1. Introduction

Soil improvements are fundamental to civil engineering, enabling construction on soils that would otherwise lack the necessary strength and stability [

1]. As urbanization increases, particularly in metropolitan areas where space is limited, the need for effective soil improvement solutions has grown [

2]. In urban areas, soils often consist of soft or loose deposits that cannot adequately support structural loads, requiring reinforcement through soil improvements to ensure the safety and durability of infrastructure [

3]. In addition, the confined nature of these urban spaces and the variety of soil profiles encountered, ranging from soft clay and organic soils to sandy and humus-rich deposits, present unique challenges to conventional soil improvement technologies [

4].

Conventional columnar soil improvement technologies, which typically use in-situ mixing of solidifying agents such as cement, are widely used to enhance columnar soil structures that improve soil stability and increase bearing capacity [

1,

5,

6]. These technologies involve complex processes that require large, specialized machinery such as mixing plants and heavy-duty equipment capable of deep soil agitation and mixing [

1,

5,

6]. While effective in constructing columnar soil improvements, these conventional technologies have significant limitations, especially when applied in challenging urban environments [

7]. The strength of the improved soil column is highly dependent on the setting potential of the cement-based material, which can be compromised by soil variability, including high moisture content or organic matter [

8]. In addition, the machinery required for conventional technologies is often bulky, requiring large footprints and significant mobilization efforts, which limits their applicability in densely developed areas and results in significant construction costs [

9,

10]. These heavy equipment requirements also introduce logistical complexities, including the need for storage space, energy sources, and extensive setup time, further complicating their use in compact urban environments where space and accessibility are limited [

11,

12].

In response to these limitations, the Soil Squeezing Technology (SST), an innovative soil improvement technology based on the principles of displacement, compaction, and solidification, has been developed [

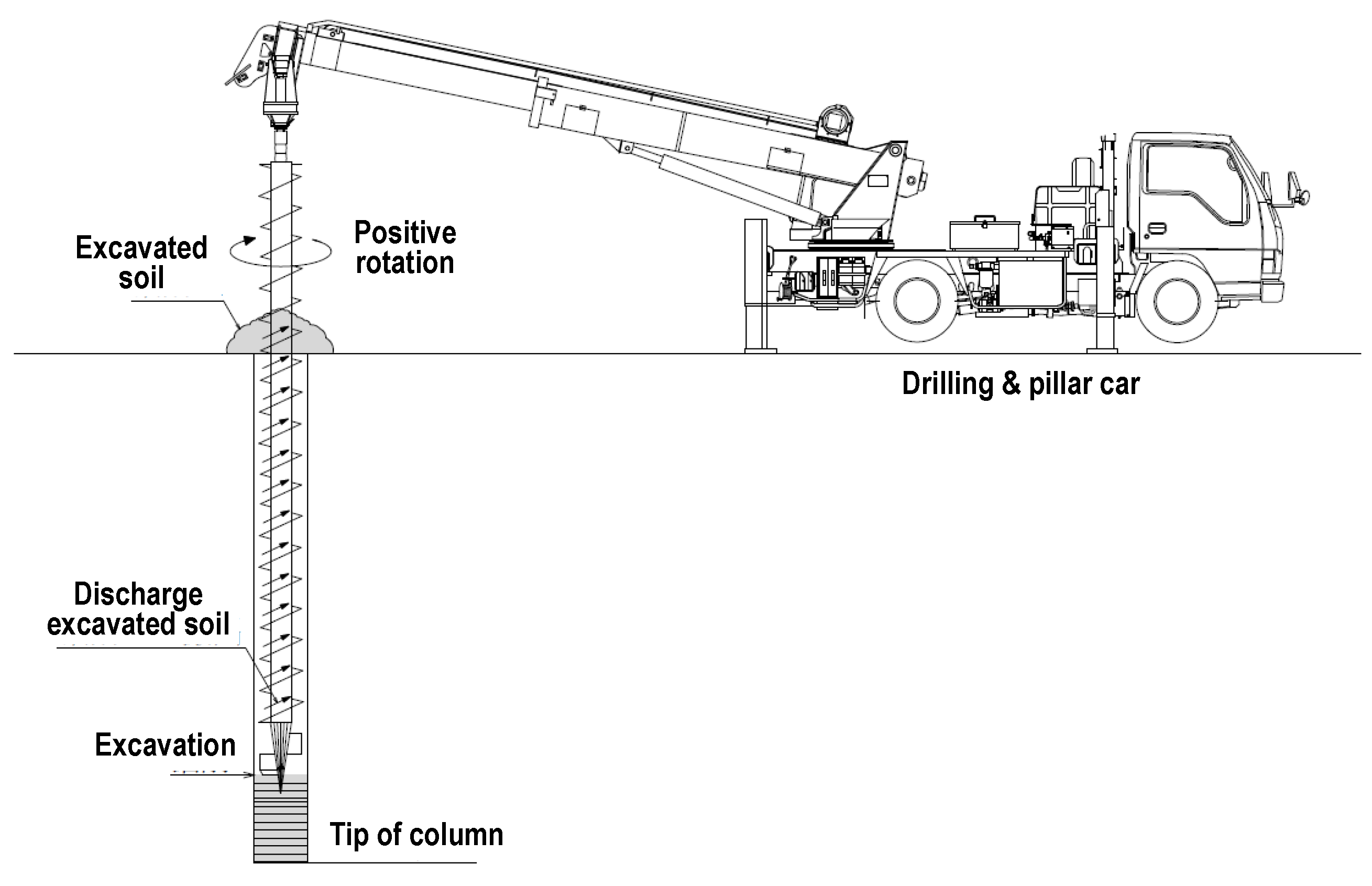

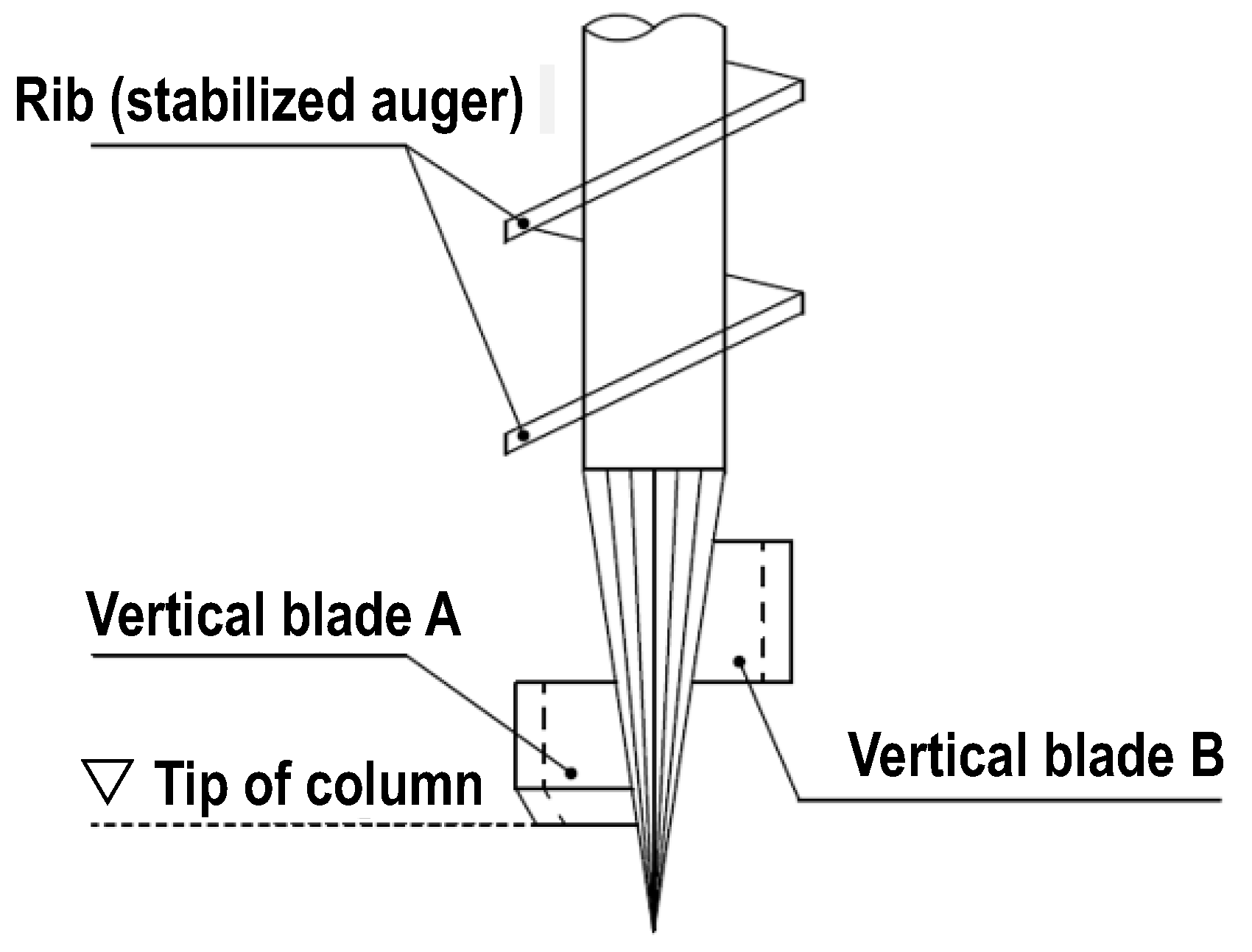

13]. The overall appearance of the SST is shown in

Figure 1. Unlike conventional approaches, the SST is designed to avoid extensive in-situ mixing and instead focuses on compaction of soil particles to eliminate voids, a fundamental principle of soil mechanics [

14]. According to soil mechanics, soil strength is maximized when voids between particles are minimized [

14,

15], and this concept forms the basis of the SST approach. The SST consolidates soil particles of various sizes and introduces a cement-based solidifier that increases particle cohesion, allowing for the construction of dense, robust improved soil columns [

13]. This approach allows the SST to construct highly durable improved soil columns that are suitable for a wide range of soil types, including problematic soils such as humus and high organic content soils that are conventionally difficult to stabilize [

16]. By minimizing the dependence on specific soil properties, the SST process offers consistent quality and reliability, making it applicable to a wide range of soil conditions [

13].

One of the key advantages of the SST is its adaptability to urban environments, where construction is often constrained by space [

17]. In modern cities, as available land for development becomes scarcer, the need to build in confined or irregularly shaped spaces is increasing [

18]. The large equipment required by conventional technologies may not fit into tight construction sites or could disrupt surrounding infrastructure, making conventional approaches impractical [

19]. In contrast, the SST uses compact, mobile equipment that can operate efficiently in confined spaces [

13]. This reduction in equipment size and complexity not only improves accessibility, but also increases work efficiency and reduces costs because the smaller machines require less setup time and fewer on-site resources [

20]. In addition, the SST process does not require an on-site mixing facility for the solidifying materials, further minimizing logistical challenges. This feature is particularly advantageous in urban environments where minimal disruption to surrounding buildings and infrastructure is essential [

21]. By simplifying operational requirements, SST provides an effective soil improvement solution that is ideally suited to the constraints of urban construction projects, promoting smoother and less disruptive construction processes.

This study provides a comprehensive overview of the SST, detailing its unique compaction-based mechanism and field application process. The SST auger, designed specifically for this technology, compacts the soil and introduces solidifying materials in a controlled manner, facilitating the formation of homogeneous, high-strength improved soil columns [

13]. Through detailed field application examples, this paper demonstrates how the SST consistently achieves superior strength and uniformity in a variety of soil types, even in environments that present significant geotechnical challenges [

22,

23]. These case studies highlight the adaptability and practicality of the SST, demonstrating its ability to meet the demands of urban construction without compromising quality or safety [

24,

25]. The results of this research suggest that the SST not only overcomes the limitations associated with conventional soil improvement technologies, but also provides a scalable, cost-effective alternative that is well suited to urban geotechnical applications [

26,

27]. As a result, the SST contributes to the development of safer, more resilient infrastructure within the complex landscape of modern cities, meeting both the technical and practical requirements of contemporary urban construction [

28].

2. Overview, Mechanism and Key Features for the SST

The SST represents an innovative approach to soil improvement by focusing on displacement, compaction, and controlled solidification rather than the conventional reliance on in-situ mixing of solidifying agents. This technology directly addresses the constraints and limitations of conventional columnar soil improvement technologies, which are often challenged in densely populated urban areas where spatial limitations and soil variability pose significant obstacles. Using basic soil mechanics principles, the SST reduces voids and increases soil density, improving cohesion and bearing capacity. This capability enables the SST to construct high-quality, durable improved soil columns in a variety of soil types, extending its applicability to complex urban geotechnical conditions.

2.1. Scope, Design Specifications, and Materials

The SST was developed specifically to address the challenges of urban geotechnical applications [

22,

23]. Its scope extends to a wide range of soil types, including cohesive soils, granular soils, humic layers, and organic-rich deposits, all of which often present significant difficulties for conventional improvement technologies. The SST introduces a cement-based hardening agent in carefully controlled quantities to improve soil cohesion while minimizing dependence on the soil's inherent chemical properties. This adaptability ensures that the SST delivers consistent quality and performance under variable geotechnical conditions.

The design specifications of the SST emphasize compact and mobile equipment that can operate in the confined environments characteristic of many urban construction sites. Unlike conventional technologies [

5,

29] that require extensive site preparation and large, specialized machinery, the SST system can be deployed with minimal logistical effort. This feature is particularly advantageous in densely developed areas where space and resources are limited, making the SST not only more accessible, but also more cost-effective for a wide range of project sizes and complexities. The SST and equipment specifications detailed in

Table 1 reflect these design priorities, ensuring a balance between performance and operational efficiency.

2.2. Construction Method

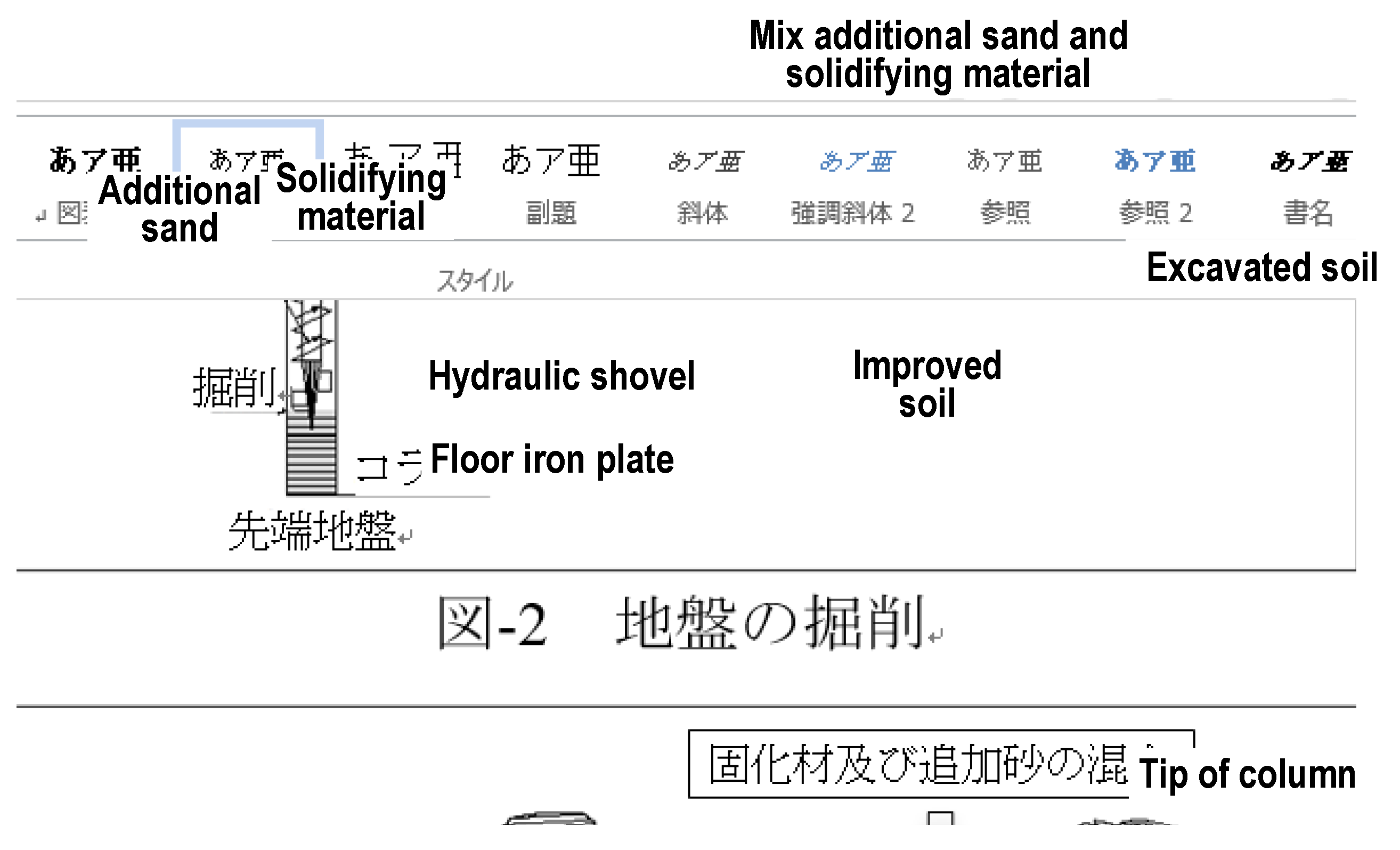

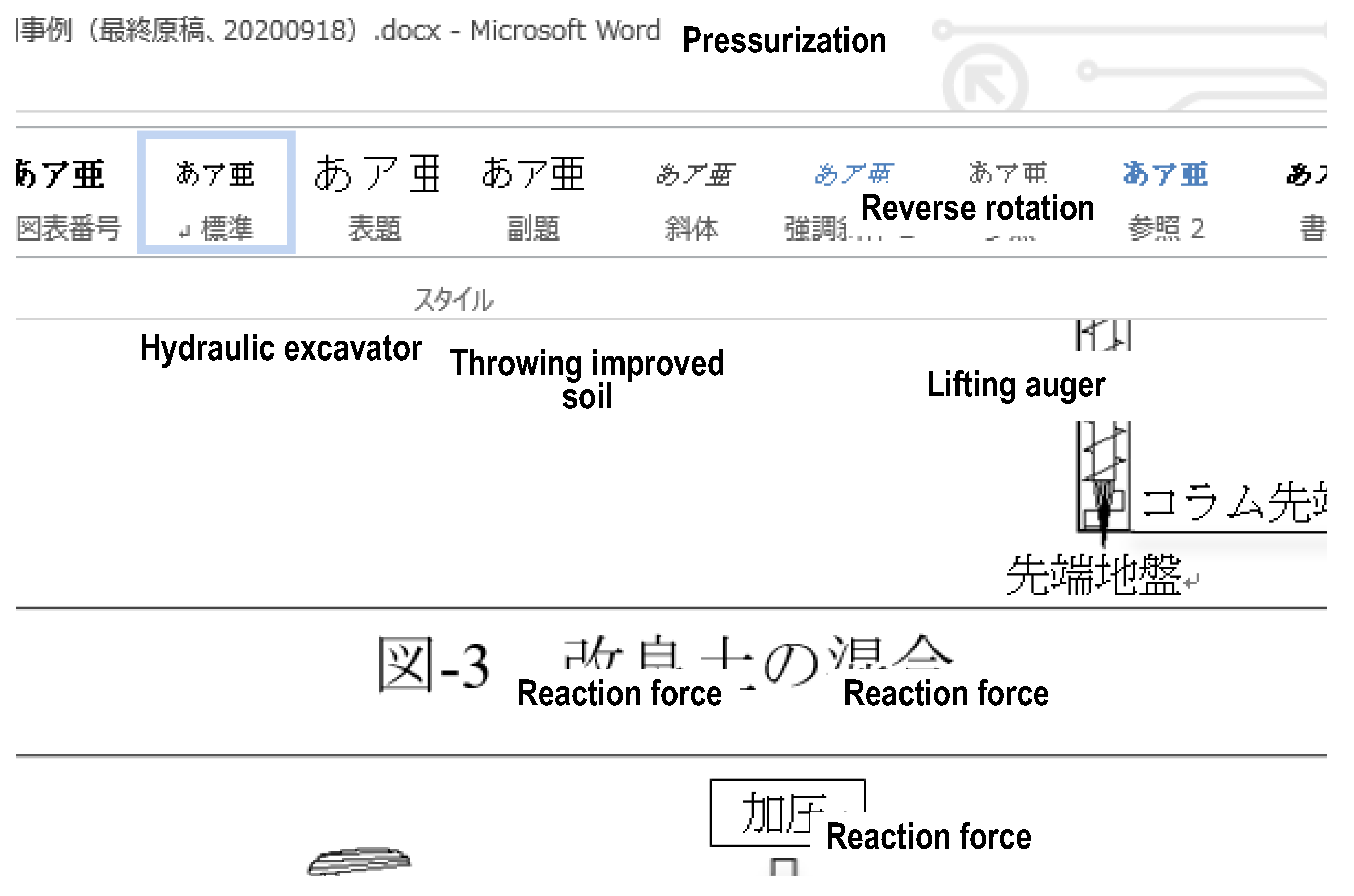

The SST process is a methodical sequence that maximizes soil density and cohesion while minimizing site disturbance, which is critical in urban areas where construction sites are often bounded by existing infrastructure. As shown in

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, the construction process begins with the forward rotation of the SST auger to excavate the soil to the target depth. Following the excavation phase, the displaced soil is removed and additional materials-such as sand and a stabilizing agent-are added in proportion to the excavated soil type. The hydraulic excavator mixes these materials in place to ensure a uniform composition before the auger reverses to compact the mixture into a high-density improved soil column. This reverse rotation gradually lifts the auger, constructing a re-action force that further consolidates the soil, increasing the structural strength of the improved soil column.

This construction method is particularly suited to urban projects due to its efficient, space-saving design. By eliminating the need for large mixing plants and complex lo-gistics, SST simplifies site operations and reduces construction time. The compact equipment, including a self-propelled boring vehicle and hydraulic excavator, allows for easy mobilization in confined spaces, making it possible to deliver high-quality soil improvement on tight urban sites. In addition, the method's reliance on dry materials eliminates the need for on-site water or electricity, significantly reducing both envi-ronmental impact and operating costs.

By focusing on displacement, compaction and controlled solidification, the SST process achieves a level of structural reinforcement and soil stability that exceeds conventional technologies [

5,

29], especially in urban environments where conventional soil improvement technologies are limited by space and logistical complexity. The SST process, with its simple application and compact equipment, is a transformative approach to urban soil improvement, providing robust structural support for modern infrastructure projects in densely developed areas.

2.3. Compaction Mechanism

At the heart of the SST process is its advanced compaction mechanism, made possible by the unique design of the SST auger. The auger is equipped with counter-rotating blades that simultaneously excavate and compact the soil into a dense, columnar soil structure (see

Figure 5). This dual compaction process applies force both vertically and horizontally, consolidating soil particles into a high-density matrix that minimizes voids and increases bearing capacity. Unlike conventional soil improvement technologies [

5,

29] that rely heavily on mixing to achieve structural integrity, the rotating system of the SST auger constructs a dense, cohesive structure with uniform strength and stability, even in soils with high moisture content or organic material.

The SST auger's counter-rotating blades are specifically designed to maximize compaction force, forming a strong improved soil column while reducing disturbance to the surrounding soil. This mechanism not only improves the uniformity and reliability of the improved soil column, but also minimizes soil deformation and displacement, making the SST particularly suitable for urban areas where soil stability is essential.

Figure 6 illustrates the detailed compaction process, showing how the SST auger effectively con-solidates soil particles to achieve superior improved soil column strength and durability in challenging soil conditions.

2.4. Homogeneity and Quality Control

Achieving homogeneity in the improved soil column is a key advantage of the SST, largely due to the highly controlled compaction process. Conventional technologies [

5,

29] often result in uneven density within improved soil columns due to inconsistencies in soil mixing, leading to potential structural weaknesses. The SST mitigates these problems by incorporating a pre-mixing step that is performed at the surface before the compacted material is introduced into the borehole. This pre-mixing step, performed using a hydraulic excavator, reduces the variability often caused by differences in soil properties such as moisture content and organic composition [

30]. The result is a uniform composition throughout the improved soil column, essential for structural reliability (see

Figure 7 for improved soil column uniformity).

Quality control is further improved by real-time inspection of the excavated soil, allowing operators to assess soil conditions directly [

31,

32,

33]. This on-site inspection capability allows for immediate adjustments, such as changing material composition to address unexpected soil inconsistencies, ensuring that the final improved soil column meets required structural standards. By minimizing reliance on post-construction testing and rework, the SST streamlines the construction process while maintaining rigorous quality standards, making it ideal for time-sensitive urban projects.

2.5. Structural Strength and Urban Applicability

The SST process is capable of producing high-strength improved soil columns that meet the stringent load-bearing requirements of modern urban infrastructure, with design strength standards up to 2400 kN/m

2. The compaction process benefits from the addition of sand particles that optimize the grain size distribution within the improved soil column, resulting in greater compaction and increased bearing capacity. This structural strength exceeds that achieved by conventional soil improvement technologies [

5,

29], making the SST process highly suitable for urban environments where structural integrity is critical to support dense construction and high traffic loads.

In addition to its strength advantages, the compact footprint of the SST process, which uses equipment such as self-propelled drills and hydraulic excavators, allows for efficient use in confined urban spaces that are otherwise inaccessible to larger equipment. This characteristic is particularly advantageous for geotechnical projects in congested city centers, where space and logistical challenges limit the use of conventional soil improvement technologies [

34]. The SST process is also environmentally sustainable, reducing resource consumption by limiting the need for on-site water and energy-intensive mixing. This sustainable design further enhances the viability of the SST process for urban applications where reducing environmental impact is an increasing priority.

2.6. Visibility, Operability and Environmental Impact

The SST prioritizes operational visibility, workability, and sustainability, all of which are critical factors for effective implementation in urban construction projects [

35]. By extracting and exposing the excavated soil to the surface, the SST provides real-time visual inspection of soil characteristics, including texture, stratification, and groundwater levels, enhancing both quality control and safety. This visibility allows operators to make real-time adjustments to materials and procedures based on observed soil conditions, ensuring the consistency and reliability of the improvement process (see

Figure 7 for a visual of improved soil columns). This capability is particularly valuable in urban areas, where soil variability can present unpredictable challenges and require immediate responses.

Workability is another key advantage of the SST, as reduced equipment requirements simplify site operations. By using compact, mobile equipment instead of large mixing plants and heavy machinery, the SST reduces logistical complexity, construction costs, and project schedules.

Table 1 outlines the reduced equipment and resource requirements of the SST process, highlighting its efficiency. In addition, the SST's reduced reliance on water and electricity for the compaction process directly reduces its environmental impact, addressing the growing need for sustainable construction practices in densely populated urban areas.

The SST provides an adaptable, sustainable and efficient solution for modern urban geotechnical applications [

36]. Its innovative approach to displacement, compaction and controlled solidification enables high quality soil improvement even in the most spatially and logistically constrained environments. This makes the SST a comprehensive solution that meets both the technical requirements of urban construction and the practical needs for reduced environmental impact, operational efficiency, and cost effectiveness.

3. Examples of On-Site Application of the SST

3.1. Case Study of Field Application on Humus Soil

3.1.1. Construction Overview

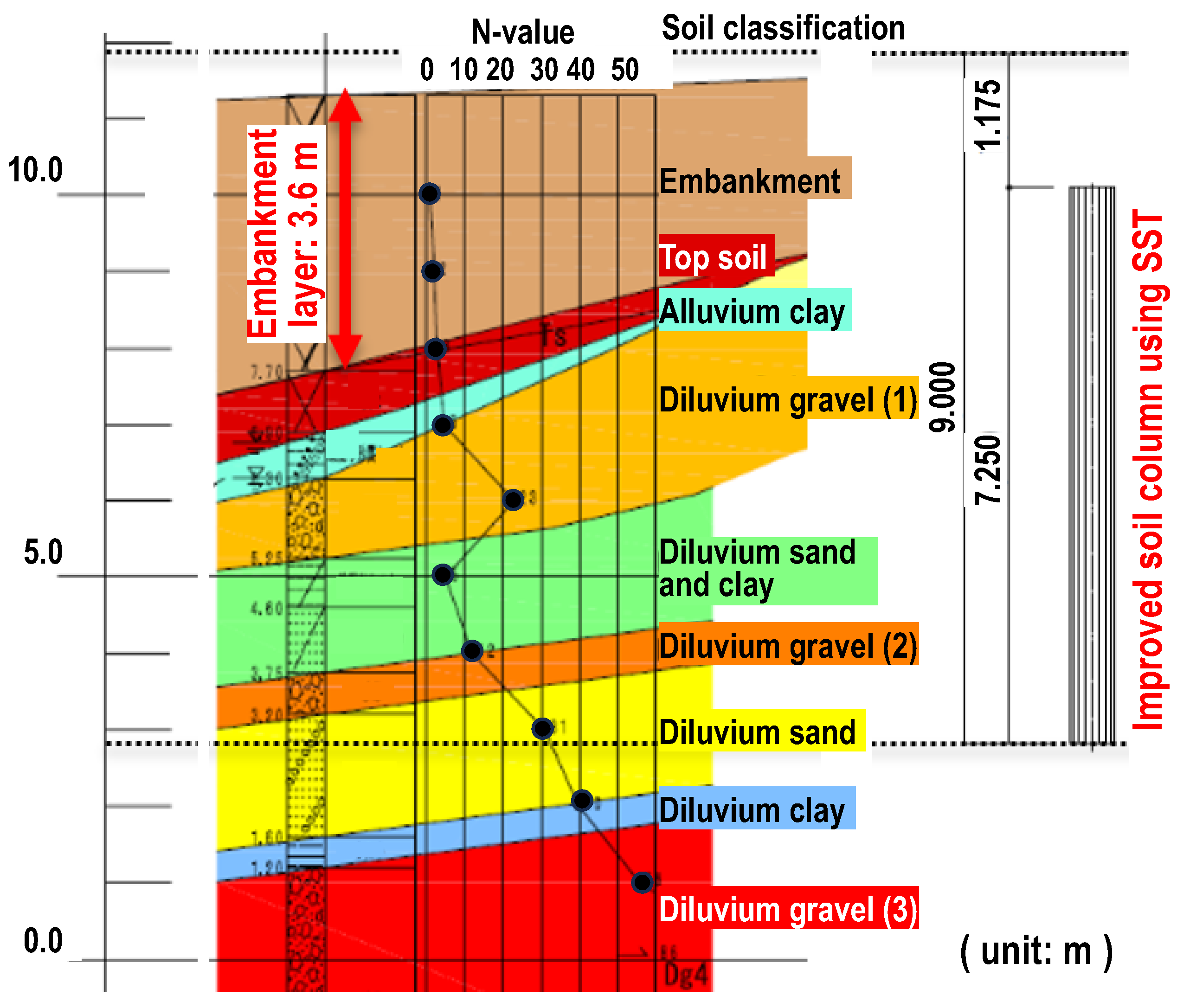

In the construction project for the two-story reinforced concrete building in Togane, Chiba Prefecture, the site conditions posed unique challenges due to the underground stratigraphy. Located on an alluvial plain, the project required a soil improvement solution to ensure the stability and safety of the foundation with a bearing capacity of 65 kN/m

2 over a foundation area of 829.54 m

2. The site profile as shown in

Figure 8 indicated a sequential layering from the surface including topsoil, an alluvial clay layer, an alluvial sandy soil layer and a diluvial clay layer. In particular, the humus layer at a depth of approximately 2.4 m presented a significant challenge due to its high organic content, which conventionally complicates stabilization efforts.

The humus layer, characterized by organic material with low density and cohesion, increases the difficulty of achieving adequate structural stability [

37]. Its high moisture content contributes to a reduced ability to form a cohesive structure when conventional soil improvement technologies are used. The SST has therefore been adopted as it allows effective improvement by displacement and compaction, particularly suitable for weak and moisture retaining soils. By using the SST, the project aimed to achieve uniform strength throughout the columnar soil structure while minimizing disturbance to adjacent soil layers. This innovative SST also reduced the need for extensive mixing and allowed for targeted application within the humus layer, providing the foundation stability required for the design load requirements of the proposed building.

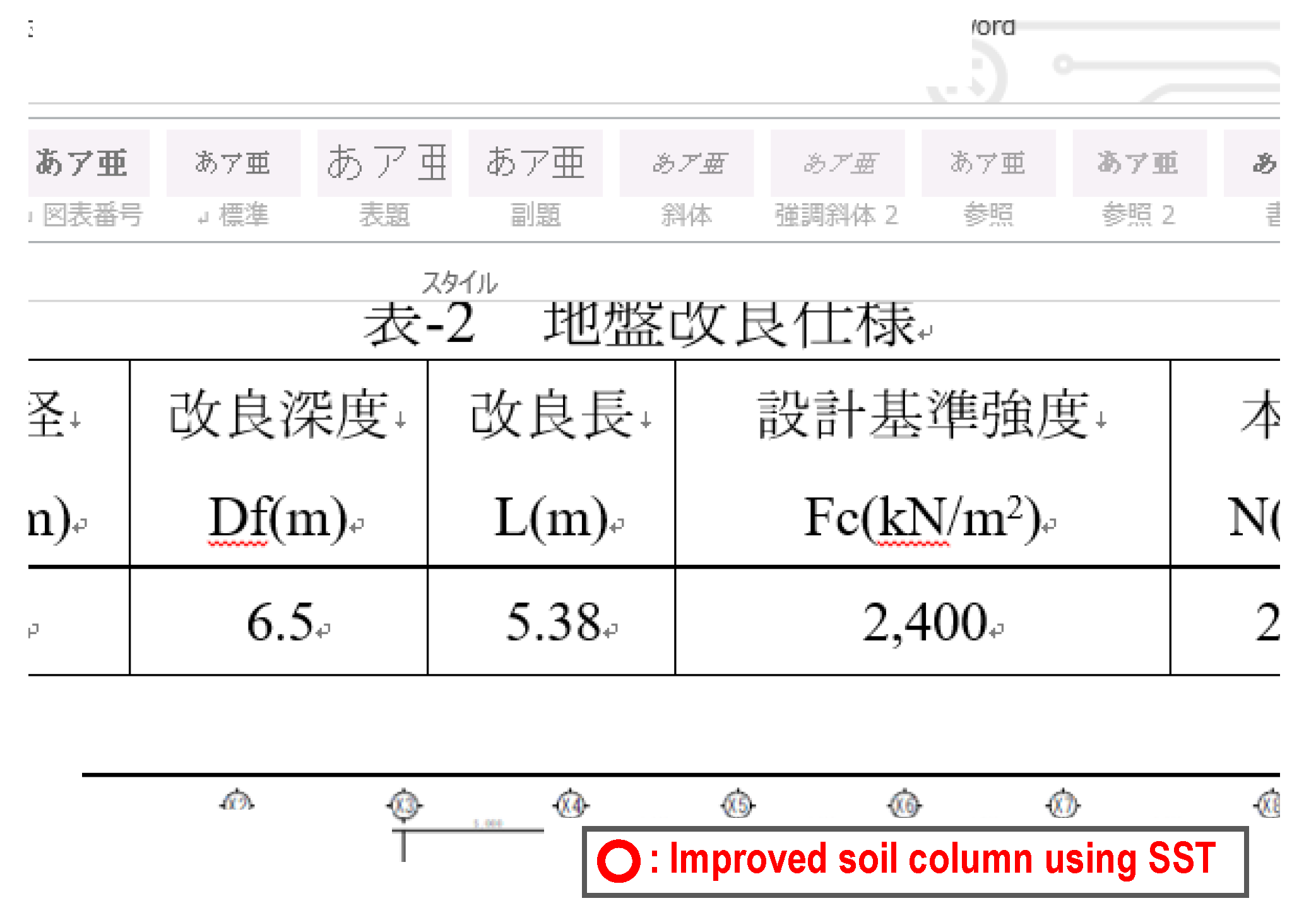

3.1.2. Soil improvement specifications

Given the unique characteristics of the humus soil, specific improvement parameters were carefully designed to achieve the necessary strength and durability for the columnar soil structure. The natural water content of the humus soil was found to be significantly high (wn = 481.9%), which combined with its organic composition made it difficult to achieve sufficient unconfined compressive strength by conventional means. To address this, the improvement mix was specified to include a 1:1 ratio of additional sand to help improve the grain structure of the soil, and a cement based stabilizer content of 200 kg/m

3, as summarized in

Table 2.

Figure 9 illustrates the layout of the improvement plan, which outlines the spatial distribution and depth profile of the improved soil columns.

The addition of sand is intended to increase the frictional resistance within the soil matrix, thereby improving compaction effectiveness and cohesion. This addition not only addresses the issue of moisture retention, but also assists in the uniform distribution of the cement-based stabilizer throughout the humus layer. The selection of a cement-based solidifier was based on its proven ability to bind to organic-rich soils, thereby improving structural integrity and resistance to settlement under load. This composition ensures that the columnar soil structure maintains a consistent quality and strength throughout the depth of the improvement, mitigating potential variations in strength typically observed in organic soils [

38].

3.1.3. Quality of improved soil column

Quality control in this project was rigorously implemented to ensure that the SST constructed a consistently strong and durable improved soil column. Unlike conventional technologies that rely heavily on post-construction testing, the SST incorporates real-time quality assessments using molded test specimens immediately after improved soil column formation. For this project, quality control focused on the unconfined compressive strength of these molded specimens, which serve as reliable indicators of the structural integrity of the soil improvement. A coefficient of variation was set at 30% to maintain consistency with data from previous SST implementations, which provided a benchmark for quality [

39].

Sampling was conducted at five points along the improved soil column structure, including the top and bottom, with three samples collected from each point. This approach provided a comprehensive strength profile of the improved soil column (see

Table 3 for quality control results). By testing samples from both the top and bottom, it was possible to identify and correct for any potential discrepancies in density or cohesion that could result from the inherent variability of the humus layer. The quality control results showed that the average unconfined compressive strength (28 days after construction) met the project's acceptance value (X

L), confirming that the SST effectively improved the soil properties in the humus layers. In addition, the compaction process under dry condition helped reduce moisture-related weakening, allowing the improved soil columns to achieve stable and uniform bearing capacity that met or exceeded design standards.

3.2. Case Study of Field Application in Loam and Black Soils

3.2.1. Construction overview

The SST was selected as the soil improvement for a construction project of a four-story waterproof reinforced concrete building in Shinjuku, Tokyo. The project involved a mat foundation with a bearing capacity requirement of 120 kN/m

2 over a foundation area of 180.0 m

2. Located on an alluvial plateau, the site had a complex subsurface stratigraphy consisting of alternating layers of fill, topsoil, alluvial clay, sand, gravel, and other de-posits, as shown in

Figure 10. The primary layer targeted for improvement was a 3.6 m thick heterogeneous fill layer containing clay, black soil, and various subsurface obstructions including brick and concrete fragments. This variability in soil composition posed significant challenges, particularly with regard to the risk of strength inconsistencies along the depth of the improved soil column.

With conventional technologies, the presence of such diverse materials often results in uneven strength distribution, especially in the depth direction. However, the SST's con-trolled replacement and compaction approach provided a unique solution that allowed for high-strength column structures even in challenging environments. In addition, the SST allowed work to proceed primarily above soil, reducing the need for deep mixing or in-situ chemical stabilization that would be complicated by the existing obstructions. This aspect was particularly beneficial given the limited space and urban environment, where minimizing disruption to surrounding infrastructure was critical.

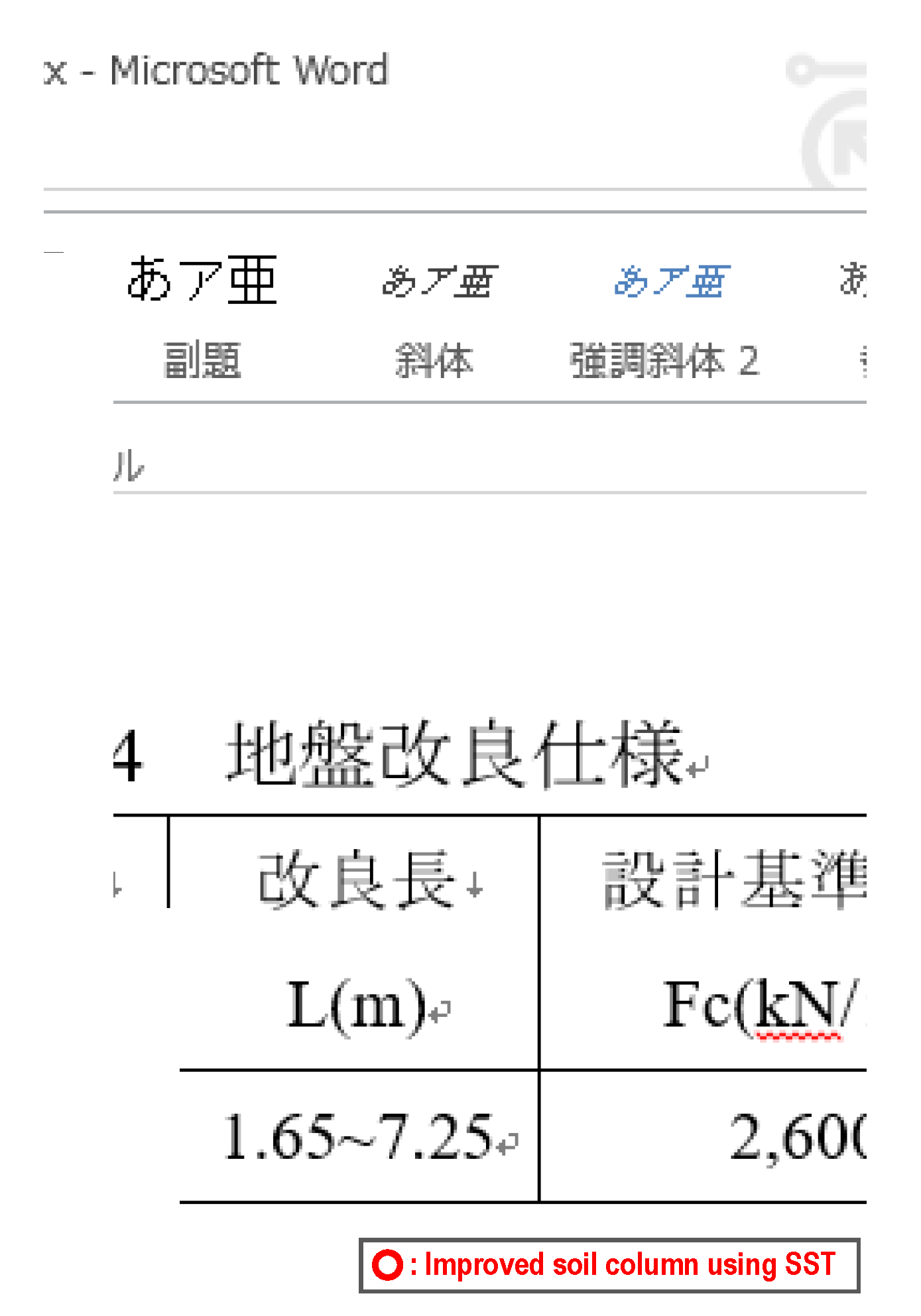

3.2.2. Soil improvement specifications

The soil improvement specifications in this case were carefully tailored to meet the specific requirements of the loam and black soils, both known for their low strength development [

39]. As shown in

Table 4, the improvement mix employed a 1:1 ratio of additional sand to improve the soil matrix and included a cement-based solidifier at a concentration of 200 kg/m

3.

Figure 11 shows the detailed layout of the soil improvement plan.

The added sand served several purposes: to improve the grain size distribution of the soil for better compaction, to increase cohesion, and to distribute the solidifier more uniformly throughout the improvement zone. This composition was considered optimal to address the inherent weaknesses of the clay and black soils. In addition, since black soil was found to be unsuitable for stabilization and often interfered with the consistency of the improved soil column, it was systematically removed along with other obstructions. This removal was critical to ensure that the SST could achieve the desired structural homo-geneity and load bearing capacity, as the high organic content of the black soil would otherwise have compromised the long-term stability of the improved soil columns.

3.2.3. Quality of the improved soil columns

The quality control strategy for this project focused on achieving uniform compressive strength throughout the improved soil columns. As described above, unconfined com-pressive strength testing of shaped specimens was used as the primary control metric. Due to the expected variability within the backfill layer and the challenging depth of improvement, quality control utilized the “B” inspection method, which is applicable when strength variation is unpredictable [

39]. This approach required increased sampling of more than 25 cores, resulting in a total of 27 samples collected for this project, with a focus on the improved soil column head where achieving solidification was particularly challenging due to the inconsistent soil properties at this depth.

Table 5 shows the results of the quality control tests. The standard deviation of un-confined compressive strength for the 27 specimens was calculated to be σ

n = 2561 kN/m

2. This value, along with the design standard strength F

c = 2600 kN/m

2, was used to determine the project's acceptance value (X

L) = 5929 kN/m

2 at a 10% failure ratio. The average compressive strength of the specimens exceeded this threshold, indicating that the im-proved soil column met the required quality standards. In addition, the coefficient of variation (33%) confirmed the homogeneity achieved within the improved soil columns despite the heterogeneous composition of the infill layer. This homogeneity was essential to ensure that the improved soil column would provide reliable and consistent support to the mat foundation of the building.

3.2.4. Excess Soil Management

Due to the removal of unsuitable black soil and obstructions from the fill layer, the project anticipated the generation of approximately 30 m3 of excess soil. This estimate was included in the design phase to prepare for efficient waste management and soil handling on site. During construction, the excavated material was carefully inspected by the construction manager and sorted based on its composition. This process ensured that only inappropriate or excess material was disposed of, thereby maintaining the integrity of the improved soil column.

On-site management of excess soil played a critical role in maintaining quality by allowing the project team to selectively remove unstable materials, thereby improving the structural integrity of the improved soil columns using SST. In addition, by directly managing excess soil, the project minimized environmental impact and reduced un-necessary waste disposal, in line with sustainable construction practices. This systematic approach to excess soil management ensured that the final improvement structure met both structural and environmental requirements, demonstrating the adaptability and efficiency of the SST in addressing complex urban geotechnical challenges.

4. Performance Evaluation Based on On-Site Application of the SST

The performance evaluation of the SST highlights its ability to construct improved soil columns with robust and highly load-bearing, even within the spatial constraints often encountered in densely populated urban environments. Urban construction often re-quires careful design and implementation of soil improvement due to constraints such as limited site access, existing infrastructure, and variable soil conditions. By overcoming these challenges, the SST demonstrates its utility and adaptability for improving soil stability.

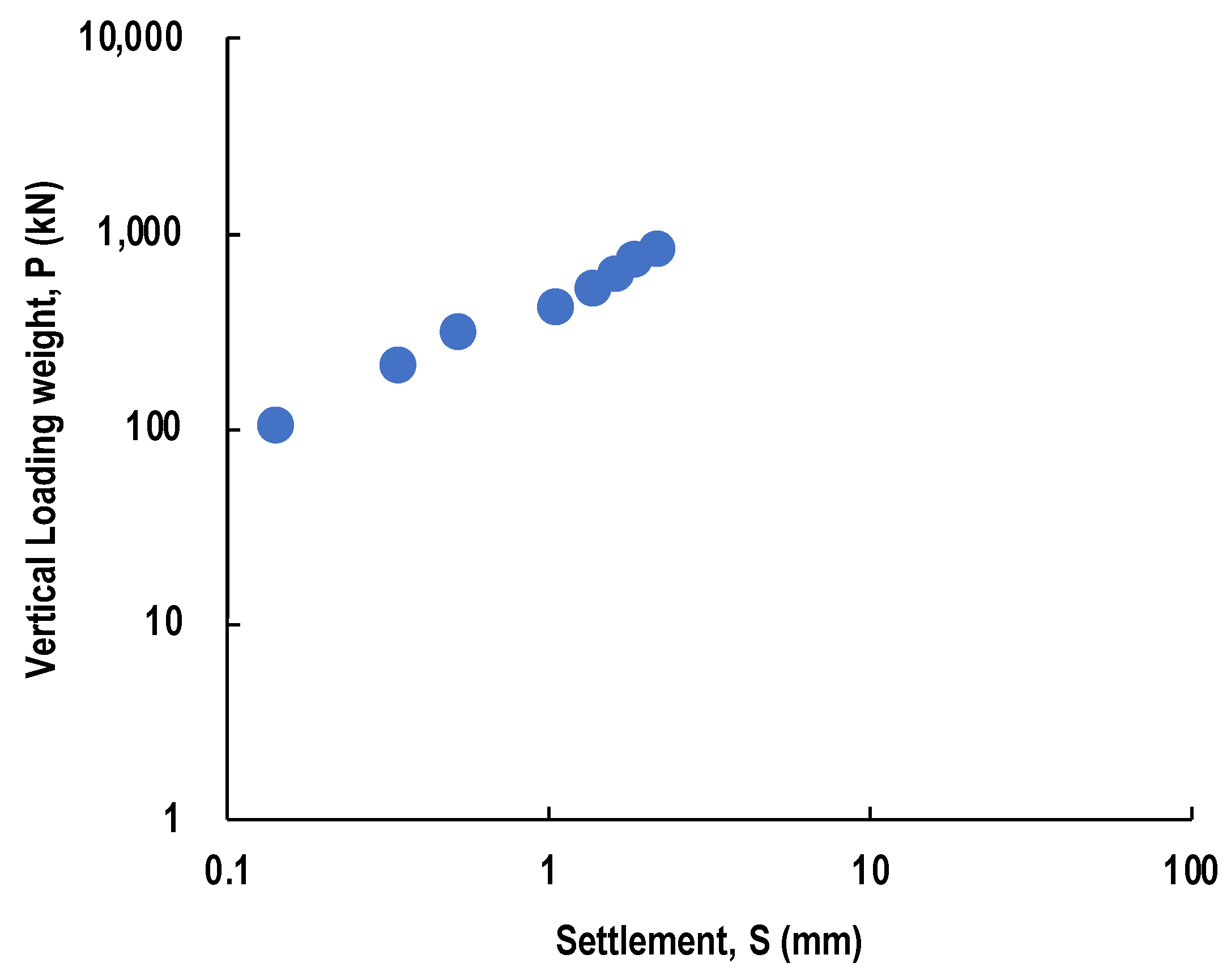

A vertical load test was conducted on a 600 mm diameter, 6.04 m long improved soil column constructed using the SST. The purpose of the test was to evaluate the ultimate load capacity of the improved soil column using the technologies specified in the JGS 1811-2002 [

40,

41,

42]. During the test, the maximum applied load reached 840 kN and was incrementally increased in eight steps per cycle to ensure precise load distribution and measurement of improved soil column response. This test protocol allowed accurate determination of the improved soil column for load capacity and deformation characteristics under realistic loading scenarios.

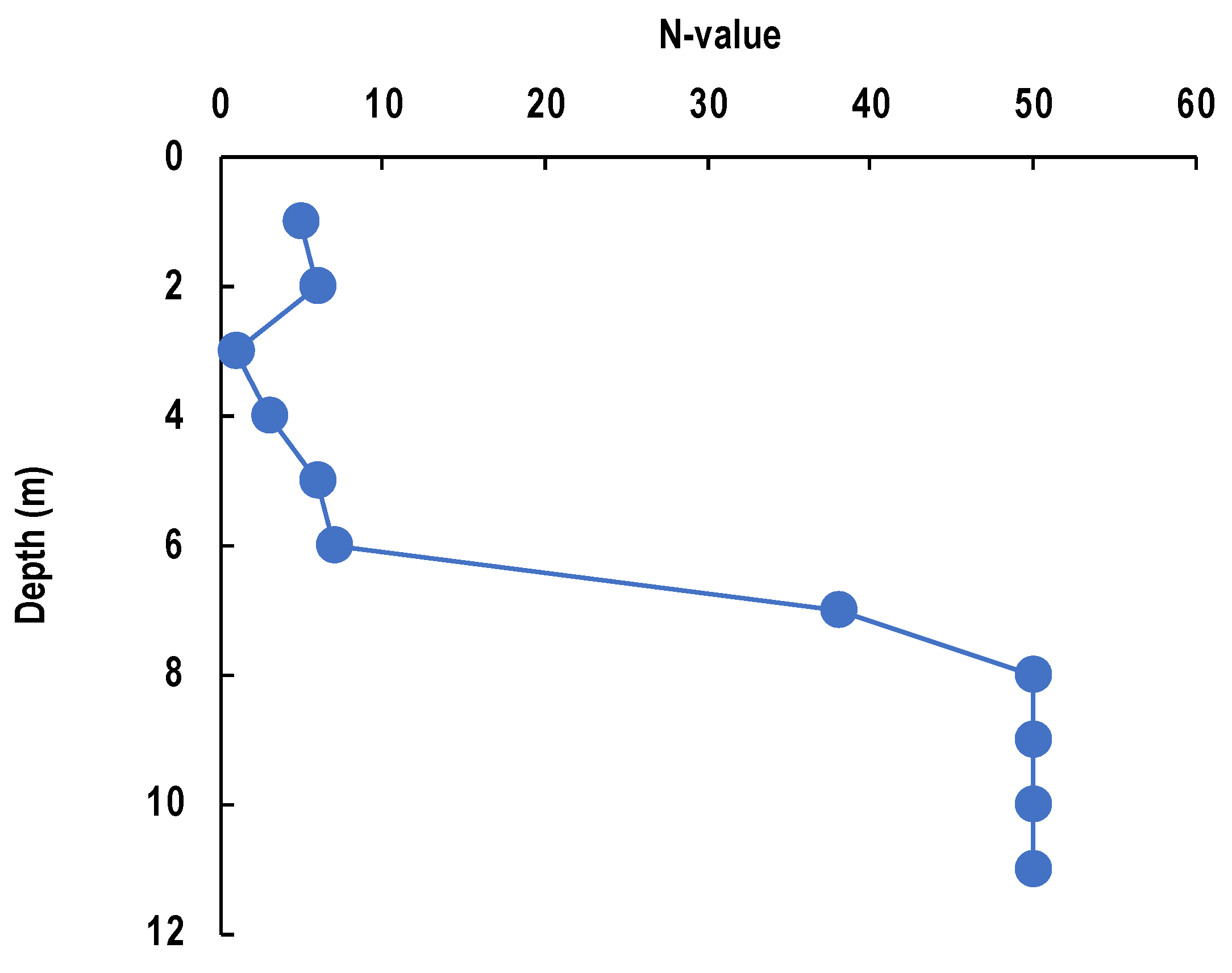

The results of the Standard Penetration Test (SPT) [

43,

44,

45], conducted at the same location as the vertical load test, are shown in

Figure 12. Analysis of the SPT results revealed a heterogeneous soil profile in the test area consisting of clay, sandy soil, clayey sand and gravel, and tuffaceous sandstone. This diverse soil composition often presents challenges for soil improvement due to variations in density, stiffness, and bearing capacity. The successful application of the SST in such a complex environment underscores its effectiveness and adaptability in dealing with mixed soil conditions.

Figure 13 shows the log P - log S curve obtained from the vertical load test on the improved soil column using SST. This curve illustrates the consistent and stable bearing capacity achieved, with a measured displacement of 2.16 mm at the 840 kN load step, which is significantly less than the 10% diameter displacement threshold of 60 mm. The minimal displacement observed demonstrates the structural integrity of the SST and its ability to provide reliable soil support under heavy loads. This characteristic is particularly critical for sites where controlling subsidence and limiting settlement are key factors in maintaining the structural stability of overlying or adjacent infrastructure.

Furthermore, during the load maintenance phase at 420 kN, the observed increase in displacement was only 0.46 mm, indicating negligible tilting or horizontal movement near the pile head. Such limited response suggests that the improved soil column using SST is not only effective in supporting static vertical loads, but also in maintaining stability against potential dynamic or lateral forces that may occur due to environmental or operational conditions.

The ability of improved soil columns using SST to meet or exceed the ultimate load capacity requirements for urban construction projects provides a strong foundation for their application in complex and diverse soil conditions. Their proven robustness makes them well suited for critical infrastructure such as buildings, bridges and other structures where high stability and minimal settlement are essential. In addition, the consistent performance of these improved soil columns under varying load conditions reflects the reliability and predictability of the SST, providing significant advantages to geotechnical engineers focused on optimizing safety, durability, and long-term performance in soil improvement applications.

5. Conclusions

This study has presented a comprehensive investigation of the Soil Squeezing Technology (SST) as an innovative approach to soil improvement, particularly suitable for space-constrained urban environments. SST has demonstrated the potential to address key limitations of conventional soil improvement technologies by providing a compact, efficient, and environmentally responsible solution. The results of this study highlight several key advantages and future directions for the SST as a robust urban geotechnical tool.

- (1)

The SST's reliance on compact and mobile equipment allows it to be used in tight, confined, and irregular urban areas where conventional soil improvement equipment cannot operate efficiently. The ability to perform soil improvement in such confined spaces makes SST particularly advantageous for modern urban infra-structure projects, which often face logistical and spatial constraints. This adaptability is critical to advancing urban development while minimizing disruption to sur-rounding structures and existing infrastructure.

- (2)

SST's simplified process eliminates the need for extensive in-situ mixing equipment, large machinery and lengthy set-up times, significantly reducing project costs and schedules. The ease of deployment provided by the SST process addresses both budgetary and operational constraints, allowing for faster and more efficient con-struction, which is highly beneficial in densely populated urban areas.

- (3)

Compared to conventional technologies that require significant water and energy inputs, SST operates with a minimal environmental footprint, using little to no water and avoiding energy-intensive mixing processes. By emphasizing compaction-based soil improvement with targeted consolidation, SST addresses the growing need for sustainable practices in urban construction, where minimizing environmental im-pact is increasingly a priority.

- (4)

The SST consistently achieves high-density, improved cohesive soil columns that exhibit uniform strength and stability in a variety of soil types, including humus-rich and organic soils that conventionally challenge soil improvement efforts. By employing controlled displacement and compaction mechanisms, SST ensures homogeneity within the improved soil columns, meeting stringent engineering standards for bearing capacity and structural integrity. This performance characteristic is critical to maintaining resilient urban infrastructure.

- (5)

The SST's operational simplicity, reduction in the need for large equipment, and reduced logistical requirements make it a cost-effective solution for urban geotechnical projects. These factors are particularly beneficial in sites with limited access, further establishing SST as a viable option for urban developments requiring optimized resource allocation.

Although the SST offers significant improvements over conventional soil improvement technologies, further research is needed to refine and improve its applicability and efficiency. The following areas represent promising directions for advancing the SST:

- (1)

Further studies are needed to optimize the ratios of sand, cement-based solidifiers, and other potential additives to improve performance in various soil conditions. This research could lead to more cost-effective formulations that reduce material use while maintaining or improving structural standards.

- (2)

While this study confirms the immediate effectiveness of SST, additional research on the long-term durability and performance of improved soil columns using SST under various loading conditions and environmental exposures will provide valuable in-sights. Evaluation of factors such as settlement behavior, resistance to moisture fluctuations, and structural stability over extended periods of time are essential to establishing the viability of SST for long-term urban applications.

- (3)

To further expand the use of SST in exceptionally confined spaces, efforts to miniaturize SST equipment should be considered. The development of more compact, modular equipment could enable applications in extremely confined areas, such as narrow underground spaces or adjacent to existing structures.

- (4)

Incorporating real-time monitoring tools, such as sensors for compaction quality, soil density, and moisture content, would improve quality control during SST operations. Real-time data could enable adaptive adjustments to ensure optimal compaction and cohesion in different soil types and contribute to the overall reliability of the process.

- (5)

While SST is designed to be an environmentally sustainable process, detailed comparative studies are needed to quantify resource efficiency, emissions, and waste reduction. Such analyses will provide quantifiable evidence of the environmental benefits of SST and support its adoption as a green urban geotechnical solution.

The SST represents a significant advancement in urban soil improvement, combining simplicity, environmental responsibility, and high adaptability. Through continued optimization and technology integration, SST has significant potential to shape future urban geotechnical practice and support the development of resilient, sustainable infra-structure within the complexities of modern urban landscapes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.I. and G.C.; methodology, G.C.; software, T.I. and T.Y.; validation, G.C. and S.I.; formal analysis, T.I. and T.Y.; investigation, T.I. and T.Y.; resources, G.C. and S.I.; data curation, T.I. and G.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.I.; writing—review and editing, S.I.; visualization, S.I.; supervision, G.C., T.Y. and S.I.; project administration, S.I.; funding acquisition, S.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kitazume, M. and Terashi, M. (2015). Fundamentals of Deep Mixing Technology. CRC Press.

- Broere, W. Urban underground space: Solving the problems of today’s cities. Tunnelling and under-ground space technology 2016, 55, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelton, P. and Murphy, B. (2021). Understanding soils in urban environments. Csiro pub-lishing.

- Maltman, A. (2018). Vineyards, rocks, and soils: the wine lover's guide to geology. Oxford University Press.

- Han, J. (2015). Principles and practice of ground improvement. John Wiley & Sons.

- Patel, A. (2019). Geotechnical investigations and improvement of ground conditions. Woodhead Publishing.

- Gupta, S. and Kumar, S. A state-of-the-art review of the deep soil mixing technique for ground improvement. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions 2023, 8, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marik, S. , Ransinchung, G. D., Mondal, A. and Kumar, D. (2024). Characterization of cement-modified mixtures and their typical characteristics: a review. Journal of Building Engineering, 110526. [CrossRef]

- Kibert, C.J. (2016). Sustainable construction: green building design and delivery. John Wiley & Sons.

- Stokke, R. , Qiu, X., Sparrevik, M., Truloff, S., Borge, I. and De Boer, L. Procurement for ze-ro-emission construction sites: a comparative study of four European cities. Environment Systems and Decisions 2023, 43, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boysen, N. , Emde, S., Hoeck, M. and Kauderer, M. Part logistics in the automotive industry: De-cision problems, literature review and research agenda. European Journal of Operational Research 2015, 242, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachofner, M. , Lemardelé, C., Estrada, M. and Pagès, L. City logistics: Challenges and oppor-tunities for technology providers. Journal of urban mobility 2022, 2, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikuma, H. , Iida, T. , Yamada, T. and Inazumi, S. Field applications of columnar ground-improvement method by replacement, compaction and solidification. Journal of the Society of Materials Science, Japan 2022, 71, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J. (2017). The mechanics of soils and foundations. CRC press.

- Maroof, M. A. , Mahboubi, A., Vincens, E. and Noorzad, A. Effects of particle morphology on the minimum and maximum void ratios of granular materials. Granular Matter 2022, 24, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerke, J. Concepts and misconceptions of humic substances as the stable part of soil organic matter: A review. Agronomy 2018, 8, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.O. , Chen, X.B. and Kim, T.W. Opportunities and challenges of modular methods in dense urban environment. International journal of construction management 2019, 19, 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, J. , Araldi, A., Fusco, G. and Fuse, T. The character of urban Japan: Overview of Osa-ka-Kobe’s cityscapes. Urban Science 2019, 3, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melenbrink, N. , Werfel, J. and Menges, A. On-site autonomous construction robots: To-wards unsupervised building. Automation in construction 2020, 119, 103312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melenbrink, N. , Werfel, J. and Menges, A. On-site autonomous construction robots: To-wards unsupervised building. Automation in Construction 2020, 119, 103312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. T. and Munshi-South, J. Evolution of life in urban environments. Science 2017, 358, eaam8327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S. and Bhalla, S.K. Role of geotechnical properties of soil on civil engineering structures. Resources and Environment 2017, 7, 103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Archibong, G.A. , Sunday, E.U., Akudike, J.C., Okeke, O.C. and Amadi, C. A review of the principles and methods of soil stabilization. International Journal of Advanced Academic Research| Sciences 2020, 6, 2488–9849. [Google Scholar]

- Amundson, R. , Berhe, A.A., Hopmans, J.W., Olson, C., Sztein, A.E. and Sparks, D.L. (2015). Soil and human security in the 21st century. Science, 348. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.L. and Zhang, G.L. Formation, characteristics and eco-environmental implications of urban soils–A review. Soil science and plant nutrition 2015, 61 (Suppl. 1), 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El May, M. , Dlala, M. and Chenini, I. Urban geological mapping: Geotechnical data analysis for rational development planning. Engineering Geology 2010, 116, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S. , Moghal, A.A.B. and Yao, J.L. (2021). Advances in Urban Geotechnical Engineering. Proceedings of the 6th GeoChina International Conference on Civil & Transportation Infrastructures: From Engineering to Smart & Green Life Cycle Solutions, Springer, Nanchang, China.

- Brenner, N. and Schmid, C. Towards a new epistemology of the urban? City 2015, 19, 151–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamsawang, P. , Jamnam, S., Jongpradist, P., Tanseng, P. and Horpibulsuk, S. Numerical analysis of lateral movements and strut forces in deep cement mixing walls with top-down construction in soft clay. Comput-ers and Geotechnics 2017, 88, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, H. (2023). Ground Improvement for Coastal Engineering. CRC Press.

- Cuevas, J. , Daliakopoulos, I.N., del Moral, F., Hueso, J.J. and Tsanis, I.K. A review of soil-improving cropping systems for soil salinization. Agronomy 2019, 9, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. , Jiao, H., Han, L., Shen, L., Du, W., Ye, Q. and Yu, G. Real-time monitoring of construction quality for gravel piles based on Internet of Things. Automation in Construction 2020, 116, 103228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. , Liu, Q., Liu, H., Zhang, P., Pan, S., Zhang, X. and Fang, J. Development and in-situ ap-plication of a real-time monitoring system for the interaction between TBM and surrounding rock. Tunnelling and Under-ground Space Technology 2018, 81, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endicott, L. J. Challenges in going underground in big cities. Geotechnical Engineering Journal of the SEAGS & AGSSEA 2015, 46, 121–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, B.G. , Zhu, L. and Ming, J.T.T. Factors affecting productivity in green building construc-tion projects: The case of Singapore. Journal of Management in Engineering 2017, 33, 04016052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.G. , Winter, M.G. and Puppala, A.J. A review of sustainable approaches in transport infrastructure geotechnics. Transportation Geotechnics 2016, 7, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T. and Dahlgren, R.A. Nature, properties and function of aluminum–humus complexes in volcanic soils. Geoderma 2016, 263, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kögel-Knabner, I. and Amelung, W. Soil organic matter in major pedogenic soil groups. Geoderma 2021, 384, 114785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Building Center of Japan (BCJ) (2018). Design and Quality Control Guidelines of Improved Ground for Buildings (2018 edition). 338-352.

- Zhang, F. , Kimura, M., Nakai, T. and Hoshikawa, T. Mechanical behavior of pile foundations subjected to cyclic lateral loading up to the ultimate state. Soils and Foundations 2000, 40, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Japanese Geotechnical Society (JGS) (2002). Standards of Japanese Geotechnical Society for Vertical Load Tests of Piles (English Version). The Japanese Geotechnical Society.

- Hussien, M.N. , Tobita, T., Iai, S. and Karray, M. On the influence of vertical loads on the lateral response of pile foundation. Computers and Geotechnics 2014, 55, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.D. Subsurface exploration using the standard penetration test and the cone penetrometer test. Environmental & Engineering Geoscience 2006, 12, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, N.Q.A.M. and Zabidi, H. Reliability of using standard penetration test (SPT) in pre-dicting properties of soil. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2018, 1082, 012094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazoh, H.N. and Mallo, S.J. Standard penetration test in engineering geological site in-vestigations – A review. The International Journal of Engineering and Science 2014, 3, 40–48. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).