1. Introduction

Herpesviruses are a family of large (100-200 nm) enveloped DNA-containing viruses that infect humans and animals. Infections caused by herpesviruses can manifest in various forms, from localized inflammation to generalized forms and malignant tumors. Due to the ability to persist in the human body throughout life, the virus that has entered creates a constant threat of reactivation with the slightest disruption of the immune system [

1,

2].

The herpesvirus family is divided into three subfamilies and 8 types of viruses that affect the human body - alpha (herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2, as well as varicella-zoster virus), beta (cytomegalovirus, herpes viruses 6 and 7) and gamma (Epstein-Barr virus, virus associated with Kaposi's sarcoma KSHV) [

3,

4].

The importance of studying the means of diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of herpesvirus infections is added by the fact that when the virus enters the body of a pregnant woman, it can with a high probability infect the fetus. This, in turn, can result in a wide range of consequences - from latent infection in newborns to congenital malformations and developmental disorders [

5].

Cytomegalovirus is widely spread in nature and is the most common form of fetal infection, occurring in 0.5-2% of all newborns [

5,

6,

7]. Infection of the fetus in early pregnancy with primary CMV infection can have severe consequences for it - deafness, blindness, mental retardation, cerebral palsy, bone marrow, liver, gastrointestinal tract damage, and can also cause complications during pregnancy, resulting in death of the newborn in 10-20% of cases [

8].

One of the treatment options for CMVI and HSV is etiotropic chemotherapy - treatment with chemical agents aimed at eliminating or weakening the action of the infectious agent (cause of the disease). Currently the first-line drugs for the treatment of CMVI are ganciclovir (GCV) and its metabolic precursor - valine ester of valganciclovir (Val-GCV), however, with long-term use in conditions of immune suppression, there is a high likelihood of developing viral resistance to these drugs [

9,

10,

11]. Another problem associated with the use of these drugs is the presence of serious side effects such as neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, toxic effects on the CNS, anemia, leukopenia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea. In addition, their carcinogenic, teratogenic effect, and toxic effects on the gonads have also been identified in experiments [

12,

13,

14].

Herpes simplex viruses (HSV-1 and HSV-2) in case of infection also remain in the body for life and can pose a significant danger to people with immunosuppression. In 2016, the prevalence of HSV-1 was estimated at 66.6% among the entire population of the Earth aged 16 to 49 years [

15,

16].

Similarly to CMV, the most effective way to turn HSV into a latent state is etiotropic chemotherapy. The drugs routinely used for this purpose in clinical practice are inhibitors of viral DNA polymerase. First-generation drugs, such as idoxuridine (IDU), trifluridine (TFT), have already been withdrawn from circulation due to their high toxicity, mutagenic and teratogenic effects. They were replaced by second-generation drugs such as acyclovir (ACV), bromovinyl-deoxyuridine (BVDU), penciclovir (PCV), valacyclovir (Val-ACV), and famciclovir (FCV) [

17,

18].

As becomes clear from the description of approaches to chemotherapy of CMV and HSV-1 infections, there are several problems that can lead to low treatment effectiveness. Among them are the emergence of resistance and a long list of side effects and restrictions on intake. Overcoming these obstacles is extremely important to search and test new anti-herpetic drugs. They can be similar in structure to already used drugs and acting on the same principle, as well as blocking other targets, drugs for action on which have not yet been introduced into circulation.

The backbones of spirocyclic derivatives of oxepines (8-oxaspiro[5.6]dodecanes) and azepanes (8-azaspiro[5.6]dodecanes) can undoubtedly be attributed to the so-called "privileged structures" in medical chemistry, which is explained by the wide and diverse spectrum of biological activity of derivatives of oxepines and azepanes [

19,

20]. The key features of spirocyclic heterocycles are: (1) the possibility of selective and independent functionalization; (2) controlled conformational behavior of the bicyclic spirocyclic nucleus; (3) Pronounced chelating properties. The antiviral activity of spirocyclic derivatives of oxepines and azepanes has never been studied in relation to herpes virus and cytomegalovirus.

The aim of this study was to investigate the cytotoxicity and antiviral activity of a series of experimental drugs against two human viruses of the Herpesviridae family, cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus type 1.

2. Materials and Methods

NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker Avance 400 instrument with operating frequency of 400 and 100 MHz, respectively, and calibrated using residual undeuterated chloroform (δH = 7.27 ppm) and CDCl3 (δC = 77.16 ppm) or undeuterated dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (δH=2.50 ppm) and DMSO-d6 (δC = 39.51 ppm) as internal references. The following abbreviations are used to set multiplicities: s = singlet, d =doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet, br = broad. The purity of the final compounds was checked by liquid chromatography-mass-spectrometry (LCMS) in a Shimadzu LCMS-2010A using three types of detection systems such as EDAD, ELSD, and UV. High Resolution Mass Spectra (HRMS) were registered on a Sciex TripleTOF 5600+. We used commercial reagents and solvents without further purification. Reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) performed on Merck TLC Silica gel plates (60 F254), using a UV light for visualization and basic aqueous potassium permanganate or iodine fumes as a developing agent.

2.1. Tested Compounds

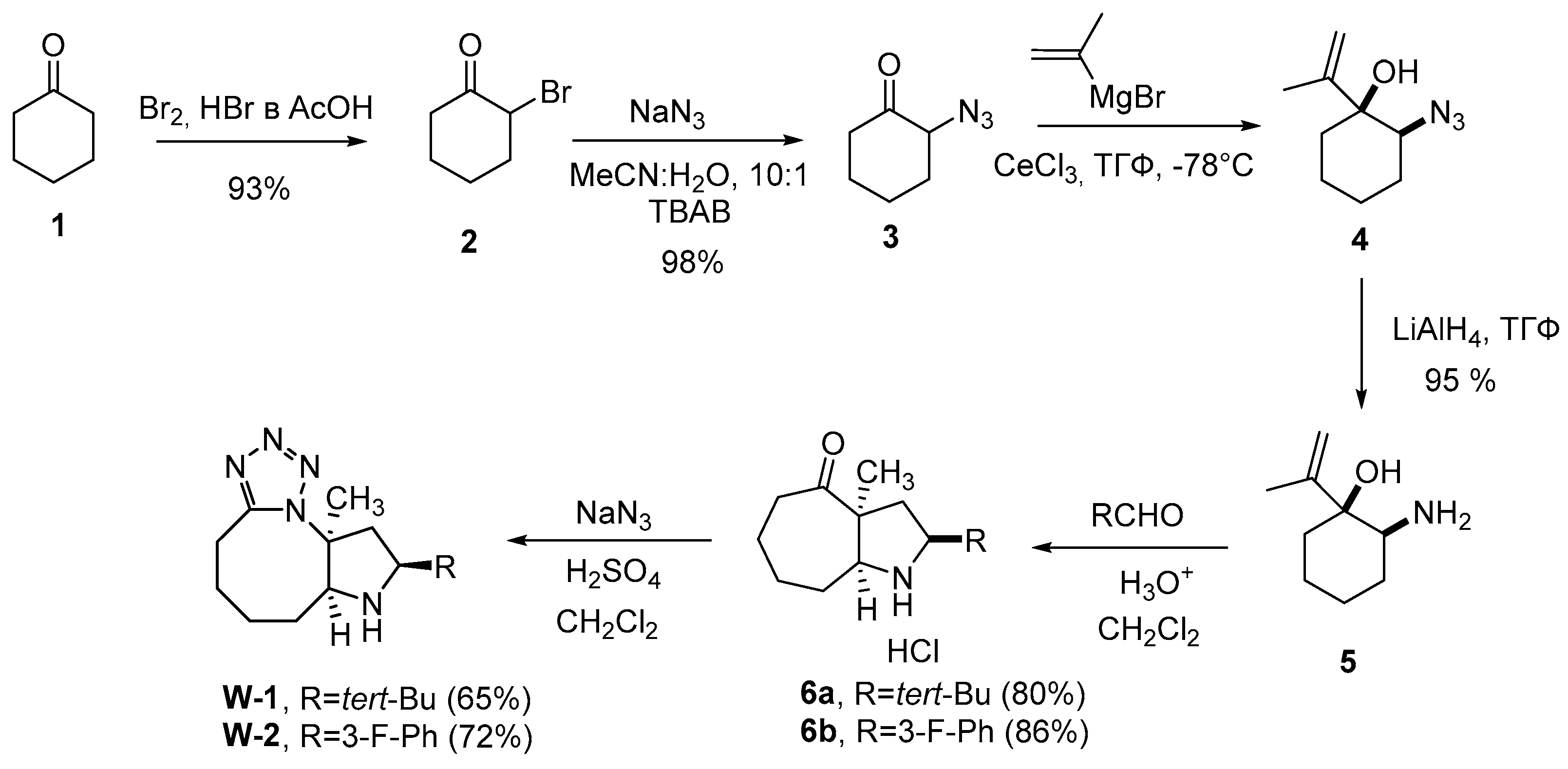

Compounds W-1 and W-2 were synthesized in 6 steps from cyclohexanone (1). As a result of bromination of compound 1, derivative 2 was obtained, from which azide 3 was obtained by nucleophilic substitution of the bromine atom. Compound 5 was synthesized by addition of Grignard reagent using anhydrous CeCl3 to a carbonyl group in 3 and following reducing of the amino group with lithium aluminum hydride. Aza-Cope/Mannich reaction with appropriate aldehydes and Schmidt reaction [

21] were used at the last two steps respectively to obtain desired compounds W-1 and W-2 (

Scheme 1).

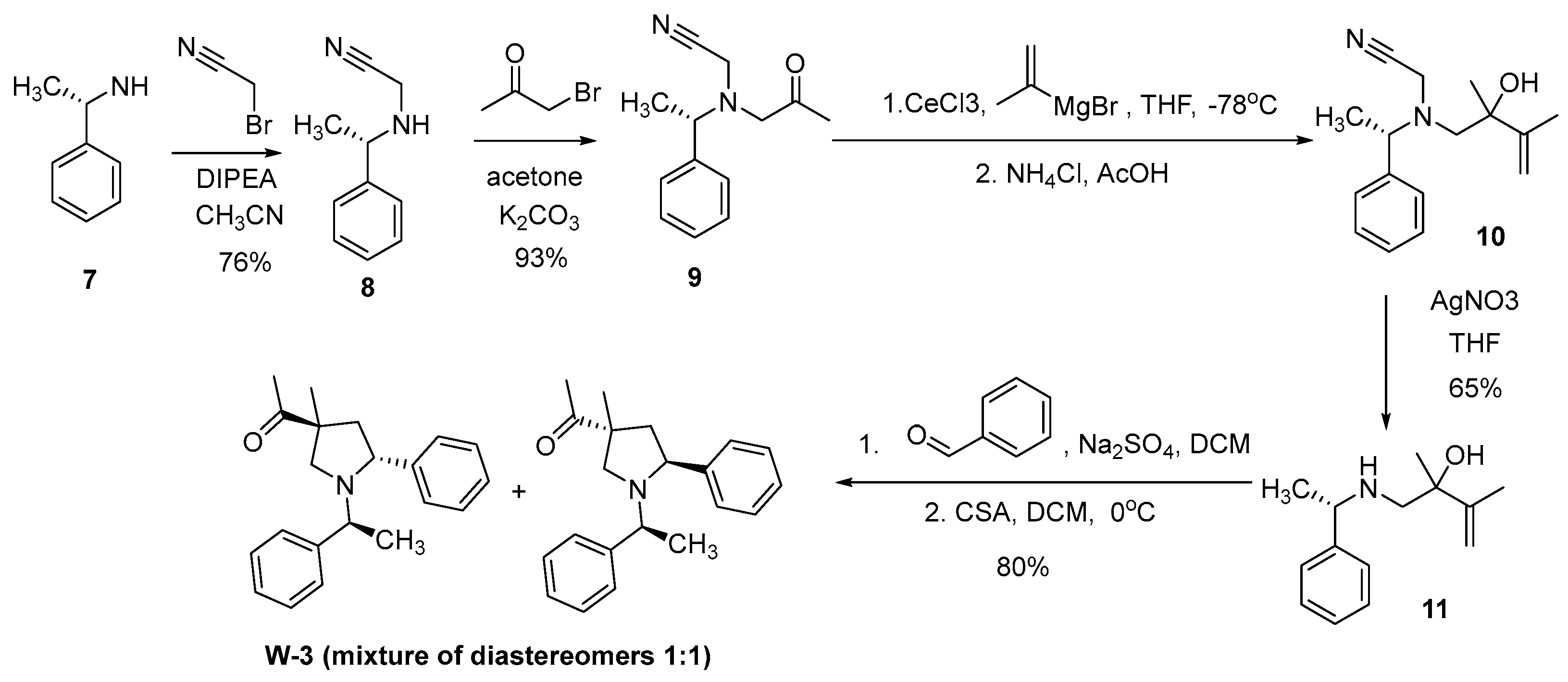

For the synthesis of the pyrrolidine derivative W-3, we chose the approach shown in

Scheme 2. Aza-Cope/Mannich reaction was also used at the key stage of the synthesis. The transformation of non-cyclic aminoethanols into substituted pyrrolidines was first described in the works of Larry Overman [

22,

23,

24]. This approach allows to control the stereochemistry of the reaction products. For the synthesis of amino alcohol 11, a four-step approach was chosen, including alkylation of commercially available (S)-phenylethylamine (7) with bromoacetonitrile and obtaining aminoketone 9 as a result of treating secondary amine 8 with bromoacetone. The reaction is carried out in acetone, strictly controlling the amount of secondary amine, it must always be in a slight excess. Amino ketone 9 containing a cyanomethyl protecting group (-CH2CN) was treated with a Grignard reagent in the presence of CeCl3 to afford alcohol 10. To remove the cyanomethyl group, we used a literature approach [

22,

25] based on the using of silver salts (AgNO3) in tetrahydrofuran. The reaction proceeds at room temperature in 30 min and affords the target amino alcohol 11 in 65% yield. The reaction of 1-aminobut-3-en-2-ol (11) with benzaldehyde leads to formation of an unsaturated iminium cation, which undergoes a [

3,

3]-sigmatropic Cope rearrangement to form an enol, and the concomitant intramolecular Mannich reaction leads to pyrrolidine W-3 (

Scheme 2).

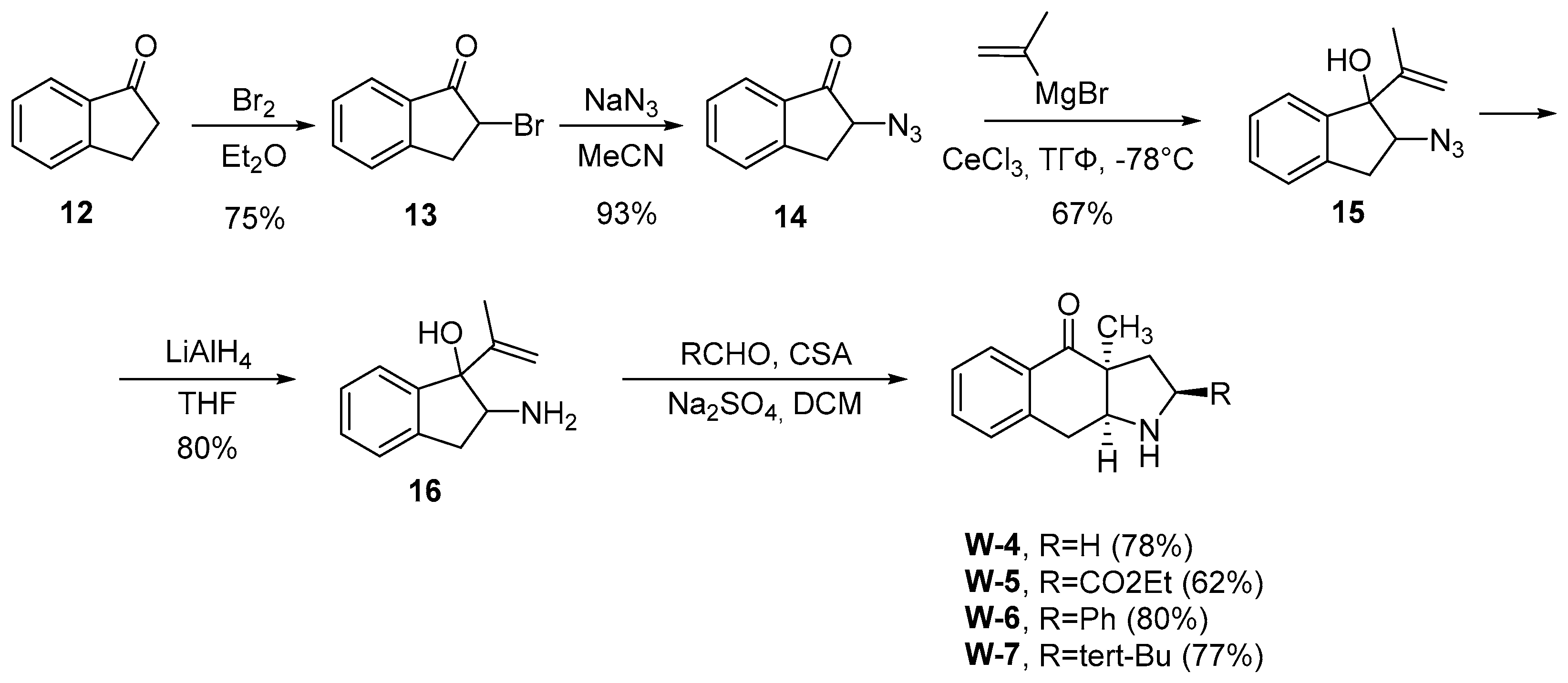

In the case of cyclic amino alcohols (e.g., amino alcohol 16), this reaction sequence leads to an increase of the cycle’s size and formation of tricyclic pyrrolidine derivatives (

Scheme 3). Due to steric limitations in the transition state, this rearrangement variant is carried out without loss of enantiomeric purity of the starting aminoethanol and, as a rule, shows high stereoselectivity [

26]. Another advantage of the Aza-Cope/Mannich reaction is the simplicity of its experimental implementation: the substrate solution is mixed with the carbonyl compound and a catalyst - a protic acid or Lewis acid (less than one equivalent). It is important to note that the transformation is not sensitive to the order of reagent addition, does not require an inert atmosphere and proceeds at room temperature or with slight heating. In addition, the reaction is easily scalable, which allows obtaining the required quantities of azabicyclic products for further synthetic research as well as for biological experiments [

27,

28].

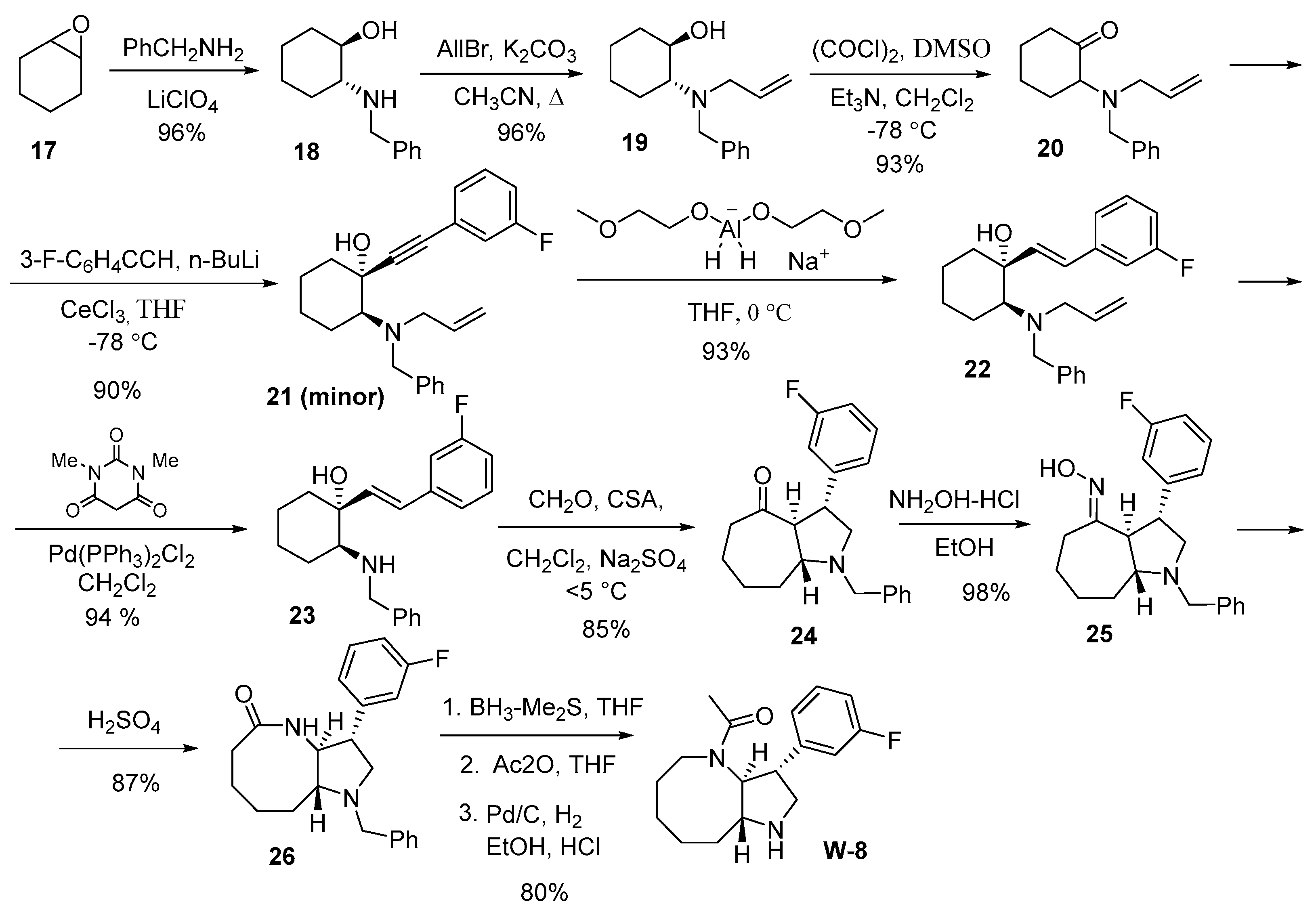

For the synthesis of the annulated derivative of pyrrolidine W-8, we used trans-bicyclic ketone 24, which was obtained in seven steps from commercially available cyclohexene oxide 17. During the synthesis of trans-ketone 24, we employed allyl protection [

29], which is easily introduced into the target substrate (by alkylating the amino alcohol with allyl bromide) and removed under mild conditions (under the action of N,N'-dimethylbarbituric acid (DMBA) in the presence of catalytic amounts of Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 (or Pd(PPh3)4), which is important for implementing multi-step syntheses [

30]. Notably, the allyl group, unlike many other protecting groups for amines, is resistant to the action of organometallic compounds and metal hydrides, which were planned to be used in synthesis.

Aminoketone 20 with an allyl protecting group at the nitrogen atom was obtained in three steps from cyclohexene oxide 17 with a total yield of 90% (

Scheme 4). In the first stage, the commercially available epoxide-ring 17 was opened with benzylamine according to a known procedure [

31]. Then, by alkylation using allyl bromide, tertiary amine 19 was obtained. For the oxidation of amino-cyclohexanol 19 in the third stage, we used the Swern oxidation, which is known to be selective and does not affect the tertiary amino groups present in the molecule [

32]. It should be noted that all stages of the synthesis proceed cleanly and do not require additional chromatographic purification. To reduce the triple bond in alkyne 21 to trans-alkene 22, we used Red-Al

® (bis(2-methoxyethoxy)aluminum hydride) as the reducing agent, which allows to obtain products with high yields and good purity.

For the transformation of trans-ketone 24, obtained using the Aza-Cope/Mannich reaction [

22], into lactam 26, the ketone was successively treated with hydroxylamine hydrochloride and concentrated sulfuric acid. The amide group in lactam 26 was reduced using the BH

3-(CH

3)

2S complex in tetrahydrofuran, which allowed for the formation of the annelated homoazepane (azocan) with pyrrolidine. Subsequent treatment with acetic anhydride and debenzylation yielded the trans-annulated derivative pyrrolo[3,2-b]azocin W-8. The total yield for the 12-step synthesis was 40%.

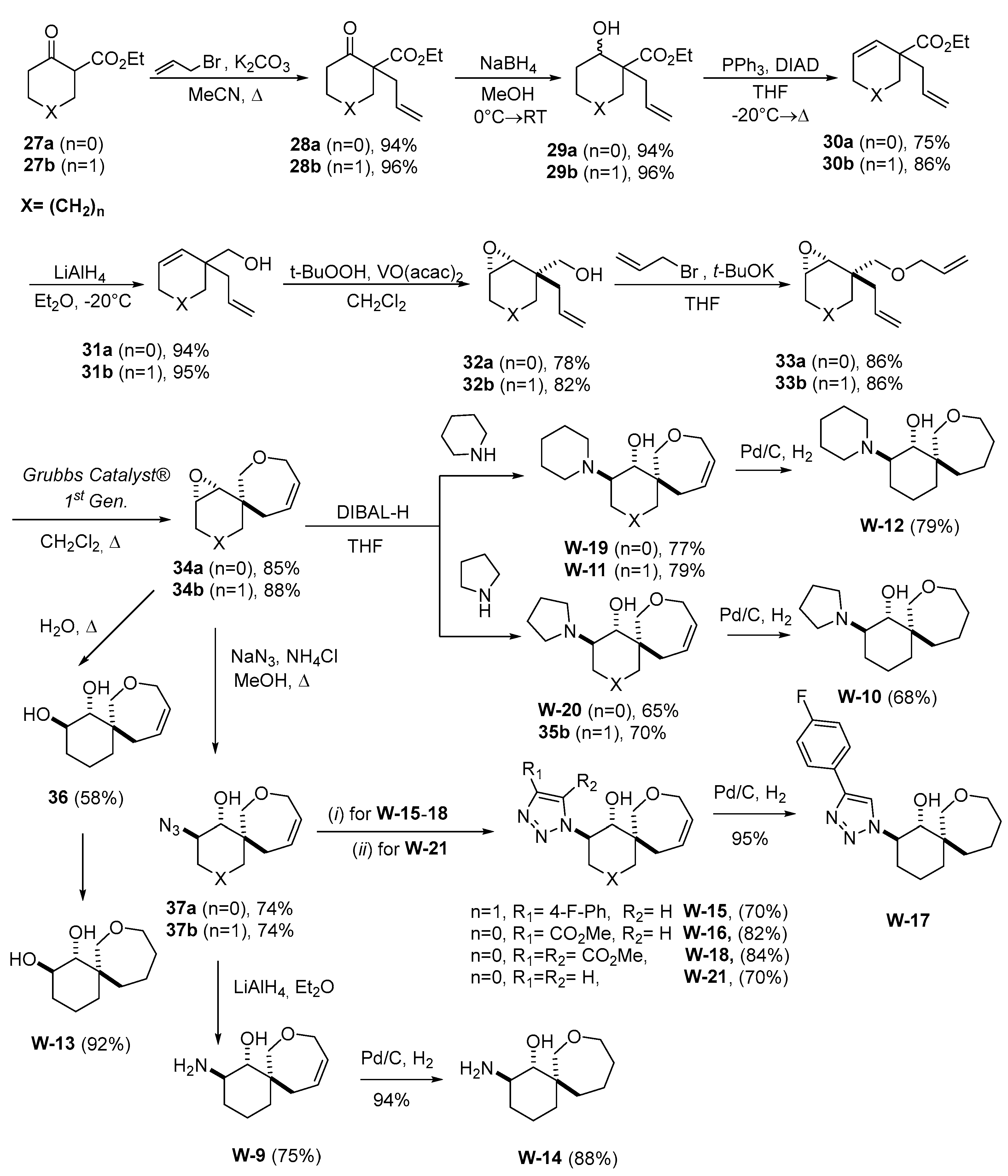

In a recent work, a set of spirocyclic derivatives based on 8-oxaspiro[5.6]dodecane and 7-oxaspiro[4.6]undecane were synthetized and in-vitro profiled against the hNNMT target to evaluate their anticancer therapeutic potential [

33] (

Scheme 5).

The epoxides 34a and 34b can be used as a substrate for a nucleophilic attach leading to unprecedented compound arrays suitable for biological screening purposes (

Scheme 5). To carry out the metathesis reaction was necessary to synthesize ethers 33a and 33b, which were obtained from alcohols 32a and 32b. The synthesis of isomeric alcohols, in turn, was performed in five steps from a commercially available ketoesters 27a and 27b. The total yields over seven stages for epoxides 34a and 34b were 47% and 37%, respectively. The nucleophilic attach, to the epoxide ring of the spiro-compounds 34a and 34b, proceeds in a regioselective manner, with the nucleophile preferring the less hindered site (W-11, W-19, W-20,

Scheme 5), this in agreement with the literature reports available [

34,

35].

The Azides 37a and 37b were obtained from the epoxides 34a and 34b by epoxide ring opening with azide-anion. Then, for example, the 1,2,3-triazole W-15 was synthesized by a “click-reaction” with the 1-ethynyl-4-fluorobenzene and using CuSO

4×5H

2O and Na-ascorbate [

34].

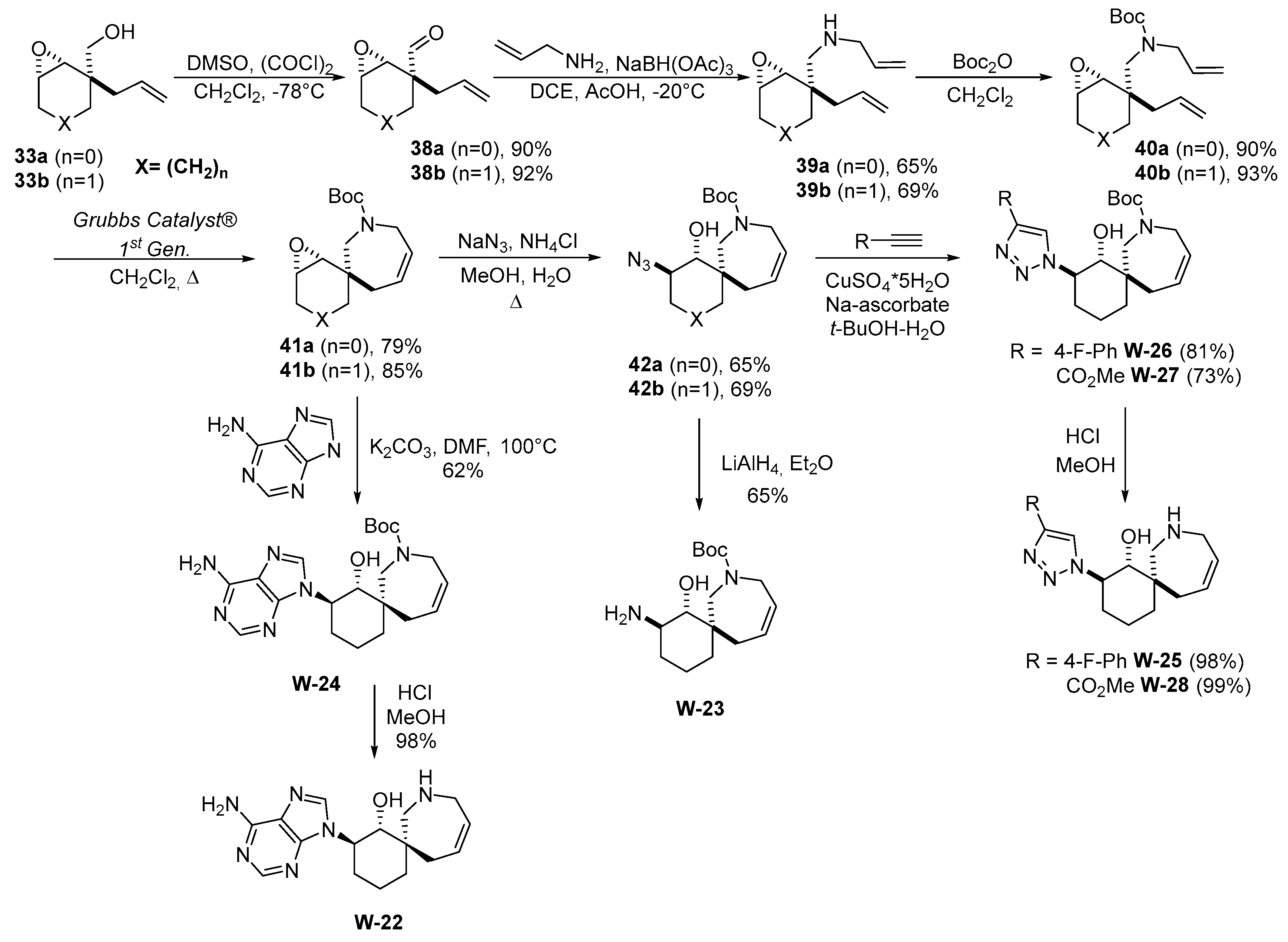

Based on their synthetic pathway (

Scheme 5), the replacement of the replacement of an oxygen atom with a nitrogen atom, thus to obtain an additional point for the functionalization of spirocycles, was envisioned. Therefore, a new synthetic approach was developed for the production of epoxides 41a and 41b from commercially available reagents.

Scheme 6 shows the synthesis of 1,2,3-triazoles W-26 and W-27, which contains an unprotected nitrogen atom in 7-membered ring.

The amine hydrochloride W-22 was obtained by removing the protecting group under acidic condition (

Scheme 6). The stereochemistry of such compounds was assigned by a comparison with a similar structure from the literature [

35].

2.2. Cell Cultures and Viruses

Two cell lines were used: Vero (African green monkey kidney cells) and MRC-5 (a diploid cell line obtained from human fibroblasts sourced from lung tissue of a male fetus aborted at 14 weeks of gestation). Both cell lines were obtained from the cell culture collection of the Laboratory of Chemotherapy of Viral Infections, Smorodintsev Research Institute of Influenza, Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation.

Cell cultures were prepared by seeding 96-well flat-bottom culture plates with a concentration of 3x105 cells/ml a day prior to experimentation. The cultures were maintented in DMEM growth medium (Biolot, Russia) supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum (Biolot, Russia) and 20 μg/ml levofloxacin. Incubation was carried out at 37 °C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere.

The following viruses were used in the study: cytomegalovirus strain AD169, herpes simplex virus type 1 strain EC, both were obtained from the working collection of the Laboratory of Chemotherapy for Viral Infections, Smorodintsev Research Institute of Influenza, Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation.

2.3. Assessment of Compound Cytotoxicity

MTT assay was conducted to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the tested compounds. For this test uninfected cells were used. Initially, the growth medium was removed from the 96-well plate containing the cell culture. Subsequently, a series of 2-fold dilutions of the compounds (dissolved in DMSO) were added to the supporting medium (starting concentration 2000 μg/ml), while the control wells received medium without any compound. The 96-well plate containing the compound dilutions was then incubated for 3 days (for Vero cells) and 10 days (for MRC-5 cells).

Following the incubation period, the supporting medium was discarded and an MTT solution was added at a concentration of 0.5 μg/ml. The plate was incubated for 2 hours at 37 °C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere. After the incubation, the MTT solution was removed and the formed precipitate was dissolved in DMSO. The absorbance of the resulting solution was measured at a wavelength of λ max = 630 nm using the Allsheng AMR-100 microplate reader (China). Based on data obtained, the CC₅₀ (the compound concentration that induces 50% cell death) was determined using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software.

2.4. Antiviral Activity Assessment

To assess the antiviral activity of the compounds against both viruses under investigation, we employed established non-toxic concentrations, with the highest being 1/2 CC50.

HSV1. To assess the antiviral activity of compounds against herpes simplex virus type 1(HSV1), a series of 3-fold dilutions of substances were prepared starting from 2 CC₅₀ in Alpha-MEM medium (Biolot, Russia), supplemented with 20 μg/ml levofloxacin and 2% fetal bovine serum (Biolot, Russia).

The diluted test substances were then added to Vero cell culture at a volume of 100 μl per well in a 96-well plate, using a double concentration. Following this, 100 μl of the virus with a concentration of at least 106 was introduced in seven 10-fold dilutions (10–1–10–7) were added and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere. The cells were then washed from the virus with supportive medium and test substance dilutions were added to the wells, followed by adding 100 μl of supportive medium to each well. The plates were then incubated for 3 days at 37°C with 5% CO₂ in a CO₂ incubator, after which cell viability was assessed using the MTT assay.

Totally, five different concentrations were used, and the virus titer was measured for each concentration. After that, a nonlinear regression analysis was performed to clarify the "virus titer" and "drug dose” relationship and the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) was calculated from the results using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. The selectivity index (SI) defined as the ratio of CC₅₀ to IC₅₀, served as the criterion for the compound. Compounds with an SI greater than 8 are regarded as promising candidates for further investigation.

CMV. To assess the antiviral activity of compounds against cytomegalovirus, a series of 3-fold dilutions of substances were prepared starting from 2 CC₅₀ in Alpha-MEM medium (Biolot, Russia), supplemented with 20 μg/ml levofloxacin and 2% fetal bovine serum (Biolot, Russia).

The prepared solutions of the test substances were added to MRC-5 cell at a volume of 100 μl per well in a 96-well plate, using a double concentration. Following this, 100 μl of the virus with a concentration of at least 106 was introduced in seven 10-fold dilutions (10–1–10–7) were added and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere. The cells were then washed from the virus with supportive medium and test substance dilutions were added to the wells, followed by adding 100 μl of supportive medium to each well.

The plates were then incubated for 10 days at 37 °C in a 5% CO₂ atmosphere, and then cell viability was assessed using phase-contrast microscopy, specifically determining the decimal logarithm of the minimal virus dilution that induced cytopatic effect (CPE) for each concentration of the compound.

Totally, five different concentrations were used, and the virus titer was measured for each concentration. After that, a nonlinear regression analysis was performed to clarify the "virus titer" and "drug dose” relationship and the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) was calculated from the results using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. The selectivity index (SI) defined as the ratio of CC₅₀ to IC₅₀, served as the criterion for the compound. Compounds with an SI greater than 8 are regarded as promising candidates for further investigation.

2.5. Time-of-Addition Assay

The time-of-addition assay was used to study the mechanism of action of the leader compounds against HSV1.

The Vero cell culture was seeded a day prior to the experiment onto a flat-bottomed 24-well culture plate at a density of 3 × 10^5 cells/ml. For cultivation, we used DMEM growth medium (Biolot, Russia) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Biolot, Russia) and 20 µg/ml of ciprofloxacin. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

The following experimental time points were evaluated:

Point -0,25-0 – The compound was added into the wells 15 minutes before viral infection. Immediately before adding the viral suspension (i.e., at time point 0), the medium containing the drug was removed, and the cells were washed twice with a medium (DMEM (Biolot, Russia) containing 20 µg/ml ciprofloxacin and 2% fetal bovine serum (Biolot, Russia)). After the viral infection and subsequent removal of the virus, the cells were again washed twice with the medium, followed by the addition of 2 ml of fresh maintenance medium.

Point 0-24 - The compound was administered 15 minutes before infection. After the virus was removed, the cells received two washes with the medium, followed by the addition of 1 ml of the medium and 1 ml of the compound at a concentration of 2 IC50.

Point 0-1 - The compound was introduced simultaneously with the viral infection. After infection and removal of the virus, 2 ml of the medium was added to the wells.

Point 4-5 – The compound was administered 4 hours post-infection, followed by a one-hour incubation. The drug was then removed, and the cells were washed twice with the medium before the addition of 2 ml of fresh medium.

Point 4-24 – The compound was administered 4 hours after infection and remained in the wells for the duration of the experiment.

The compounds were administered at a concentration equal to 2 IC50. Virus infection was performed by introducing 1 ml of a viral suspension into the designated wells of the 24-well plate. The virus was diluted to concentrations from 10-5, and the cells were incubated for 1 hour at 4 °C. After this incubation, the viral suspension was removed, and the cells were washed twice with a supportive medium.

Throughout the experimental procedure, the plates containing the cells were maintained in an incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Twenty-four hours post-infection, the cells were harvested from the plate surface using a culture scraper and titrated on a Vero cell culture. The plates were incubated for 3 days at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a CO2 incubator. Cell survival was assessed using phase contrast microscopy, and for each compound concentration tested, the decimal logarithm of the lowest dilution of the virus causing cytopathic effect (CPE) was determined.

3. Results

3.1. General Procedure for Synthesis of Compounds

W1-W2

To a solution of (1SR,2SR)-2-amino-1-(prop-1-en-2-yl)-cyclohexan-1-ol (5, 0.1 mol, 1 equivalent) and the corresponding aldehyde (0.12 mol, 1.2 equivalents) in 100 mL of methylene chloride, add p-toluenesulfonic acid monohydrate (0.09 mol, 0.9 equivalents) and a small quantity of pre-calcined 4 Å molecular sieves. Stir the mixture at room temperature for 12 hours, monitoring the reaction progress via TLC (using a 10:1 solvent system of CH2Cl2 and MeOH with PMA as a visualizing agent). Upon completion of the reaction, wash the mixture with a 50% (w/v) potassium carbonate solution, followed by a saturated aqueous sodium chloride solution. Dry the organic layer over anhydrous sodium sulfate and remove the solvent by rotary evaporation.

In a round-bottomed flask, add of the starting ketone 6 (1.0 equivalent) in dichloromethane so that the concentration is 0.2 M, and cool using a water-salt bath to -10 °C. When the temperature has reached the required level, add sulfuric acid (1.0 equivalent). Then begin adding sodium azide (1.5 equivalents), divided into 5 portions at intervals of 2 hours. After all the sodium azide has been added, add water (an amount equivalent to sulfuric acid) and begin adding aqueous ammonia solution dropwise until an alkaline medium appears (pH = 12). Then pour into water and extract with 4x100 ml of dichloromethane. Then dry over sodium sulfate, evaporate on a rotary evaporator and chromatograph. The eluent used was hexane – EtOAc (1:1). Substances for nuclear magnetic resonance analysis were prepared using DMSO-d6 as a deuterated solvent.

W3-W8

To a solution of 2-amino-1-(prop-1-en-2-yl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-1-ol (14, 1.0 eq) and the corresponding aldehyde in 10 mL of DCM was add anhydrous Na2SO4 (7 eq) and stirred 60 minutes, then add CSA (0.9 eq). Stir the mixture at room temperature for 12 hours, monitoring the reaction progress via TLC. Then reaction mixture was washed with saturated solution of NaHCO3, organic layer was separated, solvent was evaporated and residue was purified by column chromatography.

W-9 – W-28 were synthesized previously. Full spectral characterization data are agreeing with previously described data [

33,

35,

36].

3.2. Cytotoxicity of Compounds on Cell Cultures

In the initial phase of the experiment, we evaluated the cytotoxicity of the test substances on two cell lines: Vero cells, which are used as host cells for herpes simplex virus type 1, and MRC-5 cells, which serve as host cells for cytomegalovirus. The findings from the cytotoxicity tests are summarized in

Table 1.

The data demonstrates that the test substances exhibit a range of toxicity levels, including mildly, moderately, and highly toxic effects on both cell cultures.

3.3. Antiviral Activity of Compounds

At the next step compounds were tested to assess their antiviral activity, results are presented at

Table 2.

Of the substances examined, four compounds demonstrated significant activity against cytomegalovirus: W-3, W-10, W-11, and W-15. Additionally, four compounds exhibited effectiveness against herpes simplex virus: W-9, W-11, W-13, and W-15. Notably, only two compounds, W-11 and W-15, showed activity against both viruses.

3.4. Time-of-Addition Assay Results

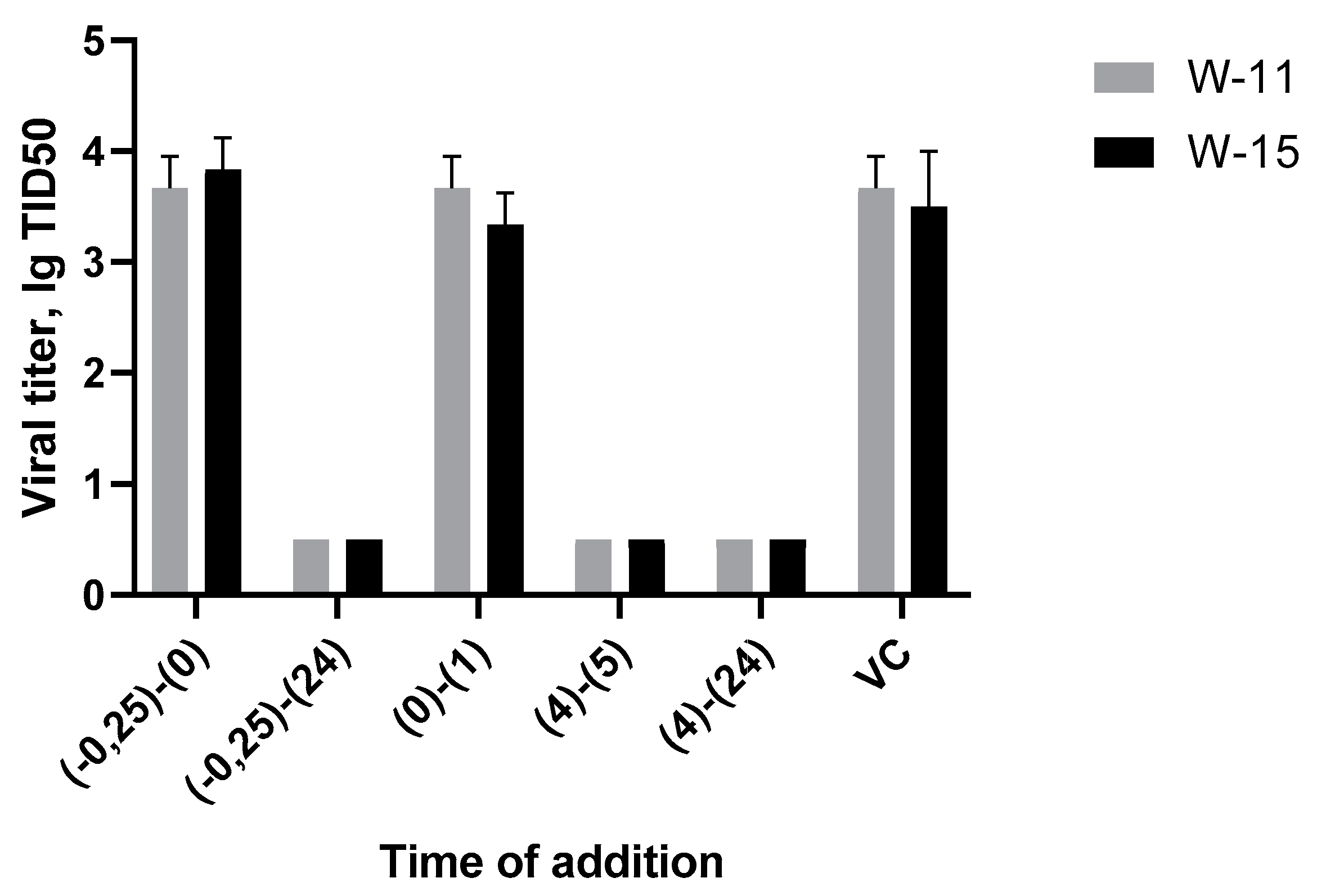

In this experiment, we investigated the various stages of the HSV-1 life cycle to identify where potential therapeutic agents exert their effects. Two compounds, W-11 and W-15, were used in the study due to their demonstrated activity against both HSV-1 and CMV, as well as their notable highest SI concerning HSV-1. The findings from this study yielded the following results:

Figure 1.

The results of time-of-addition assay.

Figure 1.

The results of time-of-addition assay.

The graphs indicate that the virus titer for the points labeled 0.25-0 and 0-1 is equivalent to that of the virus control. This suggests that the substance does not inhibit the binding of the viral particle to the cell or its penetration. Additionally, no signs of cytopathic effects were observed at the points 0.25-24, 4-5, and 4-24.

Consequently, it can be inferred that the substance exerts its effects during viral gene replication, with viral DNA polymerase as the most likely target. Inhibiting this enzyme would subsequently halt the synthesis of viral proteins within the cell.

4. Discussion

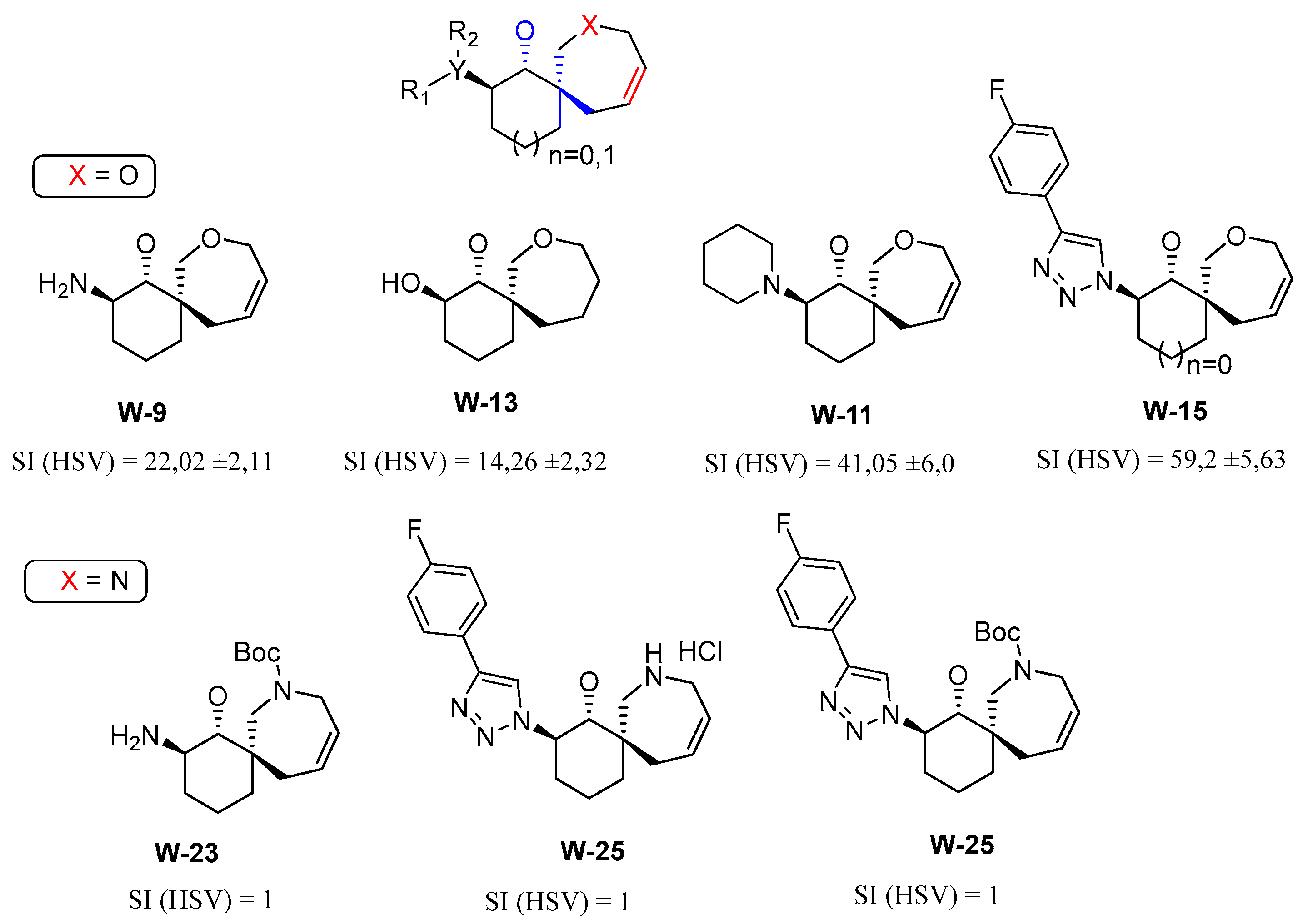

The results of biological tests demonstrated that derivatives of spirocyclic oxepins exhibit significant activity in the low micromolar range against cytomegalovirus, specifically in four compounds: W-3, W-10, W-11, and W-15. Similarly, four compounds—W-9, W-11, W-13, and W-15—showed efficacy against herpes simplex virus. Notably, two compounds, W-11 and W-15, were effective against both viruses.

It is important to highlight that among the 28 compounds analyzed, the derivatives of spirocyclic azepanes (W-22 to W-28) and di- or tri-cyclic pyrrolidines (W-4 to W-6), which feature a keto group in their carbocyclic structure, exhibited the lowest levels of activity. In contrast, among the non-cyclic pyrrolidines, compound W-3—characterized by a phenyl group at the C-2 position and a phenethyl fragment attached to the nitrogen atom of the pyrrolidine ring—demonstrated the highest activity against cytomegalovirus.

We posit that the activity of several spirocyclic oxepins featuring a trans-aminoethanol fragment in their structure (specifically W-9, W-11, and W-15) can be attributed to phosphorylation processes occurring in the cytoplasm of the cell. These processes ultimately result in the inhibition of viral DNA polymerase.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the antiviral activity of derivatives of spirocyclic oxepins (X=O) and spirocyclic azepanes (N=O).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the antiviral activity of derivatives of spirocyclic oxepins (X=O) and spirocyclic azepanes (N=O).

The antiviral activity of spirooxepin W-13 can be attributed to the presence of a trans-diol fragment in its structure. This fragment appears to inhibit the binding and penetration of the herpes simplex virus by directly interacting with the phospholipids on the cell surface, which are essential for viral entry and stabilization within the host cell. Furthermore, cytotoxicity studies involving 28 compounds were conducted on Vero and MRC-5 cell cultures. Notably, all the compounds tested demonstrated non-toxic effects on these cell lines.

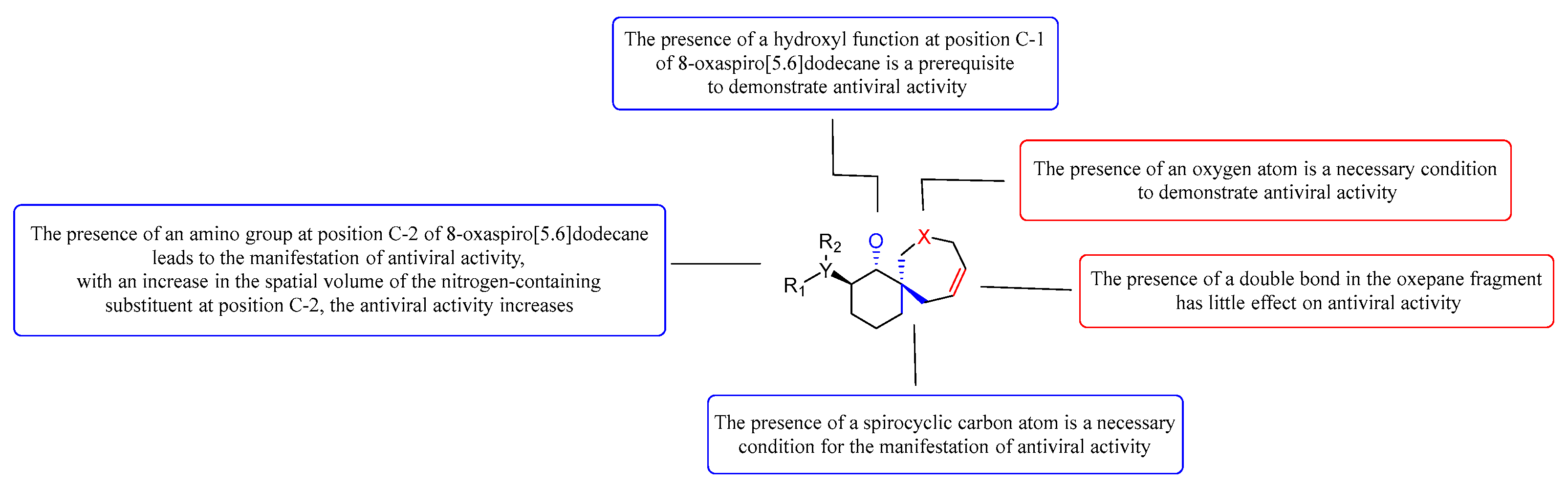

The analysis of the structure-activity relationship (SAR) of new pyrrolidine, oxepine, and azepane derivatives reveals a significant correlation between the biological activity of these compounds and the presence of a spirocyclic carbon atom in their structure. Notably, the incorporation of annelated cycles (compounds W-4 to W-6) results in a marked decrease in antiviral activity, yielding a selectivity index (SI) of less than 10. Furthermore, the evaluation of spirocyclic derivatives indicates that those containing an azepam fragment (compounds W-22 to W-28) do not exhibit antiviral activity against herpes virus and cytomegalovirus. In contrast, spirocycles that include an oxepan fragment (compounds W-3, W-9, W-11, W-13, and W-15) demonstrate significant activity against both viruses, with SIs exceeding 10.

It is important to note that the presence of an oxygen atom in the spirocyclic nucleus and the presence of an 8-oxaspiro[5.6]dodecane hydroxyl function in the α-position are critical prerequisites for the manifestation of antiviral activity.

Figure 3.

Summary of the study of the structure-activity relationship.

Figure 3.

Summary of the study of the structure-activity relationship.

Trans-aminoethanol derivatives of spirooxepanes (W-9, W-10, W-11, W-15) exhibit "moderate antiviral activity," indicating that modifications to the amino group enhance the antiviral potency of these compounds. Notably, as the spatial volume of the nitrogen-containing heterocycle increases, so does the activity. Among these, W-11 demonstrates the highest activity, with herpes simplex virus (HSV) inhibition of 41.048 ± 6 and cytomegalovirus (CMV) inhibition of 97.2 ± 9.88, which can be attributed to the presence of a trans-piperidinecyclohexanol fragment in its structure.

Additionally, the presence of a double bond within the oxepane moiety appears to amplify antiviral activity. For instance, compound W-9 shows an HTI (HSV) of 22.02 ± 2.11, while its saturated counterpart, W-14, is completely inactive (HTI (HSV) = 1), despite having comparable toxicity values (CC50 (Vero) = 473.5 for W-9 and 346.7 for W-14). A similar trend is observed between compounds W-11 (with a double bond) and W-12 (the saturated analogue); antiviral activity is found only in W-11 ((HSV) = 41.048 ± 6 and (CMV) = 97.2 ± 9.88), whereas the cytotoxicity values are CC50 (Ver o) = 513.1 for W-11 and 467.8 for W-12.

The structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis reveals that new derivatives of spirocyclic oxepines possess antiviral properties, in contrast to spirocyclic azepanes and annelated pyrrolidines (W-4, W-5, W-6), where the toxicity of the spirocyclic compounds is either comparable to or significantly higher than that of the annelated pyrrolidine derivatives. Overall, it can be concluded that the active compounds among the spirocyclic oxepine derivatives typically incorporate a double bond and a trans-aminoethyl fragment within the oxepane structure.

Notably, derivatives such as 2-amino-8-oxaspiro[5.6]dodec-10-en-1-ol (W-9, W-11, and W-13) display higher activity than 2-amino-7-oxaspiro[4.6]undec-9-en-1-ol (W-16, W-18, W-21), although there are exceptions, such as compound W-15. The incorporation of a saturated ring in spirooxepines correlates with increased antiviral activity (e.g., W-11), and a similar enhancement is observed with the introduction of a 4-(para-fluoro)phenyltriazole fragment at the C-3 position of the spirocycle (W-15).

Furthermore, we explored the antiviral potential of trisubstituted pyrrolidines containing aromatic fragments and a carbonyl group (β-proline derivatives). It is essential that the pyrrolidine includes a bulky substituent at the second position of the ring to achieve optimal activity. However, chemical modifications to the aromatic fragment at the C-2 position of spirooxepine derivatives, aimed at generating additional pharmacophoric groups, often result in a loss of antiviral activity. Attempts to introduce a nitrogenous base residue at this position (such as in compounds W-22 and W-24) led to diminished antiviral efficacy and substantially increased cytotoxicity.

5. Conclusions

Twenty-eight compounds were evaluated for their efficacy against two herpesviruses: cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus. Several promising lead compounds demonstrating activity against these pathogens were identified, and the fundamental structure-activity relationships were established. Additionally, the impact of the timing of active drug administration was investigated, leading to a hypothesis regarding the potential mechanism of action linked to the function of viral polymerase.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. NMR of tested compounds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.S., A.V.K; methodology, A.A.S.; antiviral activity against HSV1, D.N.R; antiviral activity against CMV, M.M.K and Y.V.N; time-of-addition assay, D.N.R.; performed the chemical synthesis, I.R.I., D.A.T., E.R.L., E.V.M. and F.A.Z.; the registration and interpretation of the NMR data and structure characterization of active compounds were conducted by I.R.I. and D.A.T.; writing—original draft preparation I.R.I., E.R.L., D.A.T.; writing—review and editing I.R.I., A.V.K. and A.A.S.; supervision, A.A.S.; project administration, A.A.S.; funding acquisition, A.A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The State Assignment of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation: 'Molecular Biological Approaches for Developing a New Drug to Treat Diseases Caused by Herpes Simplex Virus Strains Resistant to Current Etiotropic Treatments' (TVKQ-2024-0004).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grinde, B. Herpesviruses: Latency and reactivation—Viral strategies and host response. Journal of oral microbiology. 2013, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asyesha, R.; Murtaz-ul-Hasan, K.; Akhtar, N. Recent understanding of the classification and life cycle of herpesvirus: A review. Science Letters. 2017, 5, 195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, P.R.; Rosenthal, K.S.; Pfaller, M.A. Medical Microbiology, 5th ed.; Elsevier Mosby: St. Louis, Missouri, USA, 2005; pp. 963 p. ISBN 978-0-323-03303-9. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Muñoz, M.E.; Fuentes-Pananá, E.M. Beta and Gamma Human Herpesviruses: Agonistic and Antagonistic Interactions with the Host Immune System. Front. Microbiol 2018, 8, 2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engman, M.L.; Malm, G.; Engstrom, L.; Petersson, K.; Karltorp, E.; Tear, F.K.; Uhlen, I.; Guthenberg, C.; Lewensohn-Fuchs, I. Congenital CMV infection: Prevalence in newborns and the impact on hearing deficit. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008, 40, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahmias, A.J.; Walls, K.W.; Stewart, J.A.; Herrmann, K.L.; Flynt, W.J. The ToRCH complex-perinatal infections associated with toxoplasma and rubella, cytomegol- and herpes simplex viruses. Pediatr Res. 1971, 5, 405–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, P.; Batra, M.; Singh, S. Epidemiology of TORCH Infections and Understanding the Serology in Their Diagnosis. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. 2023, 7, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andronova, V.L. Modern ethiotropic chemotherapy of human cytomegalovirus infection: Clinical effectiveness, molecular mechanism of action, drug resistance, new trends and prospects. Part 1. Voprosy Virusologii (Problems of Virology, Russian journal). (In Russ). 2018, 63, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubonosova, E.Yu.; Namazova-Baranova, L.S.; Vishneva, E.A.; Mayanskiy, N.A.; Kulichenko, T.V.; Soloshenko, M.A. Cytomegalovirus Infection in Adolescents of Russian Federation: Results of Cross-Sectional Population Analysis of Seroprevalence. Pediatric pharmacology. (In Russ). 2021, 18, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstee, M.I.; Cevirgel, A.; de Zeeuw-Brouwer, ML.; et al. Cytomegalovirus and Epstein–Barr virus co-infected young and middle-aged adults can have an aging-related T-cell phenotype. Sci Rep. 2023, 13, 10912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, R.; Jana, S.; Patra, S.; Haldar, P.K.; Bhowmik, R.; Mandal, A.; et al. Chapter 20 - Insights into the mechanism of action of antiviral drugs. In How Synthetic Drugs Work; Kazmi, I., Karmakar, S., Shaharyar, Md. A., Afzal, M., Al-Abbasi., *!!! REPLACE !!!*, F.A., *!!! REPLACE !!!*, Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, 2023; pp. 447–475. ISBN 9780323998550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britt, W.J.; Prichard, M.N. New therapies for human cytomegalovirus infections. Antiviral Res Epub 2018 Sep 15. 2018, 159, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demin, M.V.; Tikhomirov, D.S.; Biderman, B.V.; Glinshchikova, O.A.; Drokov, M.Yu.; Sudarikov, A.B.; Tupoleva, T.A.; Filatov, F.P. Mutations in the cytomegalovirus UL97 gene associated with ganciclovir resistance in recipients of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants. Kliniceskaa Mikrobiologia i Antimikrobnaa Himioterapia (In Russ.). 2019, 21, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obshcherossiyskaya obshchestvennaya organizatsiya sodeystviya razvitiyu neonatologii «Rossiyskoye obshchestvo neonatologov» [All-Russian public organization for promoting the development of neonatology “Russian Society of Neonatologists”], Obshchestvennaya organizatsiya «Rossiyskaya assotsiatsiya spetsialistov perinatal'noy meditsiny» [Public organization "Russian Association of Perinatal Medicine Specialists"]. Clinical recommendations Vrozhdennaya tsitomegalovirusnaya infektsiya [Congenital cytomegalovirus infection]. Moscow, 2023. 62p.

- Zarrouk, K.; Zhu, X.; Pham, V.D.; Goyette, N.; Piret, J.; Shi, R.; Boivin, G. Impact of Amino Acid Substitutions in Region II and Helix K of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 and Human Cytomegalovirus DNA Polymerases on Resistance to Foscarnet. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2021, 65, e0039021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zarrouk, K.; Piret, J.; Boivin, G. Herpesvirus DNA polymerases: Structures, functions and inhibitors. Virus Res 2017, 234, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, Ch.; Harfouche, M.; Welton, N.; Turner, K.; Abu-Raddad, L.; Gottlieb, S.; Looker, K. Herpes simplex virus: Global infection prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2020, 98, 315–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andronova, V.L. Modern ethiotropic chemotherapy of herpesvirus infections: Advances, new trends and perspectives. Alphaherpesvirinae (part I). Voprosy Virusologii (Problems of Virology, Russian journal) (In Russ). 2018, 63, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belen’kii, L.I. Part 13. Seven-membered Heterocyclic Rings and their Fused Derivatives. In Comprehensive Heterocyclic Chemistry III; Katritzky, A.R., Scriven, E.F.V., Ramsden, Ch.A., Taylor, R.J.K., Eds.; Elsevier Science, Ltd.: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2008; pp. 45–95. ISBN 978-008044992-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiacchio, M.A.; Legnani, L.; Chiacchio, U.; Iannazzo, D. Chapter 16. Recent Advances on the Synthesis of Azepane-Based Compounds. In More Synthetic Approaches to Nonaromatic Nitrogen Heterocycles. Recent Advances on the Synthesis of Azepane-Based Compounds, Phillips, A.M.M.M.F.; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Oxford, England, 2022; pp. 529–558. ISBN 9781119757153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belov, D.S.; Ratmanova, N.K.; Andreev, I.A.; Kurkin, A.V. Synthesis of Bicyclic Proline Derivatives by the Aza-Cope–Mannich Reaction: Formal Synthesis of (±)-Acetylaranotin. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 4141–4147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overman, L.E.; Jacobsen, E.J.; Doedens, R.J. Synthesis Applications of Cationic Aza-Cope Rearrangements. Part 13. Stereoselective Synthesis of Cis- and Trans-3a-Aryl-4-oxodecahydrocyclohepta[b]pyrroles. J. Org. Chem. 1983, 48, 3393–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overman, L.E.; Mendelson, L.T.; Jacobsen, E.J. Synthesis Applications of Aza-Cope Rearrangements. 12. Applications of Cationic Aza-Cope Rearrangements for Alkaloid Synthesis. Stereoselective Preparation of Cis-3a-Aryloctahydroindoles and a New Short Route to Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids. J. Org. Chem. 1983, 105, 6629–6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overman, L. E.; Sugai, S. Total Synthesis of (-)-Crinine. Use of Tandem Cationic Aza-Cope Rearrangement/Mannich Cyclizations for The Synthesis of Enantiomerically Pure Amaryllidaceae Alkaloids. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1985, 68, 745–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guibe, F.; Grierson, D. S.; Husson, H.-P. 2-Cyano Δ3piperideine VII1: The condensation of 2-cyano Δ3piperideine with sodium dimethylmalonate catalyzed by ZnCl2 or zero valent palladium and platinum complexes. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982, 23, 5055–5058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, E.J.; Levin, J.; Overman, L.E. Synthesis applications of cationic aza-Cope rearrangements. Part 18. Scope and mechanism of tandem cationic aza-Cope rearrangement-Mannich cyclization reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 4329–4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belov, D.S.; Lukyanenko, E.R.; Kurkin, A.V.; Yurovskaya, M.A. Synthesis of (3RS,3aSR,8aSR)-3-phenyloctahydrocyclohepta[b]pyrrol-4(1H)-one via the aza-Cope–Mannich rearrangement. Tetrahedron Letters 2011, 67, 9214–9218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belov, D.S.; Lukyanenko, E.R.; Kurkin, A.V.; Yurovskaya, M.A. Highly stereoselective and scalable synthesis of trans-fused octahydrocyclohepta[b]pyrrol-4(1H)-ones via the aza-Cope–Mannich rearrangement in racemic and enantiopure forms. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 10125–10134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wuts, P.G.M.; Greene, T.W. Protective Groups in Organic Synthesis, 4th ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, New Jersey, USA, 2006; pp. 1110 P. ISBN 978-0-471-69754-1. [Google Scholar]

- Garro-Helion, F.; Merzouk, A.; Guibe, F. Mild and selective palladium(0)-catalyzed deallylation of allylic amines. Allylamine and diallylamine as very convenient ammonia equivalents for the synthesis of primary amines. J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 6109–6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffers, I.; Bolm, C. Synthesis and resolution of racemic trans-2-(N-benzyl)amino-1-cyclohexanol: Enantiomer separation by sequential use of (R)- and (S)-mandelic acid. Org. Synth. 2008, 85, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, A. J.; Huang, S. L.; Swern, D. J. Oxidation of long-chain and related alcohols to carbonyls by dimethyl sulfoxide "activated" by oxalyl chloride. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 2480–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iusupov, I.R.; Lukyanenko, E.R.; Altieri, A.; Kurkin, A.V. Design and Synthesis of Fsp3-Enriched Spirocyclic-Based Biological Screening Compound Arrays via DOS Strategies and Their NNMT Inhibition Profiling. ChemMedChem. 2022, 17, e202200394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraga, C.A.M.; Teixeira, L.H.P.; Menezes, C.M.S.; Sant′Anna, C.M.R.; Conceição, M.; Ramos, K.V.; Neto, F.R.A.; Barreiro, E.J. Studies on diastereoselective reduction of cyclic β-ketoesters with boron hydrides. Part 4: The reductive profile of functionalized cyclohexanone derivatives. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 2745–2755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iusupov, I.R.; Lyssenko, K.A.; Altieri, A.; Kurkin, A.V. (1RS,2RS,6RS)-2-(6-Amino-9H-purin-9-yl)-8-azaspiro[5.6]dodec-10-en-1-ol Dihydrochloride. Molbank 2022, 2022, M1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morten, M.; Frederik, D. Recent Fascinating Aspects of the CuAAC Click Reaction. Trends in Chemistry 2020, 2, 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osolodkin, D.I.; Kozlovskaya, L.I.; Iusupov, I.R.; Kurkin, A.V.; Shustova, E.Y.; Orlov, A.A.; Khvatov, E.V.; Mutnykh, E.S.; Kurashova, S.S.; Vetrova, A.N.; Yatsenko, D.O.; Goryashchenko, A.S.; Ivanov, V.N.; Lukyanenko, E.R.; Karpova, E.V.; Stepanova, D.A.; Volok, S.; Sotskova, E.; Tamara, K.; Dzagurova, G.; Karganova, G.; Alexander, N.; Lukashev, V.P.; Ishmukhametov, A.A. Phenotypic assessment of antiviral activity for spiro-annulated oxepanes and azepenes. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2024, 103, e14553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).