1. Introduction

Since cartilage and subchondral bone have different biological properties, treating osteochondral defects remains a significant challenge [

1]. The osteochondral interface is particularly difficult to regenerate due to its limited regenerative capacity and complex, stratified architecture [

2]. The osteochondral unit is a unique tissue that includes bone, cartilage, and transitional layers, each with gradated mechanical and biological properties [

3]. The fabrication of new implants that guide osteochondral tissue regeneration, with properties and functions that gradually change to match the injured tissue, remains a major issue.

Additive manufacturing, particularly 3D printing, has gained significant interest in recent decades as a fabrication platform for implants [

4]. This technology involves depositing materials layer by layer with high precision using computer-aided controls, resulting in 3D geometries with the desired spatial arrangement [

5]. However, currently produced 3D-printed implants are still unable to closely mimic the native tissue, especially the biological properties of osteochondral tissue [

6]. Furthermore, implants must often achieve a predefined shape to allow for delivery via minimally invasive methods.

4D printing offers the potential to meet these requirements. 4D printing combines 3D printing with the fourth dimension—time [

7]. Smart materials and designs are central to this technology, which requires materials capable of expanding, flexing, and/or deforming in response to specific stimuli. Shape memory polymers (SMPs) are a type of smart polymer that can change shape when exposed to external stimuli, such as temperature. SMPs can deform under stimuli and recover their original shape, making them highly suited for osteochondral regeneration [

8]. SMPs used in biomedical applications must meet several critical criteria, including biocompatibility, sterilizability, ease of processing, and excellent mechanical properties. Additionally, their switching temperature should be close to or slightly above body temperature. Thermoplastic, bioresorbable shape memory polymers are particularly promising for such applications. These materials, processed through 3D printing, can be used to create self-expanding stents, self-clamping devices, loops, and scaffolds for treating large bone defects [

9]. Their use has the potential to introduce or enhance numerous innovative surgical techniques.

Polyglycolide and its copolymers with lactide and caprolactone are increasingly used in medical applications due to their biocompatibility and favorable mechanical properties [

10]. These materials are characterized by safe biodegradation products, commercial availability, degradability in physiological environments, and the ability to support healing [

11]. It is advantageous to combine polymers with other biomaterials that exhibit similar crystal structures and chemical properties to the inorganic components of bone tissue, such as materials based on tricalcium phosphate (TCP) [

12,

13]. β-TCP is widely recognized in reconstructive surgeries for its osteoconductive and osteoinductive properties, which facilitate bone regeneration. However, its bioresorbability is relatively limited compared to other materials, solidifying its role as a key substance in bone tissue engineering [

14,

15]. While various stimuli-responsive microstructures have been developed, the field of 4D printing remains in its early stages, requiring substantial advancements in material innovation.

The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of β-TCP modification on the structural, mechanical, thermal, and functional properties of a shape-memory terpolymer. The research focused on evaluating the integration and distribution of β-TCP within the polymer matrix, its effect on the material’s crystallinity, thermal stability, and shape-memory behavior, as well as its suitability for various processing methods such as injection molding and 3D printing. Ultimately, the study aimed to assess the potential of this modified terpolymer for advanced applications in 4D printing and the development of medical implants with enhanced functionality and biocompatibility.

2. Materials and Methods

A segmental terpolymer consisting of L-lactide, ε-caprolactone, and glycolide (L-LA/GL/ε-CL 69/16/15) was prepared through ring-opening polymerization at the Centre for Polymer Materials of the Polish Academy of Sciences, using zirconium acetylacetonate as a biocompatible initiator [

16,

17]. The terpolymer was mechanically mixed with 0.5% wt. β-tri-Calcium phosphate particles (β-TCP, Merc, Poland) and homogenized at 190°C. The blending process was carried out by rolling alloys of the plastic material, from which discs with diameters of 0.6 cm and 1.2 cm were cut, corresponding to the well diameters of the cell culture plate. The remaining blend was then processed into granules for the injection molding process. For comparison, pure terpolymer samples in the form of discs (BL) were also prepared. Injection molding was performed using a Babyplast 6/10P machine (Rambaldi, Molteno, Italy). The terpolymer was fabricated in the form of filament sticks using a custom-designed mold previously described [

18]. Additionally, tensile test specimens were produced using a mold designed for manufacturing dog-bone-shaped samples. The injection molding parameters for both dog-bone-shaped samples and filament sticks are presented in

Table 1.

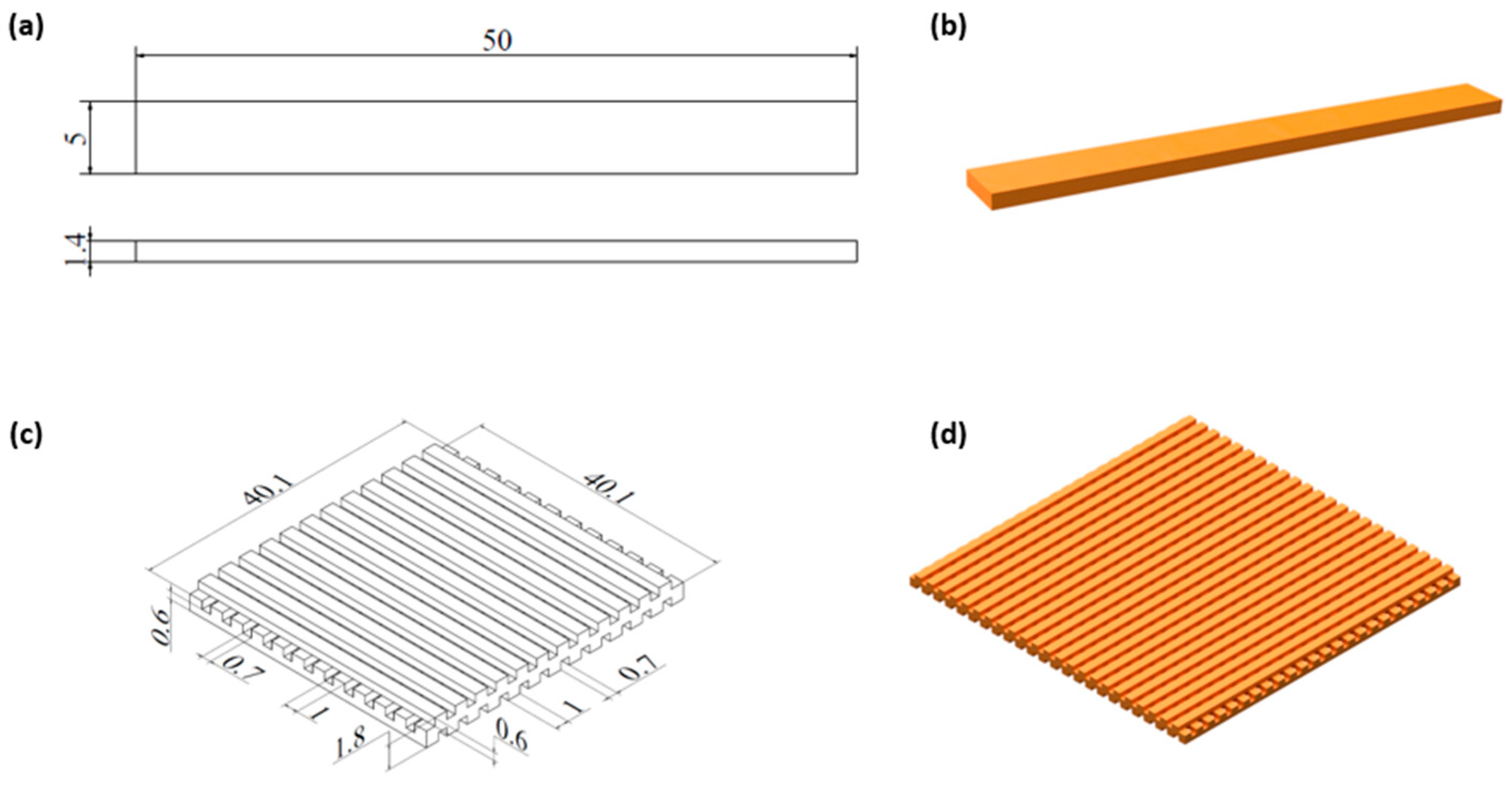

Computer-aided design (CAD) software (Autodesk Inventor Professional, 2023, Autodesk, Inc., San Rafael, CA, USA) was used to design 3D samples in the cuboid shape (

Figure 1a, 1b) and lattice structure. The model of a lattice consisted of three layers made of bars with a rectangular cross-section (1 x 0.6 mm) spaced 0.7 mm apart, adjacent layers were perpendicular to each other. The obtained lattice structure is characterized by cuboid-shaped pores (

Figure 1c, 1d). Filament in a form of sticks with a diameter of 1,75 mm was extruded at 150 °C with a commercial 3D printer (Prusa i3 MK3S+, Czech Republic) in the FFF/FDM technology. The print bed temperature was set to 40 °C, cooling was turned on, nozzle diameter was 0.8 mm, layer thickness was 0.3 mm and the infill was 100%.

The mechanical properties of the pure terpolymer were determined through tensile testing and ultrasonic testing on dog-bone-shaped specimens. Polycaprolactone samples (Mn 80 kDa, Merck, Warszawa, Poland) were used as a reference. Parameters of injection molding are presented in

Table 1. Ultrasonic testing of pure terpolymer samples was conducted using a CT-3 materials tester (Unipan-Ultrasonics, Warsaw, Poland). Longitudinal wave velocities were determined using the through-transmission method with 1 MHz transducers and adhesive tape serving as the coupling medium. The average velocities and standard deviations were calculated. Tensile tests were performed on a universal testing machine (Hegewald & Peschke, Nossen, Germany) in accordance with ISO 527-1:2019. Young's modulus was determined within a strain range of 0.05 % to 0.25 % at a testing speed of 1 mm/min, while the crosshead speed was increased to 10 mm/min for the remaining test. Six specimens each approximately 2.08 mm thick and 2.12 mm wide, were analyzed.

Analysis of morphology, structural uniformity, and potential surface defects of the obtained discs, filaments, and scaffolds was performed using an Opta-Tech stereomicroscope (Warszawa, Poland), equipped with a CMOS 3 camera and OptaView 7 software.

The evaluation of the samples microstructure and scaffold architecture were performed using the Apreo 2S low vac high-resolution scanning electron microscope from ThermoFisher Scientific. Prior to imaging, all samples were coated with a thin conducting layer of carbon (10 nm) and observed in low vacuum (50Pa) conditions with LVD and CBS detectors at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV. The pore linear dimension of scaffolds were calculated from SEM pictures by the Image Line measurement program. The elemental content of active modifiers incorporated in sticks and blends was examined using EDAX Octane Elite energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDS/EDX) system with Octane Elite silicon drift detectors (SDDs) operated with APEX™ software). The qualitative analysis was performed using a standardless method.

ATR-FTIR spectra were obtained over a wavenumber range of 350–4000 cm⁻¹ using a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS5 FT-IR Spectrometer, equipped with an iD7 ATR module and a diamond crystal for Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR). The spectra were recorded with 32 scans at a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹.

Calorimetric (DSC) measurements were carried out with an analytical system (TA Instruments, USA) equipped with a MDSC Calorimeter 2920 and refrigerated cooling system. The samples were heated at the rate of 20 °C/min from -30 °C to about 180 °C and in selected cases up to 225 °C followed by cooling at the same rate. The experiments were performed under a nitrogen atmosphere (purge flow rate: 40 cm³/min) using standard aluminum pans. The weight of the examined samples was about 5 mg. Registration sensitivity was 0.2 μW. Analysis of the DSC curves, including the determination of enthalpies and characteristic transition temperatures, was carried out using the Universal V4.5A software provided by TA Instruments.

Thermogravimetric (TGA) investigations were performed using TA Instruments Q500 Thermogravimetric Analyzer. Measurements were done in a temperature range from 30 to 650°C with the heating rate of 20 °/min under nitrogen atmosphere (flow 60 ml/min). TGA data were also analyzed using TA Universal V4.5 software.

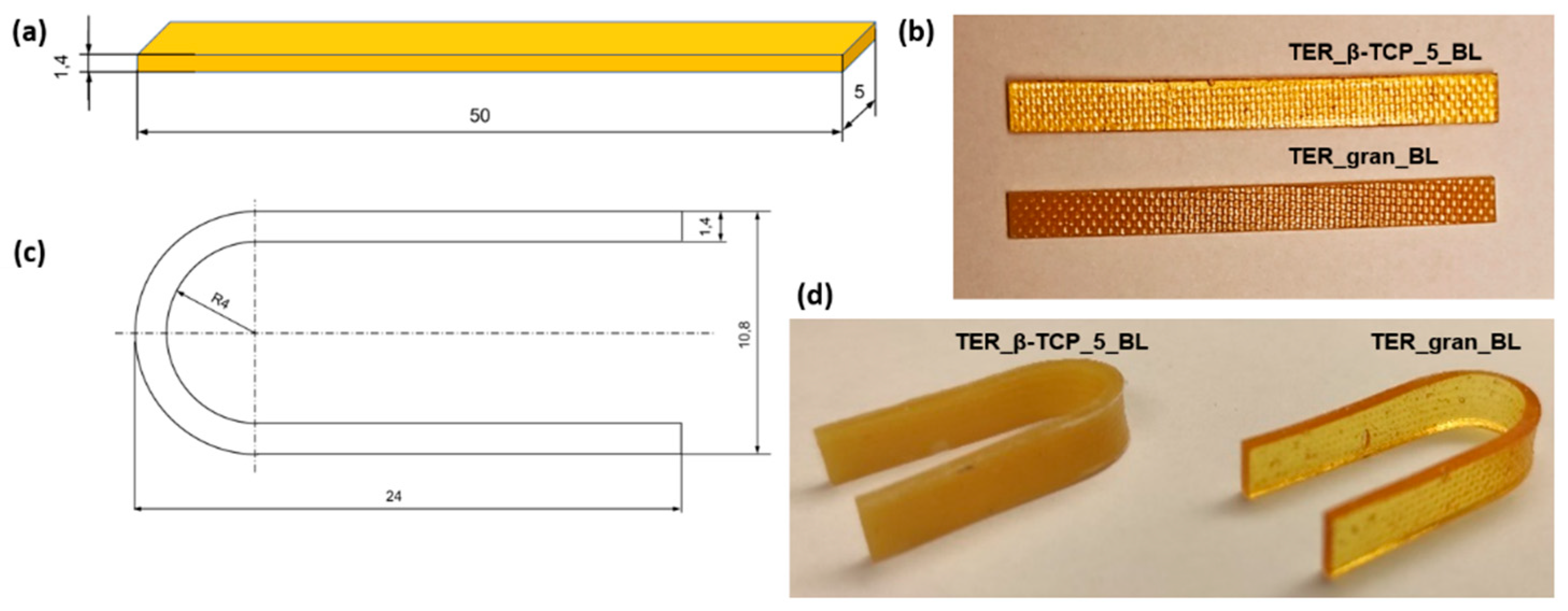

To study shape memory, samples with dimensions of 50 x 5x 1.4 mm (original shape shown in

Figure 2a, 2b) were prepared. Plates with a thickness of 1.4 ± 0.1 mm were produced by rolling alloys of the investigated materials, and the samples were subsequently cut using a mechanical press. The samples were shaped into a temporary "U" shape (

Figure 2c, 2d) in distilled water at a temperature of 45°C and then cooled in water at 10°C for 20 minutes. Prior to testing, the samples were stored at room temperature of approximately 20°C.

The shape memory test (ability to return to the original shape) was conducted by observing and recording a video of the deformation process of the samples after immersion in distilled water at a temperature of 37 ± 0.3°C. The tests were performed on 5 samples made from the base material TER_GRAN_BL and 5 samples made from the β-TCP modified material (TER_BTCP_5_BL).

2.1. Cell Culture Studies

2.1.1. Cultivation of Saos-2

Saos-2 cells were maintained in McCoy's 5A medium supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. When the cells reached approximately 80% confluence, they were passaged. The culture medium was removed, and the cells were washed twice with 15-20 ml of 10% PBS. Trypsin/EDTA solution was then added, and the flask was incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 2-3 minutes until the cells detached. Following detachment, fresh culture medium containing serum was added to inhibit trypsin activity. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 3 minutes at room temperature. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of fresh medium. The suspension was either transferred to new culture flasks or counted and plated for further culture.

2.1.2. Sterilization of Materials

The materials used in the tests underwent sterilization by being immersed in 70% ethanol for 24 hours, followed by UV irradiation for 20 minutes on both sides.

2.1.3. MTT Assay

Experiments were performed using both unmodified terpolymer and terpolymer modified with β-TCP. The materials in the form of discs were placed in 96-well plates, and a cell suspension (1×10⁴ cells/ml, 0.2 ml per well) was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 1 day, 1 week, 2 weeks, and 3 weeks at 37°C in 5% CO2. After the incubation period, the medium was removed, and each well was rinsed with 10% PBS. An MTT solution (serum-free culture medium:MTT, 10:1) was then added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 3 hours at 37°C in 5% CO2. Following incubation, the medium was discarded, and DMSO with NH3 was added to each well. The DMSO-NH3 mixture was transferred to a new plate, and the absorbance was measured at 550 nm.

2.1.4. Determination of Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP)

Saos-2 cells were seeded onto the tested materials in 24-well culture plates at a concentration of 2 × 10⁴ cells/mL and incubated for 24 and 72 hours. After incubation, the cells were lysed in PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 (PBS-T), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity was assessed by measuring the conversion of colorless p-nitrophenol phosphate to yellow p-nitrophenol at alkaline pH. The production of p-nitrophenol was monitored spectrophotometrically at 405 nm and quantified by comparison with a standard curve using p-nitrophenol dissolved in PBS-T. ALP levels were normalized to protein content, which was determined using the Bradford method with bovine serum albumin as the standard [

19].

2.1.5. Fluorescence Staining

The materials were sterilized and placed into a 24-well plate, where Saos-2 cells were seeded at a final concentration of 1 × 10⁵ cells/mL (0.8 mL per well). After 24 hours, 1 week, or 3 weeks, the medium was removed, and the cells were washed with PBS. The cells were then stained with 0.01% acridine orange (0.3 mL per well) for 1 minute in the dark. Following this, the cells were washed 10 to 20 times with PBS. Finally, the materials were transferred to microscope slides and examined using a fluorescence microscope.

2.1.6. Statistical Analysis

Cell viability results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8. The t-test was employed to compare the viability of cells on modified materials with that on TER_gran_BL. Comparisons were made between samples with the same incubation time. A p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

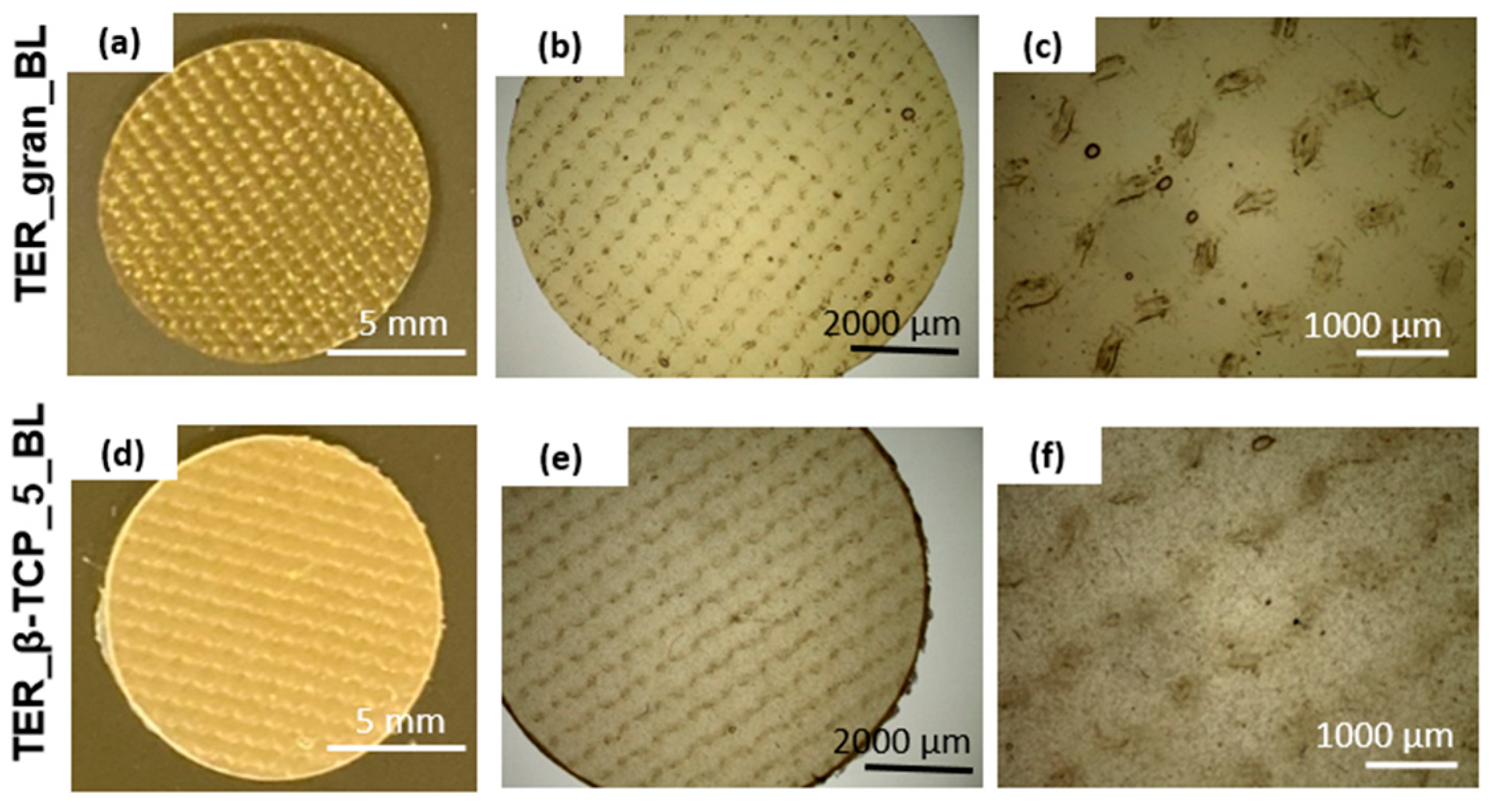

To evaluate the architectural design of the terpolymer blends, samples (discs) were analyzed using stereoscopic microscopy at varying magnifications (

Figure 3). These images revealed the detailed surface texture resulting from the manufacturing process. In samples modified with β-TCP, distinct powder-derived inclusions were observed. These inclusions were uniformly distributed across the surface, highlighting the effective integration of β-TCP into the matrix.

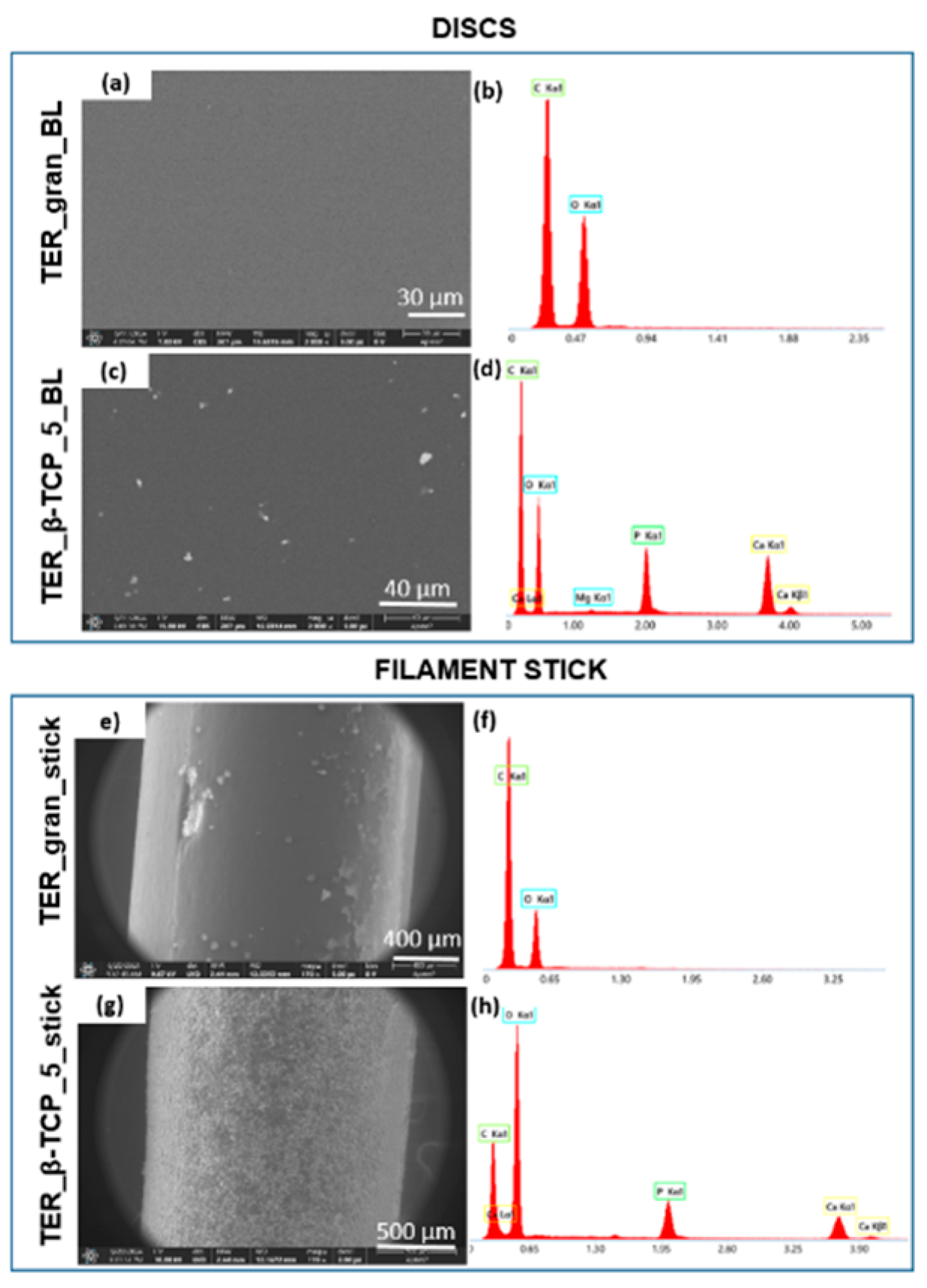

Scanning Electron Microscopy provided additional details about the surface characteristics (

Figure 4). While pure terpolymer samples exhibited a smooth and homogeneous surface, the β-TCP-modified samples displayed visible agglomerates, confirming the presence of the additive in the matrix. The distribution of these agglomerates indicated successful blending and dispersion of β-TCP within the polymer.

EDS method was used to verify the chemical composition of the samples. This analysis confirmed the incorporation of β-TCP into the polymer matrix, as evidenced by the presence of chemical elements associated with the additives such as calcium and phosphorus. The modified material was also examined in different forms, including filaments and scaffolds produced using injection molding and 3D printing techniques.

Microscopic studies indicate that filament sticks and 3D scaffolds were successfully fabricated. The shape of the mold was accurately reproduced, resulting in high-quality sticks (

Figure 5). Microscopic analysis confirmed that both types of printed scaffolds exhibited a highly porous microstructure with interconnected pores (

Figure 6). The results consistently demonstrated the successful incorporation and uniform distribution of β-TCP powder within the filament sticks and resulting scaffolds. The SEM images of the terpolymer scaffold modified with β-TCP (

Figure 7) reveal numerous agglomerates of the powder dispersed within the structure, suggesting partial inhomogeneity of the modifier distribution. The lattice model, consisting of three layers of bars, is visible in the SEM micrographs. The obtained lattice structure is characterized by cuboid-shaped pores, which align with the intended geometric design of the scaffold. The 3D printing process, ensured a highly interconnected pore network.

Table 2 presents the mechanical properties of the pure terpolymer in comparison with polycaprolactone, another polymer frequently used in our group to produce filaments for 3D printing [

17]. These parameters include tensile strength, Young's modulus, strain at break, and longitudinal wave velocity, with values given as mean ± standard deviation. The measured mechanical properties show that the terpolymer is characterized by relatively high tensile strength and Young's modulus compared to polycaprolactone. The terpolymer shows more limited elongation, while polycaprolactone exhibits a much higher strain at break, proving it is more flexible and capable of undergoing larger deformations before fracture. The terpolymer specimens exhibited a 13 % higher wave velocity compared to the PCL samples, which directly translates into Young's modulus, as confirmed by the data from the tensile testing machine.

The infrared spectrum (

Figure 8a and

Figure 8b) reveals characteristic bands indicative of specific functional groups in the monomers. Vibrations related to the C-H stretching in CH and CH₃ groups appear at 2995 cm⁻¹ and 2945 cm⁻¹, respectively. A band at 1745 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the carbonyl (C=O) stretching in ester bonds, which is a characteristic property of L-lactide, glycolide, and caprolactone monomers. The bending vibrations of C-H in -CH₂ groups, mainly from caprolactone and partly from glycolide segments, are detected at 1452 cm⁻¹ and 1425 cm⁻¹. Similarly, the C-H bending vibrations of -CH₃ groups, specific to L-lactide, manifest at 1382 cm⁻¹ and 1364 cm⁻¹. The stretching of C-O and C-O-C bonds in ester linkages is marked by a prominent band at 1180 cm⁻¹, a defining trait of the terpolymer structure. Additional bands, located at 1128 cm⁻¹, 1084 cm⁻¹, and 1044 cm⁻¹, are associated with C-O and C-O-C stretching vibrations within ester bonds of caprolactone. These bands confirm the incorporation of functional groups derived from all three monomers in the terpolymer [

20,

21]. β-TCP exhibits characteristic bands at 1003 cm⁻¹ and 1116 cm⁻¹ corresponds to the asymmetric P–O stretching vibrations. The symmetric stretching vibration of the P–O group can be observed at 968 cm⁻¹ and 942 cm⁻¹. The bands around 602 cm⁻¹ and 540 cm⁻¹ are associated with bending vibrations of phosphate groups.

We have observed the absence of peaks at 602 cm⁻¹ and 540 cm⁻¹, which are typically associated with β-TCP (biological tricalcium phosphate). Probably, when terpolymer and β-TCP exhibited absorption features in the same spectral region, their overlapping vibrational modes resulted in the attenuation of individual peak intensities. This interaction led to the merging of distinct peaks into a broader, more diffuse band. Consequently, the FTIR spectrum of both modified discs and scaffolds appeared less resolved, with a more continuous or flattened profile in regions where characteristic β-TCP peaks would typically have been observed. The lack of appearance of these bands in β-TCP modified terpolymer indicates that β-TCP is effectively incorporated into the polymer, confirming successful modification.

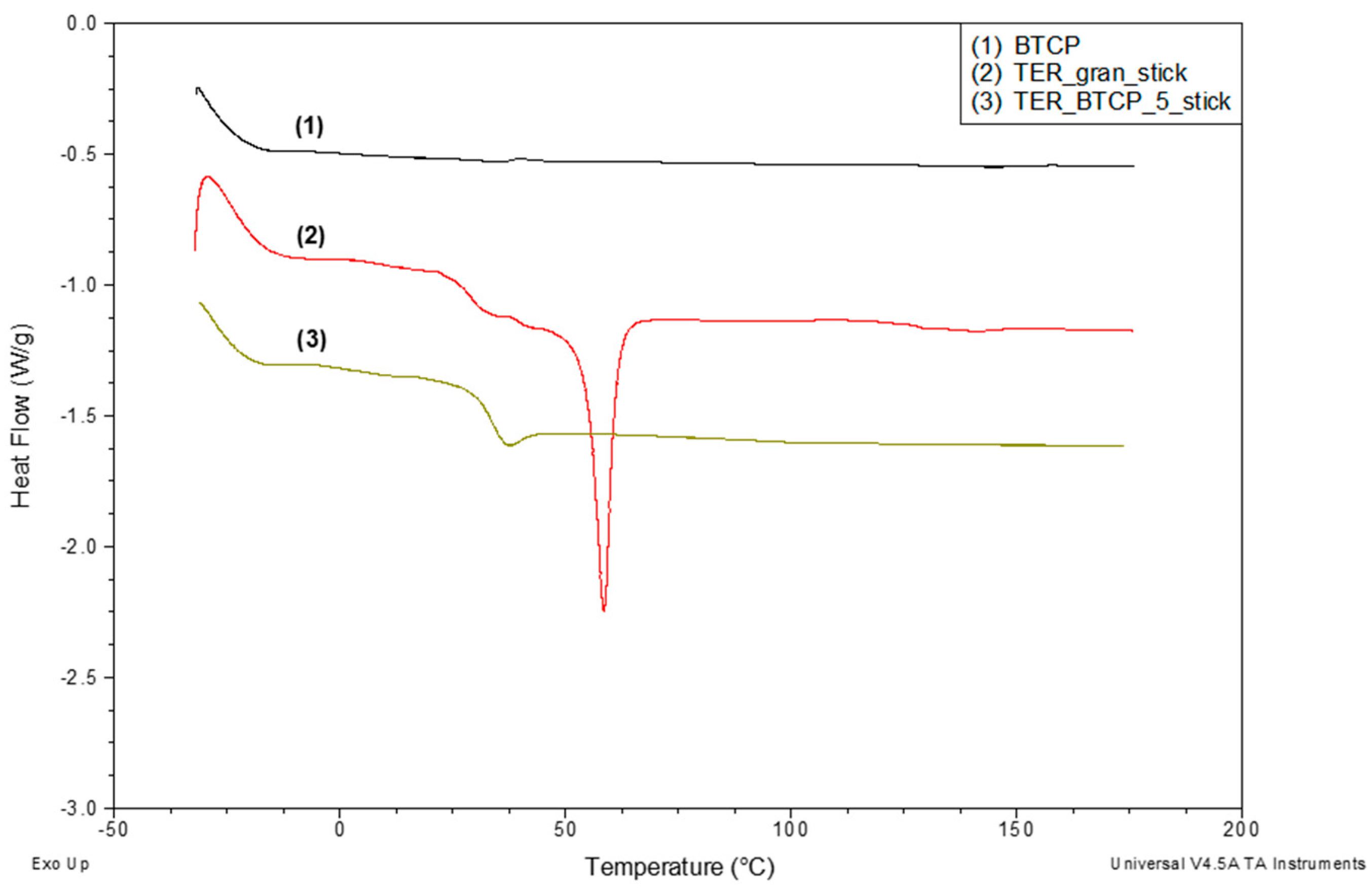

Figure 9 presents the DSC curves recorded for three materials: the base terpolymer with shape memory (curve 2), the terpolymer modified with 5% β-TCP (curve 3), and the pure modifier β-TCP (curve 1). The DSC curve for the pure terpolymer (30–180 °C) demonstrates its semicrystalline structure, as evidenced by a glass transition (characteristic shift) and a distinct melting peak.

Upon incorporating 5% β-TCP into the terpolymer, the melting peak disappears entirely, indicating the elimination of the crystalline phase in the terpolymer structure. Additionally, the DSC curve for the modified terpolymer shows an endothermic enthalpy relaxation effect (apparent melting) associated with the glass transition.

In contrast, no transitions are observed in the DSC curve for the pure β-TCP modifier within the studied temperature range.

The thermographic characteristics described above remain consistent despite changes in the sample's form.

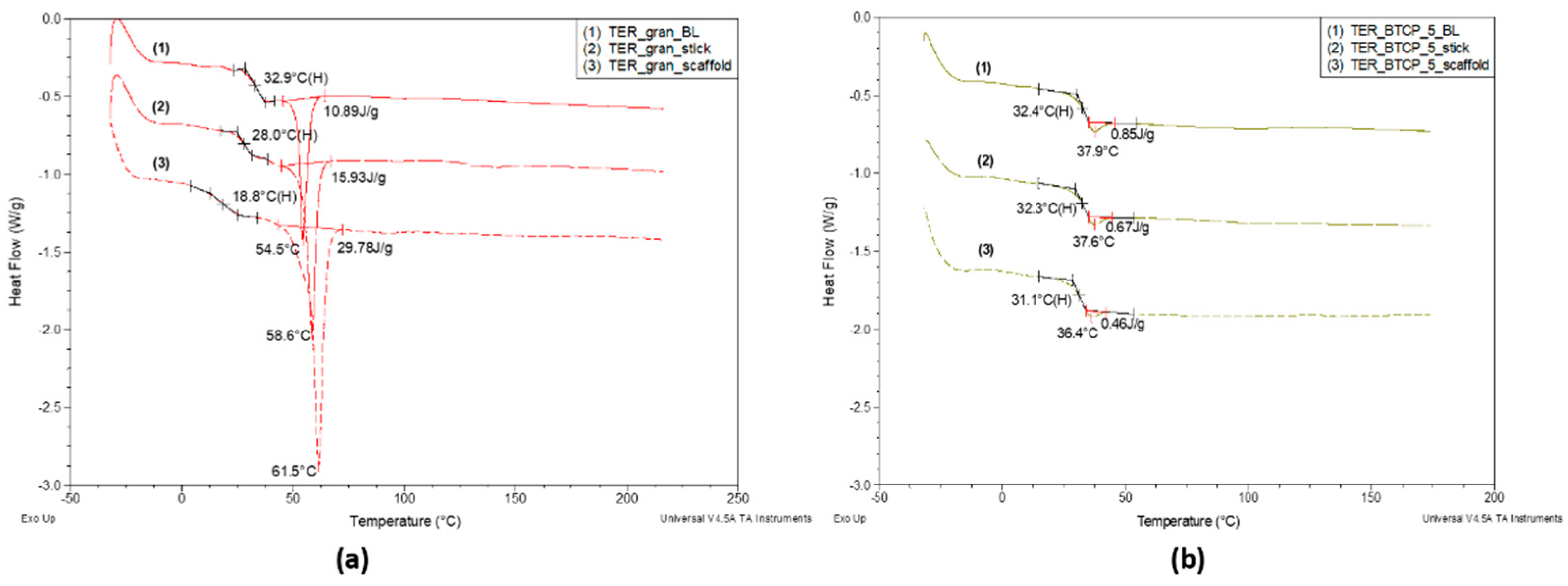

Figure 10 compares the DSC curves for the pure terpolymer (10a) and the terpolymer with 5% β-TCP (10b) in three forms: discs (BL), injection-molded sticks, and 3D-printed scaffolds.

For the pure terpolymer, the glass transition temperature (Tg) decreases significantly and monotonically: from 32.9 °C for the disc, to 28.0 °C for the filament, and further to 18.8 °C for the scaffold. This is accompanied by a progressive increase in the melting peak minimum temperature—indicative of larger average crystallite sizes—from 54.5 °C (melt) to 58.6 °C (filament) and 61.5 °C (scaffold).

Additionally, the melting enthalpy (ΔHm) increases in the same order: from 10.89 J/g for the disc, to 15.93 J/g for the filament, and finally to 29.78 J/g for the scaffold.

For the terpolymer modified with 5% β-TCP (

Figure 10b), the trends in the glass transition temperature (Tg) across different processing forms are maintained but are significantly less pronounced. The Tg differences between the processing forms amount to just over 1 °C, a stark contrast to the unmodified terpolymer, where ΔTg reached 14.1 °C. Similarly, the difference in the minimum temperature of the enthalpy relaxation peak is only 1.5 °C. However, the enthalpy of apparent melting changes by as much as 46%. This indicates that the addition of β-TCP strongly influences the physical structure of the terpolymer, effectively inhibiting crystallization. The impact of β-TCP on the formation of the amorphous phase is minimal, as evidenced by the negligible shift in Tg (0.5 °C) for TER_gran_BL and TER_β-TCP_5_BL discs samples, even in the presence of the enthalpy relaxation effect. Moreover, the modifier significantly reduces the sensitivity of the material to structural changes induced by processing techniques. This is particularly evident in the nearly threefold increase in the melting enthalpy of the unmodified scaffold sample (29.78 J/g) compared to the unmodified disc sample (10.89 J/g). This observed regularity may be attributed to the orientation phenomena occurring during filament formation and, especially, scaffold printing. The validity of this hypothesis is supported by DSC curve analyses performed on specific samples over two consecutive heating cycles.

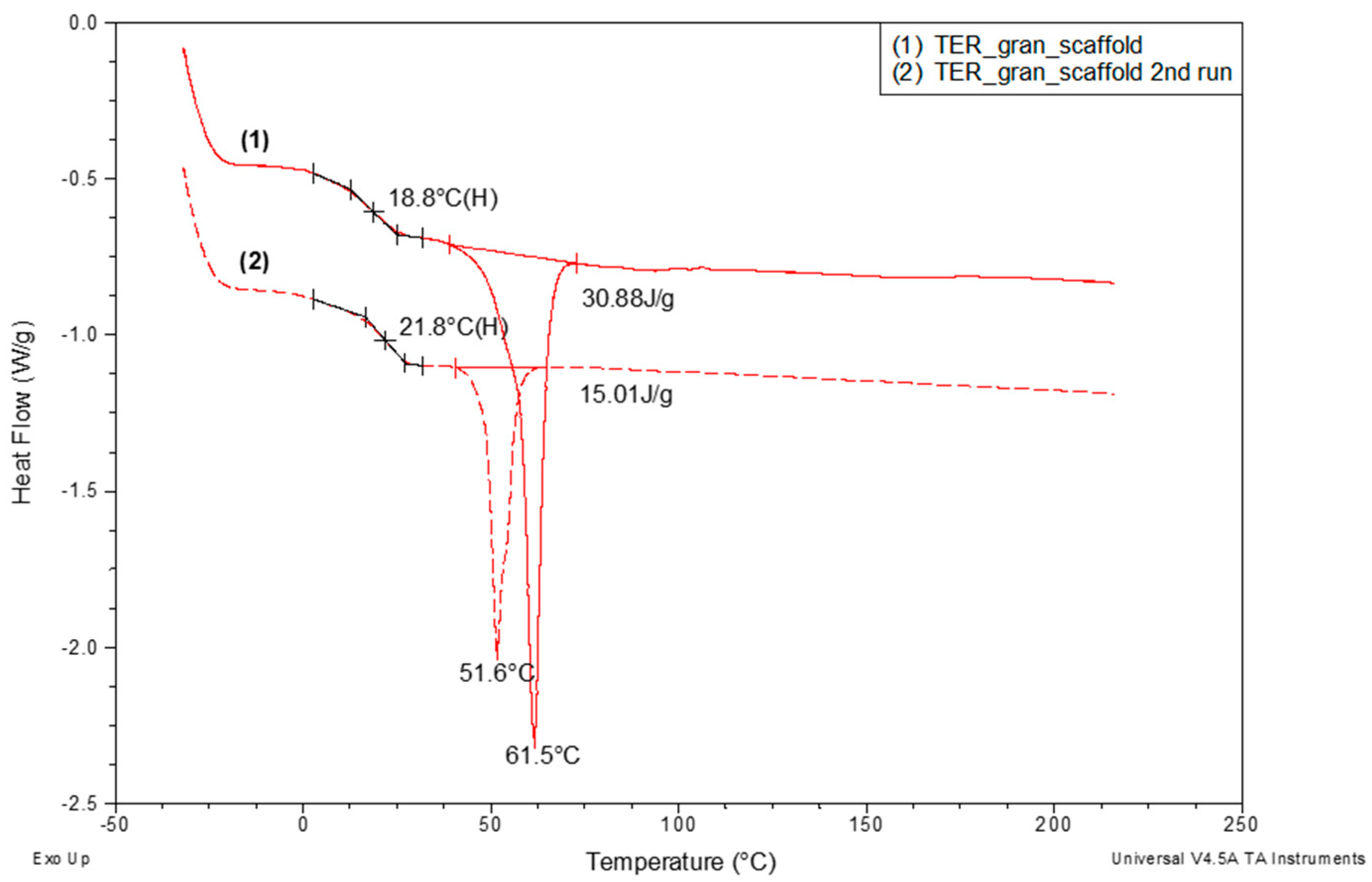

Figure 11 presents an example of DSC curves recorded during the heating of the TER_gran_scaffold sample. The results reveal that the melting enthalpy (ΔHm) of the crystalline phase in the scaffold—whose structure is significantly influenced by orientation during the printing process—is more than twice as high (30.88 J/g) as that of the same material after melting and subsequent cooling (15.01 J/g). This increase is accompanied by a notable rise of nearly 10 °C in the melting peak minimum temperature, which correlates with an increase in the mean crystallite size within the scaffold. Additionally, a threefold increase in the recorded glass transition temperature was observed during reheating for this sample.

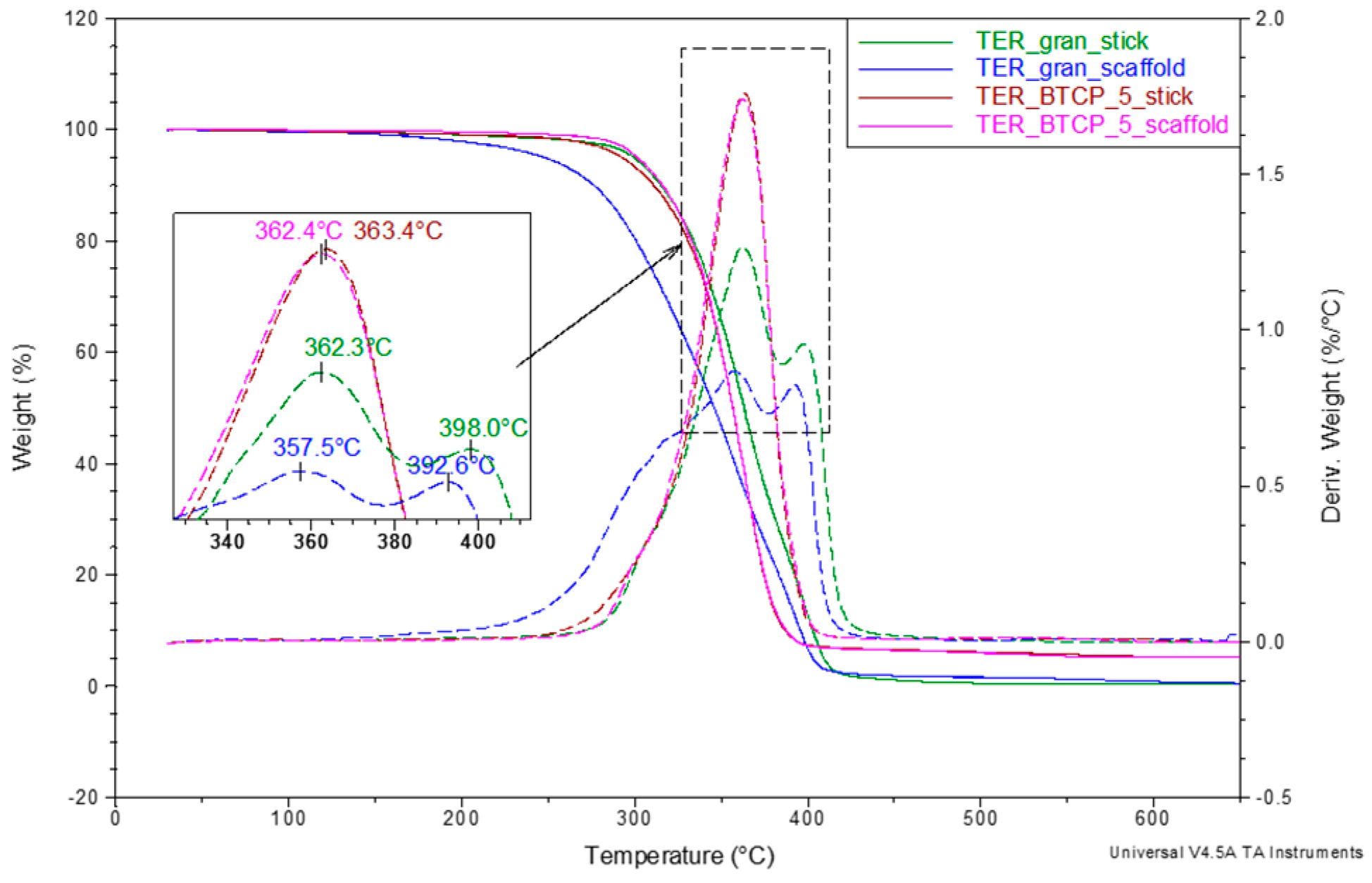

The final stage of the thermal analysis involved thermogravimetric studies aimed at evaluating the effect of β-TCP on the thermal stability of the shape memory terpolymer discussed in this paper. Measurements were performed over a wide temperature range (30 to 650 °C) in an inert atmosphere. The results, presented as TG and DTG curves in

Figure 12, reveal significant differences in the thermal decomposition behavior of the samples. For samples containing the β-TCP modifier, decomposition is single-stage, with the maximum weight loss rate observed at approximately 363 °C. Compared to the unmodified samples, decomposition occurs more dynamically and ends 20–30 °C earlier. In contrast, the unmodified terpolymer undergoes at least two-step decomposition, with an additional shoulder observed on the DTG curve for the TER_β-TCP_5_scaffold sample. Notably, the onset of decomposition for this sample is approximately 80 °C lower than that of the scaffold produced from the modified terpolymer.

This discrepancy suggests that the unmodified terpolymer, subjected to successive technological operations (melting, filament formation, and printing) and corresponding thermal loads, undergoes limited depolymerization. This results in shortened macromolecular chains, which alter its supramolecular structure (as shown in

Figure 10) and lower the decomposition onset temperature. The addition of β-TCP appears to effectively inhibit this depolymerization process. However, confirming this hypothesis would require further studies of changes in the average molecular weight.

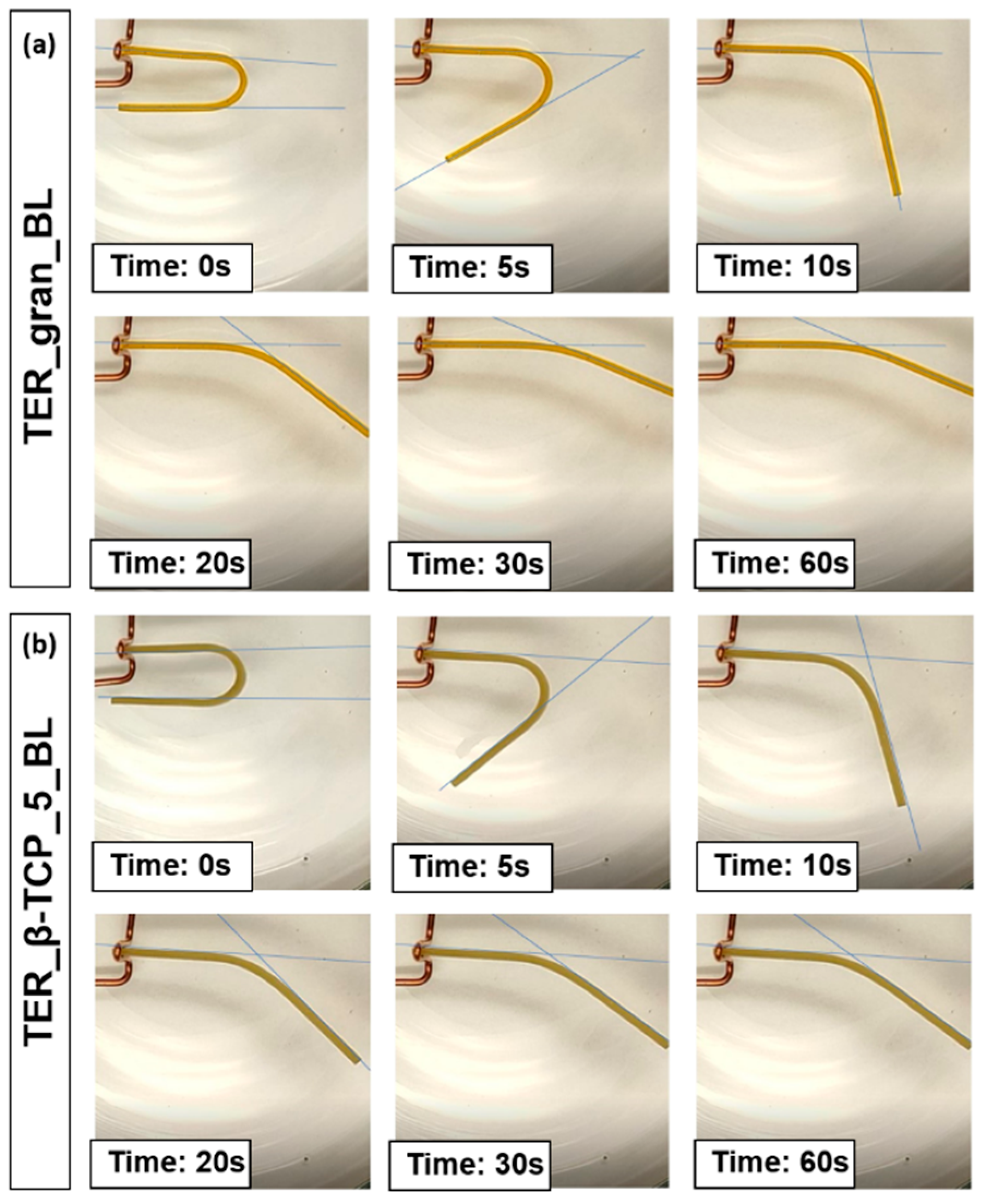

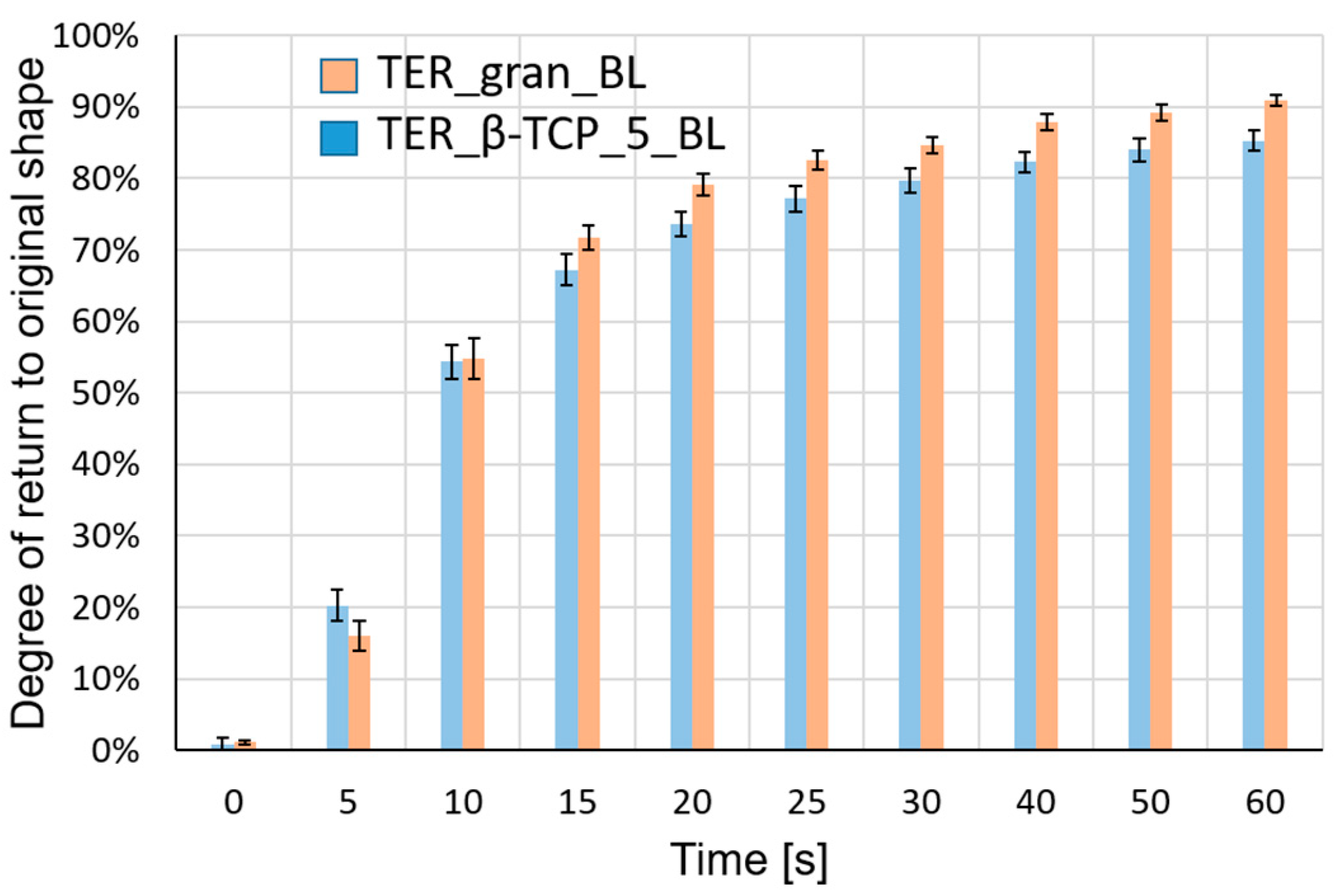

The recorded process of sample deformation was subjected to frame-by-frame analysis. Based on observations of the phenomenon, it was determined that deformation readings of the sample would be taken at specific time intervals: t = 0 (immediately after immersing the sample in water), followed by t = 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, and 60 seconds. The indicator used to assess the sample's ability to return to its original shape was the change in the sample's bending angle relative to its initial bending angle, expressed as a percentage.

Figure 13 present the results of the frame-by-frame analysis of selected samples at specific time intervals.

Figure 14 show a summary of the results of the measurements of the samples' ability to return to their original shape.

3.1. Cell Culture Results

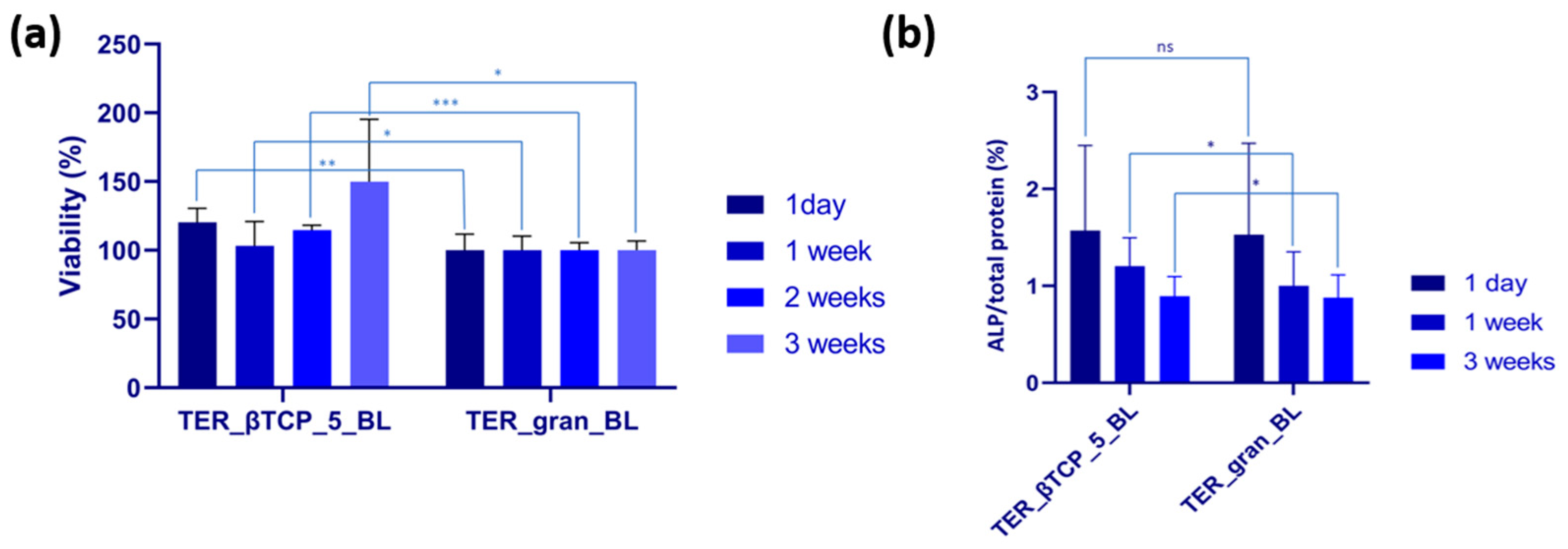

Saos-2 cells were incubated with modified materials for 1 day, 1 week, 2 weeks, and 3 weeks at 37˚C, 5% CO2. The material modified with β-tricalcium phosphate (TER_βTCP_5_BL) was compared to the plain material (TER_gran_BL), which served as the control. Cells in contact with TER_βTCP_5_BL exhibited higher viability than those cultivated on TER_gran_BL throughout the incubation period, with significance at p < 0.01 for 1 day, p < 0.05 for 1 week, p < 0.001 for 2 weeks, and p < 0.05 for 3 weeks (

Figure 15a). The highest viability was observed after 3 weeks of incubation (149.82%). ALP, a key enzyme involved in mineralization and bone development, was evaluated in osteoblast-like cells (Saos-2) cultivated on the samples for periods ranging from 1 day to 3 weeks. After 1 day of incubation, no significant differences in ALP activity were observed (

Figure 15b). However, after 1 week and 3 weeks, cells grown on TER_βTCP_5_PL exhibited higher ALP activity compared to those on TER_gran_BL.

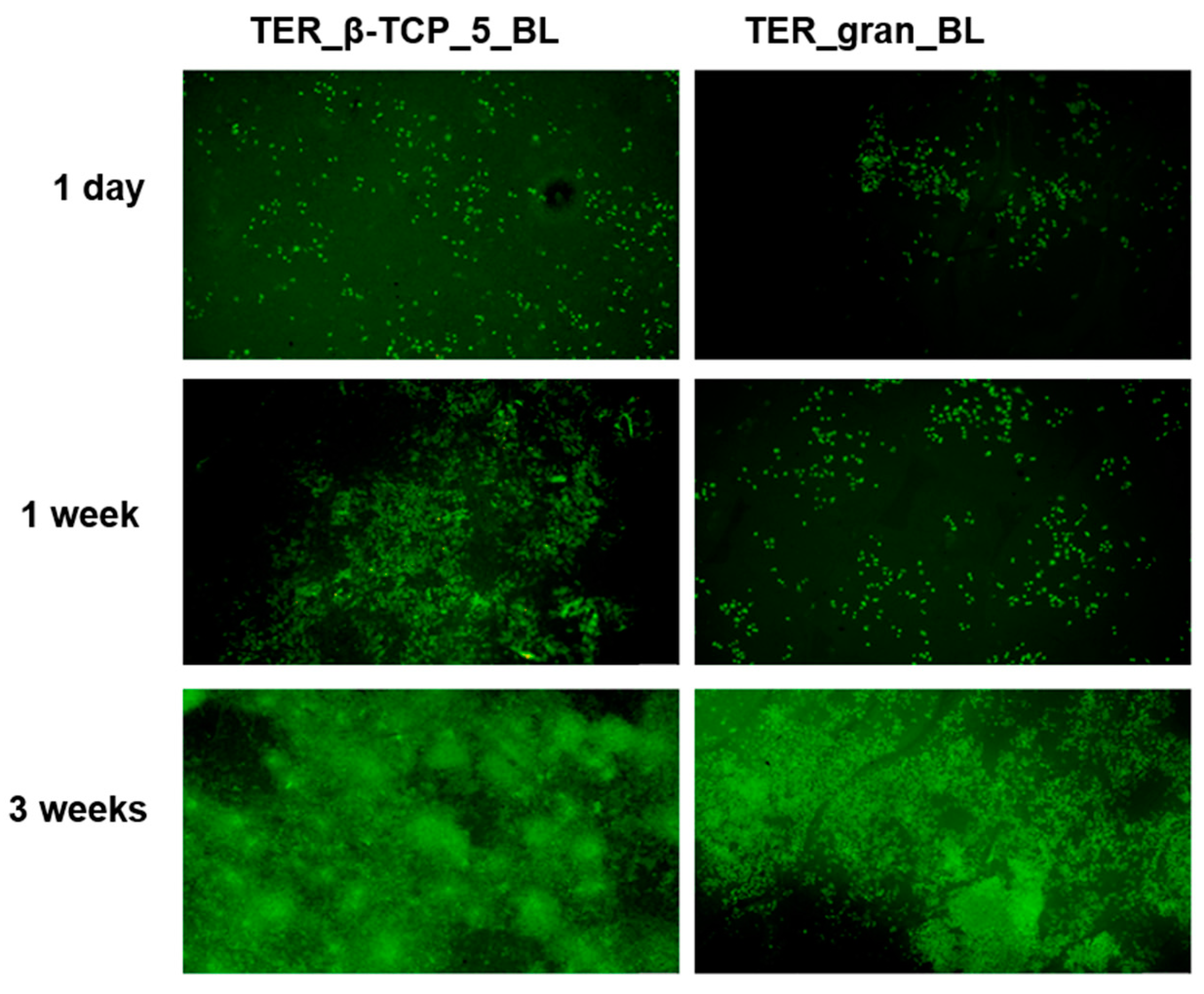

Figure 16 shows representative fluorescence microscopy images of cells cultured on the materials after 1 day, 1 week, and 3 weeks. A time-dependent increase in the number of living cells (stained green) was observed on both TER_βTCP_5_BL and TER_gran_BL.

4. Discussion

Polyglycolide (PGA) copolymers with poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) or polylactide (PLA) have gained considerable attention in biomedical applications due to their tunable mechanical properties, which can be adjusted by varying the monomer composition [

22]. Extensive research has focused on the synthesis and development of terpolymers for medical applications [

23]. In our study, we utilized a terpolymer composition of L-lactide/glycolide/ε-caprolactone (69/16/15), further modified with β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) to enhance its bioactivity. β-TCP incorporation improves cell adhesion, proliferation, and osteogenic differentiation, making it a promising modifier for biomedical materials [

13].

The developed composite material, based on a shape-memory polymer (SMP) matrix with β-TCP, was designed to maintain shape-memory effects and self-deformation properties suitable for 4D printing applications. The composite exhibited excellent processability with a 3D printer, biocompatibility, and biodegradability. Additionally, the shape-memory performance of the terpolymer was remarkable, achieving a shape recovery ratio exceeding 80% at body temperature. The pure terpolymer samples demonstrated slightly higher recovery rates (~90%) compared to β-TCP-modified samples (~80%), after 1 min, confirming the influence of the modifier on the shape-memory properties.

Microscopic and spectroscopic analyses validated the successful integration of β-TCP within the terpolymer matrix. SEM and EDS analyses showed evenly distributed β-TCP inclusions, with minor agglomeration in scaffold samples. FTIR spectroscopy further confirmed the effective chemical integration of β-TCP into the polymer. Calorimetric studies using DSC revealed that β-TCP and the processing methods significantly affected the nanostructure, influencing both crystalline and amorphous phases. TGA analysis highlighted a potential risk of limited depolymerization under thermal loads; however, the β-TCP modifier mitigated this risk by promoting crystallization stability. Biological evaluations reinforced the benefits of β-TCP modification. MTT assay results showed significantly enhanced Saos-2 cell viability on β-TCP-modified materials (TER_βTCP_5_BL) compared to the control terpolymer (TER_gran_BL). This effect was most pronounced after two weeks, indicating that β-TCP supports cell proliferation. Fluorescence microscopy demonstrated a time-dependent increase in viable cell density, with β-TCP-modified materials consistently outperforming the control. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity, a critical marker for mineralization and bone development, was significantly elevated in β-TCP-modified samples after one and three weeks of incubation, underscoring the osteogenic potential of the material. These findings align with previous studies, such as those by Lu et al., which highlight the benefits of β-TCP in scaffolds for promoting osteogenic differentiation and bone tissue regeneration [

24]. The combination of enhanced bioactivity, shape-memory functionality, and 4D printability positions the developed terpolymer composite as a promising candidate for medical implants and bone-related applications.

5. Conclusions

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) modification on the structural, mechanical, thermal, and functional properties of a shape-memory terpolymer, with a focus on its potential application in 4D printing technology and medical implant production. The integration of β-TCP into the filament matrix and scaffolds was confirmed through microscopic (SEM, stereoscopic) and spectroscopic (FTIR, EDS) analyses. FTIR spectra indicated successful incorporation of β-TCP into the polymer. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis revealed a shift toward a more amorphous structure following β-TCP modification, improving processing properties, particularly for 3D printing. Thermal stability was enhanced, as β-TCP delayed depolymerization of the polymer matrix. Shape-memory studies demonstrated effective recovery in both modified and unmodified samples, although β-TCP slightly reduced recovery performance. In vitro cell culture studies showed that β-TCP-modified terpolymer significantly increased cell viability and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity after 3 weeks. The β-TCP-modified terpolymer can be tailored for applications where partial shape recovery is acceptable, such as bone scaffolds or implants designed to promote osteointegration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.R., A.K. J.F2; methodology, I.R, J.J., J.F,; software, A.J., M.M., validation, I.R., J.F2. and J.F.; formal analysis, J.F, I.R., J.F2.; investigation, P.S., M.M., A.K., J.J., J.F, M.Z., W.P., R.N, I.R., J.F2 resources, I.R.; data curation, I.R., J.F., J.F2; writing—original draft preparation, I.R, J.F, J.F2, J.J. A.J; writing—review and editing, I.R., M.Z. J.F2; visualization, I.R, A.J, J.J, J.F., J.F2.; supervision, I.R.; project administration, I.R.; funding acquisition, I.R., J.F.2. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Science Centre, Poland, in the frame of the project “3D and 4D printing of stimuli-responsive and functionally graded biomaterials for osteochondral defects regeneration,” grant number: 2020/39/I/ST5/00569 (OPUS-LAP) and by Grant Agency of the Czech Republic 21-45449L. The cell culture studies were partially supported by internal Grant Agency of the Faculty of Medicine, Palacky University Olomouc (IGA_LF_2024_011). The SEM investigations were partially supported by the program Excellence Initiative - Research University for the AGH University of Krakow, grant ID 1449.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time as the data is also part of an ongoing study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Asensio, G.; Benito-Garzón, L.; Ramírez-Jiménez, R.A.; Guadilla, Y.; Gonzalez-Rubio, J.; Abradelo, C.; Parra, J.; Martín-López, M.R.; Aguilar, M.R.; Vázquez-Lasa, B.; et al. Biomimetic Gradient Scaffolds Containing Hyaluronic Acid and Sr/Zn Folates for Osteochondral Tissue Engineering. Polymers 2022, 14, 12. [CrossRef]

- Rajzer, I.; Menaszek, E.; Bacakova, L.; Orzelski, M.; Błażewicz, M. Hyaluronic acid-coated carbon nonwoven fabrics as potential material for repair of osteochondral defects. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2013, 99, 102–107. Available online: http://www.fibtex.lodz.pl/article937.html.

- Loureiro, J.A.; Pereira, M.C. PLGA based drug carrier and pharmaceutical applications: The most recent advances. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 903. [CrossRef]

- Rajzer, I.; Kurowska, A.; Frankova, J.; Sklenářová, R.; Nikodem, A.; Dziadek, M.; Jabłoński, A.; Janusz, J.; Szczygieł, P.; Ziąbka, M. 3D-Printed Polycaprolactone Implants Modified with Bioglass and Zn-Doped Bioglass. Materials 2023, 16, 1061. [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Nand, A.; Ray, S. Application of Spectroscopy in Additive Manufacturing. Materials 2021, 14, 203. [CrossRef]

- Novotná R., Franková J. Materials suitable for osteochondral regeneration. ACS Ome-ga. 2024, 9, 30097-30108. [CrossRef]

- Demoly, F.; Dunn, M.L.; Wood, K.L, Qi, H.J.; André, J.C. The status, barriers, challenges, and future in design for 4D printing. Materials & Design 2021, 212, 110193. [CrossRef]

- Jolaiy, S.; Yousefi, A.; Hosseini, M.; Zolfagharian, A.; Demoly, F.; Bodaghi, M. Limpet-inspired design and 3D/4D printing of sustainable sandwich panels: Pioneering supreme resiliency, recoverability and repairability. Applied Materials Today 2024, 38, 102243. [CrossRef]

- Doostmohammadi, H.; Kashmarizad, K.; Baniassadi, M.; Bodaghi, M.; Mostafa Baghani, M. 4D printing and optimization of biocompatible poly lactic acid/poly methyl methacrylate blends for enhanced shape memory and mechanical properties. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials 2024, 160, 106719. [CrossRef]

- Skubis-Sikora, A.; Hudecki, A.; Sikora, B.; Wieczorek, P.; Hermyt, M.; Hreczka, M.; Likus, W.; Markowski, J.; Siemianowicz, K.; Kolano-Burian, A.; et al. Toxicological Assessment of Biodegradable Poli-ε-Caprolactone Polymer Composite Materials Containing Hydroxyapatite, Bioglass, and Chitosan as Potential Biomaterials for Bone Regeneration Scaffolds. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1949. [CrossRef]

- Spearman, B.S.; Agrawal, N.K.; Rubiano, A.; Simmons, C.S.; Mobini, S.; Schmidt, C.E. Tunable methacrylated hyaluronic acid-based hydrogels as scaffolds for soft tissue engineering applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2020, 108, 279–291. [CrossRef]

- Rajzer, I.; Rom, M.; Błażewicz, M. Production of carbon fibers modified with ceramic powders for medical applications. Fibers and Polymers 2010, 11(4), 615 – 624. [CrossRef]

- Helaehil, J.V.; Lourenço, C.B.; Huang, B.; Helaehil, L.V.; de Camargo, I.X.; Chiarotto, G.B.; Santamaria-Jr, M.; Bártolo, P.; Caetano, G.F. In Vivo Investigation of Polymer-Ceramic PCL/HA and PCL/β-TCP 3D Composite Scaffolds and Electrical Stimulation for Bone Regeneration. Polymers 2022, 14, 65. [CrossRef]

- Esslinger, S.; Grebhardt, A.; Jaeger, J.; Kern, F.; Killinger, A.; Bonten, C.; Gadow, R. Additive Manufacturing of β-Tricalcium Phosphate Components via Fused Deposition of Ceramics (FDC). Materials 2021, 14, 156. [CrossRef]

- Ghezzi, B.; Matera, B.; Meglioli, M.; Rossi, F.; et al. Composite PCL Scaffold With 70% β-TCP as Suitable Structure for Bone Replacement. International Dental Journal 2024, 74(6), 1220-1232. [CrossRef]

- Orchel, A.; Jelonek, K.; Kasperczyk, J.; Dobrzynski, P.; et al.. The Influence of Chain Microstructure of Biodegradable Copolyesters Obtained with Low-Toxic Zirconium Initiator to In Vitro Biocompatibility. BioMed Research International 2013, Article ID 176946, http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/176946.

- Smola, A.; Dobrzynski, P.; Cristea, M.; Kasperczyk, J.; Sobota, M.; Gebarowska, K.; Janeczeka, H. Bioresorbable terpolymers based on l-lactide, glycolide and trimethylene carbonate with shape memory behavior. Polym. Chem., 2014, 5, 2442-2452. [CrossRef]

- Formas, K.; Kurowska, A.; Janusz, J.; Szczygieł, P.; Rajzer, I. Injection Molding Process Simulation of Polycaprolactone Sticks for Further 3D Printing of Medical Implants. Materials 2022, 15, 7295. [CrossRef]

- Pivodová V.; Franková J.; Doležel P.; Ulrichová J. The response of oste-oblast-like SaOS-2 cells to modified titanium surfaces. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 2013,28,1386-94. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Fu, Y.; Jin, Y.; Weng, Y.; Bian, X.; Chen, X. Degradation Behaviors of Polylactic Acid, Polyglycolic Acid, and Their Copolymer Films in Simulated Marine Environments. Polymers 2024, 16, 1765. [CrossRef]

- Vey, E.; Rodger, C.; Booth, J.; Claybourn, M.; Miller, A.F.; Saiani, A. Degradation kinetics of poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid block copolymer cast films in phosphate buffer solution as revealed by infrared and Raman spectroscopies. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2011, 96, 1882–1889, . [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.;Lee, S.H.; Kim S.H.;, Lim, J.C.; Kim S.H. Synthesis and characterization of the biodegradable and elastic terpolymer poly(glycolide-co-L-lactide-co-ϵ-caprolactone) for mechanoactive tissue engineering. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition, 2013, 24(4), 386–397, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09205063.2012.690281.

- Kim, D.; Kim, K.H.; Yang, Y.S.; Jang, K.S.; Jeon, S.; Jun-Ho Jeong, J.H.; Park, S.A. 4D printing and simulation of body temperature-responsive shape-memory polymers for advanced biomedical applications. International Journal of Bioprinting 2024, 10(3), 3035. [CrossRef]

- Lu T.; Liang Y.; Zhang L.; Yuan X.; Ye J. Fabrication of β-TCP ceramic scaffold with hierarchical pore structure using 3D printing and porogen: Investigation of osteoinductive and bone defects. Applied Materials Today 2024, 40, 102351. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Models of a cuboid sample (a ,b) and a lattice structure with dimensions (mm) (c, d).

Figure 1.

Models of a cuboid sample (a ,b) and a lattice structure with dimensions (mm) (c, d).

Figure 2.

Samples for shape memory tests: (a, b) initial shape and (c, d) temporary shape.

Figure 2.

Samples for shape memory tests: (a, b) initial shape and (c, d) temporary shape.

Figure 3.

Stereoscopic microscope images of the terpolymer alloys at various magnifications.

Figure 3.

Stereoscopic microscope images of the terpolymer alloys at various magnifications.

Figure 4.

SEM images of discs and filament sticks, together with EDS analysis of TER_gran and TER_gran_5 samples.

Figure 4.

SEM images of discs and filament sticks, together with EDS analysis of TER_gran and TER_gran_5 samples.

Figure 5.

Stereoscopic microscope images of the filament sticks at various magnifications.

Figure 5.

Stereoscopic microscope images of the filament sticks at various magnifications.

Figure 6.

Stereoscopic microscope images of the scaffolds at various magnifications.

Figure 6.

Stereoscopic microscope images of the scaffolds at various magnifications.

Figure 7.

SEM image of the terpolymer scaffold modified with β-TCP.

Figure 7.

SEM image of the terpolymer scaffold modified with β-TCP.

Figure 8.

FTIR spectra of the discs samples (BL) and scaffolds: (1) β-TCP powder; (2) terpolymer modified with 5% β-TCP, and (3) pure terpolymer, including magnified wavenumber ranges of (I) 500–650 cm⁻¹ and (II) 350–450 cm⁻¹.

Figure 8.

FTIR spectra of the discs samples (BL) and scaffolds: (1) β-TCP powder; (2) terpolymer modified with 5% β-TCP, and (3) pure terpolymer, including magnified wavenumber ranges of (I) 500–650 cm⁻¹ and (II) 350–450 cm⁻¹.

Figure 9.

DSC curves for: the modifier β-TCP and sticks molded from the investigated terpolymer (without and with 5% β-TCP), recorded over a temperature range of -30 °C to approximately 180 °C during heating at a rate of 20 °C/min under a nitrogen flow of 40 ml/min.

Figure 9.

DSC curves for: the modifier β-TCP and sticks molded from the investigated terpolymer (without and with 5% β-TCP), recorded over a temperature range of -30 °C to approximately 180 °C during heating at a rate of 20 °C/min under a nitrogen flow of 40 ml/min.

Figure 10.

DSC curves for the tested terpolymer in melt, stick, and scaffold forms, both pure (a) and with 5% β-TCP (b), recorded over a temperature range of -30 °C to approximately 180 °C. Measurement conditions as described above, with analysis of the glass transition and melting regions.

Figure 10.

DSC curves for the tested terpolymer in melt, stick, and scaffold forms, both pure (a) and with 5% β-TCP (b), recorded over a temperature range of -30 °C to approximately 180 °C. Measurement conditions as described above, with analysis of the glass transition and melting regions.

Figure 11.

DSC curves for the unmodified investigated terpolymer, recorded over a temperature range of -30 °C to 225 °C during the first heating run (scaffold) and second heating run (melted scaffold). Measurement conditions as described above, with analysis of the glass transition and melting regions.

Figure 11.

DSC curves for the unmodified investigated terpolymer, recorded over a temperature range of -30 °C to 225 °C during the first heating run (scaffold) and second heating run (melted scaffold). Measurement conditions as described above, with analysis of the glass transition and melting regions.

Figure 12.

TG and DTG curves of shape memory terpolymer sticks and scaffolds, both unmodified and modified with β-TCP, recorded in heating mode at 20 °C/min under a nitrogen purge of 60 ml/min, over a temperature range of 30 to 650 °C.

Figure 12.

TG and DTG curves of shape memory terpolymer sticks and scaffolds, both unmodified and modified with β-TCP, recorded in heating mode at 20 °C/min under a nitrogen purge of 60 ml/min, over a temperature range of 30 to 650 °C.

Figure 13.

Photographs of samples made from (a) TER_gran_BL and (b) TER_β-TCP_5_BL alloys during recovery to their original shape.

Figure 13.

Photographs of samples made from (a) TER_gran_BL and (b) TER_β-TCP_5_BL alloys during recovery to their original shape.

Figure 14.

Average recovery degree of the samples with standard deviationThe shape memory studies demonstrated an enhanced ability to return to the original shape in samples made from pure terpolymer (TER_gran_BL) compared to samples made from the terpolymer modified with the additive (TER_β-TCP_5_BL).

Figure 14.

Average recovery degree of the samples with standard deviationThe shape memory studies demonstrated an enhanced ability to return to the original shape in samples made from pure terpolymer (TER_gran_BL) compared to samples made from the terpolymer modified with the additive (TER_β-TCP_5_BL).

Figure 15.

(a) MTT assay showing Saos-2 cell viability, expressed as a percentage of the control. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed using a t-test, with the following significance levels: nonsignificant (ns) at p > 0.05, significant at p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), and p < 0.001 (***). (b) ALP activity after incubation of Saos-2 cells with the tested samples. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed using a t-test, with nonsignificant (ns) at p > 0.05 and significant at p < 0.05 (*).

Figure 15.

(a) MTT assay showing Saos-2 cell viability, expressed as a percentage of the control. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed using a t-test, with the following significance levels: nonsignificant (ns) at p > 0.05, significant at p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), and p < 0.001 (***). (b) ALP activity after incubation of Saos-2 cells with the tested samples. Data are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). Statistical analysis was performed using a t-test, with nonsignificant (ns) at p > 0.05 and significant at p < 0.05 (*).

Figure 16.

Fluorescence microscopy images of cells cultured on β-tricalcium phosphate-modified materials and unmodified materials (TER_gran_BL) after 1 day, 1 week, and 3 weeks of incubation at 4× magnification. Cells were stained with acridine orange, highlighting viable cells in green (n = 3).

Figure 16.

Fluorescence microscopy images of cells cultured on β-tricalcium phosphate-modified materials and unmodified materials (TER_gran_BL) after 1 day, 1 week, and 3 weeks of incubation at 4× magnification. Cells were stained with acridine orange, highlighting viable cells in green (n = 3).

Table 1.

Parameters of the injection molding process for filament sticks and samples for mechanical testing (dog-bone shape).

Table 1.

Parameters of the injection molding process for filament sticks and samples for mechanical testing (dog-bone shape).

| Parameters |

Filament sticks |

Dog-bone shape samples |

|

| TER_gran |

TER_β-TCP |

TER_gran |

PCL |

|

| Plastification temperature [°C] |

125 |

135 |

125 |

160 |

|

| Chamber temperature [°C] |

130 |

132 |

130 |

151 |

|

| Nozzle temperature [°C] |

140 |

131 |

140 |

165 |

|

| Injection size [mm] |

18 |

18 |

24 |

24 |

|

| Cooling time [s] |

28 |

28 |

60 |

60 |

|

| First injection pressure [bar] |

113 |

107 |

113 |

130 |

|

| Time of the first injection pressure [s] |

1.9 |

2.0 |

11 |

11 |

|

| Second injection pressure [bar] |

60 |

60 |

90 |

90 |

|

| Time of the second injection pressure [s] |

5.3 |

5.3 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

|

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of the pure terpolymer and the longitudinal wave velocity determined from ultrasonic testing.

Table 2.

Mechanical properties of the pure terpolymer and the longitudinal wave velocity determined from ultrasonic testing.

| Type of sample |

Young’s modulus

[MPa] |

Tensile strength

[MPa] |

Strain at break

[%] |

VL1

[m/s] |

Terpolymer

Polycaprolactone |

1492.4 ± 129.1

407 ± 20 |

45.95 ± 3.25

31.95 ± 1.95 |

3.36 ± 0.35

658.99 ±46.09 |

2312.5 ± 13.8

1995 ± 10.5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).