Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

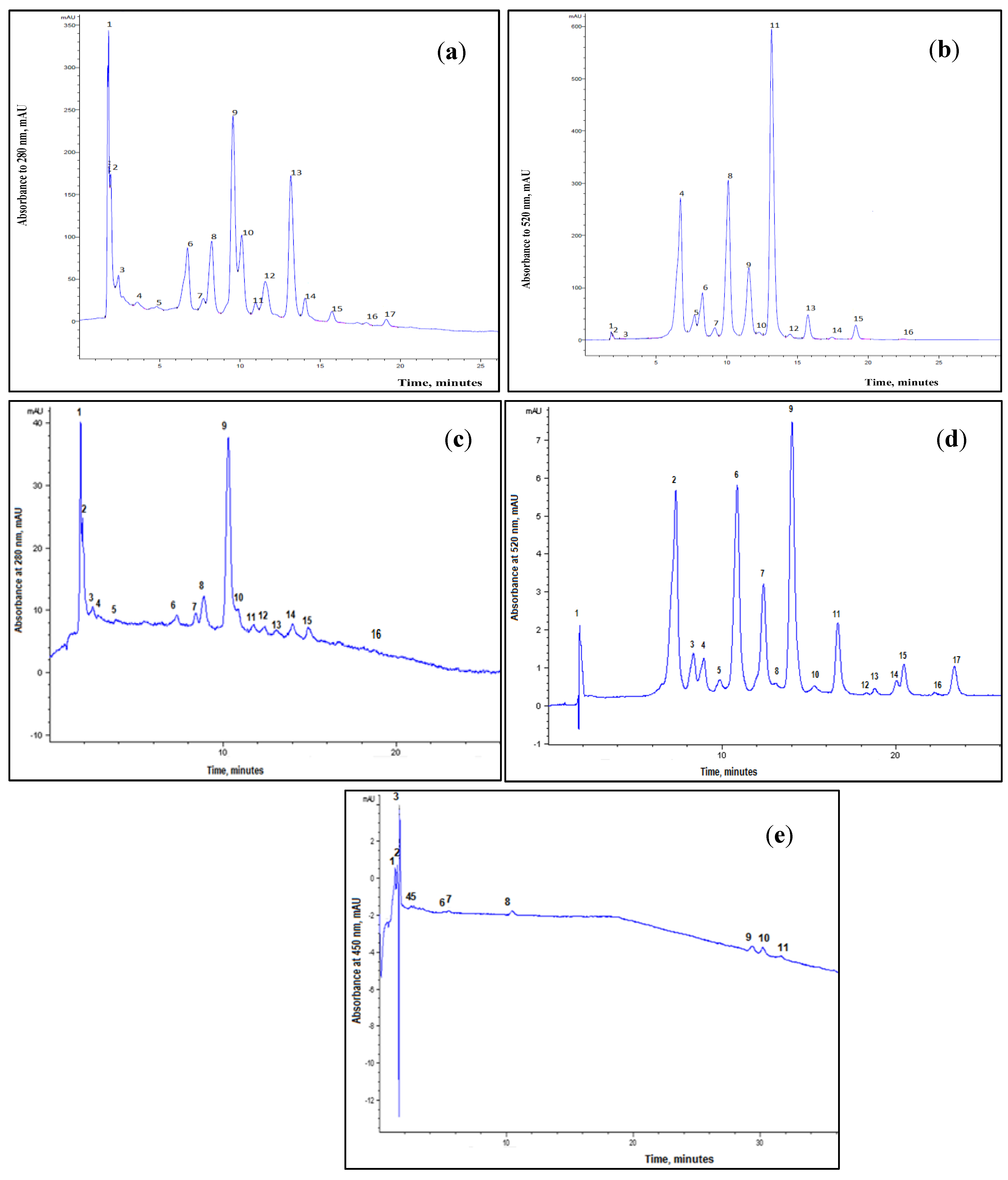

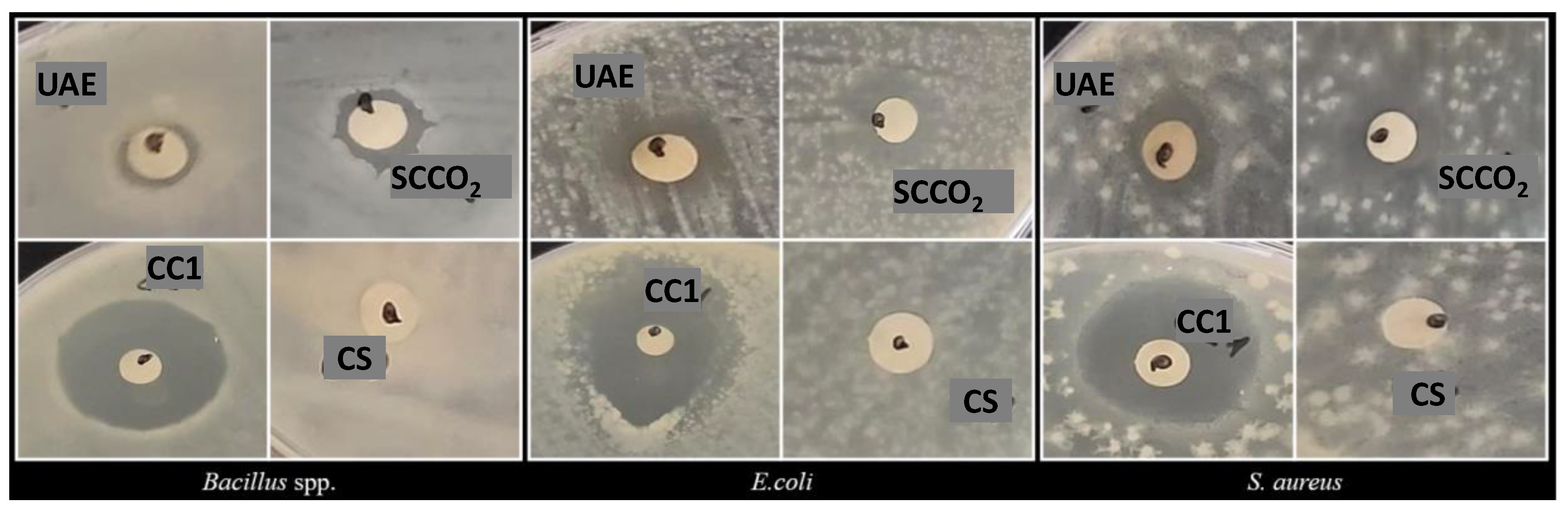

This research paper investigates the phytochemical profile, antioxidant activity, antidiabetic potential, and antibacterial activity of Myrtus communis berries. Two extraction methods were employed to obtain the extracts: solid-liquid ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) and supercritical CO2 extraction (SCCO2). The extracts were characterized using spectrophotometric methods and Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RT-HPLC). The UAE extract exhibited higher total flavonoid and anthocyanin content, while the SCCO2 extract prevailed in total phenolic content and antioxidant activity in the DPPH radical screening assay. RT-HPLC characterization identified and quantified several polyphenolic compounds. In the UAE extract, epigallocatechin was found in a concentration of 2656.24 ± 28.15 µg/g dry weight (DW). While in the SCCO2 extract, cafestol was the identified compound with the highest content at a level of 29.65 ± 0.03 µg/g DW. Both extracts contained several anthocyanin compounds, including cyanidin 3-O-glucoside chloride, cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside chloride, malvidin-3-O-glucoside chloride, pelargonidin 3-O-glucoside chloride, peonidin 3-O-glucoside chloride, and peonidin-3-O-rutinoside chloride. The antidiabetic potential was evaluated in vitro by measuring the inhibition of α-amylase from porcine pancreas (type I-A). The results highlighted the ability of myrtle berry extracts to inhibit α-amylase enzymatic activity, suggesting its potential as an alternative for controlling postprandial hyperglycemia. The UAE extract showed the lowest IC50 value among the two extracts, with an average of 8.37 ± 0.52 µg/mL DW. The antibacterial activity of the extracts was assessed in vitro against Bacillus spp., Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus using the Disk Diffusion Method. Both myrtle berry extracts exhibited similar antibacterial activity against the tested bacterial strains. The results support further investigation of myrtle berries extracts as a potential ingredient in functional food formulation, particularly due to its antioxidant, antidiabetic, and antibacterial properties.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials

2.2. Reagents

2.3. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction

2.4. Supercritical CO2 Extraction

2.5. Determination of Total Phenolic Content (TPC), Total Flavonoid Content (TFC), and Total Anthocyanins Content (TAC)

2.6. Antioxidant Activity

2.7. Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (RT-HPLC) Characterization

2.8. In Vitro Antidiabetic Activity

2.9. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity

2.10. Statistical Evaluation

3. Results

3.1. Extraction Yield and Global Characterization of the Myrtle Berries Extracts

3.2. RT-HPLC Characterization of the Myrtle Berries Extracts

3.3. Antidiabetic Activity of the Myrtle Berries Extracts

3.4. Antibacterial Activity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sumbul, S.; Ahmad, M.; Asif, M.; Akhtar, M. Myrtus Communis Linn. ─ A Review.; 2011. 1 December.

- Al-Snafi, A.E.; Teibo, J.O.; Shaheen, H.M.; Akinfe, O.A.; Teibo, T.K.A.; Emieseimokumo, N.; Elfiky, M.M.; Al-kuraishy, H.M.; Al-Garbeeb, A.I.; Alexiou, A.; et al. The Therapeutic Value of Myrtus Communis L.: An Updated Review. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. [CrossRef]

- Hennia, A.; Nemmiche, S.; Dandlen, S.; Miguel, M.G. Myrtus Communis Essential Oils: Insecticidal, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities: A Review. Journal of Essential Oil Research 2019, 31, 487–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medda, S.; Mulas, M. Fruit Quality Characters of Myrtle (Myrtus Communis L.) Selections: Review of a Domestication Process. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuberoso, C.I.G.; Melis, M.; Angioni, A.; Pala, M.; Cabras, P. Myrtle Hydroalcoholic Extracts Obtained from Different Selections of Myrtus Communis L. Food Chemistry 2007, 101, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashhadi, H.; Nourabi, A.; Mohammadi, M.; Tabibiazar, M.; Varvani Farahani, A. Incorporation of Myrtle Essential Oil into Hydrolyzed Ethyl Cellulose Films for Enhanced Antimicrobial Packaging Applications 2023.

- Zam, W.; Ali, A. Evaluation of Mechanical, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of Edible Film Containing Myrtle Berries Extract. The Natural Products Journal 2018, 8, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Zam, W.; Ibrahim, W. Formulation and Evaluation of Chewable Lozenges Containing Myrtle Berries, Cinnamon and Cloves for Oral Disinfection. 2022, 1. 1.

- De Luca, M.; Lucchesi, D.; Tuberoso, C.I.G.; Fernàndez-Busquets, X.; Vassallo, A.; Martelli, G.; Fadda, A.M.; Pucci, L.; Caddeo, C. Liposomal Formulations to Improve Antioxidant Power of Myrtle Berry Extract for Potential Skin Application. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haririan, Y.; Asefnejad, A.; Hamishehkar, H.; Farahpour, M.R. Carboxymethyl Chitosan-Gelatin-Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles Containing Myrtus Communis L. Extract as a Novel Transparent Film Wound Dressing. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 253, 127081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wissam, Z. WOUND DRESSINGS UPLOADED WITH MYRTLE BERRIES EXTRACT AND NIGELLA SATIVA HONEY. In Proceedings of the Universal Journal of Pharmaceutical Research; May 15 2018; Vol. 3; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Correddu, F.; Fancello, F.; Chessa, L.; Atzori, A.S.; Pulina, G.; Nudda, A. Effects of Supplementation with Exhausted Myrtle Berries on Rumen Function of Dairy Sheep. Small Ruminant Research 2019, 170, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbaghi, M.M.; Fadaei, M.S.; Soleimani Roudi, H.; Baradaran Rahimi, V.; Askari, V.R. A Review of the Biological Effects of Myrtus Communis. Physiological Reports 2023, 11, e15770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, A.M.; Kumar, P.; Ismail-Fitry, M.R.; Jusoh, S.; Ab Aziz, M.F.; Sazili, A.Q. Green Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Plant Biomass and Their Application in Meat as Natural Antioxidant. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; Sit, N. Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Plant Materials Using Combination of Various Novel Methods: A Review. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2022, 119, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alara, O.R.; Abdurahman, N.H.; Ukaegbu, C.I. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds: A Review. Current Research in Food Science 2021, 4, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bitwell, C.; Indra, S.S.; Luke, C.; Kakoma, M.K. A Review of Modern and Conventional Extraction Techniques and Their Applications for Extracting Phytochemicals from Plants. Scientific African 2023, 19, e01585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, R.; Barbosa, A.; Advinha, B.; Sales, H.; Pontes, R.; Nunes, J. Green Extraction Techniques of Bioactive Compounds: A State-of-the-Art Review. Processes 2023, 11, 2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, K.S.; Aznar, R.; O’Donnell, C.; Tiwari, B.K. Ultrasound Technology for the Extraction of Biologically Active Molecules from Plant, Animal and Marine Sources. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2020, 122, 115663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, I.; Khan, S.; Aladel, A.; Dar, A.H.; Adnan, M.; Khan, M.I.; Mahgoub Awadelkareem, A.; Ashraf, S.A. Recent Insights into Green Extraction Techniques as Efficient Methods for the Extraction of Bioactive Components and Essential Oils from Foods. CyTA - Journal of Food 2023, 21, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuo, S.C.; Nasir, H.M.; Mohd-Setapar, S.H.; Mohamed, S.F.; Ahmad, A.; Wani, W.A.; Muddassir, Mohd. ; Alarifi, A. A Glimpse into the Extraction Methods of Active Compounds from Plants. Critical Reviews in Analytical Chemistry 2022, 52, 667–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essien, S.O.; Young, B.; Baroutian, S. Recent Advances in Subcritical Water and Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Plant Materials. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2020, 97, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medda, S.; Fadda, A.; Dessena, L.; Mulas, M. Quantification of Total Phenols, Tannins, Anthocyanins Content in Myrtus Communis L. and Antioxidant Activity Evaluation in Function of Plant Development Stages and Altitude of Origin Site. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalcea, L.; Turturică, M.; Cucolea, E.I.; Dănilă, G.-M.; Dumitrașcu, L.; Coman, G.; Constantin, O.E.; Grigore-Gurgu, L.; Stănciuc, N. CO2 Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Oleoresins from Sea Buckthorn Pomace: Evidence of Advanced Bioactive Profile and Selected Functionality. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, E.; Raofie, F.; Najafi Mashkouri, N. Application of response surface methodology and central composite design for the optimisation of supercritical fluid extraction of essential oils from Myrtus communis L. leaves. Food Chemistry, 1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Cebola, M.-J.; Oliveira, M.C.; Bernardo-Gil, M.G. Supercritical Fluid Extraction vs Conventional Extraction of Myrtle Leaves and Berries: Comparison of Antioxidant Activity and Identification of Bioactive Compounds. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2016, 113, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P; Mauricio Muchagato E.; Duarte M.P.; Lima K.; Fernandes A.; Bernardo-Gil G.; Cebola M.J. Potential of supercritical fluid myrtle extracts as an active ingredient and co-preservative for cosmetic and topical pharmaceutical applications. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy, 1007; 39. [CrossRef]

- Radzali Azfar, S.; Markom, M.; Md Saleh, N. Co-Solvent Selection for Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) of Phenolic Compounds from Labisia pumila. Molecules 2020, 25, 5859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoica, F.; Condurache, N.N.; Horincar, G.; Constantin, O.E.; Turturică, M.; Stănciuc, N.; Aprodu, I.; Croitoru, C.; Râpeanu, G. Value-Added Crackers Enriched with Red Onion Skin Anthocyanins Entrapped in Different Combinations of Wall Materials. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yangui, I.; Younsi, F.; Ghali, W.; Boussaid, M.; Messaoud, C. Phytochemicals, Antioxidant and Anti-Proliferative Activities of Myrtus Communis L. Genotypes from Tunisia. South African Journal of Botany 2021, 137, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem Cyanidin 3-Glucoside Available online:. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/12303220 (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Mërtiri, I.; Păcularu-Burada, B.; Stănciuc, N. Phytochemical Characterization and Antibacterial Activity of Albanian Juniperus Communis and Juniperus Oxycedrus Berries and Needle Leaves Extracts. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serea, D.; Condurache, N.N.; Aprodu, I.; Constantin, O.E.; Bahrim, G.-E.; Stănciuc, N.; Stanciu, S.; Rapeanu, G. Thermal Stability and Inhibitory Action of Red Grape Skin Phytochemicals against Enzymes Associated with Metabolic Syndrome. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannan, A.; Asghar, S.; Tahir, N.; Ikram Ullah, M.; Ahmed, I.; Aneela, S.; Hussain, S. Antibacterial Effect of Mango (Mangifera Indica Linn.) Leaf Extract against Antibiotic Sensitive and Multi-Drug Resistant Salmonella Typhi. Pakistan journal of pharmaceutical sciences 2013, 26, 715–719. [Google Scholar]

- Masota, N.E.; Vogg, G.; Ohlsen, K.; Holzgrabe, U. Reproducibility Challenges in the Search for Antibacterial Compounds from Nature. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavya, M.L.; Chandu, A.G.S.; Devi, S.S.; Quirin, K.-W.; Pasha, A.; Vijayendra, S.V.N. In-Vitro Evaluation of Antimicrobial and Insect Repellent Potential of Supercritical-Carbon Dioxide (SCF-CO2) Extracts of Selected Botanicals against Stored Product Pests and Foodborne Pathogens. J Food Sci Technol 2020, 57, 1071–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Cebola, M.-J.; Oliveira, M.C.; Bernardo Gil, M.G. Antioxidant Capacity and Identification of Bioactive Compounds of Myrtus Communis L. Extract Obtained by Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction. J Food Sci Technol 2017, 54, 4362–4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babou, L.; Hadidi, L.; Grosso, C.; Zaidi, F.; Valentão, P.; Andrade, P.B. Study of Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Myrtle Leaves and Fruits as a Function of Maturation. Eur Food Res Technol 2016, 242, 1447–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerkovic, I.; Radonic, A.; Borcic, I. Comparative Study of Leaf, Fruit and Flower Essential Oils of Croatian Myrtus Communis (L.) During a One-Year Vegetative Cycle. Journal of Essential Oil Research 2002, 14, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amensour, M.; Sendra, E.; Abrini, J.; Bouhdid, S.; Pérez-Alvarez, J.A.; Fernández-López, J. Total Phenolic Content and Antioxidant Activity of Myrtle ( Myrtus Communis ) Extracts. Natural Product Communications 2009, 4, 1934578X0900400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curiel, J.A.; Pinto, D.; Marzani, B.; Filannino, P.; Farris, G.A.; Gobbetti, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Lactic Acid Fermentation as a Tool to Enhance the Antioxidant Properties of Myrtus Communis Berries. Microbial Cell Factories 2015, 14, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, B.; Oba, S.; Karaman, K.; Arici, M.; Sagdic, O. Comparison of Different Solvent Types for Determination Biological Activities of Myrtle Berries Collected from Turkey. Quality Assurance and Safety of Crops & Foods 2014, 6, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Urso, G.; Sarais, G.; Lai, C.; Pizza, C.; Montoro, P. LC-MS Based Metabolomics Study of Different Parts of Myrtle Berry from Sardinia (Italy). JBR 2017, 7, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antony, A.; Farid, M. Effect of Temperatures on Polyphenols during Extraction. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alappat, B.; Alappat, J. Anthocyanin Pigments: Beyond Aesthetics. Molecules 2020, 25, 5500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idham, Z.; Putra, N.R.; Aziz, A.H.A.; Zaini, A.S.; Rasidek, N.A.M.; Mili, N.; Yunus, M.A.C. Improvement of Extraction and Stability of Anthocyanins, the Natural Red Pigment from Roselle Calyces Using Supercritical Carbon Dioxide Extraction. Journal of CO2 Utilization 2022, 56, 101839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, G.; Kermanshahi Pour, A. Extraction of Anthocyanins from Haskap Berry Pulp Using Supercritical Carbon Dioxide: Influence of Co-Solvent Composition and Pretreatment. LWT 2018, 98, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paes, J.; Dotta, R.; Barbero, G.F.; Martínez, J. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds and Anthocyanins from Blueberry (Vaccinium Myrtillus L.) Residues Using Supercritical CO2 and Pressurized Liquids. The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2014, 95, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Bai, Y.; Jin, Z.; Svensson, B. Food-Derived Non-Phenolic α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitors for Controlling Starch Digestion Rate and Guiding Diabetes-Friendly Recipes. LWT 2022, 153, 112455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashtoh, H.; Baek, K.-H. New Insights into the Latest Advancement in α-Amylase Inhibitors of Plant Origin with Anti-Diabetic Effects. Plants 2023, 12, 2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toauibia, M. Antimicrobial Activity of the Essential Oil of Myrtus Communis L Berries Growing Wild in Algeria. J. Fundam and Appl Sci. 2015, 7, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabri, M.-A.; Rtibi, K.; Ben-Said, A.; Aouadhi, C.; Hosni, K.; Sakly, M.; Sebai, H. Antidiarrhoeal, Antimicrobial and Antioxidant Effects of Myrtle Berries (Myrtus Communis L.) Seeds Extract. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2016, 68, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| UAE | SCCO2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Extraction Yield (%) | 62.84 | 0.54 |

| TPC (mg GAE/g DW) | 5.57 ± 0.13 B | 11.59 ± 0.12 A |

| TFC (mg QE/g DW) | 4.13 ± 0.67 A | 1.09 ± 0.18 B |

| TAC (mg C3G/g DW) | 2.17 ± 0.05 | n.d. |

| DPPH (mg TE/g DW) | 13.64 ± 1.91 B | 21.81 ± 0.31 A |

| Identified Compounds | UAE | SCCO2 |

|---|---|---|

| Phenolic acids | ||

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 24.00 ± 0.03 G | n.d. |

| Caffeic acid | 0.63 ± 0.03 R | n.d. |

| Ferulic acid | 3.69 ± 0.31 M | 0.30 ± 0.03 I |

| Gallic acid | 11.64 ± 0.03 I | 1.70 ± 0.73 B |

| Protocatechuic acid | 24.45 ± 0.01 F | n.d. |

| Sinapic acid | 2.17 ± 0.10 P | 1.29 ± 0.14 C |

| Terpenoid | ||

| Cafestol | 256.92 ± 5.33 B | 29.65 ± 0.03 A |

| Flavonoid | ||

| Apigenin | 3.73 ± 0.03 L | n.d. |

| Epicatechin | 14.39 ± 0.01 H | n.d. |

| Epicatechin gallate | 79.73 ± 0.04 C | n.d. |

| Epigallocatechin | 2656.24 ± 28.15 A | n.d. |

| Naringin | 7.00 ± 0.04 J | n.d. |

| Quercetin | 0.66 ± 0.16 Q | 0.60 ± 0.03 F |

| Rutin trihydrate (Quercetin-3-rutinoside trihydrate) |

25.55 ± 0.49 E | n.d. |

| Anthocyanins | ||

| Cyanidin 3-O-glucoside chloride (Kuromanin chloride) |

3.94 ± 0.01 K | 0.41 ± 0.01 H |

| Cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside chloride (Keracyanin chloride) |

36.09 ± 0.07 D | 0.62 ± 0.01 E |

| Malvidin-3-O-glucoside chloride (Oenin chloride) |

n.d. | 0.66 ± 0.04 D |

| Pelargonidin 3-O-glucoside chloride (Callistephin chloride) |

n.d. | 0.55 ± 0.11 G |

| Peonidin 3-O-glucoside chloride | 3.44 ± 1.36 N | n.d. |

| Peonidin-3-O-rutinoside chloride | 3.05 ± 0.01 O | n.d. |

| Carotenoids | ||

| Zeaxanthin | n.d. | 0.28 ± 0.02 J |

| µg/mL DW | UAE | SCCO2 |

|---|---|---|

| 3.33 | 21.32 ± 4.63 A | 16.69 ± 2.00 A |

| 6.66 | 36.74 ± 0.92 A | 19.86 ± 4.14 A |

| 10.00 | 64.59 ± 2.19 A | 22.25 ± 0.97 B |

| 13.33 | 91.98 ± 1.47 A | 26.80 ± 2.30 B |

| 16.66 | 96.30 ± 5.64 A | 31.17 ± 1.63 B |

| IC50 | 8.37 ± 0.52 | 27.27 ± 1.31 |

| Diameter of Inhibition Zone (DIZ mm) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus spp. | E. coli | S. aureus | |

| UAE | 9.00 ± 0.02 C, a | 10.50 ± 0.71 B, a | 12.00 ± 2.82 A, a |

| SCCO2 | 11.50 ± 0.71 C, a | 13.00 ± 0.03 A, a | 12.00 ± 1.41 B, a |

| Ciprofloxacin | 25.00 ± 0.01 | 35.00 ± 0.01 | 20.00 ± 0.03 |

| Solvent | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).