1. Introduction

Patella alta, also referred to as high patella, represents a pathological condition characterized by an elevated position of the patella in relation to the femur [

1]. The elevated position of the patella is associated with a shallower femoral groove, which results in a reduction in lateral containment of the patella. As the depth of the femoral groove is reduced, the ability of the patella to move smoothly within the groove is impaired, particularly during flexion of the knee. This altered biomechanical alignment results in an increased moment arm for the quadriceps muscle, which delays patellar engagement and reduces the patellofemoral contact area. The resulting misalignment can result in excessive stress being placed on the patellofemoral joint, which may contribute to the development of patellofemoral pain (PFP) [

2]. In clinical practice, a high patella is recognized as a risk factor for both patellofemoral syndrome and patellar instability [

3]. Patients frequently report acute joint pain following direct trauma or sudden changes in direction, which can be attributed to the medial rotation of the femur over the stabilized tibia [

4]. This rotational movement can result in a sensation of patellar subluxation, which is a protective response due to the inhibition of the quadriceps from pain [

5]. Furthermore, patients may experience rapid hemarthrosis, severe knee pain and limited range of motion in knee flexion. Additionally, patellofemoral pain may manifest as a progressively deteriorating anterior knee syndrome, particularly during physical activities that elevate joint reaction forces, such as stair climbing, squatting, or prolonged sitting [

6,

7]. Such activity-related pain is frequently indicative of chondral damage [

8].

Patella baja, also known as low-lying patella, is a pathological condition in which the patella is abnormally positioned lower than normal in relation to the femoral trochlea. Despite this displacement, the patella remains within the trochlear groove throughout the full range of knee extension [

1,

4,

6,

9]. This condition can result from progressive shortening or contracture of the patellar tendon, which causes the patella to move downward. It is often the result of knee trauma or iatrogenic complications following surgery, particularly when patellar tendon autograft is harvested for reconstructive surgery [

10,

11]. The causes of patellar baja are multifactorial and include direct trauma to the patella, periarticular fractures, chronic quadriceps tendon rupture, quadriceps paralysis and muscle dysfunction due to conditions such as poliomyelitis or complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) [

12,

13]. Clinically, patellofemoral pain can present with chronic anterior knee pain, weakened extensor mechanism and limited knee range of motion, all of which can significantly impair functional mobility and quality of life [

14,

15,

16,

17].

The role of patella height in the pathophysiology of patellar alta and patellar baja remains a subject of debate. Patellar alta is recognized as one of the anatomical risk factors that may contribute to patellar instability within the patellofemoral joint [

18,

19]. It has been implicated in a variety of knee disorders, with patellofemoral instability and recurrent patellofemoral dislocation being among the strongest associations [

20,

21]. The association between patellar alta and chondromalacia patella has been a matter of controversy, with the majority of investigators demonstrating a positive association, [

20,

22,

23]. while others have failed to establish a definitive correlation [

24,

25,

26]. Patellar alta can result from sports injuries, but it is predominantly a congenital/developmental condition that is not related to trauma [

27,

28]. In most cases, patellar baja is not associated with functional abnormalities. The shortened patellar tendon can be either congenital or acquired. Patellar baja is occasionally observed as a surgical complication in procedures such as tibial tubercle transfers in young patients, in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty,[

16]. and in association with scarring and contracture of the anterior soft tissues and patellar tendon entrapment [

14,

15].

The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying variations in patellar height are not fully understood. Therefore, the present study was designed to investigate the relationship between patellar height and the biomechanical properties of the quadriceps and hamstrings, including muscle strength and muscle tone, as well as knee joint range of motion. Our hypothesis is that patellar height is influenced not only by muscle strength, but also by muscle tone and knee joint range of motion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Sample size estimation was conducted utilizing G*Power software, version 3.1.9.7. In a preliminary pilot study involving four participants, we determined that a testing power of 0.90, an effect size of 0.783, and a significance level (α) of 0.05 were necessary to achieve a sample size of 12. To account for an anticipated dropout rate of 20%, and to ensure the specificity and validity of the correlational research, the target sample size for this study was adjusted to 34 participants (

Table 1). Participants were excluded based on the following criteria: a current or historical incidence of knee injury or pathology; any history of knee pain during recreational activities or daily living; or a body mass index (BMI) exceeding 30. All participants provided informed consent by reading and signing the university-approved human subjects’ authorization form prior to their involvement. Before commencing the study, participants were required to sign a consent form and were reminded of their right to withdraw from the study at any time.

2.2. Study Procedure

Thirty-four participants were recruited for this study. In order to avoid the influence of muscle tone, fatigue and other factors caused by muscle strength testing on muscle tone and patellar height, this study conducted experimental measurements and data collection in the order of patellar length, patellar tendon length, muscle tone, ROM, and muscle strength. There was resting time 30 s after each trial and for 5 min among measurement of muscle strength to inhibit muscle fatigue.

2.3. Measurements

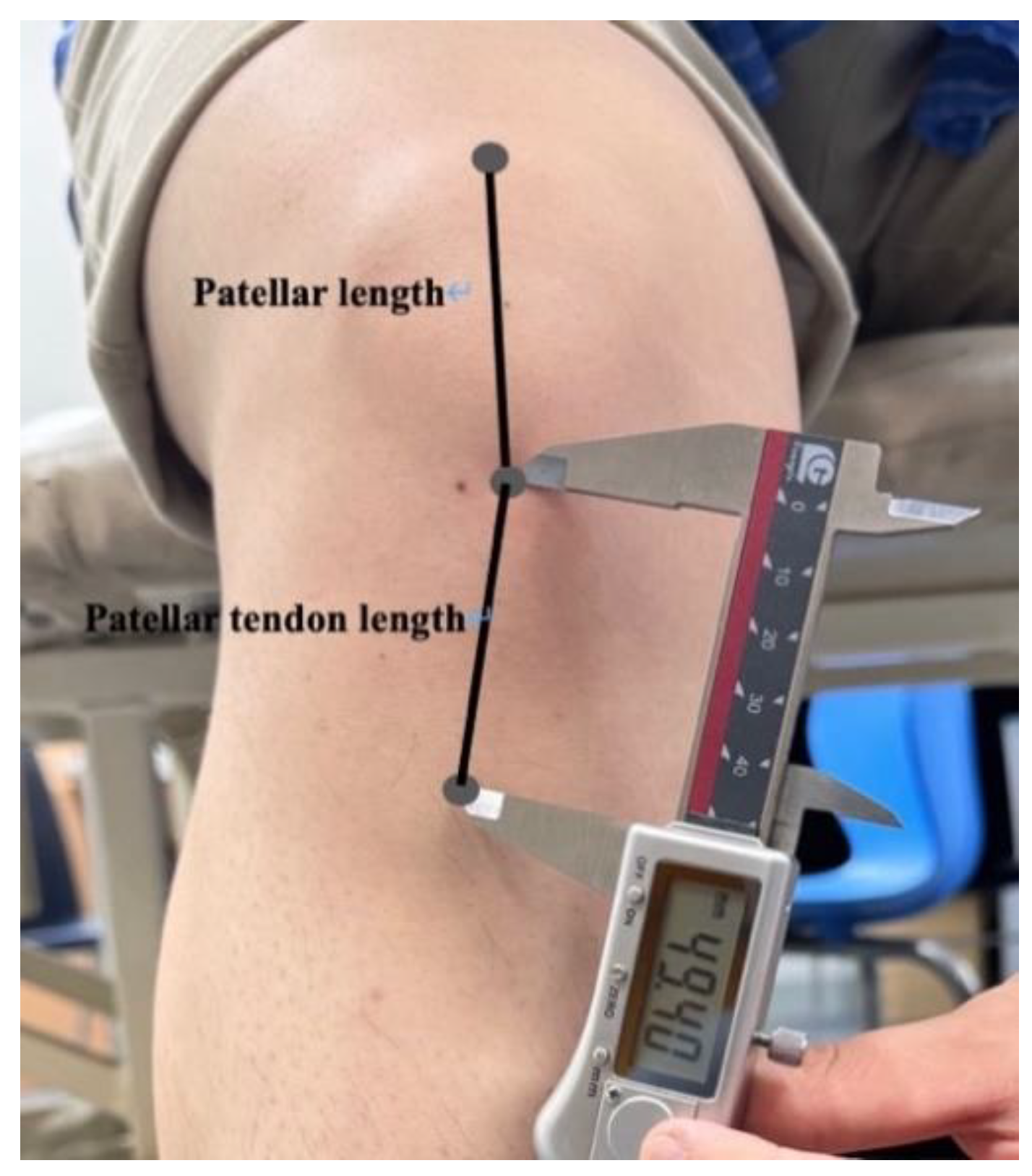

2.3.1. Measurement of Patellar Height

In this study, participants were seated in a chair with the knee joint flexed at a 30-degree angle to ensure relaxation of the quadriceps femoris muscle, thus preventing any muscular contraction that could affect the validity of the tendon length measurements. A digital vernier caliper, with a precision of 0.01 mm and a measurement error of ±0.02 mm, was used to measure the lengths of the patellar tendon (PT) and patella (PTL). The device provided clear digital readouts of the measurements, presented in a format that ensured the data was readily interpretable. In order to measure the length of the patellar tendon (PT), the examination was conducted with the aid of a digital vernier caliper, with the superior and inferior poles of the patella marked with a computer marker. The length was then measured from the marked superior pole to the inferior pole with the digital vernier caliper. Similarly, the patellar tendon length (PTL) was measured by marking the most prominent point on the tibial tuberosity and measuring the distance from the lower edge of the patella to this point (

Figure 1). In order to assess patellar height, the Insall-Salvati index (ISI) was used to calculate the ratio of patellar tendon length to patellar length. Normative ISI values range from 0.8 to 1.2, with values above 1.2 indicating patella alta and below 0.8 indicating patella baja [

29]. To ensure measurement reliability, each participant underwent three trials, and the average value was used for analysis.

2.3.2. Measurement of Quadriceps Muscle Strength

The Hand-Held Dynamometry (Manual Muscle Tester, MMT, South Rd. Hilton South Australia) was used for maximum isometric quadriceps contraction at 30° of knee flexion seated (ICC = 0.8-0.96) [

30,

31]. In the experimental setup, participants were positioned with their knees aligned at the edge of a platform and their knee joints flexed to a 90-degree angle. They were seated on an elevated platform to prevent their feet from contacting the floor, thereby eliminating any ground reaction forces that could interfere with the measurements. Participants were then instructed to raise their affected leg to a 60-degree knee flexion angle, followed by a controlled leg extension. During the procedure, participants were instructed to cross their hands over their chest and maintain a stable body position to minimize compensatory movements that could affect measurement accuracy. The MMT device was securely mounted on a stable stand with adjustable height settings to accommodate subjects of varying statures. The MMT device’s inclination angle could be adjusted up to 30 degrees to ensure proper alignment and comfort for each participant. To ensure data consistency and reliability, the peak force recorded during a 5-second interval was selected for analysis. Three trials were conducted for each participant, and the results were averaged to obtain a representative measure of muscle strength.

2.3.3. Measurement of Quadriceps Muscle Tone

The Myoton (MyotonPRO, AS, Tallinn, Estonia SN 000468) measured muscle stiffness. Exact locations of Myoton in Quadriceps: 1) Vastus lateralis: Midpoint from the upper pole of the patella to the greater trochanter; 2) Rectus femoris: Two-thirds distally from the most anterior aspect of the anterior superior iliac spine to the superior border of the patella; 3) Vastus medialis: At 80% on the line between the anterior superior iliac spine and the joint space in front of the anterior border of the medial ligament. The device's probe was positioned vertically over the marked measurement points on the skin surface of the three targeted muscles. The device was held gently and steadily at the starting position of the probe until it automatically completed the impact measurement process. Three measurements were conducted for each participant, and the mean value was calculated for analysis.

2.3.4. Measurement of Nee Flexion Range of Motion

Knee flexion range of motion was measured using a goniometer. The placement of the goniometer was as follows: 1) the axis was positioned at the lateral epicondyle of the femur; 2) the stationary arm was aligned with the femur, extending to the greater trochanter; and 3) the movement arm was aligned with the fibula, extending to the lateral malleolus. Participants were positioned in a supine posture with the knee fully extended and the hip at 0° of extension, abduction, and adduction. During the knee flexion measurement, the experimental testers stabilized the femur to prevent any rotation, abduction, or adduction. Three measurements were performed for each participant, and the average value was used for analysis.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

In this study, data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. All data were tested for normal distribution by using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to determine the associations between patellar height and quadriceps muscle strength and stiffness and knee ROM. A correlation coefficient (r) > 0.75 was considered “ Excellent”, 0.50—0.75 was “Good”, 0.25—0.50 was “Moderate”, 0.00—0.25 was “Poor” relationship [

34]. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28.0 for Windows software (SPSS Inc., IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). The statistical significance level was set at 0.05.

3. Results

The general characteristics of the participants are summarized in

Table 1. The mean age was 24.1 years, the mean height was 170.1 cm, the mean weight was 64.3 kg, and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 22.0 kg/m².

Table 1.

General characteristics of subjects.

Table 1.

General characteristics of subjects.

| Characteristics |

Mean ± SD 1

|

| Age (years) |

24.1 ± 2.20 |

| Height (cm) |

170.1 ± 7.13 |

| Weight (Kg) |

64.3 ± 13.20 |

| Body mass index (Kg/m2) |

22.0 ± 3.32 |

| Female / Male (n) |

16 / 18 |

| Patella height (ISI) |

0.86 ± 0.11 |

| Patella height style(n) |

Alta |

0 |

| Normal |

26 |

| Baja |

8 |

A significant positive correlation was observed between patellar length and quadriceps muscle strength (r = 0.507) (

Table 2). Similarly, a significant positive moderate correlation was found between patellar tendon length and quadriceps muscle strength (r = 0.407) (

Table 2). The rectus femoris oscillation frequency exhibited a strong positive correlation with patellar length (r = 0.531) and a moderate positive correlation with patellar tendon length (r = 0.408) (

Table 2). No significant correlation was observed between knee range of motion and either patellar length or patellar tendon length. Furthermore, no significant correlations were found between the Insall-Salvati index (ISI) and any other measured outcomes (

Table 2). Additionally, a strong positive correlation was found between participant height and both patellar length (r = 0.448) and patellar tendon length (r = 0.437) (

Table 2). With the exception of the negative correlation between ROM and patellar length (r = -0.090) (

Table 2), all other correlations were positive.

4. Discussion

In this study, we measured the length of the patella and patellar tendon and calculated the Insall-Salvati Index (ISI) by determining the ratio of these two values. This allowed us to assess the height of the patella. We also assessed maximum quadriceps strength, muscle tone and knee joint range of motion. Statistical analysis confirmed significant correlations between patellar height and quadriceps strength and tone.

A statistically significant correlation was found between quadriceps strength and both patellar length and patellar tendon length. The quadriceps muscles converge proximally at the knee, where they attach to the patella via the quadriceps tendon. The patella is in turn attached to the tibia by the patellar tendon, which acts as a distal extension of the quadriceps tendon, running from the patella to the tibial tuberosity [

33]. Previous studies have shown that changes in patellar tendon length, particularly in cases of patella baja, can improve quadriceps strength [

34]. This effect is thought to be due to the mechanical advantage provided by a shortened patellar tendon, which improves force transmission from the quadriceps to the tibia. Consistent with these findings, the present study suggests that an increase in patellar tendon length is associated with greater quadriceps strength. Similarly, quadriceps strength appears to increase as patellar length increases. This is likely to reflect a functional relationship whereby a longer patella improves leverage during knee extension.

A statistically significant correlation was identified between the measured frequency of the rectus femoris muscle and both the length of the patella and the length of the patellar tendon. The contraction of muscle fibres typically results in shortening of the muscle fibres and, consequently, an increase in muscle stiffness. This increase in stiffness is attributed to structural changes in the muscle sarcomeres and connective tissue, a phenomenon that has been well documented in the literature. It has been established through research that there is a positive correlation between muscle stiffness and the degree of muscle shortening that occurs during contraction [

35]. It is hypothesised that as both patellar length and patellar tendon length increase, the quadriceps muscle, including the rectus femoris, undergoes compensatory shortening. This adaptive shortening of muscle fibres results in an increase in muscle stiffness as the muscle is subjected to greater tension. In particular, the rectus femoris demonstrates a pronounced increase in stiffness in comparison to its pre-adaptive state, as it is required to operate more efficiently in order to provide joint stability and facilitate movement [

36]. These findings indicate that alterations in patellar morphology, particularly increased patellar length, and tendon length, may directly impact the mechanical properties of the quadriceps muscle [

37]. This could have implications for joint function, particularly with regard to patellofemoral dynamics, where altered muscle stiffness may affect knee joint stability, movement efficiency and overall lower limb performance.

The results of this study indicate that there was no statistically significant relationship between patellar length or patellar tendon length and knee joint range of motion. Nevertheless, a weak inverse correlation was observed between patellar length and knee range of motion. This indicates that longer patellar lengths may be linked to a minor decrease in knee flexion, although this correlation did not attain statistical significance. This observation is consistent with the findings of previous studies indicating that variations in patellar morphology do not always result in significant changes in joint range of motion [

38]. In the patellofemoral joint, the primary movement during knee flexion is the sliding of the posterior surface of the patella over the femoral trochlea towards the intercondylar notch. The main function of the patella is to act as a biomechanical lever for the quadriceps femoris muscle, thus improving its mechanical advantage by increasing the moment arm. As a consequence, the distance between the muscle's line of tension and the knee joint's axis of rotation is increased. Although the study yielded no significant findings, the observed anatomical and biomechanical interactions underscore the intricate role of the patella in knee function. The increased capacity of the quadriceps to create force enables the patella to facilitate more effective knee extension [

39]. The inverse relationship between patellar length and range of motion observed in this study may be attributed to a reduction in contact area between the patella and the femoral trochlea, particularly the intercondylar notch, during knee flexion. As patellar length increases, the patella may exhibit reduced gliding ability over the femur, which could potentially result in a reduction in the range of motion during knee flexion. This proposition is supported by biomechanical models which suggest that the length and configuration of the patella may impact its kinematic interactions with the femur, thereby influencing the overall flexion angle [

40]. The weak correlation observed in this study suggests that other factors, such as muscle strength, tendon elasticity, or overall joint flexibility, may exert a greater influence on knee range of motion than patellar morphology alone.

In this study, no statistically significant correlation was found between the Insall-Salvati Index (ISI) and quadriceps muscle strength, muscle tone or knee joint range of motion. This is consistent with previous research suggesting that the ISI, although commonly used to assess patellar height, may not be a reliable indicator of quadriceps function or joint mechanics [

41]. Therefore, our results reinforce the idea that changes in patellar height, as measured by the ISI, cannot be used to predict changes in quadriceps strength or knee joint function. The lack of significant correlations in this study highlights the complexity of the factors influencing both patellar height and muscle function. It also highlights the need to include additional variables to assess these relationships more accurately. In addition, our study found significant correlations between both patellar length and patellar tendon length with participant height. These findings are consistent with those of Maozheng Wei et al, who demonstrated a relationship between patellar height and lower limb length [

42]. This anatomical relationship suggests that the lengths of the patella and patellar tendon are influenced by the overall size of the lower limb, particularly the femur and tibia. The patella and patellar tendon function as a functional unit, enabling the transmission of forces from the quadriceps to the tibia. Therefore, their sizes are likely to reflect the growth and proportional development of the femur and tibia during physical maturation [

43]. It is essential to comprehend these anatomical relationships in order to conduct effective clinical assessments and perform appropriate surgical interventions. It is well documented that variations in patellar morphology can influence knee joint biomechanics and patient outcomes, particularly in conditions such as patellofemoral pain syndrome or patellar instability [

44].

This study has several limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, the relatively small sample size may limit the external validity of the findings, and larger, more diverse cohorts are needed to validate the findings and assess their generalizability to different populations. Second, the study focused solely on the relationship between patellar height without considering other potentially relevant factors, such as lower limb length ratio. Future studies should include additional anatomical measurements, such as tibial and femoral lengths, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing patellar morphology and its variation. Finally, the lack of participants with patella alta in this study limited the ability to assess the full spectrum of patellar height variation and its effect on knee function. Future research should include individuals with different patellar heights, including patella alta and patella baja, to better understand how variations in patellar position affect knee biomechanics, quadriceps strength, joint range of motion and overall knee stability.

5. Conclusions

The patellar length and patellar tendon length were significantly correlated with both quadriceps muscle strength and rectus femoris muscle stiffness. Although correlations were observed between patellar height and quadriceps muscle strength as well as muscle tone, the causal relationship between these variables remains unclear. Therefore, it is important to consider the influence of quadriceps muscle strength and muscle tone when addressing abnormalities in patellar height during clinical treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.-H.Z.; methodology, T.-H.K.; software, X.-H.Z. and T.-H.K.; validation, X.-H.Z. and T.-H.K.; formal analysis, X.-H.Z.; investigation, X.-H.Z.; resources, X.-H.Z. and T.-H.K.; data curation, X.-H.Z. and T.-H.K.; writing—original draft preparation, X.-H.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.-H.Z. and T.-H.K.; visualization, X.-H.Z.; supervision, X.-H.Z. and T.-H.K.; project administration, T.-H.K.; funding acquisition, X.-H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Daegu University (IRB No. 1040621-202405-HR-034) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data related to this study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues and the reviewers who provided constructive criticism on drafts of this essay.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ward, S.R.; Powers, C.M. The influence of patella alta on patellofemoral joint stress during normal and fast walking. Clinical biomechanics (Bristol, Avon), 2004, 19, 1040–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanik, J.J.; Guermazi, A.; Zhu, Y.; Zumwalt, A.C.; Gross, K.D.; Clancy, M.; Lynch, J.A.; Segal, N.A.; Lewis, C.E.; Roemer, F.W.; Powers, C.M.; Felson, D.T. Quadriceps weakness, patella alta, and structural features of patellofemoral osteoarthritis. Arthritis care & research, 2011, 63, 1391–1397. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.A.; Helmer, R.; Terk, M.R. Patella alta: lack of correlation between patellotrochlear cartilage congruence and commonly used patellar height ratios. AJR. American journal of roentgenology, 2009, 193, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoller, D.W.; Li, L.E.; Anderson, L.J.; Cannon, W.D. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in orthopaedics and Sports Medicine 3rd ed. In The Knee; Stoller, D.S., Ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gilula, L.A. Diagnosis of Bone and Joint Disorders. 4th ed. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, American Volume, 2003, 85, 184–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulkerson, J.P.; Shea, K.P. Disorders of patellofemoral alignment. The Journal of bone and joint surgery, American volume, 1990, 72, 1424–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Insall, J.; Goldberg, V.; Salvati, E. Recurrent dislocation and the high-riding patella. Clinical orthopaedics and related research, 1972, 88, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulos, L.E.; Rosenberg, T.D.; Drawbert, J.; Manning, J.; Abbott, P. Infrapatellar contracture syndrome. An unrecognized cause of knee stiffness with patella entrapment and patella infera. The American journal of sports medicine, 1987, 15, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colvin, A.C.; West, R.V. Patellar instability. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume, 2008, 90, 2751–2762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tria, A.J., Jr.; Alicea, J.A.; Cody, R.P. Patella baja in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction of the knee. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 1994, 299, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyes, F.R.; Wojtys, E.M.; Marshall, M.T. The early diagnosis and treatment of developmental patella infera syndrome. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 1991, 265, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, P.P.; Del Signore, S.; Perugia, L. Early development of patella infera after knee fractures. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA, 1994, 2, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hockings, M.; Cameron, J.C. Patella baja following chronic quadriceps tendon rupture. The Knee, 2004, 11, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caton, J.; Deschamps, G.; Chambat, P.; Lerat, J.L.; Dejour, H. Les rotules basses. A propos de 128 observations [Patella infera. Apropos of 128 cases]. Revue de chirurgie orthopedique et reparatrice de l'appareil moteur, 1982, 68, 317–325. [Google Scholar]

- Bruhin, V.F.; Preiss, S.; Salzmann, G.M.; Harder, L.P. Frontal Tendon Lengthening Plasty for Treatment of Structural Patella Baja. Arthroscopy techniques, 2016, 5, e1395–e1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weale, A.E.; Murray, D.W.; Newman, J.H.; Ackroyd, C.E. The length of the patellar tendon after unicompartmental and total knee replacement. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume, 1999, 81, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruhin, V.F.; Preiss, S.; Salzmann, G.M.; Harder, L.P. Frontal Tendon Lengthening Plasty for Treatment of Structural Patella Baja. Arthroscopy techniques, 2016, 5, e1395–e1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greiwe, R.M.; Saifim, C.; Ahmad, C.S.; Gardner, T.R. Anatomy and biomechanics of patellar instability. Oper Tech Sports Med, 2010, 18, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, N.; Wakeley, C.; Eldridge, J.D. (vii) Patellofemoral instability. Orthopaedics and Trauma, 2010, 24, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannus, P.A. Long patellar tendon: radiographic sign of patellofemoral pain syndrome--a prospective study. Radiology, 1992, 185, 859–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, E., Jr.; Cameron, J.C. Patella alta and recurrent dislocation of the patella. Clinical orthopaedics and related research 1992, 274, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancourt, J. E. , Cristini, J. A. Patella alta and patella infera: Their etiological role in patellar dislocation, chondromalacia, and apophysitis of the tibial tubercle. The Journal of bone and joint surgery, American volume, 1975, 57, 1112–1115. [Google Scholar]

- Stefanik, J. J. , Zhu, Y., Zumwalt, A. C., Gross, K. D., Clancy, M., Lynch, J. A., Frey Law, L. A., Lewis, C. E., Roemer, F. W., Powers, C. M., Guermazi, A., Felson, D. T. Association between patella alta and the prevalence and worsening of structural features of patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis: the multicenter osteoarthritis study. Arthritis care & research, 2010, 62, 1258–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Endo, Y. , Schweitzer, M. E., Bordalo-Rodrigues, M., Rokito, A. S., Babb, J. S. MRI quantitative morphologic analysis of patellofemoral region: lack of correlation with chondromalacia patellae at surgery. AJR. American journal of roentgenology, 2007, 189, 1165–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, K. E. , Bentley, G. Patella alta and chondromalacia. The Journal of bone and joint surgery, British volume, 1978, 60, 71–73. [Google Scholar]

- Dowd, G.S.; Bentley, G. Radiographic assessment in patellar instability and chondromalacia patellae. The Journal of bone and joint surgery 1986, 68, 297–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, M. Clinical anatomy of the patellofemoral joint. International SportMed Journal, 2001, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kendall, F.P.; MacCreary, E.K.; Provance, P.G. Spieren Tests En Functies, 4e herz ed; Bohn Stafleu van Loghum: Nederland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst, F.V.; van Sambeeck, J.D.P.; Olthuis, G.S.; van der Ree, J.; Koëter, S. Patellar height measurements: Insall-Salvati ratio is most reliable method. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA, 2020, 28, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martins, J.; da Silva, J.R.; da Silva, M.R.B.; Bevilaqua-Grossi, D. Reliability and Validity of the Belt-Stabilized Handheld Dynamometer in Hip- and Knee-Strength Tests. Journal of athletic training, 2017, 52, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hislop, H.; Avers, D.; Brown, M. Daniels and Worthingham's muscle Testing-E-Book: Techniques of manual examination and performance testing; Elsevier Health Sciences, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Portney, L.G.; Watkins, M.P. Foundations of clinical research: applications to practice; Pearson/Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Carreiro, J.E. An osteopathic approach to children. Elsevier Health Sciences 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cristiani, R.; Mikkelsen, C.; Wange, P.; Olsson, D.; Stålman, A.; Engström, B. Autograft type affects muscle strength and hop performance after ACL reconstruction. A randomised controlled trial comparing patellar tendon and hamstring tendon autografts with standard or accelerated rehabilitation. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 2021, 29, 3025–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Huang, C.; Leung, K.L.; Huang, J.; Huang, X.; Fu, S.N. Strength and passive stiffness of the quadriceps are associated with patellar alignment in older adults with knee pain. Clinical Biomechanics, 2023, 110, 106131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ateş, F.; Marquetand, J.; Zimmer, M. Detecting age-related changes in skeletal muscle mechanics using ultrasound shear wave elastography. Scientific reports, 2023, 13, 20062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprague, A.L.; Couppé, C.; Pohlig, R.T.; Cortes, D.C.; Silbernagel, K.G. Relationships between tendon structure and clinical impairments in patients with patellar tendinopathy. Journal of orthopaedic research : official publication of the Orthopaedic Research Society, 2022, 40, 2320–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Marsilio, E.; Cuozzo, F.; Oliva, F.; Eschweiler, J.; Hildebrand, F.; Maffulli, N. Chondral and soft tissue injuries associated to acute patellar dislocation: A systematic review. Life, 2021, 11, 1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, S.L.; Plackis, A.C.; Nuelle, C.W. Patellofemoral anatomy and biomechanics. Clinics in sports medicine, 2014, 33, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, C.M.; Witvrouw, E.; Davis, I.S.; Crossley, K.M. Evidence-based framework for a pathomechanical model of patellofemoral pain: 2017 patellofemoral pain consensus statement from the 4th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, Manchester, UK: part 3. British journal of sports medicine, 2017, 51, 1713–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Analan, P.D.; Ozdemir, H. The effect of patellar height by using Insall Salvati index on pain, function, muscle strength and postural stability in patients with primary knee osteoarthritis. Current Medical Imaging, 2021, 17, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Kang, H.; Hao, K.; Fan, C.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, F. Increased lower limb length ratio in patients with patellar instability. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research, 2023, 18, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, S.; Fischer, B.; Rinner, A.; Hummer, A.; Frank, B.J.H.; Mitterer, J.A.; Huber, S.; Aichmair, A.; Schwarz, G.M.; Hofstaetter, J.G. Body height estimation from automated length measurements on standing long leg radiographs using artificial intelligence. Scientific reports, 2023, 13, 8504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, E.T.; Powers, C.M.; Tanaka, M.J. Update on Patellofemoral Anatomy and Biomechanics. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine, 2023, 31, 151029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).