Introduction to the Hypothesis

The famous architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris (1887-1965), better known as Le Corbusier. The famous quote is: "La maison est une machine à habiter" (The house is a machine for living in). This quote is taken from the book "Vers une architecture", published in 1923.

This paper argues that this idea or concept is not original to Le Corbusier, as it is considered a paraphrase of the spirit of the times (concept of the architect Giedion) of the theoretical economist and philosopher Karl Marx, in his book Capital (Volume I), Chapter 13 when he argues that:

Every somewhat developed machine is made up of three substantially distinct parts: the moving mechanism, the transmission mechanism and the machine tool or working machine. The driving machine is the driving force of the entire mechanism. This machine can generate its own driving force, as does the steam engine, the hot air engine, the electromagnetic machine, etc., or receive the impulse from a natural force provided for this purpose, as does the water wheel of a waterfall, the blades of the wind, etc. The transmission mechanism, made up of flywheels, axles, cogwheels, spirals, shafts, ropes, belts, communications and devices of the most diverse kind, regulates the movement, makes it change its form when necessary, transforming it for example from perpendicular to circular, distributes it and transports it to the instrumental machinery. These two parts of the mechanism that we have been describing have the function of communicating to the machine tool the movement by means of which it holds and shapes the worked object. It is from this part of machinery, from the machine tool, that the industrial revolution of the 18th century began. And it is here that the constant transformation of manual or manufacturing industry into mechanized industry still has its daily starting point.

Indeed, it was with the “machine tool” (or “machine implement”) that the First Industrial Revolution originated in 18th century England. Since Marx’s original publication of economic theory in German was in 1867 (56 years before Le Corbusier), one can infer that there was an unintentional influence of Marx on Le Corbusier regarding the concept of “spirit of the age”, as discussed by architectural historian Sigfried Giedion in his book Mechanization Takes Command, published in 1948. In this work, Giedion analyses how mechanization influenced society and architecture, addressing the impact of technology on contemporary culture.

The relationship between the ideas of Le Corbusier, Karl Marx and Sigfried Giedion reflects a dialogue about modernity and industrialization. Le Corbusier's phrase connects with the influence of technology on human life, already present in Marx's thought. This intertextuality suggests that many architectural ideas are reinterpretations of previous concepts in a given historical and cultural context. Although there is no concrete evidence that Le Corbusier had read Sigfried Giedion (who published his most influential work in 1948, when Le Corbusier had already developed many of his ideas in 1923), both shared a similar intellectual context. Their works reflect common concerns about modernity, technology and architecture.

It is therefore assumed that Le Corbusier – in line with what Giedion argued – was influenced by the industrialising spirit of his time. Giedion, by analysing mechanisation, provides a framework that may have informed Le Corbusier, underlining the interconnection between disciplines and the importance of understanding architecture as a product of its time, in dialogue with Marx’s economic theory, already consolidated at that time.

Ceteris paribus, it is argued here that “the chair is a machine-tool for sitting.” In conclusion, considering the chair as a “machine-tool for sitting” allows for the exploration of the interrelations between design, functionality and social context. This perspective highlights how everyday objects are products of their time, reflecting both technological innovation and cultural adaptation, in an ongoing dialogue that encompasses the ideas of Le Corbusier, Marx and Giedion.

If we look closely at the machine tool, that is, the real working machine, we see reappearing in it, in general terms, although sometimes they adopt a very modified form, (…) Sometimes, the machine is, as a whole, nothing more than a more or less corrected mechanical edition of the old manual instrument, (…)

Great, Marx explains it perfectly in this Chapter 13 of Volume I of Capital; although we must be intellectually honest and say that he refers to other types of machinery such as spinning machines and analyzes three (3) concepts: the machine tool, the transmission mechanism or gears, etc. and the engine of the steam engine. James Watt's engine of the first steam spinning machine was the Spinning Mule, invented by Samuel Crompton in 1779, analyzed by Marx.

Karl Marx discusses the Spinning Mule and other types of machinery, addressing three key concepts: the machine tool which refers to the component that does the work, in this case, spinning cotton. The transmission mechanism refers to the elements that allow energy to be transferred from the engine to the machine tool (includes gears, pulleys, and other mechanisms that transform the engine's motion into useful motion for the spinning machine) and the engine of James Watt's steam engine. This was a milestone in England's First Industrial Revolution.

Le Corbusier described the LC4 Chaise Longue as a “machine for rest”, a phrase that reflects his functionalist approach and his belief in design as a means to improve the quality of life. Le Corbusier talks about furniture and its relationship to the human being, highlighting the importance of ergonomics and functionality in design. It encapsulates his vision that furniture should be designed for a specific purpose and should serve to enhance the well-being of the user, like a machine optimized for rest; this perspective is key to his work and reflected in his designs.

Development

In his monumental work, Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879) developed Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française du XIe au XVIe siècle (Reasoned Dictionary of French Architecture from the 11th to the 16th Century), this work was published between 1854 and 1869 in ten volumes. He not only analyses the formal and structural characteristics of Gothic architecture, but also contextualises these works in relation to the society of the time.

Viollet-le-Duc argues that architecture cannot be understood without considering the social, economic and political conditions that influenced it. For him, medieval architecture is the result of a specific "Social Order" that manifested itself through buildings, reflecting the values and organization of society at that time. His rationalist approach allowed him to articulate how works of Gothic architecture were intimately linked to the cultural and social identity of the medieval period.

This sociological approach has influenced many subsequent studies on the relationship between architecture and society, and his work is considered fundamental to understanding the evolution of architectural criticism and the history of architecture.

In the work of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, the term social order is not used explicitly as a technical term; however, its concept is implicit in his analysis. Viollet-le-Duc discusses how Gothic architecture reflects and responds to the social, economic, and political conditions of its time, and this idea can be interpreted as a reference to a social order.

His approach focuses on how architectural works are manifestations of the culture and social structures of the medieval period, suggesting that architecture is intrinsically linked to a specific social context. Although he does not use the term social order directly, his arguments about the relationship between architecture and society are clear and form a fundamental part of his analysis. In short, the concept of social order is present in his work, but more as an underlying notion that can be inferred from his sociological analysis of Gothic architecture.

But in Anderson's Doctoral Thesis (2014) the definition of social order has been used explicitly with a certain analogy to Giedion's spirit of the times.

The relationship between the social order in the work of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc and the spirit of the times of Sigfried Giedion can be established through the interaction between architecture, society and culture in different historical contexts; Viollet-le-Duc examines Gothic architecture as a manifestation of the social and cultural structures of the Middle Ages, suggesting that architectural works are reflections of a specific social order, where architecture is not only design, but is linked to the social organization, beliefs and values of the time. Likewise, Giedion in his work Space, Time and Architecture (1941) -translated as Espacio, Tiempo y Arquitectura in 1948- , speaks of the spirit of the times (or Zeitgeist) as the cultural and social influence that shapes artistic and architectural expressions, encompassing not only architecture, but also other cultural manifestations, and reflecting how technology, philosophy and social conditions influence design and construction. Both authors agree that architecture is a mirror of society and that, in order to understand it, it is necessary to consider the historical and social context in which it develops; Viollet-le-Duc emphasizes that the social order defines and limits architectural possibilities, while Giedion points out that the spirit of the times determines architectural trends and styles. Viollet-le-Duc's work can be seen as an analysis focused on the history and specific context of medieval architecture, while Giedion offers a broader vision that encompasses multiple periods and aspects of modern culture; however, both share the idea that architecture is inseparable from its social and cultural context, and that understanding an era requires the analysis of its social order and spirit.

Under these guidelines, it was sought and found that this is the theoretical contribution of this small work to research in the history of furniture design (non-industrial and industrial): to produce a few theoretical categories to interpret the stylistic complexity of the design as a result of three analytical categories of the social order that determined - influenced - four types of aesthetics applied to furniture design.

Early on, in earlier works, Anderson wrote that:

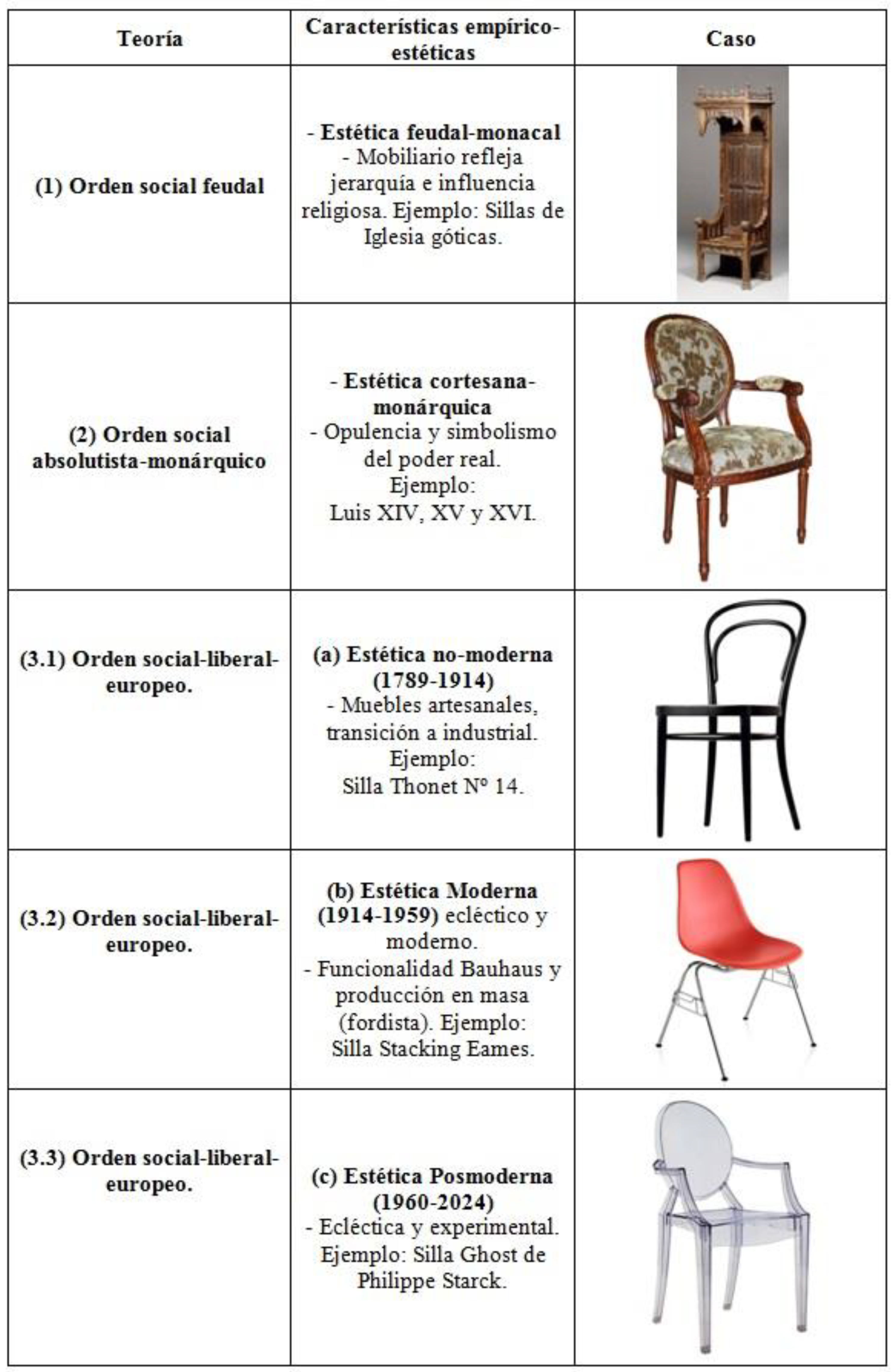

The Feudal Social Order:It is related to a feudal-monastic aesthetic typical of monastic furniture, where the furniture reflects the hierarchy and power of the Catholic Church (but there was also furniture for peasants, although to a lesser extent and quality). The furniture of this period was elaborate and represented an aristocratic lifestyle.

Example: Details about the prayer chair or choir chair: Design and Function: This type of chair often featured a simple, sturdy design with a high back and arms; it was usually made of wood, displaying craftsmanship, with carved details that could include religious motifs. Use: These chairs were used by monks and members of the clergy during religious ceremonies and prayer, reflecting the importance of religion in feudal life and the social hierarchy of the Church. Hierarchy: The choir chair symbolized the authority and status of members of the religious community; often, the most ornate and elaborate chairs were reserved for high-ranking clergy, while lower-ranking members used simpler chairs. Materials: They were made from hardwoods such as oak or pine, and could be adorned with upholstery that, although simple, was of a higher quality than that used by the peasant population.

This type of furniture not only illustrates the hierarchy and power of the Catholic Church in the feudal period, but also represents an aristocratic lifestyle and dedication to religion, fundamental elements of the feudal society of the time.

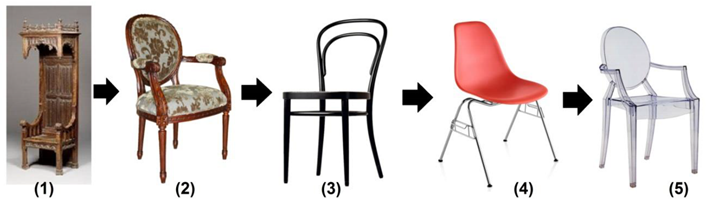

Plate 2: Example of the Feudal Social Order that generated a feudal-monastic aesthetic, prayer chair or choir chair of a Catholic Church.

The Absolutist-Monarchical Social Order:In this context, a courtly-monarchical aesthetic (1643-1789) was derived, typical of the Ancien Régime associated with the absolutist monarchies of the court of Louis XIV and his Palace of Versailles (which reflected opulence), incorporating the symbolism of royal power, with decorative elements that symbolized the authority of the monarchy, where the furniture also reflects the opulence and power of the monarchy, as were the Baroque and Rococo.

Example: Louis XIV Style (1643-1715): Also known as the French Baroque style, this style reflects the opulence and authority of the absolutist monarchy; chairs from this period, such as the armchair and bergère chair, are characterized by their robust forms, ornate carvings, and the use of luxurious materials such as gilded wood and rich upholstery; designs often incorporate decorative motifs such as acanthus leaves and symbolic elements that exalt the power of the king. Louis XV Style (1715-1774): Known as the Rococo style, this period is characterized by greater lightness and elegance in design; chairs, such as the Cabriolet chair, feature curvilinear shapes, tufted seats integrated with floral patterns, and delicate finishes; decoration is more exuberant, but less rigid than in the previous period, reflecting the influence of nature and the intimacy of court life; the use of painted and gilded wood is also common. Louis XVI style (1774-1792): This style is a response to Rococo and is inspired by classical antiquity; chairs, such as the medallion chair and the desk chair, have straighter lines and a more austere structure; neoclassical motifs are used, such as columns and garlands, and materials include light wood and more sober upholstery; this style reflects a search for balance and harmony, aligning with the ideals of the Enlightenment and a critique of the opulence of the past. Together, these styles not only reflect the aesthetic trends of their times, but also the evolution of furniture in relation to the power and social order of the absolutist monarchy in France.

Plate 3: Example of the Absolutist-Monarchic Social Order that generated a courtly-monarchic aesthetic, Louis XVI chair.

We know from Hypothesis No. 1 or the pre-modern hypothesis: Hypothesis No. 1 on the design of pre-modern objects holds that in this context, the beautiful (aptum) equals the true (verum), and the useful (utile) equals the good (bonum). This implies that in pre-modern designed objects, functional utility and aesthetic beauty were unified, that is, the beautiful (the aesthetic), the useful (the logical), and the good (the ethical) were considered equivalent. In these objects, functional utility and aesthetic symbolism were integrated, meaning that use-value was both functional and aesthetic and ethical, a unification based on vernacular, artisanal production methods, where beauty and utility complemented each other.

Use-value in this context is understood as a unity of the useful, the beautiful and the good. Premodern design objects integrated functionality, aesthetics and ethics, so that an object was considered beautiful because it was useful and served an ethical purpose. This approach also emphasized an aesthetic-sign-value, intrinsically linked to use-value, where aesthetics were not separated from functionality. A beautiful object was both functional and symbolic, reinforcing its value in the community.

In addition, there was a symbolic use-value, which referred to the ability of an object to represent cultural or ceremonial meanings. Objects not only served practical functions, but also had a symbolic meaning that strengthened their social value. In this pre-modern framework, there was no capitalist exchange-value, as objects were valued for their function, beauty, and meaning in society, and not for their ability to be exchanged in the market.

The Liberal Social Order:More recent studies have made it possible to adjust this concept, which in the past - formulated by Anderson - was thought of as a double aesthetic; and ended up, some time later, developing as a triple aesthetic: (a) non-modern (1789-1928) typical of 17th and 19th century handcrafted furniture, (b) modern (1928-1959) typical of 20th century furniture and (c) postmodern (1960-2024).

Going deeper, (a) the non-modern bourgeois manufacturing aesthetic (1789-1914), this period mentioned spans from the French Revolution in Europe, to the eve of the First World War (1914), a time of radical changes in all aspects of society, including aesthetics and design.

It includes the production of furniture that is still predominantly handcrafted, meaning that it is not based on mass production or the industrial techniques that were developed later, such as those used in Fordist production; furniture from this period reflects a transition between the Classical style, with its ornamental and symmetrical features, and Modernism (Art Nouveau, Futurism, Cubism, Constructivism, Suprematism and Functionalism), which would begin to take shape in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Such furniture of the non-modern bourgeois aesthetic is marked by a focus on craftsmanship and detail, with elaborate decorative elements in contrast to what would later become mass production.

It is important to note that for much of the 19th century, craftsmanship remained important in furniture production. However, it is crucial to note that the Industrial Revolution, which began in the late 18th century and developed throughout the 19th century, brought about significant changes in production methods. Although many pieces of furniture were still handcrafted, industrialization began to impact production as the century progressed. This resulted in the introduction of mass production techniques, the use of machinery, and the standardization of designs, especially for more affordable furniture aimed at the working class. Therefore, it is important to note that although craftsmanship was relevant, industrialization was beginning to transform the landscape of furniture design, which created a coexistence of traditional (handcrafted) and new (industrial) techniques.

Throughout history, design has maintained a close relationship with craftsmanship, although this link has been underestimated on several occasions, relegating the fundamental role of the artisan in cultural and social development. This link has been dialectical, with moments of convergence and others of distancing. However, this interaction has proven to be fruitful, especially in Latin America, where artisanal production continues to play an essential role in local economies, in contrast to industrialized countries where it has been replaced by mass production.

Contemporary design has inherited key principles of craftsmanship, such as the conscious use of materials, applied technologies and aesthetic value. William Morris (1834-1896), one of the pioneers in defending the craft ethic within industrial production, argued that “nothing should be made that does not give pleasure both to the maker and to the user, and that pleasure in making must produce art in the hands of the worker.” This statement, taken from his essay Art Under Plutocracy (included in How We Live and How We Might Live), underlines the importance of enjoyment and satisfaction in the creative process.

On the other hand, Henry van de Velde (1863-1957) also recognized the need to adapt artisanal methods to new forms of industrial production, highlighting the constant effort to integrate tradition and modernity in the evolution of design.

We know from Hypothesis #2 or the modern hypothesis: Hypothesis #2 on modern product design holds that there is a separation between beauty (the aesthetic or subjective), good (the ethical), and useful (the logical or objective). In this context, Kantian-adherent-beauty is seen as purely subjective and ornamental, detached from logic, while Kantian-usefulness is seen as purely objective and rational, focused on utility. This separation reflects a Cartesian-Kantian dialectic, where Llovetian-functional-use-value is fragmented or alienated from Kantian-adherent-beauty.

In industrial capitalism, the exchange-value-sign or aesthetic-symbolic-socioeconomic-Llovetian value emerges, associated with objects of design produced industrially using Taylor-fordist methods. Thus, the use-value in modernity is fragmented, separating the useful from the beautiful and the good. Objects are designed with a priority focus on functionality, while aesthetics become ornamental and secondary.

The aesthetic sign-value or aesthetic use-value becomes a purely subjective and decorative element, seen as an addition to the object, but not essential to its functionality. The symbolic use-value is also fragmented, becoming more associated with social status and capitalist consumption than with its intrinsic cultural meaning.

Exchange value becomes central in modernity, as objects are mass-produced and transformed into commodities within the context of industrial capitalism. This value is linked to economic exchange and the ability of an object to be marketed or sold, prioritizing its market value over other aspects such as aesthetics or functionality.

Example: The Thonet 14 chair, also known as the bistro chair or the café chair, is an excellent example illustrating the transition between artisanal production and industrialisation in furniture design of this period. Designed by Michael Thonet (1796-1871) in Austria in 1859. It has a rational logic, which is not rationalistic.

The Thonet chair No. 14 possesses a rational logic, but is not rationalistic, similar to the principles of the Modern Movement in architecture and design, such as the Bauhaus. Thonet used methods that maximized efficiency, such as standardization of parts and division of labor; this reflects a rational approach to organizing production to achieve better results. The chair was conceived to be comfortable and practical, prioritizing functionality; this attention to the user's needs indicates a rational approach, where design responds to criteria of utility. In addition, Thonet applied advanced techniques, such as wood bending, demonstrating a logical understanding of materials and their properties; this innovation points to a design based on logic and effectiveness. Unlike rationalism, which seeks universal truths, Thonet's logic adapts to the specific needs of the market and consumers; his design responds to a concrete social and cultural context, without relying on abstract principles. Thonet also took into account the user's interaction with the object, which is a departure from rationalism, which often ignores emotional and subjective aspects in favour of a purely logical approach. The Thonet chair No. 14 allows for some customization and adaptation, implying a response to changing environmental conditions; rationalism tends to be more rigid in its postulates and theories. Like Thonet, the Modern Movement and the Bauhaus focused on functionality, simplicity and the use of new materials, seeking practical and aesthetically pleasing solutions; however, the Modern Movement is often associated more with a rationalist approach, as it sought universal and normative principles in design, whereas Thonet focused on more practical and contextual solutions, not locked into a rigid philosophical system. In short, the Thonet chair No. 14 exemplifies a rational logic through its efficiency and functionality, but it is not rationalist because it is based on a practical and contextualized approach, prioritizing the user experience and adapting to their specific needs.

The Modern Movement in architecture and furniture design, such as that promoted by the Bauhaus, can be said to have rationalist elements. This is for several reasons: the search for universal principles; the Modern Movement was based on the idea that design should follow universal principles of functionality and aesthetics; this approach seeks truths that apply generally to all contexts, which aligns with rationalism. Secondly, the use of reason and logic; the Bauhaus designers applied logical methods in the design process, emphasizing the importance of reason in creating functional and aesthetically pleasing objects; this reflects the rationalist belief that reason can guide design towards truth and beauty. Furthermore, standardization and functionality are noted; the Modern Movement advocated standardization and mass production, seeking to create furniture and spaces that were accessible and functional to all; this rationalized approach contrasts with the more subjective and personal design of earlier eras. Lastly, the disdain for the ornamental; The rationalists at the Bauhaus rejected unnecessary ornamentation, promoting simple, functional forms; this simplification is based on the idea that design should serve a logical and practical purpose. In conclusion, although the Modern Movement and the Bauhaus also focus on user experience and context, their principles and methods reflect a strong rationalist influence, seeking universal truths in design and construction that transcend the particular; this establishes a connection between rational logic and the design philosophy of that time.

One issue is the logical and rational use of design in an object (with certain degrees of freedom), another issue is rationalist abuse as the only way to achieve aesthetic truth.

In fact, manufacturing, according to Marx, Chapter 12 of Volume I of Capital, goes from 1550 to 1789, if the French Revolution occurred in 1789 when manufacturing was being abandoned and mass industrialization was being born, the Thonet chair No. 14 is a manufacturing chair design, incipiently industrial (not Fordist). The Thonet chair No. 14 is considered an incipiently industrial design, although it still reflects characteristics of manufacturing. Thonet used mass production techniques that were in transition between traditional manufacturing and mass industrialization, but did not reach the level of automation and standardization of Fordism that would develop later in 1908 and 1920.

Manufacturing, according to Marx, is a mode of production that emerged with the industrial revolution and is characterized by the division of labor and the use of more complex tools compared to craftsmanship. In manufacturing, a production process is broken down into several stages, with each worker specializing in a specific task. This allows for greater efficiency and mass production (which is not yet Fordist).

Manufacturing refers to a production system that emerged in the Industrial Revolution, where the division of labor is implemented; in manufacturing, workers specialize in specific tasks, but the process may still involve a considerable level of manual skill (such as crafts). On the other hand, craftsmanship is based on manual labor and the individual skill of the craftsman, who controls the entire production process of a good. In craftsmanship, each product is unique and reflects the creativity of the producer, while in manufacturing products are more homogeneous and produced in large quantities. In short, the main difference lies in the organization of work: manufacturing is characterized by the division of labor and mass production, while craftsmanship focuses on individual work and customized production.

The Thonet chair No. 14, estimated to have been produced in over 50 million units since its launch, making it one of the most produced chairs in history. In terms of its relation to the period, it is emblematic for being one of the first chairs produced using mass production techniques, reflecting the industrialisation that was beginning to impact furniture manufacturing in the 19th century, and its design and construction allowed it to be produced more efficiently, facilitating its dissemination in cafés and restaurants; despite its mass production, the chair also retained artisanal aspects in its design, such as the curvature of the wood achieved through a steam process, which shows the coexistence of traditional and new methods, as Girod mentions in his analysis; furthermore, it combines functionality and aesthetics, key elements that would begin to be valued in modernism, and its lightweight and stackable design makes it suitable for commercial use, aligning with the idea that furniture should be accessible and practical. In short, the Thonet 14 chair exemplifies how the Industrial Revolution began to transform furniture design, integrating both artisanal production and new industrial techniques, which is why it is a non-modern (non-Bauhaus, non-Fordist) bourgeois (industrial) aesthetic.

But Thonet uses rational methods for mass production, although he is not a Fordist, he inaugurates mass manufacturing, superior to low-scale craftsmanship (almost single pieces), but inferior to Fordism and its production scale (high series or manufactured units).

Thonet's mass production, while not strictly adhering to the Fordist model, represents a crucial point in the evolution of manufacturing. His approach is based on several rational methods that differentiate it from both traditional craftsmanship and Fordist mass production. Thonet developed a production system that used standardized parts, which allowed for the manufacture of furniture that could be assembled efficiently, reducing production time and increasing the consistency of the final product; instead of a single craftsman creating a complete piece, he implemented a division of labor where different operators were responsible for specific tasks, thus increasing productivity and facilitating the training of workers; the use of plywood and wood bending techniques allowed for the creation of aesthetically pleasing and structurally efficient shapes, contributing to a reduction in costs and an increase in production.

Unlike artisanal production, where each piece is unique and time-consuming, Thonet's production guaranteed a consistent level of quality and design in each unit, essential to meet growing demand; by streamlining the process, Thonet was able to offer designer products at more accessible prices, democratising access to quality furniture.

Although he was able to mass produce, his scale was smaller compared to the Fordist model, which further optimized mass production through assembly lines and an almost mechanical approach, and did not use the same intensive automation; in addition, Thonet's production allowed for some flexibility in design, something that Fordism sought to minimize in order to maximize efficiency, while maintaining a focus on the aesthetics and functionality of its furniture.

In conclusion, Thonet's contribution to the concept of mass production lies somewhere between craftsmanship and Fordism; his rational methods allowed for more efficient production than traditional craftsmanship, while laying the groundwork for later developments in mass manufacturing, and are a testament to how process innovation can transform the furniture design and production industry.

Plate 4: Thonet chair No. 14 from 1859, a clear example of the Liberal Social Order that generated a non-modern aesthetic (1789-1928).

The (b) modern bourgeois aesthetic (1914-1959) is a stage that is significant for the impact of movements such as the Bauhaus, which introduced a break with the decorative style of the past. The modern bourgeois aesthetic is characterized by functionality, simplicity and the use of innovative materials. Bauhaus furniture, for example, integrates design and functionality, abandoning excessive ornamentation in favor of clean lines and practical structures. In this period, the idea that design should be accessible and functional for the common citizen is promoted, thus reflecting the values of the expanding middle class. This modern furniture is also associated with industrial production, which allowed for a greater diffusion and democratization of design. This stage already involves using Fordist methods of production.

Example: The Eames DSW (Dining Side Chair Wood) and the Eames Stacking Chair are iconic examples of modern bourgeois aesthetics, illustrating the functionality, simplicity and mass production that characterise this period. The Eames DSW chair was designed by Charles Eames and Ray Eames in 1950, in the United States, and it is estimated that over 15 million units have been produced, making it one of the most iconic chairs in modern design. On the other hand, the Eames Stacking Chair was designed by Charles Eames in 1952, also in the United States, and although there are no exact figures, it is estimated that several million of these chairs have been produced, reflecting their popularity and use in a variety of settings. Both chairs reflect Bauhaus principles, emphasising simplicity in design, functionality and the use of innovative materials such as plastic and plywood. Their mass production allowed these pieces of furniture to become accessible to the common citizen, aligning with the values of the expanding middle class and demonstrating how industrial design began to democratize access to quality pieces of furniture. These chairs are perfect examples of how modern bourgeois aesthetics combined artisanal tradition with industrial innovation.

Manufacturing and Fordist mass production are distinct concepts, although both involve some organization of work. Manufacturing refers to a production system that emerged in the Industrial Revolution, where the division of labor is implemented; in manufacturing, workers specialize in specific tasks, but the process may still involve a considerable level of manual skill. Production is more efficient than in craftsmanship, but is not necessarily completely mechanized. On the other hand, mass production (Fordist), developed by Henry Ford in the early 20th century, takes the division of labor and efficiency to a new level, using assembly lines and advanced machinery. In this system, products are manufactured in high volumes with a focus on standardization and cost reduction; workers perform very specific and repetitive tasks, limiting their ability to exercise creativity or control over the process. In short, while manufacturing is based on the division of labor with a focus on specialization, Fordist production elevates this idea through automation and large-scale mass production.

Plate 5: The Eames Stacking Chair from 1859, a clear example of the Liberal Social Order that generated a modern aesthetic (1914-1959).

The (c) Postmodern bourgeois aesthetic (1960-2024) emerged as a response to the principles of modernism, incorporating the plurality of styles and irony in design. This period is characterized by a mix of influences and a penchant for customization, where the barriers of what is considered good or bad aesthetics are broken. Postmodern designers, such as Philippe Starck and Ettore Sottsass (1917-2007) experimented with unconventional shapes, colors and materials, creating furniture that often challenged traditional norms and promoted a more playful and eclectic approach. This approach allowed for greater individual expression, reflecting the diversity of contemporary society.

We know from Hypothesis No. 3 or the postmodern hypothesis: it is argued here that the design of postmodern objects suggests that in this context it is necessary to resort to other authors in order to broaden the analytical categories. In postmodernity, we observe a simulated unification (Baudrillardian-simulation) and an ironic play (Lyotardian-ludic) with modern rationality, which implies that postmodern design objects are manufactured through a mixture of artisanal, semi-industrial and industrial methods, sometimes post-Taylor-fordist. This hypothesis indicates that postmodernity recovers the premodern union fragmented by modern thought, but it does so from a modern perspective, recognizing that the past becomes a simulation of the present.

Derridanian antilogocentrism, based on Jacques Derrida's (1930-2004) critique of the centrality of reason in modern thought, implies a break with traditional structures, suggesting that in postmodernity logic and reason are played with ironically. This leads to a fragmentation and lack of unification in design, which emphasizes plurality and heterogeneity, integrating diverse influences and methods.

In this context, postmodern use-value is more complex and plural. Objects can have multiple functions and meanings, and functionality is not the only measure of their value. Aesthetic sign-value is reinterpreted in a framework where aesthetics can be both functional and symbolic, intertwining without the need for clear unification, allowing for a diversity of interpretations.

Symbolic use-value is broadened to encompass a variety of cultural and social meanings, where objects are seen as symbols of identity, status or belonging. Although exchange-value remains relevant, in postmodernity its primacy is questioned, considering objects both as commodities and elements of cultural consumption, operating in a context of plurality and diversity that transcends their economic value.

Example: The Ghost Chair by Philippe Starck is an emblematic example of this aesthetic: author: Philippe Starck, France, year 2002, material: transparent acrylic, giving it an almost ethereal appearance and making it suitable for a variety of decorative settings, units produced: while there are no exact figures, it is estimated that several million units have been produced, making it an icon of contemporary design. Important concepts of the Ghost Chair: design and functionality: the chair combines a classic design, inspired by the shapes of antique furniture, with a modern material and a minimalist aesthetic, reflecting the eclectic and experimental approach of postmodernism; transparency and versatility: its transparent acrylic material allows it to be integrated into various environments, breaking the barriers of the traditional perception of furniture, which is usually opaque and heavy; accessibility: despite its distinctive design, the Ghost Chair has been produced in large numbers, making it accessible to the general public, reflecting the democratization of design; In short, the Ghost Chair is a clear example of how postmodern bourgeois aesthetics challenges the norms of traditional design and promotes diversity and innovation.

Plate 5: Philippe Starck's Ghost from 2002, a clear example of the Liberal Social Order that generated a postmodern aesthetic (1960-2024).

Conclusions

It should be noted that historical materialism and Marxist economic theory are, above all, sophisticated analytical tools designed to unravel the nature of capitalism and its evolution throughout history. This approach is based on a rigorously scientific and critical foundation, aimed at understanding the objective economic dynamics that shape societies: ownership of the means of production, exploitation of wage labour and the distribution of wealth, among other essential factors. These economic categories are not merely descriptive, but allow us to discern the internal contradictions that underlie the capitalist system, thus facilitating a deep reading of its cyclical crises and its tendencies towards the concentration of capital and the increase in inequality. (In contrast, communism and socialism, in their various meanings, represent normative projects and ideological systems that aspire to replace capitalism with other forms of economic and social organization. These systems, in some cases, propose authoritarian and non-democratic forms of government, which places them in a political sphere distant from strictly Marxist economic analysis. Although such ideological proposals are inspired by the critique that Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels developed regarding capitalism, they do not constitute an integral part of their economic theory in the strict sense, but are political interpretations derived from it.)

The phrase "the idea of the chair as a sitting-machine tool through premodernity, modernity and postmodernity" relates to a multidimensional interpretation of the evolution of the chair throughout different historical periods, using concepts from Karl Marx and other design theorists and its relationship to economic and social context.

In pre-modern times, the chair was not only a functional object, but a symbol of power and hierarchy, especially in religious and aristocratic environments. The function of the chair was linked to its symbolism, as an object of worship. This stage unified the beautiful, the useful and the good, integrating function, aesthetics and ethical value.

In modern times, influenced by the Industrial Revolution, the chair began to separate itself from its symbolism. The aesthetic value of its functionality was fragmented, prioritising mass production and utility, exemplified in designs such as the Thonet Nº 14 chair. Here, the chair became an accessible product for the new bourgeois class, highlighting its exchange value in a capitalist market.

Finally, in postmodernism, the chair takes on a symbolic character and plays ironically with modern norms. Designs such as Philippe Starck's Ghost chair challenge strict functionality, becoming aesthetic statements that criticize the conventions of the past. Here, the chair becomes a machine tool again, but with a focus on the diversity of styles, meanings and uses that transcend its simple function.

It is therefore imperative to make a clear and precise distinction between, on the one hand, Marxist economic theory, which is framed within a rigorous analysis of the economic structures of capitalism, and, on the other, the revolutionary political proposals that emanate from its critique. The latter, such as communism and its variants of socialism, are not the subject of interest in this document and, therefore, should not be confused with Marxist economic theory, which focuses on explaining the emergence and development of capitalism from a historical and materialist perspective, without necessarily implying adherence to a particular political project. Thus, we clearly differentiate the academic analysis of the capitalist phenomenon from the political ideologies that have been articulated around this analysis, which, as noted, are not the focus of this study.

A conclusion that integrates art, sociology, anthropology, economics and chair design from your text could focus on how the chair becomes a multidimensional symbol that encapsulates social and economic tensions over time. In his analysis Girod - these ideas have been worked on in his Master's Thesis and continue to be worked on in the current development of his PhD Thesis - mentions the interrelation of furniture design with the historical context, but a novel conclusion could explore how the chair becomes a cultural vehicle that transmits changing ideologies, reflecting economic and political transformations.

From an anthropological perspective, the chair has ceased to be a simple functional object. In pre-modern societies, chair design, especially for elites, responded to needs for status and power, serving as cultural markers of hierarchy. This is seen in the evolution of the monastic chair or the royal chair, which denoted not only the function of sitting, but social position within a feudal or absolutist order. The chair symbolized an artifact of authority and social differentiation.

From an economic point of view, the transition to modernity with the Industrial Revolution marked a shift towards the democratisation of furniture, transforming the chair into an object of mass production. Here, the design of chairs, such as the Thonet model No. 14, was inscribed in the capitalist logic of exchange value, where design sought to adapt to the new emerging classes, particularly the bourgeoisie, and to satisfy the demands of an ever-widening market. Mass production allowed the chair to go from being a luxury for the elite to an object of common use, linking its design to economic accessibility and productive efficiency.

From a sociological perspective, the modern chair not only represents economic accessibility, but also a symbol of the transformation of work. Functionalist industrial design, driven by movements such as the Bauhaus, focused on ergonomics and functionality to adapt the object to the new ways of working in industrial society, especially in offices. Here the chair takes on a role in the configuration of the work space and in the production of human capital, where the comfort and efficiency of the worker are paramount.

Art, throughout these transitions, has played a key role in straining the relationship between functionality and aesthetics. In postmodernism, the chair begins to reflect a playful and ironic approach to design, as exemplified by Philippe Starck’s Ghost chair, which challenges functional norms in favor of an aesthetic play that unsettles and redefines what we understand by furniture. The symbolic value of the chair in the postmodern era goes beyond its use, becoming an art object that communicates ideas about the ephemeral, the visible and the invisible, challenging traditional notions of materiality and physical presence.

Finally, from a contemporary design perspective, the chair is no longer just a utilitarian object, but a manifesto of cultural identity. The example of gaucho criollo design in Argentina, to which Girod (2022) refers, reflects how local design has been transformed into a statement of cultural resistance to globalization, highlighting the importance of artisanal techniques in the creation of chairs that not only serve a function, but also symbolize local heritage and traditions.

In short, what is novel here would be that the chair as a design object functions simultaneously as a symbol of power, an economic reflection of industrialization, an evolving cultural artifact, and an art object with multiple interpretations. This complexity allows the chair to transcend its original function, connecting social, political, and economic dynamics at every historical stage, making it one of the most culturally charged objects in the history of design.

So we end with this illustrative table as conclusions.