Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

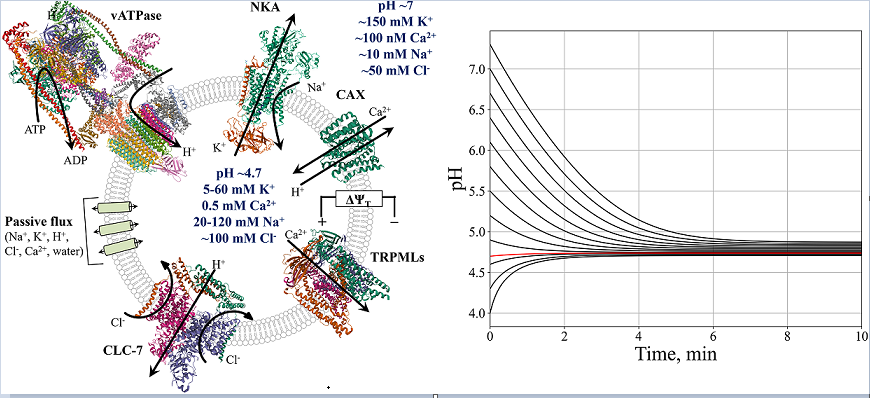

2.1. Model description

2.2. Model stability

2.3. Model software

3. Results

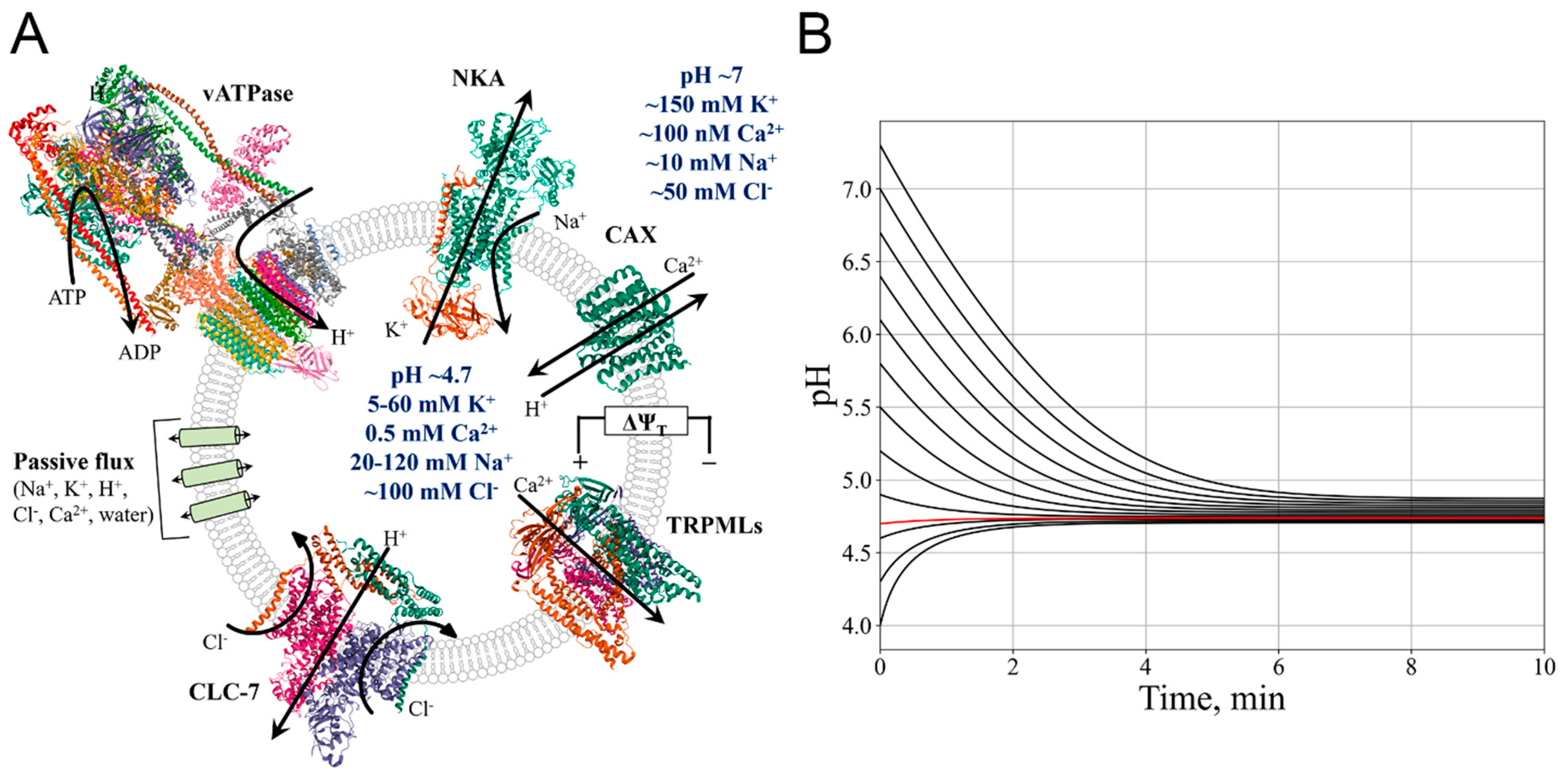

3.1. Endosome/Lysosome maturation

3.2. Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization (LMP)

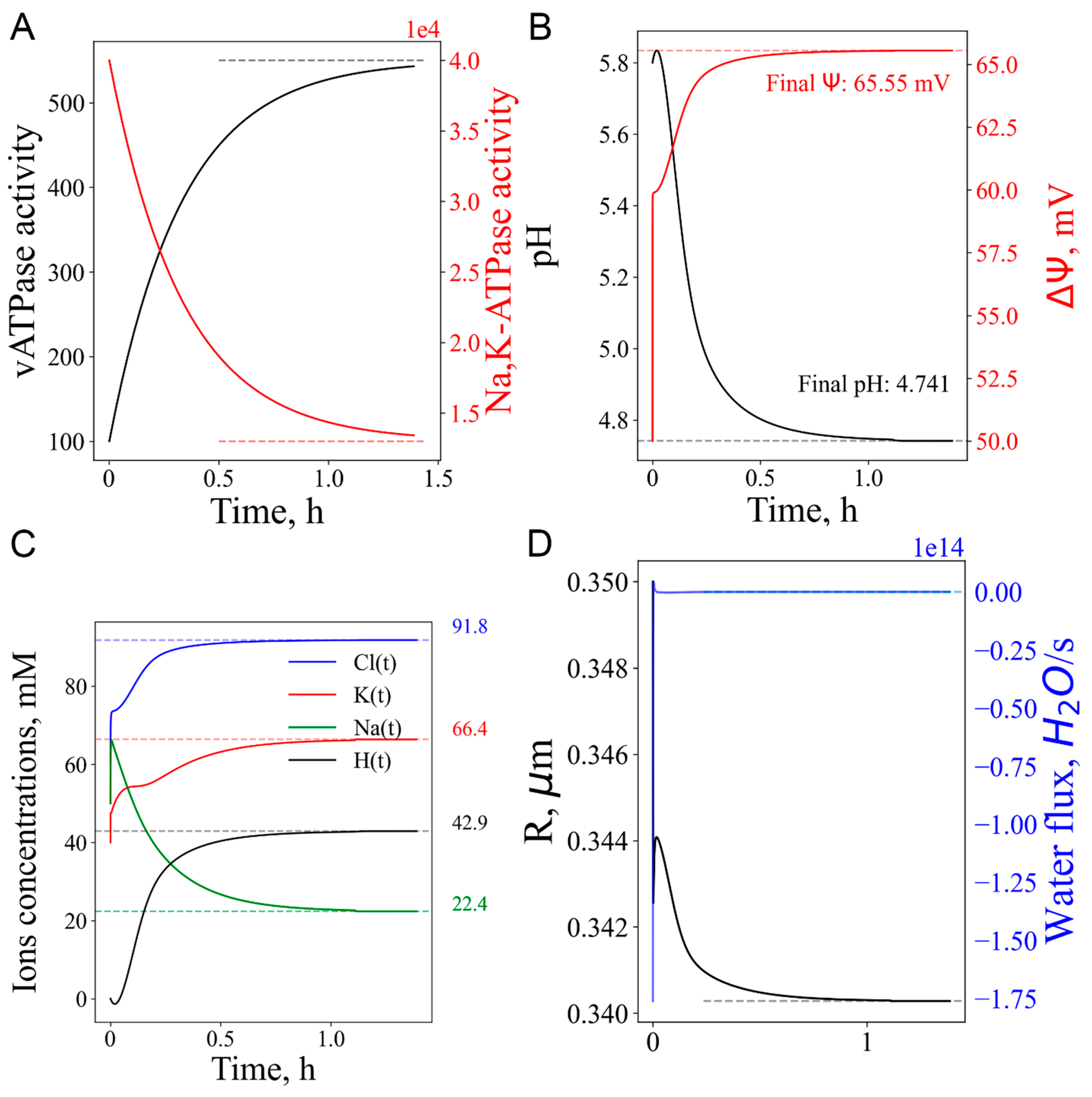

3.3. Short-term vATPase “knockout” or lysosome enlargement stresses

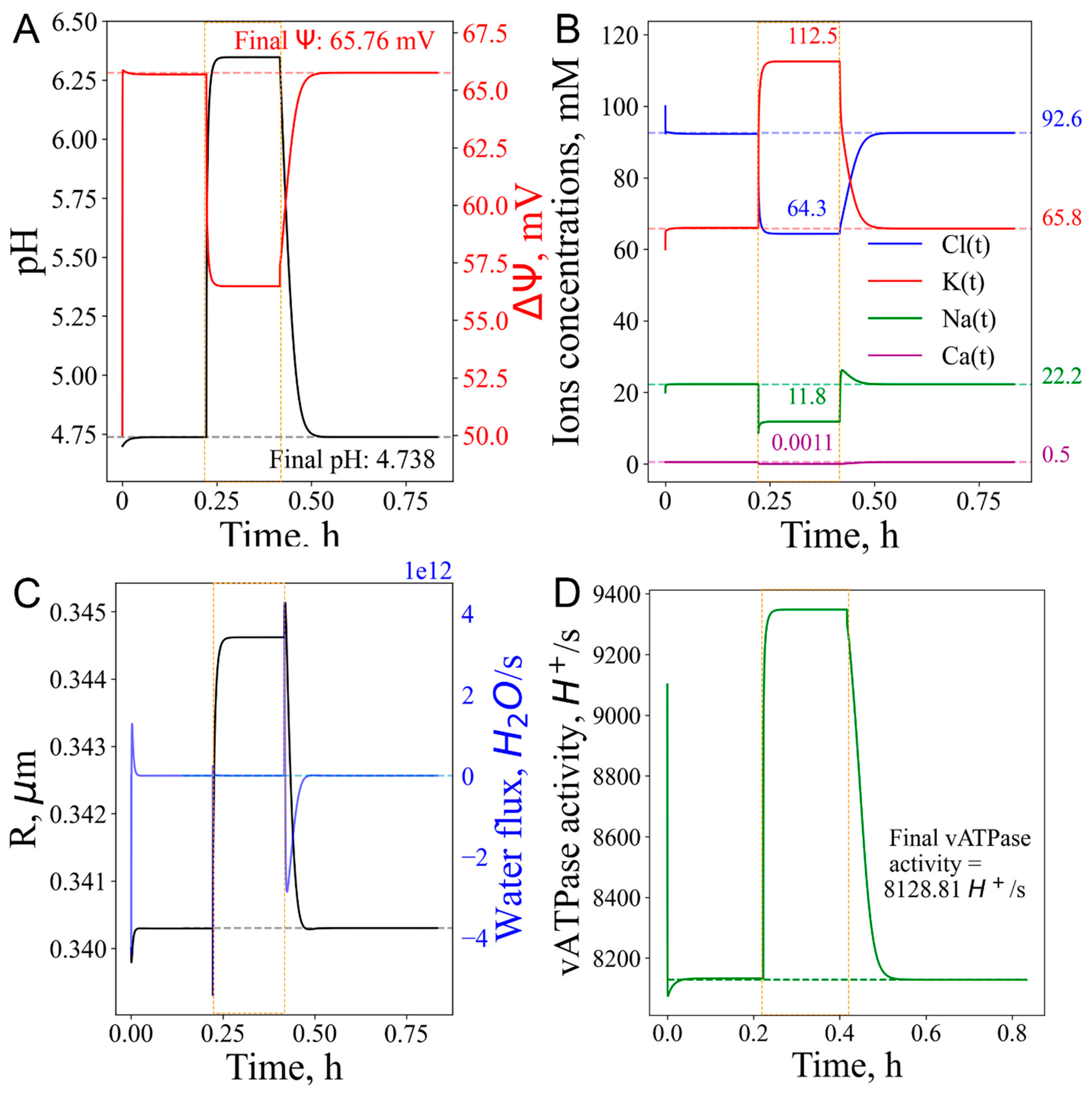

3.4. Calcium efflux as response to pH increase: deacidification, even without vATPase inactivation, could lead to calcium release from lysosomes

3.5. Cationic amphiphilic drugs (CAD) as a model for lysosomal storage disease (LSD) and hypotonic stress

3.6. Lysosome under mixed stress conditions

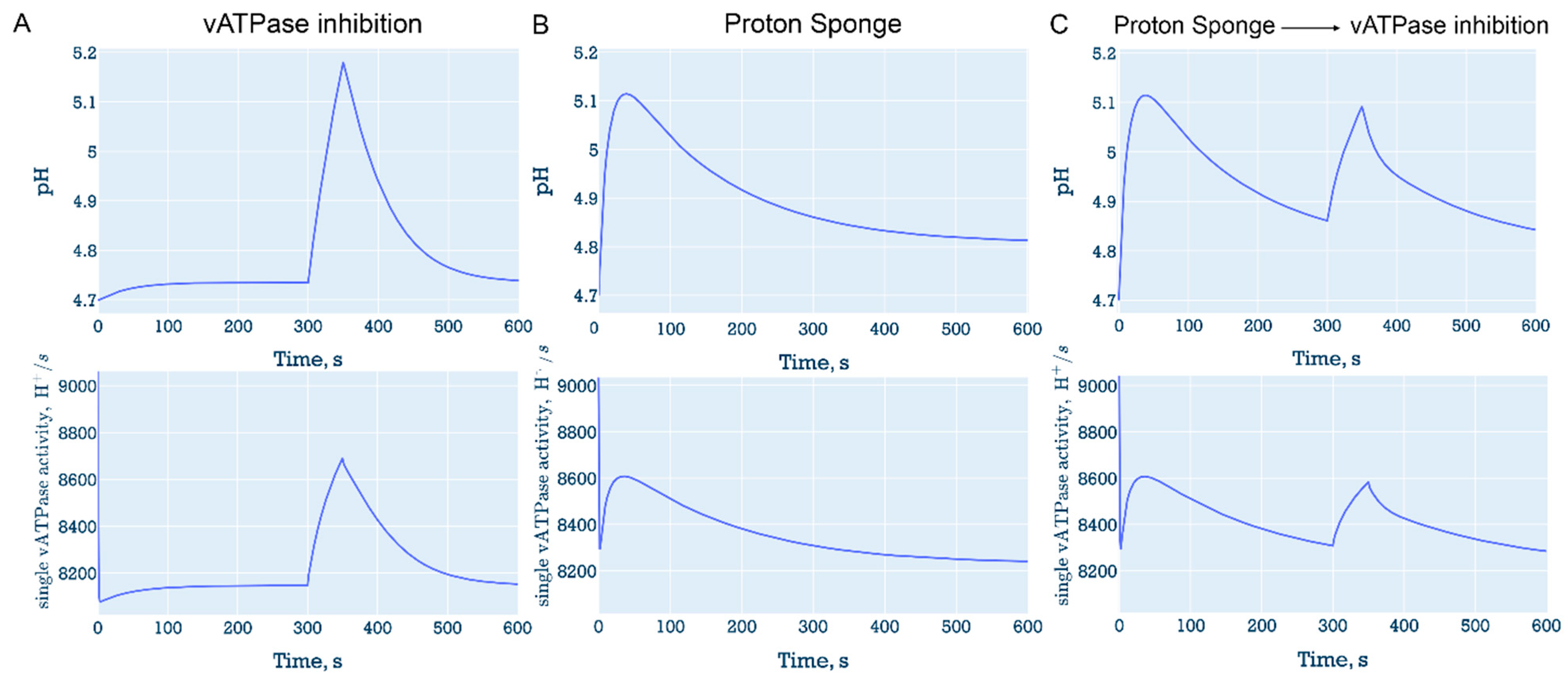

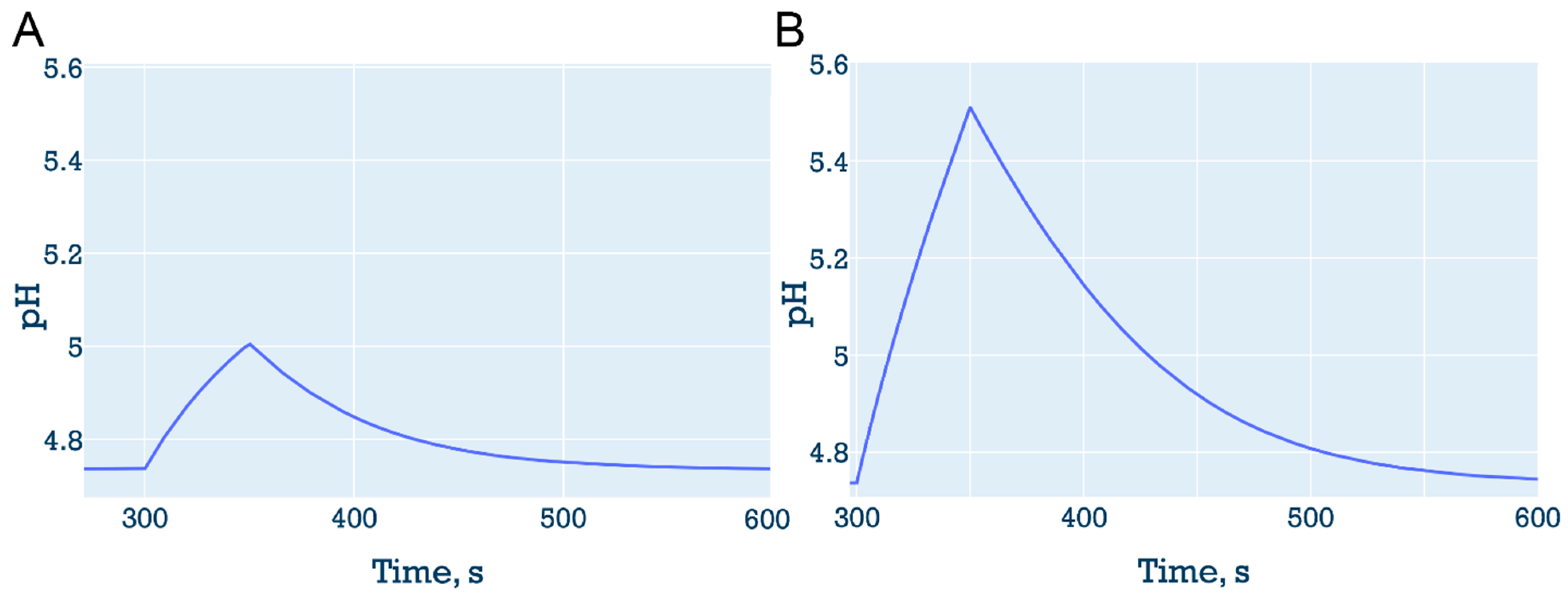

3.6.1. “Proton sponge” followed by decrease in the number of vATPase

3.6.2. Proton efflux with vATPase inhibition

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data availability

Acknowledgments

Declaration of competing interest

Abbreviations

References

- R.M. Perera, R. Zoncu, The Lysosome as a Regulatory Hub, Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 32 (2016) 223–253. [CrossRef]

- S.R. Bonam, F. Wang, S. Muller, Lysosomes as a therapeutic target, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019 1812 18 (2019) 923–948. [CrossRef]

- D. Carmona-Gutierrez, A.L. Hughes, F. Madeo, C. Ruckenstuhl, The crucial impact of lysosomes in aging and longevity, Ageing Res. Rev. 32 (2016) 2–12. [CrossRef]

- T. Wyss-Coray, Ageing, neurodegeneration and brain rejuvenation, Nature 539 (2016) 180–186. [CrossRef]

- J.H. Lee, D.S. Yang, C.N. Goulbourne, E. Im, P. Stavrides, A. Pensalfini, H. Chan, C. Bouchet-Marquis, C. Bleiwas, M.J. Berg, C. Huo, J. Peddy, M. Pawlik, E. Levy, M. Rao, M. Staufenbiel, R.A. Nixon, Faulty autolysosome acidification in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models induces autophagic build-up of Aβ in neurons, yielding senile plaques, Nat. Neurosci. 25 (2022) 688–701. [CrossRef]

- X. Yan, Protein mishandling and impaired lysosomal proteolysis generated through calcium dysregulation in Alzheimer’s disease, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (2017) 2017. [CrossRef]

- U. Ozcan, Q. Cao, E. Yilmaz, A.-H. Lee, N.N. Iwakoshi, E. Ozdelen, G. Tuncman, C. Gorgun, L.H. Glimcher, G.S. Hotamisligil, Endoplasmic reticulum stress links obesity, insulin action, and type 2 diabetes, Science (80-. ). 306 (2004) 457–461. [CrossRef]

- D.J. Sillence, Glucosylceramide modulates endolysosomal pH in Gaucher disease, Mol. Genet. Metab. 109 (2013) 194–200. [CrossRef]

- E. Riederer, C. Cang, D. Ren, Lysosomal Ion Channels: What Are They Good For and Are They Druggable Targets?, Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 63 (2023) 19–41. [CrossRef]

- C.C. Scott, J. Gruenberg, Ion flux and the function of endosomes and lysosomes: PH is just the start: The flux of ions across endosomal membranes influences endosome function not only through regulation of the luminal pH, BioEssays 33 (2011) 103–110. [CrossRef]

- S. Weinert, S. Jabs, C. Supanchart, M. Schweizer, N. Gimber, M. Richter, J. Rademann, T. Stauber, U. Kornak, T.J. Jentsch, Lysosomal pathology and osteopetrosis upon loss of H+-driven lysosomal Cl- accumulation, Science (80-. ). 328 (2010) 1401–1403. [CrossRef]

- T.J.J. Gaia Novarino, Stefanie Weinert, Gesa Rickheit, Endosomal Chloride-Proton Exchange Rather Than Chloride Conductance Is Crucial for Renal Endocytosis, (2010) 1398–1401. [CrossRef]

- A.R. Graves, P.K. Curran, C.L. Smith, J.A. Mindell, The Cl-/H+ antiporter ClC-7 is the primary chloride permeation pathway in lysosomes, Nature 453 (2008) 788–792. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ishida, S. Nayak, J.A. Mindell, M. Grabe, A model of lysosomal pH regulation, J. Gen. Physiol. 141 (2013) 705–720. [CrossRef]

- C. Cang, B. Bekele, D. Ren, The voltage-gated sodium channel TPC1 confers endolysosomal excitability, Nat. Chem. Biol. 10 (2014) 463–469. [CrossRef]

- R. Fuchs, S. Schmid, I. Mellman, A possible role for Na+,K+-ATPase in regulating ATP-dependent endosome acidification, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86 (1989) 539–543. [CrossRef]

- E. Kosmidis, C.G. Shuttle, J. Preobraschenski, M. Ganzella, P.J. Johnson, S. Veshaguri, J. Holmkvist, M.P. Møller, O. Marantos, F. Marcoline, M. Grabe, J.L. Pedersen, R. Jahn, D. Stamou, Regulation of the mammalian-brain V-ATPase through ultraslow mode-switching, Nature 611 (2022) 827–834. [CrossRef]

- B.E. Steinberg, K.K. Huynh, A. Brodovitch, S. Jabs, T. Stauber, T.J. Jentsch, S. Grinstein, A cation counterflux supports lysosomal acidification, J. Cell Biol. 189 (2010) 1171–1186. [CrossRef]

- C. Cang, K. Aranda, Y. Seo, B. Gasnier, C. Cang, K. Aranda, Y. Seo, B. Gasnier, D. Ren, TMEM175 Is an Organelle K + Channel Regulating Lysosomal Function, Cell 162 (2015) 1101–1112. [CrossRef]

- C. Cang, Y. Zhou, B. Navarro, Y.J. Seo, K. Aranda, L. Shi, S. Battaglia-Hsu, I. Nissim, D.E. Clapham, D. Ren, mTOR regulates lysosomal ATP-sensitive two-pore Na+ channels to adapt to metabolic state, Cell 152 (2013) 778–790. [CrossRef]

- B.E. Steinberg, N. Touret, M. Vargas-Caballero, S. Grinstein, In situ measurement of the electrical potential across the phagosomal membrane using FRET and its contribution to the proton-motive force, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 (2007) 9523–9528. [CrossRef]

- J. Xiong, M.X. Zhu, Regulation of lysosomal ion homeostasis by channels and transporters, Sci. China Life Sci. 59 (2016) 777–791. [CrossRef]

- A. Ballabio, J.S. Bonifacino, Lysosomes as dynamic regulators of cell and organismal homeostasis, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21 (2020) 101–118. [CrossRef]

- R.E. Lawrence, R. Zoncu, The lysosome as a cellular centre for signalling, metabolism and quality control, Nat. Cell Biol. 21 (2019) 133–142. [CrossRef]

- J. Huotari, A. Helenius, Endosome maturation, EMBO J. 30 (2011) 3481–3500. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, X. Cheng, L. Yu, J. Yang, R. Calvo, S. Patnaik, X. Hu, Q. Gao, M. Yang, M. Lawas, M. Delling, J. Marugan, M. Ferrer, H. Xu, MCOLN1 is a ROS sensor in lysosomes that regulates autophagy, Nat. Commun. 7 (2016). [CrossRef]

- M. Hu, N. Zhou, W. Cai, H. Xu, Lysosomal solute and water transport, J. Cell Biol. 221 (2022) 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Z.E. Walton, C.H. Patel, R.C. Brooks, Y. Yu, A. Ibrahim-Hashim, M. Riddle, A. Porcu, T. Jiang, B.L. Ecker, F. Tameire, C. Koumenis, A.T. Weeraratna, D.K. Welsh, R. Gillies, J.C. Alwine, L. Zhang, J.D. Powell, C. V. Dang, Acid Suspends the Circadian Clock in Hypoxia through Inhibition of mTOR, Cell 174 (2018) 72-87.e32. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zi, Z. Zhang, Q. Feng, C. Kim, X.D. Wang, P.E. Scherer, J. Gao, B. Levine, Y. Yu, Quantitative phosphoproteomic analyses identify STK11IP as a lysosome-specific substrate of mTORC1 that regulates lysosomal acidification, Nat. Commun. 13 (2022) 1–12. [CrossRef]

- M.L. Skowyra, P.H. Schlesinger, T. V. Naismith, P.I. Hanson, Triggered recruitment of ESCRT machinery promotes endolysosomal repair, Science (80-. ). 360 (2018). [CrossRef]

- N.S. Ilyinsky, S. V. Nesterov, E.I. Shestoperova, A. V. Fonin, V.N. Uversky, V.I. Gordeliy, On the Role of Normal Aging Processes in the Onset and Pathogenesis of Diseases Associated with the Abnormal Accumulation of Protein Aggregates, Biochem. 86 (2021) 275–289. [CrossRef]

- R.L. Kendall, A. Holian, The role of lysosomal ion channels in lysosome dysfunction, Inhal. Toxicol. 33 (2021) 41–54. [CrossRef]

- P. Saftig, R. Puertollano, How Lysosomes Sense, Integrate, and Cope with Stress, Trends Biochem. Sci. 46 (2021) 97–112. [CrossRef]

- A.D. Vlasova, S.M. Bukhalovich, D.F. Bagaeva, A.P. Polyakova, N.S. Ilyinsky, S. V. Nesterov, F.M. Tsybrov, A.O. Bogorodskiy, E. V. Zinovev, A.E. Mikhailov, A. V Vlasov, A.I. Kuklin, V.I. Borshchevskiy, E. Bamberg, V.N. Uversky, V.I. Gordeliy, Intracellular microbial rhodopsin-based optogenetics to control metabolism and cell signaling, Chem. Soc. Rev. (2024). [CrossRef]

- V. Shevchenko, T. Mager, K. Kovalev, V. Polovinkin, A. Alekseev, J. Juettner, I. Chizhov, C. Bamann, C. Vavourakis, R. Ghai, I. Gushchin, V. Borshchevskiy, A. Rogachev, I. Melnikov, A. Popov, T. Balandin, F. Rodriguez-Valera, D.J. Manstein, G. Bueldt, E. Bamberg, V. Gordeliy, Inward H+ pump xenorhodopsin: Mechanism and alternative optogenetic approach, Sci. Adv. 3 (2017) 1–11. [CrossRef]

- N.S. Ilyinsky, S.M. Bukhalovich, D.F. Bagaeva, S. V. Nesterov, A.A. Alekseev, F.M. Tsybrov, A.O. Bogorodskiy, V.A. Alekhin, S.F. Nazarova, O. V. Moiseeva, A.D. Vlasova, K. V. Kovalev, A.E. Mikhailov, A. V. Rogachev, E. Bamberg, V.I. Borshchevskiy, V.I. Gordeliy, Optogenetic control of lysosome function, BioRxiv (2023) 2023.08.02.551716. [CrossRef]

- J.H. Lee, M.K. McBrayer, D.M. Wolfe, L.J. Haslett, A. Kumar, Y. Sato, P.P.Y. Lie, P. Mohan, E.E. Coffey, U. Kompella, C.H. Mitchell, E. Lloyd-Evans, R.A. Nixon, Presenilin 1 Maintains Lysosomal Ca2+ Homeostasis via TRPML1 by Regulating vATPase-Mediated Lysosome Acidification, Cell Rep. 12 (2015) 1430–1444. [CrossRef]

- K.A. Christensen, J.T. Myers, J.A. Swanson, pH-dependent regulation of lysosomal calcium in macrophages, J. Cell Sci. 115 (2002) 599–607. [CrossRef]

- N. Maliar, K. Kovalev, C. Baeken, T. Balandin, R. Astashkin, M. Rulev, A. Alekseev, N. Ilyinsky, A. Rogachev, V. Chupin, D. Dolgikh, M. Kirpichnikov, V. Gordeliy, Crystal structure of the N112A mutant of the light-driven sodium pump KR2, Crystals 10 (2020) 1–15. [CrossRef]

- E.G. Govorunova, Y. Gou, O.A. Sineshchekov, H. Li, X. Lu, Y. Wang, L.S. Brown, F. St-Pierre, M. Xue, J.L. Spudich, Kalium channelrhodopsins are natural light-gated potassium channels that mediate optogenetic inhibition, Nat. Neurosci. 25 (2022) 967–974. [CrossRef]

- R. Astashkin, K. Kovalev, S. Bukhdruker, S. Vaganova, A. Kuzmin, A. Alekseev, T. Balandin, D. Zabelskii, I. Gushchin, A. Royant, D. Volkov, G. Bourenkov, E. Koonin, M. Engelhard, E. Bamberg, V. Gordeliy, Structural insights into light-driven anion pumping in cyanobacteria, Nat. Commun. 13 (2022) 1–13. [CrossRef]

- V. Gradinaru, K.R. Thompson, K. Deisseroth, eNpHR: a Natronomonas halorhodopsin enhanced for optogenetic applications, Brain Cell Biol. 36 (2008) 129–139. [CrossRef]

- M. Grabe, G. Oster, Regulation of organelle acidity, J. Gen. Physiol. 117 (2001) 329–343. [CrossRef]

- R. Astaburuaga, O.D.Q. Haro, T. Stauber, A. Relógio, A mathematical model of lysosomal ion homeostasis points to differential effects of Cl− transport in Ca2+ dynamics, Cells 8 (2019). [CrossRef]

- B. Hille, Ionic channels of excitable membranes, 2nd ed., Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, MA, 1992. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhao, S. Benlekbir, J.L. Rubinstein, Electron cryomicroscopy observation of rotational states in a eukaryotic V-ATPase, Nature 521 (2015) 241–245. [CrossRef]

- Y. Guo, Y. Zhang, R. Yan, B. Huang, F. Ye, L. Wu, X. Chi, Y. shi, Q. Zhou, Cryo-EM structures of recombinant human sodium-potassium pump determined in three different states, Nat. Commun. 13 (2022) 1–9. [CrossRef]

- T. Nishizawa, S. Kita, A.D. Maturana, N. Furuya, K. Hirata, G. Kasuya, S. Ogasawara, N. Dohmae, T. Iwamoto, R. Ishitani, Structural basis for the counter-transport mechanism of a H+/Ca2+ exchanger, Science (80-. ). 341 (2013) 168–172.

- M. Hirschi, M.A. Herzik Jr, J. Wie, Y. Suo, W.F. Borschel, D. Ren, G.C. Lander, S.-Y. Lee, Cryo-electron microscopy structure of the lysosomal calcium-permeable channel TRPML3, Nature 550 (2017) 411–414.

- M. Schrecker, J. Korobenko, R.K. Hite, Cryo-EM structure of the lysosomal chloride-proton exchanger CLC-7 in complex with OSTM1, Elife 9 (2020) e59555.

- A. Saminathan, J. Devany, A.T. Veetil, B. Suresh, K.S. Pillai, M. Schwake, Y. Krishnan, A DNA-based voltmeter for organelles, Nat. Nanotechnol. 16 (2021) 96–103. [CrossRef]

- M. Koivusalo, B.E. Steinberg, D. Mason, S. Grinstein, In situ measurement of the electrical potential across the lysosomal membrane using FRET, Traffic 12 (2011) 972–982. [CrossRef]

- F. Lucien, P.P. Pelletier, R.R. Lavoie, J.M. Lacroix, S. Roy, J.L. Parent, D. Arsenault, K. Harper, C.M. Dubois, Hypoxia-induced mobilization of NHE6 to the plasma membrane triggers endosome hyperacidification and chemoresistance, Nat. Commun. 8 (2017). [CrossRef]

- C.C. Cain, D.M. Sipe, R.F. Murphy, Regulation of endocytic pH by the Na+,K+-ATPase in living cells, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86 (1989) 544–548. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lin-Moshier, M. V. Keebler, R. Hooper, M.J. Boulware, X. Liu, D. Churamani, M.E. Abood, T.F. Walseth, E. Brailoiu, S. Patel, J.S. Marchant, The Two-pore channel (TPC) interactome unmasks isoform-specific roles for TPCs in endolysosomal morphology and cell pigmentation, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111 (2014) 13087–13092. [CrossRef]

- M.E. Maxson, Y.M. Abbas, J.Z. Wu, J.D. Plumb, S. Grinstein, J.L. Rubinstein, Detection and quantification of the vacuolar H+ATPase using the Legionella effector protein SidK, J. Cell Biol. 221 (2022). [CrossRef]

- S. Takamori, M. Holt, K. Stenius, E.A. Lemke, M. Grønborg, D. Riedel, H. Urlaub, S. Schenck, B. Brügger, P. Ringler, S.A. Müller, B. Rammner, F. Gräter, J.S. Hub, B.L. De Groot, G. Mieskes, Y. Moriyama, J. Klingauf, H. Grubmüller, J. Heuser, F. Wieland, R. Jahn, Molecular Anatomy of a Trafficking Organelle, Cell 127 (2006) 831–846. [CrossRef]

- M. Grabe, H. Wang, G. Oster, The mechanochemistry of V-ATPase proton pumps, Biophys. J. 78 (2000) 2798–2813. [CrossRef]

- T. Iida, Y. Minagawa, H. Ueno, F. Kawai, T. Murata, R. Iino, Single-molecule analysis reveals rotational substeps and chemo-mechanical coupling scheme of Enterococcus hirae V1-ATPase, J. Biol. Chem. 294 (2019) 17017–17030. [CrossRef]

- B.A. Feniouk, M.A. Kozlova, D.A. Knorre, D.A. Cherepanov, A.Y. Mulkidjanian, W. Junge, The proton-driven rotor of ATP synthase: Ohmic conductance (10 fS), and absence of voltage gating, Biophys. J. 86 (2004) 4094–4109. [CrossRef]

- W. Junge, N. Nelson, ATP synthase, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 84 (2015) 631–657. [CrossRef]

- P. Virtanen, R. Gommers, T.E. Oliphant, M. Haberland, T. Reddy, D. Cournapeau, E. Burovski, P. Peterson, W. Weckesser, J. Bright, SciPy 1.0: fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python, Nat. Methods 17 (2020) 261–272.

- V. Faundez, H.C. Hartzell, Intracellular chloride channels: determinants of function in the endosomal pathway., Sci. STKE 2004 (2004) 1–8. [CrossRef]

- P. Li, M. Gu, H. Xu, Lysosomal Ion Channels as Decoders of Cellular Signals, Trends Biochem. Sci. 44 (2019) 110–124. [CrossRef]

- L.B. Shi, K. Fushimi, H.R. Bae, A.S. Verkman, Heterogeneity in ATP-dependent acidification in endocytic vesicles from kidney proximal tubule. Measurement of pH in individual endocytic vesicles in a cell-free system, Biophys. J. 59 (1991) 1208–1217. [CrossRef]

- L. Yu, C.K. McPhee, L. Zheng, G.A. Mardones, Y. Rong, J. Peng, N. Mi, Y. Zhao, Z. Liu, F. Wan, D.W. Hailey, V. Oorschot, J. Klumperman, E.H. Baehrecke, M.J. Lenardo, Termination of autophagy and reformation of lysosomes regulated by mTOR, Nature 465 (2010) 942–946. [CrossRef]

- C. López-Otín, M.A. Blasco, L. Partridge, M. Serrano, G. Kroemer, Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe., Cell (2022). [CrossRef]

- V.D. Manyilov, N.S. Ilyinsky, S. V. Nesterov, B.M.G.A. Saqr, G.W. Dayhoff, E. V. Zinovev, S.S. Matrenok, A. V. Fonin, I.M. Kuznetsova, K.K. Turoverov, V. Ivanovich, V.N. Uversky, Chaotic aging: intrinsically disordered proteins in aging-related processes, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Yoshimori, A. Yamamoto, Y. Moriyama, M. Futai, Y. Tashiro, Bafilomycin A1, a specific inhibitor of vacuolar-type H+-ATPase, inhibits acidification and protein degradation in lysosomes of cultured cells, J. Biol. Chem. 266 (1991) 17707–17712. [CrossRef]

- A.J. Morgan, L.C. Davis, A. Galione, Imaging approaches to measuring lysosomal calcium, Elsevier Ltd, 2015. [CrossRef]

- V. V. Teplova, A.A. Tonshin, P.A. Grigoriev, N.E.L. Saris, M.S. Salkinoja-Salonen, Bafilomycin A1 is a potassium ionophore that impairs mitochondrial functions, J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 39 (2007) 321–329. [CrossRef]

- A. V. Zhdanov, R.I. Dmitriev, D.B. Papkovsky, Bafilomycin A1 activates respiration of neuronal cells via uncoupling associated with flickering depolarization of mitochondria, Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 68 (2011) 903–917. [CrossRef]

- S. Kaushik, A.M. Cuervo, Proteostasis and aging, Nat. Med. 21 (2015) 1406–1415. [CrossRef]

- D.W. Pack, A.S. Hoffman, S. Pun, P.S. Stayton, Design and development of polymers for gene delivery, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 4 (2005) 581–593.

- M. Cao, X. Luo, K. Wu, X. He, Targeting lysosomes in human disease: from basic research to clinical applications, Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 6 (2021). [CrossRef]

- F. Marceau, M.T. Bawolak, R. Lodge, J. Bouthillier, A. Gagné-Henley, R. C.-Gaudreault, G. Morissette, Cation trapping by cellular acidic compartments: Beyond the concept of lysosomotropic drugs, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 259 (2012) 1–12. [CrossRef]

- E.C. Freeman, L.M. Weiland, W.S. Meng, Modeling the proton sponge hypothesis: examining proton sponge effectiveness for enhancing intracellular gene delivery through multiscale modeling, J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 24 (2013) 398–416.

- A. Kaasik, D. Safiulina, A. Zharkovsky, V. Veksler, Regulation of mitochondrial matrix volume, Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 292 (2007) C157–C163.

- L.M.P. Vermeulen, S.C. De Smedt, K. Remaut, K. Braeckmans, The proton sponge hypothesis: Fable or fact?, Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 129 (2018) 184–190.

- J.J. Rennick, C.J. Nowell, C.W. Pouton, A.P.R. Johnston, Resolving subcellular pH with a quantitative fluorescent lifetime biosensor, Nat. Commun. 13 (2022). [CrossRef]

- M. Wojnilowicz, A. Glab, A. Bertucci, F. Caruso, F. Cavalieri, Super-resolution Imaging of Proton Sponge-Triggered Rupture of Endosomes and Cytosolic Release of Small Interfering RNA, ACS Nano 13 (2019) 187–202. [CrossRef]

- A.A. Al-Bari, Chloroquine analogues in drug discovery: New directions of uses, mechanisms of actions and toxic manifestations from malaria to multifarious diseases, J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70 (2014) 1608–1621. [CrossRef]

- A. Jorge, C. Ung, L.H. Young, R.B. Melles, H.K. Choi, Hydroxychloroquine retinopathy — implications of research advances for rheumatology care, Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 14 (2018) 693–703. [CrossRef]

- L. Laraia, G. Garivet, D.J. Foley, N. Kaiser, S. Müller, S. Zinken, T. Pinkert, J. Wilke, D. Corkery, A. Pahl, S. Sievers, P. Janning, C. Arenz, Y. Wu, R. Rodriguez, H. Waldmann, Image-Based Morphological Profiling Identifies a Lysosomotropic, Iron-Sequestering Autophagy Inhibitor, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 5721–5729. [CrossRef]

- M. Mauthe, I. Orhon, C. Rocchi, X. Zhou, M. Luhr, K.J. Hijlkema, R.P. Coppes, N. Engedal, M. Mari, F. Reggiori, Chloroquine inhibits autophagic flux by decreasing autophagosome-lysosome fusion, Autophagy 14 (2018) 1435–1455. [CrossRef]

- M. Sakurai, T. Kuwahara, Two methods to analyze LRRK2 functions under lysosomal stress: The measurements of cathepsin release and lysosomal enlargement, in: Exp. Model. Park. Dis., Springer, 2021: pp. 63–72.

- E. Fabbri, M. Zoli, M. Gonzalez-Freire, M.E. Salive, S.A. Studenski, L. Ferrucci, Aging and Multimorbidity: New Tasks, Priorities, and Frontiers for Integrated Gerontological and Clinical Research, J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 16 (2015) 640–647. [CrossRef]

- O. Tacar, P. Sriamornsak, C.R. Dass, Doxorubicin: An update on anticancer molecular action, toxicity and novel drug delivery systems, J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 65 (2013) 157–170. [CrossRef]

- B. Zhitomirsky, Y.G. Assaraf, Lysosomal sequestration of hydrophobic weak base chemotherapeutics triggers lysosomal biogenesis and lysosomedependent cancer multidrug resistance, Oncotarget 6 (2015) 1143–1156. [CrossRef]

- S. Schmeisser, K. Schmeisser, S. Weimer, M. Groth, S. Priebe, E. Fazius, D. Kuhlow, D. Pick, J.W. Einax, R. Guthke, M. Platzer, K. Zarse, M. Ristow, Mitochondrial hormesis links low-dose arsenite exposure to lifespan extension, Aging Cell 12 (2013) 508–517. [CrossRef]

- D.L. Li, Z. V. Wang, G. Ding, W. Tan, X. Luo, A. Criollo, M. Xie, N. Jiang, H. May, V. Kyrychenko, J.W. Schneider, T.G. Gillette, J.A. Hill, Doxorubicin Blocks Cardiomyocyte Autophagic Flux by Inhibiting Lysosome Acidification, Circulation 133 (2016) 1668–1687. [CrossRef]

- B.J. Baker, H. Mutoh, D. Dimitrov, W. Akemann, A. Perron, Y. Iwamoto, L. Jin, L.B. Cohen, E.Y. Isacoff, V.A. Pieribone, T. Hughes, T. Knöpfel, Genetically encoded fluorescent sensors of membrane potential, Brain Cell Biol. 36 (2008) 53–67. [CrossRef]

- Y. Shen, M. Rosendale, R.E. Campbell, D. Perrais, pHuji, a pH-sensitive red fluorescent protein for imaging of exo- and endocytosis, J. Cell Biol. 207 (2014) 419–432. [CrossRef]

- Y. Shen, Y. Wen, S. Sposini, A.A. Vishwanath, A.S. Abdelfattah, E.R. Schreiter, M.J. Lemieux, J. de Juan-Sanz, D. Perrais, R.E. Campbell, Rational Engineering of an Improved Genetically Encoded pH Sensor Based on Superecliptic pHluorin, ACS Sensors 8 (2023) 3014–3022. [CrossRef]

- E. Persi, M. Duran-Frigola, M. Damaghi, W.R. Roush, P. Aloy, J.L. Cleveland, R.J. Gillies, E. Ruppin, Systems analysis of intracellular pH vulnerabilities for cancer therapy, Nat. Commun. 9 (2018). [CrossRef]

- A. Kabir, A. Muth, Polypharmacology: The science of multi-targeting molecules, Pharmacol. Res. 176 (2022) 106055. [CrossRef]

- B.R. Rost, F. Schneider, M.K. Grauel, C. Wozny, C. G Bentz, A. Blessing, T. Rosenmund, T.J. Jentsch, D. Schmitz, P. Hegemann, C. Rosenmund, Optogenetic acidification of synaptic vesicles and lysosomes, Nat. Neurosci. 18 (2015) 1845–1852. [CrossRef]

- K. Yokoyama, E. Muneyuki, T. Amano, S. Mizutani, M. Yoshida, M. Ishida, S. Ohkuma, V-ATPase of Thermus thermophilus is inactivated during ATP hydrolysis but can synthesize ATP, J. Biol. Chem. 273 (1998) 20504–20510. [CrossRef]

- A. V. Vlasov, S.D. Osipov, N.A. Bondarev, V.N. Uversky, V.I. Borshchevskiy, M.F. Yanyushin, I. V. Manukhov, A. V. Rogachev, A.D. Vlasova, N.S. Ilyinsky, A.I. Kuklin, N.A. Dencher, V.I. Gordeliy, ATP synthase FOF1 structure, function, and structure-based drug design, 2022. [CrossRef]

- B.A. Webb, F.M. Aloisio, R.A. Charafeddine, J. Cook, T. Wittmann, D.L. Barber, pHLARE: A new biosensor reveals decreased lysosome pH in cancer cells, Mol. Biol. Cell 32 (2021) 131–142. [CrossRef]

- B. Liu, J. Palmfeldt, L. Lin, A. Colaço, K.K.B. Clemmensen, J. Huang, F. Xu, X. Liu, K. Maeda, Y. Luo, M. Jäättelä, STAT3 associates with vacuolar H+-ATPase and regulates cytosolic and lysosomal pH, Cell Res. 28 (2018) 996–1012. [CrossRef]

- A. Vlasova, A. Polyakova, A. Gromova, S. Dolotova, S. Bukhalovich, D. Bagaeva, N. Bondarev, F. Tsybrov, K. Kovalev, A. Mikhailov, Optogenetic cytosol acidification of mammalian cells using an inward proton-pumping rhodopsin, Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 242 (2023) 124949.

- C.E.T. Donahue, M.D. Siroky, K.A. White, An Optogenetic Tool to Raise Intracellular pH in Single Cells and Drive Localized Membrane Dynamics, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 18877–18887. [CrossRef]

- I.S. Okhrimenko, K. Kovalev, L.E. Petrovskaya, N.S. Ilyinsky, A.A. Alekseev, E. Marin, T.I. Rokitskaya, Y.N. Antonenko, S.A. Siletsky, P.A. Popov, Y.A. Zagryadskaya, D. V. Soloviov, I. V. Chizhov, D. V. Zabelskii, Y.L. Ryzhykau, A. V. Vlasov, A.I. Kuklin, A.O. Bogorodskiy, A.E. Mikhailov, D. V. Sidorov, S. Bukhalovich, F. Tsybrov, S. Bukhdruker, A.D. Vlasova, V.I. Borshchevskiy, D.A. Dolgikh, M.P. Kirpichnikov, E. Bamberg, V.I. Gordeliy, Mirror proteorhodopsins, Commun. Chem. 6 (2023) 1–16. [CrossRef]

- K. Kovalev, F. Tsybrov, A. Alekseev, V. Shevchenko, D. Soloviov, S. Siletsky, G. Bourenkov, M. Agthe, M. Nikolova, D. von Stetten, R. Astashkin, S. Bukhdruker, I. Chizhov, A. Royant, A. Kuzmin, I. Gushchin, R. Rosselli, F. Rodriguez-Valera, N. Ilyinskiy, A. Rogachev, V. Borshchevskiy, T.R. Schneider, E. Bamberg, V. Gordeliy, Mechanisms of inward transmembrane proton translocation, Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 30 (2023) 970–979. [CrossRef]

| Type of stress/impact | Description | Mathematical description |

| Lysosome maturation | Changes in initial ion concentrations corresponding to their values in the late endosome. All ion transporters function as in the lysosomal norm model except vATPase and NKA, which gradually increase/decrease in activity. | Initial [Cl-] = 58 mM [K+] = 40 mM [Na+] = 50 mM pH = 5.8 Δψ = 50 mV |

| Short-term lysosome membrane permeabilization | Increased permeability to all ions and water for ~12 minutes |

by 100- or 10-fold increase |

| Short-term vATPase “knockout” | Short-term (50 seconds) shutdown of vATPase |

Temporarily |

| Short-term volume enlargement | Short-term (50 seconds) increase in water flux into the lysosome, causing it to swell |

Temporarily |

| Ca signaling as response to vATPase inhibition | Inhibition of vATPase activity and monitoring of changes in calcium concentration and its channel activity | |

| Ca signaling as response to proton efflux | Adding a constant value to the proton flux | |

| Cationic amphiphilic drugs (CAD) as Lysosomal storage diseases (LSD) model | Modelling of “proton sponge” accumulation in the lysosome leading to lumen deacidification | Water influx increased due to “proton sponge” presence. Description in the main part of the work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).