Submitted:

10 December 2024

Posted:

11 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. In Vitro Antiviral Effects of AEMH on SARS-CoV-2

2.2. Components Identified from AEMH

2.3. Screening of Targets Related to Covid-19 and AEMH

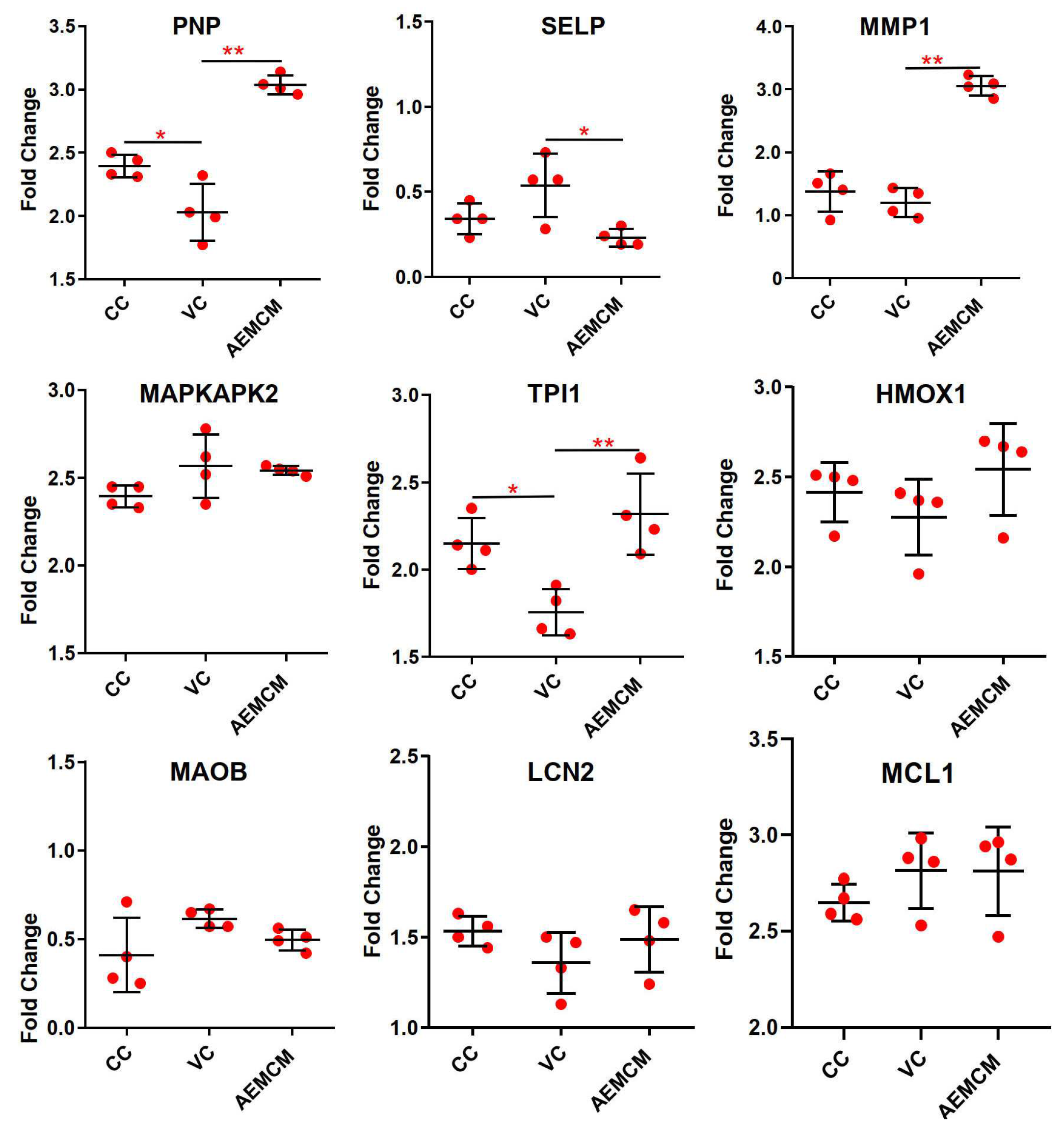

2.4. Screening and Verification of Core Targets

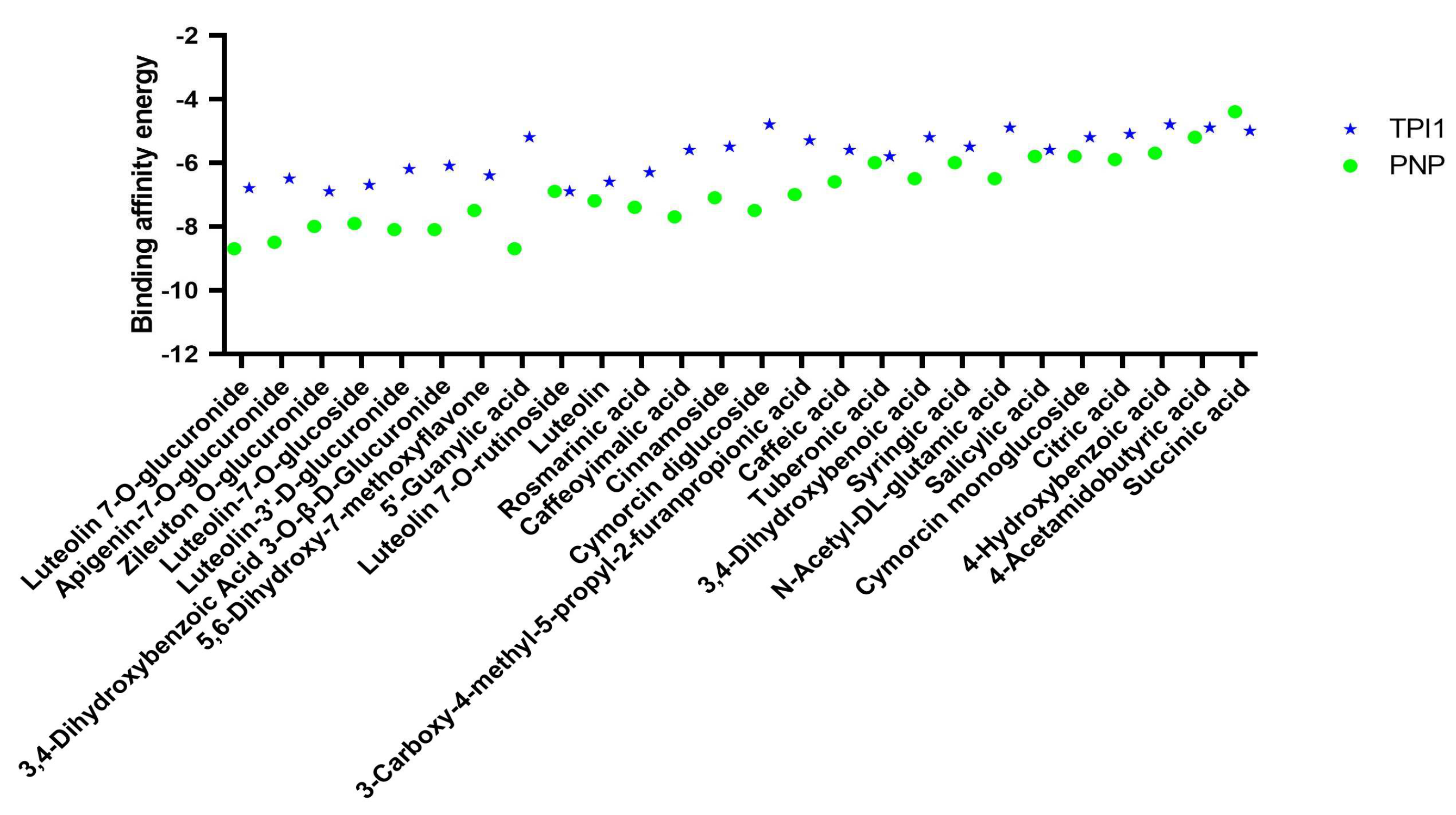

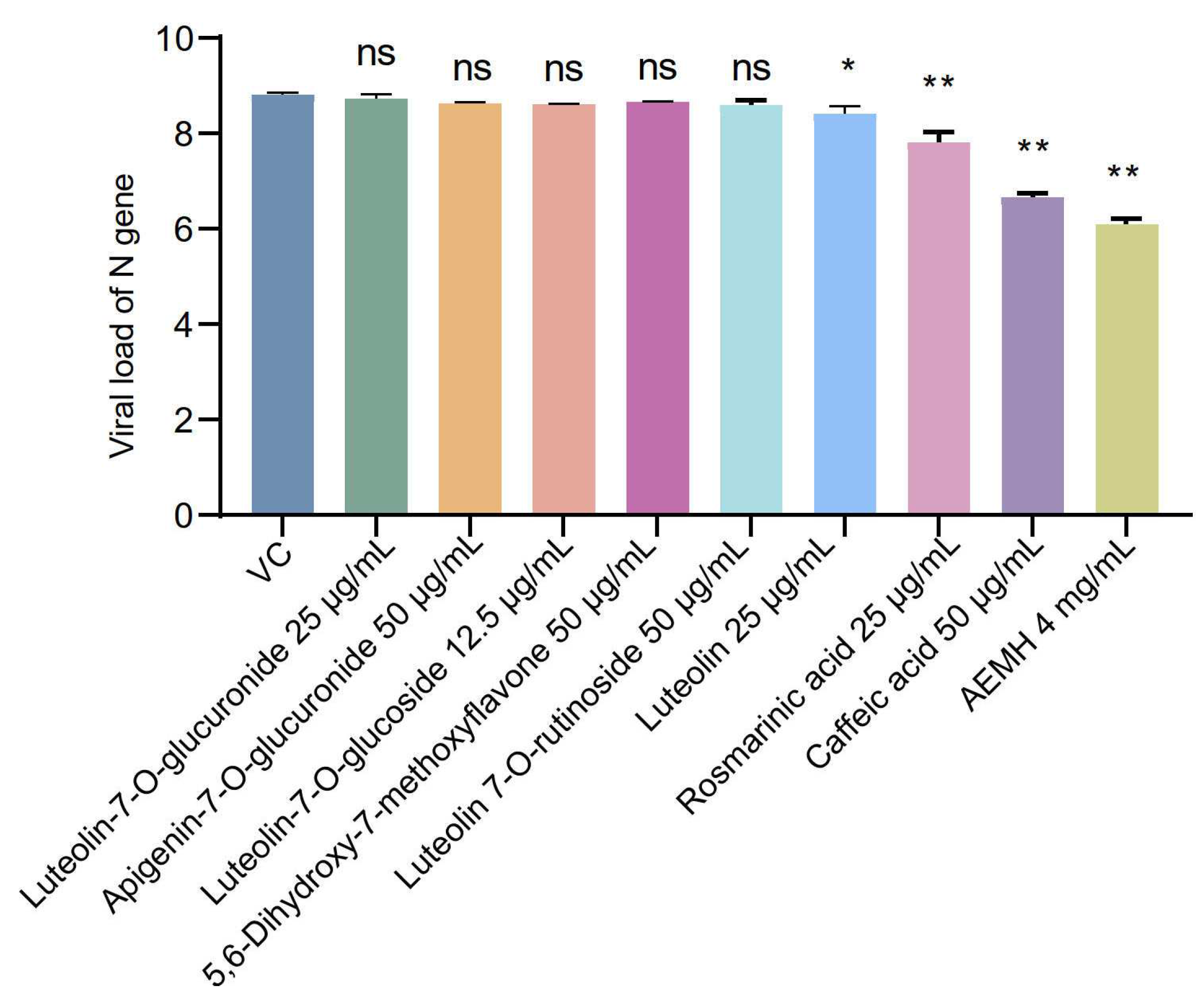

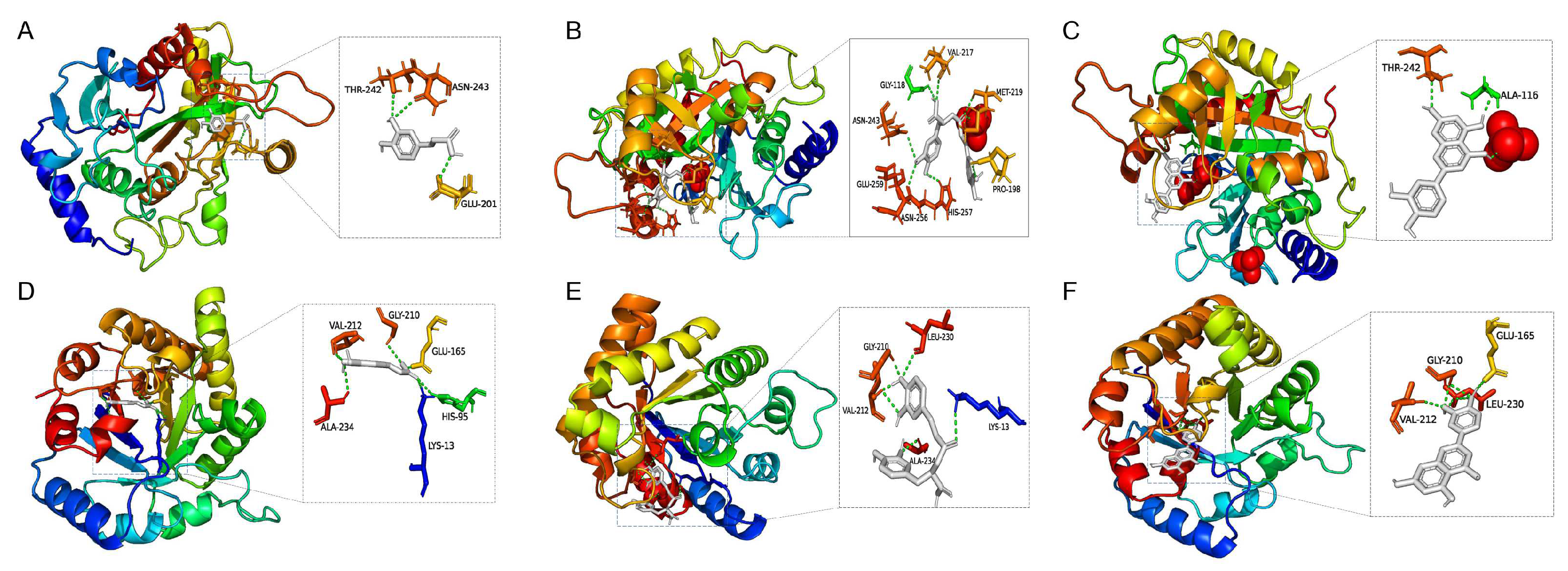

2.5. Screening and Identification of Active Components

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Medicines

4.4. Cytotoxicity of Medicines

4.5. In vitro Antiviral Verification Experiment

4.6. HPLC-ESI-Q-TOF/MS Conditions

4.7. Network Pharmacology

4.7.1. Screening of the SARS-CoV-2 Related Targets and the AEMH Related Targets

4.7.2. Screening of Core Targets

4.7. RNA Extraction and Quantitative real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

4.8. Molecular Docking

4.9. Statistic Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Word Health Organization (WH). WHO COVID-19 dashboard. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c (accessed on November 17, 2024).

- Chan, J.F.-W.; Yuan, S.; Chu, H.; Sridhar, S.; Yuen, K.-Y. COVID-19 drug discovery and treatment options. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 391–407. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.; Choi, A.Y.; Kopp, J.B.; Winkler, C.A.; Cho, S.K. Review of COVID-19 Therapeutics by Mechanism: From Discovery to Approval. J. Korean Med Sci. 2024, 39, e134. [CrossRef]

- Owen, D.R.; Allerton, C.M.N.; Anderson, A.S.; Aschenbrenner, L.; Avery, M.; Berritt, S.; Boras, B.; Cardin, R.D.; Carlo, A.; Coffman, K.J.; et al. An oral SARS-CoV-2 M pro inhibitor clinical candidate for the treatment of COVID-19. Science 2021, 374, 1586–1593. [CrossRef]

- Iketani, S.; Iketani, S.; Liu, L.; Liu, L.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, L.; Chan, J.F.-W.; Chan, J.F.-W.; et al. Antibody evasion properties of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron sublineages. Nature 2022, 604, 553–556. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Jian, F.; Xiao, T.; Song, W.; Yisimayi, A.; Huang, W.; Li, Q.; Wang, P.; An, R.; et al. Omicron escapes the majority of existing SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. Nature 2021, 602, 657–663. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Xu, D.; Tang, Y.; Luo, P. Traditional Chinese Medicine for the treatment of influenza: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2014, 34, 527–531. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.-P.; Jia, Z.-H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Liang, L.-C.; Zhang, C.-Q.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, S.-Q.; et al. Natural herbal medicine Lianhuaqingwen capsule anti-influenza A (H1N1) trial: a randomized, double blind, positive controlled clinical trial.. 2011, 124, 2925–33.

- Hung, S.-W.; Liao, Y.-C.; Chi, I.-C.; Lin, T.-Y.; Lin, Y.-C.; Lin, H.-J.; Huang, S.-T. Integrated Chinese herbal medicine and Western medicine successfully resolves spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum in a patient with severe COVID-19 in Taiwan: A case report. EXPLORE 2021, 19, 147–152. [CrossRef]

- Fan, A.Y.; Gu, S.; Alemi, S.F. Chinese herbal medicine for COVID-19: Current evidence with systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Integr. Med. 2020, 18, 385–394. [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, H.; Li, B.; Yu, X.; Wang, M.; Li, S.; Li, J. The efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of the COVID-19 pandemic in Henan Province: a retrospective study. Eur. J. Med Res. 2023, 28, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Brevini, T.; Maes, M.; Webb, G.J.; John, B.V.; Fuchs, C.D.; Buescher, G.; Wang, L.; Griffiths, C.; Brown, M.L.; Scott, W.E.; et al. FXR inhibition may protect from SARS-CoV-2 infection by reducing ACE2. Nature 2022, 615, 134–142. [CrossRef]

- He, M.-F.; Liang, J.-H.; Shen, Y.-N.; Zhang, J.-W.; Liu, Y.; Yang, K.-Y.; Liu, L.-C.; Wang, J.; Xie, Q.; Hu, C.; et al. Glycyrrhizin Inhibits SARS-CoV-2 Entry into Cells by Targeting ACE2. Life 2022, 12, 1706. [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Zeng, Z. Network-based pharmacology and UHPLC-Q-Exactive-Orbitrap-MS reveal Jinhua Qinggan granule's mechanism in reducing cellular inflammation in COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1382524. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Sun, Y.X. Treating 200 cases of cold of the Shushi type with Xinjia Xiangru Yin. Clin J Chin Med 2018, 26, 122-123. [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.C.; Ying, Y.F.; Zheng, H.W.; Hu, G.H.; Lin, Y.P. Study of Chaihu-Xiangru decoction on acute upper respiratory infection in summer. Mod J of Integr Tradit Chin West Med 2005, 4, 441-442.

- Wu, Q.-F.; Zhu, W.-R.; Yan, Y.-L.; Zhang, X.-X.; Jiang, Y.-Q.; Zhang, F.-L. Anti-H1N1 influenza effects and its possible mechanism of Huanglian Xiangru Decoction. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 185, 282–288. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.-Y.; Sun, Y.-P.; Wang, Z.-B.; Kuang, H.-X. Moslae Herba: Botany, Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacology. Molecules 2024, 29, 1716. [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.-Y.; Li, L.; Wu, F.; Zhang, H.-H.; Fang, J.; Zhong, Y.-S.; Yu, C.-H. Moslea Herba flavonoids alleviated influenza A virus-induced pulmonary endothelial barrier disruption via suppressing NOX4/NF-κB/MLCK pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 253, 112641. [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Qian, S.; Qian, P.; Li, X. Antiviral activity of luteolin against Japanese encephalitis virus. Virus Res. 2016, 220, 112–116. [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Bi, J.; Li, F.; Wang, S.; Huang, X.; Meng, X.; Sun, B.; Wang, D.; Kong, W.; Jiang, C.; et al. Antiviral Efficacy of Flavonoids against Enterovirus 71 Infection in Vitro and in Newborn Mice. Viruses 2019, 11, 625. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ling, Y.; Yao, Y.; Zheng, G.; Chen, W. Luteolin inhibits respiratory syncytial virus replication by regulating the MiR-155/SOCS1/STAT1 signaling pathway. Virol. J. 2020, 17, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, F.; Wang, Z.; Song, X.; Ren, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, K. Luteolin inhibits herpes simplex virus 1 infection by activating cyclic guanosine monophosphate-adenosine monophosphate synthase-mediated antiviral innate immunity. Phytomedicine 2023, 120, 155020. [CrossRef]

- Munafò, F.; Donati, E.; Brindani, N.; Ottonello, G.; Armirotti, A.; De Vivo, M. Quercetin and luteolin are single-digit micromolar inhibitors of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Yang, C.; Xia, J.; Li, N.; Xiong, W. Luteolin is a potential inhibitor of COVID-19: An in silico analysis. Medicine 2023, 102, e35029. [CrossRef]

- Shadrack, D.M.; Deogratias, G.; Kiruri, L.W.; Onoka, I.; Vianney, J.-M.; Swai, H.; Nyandoro, S.S. Luteolin: a blocker of SARS-CoV-2 cell entry based on relaxed complex scheme, molecular dynamics simulation, and metadynamics. J. Mol. Model. 2021, 27, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Xie, X.; Niu, M.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, D.; Liu, M.; Sun, R.; et al. Multi-omics blood atlas reveals unique features of immune and platelet responses to SARS-CoV-2 Omicron breakthrough infection. Immunity 2023, 56, 1410–1428.e8. [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.-L.; Liu, B.; Qin, H.-L.; Lee, S.; Wang, Y.-T.; Du, G.-H. Anti-Influenza Virus Activities of Flavonoids from the Medicinal PlantElsholtzia rugulosa. Planta Medica 2008, 74, 847–851. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Yu, C.; Yan, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, C.; Wen, X. Antiviral flavonoids from Mosla scabra. Fitoterapia 2009, 81, 429–433. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, K.; Liu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, L.; Xu, M.; Dai, X.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, H. Bioactive constituents of Mosla chinensis-cv. Jiangxiangru ameliorate inflammation through MAPK signaling pathways and modify intestinal microbiota in DSS-induced colitis mice. Phytomedicine 2021, 93, 153804. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Do, V.M.; Phan, T.T.; Huynh, D.T.N. The Potential of Ameliorating COVID-19 and Sequelae From Andrographis paniculata via Bioinformatics. Bioinform. Biol. Insights 2023, 17. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.M.; Zhou, J.; Yu, Z.; Gu, X.M.; Lu, Y.M.; Ruan, Y.M.; Wang, T.M. Exploration of Fuzheng Yugan Mixture on COVID-19 based on network pharmacology and molecular docking. Medicine 2023, 102, e32693. [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.-R.; Lin, C.-S.; Lai, H.-C.; Lin, Y.-P.; Wang, C.-Y.; Tsai, Y.-C.; Wu, K.-C.; Huang, S.-H. Antiviral activity of Sambucus FormosanaNakai ethanol extract and related phenolic acid constituents against human coronavirus NL63. Virus Res. 2019, 273, 197767–197767. [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa, R.; Morimoto, R.; Horio, Y.; Sumitani, H.; Isegawa, Y. Inhibition of influenza virus replication by Apiaceae plants, with special reference to Peucedanum japonicum (Sacna) constituents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 292, 115243. [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wang, G.; Zuo, J. Caffeic acid inhibits HCV replication via induction of IFNα antiviral response through p62-mediated Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Antivir. Res. 2018, 154, 166–173. [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, H.; Ikeda, K.; Tsujimoto, K.; Uozaki, M.; Nishide, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Koyama, A.H. Inhibition of multiplication of herpes simplex virus by caffeic acid. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2011, 28, 595–598. [CrossRef]

- Saivish, M.V.; Pacca, C.C.; da Costa, V.G.; Menezes, G.d.L.; da Silva, R.A.; Nebo, L.; da Silva, G.C.D.; Milhim, B.H.G.d.A.; Teixeira, I.d.S.; Henrique, T.; et al. Caffeic Acid Has Antiviral Activity against Ilhéus Virus In Vitro. Viruses 2023, 15, 494. [CrossRef]

- Adem, S.; Eyupoglu, V.; Sarfraz, I.; Rasul, A.; Zahoor, A.F.; Ali, M.; Abdalla, M.; Ibrahim, I.M.; A Elfiky, A. Caffeic acid derivatives (CAFDs) as inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2: CAFDs-based functional foods as a potential alternative approach to combat COVID-19. Phytomedicine 2020, 85, 153310–153310. [CrossRef]

- Liao, X.; Xin, J.; Yu, Z.; Yan, W.; Li, C.; Cao, L.; Zhang, H.; Wang, W. Unlocking the antiviral potential of rosmarinic acid against chikungunya virus via IL-17 signaling pathway. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1396279. [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; An, S.; Chu, J.; Liang, B.; Liao, Y.; Jiang, J.; Lin, Y.; Ye, L.; Liang, H. Potential Inhibitors of Monkeypox Virus Revealed by Molecular Modeling Approach to Viral DNA Topoisomerase I. Molecules 2023, 28, 1444. [CrossRef]

- Jheng, J.-R.; Hsieh, C.-F.; Chang, Y.-H.; Ho, J.-Y.; Tang, W.-F.; Chen, Z.-Y.; Liu, C.-J.; Lin, T.-J.; Huang, L.-Y.; Chern, J.-H.; et al. Rosmarinic acid interferes with influenza virus A entry and replication by decreasing GSK3β and phosphorylated AKT expression levels. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2022, 55, 598–610. [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.-Y.; Yu, Y.-J.; Jinn, T.-R. Evaluation of the virucidal effects of rosmarinic acid against enterovirus 71 infection via in vitro and in vivo study. Virol. J. 2019, 16, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhou, X.; Wang, W.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Q.; Li, J. Structural basis of rosmarinic acid inhibitory mechanism on SARS-CoV-2 main protease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2024, 724, 150230. [CrossRef]

- Elebeedy, D.; Elkhatib, W.F.; Kandeil, A.; Ghanem, A.; Kutkat, O.; Alnajjar, R.; Saleh, M.A.; El Maksoud, A.I.A.; Badawy, I.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 activities of tanshinone IIA, carnosic acid, rosmarinic acid, salvianolic acid, baicalein, and glycyrrhetinic acid between computational and in vitro insights. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 29267–29286. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ling, Y.; Yao, Y.; Zheng, G.; Chen, W. Luteolin inhibits respiratory syncytial virus replication by regulating the MiR-155/SOCS1/STAT1 signaling pathway. Virol. J. 2020, 17, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Majrashi, T.A.; El Hassab, M.A.; Mahmoud, S.H.; Mostafa, A.; Wahsh, E.A.; Elkaeed, E.B.; Hassan, F.E.; Eldehna, W.M.; Abdelgawad, S.M. In vitro biological evaluation and in silico insights into the antiviral activity of standardized olive leaves extract against SARS-CoV-2. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0301086. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, X.; Wang, E.; Yang, J.; Li, J.; Huang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, K. Neutralizing Antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron BA.1 following Homologous CoronaVac Booster Vaccination. Vaccines 2022, 10, 2111. [CrossRef]

| No. | Retention time (min) | m/z | Molecular formula | ms/ms | Compound name |

| 1 | 3.486 | 191.0199[M-H]- | C6H8O7 | 129 | Citric acid |

| 2 | 4.459 | 188.0563[M-H]- | C7H11NO5 | 128;146 | N-Acetyl-DL-glutamic acid |

| 3 | 5.71 | 117.0191[M-H]- | C4H6O4 | - | Succinic acid |

| 4 | 7.332 | 344.0389[M-H2O-H]- | C10H14N5O8P | 150; 211 | 5'-Guanylic acid |

| 5 | 7.749 | 144.0659[M-H]- | C6H11NO3 | 126 | 4-Acetamidobutyric acid |

| 6 | 14.421 | 329.0517[M-H]- | C13H14O10 | 153 | 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid 3-O-β-D-Glucuronide |

| 7 | 17.063 | 153.0194[M-H]- | C7H6O4 | 109 | 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid |

| 8 | 17.897 | 295.0464[M-H]- | C13H12O8 | 163 | Caffeoyimalic acid |

| 9 | 25.403 | 137.0237[M-H]- | C7H6O3 | - | Salicylic acid /4-Hydroxybenzoic acid |

| 10 | 26.562 | 549.2166[M+Hac-H]- | C22H34O12 | 327 | Cymorcin diglucoside |

| 11 | 28.462 | 137.0237[M-H]- | C7H6O3 | - | 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid /Salicylic acid |

| 12 | 40 | 179.0347[M-H]- | C9H8O4 | 135 | Caffeic acid |

| 13 | 40.463 | 387.1647[M+Hac-H]- | C16H24O7 | 165 | Cymorcin monoglucoside |

| 14 | 43.661 | 197.0447[M-H]- | C9H10O5 | 179;135 | Syringic Acid |

| 15 | 45.838 | 395.0931[M+H-H2O]- | C17H20N2O8S | 219 | Zileuton O-glucuronide |

| 16 | 47.368 | 517.2257[M-H]- | C24H38O12 | 385;161;205 | Cinnamoside |

| 17 | 48.619 | 387.1649[M-H]- | C18H28O9 | - | - |

| 18 | 50.148 | 239.092[M-H]- | C12H16O5 | 151;177;195 | 3-Carboxy-4-methyl-5-propyl-2-furanpropionic acid |

| 19 | 51.306 | 225.1129[M-H]- | C12H18O4 | 147 | Tuberonic acid |

| 20 | 53.809 | 593.1510[M-H]- | C27H30O15 | 353;503 | Luteolin 7-O-rutinoside |

| 21 | 62.659 | 461.0708[M-H]- | C21H18O12 | 285 | Luteolin-3'-D-glucuronide/Luteolin-7-O-glucuronide |

| 22 | 63.54 | 461.0706[M-H]- | C21H18O12 | 285 | Luteolin-3'-D-glucuronide/Luteolin-7-O-glucuronide |

| 23 | 64.744 | 447.0914[M-H]- | C21H20O11 | 285 | Luteolin-7-O-glucoside |

| 24 | 68.451 | 359.0756[M-H]- | C18H16O8 | 197 | Rosmarinic acid |

| 25 | 69.1 | 445.0755[M-H]- | C21H18O11 | 175; 269 | Apigenin-7-O-glucuronide |

| 26 | 86.106 | 285.0393[M-H]- | C15H10O6 | 267 | Luteolin |

| 27 | 93.427 | 285.0748[M+H]+ | C16H12O5 | 270 | 5,6-Dihydroxy-7-methoxyflavone |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).