1. Introduction

News provide essential information that shapes and influences citizens’ opinions and interests [

1,

2,

3]. In this direction, the news that appears in newspapers on various conflicts and crisis around the world, model citizens’ perspectives and beliefs [

4]. Different newspapers explain the same news by emphasizing different aspects, contextualizing them differently and using more or less extreme language. The linguistic terms used depend on the journalist’s background, the editorial line, the ideology of the media outlet and the strategic interests of the country to which the media outlet belongs. In order to jointly analyze the sentiment about an event based on news from various media outlets it is necessary to take these differences into account. A new method of analysis is needed that takes into account this information not explicitly stated in the linguistic terms themselves but rather in the tradition of each media outlet in the use of these linguistic terms.

In this article, we introduce a methodology capable of taking into account the media’s tradition in the use of linguistic terms used in writing news. This methodology is based on

hesitant fuzzy linguistic term sets (HFLTSs), which enable the representation of uncertainty and the aggregation of information with different degrees of precision. HFLTS can be considered as an extension of hesitant fuzzy sets introduced by V. Torra [

5]. These structures have been usually employed in linguistic computation and are particularly applied in contexts where understanding people’s emotions or sentiments is of interest [

6,

7,

8]. The methodology proposed in this article is also based on the concept of

perceptual map, recently developed in the context of HFLTS and which allows taking into account different meanings for the same linguistic terms depending on the media who uses them. Concretely, we believe that the linguistic scales used have a different meaning for the media of each country. The interpretation of these linguistic scales can be deduced from a previous news baseline.

We conduct a comparative analysis of news coverage across some European countries in relation to the Israel-Gaza war. To achieve this, sentiment analysis is first employed to capture the emotional tone, specifically the negative emotional tone and underlying feelings regarding the news about the Israel-Gaza war. For this study, we utilize a large-scale news media coverage dataset from the GDELT (

Global Database of Events, Location, and Tone) Project, which tracks news coverage in more than 100 languages worldwide [

9]. This open- source dataset is intended to facilitate the analysis of trends and offer insights into the behaviors driving various events. The information is gathered from a wide range of sources, including major international, national regional, and local news outlets. Additionally, both local services and global news agencies contribute to the platform [

10].

HFLTSs provide an effective conceptual framework for dealing with the problem of knowledge representation in environments characterized by imprecision and hesitancy. HFLTSs are particularly suited for incorporating diverse perspectives, including the representation of individual opinions and the qualitative fusion of multiple viewpoints to capture group consensus [

11,

12]. These models, an extension of hesitant fuzzy sets introduce by V. Torra [

5], have advanced within linguistic computation and are particularly applied in contexts where understanding people’s emotions or sentiments is of interest [

6,

7,

8].

We study and compare news perception among four European countries, specifically, Germany, France, Spain and the UK, towards the Israel-Gaza war during the first ten months of the war, from 7th October, 2023 to 7th August, 2024. In particular, in this study, we have considered the following newspapers: Bild (bild.de), Süddeutsche Zeitung (sueddeutsche.de), Die Welt (welt.de), Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (faz.net) and Die Tageszeitung (taz.de) from Germany; La Croix (la-croix.com), Le Monde (lemonde.fr), Les Echos (lesechos.fr), Libération (liberation.fr), l’Humanité (humanite.fr) and Le Figaro (lefigaro.fr) from France; ABC (abc.es), El Periódico (elperiodico.com), La Razón (larazon.es), El País (elpais.com) and La Vanguardia (lavanguardia.com) from Spain; Daily Mail (dailymail.co.uk), Independent (independent.co.uk), The Guardian (theguardian.com), The Telegraph (telegraph.co.uk) and BBC (bbc.co.uk) from UK, among the most read newspapers in each of the countries considered. This selection includes some of the most relevant media in each country and covers a broad spectrum of ideologies and sensitivities. To obtain the specific meaning of the different linguistic scales, a baseline is constructed by analyze the use of the different linguistic terms by media of each country from the first week of the months from January to September 2023. In this way, this approach goes beyond surface-level interpretations, taking into account the distinct narrative traditions and unique linguistic expressions inherent to each language ([

13,

14]).

The following sections of the paper are organized as follows.

Section 2 represents the fundamental concepts of linguistic perceptual maps, perceptual-based distance and centroid. Then, in

Section 3, we delve into the real case study, analyzing news coverage and perceptions of the Israel-Gaza war. We introduce our methodology and discuss the results we obtained. Finally, conclusions, challenges and future research directions are drawn in

Section 4.

2. Preliminaries

This section includes definitions of key preliminary concepts on HFLTSs and linguistic perceptual maps based on [

15] that are necessary for the methodology presented.

Let S be a totally ordered set of basic linguistic terms (BLTs), S=, with , we consider the concept of hesitant linguistic terms, which correspond to intervals of consecutive BLTs.

Definition 1 ([

11]). A

Hesitant fuzzy linguistic term set (HFLTS)over

S is a subset of consecutive BLTs of

S, i.e.,

,for some

with

. For completeness, the empty set

is also considered as a HFLTS and it is called the

empty HFLTS.

The non-empty HFLTSs are denoted by . If is the singleton . The set of all non-empty HFLTSs over S is denoted by , that is, . In this way, the set of all HFLTSs over S is .

Example 1. Let S be a totally ordered set of basic linguistic terms with granularity , being low, medium, high and very high. Given the negative sentiments corresponding to the news of three different newspapers from the same country in a specific day, X = considerably high, Y = low, and Z = not low but not very high, their respective HFLTSs could be represented, for instance, as , and .

In

, the

set inclusion relation (⊆) provides a partial order. The connected union of two HFLTSs is defined as the least element of

, based on the subset inclusion relation ⊆, that contains both HFLTSs. The

connected union together with the

intersection provide to the set of HFLTSs,

, a

lattice structure, as proven in [

14].

Unlike quantitative values (numbers), the meaning of linguistic labels is not always the same and depends greatly on the context and, above all, on the user’s background [

16,

17]. For this reason, the concept of

linguistic perceptual map was introduced in [

18] as a normalized measure in the set of HFLTSs. Different users may handle the same linguistic labels but different perceptual maps.

The following definition introduces the concept of linguistic perceptual map into together the concept of width of HFLTSs.

Definition 2 ([

15]). Let us consider a normalized measure

over

S, i.e.,

such that

. For any

, we call

the

width of the basic label

. Given

, then the

widthof

H is

. The pair

, that we also denote as

, is called

linguistic perceptual map.

Any linguistic perceptual map is uniquely associated with a partition of the interval into n sub-intervals of lengths and also with a set of landmarks . The relationship between the landmarks and the width of the basic linguistic labels is and , for any and .

Example 2. Considering the same three newspapers from Example 1, let’s assume that in their country . Then and

To compare linguistic terms expressed in different linguistic perceptual maps, in this paper, following the procedure introduced in [

15], we consider the

common perceptual map that provides a unified context. Although the common perceptual map usually has a higher granularity, it is the adequate framework to represent, fuse and compare different expressions of the same linguistic terms.

Definition 3 ([

15]). Let

a set of

k linguistic perceptual maps. Let

, for

, the sets of landmarks of the

k partitions associated. The

common perceptual map, ,is the linguistic perceptual map associated to the partition,

, of landmarks

. The cardinality of this partition satisfies

In addition, based on the linguistic perceptual maps lattice structure, a perceptual-based distance between HFLTSs is defined. This distance will allow us to introduce the concept of centroid.

Definition 4 ([

18]). Let

be a linguistic perceptual map. Given

,the

perceptual-based distance between and is defined as:

Example 3. Considering the same three newspapers from previous examples, and assuming

. According to Equation (

1), the distances between X, Y and Z are

,

and

.

In [

18] it is proved that this definition is indeed a distance in

. The centroid of a set of HFLTSs is introduced in order to obtain a collective opinion.

Definition 5 ([

18]). Let

be a linguistic perceptual map. Let

be a set of HFLTSs, the

centroid of this set, denoted as

, is defined as:

In [

18], it was proved that the centroid can be any term from the set:

where

is the set that contains just the median if

k is an odd number or the set of two central values and any integer number between them if

k is even.

Example 4. Following previous examples, the centroid of the three newspapers’ negative sentiments is: . Note that, since , and , 2 is the median of the set of three left-hand indexes and 3 is the median of the set of three right-hand indexes .

On the other hand, given a set of k linguistic perceptual maps and its corresponding common perceptual map , the projection of basic linguistic terms is defined in the following way.

Definition 6 ([

15]). Let

be a set of BLTs and

be one of the linguistic perceptual maps from the set

in which, for the sake of simplicity, we avoid the index

m. Let

be the common perceptual map with

. The

projection function of BLTs is

defined by

, holding

and

, for each

.

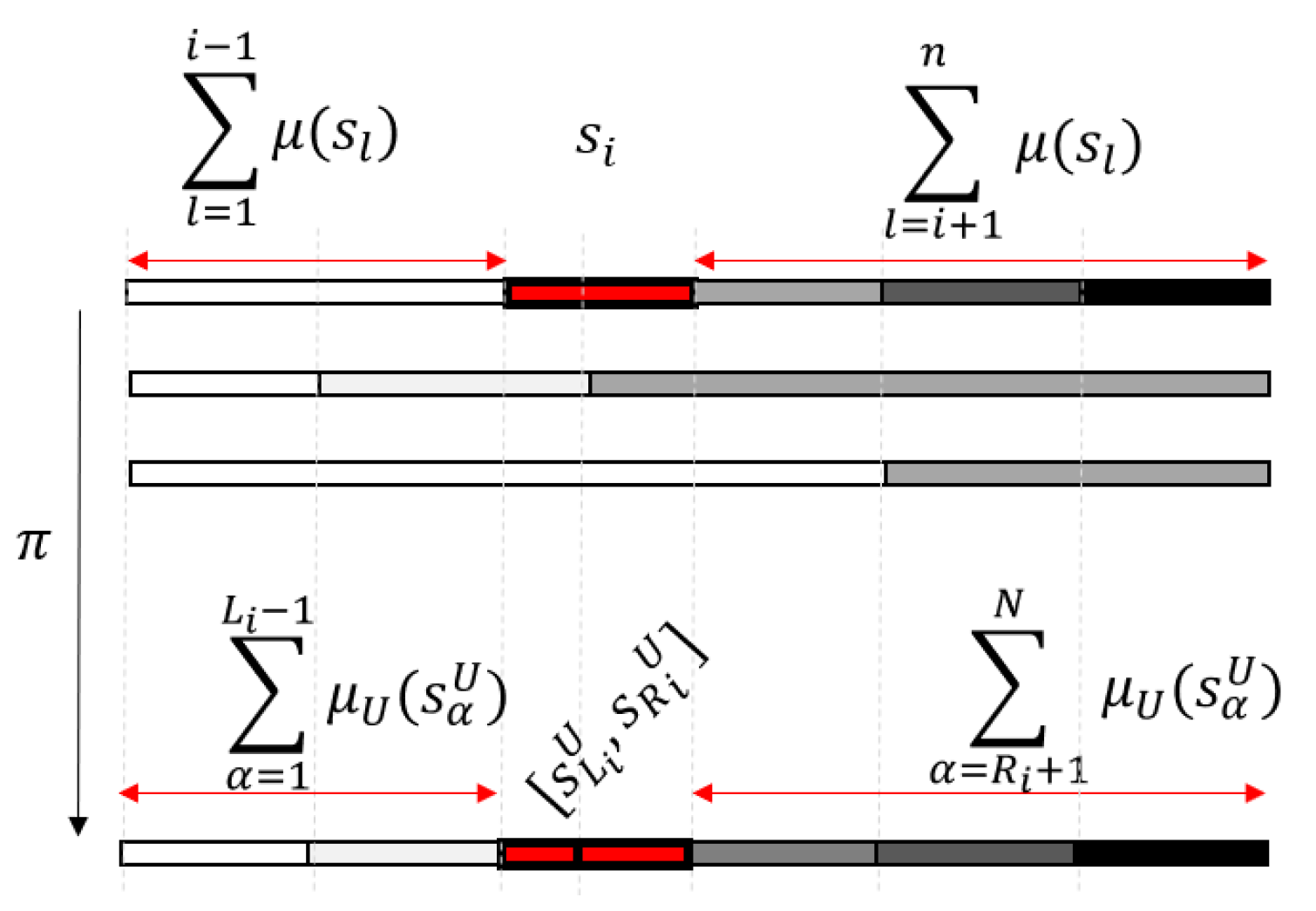

Note that every basic linguistic term

divides the unit interval in three parts corresponding respectively to:

on its left side,

itself, and

on its right side. From Definition 6, we obtain that the projection

preserves the measures of the left and right sides of

(see

Figure 1).

The following definition extends the projection function from Definition 6 to non basic HFLTSs through the connected union.

Definition 7. ([

15]) Let

be a set of BLTs and

be one of the linguistic perceptual maps from the set

. Let

and let

denote the common perceptual map. The

projection function associates to a HFLTS

, the element

For the empty set

.

In [

15] it was proved that the projection

constitutes a monomorphism between lattices (injective and that preserves the lattice operations) and that it also preserves the set inclusion and the preference order relation.

Example 5. In line with previous examples, let us also consider the negative sentiments associated with news from three different newspapers from a different country on the same day, X’= between medium and high, Y’= very high, Z’= medium, the respective HFLTSs for these newspapers presented as follows: , and , lets assume that in this country . Then and The centroid of the three newspapers’ negative sentiments is: From the two original linguistic perceptual maps, the common perceptual map is obtained: . The projected centroids for the two countries form original perceptual maps into common perceptual map are respectively, and .

3. A Comparative Analysis of Media Coverage: A Real Case Study

In this section, we first introduce a methodology, based on the conceptual framework outlined in

Section 2, to analyze and compare the negativity of news coverage on a specific topic of public interest across various countries or regions during an specific period. We then apply this methodology to examine and compare negative sentiment in public media coverage of the Israel-Gaza war across four European countries: Germany, France, Spain, and the UK.

3.1. Methodology

The approach used to develop and implement the use case is structured around the following seven steps:

- Step 1

Define a baseline of linguistic terms for negative sentiment: To achieve this, we analyze a prior period of time to establish a baseline across all countries. The news negative sentiment during this time period is divided into four distinct levels, corresponding to the linguistic terms "Low", "Medium", "High", and "Very High".

- Step 2

Deduce countries’ linguistic perceptual maps: For each country, the linguistic perceptual map is generated based on the relative frequency with which newspapers in that country were associated with the four defined levels of negative sentiment during the previous period of time. The motivation for assigning distinct linguistic perceptual maps to different countries lies in the differences in how negative language is used in those nations.

- Step 3

Obtain Common Perceptual Map: Based on the perceptual maps established for each country, , the common perceptual map, is computed following Definition 3. For simplicity in both reference and computation, the landmarks in the comm perceptual map are renamed .

- Step 4

Select articles associated with the concerned topic during the target period of time: In this step, we identify news articles that reference the concerned topic or actors involved. According to GDELT terminology, an actor can refer to a person, country, geographic area, or organization closely associated with the topic. News articles are filtered based on either the topic itself or one of these types of actors.

- Step 5

Represent negative sentiment on each country’s linguistic perceptual map and project it to the common perceptual map: For each country, articles’ negative sentiment during the defined period is categorized using its specific linguistic perceptual map with levels assigned as "Low", "Medium", "High", or "Very high". Then we project articles’ negative sentiment to the common perceptual map for comparison among countries.

- Step 6

Compute the centroid for each country per day: Based on Definition 5, for each day within the selected period, we calculate four distinct centroids on the common perceptual map, reflecting the central opinion of each country.

- Step 7

Compare the news negativeness among countries: For each day we calculate the distances from each country’ centroid to the term in the common perceptual map that has the maximum level of negativity. We then compare these results to identify which country exhibits the strongest negativity on a daily basis throughout the period.

3.2. Analysis of Media Coverage of Israel-Gaza War

The experimental setup of this case study is based on a dataset sourced from the GDELT dataset [

9]. In GDELT data set, the tone for an articles is quantified across six emotional dimensions: the average tone of the articles, the positive score, negative score percentage of words found in the tonal dictionary, percentage of active words, and percentage of self/group reference[

4].

This study focuses specially on the negative score. The negative score represents the percentage of words conveying a negative emotional connotation. We have selected this dimension because negativity was the prevailing emotion in the tone of news during the specified period, from October 7th, 2023 to August 7th, 2024. This is attributed to the negative impact of the war on the news sentiment presented in European newspapers.

Specifically, we study and compare news negative sentiment among Germany, France, Spain and the UK towards the Israel-Gaza war during the first ten months of the war. To this end, we have considered the following newspapers: Bild (bild.de), Süddeutsche Zeitung (sueddeutsche.de), Die Welt (welt.de), Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung (faz.net) and Die Tageszeitung (taz.de) from Germany; La Croix (la-croix.com), Le Monde (lemonde.fr), Les Echos (lesechos.fr), Libération (liberation.fr), l’Humanité (humanite.fr) and Le Figaro (lefigaro.fr) from France; ABC (abc.es), El Periódico (elperiodico.com), La Razón (larazon.es), El País (elpais.com) and La Vanguardia (lavanguardia.com) from Spain; Daily Mail (dailymail.co.uk), Independent (independent.co.uk), The Guardian (theguardian.com), The Telegraph (telegraph.co.uk) and BBC (bbc.co.uk) from UK, among the most prominent online newspapers in these countries. The GDELT Project translates articles written in other languages into English.

As stated in Step 1 in the methodology, we define a baseline of linguistic terms considering the selected countries’ news during a previous period of time . The period considered before the start of the war is specifically one week per month from January to September, 2023. We discretized the negative sentiment during this period considering the selected newspapers of each country to determine the quartiles (see Table 1). In Table 2, the distribution of the four levels of linguistic terms for the negative sentiment: "Low", "Medium", "High", and "Very high" are presented.

Following step 2, the linguistic perceptual map landmarks are calculated from the relative frequency of newspapers within the country associated with the four defined levels of negative sentiment. These relative frequencies determine the widths of the basic labels in the country’s perceptual map.

Table 2.

Distribution of the linguistic terms in the four countries.

Table 2.

Distribution of the linguistic terms in the four countries.

| Negative Tone |

Germany |

France |

Spain |

UK |

| Low |

24% |

19% |

31% |

23% |

| Medium |

22% |

27% |

28% |

24% |

| High |

24% |

29% |

24% |

25% |

| Very high |

30% |

25% |

17% |

28% |

For each country, we use the relative frequency of the levels of negative sentiment (see Table 2) to define the landmarks in the partition associated with the linguistic perceptual map. The corresponding partitions of the unit interval, and their resulting perceptual maps, are the following for Germany (1), France (2), Spain (3), and the United Kingdom (4), respectively:

;

;

;

.

Note that, for example, the language used in German newspapers tends to exhibit more extreme negative values than in the rest of the countries. The measures of the most negative basic linguistic term are respectively and

Next, as outlined in step 3, the common perceptual map is obtained following Definition 4. The partition associated with the common perceptual map is:

Note that the cardinals of , , and are equal to 4 in all countries, while the cardinal of is in this case.

Following step 4, articles were collected over a 10-month period, from October 7th, 2023, the day the war began, to August 7th, 2024, before other countries in the area started to be involved in the war.

We represent negative sentiment of these articles on each country’s linguistic perceptual map and project it to the common perceptual map, as stated in step 5.

Then, in accordance with step 6, we calculate a centroid per each day and country within the common perceptual map. Finally, as it is detailed in the final step in the methodology , we compute their distances to the maximum value of the common perceptual map, i.e. to numerically compare the negative sentiment of news among countries.

3.3. Results

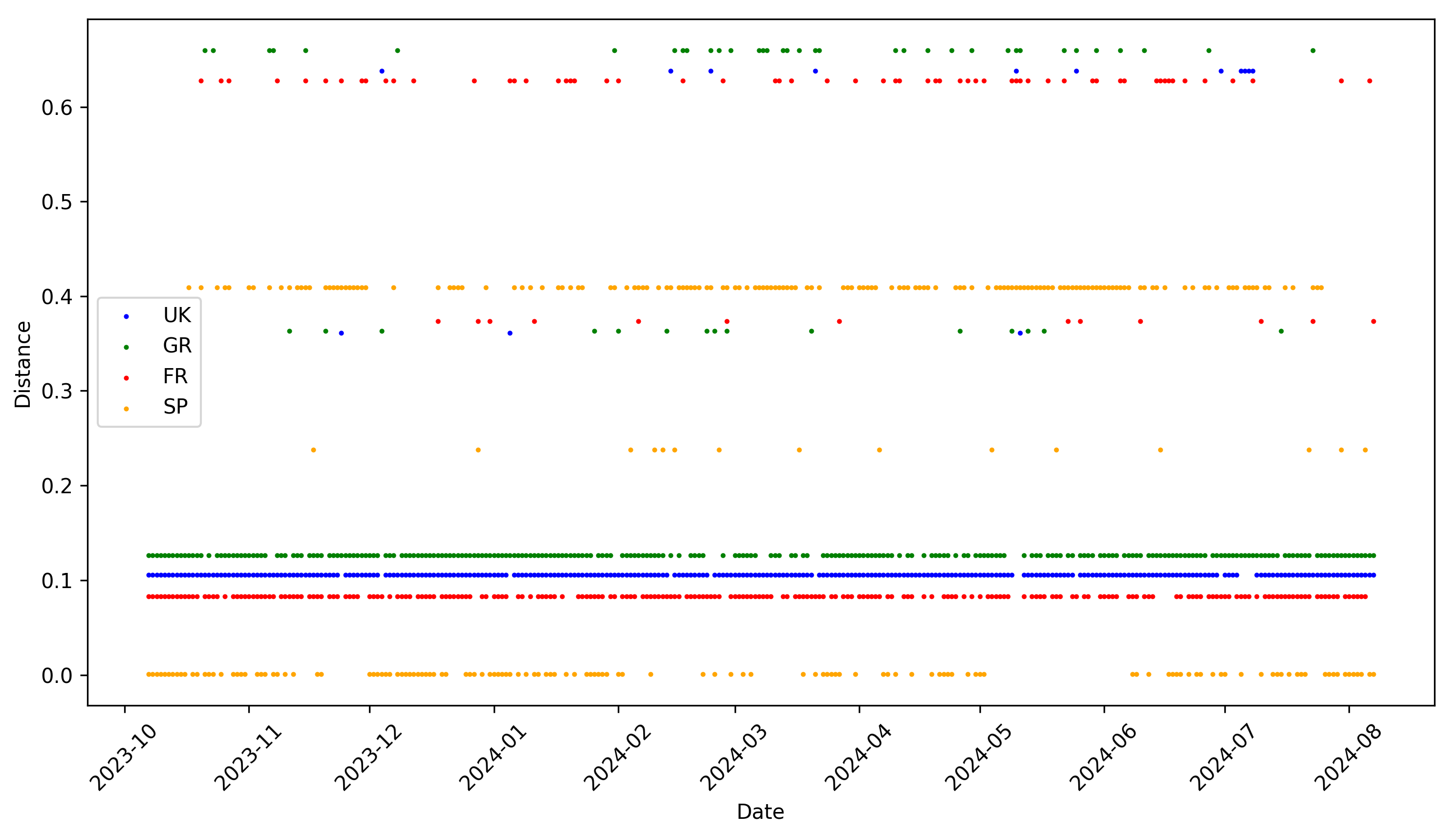

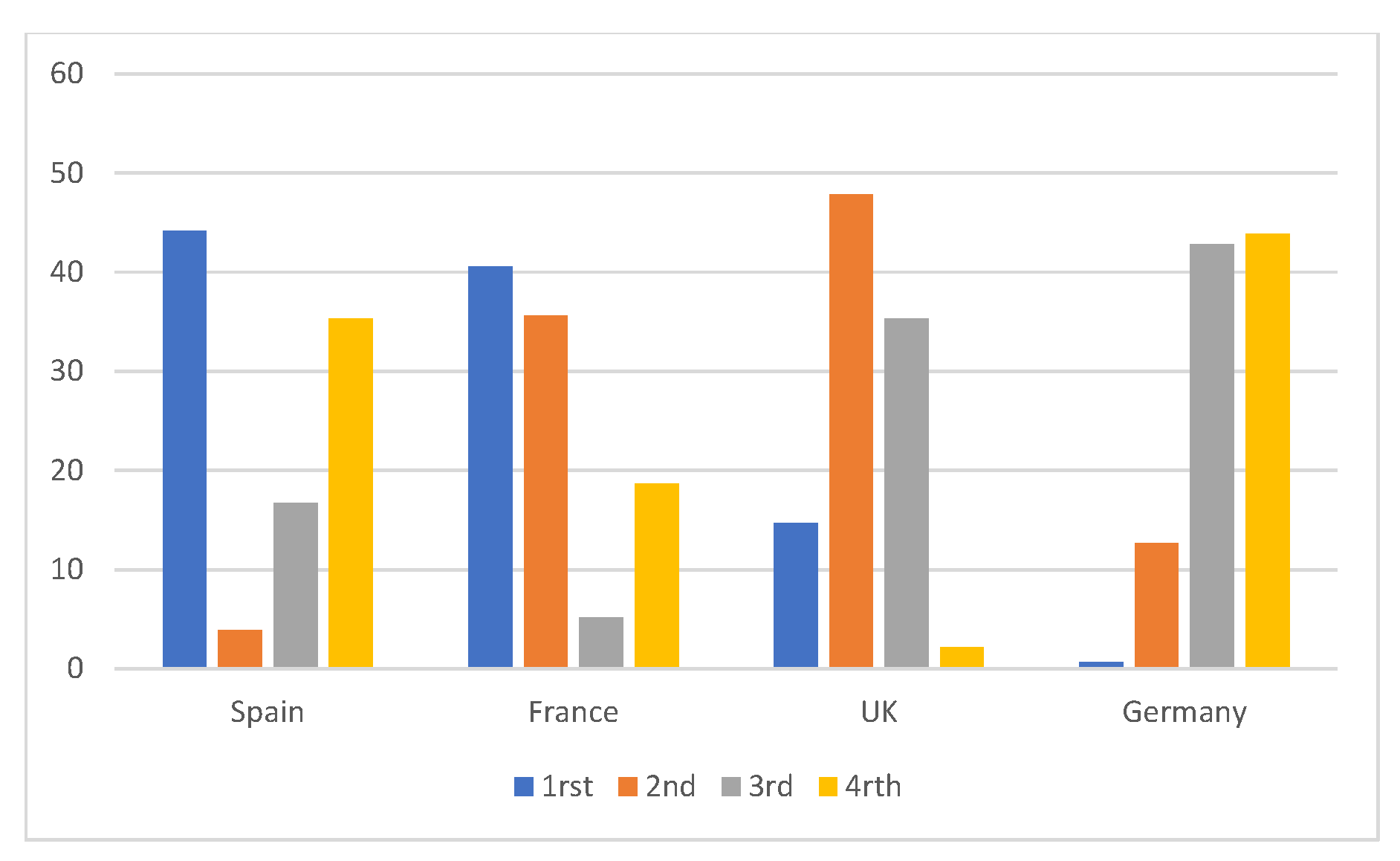

In this subsection we present results of our analysis of media coverage of Israel-Gaza war. When comparing per each day distances to among countries, the results show that there are relevant differences among them. In the 44.12% of days during the period, Spain is the country with the most negative sentiment towards the war. In the 40.52% of days during the period, France is the country with the most negative sentiment towards the war. In the 14.71% of days during the period, United Kingdom is the country with the most negative sentiment towards the war. Only in two days during the period, Germany is the country with the most negative sentiment towards the war. Specifically, the days in which Germany is the country with the most negative sentiment are November 24th, 2023 and July 8th, 2024.

Figure 2 illustrates the distances from each country’s centroids to the maximum negative value on the common perceptual map. When the distance is close to zero, the negative sentiment of the corresponding country is very high.

As an example to illustrate results represented in

Figure 2 over a brief time frame, Table 3 presents the distances from each country’s centroids to the maximum negative value in the common perceptual map for a ten-day period in January 2024.

Table 3.

An example of the distances to the maximum negative value in the common perceptual map: from January 6th to January 15th, 2024.

Table 3.

An example of the distances to the maximum negative value in the common perceptual map: from January 6th to January 15th, 2024.

| Date |

Germany |

France |

Spain |

UK |

The most negative |

| 06-01-2024 |

0,1258 |

0,6275 |

0,4089 |

0,1058 |

UK |

| 07-01-2024 |

0,1258 |

0,0828 |

0,0006 |

0,1058 |

Spain |

| 08-01-2024 |

0,1258 |

0,0828 |

0,4089 |

0,1058 |

France |

| 09-01-2024 |

0,1258 |

0,6275 |

0,0006 |

0,1058 |

Spain |

| 10-01-2024 |

0,1258 |

0,0828 |

0,4089 |

0,1058 |

France |

| 11-01-2024 |

0,1258 |

0,3736 |

0,0006 |

0,1058 |

Spain |

| 12-01-2024 |

0,1258 |

0,0828 |

0,0006 |

0,1058 |

Spain |

| 13-01-2024 |

0,1258 |

0,0828 |

0,4089 |

0,1058 |

France |

| 14-01-2024 |

0,1258 |

0,0828 |

0,0006 |

0,1058 |

Spain |

| 15-01-2024 |

0,1258 |

0,0828 |

0,0006 |

0,1058 |

Spain |

As can be seen in Table 3, during this ten-day period, Spain exhibited the most negative sentiment towards the war for six days, followed by France for three days and the UK for one day.

Finally, in

Figure 3 we show the percentage of days on which each country expressed the most negative sentiment, as well as the second, third, and fourth highest levels of negativity over the 10-month period, from October 7th, 2023 to August 7th, 2024.