I. Introduction

Dominion Energy Virginia delivers electricity to customers in Virginia and North Carolina. As both a generator owner and transmission owner, the company is legally required to develop an Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) to be reviewed by the respective State Corporation Commissions bi-annually. The IRP is a 15-year planning document with a 15-year planning horizon that uses current laws, technology, and cost assumptions to ensure both reliability and cost efficiency for customers in the future [

1]. It does not officially request any changes to the system, but it highlights a variety of futures regarding cost, resource adequacy, transmission reliability, and carbon emissions. The IRP introduces resources to be used in other filings, evaluates the retirement of existing resources, addresses current and possible future environmental regulations, and estimates cost for the multiple plans proposed.

The importance and scope of this document has changed dramatically over the years as conventional fossil-fuel-based generation is rapidly being retired and replaced by intermittent, renewable-based sources. Due to the sharp increase in forecasted loads, transmission systems are also facing possible limitations of their carrying capability due to thermal and voltage limit violations. To perform the resource adequacy analysis required by the IRP, one input must be the transmission network’s transfer capability. The ability to import or export power supports Dominion Energy’s load when internal generation resources are low. The system’s transfer capability needs to be measured and studied under different generation dispatch levels to determine resource adequacy and to assess system reliability. Measuring an area’s transfer capability means analyzing the system’s capacity to transfer power after various contingencies have been applied.

Both over- and under-estimation of transfer capability can have a negative impact on the system. Over-estimation can lead to loss of reliability during an event if the system cannot import or export the expected amount of power, causing load loss or other technical constraint violations. One reason for the major blackout in the Northeastern U.S. and Canada in August 2003 was over-estimation of transfer capability [

2]. On the other hand, under-estimation can prevent proper utilization of resources, leading to economic loss when utilities have additional power available that goes unsold. Moreover, with the increase in extreme weather events and their socioeconomic impact [

3], proper estimation of transfer capability under various scenarios is required. Thus, a proper and accurate assessment of the transfer capability needs to consider various contingencies.

Two of the criteria used to assess the transfer capability are first-contingency incremental transfer capability (FCITC) and first-contingency total transfer capability (FCTTC). As defined by North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), FCITC is the maximum incremental power that, given a set of initial conditions, can reliably be transferred from one area of an interconnected system to another without violating the N-1 contingency level. FCTTC refers to the total maximum power that can be transferred across areas under a given set of initial conditions and satisfying N-1 contingencies [

4].

Ongoing and recent studies and rulings at the federal levels further highlight the importance of transmission transfer capability.

NERC is conducting an Interregional Transfer Capability Study (ITCS) that will be released in 2025 [

5]. The study focuses on analyzing the ability to transfer power among the U.S.’s six regional entities.

The Department of Energy completed a National Transmission Needs Study in 2023 and identified transmission constraint corridors. [

6]

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission released Order 1920 on May 13, 2024, which addresses regional transmission policy. Its purpose is to increase the speed at which the transmission network can expand to bolster system reliability and support the connections of generation resources [

7].

There are different ways to measure a system’s transfer capability. AC-power-flow-based approaches consider non-linear power flow equations, such as repetitive power flow, continuation power flow and optimal power flow. But because of the large data sets that need to be analyzed, these methods face challenges with scalability and computational efficiency. They also might not be feasible in real scenarios that have a large number of contingencies [

2,

8].

For these reasons, utilities normally employ linear approximation methods for transfer limit studies [

9]; AC verification can be performed for the top mon/con pairs— a monitored electrical element and the applied contingency element—that limit the transfer capability. In the linear method, transfer capability is calculated based on a sensitivity metric called the “transfer distribution factor,” which will be described in Section II.

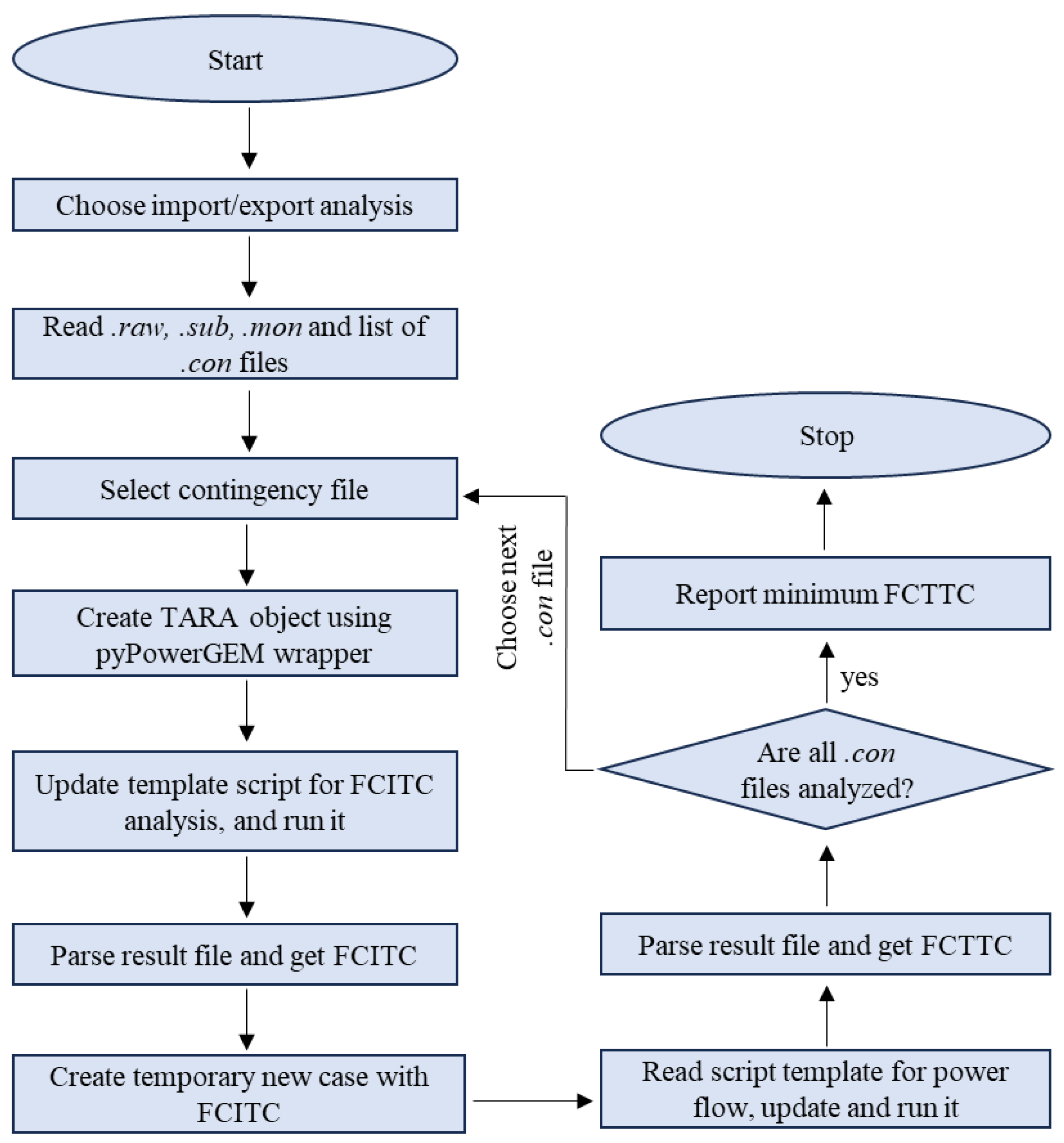

The linear approximation method that Dominion Energy uses is the proportional transfer limit by DC with AC verification. This function is available in TARA through the TARAViewer and is used to calculate the incremental transfer limit and total transfer capability for both import and export cases.

Using the TARAViewer is a time-intensive, manual process. First, the user has to calculate the FCITC, formulate an updated case using the data, and then run the power flow to obtain the total transfer capability. If there are separate files for different contingencies, each file is uploaded manually, a simulation is performed for each, and then the results are post-processed. Furthermore, in instances where the base case simulation might not provide the satisfied transfer capability (which could lead to under-utilization of resources), the system generation and load dispatch patterns would need to be iteratively readjusted.

To reduce the time and increase the ease of conducting transfer capability analyses, Dominion has developed a framework and an automation tool which can achieve an accurate and satisfied transfer limit capability in much less time. Instead of performing hundreds of manual steps, a user only has to run this automation tool twice, no matter how many contingency files are included. Processing time has decreased up to 90% and any possible errors caused by manually handling files have been eliminated. We also developed a Graphical User Interface (GUI) that can be used by anyone to conduct a transfer capability study, even a person with no background knowledge of the software.

This paper is organized as follows: Section II describes the transfer limit analysis based on DC with AC verification. Section III describes the software used to develop the automation toolset. Section IV describes the methodologies for the transfer limit study automation toolset which consists of a transfer capability automation tool (TRACT) and a transfer capability enhancement tool (TRACE). Section V presents the study’s results, followed by our conclusions and suggestions for future work in Section VI.

II. Transfer Limit Analysis

Transfer limit analysis measures a system’s capability to import or export power under various scenarios. This section describes a linear method we used for studying transfer limits where the thermal loading in the monitored elements was considered to help find the limit. MVAR flows were assumed to be negligible, the voltage was assumed to be 1 p.u., and DC power flow was used. In a linear assumption, changing the power flow in one element in the network causes a linear change in power flow in other elements of the network. The transfer distribution factor (TDF) of branch measures the impact of incremental transfer on it. The outage transfer distribution factor (OTDF) measures the impact that one element’s change in power has on other monitored elements for a given contingency; the TDF is calculated after the contingency is applied. Incremental power flow in the monitored branch due to incremental transfer is calculated by Equation (1).

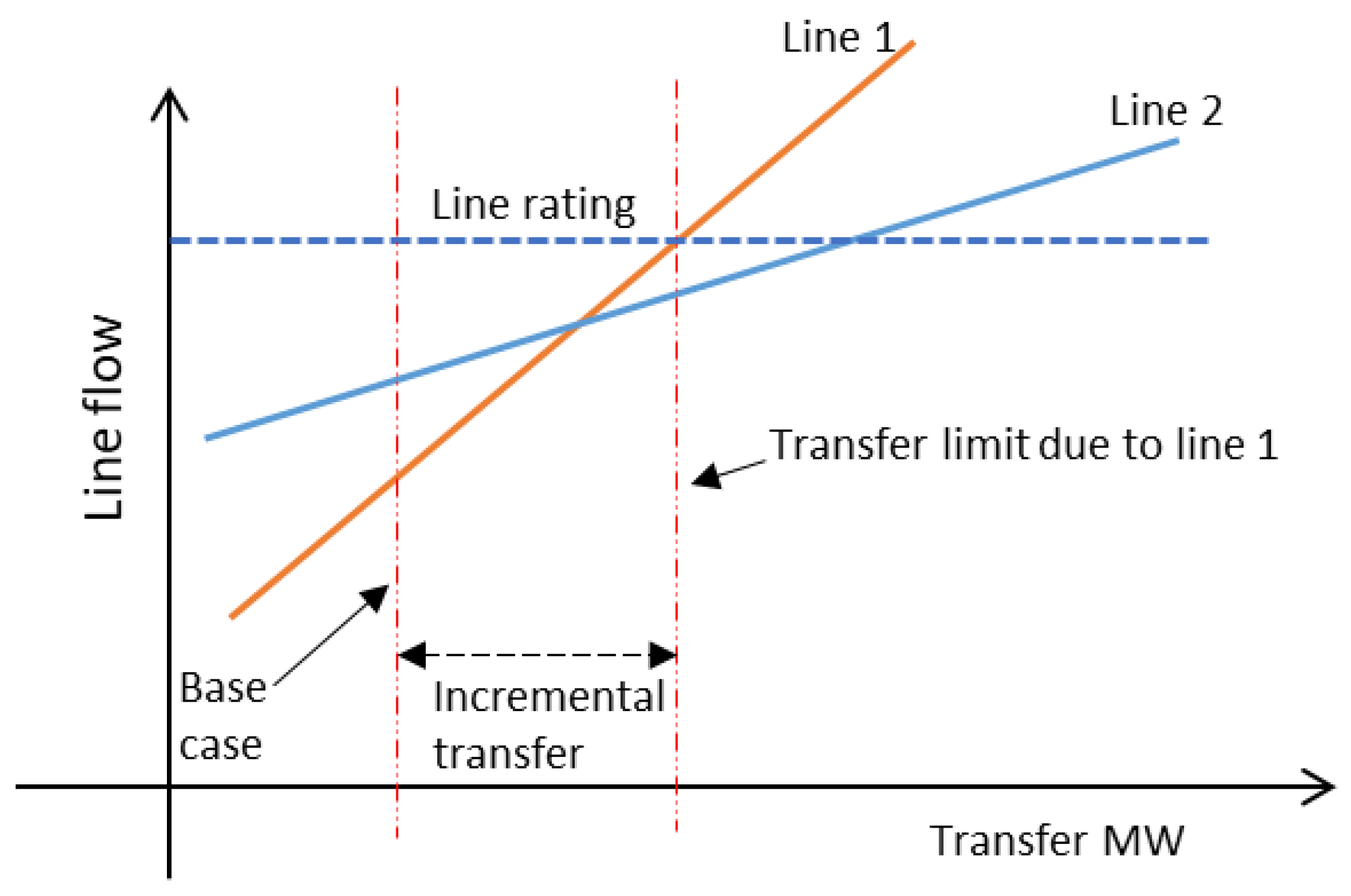

The incremental transfer limit of the monitored branch under a given contingency is calculated by Equation (2). See

Figure 1.

Once the transfer limit is found for all monitored branches under all contingencies, the lowest incremental transfer limit is chosen. For example, in

Figure 1, line 1 has a lower incremental transfer limit than line 2, so line 1’s incremental transfer limit would be taken. Linear analysis is used to find the top x worst case mon/con pair- a monitored electrical element and the applied contingency element—that limit the transfer capability. The AC power flow-based method can then be used for verification.

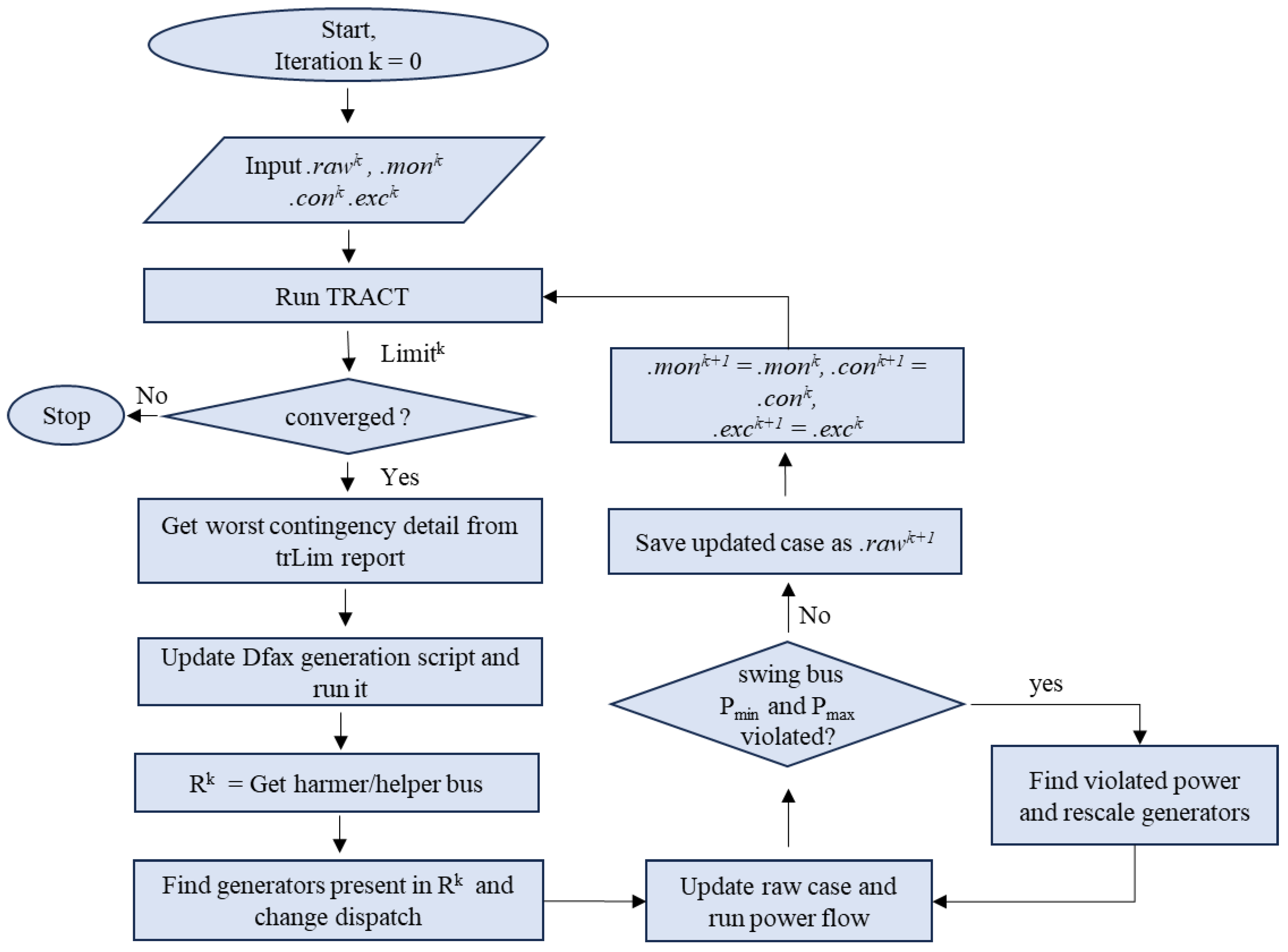

Generator distribution factor (DFAX) can also be used to indicate the change in power flow when generator output changes using mon/con pairs. If the DFAX is positive, flow in the monitored line increases as the generator output increases; this is known as a harmer generator because it increases the line’s load, thus decreasing its capacity to carry further. On the other hand, if the DFAX is negative, the flow in the line will decrease as the generator output increases; this is known as a helper generator.

III. Software

This section briefly summarizes the commercial software packages used to develop the automation toolset.

A. TARA

TARA (Transmission Adequacy and Reliability Assessment) by PowerGEM identifies and analyzes transmission bottlenecks. In this paper we will discuss some of TARA’s features that apply to transfer capability studies. TARA can perform linear, power flow-based transfer-limit analysis with AC verification. This provides the satisfied accuracy with less computational effort than a fully AC-based method, thus making it suitable for analyzing a large number of contingencies. The distribution factor cutoff can be specified to include only those mon/con pairs with a DFAX higher than the cutoff point. As we conducted our study, TARA’s Excel module recorded every operation we performed in ExcelViewer and generated a script, which we then used in the automation tool.

B. pyPowerGEM

This Python module developed by PowerGEM provides flexibility in running, analyzing and updating test cases, and develops automation. It includes many application programming interfaces (APIs). The pyTARA API functionalities include loading cases, solving them, and looping over elements, as well as modifying and saving updated cases. The wrapper API, another available module, can be used to run the automation script. Both pyTARA and wrapper APIs were used to develop the automation tool.

C. Python

Python is an open-source, high-level, interpreted, general-purpose dynamic programming language that is powerful, flexible, and easy to use. A large and active user community contributes to the development of many open-source packages that can be leveraged while writing a script. User-friendly data structures make it popular in various industries.

IV. Methodology

The first part of this section describes the approach used to create the Transfer Capability Automation Tool (TRACT) and the second part describes the Transfer Capability Enhancement Tool (TRACE). TRACT is used to assess the transfer capability of the system, while TRACE is used to improve transfer limits by re-dispatching the generators based on the helper/harmer bus.

C. Study Cases

Because Dominion Energy is a member of PJM, the Regional Transmission Organization, we performed our transfer analysis using two transmission study cases that they developed.

- (1)

The RTEP Model

PJM develops the Regional Transmission Expansion Plan (RTEP) model each year, in compliance with NERC standards. According to PJM Manual 14B [

9], the RTEP base case is developed in three periods: Summer, Winter and Light Load. Besides NERC criteria, the model also considers the regional planning criteria that drive the analysis, studies, and proposal windows. Specific results from PJM studies conducted throughout the year are summarized in the model, including baseline reliability, market efficiency, operational performance, transmission owner criteria analyses, and interregional studies. The goal is to identify necessary additions and improvements to the transmission system. The model is also used to ensure the reliable and efficient flow of electricity to the millions of people throughout PJM’s region. A comprehensive analysis of this model ensures that the transmission system upgrades and enhancements are integrated with generation and transmission projects to meet load-serving obligations.

Dominion Energy’s transmission planning team use all three periods of the RTEP model to perform transmission planning analyses so we can maintain transmission reliability, identify issues and provide solutions.

- (2)

The CETL Model

PJM uses a load-deliverability analysis to measures a system’s import capability under emergency peak load conditions called the Capacity Emergency Transfer Limit (CETL) case, it is a key metric used in PJM’s deliverability testing to ensure the reliability of the electrical grid. It measures the transfer limit, indicating the maximum amount of emergency power that can be reliably transferred from the remainder of PJM in the event of generation deficiency within the study area. To determine the CETL case transfer limit, imports into the study area were incrementally increased. The CETL model limit ensures that the transmission system can supply the necessary energy support during emergencies and helps verify that the import capability required to meet the reliability objective is sufficient.

Using TRACT, we produced results for all the above cases. Then we re-dispatched the non-dispatched base case using TRACE in order to enhance the transfer capability.

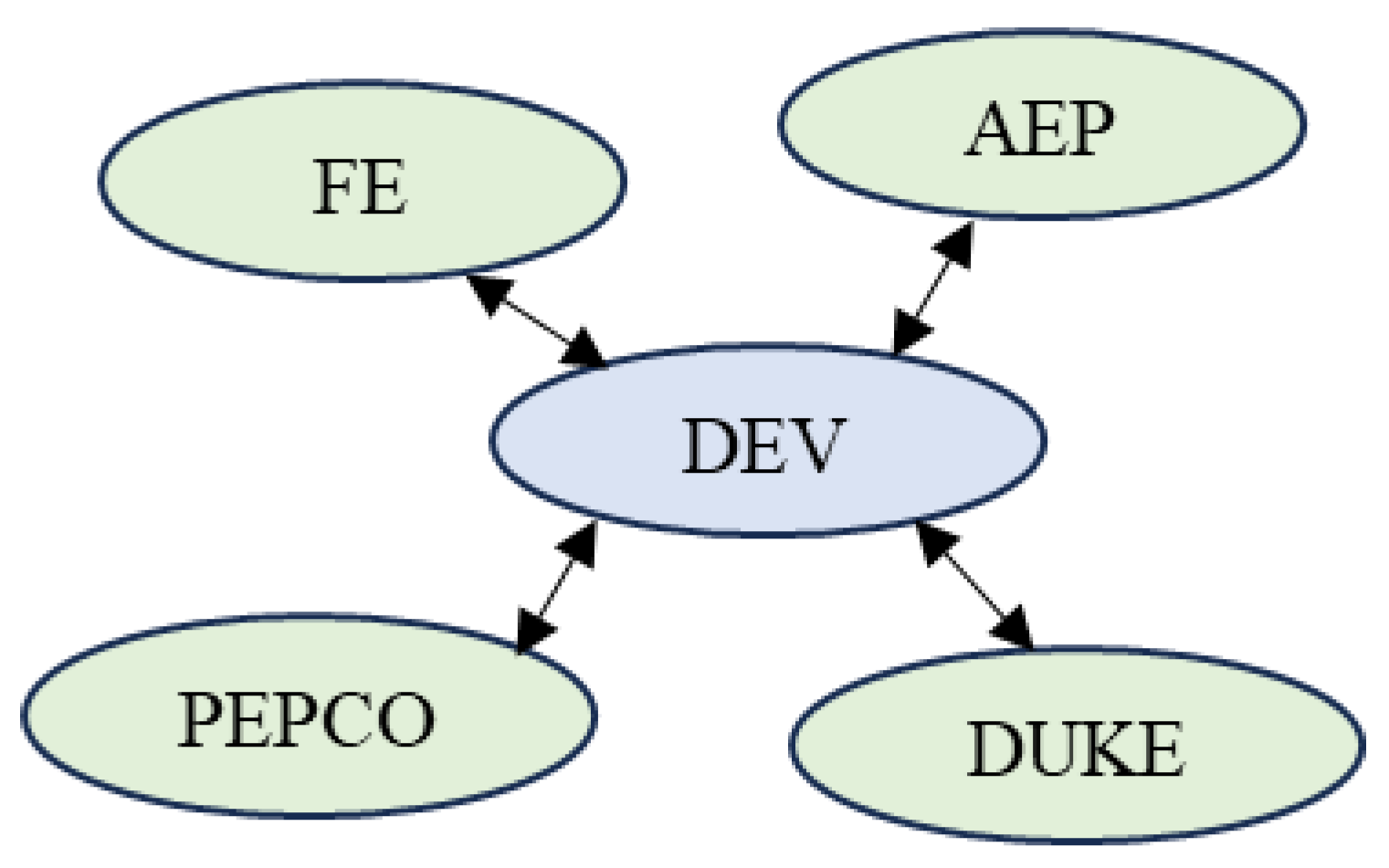

Because no utility stands alone, in our analysis we included four neighboring utilities within the Eastern Interconnection: PEPCO, Duke Energy, American Electric Power (AEP) and First Energy (FE) (see

Figure 4), where DEV is Dominion Energy.

When we studied the export transfer capability, TRACE became extremely valuable in determining the transmission limits. PJM’s RTEP cases were built to represent realistic conditions and, as a rule, Dominion Energy generally imports power. Although there are numerous real-time instances of Dominion Energy exporting power, there was not a planning model that could reflect that without significant modification. However, it was necessary for the study to know the export capability of the transmission network. It was apparent from the import transfer capability that our lines should be able to carry more power. By using TRACE to re-dispatch the units, we were able to determine more realistic export capabilities under contingencies.

V. Results

Our case results were obtained using TRACT and TRACE. For confidentiality reasons, in this paper we designated the interconnected utilities as A, B, C and D.

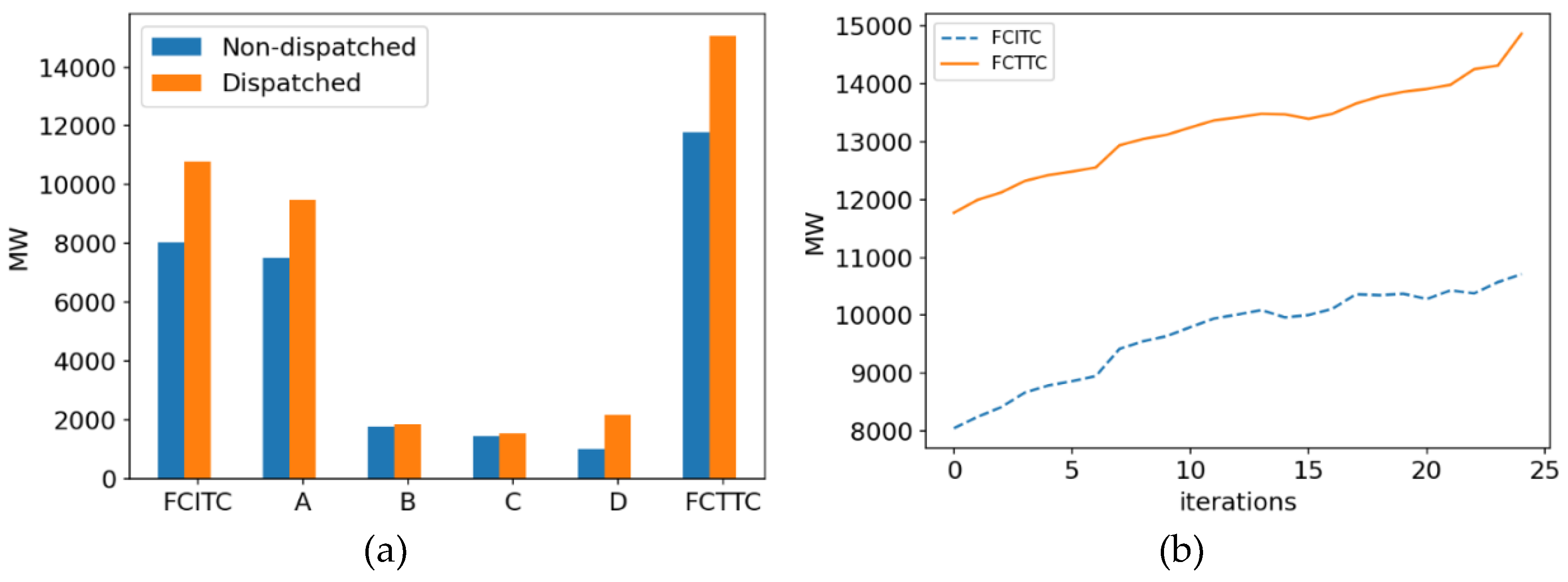

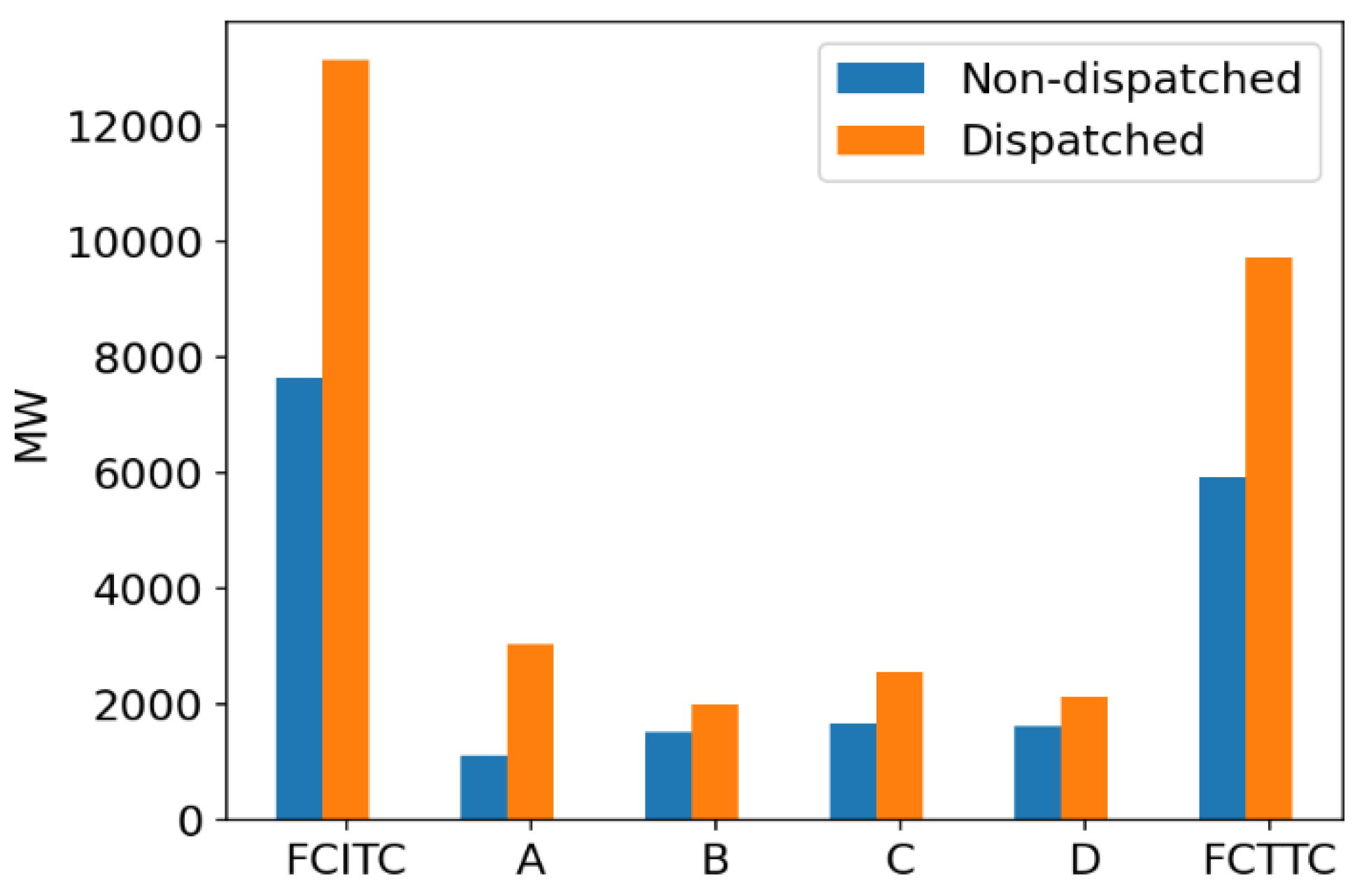

Figure 5(a) shows Dominion’s import capability using PJM’s 2023 series RTEP for the 2028 summer case. Here, “non-dispatched attribute” refers to the values obtained using the generation of the base case, while “dispatched attribute” refers to the values obtained after re-dispatching the case using TRACE.

Values corresponding to neighboring utilities A, B, C, and D showed the tie-line power flow from them to Dominion at the import transfer limit. Using the re-dispatching tool, FCITC increased from 8047 MW to 10227MW, thereby increasing the FCTTC from 11773 MW to 15092 MW— a 28.2% increase.

Figure 5(b) shows the increase in FCITC and FCTTC obtained by TRACE through re-dispatching. The values did not monotonically increase, but they did increase from the base case. After 24 iterations, the re-dispatched case did not converge, indicating that the maximum possible transfer limits were reached. For time comparison, a single manual iteration took an average of 18 minutes while an iteration in TRACE took 1 minute 45 seconds, a significant time savings of ~90%.

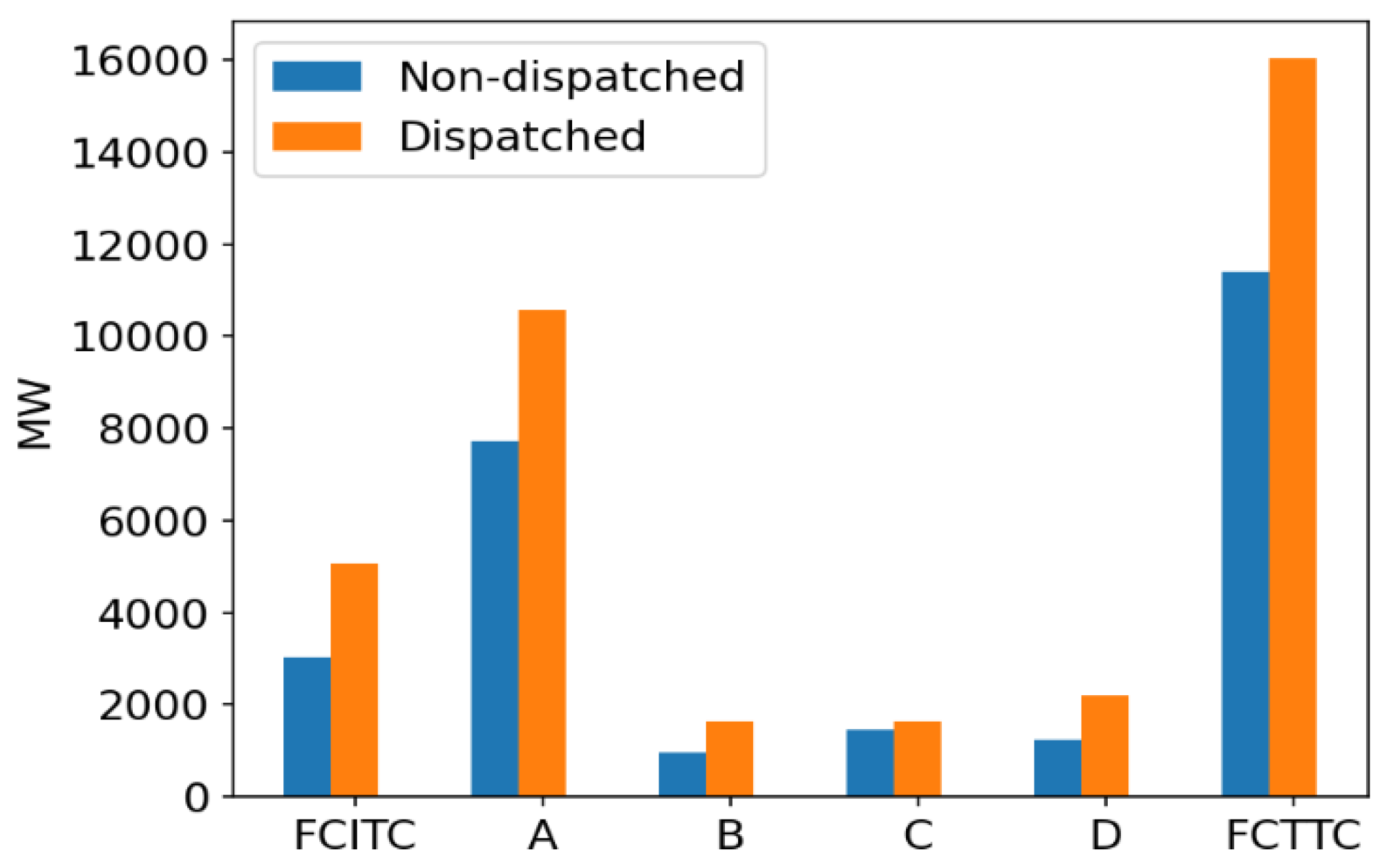

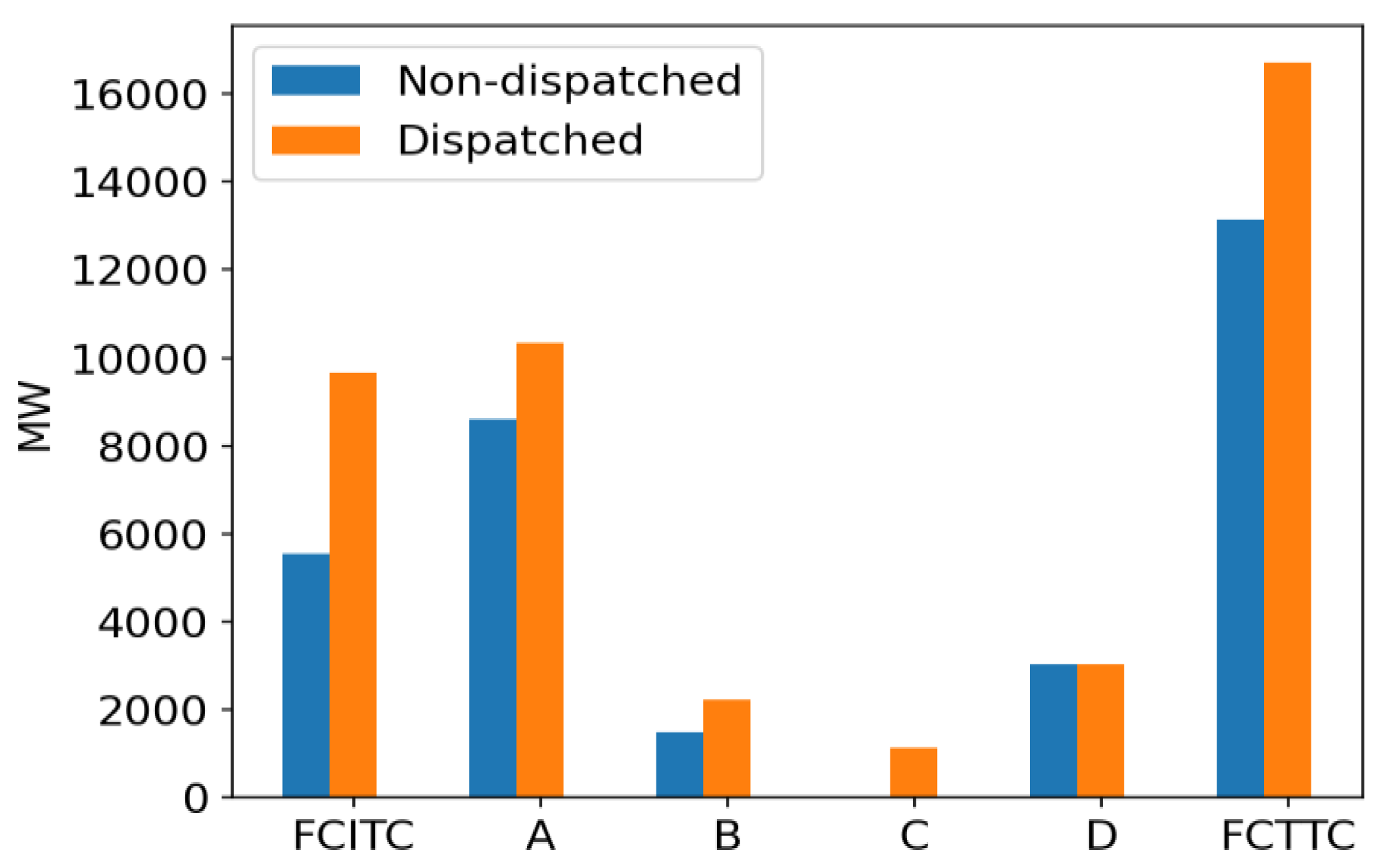

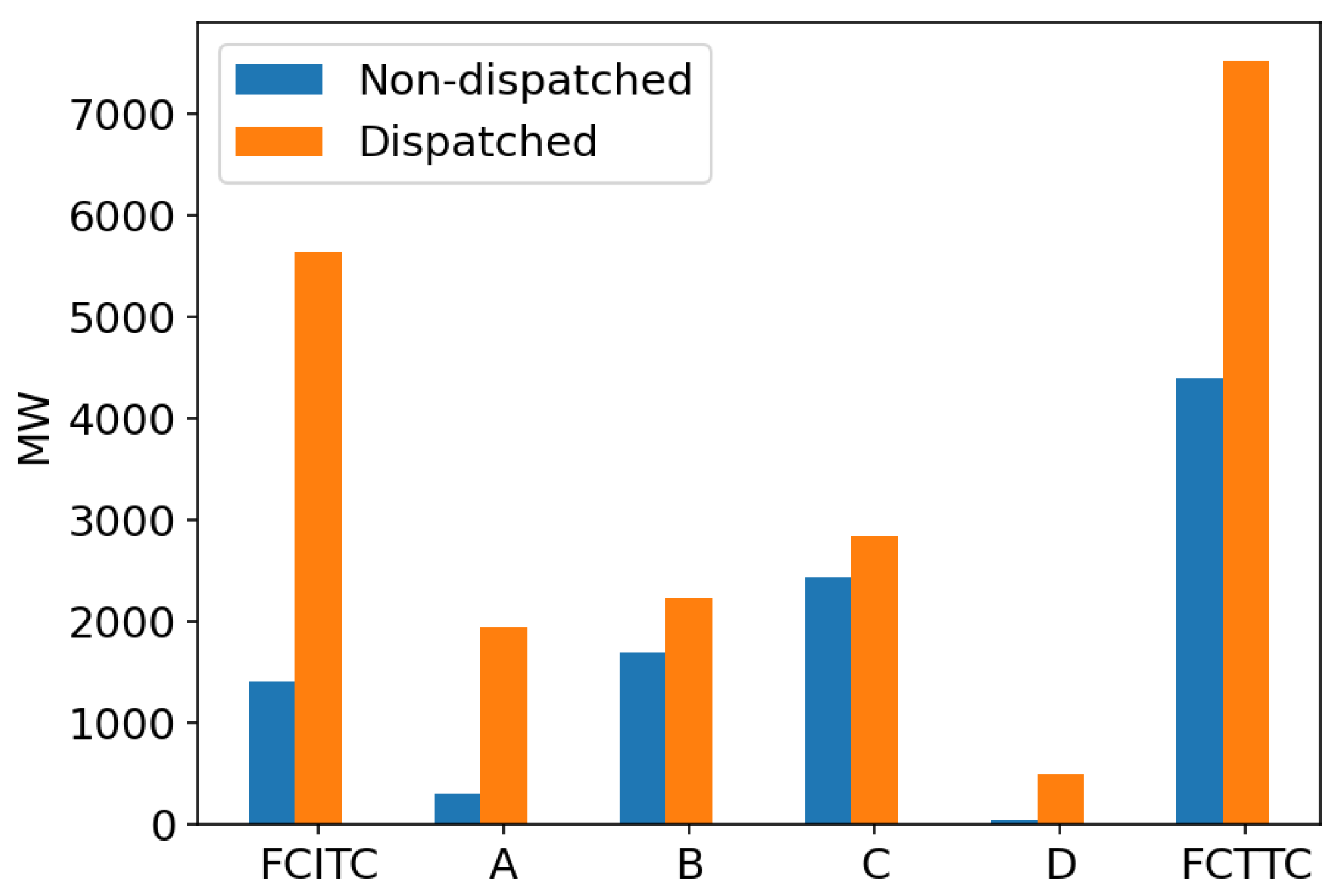

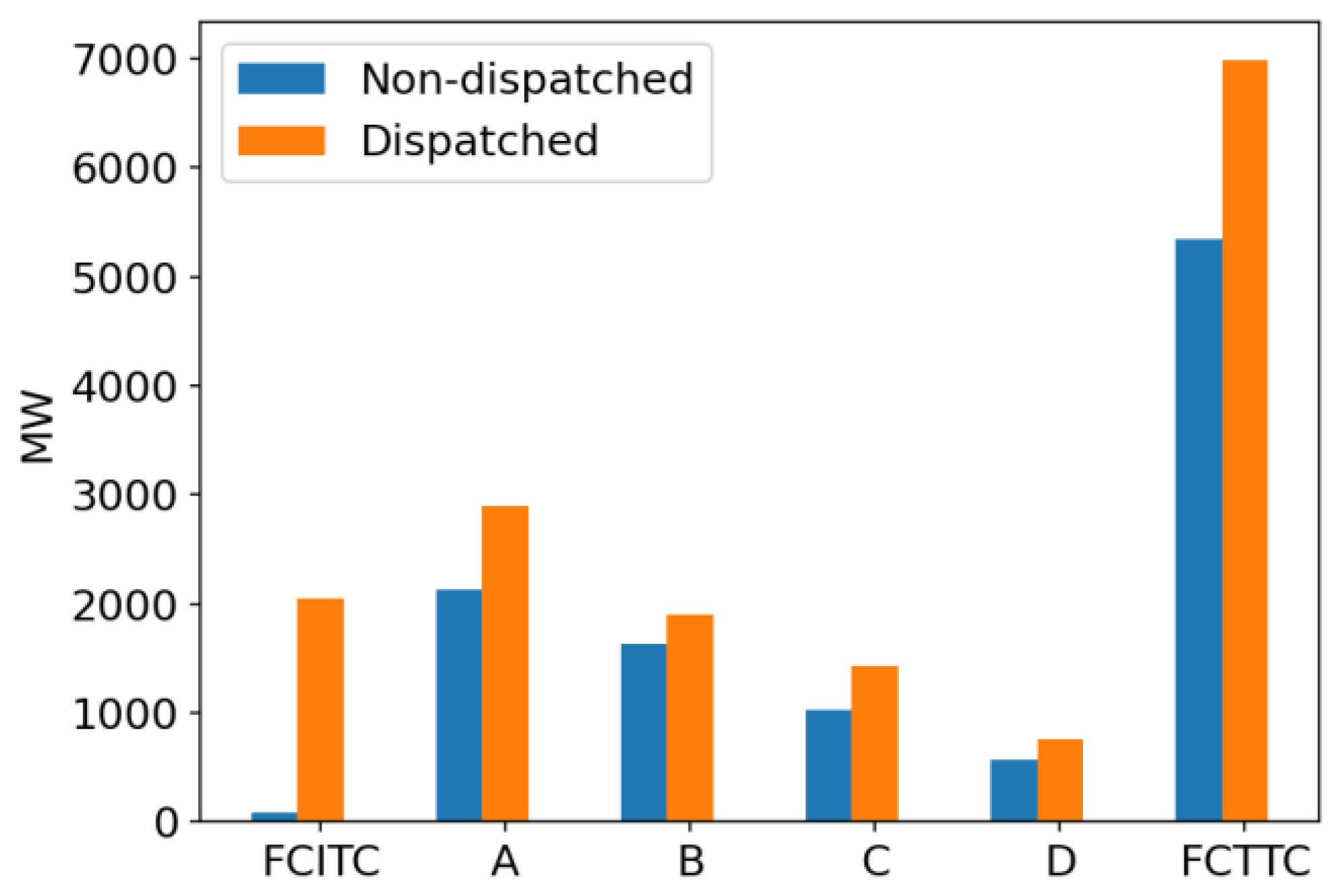

Similarly,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the import capability results for PJM’s 2023 series RTEP 2028 case for winter and light load condition respectively. The dispatched cases generally had higher import transfer limits than non-dispatched cases at each tie-line. In the winter case, total FCTTC increased by 40.6%, while in the light load case FCTTC increased by 27.4 %. The result shows that generation re-dispatch within Dominion Energy can have a big impact on its import capability with neighboring utilities.

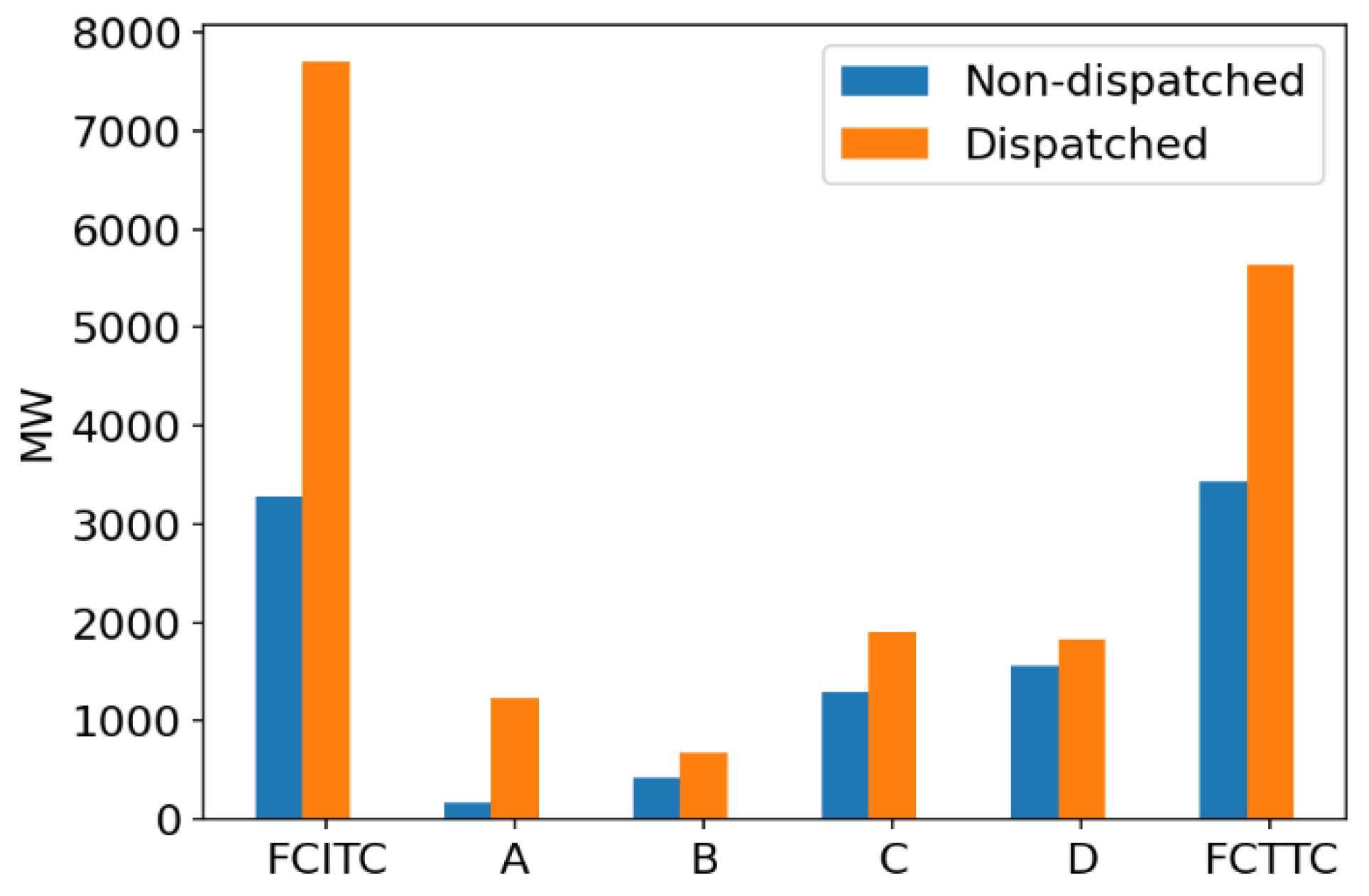

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 show Dominion’s export capability results for all three 2023 series RTEP 2028 cases. Dispatched cases generally had higher export transfer limits than non-dispatched cases. Total FCTTC transfer limits increased by 64% for the summer case, 63% for the winter case, and 69.3% for the light load condition.

Figure 11 shows the transfer limits result for the CETL case which assessed Dominion’s import capability during a peak load emergency condition. In the dispatched case, total transfer capability increased by 29.2%. The result shows that generation re-dispatch in the CETL case also had a big impact on import capability and TRACE helped find 30% more enhanced transfer capability compared to CETL base case.

VI. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper discussed an automation toolset developed to study the transfer capability of interconnected electric systems. Such studies help assess the reliability and resource adequacy of the grid; they are also an important component of the Integrated Resource Plan (IRP). Python and pyPowerGEM were used to develop both the TRACT tool that determines transfer capability and the TRACE tool that finds increased transfer limits through iterative re-dispatching. The tools were tested using a variety of real cases.

Using the toolset significantly reduced task time by ~90% compared to manual iteration. The automated process also has a minimal number of steps, unlike the manual process, which is complex, repetitive, and highly prone to human error. Another advantage is the GUI interface that allows users who are not TARA experts to run the calculations.

This toolset can have several robust applications in the future. For example, future work could include deploying this tool on servers, making it accessible to many more people with more powerful computing power. It allows the company to ask “what-if” questions with little burden on the engineers. With this tool, it may be possible to see how delays could impact the system across various years of construction and how changes in topology will impact the import capability over the years to come. The toolset can also be leveraged as a model to automate other TARA applications.

References

- “Meeting Future Energy Needs.” Dominion Energy, cdn-dominionenergy-prd-001.azureedge.net/-/media/pdfs/global/company/2023-va-integrated-resource-plan.pdf.

- Poudyal, A. , Lamichhane, S., Wertz, C., Mahmud, S.U., and Dubey, A., "Hurricane and Storm Surges-Induced Power System Vulnerabilities and their Socioeconomic Impact," 2024 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Seattle, WA, USA, 2024, pp. 1-5.

- Mohammed, Olatunji Obalowu, et al. "Available transfer capability calculation methods: A comprehensive review." International Transactions on Electrical Energy Systems 29.6 (2019): e2846.

- Rep, N. “Available transfer capability definitions and determinations,” North American Electric Reliability Council (NERC), 1996.

- Interregional Transfer Capability Study (ITCS). www.nerc.com/pa/RAPA/Pages/ITCS.aspx.

- National Transmission Needs Study. (n.d.). Energy.gov. https://www.energy.gov/gdo/national-transmission-needs-study.

- “News Releases and Headlines.” Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, Explainer on the Transmission Planning and Cost Allocation Final Rule | Federal Energy Regulatory Commission ferc.gov).

- Khairuddin, AB; Khalifa, OO; Alhammi, AI; Larik, RM. “Deterministic approach available transfer capability (ATC) calculation methods.

- Ejebe GC, Waight JG, Sanots-Nieto M, Tinney WF. Fast calculation of linear available transfer capability. IEEE Trans Power Syst. 2000, 15, 1112–1116. [CrossRef]

- “Region Transmission Planning Process”, PJM, https://www.pjm.com/-/media/documents/manuals/m14b.ashx.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).