1. Introduction

Life satisfaction is the self-assessment of an individual’s life based on their personal standards which also serves as a key indicator of their overall well-being (Diener et al., 1985). It primarily focuses on the psychological dimension, highlighting subjective experiences of life contentment and fulfillment (Diener et al., 1985). Life satisfaction has been markedly used to gauge the quality of life at the individual, societal, and national levels (Veenhoven, 1996). Specifically, low satisfaction with life marks serious shortcomings that can impact the quality of life (Ghimire et al., 2018). Higher life satisfaction is positively associated with increased life expectancy and can lower all-cause mortality risks (Lee & Singh, 2020). It is also widely recognized as a crucial indicator in shaping policy decisions aimed at improving psychological well-being, health behaviors, and physical outcomes (Kim et al., 2021).

Several factors influencing life satisfaction vary across different age groups, due to differences in accumulated life experiences, as well as across diverse social and cultural contexts (Ji et al., 2022; Poon & Cohen-Mansfield, 2011). Specifically, collectivist cultures, predominantly Asian cultures emphasize group needs, social harmony, and interdependence over individual desires and preferences that are central to individualistic cultural norms (Schwartz et al., 2010). Filial piety, a core value in many collectivistic cultures, defines the responsibilities of children toward their parents in old age (Schwartz et al., 2010). Given Nepal's deeply entrenched filial piety culture, as elaborated in the following paragraph, older adults often rely on familial support for their livelihoods (Ang & Malhotra, 2022; Singh et al., 2021). A previous study showed that more than 80% of Nepali older adults, whether individuals or couples, were living with their family members (Singh et al., 2021). However, the extent to which older adults rely on their families may have profound implications for their autonomy, self-esteem, and overall life satisfaction and quality of life (Alonso et al., 2022; Chokkanathan & Mohanty, 2017; Heide, 2022). Thus, it becomes crucial to understand the relationship between family support and the life satisfaction of older adults within this cultural context.

Family, as a social institution, plays a central role in providing support and care to older family members in Nepal, catering to their day-to-day needs and offering various forms of assistance, including social, economic, physical, and mental support. Socially, older adults often turn to their families for companionship, emotional support, and a sense of belonging (Chalise et al., 2010; Singh et al., 2021). Economically, Nepali older adults often rely on their adult children for resources and financial assistance for their sustenance. Family members commonly play a central role in helping with instrumental activities of daily living, such as shopping, meal preparation, and transportation, as well as basic activities of daily living, including bathing, dressing, and mobility when needed (Shrestha et al., 2024). Furthermore, dependence can also arise from the need for cognitive and emotional support to maintain a satisfactory quality of life (Ghimire et al., 2018). While children are expected to support their parents in need, on the flip side, studies have shown that many Asian older adults worry about burdening their children (Ang & Malhotra, 2022; Thomas, 2010). Therefore, there is a paradox surrounding the expectations of filial piety and family support.

Social stress theories have advanced our understanding of social determinants of well-being. The social stress process theory, as proposed by Pearlin and Bierman (2013) suggests that various stressors from different sources, including informal social circles, local neighborhoods, social and economic institutions, and broader societal conditions, can interact to affect well-being. This theory further highlights stress proliferation, wherein stressors can trigger additional stressors, ultimately affecting individuals' well-being. For example, a family having one member with a serious illness can face additional stressors such as financial strain, shifts in roles and responsibilities among other family members, interpersonal conflicts, and strained relationships. Drawing upon Pearlin and Bierman's (2013) social stress process theory, a previous study in rural India demonstrated the interplay of stressors, notably originating from familial ties, in shaping individuals' life satisfaction (Chokkanathan & Mohanty, 2017). The study revealed that dependence on family members strains familial relationships, leading to reduced life satisfaction.

Research on life satisfaction among older adults is scarce in Nepal, particularly in rural areas. Previous studies in Nepal indicated that life satisfaction among older adults was influenced by factors such as age, marital status, education level, employment, family income, ownership of property, sufficient money for expenditure, and role in family decision-making (Ghimire et al., 2018; Karmacharya & Thapa, 2022; MK et al., 2019). However, these studies were carried out in urban settings. It is well-documented that significant disparities exist between urban and rural areas in Nepal across various demographic and socioeconomic dimensions (Devkota et al., 2021). Therefore, research is crucial to understanding the unique challenges and experiences of Nepal's rural older population. Previous studies did not adequately explore the broader effects of family support within Nepal's cultural context, nor did they thoroughly examine how this reliance affects overall life satisfaction (Ghimire et al., 2018; Karmacharya & Thapa, 2022; MK et al., 2019).

Furthermore, Nepali society, marked by strong patriarchy, harbors deep-rooted gender inequality within its cultural framework (Bishwakarma, 2020). Nepali societal expectations emphasize men as providers and self-reliant individuals. Older women generally report higher satisfaction and show adeptness in family integration, including with grandchildren, sons, and daughters-in-law (Kumari & Kumar, 2023). However, previous studies provided insufficient analysis of gender differences in the relationship between family support and life satisfaction, providing opportunities for further research to elucidate these intricate dynamics.

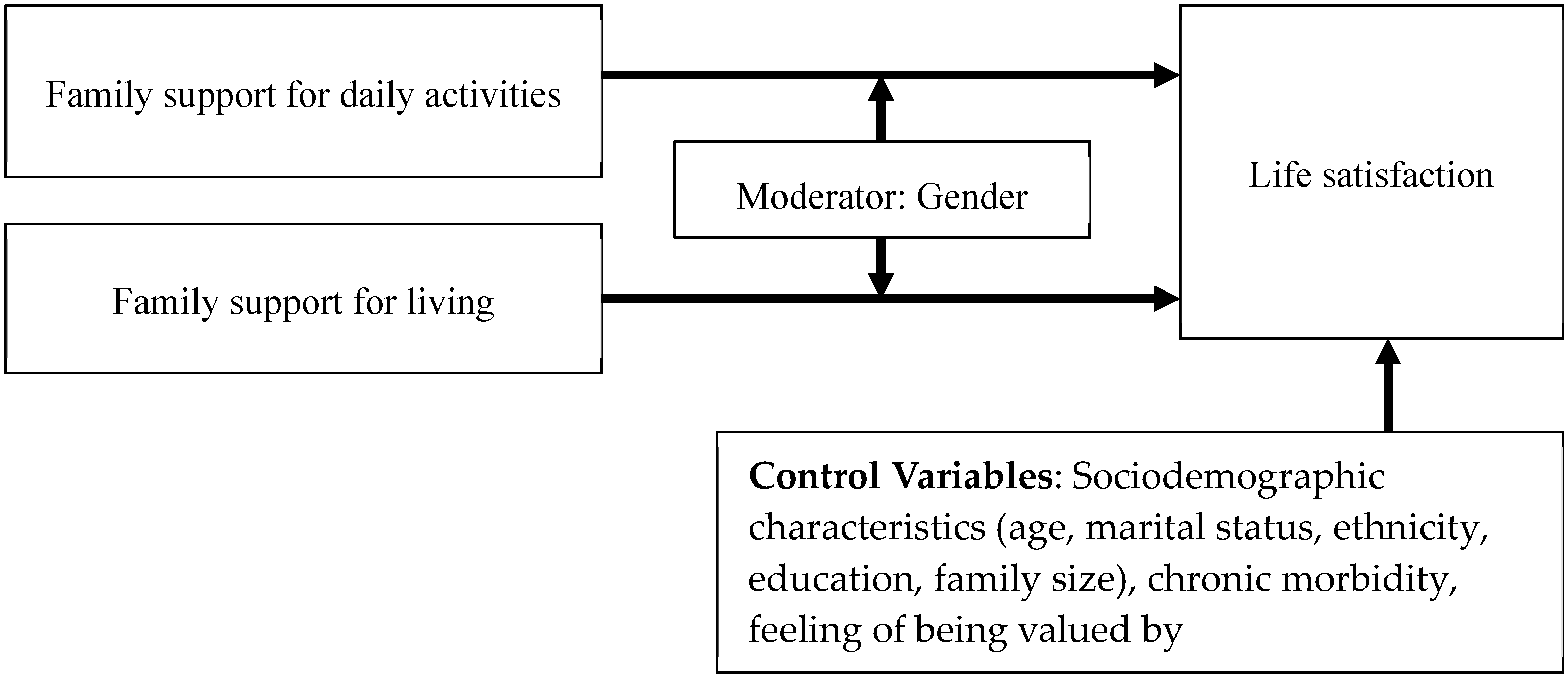

Thus, this study aimed to examine whether reliance on family support for daily activities (e.g., bathing, dressing, personal hygiene) and living expenses (e.g., transportation, medical costs, groceries, and housing) is associated with life satisfaction among Nepali older adults. Additional aim of this study was to assess whether the relationship between family support and life satisfaction differs by gender. We hypothesized that older men who rely on family support for these needs would report lower life satisfaction compared to older women under similar circumstances. The conceptual model in

Figure 1 illustrates the proposed relationships, including gender as a moderator and relevant control variables.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Sample, and Sampling

This study used data from a cross-sectional study conducted between July and September 2020 in rural settings of two districts (Sunsari and Morang) of Koshi Province in eastern Nepal. Sunsari and Morang are two of the most populous districts in Nepal, with a particularly large number of older adult population, 9.5% and 10.8%, respectively, which is similar to the national figure of 10.2% (CBS, 2021). The general demographic information for these districts, along with data for the province and the country, and a comprehensive understanding of the study methods can be found elsewhere (Sapkota et al., 2024; Yadav et al., 2019).

The sample size was determined using a hypothesized proportion of 0.5, a 5% margin of error, and a design effect of 2. To account for potential non-response, a 10% non-response rate was included. In total, 847 community-dwelling older adults participated in the survey, with a response rate exceeding 90%. Participants were recruited using a multi-stage sampling method. Two rural municipalities per district were randomly selected, followed by four wards in each municipality chosen proportionally to size. Individuals aged 60 years or older who were citizens of Nepal and had lived in the study area for at least one year were included in the study. Exclusions comprised individuals residing in nursing facilities and those with mental health conditions, hearing impairment, or communication difficulties. Additionally, for this study, individuals living alone (n=27, 3.2%) were excluded from the study since this study was focused on familial support and its influence on life satisfaction. Family support for living had one missing value; therefore, that observation was excluded from the study. Hence, the final analytical sample included 819 respondents.

2.2. Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by 12 surveyors who were government-employed healthcare providers in the selected districts with three-year General Medicine certificate and proficiency in local languages. Surveyors were trained via two Zoom sessions led by investigators. The training covered sessions on study tools, participant recruitment, ethics, and data collection techniques. The questionnaires used in the interviews were initially translated from English to Nepali and then verified through back-translation to ensure accuracy. The Nepali version of the questionnaire was pilot tested among ten older adults who were not included in the final data analysis. Interviews were conducted in the Nepali language, and the data were collected using the Kobo Toolbox mobile app (KoboToolbox, 2020).

2.3. Variables

Life satisfaction was the dependent variable. Family support for living and daily activities were independent variables of interest. Gender (male/female) was considered as a moderator variable. Control variables included: sociodemographic characteristics, including age, marital status, ethnicity, education, family size, chronic morbidity, and a sense of being connected or valued. These variables were chosen based on prior research conducted in this space (Ghimire et al., 2018).

2.3.1. Life Satisfaction

The 5-item satisfaction with life scale (SWLS-5), a widely used standard tool, measured respondents’ satisfaction with life (Diener et al., 1985). The SWLS-5 tool utilized in this study assessed various dimensions of an individual’s life satisfaction, including aspects such as life ideality, personal goals, and conditions. Specifically, five items in the construct stated: “In most ways, my life is close to my ideal,” “The conditions of my life are excellent,” “I am satisfied with my life,” “So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life,” and “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing.” Respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement with each of the five items using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). To obtain a total score, the scores of the individual items were summed up, resulting in a cumulative score range of 5 to 35. The score was dichotomized as "Satisfied" (scores of 20 and above) and "Dissatisfied" (scores less than 20); following the categorization done in previous studies (Aina et al., 2023; LaVela et al., 2019). This dichotomized life satisfaction variable was used in binary logistic regression model.

The SWLS-5 has shown strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.87, as well as temporal reliability with a coefficient of 0.82 (Pavot & Diener, 2009). It also exhibits good convergent validity when compared to other subjective well-being assessments (Pavot & Diener, 2009). In a previous study involving older adults aged 60 and above in Nepal, the SWLS-5 was found to have excellent reliability, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.93 (Ghimire et al., 2018). In this study, SWLS-5 exhibited high internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89.

2.3.2. Family Support for Living and Daily Activities

Respondents were asked two specific questions: 1) “Do you depend on your family for living like transportation, medical expenses, groceries, and housing?” and 2) “Do you depend on your family for daily activities like bathing, dressing, personal hygiene, etc?” Respondents answered with either "yes" or "no" to each question.

2.3.3. Moderator

Gender was considered as moderator, including male and female.

2.3.4. Control Variables

Sociodemographic characteristics, such as age (categorized into three groups: 60-64, 65-69, and 70+), marital status (with/without spouse), ethnicity (Dalit, Madhesi, Aadiwashi/Janajati, and Brahmin/Chettri/Thakuri), education (formal/no formal education), and family size (number of family members in the household) were included as control variables.

The sense of connection or value was also controlled in the binary logistic regression analysis. It was assessed by a question, “Do you think that you are connected to or valued by your family/friends/relatives or social networks/group you are involved in?” with a three-point Likert scale: “Most of the time”, “sometimes”, and “never feel like that.”

Considering that health status, especially chronic illnesses, has been linked to life satisfaction (Chokkanathan & Mohanty, 2017), chronic morbidity was also considered a control variable. Respondents were asked if they were ever told or diagnosed by a physician with any of the nine chronic conditions, i.e., hypertension, heart disease, stroke, lung disease (asthma, COPD, etc.), arthritis, diabetes, high cholesterol, kidney disease, and cancer. The response for each condition was reported in “Yes / No” format. The number of chronic conditions was summed up and further categorized into three categories (no morbidity/single morbidity/ multimorbidity).

2.4. Statistical Analyses

SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., 2013) was used for data analyses. Missing values were handled by the listwise deletion method. For each variable, descriptive statistics such as means with standard deviations and frequencies with percentages were computed, based on their respective measurement types. For bivariate analyses, chi-square tests were conducted for categorical predictors, and independent samples t-tests were used for numeric predictors with respect to the binary dependent variable.

Binary logistic regression was performed to examine the relationship between predictor and dependent variables and to assess whether gender moderated these relationships. Key independent and control variables were included in the model based on theoretical relevance. Multicollinearity was assessed using the "proc reg" statement, with variance inflation factors for all variables found to be below 2.5, indicating no significant multicollinearity concerns (Johnston et al., 2018). As a result, all key variables were retained for the logistic regression model. Advanced diagnostics, including dfbetas, influence, and leverage plots generated through the "proc logistic" statement, revealed no issues with influential observations. Model predictability was assessed using concordance statistics (c-statistics), with values ranging from 0.61 to 0.80 considered good and 0.81 to 1.00 considered very good (Kwiecien et al., 2011). Statistical significance was determined using a p-value threshold of <0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Study Respondents’ Characteristics

The characteristics of respondents and bivariate analyses by life satisfaction are presented in

Table 1. Among the total respondents (n = 819), the sample was almost evenly distributed across three age groups. More than half of the respondents were men (55.7%), majority were married (77.9%) and had no formal education (89.3%). The highest percentage of older adults identified themselves as Madhesi ethnicity (41.5%), followed by Aadiwashi / Janajati (25.4%), Dalit (23.0%), and Brahmin / Chettri / Thakuri (10.1%). The mean household family size reported was about 7. Only one-fifth of participants reported feeling valued most of the time, while the majority felt valued only occasionally (63.1%) or never (16.9%). Nearly half (46%) reported having one or more chronic conditions. Dependency on family was also common, with 47.4% relying on family for daily activities and 79.2% dependent on family for living. Despite these challenges, more than half (57.1%) of respondents expressed satisfaction with their lives.

Bivariate analyses revealed several significant associations between various factors and life satisfaction. Among the control variables, life satisfaction varied significantly based on participants' ethnicity, education, family size, sense of being valued, and presence of chronic conditions. Family support for daily activities was strongly associated with life satisfaction (p < 0.001), whereas no statistically significant relationship was observed between family support for living and life satisfaction.

3.2. Binary Logistic Regression for Family Support and Life Satisfaction

Results from the unadjusted and adjusted binary logistic regression models are presented in

Table 2. Separate models were run for family support for daily activities (Model 1) and for living (Model 2). The predictability of both models was good, with c-values of 0.758 and 0.747 for Model 1 and Model 2, respectively. In the adjusted model, family support for daily activities was significantly associated with life satisfaction (

Table 2, Model 1). Older adults who relied on family support for daily activities had 51% lower odds of being satisfied with their lives compared to those who did not require such support (OR: 0.49, 95% CI: 0.35–0.69, p < 0.001). In contrast, family support for living showed no significant association with life satisfaction (

Table 2, Model 2).

Among the control variables, ethnicity played a key role, with Aadiwashi/Janajati and Brahmin/Chettri/Thakuri groups reporting higher life satisfaction compared to participants from the Dalit ethnic group. Both family size and chronic morbidity, including single and multimorbidity, were associated with lower odds of life satisfaction. Additionally, a strong sense of being valued was crucial for life satisfaction, with those feeling devalued having significantly lower odds of satisfaction.

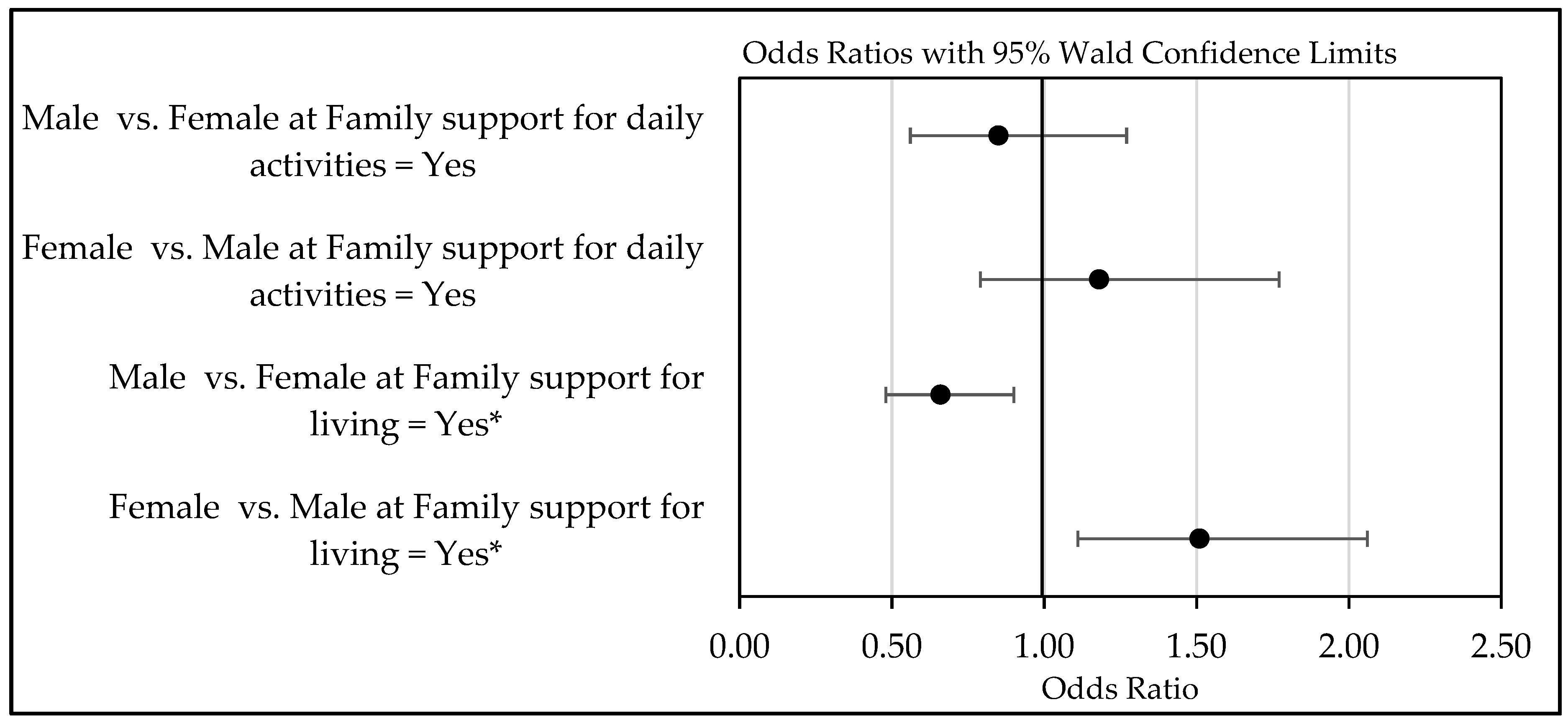

3.3. Family Support and Life Satisfaction: Moderation by Gender

Figure 2 illustrates the moderation effect of gender in the relationship between life satisfaction and family support for daily activities and living. The forest plot shows no statistically significant gender difference in how family support for daily activities influences life satisfaction; i.e. for male vs female (OR: 0.85, 95% CI: 0.56-1.27, p > 0.05) and female vs. male (OR: 1.18, 95% CI: 0.79-1.77, p > 0.05).

However, the plot reveals a notable difference in the relationship between family support for living and life satisfaction. For men, the odds of life satisfaction with family support for living are lower than for women in similar situations. Specifically, older men who relied on family support for living had 34% lower odds of experiencing life satisfaction compared to older women in similar situations (OR: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.48-0.90, p < 0.05). In other ways, among older adults who relied on family support for living, women were 51% more likely to be satisfied with their lives than men (OR: 1.51, 95% CI: 1.11-2.06, p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

This study investigated the association between family support and life satisfaction of older adults in rural eastern Nepal. While relying on family support for daily activities was associated with lower odds of life satisfaction, depending on family for living did not generally impact life satisfaction—except when considering gender. Among older adults who relied on family support for living, men were less likely to feel satisfied with their lives compared to women.

We found that more than half of respondents reported being satisfied with their lives, while 42.9% expressed dissatisfaction—more than double the prevalence found in previous studies in Nepal (Ghimire et al., 2018; MK et al., 2019). This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in the study settings, as the current research was conducted in a rural area, whereas the earlier studies focused on urban populations. Rural older adults may report lower life satisfaction than their urban counterparts due to limited access to healthcare and social services in rural settings, which can diminish their sense of security and overall well-being (Rey-Beiro & Martínez-Roget, 2024).

Reliance on family support for daily activities was associated with decreased odds of life satisfaction, a finding consistent with the social stress process theory (Pearlin & Bierman, 2013). This aligns with previous research indicating that poor health status can increase family strain, which in turn negatively affects subjective well-being (Chokkanathan & Mohanty, 2017). Higher dependency on family members appears to exacerbate this strain, highlighting the critical role of dependency in mediating the relationship between health status and life satisfaction among older adults (Chokkanathan & Mohanty, 2017). While traditional Nepali cultural norms rooted in filial piety emphasize the importance of family support for the well-being of older individuals (Singh et al., 2021), an overreliance on familial assistance may inadvertently reduce life satisfaction. This paradox could stem from compromised autonomy, where individuals feel a loss of independence, or from feelings of being a burden on their family (Bishwakarma, 2020; Heide, 2022). These dynamics suggest a nuanced relationship between family support and subjective well-being. However, the mechanisms underlying this association remain unclear, as exploring them was beyond the scope of this study. Future research should investigate these processes in greater depth to uncover the pathways through which family support impacts life satisfaction.

Interestingly, family support for living did not show a statistically significant association with life satisfaction, a finding that diverges from expectations. This result suggests that older adults may perceive family support for living differently from support for daily activities. Support for living, such as financial assistance or housing, may not carry the same emotional weight as assistance with daily tasks, which can challenge an individual’s sense of independence. This distinction underscores the importance of examining the context and nature of family support in influencing well-being.

Gender did not significantly moderate the association between family support for daily activities and life satisfaction among older adults, but it played a notable role in the relationship between family support for living and life satisfaction. Specifically, older men who relied on family support for living reported lower life satisfaction than older women in similar circumstances. This finding highlights how societal gender norms influence perceptions of family support. In societies with strong patriarchal norms, such as Nepal, men are traditionally viewed as providers and symbols of self-reliance (Bishwakarma, 2020). When men rely on family support for living—whether due to retirement, job loss, or unemployment—they may experience internal conflict with societal expectations and personal beliefs about their role within the family. This disconnect can result in feelings of inadequacy, frustration, loss of independence, and ultimately lower life satisfaction (Thomas, 2010). Conversely, women in these settings are often expected to manage household responsibilities rather than engage in financial or external work (Bishwakarma, 2020). As a result, reliance on family support for living may align with their traditional roles, leading to a more positive perception of such support. This internalized acceptance of dependency may amplify the positive impact of family support on women’s life satisfaction in later life.

These findings illustrate the paradoxical nature of family support in later life, particularly the differing perceptions between men and women. While family support is critical for many older adults, it can also challenge their autonomy and redefine their role within the family. This tension is particularly evident in discussions surrounding filial piety, where the expectation of care from children can create a delicate balance between the need for support and the desire for independence (Ang & Malhotra, 2022; Thomas, 2010). The results of this study emphasize the need to consider gender dynamics when exploring the relationship between family support and life satisfaction among older adults.

A brief discussion of the control variables is also warranted, as this study highlighted several factors influencing life satisfaction among older adults, including ethnicity, family size, sense of being valued, and chronic morbidity. Specifically, Aadiwashi/Janajati and Brahmin/Chettri/Thakuri ethnic groups reported higher life satisfaction compared to Dalit participants. Conversely, larger family size, chronic morbidity, and a lack of feeling valued were all associated with lower odds of life satisfaction. Members of Dalit ethnic groups, historically marginalized and socially excluded in Nepal (Atreya et al., 2022), may experience lower life satisfaction due to systemic inequities and caste-based discrimination, which limit their access to resources and opportunities. An intriguing finding of this study was that each additional family member reduced the odds of experiencing life satisfaction by 16%. This diverges from previous research, which typically highlights family support, in terms of large family size, as a positive contributor to life satisfaction in later life (Oliveira et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020). A possible explanation lies in the quality of relationships within the family. While larger families may offer more potential sources of support, they can also introduce greater interpersonal conflicts, stressors, and responsibilities. According to the social stress process theory, such stressors may outweigh the benefits of social support and negatively impact well-being (Pearlin & Bierman, 2013). Moreover, the rural context of this study provides additional insights. In resource-constrained settings, larger families may stretch available resources thin, leading to reduced individual attention and support for older adults. This scarcity can foster feelings of neglect and devaluation, ultimately diminishing life satisfaction (Chokkanathan & Mohanty, 2017). Feeling consistently valued emerged as another important factor, as it can boost self-esteem, reduce stress, and foster stronger social connections, all of which contribute positively to life satisfaction (Rey-Beiro & Martínez-Roget, 2024). In contrast, chronic conditions and multimorbidity were associated with lower life satisfaction, likely due to the physical limitations, social isolation, and reduced work capacity that often accompany these conditions (Vancampfort et al., 2017). These health challenges can profoundly disrupt daily life and social relationships, further diminishing well-being.

5. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

One notable strength of this study was its large sample size, which, despite the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic, ensured a robust representation of older adults with diverse gender and age characteristics. Conducting interviews in the Nepali language likely enhanced communication between interviewers and participants, fostering a better understanding of responses. Additionally, pilot testing the interview questions strengthened the study’s methodological rigor by improving the validity and reliability of the data collection process.

However, certain limitations should be noted. As a cross-sectional design, it cannot establish causal relationships between family support and life satisfaction, limiting the ability to determine how family dynamics influence well-being over time. Furthermore, the study utilized only two single items to measure family support, which may not comprehensively capture its complexity. The research was limited to rural settings, leaving unanswered questions about how family dynamics and life satisfaction might differ in urban environments. Additionally, the study did not account for the dependence on adult children or family members who had migrated temporarily for work, a significant factor given Nepal’s prevalent migration patterns among youth (Adhikari et al., 2023). Data collection during the COVID-19 pandemic presents another potential limitation. Lockdown measures may have restricted mobility, particularly for older adults, potentially inflating responses regarding reliance on family for daily activities and living (Felipe et al., 2023).

6. Study Implications and Future Research

The study underscores the intricate nature of family support for older adults in rural Nepal, highlighting the importance of strategies that prioritize the independence and well-being of older family members. Policy frameworks must not only endorse and reinforce the significance of familial care, particularly for older adults who need support for their daily activities but also underscore the importance of preserving individual autonomy within familial support structures (Alonso et al., 2022; Chokkanathan & Mohanty, 2017; Heide, 2022). Encouraging intergenerational communication and understanding within families can foster an environment conducive to mutual respect and support. Moreover, implementing culturally sensitive educational programs aimed at both older adults and their families becomes imperative. These programs could emphasize the evolving needs and preferences of the older population in rural settings while empowering families with the tools to offer assistance without undermining the older individual's independence. Additionally, initiatives that highlight the value of active participation and decision-making by older adults in familial affairs could strengthen their sense of agency and strengthen familial relationships.

Interestingly, this study reveals that men who rely on family for living are less likely to experience life satisfaction, whereas this reliance appears to have the opposite effect on women. To gain a deeper understanding of this relationship over time, longitudinal studies could provide valuable insights into the evolving dynamics of gender, family support, and life satisfaction among older individuals. One avenue for exploration could involve examining how shifts in societal norms, economic conditions, and caregiving responsibilities influence the experiences of older women. For example, changes in women's workforce participation, access to education and healthcare, and evolving family structures may impact their perceptions of family support and life satisfaction. In addition to longitudinal research, qualitative studies could provide deeper insights into the lived experiences of older adults. By capturing individual narratives, qualitative methods can help uncover the emotional, cultural, and contextual factors that influence how family support is perceived and its impact on life satisfaction.

Furthermore, this study also underscores the necessity of investigating the stressors experienced by caregivers and providers within families responsible for the care of older family members, especially given the absence of caregiver incentives, support policies, and programs in Nepal (Singh et al., 2021). Future studies could explicitly investigate which forms of family support (e.g., financial, emotional assistance, healthcare support, transportation, etc.) are of major significance for older adults, focusing interventions on areas of family support that are most needed and impactful to improve their well-being. Furthermore, future research could delve deeper into the underlying mechanisms that elucidate the paradoxical nature of family support concerning the life satisfaction of older adults. This is particularly relevant within the cultural context of filial piety, where the expectation of care can both strengthen family bonds and introduce stressors that impact the life satisfaction of older adults.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K.; methodology, I.K., S.G.; formal analysis, I.K., S.G.; investigation, S.K.M., O.P.Y., S.P., S.M., U.N.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K.; writing—review and editing, I.K., S.G., L.T., S.K.M., S.M., U.N.Y.; supervision, S.G., validation, S.K.M., O.P.Y., S.P., S.M., U.N.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. However, the original study that collected the data was funded by the Nepal Health Research Council.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethical Review Board of Nepal Health Research Council (Ref#114/2021P) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all respondents involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the respondents. Participation was voluntary and their responses remained confidential.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy and confidentiality concerns. The data may contain sensitive information about individuals' demographics, and experiences, physical and mental health status, which must be protected to ensure the privacy and dignity of the participants. However, the de-identified datasets are available on reasonable request with ethical approval.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Adhikari, J., Rai, M. K., Baral, C., & Subedi, M. (2023). Labour Migration from Nepal: Trends and Explanations. In S. I. Rajan (Ed.), Migration in South Asia: IMISCOE Regional Reader (pp. 67–81). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Aina, F. O., Fakuade, B. O., Agbesanwa, T. A., Dada, M. U., & Fadare, J. O. (2023). Association between support and satisfaction with life among older adults in Ekiti, Nigeria: Findings and implications. Open Journal of Medical Psychology, 12(3), Article 3. [CrossRef]

- Alonso, M. A. M., Barajas, M. E. S., Ordóñez, J. A. G., Ávila Alpirez, H., Fhon, J. R. S., & Duran-Badillo, T. (2022). Quality of life related to functional dependence, family functioning and social support in older adults. Revista Da Escola de Enfermagem Da USP, 56, e20210482. [CrossRef]

- Ang, S., & Malhotra, R. (2022). The filial piety paradox: Receiving social support from children can be negatively associated with quality of life. Social Science & Medicine, 303, 114996. [CrossRef]

- Atreya, K., Rimal, N. S., Makai, P., Baidya, M., Karki, J., Pohl, G., & Bhattarai, S. (2022). Dalit’s livelihoods in Nepal: Income sources and determinants. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Bishwakarma, G. (2020). The role of Nepalese proverbs in perpetuating gendered cultural values. Advances in Applied Sociology, 10(04), 103–114. [CrossRef]

- CBS. (2021). Preliminary report of national population census 2021. National Statistics Office, Government of Nepal. Available from: https://censusnepal.cbs.gov.np/Home/Details?tpid=1.

- Chalise, H. N., Kai, I., & Saito, T. (2010). Social support and its correlation with loneliness: A cross-cultural study of Nepalese older adults. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 71(2), 115–138. [CrossRef]

- Chokkanathan, S., & Mohanty, J. (2017). Health, family strains, dependency, and life satisfaction of older adults. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 71, 129–135. [CrossRef]

- Devkota, S., Ghimire, S., & Upadhyay, M. (2021). What Factors in Nepal Account for the Rural–Urban Discrepancy in Human Capital? Evidence from Household Survey Data. Economies, 9(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. [CrossRef]

- Felipe, S. G. B., Parreira Batista, P., da Silva, C. C. R., de Melo, R. C., de Assumpção, D., & Perracini, M. R. (2023). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mobility of older adults: A scoping review. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 18(1), e12496. [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, S., Baral, B. K., Karmacharya, I., Callahan, K., & Mishra, S. R. (2018). Life satisfaction among elderly patients in Nepal: Associations with nutritional and mental well-being. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16, 118. [CrossRef]

- Heide, S. K. (2022). Autonomy, identity and health: Defining quality of life in older age. Journal of Medical Ethics, 48(5), 353–356. [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.-J., Imtiaz, F., Su, Y., Zhang, Z., Bowie, A. C., & Chang, B. (2022). Culture, Aging, Self-Continuity, and Life Satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(8), 3843. [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R., Jones, K., & Manley, D. (2018). Confounding and collinearity in regression analysis: A cautionary tale and an alternative procedure, illustrated by studies of British voting behaviour. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1957–1976. [CrossRef]

- Karmacharya, R., & Thapa, N. (2022). Satisfaction with life among senior citizens in Pokhara metropolitan city: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Gandaki Medical College-Nepal, 15(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. S., Delaney, S. W., Tay, L., Chen, Y., Diener, E., & Vanderweele, T. J. (2021). Life satisfaction and subsequent physical, behavioral, and psychosocial health in older adults. The Milbank Quarterly, 99(1), 209–239. [CrossRef]

- KoboToolbox. (2020). Powerful and intuitive data collection tools to make an impact [Computer software]. Available from: https://www.kobotoolbox.org/.

- Kumari, R., & Kumar, D. (2023). Subjective wellbeing as function of age and gender of elderly people. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 11(2). [CrossRef]

- Kwiecien, R., Kopp-Schneider, A., & Blettner, M. (2011). Concordance analysis. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 108(30), 515–521. [CrossRef]

- LaVela, S. L., Etingen, B., Miskevics, S., & Heinemann, A. W. (2019). What determines low satisfaction with life in individuals with spinal cord injury? The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine, 42(2), 236–244. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., & Singh, G. K. (2020). Inequalities in Life Expectancy and All-Cause Mortality in the United States by Levels of Happiness and Life Satisfaction: A Longitudinal Study. International Journal of Maternal and Child Health and AIDS, 9(3), 305. [CrossRef]

- MK, S., Adhikari, R., Ranjitkar, U., & Chand, A. (2019). Life satisfaction among senior citizens in a community of Kathmandu, Nepal. Journal of Gerontology & Geriatric Research, 8(2), 5. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M. C. G. M. de, Salmazo-Silva, H., Gomes, L., Moraes, C. F., & Alves, V. P. (2019). Elderly individuals in multigenerational households: Family composition, satisfaction with life and social involvement. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas), 37, e180081. [CrossRef]

- Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2009). Review of the satisfaction with life scale. In E. Diener (Ed.), Assessing Well-Being: The Collected Works of Ed Diener (pp. 101–117). Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Pearlin, L. I., & Bierman, A. (2013). Current Issues and Future Directions in Research into the Stress Process. In C. S. Aneshensel, J. C. Phelan, & A. Bierman (Eds.), Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health (pp. 325–340). Springer Netherlands. [CrossRef]

- Poon, L. W., & Cohen-Mansfield, J. (2011). Understanding well-being in the oldest old. Cambridge University Press. www.cambridge.org/9780521132008.

- Rey-Beiro, S., & Martínez-Roget, F. (2024). Rural-urban differences in older adults’ life satisfaction and its determining factors. Heliyon, 10(9), e30842. [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, K. P., Shrestha, A., Ghimire, S., Mistry, S. K., Yadav, K. K., Yadav, S. C., Mehta, R. K., Quasim, R., Tamang, M. K., Singh, D. R., Yadav, O. P., Mehata, S., & Yadav, U. N. (2024). Neighborhood environment and quality of life of older adults in eastern Nepal: Findings from a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 24(1), 679. [CrossRef]

- SAS Institute Inc. (2013). Statistical Analysis Systems (SAS)/ACCESS® 9.4 Interface to ADABAS. [Computer software]. Available from: https://www.sas.com.

- Schwartz, S. J., Weisskirch, R. S., Hurley, E. A., Zamboanga, B. L., Park, I. J. K., Kim, S. Y., Umaña-Taylor, A., Castillo, L. G., Brown, E., & Greene, A. D. (2010). Communalism, Familism, and Filial Piety: Are They Birds of a Collectivist Feather? Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16(4), 548. [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A., Ghimire, S., Kinney, J., Mehta, R., Mistry, S. K., Saito, S., Rayamajhee, B., Sharma, D., Mehta, S., & Yadav, U. N. (2024). The role of family support in the self-rated health of older adults in eastern Nepal: Findings from a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 24, 20. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S. N., Upadhyay, A., & Chalise, H. N. (2021). Living arrangement of older people: A study of community living elderly from Nepal. Advances in Aging Research, 10(6), Article 6. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P. A. (2010). Is it better to give or to receive? Social support and the well-being of older adults. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 65B(3), 351–357. [CrossRef]

- Vancampfort, D., Stubbs, B., & Koyanagi, A. (2017). Physical chronic conditions, multimorbidity and sedentary behavior amongst middle-aged and older adults in six low- and middle-income countries. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 147. [CrossRef]

- Veenhoven, R. (1996). The study of life satisfaction. In A comparative study of satisfaction with life in Europe (pp. 11–48). Eötvös University Press. Available from: hdl.handle.net/1765/16311.

- Wang, L., Yang, L., Di, X., & Dai, X. (2020). Family Support, Multidimensional Health, and Living Satisfaction among the Elderly: A Case from Shaanxi Province, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), Article 22. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, U. N., Tamang, M. K., Thapa, T. B., Hosseinzadeh, H., Harris, M. F., & Yadav, K. K. (2019). Prevalence and determinants of frailty in the absence of disability among older population: A cross sectional study from rural communities in Nepal. BMC Geriatrics, 19(1), 283. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).