1. Introduction

The current market environment presents many challenges that companies have to face in order to remain competitive. Vinodh et al. (2013) refer the need of companies to become different, because of changes and pressures of markets, new challenges, international market, globalization, "digital age", intense competition, ethical requirements, among others. A further diversity of new products and services, the shorter product life cycle and technological development are deeply driven factors, among which are productivity increase, innovation and emergence of new models as network of companies, or virtual companies supported by Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) (Atadoga et al., 2024; Joel et al., 2024; Marcone, 2019; Mohsen, 2023; Yuliadi & Nugroho, 2019; Ivanov & Dolgui, 2020).

Today’s competitive challenges require many organizations, which need to be concerned not only with satisfying customers but also with anticipation and adaptation to environmental change with quality, agility, flexibility, resilience, efficiency and sustainability, which is essential for its success and survival (Duchek, 2019; Guo et al., 2022; Nawaz & Koç, 2019; Vinodh et al., 2013). This is in line with the LARG (Lean, Agile, Resilient and Green) paradigm presented by Carvalho et al. (2011), Carvalho et al. (2014) and Masi, & Pero (2023) that advocates that supply chains need to be the Lean, Agile, Resilient and Green. These four paradigms have the global purpose to satisfy the customer needs, increasing productivity and efficiency at the lowest cost to all members in the supply chain (Tooranloo et al., 2018). Lean supply chain seeks waste reduction (e.g. Singh & Modgil, 2020: Wainaina & Odari, 2023); Agile supply chain is focused on rapid responding to market changes, allowing the supply chain to adapt to new economic, technological, social, or environmental requirements, responding to the demands of the customers, making new products available to meet the changing new consumption trends (e.g. Cai et al., 2024; Humdan et al., 2020); Resilient supply chain as the ability to respond efficiently to disturbances, to adapt and recover from unexpected disturbances and disruptive events (e.g. Aslam et al., 2020; Yamin, 2021); Green supply chain pretends to minimize environmental impacts (e.g. Dassanayake et al., 2024; Lee & Joo, 2020).

Hu et al. (2023), investigated the impact of fairness concerns on green supply chain decisions, developing a two-tier green supply chain in which the manufacturer makes green input, and the retailer makes green marketing effort input.

The implementation of LARG paradigm could be held using more flexible production strategies (e.g., Just in time - JIT, Kanban, Lean Thinking, TQM) enabling companies to increase competitiveness, reduce costs and improve processes. In addition, e-Business allows companies to access: new markets that were not accessible before; new distribution channels; new industrial processes; new raw materials and exchange rates (Christopher, 2016). However, selecting best practices and supply chain management strategies to achieve all these goals is a complex problem involving dependencies and feedback.

This adaptation results in organizational changes to more participative, team-oriented business and management models and more updated structures (Ikhwan et al., 2021; Nagariya et al., 2021). On the other hand, Almeida et al. (2013) refer to the growth of global trade and products complexity as factors that have led many organizations to rethink their operating methods and to establish new business processes based on "joint production", and outsourcing more activities. So, there is emergence of supply chains whose strategy be based on flexible organizational structures that facilitate the change process, expanding exchange relationships with suppliers and distributors located all over the world, acting in global productive chains whose management is complex, however, extremely important to gain competitive advantage (Liao, 2020; Sinha & Rao, 2021; Srivastava & Rogers, 2021). Replacing the mass production model that was depleted because the new demands of the consumers have forced the production of customized goods, able to respond to these requirements and, consequently, to the implementation of flexible production systems (Enkel, 2014). The vertical model realized along the supply chain aims to restructure, rationalize, reduce costs, adopt better inventory management, through purchase and transportation processes, handling and storage and bet on the qualification of the suppliers (Maliyogbinda & Tijjani, 2022; Sakuramoto et al., 2019). Delegation of power and authority, teamwork and relationship between suppliers and customers and decentralization of the decision-making process, has revolutionized organizational/social models (Espino-Rodríguez & Taha, 2022; Wardani et al., 2021).

Creation of international networks to guarantee the supply, distribution and sale of goods and services, constituting global production systems, where Supply Chain Management, assumed an undoubted importance when the objective is a process optimization. In this way, competition is no longer a competition between companies and begins to be discussed at the level of supply chains, which forced them to adapt and adopt new forms of more collaborative relationships; with quality occurred the same trend (Fatorachian, 2023; Gurtu & Johny, 2021). Quality management in the supply chain should be considered not as the sum of the quality strategies of each company, with its own objectives and strategies, but as a single system of integrated, transversal and interdependent activities and processes, based on a holistic approach and managed for the entire supply chain (Chen & Tseng, 2022; Kang et al., 2018; Negri et al., 2021).

In this sense, the main objective of this study was to define an organizational structure to manage the supply chain, based on the LARG paradigm and applied to the automotive industry. In this context, the structure is an important tool that allows managers to manage in dynamic and uncertain environments and to identify organizational changes and to establish of new structures, as a key means for companies to adapt and manage and explore new markets (Al-Doori, 2019; Guzmám & Castro, 2023; Raissouni et al., 2023). This implies in most cases some internal changes: redesign of the organizational structure, redefinition of procedures, decentralization of tasks, delegation of power, reduction of hierarchical levels, definition of teams by project, or external (e.g. partnerships) (Holbeche, 2019; Nguyen, 2019; Parkhomenko, 2022). These changes aim to ensure survival, competitiveness, flexibility and responsiveness to customer needs, the identification and economic use of opportunities, company growth, efficient management of all resources, and increased productivity, profitability and competitiveness (Ciptani & Dewantari, 2020; Das & Hassan, 2021; Lin & Lin, 2019; Wachira et al., 2022). The change from competitive relationships for collaborative relationships and the change from functional integration to process integration, or from vertical integration to virtual integration are nowadays a reality (Kang et al., 2018; Maliyogbinda & Tijjani, 2022; Zimon et al., 2019).

2. Network Governance Models

The classic organizational model centered only on an isolated company, no longer makes sense. Networks present themselves as the organizational solution most appropriate to the contemporary challenges. The growing interest in cooperation and partnership relations arises from the fact that it is not possible for a single company to control all flows of materials or services, from the raw material source, up to final consumption. This phenomenon is explained by the synergistic effect in which "the result achieved by the whole is greater than the result achieved by the sum of the parts" (Ingrams, 2019; Pourcq & Verleye, 2018). Baldwin (2013) also notes that the phenomenon of globalization and the emergence of global supply chains have transformed the world and have given rise to new business models characterized by close and long-term relationships, with a small number of suppliers exchanging information, and commitment. Structural responses must therefore be based on cooperation and collaboration between companies based on models of network governance. According to Bowersox et al. (2013) and Negri et al. (2021), competitiveness is not between companies but between global and flexible, agile and resilient supply networks. Christopher (2016) and Gurtu and Johny (2021) corroborate that optimization of production and business management has been shifted from competition among individual firms to competition between supply networks. Thus, it does not make sense to consider the issues in individual terms, but rather to set strategic guidelines for the network. More than competition, cooperation between companies, as well as the creation of networks, is a current trend and appears as a new pattern of relationship between suppliers and customers, resulting from the need for organizations to provide customers with the products or services they want, with quality, speed and at the lowest cost and which aims to respond to the challenges posed (Le, 2021; Nikookar & Yanadori, 2022; Wieland & Durach, 2021). Most companies integrate one or more supply chains typically managed by the larger company, or the one who have higher bargaining power. This conduces to an interlacing between supply chains and to the network concept. This new long-term cooperation relationship conduces to new partnership contracts as alliances or joint ventures, which originates new business structures (Ağaç et al., 2023; Jun et al., 2024; Li, 2022; Liu & Liang, 2023; Liu et al., 2020). In the short term, such alliances can help to exploit market opportunities and share resources, but in the long term, the obtained competitive advantage, will depend on the capacity to identify, build and improve the skills that best suit characteristics of the current market (Bentley et al., 2021; Harrasi et al., 2023; Sun & Song, 2018).

When several companies, belonging to a supply chain, work together, they must organize themselves in order to make their operations profitable and take synergy advantages. Roth et al. (2012), in their study on governance and management of interorganizational networks, had the goal to understand how certain conditions can influence the results obtained, analysing aspects of the network as a whole and not as individual companies or simply relations between companies. In this study, it is emphasized the model called horizontal network, which presents some particular characteristics that distinguish it from other types of networks: there is no central coordination of a large company; decisions are usually taken by consensus or by the majority; most often they are formed by companies of the same sector; members can often be direct competitors. Provan and Kenis (2008) apud Roth et al. (2012) present three models of network governance from which, hybrid combinations and models can emerge: shared governance; governance with leading organization, and governance through a network administrative organization.

Roth et al. (2012) state that no model is necessarily superior in all situations. Each one has advantages and disadvantages; its use depends on the characteristics of the participants and the business environment. The shared governance model is the simplest. It is a group of organizations working collectively as a network, but do not have a formal and exclusive administrative structure. Governance can occur through formal meetings of corporate representatives or even informally, through the actions of those who are interested in the success of the network.

For these same authors, the success of this model is based on the involvement and commitment of the participating organizations. Those responsible for managing internal and external relationships of the network are the ones who make all the decisions and manage the activities of the partnership. The strength of the shared governance model is the inclusion and involvement of all partners in decision-making, as well as the flexibility and responsiveness of the network to the needs of the participants. However, the objectives and the needs of various stakeholders may conflict with the goals of the network, so this model is difficult to maintain.

About the model of the "leading organization", some authors (e.g. Guinot & Chiva, 2019; Noda, 2022) sustained this typically occurs in vertical relationships, client-supplier, where there is a larger and more powerful organization, which takes the lead role and a set of smaller and weaker firms. In this structure the network members share some common objectives to interact with each other, while maintaining individual goals.

The model of Network Administrative Organization (NAO) arises as a consequence of the inefficiency of the previous models. In this model, a separate administrative entity is created specifically to manage the network and its activities, to coordinate and sustain the network. Managing a network in this model tends to be more efficient, especially when compared to shared governance, which can become extremely complex as the number of participants increases (Roengtam et al., 2023; Sarafan et al., 2022). Comparing with the governance of a leading organization, some authors (e.g. Pourcq et al., 2018; Whetsell et al., 2019; Yi et al., 2019) emphasize that NAO is dedicated exclusively to network governance, while in that model an organization must be split between its activities and the management of the network. In this structure, partner organizations and groups can interact and work with each other, but the activities and key decisions are coordinated by a separate entity.

From these three types of network governance hybrid forms can emerge. For example, participants in a network with shared governance can institute a network administrative organization to deal with specific aspects and activities, while maintaining shared governance to remains a minimum level of involvement and participation of network actors in decisions. Provan and Kenis (2008) also believe that some forms of governance may be transitional structures, modified as the network develops.

3. Method

Aware that, neither the LARG approach nor the structuring of the supply network could be easily measured by quantitative parameters, a qualitative approach based on a case study was chosen. Data collection instruments were semi-structured interviews; documentary (secondary) sources and questionnaire surveys. To conduct the research a mixed method was choose (deductive-inductive - starting from the theory to the construction of empirical data collection instruments), after which a conceptual model for application of the LARG approach to the chosen supply network was constructed. This is an exploratory and descriptive study, supported by a case study method led in five companies, which integrate a supply chain in the Portuguese automotive industry: the automotive constructer and four first-line suppliers. It may result in a better understanding of interorganizational processes between partners in a supply network. The construction of a conceptual map was fundamental to outline the problem, based on the literature review.

4. Conceptual Map

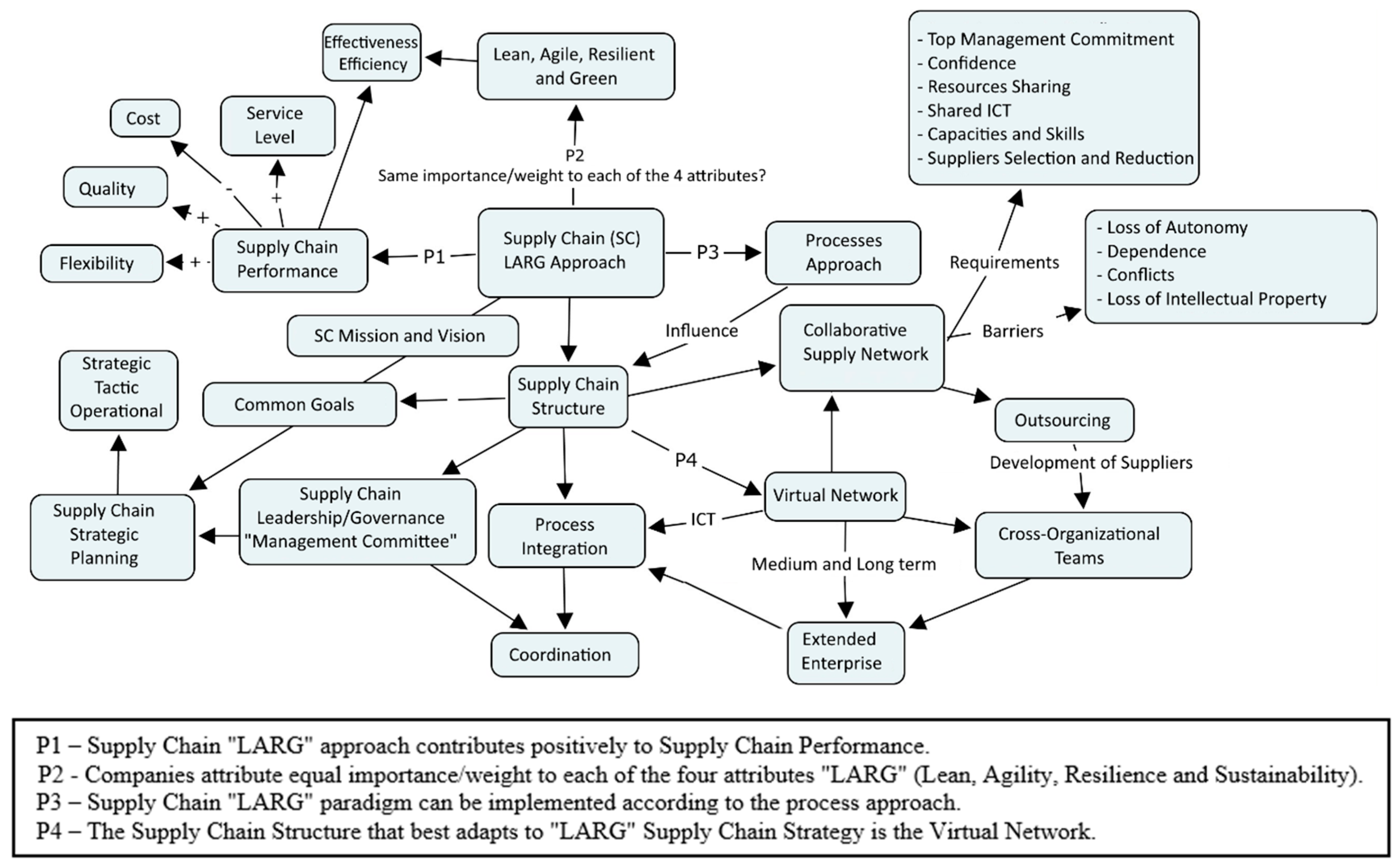

A conceptual map represents, through a hierarchical diagram, relationships between concepts. This tool was used, and a map was designed allowing to summarize, visualize and understand some of the associations resulting from the “state of the art” literature review (

Figure 1) based in the research of Rolo et al. (2014). It was designed to capture supply chain dynamics and present the relationships between concepts (P1, P2, P3 and P4). The hierarchies and conceptual groupings only seek to represent meaningful propositional relations between concepts, not related to operations sequences of a flow diagram.

Quality based on the LARG approach assumes that the supply network follows a lean, agile, resilient and green orientation. From the literature review, preposition 1 (P1) – Supply Chain "LARG" approach contributes positively to Supply Chain Performance, was corroborated by Carvalho et al. (2010) and Carvalho et al. (2011), that revealed the way to understand how management characteristics influence the design of performance measures. On these papers, the authors presented the results of LARG approach on supply chain performance indicators related to the four listed attributes (Flexibility, Costs, Quality and Service Level), and provided the following findings: the key performance indicator “service level” is affected positively by the management characteristics “replenishment frequency”, “capacity surplus” and “integration level” (however, it is affected negatively by the “lead time”) on the other hand “lead time” reduction improves the “service level.

The key performance indicator “cost” is affected positively by the “capacity surplus”, “inventory level”, “replenishment frequency” and “production lead time”. Interviewed CEOs of the studied companies corroborates contribution to increase effectiveness and efficiency. During the interviews, respondents enunciated some management practices for each of the LARG attributes and gave concrete examples of real situations from which it can be concluded that, the implementation of Lean practices can reduce costs, waste and consumption of energy and water are the practices where the five companies more converge. Although the adoption of LARG management practices have been justified by the respondents, with proven positive impacts in terms of economic and operational performance, corroborating the results of Azevedo et al. (2011) and Carvalho et al. (2010), the respondents do not all attribute the same importance to each of the attributes (proposition 2 - P2).

Thus, the survey results indicate that in the case of these companies, the implementation was focused essentially on Lean practices (4.7), Agility (4.2) and not less on sustainability - Green (4.3), in a Likert scale of 1 to 5. However, suppliers, although they include some practices in their daily life, do it in a less intense way, clearly emphasizing lean practices (4.5) and the remaining attributes did not score higher than 3.9.

In the conceptual map it is considered too that, LARG approach will influence the mission and vision, because of its "strategic" nature; Usually defined at the level of each individual company, it is proposed to define the mission and vision for the supply chain. This implies the definition of common goals reflected in the supply chain strategic plan, which will desirably culminate with the planning of the network at strategic, tacit and operational level. It is suggested that a "management committee" be set up to ensure the supply chain governance.

Proposition 3 (P3) states that: "The LARG paradigm should be implemented according to the process approach", in an allusion to the Supply Chain Operations Reference - SCOR Model that was developed in 1996 by the Supply Chain Council. SCOR Model it is a management tool developed to establish standard processes for the supply chain network at the level of the structure (decomposition levels, management metrics and best practices evaluation), from the supplier of the supplier to the customer of the customer. This tool enables the involved partners to solve, improve and communicate management practices of the SC network, as well as describe the activities of the network, through their decomposition into processes. This decomposition makes possible to study both, single and complex chains, and to identify improvement opportunities in the information flow between companies or industries in different sectors of activity, that integrate the same SC or collaborative network. The result is a management model whose efficiency is based on continuous improvement and integrated management of the supply network. According to SCOR, the supply chain management processes associated with all phases of customer satisfaction are five: planning, supply, production, delivery and return. The process approach suggests a horizontal structure as ideal, whose characteristics are suited to operating a virtual network as a collaborative supply network and whose requirements are based on the reduction of the supplier base.

Supply chain structure will be defined to allow process integration. This process integration will allow data from different process and from different members os the supply chain and the information from the multi-disciplinary to be crossed and coordinated. It is needed to understand the commitments necessary to the integration of Lean, Agile, Resilient and Green SC paradigms, to achieve a competitive and sustainable SC.

The influence of LARG approach in the supply chain structure can be perceived in terms of partner’s choice. The decision: to make or to buy, defines outsourcing level. Working on a collaborative network instead a regular supply chain, is not easy. It requires the commitment of top management, confidence, resource sharing, information and communication technology sharing, and the selection and reduction of the number of suppliers (it is not possible to work closely and collaboratively with a huge number of suppliers). However, barriers and obstacles cannot be overlooked, with the main barriers to cooperation in the supply network identified as: loss of autonomy and intellectual property, dependency, opportunistic behaviour and mistrust that could undermine the cooperative relationship like other conflicts. In order the supply network to work in a virtual and sustainable way, it is necessary to integrate and coordinate activities and processes, only possible using ICT to ensure the flow of information in a timely manner. Coordination plays a fundamental role to mitigate uncertainty (Holweg et al. 2005; Wu & Raghupathi, 2015) with the help of synchronizing information flows. A medium-to-long-term virtual network leads to an expanded enterprise (EE), defined by Davis and Spekman, (2004, p. 20 apud Alguezaui & Filieri, 2014) as “the entire set of collaborating companies both upstream and downstream, from raw materials to end-use consumption, that work together to bring value to the marketplace”. The EE promotes collaboration between manufacturers and suppliers following a win-win strategy. It is a flexible and adaptive organisational model that contributes to a more efficient way to manage a supply network. Cross-organizational teams emerge as the ideal format, joining elements from different companies.

5. LARG Supply Chain Strategy and Structure

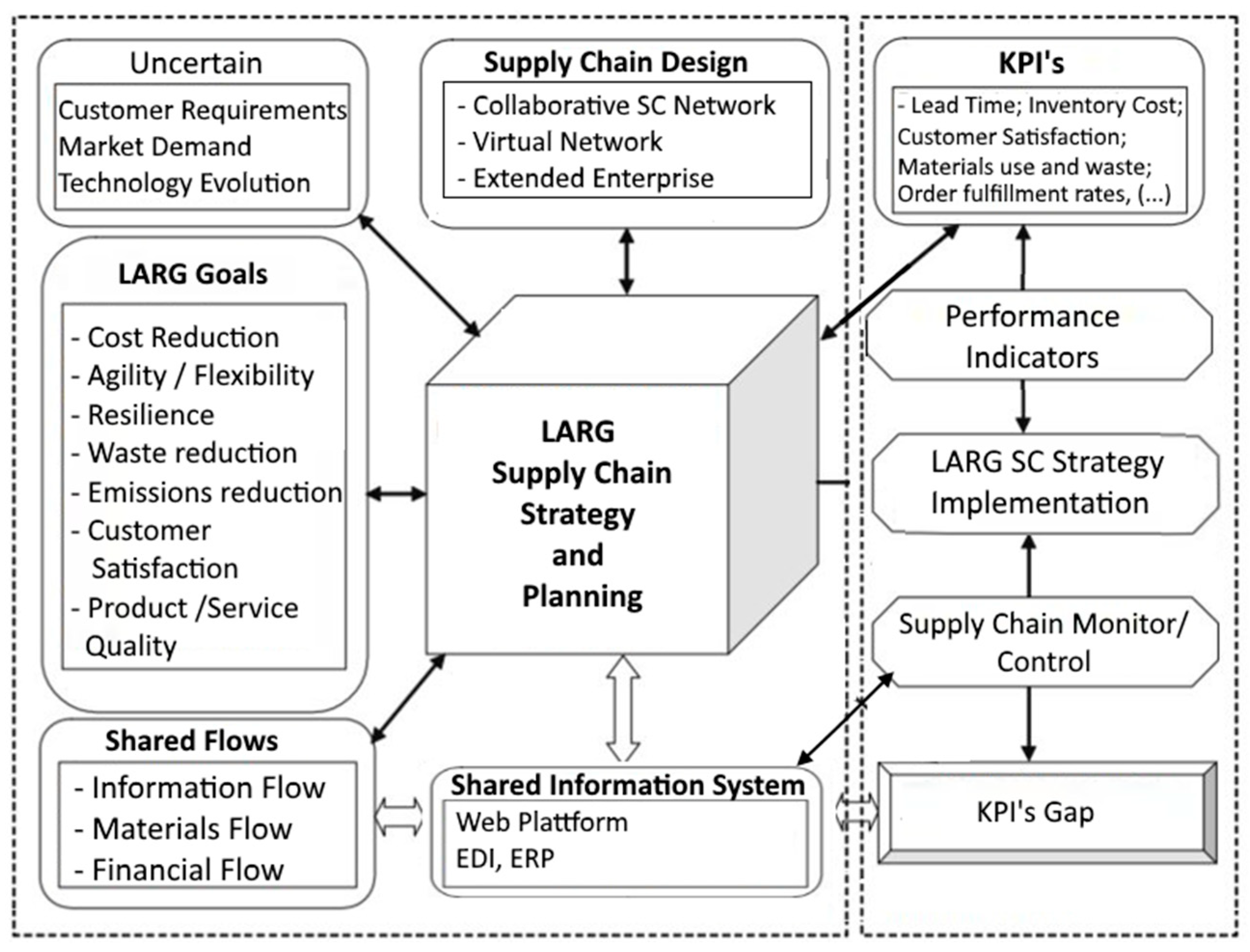

After summarizing the main concepts in the conceptual map, it is necessary to identify which network structure model best suits the implementation of the strategy based on the LARG paradigm. It will be necessary to define SC goals; SC design; SC strategy; how to monitor; the performance indicators and SC information flows, as shown in

Figure 2.

The developed framework, presented on

Figure 2, aims to increase effectiveness and efficiency and has been constructed as a result of literature review and data collection.

Today, changes in supply chain management (SCM) are made to provide more flexible, and responsive supply chains. Adaptive supply chains (ASCs) with heterogeneous structures and extensive application of Web services are expected to be more flexible and reactive, and capable of rapid evolution and surviving competition. The main concern is related to how joint different structures that coexist in supply chain management (e.g., functional, organizational, informative, financial).

It should be emphasized that, one of the main supply chain features is the multiple structure design and changeability of structures parameters related to different stages of the supply chain life cycle. Over the last decade, some valuable approaches to supply chain strategic, tactical and operational planning have been extensively developed (Christopher, 2016, Harrison et al., 2019).

The main application of the proposed framework is the adaptive planning of supply chain characterized by LARG strategy approach, that better adapt to the uncertain environment, related to market demand and competitive environment, increasingly demanding customers and the fast evolution of technology that contributes to shorter product life cycle.

Supply chains planning is done by setting a composed of management strategic “LARG” goals and defining measures for their achievement. LARG goals were related to cost reduction, service level and environmental impact. Measures like reduction of emissions, waste reduction, agility, customer satisfaction and cost reduction obtained by the application of lean practices, were used by the studied companies.

This tool enables to measure the goals calculating the Key Performance Indicators (KPI’s) allowing to monitor LARG approach application (e.g., lead time, inventory cost, customer satisfaction, materials use and waste, order fulfilment rates, and other indicators that could be useful). Decisions about supply chain structure design, strategy, and planning require a robust information systems support, shared by the network partners. In this way, we propose to consider LARG paradigm planning as an adaptive process that encapsulates the planning of the shared information, defining the shared information system supported by web platform, joint Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) or Electronic Data Interchange (EDI), becoming a virtual network. A collaborative supply chain network operating as a virtual network that could be considered as an Extended Enterprise (EE), flexible and adaptable, is the suggested structure.

In the automotive sector, manufacturers recognize the need to work cooperatively with the suppliers on the development of product and process and joint problem-solving and risk-sharing. The reduction of product development costs and the acceleration of the process of bringing products to the market present themselves as the main advantages (Alguezaui & Filieri, 2014; Paolucci et al., 2021; Škerlič, 2020; Sonar et al., 2022; Teplická et al., 2023). Cooperation with suppliers should also include testing and validation, which can contribute to timely delivery and quality enhancement, and to supplier assessment and development. In general terms, we can say that the managers of the 5 studied companies are in agreement with the proposed model and its application will be tested.

6. Final Considerations

A state-of-the-art literature review was performed to identify conceptual relations among supply chain LARG approach, SC performance and the SC structure. The main objective was to identify supply chain structure that allows to obtain flexibility and agility. LARG practices help to improve functions like reducing uncertainty, quality improvement, cost minimisation which can finally lead towards customer satisfaction which is the ultimate aim of any company or supply chain. Based on the results observed in this study, it may be stated that supply chain network collaboration was identified as an effective and efficient way to network members improve collective and own performance. Collaborative management of the supply chain aims to maximize strategic sourcing and the potential synergies between the members of the supply chain, assuming that each member adopts Lean, Agile, Resilient and Green management practice, in line with the network strategy, network performance will increase. To achieve sharing partnerships and effective collaborative planning with key suppliers, sharing information is needed.

The studied supply chain used information systems, and common management tools, as SAP and EDI, to share relevant information like production plans, for example. That is crucial when companies work in a Lean approach, applying, for example, "just in time" (JIT) or, even more demanding, in "just in sequence" (JIS). The framework application to the case study offered a good perspective of usefulness and application but future research is needed to analyse the operations of the supply chain as a collaborative network anchored in LARG paradigm.

Limitations and Future Research

Considering that this is an exploratory case study, it restricts inferences, thus making it impossible to generalise the results, and so the conclusion drawn can only be applied to this specific case and within the assumptions established in this study.

It was difficult to reconcile the four LARG attributes, which have been studied in groups of two, e.g. Lean versus Green, Lean and Agile, and it is not always easy to operationalise the combination of the four attributes simultaneously, as committing to one may result in sacrificing another.

A limitation identified in this study was the fact that only five companies that were part of the car manufacturer’s supply chain were analysed - the Focus Company and four of its first-tier suppliers, located on the industrial estate - so including the remaining first-tier suppliers, as well as the second-tier suppliers and distributors in the study, in order to carry out a broader investigation, would make it possible to better characterise the supply chain, its integration/coordination, as well as to better identify its advantages.

The creation of a set of key performance indicators (KPIs) to measure the performance of the LARG supply network is a proposal for future research.

In future research, it is recommended the use of quantitative methods of investigation in order to get an in-depth understanding of how the LARG attributes will increase supply chain efficiency and effectiveness.

Other future research could include applying the conceptual model to other supply networks in other sectors of activity, and other levels in the network (including suppliers). supply networks in other sectors of activity, and other levels in the network (including 2nd line suppliers), in a comparative analysis with the aim of suppliers), in a comparative analysis with the aim of verifying the suitability of the model to different realities, sectors of activity, levels and forms of cooperation between companies.

Another future research is exploring supply chain operations as collaborative networks anchored in the LARG paradigm, leveraging emerging technologies such as blockchain, guided by the research of Difrancesco et al. (2023) and Chen (2024). Blockchain technology has grown rapidly in recent years and has shown transformative potential for supply chain management (Wang, Chen, Xiao, Su, Govindan & Skibniewski. 2023). By offering transparent, secure, and decentralized information sharing capabilities, blockchain has the potential to address current inefficiencies in supply chain operations, such as fragmented information and lack of trust among participants. While the opportunity for blockchain applications is significant, knowledge about its concrete benefits beyond cryptocurrencies remains limited and fragmented. To address this gap, future research should incorporate blockchain technology to enhance supply chain collaboration, efficiency, and resilience. A closed-loop value chain perspective can provide insights into the benefits of blockchain across supply chain processes—from sourcing and production to final delivery and reverse logistics. Furthermore, the use of quantitative research methods will allow for a more detailed analysis of how LARG attributes, combined with blockchain, can further improve supply chain efficiency and effectiveness. This approach will also help identify the managerial impacts, challenges, and limitations of blockchain implementation. By integrating blockchain into the LARG framework, supply chains can move toward a more innovative and adaptive future with improved coordination and performance across the network.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R. and M.S.; methodology, A.R., M.S. and T.N.; validation, A.R., M.S., T.N. and R.A.; formal analysis, A.R. and M.S.; investigation, A.R. and M.S.; resources, A.R. and M.S.; data curation, A.R. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, A.R., M.S., T.N. and R.A.; visualization, A.R., M.S., T.N. and R.A.; supervision, M.S.; project administration, M.S.; funding acquisition, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia through the ISCTE (Instituto Universitário de Lisboa - Portugal), grant UIDB/00315/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All documents, data, and information used in this work are available to the public.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ağaç, G., Baki, B., & Ar, İ. M. (2023). Blood supply chain network design: a systematic review of literature and implications for future research. Journal of Modelling in Management, 19(1), 68-118. [CrossRef]

- Al-Doori, J. A. (2019). The impact of supply chain collaboration on performance in automotive industry: empirical evidence. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 12(2), 241. [CrossRef]

- Alguezaui, S., & Filieri, R. (2014). A knowledge-based view of the extending enterprise for enhancing a collaborative innovation advantage. In: International Journal of Agile Systems and Management, 7 (2), 116–131. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R. Toscano, C. Azevedo, A.L., & Carneiro, L.M. (2013). A Collaborative Planning Approach for Non-Hierarchical Production Networks. In: R. Poler, L.M. Carneiro, T. Jasinski, M. Zolghadri & P. Pedrazzoli (Eds.), Intelligent Non-hierarchical Manufacturing Networks, John Wiley & Sons. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, H., Khan, A. Q., Rashid, K., & Rehman, S. A. (2020). Achieving supply chain resilience: the role of supply chain ambidexterity and supply chain agility. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management, 31(6), 1185-1204. [CrossRef]

- Atadoga, A., Obi, O.C., Osasona, F., Onwusinkwue, S., Daraojimba, A.I., & Dawodu, S.O. (2024). Ai in supply chain optimization: a comparative review of usa and african trends. International Journal of Science and Research Archive, 11(1), 896-903. [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, A., Chauhan, S.S., & Goyal, S.K. (2010). A fuzzy multicriteria approach for evaluating environmental performance of suppliers. International Journal of Production Economics, 126 (2), 370-378. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, S. G., Carvalho, H., & Machado, V. C. (2011). The influence of green practices on supply chain performance: A case study approach. Transportation research part E: logistics and transportation review, 47(6), 850-871. [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, R. (2013). Global supply chain: why they emerged, why they matter, and where they are going. In: Deborah Elms & Patrick Low (eds). Global Value Chain in a Changing World. Geneva: World Trade Organization.

- Bentley, J. R., Robinson, J. C., & Zanhour, M. (2021). Managerial political skill and achieved supply chain integration: the mediating effects of supply chain orientation and organizational politics. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 27(3), 451-465. [CrossRef]

- Bowersox, D.J., Closs, D.J., Cooper, M.B., & Bowersox, J.C. (2013). Supply Chain Logistics Management (Fourth Edition). Nova Iorque: McGraw-Hill.

- Cai, J., Sharkawi, I., & Taasim, S. I. (2024). The role of deep learning in supply chain collaboration and cooperation. Journal of Organizational and End User Computing, 36(1), 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, H., Azevedo, S., & Cruz-Machado, V. I. (2014). Trade-offs among lean, agile, resilient and green paradigms in supply chain management: a case study approach. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Management Science and Engineering Management: Focused on Electrical and Information Technology Volume II (pp. 953-968). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, H., Azevedo, S., & Cruz Machado, V. (2010). Supply Chain Performance Management: lean and green paradigms. International Journal of Business Performance and Supply Chain Modelling, 2, (3/4), 304-333. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, H., Duarte, S., & Cruz Machado, V. (2011). Lean, Agile, Resilient and Green: divergencies and synergies. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 2 (2), 151-179. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., & Tseng, T. (2022). Modeling the quality enablers of supplier chain quality management. Sage Open, 12(4). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. (2024). How blockchain adoption affects supply chain sustainability in the fashion industry: a systematic review and case studies. International Transactions in Operational Research, 31, 3592–3620. [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M. (2016). Logistics & Supply Chain Management. (5th Edition), Pearson Education.

- Ciptani, M. K., & Dewantari, Y. W. (2020). The effect of supply chain quality integration on supply chain management practice to achieve supply chain performance. Journal of Applied Accounting and Finance, 3(2), 124. [CrossRef]

- Das, S., & Hassan, H. K. (2021). Impact of sustainable supply chain management and customer relationship management on organizational performance. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 71(6), 2140-2160. [CrossRef]

- Dassanayake, A., Gamaarachchi, T., Ranathunge, I., & Karunarathna1, N. (2024). The role of green supply chain practices on environmental sustainability. SLIIT Business Review, 2(2), 47-76. [CrossRef]

- Difrancesco, R.M., Meena, P., & Kumar, G. (2023). How blockchain technology improves sustainable supply chain processes: a practical guide. Operations Management Research, 16, 620–641. [CrossRef]

- Duarte, S., & Cruz-Machado, V. (2013). Modelling lean and green a review from business models. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma, 4 (3), 228-250. [CrossRef]

- Duchek, S. (2019). Organizational resilience: a capability-based conceptualization. Business Research, 13(1), 215-246. [CrossRef]

- Enkel, E., & Heil, S. (2014)- Preparing for distant collaboration: Antecedents to potential absorptive capacity in cross-industry innovation. Technovation, 34 (4), 242-260. [CrossRef]

- Espino-Rodríguez, T. F., & Taha, M. G. (2022). Supplier innovativeness in supply chain integration and sustainable performance in the hotel industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 100, 103103. [CrossRef]

- Fatorachian, H. (2023). The significance of industry 5.0 in the globalization of supply chain management. European Economic Letters (EEL), 13(5), 872-885. [CrossRef]

- Guinot, J., & Chiva, R. (2019). Vertical trust within organizations and performance: a systematic review. Human Resource Development Review, 18(2), 196-227. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., Chen, Y., Usai, A., Wu, L., & Wu, Q. (2022). Integração de conhecimento para resiliência entre PMEs multinacionais em meio à covid-19: da visão de plataformas digitais globais. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(1), 84-104. [CrossRef]

- Gurtu, A., & Johny, J. (2021). Supply chain risk management: literature review. Risks, 9(1), 16. [CrossRef]

- Guzmám, G. M., & Castro, S. Y. P. (2023). Collaboration, eco-innovation and economic performance in the automotive industry. International Journal of Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, 5(3), 200-219. [CrossRef]

- Harrasi, N. A., Din, M. S. E., Masengu, R., Balushi, B. A., & Habsi, J. A. (2023). Knowledge and skills gap of graduates entry-level: perception of logistics and supply chain managers in Oman. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 13(6), 1269-1285. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A., Van Hoek, R., & Skipworth, H. (2019). Logistics Management and Strategy: Competing through the Supply Chain (5th ed.). Pearson Education.

- Holbeche, L. (2019). Designing sustainably agile and resilient organizations. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 36(5), 668-677. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H., Li, Y., Li, Y., Li, M., Yue, X., & Ding, Y. (2023). Decisions and Coordination of the Green Supply Chain with Retailers’ Fairness Concerns. Systems, 11 (1), 5. [CrossRef]

- Humdan, E. A., Shi, Y., & Behnia, M. (2020). Supply chain agility: a systematic review of definitions, enablers and performance implications. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 50(2), 287-312. [CrossRef]

- Ikhwan, K., Rahardjo, B., & Ratnawati, S. (2021). Learning organization in determining supply chain performance. Jurnal Manajemen Dan Agribisnis. [CrossRef]

- Ingrams, A. (2019). Organizational design in open government: two cases from the United Kingdom and the United States. Public Performance & Management Review, 43(3), 636-661. [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, D., & Dolgui, A. (2020). A digital supply chain twin for managing the disruption risks and resilience in the era of Industry 4.0. Production Planning & Control - The Management of Operations, 32(9), 775–788. [CrossRef]

- Joel, O.S., Oyewole, A.T., Odunaiya, O.G., & Soyombo, O.T. (2024). Leveraging artificial intelligence for enhanced supply chain optimization: a comprehensive review of current practices and future potentials. International Journal of Management & Entrepreneurship Research, 6(3), 707-721. [CrossRef]

- Jun, H., Jie, W., Fei, Z., & Mengzhe, W. (2024). Contract selection for collaborative innovation in the new energy vehicle supply chain under the dual credit policy: cost sharing and benefit sharing. International Journal of Industrial Engineering Computations, 15(1), 209-222. [CrossRef]

- Kang, M., Yang, M. G., Park, Y., & Huo, B. (2018). Supply chain integration and its impact on sustainability. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 118(9), 1749-1765. [CrossRef]

- Le, P. B. (2021). Determinants of frugal innovation for firms in emerging markets: the roles of leadership, knowledge sharing and collaborative culture. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 18(9), 3334-3353. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Joo, H. (2020). The impact of top management’s support on the collaboration of green supply chain participants and environmental performance. Sustainability, 12(21), 9090. [CrossRef]

- Li, C. (2022). Coordination and optimization of supply chain considering the double fresh-keeping effort of supplier and 3pl. Frontiers in Sustainable Development, 2(8), 29-42. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y. (2020). An integrative framework of supply chain flexibility. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 69(6), 1321-1342. [CrossRef]

- Lin, D., & Lin, L. (2019). Corporate governance quality and capital structure decisions: empirical evidence from Canada. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 6(9), 303-311. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. D., Tian, Y., & Zhang, X. M. (2020). Supply chain coordination and decision under effort-dependent demand and customer balking behavior. International Journal of Industrial and Systems Engineering, 34(1), 1. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., & Liang, J. (2023). Research on risk propagation in complex supply chain networks based on seir model. Frontiers in Business, Economics and Management, 7(3), 245-254. [CrossRef]

- Maliyogbinda, J., & Tijjani, U. (2022). Framework for integration of vertical public health supply chain systems: a case study of Nigeria. International Journal of Supply Chain Management, 7(1), 1-27. [CrossRef]

- Marcone, M. R. (2019). Innovative supply chain in made-in-Italy system. the case of medium-sized firms. Journal of Corporate Governance, Insurance, and Risk Management, 6(2), 50-62. [CrossRef]

- Masi, A., & Pero, M. (2023, September). Integrating Lean, Agile, Resilient and Green Supply Chain Management in Engineer-to-Order Contexts: Insights from Expert Interviews. In IFIP International Conference on Advances in Production Management Systems (112-125). Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland. [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, B. M. (2023). Impact of artificial intelligence on supply chain management performance. Journal of Service Science and Management, 16(01), 44-58. [CrossRef]

- Nagariya, R., Kumar, D., & Kumar, I. (2021). Sustainable service supply chain management: from a systematic literature review to a conceptual framework for performance evaluation of service only supply chain. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 29(4), 1332-1361. [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, W., & Koç, M. (2019). Exploring organizational sustainability: themes, functional areas, and best practices. Sustainability, 11(16), 4307. [CrossRef]

- Negri, M., Cagno, E., Colicchia, C., & Sarkis, J. (2021). Integrating sustainability and resilience in the supply chain: a systematic literature review and a research agenda. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(7), 2858-2886. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N. T. D. (2019). Experiences in supply chain quality management practices in Vietnam: studying on steel manufacturing company and packaging manufacturing company B. International Journal of Business and Management, 14(7), 171. [CrossRef]

- Nikookar, E., & Yanadori, Y. (2022). Forming post-covid supply chains: does supply chain managers’ social network affect resilience?. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 52(7), 538-566. [CrossRef]

- Noda, Y. (2022). Intermunicipal cooperation, integration forms, and vertical and horizontal effects in Japan. Public Administration Review, 83(3), 654-678. [CrossRef]

- Paolucci, E., Pessot, E., & Ricci, R. (2021). The interplay between digital transformation and governance mechanisms in supply chains: evidence from the Italian automotive industry. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 41(7), 1119-1144. [CrossRef]

- Parkhomenko, N. (2022). Formation of organizational development strategy of enterprise in context of changes in international environment. Management and Entrepreneurship: Trends of Development, 1(19), 20-27. [CrossRef]

- Pourcq, K. D., & Verleye, K. (2018). How & why governance dynamics emerge in inter-organizational networks: a meta-ethnographic analysis. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2018(1), 17901. [CrossRef]

- Pourcq, K. D., Regge, M. D., Heede, K. V. d., Voorde, C. V. d., Gemmel, P., & Eeckloo, K. (2018). Hospital networks: how to make them work in Belgium? facilitators and barriers of different governance models. Acta Clinica Belgica, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Provan, K., & Kenis, P. (2008). Modes of network governance: structure, management and effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Oxford, UK, 18 (2), 229-252. [CrossRef]

- Raissouni, R., Hamiche, M., Bourekkadi, S., & Raissouni, K. (2023). The impact of the integrated supply chain on the operational performance of companies in the Moroccan electric vehicle sector. E3S Web of Conferences, 412, 01039. [CrossRef]

- Roengtam, S., Agustiyara, A., & Nurmandi, A. (2023). Making network governance work in forest land-use policy in the local government. Sage Open, 13(3). [CrossRef]

- Rolo, A., Pires, A.M.R., & Saraiva, M. (2014). Supply Chain as a Collaborative Virtual Network Based on LARG Strategy. In: Xu, J., Cruz-Machado, V., Lev, B., Nickel, S. (eds) Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Management Science and Engineering Management. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, 280, 701-712. [CrossRef]

- Sakuramoto, C., Sério, L. C. D., & Bittar, A. (2019). Impact of supply chain on the competitiveness of the automotive industry. RAUSP Management Journal, 54(2), 205-225. [CrossRef]

- Sarafan, M., Lawson, B., Roehrich, J., & Squire, B. (2022). Knowledge sharing in project-based supply networks. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 42(6), 852-874. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R., & Modgil, S. (2020). Assessment of lean supply chain practices in Indian automotive industry. Global Business Review, 24(1), 68-105. [CrossRef]

- Sinha, V., & Rao, B. V. (2021). An empirical investigation of global production networks in Indian manufacturing sector. The Indian Economic Journal, 70(1), 174-189. [CrossRef]

- Škerlič, S. (2020). Factors that influence logistics decision making in the supply chain of the automotive industry. Transport Problems, 15(3), 117-126. [CrossRef]

- Sonar, H., Mukherjee, A., Gunasekaran, A., & Singh, R. K. (2022). Sustainable supply chain management of automotive sector in context to the circular economy: a strategic framework. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(7), 3635-3648. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M., & Rogers, H. (2021). Managing global supply chain risks: effects of the industry sector. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, 25(7), 1091-1114. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L., & Song, G. (2018). Current state and future potential of logistics and supply chain education: a literature review. Journal of International Education in Business, 11(2), 124-143. [CrossRef]

- Teplická, K., Khouri, S., Mudarri, T., & Freňáková, M. (2023). Improving the quality of automotive components through the effective management of complaints in industry 4.0. Applied Sciences, 13(14), 8402. [CrossRef]

- Tooranloo, H. S., Alavi, M., & Saghafi, S. (2018). Evaluating indicators of the agility of the green supply chain. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal, 28(5), 541-563. [CrossRef]

- Vinodh, S., Devadasan, S.R., Vimal, K.E.K., & Kumar, D. (2013). Design of agile supply chain assessment model and its case study in an Indian automotive components manufacturing organization. Journal of Manufacturing Systems, 205. [CrossRef]

- Wachira, K. M., Mburu, D. K., & Kiai, R. M. (2022). Total quality management practices and supply chain performance among manufacturing and allied companies listed at Nairobi securities exchange, Kenya. European Journal of Business and Management Research, 7(1), 269-279. [CrossRef]

- Wainaina, M., & Odari, S. (2023). Lean supply chain practices and the performance of kassmatt supermarkets limited. International Journal of Supply Chain Management, 8(1), 89-112. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.J., Chen, Z.C., Xiao, L., Su, Q., Govindan, K., & Skibniewski, M.J. (2023). Blockchain adoption in sustainable supply chains for Industry 5.0: A multistakeholder perspective. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 8(4). [CrossRef]

- Wardani, V. K., Zulkarijah, F., & Rumijati, A. (2021). The effect of supply chain management on operational performance of furniture industry in jombang regency. Jamanika (Jurnal Manajemen Bisnis Dan Kewirausahaan), 1(1), 47-55. [CrossRef]

- Whetsell, T. A., Leiblein, M. J., & Wagner, C. S. (2019). Between promise and performance: science and technology policy implementation through network governance. Science and Public Policy, 47(1), 78-91. [CrossRef]

- Wieland, A., & Durach, C. F. (2021). Two perspectives on supply chain resilience. Journal of Business Logistics, 42(3), 315-322. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S. J., & Raghupathi, W. (2015). The Strategic Relationship between Information and Communication Technologies and Delivery of Sustainability: A Country-Level Study. Journal of Global Information Management, 23 (3), 92-115. [CrossRef]

- Yamin, M. (2021). Investigating the drivers of supply chain resilience in the wake of the covid-19 pandemic: empirical evidence from an emerging economy. Sustainability, 13(21), 11939. [CrossRef]

- Yi, H., Huang, C., Chen, T., Xu, X., & Liu, W. (2019). Multilevel environmental governance: vertical and horizontal influences in local policy networks. Sustainability, 11(8), 2390. [CrossRef]

- Yuliadi, B., & Nugroho, A. (2019). Integration between management capability and relationship capability to boost supply chain project performance. International Journal of Supply Chain Management, 8(2), 241-252. [CrossRef]

- Zimon, D., Tyan, J. C., & Sroufe, R. (2019). Implementing sustainable supply chain management: reactive, cooperative, and dynamic models. Sustainability, 11(24), 7227. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).