1. Introduction: LambdaCDM Paradigm

In astronomy and cosmology, as well as in theoretical physics, dark matter is a hypothetical form of matter that does not participate in electromagnetic interaction and therefore is inaccessible to direct observation [

1]. There is a lot of dark matter by mass (many times more than visible, baryon matter), but given that it does not interact with the substance we know, the question arises about its composition. There is a wide range of suggestions about dark matter composition. They can be neutrino either weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs), massive (astrophysical) compact halo objects (MACHOs), or even ultralight axion-like particles [

2,

3,

4]. The latter are so light that their wavelength can be commensurate with the width of the galaxy and even the universe. For example, the mass of these particles is of the order of

eV [

5], or about

kg, then the wavelength is about

m only on two orders smaller the Observable Universe. On the other hand, WIMPs, as expected for a new particle, are in the 100 GeV mass range and interact via the electroweak force [

1,

3,

6].

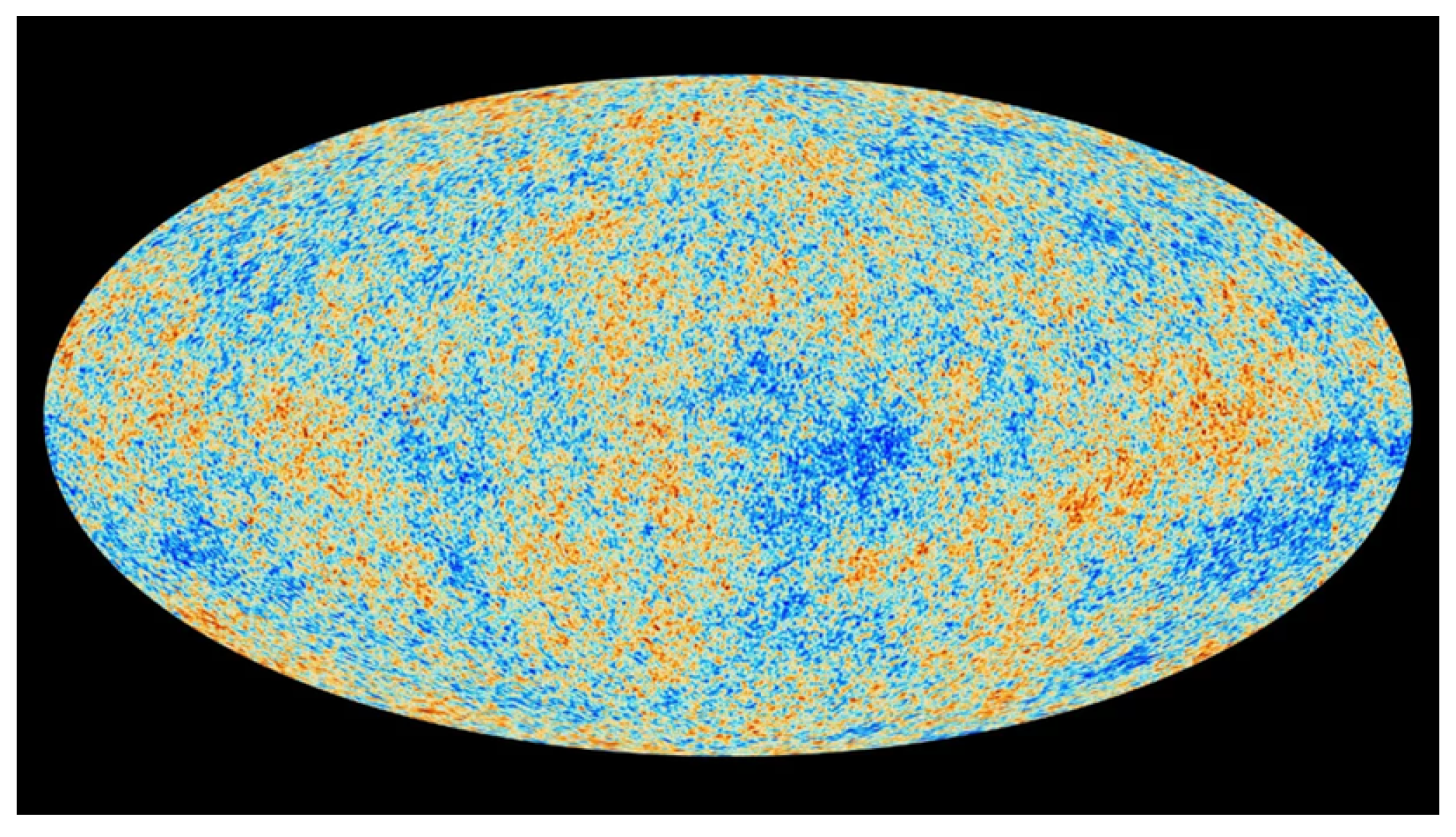

The search and registration of WIMPs, MACHO, or axions have not yielded positive results so far. It makes sense to look at the Lambda Cold Dark Matter (LambdaCDM) paradigm in more detail. The LambdaCDM consists of two parts. The CDM is a proposed type of dark matter particle that moves slowly, slower than the speed of light, and interacts weakly with ordinary matter and electromagnetic radiation. A possible existence of such dark matter particles can be supported by the cosmic microwave background,

Figure 1, at a temperature of 2.725 K [

7].

As for the part concerning the Lambda term, it appears in Einstein’s general relativity. An important remark is about the tensor

. It can be viewed as the energy-momentum tensor of some static cosmological scalar field. The parameter

is a cosmological constant characterizing the state of the cosmic vacuum, which is introduced in the general theory of relativity to characterize either the spherical geometry of the universe or hyperbolic, depending on the sign of

. The Planck collaboration in their observations emphasize [

8,

9,

10] that the spatial curvature of the universe is almost zero. The Lambda term is almost zero. That is, the geometry is Euclidean, and the universe is homogeneous and isotropic on large scales.

The cosmological principle states that the spatial distribution of matter in the universe is homogeneous and isotropic when viewed on a sufficiently large scale. In this view, let us first evaluate the mass density of the visible universe. With its diameter

d equal to about 28.5 gigaparsecs [

11], or

, its volume is as follows

. Hereafter we will adhere to SI units.

The total mass of visible matter in the universe according to different sources [

12,

13,

14] is about

to

kg. We take the average

kg. From here we may evaluate the mass density of the visible matter filling the visible universe

The Lambda-Cold Dark Matter (

CMD) paradigm states that the spatially flat universe is filled, in addition to ordinary baryon (visible) matter, with dark energy (described by the cosmological constant

in Einstein’s equations) and cold dark matter at the temperature of the cosmic background radiation [

8,

9,

10],

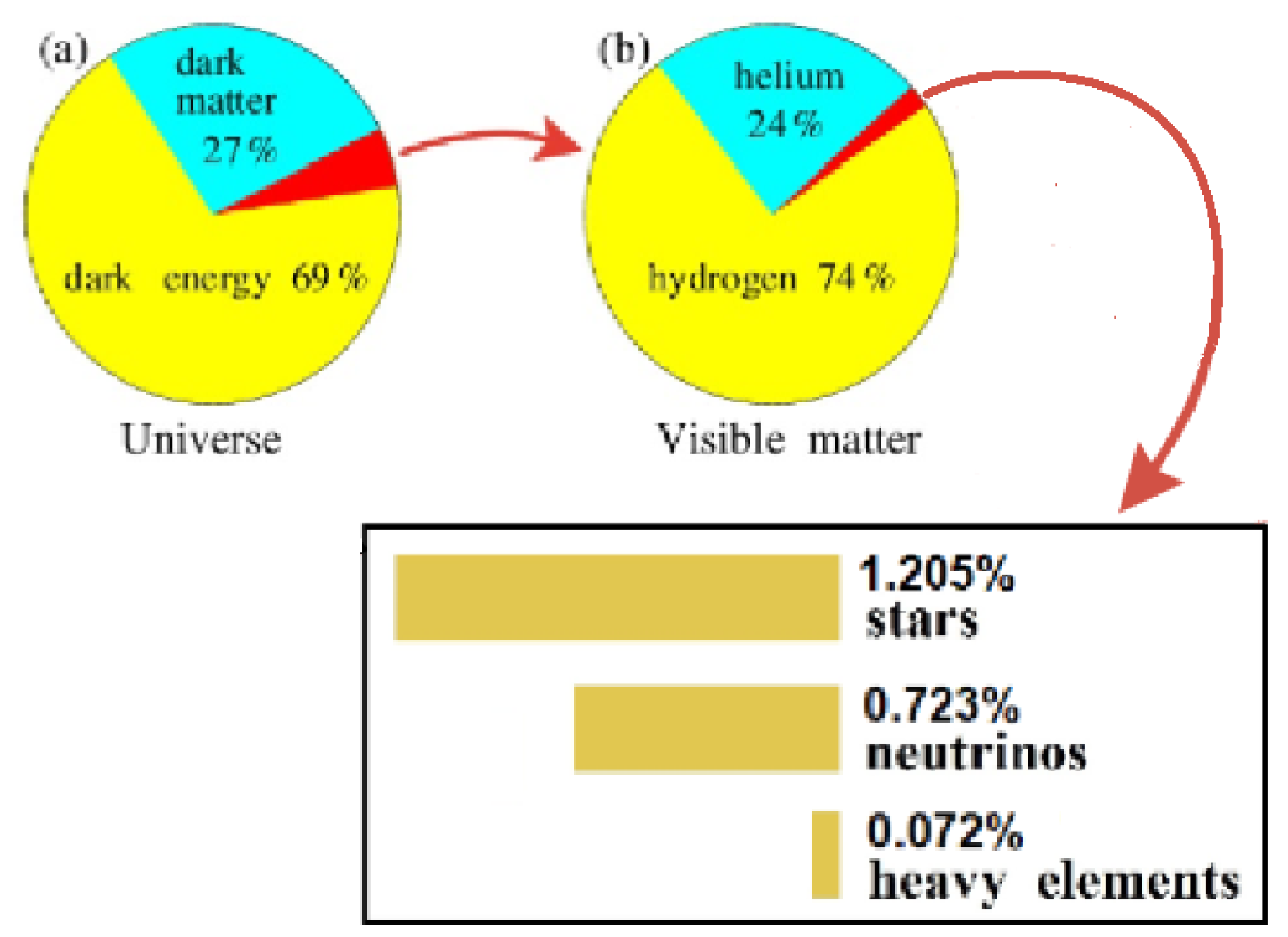

Figure 2. From the Friedmann equation [

15], when the spatial curvature

is almost zero, one can evaluate the following Hubble parameter:

Here, is the scale factor, G is the gravitational constant, is the average density, is the cosmological constant, and is the Hubble expansion parameter.

The average density,

, at

vanished (it is so in the case of the spatially flat geometry of the universe [

10]), is close to the critical density calculated according to the following formula [

16,

17,

18]:

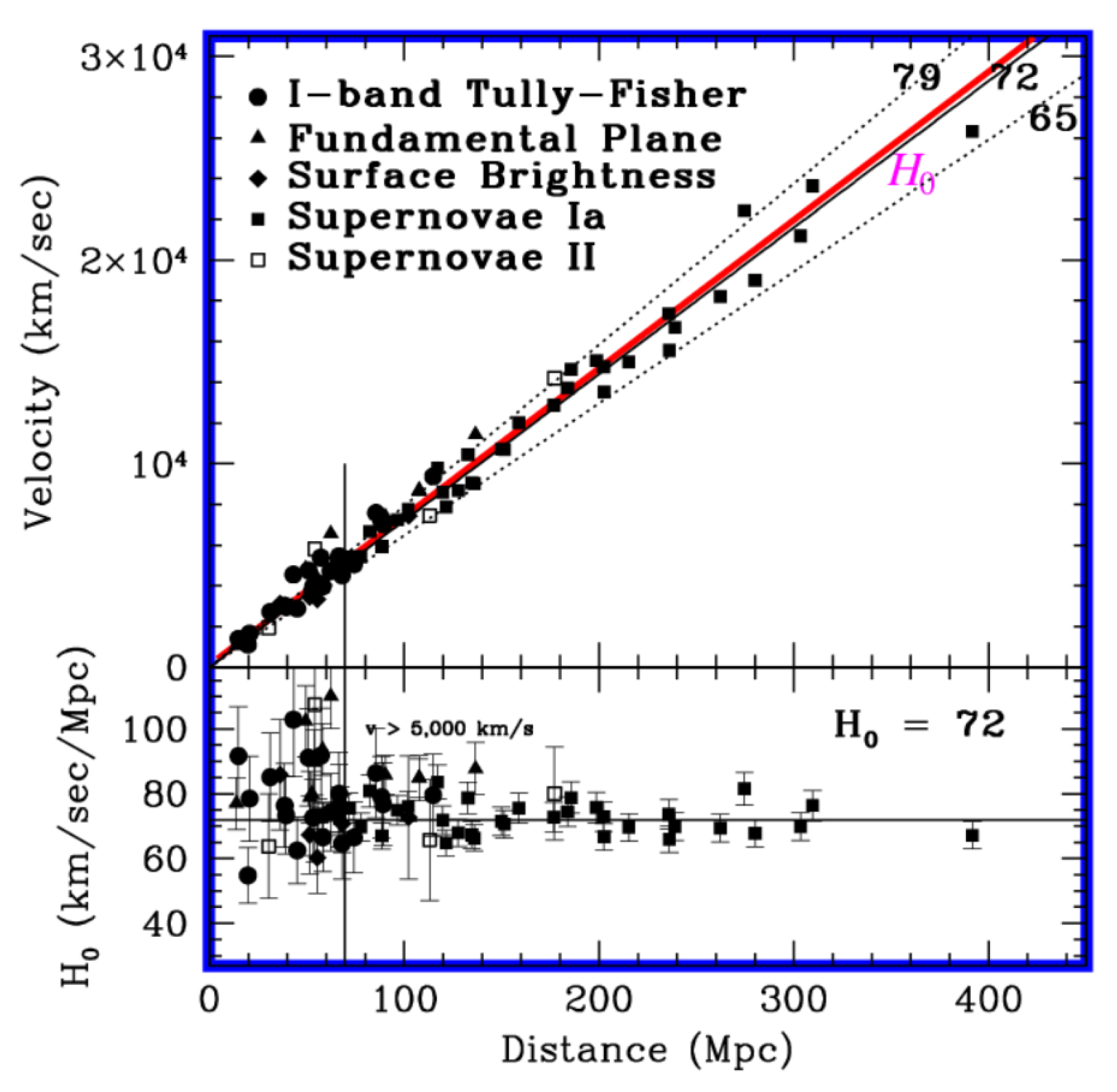

Here

is the gravitational constant. The Hubble parameter

expressed in units adopted in astrophysics [

15] is about

[

19],

Figure 3. Or it is

being represented in SI unit [

20].

Now, we can estimate the presence of visible matter and the matter composing the critical density (dark matter and energy) in the observed universe as a percentage

So, the visible (baryon) matter is only about

in the visible universe. The remaining

are the dark mass and dark energy. It is exactly what our instruments do not detect, except that the dark matter has gravity. Qualitatively, the distribution of dark energy, dark matter, and visible matter in the universe can be represented in pie charts, as shown in

Figure 2. In particular, at known percent distributions of dark energy and dark matter, one can evaluate their densities:

The first pie chart (a) in

Figure 2 shows the presence of dark energy, dark matter, and visible matter that make up the universe. It can be seen that, against the background of dark energy and dark matter, visible matter is only a small part. Figuratively speaking, if dark matter and energy are the bulk of the boundless ocean, then visible matter appears to be a fleeting foam on it spreading apart. The following pie chart (b) shown in

Figure 2 demonstrates the presence of various atomic elements within this fleeting baryon foam. It can be seen that these elements are mainly hydrogen and helium. If hydrogen is the carrier of protons, then helium is the carrier of both protons and neutrons. In general, they account for up to 98% of all visible matter, which washes the entire universe in a thin layer. The remaining two percents are accounted for by the stars, neutrinos, and other heavy elements composing the periodic table of chemical elements. Life, which needs the presence of many heavy elements, ranging from carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, sodium, potassium, calcium, etc., appears as thin inclusions on this baryon foam. In turn, intelligent life and an active form of consciousness are rare precious pearls.

2. The Lorentz Gauge Is a Door to the Invisible World of Dark Energy and Dark Matter

Before we go forwards, it is needed to give a short remark about an invisible world following from the Lorentz gauge applied to the energy-momentum density tensor. The energy-momentum density tensor, written in the quaternion basis [

21], looks as follows:

Here the energy and momentum densities,

and

, containing a scalar field

reads:

The energy and momentum densities have the same dimension [] representing by itself the pressure. For that reason, the momentum is additionally multiplied by the speed of light. The term in both expressions is the Lorentz factor. At the energy and momentum densities, and , given, the term arbitrary chosen defines their ambiguous state. The dimension of is []. This dimension is seen to be congruent to that of the cosmological term, which has the dimension [length].

Since we deal with here the two forms of motion - gravity-mechanical and electromagnetic - their energy and momentum are defined up to the arbitrary scalar field represented by the difference . One scalar field, , relates to the gauge transformation of the massive medium, and other fields, , deal with that of the massless medium, the electromagnetic field (EM field), carriers of which are EM quanta with zero mass.

The terms

and

in Eq, (

6) are quaternions:

Now, by applying the generating differential operator

to the energy-momentum density tensor (

6), we come to the gravitomagnetic tensor [

21], where all terms along the main diagonal vanish. The condition of vanishing the diagonal terms follows from the demand:

which is called the Lorentz gauge.

The arbitrary scalar field

figured in the energy-momentum density tensor (

6), consists of the difference of two components

and

, which submit to the wave equation (

11) loaded by the disturbing from the visible matter term as the 4D divergence of the energy-momentum density. This equation looks as follows:

In fact, equating to zero in this expression, we reject all terms lying on the main diagonal of the gravitomagnetic tensors [

21], The scalar product of the 4D differential operator

by the 4-vector

defines the 4-divergence

. From here, we can conclude that the 4D divergence of the energy-momentum tensor representing our visible world has an effect on the invisible world. Note that since

has the dimension of the energy density, J·m

, the term

has the dimension J·m

. From here, it follows that

has the dimension J·m

= kg·s

. Accurate to the multiplier J (energy), the scalar field is seen to be like the cosmological constant

. Remind that the dimension of the cosmological constant is m

.

The scalar field

is extra disturbance of the electromagnetic field. This scalar field is massless. While the scalar field

relating to the gravitomagnetic part of the energy-momentum density tensor is mass loaded. The difference between the scalar fields

and

is the same as the difference between the Lorentz force,

, and its gravitomagnetic counterpart

. The cardinal difference is due to the change of the electric charge

q by mass

m. Following the above remark, let us rewrite the first term in Eq. (

12) by adding and subtracting the term

:

We declare that the part covered by brace (a) vanishes:

The first equation covered by brace (a

) is the Klein-Gordon equation that obeys the "on-shell condition" [

22]

. Further, we rewrite this equation by extracting two Dirac operators multiplied by each other, as shown in the bracket (a

). Here, the multiplication of these operators yields the sum

. Note that

, where

is the Minkowski metric with signature

and

. Thus,

vanishes.

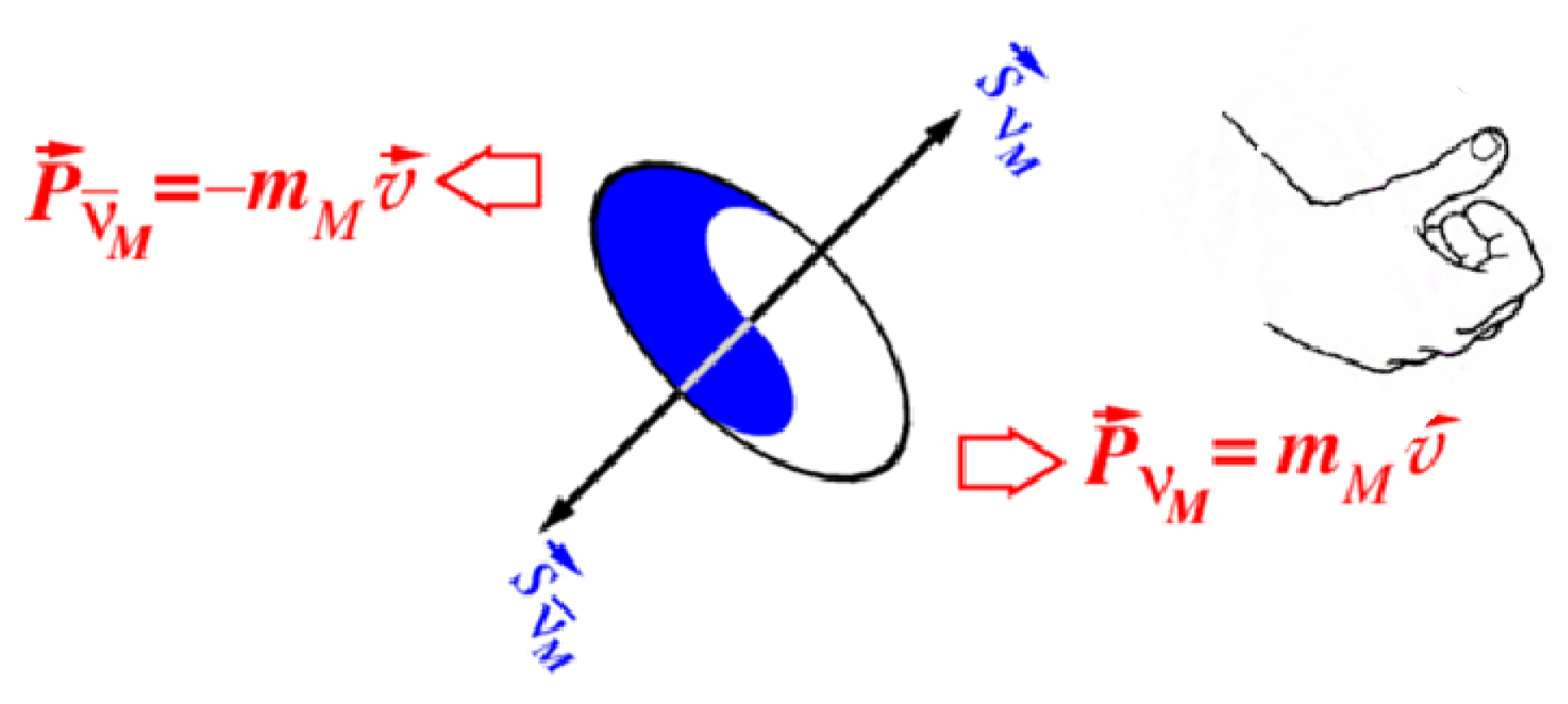

The multiplication of two Dirac operators under a brace (a

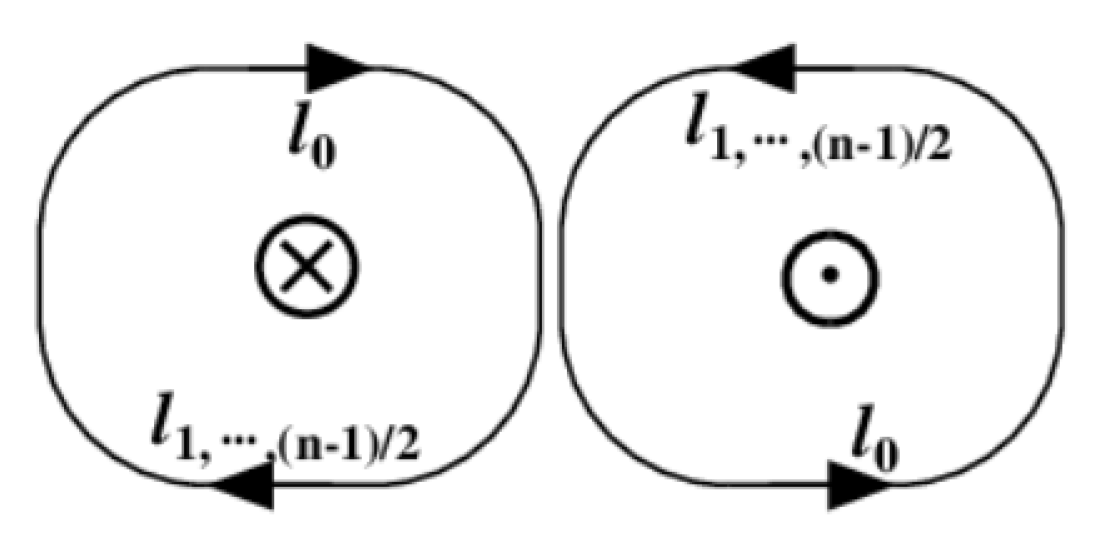

) describes the action of a coupled pair of particle and antiparticle, each with a half-integer spin. This sum is a boson with an integer spin, the behavior of which is described by the Klein-Gordon equation. This equation states that (a) both fermions rotate about the common mass center; (b) the bonded fermions have zero charge; (c) the bonded fermions have an integer spin equal to zero; and (d) they have equal masses. See

Figure 4. In the above-described case, the antiparticle identically coincides with the particle. They are truly neutral fermions – called Majorana particles [

23].

2.1. Relict Majorana Fermion Is a Neutrino

As was remarked earlier, both WIMPs and ultralight axions have no experimental supporting until now. It makes sense to choose light particles with a larger wavelength so that the nearest particles overlap by their de Broglie wavelengths. Majorana fermions [

23] stemming from Eq. (

14) can be these particles. It is great that these fermions are also their own antifermions. The formulas for finding the Majorana fermion mass,

, contain the key parameters, which are the Planck constant, the dark matter critical density distribution, and the fermion most probable speed at the temperature of the relict cosmic radiation,

= 2.725 K.The set of the formulas is as follows:

The thermal velocity of the fermion

required to calculate the wavelength according to the de Broglie formula () is estimated as the most probable velocity within the Maxwell velocity distribution according to Eq. (). Let me remind you that the Maxwell–Boltzmann describes the statistical behavior of the parameters of ideal gas particles [

25]. From formulas, (

15)-(), one can extract the formula calculating the Majorana fermion mass:

This evaluation of the Majorana fermion mass is in good agreement with the neutrino mass experimentally measured and shows about 0.04 eV expressed in the energetic units.

Estimates of the measured neutrino masses performed by different collaborations,

Table 1, are given, as a rule, in the energetic units expressed in the electronVolt. Expressed in the electronVolt the evaluation given in (

18) returns the result about 0.04 eV, which shows a good agreement with that measured by the KamLAND-Zen Collaboration in 2023 [

26].

At the Majorana fermion mass calculated by Eq. (

18), one can evaluate its thermal speed as follows from Eq. ():

This speed is seen to be on 10 times smaller only than the speed of light. However, if we evaluate its momentum,

, then one can see that it is minuscule. Note that the speed () relates to the rotation of the fermions about their general mass center, see

Figure 4, as the speed

relates to the rotation of the electron on the first orbit about the proton. Here

is the fine structure constant,

The formula (

18) computing the Majorana fermion mass is seen to contain only three key parameters – the Planck constant,

h, the dark matter critical density distribution,

, and the temperature,

= 2.725 K, of the relict cosmic radiation. One may rewrite Eq. (

18) in a more physically clear representation by extracting the dark matter critical density distribution outside the root:

The second term here is a volume

occupied by the Majorana fermion. It is easy to estimate that one cubic centimeter can contain about 40 thousand M-fermions. One can evaluate the edge length of this cube:

This length is seen to be the de Broglie wavelength () computed for the M-fermion. From here, it follows that the length m determines the characteristic size of a resonator, within which the M-fermion has a steady standing wave.

2.2. Majorana Fermion Generations

All formulas, (

20)-(

22), computing key parameters of M-fermion, are based on extracting of the five-degree root. In these expressions, only the extraction of the amplitude factor is shown. There is also the phase factor conditioned by the degree of the root. Let us look the computation of the elementary volume (

21) at existing the phase factor:

Here the number

k runs the integer quantities,

. So the under-root exponent is equal to unit always for all integers

k. However, extracted from the root, the number

k under the exponent acquires the divider 5. For that reason, the extracted exponent has different values when

k runs 0, 1, 2, 3, 4. The results of these computations are shown in

Table 2. The calculated values are shown as accurate to the third sing after dot.

All values at

and at

are complex conjugated. By summing these values with each other, we get the result shown in

Table 3. Here the doubled cosines resulting from summing the exponent with the argument

and its conjugated exponent having the argument

, return real weights for all

l ranging 0, 1, 2. Observe that the sum of all real weights at that is zero. It is due to that one weight in

Table 3 at

having a negative value. Surprisingly, the weights at

and 2 submit to the law of the golden ratio. Their sum is equal to

.

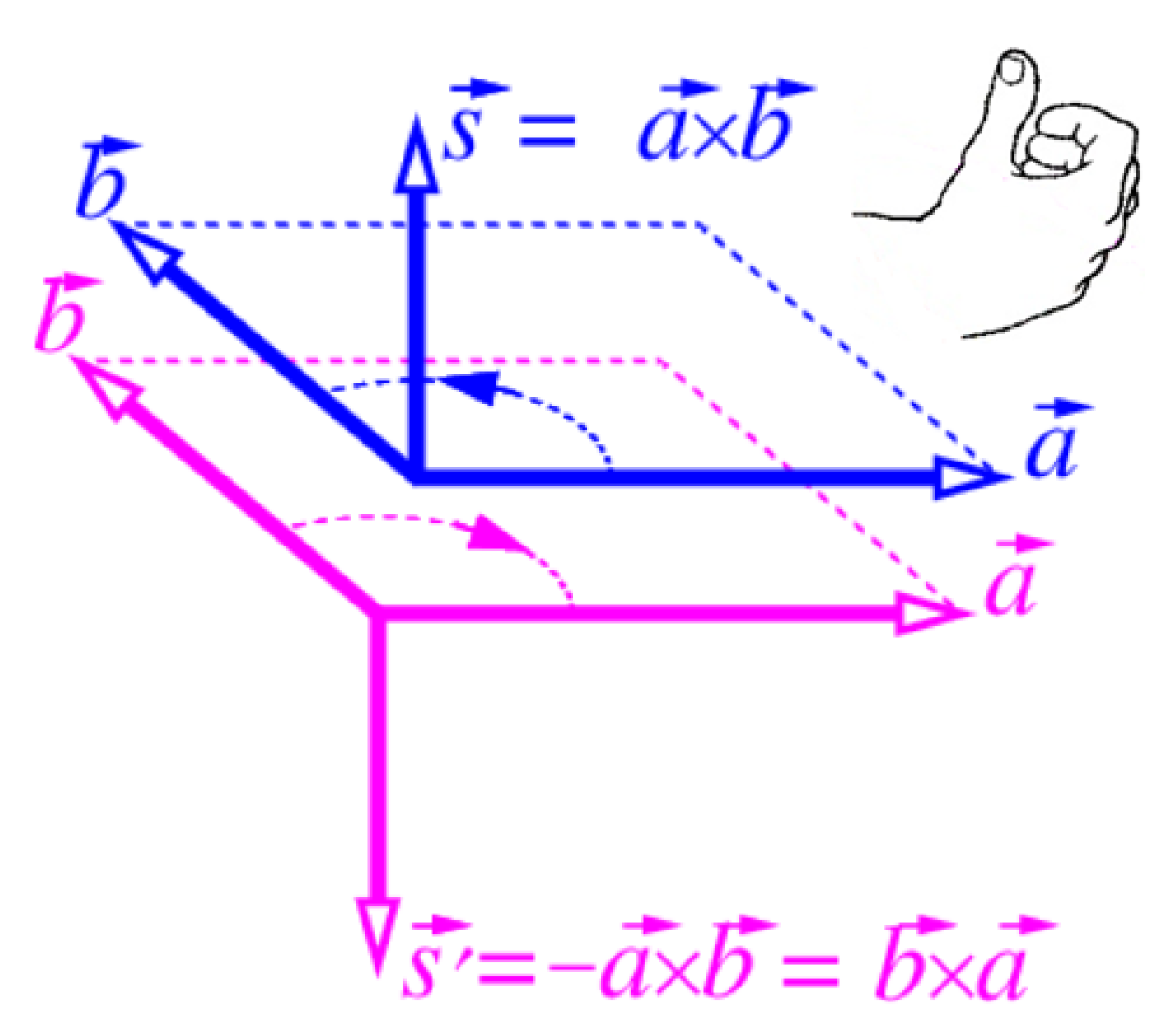

All these weights determine different values of the elementary volume

(

23) depending on these weights. Because of the existence of the negative weight at

the one elementary volume is negative. The negativity of volume should not be confusing, if we recall the rule of vector product of vectors. The vector product of two vectors gives either a positive or a negative result, depending on the order in which they follow in this product; see

Figure 5. This result determines the orientation of the normal vector constructed on the area S obtained from the vector product. And as a result, the volume sign built on this site also depends on this.

A more delicate question concerns the negativity of the fermion mass. If the elementary volume has negative values, then the same applies to the sign of mass:

Negative mass is not surprising in scientific discussions. Publications relating to the manifestation of effective negative masses, both in the experimental observations and theoretical investigations, are in the open press [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

We note, however, that an impulse equal to the product of its mass by velocity is the primary characteristic of a particle,

Figure 4, whereas mass is just a coefficient of proportionality. Therefore, the negativity of the mass can be delegated to a change in the direction of the fermion’s rotation speed.

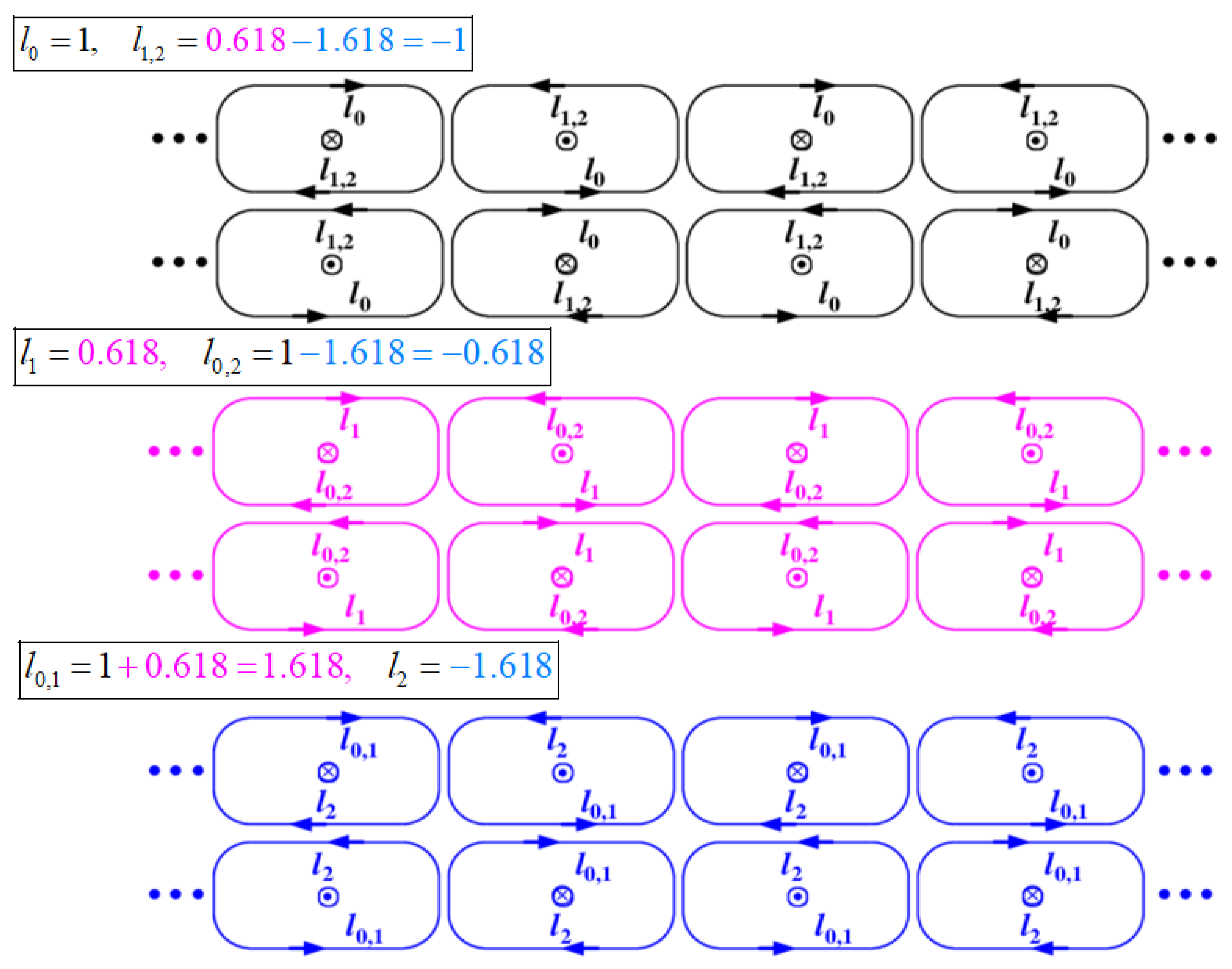

Let’s return to the table of three mass generations of Majorana fermions. One can see that the sum of these numbers is zero. Each number shown in the table is always equal to the sum of the other two numbers taken with the opposite sign. It follows that it is possible to create three different wave generations of Majorana fermions, shown on

Figure 6.

There are three wave modes for three different combinations of numbers , , , such that along each closed path their sum is zero. This drawing is based on the drawing modes of electromagnetic waves formed in microwave waveguides. A discerning viewer may see some similarities with Feynman diagrams, in which the arrows oriented from left to right symbolize particles and the arrows oriented in the opposite direction symbolize antiparticles.

These wave modes symbolize forming Bose-Einstein condensates composed of paired Majorana fermions. It leads to the conclusion that dark matter appears to be a superfluid substance. As one can see, there are three different condensates, differing in the weights involved in the mass exchange. Or, more strictly speaking, the mass circulations occur along closed circuits with equal speed.

These diagrams reveal many similarities with those of electric and magnetic modes supporting in resonators or waveguides constructed in the Cartesian coordinate system. The oscillations arising along such a waveguide are standing waves, with the average mass of the paired M-fermions being zero. These diagrams show some signs typical for the Feynman path diagrams. Particles having positive masses move from the left to the right. Particles having negative masses move in the opposite direction.

By the way, we will note Farnes in his article published in the Astronomy and Astrophysics [

40], has shown that dark matter can contain negative mass particles. He emphasizes that dark matter can represent itself as a strange, dark fluid with negative masses. It is a hypothetical form of matter possessing a type of negative gravity that repels all other material around it. Since the average mass of all generations of dark matter particles is zero, such a strange dark fluid does not repel and attract all other material around it. But since this fluid is superfluid it is a perfect medium that does not offer resistance to moving baryon matter.

We note that as well as unmoved superfluid helium does not affect rotating normal spin-mass vortices in it [

41], this superfluid medium cannot drag rotating baryon matter with it. Therefore, the guess that dark matter can drag away with itself the orbital speed of galaxy arms is false. This unmoved superfluid medium has no effect on rotating visible matter. It also has no inhibitory effect. Therefore, the flat profile of the orbital speed of the galaxy arms is due solely to rotating these arms in the superfluid medium, which is unmoved. Let us consider this statement in detail.

3. Decreasing and Flat Profiles of the Orbital Speed

To describe the orbital speed of the spiral galaxy arms about its core, let us begin with the vorticity equation [

42]:

underlying the computation of the orbital speed. Here

is the kinetic viscosity. Its dimension is [length

/time]. Next we pass to the cylindrical coordinate system., where a vortex tube is under consideration. It in its cross-section is oriented along the

z-axis and its center is placed in the coordinate origin of the plane

. Eq. (

25), written down in the cross-section of the vortex, get a view:

The solution of this equation looks as follows:

Here having the dimension [length/time] is the integration constant.

By assuming that

is a positive constant, the integral of

by

gives

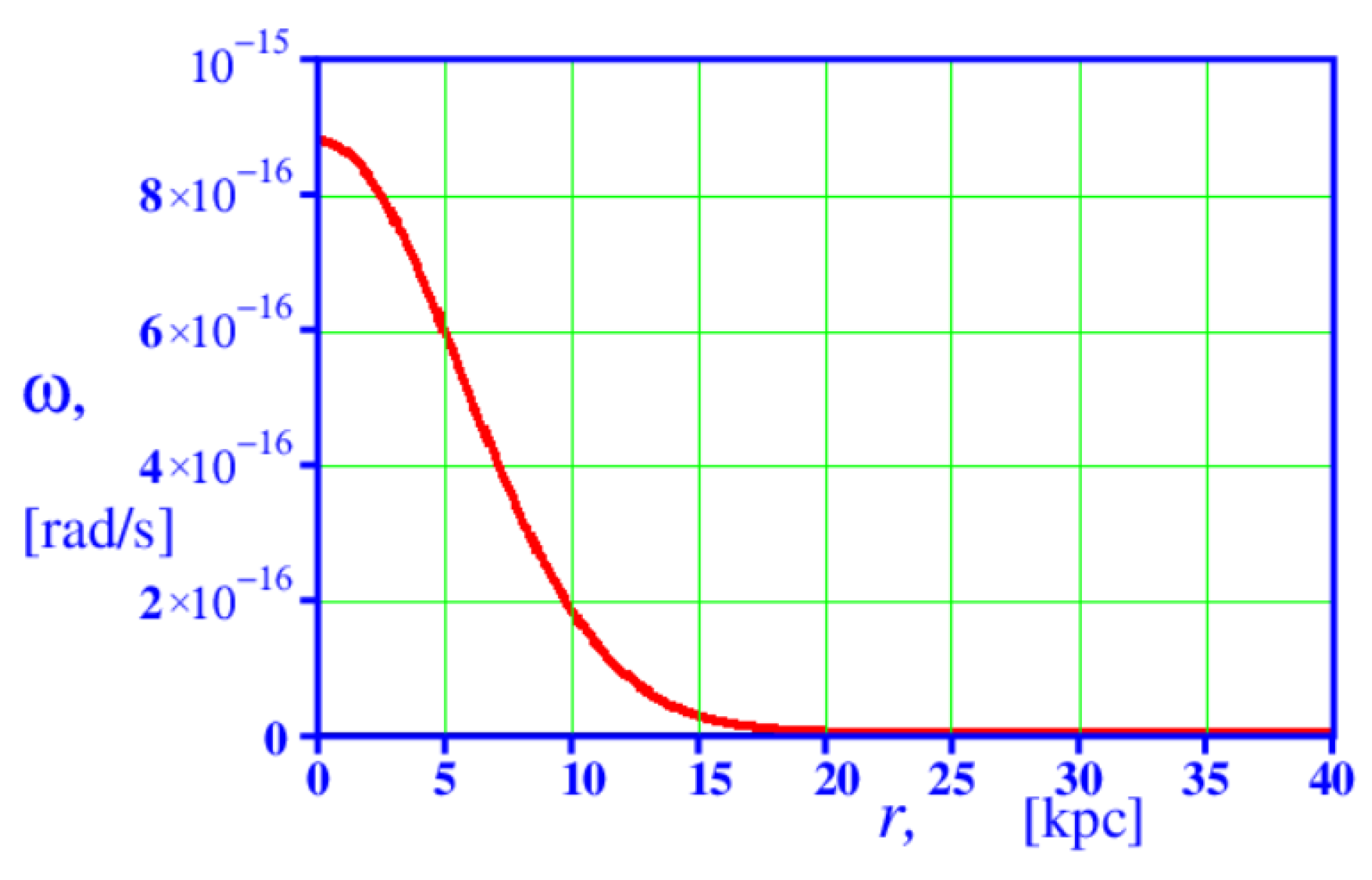

. We have the following simple result:

Note that the result

divided by

has dimension [1/time]. So,

is the vorticity measured in radian per time, see

Figure 7.

The vorticity drawn in this figure is based on parameters taken from measured observations of our galaxy, the Milky Way. Namely, the time of the sun’s revolution around the center of the galaxy is . From here it follows that the frequency of orbital revolution is (one year contains 31536000 s). Besides, we take kpc. This value is close to the size of the bulge, which is about 3.5 kiloparsecs.

Now we need to calculate the orbital speed about the vortex core. This formula reads:

To have the dimension of this expression equal to [length/time], the parameter should have the dimension of [length]. In this case, the calculated variable will have the dimension of speed. Further, we consider two variants of choosing the parameter : (a) is the distance r; (b) is the parameter .

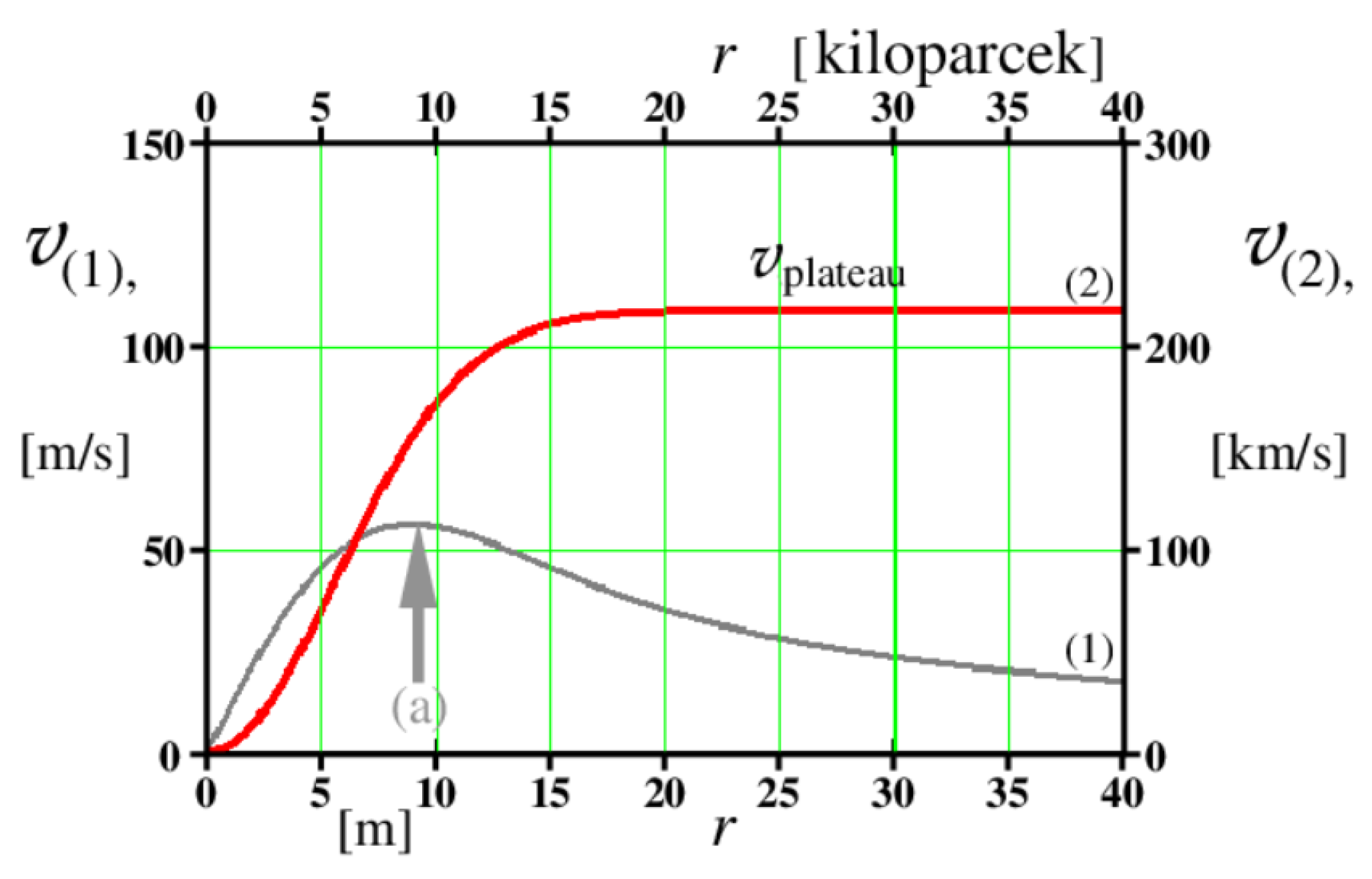

3.1. The Lamb-Oseen Decreasing Profile of the Orbital Speed

Substituting into Eq. (

29) instead

the distance

r we get the orbital speed

decreasing to zero as

r goes to infinity. The speed

as a function of

r at

is shown in

Figure 8. This function is seen to sharply grow from the origin (from the tornado eye) up to its wall. Thereafter, it begins to decrease monotonically and vanishes when

r goes to infinity. As

t tends to infinity, the tornado wall increases to infinity, and the orbital speed goes to zero as well. This function gives a qualitative description of the wind speed if the medium is viscous.

3.2. Flat Profile of the Orbital Speed

If the medium has no viscous but superfuid, then there should be no monotonic decrease in the orbital speed with r increasing.

We will not reject viscosity. However, we believe that the average viscosity vanishes over time, but its variance is not zero [

21,

43,

44]:

These expressions describe an exchange of energy with the superfluid medium, with the invisible world. It should be noted that since the viscosity coefficient depends on time but does not contain spatial variables, the invisible medium is non-local and is represented by the Bose-Einstein condensates. The first expression states that the medium has no, on average, the viscosity. Thus, the integrals in Eq, (

27) return

From the second expression, it follows that the exchange occurs regularly, both with the return of energy and with its acquisition randomly.

Let the medium be superfluid. Then

in Eq. (

29) is a constant, and let it be

. Then:

The integration constant

is said above to have the dimension [length

/time]. Looking at Eq. (

28), we admit that the constant

is

. Now formula (

33) takes the form:

Above, it was said that

and

kpc. Their multiplication on each other and doubled gives:

This number almost close to the speed of the Sun revolving about the core of the Milky Way. The orbital speed

versus

r expressed in kiloparsec is drawn in

Figure 8. The fact that the orbital speed has a flat profile at large

r follows from rotating visible baryon matter in an invisible superfluld medium. The latter represents the unmoved dark matter filling the whole halo of the galaxy. The unmoved superfluid medium does not provide any resistance for rotating baryon matter [

41,

45]. Therefore, there is no any reason to involve extra mechanisms providing the flat profile.

6. Discussion

Particles being suggested as possible candidates for the role of dark matter particles are considered as a bridge connecting modern achievements of quantum field theory with the cosmological pressing issues. In this vein, hypothetical elementary particles following from classical quantum chromodynamics (axions) and supersymmetric extensions of quantum field theories are proposed. They range from weakly interacting massive particles (WIMPs) up to ultralight axions. WIMPs are basically particles from the theory of supersymmetry (supersymmetric partners of ordinary particles of the Standard Model) with masses exceeding a few KeV. However, in parallel with the WIMPs, axions are also considered in theory. These hypothetical particles have an exceptionally low mass, hundreds to billions of times less than the lightest particles known to us today. They are so light that their wavelength can be equal to the diameter of the galaxy and more. However, there are no experimental confirmations of the registration of any particles from the mentioned row until now - despite numerous attempts, it has not been possible to detect WIMPs or axions so far. The first assumption is that dark matter can be an illusion [

42,

46], far from its application for the explanation of the universe phenomena.

Vera Rubin put forward serious arguments in favor of the existence of dark matter yet in 1993 [

47]. There exist skeptics, however, who question the existence of this substance, as, for example, Rajendra P. Gupta [

48,

49].

The modern observations of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) [

50] showed an unexpected morphology of galaxies that existed at the dawn of the universe. The galaxies, for example, were more massive and developed. There were more of them, and they were smaller. These observations require a thorough revision of the established picture of the organization of the universe. Based on these observations, the newest study of Gupta [

48,

49] casts doubt on the generally accepted models of the evolving universe. They include the phenomenon of "tired light" to partially explain the observed redshift, for example. He proves that, at least, there is no place for dark matter in them. Gupta’s theory requires strict evidence by applying different methods.

The author does not reject the existence of dark matter. Moreover, he believes that dark matter and dark energy have been present in physics for a long time implicitly. But they are removed by the Lorentz gauge from subsequent consideration of the physical observed phenomena. First, note that there is the ambiguity of the definition of potentials. With these electric and magnetic fields, the scalar,

, and vector potentials,

, are ambiguously defined. If

is an arbitrary function of coordinates and time, then the following transformations do not change the values of the fields:

The same transformation is done relative to the gravity-mechanical motion by adding an arbitrary function of coordinates and time

. Note, only, that the arbitrary functions

and

are introduced in Eqs. (

7) and () by slightly other way. There, we define the gravity-mechanical and electromagnetic energy-momentum densities to have the dimension

Energy·length, while the arbitrary scalar field

has the dimension

Energy·length. Note that the cosmological term has the dimension

length.

It hints that the arbitrary scalar field

can have relation to the cosmological physics by applying the physics of the quaternion algebra to the cosmological tasks.In this case, we proclaim that the equation

following from the Lorentz gauge (

11) describes the state of dark energy and dark matter. Here

,

, is the energy-momentum density within an elementary 4D space-time volume. More strictly, one can say that it is a pressure provided on walls of this elementary volume. Then

represents divergence of the baryon matter through these walls in 4D space-time.

Here

consists of the superposition of two arbitrary scalar fields

and

. The first field is massless; it spreads with the speed of light. The second field is mass-loaded. Therefore, it’s spreading in space at speeds smaller than the speed of light. We rewrite a contribution of the second field in Eq. (

37) by adding and subtracting the mass term

as shown in Eq. (

13). On the second step, we pick the Klein-Gordon equation, which returns a wave solution of a massive particle with zero spin, that is, a massive boson. Next, we partition this equation on to two coupled Dirac operators acting on the same mass shell (

14). These operators return Majorana fermions coupled to each other on the mass shell. It is the massive boson mentioned above.

The problem is to evaluate the Majorana fermion mass. In these evaluations, we base them on the CDM paradigm. Here the part being the cosmological constant in the Freedman equation opens a possibility to evaluate the critical density, which is proportional to the Hubble constant in square. Next, we calculate the dark matter critical density. The part CDM, reading as Could Dark Matter, states that dark matter finds itself at the CMB temperature, K.

Thus, there are three key parameters for evaluating the Majorana fermion mass. They are the dark matter critical density (

15), the Planck constant (), and the CMB temperature (). It turns out the formula for computing the Majorana fermion mass is a five-degree root from the combination of the above parameters (

18). The calculation of mass by this formula shows that the Majorana fermion mass is in good agreement with masses experimentally measured for neutrino,

eV. Thus, one can assert that the Majorana fermion considered in this article is neutrino.

Take attention that the dark matter critical density reads as the relation of the Majorana fermion mass to the volume occupied by this fermion (

15). It can mean that for any number of fermions,

N, all they will take a tight package

capable of producing the Bose–Einstein condensate at the CMB temperature. First, let us compute the volume (

21), we get

m

. Next, we evaluate how many fermions can be in 1 cm

. We get about

. Finally, we evaluate what mass is of this amount of the Majorana fermion. It is about

. From here it follows that the ordered compact ensembles of the Majorana fermions enclosed in volumes about 0.615 cm

, or

,

return weight equal to 1 keV, 1 MeV, 1 GeV, respectively. Obviously, in these cases, it is better to say about wave fermion modes supported in these volumes.

The idea about generations of fermions underlying the different wave modes comes from the possibility of existing the set of

n roots stemming from n

th-degree root that can be written, in the general, as follows:

Here the integer k runs numbers . We group the roots by complex conjugated pairs if the number n is odd. At , we have the real term . For even n, the grouping of roots by complex-conjugated pairs is as follows: . At and there are two real terms and , respectively.

Summing up complex conjugated terms by pairs results in a set of doubled cosines:

for

l ranging

for odd

n. The sum of all terms in (

40) for

l ranging from 1 to

is negative and equal to

. As for

it is a special case, which gives

. The sum together with the term at

vanishes. These numbers form a closed loop, either clockwise or counterclockwise, depending on the orientation of the chirality,

Figure 9.

It reproduces generations of wave modes by a number equal to

. In particular, at

there are only three generations shown in

Figure 6.

The sum of all closed loops forms wave modes of superfluid dark matter at the CMB temperature, since the elementary volumes containing fermion modes being tightly packed occupy the whole near galactic space. It is believed that most galaxies are surrounded by halos filled by dark matter. If so, that the baryon matter rotates about a galaxy center within the superfluid dark medium without encountering resistance from it. It means that the remote galaxy arms will rotate with the same orbital speed, as well as close ones. That is, the orbital speed demonstrates the flat profile at the large distance from the galaxy core.