1. Introduction

The growing demand for sustainable ingredients has led the food industry to explore plant-based alternatives to animal-derived proteins. Aquafaba, derived from the Latin words “aqua” (water) and “faba” (bean), is the cooking water from legumes, particularly chickpeas (

Cicer arietinum L.), and has gained popularity as a substitute for egg whites in sauces, foams, and baked goods due to its foaming and emulsifying properties [

1,

2,

3]. As a novel natural food additive, aquafaba is expected to boost demand for legumes and reduce wastewater generated from bean processing [

3].

Chickpea, an annual herbaceous legume, is a rich source of proteins, carbohydrates (primarily starch and fiber), minerals, and vitamins. The protein composition includes 8–12% albumin, 53–60% globulin, 19–24% glutelin, and 3–6% prolamin [

4]. Soaking and cooking chickpeas facilitate water absorption, leading to protein hydration, denaturation, starch gelatinization, solubilization, and depolymerization [

3,

5]. Prolonged cooking causes the starch to expand and gelatinize, which disrupts the seed coat due to internal pressure. Consequently, the leached components in the cooking water include not only proteins and sugars but also undissolved components such as starch [

6,

7,

8]. In other words, various components elute into the boiling water during cooking.

When preparing an emulsion with a protein acting as a surfactant, the protein reduces the interfacial tension by adsorbing onto the surface of dispersed particles, thereby stabilizing the emulsion by forming a robust adsorption film (Wilde & Clarke, 1996; Stantiall et al., 2018) [

9,

10]. Surfactants commonly found in food include casein and whey protein from milk, lecithin and globulin from soybeans, and lecithin and ovalbumin from eggs, all of which are known for their foaming and emulsifying properties [

11]. Aquafaba proteins primarily consist of low-molecular-weight species (≤25 kDa), likely albumins, which are effective at forming stable foams [

1,

12]. However, aquafaba’s protein content is relatively low at approximately 1.5% [

1,

13]. Therefore, the combination of low-molecular-weight protein and carbohydrates likely confers the foaming and emulsifying properties seen in aquafaba. Additionally, components such as cellulose, pectin, and gelatinized starch may enhance these properties by increasing viscosity and providing structural support [

14,

15].

Methods to enhance the functionality of aquafaba have been reported, such as extending the boiling time or reducing the water content to increase the concentration of leached components [

14,

16]. However, aquafaba is a byproduct of bean cooking, so excessive focus on aquafaba’s quality may compromise the cooked beans. Furthermore, detailed investigations on the components contributing to aquafaba’s foaming capacity are scarce. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to develop a method to enhance aquafaba’s foaming and emulsifying properties without negatively affecting the quality of the cooked beans. Additionally, we sought to improve aquafaba functionality by leveraging the high thermal stability of its proteins through reheating to adjust the concentration. Finally, we examined the components that contributed to enhanced functionality through enzymatic treatments and molecular size analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Dried chickpeas were purchased from bean stores. Beans with visible blemishes were removed prior to use. Fresh eggs were purchased from a grocery store and stored at 4°C until use. All enzymes were purchased from Amano Enzymes (Nagoya, Japan). Thamoase PC10F was used as a protease agent, pectinase G “Amano” was used as a pectinase agent, and Gluczyme NL4.2 was used as a glucoamylase.

2.2. Aquafaba Preparation

The cooking method for the chickpeas was partially modified from that described by Stantiall et al. [

10]. Dry chickpea seeds (~200 g) were washed and rehydrated by soaking in distilled water at a ratio of 1:4 (w/w) for 16 h at 4°C. The soaked chickpeas were cooked in boiling water at a 3:1 wt ratio (water/chickpeas) for 40 min. After cooking, the water and chickpeas were transferred to a glass bowl and stored at 4 °C for 24 h. Then, the aquafaba was separated from the cooked grains using a strainer. The average hardness of the chickpeas after cooking was 3.53 N, which is suitable for consumption [

17].

2.3. Reheating of Aquafaba

We reheated aquafaba to improve its foaming and emulsification properties. The degree of reheating was divided into eight levels depending on the concentration: 100%, 90%, 80%, 70%, 60%, 50%, 40%, and 30% (w/w), with the aquafaba before reheating being 100%.

2.4. Color

The color intensity was measured using a spectrophotometer (CM-700d, KONICA MINOLTA, Tokyo, Japan) using L*, a*, and b* values, according to the CIE color scale. L* represents brightness from 0 (black) to 100 (white). The other two coordinates represent redness (+a*) to greenness (–a*), and yellowness (+b*) to blueness (–b*). The color change (ΔE) was determined to compare the color of the reheated aquafaba with that of the untreated aquafaba. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.5. Viscosity

The viscosity of the aquafaba was measured using a rotational viscometer (VISCO; Atago Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Aquafaba was dispensed in a glass beaker (15 mL; Atago Co., Ltd.). Measurements were conducted under spindle A2 conditions, a rotational speed of 150 rpm, and sample temperatures of 5°C, 25°C, and 40°C, with data collected 1 min after the spindle rotational speed was stabilized. The sample temperature during viscosity measurement was controlled by a Temp Controller 6900 (Atago Co., Ltd.) attached to the viscometer.

2.6. Foaming Properties

The foaming properties were evaluated by measuring foaming capacity and foam stability. Foam capacity was assessed in terms of overrun, which represents the expansion rate of the whipped foam. Foam stability was assessed by measuring the weight of foam retained after leaving it at 5°C for 16 h, along with the amount of liquid drainage. Aquafaba samples were carefully poured into a 30 mL measuring cup and weighed. Subsequently, the samples were whipped at a speed setting of 3 (1,050 rpm) for 2 min using a hand mixer (Dretec Co., Ltd., HM-702). The resulting foams were then transferred back into a 30 mL measuring cup, leveled off gently with a spatula, and reweighed. The percentage of foam expansion was calculated using the following equation (1):

where

W0 is the weight of the aquafaba before homogenization, and

Wf30 is the weight of the whipped foam in the 30 mL cup after homogenization.

To quantify foam stability, the foam was carefully transferred to a plastic funnel placed on top of a 50 mL graduated cylinder immediately after the foaming process. The weight of the retained foam and the drained liquid was recorded after leaving it at 5°C for 16 h. The retained foam weight was calculated using the following formula (2):

where

Vl0 is the liquid volume at time 0,

Vlt is the liquid volume after 16 h, and

Vli is the initial sample volume (30 mL). Analyses of the foaming ability and foam stability were performed in triplicate.

2.7. Emulsifying Properties

The emulsifying properties were assessed following the methodology of Mustafa et al. [

1], with partial adaptations. Emulsions were prepared by mixing 15 mL of untreated or concentrated aquafaba oil and 15 mL of canola oil (Nissin Oil Mills, Tokyo, Japan) for 1 min in a homogenizer (Bio-Gen PRO200, PRO Scientific Inc., Oxford, CT, USA) at 5000 rpm. Subsequently, the resultant emulsion was quantitatively transferred into a 100 mL graduated cylinder and stored at 25°C (room temperature). The emulsion stability was evaluated by measuring the amount of liquid separated from the emulsion after 7 days. Results represent the averages of three independent replicates.

Emulsifying capacity was calculated using equation (3):

where

Ve0 is the emulsion volume at time 0, and

Vet is the volume of the emulsion after time t.

For comparative purposes, the emulsifying capacity of egg yolk at 5°C was also ascertained, given its extensive use in emulsions such as mayonnaises.

2.8. Proximate Analysis

The general nutritional ingredients of chickpeas, cooked chickpeas, aquafabas, and concentrated aquafabas were analyzed. Moisture, crude protein, crude fat, ash, and crude fiber contents were determined according to the standard methods described by the AOAC [

18]. Moisture content was measured using an atmospheric pressure drying method (135°C). The crude protein content was determined using the Kjeldahl method; the nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor was 6.25. The crude fat content was determined using chloroform-methanol extraction. Dietary fiber content was determined using the Prosky method. The carbohydrate content was calculated using the following equation: (4) (Monro & Burlingame [

19]):

2.9. Enzyme Treatment

The treatment conditions for each enzyme were Tests 1 and 2, in which pH, temperature, and reaction time were varied. Test 1: Aquafaba was prepared at the optimal pH for each enzyme (protease, pH 7.5; pectinase, pH 4.5; and glucoamylase, pH 4.5), mixed with 1% enzyme per dry matter of aquafaba, and adjusted to the optimum temperature. The reaction was carried out for 2 h at various temperatures (protease: 55°C, pectinase: 45°C, and glucoamylase: 55°C). Test 2: As a control, after adjusting the pH of the aquafaba, the foaming and emulsifying properties were measured under the same conditions as in Test 1 without the addition of enzymes.

2.10. Molecular Size Analysis and Qualitative Testing of Proteins and Carbohydrates

The remaining liquid ratio of 70% aquafaba was centrifuged (13,000 rpm, 10 min, 25°C) and separated into supernatant and precipitate; 0.5 mL of ion-exchanged water was added to the precipitate obtained from 1 mL of aquafaba and used for testing the bubbling properties. Then, 0.5 mL of the supernatant was filtered through a 100 kDa ultrafiltration filter (Amicon Ultra 0.5 mL, Merck Millipore Ltd., Tullagreen, Ireland) and centrifuged (10,000 rpm, 10 min, 25°C) to obtain the eluate. Then, 0.5 mL of the eluate was filtered through a 50 kDa ultrafiltration filter (Amicon Ultra 0.5 mL, Merck) and centrifuged (10,000 rpm, 10 min, 25°C). The resultant eluate was similarly filtered through a 30 kDa ultrafiltration filter (Amicon Ultra 0.5 mL, Merck) and 10 kDa ultrafiltration filter (Amicon Ultra 0.5 mL, Merck). Then, 0.5 mL of these final eluates was placed in a 2 mL tube, stirred vigorously for 1 min, and then allowed to stand at room temperature (25°C). The height of the bubbles was measured every time, and their respective volumes were calculated.

Protein identification was performed using ninhydrin. To 100 μL of each fraction, 100 μL of a 2% ninhydrin solution (FUJIFILM, Tokyo, Japan) was added and mixed. The mixture was then heated at 100°C for 5 min, and the resulting solution was examined for blue coloration.

Carbohydrate identification was performed using anthrone-sulfuric acid. To 100 μL of each fraction, 100 μL of a 10 mmol/L anthrone-sulfuric acid solution (FUJIFILM) was added and mixed. The mixture was then heated at 100°C for 10 min, and the resulting solution was examined for blue coloration.

2.11. Statistics

All data are presented as the mean ± SD. Significant differences in values were analyzed via one-way analysis of variance using SPSS statistical software (ver. 27.0, IBM, USA). Tukey’s and Bonferroni’s methods were used for multiple comparisons, with the statistical significance level set at p < 0.05. All measurements were performed at least in triplicate.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Foaming Properties Depend on Whipping Temperature

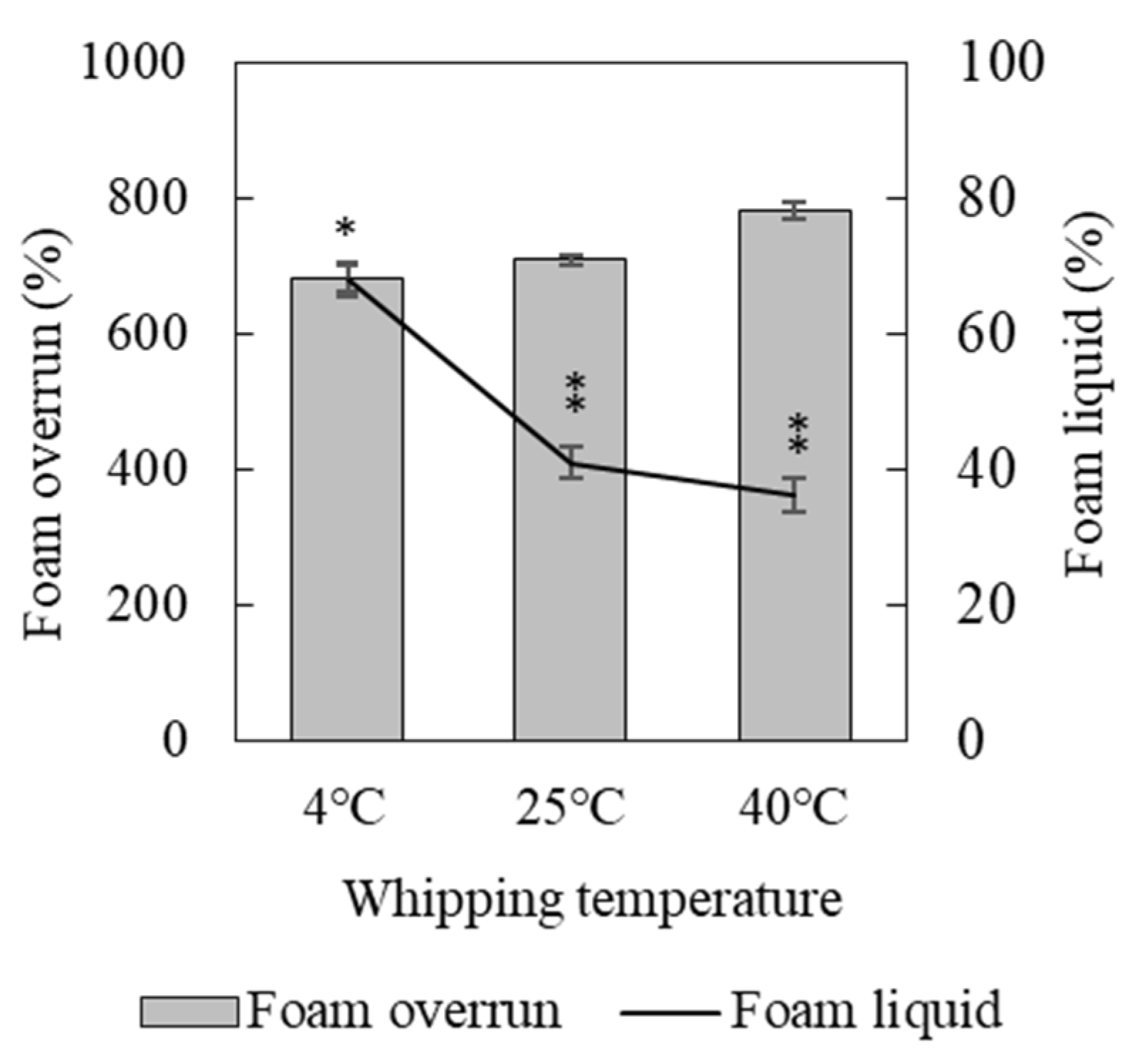

Temperature significantly influences the foaming properties of proteins, making it essential to investigate its impact on aquafaba. In this study, we examined the foaming ability and stability of aquafaba whipped at 4℃, 25℃, and 40℃. Foaming stability was evaluated based on the drainage volume of foam liquid after 16 h.

As shown in

Figure 1, the foaming ability across all temperatures was exceptionally high, with overruns ranging from 700% to 800%, and no significant differences were observed. However, the drainage volume revealed notable temperature-dependent variations. At 4℃, 68.1% of the foam liquid drained, whereas at 25℃ and 40℃, drainage was significantly reduced to approximately 40%. These results indicate that although aquafaba exhibits excellent foaming ability at both high and low temperatures, whipping at room temperature or around 40℃ results in more stable foams compared to whipping at lower temperatures.

In contrast to egg whites, which are commonly whipped at low temperatures to enhance foam stability, aquafaba demonstrates superior stability at higher temperatures. For egg whites, the foaming process benefits from increased temperatures, as reduced viscosity and surface tension promote foam formation, but the resulting foams tend to collapse more easily due to weakened protein structures [

20]. This is primarily attributed to ovoglobulin and ovomucin, which form thin, stabilizing films around air bubbles under cold conditions. However, our findings suggest that the factors contributing to aquafaba’s foam stability differ from those affecting egg whites. The non-protein components in aquafaba, such as polysaccharides and pectins, may play a critical role in stabilizing the foam by increasing viscosity and elasticity, thus preventing bubble collapse [

21]. Additionally, plant-derived proteins and surface-active compounds like saponins might further enhance the foaming properties of aquafaba, with their effects potentially optimized around 40℃ [

22].

These findings highlight the importance of non-protein components in the foaming stability of aquafaba and the significant role of temperature in modulating their physicochemical properties. Consequently, all subsequent foaming experiments in this study were conducted at 25℃ to ensure consistent and optimal conditions.

3.2. Enhanced Foaming and Emulsifying Properties by Reheating

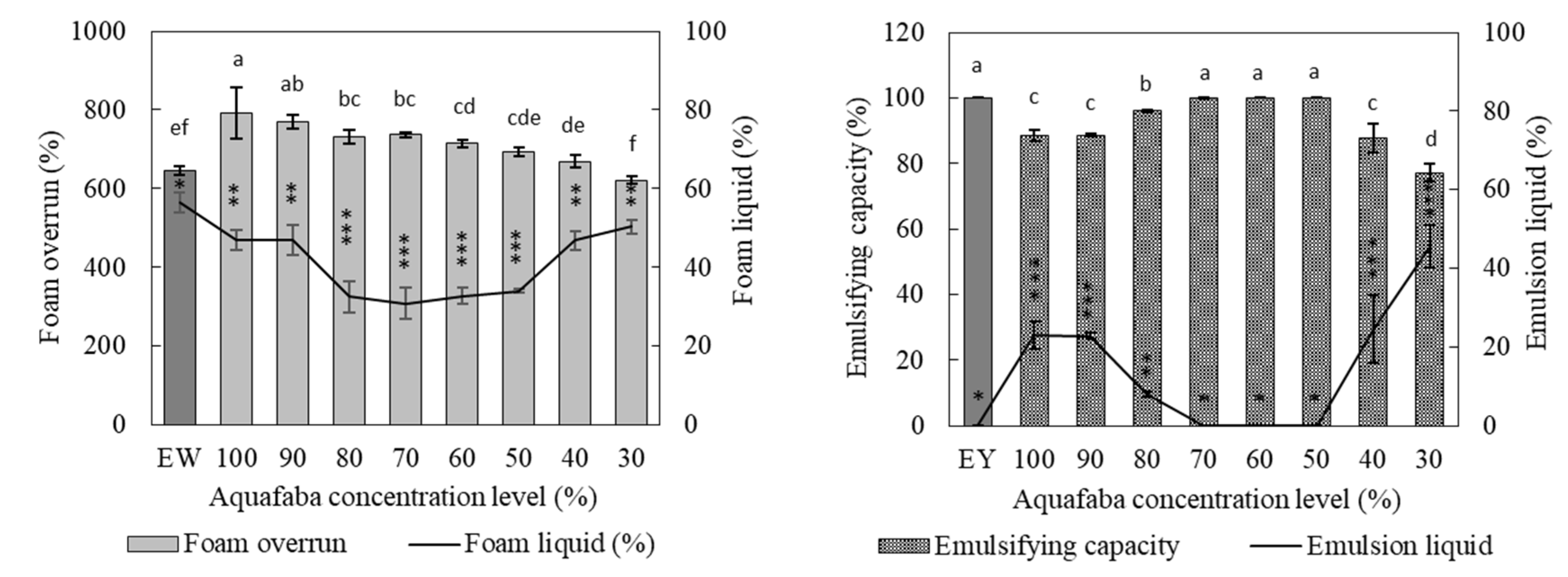

We investigated the effect of reheating aquafaba on its foaming and emulsifying properties. The degree of reheating was adjusted by gradually reducing the liquid volume of aquafaba to achieve specific remaining liquid ratios: 90%, 80%, 70%, 60%, 50%, 40%, and 30%, with the control set at 100%. Lower remaining liquid ratios correspond to higher concentrations of solid components due to reheating.

As shown in

Figure 2, the foaming ability of reheated aquafaba, except for the 30% concentration, exceeded that of egg whites at all remaining liquid ratios. However, foaming ability decreased as concentration increased, exhibiting an inverse relationship with the remaining liquid ratio. Foam stability, evaluated by drainage volume after 24 h, was consistently superior in aquafaba compared to that in egg whites across all ratios. Notably, the 80–50% range exhibited the least drainage, suggesting this concentration range is optimal for foam stability. Emulsifying properties were also enhanced at all remaining liquid ratios, with emulsification values reaching 100% at concentrations of 70%, 60%, and 50%. Emulsions in these concentrations remained stable without phase separation even after one week. These results indicate that reheating significantly enhances the functional properties of aquafaba, particularly within the 70–50% concentration range.

The observed improvements in foaming and emulsifying properties can be attributed to structural changes in aquafaba components induced by reheating. Protein denaturation during reheating likely exposes hydrophobic regions, increasing surface activity and facilitating the formation of stable foam and emulsification films [

23]. Simultaneously, aggregated proteins may form dense interfacial films, further stabilizing the structure. Polysaccharides, known for their viscosity and gel-forming capabilities, likely contribute to foam and emulsion stability by interacting with proteins and reinforcing the structural integrity of these systems [

3].

The reheating process concentrates these functional components, promoting improved foam stability and suppressing phase separation in emulsions. These findings demonstrate that reheating enhances aquafaba’s foaming and emulsifying properties, offering new insights into the role of protein–polysaccharide interactions in functional ingredient applications.

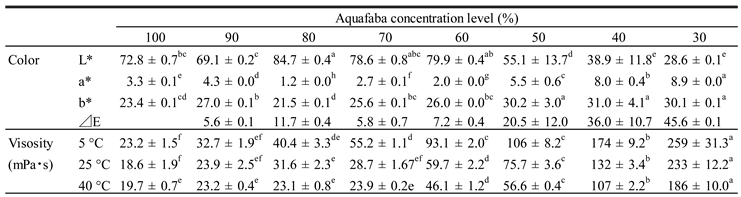

3.3. Color Value and Viscosity After Reheating

Reheating-induced changes in the color and viscosity of aquafaba were analyzed to assess the impact of chemical reactions and component interactions on its physical properties. As shown in

Table 1, the L* value (lightness) decreased with increasing concentration, whereas the a* (redness) and b* (yellowness) values increased. This indicates that reheating gradually transformed aquafaba from a yellowish, transparent liquid into a brownish liquid. These color changes were attributed to the Maillard reaction between proteins and reducing sugars, which accelerates under higher temperatures or longer cooking time [

25]. In the present study, the lower the remaining liquid ratio, the longer the cooking time, which likely resulted in more pronounced color changes. This indicates that aquafaba, containing both proteins and sugars, undergoes the Maillard reaction during reheating, leading to the observed browning as the reaction progresses.

The viscosity of aquafaba varied with temperature and concentration. At the same remaining liquid ratio, viscosity was highest at 5℃ and lowest at 40℃, likely due to reduced molecular motion and stronger intermolecular interactions at lower temperatures. As the concentration increased, viscosity also rose, with aquafaba boiled down to 30% forming a gel-like consistency. This thickening phenomenon can be attributed to the accumulation of Maillard reaction products and aggregation of proteins and polysaccharides, which increase molecular weight and enhance solution viscosity [

26]. High-molecular-weight Maillard reaction products also exhibit dietary fiber-like properties, contributing to gelation and viscosity enhancement [

25]. Prior to reheating, the viscosity of aquafaba was approximately 1/5th that of egg whites (data not shown). To achieve a viscosity comparable to that of egg whites, aquafaba required concentration to 40–50%. However, as shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, sufficient foam formation was achieved even before reheating. This suggests that the interactions among aquafaba components, rather than viscosity alone, play a critical role in its foaming properties [

21,

27].

Reheating and concentration have been shown to influence aquafaba’s functionality by altering its physical properties, such as color and viscosity. As discussed in

Section 3.2, protein denaturation and Maillard reaction products contribute significantly to the stability of foams and emulsions. Additionally, polysaccharides, which are abundant in aquafaba, play a key role in viscosity enhancement and gel formation, further supporting foam and emulsion stability [

3]. The changes in color and viscosity observed during reheating, therefore, reflect these underlying molecular interactions and their impact on aquafaba’s overall functionality.

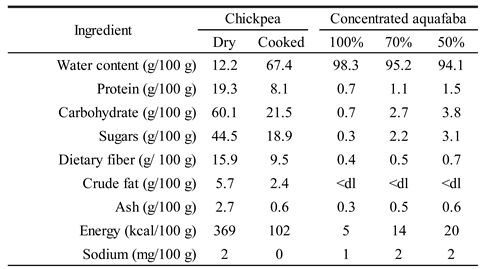

3.4. Changes in the Composition of Aquafaba Due to Reheating

Table 2 presents the major components of dry chickpeas, cooked chickpeas, and aquafaba concentrated to 100%, 70%, and 50% remaining liquid ratios. Reheating-induced changes in aquafaba composition are of particular interest as they contribute to its enhanced functionality. Reheating led to progressive concentration of components, with a notable increase in carbohydrates.

Dry chickpeas contained approximately 60.1% carbohydrates and 19.3% protein, with the primary carbohydrate being sugars (44.4%), mostly in the form of starch. These values are consistent with those reported in previous studies [

12]. Before reheating, the chickpea cooking water (100% aquafaba) contained 0.7% protein and 0.7% carbohydrates, with no detectable fat, and a total solid content of 1.7%. These results fall within the commonly reported range for aquafaba solids, which is 1–5% [

10,

14,

28]. For comparison, egg whites contain approximately 10% protein and 0.4% carbohydrates [

29]. The exceptional. foaming and emulsifying properties of aquafaba indicate that even very small amounts of eluted components can contribute significantly to its functionality. Concentrating aquafaba to 70% increased the total solid content to 4.3%, and further concentrating to 50% resulted in 5.9%. Protein content increased proportionally with concentration, whereas carbohydrates increased disproportionately. This disparity may result from partial hydrolysis of complex carbohydrates and polysaccharides during reheating, producing monosaccharides and disaccharides [

28]. The increased number of reducing sugar ends could explain the observed rise in carbohydrate measurements. Additionally, some sugars may have undergone crystallization or aggregation during heating, contributing to the higher carbohydrate fraction in the solids.

These results suggest that reheating enhances the carbohydrate content of aquafaba, which plays a significant role in its improved functionality. The accumulation of Maillard reaction products, including both low- and high-molecular-weight compounds, may also contribute to these changes. High-molecular-weight products, resembling dietary fiber, are known to enhance viscosity and stability [

26]. These compositional changes highlight the importance of sugars and their interactions with other components in the functional properties of reheated aquafaba.

3.5. Influence of Enzyme Treatment on Foaming and Emulsifying Properties of Aquafaba

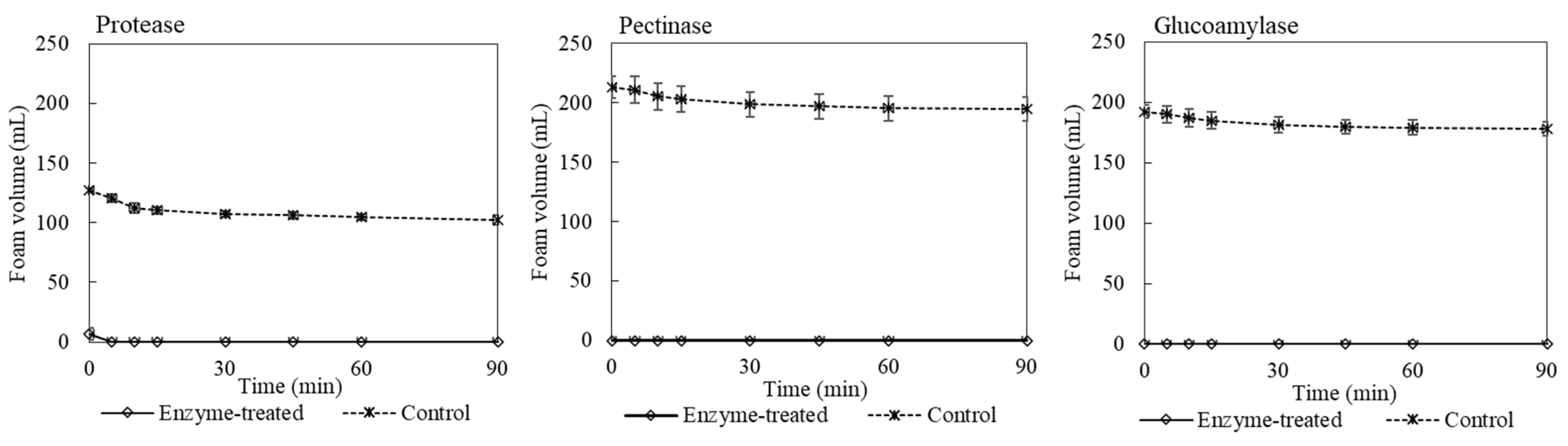

To investigate the components responsible for the foaming and emulsifying properties of reheated aquafaba, we treated it with three enzymes: protease, pectinase, and glucoamylase. These enzymes were used to hydrolyze proteins, pectin, and non-pectin carbohydrates, respectively. A control sample without enzymes was prepared under the same pH and temperature conditions as the enzyme-treated samples.

As shown in

Figure 3, in the control samples, foams were formed and remained stable for 90 min under all conditions. Notably, the foam volume was higher in the pectinase and glucoamylase controls than in the protease control, likely because the pectinase and glucoamylase controls were whipped at pH 4.5, whereas the protease control was whipped at pH 7.5. Lower pH reportedly improves foaming properties [

30]. In contrast, no foams were observed in the enzyme-treated samples, regardless of the enzyme used. These results indicate that proteins, pectin, and non-pectin carbohydrates are all essential for the foaming properties of aquafaba, and the degradation of any of these components prevents foam formation. Foam stability is generally enhanced by the adsorption of proteins onto bubble surfaces, forming stabilizing films. However, the small amount of protein in aquafaba would not be sufficient to form stable foams on its own, as the foam would likely collapse before a robust film could form. This suggests that interactions between proteins and polysaccharides play a critical role in improving foaming properties and foam stability. Proteins primarily contribute to foam formation through their surface activity, while polysaccharides stabilize the foam by enhancing viscosity and reinforcing the structure [

10]. Thus, the foaming properties and stability of aquafaba are likely dependent on the synergistic interactions among these components.

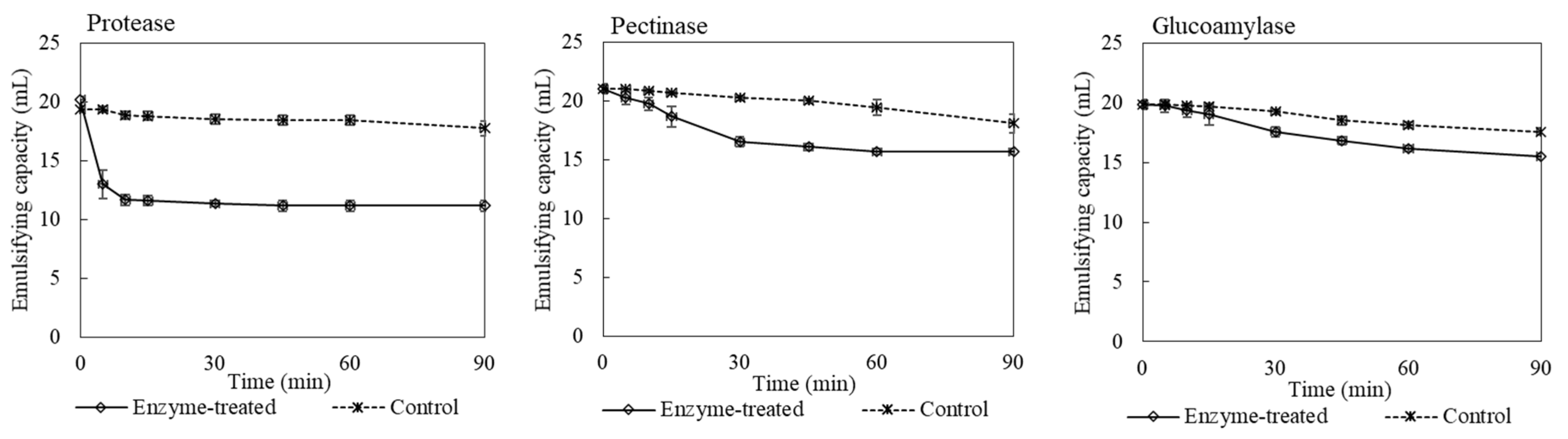

As shown in

Figure 4, emulsifying properties followed a similar trend. In the control samples, emulsions remained stable for 90 min. When treated with pectinase or glucoamylase, emulsions initially formed but gradually separated over time, with approximately 80% of the emulsified liquid remaining after 90 min. In contrast, protease treatment caused emulsions to separate rapidly, with only 58% of the emulsified liquid remaining after 10 min. These results suggest that while pectin and non-pectin carbohydrates contribute to emulsion stability, proteins play a more dominant role in the emulsification process.

Overall, the findings demonstrate that proteins, pectin, and non-pectin carbohydrates collectively contribute to the foaming and emulsifying properties of aquafaba, with proteins playing a particularly critical role in ensuring emulsion stability.

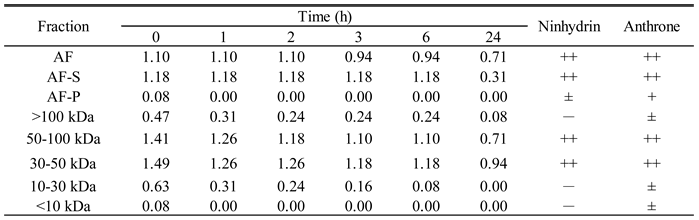

3.6. Molecular Weight-Dependent Foaming Properties of Reheated Aquafaba

The experiment described in

Section 3.5 demonstrated that proteins and carbohydrates contribute to the foaming properties of reheated aquafaba eluates. Based on these findings, this study investigated the foaming components of reheated aquafaba with a focus on molecular size. For this purpose, aquafaba with a remaining liquid ratio of 70% was used. As the solution was turbid, insoluble substances (precipitates) were first removed via centrifugation. Neither foaming nor foam stability was observed in the precipitate, suggesting that the foaming components are present in the soluble fraction. To further investigate, the soluble components were separated using a 100 kDa ultrafiltration filter. A small amount of foaming was observed in the fraction above 100 kDa, whereas the fraction below 100 kDa showed stronger foaming activity. The soluble fraction below 100 kDa was further divided into four molecular weight ranges, 50–100 kDa, 30–50 kDa, 10–30 kDa, and below 10 kD, using ultrafiltration filters of corresponding pore sizes. The results are summarized in

Table 3.

The analysis revealed that the 50–100 kDa and 30–50 kDa fractions exhibited excellent foaming properties. Foam volume was also monitored over 24 h. The 50–100 kDa and 30–50 kDa fractions maintained their foam stability for up to 6 h, with a gradual decrease thereafter, whereas fractions below 30 kDa lost their foam more rapidly. These findings suggest that components contributing to both foaming and foam stability are present in the 30–100 kDa range. In addition, a comparison of the foaming properties between the original aquafaba and the fractions with foaming activity (30–100 kDa) revealed that the 30–100 kDa fractions, particularly the 30–50 kDa fraction, exhibited improved foaming properties compared to aquafaba. This indicates that the concentration of components in the 30–100 kDa range enhances foaming activity. In other words, components below 30 kDa and above 100 kDa do not contribute to foaming properties, suggesting that the 30–100 kDa fraction represents the primary foaming components in reheated aquafaba.

Qualitative tests were conducted to determine whether the fractions contained proteins and carbohydrates. Proteins were identified using the ninhydrin reaction, and carbohydrates were identified using the anthrone–sulfuric acid method. The results revealed that the 30–50 kDa and 50–100 kDa fractions both exhibited positive colorimetric reactions, whereas no reactions were observed in the other fractions. These findings indicate that the foaming properties of reheated aquafaba are attributed to proteins and carbohydrates in the 30–100 kDa range, which also contribute to foam stability over time.

4. Conclusions

This study comprehensively analyzed the functional properties of aquafaba, focusing on the effects of reheating and enzymatic treatments on its foaming and emulsifying properties, as well as the molecular size of its functional components. The results confirmed that reheating concentrated the components eluted from cooked chickpeas, primarily proteins and sugars, which significantly contribute to enhancing aquafaba’s functional properties. Enzymatic treatment experiments further suggested that aquafaba’s foaming and emulsifying properties are achieved not only by proteins but also through interactions with pectin and other carbohydrates. The degradation of proteins by protease markedly reduced foam formation and emulsion stability, underscoring the essential role of proteins in these processes. Additionally, molecular size analysis revealed that components with foaming properties are concentrated in the 30–100 kDa range, highlighting the importance of high-molecular-weight components in the functionality of reheated aquafaba. These findings illustrate that aquafaba’s functionality arises from complex interactions among its diverse components, with reheating playing a pivotal role in enhancing these characteristics. Although this study advances our understanding of aquafaba’s functional properties, further structural analyses and investigations into the synergistic behaviors of its components are necessary.

Author Contributions

TK conducted the study design, performed experiments, statistical analysis, and wrote the manuscript. KI contributed to a portion of the experiments. TH participated in manuscript writing and conducted experiments. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mustafa, R.; He, Y.; Shim, Y.Y.; Reaney, M.J.T. Aquafaba, wastewater from chickpea canning, functions as an egg replacer in sponge cake. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 53, 2247–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhl, T.F.; Christensen, C.H.; Hammershøj. , M. Aquafaba as an egg white substitute in food foams and emulsions: protein composition and functional behavior. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 96, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Purdy, S.K.; Tse, T.J.; Tar’an, B.; Meda, V.; Reaney, M.J.T.; Mustafa, R. Standardization of aquafaba production and application in vegan mayonnaise analogs. Foods 2021, 10, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byanju, B.; Lamsal, B. Protein-rich pulse ingredients: preparation, modification technologies and impact on important techno-functional and quality characteristics, and major food applications. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 3314–3343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigwedere, C.M.; Olaoye, T.F.; Kyomugasho, C.; Jamsazzadeh Kermani, Z.; Pallares Pallares, A.; Van Loey, A.M.; Grauwet, T.; Hendrickx, M.E. Mechanistic insight into softening of Canadian wonder common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) during cooking. Food Res. Int. 2018, 106, 522–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowen, A. Development of innovative, quick-cook legume products: an investigation of the soaking, cooking and dehydration characteristics of chickpeas (Cicer arietinum L.) and soybeans (Glycine max L. Merr.). Thesis, Doctoral, 2006. Available online: http://ow.dit.ie/tourdoc/4.

- Gaur, P.M.; Tripathi, S.; Gowda, C.; Rao, G.R.; Sharma, H.C.; Pande, S.; Sharma, M. Chickpea Seed Production Manual. International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics; Andhra Pradesh, India, 2010. P.28.

- Jukanti, A.K.; Gaur, P.M.; Gowda, C.L.; Chibbar, R.N. Nutritional quality and health benefits of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.): a review. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, S11–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, P.J.; Clarke, D.C. Foam formation and stability. In Methods of Testing Protein Functionality; Hall, G.M., Ed.; Blackie Academic & Professional: London, 1996; pp. 110–149. [Google Scholar]

- Stantiall, S.E.; Dale, K.J.; Calizo, F.S.; Serventi, L. Application of pulses cooking water as functional ingredients: the foaming and gelling abilities. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClements, D.J.; Grossmann, L. The science of plant-based foods: constructing next-generation meat, fish, milk, and egg analogs. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2021, 20, 4049–4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, G.D.; Wani, A.A.; Kaur, K.; Sogi, D.S. Characterization and functional properties of proteins of some Indian chickpea (Cicer arietinum) cultivars. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2008, 88, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mine, Y. Recent advances in the understanding of egg white protein functionality. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 6, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serventi, L. Upcycling Legume Water: From Wastewater to Food Ingredients; Springer Nature: Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Soykeabkaew, N.; Thanomsilp, C.; Suwantong, O. A review: starch-based composite foams. Compos. A 2015, 78, 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, Y.Y.; Mustafa, R.; Shen, J.; Ratanapariyanuch, K.; Reaney, M.J.T. Composition and properties of aquafaba: water recovered from commercially canned chickpeas. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 132, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Kaur, S.; Isono, N.; Noda, T. Genotypic diversity in physico-chemical, pasting and gel textural properties of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.). Food Chem. 2010, 122, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of the Association of Official Analytical Chemists, 20th ed.; AOAC International: Rockville, MD, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Monro, J.; Burlingame, B. Carbohydrates and related food components: INFOODS tagnames, meanings, and uses. J. Food Compos. Anal. 1996, 9, 100–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, A.; Miyachi, N.; Matsudomi, N.; Kobayashi, K. The role of sialic acid in the functional properties of ovomucin. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1987, 51, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, E. Hydrocolloids at interfaces and the influence on the properties of dispersed systems. Food Hydrocoll. 2003, 17, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, K.R.; Johnson, I.T.; Fenwick, G.R. The chemistry and biological significance of saponins in foods and feeding stuffs. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1987, 26, 27–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsalman, F.B.; Tulbek, M.; Nickerson, M.; Ramaswamy, H.S. Evaluation and optimization of functional and antinutritional properties of aquafaba. Legume Sci. 2020, 2, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogihalli, P.; Singh, L.; Kumar, K.; Sharanagat, V.S. Physico-functional and antioxidant properties of sand-roasted chickpea (Cicer arietinum). Food Chem. 2017, 237, 1124–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sruthi, N.U.; Premjit, Y.; Pandiselvam, R.; Kothakota, A.; Ramesh, S.V. An overview of conventional and emerging techniques of roasting: effect on food bioactive signatures. Food Chem. 2021, 348, 129088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zayas, J.F. Functionality of Proteins in Food. Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 2012.

- Stasiak, J.; Stasiak, D.M.; Libera, J. The potential of aquafaba as a structure-shaping additive in plant-derived food technology. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan. MEXT. Standard Tables of Food Composition in Japan, 2020.

- Lafaga, T.; Villaro, S.; Bobo, G.; Aguilo-Aguayo, I. Optimisation of the pH and boiling conditions needed to obtain improved foaming and emulsifying properties of chickpea aquafaba using a response surface methodology. Int. J. Gastronomy Food Sci. 2019, 18, 100177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gräff, K.; Stock, S.; Mirau, L.; Bürger, S.; Braun, L.; Völp, A.; Willenbacher, N.; von Klitzing, R. Untangling effects of proteins as stabilizers for foam films. Front. Soft Matter 2014, 2, 1035377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).