1. Introduction

The study of depressive symptomatology among older adults has received considerable attention in academia, particularly within gerontological social work [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Among the key predictors linked to depressive symptoms is economic disadvantage. Older adults with limited financial resources often face ongoing stress related to meeting basic needs, such as housing, healthcare, and daily expenses. This persistent financial insecurity can lead to increased depressive symptoms. Importantly, these symptoms are influenced not only by absolute income levels but also by relative economic deprivation, defined as the unequal distribution of valued resources among individuals within the same group or community [

5,

6]. While much of the existing literature focuses on absolute measures of economic disadvantage, a growing body of research suggests that relative income may also play a critical role in shaping mental health outcomes [

7,

8].

Relative economic deprivation within neighborhoods can significantly affect mental health, including depressive symptomatology. For individuals with fewer material resources residing in areas with lower poverty rates, the disparity between their economic status and that of their neighbors may intensify feelings of inadequacy, exacerbating depressive symptoms [

9,

10]. In sum, living in a neighborhood where residents perceive most of their neighbors to be wealthier than them can heighten feelings of relative deprivation, potentially worsening depressive symptoms.

However, there is a gap in existing research about this association targeting for older adult populations. Rather, most studies encompassed broader age groups. Only a handful of studies focused on relative economic positions and depressive symptomatology in later life [

7,

11,

12]. Older adults, who often live on fixed incomes due to retirement, may be particularly sensitive to feelings of relative deprivation. Even when their income is sufficient to meet their needs, perceiving themselves as economically disadvantaged compared to their neighbors can exacerbate depressive symptoms [

13]. This sense of relative deprivation arises from unfavorable social comparisons within one’s neighborhood, leading to feelings of inadequacy, stress, and isolation [

7].

This study aims to fill this gap by exploring the relationship between neighborhood relative income and depressive symptoms using a sample of older adults from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), combined with data from the American Community Survey (ACS). Guided by relative deprivation theory and the relative position hypothesis, this study posits that lower relative income within one’s neighborhood is associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms among older adults.

1.1. Theoretical Background

Relative deprivation theory and the relative position hypothesis provide a comprehensive framework for understanding how socioeconomic inequities within neighborhoods contribute to mental health inequities. Relative deprivation theory [

6,

14] posits that individuals assess their social and economic standing through comparisons with others in their community. Feelings of deprivation arise when individuals perceive themselves as worse off, leading to stress and negative emotional outcomes [

15]. Among older adults, this may be especially salient because they may have limited opportunities to improve their economic standing due to retirement or reduced earning potential. As such, even if their absolute income provides for their basic needs, the awareness of relative deprivation in wealthier neighborhoods may contribute to stress, anxiety, or depressive symptoms [

15,

16]. This suggests that perceptions of one’s relative financial status, rather than objective measures alone, play a critical role in shaping mental health outcomes.

The relative position hypothesis further suggests that the perception of one’s lower status within a community may have direct health consequences [

13,

17]. When people perceive themselves as occupying a lower status relative to others, they are more likely to engage in negative social comparisons. These comparisons can generate harmful emotions such as stress, which, over time, erode both physical and mental well-being. Additionally, inequities in social status may hinder the development of trust and social cohesion, further exacerbating the negative health effects associated with a lower relative position. Therefore, from the empirical and theoretical review, this study aims to explore the relationships between neighborhood relative income and depressive symptoms of older adults.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

This study utilized merged data from the American Community Survey (ACS) 2014-2018 5-year estimates data and the RAND HRS Longitudinal File (V2) public-use data [

18,

19]. Compared to the original HRS data, the RAND HRS data includes fewer missing values due to imputations of income, wealth, and medical expenditures. The current study also used restricted-use data (University of Michigan IRB #2016-021; Texas Tech University IRB #2020-976), which is called “HRS Cross-Wave Detailed Geographic Information,” to merge the ACS data with the RAND HRS data, based on the Census tract information of the HRS respondents [

20]. The HRS (Health and Retirement Study) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (NIA U01AG009740 and NIA R01AG073289) and is conducted by the University of Michigan. The final sample comprised 3,071 individuals aged 65 and older.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Depressive Symptoms

In the HRS, depressive symptoms were asked using an eight-item short form of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Depression (CES-D) scale [

21]. The HRS participants were asked if they experienced specific symptoms in the past week (e.g., feeling depressed, feeling alone, feeling sad, etc.). Responses were binary (yes/no), and two positively worded items (feeling happy, enjoying life) were reverse-coded. The total score ranged from zero to eight, with higher scores indicating more counts of depressive symptoms. This eight-item version is well validated and widely used for assessing depressive symptoms, particularly in aging [

22].

2.2.2. Neighborhood Relative Income

Neighborhood relative income was operationalized by the relative position of study participants according to their 2016 household income level within each Census tract group. It was calculated by standardization based on the Census tract’s median household income. Because income distribution is highly skewed and research consistently shows a logarithmic relationship between income and health, the income data were also log-transformed [

23]. To measure neighborhood relative deprivation, the following formula was used: Neighborhood relative deprivation = ln(family income at the household level) – ln(median household income at the Census tract level)) / ln(median household income at the Census tract level).

Here were the detailed steps for calculating the neighborhood relative income. First, family income data at the household level for the year 2016 were collected for each study participant (RAND HRS data). Additionally, the median household income for the Census tract in which each participant resides was obtained (ACS data). Next, for each Census tract, the median household income and the degree to which incomes varied were calculated to understand the overall income distribution within the tract. The median income was used as a reference point, while the variation in incomes provided insight into how different incomes were within the tract. Following this, the relative standing of participants’ income within their Census tract was determined. This involved assessing how far their income deviated from the median income of the tract. The result was a standardized score that indicated the participant’s relative income position compared to others in their tract. These standardized scores were then interpreted to assess whether a participant was relatively more affluent or more deprived within their Census tract. Finally, because these scores were standardized, they allowed for direct comparisons across different Census tracts, even if those tracts had varying income distributions. For example, a score indicating relative income in one tract would reflect the same level of relative income in another tract, even if the actual income levels were different.

2.2.3. Covariates

This study incorporated a robust set of individual- and neighborhood-level covariates to ensure a comprehensive analysis aligned with the study’s theoretical framework and research objectives. At the individual level, the covariates included age (actual age in years), gender (1=female, 0=male), marital status (1=married or partnered, 0=other, including married but spouse absent, separated, divorced, widowed, and never married), and educational attainment (years of education). These factors were selected based on their established relevance in shaping both individual experiences of relative deprivation and mental health outcomes.

At the neighborhood level, the percentage of individuals over age 65, unemployment rate, and poverty rate within each Census tract were included to reflect key dimensions of socioeconomic and demographic contexts. The inclusion of the tract-level population aged 65 and older aimed to capture the influence of a higher concentration of older adults on neighborhood dynamics, acknowledging that older populations may face unique social, economic, and health-related challenges that contribute to neighborhood-level deprivation and may affect depressive symptoms among residents, particularly older adults. Similarly, incorporating tract-level unemployment and poverty rates allowed for a broader understanding of socioeconomic conditions that may exacerbate feelings of deprivation and their associated mental health impacts.

These covariates were prioritized as they address both individual and contextual factors central to the study’s focus on neighborhood relative income and depressive symptoms, providing a balanced and theoretically grounded approach to understanding these complex relationships.

2.3. Analysis Plan

The study employed negative binomial regression to model the relationship between neighborhood relative income and depressive symptoms [

24,

25]. Given that depressive symptoms were measured as a count variable, this approach was appropriate as it accounts for overdispersion in the data, a common issue in count-based health outcomes (e.g., depressive symptoms). Prior to model estimation, checks for overdispersion were conducted to confirm the suitability of the negative binomial regression model. Robust standard errors were applied to address potential heteroscedasticity. The analysis controlled for both individual-level and neighborhood-level covariates to isolate the effect of neighborhood relative income on depressive symptoms.

3. Results

Table 1 summarizes the sample characteristics, and

Table 2 shows the bivariate relationships between all study variables (

Table 1 and

Table 2). On average, participants reported 1.389 depressive symptoms, indicating a relatively low level within the theoretical range of 0 to 8. The average age was approximately 77 years old but ranged from 65 to 99. Less than a half were married or partnered. The correlation coefficient between depressive symptoms and neighborhood relative income was small but statistically significant.

Table 3 shows the detailed negative binomial regression results (

Table 3). The regression model was statistically significant (

Wald χ2=1516.310,

p < .001). The overdispersion parameter (alpha) was not zero (

alpha=1.216,

p < .001), which supported the appropriateness of using the negative binomial regression model. Pseudo R

2 was .016. The negative binomial regression results demonstrated a significant negative association between neighborhood relative income and depressive symptoms, even after controlling for individual and neighborhood-level covariates. Specifically, individuals with lower relative economic positions reported more counts of depressive symptoms controlling for individual and neighborhood covariates (

coefficient=-1.233,

p < .001). The incidence rate ratios (IRR) was .291. Covariates such as being female (

p = .009), being married or partnered (

p < .001), years of education (

p < .001), and poverty rate (

p = .001) were also significant predictors, with those who were female, not married, less educated, and living in higher poverty Census tracts reporting more depressive symptoms. The percentage of older adults in the neighborhood was not significantly associated with depressive symptoms, suggesting that relative income, rather than neighborhood age composition, plays a more critical role in shaping mental health outcomes. Note that variance inflation factors (VIFs) were calculated for all predictors, and all values were between 1.06 and 1.82, indicating no evidence of multicollinearity.

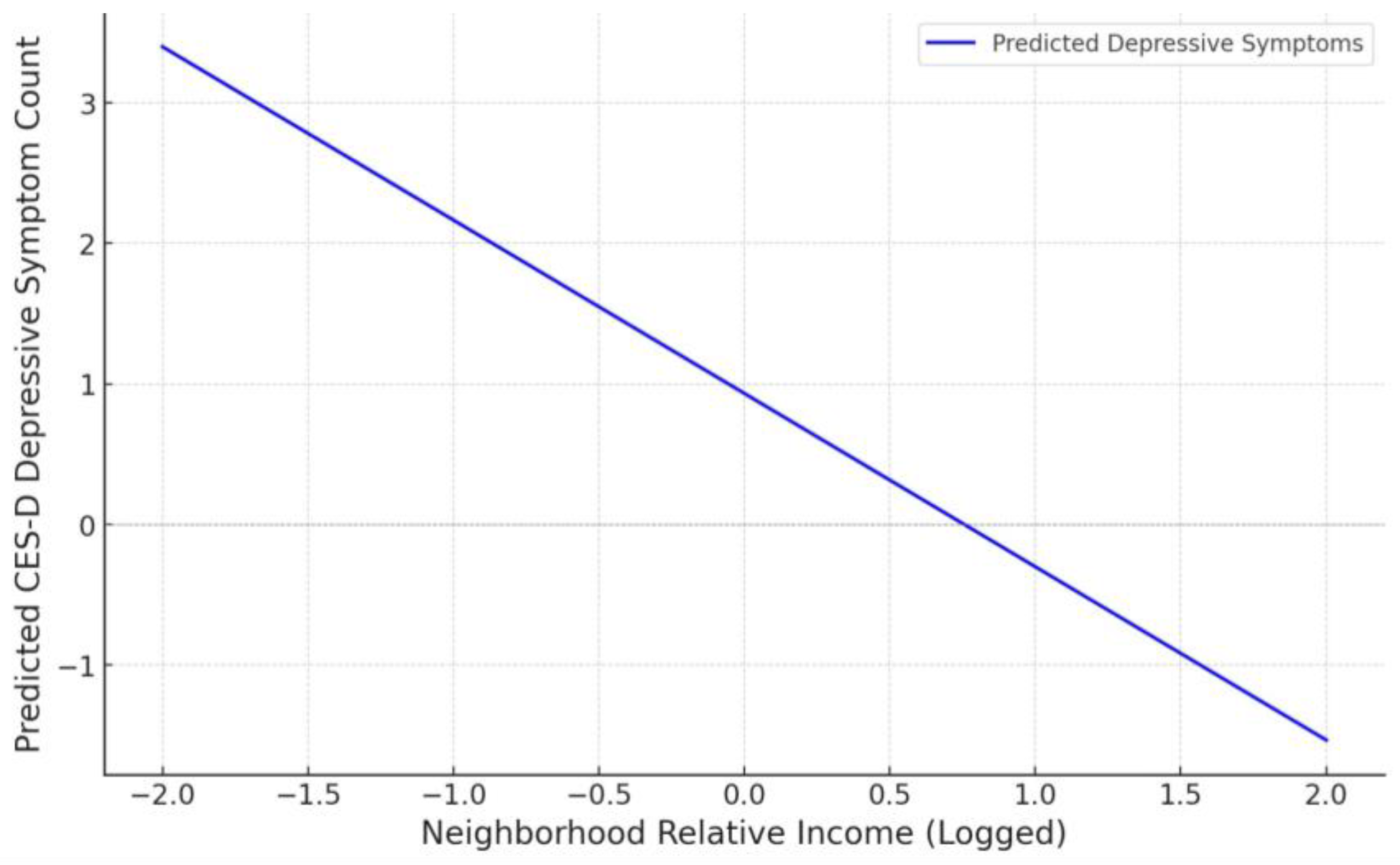

Lastly,

Figure 1 below shows the marginal effect as a graph, with the x-axis representing neighborhood relative income (logged) and the y-axis representing the predicted counts of depressive symptoms.

4. Discussion

The findings from this study offer significant insights into the relationship between neighborhood relative income and depressive symptoms in older adults. The results indicate that individuals who perceive themselves as economically disadvantaged relative to their neighbors are more likely to experience depressive symptoms. This aligns with the theoretical framework of relative deprivation, which suggests that individuals compare their socioeconomic status to those around them, leading to negative emotional outcomes when they perceive themselves as less affluent. These findings highlight the importance of addressing economic inequities within communities, as perceived economic inequality is not only a social determinant of mental health but also a potential driver of broader health inequities. Addressing such inequities can contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of how socioeconomic conditions shape mental health outcomes in later life.

The current study underscores the importance of examining relative income when assessing mental health outcomes. While absolute income matters, relative income—particularly within one’s immediate social context—may be a more salient predictor of mental health in later life. Neighborhood contexts play a pivotal role in determining the impacts of economic inequalities on residents’ well-being [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. The persistence of depressive symptoms in individuals with lower relative incomes suggests that targeted social interventions aimed at reducing perceived economic inequalities within neighborhoods could alleviate depressive symptoms among older populations.

4.1. Limitations

While the current study provides valuable contributions to the literature, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the ability to make causal inferences. Although the study identifies a significant relationship between neighborhood relative income and depressive symptoms, it cannot establish whether relative deprivation leads to depressive symptoms or if individuals with depressive symptoms are more likely to perceive themselves as economically deprived. Future longitudinal research should aim to disentangle the directionality of this relationship, potentially revealing causal pathways through which economic inequities affect mental health over time. Second, the operationalization of neighborhood relative income by calculating relative deprivation within Census tracts emphasizes social comparisons and aligns with relative deprivation theory. Although this approach effectively represents the socio-economic dimensions central to this study, alternative indices such as the Yitzhaki Index may offer complementary perspectives on economic inequities’ health impacts [

35]. Future research could explore combining these indices to enhance understanding of complex socio-economic influences on health. Third, while this operationalization of neighborhood relative income offers a standardized measure of deprivation, it may not capture all nuances of economic inequality within neighborhoods. Socioeconomic factors like wealth inequities and access to community resources may also shape depressive symptomatology [

36,

37]; however, these variables were not included in the current analysis. Future studies should incorporate these additional economic and social dimensions to provide a more holistic understanding of how complex forms of deprivation impact mental health outcomes, especially among diverse populations.

Fourth, although the study originally intended to use multilevel modeling with multiple respondents per Census tract, the distribution of participants was too sparse to support this approach. Specifically, the dataset included 3,386 individuals across 3,071 Census tracts, with an average of 1.34 respondents per tract (

SD=1.13,

Min=1,

Max=17), and approximately 84.83% of the tracts contained only one participant. Given that multilevel modeling typically requires at least 15 individuals per group [

38], the study adopted an alternative approach by randomly selecting one respondent per Census tract to create a single-level dataset (

N=3,071). This method helped mitigate potential biases arising from within-tract variation but limited the ability to account for hierarchical structures in the data. Fifth, while the study includes a robust set of covariates, the possibility of omitted variable bias remains. Covariates such as ethnicity, health status, and urban/rural classification, which were not included, could influence the findings. Future research should consider these variables to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationships examined. Nevertheless, the inclusion of key covariates, spanning both individual and neighborhood levels, significantly mitigates this risk, offering robust insights into the associations under study and enhancing confidence in the findings.

Finally, the use of self-reported data for depressive symptoms introduces the potential for response bias. Participants may underreport or overreport their symptoms based on social desirability or recall issues. Future research could benefit from integrating clinical assessments or biomarkers of mental health to validate self-reported measures, allowing for more precise and objective evaluations of depressive symptomatology. Combining self-reported data with clinical diagnostics could also offer a richer, multidimensional perspective on mental health among older adults.

4.2. Implications

Economic disadvantage is associated with depressive symptoms, especially for older adults. The findings of this study have important implications for both social policy and practice. First, social work interventions that target neighborhood inequalities could play a critical role in improving the mental health of older adults. By addressing both the perception and reality of economic inequities within communities, interventions could reduce feelings of relative deprivation and thus lower the incidence of depressive symptoms.

Policy efforts should also focus on improving the socioeconomic conditions in neighborhoods with high levels of deprivation. Investments in affordable housing, healthcare, and social services could reduce the stress associated with financial insecurity, especially for older adults living in economically diverse neighborhoods. Future research should continue to explore the pathways through which relative deprivation affects older adults’ depressive symptoms, particularly among vulnerable populations. Understanding these mechanisms could lead to more targeted and effective interventions, ultimately reducing the mental health burden associated with economic inequality.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of University of Michigan (#2016-021) and Texas Tech University (#2020-976) for obtaining a restricted-use data.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. We used anonymous information that is open to the public.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study (available upon request).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cho, S. Relationship between perceived neighborhood disorder and depressive symptomatology: The stress buffering effects of social support among older adults. Soc Work Public Health 2021, 37, 45–56. [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, J.; Brown, E.; Davis, M.; Pineda, M.; Kadolph, J.; Bell, H. Depression in older adults: A meta-synthesis. J Gerontol Soc Work 2013, 56, 509–534. [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S.; Sull, L.; Davis, C.; Worley, N. Correlates of depression among older Kurdish refugees. Soc Work 2011, 56, 159–168. [CrossRef]

- Rubin, A.; Parrish, D.E.; Miyawaki, C.E. Benchmarks for evaluating life review and reminiscence therapy in alleviating depression among older adults. Soc Work 2019, 64, 61–72. [CrossRef]

- Stouffer, S.A.; Suchman, E.A.; DeVinney, L.C.; Star, S.A.; Williams, R.M. The American Soldier: Adjustment During Army Life. Princeton University Press: Princeton, USA, 1949.

- Walker, I.; Pettigrew, T.F. Relative deprivation theory: An overview and conceptual critique. Br J Soc Psychol 1984, 23, 301–310. [CrossRef]

- Kelley-Moore, J.A.; Cagney, K.A.; Skarupski, K.A.; Everson-Rose, S.A.; Mendes de Leon, C.F. Do local social hierarchies matter for mental health? A study of neighborhood social status and depressive symptoms in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2016, 71, 369–377. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Carleton, R.N. Subjective relative deprivation is associated with poorer physical and mental health. Soc Sci Med 2015, 147, 144–149. [CrossRef]

- Beshai, S.; Mishra, S.; Meadows, T.J.; Parmar, P.; Huang, V. Minding the gap: Subjective relative deprivation and depressive symptoms. Soc Sci Med 2017, 173, 18–25. [CrossRef]

- Garratt, E.A.; Chandola, T.; Purdam, K.; Wood, A.M. The interactive role of income (material position) and income rank (psychosocial position) in psychological distress: A 9-year longitudinal study of 30,000 UK parents. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2016, 51, 1361–1372. [CrossRef]

- Gero, K.; Kondo, K.; Kondo, N.; Shirai, K.; Kawachi, I. Associations of relative deprivation and income rank with depressive symptoms among older adults in Japan. Soc Sci Med 2017, 189, 138–144. [CrossRef]

- Muramatsu, N. County-level income inequality and depression among older Americans. Health Serv Res 2003, 38, 1863–1884. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, R.; Pickett, K. The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger. Bloomsbury Press: London, UK, 2009.

- Crosby, F. A model of egoistical relative deprivation. Psychol Rev 1976, 83, 85–113.https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.83.2.85.

- Marmot, M.G. Status Syndrome: How Your Social Standing Directly Affects Your Health. Bloomsbury Press: London, UK, 2004.

- Marmot, M.G. The Health Gap: The Challenge of An Unequal World. Bloomsbury Press: London, UK, 2015.

- Wilkinson, R. Unhealthy Societies: The Afflictions of Inequality. Routledge: New York, USA, 1996.

- RAND Corporation. RAND HRS Longitudinal File (V2). RAND Corporation, Center for the Study of Aging. Available online: https://www.rand.org/well-being/social-and-behavioral-policy/portfolios/aging-longevity/dataprod/hrs-data.html (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- US Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2014-2018 5-Year Estimates. US Census Bureau. Available online: https://www.census.gov/history/www/programs/demographic/american_community_survey.html (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Health and Retirement Study. Cross-Wave Geographic Information (Detail). University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research. Available online: https://hrs.isr.umich.edu/data-products/restricted-data/available-products/9706 (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Radloff, L.S. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Psychol Meas 1977, 1, 385–401. [CrossRef]

- Karim, J.; Weisz, R.; Bibi, Z.; Rehman, S. Validation of the eight-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) among older adults. Curr Psychol 2015, 34, 681–692. [CrossRef]

- Bjornstrom, E.E. The neighborhood context of relative position, trust, and self-rated health. Soc Sci Med 2011, 73, 42–49. [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W.; Mulvey, E.P.; Shaw, E.C. Regression analyses of counts and rates: Poisson, overdispersed Poisson, and negative binomial models. Psychol Bull 1995, 118, 392–404. [CrossRef]

- Long, J.S. Regression Models for Categorical and Limited Dependent Variables. Sage: Washington, DC, USA, 1997.

- Aneshensel, C.S.; Wight, R.G.; Miller-Martinez, D.; Botticello, A.L.; Karlamangla, A.S.; Seeman, T.E. Urban neighborhoods and depressive symptoms among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2007, 62B, S52–S59. [CrossRef]

- Diez Roux, A.V.; Merkin, S.S.; Arnett, D.; Chambless, L.; Massing, M.; Nieto, F.J.; Sorlie, P.; Szklo, M.; Tyroler, H.A.; Watson, R.L. Neighborhood of residence and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2001, 345, 99–106. [CrossRef]

- Sampson, R.J. Great American City: Chicago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect. University of Chicago Press: Chicago, USA, 2012.

- Stockdale, S.E.; Wells, K.B.; Tang, L.; Belin, T.R.; Zhang, L.; Sherbourne, C.D. The importance of social context: Neighborhood stressors, stress-buffering mechanisms, and alcohol, drug, and mental health disorders. Soc Sci Med 2007, 65, 1867–1881. [CrossRef]

- Wight, R.G., Ko, M.J.; Aneshensel, C.S. Urban neighborhoods and depressive symptoms in late middle age. Res Aging 2011, 33, 28–50. [CrossRef]

- Hines, A.L.; Albert, M.A.; Blair, J.P.; Crews, D.C.; Cooper, L.A.; Long, D.L.; Carson, A.P. Neighborhood factors, individual stressors, and cardiovascular health among Black and White adults in the US: The reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke (REGARDS) study. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6, e2336207. [CrossRef]

- Zanasi, F.; De Santis, G.; Pirani, E. Lifelong disadvantage and late adulthood frailty. J Ageing Longev 2022, 2, 12–25. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Hessel, P.; Simon Thomas, J.; Beckfield, J. Inequality in place: Effects of exposure to neighborhood-level economic inequality on mortality. Demogr 2021, 58, 2041–2063. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Fang, Y. Income inequality, neighbourhood social capital and subjective well-being in China: Exploration of a moderating effect. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 6799. [CrossRef]

- Adjaye-Gbewonyo, K.; Kawachi, I. Use of the Yitzhaki Index as a test of relative deprivation for health outcomes: A review of recent literature. Soc Sci Med 2012, 75, 129-137. [CrossRef]

- Ran, G.; Zuo, C.; Liu, D. Negative wealth shocks and subsequent depressive symptoms and trajectories in middle-aged and older adults in the USA, England, China, and Mexico: a population-based, multinational, and longitudinal study. Psychol Med 2024, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Torres Sanchez, A.; Park, A.L.; Chu, W.; Letamendi, A.; Stanick, C.; Regan, J.; Perez, G.; Manners, D.; Oh, G.; Chorpita, B.F. Supporting the mental health needs of underserved communities: a qualitative study of barriers to accessing community resources. J Community Psychol 2022, 50, 541-552. [CrossRef]

- Bryk, A.S.; Raudenbush, S.W. Hierarchical Linear Models. Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1992.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).