Submitted:

30 November 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2. Materials and Methods

4. Results

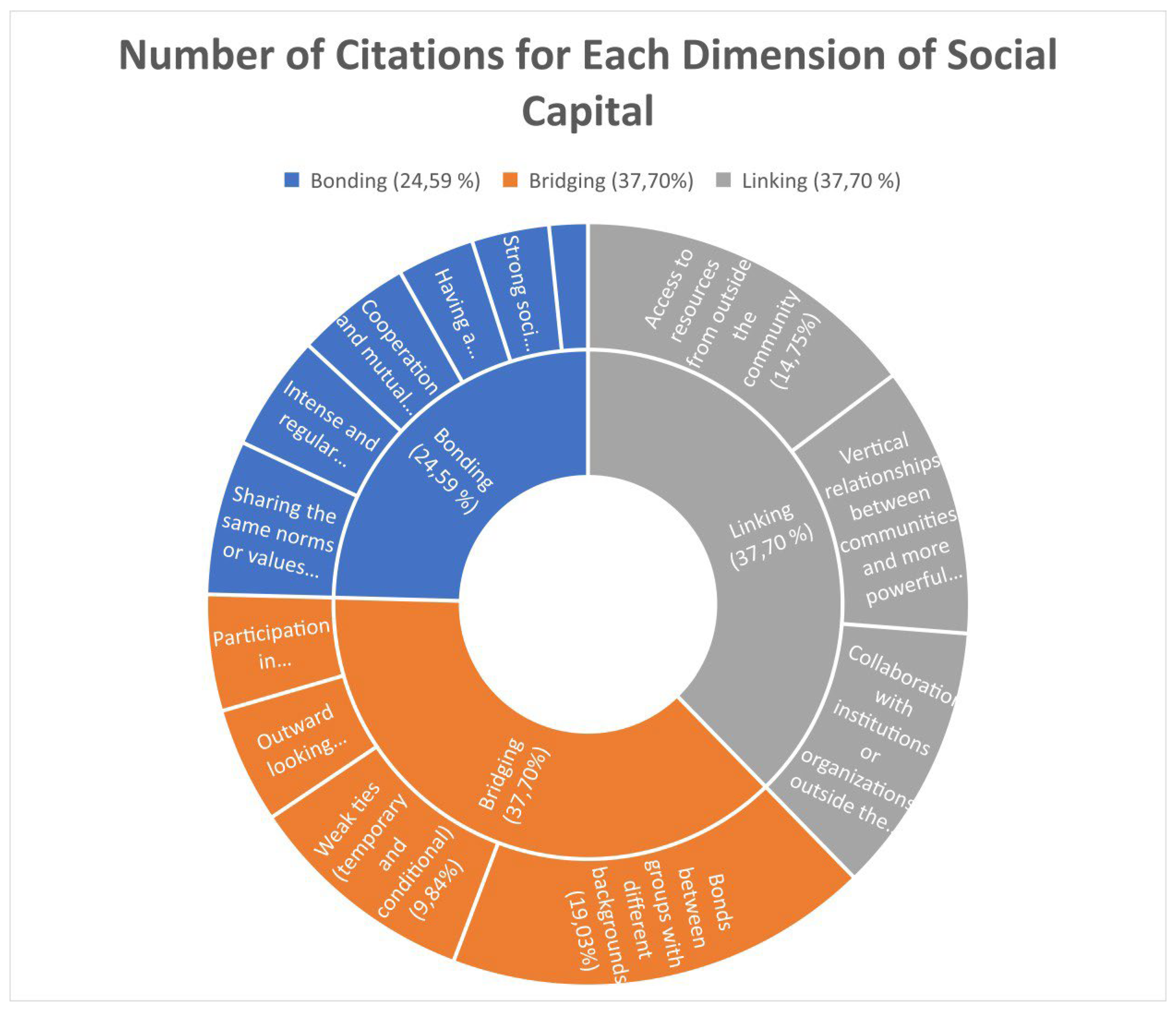

| No. | Category of Bonding Characteristics | Bonding Aspects |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | The presence of robust social connections within homogenious groups | Traditional ritual continue during the pandemic Perhutani's communication with the community during the pandemic |

| 2. | Co-operation and helping each other | Tourism managers must be local residents Using neighbouring labour |

| 3. | Intens and regular interactions | Meetings are usually at the home of the head of the Farmer Group or the administrator of the Forest Village Community Organisation (LMDH) Non-formal meeting are more frequent: when meeting in the field |

| 4. | Sharing the same norms or values | Communication via WhatsApp No labor move from the village |

| 5. | Have a common goal or interest | As pandemic labor returns to agriculture Pattern of cooperation between middlemen and farmers |

| 6. | Participation in group activities or organizations | Farmer group meeting around once every 3-4 months |

| No. | Category of Bridging Characteristics | Bridging Aspects |

| 1. | Bonding between groups with different backgrounds | Farmers cooperate with middlemen Farmers cooperate with the company PT Segar Laris Niaga The government provides garlic seedlings Farmers learned apple cultivation from other areas (Batu and Poncokusumo) Farmer group organizations with members from severalvillages Paguyuban ‘nundan’ (horse transport in Bromo crater) has members from 5 villages Vegetable marketing to other islands (Kalimantan and Papua) Division of tasks between Ladesta (Village Tourism Organisation) and Middleman ini apple-picking agro-tourism) Cooperation Agreement (PKS) between farmers and Perhutani Cooperation between Ladesta (Lembaga Desa Wisata) and Travel agents in Jakarta Farmer group meetings are only held once every 3-4 months |

| 2. | Weak bonds (temporary and conditional) | Forest Village Community Organisation (LMDH) meeting are no longer regular Assistance in the construction of HIPAM (Drinking Water Management Association) from the Govermentad community self-help Government agricultural extension officers are inactive Change in Seruni tourism management from village to local government |

| 3. | Participation in heterogeneous groups or organizations | Communities involved in conservation activities carried out by TNBTS (Bromo Tengger Semeru National Park) Training from TNBTS involves various stakeholders |

| 4. | Outward-looking | Shipping vegetables out of town during the pandemic Farming facilities kiosks serve farmers from 4 villages Communities are invited to study elsewhere to learn |

| No. | Category of Linking Characteristic | Linking Aspects |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Collaboration with institutions or organisations outside the community | Cooperation between HIPAM (Association of Drinking Water Managers), TNBTS (Bromo Tengger Semeru National Park and Perhutani in managing water source Cooperation between LMDH (Forest Village Community Organisation) and Perhutani Community cooperation with TNBTS in conservation activities Ladesta cooperation with local government Farmer cooperation with fertilizer company PT Gresik Cipta Sejahtera |

| 2. | Vertical relationship between the community and more powerful parties | Mechanism for applying for land and water resource utilization permits to Perhutani Mechanism for submitting water source proposals to TNBTS Perhutani regulations for ‘pesanggem’ farmers and traders Obligations of ‘nundan’ paguyuban members to TNBTS |

| 3. | Acsess to resources from outside the community | Assistance with seeds, fertilizers and agricultural inputs from the government APBN funding for tourism village development Assistance for the contruction of clean water facilities (HIPAM) from the Government Social assistance such as BLT (Direct Cash Assistance) and basic foodstuffs from the Government during a pandemic |

| Ecology | Social | Economic | |

| Bonding | 26 | 27 | 29 |

| Bridging | 15 | 26 | 24 |

| Linking | 16 | 16 | 22 |

| Ecology | Social | Economic | |

| Bonding | The transfer of local agricultural and water management knowled ge through hereditary means The utilization of local labor (neighbors/ family) in agricultural activities The adoption of sustainable agricultural practices, including the use of organic fertilizer and intercropping The application of local wisdom for Environmental conservation, such as planting trees to prevent landslides |

Helping each other during the pandemic and the closure of tourist attractions Self-help contributions and gotong royon for village slametan Use of sufficient manure by apple farmers Hiring farm laborers from neighbours and families Equal distribution of homestay guests throughout the village |

Revenue sharing from homestay management and tour packages Joint land management by farmer groups Informal credit system for agricultural production facilities Division of tasks in the tourist village institution (Ladesta) Joint management of water resources (HIPAM) Cooperation between middlemen and farmers Tourism management by local villagers Association fees |

| Bridging | Regular coordination between Lawang Sari, LMDH, and Perhutani for land management Gubukklakah farmers learn apple cultivation from Nongkojajar and Poncokusumo farmers Community partnership with TNBTS through the Masyarakat Mitra Polhut and Masyarakat Peduli Api programmes Joint management of the Coban Pelangi water source by several villages 1000 tree planting program involving various parties Development of agro-tourism by LADESTA that connects agriculture with tourism LMDH and pine resin tappers The exchange of information between farmers on sustainable farming practices. |

The LMDH coordinates regularly with Perhutani, convening on Fridays for a legi meeting. The LMDH serves as a forum for villagers to engage with Perhutani. The Dance Studio "Lintang Pandu Sekar" facilitates children's activities. Nundan community meetings, held in five villages, address matters related to cleanliness and greening. Ladesta members convene regularly on Wednesdays to organize tourists |

Cooperation with over 40 travel agents in Jakarta Development of agro-tourism that connects local farmers with tourists Homestay system that connects local residents with tourists Cooperation with Perhutani through LMDH Marketing of agricultural products to Kalimantan and Papua Cooperation with investors outside the region Access to financial services such as KUR from BNI |

| Linking | Cooperation between TNBTS, Perhutani and the community to protect water sources through HIPAM Licensing system and profit sharing for farmers' use of Perhutani land through LMDH Annual monitoring of water sources by Perhutani and meetings with stakeholders Government support in the form of apple seed and storage facilities (cold storage) for farmers Management and evaluation of TNBTS with the community under the Ministry of Environment and Forestry Mechanism for Perhutani to apply for a water source extraction permit from the village government Collaboration between community and officials on forest fire management and prevention Support from the Department of Agriculture to develop apple products in the village |

Ladesta coordination with Perhutani regarding events or traditional ceremonies Perhutani meeting with related parties to discuss new water sources Joint reforestation activities between Perhutani and the community The existence of LMDH is a forum for coordinating vegetable farmers on Komplangan land related to Perhutani |

Access to BNI's KUR for business capital Government support for HIPAM APBN funds for the development of tourist villages Partnership between garlic farmers and companies Cultivation training from the Department of Agriculture and partner companies Government fertilizer subsidies Government support for homestay construction Perhutani permission to sell in tourist areas |

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Patents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Z. Yang, S. Yang, R. Yang, and Q. Wu, “A Study on Spatiotemporal Changes of Ecological Vulnerability in Yunnan Province Based on Interpretation of Remote Sensing Images,” Diversity, vol. 15, no. 9, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Li, Y. Hui, and J. Pan, “Evolution and Influencing Factors of Social-Ecological System Vulnerability in the Wuling Mountains Area,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, vol. 19, no. 18, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Thomas et al., “Explaining differential vulnerability to climate change: A social science review,” Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang., vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 1–18, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Adrianto, D. V. Spracklen1, and S. R. Arnold, “Relationship between fire and forest cover loss in Riau Province, Indonesia between 2001 and 2012,” Forests, vol. 10, no. 10, pp. 1–19, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Rahman et al., “Climate Disasters and Subjective Well-Being among Urban and Rural Residents in Indonesia,” Sustain., vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 1–14, 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Simane, B. F. Zaitchik, and J. D. Foltz, “Agroecosystem specific climate vulnerability analysis: application of the livelihood vulnerability index to a tropical highland region,” Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 39–65, 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Chen, J. Cao, H. Zhu, and Y. Wang, “Understanding Household Vulnerability and Relative Poverty in Forestry Transition: A Study on Forestry-Worker Families in China’s Greater Khingan Mountains State-Owned Forest Region,” Sustain., vol. 14, no. 9, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Vignola et al., “Ecosystem-Based Practices for Smallholders’ Adaptation to Climate Extremes: Evidence of Benefits and Knowledge Gaps in Latin America,” Agronomy, vol. 12, no. 10, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Conti, M. Battaglia, M. Calabrese, and C. Simone, “Fostering sustainable cities through resilience thinking: The role of nature-based solutions (NBSS): Lessons learned from two Italian case studies,” Sustain., vol. 13, no. 22, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sumarmi, “Understanding the Forest Conservation Society actions ‘Tengger’ ethnic Based Local Wisdom ‘Sesanti Panca Setya’ in East Java - the Republic of Indonesia,” pp. 1623–1627, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Utami, Antariksa, and D. K. Santoso, “Local Wisdom of Farmers in Ngadas Village, Malang Regency in the Management of Agricultural Landscapes,” pp. 65–68, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Ismanto, N. Kumoro, H. Kadir, and I. Martias, “Continuity and Change in the Midst of Ecological and Livelihood Transformation in Tengger East Java,” Proc. 1st Int. Semin. Cult. Sci. ISCS 2020, 4 Novemb. 2020, Malang, Indones., 2021. [CrossRef]

- O. H. Nurcahyono, “Social Capital of Indigenous Village Communities in Maintaining Social Harmony (Case Study of The Tenggerese Indigenous Community, Tosari, Pasuruan, East Java),” Proc. Int. Conf. Rural Stud. Asia (ICoRSIA 2018), 2019. [CrossRef]

- U. Romadi, K. Hidayat, K. Sukesi, and Y. Yuliati, “Reconstruction of the Social Capital-Based Agricultural Extension System in the Tengger Tribe Society in Tosari, Pasuruan, East Java, Indonesia,” AGRIEKONOMIKA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Susanto, P. Nugroho, and S. Numata, “Traditional ecological knowledge for monitoring Anaphalis javanica (DC.) Sch.Bip. (Asteraceae) in Bromo Tengger Semeru National Park, Indonesia,” Environ. Monit. Assess., vol. 196, no. 8, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. N. Rahman et al., “Muslim-Hindu Cooperation in Addressing Social Problems in the Tengger Tribe in East Java, Indonesia,” J. Multidisiplin Madani, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhao, X. Zhang, W. Jiang, and T. Feng, “Does second-order social capital matter to green innovation? The moderating role of governance ambidexterity,” Sustain. Prod. Consum., vol. 25, pp. 271–284, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. O. Olagunju, A. I. Ogunniyi, Z. Oyetunde-Usman, A. O. Omotayo, and B. A. Awotide, “Does agricultural cooperative membership impact technical efficiency of maize production in Nigeria: An analysis correcting for biases from observed and unobserved attributes,” PLoS One, vol. 16, no. 1 January, pp. 1–22, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. O. Olarinde et al., “The influence of social networking on food security status of cassava farming households in Nigeria,” Sustain., vol. 12, no. 13, pp. 1–35, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. I. Nor Diana, N. A. Zulkepli, C. Siwar, and M. R. Zainol, “Farmers’ Adaptation Strategies to Climate Change in Southeast Asia: A Systematic Literature Review,” Sustain., vol. 14, no. 6, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Von Essen and M. P. Allen, “The republican zoopolis towards a new legitimation framework for relational animal ethics,” Ethics Environ., vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 61–88, 2016. [CrossRef]

- L. T. H. Phuong, T. D. Tuan, and N. T. N. Phuc, “Transformative social learning for agricultural sustainability and climate change adaptation in the Vietnam Mekong Delta,” Sustain., vol. 11, no. 23, 2019. [CrossRef]

- I. Pérez-Ramírez, M. García-Llorente, C. Saban de la Portilla, A. Benito, and A. J. Castro, “Participatory collective farming as a leverage point for fostering human-nature connectedness,” Ecosyst. People, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 222–234, 2021. [CrossRef]

- I. Z. A. D. P. No, J. K. Hellerstein, and D. Neumark, “DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Social Capital , Networks , and Economic Wellbeing Social Capital , Networks , and Economic Wellbeing,” no. 13413, 2020.

- T. Claridge, “Functions of social capital – bonding, bridging, linking,” Soc. Cap. Res., pp. 1–7, 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Villalonga-Olives, E. Villalonga-Olives, and I. Kawachi, “The measurement of bridging social capital in population health research.,” Health Place, vol. 36, pp. 47–56, 2015. [CrossRef]

- B. Rudito, M. Famiola, and P. Anggahegari, “Corporate Social Responsibility and Social Capital: Journey of Community Engagement toward Community Empowerment Program in Developing Country,” Sustain., vol. 15, no. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Claridge, “Introduction to Social Capital Theory,” Soc. Cap. Res., no. August, pp. 2–9, 2018, [Online]. Available: https://www.socialcapitalresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/edd/2018/08/Introduction-to-Social-Capital-Theory.pdf.

- D. Salman, K. Kasim, A. Ahmad, and N. Sirimorok, “Combination of bonding, bridging and linking social capital in a livelihood system: Nomadic duck herders amid the covid-19 pandemic in South Sulawesi, Indonesia,” For. Soc., vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 136–158, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Myeong and H. Seo, “Which type of social capital matters for building trust in government? Looking for a new type of social capital in the governance era,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 8, no. 4. 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. L. Hawkins and K. Maurer, “Bonding, bridging and linking: How social capital operated in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina,” Br. J. Soc. Work, vol. 40, no. 6, pp. 1777–1793, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, X. Deng, C. Wong, Z. Li, and J. Chen, “Learning urban resilience from a social-economic-ecological system perspective: A case study of Beijing from 1978 to 2015,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 183, pp. 343–357, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Terano, Z. Mohamed, M. N. Shamsudin, and I. A. Latif, “Factors influencing intention to adopt sustainable agriculture practices among paddy farmers in Kada, Malaysia,” Asian J. Agric. Res., vol. 9, no. 5, pp. 268–275, 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Azman, J. L. D’Silva, B. A. Samah, N. Man, and H. A. M. Shaffril, “Relationship between attitude, knowledge, and support towards the acceptance of sustainable agriculture among contract farmers in Malaysia,” Asian Soc. Sci., vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 99–105, 2013. [CrossRef]

- F. Sikandar, V. Erokhin, L. Xin, M. Sidorova, A. Ivolga, and A. Bobryshev, “Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Poverty Eradication in Pakistan: The Role of Foreign Aid and Government Policies,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 14, no. 22. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Weiner, “Applying plant ecological knowledge to increase agricultural sustainability,” J. Ecol., vol. 105, no. 4, pp. 865–870, 2017. [CrossRef]

- J. Cao and Y. A. Solangi, “Analyzing and Prioritizing the Barriers and Solutions of Sustainable Agriculture for Promoting Sustainable Development Goals in China,” Sustain., vol. 15, no. 10, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Waseem, G. E. Mwalupaso, F. Waseem, H. Khan, G. M. Panhwar, and Y. Shi, “Adoption of sustainable agriculture practices in banana farm production: A study from the Sindh Region of Pakistan,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, vol. 17, no. 10, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Q. Guo, O. Ola, and E. O. Benjamin, “Determinants of the adoption of sustainable intensification in southern african farming systems: A meta-analysis,” Sustain., vol. 12, no. 8, pp. 1–13, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Sharna, A. R. Anik, S. Rahman, and M. A. Salam, “Impact of Social, Institutional and Environmental Factors on the Adoption of Sustainable Soil Management Practices: An Empirical Analysis from Bangladesh,” Land, vol. 11, no. 12, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Hildeń, P. Jokinen, and J. Aakkula, “The sustainability of agriculture in a northern industrialized country - From controlling nature to rural development,” Sustainability, vol. 4, no. 12, pp. 3387–3403, 2012. [CrossRef]

- D. Tilman, M. Clark, D. R. Williams, K. Kimmel, S. Polasky, and C. Packer, “Future threats to biodiversity and pathways to their prevention,” Nature, vol. 546, no. 7656, pp. 73–81, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Meier, F. Stoessel, N. Jungbluth, R. Juraske, C. Schader, and M. Stolze, “Environmental impacts of organic and conventional agricultural products - Are the differences captured by life cycle assessment?,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 149, pp. 193–208, 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. C. Ponisio, L. K. M’gonigle, K. C. Mace, J. Palomino, P. De Valpine, and C. Kremen, “Diversification practices reduce organic to conventional yield gap,” Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci., vol. 282, no. 1799, 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Rawat et al., “Rejuvenating ecosystem services through reclaiming degraded land for sustainable societal development: Implications for conservation and human wellbeing,” Land use policy, vol. 112, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Khwidzhili, R. H.2 & Worth, “THE SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE IMPERATIVE: IMPLICATIONS FOR SOUTH AFRICAN AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION,” South African J. Agric. Ext., vol. 44, 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Ruslan and H. Khalid, “Unpacking Social Capital as a Determinant of Sustainable Agriculture Adoption: A Literature Review,” Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci., 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Widjayanthi, “Learning From Community Practices: Social Capital of Farming Communities in Supporting Sustainable Agriculture,” J. La Lifesci, 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Hinduja, R. F. Mohammad, S. Siddiqui, S. Noor, and A. Hussain, “Sustainability in Higher Education Institutions in Pakistan: A Systematic Review of Progress and Challenges,” Sustain., vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 1–19, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. K. Lim, M. S. Haufiku, K. L. Tan, M. Farid Ahmed, and T. F. Ng, “Systematic Review of Education Sustainable Development in Higher Education Institutions,” Sustain., vol. 14, no. 20, pp. 1–22, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Al-Nuaimi and S. G. Al-Ghamdi, “Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice towards Sustainability Aspects among Higher Education Students in Qatar,” Sustain., vol. 14, no. 20, 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. M. Adams, R. L. Pressey, and J. G. Álvarez-Romero, “Using optimal land-use scenarios to assess trade-offs between conservation, development, and social values,” PLoS One, vol. 11, no. 6, pp. 1–20, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Kalogiannidis, D. Kalfas, G. Giannarakis, and M. Paschalidou, “Integration of Water Resources Management Strategies in Land Use Planning towards Environmental Conservation,” Sustain., vol. 15, no. 21, pp. 1–20, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Bayramoglu and A. I. Kadiogullari, “Analysis of land use change and forestation in response to demographic movement and reduction of forest crime,” Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 225–238, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Z. Hloušková, M. Lekešová, A. Prajerová, and T. Doucha, “Assessing the Economic Viability of Agricultural Holdings with the Inclusion of Opportunity Costs,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 14, no. 22. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Smedzik-Ambrozy, M. Guth, S. Stepień, and A. Brelik, “The influence of the European union’s common agricultural policy on the socio-economic sustainability of farms (the case of Poland),” Sustain., vol. 11, no. 24, 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Weng et al., “Assessing the vulnerability to climate change of a semi-arid pastoral social–ecological system: A case study in Hulunbuir, China,” Ecol. Inform., vol. 76, no. May, p. 102139, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Naderifar, H. Goli, and F. Ghaljaie, “Snowball Sampling: A Purposeful Method of Sampling in Qualitative Research,” Strides Dev. Med. Educ., vol. 14, no. 3, 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Phelps and D. Kelly, “A call for collaboration: Linking local and non-local rangeland communities to build resilience,” Rangel. J., vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 265–275, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Call and P. Jagger, “Social capital, collective action, and communal grazing lands in Uganda,” Int. J. Commons, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 854–876, 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. E. W. Termeer, K. Soma, N. Motovska, O. I. Ayuya, M. Kunz, and T. Koster, “Sustainable Development Ensued by Social Capital Impacts on Food Insecurity: The Case of Kibera, Nairobi,” Sustain., vol. 14, no. 9, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Hoppe, I. Fritsche, and P. Chokrai, “The ‘I’ and the ‘We’ in Nature Conservation—Investigating Personal and Collective Motives to Protect One’s Regional and Global Nature,” Sustain., vol. 15, no. 5, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. A. Johnson, M. J. Eaton, J. Mikels-Carrasco, and D. Case, “Building adaptive capacity in a coastal region experiencing global change,” Ecol. Soc., vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 1–22, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Jordan, “Swimming alone? The role of social capital in enhancing local resilience to climate stress: a case study from Bangladesh,” Clim. Dev., vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 110–123, 2015. [CrossRef]

- T. Fu and S. Mao, “Individual Social Capital and Community Participation: An Empirical Analysis of Guangzhou, China,” Sustain., vol. 14, no. 12, pp. 1–14, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Giovannetti, P. Bertolini, and M. Russo, “Rights, commons, and social capital: The role of cooperation in an italian agri-food supply chain,” Sustain., vol. 13, no. 21, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Cheevapattananuwong, C. Baldwin, A. Lathouras, and N. Ike, “Social capital in community organizing for land protection and food security,” Land, vol. 9, no. 3, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. H. Xie, L. P. Wang, and B. F. Lee, “Understanding the Impact of Social Capital on Entrepreneurship Performance: The Moderation Effects of Opportunity Recognition and Operational Competency,” Front. Psychol., vol. 12, no. June, 2021. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).