Submitted:

04 December 2024

Posted:

05 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

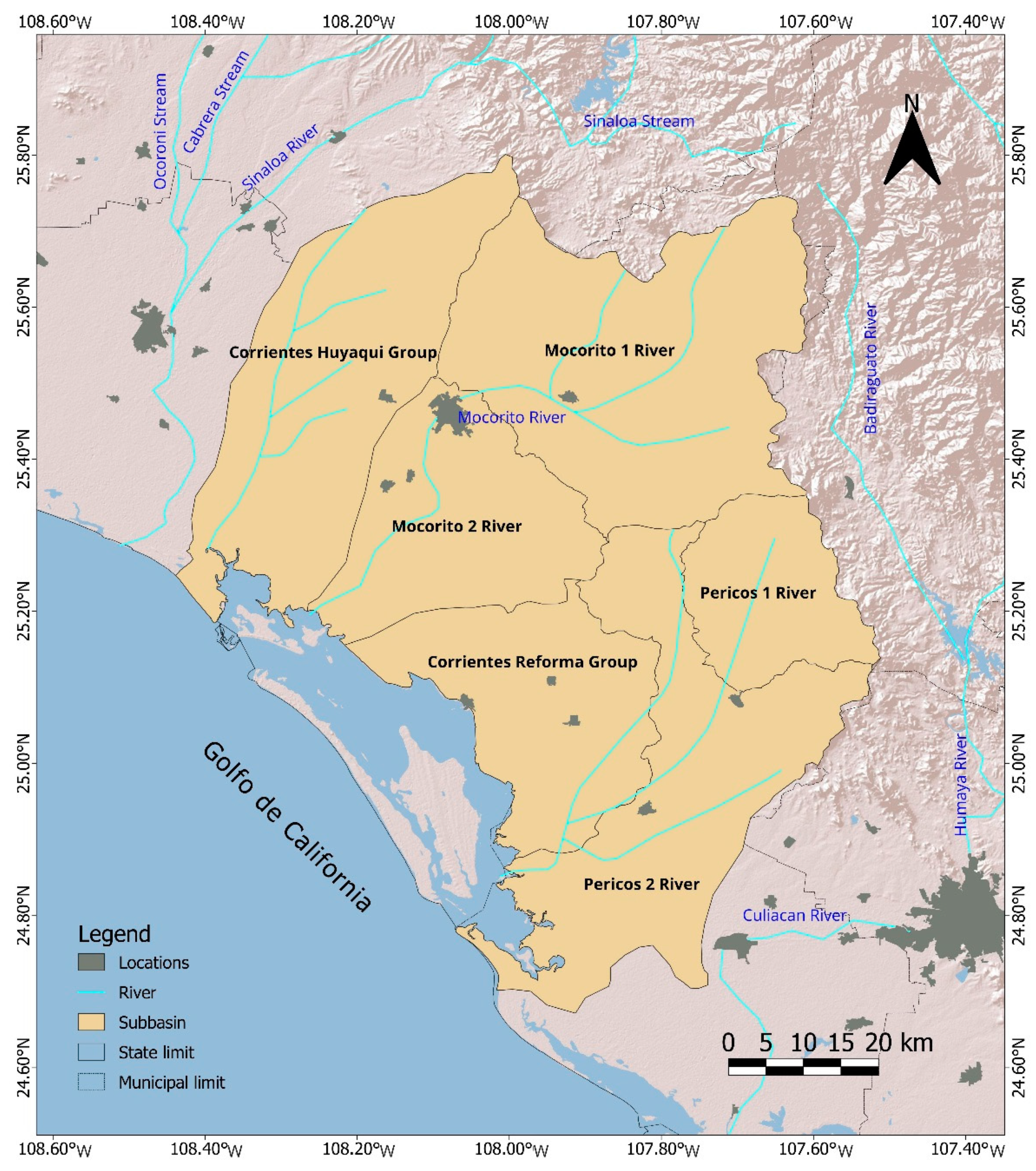

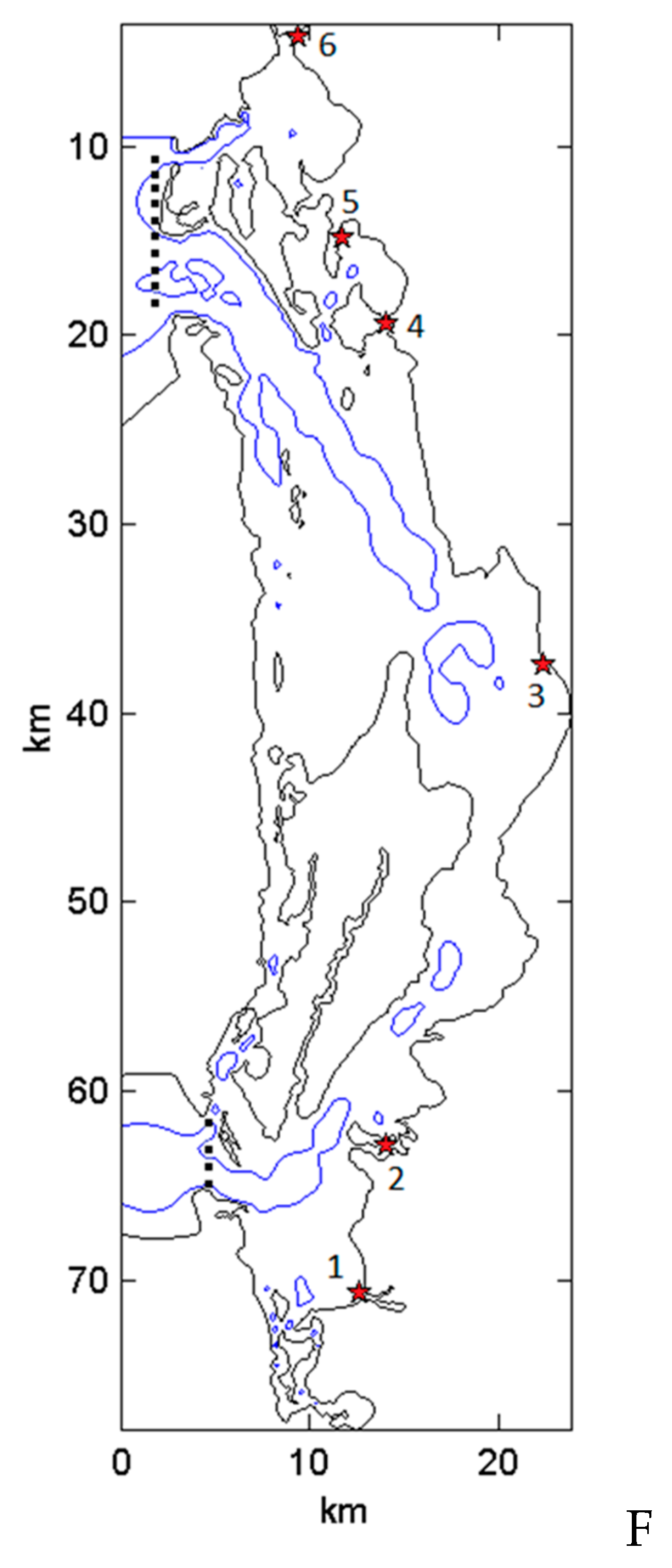

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Sampling Strategy

2.3. Carrying Capacity

2.3.1. Historical Evaluation

2.3.2. Present Day Evaluation

2.4. Sub-Basin Economic Activities

| Sub-basin | Municipality | Contribution of sub-basins on land cover (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Corrientes Huyaqui Group | Guasave | 17.20 |

| Sinaloa | 5.29 | |

| Salvador Alvarado | 36.81 | |

| Angostura | 23.00 | |

| Mocorito 1 River | Sinaloa municipio | 1.37 |

| Salvador Alvarado | 12.92 | |

| Mocorito | 47.77 | |

| Badiraguato | 2.01 | |

| Mocorito 2 River | Angostura | 40.73 |

| Mocorito | 1.60 | |

| Salvador Alvarado | 44.21 | |

| Corrientes Reforma Group | Angostura | 36.27 |

| Salvador Alvarado | 4.34 | |

| Mocorito | 8.31 | |

| Navolato | 9.03 | |

| Pericos 1 River | Badiraguato | 4.32 |

| Mocorito | 10.55 | |

| Pericos 2 River | Mocorito | 23.5 |

| Salvador Alvarado | 1.73 | |

| Navolato | 30.69 | |

| Badiraguato | 0.11 |

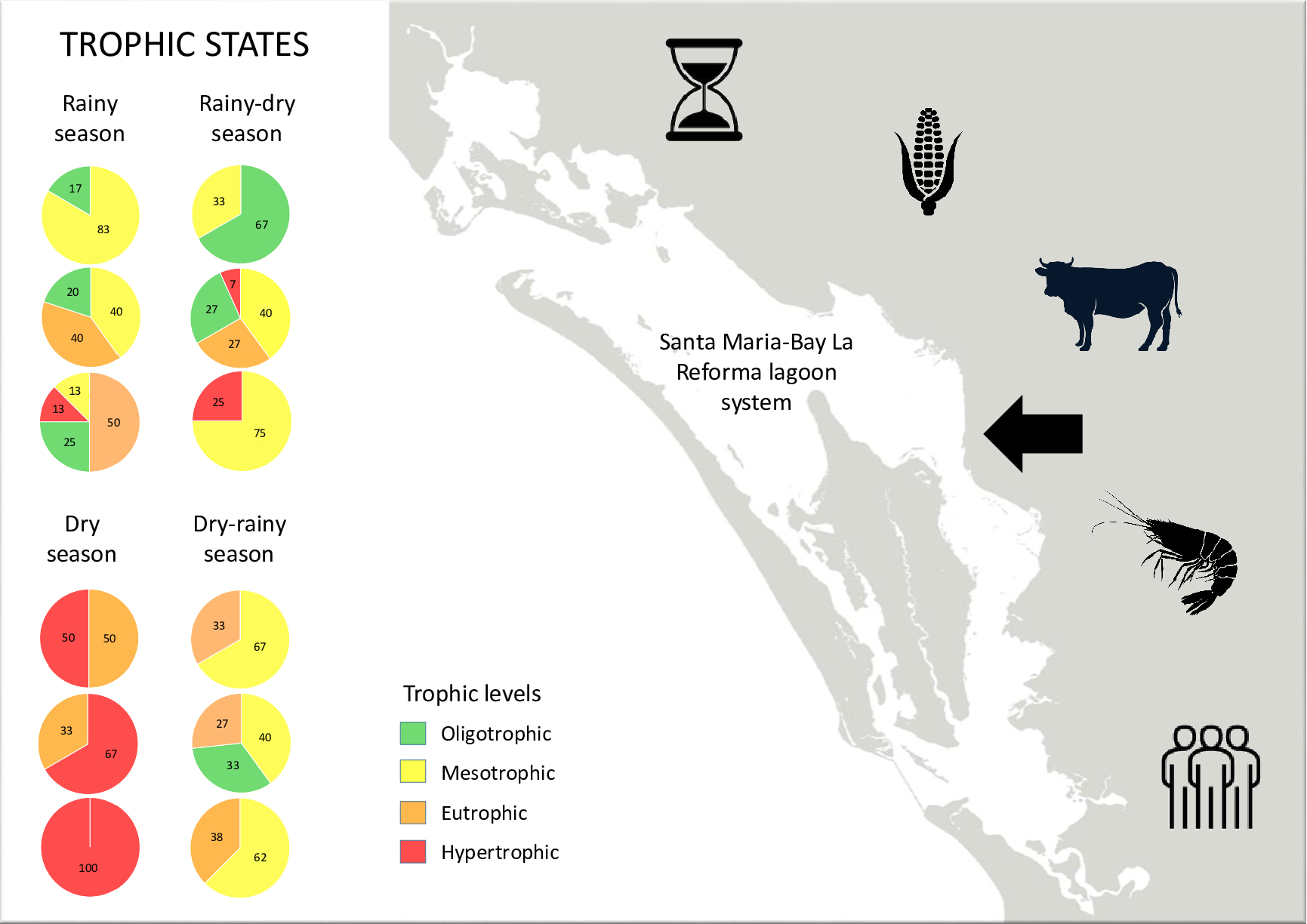

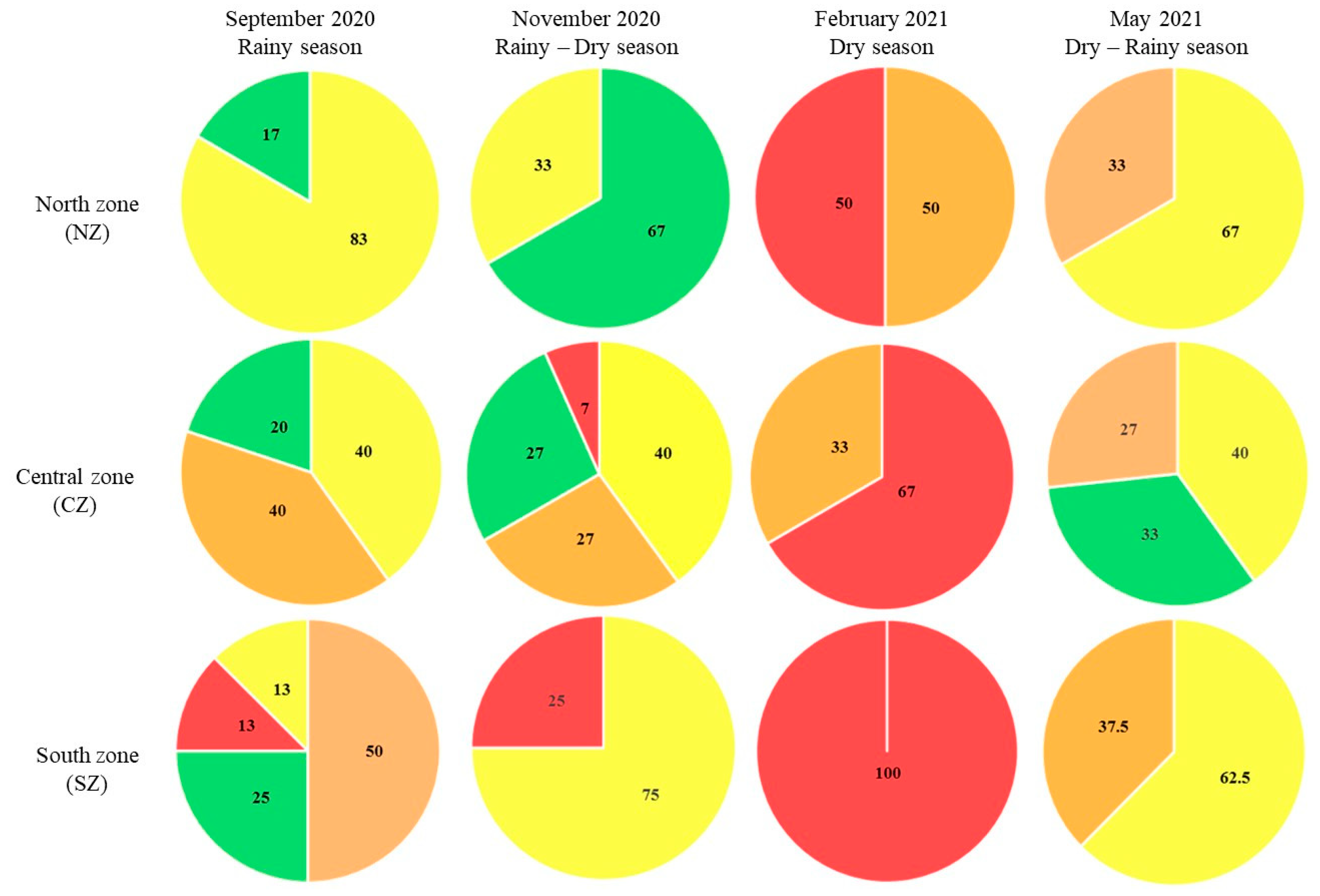

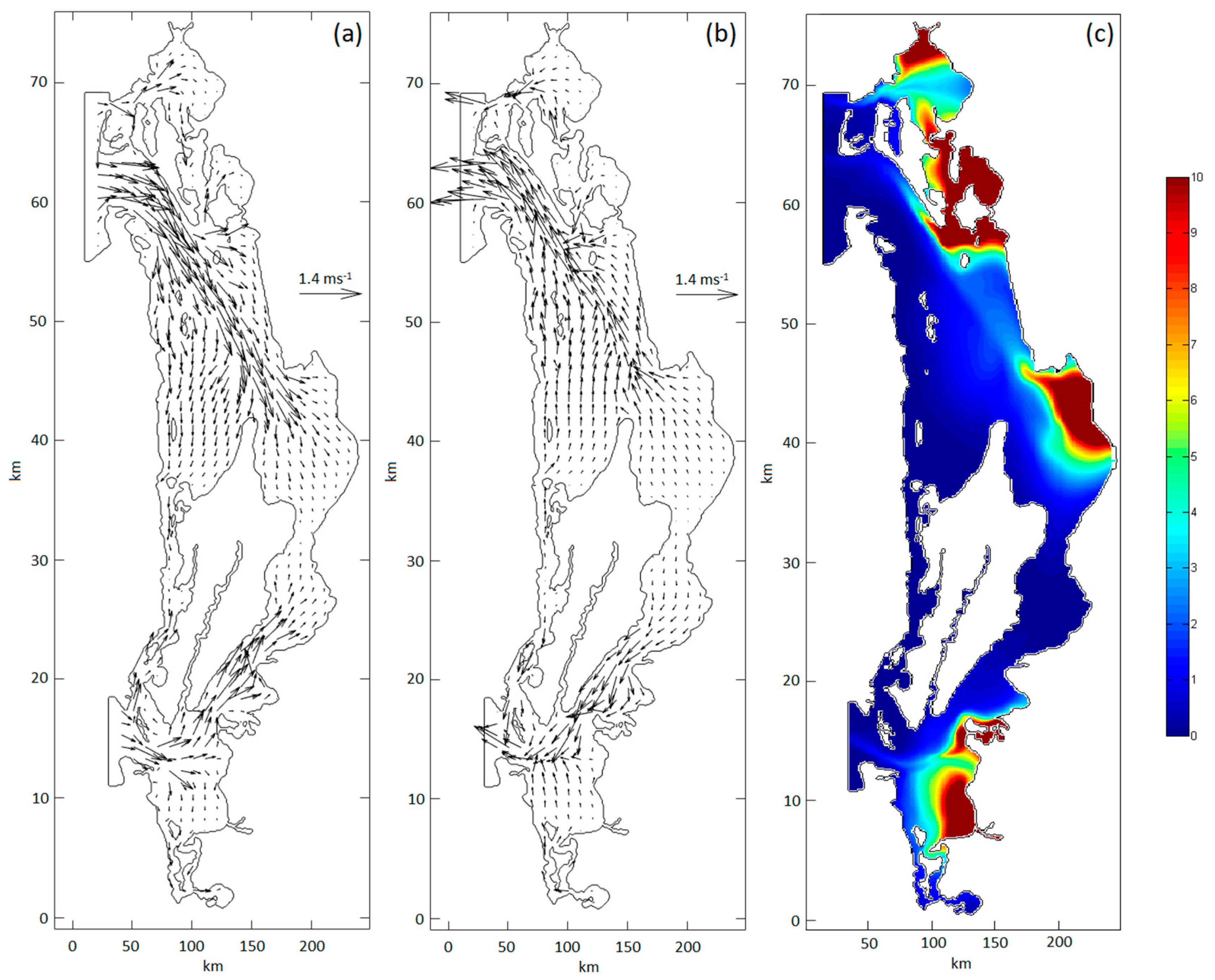

2.5. Loading Nutrients, Trophic State, and Residence Time: Hydrodynamic Model Evaluation

2.6. Integrative Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Carrying Capacity

3.1.1. Historical Evaluation

| Season | Residence time Rt day-1 |

ΔDIN mmol m-2 day-1 |

ΔDIP mmol m-2 day-1 |

NEM (p-r) mmol C m-2 day-1 |

N2fix-HD mmol m-2 day-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1Rainy | 1.6 | 16.82 | 2.05 | -217.92 | -16.07 |

| 2Rainy | 53 | 14.36 | 1.76 | -186.08 | -13.72 |

| 2Dry | 22.5 | 36.91 | 2.63 | -278.44 | -5.11 |

| 3Rainy | 1.2 | -0.02 | 0.03 | -3.70 | -0.45 |

| 3Dry | 3.2 | -0.03 | 0.02 | 2.46 | 0.40 |

| 4Rainy | 0.6 | -120.94 | -5.57 | 590.5 | -31.81 |

| 4Rainy-dry | 0.4 | 1.94 | 0.14 | -1684.6 | -252.34 |

| 4Dry | 0.2 | 45.55 | -2.03 | 215.7 | 78.11 |

| 4Dry-rainy | 20 | -21.43 | -2.72 | 289.17 | 22.21 |

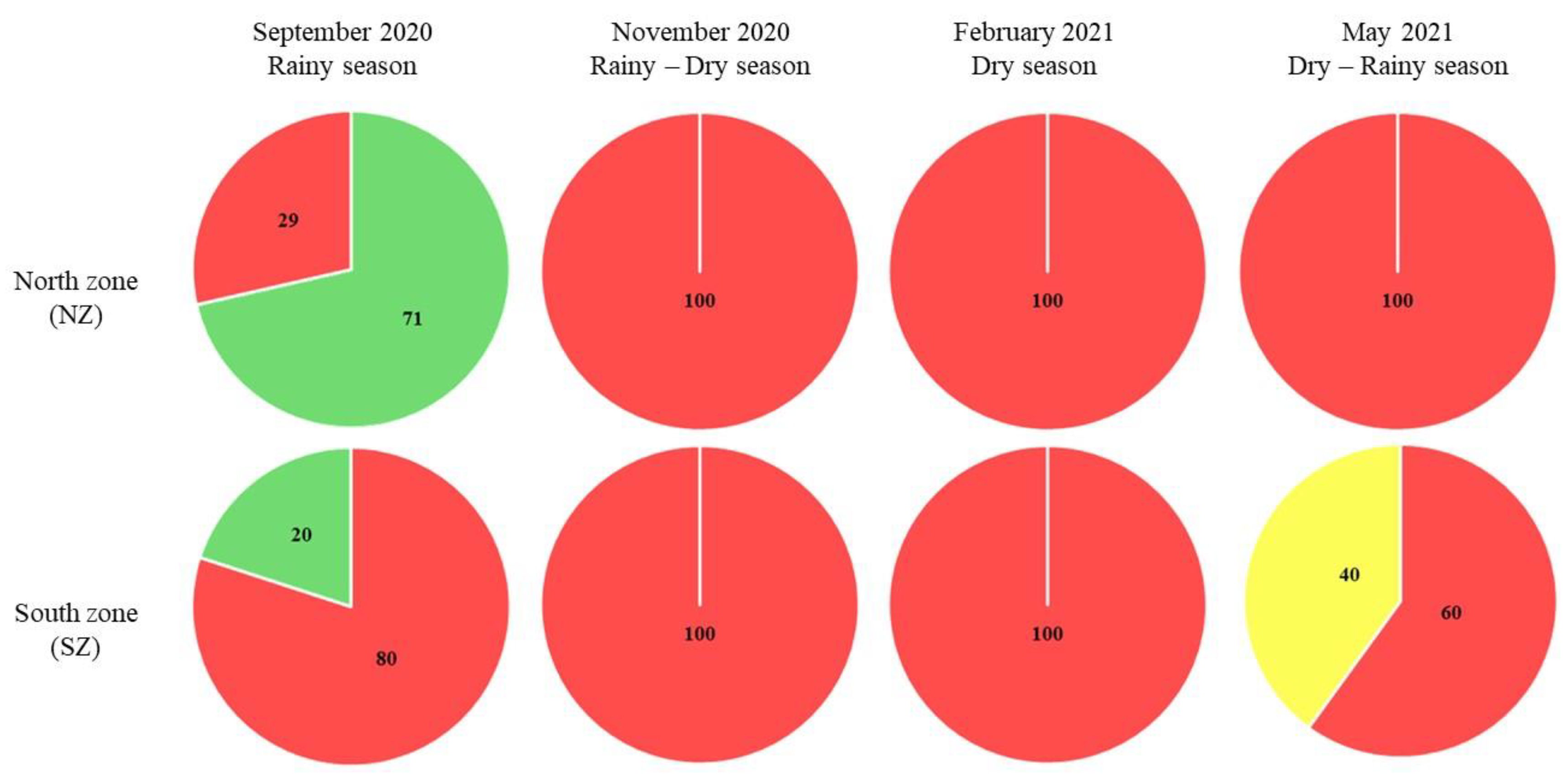

3.1.2. Present Day Evaluation

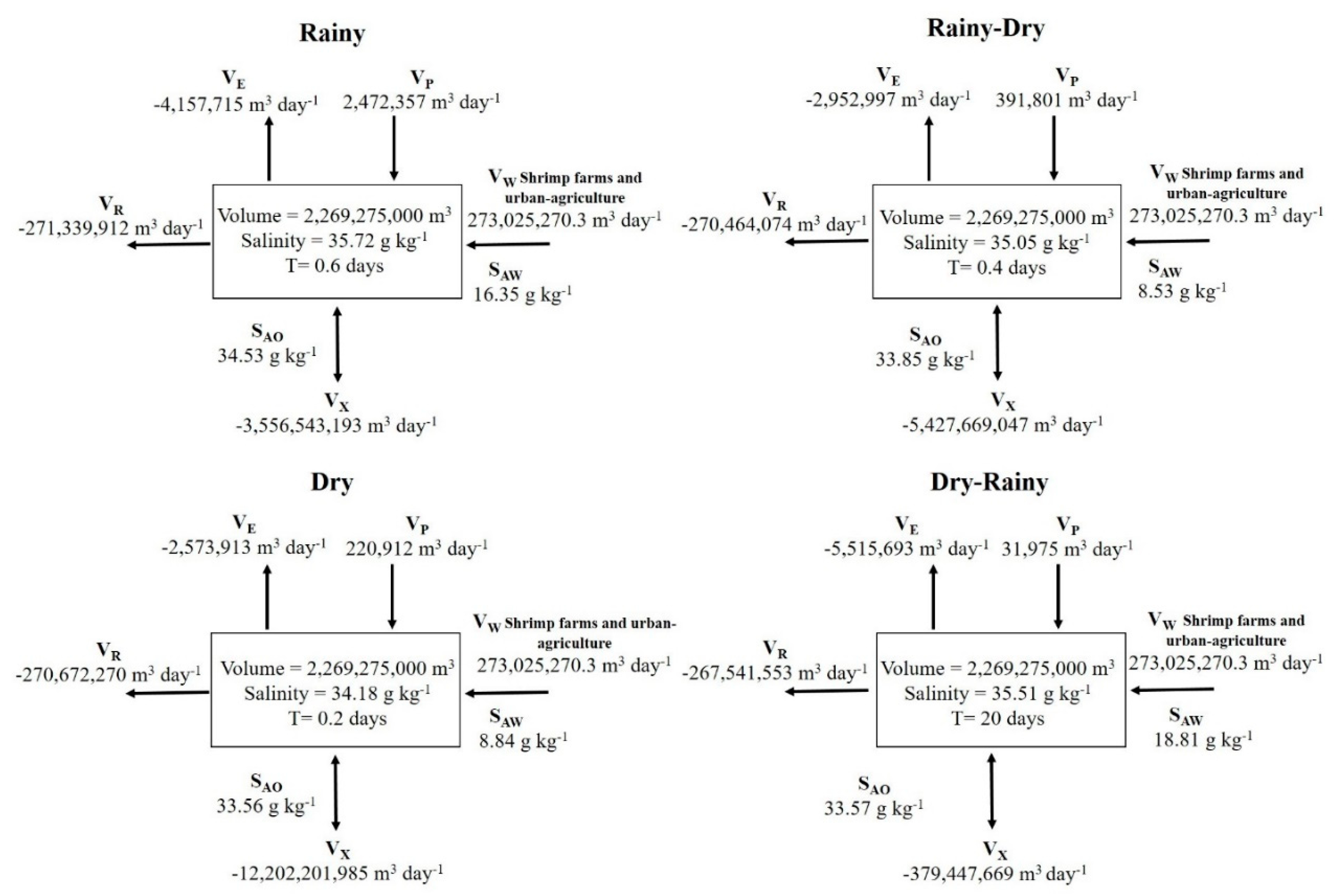

Water Residence Time Rt

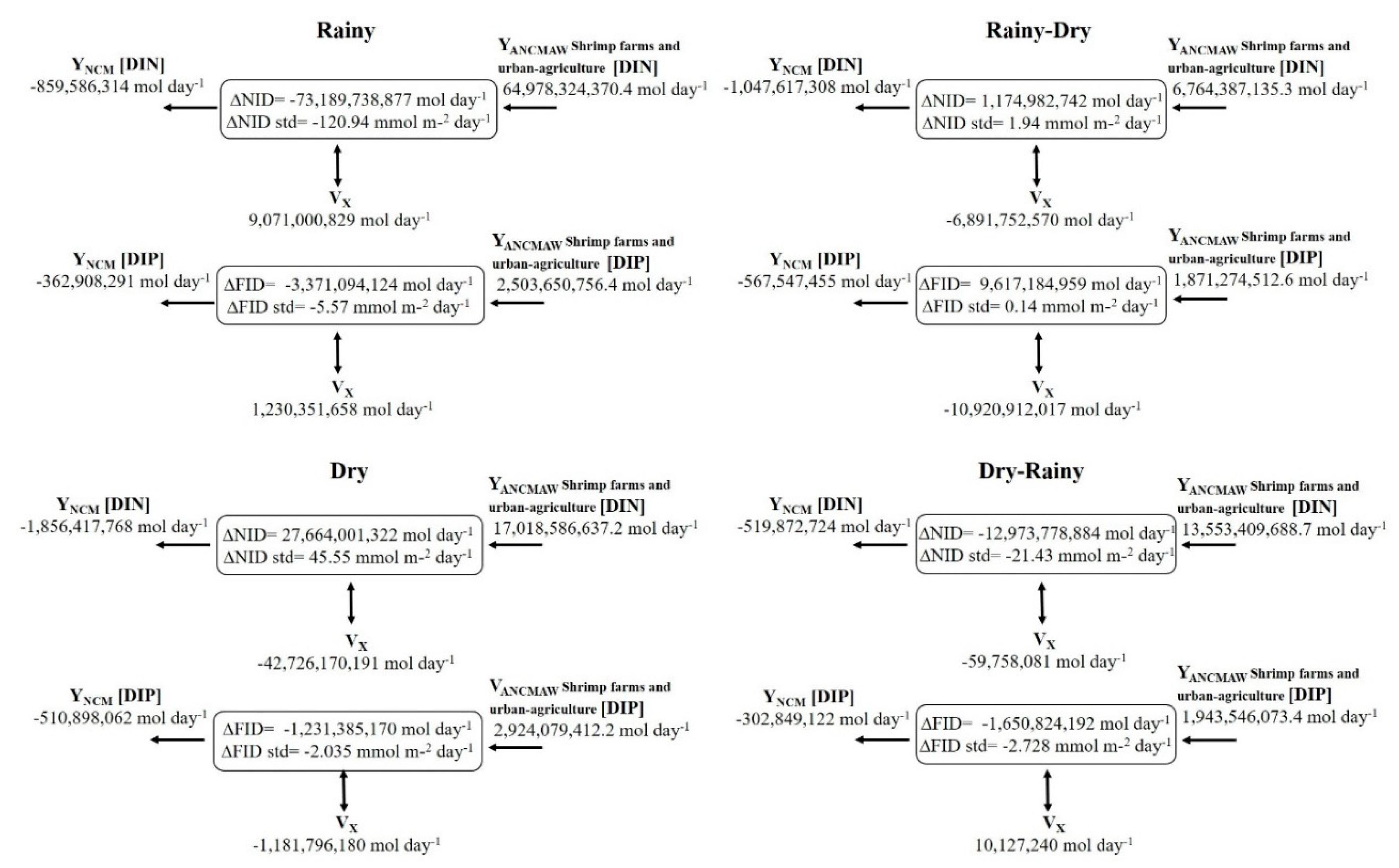

Nutrients Fluxes

Net ecosystem Metabolism (NEM)

| Season | Rainy | Rainy-Dry | Dry | Dry-Rainy |

| NEM (mmol C m-2 day-1) | +590.50 | -1684.60 | +215.70 | +289.17 |

| N2fix-HD (mmol m-2 day-1) | +31.81 | -252.34 | +78.11 | +22.21 |

| Condition | Aut-N2fix | Het-HD | Aut-N2fix | Aut-N2fix |

Residence Time:

| IP number | September 2020 Rainy |

November 2020 Rainy - Dry |

February 2021 Dry |

May 2021 Dry - Rainy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP | Rt (h) | Rt (h) | Rt (h) | Rt (h) |

| 1 | 40.02 | 33.01 | 34.21 | 28.67 |

| 2 | 39.94 | 32.58 | 33.97 | 28.33 |

| 3 | 102.57 | 57.75 | 84.33 | 53.55 |

| 4 | 39.82 | 32.86 | 34.06 | 28.65 |

| 5 | 38.79 | 32.64 | 33.33 | 28.29 |

| 6 | 38.62 | 31.73 | 32.77 | 27.72 |

Modeling the Concentration of the Pollutant in the Mouths:

| IP number | September 2020 Rainy |

November 2020 Rainy - Dry |

February 2021 Dry |

May 2021 Dry - Rainy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP | MTC | MTC | MTC | MTC |

| 1 | 9.39 × 10-5 | 0.0027 | 0.0012 | 0.0030 |

| 2 | 0.0040 | 0.0248 | 0.0160 | 0.0363 |

| 3 | 2.35 × 10-6 | 2.76 × 10-6 | 4.05 × 10-7 | 4.0 × 10-5 |

| 4 | 0.0024 | 0.0128 | 0.0041 | 0.0132 |

| 5 | 0.0039 | 0.0146 | 0.0121 | 0.0144 |

| 6 | 0.0030 | 0.0210 | 0.0057 | 0.0243 |

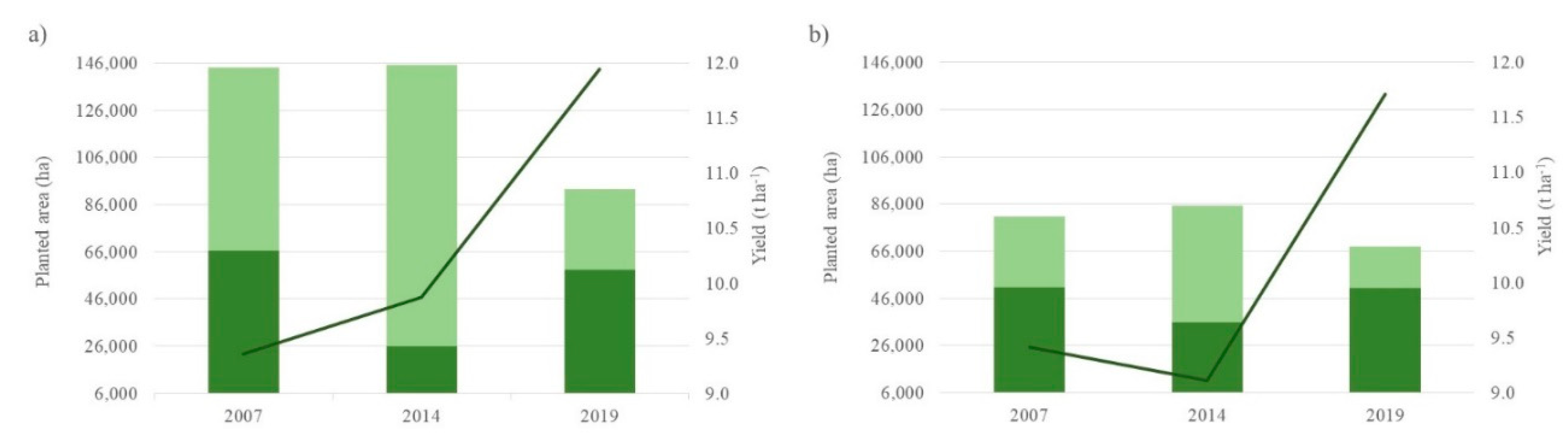

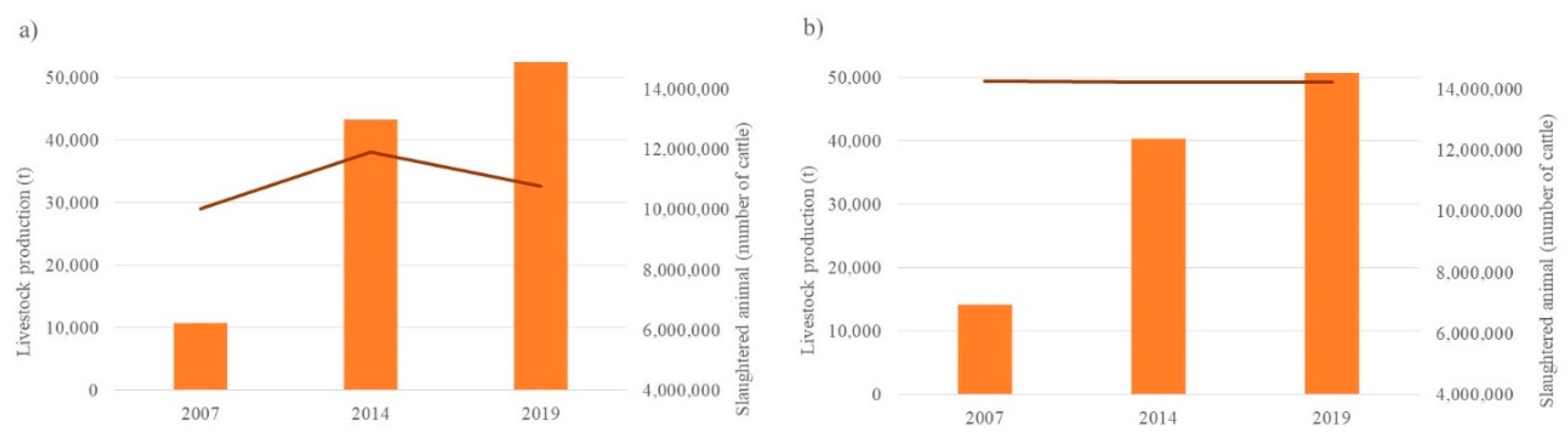

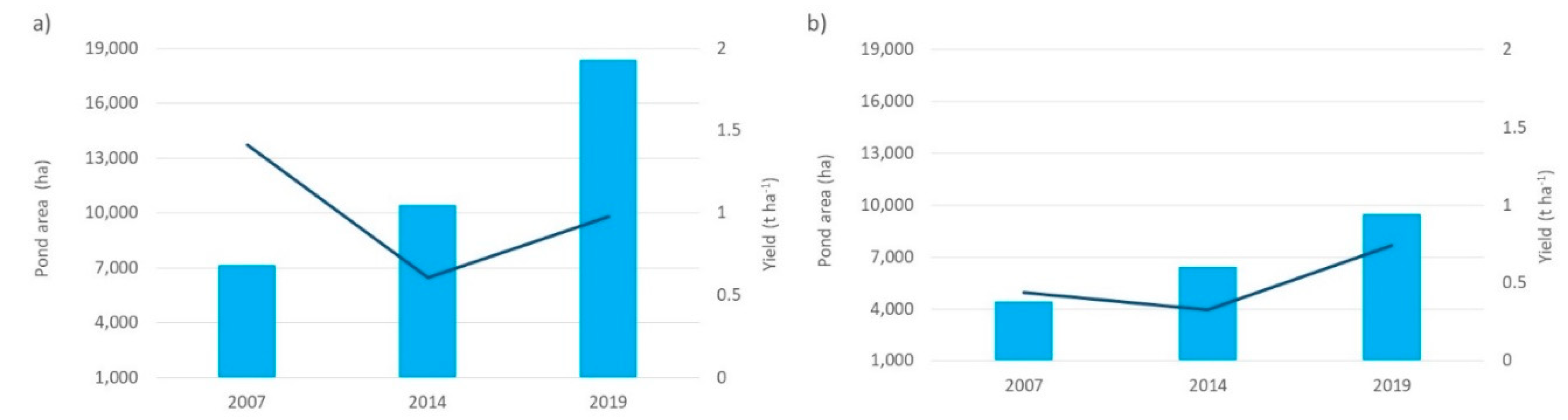

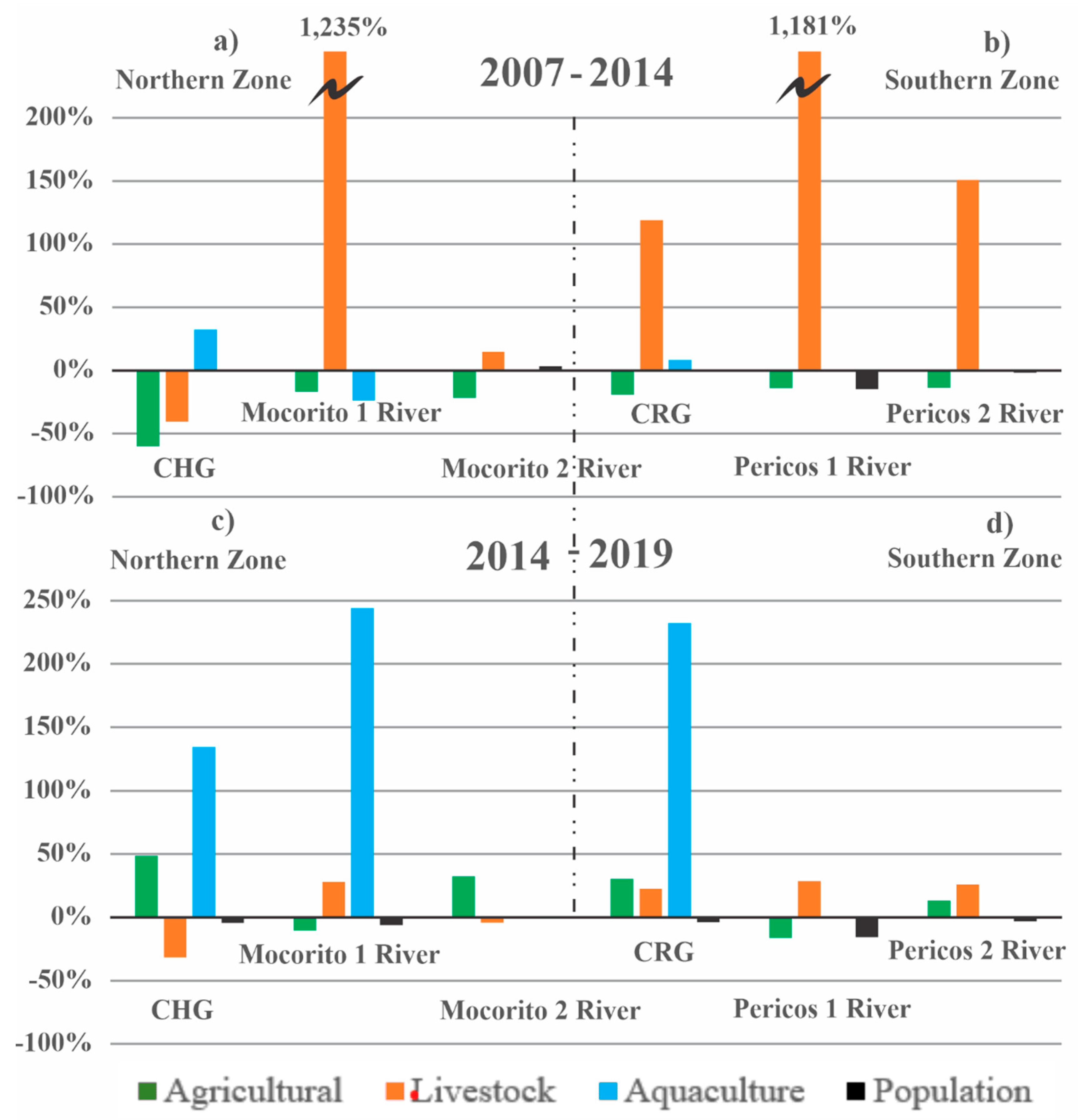

3.2. Sub-Basin Economic Activities

Agricultural production:

Aquaculture Production

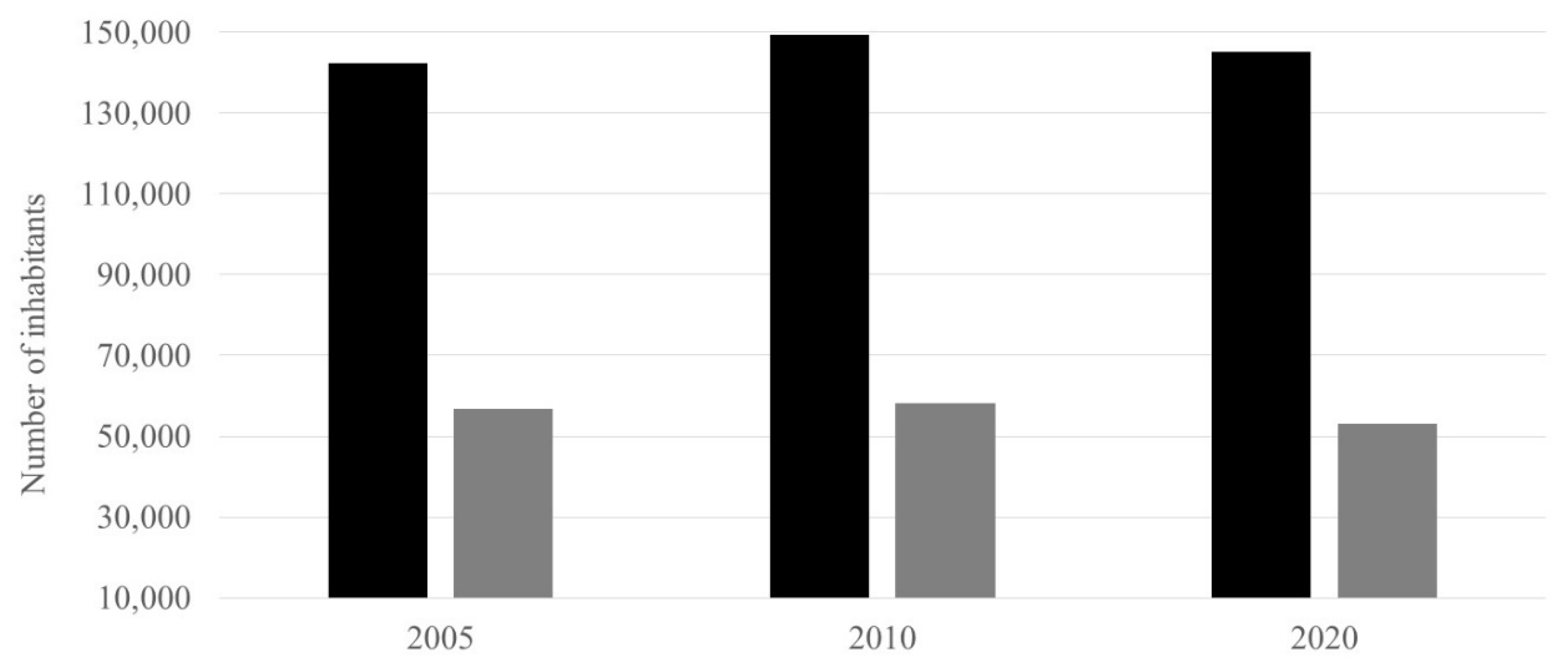

Population:

Basin Assessment

Loading nutrients, trophic state and residence time: hydrodynamic model

4. Discussion

4.1. Carrying Capacity

4.1.1. Historical Evaluation

4.1.2. Present Day Evaluation

4.2. Integrative Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acosta-Velázquez, J. & Vázquez-Lule, A. D. (2009). Caracterización del sitio de manglar Santa María - La Reforma, en Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO). Sitios de manglar con relevancia biológica y con necesidades de rehabilitación ecológica. CONABIO, México, D.F., 18 pp.

- Anthony, A., Atwood, J., August, P., Byron, C., Cobb, S., Foster, C., Fry, C., Gold, A., Hagos, K., Heffner, L., Kellogg, D. Q., Lellis-Dibble, K., Opaluch, J. J., Oviatt, C., Pfeiffer-Herbert, A., Rohr, N., Smith, L., Smythe, T., Swift, J., & Vinhateiro, N. (2009). Coastal lagoons and climate change: ecological and social ramifications in U.S. Atlantic and Gulf coast ecosystems. Ecology and Society 14(1), 8. [online] URL: http: //www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss1/art8/.

- Aouissi, J., Benabdallah, S., Lili, C. Z., & Cudennec, C. (2014). Modelling water quality to improve agricultural practices and land management in a Tunisian catchment using soil and water assessment tool. Journal of Environmental Quality 43, 18–25.

- Béjaoui, B., Basti, L., Canu, D.M., Feki-Sahnoun, W., Salem, H., Dahmani, S., Sahbani, S., Benabdallah, S., Blake, R., Norouzi, H., & Solidoro, C. (2022). Hydrology, biogeochemistry and metabolism in a semi-arid mediterranean coastal wetland ecosystem. Scientific. Reports, 12, p. 9367. [CrossRef]

- Brenes, C., Hernández, A., & Ballesteros, D. (2007). Flushing time in Perlas Lagoon and Bluefields Bay, Nicaragua. Investigaciones Marinas 35(1), 89-96.

- Bui, L. T., & Tran, D.L.T. (2022). Assessing marine environmental carrying capacity in semi-enclosed coastal areas - Models and related databases. Science of The Total Environment 838 (Part 1), 156043. [CrossRef]

- Buzzelli, C., Wan, Y., Doering, P.H., & Boyer, J. N. (2013). Seasonal dissolved inorganic nitrogen and phosphorus budgets for two subtropical estuaries in South Florida, USA. Biogeosciences, 10, 6721–6736. [CrossRef]

- Cabral, A., & Fonseca, A. (2019). Coupled effects of anthropogenic nutrient sources and meteo-oceanographic events in the trophic state of a subtropical estuarine system. Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science 225, 106228. [CrossRef]

- Caffrey, J.M., Murrell, M.C., Wigan, C., McKinney, R. (2007). Effect of nutrient loading on biogeochemical and microbial processes in a New England salt marsh Biogeochemistry, 82, 251–264. [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Ibarra, V. F., & Rivera-Monroy, V. H. (2014). Coastal Lagoons and Estuaries in Mexico: Processes and Vulnerability. Estuaries and Coasts, 37, 1313-1318.

- Cerda, M., Barboza, C.D.N., Carvalho, C.N., Jandre, K.A., & Marques, A.N. (2013). Nutrient Budget sinthe Piratininga–Itaipu lagoon system (southeastern Brazil): effects of sea-exchange management. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research, 41(2), 226–238.

- Cervantes-Duarte, R. (2016). Nutrient fluxes and net metabolism in a coastal lagoon SW peninsula of Baja California, Mexico. Revista Bio Ciencias 4(2), 104-115.

- CESASIN. (2023). Reporte de producción: Ciclos de cultivo 2003-2019 proporcionado por CESASIN (Comité Estatal de Sanidad Acuícola de Sinaloa). Culiacán, Sinaloa. Archivos en Excel.

- Clarke, A.L. (2002). Assessing the Carrying Capacity of the Florida Keys. Population and Environment 23, 405–418.

- Cloern, J. E. (2001). Review our evolving conceptual model of the coastal eutrophication problem. Marine Ecology Progress Series 210, 223–253.

- CONABIO (2014). Red hidrográfica, subcuencas hidrográficas de México, escala 1:50000. Edición 2.0. En Red Hidrográfica. Instituto Nacional y Geografía. 2010. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. México. http://geoportal.conabio.gob.mx/metadatos/doc/html/redsub84gw.html. Accessed on August 28th, 2024.

- CONAPESCA (2024). Produce México más de 1 millón 900 mil toneladas de especies pesqueras y acuícolas en 2023. https://www.gob.mx/conapesca/es/articulos/registra-mexico-buena-produccion-pesquera-y-acuicola-en-el-2023?idiom=es#:~:text=Durante%20el%202023%2C%20M%C3%A9xico%20produjo,)%2C%20inform%C3%B3%20Octavio%20Almada%20Palafox. Accessed on October 16th, 2024.

- Crank, J. (1979). The mathematics of diffusion. Oxford Science Publications. Second edition. 414 pp.

- Del Río, S., M., Martínez-Durazo, A., & Jara-marini, M.E. (2016). The aquaculture and their impact in the coastal zone of the Gulf of California. Revista de Ciencias Biológicas y de la Salud, Universidad de Sonora, 18 (3), 37-46.

- Delhez, E.J.M., de Brye, B., de Brauwere, A., & Deleersnijder, E. (2014). Residence time vs influence time. Journal of Marine Systems 132, 185–195.

- Espejo, R. P., Ibarra, A. A., Hansen, A. M., Rodríguez, C. G., Márquez, L. C. G., González, M. B., Baca, A. S., & Durán, A.J. (2012). Agricultura y contaminación del agua. 1 Ed. 288 p., UNAM Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas, México, ISBN: 9786070235504.

- Esqueda, G. S. T., & Rivera, J. C. G. (2004). Saneamiento de las Aguas Costeras. In: E. R. Arriaga, G. J. V. Zapata, I. A. Adeath & F. R. May (eds.), El Manejo Costero en México, pp. 253-275, Universidad Autónoma de Campeche / SEMARNAT / CETYS Universidad / Universidad de Quintana Roo, Ensenada / Campeche, México, ISBN: 9685722129.

- FAO (2022). El estado mundial de la pesca y la acuicultura 2022. Hacia la transformación azul. Roma, FAO. [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de México (2022). Desplazamiento forzado interno en México: del reconocimiento a los desafíos. Gobierno de México, Secretaría de Gobernación, Subsecretaría de Derechos Humanos, población y migración. 192 p.

- González-Hernández, A.D., & López-Monroy, F. (2020). Modelaje de la interacción entre el humedal RAMSAR laguna de La Restinga (Isla de Margarita, Venezuela) y el Mar Caribe. Boletín del Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas 54 (2), 145-163.

- Gordon Jr., D. C., Boudreau, P. R., Mann, K. H., Ong, J. E., Silvert, W. L., Smith, S. V., Wattayakorn, G., Wulff, F., & Yanagi, T. (1996). LOICZ Biogeochemical modelling guidelines. LOICZ/R&S/95-5, VI +96 pp. LOICZ, Texel, The Netherlands. https://iwlearn.net/documents/3943.

- INEGI (2020). Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Principales resultados por localidad (ITER) 2020. https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/scitel/Default?ev=9.

- INEGI (2023). División política municipal, 1:250000. 2022, escala 1:250000. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. México.

- Jara-Marini, M. E., Molina-García, A., Martínez-Durazo, A. & Páez-Osuna, F. (2020). Trace metal trophic transference and biomagnification in a semiarid coastal lagoon impacted by agriculture and shrimp aquaculture. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 27(6), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Kiwango, H., Njau, K. N., & Wolanski, E. (2018). The application of nutrient budget models to determine the ecosystem health of the Wami Estuary, Tanzania. Ecohydrology and Hydrobiology. 18 (2), 107–119. [CrossRef]

- Lechuga-Devéze, C., Mendoza-Salgado, R., Bustillos-Guzman, J., Salinas-Zavala, C., Diaz-Rivera, E., Beltran-Camacho, C., Amador-Silva, E., Salinas-Zavala, F., Bautista-Romero, J., Balart-Paez, E., Caraveo-Patiño, J., Estrada-Enriquez, C., Pacheco-Ayub, C., Rodríguez-Villeneuve, A., Maya-Delgado, Y., González-Zamorano, P., Rivera-Rosas, J., Magallon-Barajas, F., & Portillo-Clarck, G. (2006). Programa Nacional de Diagnóstico de los Ecosistemas Costeros: Sinaloa, I Nivel Sistema Lagunar. Procuraduría Federal de Protección al Ambiente, Programa Nacional de Diagnóstico de los Ecosistemas Costeros (PNDEC). 211 pp.

- Liu, Y., & McNeil, S. (2020). Using Resilience in Risk-Based Asset Management Plans. Transportation Research Record, 2674 (4), 178-192. [CrossRef]

- López-Monroy, F. & Troccoli-Ghinaglia, L. (2017). Modelaje de la interacción entre la laguna costera tropical Las Marites (Isla de Margarita, Venezuela) y el Mar Caribe adyacente. Ciencias Básicas y Tecnología 29, 534-545.

- Marinov, D., Miladinova, S., & Marinski, J. (2014). Assessment of material fluxes in aquatorium of Burgas Port (Bulgarian black sea coast) by LOICZ biogeochemical model. In: 3rdIAHR Europe Congress, Book of Proceedings. Portugal. p. 1-10.

- Martínez-López, A., Escobedo-Urías, D. C., Chiquete-Ozono, A. Y., & Bañuelos-Valles, J. L. (2013). Estudio Ambiental – Estudio de capacidad de carga de la actividad acuícola en el Sistema lagunar Santa María. Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas. Informe Final, 23 p.

- Medina-Galván, J., Osuna-Martínez, C. C., Padilla-Arredondo, G., Frías-Espericueta, M. G., Barraza-Guardado, R. H., & Arreola-Lizárraga, J. A. (2021). Comparing the biogeochemical functioning of two arid subtropical coastal lagoons: the effect of wastewater discharges. Ecosystem Health and Sustainability 7(1), 1892532. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Galván, J., Osuna-Martínez, C. C., Padilla-Arredondo, G., Frías-Espericueta, M. G., Barraza-Guardado, R. H., León-Cañedo, J. A., & Arreola-Lizárraga, J.A. (2022). Estado trófico, dinámica de nutrientes y metabolismo neto de una laguna costera subtropical (Golfo de California) receptora de aguas residuales. Revista Internacional de Contaminación Ambiental, 38, 449-463. [CrossRef]

- Menció, A., Madaula, E., Meredith, W., Casamitjana, X., & Quintana, X.D. (2023). Nitrogen in surface aquifer - Coastal lagoons systems: Analyzing the origin of eutrophication processes. Science of The Total Environment, 871, 161947. [CrossRef]

- Miharja, M., & Arsallia S. (2017). Integrated Coastal Zone Planning Based on Environment Carrying Capacity Analysis CITIES 2016 IOP Publishing IOP Conf. Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 79012008. [CrossRef]

- Monsen, N. E., Cloern J. E., Lucas. L.V., (2003). A comment on the use of flushing time, residence time and age as transport time scales. Limnology and Oceanography 47(5), 1545–1553.

- Montaño-Ley, Y., & Soto-Jiménez M.F. 2019. A numerical investigation of the influence time distribution in a shallow coastal lagoon environment of the Gulf of California. Environmental Fluid Mechanics (2019) 19, 137–155. [CrossRef]

- Newton, A., Brito, A. B., Icely, J.D., Derolez, V., Clara, I., Angus, S., Schernewski, G., Inácio, M., Lillebø, A.I., Sousa, A.I., Béjaoui, B., Solidoro, C., Tosic, M., Cañedo-Argüelles, M., Yamamuro, M., Reizopoulou, S., Tseng, H.-C., Canu, D., Roselli, l., Maanan, M., Cristina, S., Ruiz-Fernández, A.C., Lima, R.F., Kjerfve, B., Rubio-Cisneros, N., Pérez-Ruzafa, A., Marcos, C., Pastres, R., Pranovi, F., Snoussi, M., Turpie, J., Tuchkovenko, Y., Dyack, B., Brookes, J., Povilanskas, R., & Khokhlov, V. (2018). Assessing, quantifying and valuing the ecosystem services of coastal lagoons, Journal for Nature Conservation, 44, 50-65. [CrossRef]

- Newton, A., Icely, J., Cristina, S., Perillo, G. M. E., Turner, R. E., Ashan, D., Cragg, S., Luo, Y., Tu, C., Li, Y., Zhang, H., Ramesh, R., Forbes, D. L., Solidoro, C., Béjaoui, B., Gao, S., Pastres, R., Kelsey, H., Taillie, D., Nhan, N., Brito, A. C., de Lima, R. & Kuenzer, C. (2020). Anthropogenic, Direct Pressures on Coastal Wetlands. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 8,144. [CrossRef]

- Páez-Osuna, F., Ramírez-Reséndiz, G., Ruiz-Fernández, A., & Soto-Jiménez, M. (2007). La contaminación por nitrógeno y fósforo en Sinaloa: flujos, fuentes, efectos y opciones de manejo. Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Serie Lagunas Costeras de Sinaloa, pp. 121-128.

- Pérez-Ruzafa, A., Pérez-Ruzafa, I., Newton, A., & Marcos, C. (2019). Coastal lagoons: environmental variability, ecosystem complexity, and goods and services uniformity. In: Coasts and Estuaries – the future. Eds. E. Wolanski, J. Day, M. Elliott & R. Ramachandran. Elsevier, U.K. 726 pp. [CrossRef]

- Redfield, A. C. (1934). On the Proportions of Organic Derivatives in Sea Water and Their Relation to the Composition of Plankton. James Johnstone Memorial Volume, University Press of Liverpool, 176-192.

- Reyes-Velarde, P. M., Alonso-Rodríguez, R., Domínguez-Jiménez V. P., & Calvario-Martínez, O. (2023). The spatial distribution and seasonal variation of the trophic state TRIX of a coastal lagoon system in the Gulf of California. Journal of Sea Research, 193, 102385. [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Velarde, P.M. (2022). Evaluación espacio-temporal del estado trófico en Bahía Santa María-La Reforma (MSc. Thesis). Centro de Investigación en Alimentación y Desarrollo, Mazatlán, Sinaloa, 91 p.

- Rodríguez-Zúñiga, M. T., C. Troche-Souza, A. D., Vázquez-Lule, J. D., Márquez-Mendoza, B., Vázquez- Balderas, L., Valderrama-Landeros, S., Velázquez-Salazar, M. I., Cruz-López, R. Ressl, A., Uribe-Martínez, S., Cerdeira-Estrada, J., Acosta-Velázquez, J., Díaz-Gallegos, R., Jiménez-Rosenberg, L., Fueyo-Mac Donald, L. & Galindo-Leal, C. (2013). Manglares de México/Extensión, distribución y monitoreo. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. México D.F., 128 pp.

- Romero-Beltrán, E., Aldana-Flores, G., Muñoz-Mejía, E. M., Medina-Osuna, P. M., Valdez-Ledón, P., Bect-Valdez, J. A., Gaspar-Dillanes, M. T., Huidobro-Campos, L., Romero-Correa, A., Tirado-Figueroa, E., Saucedo-Barrón, C. J., Osuna-Bernal, D. A., & Romero-Mendoza, N. (2014). Informe de Investigación: Estudio de la calidad del agua y sedimento en las lagunas costeras del estado de Sinaloa, México. Instituto Nacional de Pesca, Instituto Sinaloense de Acuacultura y Pesca, 191 pp.

- Ruiz-Ruiz T. M., Arreola-Lizárraga J. A., Morquecho L., Méndez-Rodríguez L. C., Martínez-López A., & Mendoza-Salgado, R. A. (2017). Detecting eutrophication symptoms by means of three methods in a subtropical semi-arid coastal lagoon. Wetlands 37, 1105-1118. [CrossRef]

- SADER (2020). Agricultura. Secretaria de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural. Infografía agroalimentaria del estado de Sinaloa. https://estadisticas.sinaloa.gob.mx/documentos/Infografiasagroalimentarias/Sinaloa-Infografia-Agroalimentaria-2020.pdf. Accessed on September 14th, 2024.

- SEMARNAT (2015). Acuerdo por el que se da a conocer el resultado de los estudios técnicos de aguas nacionales superficiales de la Subregión Hidrológica Río Fuerte de la Región Hidrológica número 10 Sinaloa. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales, Comisión Nacional de Mejora Regulatoria. Diario Oficial de la Federación, 11 de marzo 2015, México.

- Serrano, D., Ramírez-Félix, E., & Valle-Levinson, A. (2013). Tidal hydrodynamics in a two-inlet coastal lagoon in the Gulf of California. Continental Shelf Research, 63, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- SIAP (2023a). Anuario estadístico de la producción agrícola: Gobierno de México. https://nube.siap.gob.mx/cierreagricola/. Accessed on October 16th, 2024.

- SIAP (2023b). Anuario Estadístico de la producción Ganadera: Gobierno de México. https://nube.siap.gob.mx/cierre_pecuario/. Accessed on November 10th, 2024.

- SIS-RAMSAR (2004). Servicio de Información sobre Sitios Ramsar. Laguna Playa Colorada-Santa María la Reforma. 02-02-2004. Ramsar. https://rsis.ramsar.org/es/ris/1340?language=es. Accessed on October 22nd, 2024.

- Smith, J., Burford, M. A., Revill, A. T., Haese R. R., & Fortune, J. (2012). Effect of nutrient loading on biogeochemical processes in tropical tidal creeks. Biogeochemistry 108, 359-380.

- Swaney, D. P., Smith, S. V., & Wulff, F. (2011). The LOICZ Biogeochemical modelling protocol and its application to estuarine ecosystems. In Estuarine and Coastal Ecosystem Modelling, edited by D. Baird and A. Mehta, 135–160. Amsterdam: Academic Press.

- Testa, J. M., Kemp, W. M., Hopkinson, C. S., & Smith, S. V. (2012). Ecosystem Metabolism. In J. W. Day, B. C. Crump, W. M. Kemp, & A. Yáñez-Arancibia (Eds.), Estuarine Ecology (pp. 381–416). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118412787.ch15. [CrossRef]

- Torregroza-Espinosa, A. C., Restrepo, J. C., Escobar, J., Brenner, M., & Newton, A. (2020). Nutrient inputs and net ecosystem productivity in the mouth of the Magdalena River, Colombia. Estuarine Coastal of Shelf Science, 243, 106899. [CrossRef]

- 62. Umgiesser, G., Ferrarin, C., Cucco, A., DePascalis, F., Bellafiore, D., Ghezzo, M., Bajo, M. (2014) Comparative hydrodynamics of 10 Mediterranean lagoons by means of numerical modeling. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 119(4), 2212–2226.

- Valenzuela-Siu, M., Arreola-Lizárraga, J.A., Sánchez- Carrillo, S., & Padilla-Arredondo, G. (2007). Flujos de nutrientes y metabolismo neto de la laguna costera Lobos, México. Hidrobiológica, 17(3), 193-202.

- Villate, F., & Ruiz, A. (1989). Caracterización geomorfología e hidrológica de cinco sistemas estuáricos del País Vasco. Kobie. XVIII, 157-170.

- Vybernaite-Lubiene, I., Zilius, M., Bartoli, M., Petkuviene, J., Zemlys, P., Magri, M., & Giordani, G. (2022). Biogeochemical Budgets of Nutrients and Metabolism in the Curonian Lagoon (South East Baltic Sea): Spatial and Temporal Variations. Water, 14, 164. [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, J. T. F. (1988). Estuarine residence times, in: Hydrodynamics of estuaries, edited by Kjerfve, B., Hydrodynamics of Estuaries, CRC Press, 1, 75–84.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).