1. Introduction

Point clouds are nowadays commonly used to describe object surfaces, including the surface of the Earth. Unlike standard geodetic methods using, e.g., total station or a geodetic GNSS-RTK receiver measuring individual significant terrain points, point clouds are typically non-selectively acquired in quasi-regular grids using, e.g., airborne laser scanning (ALS) [

1], terrestrial 3D scanning [

2], photogrammetry [

3], or mobile laser scanning systems mounted on terrestrial vehicles [

4]. More recently, unmanned airborne vehicles (UAVs) equipped with cameras [

5] and/or lidar systems [

6] have become widely used for this purpose and lately, a great improvement in the quality and reliability of measurements has been observed in mobile (typically operator-carried) SLAM (simultaneous localization and mapping) scanners [

7] that can be successfully used even in areas without GNSS signal and with limited visibility (such as underground spaces) [

8,

9].

All point clouds, regardless of their different character (density, absolute or relative accuracy, origin, etc.), inherently include points that do not represent the surface of interest and need to be filtered out using one or more filtering methods. Extraction of points representing ground (ground filtering, vegetation filtering) is a typical example of such filtering. Many methods and algorithms for this process have been developed, typically based on a single attribute allowing us to distinguish between points of interest and other points. The selection of the filtering method depends, among other things, also on the sensor type; the suitability of individual filters for data acquired using different types of sensors is discussed in systematic reviews [

10,

11,

12].

The most common filters are based on slope (e.g., [

13,

14,

15,

16]), interpolation (e.g., [

17,

18,

19,

20]), morphology (e.g., [

21,

22,

23]), or segmentation (e.g., [

24,

25]). Other types of filters include, for example, the statistics-based filter [

26], cloth simulation filter [

27], a combination of cloth simulation filter with s progressive TIN densification [

28], or the MDSR filter based on iterative determination of the lowest terrain points taken from multiple perspectives [

29]). In principle, all these methods assume that the terrain is relatively level, and the slope (or change of slope) does not exceed certain maximum values. Based on these assumptions, an approximation of the terrain is created (triangular network, square grid, or cloth simulation) and points until a certain distance from it are considered terrain. However, these methods all come with some limitations, such as difficult distinguishing between rocks (ground) and buildings (non-ground).

Recently, however, the trends in new filtering methods have shifted towards the use of machine learning, which can easily be designed as multicriterial and, therefore, more universal. Here, however, a principal problem occurs – to be able to load an irregular point cloud (note that the points within the cloud are not in any regular grid or structure) into a neural network, it is necessary to transform the cloud into a regular structure.

Machine learning-based methods often employ assessment methods based on local features, i.e., characteristics calculated for each point of the cloud from its close vicinity, such as the variance in spheres of various diameters around the point [

30], colors of the points [

31], or other spatial and spectral features [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Researchers also often use approaches from image analysis, transposing the point cloud into 2D, processing it through standard image analysis methods such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs), and, subsequently, reversely transposing it to a 3D point cloud ([

36,

37]) from one or more perspectives ([

38,

39,

40,

41]). The PointNET [

42] architecture and its advanced version PointNet++ [

43] have brought about another concept for object recognition in the cloud; it is, however, applicable rather to spatially limited clouds and objects.

Voxelization is another possible approach [

44] that could be applied even to large clouds. It is based on the transformation of the irregular cloud into a regular structure; the choice of the voxel size is usually the crucial (and limiting) factor defining the resulting resolution.

As mentioned above, most algorithms have been developed for ALS data and are not entirely suitable for dense point clouds from rugged areas with overhanging rocks and rock faces. Hence, in this paper, we propose a novel method that would not depend on the mathematical definition of the surface or on local features from a small vicinity; rather, this method learns the character of the terrain on a data sample, enabling terrain identification also in other areas. The proposed method is based on the detection of the local cloud shape using a neural network (utilizing, therefore, a simple local feature). The input data for learning are voxelized and evaluated within a 9 x 9 x 9 voxel cube. As the Earth’s surface has an unrestricted character, the optimal voxel size (and voxel cube size) cannot be determined beforehand; it is, therefore, necessary to use multiple consequent voxel sizes in a way ensuring that points with the target attribute (such as terrain, rock face, etc.) are represented in each voxel cube. This method allows us to teach the neural network acceptable patterns of the object of interest with various shapes. We propose a novel method, discuss its pros and cons, and, lastly, evaluate the method's performance through its comparison using a standard and freely available Cloth simulation filter (CSF).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Method Principle

Figure 1 provides a 2D illustration of the basic principle of the method, showing the profile of a point cloud in a forested area. The point cloud is voxelized into voxels of suitable size (2x2x2m in

Figure 1), each voxel is characterized by its position in the grid and the number of points it contains. Voxels below the terrain contain no points (or very few points, e.g., noise). The evaluation of each individual voxel is performed on the basis of its surroundings (here, 9x9x9 voxels, i.e., the central voxel and four voxels in each principal direction), forming a voxel cube (VC) – the principal assessment unit in this algorithm. To avoid issues associated with differences in point cloud density (caused, e.g., by differences in the distance of the 3D scanner from the objects or height of the unmanned aerial vehicle, UAV, above the terrain), the number of points in each voxel is normalized (divided by the total number of points in the entire voxel cube). In this way, each voxel is represented by the percentage of points in the voxel cube. Subsequently, each individual voxel is classified as ground or non-ground by a neural network trained on a part of the investigated point cloud or on a point cloud from a similar area. The points in voxels classified as ground then enter a second pass with a reduced voxel size, providing a finer detail of the terrain. In this way, the voxel size (and detail of the terrain) gradually decreases until the required detail is achieved (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

The initial voxel size (m) and voxel cube size (n of voxels) need to be chosen in a way ensuring that the voxel cube contains a distinguishable part of the real terrain. For this reason, it is safer to initially select a larger voxel size. A bigger voxel cube size (in the sense of the greater number of included voxels) is capable of providing better terrain identification as it gives the neural network better information on the surroundings; at the same time, however, it increases the computational costs; hence, a compromise size of 9x9x9 voxels was used for the verification of this method and its performance. In our experience, the gradual reduction of voxel size should be to approx. 75 % of that in the previous step, which ensures correct detection even in highly rugged terrain.

The above-described process, however, has an inherent flaw. The red arrows in

Figure 3 indicate voxels that include only marginal numbers of terrain points, which will lead to their classification as non-ground. This can be, however, easily prevented by evaluating the point cloud in two voxel grids that are mutually shifted by half of the voxel size in each axis (we will refer to them as the “regular” and “shifted”). Next, all points from the cloud are classified as ground or non-ground based on whether or not they lie within a voxel classified as ground at least in one of the grids.

The classification of narrow tall (or deep) terrain features that could be lost during classification using large voxel size poses another possible problem. To rectify this, the algorithm was adjusted to keep (besides the points in voxels classified as ground) also one additional “envelope” layer of voxels for the next step. This envelope, therefore, helps prevent the undesirable removal of features such as narrow rocks that could be erroneously considered trees.

Figure 4 shows the gradual action of the filter in 3D, the classification scheme is visualized in

Figure 5.

2.2. Deep Neural Network and Its Training

As mentioned above, the classification itself was performed using a deep neural network (DNN). The inputs into the triangular DNN are the normalized numbers of points in individual voxels, i.e., 729 values (9

3) for each voxel cube. The first hidden layer has 1,458 neurons, subsequent hidden layers have 729, 364, 182, 91, 45, and 22 neurons, with one output neuron returning binary 0/1 values (1 – ground; 0 – non-ground). The network was created in Python version 3.11.9. Training and use of the neural network were performed using TensorFlow 2.17.0 libraries and Keras interface. In training, two types of regularization were used – the L2 layer regularization in all hidden layers and drop-out regularization, which has been inserted between each two subsequent hidden layers. The definition of the neural network, including regularization coefficients, is shown in

Appendix B. As the terrain shape for each voxel/voxel cube size slightly differs, separate training was performed for each step of the algorithm. To optimize the training process, we started the training from the manually classified data at the finest (required) resolution. As the individual steps of the algorithm use voxels of relatively similar size (75%), the patterns of voxel cubes can be rightly expected to be similar and the DNN training was, therefore, performed stepwise, always using the previous network as the initial state.

For training, data manually classified in CloudCompare v 2.13.0 were used. For each voxel size, the training data are voxelized accordingly and if the particular voxel contains at least one point representing terrain, the voxel is considered to be a ground-representing voxel. For training of each voxel size, the point cloud is cropped to a distance of max. 4 voxels from the nearest ground point (which corresponds to the actual classification process as described above). The training was performed with both regular and shifted grids. Moreover, to allow the best possible training of the general shapes, the DNN was trained also on data rotated by 90°, 180°, and 270°. To account for the differences in the numbers of ground and non-ground voxels in the training data, weights were assigned to the voxel classes to compensate for this.

2.3. Training/Testing Data

2.3.1. Data 1

Data 1 describes a steep slope with rocks. The point cloud was acquired photogrammetrically using the structure from motion (SfM) technique from a manually piloted flight with the UAV DJI Phantom 4. The data was processed in Agisoft Metashape ver. 2.0.1 without any filtering to determine as many terrain points as possible. Considering the very dense vegetation, the resolution was set to ultra-high. Both these settings led to the presence of a considerable amount of noise. No further editing was performed for the purposes of testing. The training data (area of 80x40x40 m;

Figure 6 (a) contains 34,859,808 points, the test data (54x32x47 m,

Figure 6 (b) consists of 17,278,032 points. In both cases, resolution is approx. 1 cm.

2.3.2. Data 2

Data 2 was acquired in a densely forested area with rugged terrain using a lidar system DJI mounted on a UAV DJI Matrice 300 RTK. For this paper, four discrete areas (see

Figure 7,

Table 1) were cut out from the scanned area of approx. 340 x 250 m – one was used as a training dataset, the remaining three as test datasets. The reason that we did not use the entire area lays in the very laborious manual preparation of the reference ground surface, the location of the individual data in the area is shown in

Figure A1. Data 2 – Boulders (

Figure 7(c),

Figure 7(d)) show a typical area of this site – relatively rugged terrain with large boulders and the predominance of higher vegetation. The Data 2 – Tower (

Figure 7(e),

Figure 7(f)) area contains built structures, which were not present in the training data. Data 2 – Rugged (

Figure 7(g),

Figure 7(h)) show the most challenging area as it is covered with lower dense vegetation (shrubs), which even lidar often fails to penetrate, and contains highly rugged terrain features.

2.4. Testing and Evaluation Procedure

Each used dataset was manually classified into two classes – ground and non-ground. One area on each site was used for the training of the DNN, the remaining ones for testing. The results of testing areas produced by DNNs were evaluated (i) visually to be able to assess the character of the potential classification errors and (ii) using standard accuracy characteristics, i.e., balanced accuracy (BA) and F-score (FS). These two characteristics were used as complementary as BA characterizes the average classification of all (in this case, two) classes considering their representation, while FS rather focuses on the success of classification of the element of interest (in our study, ground). Considering points classified as ground by the algorithm positives (P) and points classified as non-ground as negatives (N), the quality of classification is then expressed as true positive rate (% of all ground points in the cloud that were correctly identified) and true negative rate (% of all negatives in the cloud that were identified as negatives). For details, see the calculation formulas in

Table 2 [

45].

The voxel sizes for the MSVC method were selected according to the principles described above, with an initial voxel size of 6 m. The minimum (final) voxel size was chosen in accordance with the particular dataset – based on the noise level. It was set to 6 cm for Data 1, and to 11 cm for Data 2, respectively. The entire series of steps in meters was 6.00, 4.50, 3.38, 2.53, 1.90, 1.42, 1.07, 0.80, 0.60, 0.45, 0.34, 0.25, 0.19, 0.14, 0.11, 0.08, and 0.06 m.

To compare the classification success with an established method, we used a freely available Cloth Simulation Filter (CSF) implemented as a plugin in CloudCompare ver. 2.13.0. This filter was selected for comparison because it performed best on rocky terrain in our previous paper in which we tested several widely used freely available filters (CSF, SMRF, PMF) [

30]. As there is no universal setting of the CSF, multiple settings were tested for each of the test areas and the best result was always used. Namely, the CSF parameters were set as follows: Scene processing – yes; Scene – Steep slope; Cloth resolution – 0.025; 0.5; 0.1 m and threshold of 0.15; 0.20; and 0.25 m.

3. Results

3.1. Data 1 – Rocks

The results of the principal evaluation, i.e., the TPR, TNR, BA, and FS characteristics, are detailed in

Table 3. The MSVC outcome is presented not only for the final (minimal) voxel size, but for the purpose of illustration of the process also for the four previous steps (0.08 – 0.19 m).

While the true positive rate (TPR), i.e., the success rate of identification of ground points, of the CSF was approximately 89%, MSVC reached an excellent TPR of 99.94%, i.e., it classified almost all ground points within the cloud as ground. The TNR (True negative rate, i.e., the success rate of identification of non-ground points) in both methods is approx. 76 %. This is caused by the relatively high density of the non-ground points (low vegetation) in the immediate vicinity of the terrain; hence, neither CSF nor MSVC can fully remove them (due to the CSF threshold and MSVC voxel size). BA of the MSVC method is 88.3% and the FS is 98.3%. This indicates that the ground point classification success is high and the method preserves the necessary points. The CSF results are clearly inferior (BA 82.4%, FS 92.6%), as can be seen in

Figure 8 (a) and in the detail in

Figure 8 (c).

CSF filter, similar to others tested, e.g., in [

29,

30] is not ready for this type of terrain. MSVC, however, learns the available terrain shapes, which leads to excellent terrain classification. In the top right corner of the detail in

Figure 8 (d), a lower part of a tree (bush) that was misclassified by both algorithms is clearly visible. However, this is a very difficult detail to distinguish from the ground – the vegetation was enclosed in a thin crevice; to be fair to the MSVC, we should note that no such feature was present in the training data for the MSVC filter. In a way, therefore, we cannot consider this to be a failure of the MSVC algorithm, as it “saw” no example of this in the training data; had the training data included such an area, the result would likely be even better.

3.2. Data 2

Due to the use of multiple locations within the Data 2 point cloud, only the best achieved results are presented in

Table 4 (complete results are shown in the

Appendix C,

Table A1,

Table A2,

Table A3). It should be, however, pointed out that many of the accuracy parameters were very close for multiple settings so it was difficult to pick a single setting in some instances.

In all cases, both BA and FS parameters are better for MSVC than for CSF, although the difference is very low and both methods provide good success. However, the differences are more apparent in data visualizations, see

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12. These figures also obviate that MSVC preserves more points in the rugged areas than CSF, thus better “recognizing” terrain shape. The unfiltered vegetation is low (i.e., very close to the terrain) and is approximately the same in both filtering approaches (

Figure 10 (a) and (b)). Unlike in Data 1, this dataset contains also terrain features that were not present in the training data (compare, e.g.,

Figure 7(c), 7(e), 10, and 11 to

Figure 7(a), which shows training data, and

Figure 9 showing the buildings in the Tower area). Despite this lack of training data, the MSVC algorithm dealt very well with such areas, better than CSF (the data is more complete).

Data 2 – Boulder (

Figure 10) shows a similar rate of misclassification of low vegetation for ground for both algorithms (compare

Figure 10(b) to 10(a)). However, as seen in

Figure 10 (d), MSVC was more successful in identifying ground points in problematic areas than CSF.

Figure 11 shows results from the Data 2 – Tower area. Both filters suffer from noise more than in Data 2 – Boulder (a, b); more importantly, however, CSF incorrectly classified the roof of the building as ground (a) while MSVC correctly recognized it as a non-ground object despite having no training data on built-up areas. The (c) and (d) panels show a similar effect as in the previous case – the MSVC-generated terrain is more complete (with the exception of the precipice just below the building, which was not correctly recognized as terrain by MSVC).

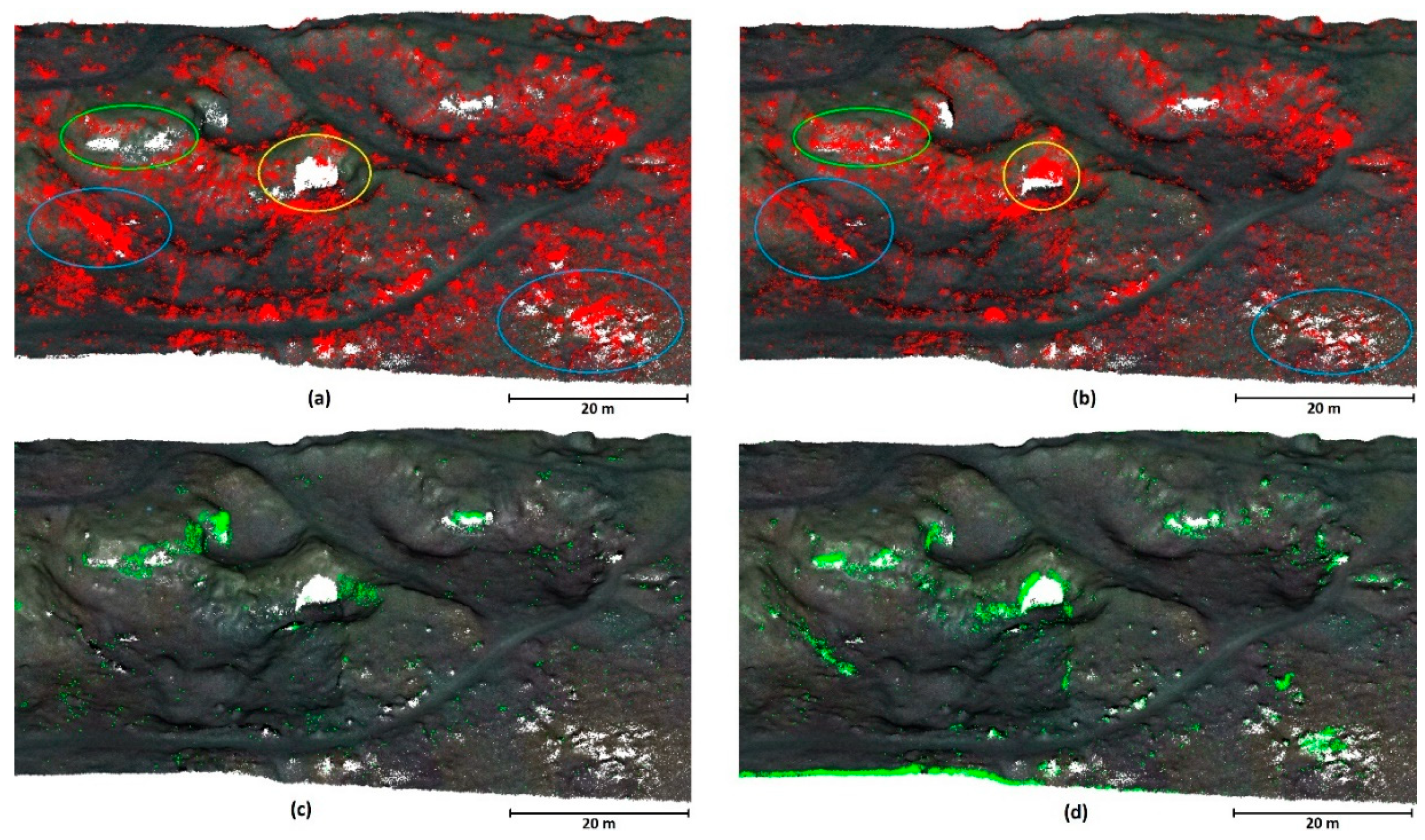

The results of Data 2 – Rugged classification (

Figure 12) show a clear difference between the performance of both filters in the area with dense shrubs (a) and (b), where in such areas, CSF misclassifies low vegetation as terrain more often than the MSVC filter (blue ovals). On the other hand, the yellow oval shows an area of low vegetation with the same shape as the terrain underneath that was incorrectly classified as terrain by MSVC (a), (b). Lastly, the green oval shows an area where MSVC identified significantly more terrain points (see

Figure 12(d)), it was, however, at the cost of preserving some points belonging to low vegetation.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we have developed and evaluated a novel ground filter based on a combination of point cloud voxelization and deep neural network. The principle of the method lies in the gradual reduction of the voxel size, which gradually, step by step, refines the terrain.

A vast majority of currently used filters are constructed for airborne laser scanning data, where they serve relatively well – it is, however, necessary to point out that applications utilizing ALS data typically need a resolution of just several points per square meter. However, where dense clouds based on UAV data acquisition (be it SfM-based or UAV-borne lidar clouds) are concerned, these filters may fail to provide satisfactory results, particularly in rugged terrain ([

30]). Such dense clouds are often used in engineering applications (such as in quarries ([

46,

47] or in rocky terrain where landslides and overhanging or collapsing rocks may pose a danger to human constructions or lives [

48]).

It should be emphasized that we used data extremely difficult for ground filtering to assess the performance of both algorithms. In ordinary practice, the terrain features that are concentrated in our testing areas represent only a small fraction of the clouds, which leads to excellent overall results even when using any other filter. In other words, if such a difficult terrain as shown in our datasets normally represents a very small proportion of the landscape and the rest is correctly classified by any filter, the error caused by the incorrect classification of these features causes only a negligible overall error.

Although both CSF and MSVC filters performed well in identifying terrain points, the MSVC filter consistently outperformed the widely used CSF filter, especially in the most rugged and problematic areas, such as the rock face in Data 1 (best balanced accuracies of 88.3 % vs 82.4 % and F-scores of 98.3 vs 92.6 % for MSVC and CSF, respectively). As obvious from the true positive rates (which were as high as 99.9 % for MSVC and 89.2 % for CSF, respectively), MSVC correctly detects almost all terrain points, which was not at the cost of decreasing the true negative rate (76.6 % and 75.7 % for MSVC and CSF, respectively); contrary, MSVC performs slightly better even in this parameter. Where Data 2 is concerned, MSVC still outperforms CSF, although the difference is not as high. This is given by the fact that the Data 2 point cloud is more “standard” and contains fewer highly problematic spots. The biggest difference between the two algorithms lies in the better preservation of terrain points by MSVC even in the challenging spots (see the points highlighted in green in

Figure 10 (d),

Figure 11 (d), and

Figure 12 (d). In addition, MSVC is less prone to identifying low vegetation as ground (look at the blue ovals in Figure 13–14).

We were surprised by the fact that unlike CSF, the MSVC algorithm managed to successfully remove the buildings in Data 2 – tower, although no such construction was present in the training data. This suggests that the neural network was capable of a certain abstraction, distinguishing between the true terrain and the roof. The likely explanation is that rather than recognizing the roof and the wall as such (which the algorithm has no way of knowing), it only recognized that these structures do not represent the ground as it did not correspond to any terrain feature it “saw” in the training data. This finding makes the algorithm even more promising as it appears that the filter needs to train only on the character of the ground and the knowledge of the exact vegetation type (or other obstacles) might be less important for its correct function. In effect, this opens the door to the possible more universal applicability of the algorithm – if the algorithm is pre-trained to several terrain types, it might be able to correctly identify terrain even without the need of creating reference data for the particular area; rather, selecting just the terrain type (e.g. flat terrain, rocks, urban, etc.) previously trained could be sufficient. This, however, needs to be verified by future research.

The MSVC algorithm brings multiple benefits to the ground filtering of dense point clouds. It does not need any computationally demanding mathematical operations, the algorithm makes its decisions always solely based on the number of points in individual voxels and its surroundings. Last but not least, the algorithm is inherently robust against the presence of outliers and noise. On the other hand, it is not possible to achieve terrain containing only a single layer of ground points due to the cubic character of the voxel, which always contains remnants of low vegetation. This is, however, true for almost any filter as most of them operate with a parameter such as offset or threshold that characterizes the allowed distance of ground points from the approximated terrain surface.

It is very difficult to compare our results to the existing literature as this is a novel filter that has been never employed before. Moreover, few studies only investigate ground filtering on such dense clouds characterizing highly rugged terrain at resolutions comparable to our study (resulting terrain resolution of approx. 1 to 5 cm).

There is ample space for future research on the use of this algorithm besides the above-mentioned construction of neural network that would be universally trained to detect a particular terrain type (which could simplify the use of this algorithm). The simplest direction of future research is increasing the number of voxels in the voxel cube, which could allow faster operation (need fewer steps). At present, this algorithm only uses a single characteristic – the number of points in the voxel; this could be built upon by the addition of other characteristics, such as the spatial variance. Another possible improvement could lie in training – in the present paper, we have trained the filter on terrain rotated in steps of 90 degrees. Reduction of the rotation step could also lead to improvement of training and, thus, to a better terrain detection performance.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed a novel ground filtering method utilizing the multi-size voxel cube (MSVC) approach combined with deep neural network. We demonstrated its effectiveness in an extremely difficult (rugged) terrain with dense vegetation. Compared to traditional filters, such as CSF, the MSVC method identified terrain points more accurately thanks to the learning feature of the neural network. The results demonstrate that the MSVC filter can be successfully used for digital terrain extraction from dense clouds even in highly demanding environments where other filters fail, such as steep slopes and/or rugged densely vegetated areas. In the present study, we used a part of the study area for learning, necessitating the manual creation of reference terrain, which can be considered a disadvantage of this algorithm; in the future, however, we aim to produce more generally valid neural networks trained for individual types of landscape (such as rocky mountains, urban environment, hills, etc.), which would make the use of this algorithm much more user-friendly.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Š.; methodology, M.Š.; software, M.Š.; validation, R.U., M.B., J.K. and H.V.; formal analysis, R.U.; investigation M.B., J.K. and H.V.; resources, M.Š.; data curation, R.U.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Š.; writing—review and editing, R.U., M.B., J.K. and H.V.; visualization, M.Š.; supervision, M.Š.; project administration, R.U.; funding acquisition, R.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Technology Agency of the Czech Republic—grant number CK03000168, “Intelligent methods of digital data acquisition and analysis for bridge inspections” and by the grant agency of CTU in Prague – grant number SGS24/048/OHK1/1T/11 “Data filtering and classification using machine learning methods”.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the size of the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Data 2 – location of individual data in the area (a) Data 2 Training (b) Data 2 Boulders (c) Data 2 Tower (d) Data 2 Rugged.

Figure A1.

Data 2 – location of individual data in the area (a) Data 2 Training (b) Data 2 Boulders (c) Data 2 Tower (d) Data 2 Rugged.

Appendix B. Definition a Neural Network in Python Using the Tensorflow Library

import numpy

import tensorflow as tf

import keras

from keras import regularizers

kernel = 9;

k3 = numpy.power(kernel,3)

n1 = int(2*k3)

add_layers_number = 7 # number of hidden layers

regu = 0.001 # coefficient L2 regularization

drop = 0.25 # drop rate 25%

def CreateNetModel_T2(add_layers_number, n1, k3, regu, drop):

model = keras.Sequential()

model.add(keras.Input(shape=(k3,)))

for i in range(add_layers_number):

model.add(keras.layers.Dense(int(n1/np.power(2,i)),

activation='relu',

kernel_regularizer=regularizers.L2(regu)))

model.add(keras.layers.Dropout(drop))

model.add(keras.layers.Dense(1, activation='sigmoid'))

model.compile(loss='binary_crossentropy', optimizer='adam',

metrics=['accuracy'])

return model

Appendix C. Complete Classification Results for Data 2

Table A1.

Classification success rate – Data 2 Boulders.

Table A1.

Classification success rate – Data 2 Boulders.

| Method |

Cloth resolution/ voxel size [m] |

Threshold [m] |

TPR [%] |

TNR [%] |

BA [%] |

FS [%] |

| CSF |

0.025 |

0.250 |

99.35 |

99.57 |

99.46 |

99.32 |

| |

0.050 |

|

99.00 |

99.67 |

99.34 |

99.23 |

| |

0.100 |

|

97.97 |

99.75 |

98.86 |

98.77 |

| |

0.250 |

|

90.23 |

99.81 |

95.02 |

94.71 |

| |

0.025 |

0.200 |

98.85 |

99.64 |

99.24 |

99.13 |

| |

0.050 |

|

98.13 |

99.77 |

98.95 |

98.87 |

| |

0.100 |

|

96.66 |

99.85 |

98.26 |

98.18 |

| |

0.250 |

|

86.90 |

99.88 |

93.39 |

92.90 |

| |

0.025 |

0.150 |

97.45 |

99.71 |

98.58 |

98.47 |

| |

0.050 |

|

95.71 |

99.85 |

97.78 |

97.68 |

| |

0.100 |

|

93.25 |

99.92 |

96.58 |

96.44 |

| |

0.250 |

|

80.93 |

99.93 |

90.43 |

89.41 |

| MSVC |

0.110 |

- |

99.30 |

99.79 |

99.54 |

99.47 |

| |

0.140 |

|

99.67 |

99.69 |

99.68 |

99.58 |

| |

0.190 |

|

99.88 |

99.57 |

99.72 |

99.59 |

| |

0.250 |

|

100.00 |

99.16 |

99.58 |

99.32 |

Table A2.

Classification success rate – Data 2 Tower.

Table A2.

Classification success rate – Data 2 Tower.

| Method |

Cloth resolution/ voxel size [m] |

Threshold [m] |

TPR [%] |

TNR [%] |

BA [%] |

FS [%] |

| CSF |

0.025 |

0.250 |

99.52 |

97.11 |

98.32 |

96.97 |

| |

0.050 |

|

99.29 |

97.41 |

98.35 |

97.14 |

| |

0.100 |

|

98.61 |

97.56 |

98.08 |

96.93 |

| |

0.250 |

|

94.33 |

98.07 |

96.20 |

95.20 |

| |

0.025 |

0.200 |

99.33 |

97.37 |

98.35 |

97.12 |

| |

0.050 |

|

99.00 |

97.79 |

98.39 |

97.35 |

| |

0.100 |

|

98.09 |

97.97 |

98.03 |

97.06 |

| |

0.250 |

|

92.51 |

98.46 |

95.49 |

94.61 |

| |

0.025 |

0.150 |

98.60 |

97.92 |

98.26 |

97.27 |

| |

0.050 |

|

97.93 |

98.57 |

98.25 |

97.56 |

| |

0.100 |

|

96.41 |

98.78 |

97.59 |

96.98 |

| |

0.250 |

|

88.61 |

99.12 |

93.86 |

93.10 |

| MSVC |

0.110 |

- |

99.78 |

98.00 |

98.89 |

97.95 |

| |

0.140 |

|

99.79 |

97.75 |

98.77 |

97.71 |

| |

0.190 |

|

99.80 |

97.57 |

98.69 |

97.55 |

| |

0.250 |

|

99.81 |

97.43 |

98.62 |

97.42 |

Table A3.

Classification success rate – Data 2 Rugged.

Table A3.

Classification success rate – Data 2 Rugged.

| Method |

Cloth resolution/ voxel size [m] |

Threshold [m] |

TPR [%] |

TNR [%] |

BA [%] |

FS [%] |

| CSF |

0.025 |

0.250 |

99.19 |

97.56 |

98.37 |

97.78 |

| |

0.050 |

|

98.51 |

98.16 |

98.33 |

97.88 |

| |

0.100 |

|

98.17 |

98.60 |

98.38 |

98.03 |

| |

0.250 |

|

93.77 |

98.96 |

96.37 |

96.01 |

| |

0.025 |

0.200 |

99.33 |

98.52 |

97.85 |

98.18 |

| |

0.050 |

|

99.00 |

97.33 |

98.56 |

97.95 |

| |

0.100 |

|

98.09 |

96.38 |

99.03 |

97.70 |

| |

0.250 |

|

92.51 |

90.66 |

99.31 |

94.98 |

| |

0.025 |

0.150 |

96.76 |

98.18 |

97.47 |

97.00 |

| |

0.050 |

|

94.23 |

98.93 |

96.58 |

96.23 |

| |

0.100 |

|

91.96 |

99.37 |

95.66 |

95.34 |

| |

0.250 |

|

84.48 |

99.58 |

92.03 |

91.27 |

| MSVC |

0.110 |

- |

99.20 |

98.82 |

99.01 |

98.71 |

| |

0.140 |

|

99.64 |

98.46 |

99.05 |

98.67 |

| |

0.190 |

|

99.81 |

98.06 |

98.94 |

98.47 |

| |

0.250 |

|

99.87 |

97.66 |

98.76 |

98.19 |

References

- Ciou, T.-S.; Lin, C.-H.; Wang, C.-K. Airborne LiDAR Point Cloud Classification Using Ensemble Learning for DEM Generation. Sensors 2024, 24, 6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegner, K.; Durand, V.; Villeneuve, N.; Mangeney, A.; Kowalski, P.; Peltier, A.; Stark, M.; Becht, M.; Haas, F. Multitemporal Quantification of the Geomorphodynamics on a Slope within the Cratére Dolomieu—At the Piton de La Fournaise (La Réunion, Indian Ocean) Using Terrestrial LiDAR Data, Terrestrial Photographs, and Webcam Data. Geosciences 2024, 14, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, T.; Menoscal, M.; Bravo, G.; Rosado, V.; Vaca, V.; Capa, D.; Mulas, M.; Jordá-Bordehore, L. Rock Slope Stability Analysis Using Terrestrial Photogrammetry and Virtual Reality on Ignimbritic Deposits. Journal of Imaging 2024, 10, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treccani, D.; Adami, A.; Brunelli, V.; Fregonese, L. Mobile Mapping System for Historic Built Heritage and GIS Integration: A Challenging Case Study. Applied Geomatics 2024, 16, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marčiš, M.; Fraštia, M.; Lieskovský, T.; Ambroz, M.; Mikula, K. Photogrammetric Measurement of Grassland Fire Spread: Techniques and Challenges with Low-Cost Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Drones 2024, 8, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štroner, M.; Urban, R.; Křemen, T.; Braun, J. UAV DTM Acquisition in a Forested Area – Comparison of Low-Cost Photogrammetry (DJI Zenmuse P1) and LiDAR Solutions (DJI Zenmuse L1). European Journal of Remote Sensing 2023, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, F.; Teruggi, S.; Achille, C.; Vassena, G.P.M.; Fassi, F. Integrated Laser Scanner Techniques to Produce High-Resolution DTM of Vegetated Territory. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štroner, M.; Urban, R.; Křemen, T.; Braun, J.; Michal, O.; Jiřikovský, T. Scanning the Underground: Comparison of the Accuracies of SLAM and Static Laser Scanners in a Mine Tunnel. Measurement 2024, 115875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavelka, K.; Běloch, L.; Pavelka, K. MODERN METHODS OF DOCUMENTATION AND VISUALIZATION OF HISTORICAL MINES IN THE UNESCO MINING REGION IN THE ORE MOUNTAINS. ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2023, X-M-1–2023, 237–244. [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Currit, N.; Zhao, K. Ground Filtering Algorithms for Airborne LiDAR Data: A Review of Critical Issues. Remote Sensing 2010, 2, 833–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, N.; Tan, W.; Guan, H.; Wang, L.; Ma, L.; Tao, P.; Fatholahi, S.; Hu, X.; Li, J. Towards Intelligent Ground Filtering of Large-Scale Topographic Point Clouds: A Comprehensive Survey. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation 2023, 125, 103566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Guo, J.; Wu, H.; Li, Y.; Shi, B. Performance Comparison of Filtering Algorithms for High-Density Airborne LiDAR Point Clouds over Complex LandScapes. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosselman, G. Slope based filtering of laser altimetry data. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2000, 33, 935–942. [Google Scholar]

- Sithole, G. Filtering of laser altimetry data using a slope adaptive filter. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2001, 34, 203–210. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Wang, L.; Silván-Cárdenas, J.L.; Currit, N. A Multi-Directional Ground Filtering Algorithm for Airborne LIDAR. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2008, 64, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susaki, J. Adaptive Slope Filtering of Airborne LiDAR Data in Urban Areas for Digital Terrain Model (DTM) Generation. Remote Sensing 2012, 4, 1804–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, K.; Pfeifer, N. Determination of Terrain Models in Wooded Areas with Airborne Laser Scanner Data. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 1998, 53, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, P. DEM generation from laser scanner data using adaptive TIN models. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2000, 33, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kobler, A.; Pfeifer, N.; Ogrinc, P.; Todorovski, L.; Oštir, K.; Džeroski, S. Repetitive Interpolation: A Robust Algorithm for DTM Generation from Aerial Laser Scanner Data in Forested Terrain. Remote Sensing of Environment 2006, 108, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Xiang, M.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, J. An Improved Adaptive Grid-Based Progressive Triangulated Irregular Network Densification Algorithm for Filtering Airborne LiDAR Data. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Chen, S.-C.; Whitman, D.; Shyu, M.-L.; Yan, J.; Zhang, C. A Progressive Morphological Filter for Removing Nonground Measurements from Airborne LIDAR Data. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2003, 41, 872–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingel, T.J.; Clarke, K.C.; McBride, W.A. An Improved Simple Morphological Filter for the Terrain Classification of Airborne LIDAR Data. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2013, 77, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. FILTERING AIRBORNE LIDAR DATA BY AN IMPROVED MORPHOLOGICAL METHOD BASED ON MULTI-GRADIENT ANALYSIS. ˜the œInternational Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences/International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2013, XL-1/W1, 191–194. [CrossRef]

- Im, J.; Jensen, J.R.; Hodgson, M.E. Object-Based Land Cover Classification Using High-Posting-Density LiDAR Data. GIScience & Remote Sensing 2008, 45, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosselman, G.; Coenen, M.; Rottensteiner, F. Contextual Segment-Based Classification of Airborne Laser Scanner Data. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2017, 128, 354–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosilla, F.; Macorig, D.; Scaioni, M.; Sebastianutti, I.; Visintini, D. LiDAR Data Filtering and Classification by Skewness and Kurtosis Iterative Analysis of Multiple Point Cloud Data Categories. Applied Geomatics 2013, 5, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Qi, J.; Wan, P.; Wang, H.; Xie, D.; Wang, X.; Yan, G. An Easy-to-Use Airborne LiDAR Data Filtering Method Based on Cloth Simulation. Remote Sensing 2016, 8, 501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Zhang, W.; Liang, X.; Wan, P.; Qi, J.; Yu, S.; Yan, G.; Shao, J. Filtering Airborne LiDAR Data Through Complementary Cloth Simulation and Progressive TIN Densification Filters. Remote Sensing 2019, 11, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štroner, M.; Urban, R.; Línková, L. Multidirectional Shift Rasterization (MDSR) Algorithm for Effective Identification of Ground in Dense Point Clouds. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 4916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štroner, M.; Urban, R.; Lidmila, M.; Kolář, V.; Křemen, T. Vegetation Filtering of a Steep Rugged Terrain: The Performance of Standard Algorithms and a Newly Proposed Workflow on an Example of a Railway Ledge. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štroner, M.; Urban, R.; Línková, L. Color-Based Point Cloud Classification Using a Novel Gaussian Mixed Modeling-Based Approach versus a Deep Neural Network. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Liu, S.; Tan, K.; Yin, M.; Tao, P. ANN-Based Filtering of Drone LiDAR in Coastal Salt Marshes Using Spatial–Spectral Features. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurunnabi, A.; Teferle, F.N.; Li, J.; Lindenbergh, R.C.; Hunegnaw, A. AN EFFICIENT DEEP LEARNING APPROACH FOR GROUND POINT FILTERING IN AERIAL LASER SCANNING POINT CLOUDS. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences/International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2021, XLIII-B1-2021, 31–38. [CrossRef]

- Ciou, T.-S.; Lin, C.-H.; Wang, C.-K. Airborne LiDAR Point Cloud Classification Using Ensemble Learning for DEM Generation. Sensors 2024, 24, 6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, L.; Zhong, R.; Chen, D.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, S. Hierarchical Aggregated Deep Features for ALS Point Cloud Classification. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2020, 59, 1686–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Jiang, W.; Xu, B.; Zhu, Q.; Jiang, S.; Huang, W. A Convolutional Neural Network-Based 3D Semantic Labeling Method for ALS Point Clouds. Remote Sensing 2017, 9, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizaldy, A.; Persello, C.; Gevaert, C.; Elberink, S.O.; Vosselman, G. Ground and Multi-Class Classification of Airborne Laser Scanner Point Clouds Using Fully Convolutional Networks. Remote Sensing 2018, 10, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, C.; Zhao, Z.; Miao, J.; Tian, P. ALS Point Cloud Classification by Integrating an Improved Fully Convolutional Network into Transfer Learning with Multi-Scale and Multi-View Deep Features. Sensors 2020, 20, 6969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Hu, X.; Shu, Z.; Qin, N.; Zhang, J. Deep Ground Filtering of Large-Scale ALS Point Clouds via Iterative Sequential Ground Prediction. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Hu, X.; Zhang, J.; Shu, Z.; Xu, J.; Du, J. Large-Scale ALS Point Clouds Segmentation via Projection-Based Context Embedding. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2024, 62, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, H.; Song, D. A Filtering Method for LiDAR Point Cloud Based on Multi-Scale CNN with Attention Mechanism. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.R.; Su, H.; Mo, K.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet: Deep Learning on Point Sets for 3D Classification and Segmentation. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision, Stanford, CA, USA, 25–28 October 2016; pp. 601–610. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.R.; Yi, L.; Su, H.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet++: Deep Hierarchical Feature Learning on Point Sets in a Metric Space. In Proceedings of the 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing System (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Xu, Y.; Li, Y. Aerial Lidar Point Cloud Voxelization with Its 3D Ground Filtering Application. Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing 2017, 83, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, S.-H.; Jang, E.J.; Kim, M.-S.; Lee, M.-T.; Kang, Y.-J.; Lee, J.-E.; Eom, J.-H.; Jung, S.-Y. Change Point Analysis for Detecting Vaccine Safety Signals. Vaccines 2021, 9, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovanič, Ľ.; Peťovský, P.; Topitzer, B.; Blišťan, P. Spatial Analysis of Point Clouds Obtained by SfM Photogrammetry and the TLS Method—Study in Quarry Environment. Land 2024, 13, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, J.; Braunová, H.; Suk, T.; Michal, O.; Peťovský, P.; Kuric, I. Structural and Geometrical Vegetation Filtering - Case Study on Mining Area Point Cloud Acquired by UAV Lidar. Acta Montanistica Slovaca 2022, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovanič, Ľ.; Štroner, M.; Urban, R.; Blišťan, P. Methodology and Results of Staged UAS Photogrammetric Rockslide Monitoring in the Alpine Terrain in High Tatras, Slovakia, after the Hydrological Event in 2022. Land 2023, 12, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

A 2D illustration of the point cloud (profile) and its voxelization to 2x2x2 m voxels. Individual dots represent the centers of the voxels, color-coded to represent the number of points in the voxel (see the color bar). The central red square indicates the evaluated voxel, the large orange square the entire area used for its evaluation (2D representation of the voxel cube).

Figure 1.

A 2D illustration of the point cloud (profile) and its voxelization to 2x2x2 m voxels. Individual dots represent the centers of the voxels, color-coded to represent the number of points in the voxel (see the color bar). The central red square indicates the evaluated voxel, the large orange square the entire area used for its evaluation (2D representation of the voxel cube).

Figure 2.

A 2D illustration of the progressive reduction of vegetation with gradual reduction of the voxel size (color-coding indicates the number of points in the voxel relative to the most populated voxel; grey indicates voxels with no points; the greyed-out part of the cloud indicates the points removed in previous steps). (a) – voxel size approx. 3 m; (b) voxel size approx. 2 m; (c) voxel size approx. 1.5 m; (d) voxel size approx. 0.6 m.

Figure 2.

A 2D illustration of the progressive reduction of vegetation with gradual reduction of the voxel size (color-coding indicates the number of points in the voxel relative to the most populated voxel; grey indicates voxels with no points; the greyed-out part of the cloud indicates the points removed in previous steps). (a) – voxel size approx. 3 m; (b) voxel size approx. 2 m; (c) voxel size approx. 1.5 m; (d) voxel size approx. 0.6 m.

Figure 3.

(a) Misclassification of voxels with low numbers of points as non-ground and (b) the solution of this problem through the use of the additional shifted grid (blue lines); voxels classified as ground in any of the grids (thick lines) are considered ground and carried forward to the next step.

Figure 3.

(a) Misclassification of voxels with low numbers of points as non-ground and (b) the solution of this problem through the use of the additional shifted grid (blue lines); voxels classified as ground in any of the grids (thick lines) are considered ground and carried forward to the next step.

Figure 4.

Gradual filtering with stepwise reduction of the voxel size: (a) original cloud; (b) Step 2 (voxel size 4.5 m); (c) Step 5 (voxel size 1.9 m); (d) Step 15 - final result (voxel size 0.11 m).

Figure 4.

Gradual filtering with stepwise reduction of the voxel size: (a) original cloud; (b) Step 2 (voxel size 4.5 m); (c) Step 5 (voxel size 1.9 m); (d) Step 15 - final result (voxel size 0.11 m).

Figure 5.

Flowchart of the multi-size voxel cube (MSVC) algorithm.

Figure 5.

Flowchart of the multi-size voxel cube (MSVC) algorithm.

Figure 6.

Data 1 with vegetation color-coded according to the vegetation height: a) Training data, b) Test data; note that the training data contain all types of terrain as well as vegetation character present in the test data.

Figure 6.

Data 1 with vegetation color-coded according to the vegetation height: a) Training data, b) Test data; note that the training data contain all types of terrain as well as vegetation character present in the test data.

Figure 7.

Data 2 – training area (a, b) and testing areas Boulders (c-d), Tower (e-f), and Rugged (g-h).

Figure 7.

Data 2 – training area (a, b) and testing areas Boulders (c-d), Tower (e-f), and Rugged (g-h).

Figure 8.

Data 1 – best classification results: (a) CSF (cloth resolution 2.5cm; threshold 25cm); (b) MSVC (voxel size 6 cm); (c) detail of CSF classification; (d) detail of the same area classified by MSVC; the color-coded points indicate erroneously preserved vegetation, along with its height.

Figure 8.

Data 1 – best classification results: (a) CSF (cloth resolution 2.5cm; threshold 25cm); (b) MSVC (voxel size 6 cm); (c) detail of CSF classification; (d) detail of the same area classified by MSVC; the color-coded points indicate erroneously preserved vegetation, along with its height.

Figure 9.

The terrain model of the Data 2 – Tower area with buildings shown; note that no buildings were present in the training data.

Figure 9.

The terrain model of the Data 2 – Tower area with buildings shown; note that no buildings were present in the training data.

Figure 10.

Classification success for Data 2 – Boulder: (a) CSF classification and (b) MSVC classification, with points erroneously classified as ground highlighted in red; (c) CSF classification with points correctly identified by CSF but not by MSVC highlighted in green (d) MSVC classification with points correctly identified by MSVC but not by CSF highlighted in green.

Figure 10.

Classification success for Data 2 – Boulder: (a) CSF classification and (b) MSVC classification, with points erroneously classified as ground highlighted in red; (c) CSF classification with points correctly identified by CSF but not by MSVC highlighted in green (d) MSVC classification with points correctly identified by MSVC but not by CSF highlighted in green.

Figure 11.

Classification success for Data 2 – Tower: (a) CSF classification and (b) MSVC classification, with points erroneously classified as ground highlighted in red; (c) CSF classification with points correctly identified by CSF but not by MSVC highlighted in green (d) MSVC classification with points correctly identified by MSVC but not by CSF highlighted in green. Blue ovals indicate areas with the biggest differences in the performance of the filters, where CSF identified more points falsely as ground.

Figure 11.

Classification success for Data 2 – Tower: (a) CSF classification and (b) MSVC classification, with points erroneously classified as ground highlighted in red; (c) CSF classification with points correctly identified by CSF but not by MSVC highlighted in green (d) MSVC classification with points correctly identified by MSVC but not by CSF highlighted in green. Blue ovals indicate areas with the biggest differences in the performance of the filters, where CSF identified more points falsely as ground.

Figure 12.

Classification success for Data 2 – Rugged: (a) CSF classification and (b) MSVC classification, with points erroneously classified as ground highlighted in red; (c) CSF classification with points correctly identified by CSF but not by MSVC highlighted in green (d) MSVC classification with points correctly identified by MSVC but not by CSF highlighted in green. Colored ovals indicate areas with the biggest differences in the performance of the filters.

Figure 12.

Classification success for Data 2 – Rugged: (a) CSF classification and (b) MSVC classification, with points erroneously classified as ground highlighted in red; (c) CSF classification with points correctly identified by CSF but not by MSVC highlighted in green (d) MSVC classification with points correctly identified by MSVC but not by CSF highlighted in green. Colored ovals indicate areas with the biggest differences in the performance of the filters.

Table 1.

Data 2 – Dimensions and numbers of points of the training and test areas.

Table 1.

Data 2 – Dimensions and numbers of points of the training and test areas.

| Area |

Dimensions [m] |

Number of points |

Mean resolution [m] |

| Data 2 Training |

74x65x38 |

11,454,057 |

0.04 |

| Data 2 Boulders |

50x42x22 |

3,726,774 |

0.05 |

| Data 2 Tower |

85x72x26 |

20,941,671 |

0.03 |

| Data 2 Rugged |

100x53x27 |

7,569,811 |

0.05 |

Table 2.

Overview of success rate characteristics used (TP = true positives; FP = false positives; TN = true negatives; FN = false negatives).

Table 2.

Overview of success rate characteristics used (TP = true positives; FP = false positives; TN = true negatives; FN = false negatives).

| Characteristics |

Abbreviation |

Calculation |

| True positive rate |

TPR |

TPR = TP/(TP + FN) |

| True negative rate |

TNR |

TNR = TN/(TN + FP) |

| Balanced accuracy |

BA |

BA = (TPR + TNR)/2 |

| F-score |

FS |

FS = 2TP/(2TP + FP + FN) |

Table 3.

Data 1 - classification success (TPR = True positive rate, TNR = True negative rate, BA = Balanced accuracy, FS = F-Score).

Table 3.

Data 1 - classification success (TPR = True positive rate, TNR = True negative rate, BA = Balanced accuracy, FS = F-Score).

| Method |

Cloth resolution/ voxel size [m] |

Threshold [m] |

TPR [%] |

TNR [%] |

BA [%] |

FS [%] |

| CSF |

0.025 |

0.25 |

89.18 |

75.66 |

82.42 |

92.57 |

| 0.050 |

|

87.88 |

77.04 |

82.46 |

91.93 |

| 0.100 |

|

86.20 |

78.08 |

82.14 |

91.05 |

| 0.025 |

0.20 |

87.66 |

78.16 |

82.91 |

91.89 |

| 0.050 |

|

86.17 |

79.75 |

82.96 |

91.15 |

| 0.100 |

|

84.07 |

80.97 |

82.52 |

90.01 |

| 0.025 |

0.15 |

85.33 |

81.51 |

83.42 |

90.78 |

| 0.050 |

|

83.53 |

83.35 |

83.44 |

89.86 |

| 0.100 |

|

80.70 |

84.79 |

82.75 |

88.25 |

| MSVC |

0.060 |

- |

99.94 |

76.61 |

88.28 |

98.32 |

| 0.080 |

|

99.94 |

74.91 |

87.43 |

98.20 |

| 0.110 |

|

99.97 |

72.31 |

86.14 |

98.03 |

| 0.140 |

|

99.97 |

70.43 |

85.20 |

97.90 |

| 0.190 |

|

99.98 |

68.40 |

84.19 |

97.77 |

Table 4.

Classification success characteristics for the best results of both methods in Data 2.

Table 4.

Classification success characteristics for the best results of both methods in Data 2.

| Method |

Data area |

Cloth resolution/ voxel size [m] |

Threshold [m] |

TPR [%] |

TNR [%] |

BA [%] |

FS [%] |

| CSF |

Boulders |

0.025 |

0.25 |

99.35 |

99.57 |

99.46 |

99.32 |

| MSVC |

|

0.140 |

- |

99.67 |

99.69 |

99.68 |

99.58 |

| CSF |

Tower |

0.050 |

0.15 |

97.93 |

98.57 |

98.25 |

97.56 |

| MSVC |

|

0.110 |

- |

99.78 |

98.00 |

98.89 |

97.95 |

| CSF |

Rugged |

0.050 |

0.25 |

98.51 |

98.16 |

98.33 |

97.88 |

| MSVC |

|

0.110 |

- |

99.20 |

98.82 |

99.01 |

98.71 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).