Submitted:

29 November 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Analysis

"Stress; Capability of not coping up with what’s going on around you."

Results

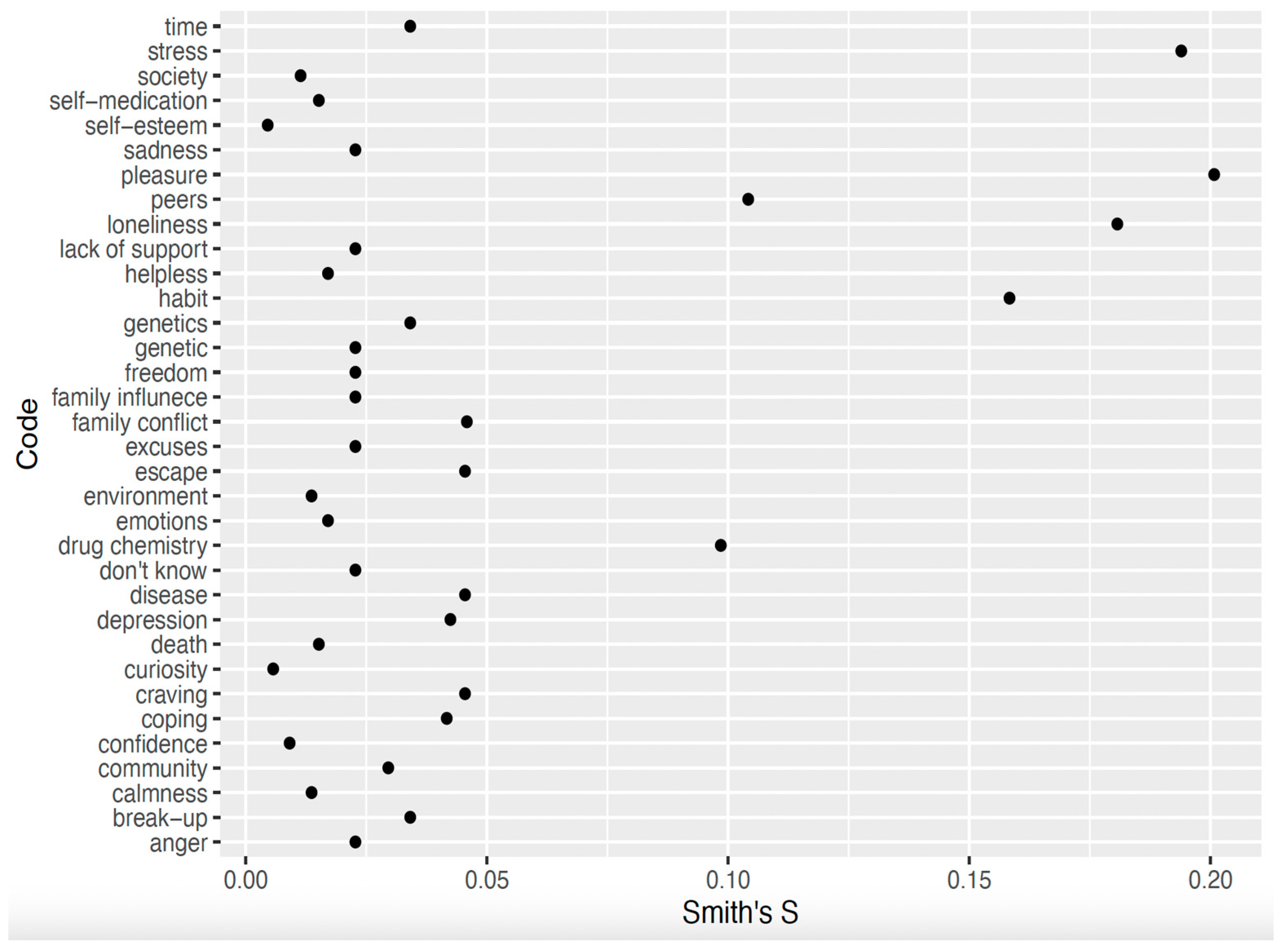

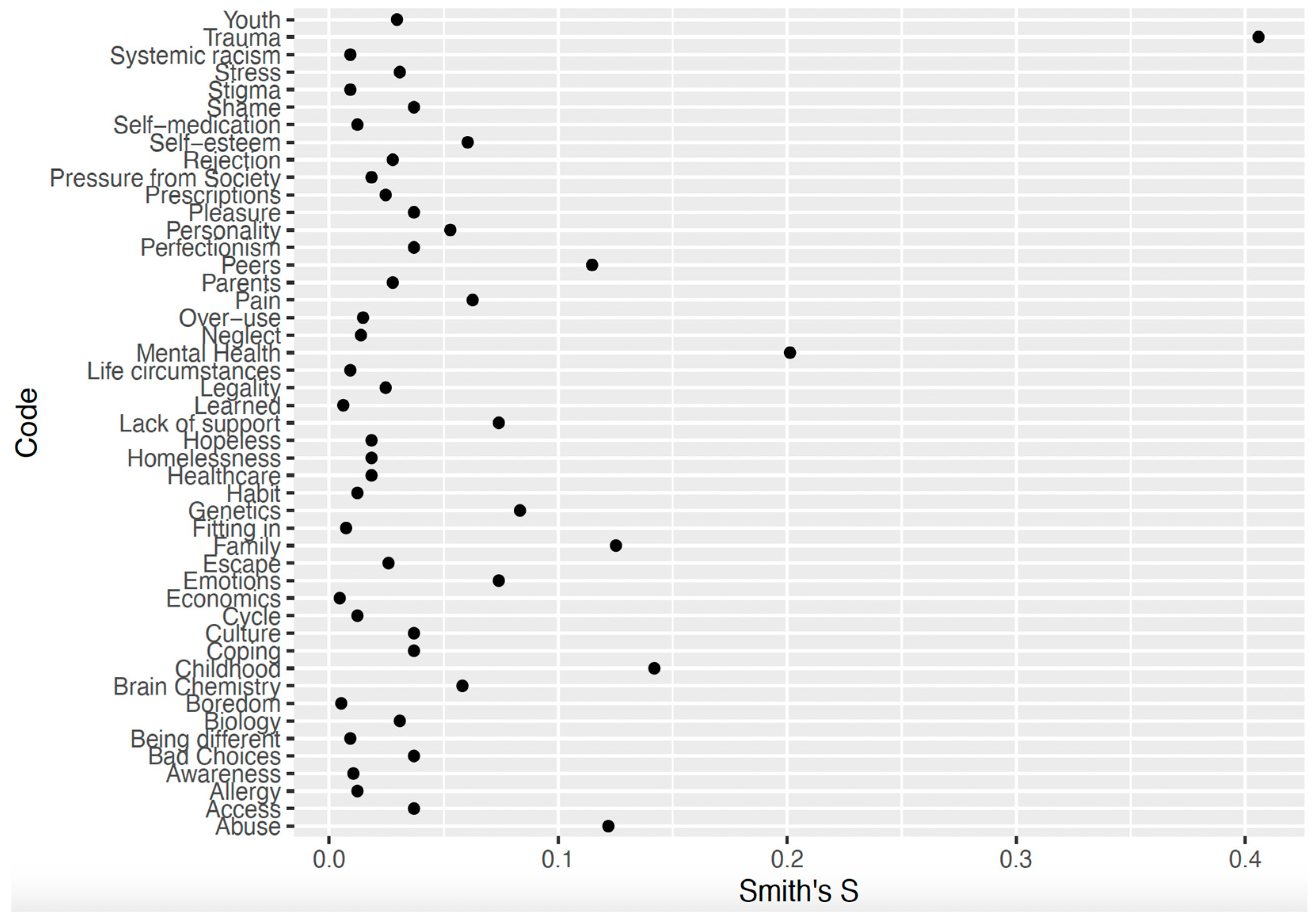

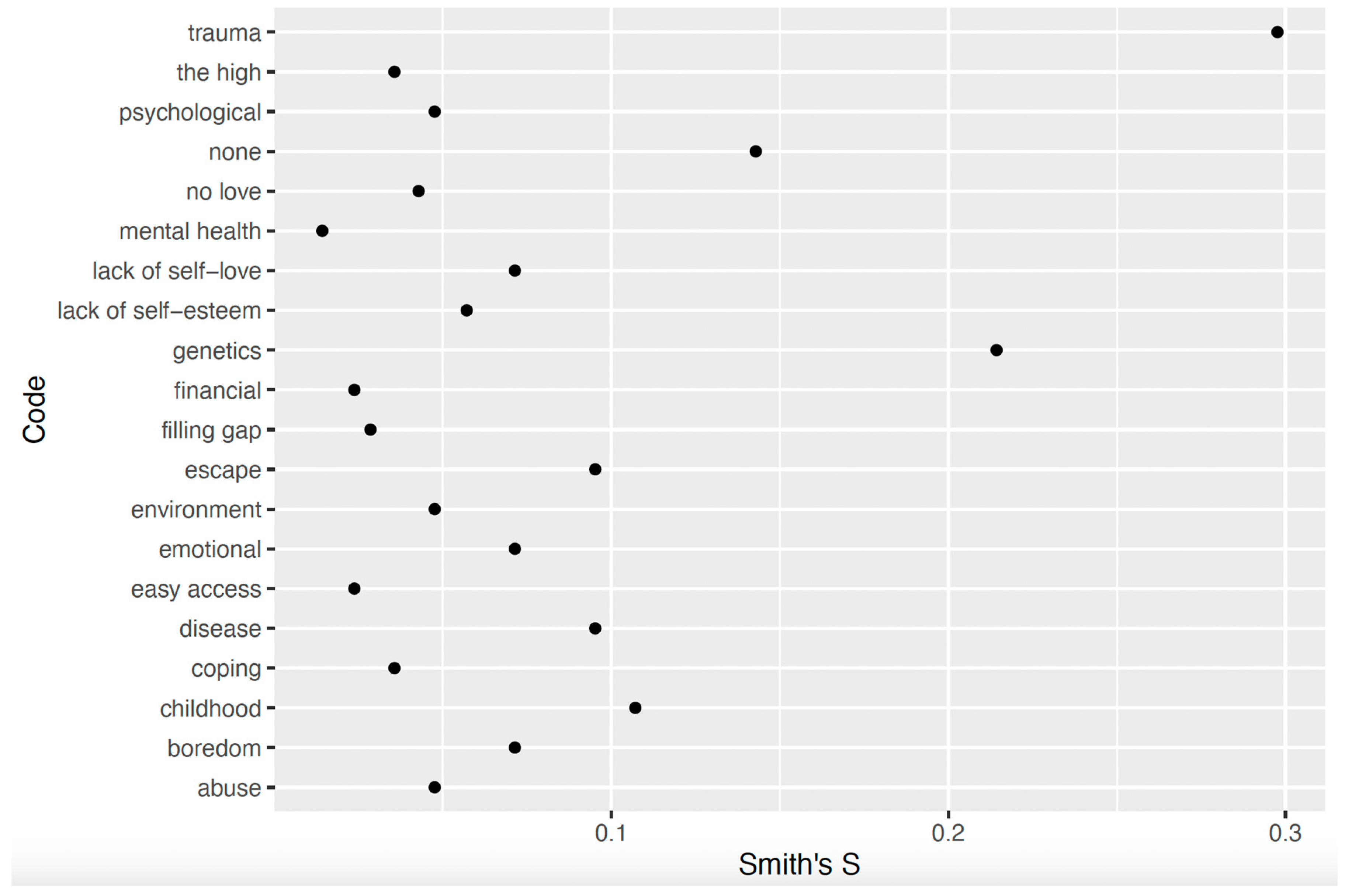

- What causes addiction?

- Delhi

- Toronto

“So, I think it's just the unreal expectations that society has toward women, especially mothers, and like to be the perfect mother to look perfect to have a job plus, do all the things for your children, like extracurricular activities, to juggle that perfect life. And then, you know, when you have mental health issues like that, that are also, you know, it also I just, I think mental health, causes you to have like, especially like postpartum depression or something like that.”

“Oh, that's a real open-ended question. It could be anything from childhood trauma, abuse, mental illness. It could be physical pain from accidents. It could be homelessness or home insecurity. It could be just neglect in general. All of those. There may be even more. It could be systematic racial problems that they've faced or economic problems. A lot of it is all integrated. I don't think there's one or the-- I don't find one is without another. I think that they're all somehow intertwined.”

“Oh, what do we think causes it? You know, I'm not really of the opinion that you have to have some sort of like, trauma, to end up a drug user. You know, I think even just something so simple as bad choices can put you in a situation where you're doing a drug that you have to do every day, even though that's not something that you ever thought you would end up doing, you know, what I think causes it, you know, being a kid being dumb, you know, going out, being with different people, you know, everything could put you in a situation where you're, you know, maybe going to do drugs where you normally wouldn't? What makes you end up a habitual drug user? I think choosing the wrong drug too many times.

“Well, yes, I mean, it starts as you know, like, you just don't even think that because you grow up having it around, or people do or for me, personally, but it's always around, and you don't realize that you use it when you're, you know, I'm also a smoker. So I was reading, you know, a cigarette, you can use when you're happy when you're sad when you're mad like it. It's the cure for everything.”

- London

“In my opinion, trauma, behaviors copied, learned from what you witness as a child, especially around the age of seven to eight when you're more likely to remember your life. I know for me it is the type of counseling I did and rehabilitation that I was in and what I've learned about myself, I was able to change some behaviors and recognize that and change those.”

“That's a really tricky question. For me personally, I think it was hereditary. My father and my brother are both alcoholics, so I think I have the addictive gene. Personally, I didn't believe that I could be an alcoholic because I was female, and I didn't think that women could be alcoholics. I think it can also come down to circumstance as well in terms of overuse can just cause you to become addicted to that.”

“I think past life, like childhood or really what's happened to you in your life. You want to forget. Do you understand? Forget things or to cope with stuff that's going to happen.”

Discussion

Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Note

References

- Antweiler, C. (2015). Ethnicity from an anthropological perspective. In Ethnicity as a Political Resource. University of Cologne Forum.

- Avasthi, A. , & Ghosh, A. (2019). Drug misuse in India: Where do we stand & where to go from here? Indian Journal of Medical Research. [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S. P. (1998). Elicitation Techniques for Cultural Domain Analysis. In The Ethnographers Toolkit (Vol. 3). Alitmira Press.

- Boyd, R. , & Richerson, P. J. (1988). Culture and the Evolutionary Process.

- Brady, K. , Grice, D., Dustan, L., & Randall, C. (1993). Gender difference in substance use disorders. ( 150, 1707–1711. [CrossRef]

- De Kock, C. (2020). Cultural competence and derivatives in substance use treatment for migrants and ethnic minorities: What’s the problem represented to be? Social Theory & Health. [CrossRef]

- Degenhardt, L. , Charlson, F., Mathers, B., Hall, W. D., Flaxman, A. D., Johns, N., & Vos, T. (2014). The global epidemiology and burden of opioid dependence: Results from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Addiction, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, A. , Ackermann, R. R., Athreya, S., Bolnick, D., Lasisi, T., Lee, S., McLean, S., & Nelson, R. (2019). AAPA Statement on Race and Racism. ( 169(3), 400–402. [CrossRef]

- Gatewood, J. B. (1984). Familiarity, vocabulary size, and recognition ability in four semantic domains. American Ethnologist. [CrossRef]

- Groshkova, T. , Best, D., & White, W. (2013). The Assessment of Recovery Capital: Properties and psychometrics of a measure of addiction recovery strengths. Drug and Alcohol Review. [CrossRef]

- Hewlett, B. S. (2004). Fathers in Forager, Farmer, and Pastoral Cultures. In The Role of the Father in Child Development, ed. Michael Lamb (pp. 182–195). Wiley.

- Hollen, C. C. V. (2022). Cancer and the Kali Yuga: Gender, Inequality, and Health in South India.

- Kleinman, A. , & Benson, P. (2006). Anthropology in the Clinic: The Problem of Cultural Competency and How to Fix It. PLOS Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Nasser, R. (2005). A Method for Social Scientists to Adapt Instruments From One Culture to Another: The Case of the Job Descriptive Index. Journal of Social Sciences.

- Pierce, M. , van Amsterdam, J., Kalkman, G. A., Schellekens, A., & van den Brink, W. (2021). Is Europe facing an opioid crisis like the United States? An analysis of opioid use and related adverse effects in 19 European countries between 2010 and 2018. European Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Placek, C. (2024). Drug Use, Recovery, and Maternal Instinct Bias: A Biocultural and Social-Ecological Approach.

- Placek, C. , Budzielek, E., White, L., & Williams, D. (2023). Anthropology in Evaluation: Free-listing to Generate Cultural Models. American Journal of Evaluation.

- Placek, C. D. , Place, J. M., & Wies, J. (2021). Reflections and Challenges of Pregnant and Postpartum Participant Recruitment in the Context of the Opioid Epidemic. ( 25(7), 1031–1035. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Placek, C. , & Wies, J. (n.d.). Cultural Competence for Drug Addiction and Recovery: Considerations for Research and Evaluation. Social Theory & Health.

- Purzycki, B. G. , Pisor, A. C., Apicella, C., Atkinson, Q., Cohen, E., Henrich, J., McElreath, R., McNamara, R. A., Norenzayan, A., Willard, A. K., & Xygalatas, D. (2018). The cognitive and cultural foundations of moral behavior. ( 39(5), 490–501. [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, M. (2005). Considerations for Collecting Freelists in the Field: Examples from Ethobotany. Field Methods. [CrossRef]

- Romney, A. K. , & D’andrade, R. G. (1964). Cognitive Aspects of English Kin Terms. G. ( 66(3), 146–170. [CrossRef]

- Shaghaghi, A. , Bhopal, R. S., & Sheikh, A. (2011). Approaches to Recruiting ‘Hard-To-Reach’ Populations into Re search: A Review of the Literature. Health Promotion Perspectives. [CrossRef]

- Sharif, M. Z. , García, J. J., Mitchell, U., Dellor, E. D., Bradford, N. J., & Truong, M. (2022). Racism and Structural Violence: Interconnected Threats to Health Equity. Frontiers in Public Health. [CrossRef]

- Slabbert, I. , Greene, M. C., Womersley, J. S., Olateju, O. I., Soboka, M., & Lemieux, A. M. (2020). Women and substance use disorders in low- and middle-income countries: A call for advancing research equity in prevention and treatment. Substance Abuse. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. J. , & Borgatti, S. P. (1997). Salience CountsAnd So Does Accuracy: Correcting and Updating a Measure for Free-List-Item Salience. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. [CrossRef]

- Tuchman, E. (2010). Women and Addiction: The Importance of Gender Issues in Substance Abuse Research. Journal of Addictive Diseases. [CrossRef]

- White, L. A. (1959). The Concept of Culture. American Anthropologist, /: 227–251. https, 6650. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).