Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

10 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

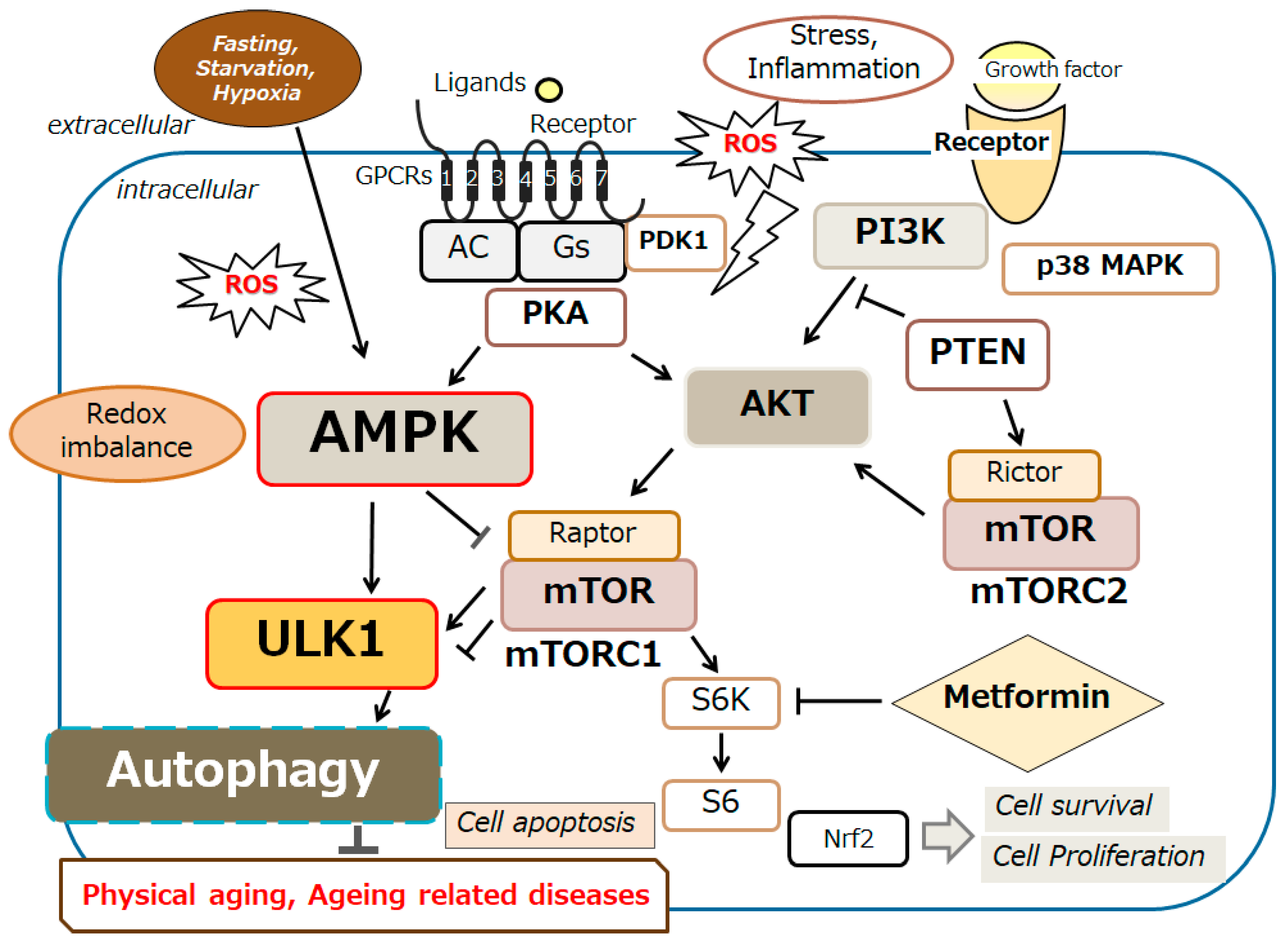

2. Relationship Between Autophagy and Aging Related Diseases by the Modulation of AMPK Signaling Pathway

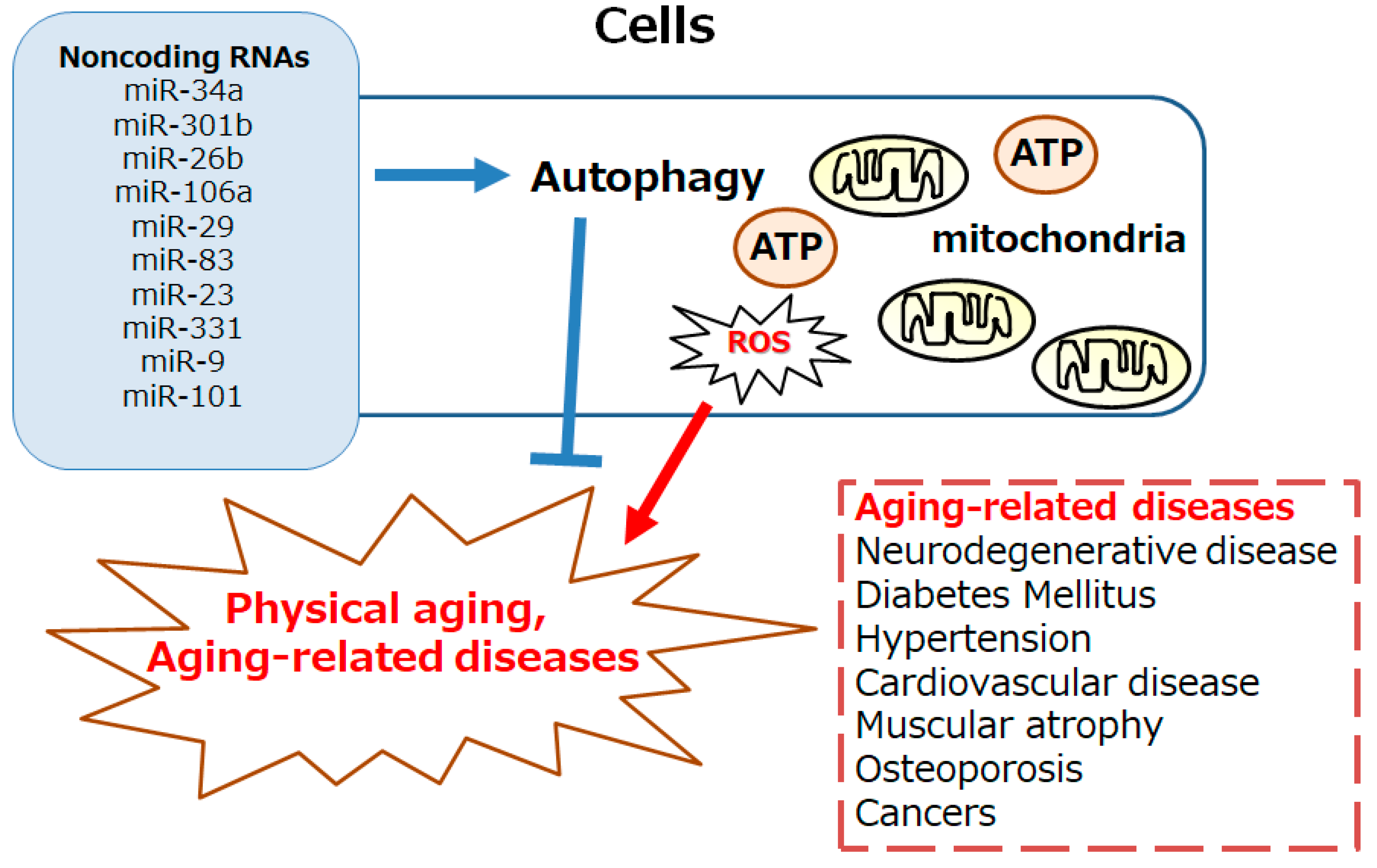

3. Several ncRNAs Involved in the Longevity via the Modulation of Autophagy

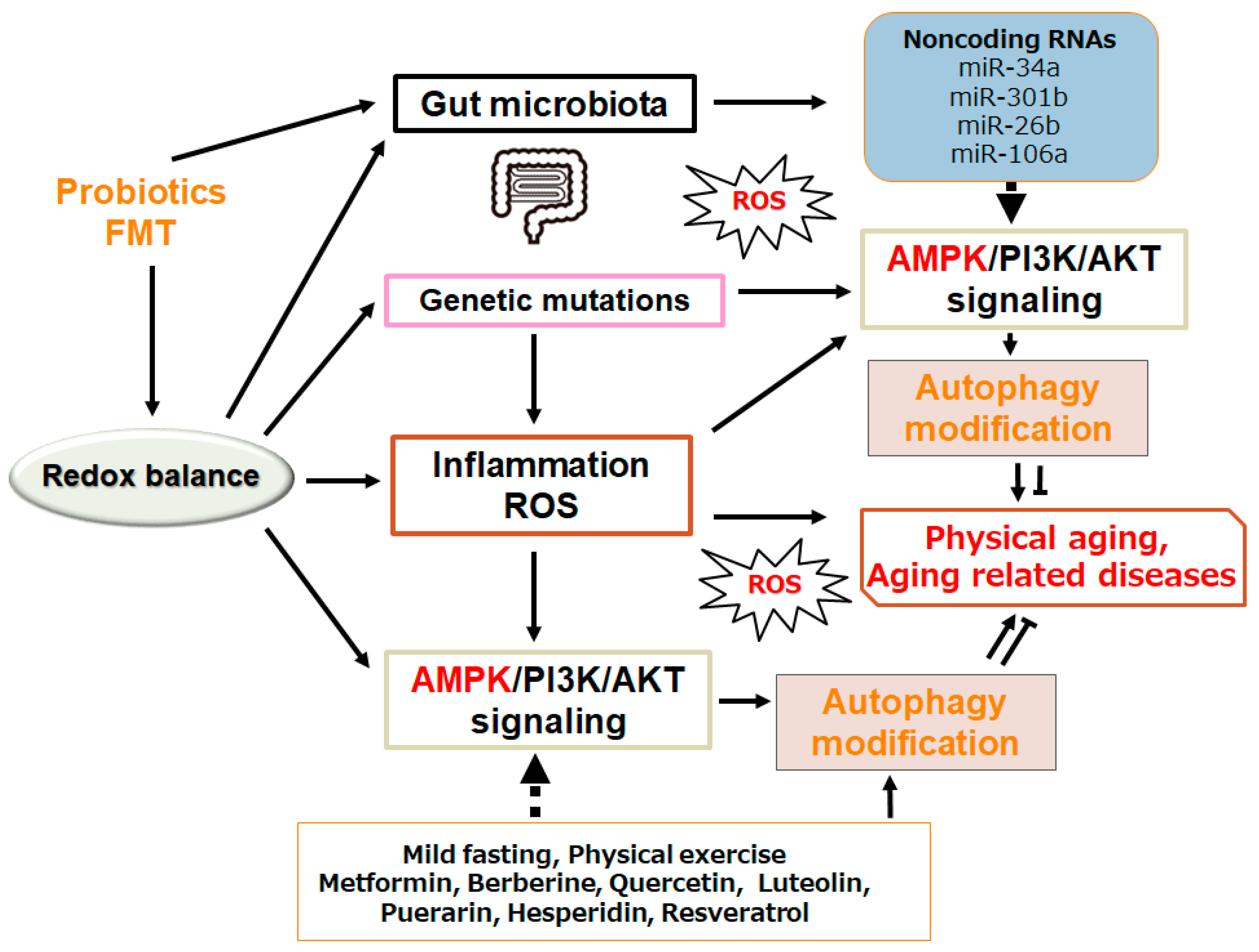

4. Possible Tactics with Certain Dieting for the Longevity

5. Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMP | adenosine monophosphate |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| AMPK | adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase |

| C. elegans | Caenorhabditis elegans |

| FMT | fecal microbiota transplantation |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| mTOR | mechanistic/mammalian target of rapamycin |

| mTORC1 | mTOR complex 1 |

| NAFLD | nonalcoholic fatty liver disease |

| QOL | quality of life |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| 3′UTR | three prime untranslated region |

| ULK1 | autophagy activating kinase 1 |

| UVA | ultraviolet ray A |

| UVB | ultraviolet ray B |

References

- Longo, V.D.; Antebi, A.; Bartke, A.; Barzilai, N.; Brown-Borg, H.M.; Caruso, C.; Curiel, T.J.; de Cabo, R.; Franceschi, C.; Gems, D.; et al. Interventions to Slow Aging in Humans: Are We Ready? Aging Cell 2015, 14, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Jo, D.G.; Park, D.; Chung, H.Y.; Mattson, M.P. ; Jo, D.G.; Park, D.; Chung, H.Y.; Mattson, M.P. Adaptive cellular stress pathways as therapeutic targets of dietary phytochemicals: focus on the nervous system. Pharmacological Reviews 2014, 66, 815–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattison, J.A.; Colman, R.J.; Beasley, T.M.; Allison, D.B.; Kemnitz, J.W.; Roth, G.S.; Ingram, D.K.; Weindruch, R.; de Cabo, R.; Anderson, R.M. Caloric restriction improves health and survival of rhesus monkeys. Nature Communications 2017, 8, 14063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, L.; Partridge, L.; Longo, V.D. Extending healthy life span--from yeast to humans. Science 2010, 328, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gremeaux, V.; Gayda, M.; Lepers, R.; Sosner, P.; Juneau, M.; Nigam, A. Exercise and longevity. Maturitas 2012, 73, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekmekcioglu, C. Nutrition and longevity - From mechanisms to uncertainties. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2020, 60, 3063–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinsztein, D.C.; Mariño, G.; Kroemer, G. Autophagy and aging. Cell 2011, 146, 682–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaushik, S.; Tasset, I.; Arias, E.; Pampliega, O.; Wong, E.; Martinez-Vicente, M.; Cuervo, A.M. Autophagy and the hallmarks of aging. Aging Research Reviews 2021, 72, 101468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Puleston, D.J.; Simon, A.K. Autophagy and Immune Senescence. Trends in Molecular Medicine 2016, 22, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, C.; Leri, M.; Stefani, M.; Bucciantini, M. Autophagy-related proteins: Potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of aging-related diseases. Aging Research Reviews 2023, 89, 101967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thalyana, S.V.; Slack, F.J. MicroRNAs and their roles in aging. J Cell Sci 2012, 125, 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Maciotta, S.; Meregalli, M.; Torrente, Y. The involvement of microRNAs in neurodegenerative diseases. Front Cell Neurosci 2013, 7, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, R.; Noble, W.; Tartaglia, G.G.; Buckley, N.J. Neurodegeneration as an RNA disorder. Prog Neurobiol 2012, 99, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Inoue, K.; Ishii, J.; Vanti, W.B.; Voronov, S.V.; Murchison, E.; Hannon,G. ; Abeliovich, A. A MicroRNA Feedback Circuit in Midbrain Dopamine Neurons. Science 2007, 317, 1220–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beermann, J.; Piccoli, M.T.; Viereck, J.; Thum, T. Non-coding RNAs in development and disease: Background, mechanisms, and therapeutic approaches. Physiol Rev 2016, 96, 1297–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; He, P.; Tian, Q.; Luo, Y.; He, Y.; Liu, C.; Gong, P.; Guo, Y.; Ye, Q.; Li, M. Genetic modification of miR-34a enhances efficacy of transplanted human dental pulp stem cells after ischemic stroke. Neural Regen. Res 2023, 18, 2029–2036. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Li, P.; Gao, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Bledsoe, G.; Chang, E.; Chao, L.; Chao, J. Kallistatin reduces vascular senescence and aging by regulating microRNA-34a-SIRT1 pathway. Aging Cell 2017, 16, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamakuchi, M.; Ferlito, M.; Lowenstein, C.J. miR-34a repression of SIRT1 regulates apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008, 105, 13421–13426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinser, H.E.; Pincus, Z. MicroRNAs as modulators of longevity and the aging process. Hum Genet 2020, 139, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluzzi, L.; Baehrecke, E.H.; Ballabio, A.; Boya, P.; Bravo-San Pedro, J.M.; Cecconi, F.; Choi, A.M.; Chu, C.T.; Codogno, P.; Colombo, M.I.; et al. Molecular definitions of autophagy and related processes. The EMBO Journal 2017, 36, 1811–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, O.; Otsu, K. Role of autophagy in aging. Journal of Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2012, 60, 242–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Han, Z.; Ding, L.; Wang, P.; He, X.; Lin, L. The molecular mechanism of aging and the role in neurodegenerative diseases. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.Q.; Lu, J.H.; Yue, Z.Y. Autophagy in aging and aging-associated diseases. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2013, 34, 605–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Ouyang, C.; Meng, N. The association between ferroptosis and autophagy in cardiovascular diseases. Cell Biochemistry and Function 2024, 42, e3985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soda, K.; Kano, Y.; Chiba, F. Food polyamine and cardiovascular disease--an epidemiological study. Global Journal of Health Science 2012, 4, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, O. Autophagy in the Heart. Official Journal of the Japanese Circulation Society 2019, 83, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, T.; Abdellatif, M.; Zimmermann, A.; Schroeder, S.; Pendl, T.; Harger, A.; Stekovic, S.; Schipke, J.; Magnes, C.; Schmidt, A.; et al. Dietary spermidine for lowering high blood pressure. Autophagy 2017, 13, 767–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, X.; Song, Y.; Xue, Z.; Qian, H.; Wang, S.; Wan, G.; Zheng, X.; et al. Induction of autophagy by spermidine is neuroprotective via inhibition of caspase 3-mediated Beclin 1 cleavage. Cell Death & Disease 2017, 8, e2738. [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist, S.J.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D.; Gupta, V.K.; Bhukel, A.; Mertel, S.; Eisenberg, T.; Madeo, F. Spermidine-triggered autophagy ameliorates memory during aging. Autophagy 2014, 10, 178–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, T.T.; Li, H.; Dai, Z.; Lau, G.K.; Li, B.Y.; Zhu, W.L.; Liu, X.Q.; Liu, H.F.; Cai, W.W.; Huang, S.Q.; et al. Spermidine and spermine delay brain aging by inducing autophagy in SAMP8 mice. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 12, 6401–6414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Molina, B.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I.; Lambertos, A.; Tinahones, F.J.; Peñafiel, R. Dietary and Gut Microbiota Polyamines in Obesity- and Age-Related Diseases. Frontiers in Nutrition 2019, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervelli, M.; Leonetti, A.; Duranti, G.; Sabatini, S.; Ceci, R.; Mariottini, P. Skeletal Muscle Pathophysiology: The Emerging Role of Spermine Oxidase and Spermidine. Medical Sciences (Basel) 2018, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Alsaleh, G.; Feltham, J.; Sun, Y.; Napolitano, G.; Riffelmacher, T.; Charles, P.; Frau, L.; Hublitz, P.; Yu, Z.; et al. Polyamines Control eIF5A Hypusination, TFEB Translation, and Autophagy to Reverse B Cell Senescence. Molecular Cell 2019, 76, 110–125.e119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klionsky, D.J.; Petroni, G.; Amaravadi, R.K.; Baehrecke, E.H.; Ballabio, A.; Boya, P.; Bravo-San Pedro, J.M.; Cadwell, K.; Cecconi, F.; Choi, A.M.K.; et al. Autophagy in major human diseases. The EMBO Journal 2021, 40, e108863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantó, C.; Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Feige, J.N.; Lagouge, M.; Noriega, L.; Milne, J.C.; Elliott, P.J.; Puigserver, P.; Auwerx, J. AMPK regulates energy expenditure by modulating NAD+ metabolism and SIRT1 activity. Nature 2009, 458, 1056–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.S.; Lai, T.H.; Ahmed, M.; Pham, T.M.; Elashkar, O.; Bahar, E.; Kim, D.R. Regulation of TGF-beta1-Induced EMT by Autophagy-Dependent Energy Metabolism in Cancer Cells. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 4845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.X.; Li, C.; Pang, X.R.; Zhang, J.; Yu, G.C.; Yeo, A.J.; Lavin, M.F.; Shao, H. Jia, Q.; Peng, C. Metformin attenuates silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis by activating autophagy via the AMPK-mTOR signaling pathway. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12, 719589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trelford, C.B.; Di Guglielmo, G.M. Canonical and Non-canonical TGFbeta Signaling Activate Autophagy in an ULK1-Dependent Manner. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9, 712124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zachari, M.; Ganley, I.G. The mammalian ULK1 complex and autophagy initiation. Essays in Biochemistry 2017, 61, 585–596. [Google Scholar]

- Egan, D.; Kim, J.; Shaw, R.J.; Guan, K.L. The autophagy initiating kinase ULK1 is regulated via opposing phosphorylation by AMPK and mTOR. Autophagy 2011, 7, 643–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, EY. mTORC1 Phosphorylates the ULK1-mAtg13-FIP200 Autophagy Regulatory Complex. Science Signaling 2009, 2, pe51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.; Hall, M.N.; Lin, S.C.; Hardie, D.G. AMPK and TOR: the Yin and Yang of cellular nutrient sensing and growth control. Cell Metabolism 2020, 31, 472–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, G.R.; Hardie, D.G. New insights into activation and function of the AMPK. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2023, 24, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharajan, N.; Ganesan, C.D.; Moon, C.; Jang, C.H.; Oh, W.K.; Cho, G.W. Licochalcone D ameliorates oxidative stress-induced senescence via AMPK activation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 7324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Anand, S.K.; Singh, N.; Dwivedi, U.N.; Kakkar, P. AMP-activated protein kinase: an energy sensor and survival mechanism in the reinstatement of metabolic homeostasis. Experimental Cell Research 2023, 428, 113614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Dong, Y.D.; Wu, Y.C.; Wang, Q.X.; Nan, X.; Wang, D.L. AMPK inhibitor BML-275 induces neuroprotection through decreasing cyt c and AIF expression after transient brain ischemia. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2021, 52, 116522. [Google Scholar]

- Spaulding, H.R.; Yan, Z. AMPK and the adaptation to exercise. Annual Review Physiology 2022, 84, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Li, Y.; Fu, Y.; Yang, Y. Research progress of AMP-activated protein kinase and cardiac aging. Open Life Sciences 2023, 18, 20220710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Bai, J.; Wang, X.; Yuan, Q.; Mi, Y.; Zhang, C. Bioactive Lignan Honokiol Alleviates Ovarian Oxidative Stress in Aging Laying Chickens by Regulating SIRT3/AMPK Pathway. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of microRNA biogenesis, mechanisms of actions, and circulation. Front. Endocrinol 2018, 9, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A.; Griffiths-Jones, S.; Ashurst, J.L.; Bradley, A. Identification of mammalian microRNA host genes and transcription units. Genome Res 2004, 14, 1902–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Lee, Y.; Yeom, K.H.; Kim, Y.K.; Jin, H.; Kim, V.N. The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes Dev 2004, 18, 3016–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullen, B.R. Transcription and processing of human microRNA precursors. Mol Cell 2004, 16, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Berg, A.; Mols, J.; Han, J. RISC-target interaction: Cleavage and translational suppression. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008, 1779, 668–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majeski, A.E.; Fred Dice, J. Mechanisms of chaperone-mediated autophagy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2004, 36, 2435–2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Erviti, L.; Seow, Y.; Schapira, A.H.V.; Rodriguez-Oroz, M.C.; Obeso, J.A.; Cooper, J.M. Influence of microRNA deregulation on chaperone-mediated autophagy and α-synuclein pathology in Parkinson’s disease. Cell Death Dis 2013, 4, e545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, X.; Song, M.; He, Z.; Cui, G.; Peng, G.; Dieterich, C.; Antebi, A.; Jing, N.; Shen, Y. A secreted microRNA disrupts autophagy in distinct tissues of Caenorhabditis elegans upon ageing. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 4827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, D.; He, Y.; Meléndez, A.; Feng, Z.; Hong, Q.; Bai, X.; Li, Q.; Cai, G.; Wang, J.; et al. MiR-34 modulates Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan via repressing the autophagy gene atg9. Age 2013, 35, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, B.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Gozali, M.; Wu, D.; Yin, Z.; Luo, D. MiR-23a-depressed autophagy is a participant in PUVA- and UVB-induced premature senescence. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 37420–37435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Xu, J.; Wang, C.; Shi, D.; Yan, Q. miR-23b-3p regulates apoptosis and autophagy via suppressing SIRT1 in lens epithelial cells. J Cell Biochem 2019, 120, 19635–19646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.L.; Hong, C.G.; Yue, T.; Li, H.M.; Duan, R.; Hu, W.B.; Cao, J.; Wang, Z.X.; Chen, C.Y.; Hu, X.K.; et al. Inhibition of miR-331-3p and miR-9-5p ameliorates Alzheimer’s disease by enhancing autophagy. Theranostics 2021, 11, 2395–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbato, C.; Giacovazzo, G.; Albiero, F.; Scardigli, R.; Scopa, C.; Ciotti, M.T.; Strimpakos, G.; Coccurello, R.; Ruberti, F. Cognitive Decline and Modulation of Alzheimer's Disease-Related Genes After Inhibition of MicroRNA-101 in Mouse Hippocampal Neurons. Mol Neurobiol 2020, 57, 3183–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S.Z.A.; Zhao, D.; Hussain, T.; Sabir, N.; Yang, L. Regulation of MicroRNAs-Mediated Autophagic Flux: A New Regulatory Avenue for Neurodegenerative Diseases with Focus on Prion Diseases. Front Aging Neurosci 2018, 10, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyttinen, J.M.T.; Blasiak, J.; Felszeghy, S.; Kaarniranta, K. MicroRNAs in the regulation of autophagy and their possible use in age-related macular degeneration therapy. Ageing Res Rev 2021, 67, 101260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulakat, L.; Chen, H.H. Pro-Senescence and Anti-Senescence Mechanisms of Cardiovascular Aging: Cardiac MicroRNA Regulation of Longevity Drug-Induced Autophagy. Front Pharm 2020, 11, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, H.; He, Z.; Song, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tang, N.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Antebi, A.; et al. Tissue-specific profiling of age-dependent miRNAomic changes in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Wei, D.; Chen, Y.; Chen, L.; Bian, Y.; Shen, Y.; Chen, J.; Pan, Y. Association of astragaloside IV-inhibited autophagy and mineralization in vascular smooth muscle cells with lncRNA H19 and DUSP5-mediated ERK signaling. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2019, 364, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zeng, A.; He, S.; He, S.; Li, C.; Mei, W.; Lu, Q. Autophagy-Related Genes in Atherosclerosis. J Healthc Eng 2021, 2021, 6402206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, A.; Vitucci, D.; Orlandella, FM.; Terracciano, A.; Mariniello, RM.; Imperlini, E.; Grazioli, E.; Orrù, S.; Krustrup, P.; Salvatore, G.; et al. Regular football training down-regulates miR-1303 muscle expression in veterans. Eur J Appl Physiol 2021, 121, 2903–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, S.L.; Hammell, M.; Ambros, V. Robust Distal Tip Cell Pathfinding in the Face of Temperature Stress Is Ensured by Two Conserved microRNAS in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2015, 200, 1201–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinser, H.E.; Pincus, Z. MicroRNAs as modulators of longevity and the aging process. Hum Genet 2020, 139, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvaresh, H.; Paczek, K.; Al-Bari, MAA. ; Eid, N. Mechanistic insights into fasting-induced autophagy in the aging heart. World Journal of Cardiology 2024, 16, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, S.K.; Singh, A.; Saini, M.; Gonzalez-Freire, M.; Leeuwenburgh, C.; Anton, SD. Time-Restricted Eating Regimen Differentially Affects Circulatory miRNA Expression in Older Overweight Adults. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buono, R.; Tucci, J.; Cutri, R.; Guidi, N.; Mangul, S.; Raucci, F.; Pellegrini, M.; Mittelman, S.D.; Longo, V.D. Fasting-Mimicking Diet Inhibits Autophagy and Synergizes with Chemotherapy to Promote T-Cell-Dependent Leukemia-Free Survival. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15, 5870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulas, M.; Akbas, E.; Akbas, S.; Aktemur, G.; Durcanoglu, N.; Aksak, K.; Atalar, A.A.; Yıldırım, S.; Akalin, I. Physiological aspect of apoptosis-regulating microRNAs expressions during fasting. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2023, 27, 2210–2215. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.; Cheng, J.; Yu, F.; Li, H.; Guo, C.; Fan, X. Ghrelin attenuated lipotoxicity via autophagy induction and nuclear factor-κB inhibition. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2015, 37, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Moon, N.R.; Kim, D.S.; Kim, S.H.; Park, S. Central acylated ghrelin improves memory function and hippocampal AMPK activation and partly reverses the impairment of energy and glucose metabolism in rats infused with β-amyloid. Peptides 2015, 71, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Ma, C.; Dai, W.; Fang, E.; Li, W.; Yang, F. Ghrelin attenuates transforming growth factor-beta1-induced pulmonary fibrosis via the miR-125a-5p/Kruppel-like factor 13 axis. Arch Biochem Biophys 2022, 715, 109082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Xu, X.; Yin, M.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L.; Chen, R.; Ni, J. Effects of berberine on blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic literature review and a meta-analysis. Endocrine Journal 2019, 66, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, S.A.; Ross, F.A.; Chevtzoff, C.; Green, K.A.; Evans, A.; Fogarty, S.; Towler, M.C.; Brown, L.J.; Ogunbayo, O.A.; Evans, A.M.; et al. Use of cells expressing gamma subunit variants to identify diverse mechanisms of AMPK activation. Cell Metabolism 2010, 11, 554–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadinejad, R.; Ahmadi, Z.; Tavakol, S.; Ashrafizadeh, M. Berberine as a potential autophagy modulator. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2019, 234, 14914–14926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yang, T.; Mei, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, C.; Bai, X.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Chen, Q. The Potential of Berberine to Target Telocytes in Rabbit Heart. Planta Medica 2014, 90, 84–95. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, N.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Du, Q.; Hao, P.; Li, J.; Cao, X.; Li, L. Berberine Protects Against Simulated Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury-Induced H9C2 Cardiomyocytes Apoptosis In Vitro and Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion-Induced Apoptosis In Vivo by Regulating the Mitophagy-Mediated HIF-1alpha/BNIP3 Pathway. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2020, 11, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Cao, X.; Hao, P.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Gao, C.; Li, L. Berberine attenuates mitochondrial dysfunction by inducing autophagic flux in myocardial hypoxia/reoxygenation injury. Cell Stress and Chaperones 2020, 25, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.L.; Yin, Y.L.; Ping, S.; Yu, H.Y.; Wan, G.R.; Jian, X. Li, P. Berberine promotes ischemia-induced angiogenesis in mice heart via upregulation of microRNA-29b. Clin Exp Hypertens 2017, 39, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Yu, S.; Lin, C.; Dong, D.; Xiao, J.; Ye, Y.; Wang, M. Roles of flavonoids in ischemic heart disease: Cardioprotective effects and mechanisms against myocardial ischemia and reperfusion injury. Phytomedicine 2024, 126, 155409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grewal, A.K.; Singh, T.G.; Sharma, D.; Sharma, V.; Singh, M.; Rahman, M.H.; Najda, A.; Walasek-Janusz, M.; Kamel, M.; Albadrani, G.M.; et al. Mechanistic insights and perspectives involved in neuroprotective action of quercetin. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 140, 111729. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, B.; Chung, J.W.; Bae, H.R.; Choi, J.S.; Kim, C.M.; Kim, N.D. Humulus japonicus extract exhibits antioxidative and anti-aging effects via modulation of the AMPK-SIRT1 pathway. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine 2015, 9, 1819–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benameur, T.; Soleti, R.; Porro, C. The Potential Neuroprotective Role of Free and Encapsulated Quercetin Mediated by miRNA against Neurological Diseases. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khater, S.I.; El-Emam, M.M.A.; Abdellatif, H.; Mostafa, M.; Khamis, T.; Soliman, R.H.M.; Ahmed, H.S.; Ali, S.K.; Selim, H.M.R.M.; Alqahtani, L.S.; et al. Lipid nanoparticles of quercetin (QU-Lip) alleviated pancreatic microenvironment in diabetic male rats: The interplay between oxidative stress - unfolded protein response (UPR) - autophagy, and their regulatory miRNA. Life Sci 2024, 344, 122546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa-Maria, I.; Alaniz, M.E.; Renwick, N.; Cela, C.; Fulga, T.A.; Van Vactor, D.; Tuschl, T.; Clark, L.N; Shelanski, M.L.; McCabe, B.D.; et al. Dysregulation of microRNA-219 promotes neurodegeneration through post-transcriptional regulation of tau. J Clin Investig 2015, 125, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konovalova J, Gerasymchuk D, Parkkinen I, Chmielarz P, Domanskyi A. Interplay between MicroRNAs and Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 6055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Yi, P.; Yi, M.; Tong, X.; Cheng, X.; Yang, J.; Hu, Y.; Peng, W. Protective Effect of Quercetin against H2O2-Induced Oxidative Damage in PC-12 Cells: Comprehensive Analysis of a lncRNA-Associated ceRNA Network. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020, 2020, 6038919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Xu, Q.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liang, T. Luteolin Ameliorates Hepatic Steatosis and Enhances Mitochondrial Biogenesis via AMPK/PGC-1alpha Pathway in Western Diet-Fed Mice. Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology 2023, 69, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, A.W.; Sun, C.; Li, H.T.; Zhong, K.; Zeng, X.H.; Gu, Z.F.; Li, B.Q.; Zhang, X.N.; Gao, J.L.; Chen, T.X. Puerarin is a promising compound for improving the longevity of Drosophila melanogaster by activating autophagy. Food & Function journal 2023, 14, 2149–2161. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.H.; Gong, D.; Chen, L.Y.; Zhang, M.; Xia, X.D.; Cheng, H.P.; Huang, C.; Zhao, Z.W.; Zheng, X.L.; Tang, X.E.; et al. Puerarin promotes ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux and decreases cellular lipid accumulation in THP-1 macrophages. Eur J Pharmacol 2017, 811, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, C.H.; Shen, Z.Q.; Wang, T.W.; Kao, C.H.; Teng, Y.C.; Yeh, T.K.; Lu, C.T.; Yeh, T.K.; Lu, C.K.; Tsai, T.F. Hesperetin promotes longevity and delays aging via activation of Cisd2 in naturally aged mice. Journal of Biomedical Science 2022, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.Y.; Yu, J.H. Hesperidin enhances intestinal barrier function in Caco-2 cell monolayers via AMPK-mediated tight junction-related proteins. FEBS Open Bio 2013, 13, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chang, C. Hesperetin ameliorates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury via the miR-410/SOX18 axis. J Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2020, 34, e22588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, N.B.; Bostanci, A.; Sadi, G.; Dönmez, M.O.; Uludag, M.O.; Demirel-Yilmaz, E. Resveratrol and regular exercise may attenuate hypertension-induced cardiac dysfunction through modulation of cellular stress responses. Life Sciences 2022, 96, 120424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yang, Y.; Guo, J.; Ma, T.; Hu, Y.; Huang, L.; He, Y.; Xi, J. Resveratrol Inhibits Zinc Deficiency-Induced Mitophagy and Exerts Cardiac Cytoprotective Effects. Biological Trace Element Research 2024, 202, 1669–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yun, Q.; Du, R.; Li, L.; Li, Y.; Gao, Q. Resveratrol alleviates hyperglycemia-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis via enhancing SIRT1 expression. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao 2024, 44, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, A.; Ezawa, Y.; Asano, D.; Kanamori, T.; Morita, A.; Kashihara, T. Sakamoto K.; Nakahara, T. Resveratrol dilates arterioles and protects against N-methyl-d-aspartic acid-induced excitotoxicity in the rat retina. Neuroscience Letters 2023, 793, 136999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardi, F.; Khasraghi, L.B.; Shahbakhti, N.; Salami Naseriyan, A.; Najafi, S.; Sanaaee, S.; Alipourfard, I.; Zamany, M.; Karamipour, S.; Jahani, M.; et al. An interplay between non-coding RNAs and gut microbiota in human health. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2023, 201, 110739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Chen, J.; Li, Y. ; Kuang, Z.; Dende, C.; Raj, P.; Quinn, G.; Hu, Z.; Srinivasan, T.; et al. The gut microbiota reprograms intestinal lipid metabolism through long noncoding RNA Snhg9. Science. 2023, 381, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Liu, Y.; Yan, R.; Wang, R.; Zhang, P.; Bai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ren, Y.; Li, Y.; Jiang, X.; et al. Butyrate suppresses atherosclerotic inflammation by regulating macrophages and polarization via GPR43/HDAC-miRNAs axis in ApoE−/− mice. PLoS ONE. 2023, 18, e0282685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, S.T.; Abdullah, S.R.; Hussen, BM.; Younis, YM.; Rasul, MF.; Taheri, M. Role of circular RNAs and gut microbiome in gastrointestinal cancers and therapeutic targets. Noncoding RNA Res. 2023, 9, 236–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanigawa, K.; Misono, S.; Mizuno, K.; Asai, S.; Suetsugu, T.; Uchida, A.; Kawano, M.; Inoue, H.; Seki, N. MicroRNA signature of small-cell lung cancer after treatment failure: Impact on oncogenic targets by miR-30a-3p control. Mol Oncol 2023, 17, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Jing, W.; Jin, S.; Wang, B. Circ_0088194 regulates proliferation, migration, apoptosis, and inflammation by miR-30a-3p/ADAM10 axis in rheumatoid arthritis fibroblastic synovial cells. Inflammation 2023, 46, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, L.; Chen, S.; Du, F.; Li, S.; Zhao, L.; Wang, X. Nutrient starvation elicits an acute autophagic response mediated by Ulk1 dephosphorylation and its subsequent dissociation from AMPK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011, 108, 4788–4793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, M.A.; Biggers, C.D.; Li, P.A. Rapamycin treatment increases hippocampal cell viability in an mTOR-independent manner during exposure to hypoxia mimetic, cobalt chloride. BMC Neurosci. 2018, 19, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannan, F.M.; Elajnaf, T.; Vandenberg, L.N.; Kennedy, S.H.; Thakker, R.V. Hormonal regulation of mammary gland development and lactation. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2023, 19, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhang, Q. miR-34a and endothelial biology. Life Sci. 2023, 330, 121976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.E.; Fu, T.; Seok, S.; Kim, D.H.; Yu, E.; Lee, K.W.; Kang, Y.; Li, X.; Kemper, B.; Kemper, J.K. Elevated microRNA-34a in obesity reduces NAD+ levels and SIRT1 activity by directly targeting NAMPT. Aging Cell 2013, 12, 1062–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, K.; Chen, X.; Meng, H.; Song, M.; Wang, Y.; et al. Transcriptional activation of microRNA-34a by NF-kappa B in human esophageal cancer cells. BMC Mol Biol. 2012, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Yin, B.; Guo, S.; Umar, T.; Liu, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Zahoor, A.; Deng, G. Enhanced Expression of miR-34a Enhances Escherichia coli Lipopolysaccharide-Mediated Endometritis by Targeting LGR4 to Activate the NF-kappaB Pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021, 1744754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wei, X.; He, J.; Cao, Q.; Du, D.; Zhan, X.; Zeng. Y.; Yuan, S.; Sun, L. The comprehensive landscape of miR-34a in cancer research. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2021, 40, 925–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).