Submitted:

01 December 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of Synthetic Biology (SynBio) and Metagenomics

2. Tools and Techniques in Synthetic Biology

2.1. Gene Editing Mechanism

2.2. Gene Knockouts and Gene Deletion

2.3. Gene Correction and Insertion

2.4. Genome Editing Tools

2.4.1. Zinc Finger Nucleases

2.4.2. Transcription Activator-like Effector Protein (TALENs)

2.4.3. CRISPR-Cas9

2.4.4. Homing Endonucleases

2.5. Synthetic DNA

2.5.1. Synthetic DNA Using Phosphoramidites

2.5.2. Enzymatic Oligonucleotide Synthesis

2.5.3. Template Independent Synthesis

3. Advancement in Metagenomics

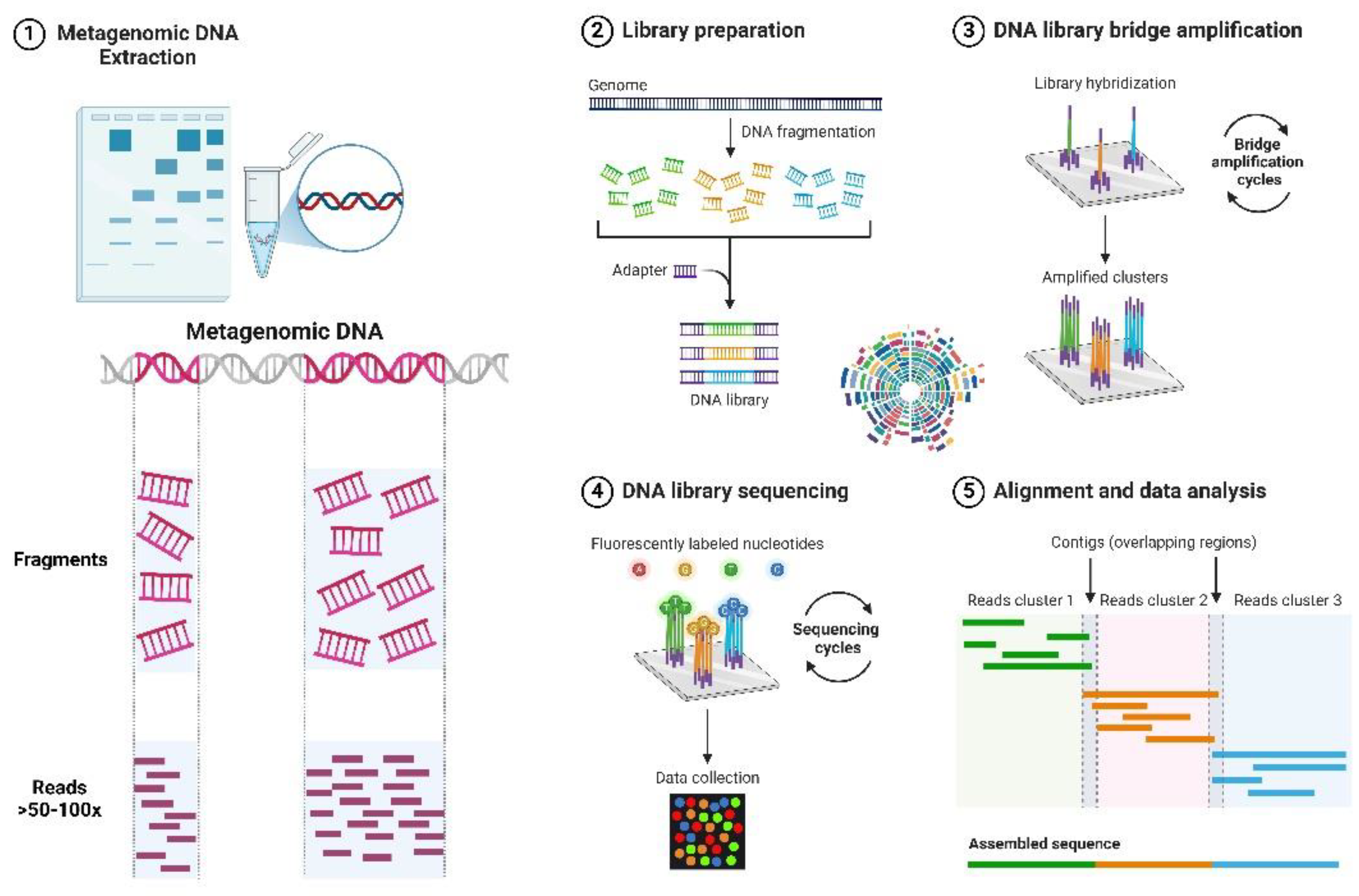

3.1. Metagenomics- Exploring the Microbial World

3.1.1. Extraction of Metagenomic DNA

3.1.2. Metagenome Libraries

3.1.3. Screening of Metagenome Library

3.1.4. Metagenomic Sequencing and Analysis

3.2. Advances in DNA Sequencing Technologies

3.2.1. Illumina Sequencing

3.2.2. Applied Biosystems Sequencer

3.2.3. Ion Torrent Sequencing

3.2.4. Roche 454 Genome Sequencer

3.2.5. PacBio Technology

3.2.6. Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT)

4. Synergistic Benefits of Synthetic Biology and Metagenomics

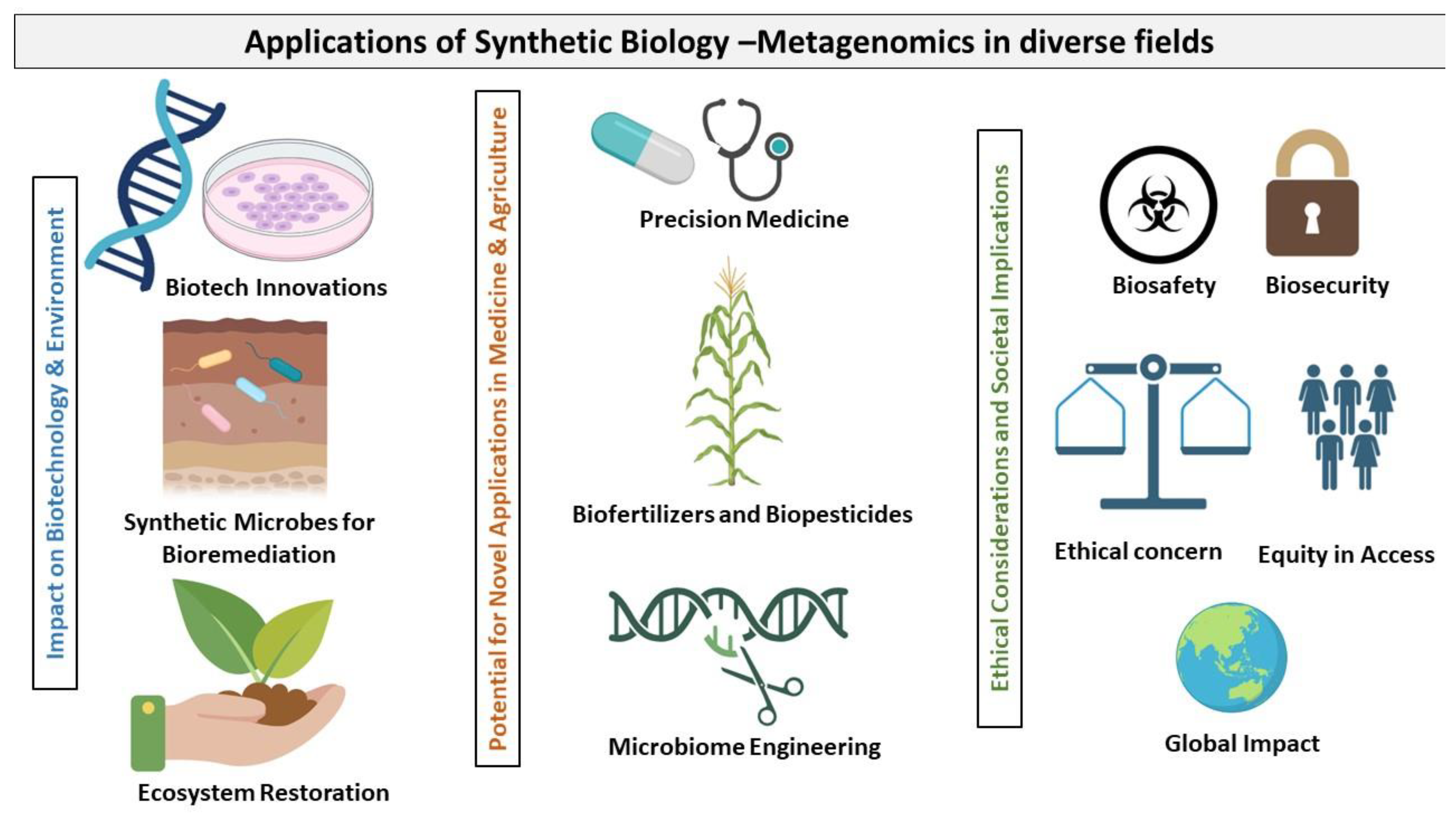

5. Diverse Applications of Synthetic Biology and Metagenomics

5.1. Impact on Biotechnology-Based Research and Development

5.1.1. Synthetic Biology and CRISPR-Cas9

5.1.2. DNA Synthesis

5.1.3. Directed Evolution

5.1.4. Synthetic Cells

5.1.5. Metabolic Engineering

5.1.6. Microbial Biosensing

5.1.7. Therapeutic Applications

5.2. Using Synthetic Microbes to Improve the Environment

5.2.1. Engineered Biofilms for Bioremediation

5.2.2. Ecosystem Restoration

5.2.3. Microbial Consortia Engineering

5.3. Potential for Novel Applications in Medicine and Agriculture

5.3.1. Medicine

5.3.1.1. Microbiome-Based Therapies

5.3.1.2. Antibiotic Resistance Management

5.3.2. Agriculture

5.3.2.1. Engineered Biofertilizers and Biopesticides

5.3.2.2. Crop Microbiome Engineering

5.3.3. Ethical Considerations and Societal Implications

5.3.3.1. Biosafety and Biosecurity

5.3.3.1.1 Unintended Consequences:

5.3.3.1.2 Containment and Control

5.3.3.2. Equity and Access

5.3.3.2.1 Unequal Access to Technologies

5.3.3.2.2 Patents and Ownership

5.3.3.3. Environmental Impact and Sustainability

5.3.3.3.1 Long-Term Ecological Impact

5.3.3.3.2 Sustainability and Environmental Justice

6. Challenges and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nannipieri, P.; Ascher, J.; Ceccherini, M.; Landi, L.; Pietramellara, G.; Renella, G. Microbial diversity and soil functions. European journal of soil science 2017, 68, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Maestre, F.T.; Reich, P.B.; Jeffries, T.C.; Gaitan, J.J.; Encinar, D.; Berdugo, M.; Campbell, C.D.; Singh, B.K. Microbial diversity drives multifunctionality in terrestrial ecosystems. Nature communications 2016, 7, 10541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Pande, V.; Joshi, P. Microbial diversity of aquatic ecosystem and its industrial potential. J. Bacteriol. Mycol. Open Access 2016, 3, 177–179. [Google Scholar]

- Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. nature 2012, 486, 207–214. [CrossRef]

- Ezzamouri, B.; Shoaie, S.; Ledesma-Amaro, R. Synergies of systems biology and synthetic biology in human microbiome studies. Frontiers in microbiology 2021, 12, 681982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Vaca, F.; Anaya-Velázquez, F.; Franco, B. Synthetic biology: Novel approaches for microbiology. Int. Microbiol 2015, 18, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duan, F.F.; Liu, J.H.; March, J.C. Engineered commensal bacteria reprogram intestinal cells into glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells for the treatment of diabetes. Diabetes 2015, 64, 1794–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, M.; Cao, L.; Ning, K. Microbiome big-data mining and applications using single-cell technologies and metagenomics approaches toward precision medicine. Frontiers in Genetics 2019, 10, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Martins, L.; Page, A.J.; Mather, A.E.; Charles, I.G. Taxonomic resolution of the ribosomal RNA operon in bacteria: implications for its use with long-read sequencing. NAR Genomics and Bioinformatics 2020, 2, lqz016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X. An overview of major metagenomic studies on human microbiomes in health and disease. Quantitative Biology 2016, 4, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlino, N.; Blanco-Míguez, A.; Punčochář, M.; Mengoni, C.; Pinto, F.; Tatti, A.; Manghi, P.; Armanini, F.; Avagliano, M.; Barcenilla, C. Unexplored microbial diversity from 2,500 food metagenomes and links with the human microbiome. Cell 2024, 187, 5775–5795. e5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulas, A.; Pavloudi, C.; Polymenakou, P.; Pavlopoulos, G.A.; Papanikolaou, N.; Kotoulas, G.; Arvanitidis, C.; Iliopoulos, l. Metagenomics: tools and insights for analyzing next-generation sequencing data derived from biodiversity studies. Bioinformatics and biology insights 2015, 9, BBI. S12462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roell, G.W.; Zha, J.; Carr, R.R.; Koffas, M.A.; Fong, S.S.; Tang, Y.J. Engineering microbial consortia by division of labor. Microbial cell factories 2019, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, D.B.; Budisa, N. Synthetic biology encompasses metagenomics, ecosystems, and biodiversity sustainability within its scope. Frontiers in Synthetic Biology 2023, 1, 1255472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Wang, B.; Yoshikuni, Y. Microbiome engineering: synthetic biology of plant-associated microbiomes in sustainable agriculture. Trends in Biotechnology 2021, 39, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminian-Dehkordi, J.; Rahimi, S.; Golzar-Ahmadi, M.; Singh, A.; Lopez, J.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Mijakovic, I. Synthetic biology tools for environmental protection. Biotechnology Advances 2023, 108239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J.; Lee, S.-J.; Lee, D.-W. Design and development of synthetic microbial platform cells for bioenergy. Frontiers in microbiology 2013, 4, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Qiao, X.; Mu, R.; Xu, Z.; Yan, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhang, T.; Zhuang, W.-Q. Unravelling biosynthesis and biodegradation potentials of microbial dark matters in hypersaline lakes. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology 2024, 20, 100359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahgu, K.; Choudhary, S.; Kushwaha, T.N.; Shekhar, S.; Tiwari, S.; Sheikh, I.A.; Srivastava, P. Microbes as a promising frontier in drug discovery: A comprehensive exploration of nature's microbial marvels. Acta Botanica Plantae. V02i02 2023, 24, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, W.; Fussenegger, M. The impact of synthetic biology on drug discovery. Drug Discovery Today 2009, 14, 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Bhatia, P.; Chugh, A. Microbial synthetic biology for human therapeutics. Systems and synthetic biology 2012, 6, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seghal Kiran, G.; Ramasamy, P.; Sekar, S.; Ramu, M.; Hassan, S.; Ninawe, A.S.; Selvin, J. Synthetic biology approaches: Towards sustainable exploitation of marine bioactive molecules. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2018, 112, 1278–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leggieri, P.A.; Liu, Y.; Hayes, M.; Connors, B.; Seppälä, S.; O'Malley, M.A.; Venturelli, O.S. Integrating systems and synthetic biology to understand and engineer microbiomes. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering 2021, 23, 169–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, F.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, M.; Sun, F.; Yang, L.; Bi, X.; Lin, Y.; Gao, Y.; Hao, H. Advances in metagenomics and its application in environmental microorganisms. Frontiers in microbiology 2021, 12, 766364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanjal, D.S.; Sharma, D. Microbial metagenomics for industrial and environmental bioprospecting: the unknown envoy. Microbial bioprospecting for sustainable development 2018, 327–352. [Google Scholar]

- Culligan, E.P.; Sleator, R.D.; Marchesi, J.R.; Hill, C. Metagenomics and novel gene discovery: promise and potential for novel therapeutics. Virulence 2014, 5, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glick, B.R. Metabolic load and heterologous gene expression. Biotechnology advances 1995, 13, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brophy, J.A.; Voigt, C.A. Principles of genetic circuit design. Nature methods 2014, 11, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frantz, S. Studies reveal potential pitfalls of RNAi. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2003, 2, 763–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, J.-S. A guide to genome engineering with programmable nucleases. Nature Reviews Genetics 2014, 15, 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaj, T.; Gersbach, C.A.; Barbas, C.F. ZFN, TALEN, and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends in biotechnology 2013, 31, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schatz, M.C.; Phillippy, A.M. The rise of a digital immune system. Gigascience 2012, 1, 2047-2217X-2041-2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; La Russa, M.; Qi, L.S. CRISPR/Cas9 in genome editing and beyond. Annual review of biochemistry 2016, 85, 227–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stark, J.M.; Pierce, A.J.; Oh, J.; Pastink, A.; Jasin, M. Genetic steps of mammalian homologous repair with distinct mutagenic consequences. Molecular and cellular biology 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, G.; Cooke, B.; McColl, K.; Shine, R.; Peacock, T. Modern approaches for the biological control of vertebrate pests: an Australian perspective. Biological control 2010, 52, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharenberg, A.M.; Stoddard, B.L.; Monnat, R.J.; Nolan, A. Retargeting: an unrecognized consideration in endonuclease-based gene drive biology. bioRxiv 2016, 089946. [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard, B.L. Homing endonuclease structure and function. Quarterly reviews of biophysics 2005, 38, 49–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.-G.; Cha, J.; Chandrasegaran, S. Hybrid restriction enzymes: zinc finger fusions to Fok I cleavage domain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1996, 93, 1156–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boch, J.; Scholze, H.; Schornack, S.; Landgraf, A.; Hahn, S.; Kay, S.; Lahaye, T.; Nickstadt, A.; Bonas, U. Breaking the code of DNA binding specificity of TAL-type III effectors. Science 2009, 326, 1509–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Bikard, D.; Cox, D.; Zhang, F.; Marraffini, L.A. RNA-guided editing of bacterial genomes using CRISPR-Cas systems. Nature biotechnology 2013, 31, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Davis, G. Mobile group II intron targeting: applications in prokaryotes and perspectives in eukaryotes. Front Biosci 2007, 12, 4972–4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, K.T.; Li, L.S.; Kim, N.-G.; Kang, H.J.; Koh, K.H.; Chwae, Y.-J.; Kim, K.M.; Kim, Y.K.; Park, S.M.; Jang, S.K. Selective translational repression of truncated proteins from frameshift mutation-derived mRNAs in tumors. PLoS biology 2007, 5, e109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Staahl, B.T.; Alla, R.K.; Doudna, J.A. Enhanced homology-directed human genome engineering by controlled timing of CRISPR/Cas9 delivery. elife 2014, 3, e04766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szostak, J.W.; Orr-Weaver, T.L.; Rothstein, R.J.; Stahl, F.W. The double-strand-break repair model for recombination. Cell 1983, 33, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouet, P.; Smih, F.; Jasin, M. Expression of a site-specific endonuclease stimulates homologous recombination in mammalian cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1994, 91, 6064–6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieber, M.R.; Ma, Y.; Pannicke, U.; Schwarz, K. Mechanism and regulation of human non-homologous DNA end-joining. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2003, 4, 712–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Noyes, M.B.; Zhu, L.J.; Lawson, N.D.; Wolfe, S.A. Targeted gene inactivation in zebrafish using engineered zinc-finger nucleases. Nature biotechnology 2008, 26, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccia, A.; Elledge, S.J. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Molecular cell 2010, 40, 179–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ousterout, D.G.; Perez-Pinera, P.; Thakore, P.I.; Kabadi, A.M.; Brown, M.T.; Qin, X.; Fedrigo, O.; Mouly, V.; Tremblay, J.P.; Gersbach, C.A. Reading frame correction by targeted genome editing restores dystrophin expression in cells from Duchenne muscular dystrophy patients. Molecular Therapy 2013, 21, 1718–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebas, P.; Stein, D.; Tang, W.W.; Frank, I.; Wang, S.Q.; Lee, G.; Spratt, S.K.; Surosky, R.T.; Giedlin, M.A.; Nichol, G. Gene editing of CCR5 in autologous CD4 T cells of persons infected with HIV. New England Journal of Medicine 2014, 370, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Kim, E.; Kim, J.-S. Targeted chromosomal deletions in human cells using zinc finger nucleases. Genome research 2010, 20, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, D.E.; Kamran, S.C.; Lessard, S.; Xu, J.; Fujiwara, Y.; Lin, C.; Shao, Z.; Canver, M.C.; Smith, E.C.; Pinello, L. An erythroid enhancer of BCL11A subject to genetic variation determines fetal hemoglobin level. Science 2013, 342, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choulika, A.; Perrin, A.; Dujon, B.; Nicolas, J.-F. Induction of homologous recombination in mammalian chromosomes by using the I-SceI system of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Molecular and cellular biology 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urnov, F.D.; Miller, J.C.; Lee, Y.-L.; Beausejour, C.M.; Rock, J.M.; Augustus, S.; Jamieson, A.C.; Porteus, M.H.; Gregory, P.D.; Holmes, M.C. Highly efficient endogenous human gene correction using designed zinc-finger nucleases. Nature 2005, 435, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Pruett-Miller, S.M.; Huang, Y.; Gjoka, M.; Duda, K.; Taunton, J.; Collingwood, T.N.; Frodin, M.; Davis, G.D. High-frequency genome editing using ssDNA oligonucleotides with zinc-finger nucleases. Nature methods 2011, 8, 753–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Händel, E.-M.; Gellhaus, K.; Khan, K.; Bednarski, C.; Cornu, T.I.; Müller-Lerch, F.; Kotin, R.M.; Heilbronn, R.; Cathomen, T. Versatile and efficient genome editing in human cells by combining zinc-finger nucleases with adeno-associated viral vectors. Human gene therapy 2012, 23, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina, S.; Von Kalle, C.; Schmidt, M.; McCormack, M.; Wulffraat, N.; Leboulch, P.a.; Lim, A.; Osborne, C.; Pawliuk, R.; Morillon, E. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. science 2003, 302, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moehle, E.A.; Rock, J.M.; Lee, Y.-L.; Jouvenot, Y.; DeKelver, R.C.; Gregory, P.D.; Urnov, F.D.; Holmes, M.C. Targeted gene addition into a specified location in the human genome using designed zinc finger nucleases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, 3055–3060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Haurigot, V.; Doyon, Y.; Li, T.; Wong, S.Y.; Bhagwat, A.S.; Malani, N.; Anguela, X.M.; Sharma, R.; Ivanciu, L. In vivo genome editing restores haemostasis in a mouse model of haemophilia. Nature 2011, 475, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algasaier, S.I.; Exell, J.C.; Bennet, I.A.; Thompson, M.J.; Gotham, V.J.; Shaw, S.J.; Craggs, T.D.; Finger, L.D.; Grasby, J.A. DNA and protein requirements for substrate conformational changes necessary for human flap endonuclease-1-catalyzed reaction. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2016, 291, 8258–8268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tupler, R.; Perini, G.; Green, M.R. Expressing the human genome. Nature 2001, 409, 832–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavletich, N.P.; Pabo, C.O. Zinc finger-DNA recognition: crystal structure of a Zif268-DNA complex at 2.1 Å. Science 1991, 252, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.C.; Holmes, M.C.; Wang, J.; Guschin, D.Y.; Lee, Y.-L.; Rupniewski, I.; Beausejour, C.M.; Waite, A.J.; Wang, N.S.; Kim, K.A. An improved zinc-finger nuclease architecture for highly specific genome editing. Nature biotechnology 2007, 25, 778–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szczepek, M.; Brondani, V.; Büchel, J.; Serrano, L.; Segal, D.J.; Cathomen, T. Structure-based redesign of the dimerization interface reduces the toxicity of zinc-finger nucleases. Nature biotechnology 2007, 25, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gersbach, C.A.; Gaj, T.; Barbas III, C.F. Synthetic zinc finger proteins: the advent of targeted gene regulation and genome modification technologies. Accounts of chemical research 2014, 47, 2309–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didigu, C.A.; Wilen, C.B.; Wang, J.; Duong, J.; Secreto, A.J.; Danet-Desnoyers, G.A.; Riley, J.L.; Gregory, P.D.; June, C.H.; Holmes, M.C. Simultaneous zinc-finger nuclease editing of the HIV coreceptors ccr5 and cxcr4 protects CD4+ T cells from HIV-1 infection. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology 2014, 123, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanayak, V.; Ramirez, C.L.; Joung, J.K.; Liu, D.R. Revealing off-target cleavage specificities of zinc-finger nucleases by in vitro selection. Nature methods 2011, 8, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mino, T.; Mori, T.; Aoyama, Y.; Sera, T. Gene-and protein-delivered zinc finger–staphylococcal nuclease hybrid for inhibition of DNA replication of human papillomavirus. PloS one 2013, 8, e56633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mino, T.; Mori, T.; Aoyama, Y.; Sera, T. Inhibition of DNA replication of human papillomavirus by using zinc finger–single-chain foki dimer hybrid. Molecular biotechnology 2014, 56, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wu, L.P.; Chandrasegaran, S. Functional domains in Fok I restriction endonuclease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1992, 89, 4275–4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porteus, M.H.; Baltimore, D. Chimeric nucleases stimulate gene targeting in human cells. Science 2003, 300, 763–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hockemeyer, D.; Soldner, F.; Beard, C.; Gao, Q.; Mitalipova, M.; DeKelver, R.C.; Katibah, G.E.; Amora, R.; Boydston, E.A.; Zeitler, B. Efficient targeting of expressed and silent genes in human ESCs and iPSCs using zinc-finger nucleases. Nature biotechnology 2009, 27, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.C.; Tan, S.; Qiao, G.; Barlow, K.A.; Wang, J.; Xia, D.F.; Meng, X.; Paschon, D.E.; Leung, E.; Hinkley, S.J. A TALE nuclease architecture for efficient genome editing. Nature biotechnology 2011, 29, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, D.; Yan, C.; Pan, X.; Mahfouz, M.; Wang, J.; Zhu, J.-K.; Shi, Y.; Yan, N. Structural basis for sequence-specific recognition of DNA by TAL effectors. Science 2012, 335, 720–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kweon, J.; Kim, J.-S. TALENs and ZFNs are associated with different mutation signatures. Nature methods 2013, 10, 185–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinstiver, B.P.; Wang, L.; Wolfs, J.M.; Kolaczyk, T.; McDowell, B.; Wang, X.; Schild-Poulter, C.; Bogdanove, A.J.; Edgell, D.R. The I-TevI nuclease and linker domains contribute to the specificity of monomeric TALENs. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics 2014, 4, 1155–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilinger, J.P.; Thompson, D.B.; Liu, D.R. Fusion of catalytically inactive Cas9 to FokI nuclease improves the specificity of genome modification. Nature biotechnology 2014, 32, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cermak, T.; Doyle, E.L.; Christian, M.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Schmidt, C.; Baller, J.A.; Somia, N.V.; Bogdanove, A.J.; Voytas, D.F. Efficient design and assembly of custom TALEN and other TAL effector-based constructs for DNA targeting. Nucleic acids research 2011, 39, e82–e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holkers, M.; Maggio, I.; Liu, J.; Janssen, J.M.; Miselli, F.; Mussolino, C.; Recchia, A.; Cathomen, T.; Goncalves, M.A. Differential integrity of TALE nuclease genes following adenoviral and lentiviral vector gene transfer into human cells. Nucleic acids research 2013, 41, e63–e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Bak, R.O.; Mikkelsen, J.G. Targeted genome editing by lentiviral protein transduction of zinc-finger and TAL-effector nucleases. Elife 2014, 3, e01911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, P.; Barrangou, R. CRISPR/Cas, the immune system of bacteria and archaea. Science 2010, 327, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorek, R.; Lawrence, C.M.; Wiedenheft, B. CRISPR-mediated adaptive immune systems in bacteria and archaea. Annual review of biochemistry 2013, 82, 237–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A programmable dual-RNA–guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. science 2012, 337, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, C.; Niewoehner, O.; Duerst, A.; Jinek, M. Structural basis of PAM-dependent target DNA recognition by the Cas9 endonuclease. Nature 2014, 513, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heigwer, F.; Kerr, G.; Boutros, M. E-CRISP: fast CRISPR target site identification. Nature methods 2014, 11, 122–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Foden, J.A.; Khayter, C.; Maeder, M.L.; Reyon, D.; Joung, J.K.; Sander, J.D. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nature biotechnology 2013, 31, 822–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Sander, J.D.; Reyon, D.; Cascio, V.M.; Joung, J.K. Improving CRISPR-Cas nuclease specificity using truncated guide RNAs. Nature biotechnology 2014, 32, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, K.M.; Pattanayak, V.; Thompson, D.B.; Zuris, J.A.; Liu, D.R. Small molecule–triggered Cas9 protein with improved genome-editing specificity. Nature chemical biology 2015, 11, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumann, K.; Lin, S.; Boyer, E.; Simeonov, D.R.; Subramaniam, M.; Gate, R.E.; Haliburton, G.E.; Ye, C.J.; Bluestone, J.A.; Doudna, J.A. Generation of knock-in primary human T cells using Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 10437–10442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Gaj, T.; Yang, Y.; Wang, N.; Shui, S.; Kim, S.; Kanchiswamy, C.N.; Kim, J.-S.; Barbas III, C.F. Efficient delivery of nuclease proteins for genome editing in human stem cells and primary cells. Nature protocols 2015, 10, 1842–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paix, A.; Folkmann, A.; Rasoloson, D.; Seydoux, G. High efficiency, homology-directed genome editing in Caenorhabditis elegans using CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes. Genetics 2015, 201, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ménoret, S.; De Cian, A.; Tesson, L.; Remy, S.; Usal, C.; Boulé, J.-B.; Boix, C.; Fontanière, S.; Crénéguy, A.; Nguyen, T.H. Homology-directed repair in rodent zygotes using Cas9 and TALEN engineered proteins. Scientific reports 2015, 5, 14410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahdar, M.; McMahon, M.A.; Prakash, T.P.; Swayze, E.E.; Bennett, C.F.; Cleveland, D.W. Synthetic CRISPR RNA-Cas9–guided genome editing in human cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, E7110–E7117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullineux, S.-T.; Costa, M.; Bassi, G.S.; Michel, F.; Hausner, G. A group II intron encodes a functional LAGLIDADG homing endonuclease and self-splices under moderate temperature and ionic conditions. Rna 2010, 16, 1818–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugen, P.; Bhattacharya, D. The spread of LAGLIDADG homing endonuclease genes in rDNA. Nucleic acids research 2004, 32, 2049–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moure, C.M.; Gimble, F.S.; Quiocho, F.A. Crystal structure of the intein homing endonuclease PI-Sce I bound to its recognition sequence. Nature structural biology 2002, 9, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, G.; Kenny, C.; Fagan, A.; Kurischko, C.; Gaillardin, C.; Wolfe, K.H. Evolution of the MAT locus and its Ho endonuclease in yeast species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101, 1632–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunin-Horkawicz, S.; Feder, M.; Bujnicki, J.M. Phylogenomic analysis of the GIY-YIG nuclease superfamily. BMC genomics 2006, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascales, E.; Buchanan, S.K.; Duché, D.; Kleanthous, C.; Lloubes, R.; Postle, K.; Riley, M.; Slatin, S.; Cavard, D. Colicin biology. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews 2007, 71, 158–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambowitz, A.M.; Zimmerly, S. Mobile group II introns. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2004, 38, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosuri, S.; Church, G.M. Large-scale de novo DNA synthesis: technologies and applications. Nature methods 2014, 11, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.; Berdis, A.J. Non-natural nucleotides as probes for the mechanism and fidelity of DNA polymerases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Proteins and Proteomics 2010, 1804, 1064–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cong, L.; Ran, F.A.; Cox, D.; Lin, S.; Barretto, R.; Habib, N.; Hsu, P.D.; Wu, X.; Jiang, W.; Marraffini, L.A. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 2013, 339, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ran, F.; Hsu, P.D.; Wright, J.; Agarwala, V.; Scott, D.A.; Zhang, F. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nature protocols 2013, 8, 2281–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohsen, M.G.; Kool, E.T. The discovery of rolling circle amplification and rolling circle transcription. Accounts of chemical research 2016, 49, 2540–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stemmer, W.P.; Crameri, A.; Ha, K.D.; Brennan, T.M.; Heyneker, H.L. Single-step assembly of a gene and entire plasmid from large numbers of oligodeoxyribonucleotides. Gene 1995, 164, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarac, I.; Hollenstein, M. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase in the synthesis and modification of nucleic acids. ChemBioChem 2019, 20, 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruthers, M.; Barone, A.; Beaucage, S.; Dodds, D.; Fisher, E.; McBride, L.; Matteucci, M.; Stabinsky, Z.; Tang, J.-Y. [15] Chemical synthesis of deoxyoligonucleotides by the phosphoramidite method. In Methods in enzymology; Elsevier, 1987; Volume 154, pp. 287–313. [Google Scholar]

- Caruthers, M.H. The chemical synthesis of DNA/RNA: our gift to science. Journal of biological chemistry 2013, 288, 1420–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeProust, E.M.; Peck, B.J.; Spirin, K.; McCuen, H.B.; Moore, B.; Namsaraev, E.; Caruthers, M.H. Synthesis of high-quality libraries of long (150mer) oligonucleotides by a novel depurination controlled process. Nucleic acids research 2010, 38, 2522–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, M.A.; Kilian, K.; Wang, Y.; Bradshaw, J.; Cavet, G.; Ge, W.; Kulkarni, A.; Paddison, P.J.; Chang, K.; Sheth, N. Production of complex nucleic acid libraries using highly parallel in situ oligonucleotide synthesis. Nature methods 2004, 1, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneziano, R.; Shepherd, T.R.; Ratanalert, S.; Bellou, L.; Tao, C.; Bathe, M. In vitro synthesis of gene-length single-stranded DNA. Scientific reports 2018, 8, 6548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.A.; Davis, R.W. Template-independent enzymatic oligonucleotide synthesis (TiEOS): its history, prospects, and challenges. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 1821–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulé, J.-B.; Rougeon, F.; Papanicolaou, C. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase indiscriminately incorporates ribonucleotides and deoxyribonucleotides. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 31388–31393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoose, A.; Vellacott, R.; Storch, M.; Freemont, P.S.; Ryadnov, M.G. DNA synthesis technologies to close the gene writing gap. Nature Reviews Chemistry 2023, 7, 144–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftie-Eaton, W.; Heinisch, T.; Soskine, M.; Champion, E.; Godron, X.; Ybert, T. Novel Variants of Endonuclease V and Uses Thereof. 2023.

- Motea, E.A.; Berdis, A.J. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase: the story of a misguided DNA polymerase. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Proteins and Proteomics 2010, 1804, 1151–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breitwieser, F.P.; Lu, J.; Salzberg, S.L. A review of methods and databases for metagenomic classification and assembly. Briefings in bioinformatics 2019, 20, 1125–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakirde, K.S.; Wild, J.; Godiska, R.; Mead, D.A.; Wiggins, A.G.; Goodman, R.M.; Szybalski, W.; Liles, M.R. Gram negative shuttle BAC vector for heterologous expression of metagenomic libraries. Gene 2011, 475, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, T.; Gilbert, J.; Meyer, F. Metagenomics-a guide from sampling to data analysis. Microbial informatics and experimentation 2012, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glenn, T.C. Field guide to next-generation DNA sequencers. Molecular ecology resources 2011, 11, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Li, S.; Hu, N.; He, Y.; Pong, R.; Lin, D.; Lu, L.; Law, M. Comparison of next-generation sequencing systems. BioMed research international 2012, 2012, 251364. [Google Scholar]

- Fantini, E.; Gianese, G.; Giuliano, G.; Fiore, A. Bacterial metabarcoding by 16S rRNA gene ion torrent amplicon sequencing. Bacterial Pangenomics: Methods and Protocols 2015, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, V. Method of the year: long-read sequencing. Nature Methods 2023, 20, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Q.; Zhang, S.; Xie, Q.; Wang, W.; Lin, Z.; Wang, H.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, Q. De Novo Transcriptome Analysis by PacBio SMRT-Seq and Illumina RNA-Seq Provides New Insights into Polyphenol Biosynthesis in Chinese Olive Fruit. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, N.; Ng, W.; Thao, K.; Agulto, R.; Weis, A.; Kim, K.S.; Korlach, J.; Hickey, L.; Kelly, L.; Lappin, S. Automation of PacBio SMRTbell NGS library preparation for bacterial genome sequencing. Standards in genomic sciences 2017, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuber, P.; Chooneea, D.; Geeves, C.; Salatino, S.; Creedy, T.J.; Griffin, C.; Sivess, L.; Barnes, I.; Price, B.; Misra, R. Comparing the accuracy and efficiency of third generation sequencing technologies, Oxford Nanopore Technologies, and Pacific Biosciences, for DNA barcode sequencing applications. Ecological Genetics and Genomics 2023, 28, 100181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Luo, H.; Wang, Z.; Lam, H.-M.; Huang, C. Oxford Nanopore Technology: revolutionizing genomics research in plants. Trends in Plant Science 2022, 27, 510–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, M.; Fiddes, I.T.; Miga, K.H.; Olsen, H.E.; Paten, B.; Akeson, M. Improved data analysis for the MinION nanopore sequencer. Nature methods 2015, 12, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greninger, A.L.; Naccache, S.N.; Federman, S.; Yu, G.; Mbala, P.; Bres, V.; Stryke, D.; Bouquet, J.; Somasekar, S.; Linnen, J.M. Rapid metagenomic identification of viral pathogens in clinical samples by real-time nanopore sequencing analysis. Genome medicine 2015, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, C.; Luo, Y. Recent advances in silent gene cluster activation in Streptomyces. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2021, 9, 632230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blin, K.; Shaw, S.; Augustijn, H.E.; Reitz, Z.L.; Biermann, F.; Alanjary, M.; Fetter, A.; Terlouw, B.R.; Metcalf, W.W.; Helfrich, E.J. antiSMASH 7.0: new and improved predictions for detection, regulation, chemical structures and visualisation. Nucleic acids research 2023, 51, W46–W50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mózsik, L.; Iacovelli, R.; Bovenberg, R.A.; Driessen, A.J. Transcriptional activation of biosynthetic gene clusters in filamentous fungi. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2022, 10, 901037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, G.D.; Stasulli, N.M. Employing synthetic biology to expand antibiotic discovery. SLAS technology 2024, 29, 100120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Song, Y.; Xie, X.; Zhu, Z.; Duan, C.; Nong, C.; Wang, H.; Bao, R. Synthetic biology-inspired cell engineering in diagnosis, treatment, and drug development. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Moore, B.S.; Yoon, Y.J. Reinvigorating natural product combinatorial biosynthesis with synthetic biology. Nature chemical biology 2015, 11, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiamis, G.; Cherif, A.; Karpouzas, D.; Ntougias, S. Microbial diversity for biotechnology 2014. BioMed Research International 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, C.A. Synthetic biology. 2012, 1, 1-2.

- Katz, L.; Chen, Y.Y.; Gonzalez, R.; Peterson, T.C.; Zhao, H.; Baltz, R.H. Synthetic biology advances and applications in the biotechnology industry: a perspective. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology 2018, 45, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-H.P.; Sun, J.; Ma, Y. Biomanufacturing: history and perspective. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology 2017, 44, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, L.M.; Cotter, P.D.; Hill, C.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A. Biotechnological applications of functional metagenomics in the food and pharmaceutical industries. Frontiers in microbiology 2015, 6, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endy, D. Foundations for engineering biology. Nature 2005, 438, 449–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, R.W.; Buck, M.; Wang, B. Tools and principles for microbial gene circuit engineering. Journal of Molecular Biology 2016, 428, 862–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.M.; Arndt, K.M. Standardization in synthetic biology. Synthetic gene networks: methods and protocols 2012, 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bouhajja, E.; Agathos, S.N.; George, I.F. Metagenomics: probing pollutant fate in natural and engineered ecosystems. Biotechnology advances 2016, 34, 1413–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.-H.; Tang, S.-L. Marine microbial metagenomics: from individual to the environment. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2014, 15, 8878–8892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, S.L.; Piel, J.; Sunagawa, S. A roadmap for metagenomic enzyme discovery. Natural Product Reports 2021, 38, 1994–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, F.; Ellis, T. The second decade of synthetic biology: 2010–2020. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 5174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Huang, C.; Chen, J. The application of CRISPR/Cas mediated gene editing in synthetic biology: Challenges and optimizations. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2022, 10, 890155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsberg, K.J.; Bhatt, I.V.; Schmidtke, D.T.; Javanmardi, K.; Dillard, K.E.; Stoddard, B.L.; Finkelstein, I.J.; Kaiser, B.K.; Malik, H.S. Functional metagenomics-guided discovery of potent Cas9 inhibitors in the human microbiome. elife 2019, 8, e46540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.A.; Ellington, A.D. Synthetic DNA synthesis and assembly: putting the synthetic in synthetic biology. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2017, 9, a023812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Yin, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.-Z. Metagenomic sequencing-driven multidisciplinary approaches to shed light on the untapped microbial natural products. Drug Discovery Today 2022, 27, 730–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, D.L. Synthetic Biology, Directed Evolution, and the Rational Design of New Cardiovascular Therapeutics: Are We There Yet? 2023, 8, 905–906. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Suenaga, H. Targeted metagenomics unveils the molecular basis for adaptive evolution of enzymes to their environment. Frontiers in microbiology 2015, 6, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunjal, A.; Gupta, S.; Nweze, J.E.; Nweze, J.A. Metagenomics in bioremediation: Recent advances, challenges, and perspectives. Metagenomics to Bioremediation 2023, 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- García-Granados, R.; Lerma-Escalera, J.A.; Morones-Ramírez, J.R. Metabolic engineering and synthetic biology: synergies, future, and challenges. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology 2019, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, S.; Shukla, P. Alternative strategies for microbial remediation of pollutants via synthetic biology. Frontiers in microbiology 2020, 11, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Kumar, V.; Dhanjal, D.S.; Datta, S.; Prasad, R.; Singh, J. Biological biosensors for monitoring and diagnosis. Microbial biotechnology: basic research and applications 2020, 317–335. [Google Scholar]

- Bharti, A.; Jain, U.; Chauhan, N. From Lab to Field: Nano-Biosensors for Real-time Plant Nutrient Tracking. Plant Nano Biology 2024, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanniche, I.; Behkam, B. Engineered live bacteria as disease detection and diagnosis tools. Journal of Biological Engineering 2023, 17, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque, E.; Udaondo, Z.; Molina, L.; de la Torre, J.; Godoy, P.; Ramos, J.L. Providing octane degradation capability to Pseudomonas putida KT2440 through the horizontal acquisition of oct genes located on an integrative and conjugative element. Environmental Microbiology Reports 2022, 14, 934–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Chen, J.; Dharmasiddhi, I.P.W.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H. Review of the Potential of Probiotics in Disease Treatment: Mechanisms, Engineering, and Applications. Processes 2024, 12, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, E.J.; Robinson, A.B.; Süel, G.r.M. Engineered E. coli that detect and respond to gut inflammation through nitric oxide sensing. ACS synthetic biology 2012, 1, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riglar, D.T.; Silver, P.A. Engineering bacteria for diagnostic and therapeutic applications. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2018, 16, 214–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdizade Ari, M.; Dadgar, L.; Elahi, Z.; Ghanavati, R.; Taheri, B. Genetically engineered microorganisms and their impact on human health. International Journal of Clinical Practice 2024, 2024, 6638269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rylott, E.L.; Bruce, N.C. How synthetic biology can help bioremediation. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 2020, 58, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermakova, M.; Danila, F.R.; Furbank, R.T.; von Caemmerer, S. On the road to C4 rice: advances and perspectives. The Plant Journal 2020, 101, 940–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giachino, A.; Focarelli, F.; Marles-Wright, J.; Waldron, K.J. Synthetic biology approaches to copper remediation: bioleaching, accumulation and recycling. FEMS microbiology ecology 2021, 97, fiaa249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangi, A.K.; Sharma, B.; Hill, R.T.; Shukla, P. Bioremediation through microbes: systems biology and metabolic engineering approach. Critical reviews in biotechnology 2019, 39, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skariyachan, S.; Taskeen, N.; Kishore, A.P.; Krishna, B.V.; Naidu, G. Novel consortia of Enterobacter and Pseudomonas formulated from cow dung exhibited enhanced biodegradation of polyethylene and polypropylene. Journal of environmental management 2021, 284, 112030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizimana Rukundo, T. Ecological Restoration Using Synthetic Biology.

- Haque, E.; Bin Riyaz, M.A.; Shankar, S.; Hassan, S. Compositional Characterization of Biosurfactant Produced from Pseudomonas aeruginosa ENO14-MH271625 and its Application in Crude Oil Bioremediation. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Investigation 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Yao, H.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y. Microplastic addition alters the microbial community structure and stimulates soil carbon dioxide emissions in vegetable-growing soil. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 2021, 40, 352–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.C.; Henk, D.A.; Briggs, C.J.; Brownstein, J.S.; Madoff, L.C.; McCraw, S.L.; Gurr, S.J. Emerging fungal threats to animal, plant and ecosystem health. Nature 2012, 484, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncker, K.E.; Holmes, Z.A.; You, L. Engineered microbial consortia: strategies and applications. Microbial Cell Factories 2021, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vo, T.P.; Danaee, S.; Chaiwong, C.; Pham, B.T.; Kim, M.; Kuzhiumparambil, U.; Songsomboon, C.; Pernice, M.; Ngo, H.H.; Ralph, P.J. Microalgae-bacteria consortia for organic pollutants remediation from wastewater: A critical review. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2024, 114213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zitvogel, L.; Ma, Y.; Raoult, D.; Kroemer, G.; Gajewski, T.F. The microbiome in cancer immunotherapy: Diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies. Science 2018, 359, 1366–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazar, V.; Ditu, L.-M.; Pircalabioru, G.G.; Picu, A.; Petcu, L.; Cucu, N.; Chifiriuc, M.C. Gut microbiota, host organism, and diet trialogue in diabetes and obesity. Frontiers in nutrition 2019, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffie, C.G.; Pamer, E.G. Microbiota-mediated colonization resistance against intestinal pathogens. Nature Reviews Immunology 2013, 13, 790–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, J.; Li, Y.; Cai, Z.; Li, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, F.; Liang, S.; Zhang, W.; Guan, Y.; Shen, D. A metagenome-wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. nature 2012, 490, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Control, C.f.D.; Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019; US Department of Health and Human Services, Centres for Disease Control and …: 2019.

- Dang, C.; Xia, Y.; Zheng, M.; Liu, T.; Liu, W.; Chen, Q.; Ni, J. Metagenomic insights into the profile of antibiotic resistomes in a large drinking water reservoir. Environment International 2020, 136, 105449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javed, M.U.; Hayat, M.T.; Mukhtar, H.; Imre, K. CRISPR-Cas9 system: A prospective pathway toward combatting antibiotic resistance. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffler, C.; Gibson, K.M.; Martin, L.; Chang, L.; Rotman, J.; Toma, I.V.; Mason, C.E.; Eskin, E.; Zackular, J.P.; Crandall, K.A. Metagenomics for clinical diagnostics: technologies and informatics. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1911.11304 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Durão, P.; Balbontín, R.; Gordo, I. Evolutionary mechanisms shaping the maintenance of antibiotic resistance. Trends in microbiology 2018, 26, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Wang, W.; Yuan, Z.; Sederoff, R.R.; Sederoff, H.; Chiang, V.L.; Borriss, R. Microbial interactions within multiple-strain biological control agents impact soil-borne plant disease. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11, 585404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panke-Buisse, K.; Poole, A.C.; Goodrich, J.K.; Ley, R.E.; Kao-Kniffin, J. Selection on soil microbiomes reveals reproducible impacts on plant function. The ISME journal 2015, 9, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Clark, B.; Kuznesof, S.; Lin, X.; Frewer, L.J. Synthetic biology applied in the agrifood sector: Public perceptions, attitudes and implications for future studies. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2019, 91, 454–466. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, G.; Raaijmakers, J.M. Saving seed microbiomes. The ISME journal 2018, 12, 1167–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, P.; Lakshmanan, V.; Labbé, J.L.; Craven, K.D. Microbe to microbiome: a paradigm shift in the application of microorganisms for sustainable agriculture. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11, 622926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naylor, D.; Coleman-Derr, D. Drought stress and root-associated bacterial communities. Frontiers in plant science 2018, 8, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, F.; Christou, A.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Vila-Costa, M.; Bayona, J.M.; Pina, B. Effects of prescription antibiotics on soil-and root-associated microbiomes and resistomes in an agricultural context. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2020, 400, 123208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, O.; Stan, G.-B.; Ellis, T. Building-in biosafety for synthetic biology. Microbiology 2013, 159, 1221–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquier, E.F.; van de Wouw, M.; Nekrasov, E.; Contractor, N.; Kassis, A.; Marcu, D. Local and Systemic Effects of Bioactive Food Ingredients: Is There a Role for Functional Foods to Prime the Gut for Resilience? Foods 2024, 13, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.H.; Kumar, V.; Khare, T.; Guddimalli, R.; Parveda, M.; Solymosi, K.; Suprasanna, P.; Kavi Kishor, P. Engineering salinity tolerance in plants: progress and prospects. Planta 2020, 251, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasanoff, S. Technologies of humility: Citizen participation in governing science; Springer, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Keiper, F.; Atanassova, A. Regulation of synthetic biology: developments under the convention on biological diversity and its protocols. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology 2020, 8, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, G.; Grube, M.; Schloter, M.; Smalla, K. The plant microbiome and its importance for plant and human health. 2014, 5, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohua, L.; Yuexin, W.; Yakun, O.; Kunlan, Z.; Huan, L.; Ruipeng, L. Ethical framework on risk governance of synthetic biology. Journal of Biosafety and Biosecurity 2023, 5, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarelle, V.; Roldán, D.M.; Fabiano, E.; Guazzaroni, M.-E. Synthetic biology toolbox for antarctic Pseudomonas sp. strains: toward a psychrophilic nonmodel chassis for function-driven metagenomics. ACS Synthetic Biology 2023, 12, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, B.J.; Brown, S.D.; Siguenza, N.; Mai, I.; Saran, A.R.; Lingaraju, A.; Maissy, E.S.; Machado, A.C.D.; Pinto, A.F.; Sanchez, C. Intestinal transgene delivery with native E. coli chassis allows persistent physiological changes. Cell 2022, 185, 3263–3277. e3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belda, I.; Williams, T.C.; de Celis, M.; Paulsen, I.T.; Pretorius, I.S. Seeding the idea of encapsulating a representative synthetic metagenome in a single yeast cell. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Dai, G.; Zhang, Y.; Bian, X. Microbial chassis engineering drives heterologous production of complex secondary metabolites. Biotechnology Advances 2022, 59, 107966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Moon, C.D.; Zheng, N.; Huws, S.; Zhao, S.; Wang, J. Opportunities and challenges of using metagenomic data to bring uncultured microbes into cultivation. Microbiome 2022, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavy, A.; Keren, R.; Haber, M.; Schwartz, I.; Ilan, M. Implementing sponge physiological and genomic information to enhance the diversity of its culturable associated bacteria. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2014, 87, 486–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M., *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Nishikawa, Y.; Ide, K.; Sakanashi, C.; Takahashi, K.; Takeyama, H. Single-cell genomics of uncultured bacteria reveals dietary fiber responders in the mouse gut microbiota. Microbiome 2020, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).