1. Introduction

Studies of hospital-acquired bloodstream infections (HA-BSIs) have frequently reported BSIs among intensive care unit (ICU) patients but they have not looked at ICU stays during a hospitalization in relation to HA-BSI episodes in general. There are numerous studies on ICU-acquired BSIs [

1], but to our knowledge no study has reported on HA-BSIs acquired before or after an ICU stay. Moreover, few studies on BSI are population-based [

2], and few report long-term outcomes.

A BSI may prompt admission to an ICU. The occurrence or not and the timing of an ICU stay during hospitalization with an HA-BSI may reveal differences in the patient’s disease journey and outcomes. An ICU-acquired BSI may be due to ICU procedures, which may also be the case for BSI detected after an ICU stay. These and other mechanisms can be assessed in population-based studies comprising ICU stays in BSI patients.

There is thus an unmet need to know the impact on the pathogen causing a HA-BSI according to the presence or absence of an ICU stay as well as its occurrence before, during, or after an ICU stay. This knowledge is, amongst others, important for the prescription of empiric antibiotic therapy, mortality, and length of stay.

Consequently, the present study aimed to assess the impact of the BSI diagnosis according to the place and timing of acquisition in the hospital and relation to the presence of an ICU stay, with focus on patient characteristics, short- and long-term prognosis, and distribution of the main microorganisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

The Danish healthcare system is tax-financed and free of charge for individual patients. All BSIs are diagnosed in public hospitals covering geographically well-defined areas. The private hospitals in Denmark mainly perform elective surgery and have no acute admissions.

All Danish residents have a unique personal identification number used in all registries, which enables linkage and long-term follow-up [

3].

2.2. Study population

Our study comprises all adult patients (≥18 years) with HA-BSI, 2009-2016, in Region Zealand and the Region of Southern Denmark [

4].

We retrieved data on all positive blood cultures (BCs) from the laboratory system MADS [

5] and derived BSI episodes from these data [

6]. In brief, a BSI episode was defined as recognized pathogens detected in ≥1 BC set, or common skin contaminants detected in ≥2 BC sets within five days. The date of the HA-BSI was defined as the date where the patient’s first positive BC was sampled.

We included each patient’s first-time BSI episode, which we linked to the Danish National Patient Registry (DNPR) [

7]. The DNPR comprises codes for diagnoses, procedures, and surgery as of 1977.

We computed admissions from dates of admission from home and discharge in the DNPR. We then included all the HA-BSI episodes based on positive BCs sampled two days or later after admission [

6] and retrieved dates of admission to and discharge from an ICU. For each patient, we also computed the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) from 1977 and up to the first–time HA-BSI [

8], with the exclusion of comorbidity diagnosed in the HA-BSI admission.

ICU-acquired HA-BSIs occurred ≥2 days after an ICU admission date and ≤2 days after an ICU discharge date (in-ICU patients). For the remaining admissions with one or more ICU stays, we assessed whether the HA-BSI was acquired before (before-ICU patients) or after (after-ICU patients) the admission’s first ICU stay. Consequently, the remaining patients had no ICU stays during their HA-BSI admission (non-ICU patients).

From the DNPR we further retrieved the following organ support Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee (NOMESCO) codes during the admission’s first ICU stay (before-ICU and after-ICU patients) or in the HA-BSI ICU stay (in-ICU patients): BGDA0* (mechanical ventilation), BGDA1* (non-invasive ventilation), BJFD0* (renal replacement therapy), BFHC92* or BFHC93* or BFHC95* (vasopressor treatment).

We further linked our study database to the Danish Civil Registration System to retrieve data on the vital status as well as dates of death and emigration, if relevant [

9].

The number of ICU-free days was 0 if patients died within 28 days after the ICU admission and it was 28 minus days in the ICU for patients surviving beyond 28 days [

10].

2.3. BC methods

All five departments of clinical microbiology used The BacT/Alert TM BC system (bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France), except Odense University Hospital, which used BACTEC (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) until January 2011. Besides routine isolation procedures, all departments had implemented MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry by 2012.

2.4. Assessments of outcomes

In the present study, the main outcomes, 28- and >28-day mortality, were computed as from the date of sampling the earliest positive BC set that defined the patient’s first BSI episode (i.e., the date of the HA-BSI).

2.5. Statistical analyses

We computed contingency tables of the baseline characteristics, number of ICU stays in the HA-BSI admission, and, for in-ICU patients, in which ICU stay the HA-BSI was acquired.

We computed the number of HA-BSIs per 1000 hospital days among all patients hospitalized in the two regions [

11]. For July 2013-2016, we computed numbers of HA-BSIs per 1000 ICU days, as the Danish Intensive Care Database had no data on ICU days before that [

12].

For the 0-365 day period, we depicted Kaplan-Meier curves. After assessing graphically that the proportional hazard assumptions were fulfilled, we analyzed the 28- and >28-day mortality in Cox’s regression analyses with hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Follow-up ended with death, emigration, the maximum number of days (for 28-day mortality), or 31 December 2019 (for >28-day mortality), whichever came first. We applied a crude model and a model adjusted for days between hospital admission and the HA-BSI (2-4, 5-9, 10-14, 15-19, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, 35-39, 40-44, 45-49, 50-54, 55-59, ≥60 days), age, CCI [

8], sex, and the main group of microorganisms (Gram-negative, Gram-positive, fungi, poly-microbial).

The program Stata®, vs. 17, (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA) was used for all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Study population

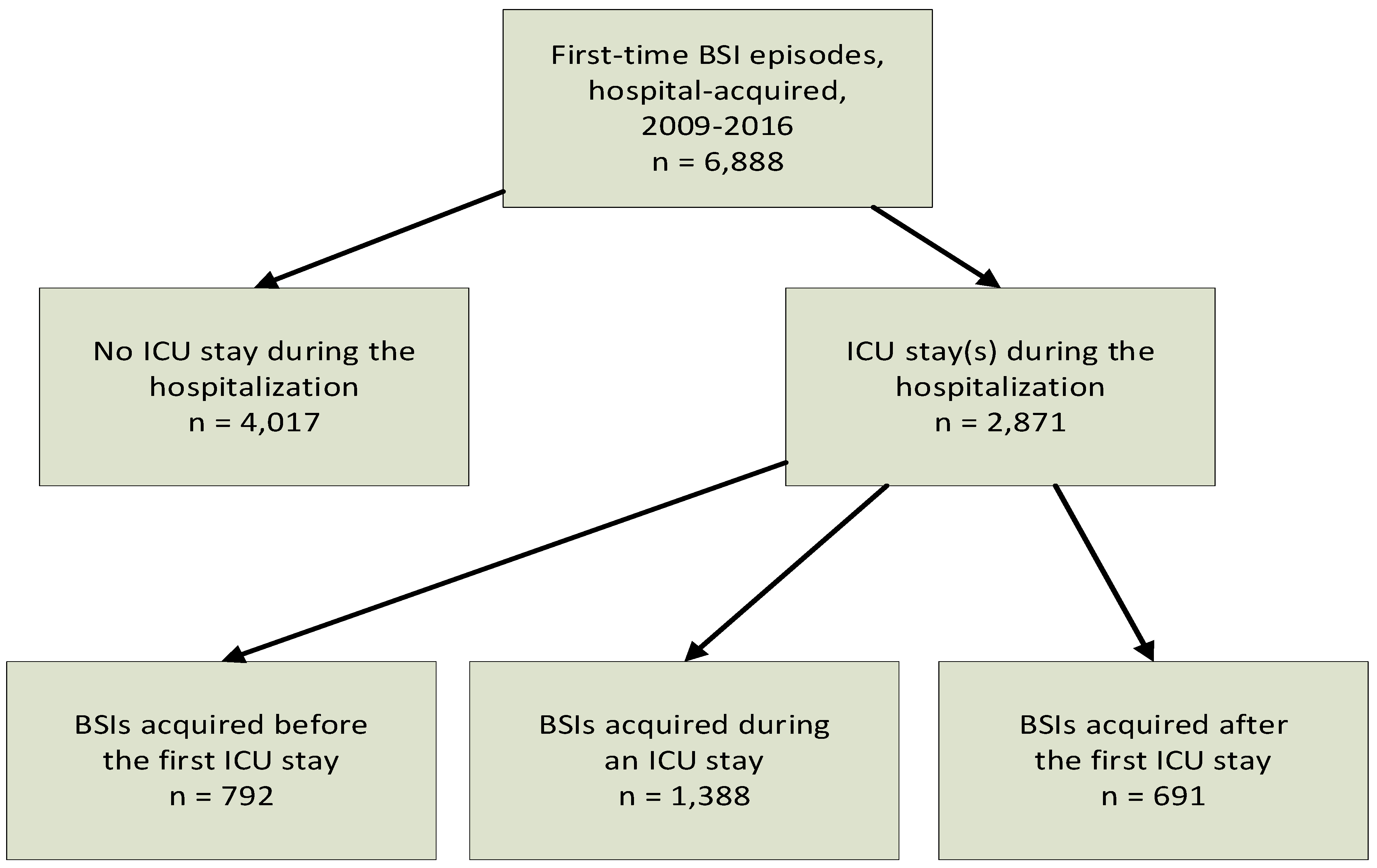

From 2009 through 2016, 6888 adult patients had a first-time HA-BSI episode (

Figure 1); 4017 (58.3%) were non-ICU, 792 (11.5%) before-ICU, 1388 (20.1%) in-ICU, and 691 (10.0%) after-ICU patients.

3.2. General patient characteristics

Percent males increased from 60.8% in non-ICU to 67.9% in after-ICU patients (

Table 1). The trend was the reverse for age, except that the in-ICU patients were the youngest. Non-ICU and before-ICU patients were more comorbid whereas in-ICU patients were the least comorbid.

The picture for individual comorbidities was more heterogeneous, but several (acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, kidney disease, leukemia, lymphoma) followed the general pattern with higher comorbidity in non-ICU and before-ICU patients (Appendix,

Table A1).

3.3. Distribution of microorganisms

The biggest differences between the patient groups were seen for Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Staphylococcus aureus, Coagulase-negative staphylococci (CNS), Enterococci, and fungi (

Table 1). As regards Enterococci, 50.5% of the non-ICU HA-BSIs were E. faecium whereas this was the case for 81.8% of the in-ICU HA-BSIs (Appendix,

Table A2).

3.4. Distribution between ward and ICU days

The percentage of hospital days spent in the ICU was 50.3 for in-ICU patients, 27.8 for before-ICU patients, and 20.9% for after-ICU patients (

Table 1). Days in the ICU for a patient were computed from all ICU stays during the HA-BSI admission (Appendix,

Table A3,

Table A4).

3.5. Incidence of HA-BSIs

The two regions had 6888 HA-BSIs and 11530300 hospital days among adult inpatients, i.e., 0.60 HA-BSIs per 1000 hospital days.

From 1 July 2013 through 2016, the two regions had 1639 non-ICU, 361 before-ICU, 681 in-ICU, and 308 after-ICU patients and 136436 ICU days. This was equivalent to 12.0, 2.6, 5.0, and 2.3 HA-BSI episodes per 1000 ICU days, respectively (21.9 HA-BSI episodes per 1000 ICU days for all 2989 patients).

3.6. Organ supports for patients with an ICU stay

For most parameters, in-ICU patients had the highest levels of organ support followed by before-ICU, and after-ICU patients (Appendix,

Table A5). This trend was generally also seen for the main groups of microorganisms (Appendix,

Table A6).

3.7. Mortality, length of stay, and time from admission to the HA-BSI episode

In-hospital and 28-day mortality were highest in before-ICU patients, followed by in-ICU, non-ICU, and after-ICU patients, ranging from 19% to 45% (

Table 2). Among patients surviving beyond 28 days, the in-ICU patients had the lowest mortality, followed by after-ICU, before-ICU, and non-ICU patients, albeit with a lower range span (56.2-67.1%). Within each patient group, the lowest 28-day mortality was generally seen for Gram-negative HA-BSIs, followed by Gram-positive HA-BSIs, poly-microbial HA-BSIs, and fungemia.

Length of stay (median ranging from 20 to 41 days for all and from 21 to 52 days for patients discharged alive) and time from admission to the HA-BSI (median 7-20 days) differed between the patient groups (

Table 2).

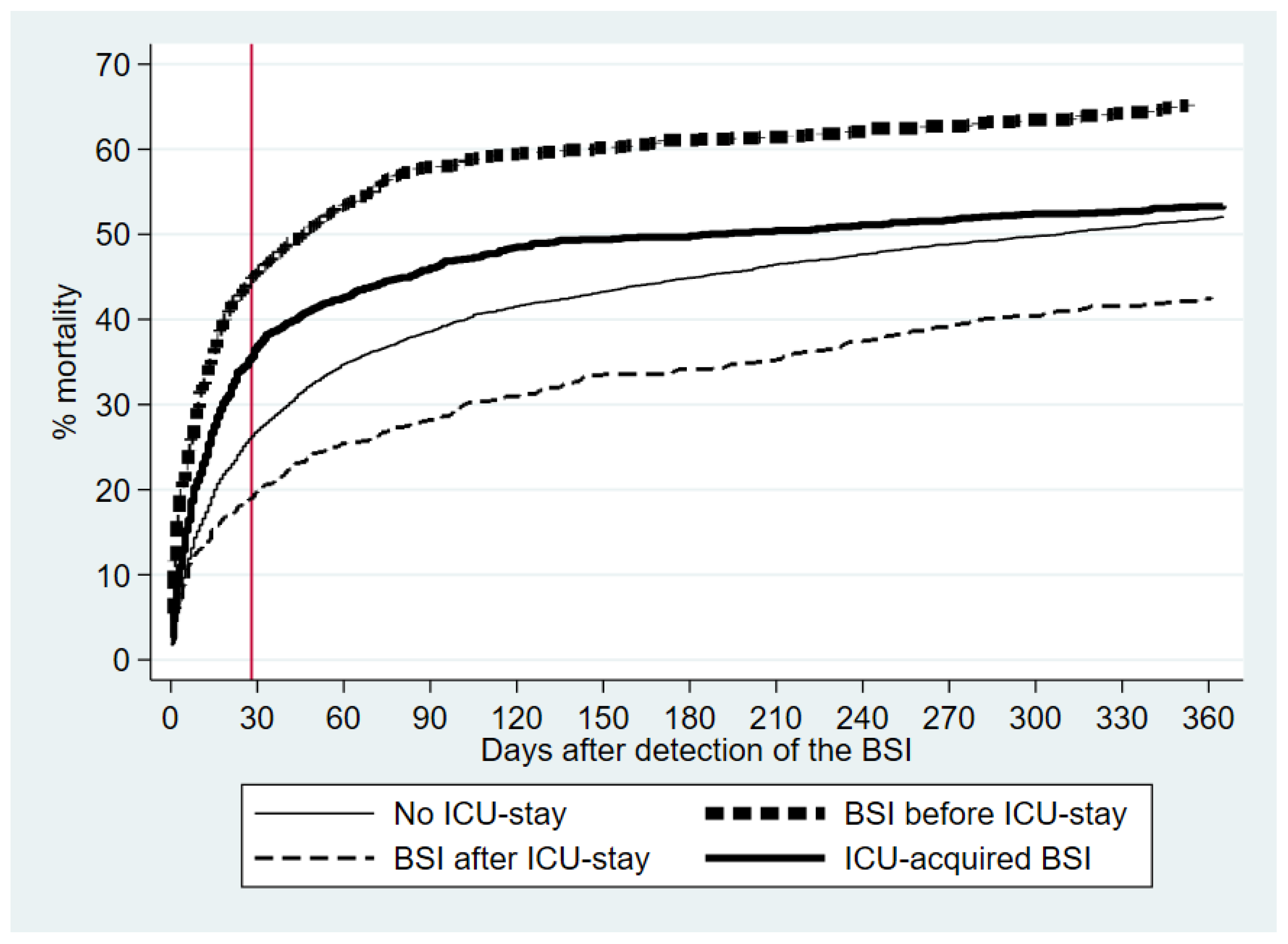

3.8. Kaplan-Meier mortality curves and Cox’s regression analyses

Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier curves for the 0-365 day mortality. After excluding seven patients who emigrated before their HA-BSI admission, the 6881 patients had 17092 follow-up years.

The crude and adjusted Cox’s regression analyses were materially the same (

Table 2). Using non-ICU patients as the reference, before-ICU patients had the highest adjusted 28-day mortality, followed by in-ICU patients. Beyond 28 days, the adjusted HRs were significantly lower for in-ICU and after-ICU patients.

4. Discussion

We found large differences between some common microorganisms and prognosis in relation to the four patient groups. The after-ICU patients had significantly lower 28-day mortality and fewer organ support. Furthermore, they also had rates of several microorganisms that were intermediate between non-ICU and in-ICU patients.

For ICU-acquired BSIs, the 30-day mortality is around 40% [

13], in accordance with our in-ICU patients. We speculate why before-ICU patients had higher short-term mortality than in-ICU patients. One reason may be that BSI in the ICU may be detected earlier due to closer surveillance. Moreover, we suspect that more in-ICU patients had catheter-associated HA-BSI with CNS and

E.

faecium (Appendix,

Table A2), which could be treated more easily by the removal of catheters. This also applied to the after-ICU patients with their high incidence of

S.

aureus, CNS, and Enterococci, of which many are probably also catheter-related. From our experience, most late HA-BSIs are caused by foreign body infections or invasive procedures.

Some of the most important results of this study were the big differences between the distribution of some major microorganisms between the four patient groups, e.g., as seen for

E.

coli,

Klebsiella spp.,

S.

aureus, CNS, Enterococci, and fungi (

Table 1; Appendix,

Table A2). This has direct implications for the choice of empiric antibiotic therapy as regards the occurrence of a HA-BSI in relation to an ICU stay.

In-ICU patients received more organ supports than before-ICU and after-ICU patients did. After-ICU patients also had the lowest 28-day mortality, which may be biased as after-ICU patients are survivors of their first-time ICU stay, but their lower number of organ supports also indicates that they were less severely ill when admitted to the ICU.

Numerous studies have reported on the incidence of BSI in ICU patients, with 0.9% and 1.7% in the two studies having the highest numbers of patients [

14,

15]. Some studies have reported numbers of BSI episodes per 1000 ICU days, of which several reported around 5 [

13,

16,

17,

18], in accordance with our results. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first that has assessed the reverse, i.e., incidence of ICU stays among patients with BSIs.

The after-ICU patients’ HA-BSIs were not a direct cause of their first-time ICU admission, in contrast to what it could possibly be for the before-ICU patients. We do not know the causes of ICU admission from our registry-based data, but the low number of days between the HA-BSI episode and ICU admission (median [inter-quartile range]: 0 [0–2] days; 600/792 [75.8%] with 2 days or less) for our before-ICU patients indicate that the HA-BSI was a direct cause of ICU admission in many instances. In-ICU patients constituted an intermediate group as other infections than BSIs (e.g., pneumonia), may have contributed to their ICU admission. Our study has elucidated that the prognosis, distribution of microorganisms, age, comorbidity, and ICU-related conditions differed considerably in relation to the order and occurrence of the HA-BSIs and ICU stays. Still, as the results from the crude and adjusted analyses were materially the same, the mortality was mainly related to the patient group.

Few population-based BSI studies have reported long-term prognoses [

19,

20]. Beyond day 28, in-ICU patients tended to have lower mortality than non-ICU patients indicating a healthy survival cohort effect among the former.

The EUROBACT2 study included 2028 patients with ICU-acquired HA-BSIs in 52 countries with 333 ICUs [

1]. Although it was not population-based, it is probably the closest that can be compared to our study. A total of 63.5% were males, median time (inter-quartile range) from hospital admission to BSI detection was 13 (8-25) days and 28-day mortality was 37.1%, which is similar to our in-ICU patients with equivalent data of 66.5%, 13 (7-22) days, and 35.6%, respectively. Concerning the distribution of microorganisms, the main differences related to Gram-negative (59.0% in EUROBACT 2, 17.2% in our study) and Gram-positive mono-microbial BSIs (31.1%, 67.4%). Carbapenem resistance in Gram-negative microorganisms in Denmark is quite rare in contrast to the high frequencies found in EUROBACT 2. Other differences relate to our 8-year period vs. EUROBACT2 data collected in a short period, and collection of data from one country in contrast to many countries with more heterogeneous data.

Our study was population-based as patients came from two geographically well-defined regions (2023000 residents, 35% of Danes) [

21]. The national data were highly valid [

7], including ICU-related [

22] and vital status data [

9]. The vital status data enabled the long-term follow-up. The high number of patients enabled robust statistical analyses.

Our study, however, also had limitations. Firstly, we had little clinical data, of which antibiotic treatment, microbial resistance, clinical severity, and source of infection are important. However, clinical severity was partly accounted for by the reported organ support measures. Although resistance is generally low in Denmark [

23], it may have some impact on the results. The broad long-term coverage often provided to patients suspected of sepsis may select Gram-positive microorganisms. In contrast, the use of antibiotics in non-ICU settings is probably more short-term and less broad spectrum, which is less selective for drug-resistant microorganisms. As an example, Enterococci as well as

E.

faecium vs.

E.

faecalis were differently distributed between non-ICU and in-ICU HA-BSIs. Enterococci have high rates of resistance [

24].

E.

faecalis is generally resistant to cephalosporins, whereas

E.

faecium is additionally resistant to penicillins and carbapenems. Secondly, our data are not completely up to date, but we believe this has little impact on the differences between our patient groups and the picture of low antimicrobial resistance and the distribution of microorganisms is virtually unchanged. Thirdly, our data are only valid for Denmark and cannot necessarily be extrapolated to other countries. Finally, immortal time bias may be an important issue. As expected, the median time from admission to the HA-BSI detection differed much between the four patient groups. Adjustment for these periods did not change the results materially and we have shown that the 30-day mortality was around 30-35% regardless of the time between hospital admission and the HA-BSI [

25,

26]. Still, we have not completely elim-inated the impact of immortal time bias, and a caveat for this is warranted in the interpretation of our analyses.

5. Conclusions

Many factors may differ between HA-BSIs in relation to their acquisition in admissions without, before, in, or after ICU stays. BSIs and ICU stays are markers of patients, who are often older and more comorbid, but the order of these events has a considerable impact on the patients’ prognosis, especially in the short term. The better long-term prognosis for in-ICU patients is important from a public health perspective. Knowledge of the incidence of specific microorganisms in the four patient groups is important for the choice of empiric antibiotics and we report novel and original results for after-ICU patients. The latter group of patients had the least organ supports and lower 28-day mortality despite age and comorbidity characteristics similar to the other three patient groups. Our results should be assessed in other countries and settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.O.G. and P.P.; methodology, K.O.G. and P.P.; software, K.O.G.; validation, K.O.G.; formal analysis, K.O.G.; investigation, K.O.G and P.P..; resources, K.O.G.; data curation, K.O.G.; writing—original draft preparation, K.O.G. and P.P.; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, K.O.G.; supervision, P.P.; project administration, K.O.G.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

As the study was registry-based and without patient contact, approval from an ethics committee or consent from participants is not required according to Danish law. However, because microbiology data are legally considered to be medical chart data we needed permission for using these (Danish Patient Safety Authority, rec. no. 3-3013-945/1 & 3-3013-945/2).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Statistics Denmark but legal restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

We thank OPEN, Open Patient Data Explorative Network, Odense University Hospital, Region of Southern Denmark (

http://www.sdu.dk/ki/open), for help with data management and storage on the research server of Statistics Denmark.

Conflicts of Interest

R.B.D.: Advisory board Meeting, Pfizer, September 2022. J.E.C.: Participated in an advisory board and as a speaker at sessions organized by Tillotts Pharma AG. P.P.: Honoraria for lectures and advisory boards from Abionic, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Sanofi, Gilead, Mundipharma, and Pfizer. Other authors: no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Data for individual comorbidities in the four patient groups, diagnosed before the admission with the hospital-acquired bloodstream infection.

Table A1.

Data for individual comorbidities in the four patient groups, diagnosed before the admission with the hospital-acquired bloodstream infection.

| Comorbid disease |

No ICU-stay in hospital admission(n = 4017) |

BSIs acquired before ICU-stay(n = 792) |

ICU-acquiredBSIs(n = 1388) |

BSIs acquired after ICU-stay(n = 691) |

| Acute myocardial infarction |

451 (11.2) |

102 (12.9) |

136 (9.8) |

65 (9.4) |

| Congestive heart failure |

521 (13.0) |

99 (12.5) |

132 (9.5) |

74 (10.7) |

| Peripheral vascular disease |

397 (9.9) |

99 (12.5) |

130 (9.4) |

83 (12.0) |

| Cerebrovascular disease |

673 (16.8) |

136 (17.2) |

193 (13.9) |

95 (13.7) |

| Dementia |

90 (2.2) |

12 (1.5) |

7 (0.5) |

3 (0.4) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease |

586 (14.6) |

134 (16.9) |

222 (16.0) |

89 (12.9) |

| Rheumatic disease |

217 (5.4) |

48 (6.1) |

66 (4.8) |

40 (5.8) |

| (Peptic) Ulcer disease |

373 (9.3) |

96 (12.1) |

119 (8.6) |

54 (7.8) |

| Mild liver disease |

227 (5.7) |

53 (6.7) |

64 (4.6) |

29 (4.2) |

| Diabetes without end-organ damage |

640 (15.9) |

125 (15.8) |

199 (14.3) |

102 (14.8) |

| Hemiplegia, tetraplegia |

22 (0.5) |

9 (1.1) |

20 (1.4) |

4 (0.6) |

| Kidney disease |

403 (10.0) |

87 (11.0) |

85 (6.1) |

45 (6.5) |

| Diabetes with end organ damage |

375 (9.3) |

67 (8.5) |

101 (7.3) |

67 (9.7) |

| Solitary tumor |

1189 (29.6) |

178 (22.5) |

193 (13.9) |

168 (24.3) |

| Leukemia |

148 (3.7) |

21 (2.7) |

20 (1.4) |

9 (1.3) |

| Lymphoma |

198 (4.9) |

40 (5.1) |

29 (2.1) |

20 (2.9) |

| Moderate/severe liver disease |

120 (3.5) |

29 (3.7) |

24 (1.7) |

19 (2.7) |

| Metastatic cancer |

269 (6.7) |

19 (2.4) |

23 (1.7) |

17 (2.5) |

| HIV/AIDS |

3 (0.1) |

2 (0.3) |

4 (0.3) |

2 (0.3) |

Table A2.

Distribution of Enterococcus spp.

Table A2.

Distribution of Enterococcus spp.

| Acquisition of the BSI episode |

Enterococcus species |

Total |

| E. faecalis |

E. faecium |

Other species |

| Without ICU-stay during hospitalization |

176 (46.8) |

190 (50.5) |

10 (2.7) |

376 |

| Before the ICU-stay |

29 (25.2) |

82 (71.3) |

4 (3.5) |

115 |

| In the ICU |

69 (15.5) |

363 (81.8) |

12 (2.7) |

444 |

| After the ICU-stay |

33 (29.7) |

75 (67.6) |

3 (2.7) |

111 |

Table A3.

Distribution of ICU stays for patients with ICU-acquired bloodstream infection (BSI) during admission.

Table A3.

Distribution of ICU stays for patients with ICU-acquired bloodstream infection (BSI) during admission.

| BSI occurred in ICU stay |

Number of ICU stays in admission with the BSI |

Total (%) |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

≥6 |

| 1st |

996 |

169 |

26 |

8 |

1 |

1 |

1201 (86.5) |

| 2nd |

- |

127 |

30 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

161 (11.6) |

| 3rd |

- |

- |

14 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

18 (1.3) |

| 4th |

- |

- |

- |

5 |

1 |

1 |

7 (0.5) |

| 5th |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0 |

1 |

1 (0.1) |

| Total (%) |

996 (71.8) |

296 (21.3) |

70 (5.0) |

18 (1.3) |

4 (0.3) |

4 (0.3) |

1388 (100) |

Table A4.

Numbers of ICU stays for patients with first-time bloodstream infection (BSI) acquired in hospital before or after the admission’s first ICU stay.

Table A4.

Numbers of ICU stays for patients with first-time bloodstream infection (BSI) acquired in hospital before or after the admission’s first ICU stay.

| BSI acquisition in relation to the first ICU stay |

Number of ICU stays in admission with the BSI |

Total (%) |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

| Before |

694 (87.6) |

79 (10.0) |

12 (1.5) |

5 (0.6) |

2 (0.3) |

792 |

| After |

418 (60.5) |

205 (29.7) |

46 (6.7) |

15 (2.2) |

7 (1.0) |

691 |

Table A5.

Organ support statistics for first-time bloodstream infections (BSIs) acquired in the hospital before, after, or in an intensive care unit (ICU) stay.

Table A5.

Organ support statistics for first-time bloodstream infections (BSIs) acquired in the hospital before, after, or in an intensive care unit (ICU) stay.

| Organ support statistic |

BSIs acquired before the ICU-stay(n = 792) |

ICU-acquired BSIs(n = 1388) |

BSIs acquired after the ICU-stay(n = 691) |

| ICU-free days |

|

|

|

| Median (inter-quartile range) |

0 (0-23) |

0 (0-9) |

25 (18-26) |

| Organ support |

|

|

|

| Mechanical ventilation |

429 (54.2)a

|

1197 (86.2) |

304 (44.0) |

| Non-invasive ventilation |

210 (26.5) |

422 (30.4) |

84 (12.2) |

| Renal replacement therapy |

150 (18.9) |

461 (33.4) |

74 (10.7) |

| Vasopressor treatment |

536 (37.7) |

1134 (81.8) |

347 (50.2) |

| Number of organ supports |

|

|

|

| 0 |

136 (17.2) |

80 (5.8) |

226 (32.7) |

| 1 |

211 (26.6) |

157 (11.3) |

203 (29.4) |

| 2 |

254 (32.1) |

545 (39.3) |

192 (27.8) |

| 3 |

158 (20.0) |

457 (32.9) |

58 (8.4) |

| 4 |

33 (4.2) |

149 (10.7) |

12 (1.7) |

Table A6.

Number of bloodstream infection (BSI) episodes with ≥2 organ supports (vs. 0 or 1 organ support) in relation to main microorganism and acquisition before, after, or in an intensive care unit (ICU) stay.

Table A6.

Number of bloodstream infection (BSI) episodes with ≥2 organ supports (vs. 0 or 1 organ support) in relation to main microorganism and acquisition before, after, or in an intensive care unit (ICU) stay.

| Main microorganism |

BSI episodes with ≥2 organ supports/all BSI episodes (%) |

| All |

BSI before the ICU |

BSI in the ICU |

BSI after the ICU |

| Escherichia coli

|

121/266 (45.5) |

70/151 (46.4) |

33/50 (66.0) |

18/65 (27.7) |

| Enterobacter spp. |

56/79 (70.9) |

13/22 (59.1) |

35/37 (94.6) |

8/20 (40.0) |

|

Klebsiella spp. |

65/109 (59.6) |

24/43 (55.8) |

32/36 (88.9) |

9/30 (30.0) |

| Other Enterobacterales |

52/92 (56.5) |

13/25 (52.0) |

26/36 (72.2) |

13/31 (41.9) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa

|

46/78 (59.0) |

17/23 (73.9) |

22/30 (73.3) |

7/25 (28.0) |

| Anaerobic Gram-negative rods |

11/34 (32.4) |

6/15 (40.0) |

3/5 (60.0) |

2/14 (14.3) |

| Other Gram-negative bacteria |

26/34 (76.5) |

5/7 (71.4) |

17/21 (81.0) |

4/6 (66.7) |

| Staphylococcus aureus

|

137/281 (48.8) |

45/102 (44.1) |

46/76 (60.3) |

46/103 (44.7) |

| Coagulase-negative staphylococci |

322/436 (73.9) |

24/47 (51.1) |

247/283 (87.3) |

51/106 (48.1) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae

|

7/15 (46.7) |

3/8 (37.5) |

4/6 (66.7) |

0/1 (0) |

| Hemolytic streptococci |

7/14 (50.0) |

3/7 (42.9) |

2/4 (50.0) |

2/3 (66.7) |

| Enterococci |

502/670 (74.9) |

72/115 (62.6) |

393/444 (88.5) |

37/111 (33.3) |

| Other Gram-positive cocci |

20/32 (62.5) |

10/17 (58.8) |

6/10 (60.0) |

4/5 (80.0) |

| Gram-positive rods |

31/51 (60.8) |

10/21 (47.6) |

14/17 (82.4) |

7/13 (53.9) |

| Fungi |

262/381 (68.8) |

71/94 (75.5) |

158/192 (82.3) |

33/95 (34.7) |

| Poly-microbial |

192/297 (64.7) |

59/94 (62.8) |

112/140 (80.0) |

21/63 (33.3) |

| Gram-negatives |

377/692 (54.5) |

148/286 (51.8) |

168/215 (78.1) |

61/191 (31.9) |

| Gram-positives |

1026/1499 (68.5) |

167/317 (52.7) |

712/840 (84.8) |

147/342 (43.0) |

| Total |

1857/2869 (64.7) |

445/791 (56.3) |

1150/1387 (82.9) |

262/691 (37.9) |

References

- Tabah, A.; Buetti, N.; Staiquly, Q.; Ruckly, S.; Akova, M.; Aslan, A.T.; Leone, M.; Morris, A.C.; Bassetti, M.; Arvaniti, K.; et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of hospital-acquired bloodstream infections in intensive care unit patients: the EUROBACT-2 international cohort study. Intensiv. Care Med. 2023, 49, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laupland, K.B. Incidence of bloodstream infection: a review of population-based studies. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013, 19, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.; Schmidt, S.A.J.; Adelborg, K.; Sundbøll, J.; Laugesen, K.; Ehrenstein, V.; Sørensen, H.T. The Danish health care system and epidemiological research: from health care contacts to database records. Clin. Epidemiology 2019, ume 11, 563–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, P.J.W.; Li, Z.; Aung, A.H.; Coia, J.E.; Chen, M.; Nielsen, S.L.; Jensen, T.G.; Møller, J.K.; Dessau, R.B.; Póvoa, P.; et al. Comparative epidemiology of bacteraemia in two ageing populations: Singapore and Denmark. Epidemiology Infect. 2024, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, J.K. A MICROCOMPUTER-ASSISTED BACTERIOLOGY REPORTING AND INFORMATION SYSTEM. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. Ser. B: Microbiol. 1984, 92B, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horan, T.C.; Andrus, M.; Dudeck, M.A. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care–associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2008, 36, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.; Schmidt, S.A.J.; Sandegaard, J.L.; Ehrenstein, V.; Pedersen, L.; Sørensen, H.T. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin. Epidemiol. 2015, 7, 449–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson, M.E.; Pompei, P.; Ales, K.L.; MacKenzie, C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987, 40, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Pedersen, L.; Sørensen, H.T. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur. J. Epidemiology 2014, 29, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Wendelberger, B.; Gausche-Hill, M.; E Wang, H.; Hansen, M.; Bosson, N.; Lewis, R.J. ICU-free days as a more sensitive primary outcome for clinical trials in critically ill pediatric patients. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2021, 2, e12479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Denmark: Indlæggelser, sengedage og indlagte patienter efter område, alder og køn [https://www.statistikbanken.dk/statbank5a/default.asp?w=1920], accessed January 2023.

- Christiansen, C.F.; Møller, M.H.; Nielsen, H.; Christensen, S. The Danish Intensive Care Database. Clin. Epidemiology 2016, ume 8, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laupland, K.; Kirkpatrick, A.; Church, D.; Ross, T.; Gregson, D. Intensive-care-unit-acquired bloodstream infections in a regional critically ill population. J. Hosp. Infect. 2004, 58, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouel-Cheron, A.; Swihart, B.J.; Warner, S.; Mathew, L.; Strich, J.R.; Mancera, A.; Follmann, D.; Kadri, S.S. Epidemiology of ICU-Onset Bloodstream Infection: Prevalence, Pathogens, and Risk Factors Among 150,948 ICU Patients at 85 U.S. Hospitals*. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 50, 1725–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-C.; Shih, S.-M.; Chen, Y.-T.; Hsiung, C.A.; Kuo, S.-C. Clinical and economic impact of intensive care unit-acquired bloodstream infections in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e037484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laupland, K.B.; Zygun, D.A.; Dele Davies, H.; Church, D.L.; Louie, T.J.; Doig, C.J. Population-based assessment of intensive care unit-acquired bloodstream infections in adults: Incidence, risk factors, and associated mortality rate. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 30, 2462–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adrie, C.; Garrouste-Orgeas, M.; Ibn Essaied, W.; Schwebel, C.; Darmon, M.; Mourvillier, B.; Ruckly, S.; Dumenil, A.-S.; Kallel, H.; Argaud, L.; et al. Attributable mortality of ICU-acquired bloodstream infections: Impact of the source, causative micro-organism, resistance profile and antimicrobial therapy. 2016, 74, 131–141. [CrossRef]

- Civitarese, A.M.; Ruggieri, E.; Walz, J.M.; Mack, D.A.; Heard, S.O.; Mitchell, M.; Lilly, C.M.; Landry, K.E.; Ellison, R.T. A 10-Year Review of Total Hospital-Onset ICU Bloodstream Infections at an Academic Medical Center. Chest 2017, 151, 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.L.; Lassen, A.T.; Gradel, K.O.; Jensen, T.G.; Kolmos, H.J.; Hallas, J.; Pedersen, C. Bacteremia is associated with excess long-term mortality: A 12-year population-based cohort study. J. Infect. 2014, 70, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laupland, K.B.; Svenson, L.W.; Gregson, D.B.; Church, D.L. Long-term mortality associated with community-onset bloodstream infection. Infection 2011, 39, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics, Denmark: Population statistics, Denmark [www.statistikbanken.dk], accessed January 2023.

- Nielsson, M.S.; Blichert-Hansen, L.; Nielsen, R.B.; Christiansen, C. ; Noergaard Validity of the coding for intensive care admission, mechanical ventilation, and acute dialysis in the Danish National Patient Registry: a short report. Clin. Epidemiology 2013, 5, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DANMAP 2021 - Use of antimicrobial agents and occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria from food animals, food and humans in Denmark.

- Pinholt, M.; Østergaard, C.; Arpi, M.; Bruun, N.; Schønheyder, H.; Gradel, K.; Søgaard, M.; Knudsen, J. Incidence, clinical characteristics and 30-day mortality of enterococcal bacteraemia in Denmark 2006–2009: a population-based cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.L.; Lassen, A.T.; Kolmos, H.J.; Jensen, T.G.; Gradel, K.O.; Pedersen, C. The daily risk of bacteremia during hospitalization and associated 30-day mortality evaluated in relation to the traditional classification of bacteremia. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2015, 44, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradel, K.O.; Nielsen, S.L.; Pedersen, C.; Knudsen, J.D.; Østergaard, C.; Arpi, M.; Jensen, T.G.; Kolmos, H.J.; Schønheyder, H.C.; Søgaard, M.; et al. No Specific Time Window Distinguishes between Community-, Healthcare-, and Hospital-Acquired Bacteremia, but They Are Prognostically Robust. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiology 2014, 35, 1474–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).