Supervised learning was used to solve most problems including temporal (time step based) updates with data being the current time step with the label identified based on the actual outcome or simply the next time step. However, such methods lose the transference of the temporal nature of these data points leading to a very poor learning experience and generating poor results for testing data sets or future predictions.

This paper focuses on TD (Temporal Difference) based learning as a method for numerical predications unlike earlier discussions [

2], which focused on Inductive learning to predict diagnostic rules, or predicting the next character from a partially generated sequence. Rather this paper demonstrates the ability to perform prediction based on numerical attributes in combination with weight parameters. Another aspect of this paper is the focus on multi-step temporal problems rather than single-step problems as their novelty is better demonstrated on multi-step problems.

1.1. TD (Temporal Difference)Algorithms

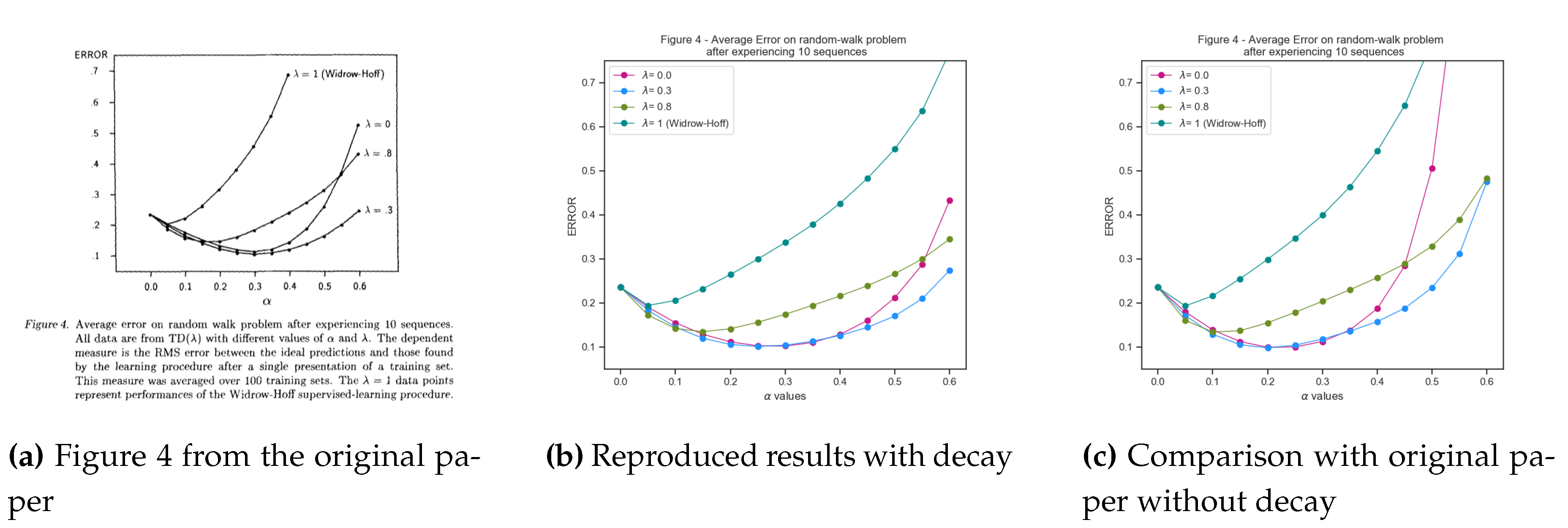

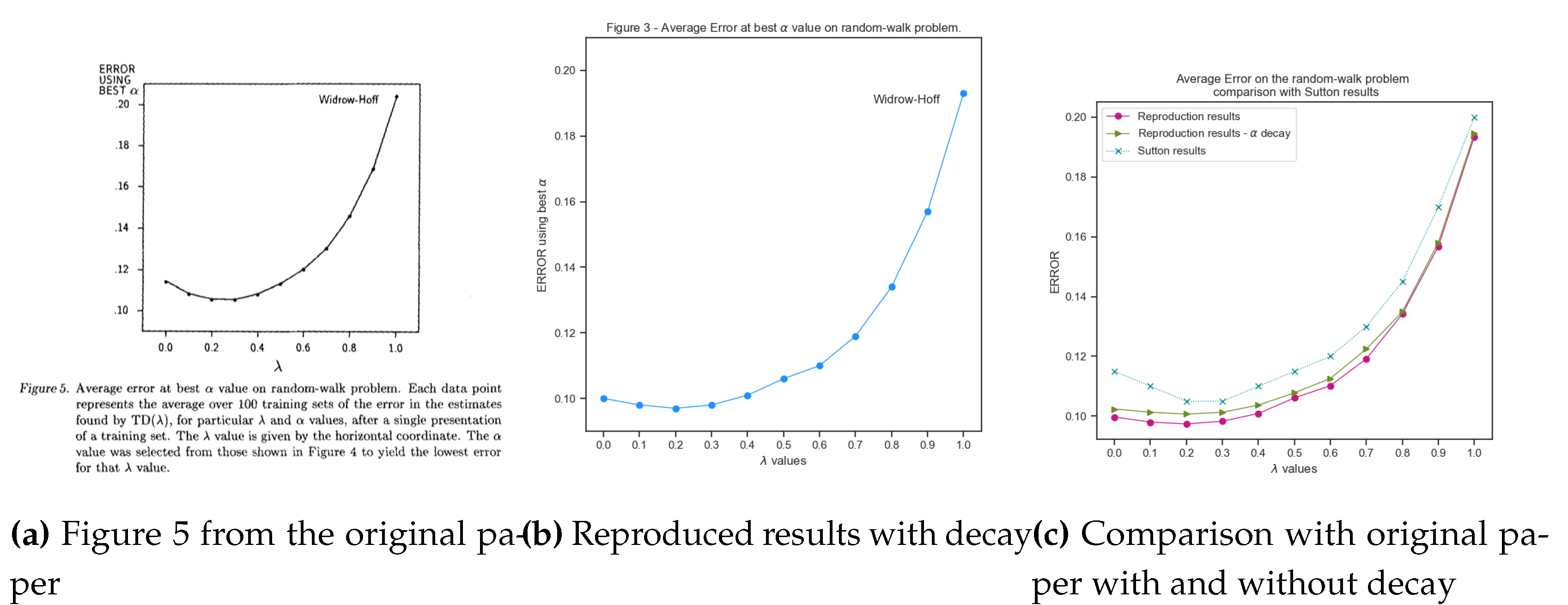

The classical Windrow-Hoff rule is used as the baseline for comparison to the TD and supervised learning algorithms. Both Widrow-Hoff and TD generates the same set of weight changes, however the first experiment shows how TD achieves this in an incremental fashion. The next experiments demonstrate how TD() produces a varying range of weight changes enabling the process to identify the best suited parameters with higher accuracy ranges than any supervised learning procedure.

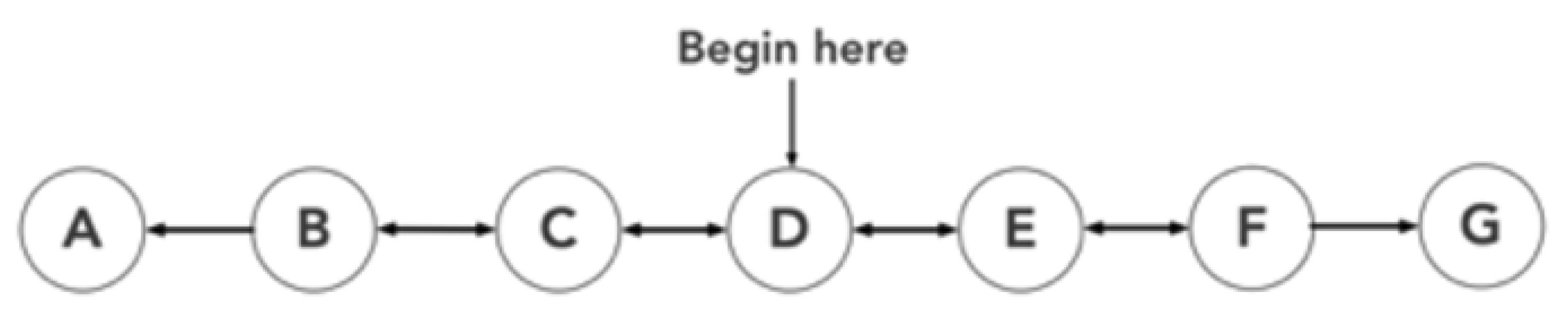

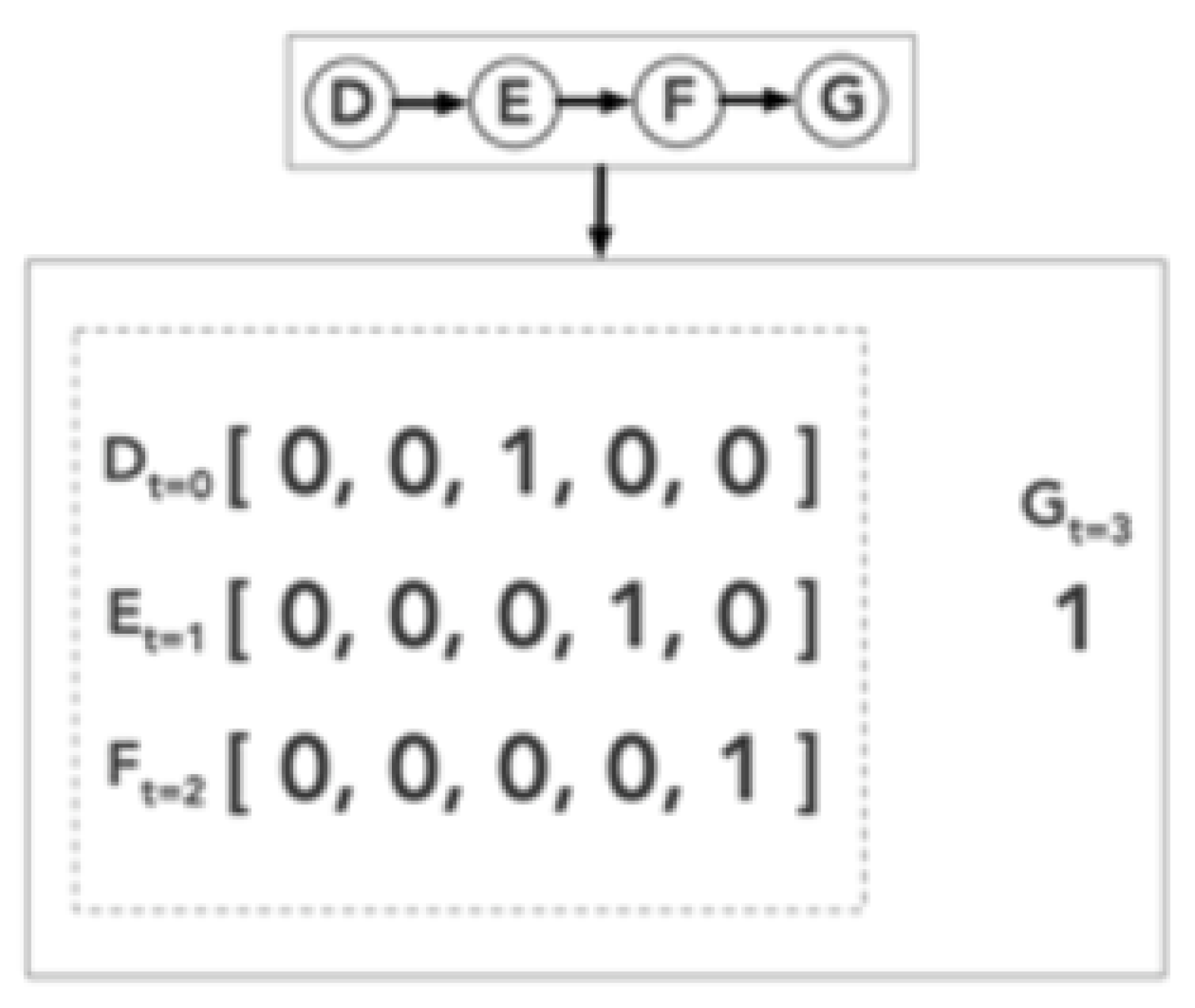

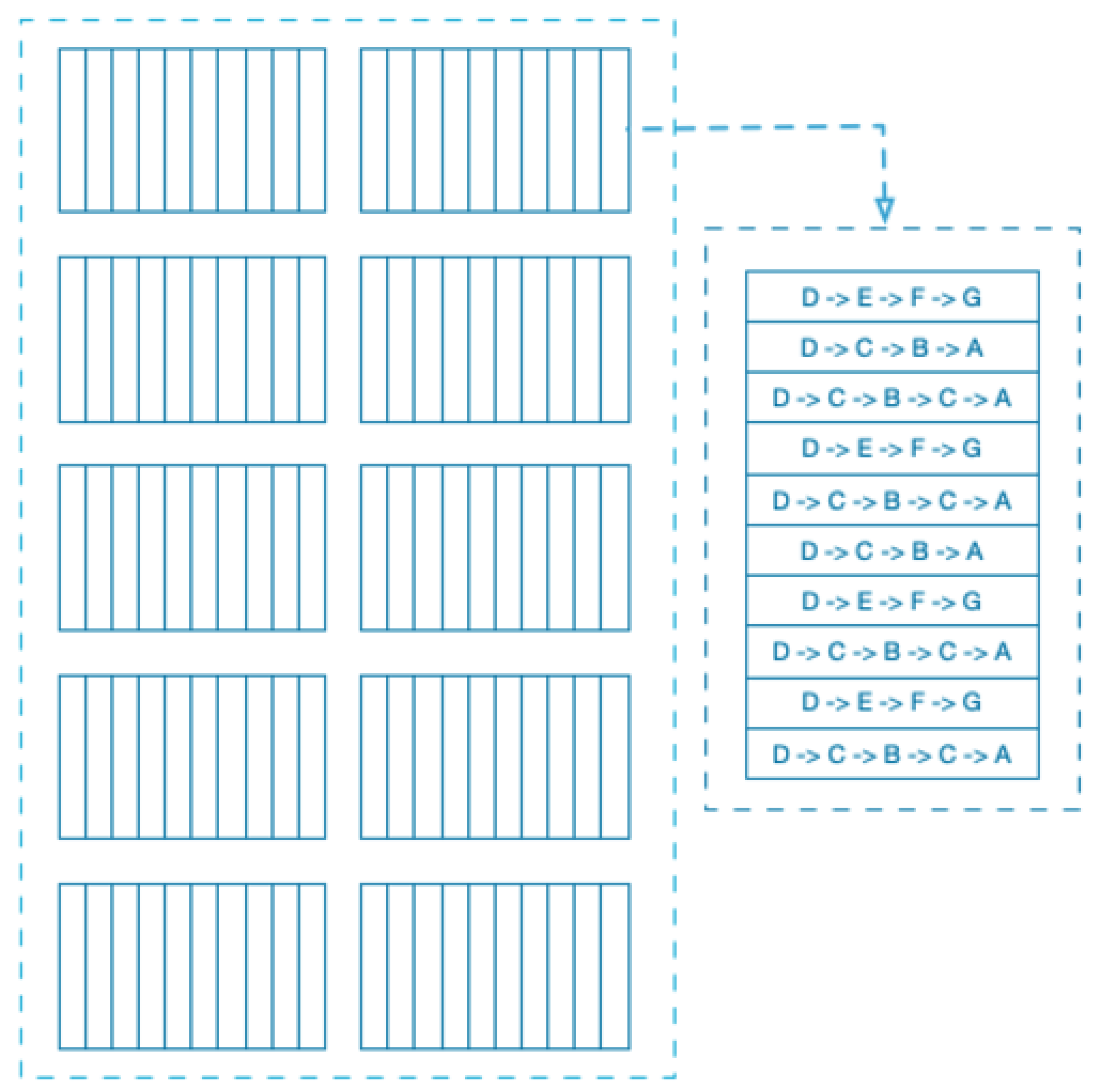

A typical multi-step problem is constructed as a set of observation vectors and their outcome such as where represent the observations while z indicates the outcome. Since the TD is an incremental and temporal based algorithm, it equivalently produces a vector of predictions representing an estimate of z at that time instance. The predictions can be constituted as function of all the earlier predictions and outcomes along with the current sequence, though for this particular discussion, P is determinant only on the current sequence of observations captured as , represented as as this is also considered to be a Markovian process.

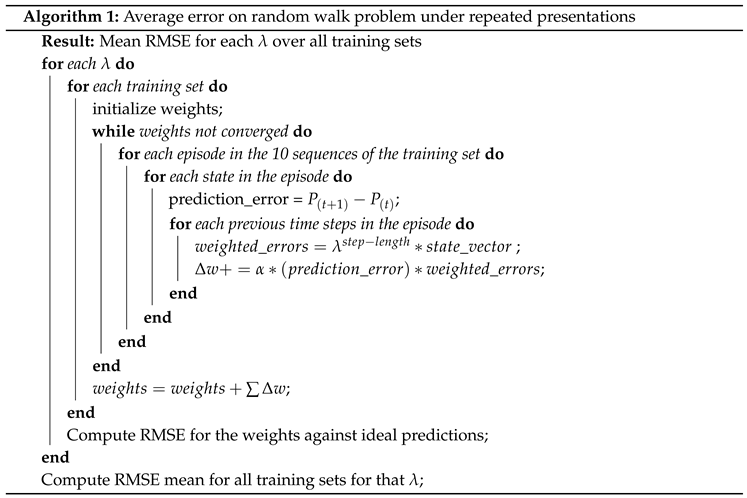

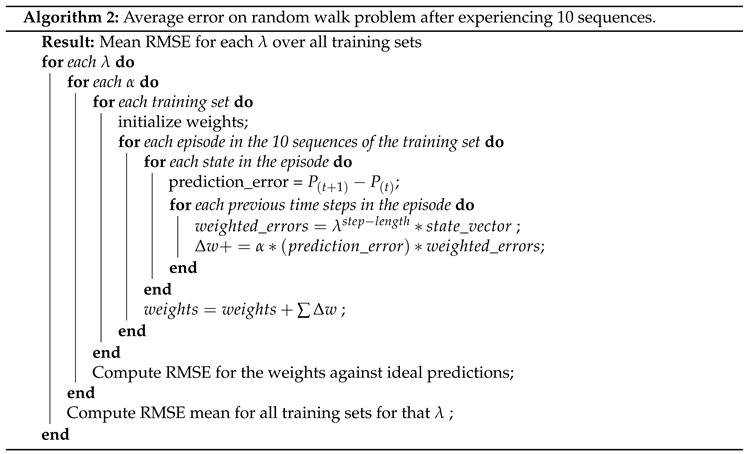

The algorithm uses function approximation by using modifiable weights w as part of the predictions, formulating predictions as a function of and w. The intuition lies in the repeated presentations of experiences/observations to learn the appropriate weights, to learn the variance with low bias, and predict outcomes based on future observations. This learning structure enables the algorithm to define the learning process as updates to the w weights vector.

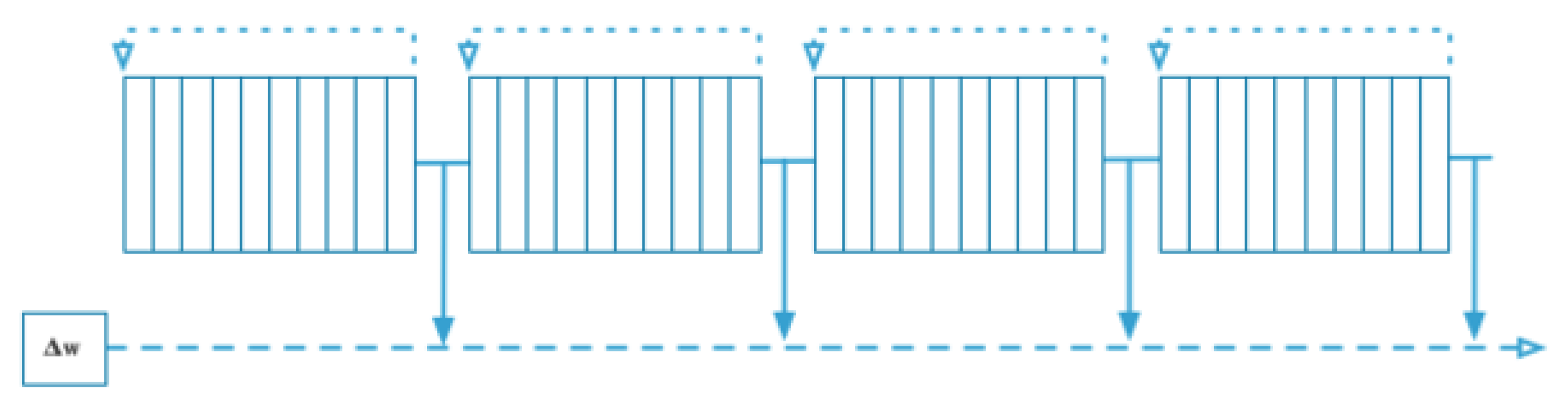

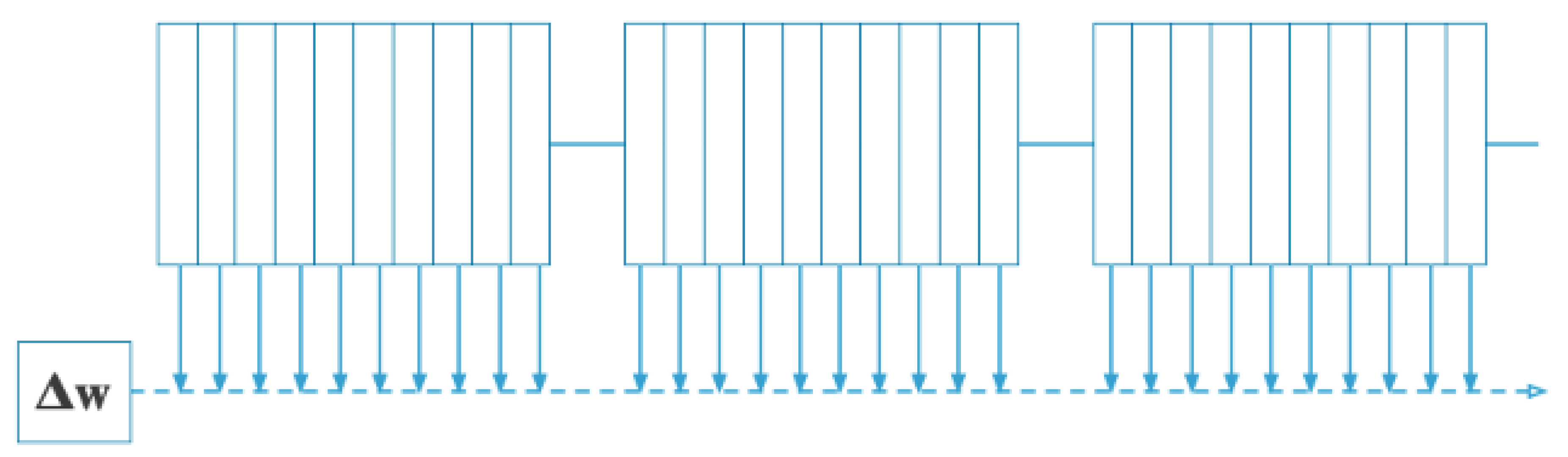

The update process to the weights w, after each observation is determined by

, representing an increment/decrement to the weights and at the end of each observations-outcome pair, the

is applied to the weights as

. The paper also demonstrates both incremental updates to the weights and delayed updates after accumulating

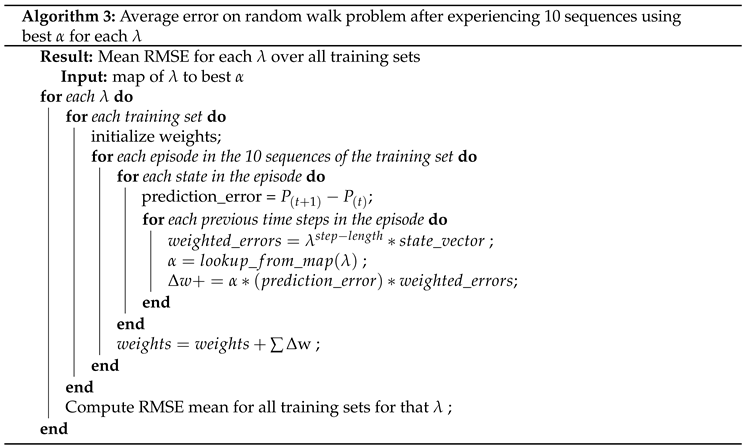

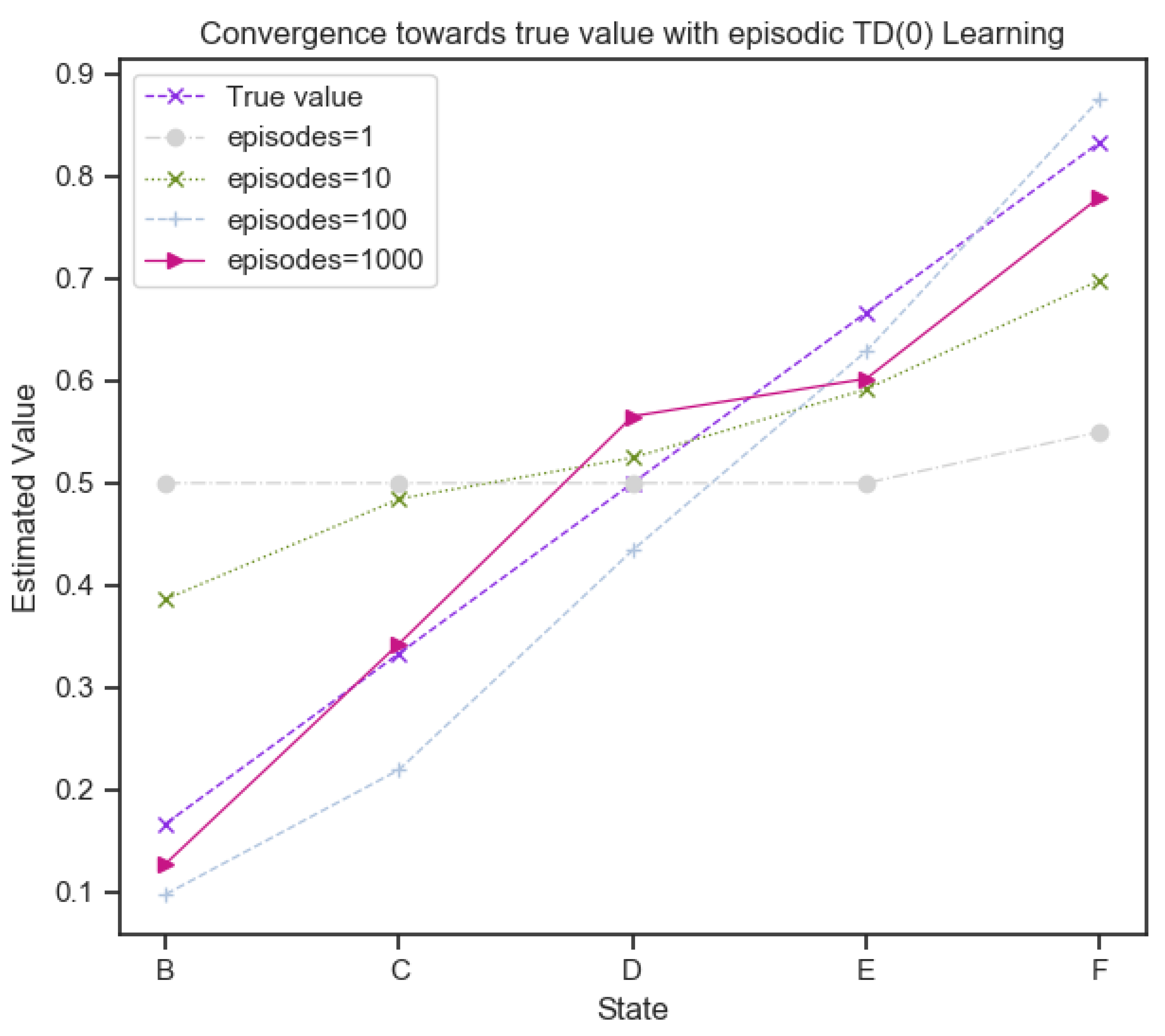

over a training set of multiple sequences. A simple depicting of how TD algorithm learns the true values after multiple presentations, is depicted in Figure (

Figure 1), where the number of presentations increase and the predictions get closer to the true value.

1.1.1. Comparison with Supervised Learning

Supervised learning treats the observation outcome sequence as pairs such as while the weight updates are determined based on the error between the predictions at each time step, and the rate of error updates is determined by a learning rate () and given as where represents the partial derivatives of with respect to each w. If the predictions are considered a linear function (similar to above) of w and at each time step t, then they can be represented as and performing a partial derivative of this equation with request to on both sides, converts the equation to and substituting these two values in the expression gives us the Widrow-Hoff rule , also known as the delta rule.

The intuition lies in the error difference between the actual outcome

z and the prediction

, represented by

and its weightage by the observation vector

to determine the direction and magnitude of the weight updates to minimize the error. This intuition directly translates to TD, where the error difference between current prediction and outcome can be computed incrementally as a sum of difference in predictions where each

depends only on each successive prediction pairs and previous values of

as (

2)

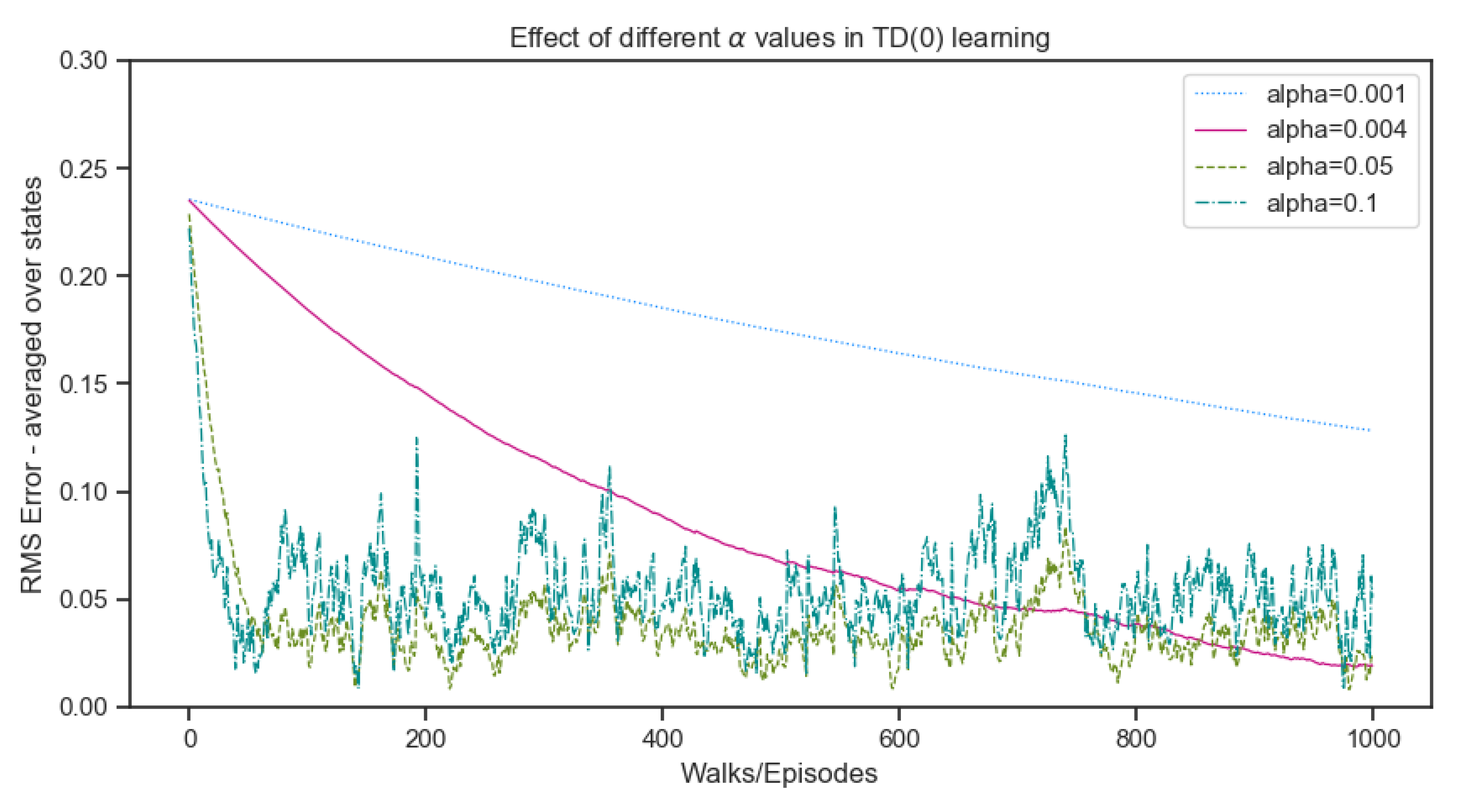

1.1.2. Extension of TD to TD() Algorithms

While TD discussed until now, utilizes all the previous values of

, the paper introduces a more wider range of tuning capability in the TD algorithm with the introduction of

, representing the dynamic weightage applied to

, representing the temporal difference predictions. The TD(

) algorithm garners more sensitivity to the most recent prediction change while a lower weightage to a prediction change few steps earlier, using an exponential weighting based on their recency and frequency heuristics. Introducing the new parameter

and updating the earlier equation produces (

2)

Having , represents equal weightage and generates the same equivalent equation to the Widrow-Hoff rule and defined as TD or TD(1).

While TD(1) utilizes all the previous predictions, TD(0) where , essentially utilizes only the most recent observation to determine the weight update and represented as . .This provides the intuition that any value for between will produce different weight changes and their error rates with the outcome would be different based on the problem space and available training datasets etc., These equations clearly demonstrate the ability of TD to benefit from the temporal structure of the observations which typical supervised learning algorithms ignore.

1.1.3. Instability Prevention for Incremental Updates

As illustrated above, TD learning method performs incremental weight updates every step, using the weighted previous predictions. However, as the paper explains, intra-sequence updates such as

where

is represented by (

1) need to be handled carefully, since they are influenced by the change in the observation

and the

as well, which would lead to instability. To prevent the instability due to such oscillation of weight values, the equation is modified to update the weights only for predictions generated by

, the observation involved. The modified equation is given by (

3)

1.1.4. Note on Lambda () and Discount Factor ()

In a MRP (Markov Reward Process) or MDP (Markov Decision Process) the discount factor () helps determine the value function for a particular state based on immediacy of the rewards. It helps compute the value applicable to a particular state dependent on its distance from the actual reward available in the future, immediate or delayed i.e., , the discount factor, helps weigh delayed rewards versus immediate rewards and determine value functions for a state. The parameter helps in evaluating the right level of bias to be adopted in choosing the previous predictions to be utilized, while predicting the outcome based on recent observation. Intuitively, the discount factor () helps determine the objective to be achieved in the MDP, by discounting possible future rewards to help determine a particular action in MDPs or compute the value function for a MRP. The discount factor is independent of parameters of a learning algorithm and specifically used as part of the MDP definition itself. The lambda () parameter on the other hand functions similar to a hyperparameter of a learning algorithm, lower the errors to the least minimum possible. However, they function outside the MDP and influence only the range of the learning algorithm and does not affect the reward function.

1.1.5. Temporal Difference (TD) Comparison with Widrow-Hoff & Monte Carlo

Similar to TD, Monte Carlo represents a set of methods to solve learning problems based on averaging sample returns and utilized in reinforcement learning similar to TD learning. The primary contrast between TD and MC methods, are the incremental prediction updates performed in TD, while MC methods requires the experience of a completed episode with actual returns as part of their learning procedure. While TD perform updates during the sequence of the observations, MC would update only at the completion of an episode and hence cannot be used in an online learning system. Widrow-Hoff and TD learning are similar in the aspect of being online-learning procedures since the perform updates based on the observations and primarily move towards minimizing the RMSE for the observation-outcome pairs. However, whereas Widrow-Hoff is modelled as a linear function, Monte Carlo methods are more generalized for any model-free learning problems. Though TD(1) and Widrow-Hoff produces the same updates, as per the paper, TD can be generalized as well to perform learning for non-linear functions. As Sutton & Barto note in [

3], TD learning is biased towards the parameters and the bootstrapping performed, and runs the risk of high bias. While Monte Carlo does not have this issue, it suffers from high variance and requires a large number of samples to achieve similar levels of TD learning. In conclusion, though Monte-Carlo performs very similarly to TD(1), there are subtle differences in their learning process and underlying assumptions.