Submitted:

09 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

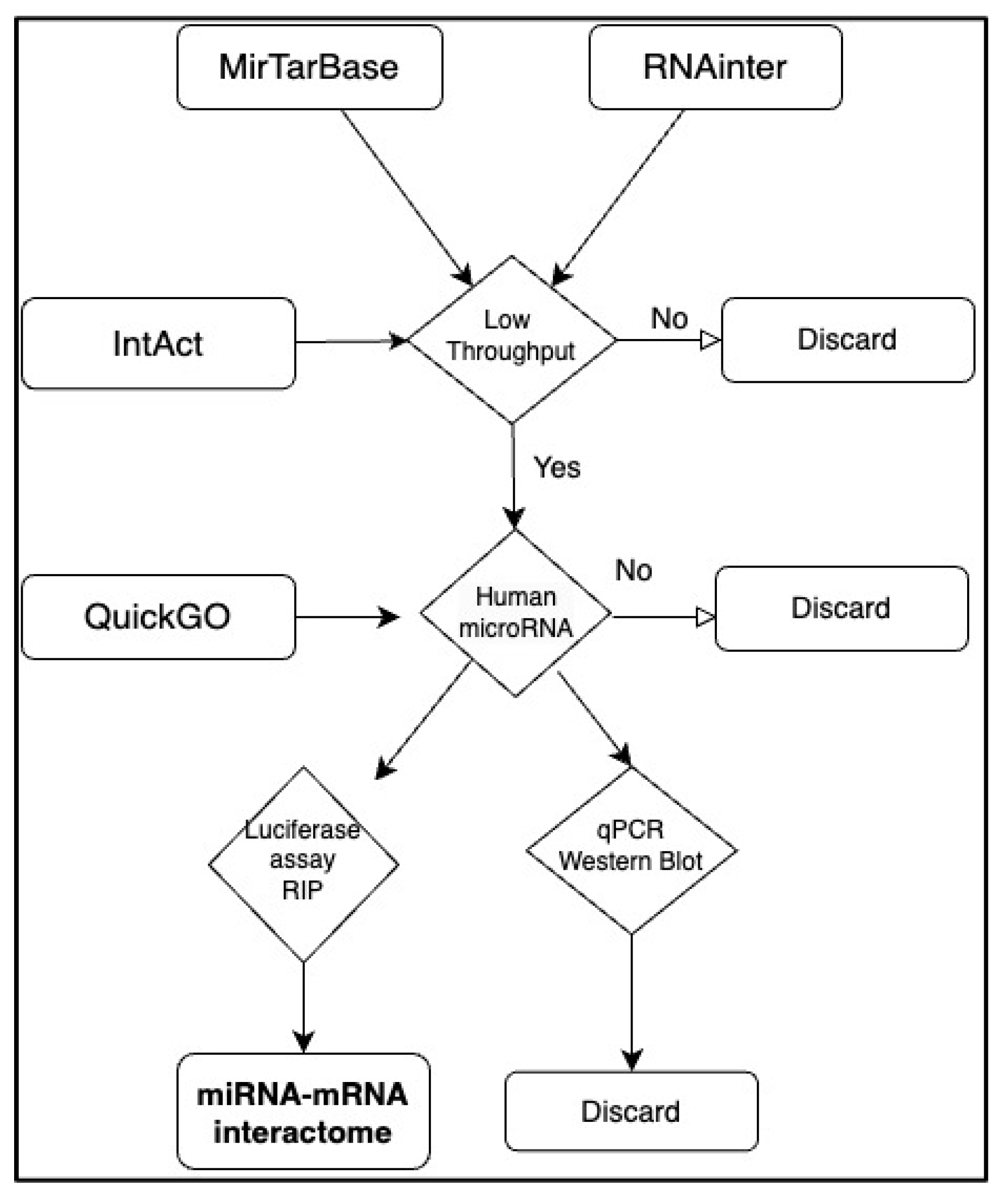

2.1. Dataset Integration

2.2. Network Analysis

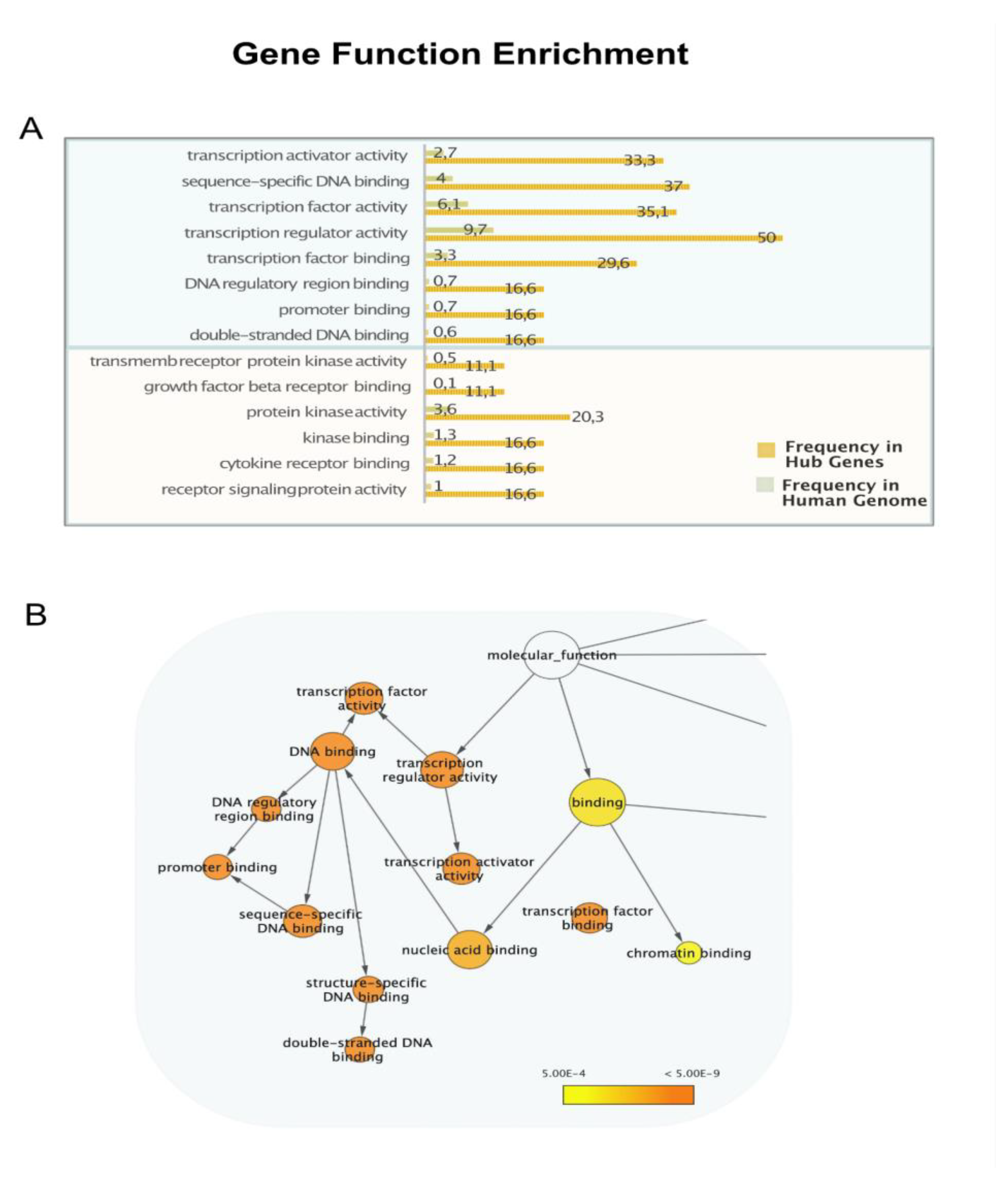

2.3. Gene Ontology and Pathway Enrichment Analysis

2.4. Other Statistical Analysis

3. Results

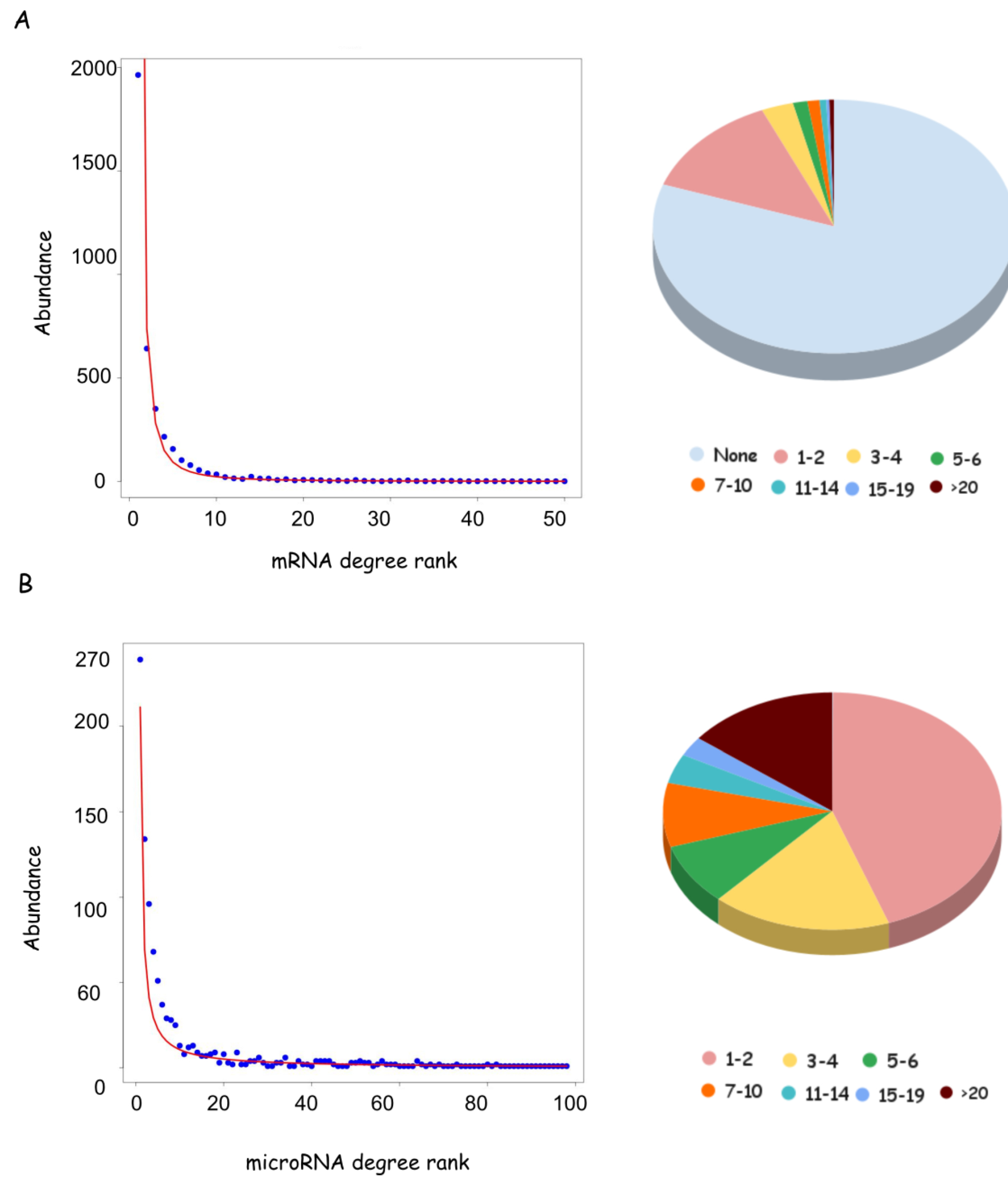

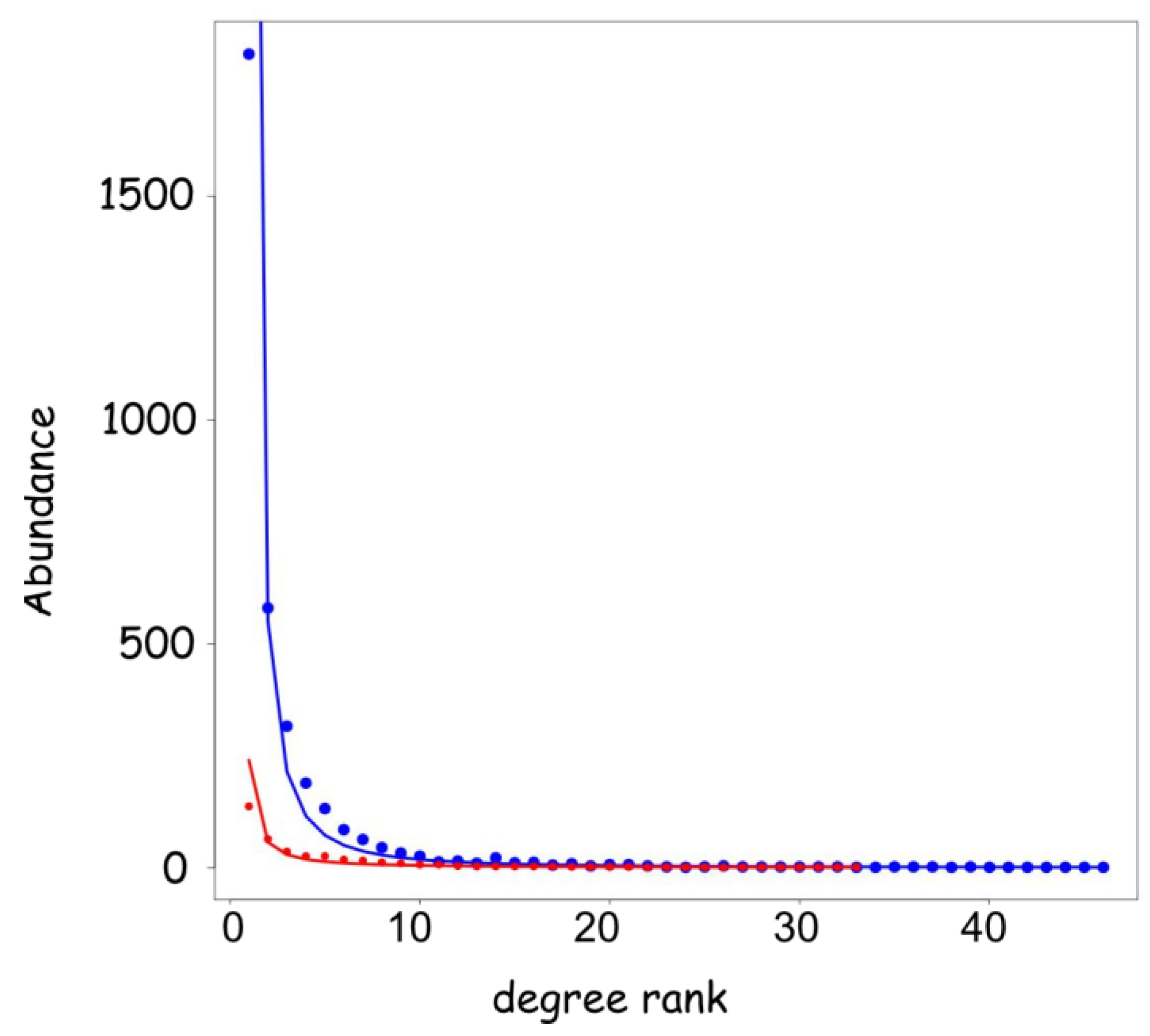

3.1. General Characteristics of the microRNA-mRNA S

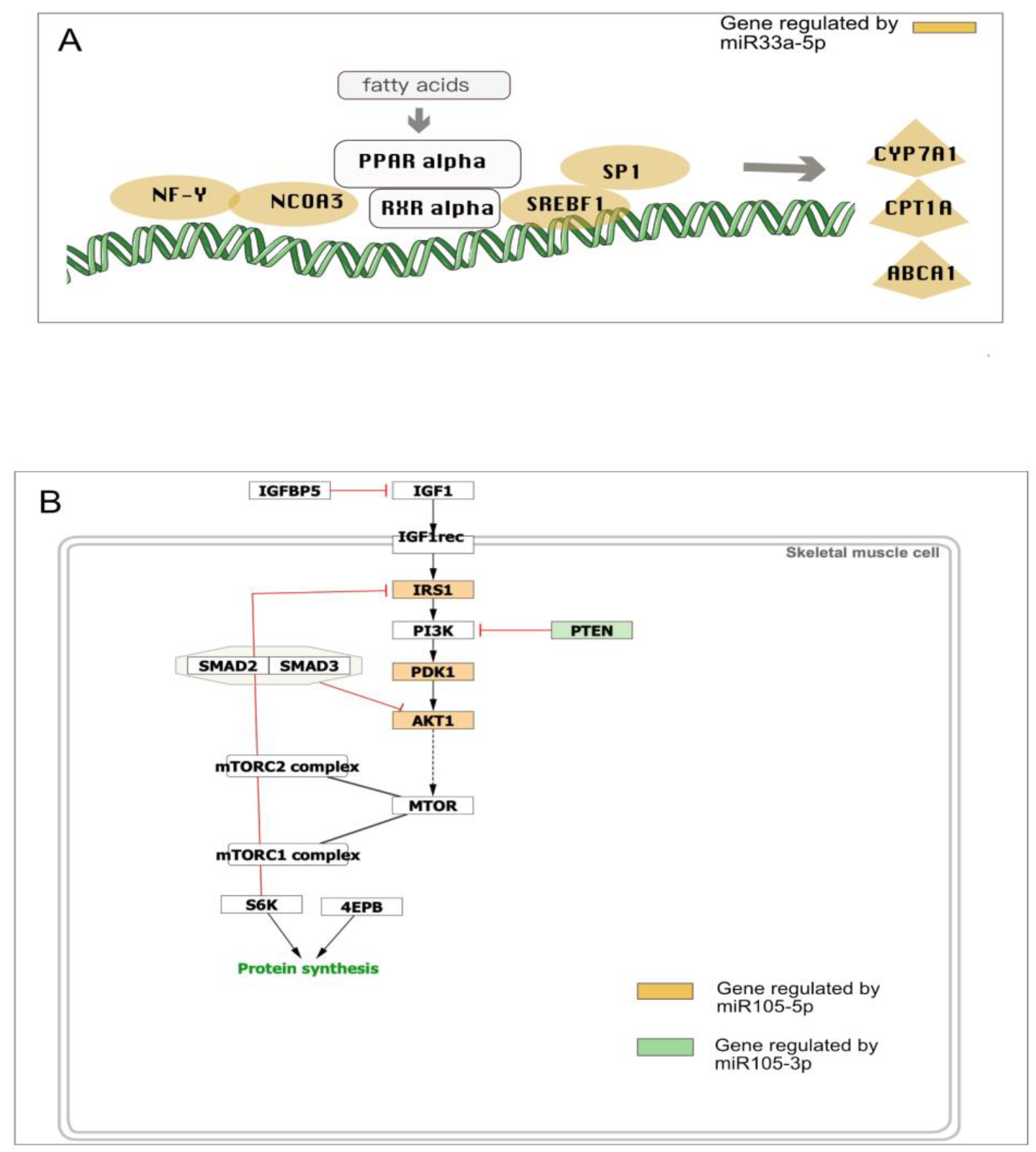

3.2. mRNA Highly Regulated Are Regulators

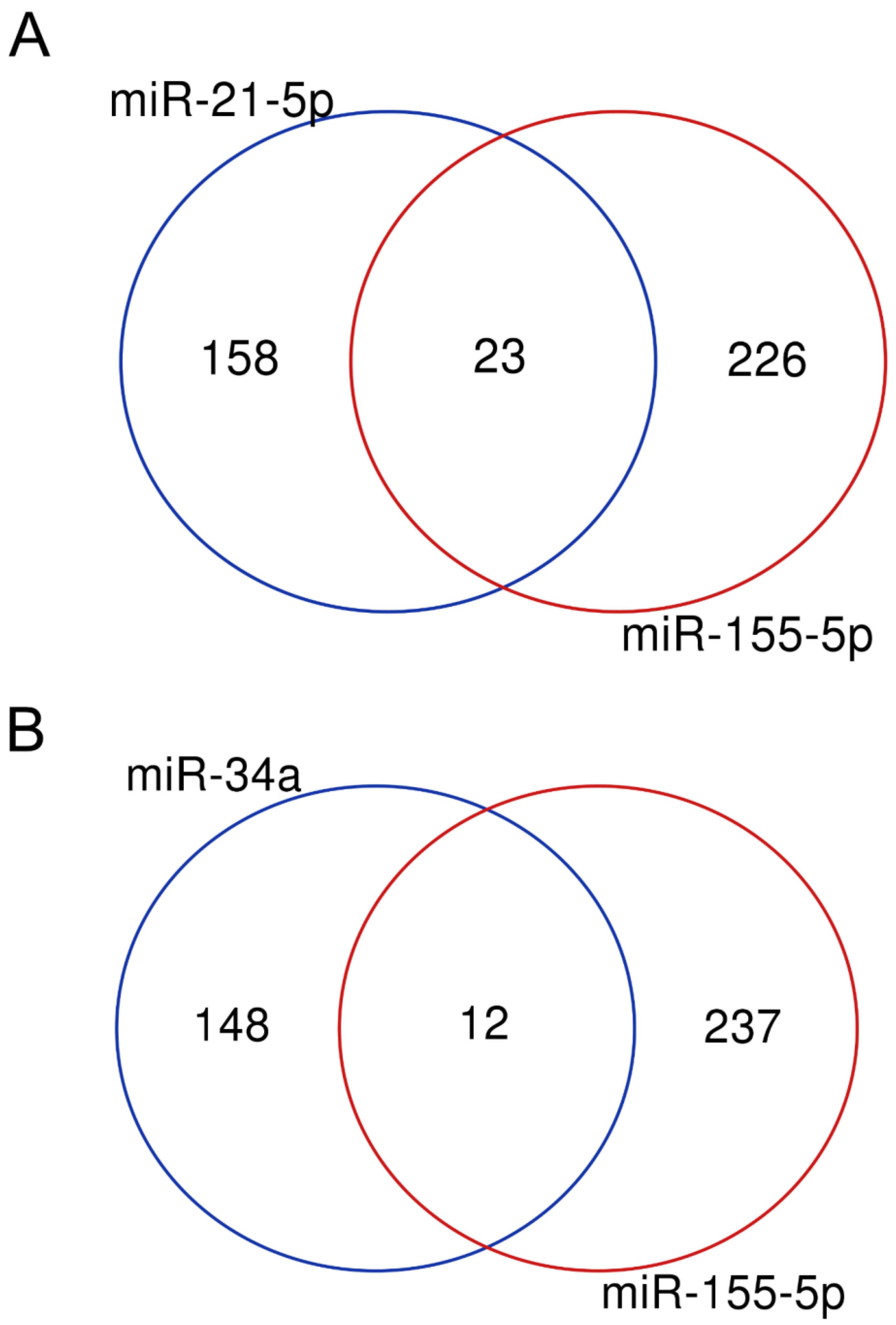

3.3. microRNAs Regulate Multiple Targets

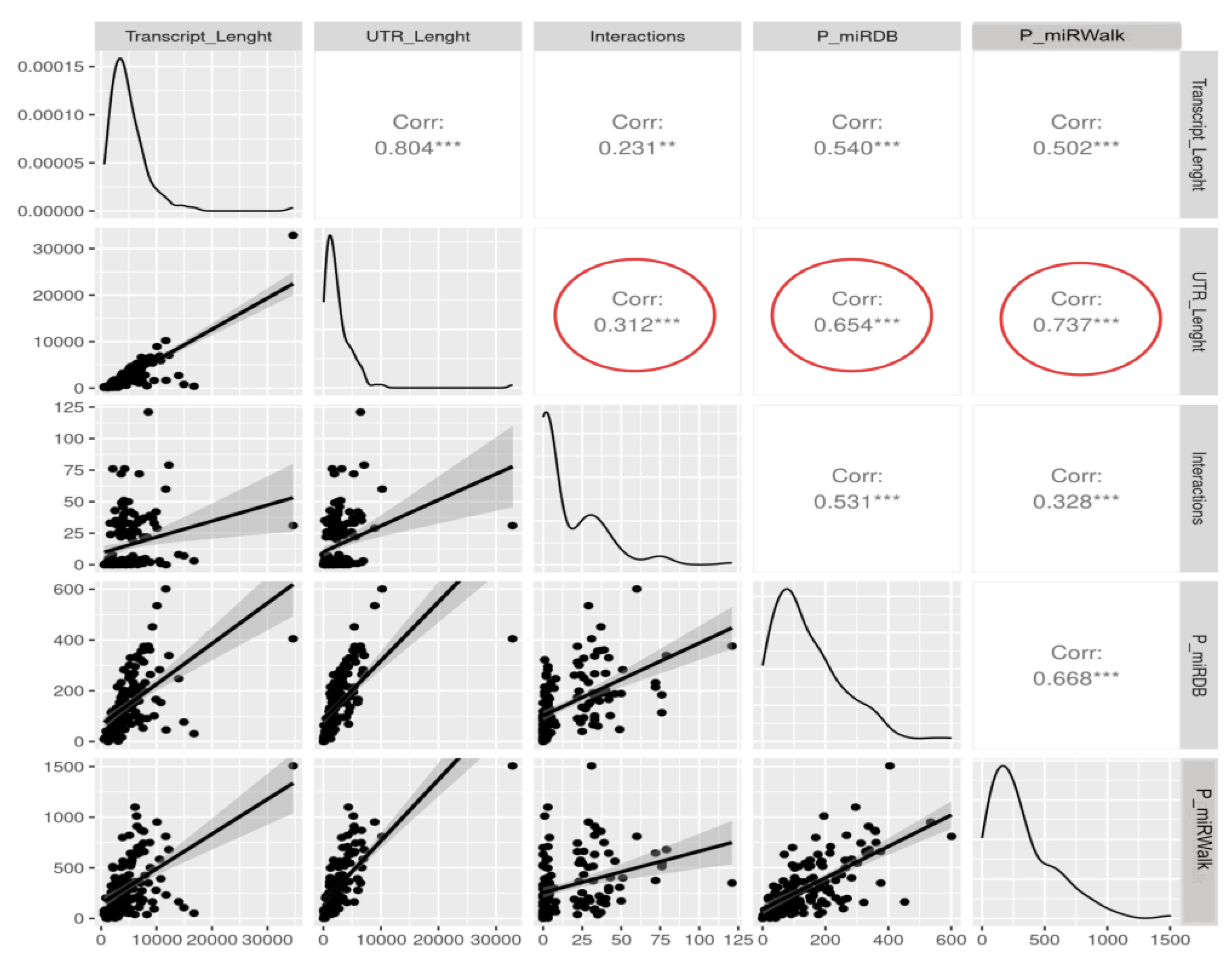

3.4. The Length of the Untranslated Regions Do Not Correlate with the Abundance of Interactors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993 Dec 3;75(5):843-54. PMID: 8252621. [CrossRef]

- Fire, A., Xu, S., Montgomery, M. et al. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 391, 806–811 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Duchaine TF, Fabian MR. Mechanistic Insights into MicroRNA-Mediated Gene Silencing. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2019 Mar 1;11(3):a032771. PMID: 29959194; PMCID: PMC6396329. [CrossRef]

- Diener C, Keller A, Meese E. The miRNA-target interactions: An underestimated intricacy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024 Feb 28;52(4):1544-1557. PMID: 38033323; PMCID: PMC10899768. [CrossRef]

- Schäfer M, Ciaudo C. Prediction of the miRNA interactome - Established methods and upcoming perspectives. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020 Mar 5;18:548-557. PMID: 32211130; PMCID: PMC7082591. [CrossRef]

- Quillet A, Anouar Y, Lecroq T, Dubessy C. Prediction methods for microRNA targets in bilaterian animals: Toward a better understanding by biologists. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021 Oct 18;19:5811-5825. PMID: 34765096; PMCID: PMC8567327. [CrossRef]

- Bartel DP. Metazoan MicroRNAs. Cell. 2018 Mar 22;173(1):20-51. PMID: 29570994; PMCID: PMC6091663. [CrossRef]

- Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010 Aug 12;466(7308):835-40. PMID: 20703300; PMCID: PMC2990499. [CrossRef]

- Lewis,B.P., Shih I -,H., Jones-Rhoades,M.W. et al. (2003) Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell, 115,787–798.

- Kakumani PK. AGO-RBP crosstalk on target mRNAs: Implications in miRNA-guided gene silencing and cancer. Transl Oncol. 2022 Jul;21:101434. Epub 2022 Apr 26. PMID: 35477066; PMCID: PMC9136600. [CrossRef]

- RNAcentral Consortium. RNAcentral 2021: secondary structure integration, improved sequence search and new member databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021 Jan 8;49(D1):D212-D220. PMID: 33106848; PMCID: PMC7779037. [CrossRef]

- Panni S, Prakash A, Bateman A, Orchard S. The yeast noncoding RNA interaction network. RNA. 2017 Oct;23(10):1479-1492. Epub 2017 Jul 12. PMID: 28701522; PMCID: PMC5602107. [CrossRef]

- Simona Panni, Kalpana Panneerselvam, Pablo Porras, Margaret Duesbury, Livia Perfetto, Luana Licata, Henning Hermjakob, Sandra Orchard, The landscape of microRNA interaction annotation: analysis of three rare disorders as a case study, Database, Volume 2023, 2023, baad066. [CrossRef]

- Huntley RP, Kramarz B, Sawford T, Umrao Z, Kalea A, Acquaah V, Martin MJ, Mayr M, Lovering RC. Expanding the horizons of microRNA bioinformatics. RNA. 2018 Aug;24(8):1005-1017. Epub 2018 Jun 5. PMID: 29871895; PMCID: PMC6049505. [CrossRef]

- Chi SW, Zang JB, Mele A, Darnell RB. Argonaute HITS-CLIP decodes microRNA-mRNA interaction maps. Nature. 2009 Jul 23;460(7254):479-86. Epub 2009 Jun 17. PMID: 19536157; PMCID: PMC2733940. [CrossRef]

- Helwak A, Kudla G, Dudnakova T, Tollervey D. Mapping the human miRNA interactome by CLASH reveals frequent noncanonical binding. Cell. 2013 Apr 25;153(3):654-65. PMID: 23622248; PMCID: PMC3650559. [CrossRef]

- Del Toro N, Shrivastava A, Ragueneau E, Meldal B, Combe C, Barrera E, Perfetto L, How K, Ratan P, Shirodkar G, Lu O, Mészáros B, Watkins X, Pundir S, Licata L, Iannuccelli M, Pellegrini M, Martin MJ, Panni S, Duesbury M, Vallet SD, Rappsilber J, Ricard-Blum S, Cesareni G, Salwinski L, Orchard S, Porras P, Panneerselvam K, Hermjakob H. The IntAct database: efficient access to fine-grained molecular interaction data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022 Jan.

- Huang HD. miRTarBase update 2022: an informative resource for experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022 Jan 7;50(D1):D222-D230. PMID: 34850920; PMCID: PMC8728135. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Lin J, Cui T, Hu Y, Tan P, Cheng J, Zheng H, Wang D, Su X, Chen W, Huang Y. RNAInter v4.0: RNA interactome repository with redefined confidence scoring system and improved accessibility. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022 Jan 7;50(D1):D326-D332. PMID: 34718726; PMCID: PMC8728132. [CrossRef]

- Binns, D., Dimmer, E., Huntley, D. B., O’Donovan, C., and Apweiler, R. (2009).

- QuickGO: a web-based tool for gene ontology searching. Bioinformatics 25 (22),.

- 3045–3046. [CrossRef]

- Porras P, Barrera E, Bridge A, Del-Toro N, Cesareni G, Duesbury M, Hermjakob H, Iannuccelli M, Jurisica I, Kotlyar M, Licata L, Lovering RC, Lynn DJ, Meldal B, Nanduri B, Paneerselvam K, Panni S, Pastrello C, Pellegrini M, Perfetto L, Rahimzadeh N, Ratan P, Ricard-Blum S, Salwinski L, Shirodkar G, Shrivastava A, Orchard S. Towards a unified open access dataset of molecular interactions. Nat Commun. 2020 Dec 1;11(1):6144. PMID: 33262342; PMCID: PMC7708836. [CrossRef]

- UniProt Consortium. UniProt: the Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023 Jan 6;51(D1):D523-D531. PMID: 36408920; PMCID: PMC9825514. [CrossRef]

- Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003 Nov;13(11):2498-504. PMID: 14597658; PMCID: PMC403769. [CrossRef]

- Lovering RC, Gaudet P, Acencio ML, Ignatchenko A, Jolma A, Fornes O, Kuiper M, Kulakovskiy IV, Lægreid A, Martin MJ, Logie C. A GO catalogue of human DNA-binding transcription factors. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech. 2021 Nov-Dec;1864(11-12):194765. Epub 2021 Oct 18. PMID: 34673265. [CrossRef]

- Liska O, Bohár B, Hidas A, Korcsmáros T, Papp B, Fazekas D, Ari E (2022) TFLink: An integrated gateway to access transcription factor - target gene interactions for multiple species. Database, baac083.

- Paulo I Prado, Murilo Dantas Miranda and Andre Chalom (2024) sads: Maximum Likelihood Models for Species Abundance Distributions. R package version 0.6.3 (https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sads).

- Hausser J and Strimmer K (2009) Entropy Inference and the James-Stein Estimator, with Application to Nonlinear Gene Association Networks. Journal of Machine Learning Research 10 (2009) 1469-1484.

- Zheng, L. 2019. Using mutual information as a cocitation similarity measure . Scientometrics, 119: 1695-1713.

- Jeuken, G. S. & Käll, L. 2024. Pathway analysis through mutual information Bioinformatics, 40: btad776.

- Neeson, T. M. & Mandelik, Y. 2014. Pairwise measures of species co-occurrence for choosing indicator species and quantifying overlap . Ecological Indicators, 45: 721-727.

- Kolberg L, Raudvere U, Kuzmin I, Adler P, Vilo J, Peterson H. g:Profiler-interoperable web service for functional enrichment analysis and gene identifier mapping (2023 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 2023 Jul 5;51(W1):W207-W212. PMID: 37144459; PMCID: PMC10320099. [CrossRef]

- Richardson JE, Bult CJ. Visual annotation display (VLAD): a tool for finding functional themes in lists of genes. Mamm Genome. 2015 Oct;26(9-10):567-73. Epub 2015 Jun 6. PMID: 26047590; PMCID: PMC4602057. [CrossRef]

- Maere,S., Heymans,K. and Kuiper,M. (2005) BiNGO: a Cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of gene ontol-ogy categories in biological networks. Bioinformatics, 21,3448–3449.

- Griss J, Viteri G, Sidiropoulos K, Nguyen V, Fabregat A, Hermjakob H. ReactomeGSA - Efficient Multi-Omics Comparative Pathway Analysis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2020 Sep 9. PubMed PMID: 32907876. Da studiare ma meglio quello sopra come referenza. [CrossRef]

- Yuhao Chen and Xiaowei Wang (2020) miRDB: an online database for prediction of functional microRNA targets. Nucleic Acids Research. 48(D1):D127-D131.

- Sticht C, De La Torre C, Parveen A, Gretz N. miRWalk: An online resource for prediction of microRNA binding sites. PLoS One. 2018 Oct 18;13(10):e0206239. PMID: 30335862; PMCID: PMC6193719. [CrossRef]

- Schloerke B, Cook D, Larmarange J, Briatte F, Marbach M, Thoen E, Elberg A, Crowley J (2021). _GGally: Extension to 'ggplot2'_. R package version 2.1.2, <https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=GGally>.

- R Core Team (2023). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.

- Ahmed SH, Deng AT, Huntley RP, Campbell NH, Lovering RC. Capturing heart valve development with Gene Ontology. Front Genet. 2023 Oct 17;14:1251902. PMID: 37915827; PMCID: PMC10616796. [CrossRef]

- Shalgi R, Lieber D, Oren M, Pilpel Y. Global and local architecture of the mammalian microRNA-transcription factor regulatory network. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007 Jul;3(7):e131. PMID: 17630826; PMCID: PMC1914371. [CrossRef]

- Vikram Agarwal, George W Bell, Jin-Wu Nam, David P Bartel (2015) Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs eLife 4:e05005.

- Ghafouri-Fard S, Abak A, Shoorei H, Mohaqiq M, Majidpoor J, Sayad A, Taheri M. Regulatory role of microRNAs on PTEN signaling. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021 Jan;133:110986. Epub 2020 Nov 7. PMID: 33166764. [CrossRef]

- Kim T, Croce CM. MicroRNA: trends in clinical trials of cancer diagnosis and therapy strategies. Exp Mol Med. 2023 Jul;55(7):1314-1321. Epub 2023 Jul 10. PMID: 37430087; PMCID: PMC10394030. [CrossRef]

- Inoue J, Inazawa J. Cancer-associated miRNAs and their therapeutic potential. J Hum Genet. 2021 Sep;66(9):937-945. Epub 2021 Jun 4. PMID: 34088973.). [CrossRef]

- Rupaimoole R, Slack FJ. MicroRNA therapeutics: towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017 Mar;16(3):203-222. Epub 2017 Feb 17. PMID: 28209991. [CrossRef]

- He L, Thomson JM, Hemann MT, Hernando-Monge E, Mu D, Goodson S, Powers S, Cordon-Cardo C, Lowe SW, Hannon GJ, Hammond SM. A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature. 2005 Jun 9;435(7043):828-33. PMID: 15944707; PMCID: PMC4599349. [CrossRef]

- Gambari R, Brognara E, Spandidos DA, Fabbri E. Targeting oncomiRNAs and mimicking tumor suppressor miRNAs: Νew trends in the development of miRNA therapeutic strategies in oncology (Review). Int J Oncol. 2016 Jul;49(1):5-32. Epub 2016 May 4. PMID: 27175518; PMCID: PMC4902075. [CrossRef]

- Kehl T, Kern F, Backes C, Fehlmann T, Stöckel D, Meese E, Lenhof HP, Keller A. miRPathDB 2.0: a novel release of the miRNA Pathway Dictionary Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020 Jan 8;48(D1):D142-D147. PMID: 31691816; PMCID: PMC7145528. [CrossRef]

- Kern F, Krammes L, Danz K, Diener C, Kehl T, Küchler O, Fehlmann T, Kahraman M, Rheinheimer S, Aparicio-Puerta E, Wagner S, Ludwig N, Backes C, Lenhof HP, von Briesen H, Hart M, Keller A, Meese E. Validation of human microRNA target pathways enables evaluation of target prediction tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021 Jan 11;49(1):127-144. PMID: 33305319; PMCID: PMC7797041. [CrossRef]

- Doran G. The short and the long of UTRs. J RNAi Gene Silencing. 2008 May 27;4(1):264-5. PMID: 19771235; PMCID: PMC2737238.

- Mazumder B, Seshadri V, Fox PL. Translational control by the 3'-UTR: the ends specify the means. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003 Feb;28(2):91-8. PMID: 12575997. [CrossRef]

- Nam JW, Rissland OS, Koppstein D, Abreu-Goodger C, Jan CH, Agarwal V, Yildirim MA, Rodriguez A, Bartel DP. Global analyses of the effect of different cellular contexts on microRNA targeting. Mol Cell. 2014 Mar 20;53(6):1031-1043. Epub 2014 Mar 13. PMID: 24631284; PMCID: PMC4062300. [CrossRef]

- Varendi K, Kumar A, Härma MA, Andressoo JO. miR-1, miR-10b, miR-155, and miR-191 are novel regulators of BDNF. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014 Nov;71(22):4443-56. Epub 2014 May 8. PMID: 24804980; PMCID: PMC4207943. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Wang X. miRDB: an online database for prediction of functional microRNA targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020 Jan 8;48(D1):D127-D131. PMID: 31504780; PMCID: PMC6943051. [CrossRef]

- Sticht C, De La Torre C, Parveen A, Gretz N. miRWalk: An online resource for prediction of microRNA binding sites. PLoS One. 2018 Oct 18;13(10):e0206239. PMID: 30335862; PMCID: PMC6193719. [CrossRef]

- Selbach M, Schwanhäusser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, Rajewsky N. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature. 2008 Sep 4;455(7209):58-63. Epub 2008 Jul 30. PMID: 18668040. [CrossRef]

- Panni S., Corbelli A., Sztuba-Solinska J. (2023) Regulation of non-coding.

- NAs (Book Chapter) Ch06 in “Navigating Non-coding RNA: From Biogenesis to Therapeutic Application” (Elsevier) p209-271.

- O’Donnell, K. A., Wentzel, E. A., Zeller, K. I., Dang, C. v., & Mendell, J. T. (2005). c-Myc-regulated microRNAs modulate E2F1 expression. Nature, 435(7043). [CrossRef]

- Martinez, N. J., & Walhout, A. J. M. (2009). The interplay between transcription factors and microRNAs in genome-scale regulatory networks. BioEssays, 31(4). [CrossRef]

- Alam T, Agrawal S, Severin J, Young RS, Andersson R, Arner E, Hasegawa A, Lizio M, Ramilowski JA, Abugessaisa I, Ishizu Y, Noma S, Tarui H, Taylor MS, Lassmann T, Itoh M, Kasukawa T, Kawaji H, Marchionni L, Sheng G, R R Forrest A, Khachigian LM, Hayashizaki Y, Carninci P, de Hoon MJL. Comparative transcriptomics of primary cells in vertebrates. Genome Res. 2020 Jul;30(7):951-961. Epub 2020 Jul 27. PMID: 32718981; PMCID: PMC7397866. [CrossRef]

- Migault M, Sapkota S, Bracken CP. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional control of epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity: why so many regulators? Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022 Mar 12;79(3):182. PMID: 35278142; PMCID: PMC8918127. [CrossRef]

- Ito T, Chiba T, Ozawa R, Yoshida M, Hattori M, Sakaki Y. A comprehensive two-hybrid analysis to explore the yeast protein interactome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 Apr 10;98(8):4569-74. Epub 2001 Mar 13. PMID: 11283351; PMCID: PMC31875. [CrossRef]

- Huntley RP, Sitnikov D, Orlic-Milacic M, Balakrishnan R, D'Eustachio P, Gillespie ME, Howe D, Kalea AZ, Maegdefessel L, Osumi-Sutherland D, Petri V, Smith JR, Van Auken K, Wood V, Zampetaki A, Mayr M, Lovering RC. Guidelines for the functional annotation of microRNAs using the Gene Ontology. RNA. 2016 May;22(5):667-76. Epub 2016 Feb 25. PMID: 26917558; PMCID: PMC4836642. [CrossRef]

- Villaveces JM, Jiménez RC, Porras P, Del-Toro N, Duesbury M, Dumousseau M, Orchard S, Choi H, Ping P, Zong NC, Askenazi M, Habermann BH, Hermjakob H. Merging and scoring molecular interactions utilising existing community standards: tools, use-cases and a case study. Database (Oxford). 2015 Feb 4;2015:bau131. PMID: 25652942; PMCID: PMC4316181. [CrossRef]

- Antonazzo G, Gaudet P, Lovering RC, Attrill H. Representation of non-coding RNA-mediated regulation of gene expression using the Gene Ontology. RNA Biol. 2024 Jan;21(1):36-48. Epub 2024 Oct 7. PMID: 39374113; PMCID: PMC11459742. [CrossRef]

- Kuiper M, Bonello J, Fernández-Breis JT, Bucher P, Futschik ME, Gaudet P, Kulakovskiy IV, Licata L, Logie C, Lovering RC, Makeev VJ, Orchard S, Panni S, Perfetto L, Sant D, Schulz S, Vercruysse S, Zerbino DR, Lægreid A; GRECO Consortium. The gene regulation knowledge commons: the action area of GREEKC. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech. 2022 Jan;1865(1):194768. Epub 2021 Oct 30. PMID: 34757206. [CrossRef]

| microRNA name | Number of Interactors | Oncogene | Tumour Suppressor | Reference |

| hsa-miR-155-5p | 262 | YES | 43 | |

| hsa-miR-21-5p | 182 | YES | 43, 44 | |

| hsa-miR-145-5p | 171 | YES | 45 | |

| hsa-miR-34a-5p | 156 | YES | 43 | |

| hsa-miR-125b-5p | 141 | YES | 47 | |

| hsa-miR-124-3p | 138 | YES | 47 | |

| hsa-miR-29b-3p | 135 | YES | 47 | |

| hsa-miR-200c-3p | 134 | YES | 45 | |

| hsa-miR-17-5p | 131 | YES | 46 | |

| hsa-miR-29a-3p | 127 | YES | 47 | |

| hsa-miR-1-3p | 110 | YES | 47 | |

| hsa-miR-20a-5p | 107 | YES | 43, 46 | |

| hsa-miR-9-5p | 103 | YES | 38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).