568, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schock, F.; Best, G.; Celik, N.; Heintzmann, R.; Dithmar, S.; Cremer, C. Structured illumination ophthalmoscope: super-resolution microscopy on the living human eye. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 2022, 380, 20210151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.R.; Ross, S.T.; Davidson, M.W. Structured illumination microscopy for superresolution. Chem. Phys. Chem.. 2014, 15, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrova, N.; Heintzmann, R.; Rieger, B.; Stallinga, S. Studying different illumination patterns for resolution improvement influorescence microscopy. Opt Exp. 2015, 23, 31367–31383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Shao, L.; Chen, B.-C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, M.; Moses, B.; et al. Extended resolution structured illumination imaging of endocytic and cytoskeletal dynamics. Science 2015, 349, aab3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, M.G.L. Nonlinear structured-illumination microscopy: wide-field fluorescence imaging with theoretically unlimited resolution. Proc Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 102,13081–13086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heintzmann, R.; Huser, T. Super-resolution structured illumination microscopy. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 13890–13908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, M. G. L. Surpassing the lateral resolution limit by a factor of two using structured illumination microscopy. J. Microsc. 2000, 198, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, F.; Miron, E.; 2, Demmerle, J.; Chitiashvili, T.; Budco, A.; Alle, Q. et al. Quantitative 3D structured illumination microscopy of nuclear structures. Nature Protocols 2017, 12, 1011–1027. [CrossRef]

- Schneckenburger, H. Lasers in Live Cell Microscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supekar, O.D.; Sias, A.; Hansen, S.R.; MartinezG.; Peet, G.C.; Peng, X. et al. Miniature structured illumination microscope for in vivo 3D imaging of brain structures with optical sectioning. Biomed. Opt. Exp. 2022, 13, 2531. [CrossRef]

- Löschberger, A.; Novikau, Y.; Netz, R.; Kleppe, I.; Spindler, M.-C.; Benavente, R.; et al. Super-Resolution Imaging by dual iterative structured illumination microscopy, Carl Zeiss, 2017. https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/en/products/light-microscopes/super-resolution-microscopes/elyra-7.html?

- Wang, F.; Ma, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Salazar, F.; Xu, C.; Ren, F.; et al. In vivo NIR-II structured-illumination light-sheet microscopy. Proc Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2021, No. 6, No. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 15004-2:2007: Ophthalmic instruments — Fundamental requirements and test methods, Part 2: Light hazard protection. International Organization for Standardization 2019. https://www.iso.org/standard/38952.html.

- Fischer, J.; Otto, T.; Delori, F.; Pace, L.; Staurenghi, G. Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscopy (SLO). In: High Resolution Imaging in Microscopy and Ophthalmology. New Frontiers in Biomedical Optics (Bille JF, editor), Springer 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554043/.

- Cremer, C.; Schock, F.; Failla, A.V.; Birk, U. Modulated illumination microscopy: Application perspectives in nuclear nanostructure analysis. J. Microsc. 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanni, F.; Bailey, B.; Farkas, D.L.; Taylor, D.L. Excitation field synthesis as a means for obtaining enhanced axial resolution in fluorescence microscopes. Bioimaging 1993, 1, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohn, J.; Knapp, H.; Stemmer, A. True optical resolution beyond the Rayleigh limit achieved by standing wave illumination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 7232–7236. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey; B.; Farkas, D.; Taylor, D.L.; Lanni, F. Enhancement of axial resolution in fluorescence microscopy by standing-wave excitation. Nature 1993, 366, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Reymann, J.; Baddeley, D.; Gunkel, M.; Lemmer, P.; Stadter, W.; Jegou, T.; et al. High precision structural analysis of subnuclear complexes in fixed and live cells via spatially modulated illumination (SMI) microscopy. Chromosome Res. 2008, 16, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, S.C.M.; Masullo, L.A.; Baudrexel, I.; Stehen, Ph.R.; Kowalewski, K.; Eklund, A.S.; et al. Ångström-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Nature 2023, 617, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betzig, E.; Patterson, G.H.; Sougrat, R.; Lindwasser, O.W.; Olenych, S.; Bonifacino, J.S.; Davidson, M.W.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Hess, H.F. Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. Science 2006, 313, 1642–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, M.J.; Bates, M.; Zhuang, X. Sub-diffraction-limit imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM). Nat. Methods 2006, 3, 793–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, S.T.; Girirajan, T.P.; Mason, M.D. Ultra-High Resolution Imaging by Fluorescence Photoactivation Localization Microscopy. Biophys. J. 2006, 91, 4258–4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, S.; Rosten, E.; Monypenny, J.; Jovanovic-Talisman, T.; Burnette, D.T.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; E Jones, G.; Heintzmann, R. Bayesian localization microscopy reveals nanoscale podosome dynamics. Nat. Methods 2011, 9, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, T. Single-molecule methods leap ahead. Nature Methods 2014, 11, 1015–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremer, C.; Szczurek, A.; Schock, F.; Gourram, A.; Birk, U. Super-resolution microscopy approaches to nuclear nanostructure imaging. Methods 2017, 123, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelléri, M.; Chen, S.-Y.; Hübner, B.; Neumann, J.; Kröger, O.; Sadlo, F.; et al. True-to-scale DNA-density maps correlate with major accessibility differences between active and inactive chromatin. Cell Reports 2023, 42, 112567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reck-Peterson, S.L.; Derr, N.D.; Stuurman, N. Imaging single molecules using total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy (TIRFM). Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2010, pdb.top73. [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; He, K.; Xia, T.; Fang, X. Single-molecule monitoring in living cells by use of fluorescence microscopy. Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2013, 405, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, J.G.; Veith, R.; Veenendaal, A.; Siebrasse, J.P.; Kubitscheck, U. Light Sheet Microscopy for Single Molecule Tracking in Living Tissue. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barentine, A.E.S.; Lin, Y.; Courvan, E.M.; Kidd., Ph.; Liu, M.; Balduf, L.; et al. An integrated platform for high-throughput nanoscopy. Nature Biotechnology 2023, 41, 1549–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakadamyali, M. Super-Resolution Microscopy: Going Live and Going Fast. Chem. Phys. Chem. 2014, 15, 630–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wombacher, R.; Heidbreder, M.; van de Linde, S.; Sheetz, M.P.; Heilemann, M.; Cornish, V.W.; Sauer, M. Live-cell super-resolution imaging with trimethoprim conjugates. Nature Methods 2010, 7, 717–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.-H.; Xi, C.; Zhonga, G.; Babcocka, H.P.; Vaughana, J.C.; Huanga, B.; Wang, X.; et al. Super-resolution fluorescence imaging of organelles in live cells with photoswitchable membrane probes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 13978–13983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanacchi, F.C.; Lavagnino, Z.; Donnorso, M. P.; Del Bue, A.; Furia, L.; Faretta, M.; Diaspro, A. Live-cell 3D superresolution imaging in thick biological samples. Nature Methods 2017, 8, 1047–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hell, S.W.; Wichmann, J. Breaking the diffraction resolution limit by stimulated emission: stimulated-emission-depletion fluorescence microscopy. Opt. Lett. 1994, 19, 780–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wildanger, D.; Medda, R.; Kastrup, L.; Hell, S. A compact STED microscope providing 3D nanoscale resolution. J. Microsc. 2009, 236, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blom, H.; Widengren, J. STED microscopy—towards broadened use and scope of applications. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2014, 20, 127–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, M.; Eggeling, C.; Jakobs, S.; Hell, S.W. Breaking the diffraction barrier in fluorescence microscopy at low light intensities by using reversibly photoswitchable proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 17565−17569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hell, S.W. Microscopy and its focal switch. Nature Methods 2009, 6, 24−32. [CrossRef]

- Chmyrov, A.; Keller, J.; Grotjohann, T.; Ratz, M.; d’Este, E., Jakobs, S. et al. Nanoscopy with more than 100,000 ‘Doughnuts.’ Nature Methods 2013, 10, 737–40. [CrossRef]

- Rittweger, E., Han, K.Y.; Irvine, S.E.; Eggeling, C.; Hell. S.W. STED microscopy reveals crystal colour centres with nanometric resolution. Nature Photonics 2009, 3, 144147.

- Weber, M.; Leutenegger, M.; Stoldt, S.; Jakobs, S.; Mihaila, T.S.; Butkevich, A.N.; Hell, S.W. MINSTED fluorescence localization and nanoscopy. Nature Photonics 2021, 15, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, V.; Rizzoli, S.O.; Lauterbach, M.A.; Kamin, D.; Jahn, R.; Hell, S.W. Video-Rate far-field optical nanoscopy dissects synaptic vesicle movement. Science 2008, 320, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai Tai® One Box Ti:Sapphire Ultrafast Lasers. Spectra Physic,. 2014. https://www.spectra-physics.com/en/f/mai-tai-ultrafast-laser.

- Balzarotti, F.; Eilers, Y.; Gwosch, K.C.; Gynnå, A.H.; Westphal, V.; Stefani, F.D.; Elf, J.; Hell, S.W. Nanometer resolution imaging and tracking of fluorescent molecules with minimal photon fluxes. Science 2016, 355, 606–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gwosch, K. C.; Pape, C.; Balzarotti, J.K.; Hoess, F.; Ellenberg, P.; Ries, J.; Hell, S. W. MINFLUX nanoscopy delivers 3D multicolor nanometer resolution in cells. Nature Methods 2020, 17, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahl, S. J.; Matthias, J.; Inamdar, K.; Weber, M.; Khan, T. A.; Brüser, C.; Jakobs, S.; Becker, S.; Griesinger, C.; Broichhagen, J.; Hell, S.W. Direct optical measuerement of intramolecular distances with Angström precision. Science 2024, 386, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonkman, J.; Brown, C.M.; Wright, G.D.; Anderson, K.I.; North, A.J. Tutorial: guidance for quantitative confocal microscopy. Nature Protocols 2020, 1585–1611. https://www.nature.com/nprot.

- Huang, B.; Wang, W.; Bates, M.; Zhuang, X. Three-dimensional super-resolution imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy. Science 2008, 319, 810–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heilemann, M.; van de Linde, S.; Schüttpelz, M.; Kasper, R.; Seefeldt, B.; Mukherjee, A.; et al. Subdiffraction-resolution fluorescence imaging with conventional fluorescent probes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 6172–6176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmer, P.; Gunkel, M.; Baddeley, D.; et al. SPDM: light microscopy with single-molecule resolution at the nanoscale. Appl. Phys. B 2008, 93, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Jones, S.A.; Brandenburg, B.; Zhuang, X. Whole-cell 3D STORM reveals interactions between cellular structures with nanometer-scale resolution. Nature Methods 2008, 5, 1047–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, M.A.; Manzo, C.; Garcıa-Parajo, M.F.; Lakadamyali, M.; Cosma, M.P. Chromatin fibers are formed by heterogeneous groups of nucleosomes in vivo. Cell 2015, 160, 1145–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneckenburger, H. Laser-assisted optoporation of cells and tissues − a mini-review. Biomed. Opt Express 2019, 10, 2883–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Vu, K.T.; Krishnan, P.; Trang, T.C.; Shin, D; Kimel, S.; Berns, M.W. Wavelength dependence of cell cloning efficiency after optical trapping. Biophys. J. 1996, 70, 1529−1533. [CrossRef]

- Schneckenburger, H.; Hendinger, A.; Sailer, R.; Gschwend, M.H.; Strauss, W.S.; Bauer, M.; Schütze, K. Cell viability in optical tweezers: high power red laser diode versus Nd:YAG laser. J. Biomed. Opt. 2000, 5, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greulich, K.O. Manipulation of cells with laser microbeam scissors and optical tweezers: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2017, 80, 026601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalili, A.A.; Ahmad, A.R. A Review of Cell Adhesion Studies for Biomedical and Biological Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 18149–18184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.; Kim, J.; Yoon, S.H. A Review on Quantitative Measurement of Cell Adhesion Strength. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2016, 16, 4256–4273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Arbore, C.; Perego, L.; Sergides, M.; Capitanio, M. Probing force in living cells with optical tweezers: from single-molecule mechanics to cell mechanotransduction. Biophys. Rev. [CrossRef]

- Musielak, M. Red blood cell-deformability measurement: review of techniques, Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2009, 42, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priezzhev, A.; Lee, K. Potentialities of laser trapping and manipulation of blood cells in hemorheologic research. Clin. Hemorheol. Microcirc. 2016, 64, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arai, F.; Ng, C.; Maruyama, H.; Ichikawa, A.; El-Shimy, H.; Fukuda, T. On chip single-cell separation and immobilization using optical tweezers and thermo-sensitive hydrogel. Lab Chip 2005, 5, 1399–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Kong, M.; Wang, Z.; Costa, K.D.; Li, R.A.; Sun, D. Enhanced cell sorting and manipulation with combined optical tweezer and microfluidic chip technologies. Lab Chip 2011, 11, 3656–3662. [CrossRef]

- Kaschke, M.; Donnerhacke, K.-H.; Rill, M.S. Optical Devices in Ophthalmology and Optometry: Technology, Design Principles, and Clinical Applications, 2014, Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Szczurek, A.T.; Dimitrova, E.; Kelley, J.R.; et al. The Polycomb system sustains promoters in a deep OFF state by limiting pre-initiation complex formation to counteract transcription. Nature Cell Biol. 2024, 26, 1700–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peker, B.; Rausch, M. Microscopy of Organoids. Breakthrough in live cell microscopy of 3D cellular models. Microscopy and Analysis 2020, 34, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cremer, C.; Cremer, T.; Zorn, C.; Schoeller, L. Effects of laser-uv-microirradiation (λ = 257 nm) on proliferation of Chinese hamster cells. Radiat. Res. 1976, 66, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremer, C.; Cremer, T.; Fukuda, M.; Nakanishi, K. Detection of Laser-uv-microirradiation induced DNA photolesions by immunofluorescent staining. Hum. Genet. 1980, 54, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorn, C.; Cremer, T.; Cremer, C.; Zimmer, J. Laser-uv-micro-irradiation of interphase nuclei and posttreatment with caffeine: A new approach to establish the arrangement of interphase chromosomes. Hum. Genet. 1976, 35, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cremer, C.; Cremer, T.; Jabbur, G. Laser-uv-microirradiation of Chinese hamster cells: The influence of the distribution of photolesions on unscheduled DNA synthesis. Photochem. Photobiol. 1981, 33, 925–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohs-Schardin, M.; Sander ,K.; Cremer, C.; Cremer, T.; Zorn, C. Localized ultraviolet laser microbeam irradiation of early Drosophila embryos: Fate maps based on location and frequency of adult defects. Develop. Biol. 1979, 68, 533–545. [CrossRef]

- Nüsslein-Volhard, Ch. üsslein-Volhard, Ch.; M. Lohs-Schardin, M.; K. Sander, K.; C. Cremer, C. A dorso-ventral shift of embryonic primordia in a new maternal-effect mutant of Drosophila. Nature 1980, 283, 474–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höh, A.E.; Ach, T.; Amberger, R.; Dithmar, S. Lichtexposition bei vitreoretinaler Chirurgie. Ophthalmologe 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antonie_van_Leeuwenhoek.

- Zernike, F. Das Phasenkontrastverfahren bei der mikroskopischen Beobachtung. Phys. Zeitschr. 1935, 36, 848–851. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, K.; McWhir, J.; Ritchie, W.; et al. Sheep cloned by nuclear transfer from a cultured cell line. Nature 1996, 380, 64–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmut, I;, Schnieke, A.; McWhir, J. et al. Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells. Nature 1997, 385, 810–813. [CrossRef]

- Hoebe, R.A.; Van der Voort, H.T.; Stap, J.; Van Noorden, C.J.; Manders, E.M. Quantitative determination of the reduction of phototoxicity and photobleaching by controlled light exposure microscopy. J Microsc. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, H.; et al. Intrinsic Burst-Blinking Nanographenes for Super-Resolution Bioimaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 5195–5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).