Submitted:

03 December 2024

Posted:

03 December 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. The Level of Involvement in Physical Activity

2.3.2. Satisfaction with Life Scale

2.3.3. Brief Self–Control Scale

2.3.4. Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diener, E. Subjective Well-Being. Psychological Bulletin 1984, 95, 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavot, W.; Diener, E. Review of the Satisfaction With Life Scale. Psychological Assessment 1993, 5, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective Well-Being: Three Decades of Progress. Psychological Bulletin 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R.M.; Harvey, J.T.; Brown, W.J.; Payne, W.R. Does Sports Club Participation Contribute to Health-Related Quality of Life? Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010, 42, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eime, R.M.; Young, J.A.; Harvey, J.T.; Charity, M.J.; Payne, W.R. A Systematic Review of the Psychological and Social Benefits of Participation in Sport for Adults: Informing Development of a Conceptual Model of Health through Sport. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2013, 10, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, J.P.; Pincus, A.L.; Ram, N.; Conroy, D.E. Daily Physical Activity and Life Satisfaction across Adulthood. Developmental Psychology 2015, 51, 1407–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, J.P.; Doerksen, S.E.; Elavsky, S.; Hyde, A.L.; Pincus, A.L.; Ram, N.; Conroy, D.E. A Daily Analysis of Physical Activity and Satisfaction with Life in Emerging Adults. Health Psychology 2013, 32, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asztalos, M.; Wijndaele, K.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Philippaerts, R.; Matton, L.; Duvigneaud, N.; Thomis, M.; Duquet, W.; Lefevre, J.; Cardon, G. Specific Associations between Types of Physical Activity and Components of Mental Health. J Sci Med Sport 2009, 12, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downward, P.; Rasciute, S. Does Sport Make You Happy? An Analysis of the Well-being Derived from Sports Participation. International Review of Applied Economics 2011, 25, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, P.-W.; Fox, K.R.; Chen, L.-J. Leisure-Time Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviors and Subjective Well-Being in Older Adults: An Eight-Year Longitudinal Research. Soc Indic Res 2016, 127, 1349–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, M. Long-Run Labour Market and Health Effects of Individual Sports Activities. Journal of Health Economics 2009, 28, 839–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, R.; Wang, Y. The Relationship between Physical Activity and Life Satisfaction among University Students in China: The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy and Resilience. Behavioral Sciences 2023, 13, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yildirim, S.; Özgökçe, G. The Relationship Between Physical Activity and Life Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Social-Physique Anxiety and Self-Esteem. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Abe, M.; Abe, H. Lifestyle Medicine – An Evidence Based Approach to Nutrition, Sleep, Physical Activity, and Stress Management on Health and Chronic Illness. Personalized Medicine Universe 2019, 8, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, G.; Simeon, D.T.; Bain, B.C.; Wyatt, G.E.; Tucker, M.B.; LeFranc, E. Social and Health Determinants of Well Being and Life Satisfaction in Jamaica. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2004, 50, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strine, T.W.; Chapman, D.P.; Balluz, L.S.; Moriarty, D.G.; Mokdad, A.H. The Associations Between Life Satisfaction and Health-Related Quality of Life, Chronic Illness, and Health Behaviors among U.S. Community-Dwelling Adults. J Community Health 2008, 33, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, D.; Stokes, M.; Firth, L.; Hayashi, Y.; Cummins, R. Need for Belonging, Relationship Satisfaction, Loneliness, and Life Satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences 2008, 45, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumaker, J.F.; Shea, J.D.; Monfries, M.M.; Groth-Marnat, G. Loneliness and Life Satisfaction in Japan and Australia. The Journal of Psychology 1993, 127, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilhjalmsson, R.; Thorlindsson, T. The Integrative and Physiological Effects of Sport Participation: A Study of Adolescents. The Sociological Quarterly 1992, 33, 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, W.; Luhmann, M.; Fisher, R.R.; Vohs, K.D.; Baumeister, R.F. Yes, But Are They Happy? Effects of Trait Self-Control on Affective Well-Being and Life Satisfaction. Journal of Personality 2014, 82, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Baumeister, R.F.; Boone, A.L. High Self-Control Predicts Good Adjustment, Less Pathology, Better Grades, and Interpersonal Success. J Pers 2004, 72, 271–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A.; Steinberg, L. Unpacking Self-Control. Child Dev Perspect 2015, 9, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niven, K.; Totterdell, P.; Holman, D. A Classification of Controlled Interpersonal Affect Regulation Strategies. Emotion 2009, 9, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, R.A. Emotion Regulation: A Theme in Search of Definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 1994, 59, 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.J. Antecedent and Response-Focused Emotion Regulation: Divergent Consequences for Experience, Expression, and Physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1998, 74, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J.J.; John, O.P. Individual Differences in Two Emotion Regulation Processes: Implications for Affect, Relationships, and Well-Being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2003, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzarotti, S.; Biassoni, F.; Villani, D.; Prunas, A.; Velotti, P. Individual Differences in Cognitive Emotion Regulation: Implications for Subjective and Psychological Well-Being. J Happiness Stud 2016, 17, 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Zhang, D.; Wang, J.; Mistry, R.; Ran, G.; Wang, X. Relation between Emotion Regulation and Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis Review. Psychol Rep 2014, 114, 341–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertonghen, J.; Theeboom, M. The Social-Psychological Outcomes of Martial Arts Practise Among Youth: A Review. J Sports Sci Med 2010, 9, 528–537. [Google Scholar]

- Schöndube, A.; Bertrams, A.; Sudeck, G.; Fuchs, R. Self-Control Strength and Physical Exercise: An Ecological Momentary Assessment Study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 2017, 29, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakes, K.D.; Hoyt, W.T. Promoting Self-Regulation through School-Based Martial Arts Training. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 2004, 25, 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xie, J.; Huang, X. Aerobic Exercise As a Potential Way to Improve Self-Control after Ego-Depletion in Healthy Female College Students. Frontiers in Psychology 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckworth, A.; Kern, M. A Meta-Analysis of the Convergent Validity of Self-Control Measures. Journal of Research in Personality 2011, 45, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamijo, K.; Nishihira, Y.; Higashiura, T.; Kuroiwa, K. The Interactive Effect of Exercise Intensity and Task Difficulty on Human Cognitive Processing. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2007, 65, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharski, B.; Strating, M.A.; Ahluwalia Cameron, A.; Pascual-Leone, A. Complexity of Emotion Regulation Strategies in Changing Contexts: A Study of Varsity Athletes. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science 2018, 10, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavussanu, M.; Kitsantas, A. Acquisition of Sport Knowledge and Skill: The Role of Self-Regulatory Processes. In Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance; 2011.

- Kitsantas, A.; Kavussanu, M.; Corbatto, D.; Van de Pol, P. Self-Regulation in Athletes: A Social Cognitive Perspective. In; 2017.

- Kitsantas, A.; Kavussanu, M.; Corbatto, D.; Pol, P. van de Self-Regulation in Sports Learning and Performance. Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance 2018, 194–207.

- WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2020.

- Jankowski, K.S. Is the Shift in Chronotype Associated with an Alteration in Well-Being? Biological Rhythm Research 2015, 46, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilarska, A.; Baumeister, R.F. Psychometric Properties and Correlates of the Polish Version of the Self-Control Scale (SCS). Polish Psychological Bulletin 2018, 49, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobylińska, D. Kwestionariusz Regulacji Emocji [Emotion Regulation Questionnaire]. Stanford Psychophysiology Laboratory 2011.

- Śmieja, M.; Kobylińska, D. Emotional Intelligence and Emotion Regulation Strategies. Studia Psychologiczne (Psychological Studies) 2011, 49, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallucci, M. jAMM: Jamovi Advanced Mediation Models. [Jamovi Module]. The jamovi project 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jamovi. (Version 2.3.28) 2023.

- R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (Version 4.3) 2023.

- Delextrat, A.A.; Warner, S.; Graham, S.; Neupert, E. An 8-Week Exercise Intervention Based on Zumba Improves Aerobic Fitness and Psychological Well-Being in Healthy Women. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 2016, 13, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costigan, S.A.; Lubans, D.R.; Lonsdale, C.; Sanders, T.; del Pozo Cruz, B. Associations between Physical Activity Intensity and Well-Being in Adolescents. Preventive Medicine 2019, 125, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panza, G.A.; Taylor, B.A.; Thompson, P.D.; White, C.M.; Pescatello, L.S. Physical Activity Intensity and Subjective Well-Being in Healthy Adults. J Health Psychol 2019, 24, 1257–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; He, Z.; Chen, W. The Relationship between Physical Activity Intensity and Subjective Well-Being in College Students. Journal of American College Health 2022, 70, 1241–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haga, S.M.; Kraft, P.; Corby, E.-K. Emotion Regulation: Antecedents and Well-Being Outcomes of Cognitive Reappraisal and Expressive Suppression in Cross-Cultural Samples. J Happiness Stud 2009, 10, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, P.; Frick, B. The Relationship between Intensity and Duration of Physical Activity and Subjective Well-Being. European Journal of Public Health 2015, 25, 868–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, P.; Frick, B. Intensity of Physical Activity and Subjective Well-Being: An Empirical Analysis of the WHO Recommendations. Journal of Public Health 2017, 39, e19–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potoczny, W.; Herzog-Krzywoszanska, R.; Krzywoszanski, L. Self-Control and Emotion Regulation Mediate the Impact of Karate Training on Satisfaction With Life. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoud, W.B. Social Representations of Karate among Young People. Ido Movement For Culture - Journal of Martial Arts Anthropology 2015, 15, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mean | 95% CI | Median | SD | IQR | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Self–control | 36.5 | 35.2 | 37.8 | 36 | 8.90 | 10.75 | 0.314 | –0.127 |

| ERQ Reappraisal | 26.6 | 25.5 | 27.6 | 28 | 7.19 | 9.00 | –0.164 | –0.105 |

| ERQ Suppression | 14.3 | 13.5 | 15.2 | 15 | 5.80 | 9.00 | 0.032 | –0.814 |

| Satisfaction with life | 18.7 | 17.8 | 19.6 | 19 | 6.29 | 9.75 | 0.015 | –0.352 |

| Statistics | Variables | ||||

| Self–control | Reappraisal | Suppression | Satisfaction with life | ||

| Reappraisal | Pearson’s r | .250 | |||

| p–value | .001 | ||||

| 95% CI Lower | .110 | ||||

| 95% CI Upper | .380 | ||||

| Suppression | Pearson’s r | –.022 | –.140 | ||

| p–value | .765 | .057 | |||

| 95% CI Lower | –.165 | –.278 | |||

| 95% CI Upper | .122 | .004 | |||

| Satisfaction with life | Pearson’s r | .427 | .412 | –.268 | |

| p–value | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | ||

| 95% CI Lower | .301 | .285 | –.396 | ||

| 95% CI Upper | .537 | .524 | –.129 | ||

| The Level of Involvement in Physical Activity | Spearman’s rho | .341 | .148 | .028 | .248 |

| p–value | < .001 | .044 | .707 | < .001 | |

| 95% CI Lower | .204 | .003 | –.116 | .105 | |

| 95% CI Upper | .465 | .287 | .171 | .380 | |

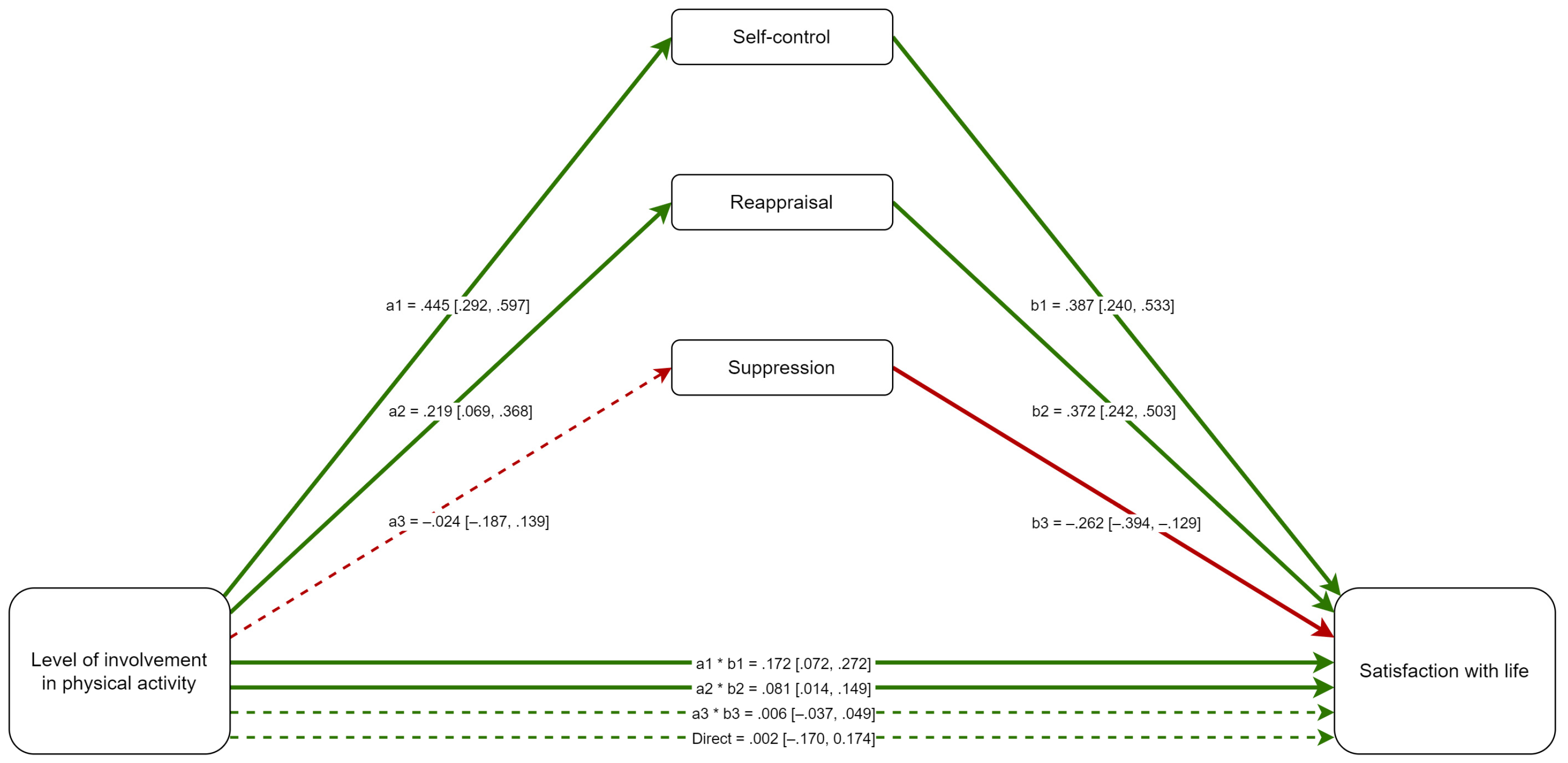

| Effect type | Effect | Estimate | SE | 95% C.I. | β | β 95% C.I. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Indirect | PA level ⇒ Self–control ⇒ SwL | 0.813 | 0.234 | 0.431 | 1.365 | 0.127 | 0.059 | 0.195 |

| PA level ⇒ Reappraisal ⇒ SwL | 0.309 | 0.151 | 0.073 | 0.687 | 0.048 | 0.004 | 0.093 | |

| PA level ⇒ Suppression ⇒ SwL | –0.003 | 0.105 | –0.230 | 0.195 | –0.001 | –0.031 | 0.030 | |

| Component | PA level ⇒ Self–control | 3.632 | 0.640 | 2.361 | 4.872 | 0.402 | 0.274 | 0.530 |

| Self–control ⇒ SwL | 0.224 | 0.051 | 0.128 | 0.329 | 0.317 | 0.189 | 0.444 | |

| PA level ⇒ Reappraisal | 1.229 | 0.473 | 0.307 | 2.193 | 0.168 | 0.042 | 0.294 | |

| Reappraisal ⇒ SwL | 0.252 | 0.059 | 0.139 | 0.367 | 0.288 | 0.157 | 0.418 | |

| PA level ⇒ Suppression | 0.014 | 0.419 | –0.780 | 0.840 | 0.002 | –0.137 | 0.142 | |

| Suppression ⇒ SwL | –0.240 | 0.072 | –0.379 | –0.101 | –0.221 | –0.351 | –0.091 | |

| Direct | PA level ⇒ SwL | 0.528 | 0.401 | –0.253 | 1.322 | 0.083 | –0.041 | 0.206 |

| Total | PA level ⇒ SwL | 1.646 | 0.418 | 0.810 | 2.440 | 0.258 | 0.133 | 0.383 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).