1. Introduction

Copper (Cu) is not an especially common element (26

th most abundant), with dissolved Cu occurring naturally in relatively low concentrations [

1,

2,

3]. Globally, copper is enriched primarily near copper mining and smelting operations and in urbanized regions [

2,

4]. Aquatic environments are susceptible to Cu largely as receivers of tailings, urban and industrial wastewater, stormwater runoff, and industrial-era atmospheric deposition [

1,

2]. Moreover, tailings generated by mining and processing plants account for the largest proportion of global waste from industrial activities. Despite lack of accurate data on the production of mine wastes, recent estimates suggest as much as 7 billion tonnes of mine tailings are produced annually world-wide with around 3.2 billion tonnes from copper operations [

5,

6].

Table 1 lists some examples of global copper mining sites that released tailings into coastal, lake, and river environments [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Mounting concern about discharge of mine tailings into coastal environments prompted the 2012 report “

International Assessment of Marine and Riverine Disposal of Mine Tailings” by Vogt [

17] for the UNEP Global Programme of Action for the Marine Environment. Among others [

7,

18], Vogt called for more extensive studies of tailings dispersal, and a world-wide ban on coastal discharges. In countries with the highest copper production, Chile and Peru, lack of adequate management of tailings compounded by mine closures without adequate remediation, remain serious problems. Research shows that contamination by mine tailings is significant for the health and environment of nearby communities [

19]. Countries with the largest environmental footprints from copper production are the United States, China, and Canada [

19,

20]. In North America, coastal mining discharges remain prohibited in the Great Lakes since 1972, under the Clean Water Act, yet so-called “legacy” sites are common, such as on the Keweenaw Peninsula. In 1990 [

21], Chile also prohibited direct discharge of Cu tailings along their Pacific coast, yet allowed release of process waters with high dissolved Cu concentrations (up to 2,000 µg/L; i.e., 2,000 ppb).

What are the long-term consequences of legacy tailings dispersal and modern-day impacts of dissolved copper on aquatic biota? As mentioned earlier, copper is not an abundant element on Earth’s surface. Major lakes and reservoirs in the U.S. have dissolved concentrations of total Cu less than 10 µg/L (parts per billion, ppb; [

22]). Concentrations in Canadian waters range from 1 to 8 µg/L Cu [

23], whereas seawater concentrations rarely exceed 0.5-3 µg/L [

24,

25]. Locally, concentrations of dissolved Cu out in central Lake Superior are as low as 0.7 µg/L [

26]. However, because of natural ore deposits, background copper in Lake Superior sediments can vary from 21-75 mg/kg (parts per million, ppm; [

27]). Serious anthropogenic copper enrichments in Lake Superior nearshore sediments and waters are found close to mining sites. Anthropogenic copper may exceed 200 µg/cm

2 in offshore sediments around the Keweenaw Peninsula (

Figure 1), plus 200-2,000 ug/L (ppb) dissolved copper in interstitial waters close to shoreline tailings piles [

8,

28,

29,

30]. Globally, near mining, milling, and smelter sites, elevated total and dissolved copper are usually associated with toxic effects on biota [

20,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]).

Copper from the Keweenaw Peninsula has a distinguished history. Indigenous people of Lake Superior (Chippewa/Ojibwe) traded copper from the Keweenaw Peninsula and Isle Royale extensively across Canada, the United States, and especially down through the Mississippi River before European settlement. Copper gathering and trading reach back at least to the Hopewill Culture, 2,000 years ago [

9,

36,

37]. Copper pit excavations date back even further, 3,580-8,500 years ago on Isle Royale and the Keweenaw Peninsula [

38,

39], attributed to an “Old Copper Culture” that utilized copper-tipped spears.

Following the 1842 “Copper Treaty” with indigenous tribes, and extending until 1968, Boston and New York companies exploited the vast abundance of native copper and silver in the Keweenaw Peninsula [

40,

41]. The region became the second-largest producer of copper in the world during the late 1880’s to 1920’s, with around 140 mines and 40 stamp mills [

42,

43,

44]. Moreover, the industrial activity left a legacy of mine tailings, an estimated 600 million metric tonnes (MMT) of poor rock and processed tailings (stamp sands) deposited inland and along several coastlines of the Keweenaw Peninsula

Figure 2; [

7,

8,

45]. The Keweenaw Peninsula and Isle Royale are unusual, because most of the copper originates as “native” copper, rather than sulfide-rich deposits. Only at the extreme ends of the Peninsula, e.g. the Bohemia Mountain Mine and Gratiot Lake deposits to the north, and the Nonesuch Shale deposits of the White Pine Mine to the south, are there copper sulfide-rich (chalcocite, Cu

2S) ores. Most world-wide mine locations contain copper sulfide ores and must additionally deal with acid mine drainage issues (

Table 1 [

46,

47]). For example, a newly opened nickel/copper “massive sulfide” mine east of the Keweenaw Peninsula, in the Yellow Dog Sand Plains near Marquette, MI, faces acid mine drainage complications. In contrast, the purity of “native copper” Keweenaw ores allowed relatively simple ore extraction and processing.

On the Keweenaw Peninsula, “stamp sands” were crushed basalt rock, tailings released as a waste byproduct from “stamp” mills. The primary ore deposits are found in a series of billion-year-old lava flows, the Portage Lake Volcanic Series (

Figure 1, dashed lines). Whereas original mining operations concentrated on removing large masses of copper, known as “barrel copper” [

48], later operations shifted to extracting copper through crushing (“stamping”) large volumes of ore at mills (

Figure 2). After crushing, particles were sorted by water-borne gravity separation, using jigs and tables [

49] to form a concentrate (ca. 40-50% Cu) shipped off to smelters. The remaining crushed fractions, often around 98-99% of the processed mass, were sluiced out of the mill into rivers or along lake shorelines, creating beach deposits and bluffs along shorelines (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4).

Early mill stamping extraction was not very efficient, as around 10-20% of the ore’s copper was lost to tailings [

42,

49]. For example, at the Mohawk Mine site, concentrations in ores (ore grade) averaged 1-2% Cu, whereas the Mohawk Mill discharged tailings averaging 0.28% copper, i.e., an estimated 6,810 metric tonnes of copper lost to tailings [

50]. Historically, an ore that contained 0.7-0.8% copper would be a mineable deposit on the Keweenaw Peninsula. For example, in the later years of Torch Lake operations, Calumet-Hecla and Quincy Mines dredged and reprocessed early Cu-rich tailings piles (>1% Cu), adding 30% to revenues [

49]. Because of such high Cu concentrations, stamp sands are a serious contaminant source to aquatic and terrestrial environments. The copper was also accompanied by an additional secondary suite of metals, e.g. aluminum, arsenic, silver, chromium, cobalt, lead, manganese, mercury, nickel, and zinc (

Table 2; [

27,

51,

52]), that occasionally exceed state standards.

The two major sand types at Grand (Big) Traverse Bay come from quite different sources (end members). The crushed Portage Lake Volcanics, the so-called “stamp sands”, are basalts (K, Fe, Mg plagioclase silicates; augite, and minor olivine), whereas eroding coastal bedrock (Jacobsville Sandstone) produces rounded quartz sands that make up the natural white beach sands [

7]. Up close under natural sunlight (

Figure 3a), individual stamp sand grains along the shoreline are largely brownish and gray, yet sprinkled with scattered green, red, white, orange, yellow, and transparent sub-angular particles, the latter coming from so-called “gangue” minerals (e.g., calcite, epidote, chlorite, prehnite, pumpellyite, microcline, and K-feldspar; [

52,

53]) found in veins associated with the copper. However, from a distance, the stamp sand beach deposits appear like dark gray beach sands (

Figure 3b).

Much of the stamp sand “coarse” fraction ended up as beach deposits or underwater sand bars, whereas the “slime clay” fraction (7-14% of total discharge [

42,

53,

54]) dispersed much further out into the bay. Slime clays spread off coastal shelves to deep-water canyons of Lake Superior (

Figure 1; “halo”). In contrast, the coarser fraction of stamp sands tended to stay in place along shorelines, but moved kilometers as beach deposits and underwater bars and fields, aided by wave and current action (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 5).

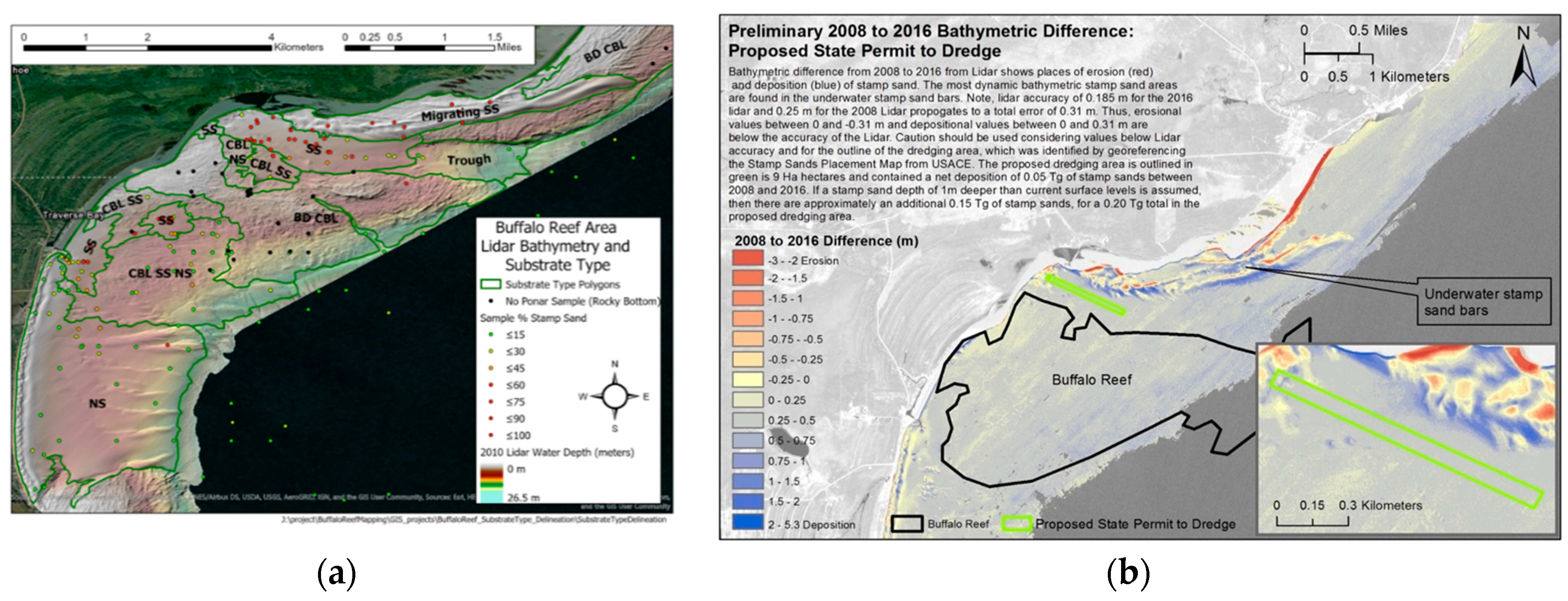

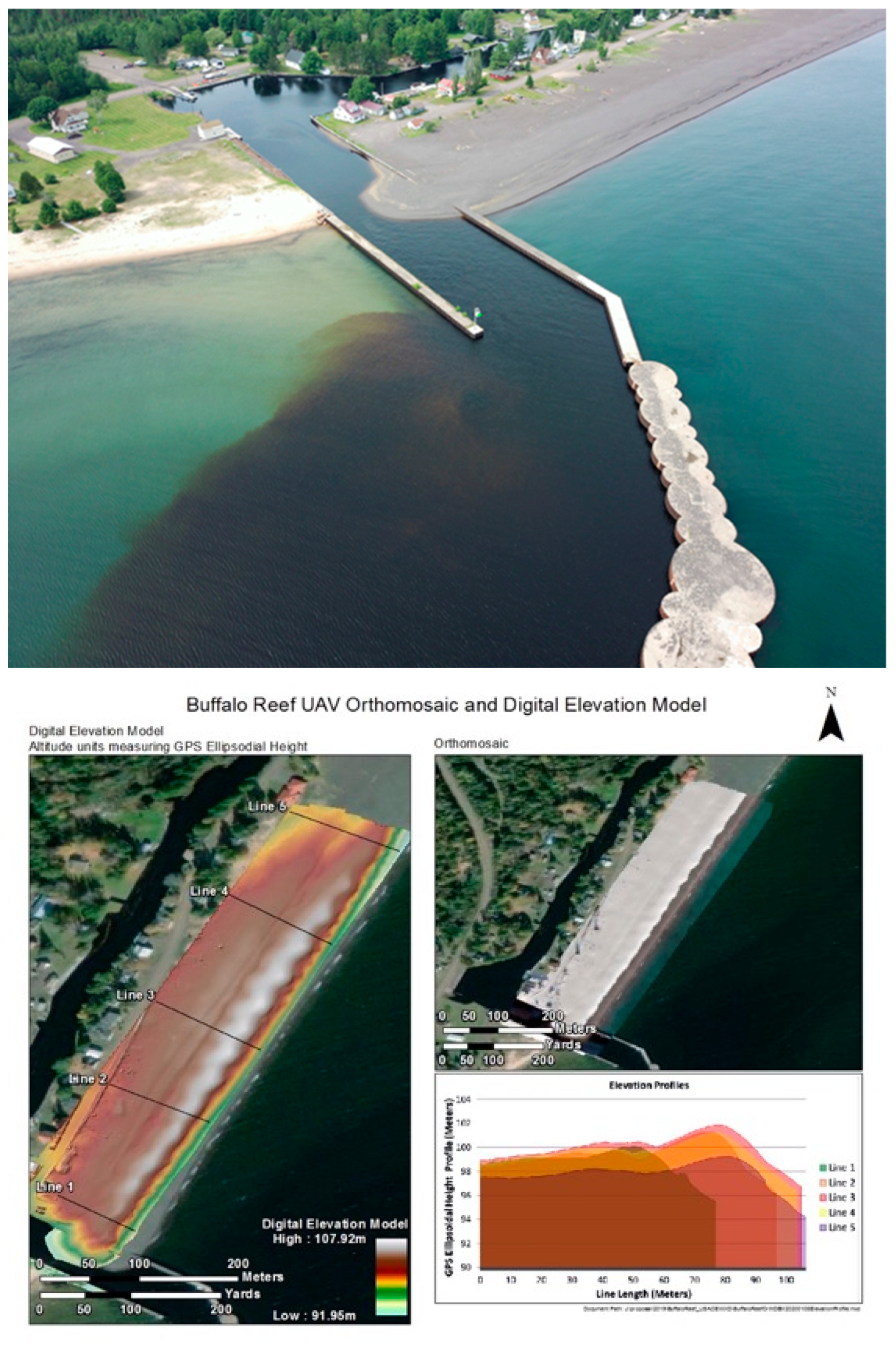

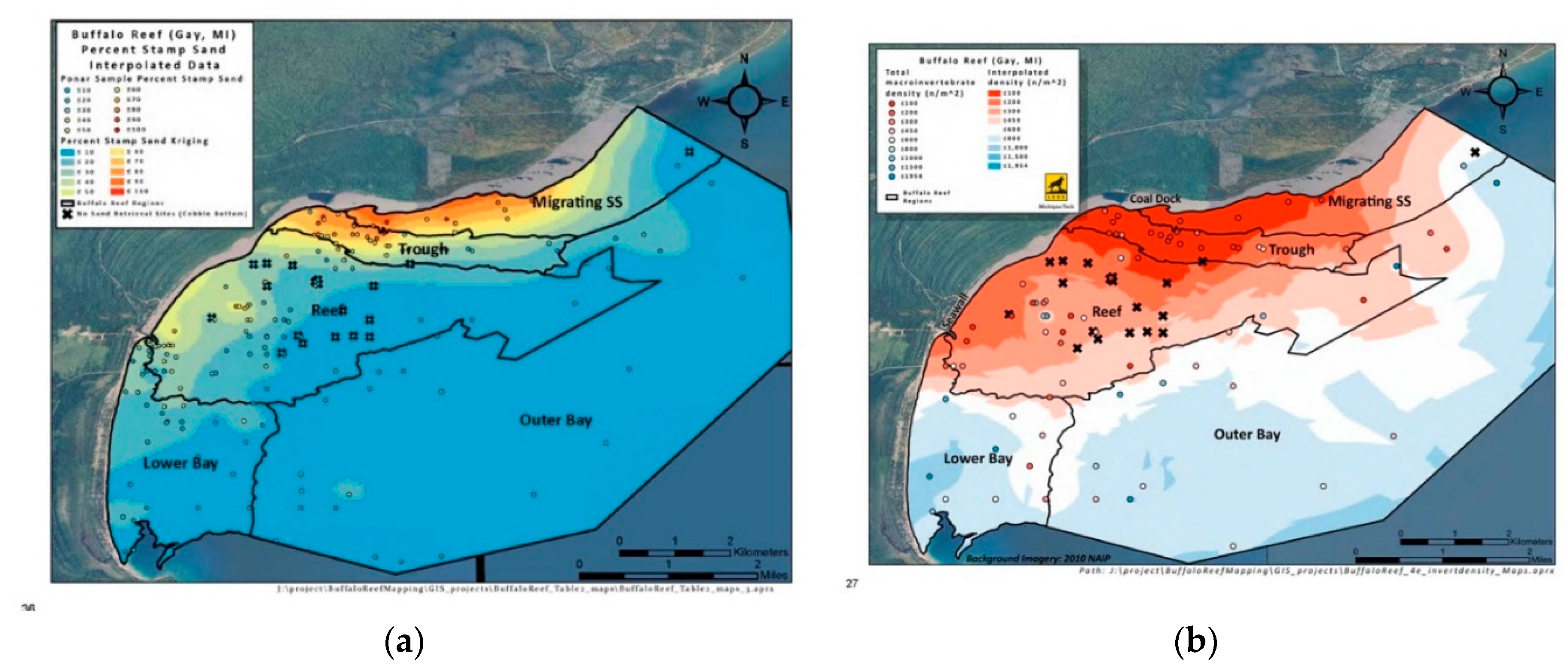

During and after deposition, the coastal tailings pile at Gay eroded as waves and currents moved stamp sands southwestward across the thin natural shoreline beach and coastal shelf towards Buffalo Reef (

Figure 5). Aerial photos and repeated LiDAR/MSS flights clarified bathymetric details of shelf and reef environments relative to stamp sand movements (

Figure 6a,b; 7,50, 54). The reef is a major spawning ground for lake trout and whitefish, accounting for 32% of commercial fishing in Keweenaw Bay, and 22% of the catch along the southern Lake Superior shoreline [

54,

56]. Fortunately, migrating stamp sands initially encountered an ancient river bed (termed the “Trough”). Over the last century, the stamp sands filled the northern portions of the river bed and are now moving into Buffalo Reef cobble fields [

7,

50,

54]. Keying off albedo (darkness, color) differences between natural sand and stamp sand beaches, we were the first to use 3-band MSS data from 2009 NAIP imagery to plot the underwater extent of stamp sands across the bay [

7,

57]. From those studies, the reef was estimated to be 25-35% covered by stamp sands in 2009-2016 [

50,

54,

57]. Within the next ten years, if nothing were done, the Army Corps of Engineering hydrodynamic models predicted increase in stamp sand cover to 60% [

54,

58].

The main point of this article is to provide a detailed example of the consequences of mine tailings discharge into a coastal environment, especially since, given recent demands for copper and nickel in computer chips, there is a renewed call for more copper mining. In particular, 1) we look at physical differences between stamp sand beaches and natural quartz grain beaches, 2) evaluate retention of copper during particle dispersal, 3) investigate leaching of copper from stamp sand beach deposits, and 3) discuss toxic impacts on aquatic organisms. Stage 1 remediation approaches (2017-2022; dredging, bluff removal, berm construction) are also reviewed.

Unfortunately, the procedure that allowed us to map stamp sand cover on Buffalo Reef did not allow detailed calculation of stamp sand percentages (7, 57). To address percentage stamp sand for remediation efforts, we devised a simple bay-specific microscopic method that quantified the percentage of stamp sand grains in mixed sediments, allowing mapping (see Methods; also [

29]). Once the copper concentration in the original source pile (MDNR value of 2860 ppm Cu) and the percentage of stamp sand in a sand mixture are known (microscope method), the copper concentration in the sand mixture can be predicted. However, the calculation assumes random dispersal of copper among dispersed stamp sand particles, i.e., no differential density or particle size sorting. Two processes could alter relative Cu concentrations in dispersing stamp sands. First, coarse sand-sized particles with higher density (greater Cu) might remain closer to the source (Gay Pile). Recall that the mills used jigs to separate denser copper-rich particles from stamp sands as a routine part of processing. Wave action along the shoreline could perform similar sorting. Secondly, because the clay fraction at the original tailings pile contains higher Cu concentrations (greater surface to volume ratio; [

27]), waves could also winnow out the fine slime-clay fractions from shoreline deposits, again reducing Cu concentrations.

We show that stamp sands migrating from the Gay tailings pile do show some site reductions of copper concentration as they reach the Army Corps Seawall at the Traverse River Harbor and off the shelf. However, stamp sand percentages remain high (80-90%) in coastal beach deposits. Shoreline percentages of stamp sand are highest between the Gay Pile and Coal Dock, but also in migrating underwater bars and in northern regions of the “Trough”. Hi-resolution drone studies show that, with progressive arrival of particles, stamp sand beaches to the south are increasing in width and height. Moreover, Hi-resolution drone studies confirm that after bluff removal at the Gay tailings pile, northern shoreline erosion has substantially increased, raising additional concerns about future “berm” site shoreline integrity and coastal stamp sand movement southwestward.

To test the above assumptions of copper concentrations associated with percentages of stamp sands, we review our recent U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Detroit Office) AEM Project (“Keweenaw Stamp Sands Geotechnical And Chemical Investigation”) survey data from 2019-2022. Over the past century, there is substantial dispersal of stamp sand particles along the beach and shelf regions of the bay (increase of 700%). However, copper concentrations were initially so high in the Gay pile, that there remain serious environmental consequences along the stretch from Gay to the Traverse River and in encroachments onto Buffalo Reef. Leaching experiments done during 2019-2022 examine beach stamp sand release of fine particulate and dissolved copper into shoreline interstitial and beach pond waters. We find that stamp sand interstitial and pond waters contain elevated copper concentrations that are highly toxic to aquatic organisms. Moreover, our investigations and in-depth complementary USACE Vicksburg (ERDC-EL) findings show that high DOC and low pH waters, characteristic of nearby river, stream, and wetland (riparian) groundwater inputs, substantially accelerate leaching of Cu from shoreline tailing beach deposits. Overall, there is now a growing consensus among participating agencies and institutions that beach and shelf stamp sands constitute a serious shoreline contaminant threat to aquatic communities and therefore should be removed from the bay. Recent additional commitments (Stage 2, 2023-) now potentially include large-structure remediation measures (construction of a jetty to capture migrating tailings; a major landfill to receive removed tailings).

2. Methods

CHARTS Coastal LiDAR (Light Detection And Ranging). LiDAR/MSS is an active remote sensing technique used over Grand (Big) Traverse Bay in the ALS (airborne laser scanning) version, where an airborne laser-ranging system acquires high-resolution elevation and bathymetric data in addition to MSS color data [

59]. “High-Resolution” here is relative, as ALS often has point density ranges of 0.9-17.4/m

2, whereas UAS helicopter drone LiDAR point density may achieve values in the tens to hundreds/m

2. In the U.S., the ALS Compact Hydrographic Airborne Rapid Total Survey (CHARTS) and the Coastal Zone Mapping and Imaging LiDAR (CZMIL) systems are separate integrated airborne sensor suites used here to survey coastal zones, in which bathymetric LiDAR data are collected with aircraft-mounted lasers. In coastal surveys, an aircraft travels over a water stretch at an altitude of 300–400 m and a speed of about 60 m s

−1, pulsing two varying laser beams in a sweeping fashion toward the Earth through an opening in the plane’s fuselage: an infrared wavelength beam (1064 nm) that is reflected off the water surface and a narrow, blue-green wavelength beam (532 nm) that penetrates the water surface and is reflected off the underwater substrate surface (

Figure 7a). The two-beam system produces a complex wave form (

Figure 7b) that when processed, quantifies the time difference between the two signals (water surface return, bottom return) to derive detailed spatial measurements of bottom bathymetry in addition to ancillary light scattering data.

During field surveys, laser energy is lost due to refraction, scattering, and absorption at the water surface and lake bottom, placing limits on depth penetration as the pulse travels through the water column. Corrections are incorporated for surface waves and water level fluctuations. In Grand (Big) Traverse Bay, we have used extensive LiDAR geophysical surveys (2008, 2010, 2011, 2013, 2016, 2019) to reveal underwater (bathymetric) and shoreline (elevation) features [

29,

50]. The resulting DEMs can be rotated from vertical to various horizontal angles to enhance bathymetric surfaces (29,57], or shading (Hillshade) added to highlight features (

Figure 5). Moreover, surfaces from separate dates can be compared to quantify erosion or deposition differences (

Figure 6b; [

29]). In particular, USACE 2010 and 2016 LiDAR overflight data were preprocessed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Joint Airborne Lidar Bathymetry Technical Center of Expertise (JALBTCX). Quality control and editing were done in GeoCue’s LP360, bulk datum transformations with NOAA’s VDatum, then products were generated using Applied Imagery Quick Terrain Modeler and ESRI ArcGIS (ArcMap and ArcGIS Pro).

The error associated with LiDAR DEMs (digital elevation/bathymetry models) is sensitive to several variables: mechanical collection (GPS coordinate system, scan altitude and speed, scan pattern, pulse-repetition rate, aircraft yaw and roll) and signal processing, weather, sea state, depth, water clarity, and wave-form clarity. Depth is important; for example, the horizontal and vertical accuracy of the CZMIL system has been described as 3.5 + 0.05 × d meters and [0.32 + (0.013 × d)

2]1/2 m (Optech Manual), respectively, where d is the water depth. Details of resolution and accuracy in oceanic projects are discussed in several recent works [

60,

61,

62,

63]. With multiple instrument measurements, vertical LiDAR accuracy can be enhanced to 0.2 m in shallow coastal waters [

64], and 0.22 (range 0.16–0.31 m) along terrestrial strips [

65]. In particular, under low-flying, high-density scanning characteristics of coastal and Great Lakes shorelines, horizontal resolution is listed by JALBTCX as 0.5–1.0 m (0.7 m) along inland beach environments, with vertical accuracy of 15 cm (Optech Manual) [

66]. Spatial resolution decreases to ca. 2 m in deeper waters (10–20 m).

Under ideal conditions in coastal waters, blue-green laser penetration allows detection of bottom structures down to approximately three times Secchi (visible light) depth. In Grand (Big) Traverse Bay studies, JALBTCX LiDAR repeatedly achieved around 20–23 m penetration [

7]. The depth was somewhat less than the 40 m recorded from oceanic environments [

67], yet adequate enough in Lake Superior to characterize shallow coastal shelf regions and to highlight critical details of tailings migration (

Figure 5and

Figure 6a,b). Of course, one of the liabilities of LiDAR plane surveys are costs (ca.

$120K per survey). Localized higher resolution, more cost-effective results now come from drone (see below), side-scan sonar, and ROV transects (7,54, 57, 68, 69, 70). The drone surveys complement initial larger-scale studies in Grand (Big) Traverse Bay. Ponar sediment grab, coring, and sonar surveys provided both ground-truth surface benthic characterization plus vertical profile studies that aided mass-balance calculations (28, 29, 45, 50, 54). Here we show how resolutions from aerial photography, ALS and localized drone surveys complement each other and allow detailed bay elevation and bathymetric calculations, aiding remediation efforts.

Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) Studies: Traverse River Harbor, Berm Complex, And Gay Pile Erosion. Several remote sensing techniques help characterize complicated small-scale geospatial features [

68,

69]. Here 3D aerial photography and high-resolution LiDAR puck transects come from a variety of drone (UAS) platforms. Both coastal erosion and deposition patterns were modeled previously with conventional aerial plane photographs and ALS LiDAR transects, plus CCIW (Canadian Center For Inland Waters) and R/V Agassiz sonar techniques [

7,

50,

54,

57,

70,

71], along with RGB drone images of the shoreline [

29]. Underwater photography (ROV), conventional and side-scan sonar (IVER3), plus triple-beam sonar surveys have also aided interpretation of underwater surface details, Buffalo Reef, and shelf depths [

7,

50,

54,

72,

73], but are not reviewed here.

Foreshore, backshore, dune, and underwater features were imaged with several low-cost Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS;

Figure 8) including MTRI’s (Michigan Tech Research Institute’s) relatively large Bergen Hexacopter and Quad-8, plus several medium and smaller quadcopters, including a Mariner 2 Splash Waterproof, which carried camera packages and LiDAR pucks (Velodyne VLP-16). Systems are all hi-resolution, providing point densities of hundreds per meter, with resolutions between millimeters to a centimeter, depending on helicopter height and respective packages [

Figure 8].

In the bay studies, the RPAS all met the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration’s definition of a “small UAS (<25 kg)”. The largest system was a hexacopter (six rotor) system (

Figure 8) manufactured by Bergen RC Helicopters of Vandalia, Michigan. The device has several important attributes, including remote control, capable of at least 15-20 min of flight time, having on-board position data from a GPS, a return to home default capability if connections are lost, ability to fly a payload of up to 5 kg, a tiltable sensor platform, plus a reasonable cost (US

$4,500-

$6,200). In addition, MTRI developed a lightweight portable radiometer (LPR) system that enabled spectroscopy at a lower cost and lighter weight than traditional handheld systems, such as the ASD FieldSpec 3 [

74]. The LPR is compact and light enough to be flown onboard a UAS that is capable of lifting at least 1 kg and is housed in a plastic box that can be attached to a typical UAS payload platform (

Figure 8). The device is capable of deploying multispectral cameras up to the size of a Nikon D810 full-frame camera, plus multispectral cameras [a Canon point-and-shoot 16 mp camera for natural color (RGB) data collection, with overlay capability of producing 3D images; a second Canon point-and-shoot camera modified to be sensitive only to the near-infrared range of ca. 830 to 1100 nm]. A Velodyne LiDAR Puck can also be fitted onto the platform. The Bergen hexacopter’s tiltable sensor platform enabled the LPR system to face forward during takeoff, then be repositioned to nadir for spectral data surveys.

The Bergen Quad-8 proved a reliable system for deploying a variety of air-born sensor systems [

75,

76,

77]. During initial testing for aquatic applications, we determined the minimal flying height (ca. 10m) at which downwash from the Bergen hexacopter does not disturb the water surface to an extent that it interferes with spectra and imagery. Hence the minimal flying altitude of ca. 10 m was used for collecting spectral data, whereas a height of ca. 25 m was used for natural color image collection. Smaller DJI Phantom 2 Vision, Phantom 3 Advanced, and Mavic Pro Quadcopter UAS were also used to provide rapid, lower resolution imagery (12 mp), yet sufficient to provide orthophoto mosaic basemaps of study areas, again at very reasonable costs (

$1600; micro down to

$500). In 2021, a DJI Mavic 2 Enterprise Advanced (M2EA) drone platform, had an integrated thermal (FLIR Vue Pro) and optical camera (Nikon D810; 20-megapixel camera). The UAS-collected images were processed through Structure From Motion (Sfm) photogrammetric software packages such as Agisoft Metashape to create Digital Elevation Models (DEMs), Hillshade Imagery, GeoTIFFs and R-JPG formats of data. ArcGIS Desktop and ArcGIS Pro aided presentations. In UAS LiDAR, imaging point density was limited to around 29.4 points/ft

2 (316.3 points/m

2), by payload capacity, yet this was still 100-fold more resolution than ALS LiDAR surveys.

Microscope Particle Grain Counting Technique. Specific Gravity can be used to determine the percentage of stamp sand in natural sand/stamp sand mixtures. However. In the lab, we found practical specific gravity assays had around a 20-30% relative error [

78]. During the procedure, concerns about relative error plus the time of effort prompted us to adopt an alternative approach, the “Microscope Particle Counting Technique”. As mentioned earlier, the two major sand types in the bay come from different sources (end members). The crushed Portage Lake Volcanics, the so-called “stamp sands”, are basalts (K, Fe, Mg plagioclase silicates; augite, and minor olivine [

79]) with angular crushed edges, whereas the coastal bedrock (Jacobsville Sandstone) produces rounded quartz sands that make up the white beach sands (

Figure 9a). The two types are silicates with similar specific gravities, and wave-sorted particle size distributions are often very similar (

Figure 9b). We emphasize that the particle counting technique is appropriate only for sites (like Grand Traverse Bay) where the two grain sources are very different and the majority of particles are sand-sized.

In Traverse Bay, under the microscope (Olympus LMS225R, 40-80X), particle grains from beaches and underwater coastal shelf Ponar samples could be separated into crushed opaque (dark) basalt versus rounded, transparent quartz grain components (

Figure 9a), allowing calculation of %SS particles in sand mixtures. Percentage stamp sand values were based on means of randomly selected subsamples, with 3-4 replicate counts, around 300 total grains in each sub-count. Standard deviations and errors were calculated for individual samples and means used to calculate confidence intervals for typical counts (

Figure 9c;

Supplemental Tables 1-2)

Technically, mixed grain counts follow a binomial distribution, where there is an inverse relationship between the coefficient of variation (CV = mean/SD) and the mean %SS (

Figure 9c). That is, from

Figure 9c, if the mean %SS is high (>50%), the Coefficient of Variation (CV = mean/SD) is relatively low (3.1%, N=12 samples), but if it is <10%, the value could be much higher (mean = 25.3%, N= 30 samples).

With the microscope technique, there are still a few issues. In natural white sand beaches, there may be scattered black, opaque sand grains that are inadvertently scored as stamp sands, if only transmitted light is used. Natural magnetite, ilmenite, garnet and manganese sands [

80,

81,

82] are occasionally present in Jacobsville Sandstone sand beaches and underwater bay sand sediments. Specific gravity and density may be used for particle separation, as magnetite (5.2 g/cm

3), ilmenite (4.5-5.0 g/cm

3), and garnet (3.4-4.3 g/cm

3) are much heavier than stamp sands (2.8-2.9 g/cm

3). Under the microscope, reflected color and size can be used to distinguish magnetite sand grains (characteristic gray, glossy metallic color; rounded, generally half the size of stamp sand particles) from stamp sand basalt particles (low to no transmission of light; dark brown, dull gray, or greenish; often with inclusions). Magnetic attraction will also confirm magnetite abundance. Magnetite granule corrections are important for beach samples, but grains are rather low in Ponar samples across Grand Traverse Bay shelf regions (averaging only 1.8% of grain counts). See

Supplemental Table 3 in [

29], which provides examples of magnetite “black sand” counts and corrections for percentage stamp sand determinations (beach and shelf samples).

Particle Sizes & Sieving. Grain sizes were measured in selected samples under the microscope, distinguishing between stamp sand and quartz grains (

Figure 9b). Otherwise, entire samples were sieved for various particle size classes. Wildco Stainless Steel Sieves (5 Mesh, 4000 µm; 10 Mesh, 2000 µm; 35 Mesh, 500 µm; 60 Mesh, 250 µm; 120 Mesh, 125 µm) were used on a Cenco-Meinzer Sieve Shaker Table (Central Scientific) or, after 2022 sampling, a Gilson 8-inch Sieve Shaker w/ Mechanical Timer (115V, 60Hz) model SS-15. Mean particle sizes from the Ponar samples were plotted across Grand Traverse Bay (see Results). See

Supplemental Tables 1-2 for latitude-longitude locations and particle size distributions in the full set.

Predicting Cu Concentrations From Stamp Sand Percentages. Extensive MDNR sampling on the Gay pile [

83] gave a mean concentration of 0.2863 % Cu, or 2,863 ppm. We adapted this value as a standard. The standard provided a first estimate for Cu concentrations in mixed sand particle samples across the bay, assuming sorting was random and wave action transported similar sizes of both particle types across different sites. Copper concentration could be determined by simply multiplying percentage stamp sand by the MDNR Pile value [

29]. For example, a 50% SS mixture would produce a predicted Cu solid phase concentration of 1415 ppm Cu, a 25% SS mixture 716 ppm, and a 10% mixture 286 ppm. Notice, the original concentration of Cu at the Gay pile is high, relative to expected Cu toxicity. Even a 10%-20% SS mixture would exceed EPA and Michigan PEL levels (probable effects levels; range from 36 to 390 ppm solid phase [

84,

85]).

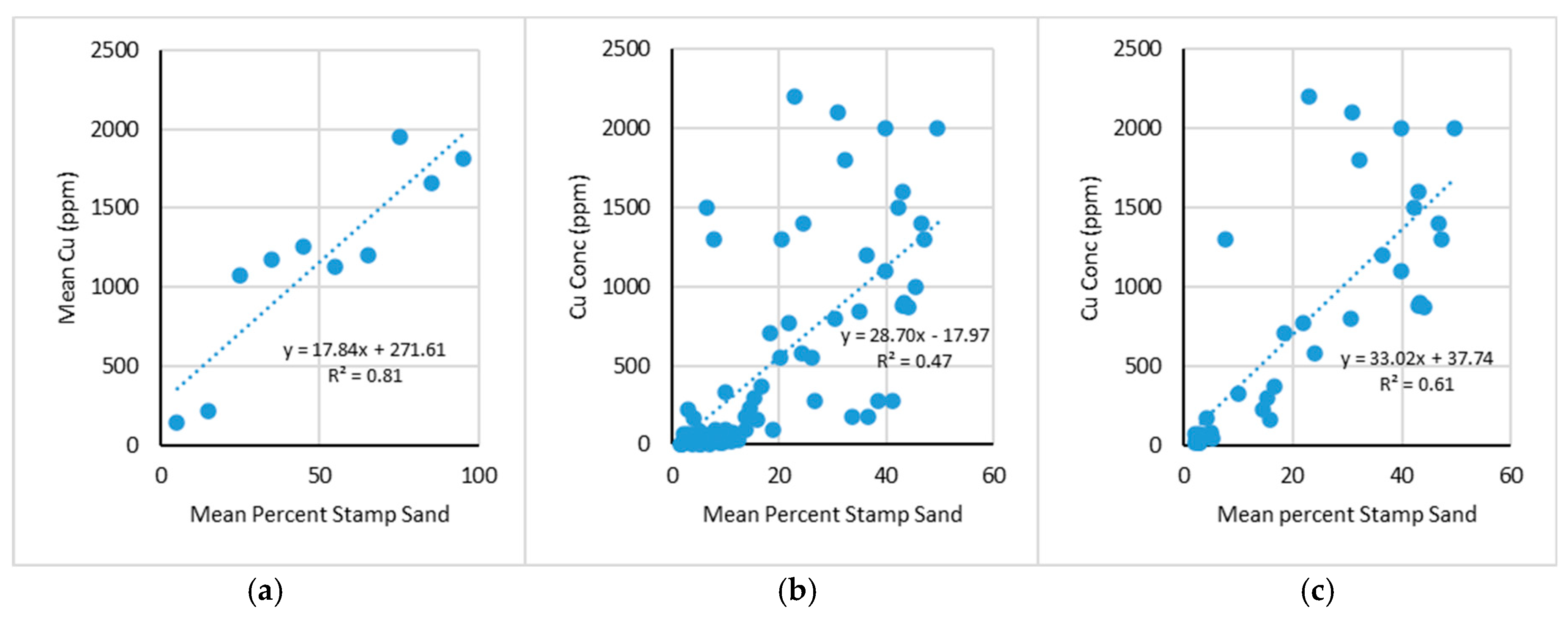

Direct Cu Concentration Comparisons (Selected Ponar Samples, AEM Project Determinations). Initially, to check our %SS predicted Cu concentrations against directly observed Cu concentrations, we determined Cu concentrations on several Ponar and beach samples, then constructed a “calibration curve” showing predicted Cu concentration against observed Cu concentration, using up to 40 samples [

29,

50]. For direct Cu determinations, beach and Ponar sediments were digested at MTU in a microwave (CEM MDS-2100) using EPA method 3051A. Solutions were shipped to White Water Associates Laboratory for final analysis. Copper was measured using a Perkin-Elmer model 3100 spectrophotometer. Digestion efficiencies were verified using NIST standard reference material Buffalo River Sediments (SRM 2704), and instrument calibration was checked using the Plasma-Pure standard from Leeman Labs, Inc. Digestion efficiencies averaged 104%, and the calibration standard was, on average, measured as 101% of the certified value. There was initially a good correlation between %SS predicted Cu concentration and directly measured Cu concentrations for two tests, R

2 = 0.911 [

50]; and R

2 = 0.868 [

29]. However, regression slopes and intercepts suggested slightly lower than predicted values.

As a major independent check on the microscope %SS method and its correspondence to Cu concentrations across bay sediments, we collaborated in an extensive Army Corps AEM Project (2019-2022). The Project directly compared our %SS predictions with direct Cu analysis of beach stamp sand and underwater shelf sediments across Grand (Big) Traverse Bay, using a combination of Ponar sampling and sediment coring techniques. Percentage stamp sands (% SS) were determined in our MTU laboratory using the microscopic particle counting technique, whereas the corresponding Cu analyses were run at Trace Analytical Laboratories, Muskegon, MI.

The full AEM set included Ponar and core samples from three different locations: 1) deep water (DW; 7 samples; not really appropriate for the microscope technique; but on sand particles retrieved after sieving), 2) over water (OW; 52 coastal shelf samples, sand mixtures), and 3) on land (OL, beach sands; 104 sand samples). Again, normally the technique would not be used on deep-water samples because they are dominated by silt and clay-sized particles (62.5µm - 0.98µm; [

86]), so some grain sieving was necessary to retrieve sand-size particles. The “Over water” samples were from the shelf region, generally dominated by medium to fine sand-sized particles (0.5mm - 125µm;

Supplemental Table 3). The “On Land” sites were all beach deposits with medium sands to fine gravel (0.25mm-8mm). The combined 164 samples were dominated by beach samples (see

Supplemental Table 1), largely because beach cores were sliced into sections, moving from upper stamp sands into lower quartz sand (original beach) deposits.

As mentioned earlier, copper concentrations were run independently at Trace Analytical Laboratories, Muskegon, MI. Results from the AEM analyses are plotted in the Results section. An issue with the tabulated data from AEM Cu determinations was great variability in Cu concentrations beyond 50% Stamp Sand mixtures, especially in the beach core studies. Some of the great scatter was due to low lab standards (AEM Report). To better handle the variation, we considered the data sets as independent runs and dealt with the scatter by a variety of conventional statistical methods. Due to heteroskedasticity, fitting a regression line to the entire original set was not appropriate, since the variance around regression increased with %SS and Cu Concentration plots (especially >50% SS), leading to inappropriate regression application. These heteroskedastic effects could be reduced by a variety of statistical methods: 1) log transforming the data, 2) plotting grand mean values of Cu concentrations at intervals of % SS, or 3) looking at only a portion of the set (e.g. the lower end, 0-50% SS) where there was less heteroskedasticity. We utilized options 2 and 3. In addition, a table was constructed which listed the previous “calibration curve” regression [

29], along with the three various AEM regression equation intercepts. In that table, the 100% SS regression intercept values could then be cross-compared against the mean Gay Pile standard value (i.e. the MDNR 0.2863 % Cu value).

Copper Leaching: Laboratory & Field. Whereas copper retention in migrating stamp sand particles is important, copper loss into waters is critical for assaying toxicity under field situations. Leaching of copper was studied simultaneous at MTU and in much more detail at the Army Corps of Engineers laboratory in Vicksburg, MS (ERDC-EL). MTU water agitation included: 1) Lake Superior waters with low TOC/DOC, and 2) tannin-stained waters from the river and wetland swales with relatively high TOC/DOC and low pH (Traverse River, Coal Dock stream). Several gallons of water (5-10) were collected at five different field sites and placed in 140mL polyethylene bottles. Flasks were prepared that contained 5g of 100% stamp sand (Gay Tailings Pile) and 25mL of water (i.e. 1:5 solid to liquid ratio). The vials were shaken and stirred periodically on a shaker table for an interval of one week, a single, prolonged leaching exposure. At the end, samples were run for both total suspended copper and separately for filtered (0.45 µm; dissolved) copper. Nitric acid (1%) was added to each dissolved sample and the initial samples cold-stored (4°C) until sent for metals analysis at the MTU School of Forestry Laboratory for Environmental Analysis of Forests (i.e., LEAF Lab). A Perkin Elmer Optima 7000DV ICP-OES was used separately for determining total and dissolved metal concentrations (for Cu, Al, Fe). Total organic carbon (TOC) was determined using a Shimadzu TOC-LCPH analyzer. A ~25mL subsample of water had its pH measured using Fisher Scientific Accumet AE150.

In 2019, to check copper leaching at field locations, we collected water samples from various beach stamp sand ponds just southwest of the Gay pile (Pond Field,

Figure 6a,b). The water samples had a total metals analysis done on them for Cu and Al, again at the LEAF Lab. Sampling several ponds (15 samples) provided a range and mean of total Cu concentrations from interstitial waters typically confronted by aquatic organisms on stamp sand beaches. Note that the 2019 pond water sampling preceded construction of the “Berm Complex” and subsequent neighborhood mixing of “Berm” and pond waters.

The Army Corps, as part of the Buffalo Reef Project, also sampled stamp sands, pond and interstitial waters from the Gay pile and later “Berm Complex”. Samples were sent to various ERDC-EL facilities in Vicksburg, MS, for chemical characterization and more extensive leaching experiments with multiple and variable water rinses. The results of those detailed beneficial use application and physical and chemical investigations are found in an internal Report (Schroeder, P.; Ruiz, C.

Stamp Sands Physical and Chemical Screening Evaluations for Beneficial Use Applications; Environmental Laboratory, U.S. Army Engineer Research and Development Center: Vicksburg, MS, USA, 2021; [

86]). In the leaching section, we discuss both MTU and ERDC results. Vicksburg’s suite of chemical tests for stamp sands and contaminant pathways included a much broader range of variables: pH, TOC, copper, arsenic, aluminum, antimony, beryllium, cadmium, chromium, cobalt, lead, lithium, manganese, mercury, nickel, selenium, strontium, thallium, and zinc.

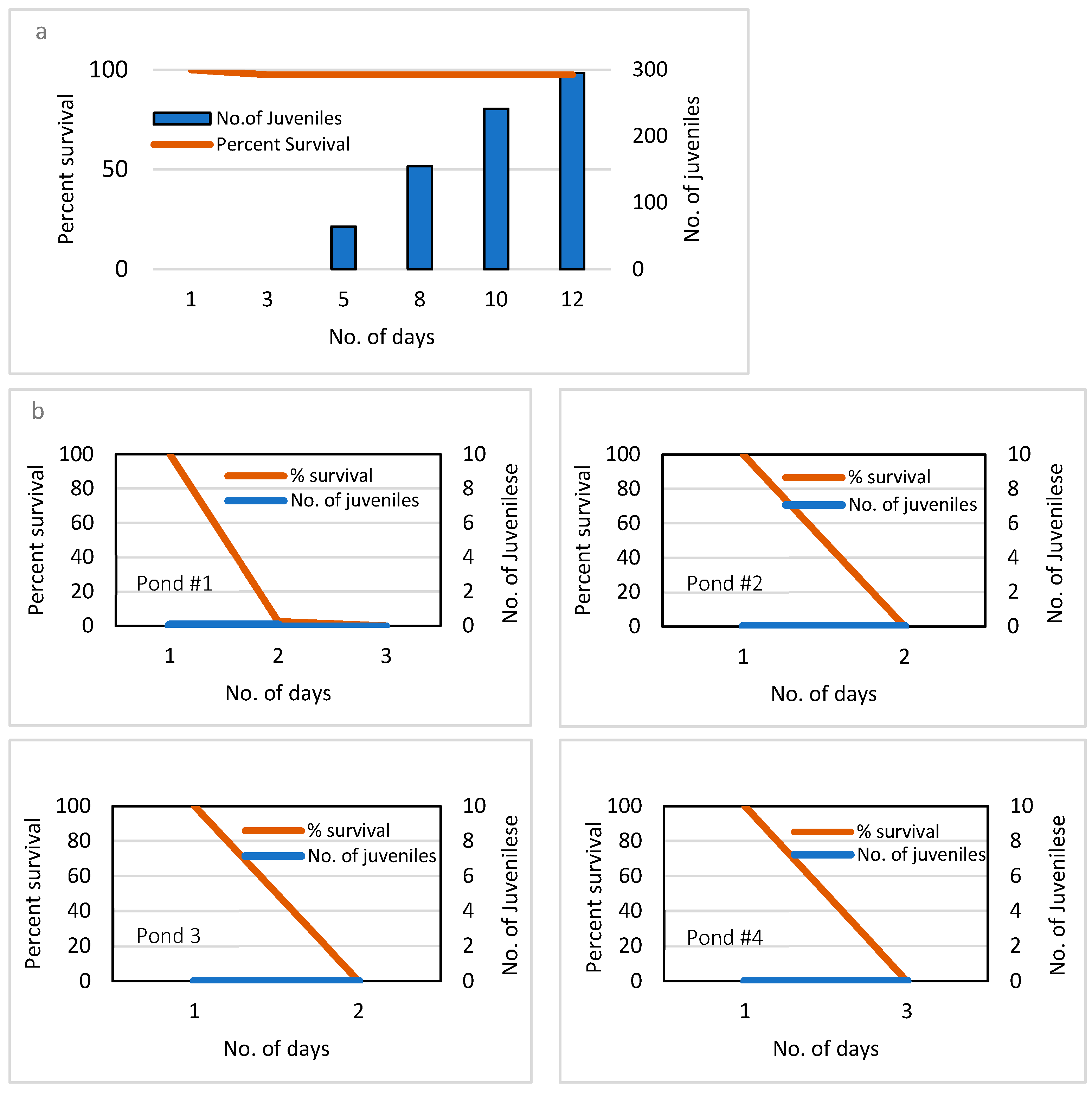

Field (Stamp Sand Pond) And Laboratory Toxicity Experiments. In 2019

, to check for toxicity of waters on invertebrate organisms [

87],

Daphnia survivorship and fecundity experiments were run in the stamp sand ponds before the Berm Complex construction. A corresponding “Control” was placed at the Great Lakes Research Center dock in Portage Lake water. The Gay and Control field tests used the same suspended vial arrangement (

Figure 10). Water exchange rates in the field mesh-covered vials were measured earlier in corresponding 1990’s pond placements, using methylene blue dye [

87,

88]. The

Daphnia used in the stamp sand pond experiments were native species (

Daphnia pulex) collected from nearby forest ponds [

88]. At each stamp sand pond, a rack with forty 40mL vials were initially filled with filtered Portage Lake water and a single adult

Daphnia, then covered with 100µm mesh (

Figure 10), and set on a shallow pond bottom. Every two to three days, the

Daphnia vials were retrieved, survivorship and fecundity scored. The experiments were planned to last for fourteen days or until survivorship reached zero. Since nearly identical procedures were used in the 1990’s and 2019 tests, our recent results could be cross-compared with earlier in situ survivorship and fecundity, plus lab LD

50 results, to see if pond conditions had changed over 24 years.

In the laboratory,

D. pulex were raised in filtered (SuporⓇ-450; 0.45µm) water from Portage Lake. Laboratory feeding was Carolina Supply

Daphnia food. Cultivating procedures followed USEPA 2002 guidelines [

86,

87]. Twenty-four earlier (1990’s), laboratory LD

50 tests were also conducted on native

D. pulex [

88,

89]. A live

Daphnia magna stock was also ordered from Carolina™. The

Daphnia magna were placed in 40 mL vials (the same set-up used in the pond experiments) filled with 40mL of Bete Grise Lake Superior water and stock Cu solutions in a dilution sequence. The stock solutions consisted of 1L of Bete Grise water with 1 mg of dissolved Cu, creating a potential stock solution of 1,000 ppb Cu, which was subsequently diluted to test concentrations. The sequence used ten replicant vials at Cu concentrations of 1,000 ppb, 500 ppb, 250 ppb, 100 ppb, 50 ppb, 25 ppb, 10 ppb, 5ppb, and 0 ppb. Copper concentrations were made by dissolving cupric sulfate (CuSO

4 5H

2O) salt in filtered Bete Grise water. As a check, a subsample of the stock solution was sent to the LEAF Lab to check expected Cu concentrations. As a consequence, after direct LEAF Lab measurements, concentrations were slightly adjusted. The survival of adults was recorded at 24hrs, 48hrs, and 72hrs for each vial at each Cu concentration value. A probit test was done for the 24hr data to calculate the estimated LD

50 value. The LD

50 value was then compared with published literature values for

D. magna and other

Daphnia species [

90,

91], including our earlier 1990’s estimates for neighborhood

D. pulex.

4. Discussion

Global Tailings Management. Several copper mining operations (examples in

Table 1) continue to discharge copper-rich tailings into river and coastal environments. Although banned in the Great Lakes of Canada and the USA since the Clean Water Act of 1972, there remain many other “legacy” (iron, gold, and copper) sites around the Great Lakes Basin where tailings are confined behind river coffer dams, or placed in tailings ponds that eventually will collapse and contaminate watersheds. Elsewhere, for example in Chile, because of increasing copper demand, the current 800 MMT per year of tailings production is projected to nearly double by 2035 [

97]. Since 2014, there were four major global tailings dam failures that killed hundreds of local residents and severely contaminated environments around the globe: Mount Polley, Canada (2014); Fundao Samarco, Brazil (2015); Corrego Do Feijao Brumandinho, Brazil (2019); and Jagersfontain, South Africa (2022). As a consequence, an international effort [International Council On Mining and Metals (ICMM), UN Environmental Program, and the Principles For Responsible Investments (PRI)] drafted a “Global Tailings Management Standard For the Mining Industry”. Launched in August 2020, the Standard emphasizes tailings management and urges adoption by all mining companies world-wide [

98]. Unfortunately, only two mining companies to date have adopted the protocols.

As illustrated in the Buffalo Reef Project, technical advancements in remote sensing have greatly advanced coastal environmental assessments, allowing us to “see” nearshore features in detail both at the edge and beneath waters. Geospatial surveys (aerial photography, LiDAR, multispectral studies; side-scan and triple-beam sonar; ROV, drone photography and “puck” instrument package surveying, sediment coring) now seem mandatory for characterizing coastline contamination. The Buffalo Reef Project quantified progressive encroachment of tailings onto Buffalo Reef. Aerial photography and LiDAR studies by other authors along natural beaches elsewhere have also revealed repetitive cuspate structures associated with exiting surf-zone currents [

99,

100,

101]. Wave hydrodynamics and local [

99,

100,

101] beach currents and micro-structures modify both nearshore sediment transport and wave breaking. The use of conventional (ALS) and high-resolution UAS LiDAR imaging has confirmed tailings beach alteration related to nearshore microstructure [

7,

50]. In Grand (Big) Traverse Bay, conventional and UAS elevational measurements aided Vicksburg’s hydrodynamic modeling efforts [

58], as larger waves provided a mechanism that made stamp sands migrate faster along the shoreline and move further inland than originally anticipated.

As discussed earlier, after years of investigations and planning, the Buffalo Reef Project moved into initial remediation steps (Phase 1) during 2017, with 5-Agency (EPA GNPO, MDNR, Army Corps of Engineers, GLIFWC tribal) initial funding of around

$7.5M. Challenges past Stage 1 dredging, geospatial surveys, and planning for the Project included: 1) determining short-term and long-term toxic environmental effects, 2) considering measures to protect Buffalo Reef against migrating tailings, and 3) constructing a place for stamp sand disposal. In addition, there was an additional priority towards finding regional benign applications for stamp sands (Keweenaw and Houghton Counties: winter road ice and snow application; road-bed construction, fill, aggregates for concrete). We previously estimated road application had removed an estimated 1 MMT from the Gay Pile [

7].

Toxicity Concerns Relative To Tailing’s Cu Leaching. “Stamp sand” toxicity has now been investigated by numerous agencies, with results reaching a clear consensus, which we will review here. Recall that the concentration of Cu in Gay Pile stamp sands was 0.28% of mass. At an extensive Gay tailings pile site sampling in 2003, several metals were found to exceed the State of Michigan Groundwater Surface Water Interface Criteria (GSWIC) levels (Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, [

102,

103,

104]). The sampling included 274 soil samples. Aluminum exceeded levels in 271 samples, chromium in 265, cobalt in 271, copper in all samples, manganese in 159, nickel in 168, silver in 216, and zinc in 242. In ten groundwater samples, the number of metals exceeding GSWIC risk criteria for dissolved metals included: chromium 5, copper in all 10, manganese 5, nickel 8, silver 8, and zinc 8. In 2003, MDEQ also collected stamp sands from a southern redeposited stamp sand beach site, north of the Traverse River Seawall (N= 24 samples). Here copper averaged lower, 710-5300 μg g

-1 (mean = 1443 μg g

-1, or ppm) than at the Gay site. But in the 25 samples, various other metals again exceeded GSWIC levels: aluminum in 20 samples, chromium in 19, cobalt in 24, copper in all 24, manganese in 7, nickel in 8, silver in 9, and zinc in 10 [

102]. However, in subsequent lab tests, Weston Solutions [

83] showed that only copper (total concentrations) exceeded “surface water quality” criteria in both porewater (interstitial) and pond waters. Weston initially suggested copper and perhaps aluminum water releases were the most important relative to toxicity.

Recent Army Corps ERDC studies also looked at detailed elemental concentrations within stamp sand beach deposits, at three separate sites mentioned earlier: Gay Pile, Coal Dock, and against the Traverse Seawall [

95]. Fewer site measurements were made than in the earlier MDEQ series, consequently there was greater variability. Because basalt is an aluminum, calcium, magnesium silicate, these elements were especially abundant. Whole sample mean copper concentrations at the three sites were 3,460 ppm, 2,400 ppm, and 2,810 ppm, similar to our AEM results. Elements exhibited the following ranges: aluminum (12,700-14,700 ppm); arsenic (5.52-6.39); cadmium (0.405-0.544); calcium (18,100-32,200); chromium (15.8-24.0); cobalt (26.4-31.3); lead (2.39-3.68); lithium (5.59-6.23); magnesium (16,100-17,800); manganese (389-459); nickel (24.4-26.0); selenium (1.90-2.76); strontium (11.6-21.6); and zinc (57.9-68.7).

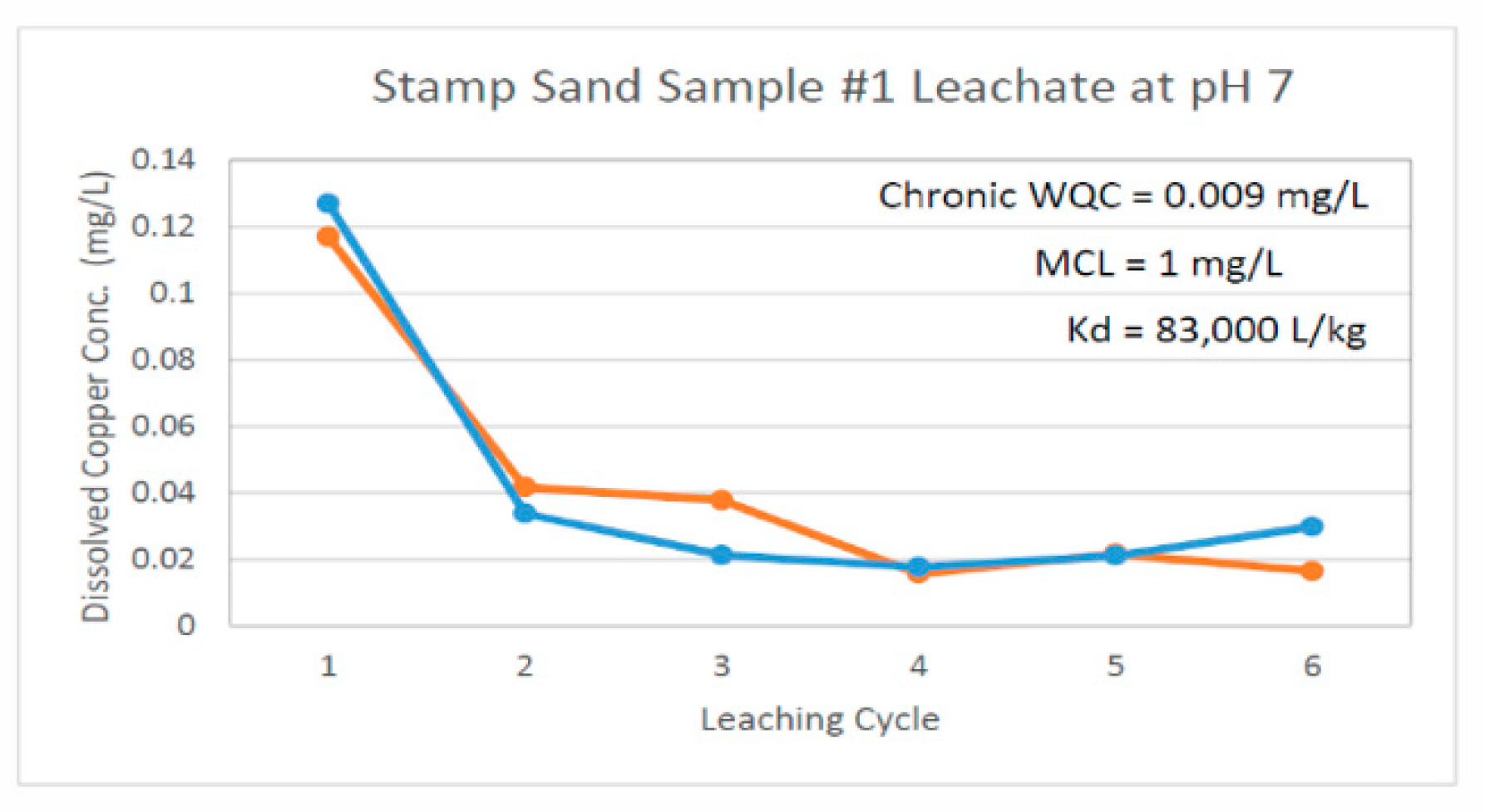

In the lab, ERDC conducted short and long-term runoff tests for stamp sand beach deposits. The long-term followed USACE Upland Testing Manual (2003) techniques, to check on toxicity. In the ERDC studies, runoff water quality was evaluated for three size fractions and solids concentrations of 250, 500, 1500, 5,000 15,000, and 50,000 mg/L (ppm) with challenge waters of pH 4.2, pH 7, and TOC. An important result was that in the presence of environmentally reasonable concentrations of TOC/DOC (20 mg/L), leachability of Cu in stamp sand was increased by about a factor of 25 and the partitioning coefficient was also increased by about a factor of 18. Consequently, they found that leaching of copper in the presence of TOC/DOC is likely to persist about 20 times longer than in the absence of TOC/DOC [

95]. This result supports findings of Jeong et al., 1999[

105], that when tannin-rich forest groundwaters move through stamp sand, they accelerate the leaching of dissolved Cu into interstitial waters, stamp sand beach ponds, and along the shoreline margin.

ERDC also found that runoff water exceeded both the acute and chronic water quality criteria for copper, and occasionally for aluminum, in pH 4.2 challenge waters (short and long-term tests). Median dissolved Cu concentrations released in long-term tests were 146-430 ppb. Multiple leaching (rinsing) tests showed that dissolved copper concentrations generally decreased for stamp sand samples with additional rinses (

Figure 18), yet challenge waters remained greater than the water quality criteria (WQC) for chronic toxicity (

Table 7). Of the other elements, despite lead and zinc decreasing throughout leaching cycles, both elements occasionally exceeded WQC levels for chronic toxicity.

ERDC aditionally checked the transport of Cu during dredging, followed by deposition into “retaining ponds surrounded by stamp sand berms” (

Figure 14). Concentrations in the dredging slurry released into the receiving “Berm Complex” were sampled, as well as seepage through berm walls into outlying ponds. In 2022, ERDC found a seepage pond adjacent to the outer rim of the berm to have a total mean Cu concentration of 1,710 ppb, whereas berm disposal waters were even higher (mean total copper = 2,850 ppb). These elevated levels justified concern about long distance slurry transport in low pH and high TOC/DOC water raising copper levels. Copper concentrations from separate sampling of elutriates, Berm, and pond waters ranged between 234-2,120 ppb total Cu, whereas dissolved Cu varied between 24-117 ppb [

95].

In summary, both our and ERDC leaching experiments revealed that almost all of the copper mass is retained within dispersed stamp sand particles. This is why migrating particles across the bay remain toxic. As particles moved away from the eroding Gay tailings pile, AEM results showed slightly lower concentrations of copper, again confirming some particle sorting during dispersal. Yet the amounts of Cu released, especially near low pH and high DOC/TOC waters, were considerably above acute levels.

Field & Laboratory Acute Toxicity Tests. Direct toxicity tests were run on several small stamp sand beach ponds south of Gay, in addition now to the “Berm Complex” that received dredged material from both the Traverse River “over-topping” and from the “Trough”. Our preliminary leaching experiments with stamp sands suggested an initial release of around 300-600 ppb total Cu into waters when stamp sands were agitated with water for a week (range 330-590 ppb, mean 448 ppb). Direct measures of total Cu in 13 ponds (range 50-2,580 ppb; mean 575 ppb) were comparable, if not slightly higher. When

Daphnia pulex were submersed in stamp sand pond waters at 4 sites, most died within 48 hours and produced no young. Our acute toxicity tests (LD

50%) showed that values as low as 8.6 ppb dissolved copper would kill

Daphnia. The rapid death of

Daphnia in waters that range from 50 to over 2,000 ppb total Cu is thus no surprise.

Daphnia have never been found in stamp sand ponds, despite wide-spread species abundance in nearby forest ponds and pools. Moreover, our acute toxicity values for

Daphnia correspond closely with literature values for different

Daphnia species and our previous 1990’s determinations (

Table 7).

Around the late 1990s, we mentioned earlier that our laboratory performed LD

50% tests on local

Daphnia pulex [

88,

89]. We ran comparable immersion experiments in the Gay stamp sand ponds at that time and measured dissolved Cu in pond waters. In the lab, three separate experiments with native

D. pulex gave results of 9.4+/-0.1 ppb, 3.6+/-0.5 ppb, and 10.4+/-2.0 dissolved Cu for LD

50% levels, comparable to recent results. Moreover, total Cu measured in several of the then 26 stamp sand ponds ranged from 45-1,712 ppb, with a mean of around 440 ppb, again comparable to recent results.

Daphnia pulex (from neighborhood forest pond waters) placed in submersed vials at that time also died rapidly relative to control sites. The main point is that interstitial and pond waters have remained highly toxic to aquatic life for over 25 years of testing at the pond stamp sand beach site. ERDC measurements of Cu toxicity levels are higher now in the Berm Pond Field, related to inputs of dredged material, low pH, and elevated TOC/DOC in slurry water.

Toxicity Results With Other Invertebrates & Fish. A variety of agency and institutional tests of stamp sand-contaminated sediments from the Keweenaw, as well as specific tests with Grand (Big) Traverse Bay sediments, have demonstrated toxic effects on organisms other than

Daphnia. Here the EPA test results include not only crustaceans, but a variety of benthic invertebrates. Freshly worked stamp sands in lake sediments were toxic to

Daphnia and mayflies (

Hexagenia) because they released Cu across the pore-water gradient [

106]. Additional laboratory toxicity experiments with stamp sand-sediment mixtures at EPA-Duluth [

107,

108,

109] showed that solid phase sediments and aqueous fractions (interstitial water) were lethal to several taxa of freshwater macroinvertebrates: chironomids (

Chironomus tentans), oligochaetes (

Lumbriculus variegatus), amphipods (

Hyalella azteca) plus cladocerans (

Ceriodaphnia dubia). In the latter studies, the observed toxicity was almost exclusively due to copper, not other metals in the secondary suite (principally zinc and lead). Weston Solutions [

83] toxicity studies in Grand (Big) Traverse Bay also tested

Ceriodaphnia dubia,

Hyalella azteca, and

Chironomus. They utilized dilutes with five sediment samples from the Gay pile and the southward stamp sand shoreline. All sediment samples showed acute and chronic effects (growth, reproduction) on benthic organisms.

In even more recent MDEQ investigations [

104], six sediment locations were sampled along the Gay to Traverse River shoreline transect. Solid phase copper concentrations varied between 1500-8500 μg g

-1 (mean 2,967 ppm), whereas the secondary suite had: Ag 1.2–1.7 μg g

-1 (mean 1.5), As 1.7–3.1 μg g

-1 (mean 2.2), Ba 6.6–8.6 μg g

-1 (mean 7.7), Cr 31–39 μg g

-1 (mean 35), Pb 2.1–2.9 μg g

-1 (mean 2.6) and Zn 62–79 μg g

-1 (mean 72). Bulk sediment toxicity testing showed that all six sediment samples from the shoreline were acutely toxic to both

Chironomus dilutes and

Hyalella azteca.

In the recent ERDC Vicksburg tests, the Army Corps [

95] also ran additional suspended and dissolved phase toxicity tests on supernatants from each of the elutriate tests concerning dredging material released into the berm complex. Both acute (48- and 96-hr) and chronic (7-day) toxicity tests were run using the daphnid

Ceriodaphnia dubia and the fathead minnow (

Pimephales promelas). Additional tests were run on filtered elutriates of the original Gay pile stamp sand and unfiltered pond water from the berm dredging ponds. The results showed that untreated and undiluted effluent was likely to be acutely toxic, and would require great dilution to eliminate toxicity. Recall that “Disposal” (Berm) pond water (often with suspended clay) had a total suspended Cu concentration of 2,850 mg/L (ppb) compared to 1,710 mg/L (ppb) in standing elutriation (dredged) water. Effluent water LC

50 acute toxicity values (standards) ranged between 1.5-14.9 ppb for

Ceriodaphnia and 28-55 ppb for

Pimephales, whereas chronic toxicity values ranged between 1.5-12.5 ppb for

Ceriodaphnia and 28-55 for

Pimephales. The ERDC data again suggest that the berm complex now contains higher Cu concentrations than we sampled in the Pond Field 20-25 years ago. ERDC site cross-comparisons did suggest that stamp sand from the original Gay pile had greater toxicity than stamp sands that have migrated down the shoreline, in keeping with reduced Cu concentrations at some sampling sites; yet because of the still relatively high Cu concentrations leached, invertebrate and fish toxicity remained relatively high.

Thus, the emerging consensus from three agency (MDEQ, EPA, USACE) experiments are that stamp sands along the beach and nearby sediments are highly toxic to aquatic organisms. Not only do the migrating stamp sand beach deposits retain and release toxic amounts of total and dissolved copper, but nearshore sediments contain high enough concentrations of copper that they also provide risk for a variety of benthic organisms and YOY fishes. The severe effects on many benthic invertebrates and fish are again not unexpected, given published lists of dissolved copper LD

50 (

Table 8). Only a few benthic species (1 stonefly, 1 midge, an amphipod) show tolerance to high total and dissolved Cu concentrations; whereas most invertebrates and all trout and salmon seem very susceptible.

Depression Of Benthic Invertebrates & Fish In The Bay. LiDAR and ROV imagery, and Ponar sampling allowed the construction of bay maps that show percentage stamp sand, Cu concentrations, and effects on benthic biota [

29]. Ponar invertebrate sampling surveys over the past 10 years have demonstrated a severe reduction of benthic taxa where %SS and Cu concentrations are elevated (

Figure 17b; also see [

29,

54]). Maps of %SS versus benthic species abundance clearly show negative effects associated with stamp sand abundance in nearshore bay sediments, along stamp sand beaches and into NE portions of Buffalo Reef cobble fields. Using beach seine techniques, GLIFWC (the tribal consortium) has also documented that eight young-of-the-year (YOY) fish species remain relatively abundant in shallow waters off the lower white beach region, including lake whitefish, whereas there is a virtual absence of all YOY fishes along the stamp sand beaches from the Gay Pile to the Traverse River Seawall [

110]. The absence of food where stamp sand concentrations are high (i.e. lack of benthic organisms) or high concentrations of copper (toxicity) could both be contributing to YOY fish absence. Direct effects of stamp sands on trout fish eggs are now being conducted by USGS investigators, finding strong toxic effects (see Buffalo Reef-Final Alternatives Analysis, State of Michigan,

https://www.michigan.gov>dnr>Buffalo Reef, PDF).

Primary impacts on aquatic organisms appear in a band along the shoreline, Buffalo Reef, and the coastal shelf. So far, little stamp sand has moved off the coastal shelf into deeper waters, although from migrating bar positions, several are approaching shelf edges (

Figure 5). There is also preliminary evidence of fine clay fractions in sediments off of Little Traverse Bay, to the southwest where waters of Grand Traverse Bay exit into Lake Superior. However, Ponar sampling of deep-water benthic organisms, such as the amphipod

Diporeia, suggest relatively high abundances in deep-water sediments, typical of these depths [

111].

Along the coastal strip, stamp sand tailings migrating underwater can have multiple effects on Buffalo Reef biota. Given the massive amounts (10 MMT) moving along the coastline, tailings can simply bury cobble fields where lake trout and whitefish drop eggs [

7,

54]. Toxic effects can also kill eggs and larvae in boundary waters between boulders. Likewise, toxic effects can kill living benthos or organisms around cobbles and boulders, indirectly depriving YOY fishes of their normal food. Fish that don’t like the color or Cu smell of stamp sands, or that can’t find typical forage, may simply move elsewhere. On the positive side, there are indications that whitefish are shifting distributions within the bay, attempting to avoid high Cu concentrations. Good news includes recent indications that some benthic organisms and fish are beginning to return to northeastern shelf regions (former Gay Pile) where waves have removed stamp sands.

5. Conclusions

On the Keweenaw Peninsula, recent research and clean-up efforts have concentrated on 22.7 million metric tonnes of copper-rich stamp sand tailings discharged into Grand (Big) Traverse Bay by two Copper Stamp Mills over a century ago. With the eroding of the original Gay tailings pile, stamp sand deposits now cover beaches from the pile site down to the Traverse River Seawall, whereas another half of the original pile is moving underwater towards Buffalo Reef and the Traverse River Harbor. The stamp sands in the original Gay tailings pile contained about 0.28% copper (i.e 2,800 ppm), i.e. highly elevated concentrations. However, in perspective, tailings deposits from modern copper mines world-wide average about 0.1% Cu, whereas older tailings often retain concentrations between 0.2-0.6% Cu [

112,

113]. At Gay, our and other studies show that stamp sands along the shoreline and in nearshore sediments possess about 2,100 to 3,400 ppm Cu (0.2-0.3%). In interstitial waters along the beach, stamp sands leach concentrations of total Cu between 45-2,580 ppb and dissolved Cu between 24-430 ppb. As noted by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers ERDC studies [

95], these values “greatly exceed the acute water quality criteria for the protection of most aquatic life and are over 16-48 times LD

50 values for many invertebrate species”. The sensitivity of species to copper is undoubtedly heightened because this element is not very common in substrate and waters world-wide. Stamp sands also contain an additional suite of metals, with aluminum consistently exceeding acute and chronic water quality criteria, plus other metals that may bioaccumulate (lead, arsenic, mercury) in food chains [

28,

45,

51].

The original pile of tailings had high Cu concentrations plus a 10% Cu-rich “slime clay” fraction, adding additional concerns about long-distance dispersal [

27]. Dispersing sand-sized particles retain much of their Cu concentrations, although total leaching release remains serious, relative to toxicity. Moreover, lower pH and higher DOC waters, like those from shoreline rivers and streams (Traverse River, Tobacco River, Coal Dock Stream), plus riparian wetland waters in the Nippissing dune regions, potentially leach even higher amounts of dissolved Cu from stamp sands. Recently, High DOC Traverse River water with agitated dredged tailings was transported via kilometers of plastic pipe to the “Berm Complex”, greatly elevating shoreline pond toxicity even more. The high levels in ponds and interstitial waters are toxic for aquatic pelagic invertebrates, benthic invertebrates, and YOY fish. This observation argues against lakeside deposition of dredged stamp sands into a Berm Complex as a long-term viable option. Given the global incidence of coastal mine discharges, there is concern over how legacy effects will play out over extended time periods, as tailings creep along shorelines and remain toxic for at least decades. Moreover, given increased demand for copper and nickel in chips, there is greater mining exploration around the globe. One can easily envision also how combined LiDAR, MSS, and hyperspectral coastal imaging, from satellites, planes, and localized use of low-cost drone (UAS) systems, will continue to provide invaluable geospatial information for future environmental assessments and on-going remediation efforts.

As mentioned earlier, a part of Stage 1 remediation activities at Grand (Big) Traverse Bay since 2017, included over $7.5 million dollars from multiple agencies (EPA GLNPO, MDNR, USACE, GLIFWC, KBIC) for initial dredging, stamp sand relocation, berm pond creation, and research planning activities. In 2022, as a part of Stage 2 efforts, the Buffalo Reef Task Force announced plans for 1) construction of a lengthy (1000+ m) jetty out from the Coal Dock to trap migrating stamp sands from moving onto Buffalo Reef, and 2) removal of stamp sand from the beaches, bay, berm and jetty to a new, large (>200 acre) landfill to be constructed 4 km north of Gay, in the upland forest. Among agencies and academic institutions, there is now consensus that stamp sands are toxic to a great variety of aquatic life and should be removed from Grand (Big) Traverse Bay and placed in the landfill. Since 2017, over twenty journals, magazines, and periodicals have covered developments and updates at the Buffalo Reef site, including 10 Goggle pages on the web. Just recently, the Task Force announced that it has received an additional $20M in funds from the U.S. Dept. of Interior, and $10M from the EPA GLNPO, to match an initial Michigan State (EGLE) commitment of $10M; i.e. $40M total. Thus the Buffalo Reef Project is moving forward into Stage 2, and hopefully will inspire future efforts. Long-term Task Force estimates are for a 20-year, $2-billion Project. As far as ultimate disposal of tailings, we want to point out that the last two copper-gold-silver and nickel-copper massive sulfide mines in the southern Lake Superior Watershed (Flambeau Mine, Ladysmith, Wisconsin; and the Eagle Mine, Michigamme Township, Michigan) decided to place tailings back into the underground excavations (back-fill option). Limestone was additionally added at the Flambeau Mine, to help minimize acid-mine drainage. The “back-fill” option seems a good first step towards adopting the International Council On Mining and Metals (ICMM), UN Environmental Program, and Principles For Responsible Investments (PRI) Program: “Global Tailings Management Standard For the Mining Industry”.

Figure 1.

Geographic location of Grand (Big) Traverse Bay (red to green contours) along the eastern shoreline of the Keweenaw Peninsula. On the Peninsula, early copper mines are indicated by black dots within the Portage Lake Volcanic Series (dashed lines) and large stamp mills by stars. Two mills (Wolverine and Mohawk) are located near Gay. Insert shows anthropogenic copper inventory “halo” around the Peninsula, in µg/cm2 copper (modified from Kerfoot et al. 2019).

Figure 1.

Geographic location of Grand (Big) Traverse Bay (red to green contours) along the eastern shoreline of the Keweenaw Peninsula. On the Peninsula, early copper mines are indicated by black dots within the Portage Lake Volcanic Series (dashed lines) and large stamp mills by stars. Two mills (Wolverine and Mohawk) are located near Gay. Insert shows anthropogenic copper inventory “halo” around the Peninsula, in µg/cm2 copper (modified from Kerfoot et al. 2019).

Figure 2.

Gay Stamp Sand Pile. A) primary wooden discharge launder distributing tailings onto the Gay Pile, around 1922, with smaller sluices conveying stamp sand and slime clays laterally (courtesy MTU Archives). B) Photo of 6-8m high stamp sand bluffs on July 2008 off Gay, showing a buried small lateral sluiceway protruding out of the pile along the shoreline. Lake Superior waters are to the right; the dark beach sands are stamp sands with intermixed slime clay layers. C) Bluff photo from about the same location in 2019, when shoreline erosion (ca. 7-8m/year) reached the buried primary launder support beams, just before bluff removal. (B & C photos, W.C. Kerfoot).

Figure 2.

Gay Stamp Sand Pile. A) primary wooden discharge launder distributing tailings onto the Gay Pile, around 1922, with smaller sluices conveying stamp sand and slime clays laterally (courtesy MTU Archives). B) Photo of 6-8m high stamp sand bluffs on July 2008 off Gay, showing a buried small lateral sluiceway protruding out of the pile along the shoreline. Lake Superior waters are to the right; the dark beach sands are stamp sands with intermixed slime clay layers. C) Bluff photo from about the same location in 2019, when shoreline erosion (ca. 7-8m/year) reached the buried primary launder support beams, just before bluff removal. (B & C photos, W.C. Kerfoot).

Figure 3.

Stamp Sands in situ under natural sunlight: a) wet, redeposited Gay stamp sand beach deposits close-up (12.5 cm wide field), showing colored crushed gangue mineral grains and b) from a distance, with a lens cap (6 cm) for scale, tailings appear as a dark gray (low albedo), coarse-grained (2-4 mm), sand-sized beach deposit (courtesy Bob Regis).

Figure 3.

Stamp Sands in situ under natural sunlight: a) wet, redeposited Gay stamp sand beach deposits close-up (12.5 cm wide field), showing colored crushed gangue mineral grains and b) from a distance, with a lens cap (6 cm) for scale, tailings appear as a dark gray (low albedo), coarse-grained (2-4 mm), sand-sized beach deposit (courtesy Bob Regis).

Figure 4.

Wolverine and Mohawk Mills at Gay, Michigan, around the late 1920’s to early 1930’s: (a) Railroad (Gay) frontside of mill complex, showing railroad station and where rails led up to the top floor of each mill. (b) Backside view of each mill. Steam driven stamps crushed the rock, and an assortment of jigs and tables used water from Lake Superior on different floors to separate out denser copper-rich particles into concentrates shipped to smelters. The slime clay and stamp sand fractions were sluiced out onto a pile behind the two mills. (MTU Archives).

Figure 4.

Wolverine and Mohawk Mills at Gay, Michigan, around the late 1920’s to early 1930’s: (a) Railroad (Gay) frontside of mill complex, showing railroad station and where rails led up to the top floor of each mill. (b) Backside view of each mill. Steam driven stamps crushed the rock, and an assortment of jigs and tables used water from Lake Superior on different floors to separate out denser copper-rich particles into concentrates shipped to smelters. The slime clay and stamp sand fractions were sluiced out onto a pile behind the two mills. (MTU Archives).

Figure 5.

Grand (Big) Traverse Bay: 2010 LiDAR DEM (digital elevation model) color-coded by elevation and water depth (depth scale to right). Red horizontal contour lines are at 5m depth intervals. Gay tailings pile (“original pile”) is indicated, as well as migrating underwater stamp sand bars dropping into an ancient river channel (the “Trough”; at locations #1, and #5). On the eastern flanks of Buffalo Reef, stamp sands are moving out of the “Trough” into cobble/boulder fields (#3, #4). Along the western edges, stamp sands have migrated as a beach deposit to the Traverse River Seawall (#8) and are slipping down into an underwater depression (#7) next to cobble/boulder fields. Stamp sands are also moving around the harbor outlet (#8). Hence, both the eastern and western sides of Buffalo Reef are experiencing tailings encroachment. Lower on the reef (#2, #6), there is little contamination. Past the Traverse River, the sands in the southern bay are almost exclusively natural quartz grains (#9), forming a white beach with shoreline cusp-like features and bar, plus ridges (#10) of natural sand moving from the shelf into deeper waters off the bay and into Lake Superior (modified from Kerfoot et al., 2014).

Figure 5.

Grand (Big) Traverse Bay: 2010 LiDAR DEM (digital elevation model) color-coded by elevation and water depth (depth scale to right). Red horizontal contour lines are at 5m depth intervals. Gay tailings pile (“original pile”) is indicated, as well as migrating underwater stamp sand bars dropping into an ancient river channel (the “Trough”; at locations #1, and #5). On the eastern flanks of Buffalo Reef, stamp sands are moving out of the “Trough” into cobble/boulder fields (#3, #4). Along the western edges, stamp sands have migrated as a beach deposit to the Traverse River Seawall (#8) and are slipping down into an underwater depression (#7) next to cobble/boulder fields. Stamp sands are also moving around the harbor outlet (#8). Hence, both the eastern and western sides of Buffalo Reef are experiencing tailings encroachment. Lower on the reef (#2, #6), there is little contamination. Past the Traverse River, the sands in the southern bay are almost exclusively natural quartz grains (#9), forming a white beach with shoreline cusp-like features and bar, plus ridges (#10) of natural sand moving from the shelf into deeper waters off the bay and into Lake Superior (modified from Kerfoot et al., 2014).

Figure 6.

LiDAR Details of Bay Substrate Types, plus Stamp Sand Movement using DEM Differences: a) A 2016 LiDAR bathymetric DEM broken into dominant surface substrate types. Colored points indicate Ponar sampling sites and percentage of stamp sands across dominant surface substrate types (SS, stamp sand; NS, nature quartz sand; CBL cobble & boulders; BD, bedrock). Black dots indicate where the Ponar dredge was unable to capture a substrate sample, often bouncing off bedrock. Along the coastal margin, notice the scattered pond field, Coal Dock region, shoreline stamp sands, and hill-side Nipissing coastal ridges. b) Superimposed outline of Buffalo Reef boundaries with LiDAR-difference estimates (2008-2016) of erosion at Gay Pile shoreline (red) and deposition of underwater bars (blue) towards and into the “Trough”. One Tg (terragram) is equivalent to one million metric tonnes (MMT). These DEMs aided planning for part of Stage 1 remediation (dredging of Traverse River Harbor; “Trough”). Buffalo Reef boundaries are indicated by the thick black line.

Figure 6.

LiDAR Details of Bay Substrate Types, plus Stamp Sand Movement using DEM Differences: a) A 2016 LiDAR bathymetric DEM broken into dominant surface substrate types. Colored points indicate Ponar sampling sites and percentage of stamp sands across dominant surface substrate types (SS, stamp sand; NS, nature quartz sand; CBL cobble & boulders; BD, bedrock). Black dots indicate where the Ponar dredge was unable to capture a substrate sample, often bouncing off bedrock. Along the coastal margin, notice the scattered pond field, Coal Dock region, shoreline stamp sands, and hill-side Nipissing coastal ridges. b) Superimposed outline of Buffalo Reef boundaries with LiDAR-difference estimates (2008-2016) of erosion at Gay Pile shoreline (red) and deposition of underwater bars (blue) towards and into the “Trough”. One Tg (terragram) is equivalent to one million metric tonnes (MMT). These DEMs aided planning for part of Stage 1 remediation (dredging of Traverse River Harbor; “Trough”). Buffalo Reef boundaries are indicated by the thick black line.

Figure 7.

For LiDAR, two laser pulses (blue-green 532 nm and near-IR 1064 nm) sweep across the lake surface: (

a) The near-IR reflects off the water surface, whereas the blue-green penetrates through the water column and reflects off the lakebed. The difference between the two returning pulses gives the depth of the water column and details of bathymetry (modified from LeRocque and West [

60]); (

b) Simulated LiDAR waveform fitted with Gaussian function (water surface peak), a triangle function (water column reflectance), and a Weibull function for bottom reflectance (after Abdallah et al. [

61]).

Figure 7.

For LiDAR, two laser pulses (blue-green 532 nm and near-IR 1064 nm) sweep across the lake surface: (

a) The near-IR reflects off the water surface, whereas the blue-green penetrates through the water column and reflects off the lakebed. The difference between the two returning pulses gives the depth of the water column and details of bathymetry (modified from LeRocque and West [

60]); (

b) Simulated LiDAR waveform fitted with Gaussian function (water surface peak), a triangle function (water column reflectance), and a Weibull function for bottom reflectance (after Abdallah et al. [

61]).

Figure 8.

Examples of MTRI UAS drone options: Bergen Hexacopter and Quad-8, assorted small (sUAS) quadcopters (e.g. DJI Mavic Pro, DJI Phantom 3A). Example sensors carried by drone platforms are shown in right panel.

Figure 8.

Examples of MTRI UAS drone options: Bergen Hexacopter and Quad-8, assorted small (sUAS) quadcopters (e.g. DJI Mavic Pro, DJI Phantom 3A). Example sensors carried by drone platforms are shown in right panel.

Figure 9.

Microscope Grain Counting Technique: a). Sample of sand grains from the Sand Point site in lower Keweenaw Bay (ca. 55% stamp sands) under transmitted light from a microscope, showing the contrast between rounded natural sand (transparent quartz) and dark sub-angular stamp sand grains (dark, irregular edges, slightly larger). b). Size frequency distributions for the two particle types (stamp sand, red; natural quartz sand, blue) from the Sand Point site. c). The observed grain counts (mixture of natural sand, stamp sand) appear to follow a binomial distribution. d). The Coefficient of Variation (CV) for the %SS calculation is predicted from the equation under “Theoretical”. Field counts (see “Observed”, left) correspond generally to expected values. Over the interval from 10 to 90 %SS, the predicted CV (right) is between 15% to 2% (ca. mean of 5%).

Figure 9.

Microscope Grain Counting Technique: a). Sample of sand grains from the Sand Point site in lower Keweenaw Bay (ca. 55% stamp sands) under transmitted light from a microscope, showing the contrast between rounded natural sand (transparent quartz) and dark sub-angular stamp sand grains (dark, irregular edges, slightly larger). b). Size frequency distributions for the two particle types (stamp sand, red; natural quartz sand, blue) from the Sand Point site. c). The observed grain counts (mixture of natural sand, stamp sand) appear to follow a binomial distribution. d). The Coefficient of Variation (CV) for the %SS calculation is predicted from the equation under “Theoretical”. Field counts (see “Observed”, left) correspond generally to expected values. Over the interval from 10 to 90 %SS, the predicted CV (right) is between 15% to 2% (ca. mean of 5%).

Figure 10.

Daphnia pulex survivorship and fecundity experiment in stamp sand ponds at Gay. Forty 40mL vials had one adult Daphnia in each container and were submersed in shallow water of the ponds. Each vial had a 100µm mesh Nitex netting over the top, secured by rubber bands. A temperature probe (STOW AWAY-IS Model’ Onset Computer Corporation). was placed near the set to check daily temperature fluctuations during the experiments.

Figure 10.