Submitted:

05 December 2024

Posted:

06 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

3.2. General Knowledge of Vector-Borne Zoonoses

3.3. Promotion of Knowledge in the Field of Zoonoses by Veterinarians

3.4. Level of Concern on Vector-Borne Zoonoses

3.5. Global Warming in Portugal

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Howard, C.R.; Fletcher, N.F. Emerging virus diseases: Can we ever expect the unexpected? Emerg Microbes Infect 2012, 1, e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Vale, B.; Lopes, A.P.; Fontes, M.d.C.; Silvestre, M.; Cardoso, L.; Coelho, A.C. A Cross-Sectional Study of Knowledge on Ownership, Zoonoses and Practices among Pet Owners in Northern Portugal. Animals 2021, 11, 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPMA, Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera, 2022. IPMA – Mapas. Available online: https://www.ipma.pt/pt/oclima/monitorizacao/. (accessed on 14 January 2024).

- Schröter, D.; Cramer, W.; Leemans, R.; Prentice, I.C.; Araújo, M.B.; Arnell, N.W.; Bondeau, A.; Bugmann, H.; Carter, T.R.; Gracia, C.A.; de la Vega-Leinert, A.C.; Erhard, M.; Ewert, F.; Glendining, M.; House, J.I.; Kankaanpää, S.; Klein, R.J.T.; Lavorel, S.; Lindner, M.; Metzger, M.J.; Meyer, J.; Mitchell, T.D.; Reginster, I.; Rounsevell, M.; Sabaté, S.; Sitch, S.; Smith, B.; Smith, J.; Smith, P.; Sykes, M.T.; Thonicke, K.; Thuiller, W.; Tuck, G.; Zaehle, S.; Zierl, B. Ecosystem service supply and vulnerability to global change in Europe. Science 2005, 310, 1333–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giorgi, F.; Lionello, P. Climate change projections for the Mediterranean region. Glob Planet Change 2008, 63, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.; Qin, D.; Manning, M.; Chen, Z.; Marquis, M., Averyt, K.B., Tignor, M.; Miller, H.L., Eds. AR4 Climate change 2007: The physical science basis – Report. In Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, USA, 2007.

- Chalghaf, B.; Chemkhi, J.; Mayala, B.; Harrabi, M.; Benie, G.B.; Michael, E.; Ben Salah, A. ; Ecological niche modeling predicting the potential distribution of Leishmania vectors in the Mediterranean basin: Impact of climate change. Parasites Vectors 2018, 11, 461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleussner, C.-F.; Menke, I.; Theokritoff, E.; van Maanen, N.; Lanson, A. Climate impacts in Portugal. Climate analytics. 2019. Available online: https://youth4climatejustice.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Climate-Analytics-Climate-Impacts-in-Portugal-min.pdf. (accessed on 23 October 2023).

- WWF, 2019. The Mediterranean burns—WWF’s Mediterranean proposal for the prevention of rural fires. World Wildlife Fund. Available online: https://www.wwf.es/?51162/The-Mediterranean-burns-2019. (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Turco, M.; Jerez, S.; Augusto, S.; Tarín-Carrasco, P.; Ratola, N.; Jiménez-Guerrero, P.; Trigo, R.M. Climate drivers of the 2017 devastating fires in Portugal. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 13886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parente, J.; Pereira, M.G.; Amraoui, M.; Fischer, E.M. Heat waves in Portugal: Current regime, changes in future climate and impacts on extreme wildfires. Sci Total Environ 2018, 631–632, 534–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenza, J.C.; Menne, B. Climate change and infectious diseases in Europe. Lancet Infect Dis 2009, 9, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. A global brief on vector-borne diseases (WHO/DCO/WHD/2014.1). World Health Organization 2014. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/111008 (accessed on day month year).

- Semenza, J.C.; Suk, J.E. Vector-borne diseases and climate change: A European perspective. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2018, 365, fnx244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chala, B.; Hamde, F. Emerging and re-emerging vector-borne infectious diseases and the challenges for control: A review. Front Public Health 2021, 9, 715759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, A.; Kamel, M. Climatic changes and their role in emergence and re-emergence of diseases. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2020, 27, 22336–22352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajian-Tilaki, K. Sample size estimation in epidemiologic studies. Casp J Intern Med 2011, 2, 289–298. [Google Scholar]

- Semenza, J.C.; Paz, S. Climate change and infectious disease in Europe: Impact, projection and adaptation. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2021, 9, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocklöv, J.; Dubrow, R. Climate change: an enduring challenge for vector-borne disease prevention and control. Nat Immunol 2020, 21, 479–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rupasinghe, R.; Chomel, B.B.; Martínez-López, B. Climate change and zoonoses: A review of the current status, knowledge gaps, and future trends. Acta Trop 2022, 226, 106225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paz, S. Climate change impacts on vector-borne diseases in Europe: Risks, predictions and actions. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2020, 1, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adepoju, O.A.; Afinowi, O.A.; Tauheed, A.M.; Danazumi, A.U.; Dibba, L.B.S.; Balogun, J.B.; Flore, G.; Saidu, U.; Ibrahim, B.; Balogun, O.O.; Balogun, E.O. Multisectoral perspectives on global warming and vector-borne diseases: a focus on southern europe. Curr Trop Med Rep 2023, 10, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, G.S.; Linares, C.; Ayuso, A.; Kendrovski, V.; Boeckmann, M.; Diaz, J. Heat-health action plans in Europe: Challenges ahead and how to tackle them. Environ Res 2019, 176, 108548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EEA, 2017. Climate change, impacts and vulnerability in Europe 2016. European Environment Agency [Publication]. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/climate-change-impacts-and-vulnerability-2016. (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- EEA, 2020. Trends and projections in Europe 2020. European Environment Agency [Publication]. Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/trends-and-projections-in-europe-2020. (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Maia, C.; Altet, L.; Serrano, L.; Cristóvão, J.M.; Tabar, M.D.; Francino, O.; Cardoso, L.; Campino, L.; Roura, X. Molecular detection of Leishmania infantum, filariae and Wolbachia spp. in dogs from southern Portugal. Parasites Vectors 2016, 9, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateus, T.L.; Moreira, S.; Maia, R.L. Unawareness about vector-borne diseases among citizens as a health risk consequence of climate change—A case study on leishmaniosis in northwest Portugal. In Climate Change and Health Hazards; Leal Filho, W., Vidal, D.G., Eds.; Springer Cham: Switzerland, 2023; pp. 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacConnachie, K.; Tishkowski, K. Boutonneuse Fever. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing: Florida, USA, 2023.

- Karim, S.; Kumar, D.; Budachetri, K. Recent advances in understanding tick and rickettsiae interactions. Parasite Immunol 2021, 43, e12830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talapko, J.; Škrlec, I.; Alebić, T.; Jukić, M.; Včev, A. Malaria: The past and the present. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunda, R.; Chimbari, M.J.; Shamu, S.; Sartorius, B.; Mukaratirwa, S. Malaria incidence trends and their association with climatic variables in rural Gwanda, Zimbabwe, 2005–2015. Malar J 2017, 16, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssempiira, J.; Kissa, J.; Nambuusi, B.; Mukooyo, E.; Opigo, J.; Makumbi, F.; Kasasa, S.; Vounatsou, P. Interactions between climatic changes and intervention effects on malaria spatio-temporal dynamics in Uganda. Parasite Epidemiol Control 2018, 3, e00070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO, 2015. West Nile virus – Portugal. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/17-september-2015-wnv-en. (accessed on 15 June 2024).

- ECDC, 2023. Epidemiological update: West Nile virus transmission season in Europe, 2022. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/epidemiological-update-west-nile-virus-transmission-season-europe-2022 (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Tilston, N.; Skelly, C.; Weinstein, P. Pan-European Chikungunya surveillance: Designing risk stratified surveillance zones. Int J Health Geogr 2009, 8, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO, 2022. Chikungunya fact sheet. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chikungunya. (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- Tham, H.-W.; Balasubramaniam, V.; Ooi, M.K.; Chew, M.-F. Viral determinants and vector competence of Zika virus transmission. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, O.J.; Gething, P.W.; Bhatt, S.; Messina, J.P.; Brownstein, J.S.; Hoen, A.G.; Moyes, C.L.; Farlow, A.W.; Scott, T.W.; Hay, S.I. Refining the global spatial limits of dengue virus transmission by evidence-based consensus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2012, 6, e1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO, 2023. Dengue and severe dengue. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue. (accessed on 2 November 2023).

| Variable | n (%) | |

| Age (years) | 18-29 | 93 (63.3) |

| 30-50 | 19 (12.9) | |

| >50 | 35 (23.8) | |

| Gender | Female | 108 (73.5) |

| Male | 39 (26.5) | |

| Region | North | 130 (88.4) |

| Centre | 13 (8.8) | |

| South | 4 (2.7) | |

| Education | 2nd cycle of Basic Education | 1 (0.7) |

| 3rd cycle of Basic Education | 2 (1.4) | |

| Secondary school | 17 (11.6) | |

| Degree | 82 (55.8) | |

| Master’s degree | 44 (29.9) | |

| Doctorate | 1 (0.7) |

| Questions and answer options | n(%) | |

| Do you know what a vector is? | Yes | 120 (81.6) |

| No | 27 (18.4) | |

| Can a vector transmit viruses? | Yes | 118 (80.3) |

| No | 0 (0.0) | |

| I don’t know | 29 (19.7) | |

| Is a mosquito a vector? | Yes | 123 (83.7) |

| No | 0 (0.0) | |

| I don’t know | 24 (16.3) | |

| Is leishmaniasis a vector-borne zoonosis? | Yes | 96 (65.3) |

| No | 4 (2.7) | |

| I don’t know | 47 (32.0) | |

| Is West Nile virus present in Portugal? | Yes | 20 (13.6) |

| No | 23 (15.6) | |

| I don’t know | 104 (70.7) | |

| Questions and answer options | n (%) | |

| Has your pet's veterinarian enlightened you about vector-borne zoonoses (e.g. transmitted by ticks, fleas, etc.)? | Yes | 92 (62.6) |

| No/ I do not know/I do not remember/I am not sure/Not applicable | 55 (37.4) | |

| Has the veterinarian informed you about existing preventive measures or treatments that combat vector-borne zoonoses? | Yes | 89 (60.5) |

| No/ I do not know/I do not remember/I am not sure/Not applicable | 58 (39.5) | |

| Do you think that veterinarians should provide more information about the transmission of zoonoses by vectors? | Yes | 137 (93.2) |

| No | 10 (6.8) | |

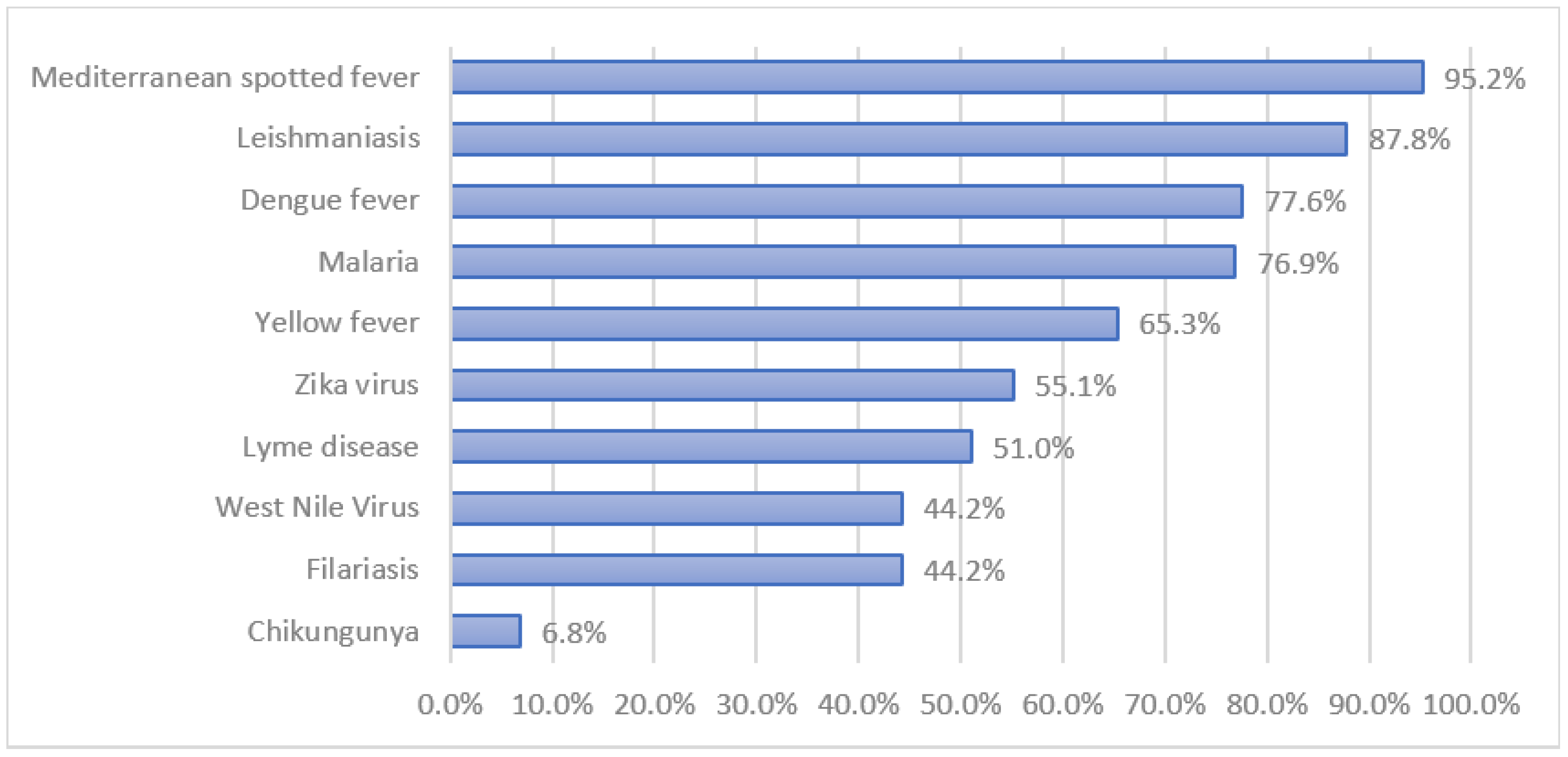

| Level of concern | 1 - Extremely Irrelevant (n; %) |

2 - Irrelevant (n; %) |

3 - Neutral (n; %) |

4 - Worrying (n; %) |

5 - Very Concerning (n; %) |

Don’t know / Never heard of (n; %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leishmaniasis | 5 (3.4) | 5 (3.4) | 19 (12.9) | 53 (36.1) | 59 (40.1) | 6 (4.1) |

| West Nile virus | 8 (5.4) | 8 (5.4) | 31 (21.1) | 25 (17.0) | 26 (17.7) | 49 (33.3) |

| Lyme disease | 9 (6.1) | 6 (4.1) | 23 (15.6) | 36 (24.5) | 34 (23.1) | 39 (26.5) |

| Malaria | 10 (6.8) | 2 (1.4) | 21 (14.3) | 40 (27.2) | 69 (46.9) | 5 (3.4) |

| ilariasis | 6 (4.1) | 7 (4.8) | 22 (15.0) | 39 (26.5) | 28 (19.0) | 45 (30.6) |

| Yellow fever | 7 (4.8) | 3 (2.0) | 29 (19.7) | 39 (26.5) | 51 (34.7) | 18 (12.2) |

| Dengue fever | 9 (6.1) | 3 (2.0) | 29 (19.7) | 33 (22.4) | 62 (42.2) | 11 (7.5) |

| Zika virus | 8 (5.4) | 7 (4.8) | 27 (18.4) | 35 (23.8) | 46 (31.3) | 24 (16.3) |

| Chikungunya | 9 (6.1) | 6 (4.1) | 26 (17.7) | 17 (11.6) | 9 (6.1) | 80 (54.4) |

| Mediterranean spotted fever | 5 (3.4) | 3 (2.0) | 17 (11.6) | 55 (37.4) | 62 (42.2) | 5 (3.4) |

| Questions and answer options | n(%) | |

| Do you take any preventative measures against vectors for your pet during the warmer months of the year? | Yes | 62 (42.2) |

| No | 50 (34.0) | |

| I don’t know | 35 (23.8) | |

| In recent years, have you noticed significant changes in Portugal regarding the prevalence of vectors (e.g. ticks, fleas, etc.) in the warmer months? | Yes | 85 (57.8) |

| No | 62 (42.2) | |

| Despite global warming being widely covered in the media, do you personally feel that the temperatures in the warmer months are getting higher and higher every year? | Yes | 136 (92.5) |

| No | 11 (7.5) | |

| Many vector-borne zoonoses can arise due to rising environmental temperatures. Do you think that Portugal is already or could be affected by this problem in the next 10 years? | Yes | 142 (96.6) |

| No | 5 (3.4) | |

| Did you know that the rise in the planet's temperature will lead to an increase in the frequency of vector-borne zoonoses? | Yes | 118 (80.3) |

| No | 29 (19.7) | |

| Do you think that this issue of the emergence of vector-borne zoonoses is addressed by the media in Portugal? | Yes | 24 (16.3) |

| No | 123 (83.7) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).