1. Introduction

There is a large potential for energy optimization of historic buildings, as 35% of EU’s buildings are more than 50 years old [

1] and the building stock is characterized by a low energy performance and high energy consumption [

2]. Historic buildings are under threat, partly due to deterioration, and partly due to convenient renovations instead of careful restoration [

1]. Therefore, there are plenty of reasons for developing more careful restoration approaches, combined with energy optimization. The present energy crisis emphasizes the urgency for lowering the energy consumption in the entire existing building stock, including historic buildings, but at the same time stresses the dilemma of how to maintain the architectural and cultural values of the historic buildings.

The challenge of how-to energy-optimize historic buildings without spoiling the architectural values of the buildings is a shared problem across European countries and cities and has been researched thoroughly in recent decades [

1,

2,

3]. Despite the potential challenges related to energy optimization of historic buildings, including architectural and historical restrictions [

4], several studies have found that significant energy reductions are possible [

5,

6,

7]. However, it remains uncertain to what extent the results from these case studies are transferable to the historic building stock in general, and what the overall status of energy performance in historic buildings is. Systematic research and knowledge on energy optimization of historic buildings beyond single case studies are rare [

6]. There are, however, some exceptions ([

3,

8,

9]), which have used register-based analysis to combine data on energy performance and preservation values, creating an overview of the entire stock of historic buildings, albeit in limited geographical areas (Amsterdam, The Hague, and Rotterdam in the Netherlands, and Stockholm municipality and Halland county in Sweden). The results from these studies are varied; Eriksson & Johansson found only a limited correlation between heritage classification and energy performance, highlighting the large heterogeneity in the stock of historic buildings [

3]. They argue for a differentiated strategy for optimizing historic buildings but emphasize that the energy-saving potential in historic buildings is limited compared to the entire building stock. Van Krugten et al. found that the energy performance of historic dwellings (built before 1970) is lower compared to modern dwellings (built after 1970), but there is no clear evidence that historic buildings are unsustainable [

9].

The conclusions on whether historic values prevent the utilization of more energy-efficient solutions are not definitive. The differences between historic and ordinary buildings might be attributed to the varying building technologies used in pre-1970 and post-1970 constructions. Additionally, the research is based on a relatively small number of EPC labels, making the results more indicative [

9]. These two studies highlight that different definitions are used for “historic buildings,” “listed buildings,” and “heritage values,” necessitating caution when interpreting the results. For instance, in the Dutch context, historic buildings are defined as those built before 1970, representing 46% of the Dutch building stock, including explicitly “listed” buildings. The study by Eriksson & Johansson uses heritage values of the local building stock on a scale from A to C, defined by regional bodies in Stockholm and Halland [

3].

The Danish context for energy optimization of historic buildings

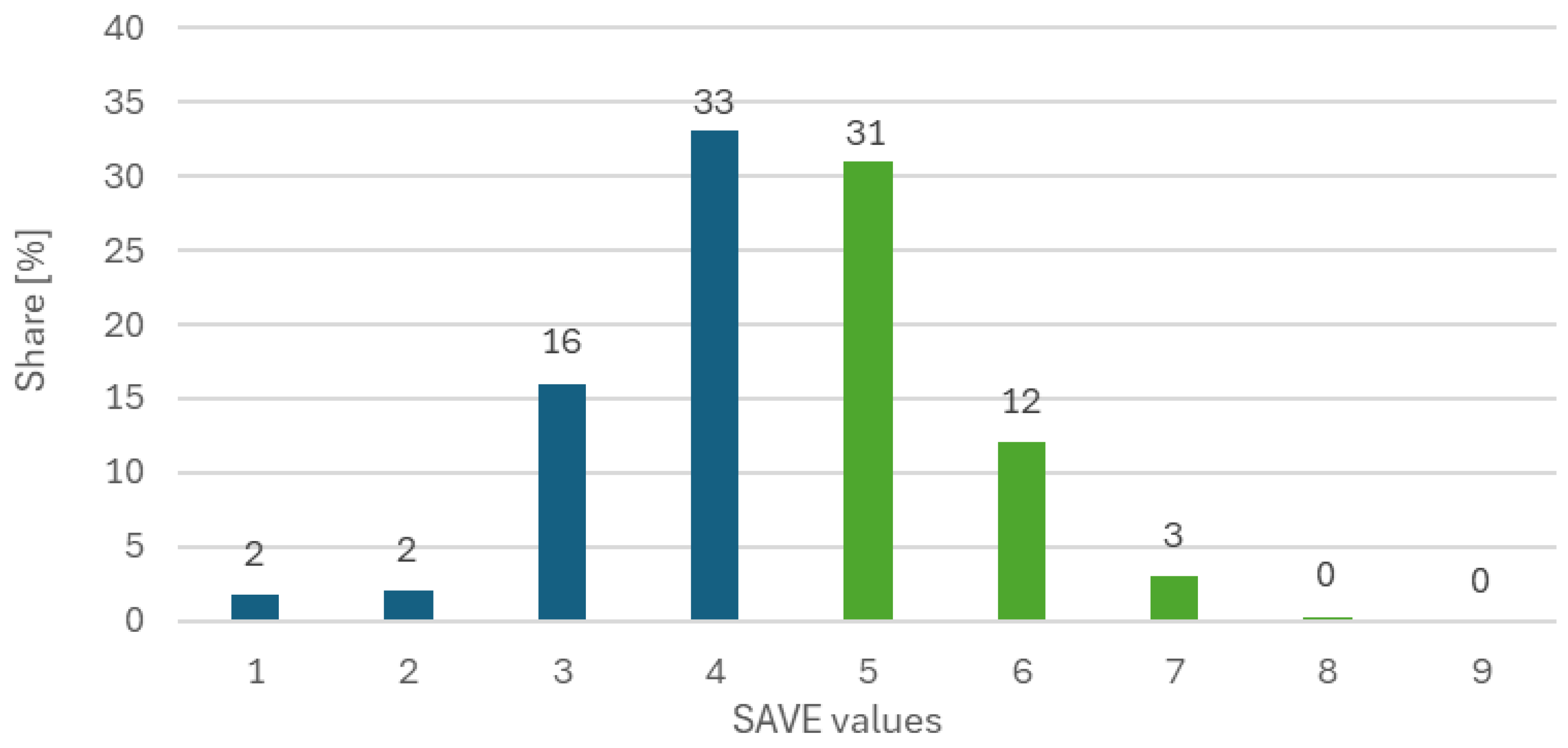

In Denmark, historic buildings are registered using the SAVE methodology (Survey of Architectural Values in the built Environment), which assesses the preservation value of existing buildings based on conservation values ranging from 1 to 9, with 1 being the highest [

10]. The grades are assigned within categories such as architectural value, cultural-historical value, environmental value, originality, and construction technical condition, covering buildings with high, medium, and low conservation value. Buildings with a SAVE value of 1 to 4 are considered “unconditionally worthy of preservation,” while those in categories 5 to 6 are seen as “even, but nice buildings, where typically unsuitable replacements and conversions detract from their character” [

10]. In this study, we use the term “historic buildings” for those with SAVE values of 1-4. There is some overlap between buildings with a SAVE value of 1 and “listed buildings,” the latter defined by the Danish Agency for Culture and Palaces and having legal status, unlike SAVE registrations. The buildings registered in FBB are not comprehensive, as historic buildings can also be designated through local plans, older town planning statutes, registered conservation declarations, or as listed buildings by the Danish Palaces and Culture Agency. These buildings do not necessarily appear in the FBB database [

11]. The SAVE system was introduced in Denmark in 1991. It is the responsibility of the 98 Danish municipalities to register buildings within their jurisdiction, and this is done with some variation. Since 1991, 90 SAVE atlases have been published [

10]. Although municipalities are officially required to update the SAVE registrations of historic buildings, the updating of municipal atlases has largely ceased since the municipal structural reform in 2007 [

12]. All SAVE registrations are stored in the Danish Agency for Culture and Palaces’ SAVE database for listed and historic buildings (Fredede og Bevaringsværdige Bygninger), commonly referred to as “FBB.” The FBB database contains information on approximately 7,000 listed buildings and 350,000 buildings assessed using the SAVE methodology. The FBB database includes information on 72,000 apartment buildings, which corresponds to 73% of the country’s approximately 100,000 apartment buildings (

www.statistikbanken.dk/BYGB12). The register is thus reasonably comprehensive for apartment buildings. In the FBB register, 19,734 multi-story residential buildings are valued with a high conservation value (SAVE 1-4), corresponding to 20% of all apartment buildings in the country. These buildings represent a significant share of “ordinary” residential buildings, which may not be architecturally or historically outstanding but still hold major value for the built environment as a whole.

The distribution of SAVE values in Danish apartment buildings erected before 1950 is shown in

Figure 1 below.

In general, the research in Scandinavian countries on energy optimization of historic buildings has been relatively limited compared to countries in southern Europe [

1]. In Denmark, previous studies have found that energy savings in historic buildings are possible without harming the architectural values [

5,

13,

14,

15]. The studies have also focused on specific solutions for heritage buildings, e.g. internal insulation [

15], and to which extent increased energy efficiency might affect the durability of heritage buildings, especially in relation to moisture problems [

13,

14]. However, this research is, as for the majority of the international research literature, based on cases of individual buildings, and little has been studied about the general standard of historic buildings.

The EU building directive has sparked renewed discussion about the energy optimization of the building stock, including historic buildings. The latest directive, adopted by the EU Parliament and Commission in April 2024, aims to reduce CO

2 emissions by at least 55% by 2030 and contribute to making the building stock CO

2-neutral by 2050 [

16]. To achieve this target, each Member State must establish a national building renovation plan for both residential and non-residential buildings and ensure that minimum energy performance requirements are set to achieve at least cost-optimal levels [

16]. Member States may adapt these requirements for buildings officially protected at national, regional, or local levels due to their special architectural or historical merit.

The recent implementation of the EU building directive has raised concerns about how the energy demands requirements might affect historic buildings. These concerns, mainly voiced by building and restoration professionals, have generated a debate on how to protect historic buildings from being “wrapped in building insulation materials”, an often-used phrase to signalize the danger of energy demands on historic buildings. The debate highlights the challenge of historic buildings being caught between preservation and energy optimization, as well as a lack of knowledge about the actual energy performance of historic buildings and the potential for energy improvements without harming their architectural values. Based on this background, the research questions for this study are:

What is the energy standard of historic buildings?

What are the potentials for improving their energy performance, and is there hope for bringing them up to an acceptable energy performance level?

Is it possible to achieve this without compromising the historic and architectural values of the buildings?

The underlying aim of the project is to identify and disseminate knowledge about energy renovation of historic buildings and to identify suitable energy optimization solutions when renovating historic buildings.

3. Results

3.1. Status for Energy Performance of Historic Apartment Buildings

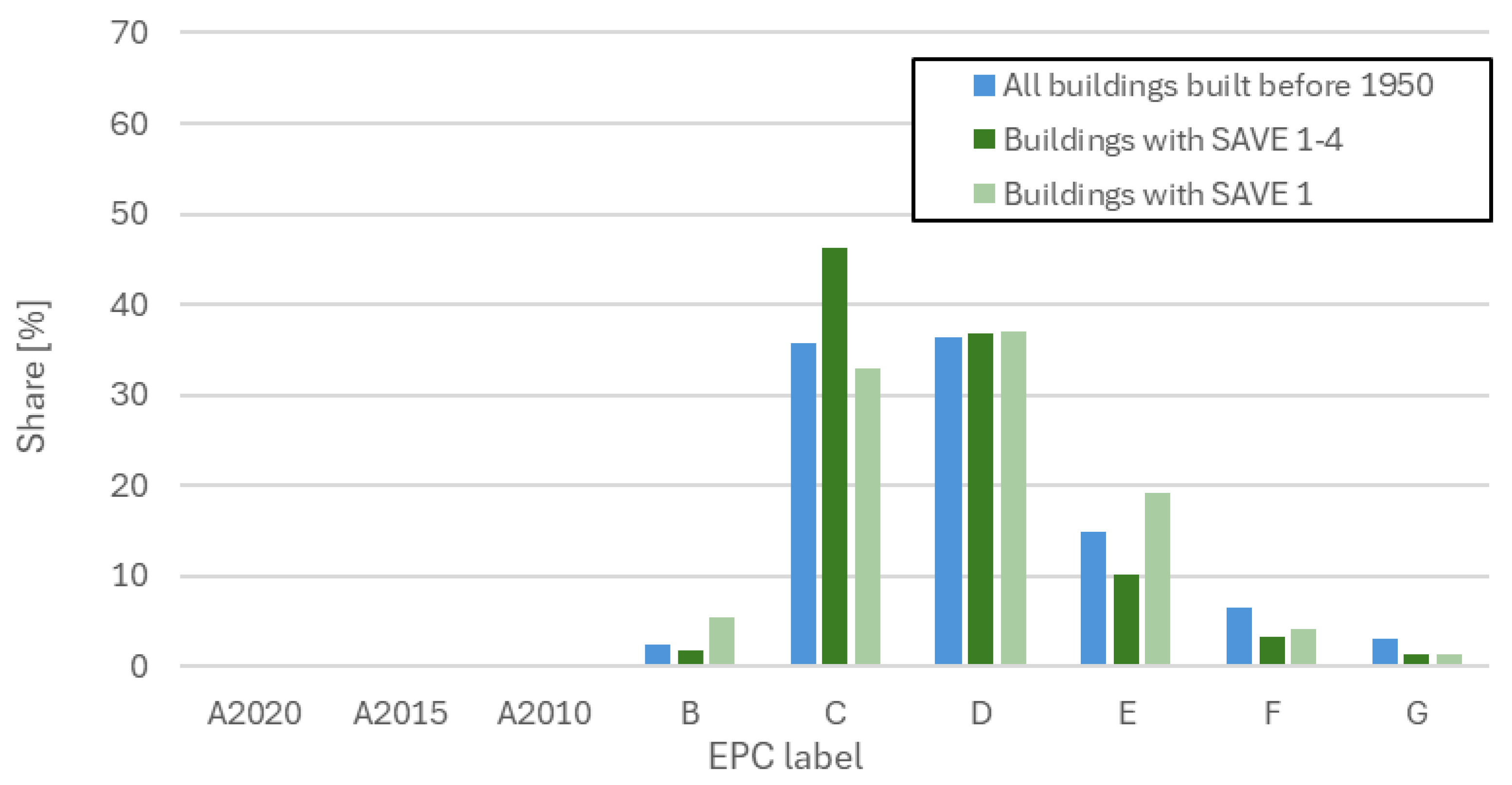

Out of the nearly 20,000 apartment buildings with SAVE-values from 1-4 , just over 13,000 have an EPC label. Of these, 76% were completed in 2011 or later (52% have an EPC rating valid up to and including 2021, while 48% have an EPC label valid from 2022 onwards). The analysis includes both new and old labels, as the 5-year limit does not reflect a deteriorated energy standard but is determined administratively.

Figure 2 shows the distribution of all 13,000 historic apartment buildings with an EPC label, compared to all apartment buildings erected before 1950, and to apartment buildings with the highest preservation value (SAVE 1). SAVE 1 buildings overlap to some extent with listed buildings, where very few physical changes are allowed. One might therefore expect that the energy performance of SAVE 1 buildings is lower than for buildings in general. Listed buildings are appointed by the National Agency for Culture and Palaces and include approximately 7,100 buildings, ranging from houses, apartment buildings, palaces, mansions, public buildings, factories and other types of buildings. Of these, 1,898 are apartment buildings. The number of apartment buildings with SAVE 1 is 588.

The analysis shows that 46% of the historic buildings have an EPC label C, which is higher than buildings from the same age in general (36%) and for buildings with the highest preservation value (SAVE 1, 33%). For EPC label D, the distribution is more or less the same across the three groups of buildings (36%). For EPC labels E, F, and G, the share of historic buildings is lower than for buildings in general and buildings with the highest preservation values. In general, the share of buildings with EPC labels F and G is quite low, less than 10% for all buildings, and even lower for buildings with higher SAVE values.

Overall, the numbers indicate that the preservation values of the buildings have not hindered their energy optimization. For buildings with SAVE 1, the energy performance is approximately on the same level as older buildings in general, which is somewhat surprising. This could indicate that buildings with high preservation values might have a higher market value (e.g., due to their location), are more updated, or are generally in better physical condition, leading to a better EPC label. Another interpretation could be that the energy optimization that has taken place in historic buildings has had some negative consequences for the architecture and preservation values of the buildings.

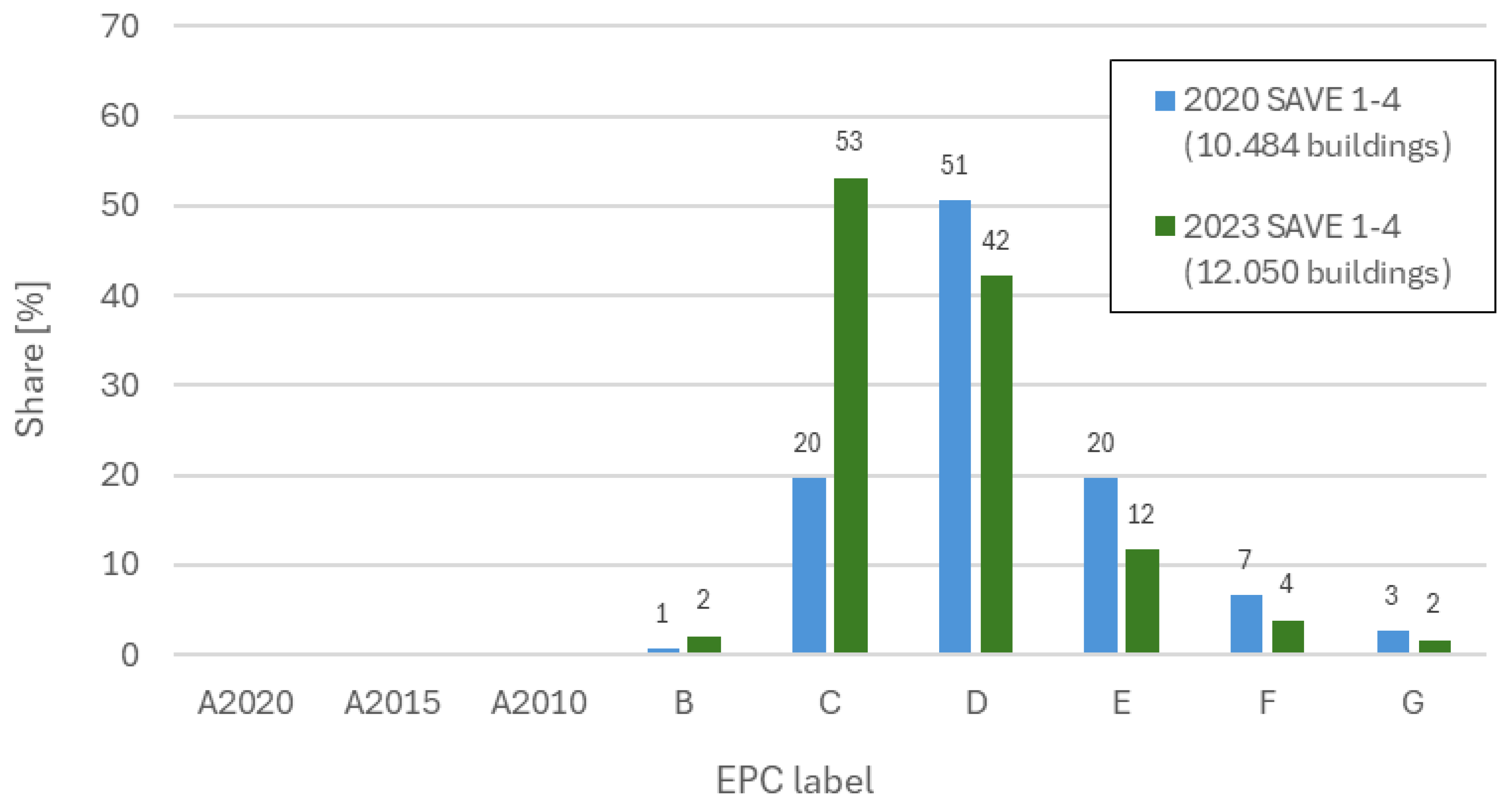

The dataset from 2023 was compared to a similar dataset from 2020. This comparison showed significant improvements in the EPC labels among the buildings; 38% of all historic buildings had improved their EPC label, and the number of C-labelled apartment buildings more than doubled (from 2,060 buildings to 5,575 buildings), corresponding to a share of 20% in 2020 and 53% in 2023. At the same time, the share of E-, F-, and G-labels was reduced from 30% in 2020 to 18% in 2023 (see

Figure 3).

The improvements in energy labels could be due to several factors. Many buildings’ previous energy labels expired and had to be renewed after 2020, meaning that the improvements, to the extent they are incremental, may have occurred over a period of up to 10 years. Other reasons for the improved EPC labels could include increasing housing demand and rising property prices, especially in larger cities, combined with tighter requirements for energy improvements in building renovation projects according to building regulations. Private landlords, who own 36% of the historic building stock, have been particularly motivated for energy retrofitting due to the “Blackstone intervention” in July 2020, a national regulation requiring at least an EPC “C” label to raise rents following major renovations. This has led private landlords, including institutional investors and pension funds, to focus more systematically on achieving a C-label.

Another significant factor is the public housing sector, which owns 9% of the historic building stock and decided to renew EPC labels in 88,000 homes during 2021-2022. This decision may have also affected the overall EPC performance of apartment buildings, including historic buildings. Various public programs and subsidies have been established to increase energy efficiency in the existing housing stock, such as the “Green Housing Agreement” from 2020, which provides subsidies for insulation, window replacement, heat pump installation, etc. Additionally, rising energy prices from 2020 to 2023 may have increased the focus on energy improvements among homeowners, including connecting to the district heating network, which leads to better EPC labels.

The improvement in EPC labels has led to reduced energy use in historic buildings.

Table 1 shows data for measured energy consumption in various apartment buildings, according to their EPC label. It illustrates that changing a building from an EPC label “E” to “C” typically results in energy savings of 22% (from 139 kWh/m² to 109 kWh/m²), and changing from a “D” to a “C” results in savings of 13% (from 125 kWh/m² to 109 kWh/m²).

3.1.1. Regional Variations in Energy Performance

The national-wide dataset for energy performance of historic buildings might hide local differences, such as variations in building types, renovation activity, energy performance etc. The register-based studies by [

3] and [

9] shows that there can be big differences between the energy performance of buildings in different cities and districts, e.g. as urban and rural settings, and therefore the potential for further energy improvements differs. Following this, the local policies towards improving the energy efficiency in those buildings could be differentiated [

3].

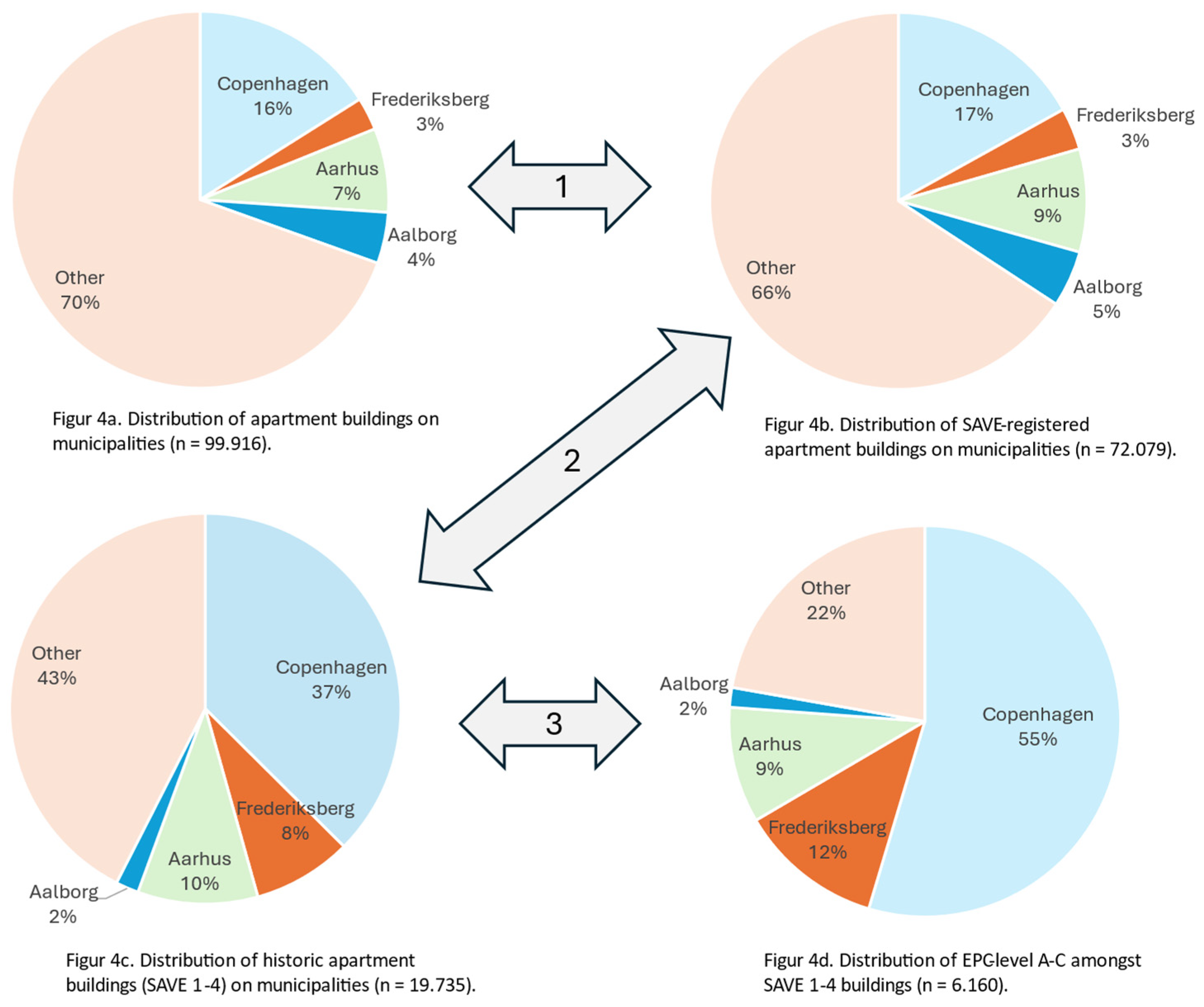

Our dataset also shows regional differences in the energy performance of historic apartment buildings. We have broken the data down in four larger urban municipalities and the remaining group of “other” municipalities. The four urban municipalities include: Copenhagen (the largest in Denmark (in terms of inhabitants), Aarhus and Aalborg municipalities (the second and third largest) and Frederiksberg the 7th largest municipality is, located next to Copenhagen, with a similar building structure and is known for its progressive building heritage policy). The remaining 94 municipalities include larger provincial municipalities, as well as municipalities in more remote and rural regions. The breakdown shows (

Figure 4) that of the almost 100,000 apartment buildings in the country, 30% are located in the municipalities of Copenhagen, Frederiksberg, Aalborg and Aarhus (

Figure 4a). The share of SAVE-registered apartment buildings is distributed in roughly the same way (

Figure 4b) which indicates that the selected municipalities have been equally active in their SAVE-registrations of apartment buildings. In contrast, the proportion of SAVE-registered buildings with a high conservation value (

Figure 4c) is overrepresented in Copenhagen and Frederiksberg municipalities (20% of all SAVE buildings, but 43% of all SAVE 1-4 buildings), and underrepresented in "other municipalities" (66% of all SAVE properties, but 43% of all SAVE 1-4 buildings). This difference is even more accentuated when looking at the share of apartment buildings having both a high SAVE-value and a good EPC label; here, Copenhagen municipality is overrepresented (55% of SAVE 1-4 apartment buildings with EPC A-C, but 37% of all SAVE 1-4), the same goes for Frederiksberg municipality (12% of SAVE 1-4 apartment buildings with EPC A-C, but 8% of all SAVE 1-4). Aarhus and Aalborg municipalities more or less are equally represented, whereas the group of “other” municipalities are under-represented (43% of all SAVE 1-4 but 22% of SAVE 1-4 apartment buildings with EPC A-C).

In other words, the group of historic apartment buildings located in “other” municipalities has been less energy-optimized. This might be due to lower housing demand, lower real estate prices, and lower rents in these municipalities compared to larger cities like Copenhagen, Frederiksberg, Aarhus, and Aalborg, as well as less frequent renovations.

3.2. Potentials for Improving the Energy Efficiency in Historic Apartment Buildings

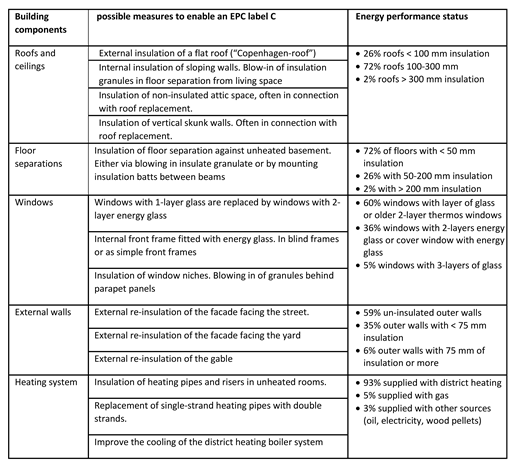

To identify which physical and technical improvements that have led to the increased EPC-performance, a number of EPC-reports for buildings with an EPC-label of B or C were reviewed, as the reports often include a short historic summary of the renovations and changes that has been made over time. Moreover, interviews were made with EPC-consultants, on their experiences on energy retrofitting of historic apartment buildings, and how EPC-labels of C or B could be achieved. The review of the EPC-reports and the interviews showed that there are several technical improvements that enable the historic apartment buildings to achieve an EPC-label of B or C, see

Table 2 below. In general, many of these improvements do not harm or change the buildings physically and visually (e.g. connection to the district heating network and insulation of floor separations), but other energy improvements might change the expression, e.g. insulation of the roof, changing of windows and insulation of gables and facades. This overview was supplied with data from the National Building Register (BBR) to indicate how big a share of the building stock had already implemented these improvements. As shown in

Table 2, there is still a large potential for improvements, e.g. for more insulation of roofs and for better windows. It should be mentioned, however, that it is the owner who is responsible for updating the National Building Register (BBR) for his or her own property, and many owners don’t do that systematically, which means that the status is probably underestimated.

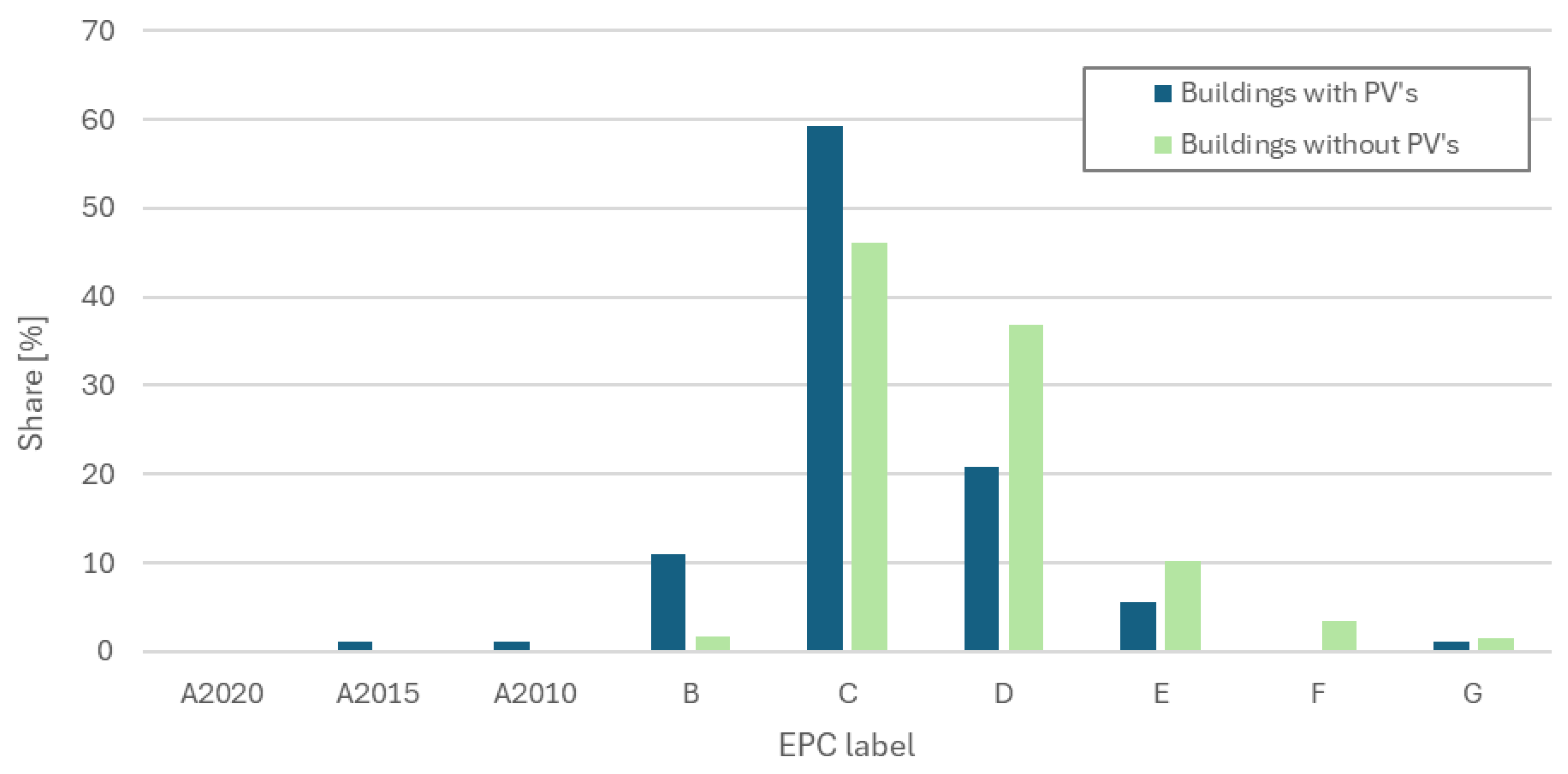

Solar cells (PV’s) have only been installed in 83 historic buildings (0.4 % of all historic buildings) and is thus not included in the list of “typical energy improvements” above. However, PVs might be a way to improve the energy performance of historic buildings; as shown in

Figure 5, historic buildings with PV’s have a higher share of EPC-labels than historic apartment buildings without PV’s. Due to the preservation of historic values, municipal administrations are reluctant to allow building owners to install them. 88% of the historic buildings with PV’s installed are located in three municipalities (Copenhagen, Frederiksberg and Odense), which shows that there are different approaches to PV’s amongst the Danish municipalities.

Another rare intervention in historic apartment buildings is mechanical ventilation, which is being used in 18% of the buildings, of which 4% has heat regeneration included. This indicates a large and overlooked potential for energy savings and better indoor climate, but this could also be difficult to combine with preservation of historic buildings.

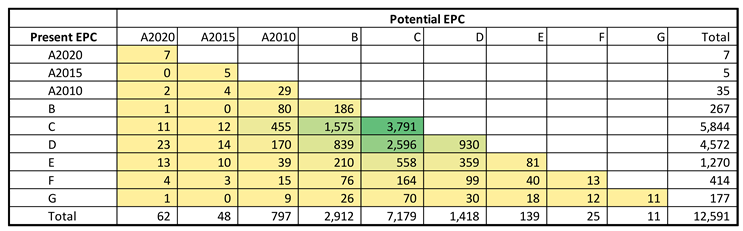

A similar indication of the potential for energy improvements in the historic buildings is the assessments of the potential EPC-label made in the EPC-reports. The reports contain a list of possible technical improvements that could be made, and an assessment of which EPC-label the building would be able to achieve, if the improvements were implemented. In this assessment, only improvements with a “reasonable” profitability are included, meaning technical improvements with a reasonable payback time. The “potential EPC label” is included in the EPC-database. A data extract from the EPC-register of historic buildings shows that the majority of the historic buildings could achieve a better EPC-label for improvements with “reasonable” profitability:

The number of buildings with an EPC C-label could increase from 5.844 to 7.180

The number of buildings with an EPC B-label could increase from 268 to 2912

More than half of the buildings with an EPC D-label could improve to an EPC C-label (2.596 buildings out of 4.572 buildings, or 57%)

The app 600 buildings with an EPC-label F and G buildings could literally disappear (36 buildings)

Table 3.

Potential EPC-labels that existing historic apartment buildings could achieve (according to the EPC reports in the dataset for 2023).

Table 3.

Potential EPC-labels that existing historic apartment buildings could achieve (according to the EPC reports in the dataset for 2023).

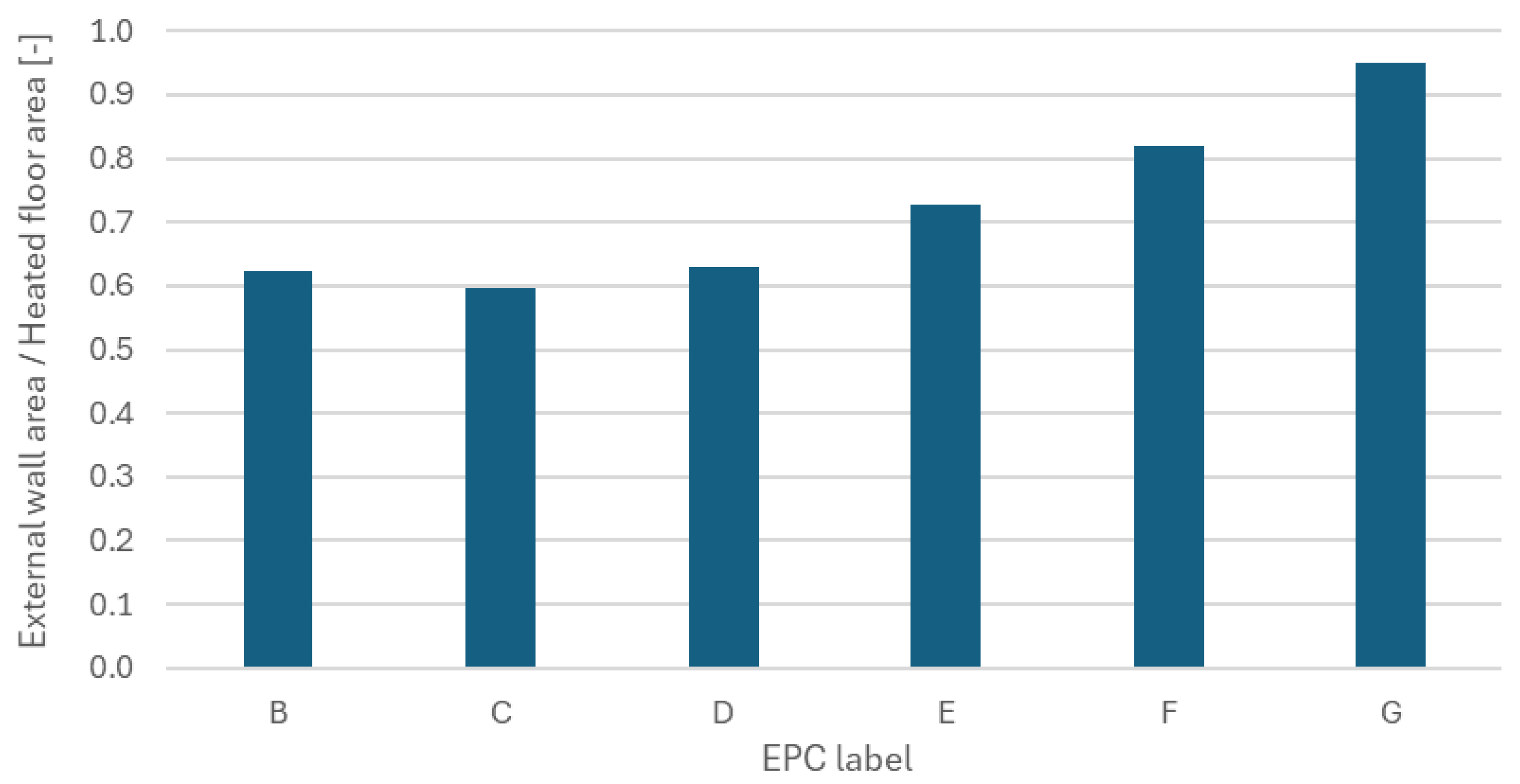

Although these estimates should be taken with some reservations, it indicates that there is a large potential for further improvements. This shows that especially better windows and better insulation of the roof have a large potential for improving the energy standard of the building. Also, the heat supply is important for the buildings EPC label. In the EPC-calculations that the EPC-label is based on, buildings with district heating are reduced by a factor of 0.8 in the calculation of heat consumption when compared to buildings that are supplied with gas, oil, or other sources. Conversely, buildings with oil boilers have in the calculation of the EPC label, an increase in heat consumption by a factor of 1.2. Since 93% of the residential multi-story buildings with high preservation values (SAVE 1-4) are supplied with district heating, they gain an advantage in that way alone. Although 93% of the historic apartment buildings are supplied with district heating, and the potential seems limited, the supply will increasingly be based on renewable energy sources which will reduce the CO2-emissions of the energy supply, and also improve the energy performance of the buildings. Also, structural factors of the building are important; buildings that are located side by side in a row of houses receive an indirect heat supplement by not emitting heat to the surroundings. They thus achieve a good EPC label more easily, compared to detached buildings. Finally, buildings that have a small surface area, compared to their total floor area, have an advantage in terms of reducing heat loss. An analysis of the energy labels shows that buildings with energy labels B, C, or D have an average ratio between external walls and floor area of around 0.6, while buildings with energy labels G have an average ratio between external walls and floor area of 0.95 (see

Figure 6).

3.3. Conflicts Between Energy Improvement and the Architectural Values of Historical Buildings

The question is whether energy improvements have had, and continue to have, consequences for the architectural values of historic buildings. As suggested above, many improvements can be made with minimal or no negative impact on architectural values. However, some interventions might result in more debatable changes to historic buildings, such as external insulation of outer walls and the installation of PVs on roofs. The conflicts between energy optimization and the protection of cultural heritage, and what municipalities can do to balance them, will be addressed in the discussion.

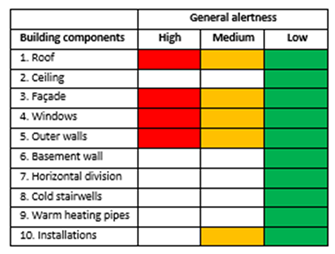

Based on interviews with energy consultants, we have classified the various technical interventions mentioned in

Table 2 according to the level of caution that should be exercised when using these interventions in historic buildings—ranging from low, medium, to high caution (see

Table 4). None of the improvements significantly affect the architectural presence if carried out carefully. Buildings with EPC labels of C have not necessarily implemented all these improvements but may have adopted only some measures, such as improvements to windows and roofs.

Particularly for window improvements (typically new windows), local authorities pay close attention to ensure that the architectural expression of the buildings is not harmed, often leading to intense discussions with owners about which specific solutions to choose. Additionally, external insulation of the façade in the yard (backside of the building) can be delicate, but this solution is relatively rare.

3.4. Examples on Renovation of Historic Buildings

In the following, we present three cases of renovation of historic apartment buildings, each representing a way to achieve an EPC label of C or better. Renovations of apartment buildings typically occur in one of three ways: A) “Step-by-Step Renovation”, with small improvements made over time. B) “Larger renovations”, with many improvements made simultaneously but with preservation of the basic structures. C) “Transformations”, where major changes of the structure are made, with respect for the historic and architectural values. The three examples represent these approaches, with increasing levels of intervention from A) to C).

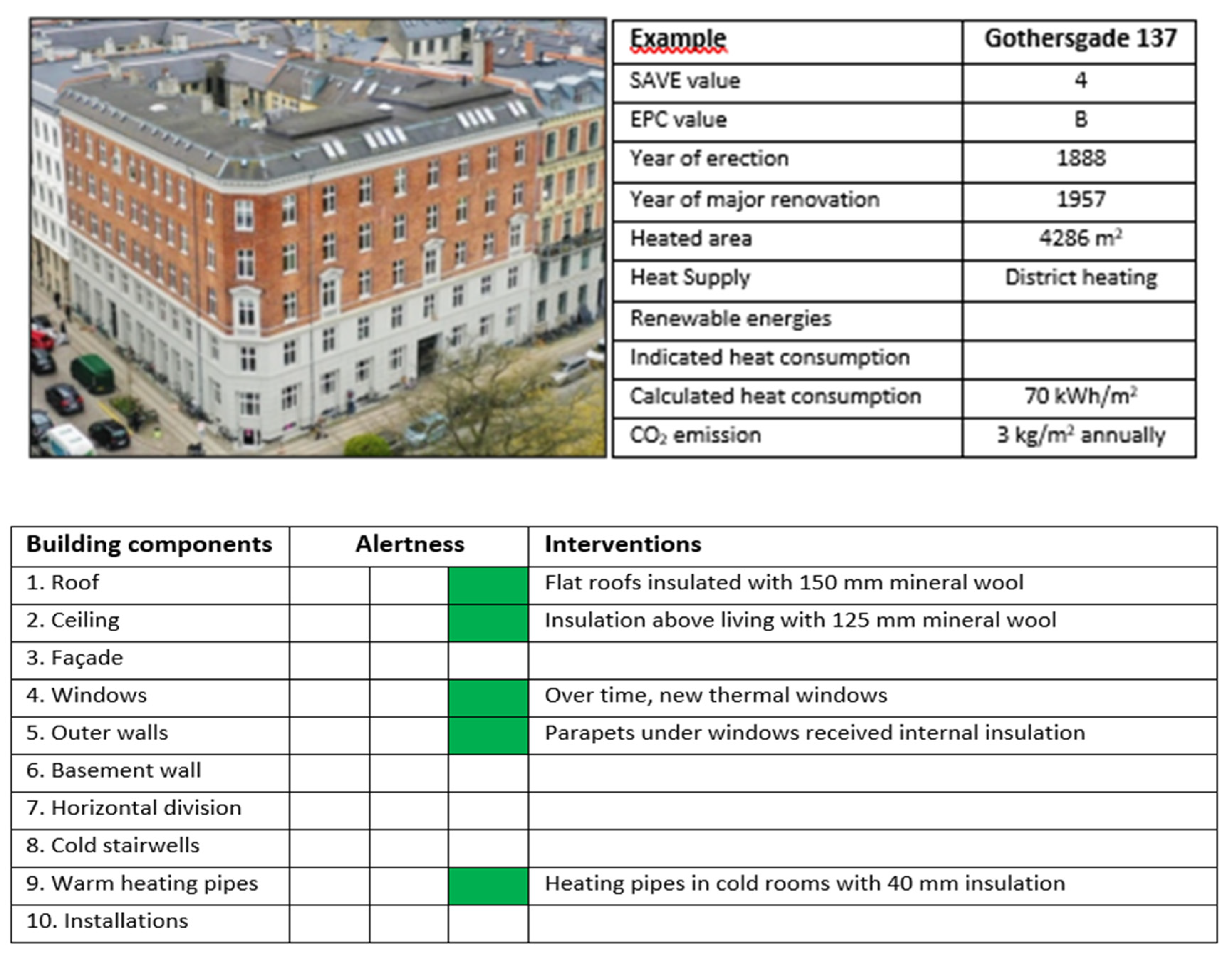

Gothersgade 137: A “Step-by step renovation”. This apartment building is located in the inner city of Copenhagen. Built in 1880, it has 5 floors and a basement. The building has a SAVE value of 4 and an EPC label of B (2000). According to the EPC report, the building has not undergone any changes since a major renovation in 1957. The 2020 EPC report states that the cold attic space facing the living area was insulated with 125 mm of mineral wool, as were the sloping ceilings. Flat roofs facing heated rooms are estimated to be insulated with 150 mm of mineral wool. All exterior walls consist of 36-72 cm brick walls without cavities and insulation. At a later stage, the property was fitted with new windows with triple-pane energy glass. Additionally, parapets under the windows were reinsulated, and all heating pipes received 40 mm of insulation.

Figure 7.

Gothersgade 137, with information about the building and main interventions. Photo credit: B2B film.

Figure 7.

Gothersgade 137, with information about the building and main interventions. Photo credit: B2B film.

The building is large and compact, which means the limited surface area exposed to the outside contributes substantially to its energy performance. Over time, the owner and the administrator have made decisions on upgrades without consulting the municipality. Nonetheless, the owner was surprised to find that the building had achieved an EPC label of B, as none of the upgrades were specifically intended to improve energy efficiency. This example shows that under certain conditions, compactness, district heating, ordinary maintenance, and replacing old windows with modern low-energy windows can be sufficient to achieve an EPC label of B. This means that the property, with the limited interventions made, can be further improved in terms of energy performance and potentially reach an EPC label of A without jeopardizing its conservation value of 4 on the SAVE scale. With an energy label of B, the property has a heat consumption of 70 kWh/m². Since the district heating comes from the Capitals Supply (HOFOR), which in 2023 emitted 35 g CO2 per kWh delivered, this means that the example property of step-by-step renovation emits a total of 3 kg CO2 per square meter annually.

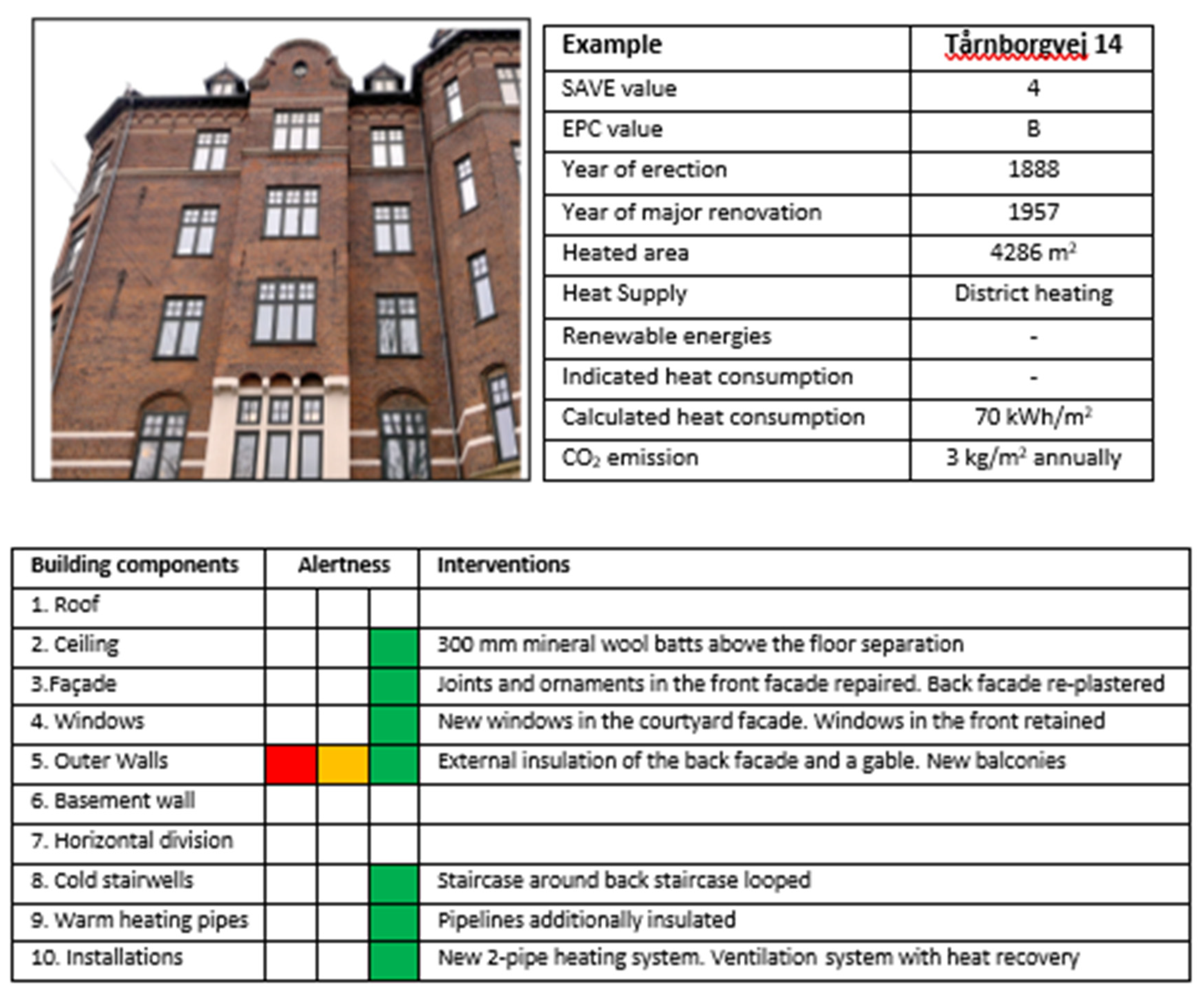

Tårnborgvej 14: A “larger renovation”. This apartment building is located in the municipality of Frederiksberg, part of Greater Copenhagen. It is a multi-story property with 5 floors, built in 1902 and owned by a fund. The building has a SAVE value of 4 and an EPC label of C (2020). Prior to renovation, the EPC label was E.

Figure 8.

Tårnborgvej 14 with information about the building and main interventions. Photo credit: The authors.

Figure 8.

Tårnborgvej 14 with information about the building and main interventions. Photo credit: The authors.

The building was renovated in 2018 with urban renewal support from Frederiksberg municipality. The renovation included restoring the facade to its original appearance, thus improving the architectural value of the building. At the same time, external insulation was added to the rear facade facing the yard (see picture below). The gable to the north was retrofitted in the same way. The renovation also included insulation of the roofs and floor separations. The window niches behind the radiators facing the facade were insulated. An old one-pipe heating system was replaced with a two-pipe system. Mechanical ventilation with heat recovery was installed during the kitchen and bathroom renovations. The windows from 1980 were retained, although they differ from the original design.

The municipality played an active role in the renovation process, collaborating with the owner fund and an energy consultant. The insulation of the rear facade, in particular, required many considerations and discussions on how to design it to be less visible and fit with the existing neighboring buildings. According to the municipality, at the beginning of the renovation process, there was no preservation plan for the property. Therefore, it was not possible at that time to reject the consultants’ and owners’ wish to add external insulation to the rear facade. However, the municipality might have wanted to do so if they had had the option.

This example of a larger renovation shows that even major facade interventions can take place without compromising the building’s SAVE value if done with respect for the building’s original architecture and without radical changes to the facade facing the street. The measured energy consumption was 114 kWh/m² before the renovation. After the renovation, the EPC-reported consumption decreased to 89 kWh/m². Supplied with district heating from the Capitals Supply (HOFOR), which in 2023 emitted 35 g CO2 per kWh delivered, this means that the example of a larger renovation results in a total emission of 4 kg CO2 per square meter annually.

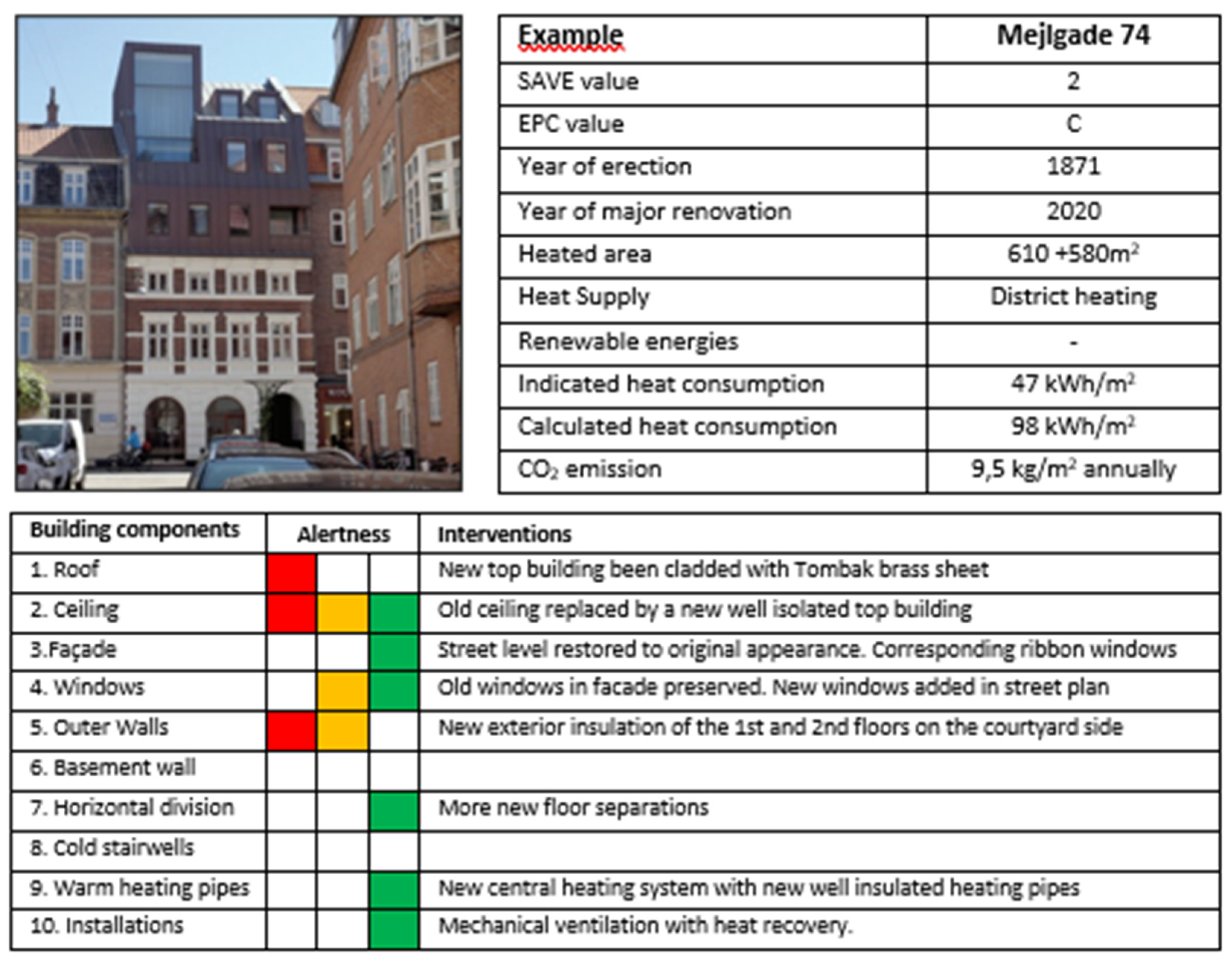

Mejlgade 74: A transformation. This apartment building, located in Aarhus, has undergone both renovation and transformation. Three additional floors in a modern style have been added on top of the old building. Before the transformation, the building had a SAVE value of 2 and an EPC label of C. After the transformation, the SAVE value of 2 was sustained, and the EPC label remained C.

Figure 9.

Mejlgade with information about the building and main interventions. Photo-credit: B2B Film.

Figure 9.

Mejlgade with information about the building and main interventions. Photo-credit: B2B Film.

The ground floor, which until the renovation was a shop front, has been restored to its original appearance and converted into an office. It lies in the middle of a row of historic buildings. Originally built in 1891, the apartment building formerly had 3 floors and now has 5 floors with a used attic. Today, it is subdivided into owner-occupied flats. The superstructure, which differs significantly in appearance from the rest of the building, was added in 2019. With the superstructure, three new floors have been added, complying with building regulations for insulation. The extension and rear facade are clad in tombak (a brass alloy). The rear facade has been re-insulated on the outside with facade panels of the same type as the new superstructure. The new windows in the facade are fitted with low-energy glazing. The municipality was active in the renovation process and called in their architecture panel, consisting of internal and external experts, to discuss the design of the renovation. This example of a transformative renovation shows that even major interventions in a property’s exterior architecture can be carried out if done with great architectural care. The reward has been that an old shop facade has been brought closer to its original expression, and the entire building has been harmonized with the rest of the streetscape. The present energy consumption is 98 kWh/m². An estimate of the former energy consumption is 250 kWh/m². By achieving an energy label of C, the building’s energy performance is now on par with newer properties. With heat supplied by Aarhus District Heating, this results in an operational CO2 emission (2022) of less than 10 kg/m² annually.

4. Discussion

In this section we discuss how our study can contribute to a future strategy that enables energy optimization of historic apartment buildings without compromising the historic and architectural value of the buildings.

Eriksson and Johansson argued for a more differentiated strategy towards energy optimization of historic buildings, given the heterogeneous composition of those buildings [

3]. We support this viewpoint, especially as our study shows some differentiation between municipalities with an urban and rural context, where municipalities with lower property prices and less renovation activity haven’t achieved the same progress in energy performance in the historic apartment buildings, as in larger, urban municipalities. In this question, it is important to distinguish between the role of the municipality, and the role of the market and the civic society; the local housing market actors create the changes in the historic building stock, and the municipalities can use different planning and regulation mechanisms to guide and steer the development. In the Danish planning system, it is the municipalities task to identify and protect the built heritage, including historic buildings. Although the energy optimization so far seems to have had limited negative effects on the historic building stock, there is a risk that an increasing focus on energy reductions and a general renovation activity in the existing building stock, will challenge the historic apartment buildings. As demonstrated in the three examples on renovation of historic buildings, some renovations (“step by step”) go under the radar of the municipalities, and there is no dialogue between the owner and the municipality before or after the renovation. Other types of renovations (“larger renovations” and “transformations” typically, however, require large municipal involvement, e.g. with subsidies, dialogue, building permission and architectural guidance, which enables the municipality to have some influence on the result, and protect the architecture and heritage of the historic buildings.

However, municipalities face several challenges:

- -

A lack of updated SAVE-registrations: Since the introduction of the SAVE system in Denmark in the 1990s, and the creation of several SAVE atlases for Danish towns and cities, the subsequent updating of SAVE registrations has been limited and inconsistent [

11].

- -

Formulation of Local Protection Plans: Giving SAVE registrations legal status requires local plans that outline specific protections for SAVE-registered buildings (typically only those with SAVE values of 1 or 2). This is a time-consuming activity that has only been partially implemented in Danish municipalities, and to varying degrees. It can also be challenging to precisely define in the plans what is allowed and what is not in relation to the buildings.

- -

Detection and regulation of simple improvements: Many simple energy optimization improvements do not require a building permit, making them difficult for municipalities to detect or regulate [

12]. Although such improvements might not harm the cultural and architectural heritage of the building, there is a possibility they could. To avoid this, municipalities strive to establish contact with owners when renovation projects are upcoming. This can be done by directly contacting owners of buildings where changes are anticipated or by using grants and subsidies for renovation, such as national urban regeneration subsidies or local funds for building retrofitting that owners can apply for. This provides the municipality with an opportunity to establish a dialogue with the owner. The renovation of Tårnborgvej in Frederiksberg is an example of this, where dialogue between the owner and the municipal architect led to many improvements in maintaining the architectural values and adapting changes to the original building and neighboring buildings (especially the insulation of the back facades). In Aarhus, the transformation of Mejlgade was carried out in close dialogue with the municipal administration, the owner, the consultant, and an external board of restoration experts, who together established the framework for the transformation. There are also examples where municipalities use subsidies to require owners to increase the EPC level by two steps (e.g., from E to C), and cases where municipalities have prevented external insulation of a historic building through dialogue with the owner, established when the owner applied for subsidies to renovate the building.

From this perspective, municipalities should enhance their legal options to intervene in the renovation of historic buildings by increasing their SAVE registrations and creating protective local plans. Several municipalities have already started upgrading the SAVE registers and are working on protective local plans, but in general, it is a slow process where the preparation of each plan can take several years. However, municipalities should also increase dialogue with local owners, for example, by offering subsidies for renovation, as well as working on upgrading and disseminating knowledge and competencies among owners and consultants. Additionally, updating the SAVE register, mapping historic buildings, and developing preservation plans should include dialogue and knowledge dissemination with the local civil and professional society, including building owners, users, consultants, craftsmen, and local preservation associations. This is in line with [

17] who argues for a more inclusive and participatory approaches in urban conservation and regeneration, suggesting that involving local communities could lead to better outcomes in terms of both heritage preservation and urban vitality.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that historic residential buildings perform similarly to other apartment buildings from the same period in terms of energy efficiency. This is surprising, as historic buildings are often considered to have poorer energy performance and higher energy consumption compared to “ordinary” buildings. The study reveals that the general energy performance level of historic apartment buildings in Denmark is quite high, with 46% of the buildings holding an EPC label of C. It is possible to renovate historic buildings to achieve a C label while maintaining their historic and architectural value. However, energy optimization can also potentially damage the architectural value of historic buildings; it depends on the ambitions and qualifications of the key actors in the renovation, as well as the building’s location, structure, and energy supply.

It is not possible to measure definitively if, and to what degree, the increased energy performance has influenced the architectural and historical values of all historic buildings. However, visual inspections of selected historic buildings, interviews with key actors, and case studies of historic building renovations indicate that this has not caused significant damage to the buildings’ architectural expression or cultural values. On the contrary, some historic buildings have benefitted architecturally from renovations, as they have been restored closer to their original status, for example, by restoring facades and changing windows to a more original style. Successful renovations have been characterized by collaboration between the owner, consultants, and the municipal building department.

In this light, there is significant potential for further energy optimization of historic buildings. This is also indicated in the EPC reports, which estimate that most historic buildings could achieve an EPC label of C with reasonable investments. However, the increased focus on energy efficiency also might bring forward solutions that challenge the historic value of buildings, such as solar panels on roofs or external insulation on gables and back facades. If such cases are managed solely by the owner, and the owner lacks the ambition or competence to respect historic values, the results can be problematic from an architectural perspective. Therefore, the increased focus on energy efficiency potentially represents a challenge for historic buildings and requires upgrading the qualifications for restoring historic buildings among owners, consultants, municipalities, and builders. Municipalities are traditionally seen as the central actors in this process, but as municipal departments have limited resources for managing individual cases and creating SAVE registrations and preservation plans, it is important to engage other central actors in respecting the architectural value of historic buildings when implementing energy efficiency initiatives.