Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

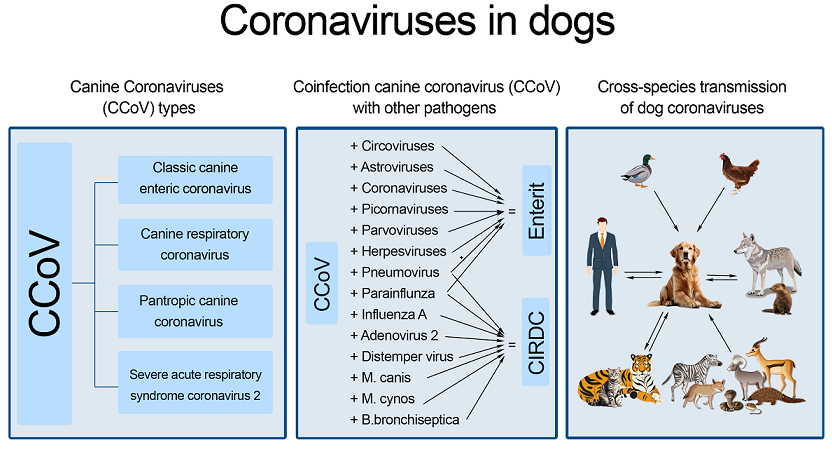

3. Coronaviruses

4. Enteric Coronavirus in Dogs

5. Canine Respiratory Coronavirus

6. Pantropic Canine Coronavirus

7. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2

8. Coinfection of CCoV with Other Pathogens

9. Cross-Species Transmission of Dog Coronaviruses

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Parkhe, P.; Verma, S. Evolution, Interspecies Transmission, and Zoonotic Significance of Animal Coronaviruses. Front Vet Sci 2021, Oct 18, 8, 719834. [CrossRef]

- Binn, L.N.; Lazar, E.C.; Keenan, K.P.; Huxsoll, D.L.; Marchwicki, R.H.; Strano, A.J. Recovery and characterization of a coronavirus from military dogs with diarrhea. Proc Annu Meet U S Anim Health Assoc 1974, 78, 359–66. http://surl.li/gfpprn.

- Decaro, N.; Buonavoglia, C. An update on canine coronaviruses: viral evolution and pathobiology. Vet Microbiol 2008, Dec 10, 132(3-4), 221-34. [CrossRef]

- Buonavoglia, C.; Decaro, N.; Martella, V.; Elia, G.; Campolo, M.; Desario, C.; Castagnaro, M.; Tempesta, M. Canine coronavirus highly pathogenic for dogs. Emerg Infect Dis 2006, 12, 492–494. [CrossRef]

- Timurkan, M.O.; Aydin, H.; Dincer, E.; Coskun, N.; Molecular characterization of canine coronaviruses: an enteric and pantropic approach. Arch Virol 2021, Jan,166(1), 35-42. [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.G.; Lu, C.P. Two genotypes of Canine coronavirus simultaneously detected in the fecal samples of healthy foxes and raccoon dogs. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Bao 2005, Apr,45,2,305-8. [Chinese] https://europepmc.org/article/med/15989282.

- Zarnke, R.L.; Evermann, J.; Ver Hoef, J.M.; McNay, M.E.; Boertje. R.D.; Gardner, C.L.; Adams, L.G.; Dale, B.W.; Burch, J. Serologic survey for canine coronavirus in wolves from Alaska. J Wildl Dis 2001, Oct, 37(4), 740-5. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, X.G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.L.; et al. A Pneumonia Outbreak Associated with a New Coronavirus of Probable Bat Origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [CrossRef]

- Malik, Y.A. Properties of Coronavirus and SARS-CoV-2. Malays J Pathol 2020, Apr, 42(1), 3-11. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32342926/.

- WHO (2003) Consensus document on the epidemiology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) available at https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70863/WHO_CDS_CSR_GAR_2... accessed on 11 November 2024.

- Pomorska-Mól, M.; Turlewicz-Podbielska, H.; Gogulski, M.; Ruszkowski, J.J.; Kubiak, M.; Kuriga, A.; Barket, P.; Postrzech M. A cross-sectional retrospective study of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in domestic cats, dogs and rabbits in Poland. BMC Vet Res 2021 Oct 7, 17(1), 322. [CrossRef]

- Subbotina, A.; Semenov, V.M.; Kupriyanov, I.I. Biological and molecular genetic features of SARS-CoV-2. Bulletin of Vitebsk State Medical University 2023, 22(6), 76-82. [in Russ]. [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.J.; Carstens, E.B. Ratification vote on taxonomic proposals to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Arch Virol 2012, 157, 1411–1422. [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.J.; Lefkowitz, E.J.; King, A.M.Q.; Bamford, D.H.; Breitbart, M.; Davison, A.J.; Ghabrial, S.A.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Knowles, N.J.; Krell, P.; et al. Ratification Vote on Taxonomic Proposals to the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Arch. Virol. 2015, 160, 1837–1850. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.L.; Pham Thi, H.H. Genome-wide comparison of coronaviruses derived from veterinary animals: A canine and feline perspective. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2021, Jun, 76, 101654. [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Mari, V.; Elia, G.; Addie, D.D.; Camero, M.; Lucente, M.S.; Martella, V.; Buonavoglia, C. Recombinant canine coronaviruses in dogs, Europe. Emerg Infect Dis 2010, Jan, 16(1), 41-7. [CrossRef]

- Regan, A.D.; Millet, J.K.; Tse, L.P.V.; Chillag, Z.; Rinaldi, V.D.; Licitra, B.N.; Dubovi, E.J.; Town, C.D.; Whittaker, G.R. Characterization of a recombinant canine coronavirus with a distinct receptor-binding (S1) domain. Virology 2012, 430(2), 90-99. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0042682212002085). [CrossRef]

- Fehr, A.R.; Perlman, S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2015, 1282, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Enjuanes, L.; Brian, D.; Cavanagh, D. et al. Family Coronaviridae. In Virus taxonomy, classification and nomenclature of viruses van Regenmortel, M.H.V.; Fauquet, C.M.; Bishop, D.H.L. et al. Eds., Academic Press, New York. 2000, pp. 835–849. http://surl.li/qrkxau.

- Lorusso, A.; Desario, C.; Mari, V.; Campolo, M.; Lorusso, E.; Elia, G.; Martella, V.; Buonavoglia, C.; Decaro, N. Molecular characterization of a canine respiratory coronavirus strain detected in Italy. Virus Res 2009, Apr, 141(1), 96-100. [CrossRef]

- Pratelli, A.; Buonavoglia, A.; Lanave, G.; Tempesta, M.; Camero, M.; Martella, V.; Decaro, N. One world, one health, one virology of the mysterious labyrinth of coronaviruses: the canine coronavirus affair. Lancet Microbe 2021, Dec, 2, 12, e646-e647. [CrossRef]

- Haake, C.; Cook, S.; Pusterla, N.; Murphy, B. Coronavirus Infections in Companion Animals: Virology, Epidemiology, Clinical and Pathologic Features. Viruses 2020, Sep, 13, 12(9), 1023. [CrossRef]

- Pratelli, A.; Tempesta, M.; Elia, G.; Martella, V.; Decaro, N.; Buonavoglia, C. The knotty biology of canine coronavirus: A worrying model of coronaviruses' danger. Res Vet Sci 2022, May, 144, 190-195. [CrossRef]

- Buonavoglia, A.; Pellegrini, F.; Decaro, N.; Galgano, M.; Pratelli, A. A One Health Perspective on Canine Coronavirus: A Wolf in Sheep's Clothing? Microorganisms 2023, Apr,2, 11(4), 921. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.E.; Islam, A.; Islam, S.; Rahman, M.K.; Miah, M.; Alam, M.S.; Rahman, M.Z. Detection and Molecular Characterization of Canine Alphacoronavirus in Free-Roaming Dogs, Bangladesh. Viruses 2021, Dec,30, 14(1), 67. [CrossRef]

- He, H.J.; Zhang, W.; Liang, J.; Lu, M.; Wang, R.; Li, G.; He, J.W.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.; Xing, G.; Chen, Y. Etiology and genetic evolution of canine coronavirus circulating in five provinces of China, during 2018-2019. Microb Pathog 2020, Aug, 145, 104209. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, C.; Guo, D.; Wang, X.; Wei, S.; Geng, Y.; Wang, E.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, X.; Su, M.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Feng, L.; Sun, D. Co-Circulation of Canine Coronavirus I and IIa/b with High Prevalence and Genetic Diversity in Heilongjiang Province, Northeast China. PLoS One 2016, Jan, 15, 11(1), e0146975. [CrossRef]

- Tennant, B.J.; Gaskell, R.M.; Jones, R.C.; et al. Studies on the epizootiology of canine coronavirus. Vet Rec 1993, 132, 7–11. [CrossRef]

- Tupler, T.; Levy, J.K.; Sabshin, S.J.; et al. Enteropathogens identified in dogs entering a Florida animal shelter with normal feces or diarrhea. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2012, 241, 338–343. [CrossRef]

- Pratelli, A. The evolutionary processes of canine coronaviruses. Adv Virol 2011, 562831. [CrossRef]

- Erles, K.; Toomey, C.; Brooks, H.W.; Brownlie, J. Detection of a group 2 coronavirus in dogs with canine infectious respiratory disease. Virology 2003, Jun,5, 310(2), 216-23. [CrossRef]

- Erles, K.; Brownlie, J. Canine respiratory coronavirus: an emerging pathogen in the canine infectious respiratory disease complex. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2008, Jul, 38(4), 815-25. [CrossRef]

- An, D.J.; Jeong, W.; Yoon, S.H.; Jeoung, H.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Park, B.K. Genetic analysis of canine group 2 coronavirus in Korean dogs. Vet Microbiol 2010, Feb, 24, 141(1-2), 46-52. [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Desario, C.; Elia, G.; Mari, V.; Lucente, M.S.; Cordioli, P.; Colaianni, M.L.; Martella, V.; Buonavoglia, C. Serological and molecular evidence that canine respiratory coronavirus is circulating in Italy. Vet Microbiol 2007, Apr,15, 121(3-4), 225-30. [CrossRef]

- Erles, K.; Shiu, K.B.; Brownlie, J. Isolation and sequence analysis of canine respiratory coronavirus. Virus Res 2007, Mar, 124(1-2), 78-87. [CrossRef]

- Yachi, A.; Mochizuki, M. Survey of dogs in Japan for group 2 canine coronavirus infection. J Clin Microbiol 2006, Jul, 44(7), 2615-8. [CrossRef]

- Kaneshima, T.; Hohdatsu, T.; Hagino, R.; Hosoya, S.; Nojiri, Y.; Murata, M.; Takano, T.; Tanabe, M.; Tsunemitsu, H.; Koyama, H. The infectivity and pathogenicity of a group 2 bovine coronavirus in pups. J Vet Med Sci 2007, Mar, 69(3), 301-3. [CrossRef]

- Okonkowski, L.K.; Szlosek, D.; Ottney, J.; Coyne, M.; Carey, S.A. Asymptomatic carriage of canine infectious respiratory disease complex pathogens among healthy dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 2021, Aug, 62(8), 662-668. [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, B.; Qin, K.; Zhao, J.; Lou, Y.; Tan, W. Discovery of a novel canine respiratory coronavirus support genetic recombination among betacoronavirus1. Virus Res 2017, Jun, 2, 237, 7–13. [CrossRef]

- Priestnall, S.L.; Brownlie, J.; Dubovi, E.J.; Erles, K. Serological prevalence of canine respiratory coronavirus. Vet Microbiol 2006, Jun, 15, 115(1-3), 43-53. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.; Anseeuw, E.; Gow, S.; Bryan, H.; Salb, A.; Goji, N.; Rhodes, C.; La Coste S.; Smits, J.; Kutz, S. Seroepidemiology of respiratory (group 2) canine coronavirus, canine parainfluenza virus, and Bordetella bronchiseptica infections in urban dogs in a humane shelter and in rural dogs in small communities. Can Vet J. 2011, Aug, 52, 8, 861–8. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22294792/.

- More, G.D.; Dunowska, M.; Acke, E.; Cave, N.J. A serological survey of canine respiratory coronavirus in New Zealand. N Z Vet J 2020, Jan, 68(1), 54-59. [CrossRef]

- Joffe, D.J.; Lelewski, R.; Weese, J.S.; Mcgill-Worsley, J.; Shankel. C.; Mendonca, S.; Sager, T.; Smith, M.; Poljak, Z. Factors associated with development of Canine Infectious Respiratory Disease Complex (CIRDCCCC) in dogs in 5 Canadian small animal clinics. Can Vet J 2016, Jan, 57(1), 46-51. https://typeset.io/papers/factors-associated-with-development-of-canine-infectious-nbfram7rhq.

- More, G.D.; Cave, N.J.; Biggs, P.J.; Acke, E.; Dunowska, M. A molecular survey of canine respiratory viruses in New Zealand. N Z Vet J 2021, Jul, 69(4), 224-233. [CrossRef]

- Wille, M.; Wensman, J.J.; Larsson, S.; van Damme, R.; Theelke, A.K.; Hayer, J.; Malmberg, M. Evolutionary genetics of canine respiratory coronavirus and recent introduction into Swedish dogs. Infect Genet Evol 2020, Aug, 82, 104290. [CrossRef]

- Poonsin, P.; Wiwatvisawakorn, V.; Chansaenroj, J.; Poovorawan, Y.; Piewbang, C.; Techangamsuwan. S. Canine respiratory coronavirus in Thailand undergoes mutation and evidences a potential putative parent for genetic recombination. Microbiol Spectr. 2023, Sep, 14, 11(5), e0226823. [CrossRef]

- De Luca, E.; Álvarez-Narváez, S.; Baptista, R.P.; Maboni, G.; Blas-Machado, U.; Sanchez, S. Epidemiologic investigation and genetic characterization of canine respiratory coronavirus in the Southeastern United States. J Vet Diagn Invest 2024, Jan, 36(1), 46-55. [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Buonavoglia, C. Canine coronavirus: not only an enteric pathogen. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2011, Nov, 41(6), 1121-32. [CrossRef]

- Gndoyan, I.A.; Dvoretskaya, Yu.A.; Solodov, E.V.; Chernov, S.A. Corneal lesions in dogs due to coronavirus infection. Veterinarian 2022, 6, 20–24. [in Russ.]. [CrossRef]

- Zappulli, V.; Caliari, D.; Cavicchioli, L.; et al. Systemic fatal type II coronavirus infection in a dog: pathological findings and immunohistochemistry. Res Vet Sci. 2008, 84, 278–282. [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Campolo, M.; Lorusso, A.; Desario, C.; Mari, V.; Colaianni, M.L.; Elia, G.; Martella, V.; Buonavoglia, C. Experimental infection of dogs with a novel strain of canine coronavirus causing systemic disease and lymphopenia. Vet Microbiol 2008, Apr, 30, 128(3-4), 253-60. [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Elia, G.; Martella, V.; Campolo, M.; Mari, V.; Desario, C.; Lucente, M.S.; Lorusso, E.; Kanellos, T.; Gibbons, R.H.; Buonavoglia, C. Immunity after natural exposure to enteric canine coronavirus does not provide complete protection against infection with the new pantropic CB/05 strain. Vaccine 2010, 28, 724–729. [CrossRef]

- Marinaro, M.; Mari, V.; Bellacicco, A.L.; Tarsitano, E.; Elia, G.; Losurdo, M.; Rezza, G.; Buonavoglia, C.; Decaro, N. Prolonged depletion of circulating CD4 T lymphocytes and acute monocytosis after pantropic canine coronavirus infection in dogs. Virus Res 2010, 152, 73–78. [CrossRef]

- Soma, T.; Ohinata, T.; Ishii, H.; Takahashi, T.; Taharaguchi, S.; Hara, M.; Detection and genotyping of canine coronavirus RNA in diarrheic dogs in Japan. Res Vet Sci 2011, Apr, 90(2), 205-7. [CrossRef]

- Zicola, A.; Jolly, S.; Mathijs, E.; et al. Fatal outbreaks in dogs associated with pantropic canine coronavirus in France and Belgium. J Small Anim Pract 2012, 53, 297–300 . [CrossRef]

- Ntafis, V.; Xylouri, E.; Mari, V.; Papanastassopoulou, M.; Papaioannou, N.; Thomas, A.; Buonavoglia, C.; Decaro, N. Molecular characterization of a canine coronavirus NA/09 strain detected in a dog’s organs. Arch Virol 2012, 157, 171–175. [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Mari, V.; von Reitzenstein, M.; Lucente, M.S.; Cirone, F.; Elia, G.; Martella, V.; King, V.L.; Di Bello, A.; Varello, K.; Zhang, S.; Caramelli, M.; Buonavoglia, C. A pantropic canine coronavirus genetically related to the prototype isolate CB/05. Vet Microbiol 2012, 159, 239–244. [CrossRef]

- Ntafis, V.; Mari, V.; Decaro, N.; Papanastassopoulou, M.; Pardali, D.; Rallis, T.S.; Kanellos, T.; Buonavoglia, C.; Xylouri, E. Canine coronavirus, Greece. Molecular analysis and genetic diversity characterization. Infect Genet Evol 2013, Jun, 16, 129-36. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L.D.; Barros, I.N.; Budaszewski, R.F.; Weber, M.N.; Mata, H.; Antunes, J.R.; Canal, C.W. Characterization of pantropic canine coronavirus from Brazil. Vet J 2014, 202(3), 659–662. [CrossRef]

- Alfano, F.; Dowgier, G.; Valentino, M.P.; Galiero, G.; Tinelli, A.; Decaro, N.; Fusco, G. Identification of pantropic canine coronavirus in a wolf (Canis lupus italicus) in Italy. J Wildl Dis 2019, 55, 504–508. [CrossRef]

- Zobba, R.; Visco, S.; Sotgiu, F.; Pinna Parpaglia, M.L.; Pittau, M.; Alberti, A. Molecular survey of parvovirus, astrovirus, coronavirus, and calicivirus in symptomatic dogs. Vet Res Commun. 2021, Feb, 45(1), 31-40. [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Mari, V.; Dowgier, G.; Elia, G.; Lanave, G.; Colaianni, M.L.; Buonavoglia, C. Full-genome sequence of pantropic canine coronavirus. Genome Announc 2015, May, 7, 3(3), e00401-15. [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Cordonnier, N.; Demeter, Z.; Egberink, H.; Elia, G.; Grellet, A.; Le Poder, S.; Mari, V.; Martella, V.; Ntafis, V.; von Reitzenstein, M.; Rottier, P.J.; Rusvai, M.; Shields, S.; Xylouri, E.; Xu, Z.; Buonavoglia, C. European surveillance for pantropic canine coronavirus. J Clin Microbiol 2013, Jan, 51(1), 83-8. [CrossRef]

- Alfano, F.; Fusco, G.; Mari, V.; Occhiogrosso, L.; Miletti, G.; Brunetti, R.; Galiero, G.; Desario, C.; Cirilli, M.; Decaro, N. Circulation of pantropic canine coronavirus in autochthonous and imported dogs, Italy. Transbound Emerg Dis 2020, Sep., 67(5), 1991-1999. [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Mari, V.; Campolo, M.; et al. Recombinant canine coronaviruses related to transmissible gastroenteritis virus of swine are circulating in dogs. J Virol 2009, 83, 1532–1537. [CrossRef]

- Erles, K.; Brownlie, J. Sequence analysis of divergent canine coronavirus strains present in a UK dog population. Virus Res. 2009, 141, 21–25. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Liu, D.; Tian, J.; Kang, H.; Guo, D.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Hu, X.; Qu, L. Molecular characterization of HLJ-073, a recombinant canine coronavirus strain from China with an ORF3abc deletion. Arch Virol. 2019, Aug, 164(8), 2159-2164. [CrossRef]

- Ntafis, V.; Mari, V.; Decaro, N.; Papanastassopoulou, M.; Papaioannou, N.; Mpatziou, R.; Buonavoglia, C.; Xylouri, E. Isolation, tissue distribution and molecular characterization of two recombinant canine coronavirus strains. Vet. Microbiol 2011, 151(3–4), 238-244. [CrossRef]

- Priestnall, S.L.; Mitchell, J.A.; Walker, C.A.; Erles, K.; Brownlie, J. New and Emerging Pathogens in Canine Infectious Respiratory Disease. Veterinary Pathology 2014, 51(2), 492-504. doi:10.1177/0300985813511130 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0300985813511130.

- Pratelli, A.; Tempesta, M.; Greco, G.; et al. Development of a nested PCR assay for the detection of canine coronavirus. J Virol Methods 1999, 80, 11–15. [CrossRef]

- Komarova, A.A., Galkina, T.S. Antigenic activity of the «Rich» strain of canine coronavirus enteritis virus in experiments with rabbits, ferrets and guinea pigs. Veterinary pathology 2023, 22 (4), 12-18. [in Russ.]. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Yang, B.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.; Huang, B.; Shi, W.; Lu, R.; Niu, P.; Zhan, F.; Ma, X.; Wang, D.; Xu, W.; Wu, G.; Gao, G.F.; Tan, W. China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020, Feb, 20, 382(8), 727-733. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) Epidemiological Updates and Monthly Operational Updates. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports accessed on 29 November 2024.

- Xu, X.; Chen, P.; Wang, J.; Feng, J.; Zhou, H.; Li, X.; Zhong, W.; Hao, P. Evolution of the novel coronavirus from the ongoing Wuhan outbreak and modeling of its spike protein for risk of human transmission. Science China. Life sciences 2020, 63(3), 457–460. [CrossRef]

- Letko, M.; Munster, V. Functional assessment of cell entry and receptor usage for lineage B β-coronaviruses, including 2019-nCoV. BiorXiv : journal 2020, 22 January, 2020.01.22.915660. doi:10.1101/2020.01.22.915660.

- Zhou, P.; Shi, Zh.-L. Discovery of a novel coronavirus associated with the recent pneumonia outbreak in humans and its potential bat origin. BiorXiv : journal 2020, 2020.01.22.914952. doi:10.1101/2020.01.22.914952.

- Gralinski, L.E.; Menachery V.D. Return of the Coronavirus : 2019-nCoV. Viruses 2020, Vol. 12, no. 2 (24 January), 135. [CrossRef]

- Enjuanes, L.; Sola, I.; Zúñiga, S.; Honrubia, J.M.; Bello-Pérez, M.; Sanz-Bravo, A.; González-Miranda, E.; Hurtado-Tamayo, J.; Requena-Platek, R.; Wang, L.; Muñoz-Santos, D.; Sánchez, C.M.; Esteban, A.; Ripoll-Gómez, J. Nature of viruses and pandemics: Coronaviruses. Curr Res Immunol 2022, 3, 151–158. [CrossRef]

- Kabbani, N.; Olds, J.L. Does COVID19 infect the brain? If so, smokers might be at a higher risk. Molecular Pharmacology: journal 2020, 1 April, vol. 97, no. 5, 351-353. [CrossRef]

- Baig, A. M. Neurological manifestations in COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics 2020, May, vol. 26, no. 5, 499—501. [CrossRef]

- Pandit, R.; Matthews, Q.L. A SARS-CoV-2: Companion Animal Transmission and Variants Classification. Pathogens 2023, May 29, 12(6), 775. [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.; Klaus, J.; Meli, M.L.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R.; SARS-CoV-2 Infektionen bei Katzen, Hunden und anderen Tieren: Erkenntnisse zur Infektion und Daten aus der Schweiz [SARS-CoV-2 infections in cats, dogs, and other animal species: Findings on infection and data from Switzerland]. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd 2021, Dec, 163(12), 821-835. [German.] . [CrossRef]

- Valencak, T.G.; Csiszar, A.; Szalai, G.; Podlutsky, A.; Tarantini, S.; Fazekas-Pongor, V.; Papp, M.; Ungvari. Z. Animal reservoirs of SARS-CoV-2: calculable COVID-19 risk for older adults from animal to human transmission. Geroscience 2021, Oct, 43(5), 2305-2320. [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.R.; Braun, E.; Ip, H.S.; Tyson, G.H. Domestic and wild animal samples and diagnostic testing for SARS-CoV-2. Vet Q 2023, Dec, 43(1), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Sun, J.; Yan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, Q.; He, W.T.; Veit, M.; Su, S. Comparison of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Spike Protein Binding to ACE2 Receptors from Human, Pets, Farm Animals, and Putative Intermediate Hosts. J Virol 2020, Jul 16, 94(15), e00831-20. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Abiko, K.; Mandai, M.; Yaegashi, N.; Konishi, I.; Highly conserved binding region of ACE2 as a receptor for SARS-CoV-2 between humans and mammals. Vet Q 2020, Dec, 40(1), 243-249. [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Ge, J.; Yu, J.; Shan, S.; Zhou, H.; Fan, S.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2020, 581, 215–220. [CrossRef]

- Kamel, M.S.; El-Sayed, A.A.; Munds, R.A.; Verma, M.S. Interactions between Humans and Dogs during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Recent Updates and Future Perspectives. Animals (Basel) 2023, Feb, 2, 13(3), 524. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/13/3/524. [CrossRef]

- Kulichenko, A.N., Maletskaya, O.V., Sarkisyan, N.S., Volynkina, A.S. COVID-19 as a Zoonotic Infection. Infection and Immunity 2021, 11 (4), 617-623. [in Russ.] https://iimmun.ru/iimm/article/view/1621. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, H.L.; Ly, H. Understanding the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) exposure in companion, captive, wild, and farmed animals. Virulence 2021, Dec, 12(1), 2777-2786. [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.; Ferdous, J.; Islam, S.; Sayeed, M.A.; Rahman, M.K.; Saha, O.; Hassan, M.M.; Shirin, T. Transmission dynamics and susceptibility patterns of SARS-CoV-2 in domestic, farmed and wild animals: Sustainable One Health surveillance for conservation and public health to prevent future epidemics and pandemics. Transbound Emerg Dis 2022, Sep, 69(5), 2523-2543. [CrossRef]

- Sharun, K.; Dhama, K.; Pawde, A.M.; Gortázar, C.; Tiwari, R.; Bonilla-Aldana, D.K.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J.; de la Fuente, J.; Michalak, I.; Attia, Y.A. SARS-CoV-2 in animals: potential for unknown reservoir hosts and public health implications. Vet Q 2021, Dec, 41(1), 181-201. [CrossRef]

- Klaus, J.; Zini, E.; Hartmann, K.; Egberink, H.; Kipar, A.; Bergmann, M.; Palizzotto, C.; Zhao, S.; Rossi, F.; Franco, V.; Porporato, F.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R. Meli ML SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Dogs and Cats from Southern Germany and Northern Italy during the First Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Viruses 2021, Jul 26, 13(8), 1453. [CrossRef]

- Michelitsch, A.; Allendorf ,V.; Conraths, F.J.; Gethmann, J.; Schulz, J.; Wernike, K.; Denzin, N. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Clinical Signs in Cats and Dogs from Confirmed Positive Households in Germany. Viruses 2023, Mar, 24, 15(4), 837. [CrossRef]

- Colitti, B.; Bertolotti, L.; Mannelli, A.; Ferrara, G.; Vercelli, A.; Grassi, A.; Trentin, C.; Paltrinieri, S.; Nogarol, C.; Decaro, N.; Brocchi, E.; Rosati, S. Cross-Sectional Serosurvey of Companion Animals Housed with SARS-CoV-2-Infected Owners, Italy. Emerg Infect Dis 2021, Jul, 27(7), 1919-1922. [CrossRef]

- Bianco, A.; Bortolami, A.; Miccolupo, A.; Sottili, R.; Ghergo, P.; Castellana, S.; Del Sambro, L.; Capozzi, L.; Pagliari, M.; Bonfante, F.; Ridolfi, D.; Bulzacchelli, C.; Giannico, A.; Parisi, A. SARS-CoV-2 in Animal Companions: A Serosurvey in Three Regions of Southern Italy. Life (Basel) 2023, Dec, 16, 13(12), 2354. [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmeier, E.; Chan, T.; Meli, M.L.; Willi, B.; Wolfensberger, A.; Reitt, K.; Hüttl, J.; Jones, S.; Tyson, G.; Hosie, M.J.; Zablotski, Y.; Hofmann-Lehmann, R. A Risk Factor Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Animals in COVID-19-Affected Households. Viruses 2023, Mar, 11, 15(3), 731. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.A.J.; Broens, E.M.; Kooistra, H.S.; De Rooij, M.M.T.; Stegeman, J.A.; De Jong, M.C.M. Contribution of cats and dogs to SARS-CoV-2 transmission in households. Front Vet Sci 2023, Jul. 14, 10, 1151772. [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, S.; Radojicic, S.; Misic, D.; Srejić, D.; Vasiljevic, D.V.; Prokic, K.; Ilić, N. Frequency of SARS-CoV-2 infection in dogs and cats: Results of a retrospective serological survey in Šumadija District, Serbia. Prev Vet Med 2022, Nov, 208, 105755. [CrossRef]

- Stevanovic, V.; Vilibic-Cavlek, T.; Tabain, I.; Benvin, I.; Kovac, S.; Hruskar, Z.; Mauric, M.; Milasincic, L.; Antolasic, L.; Skrinjaric, A.; Staresina, V.; Barbic, L. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among pet animals in Croatia and potential public health impact. Transbound Emerg Dis 2021, Jul, 68(4), 1767-1773. [CrossRef]

- Paltseva, E.D.; Pleshakova, V.I.; Rudakova, S.A. Detection of infection of companion animals with the SARS-COV-2 virus. Perm Agrarian Bulletin 2022, 3(39), 118-125. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/vyyavlenie-infitsirovannosti-zhivotnyh-kompanonov-virusom-sars-cov-2 accessed on 12 November 2024 [in Russ.].

- Kuroda, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Suzuki, H.; Park, E.S.; Ishijima, K.; Tatemoto, K.; Virhuez-Mendoza, M.; Inoue, Y.; Harada, M.; Nishino, A.; Sekizuka, T.; Kuroda, M.; Fujimoto, T.; Ishihara, G.; Horie, R.; Kawamoto, K.; Maeda, K. Pet Animals Were Infected with SARS-CoV-2 from Their Owners Who Developed COVID-19: Case Series Study. Viruses 2023, Sep, 29, 15(10), 2028. [CrossRef]

- Khalife, S.; Abdallah, M. High seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in household cats and dogs of Lebanon. Res Vet Sci 2023, Apr, 157, 13-16. [CrossRef]

- Go, Y.Y.; Carrai, M.; Choi, Y.R.; Brackman, C.J.; Tam, K.W.S.; Law, P.Y,T.; Woodhouse, F.; Gray, J.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.; Jeon, C.W.; Jang, H.; Magouras, I.; Decaro, N.; Cheng, S.M.S.; Peiris, M.; Beatty, J.A.; Barrs, V.R. Low Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies in Canine and Feline Serum Samples Collected during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Hong Kong and Korea. Viruses 2023, Feb, 20, 15(2), 582. [CrossRef]

- Sit, T.H.C.; Brackman, C.J.; Ip, S.M.; Tam, K.W.S.; Law, P.Y.T.; To, E.M.W.; Yu, V.Y.T.; Sims, L.D.; Tsang, D.N.C.; Chu, D.K.W.; Perera, R.A.P.M.; Poon, L.L.M.; Peiris, M. Infection of dogs with SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2020, Oct, 586(7831), 776-778. [CrossRef]

- AFCD. Blood test result of pet dog with low-level infection of COVID-19 released. www.afcd.gov.hk/english/publications/publications_press/pr2343.html accessed 31 March 2020.

- GHKSAR. Pet dog further tests positive for antibodies for COVID-19 virus. www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202003/26/P2020032600756.htm accessed 31 March 2020.

- Piewbang, C.; Poonsin, P.; Lohavicharn, P.; Punyathi, P.; Kesdangsakonwut, S.; Kasantikul, T.; Techangamsuwan, S. Natural SARS-CoV-2 infection in dogs: Determination of viral loads, distributions, localizations, and pathology. Acta Trop. 2024, Jan, 249, 107070. [CrossRef]

- Bae, D.Y.; Tark, D.; Moon, SH.; Oem, J.K.; Kim, W.I.; Park, C.; Na, K.J.; Park, C.K.; Oh, Y.; Cho, H.S. Evidence of Exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in Dogs and Cats from Households and Animal Shelters in Korea. Animals (Basel) 2022, Oct, 15, 12(20), 2786. [CrossRef]

- Bienzle, D.; Rousseau, J.; Marom, D.; MacNicol, J.; Jacobson, L.; Sparling, S.; Prystajecky, N.; Fraser, E.; Weese, J.S. Risk Factors for SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Illness in Cats and Dogs1. Emerg Infect Dis 2022, Jun, 28(6), 1154-1162. [CrossRef]

- Meisner, J.; Baszler, T.V.; Kuehl, K.E.; Ramirez, V.; Baines, A.; Frisbie, L.A.; Lofgren, E.T.; de Avila, D.M; Wolking, R.M.; Bradway, D.S.; Wilson, H.R.; Lipton, B.; Kawakami, V.; Rabinowitz, P.M. Household Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from Humans to Pets, Washington and Idaho, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 2022, Dec, 28(12), 2425-2434. [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Gómez, F.C.; Bautista, E.; Palacios-Cruz, O.E.; Téllez-Ramírez, A.; Vázquez-Briones, D.B.; Flores de Los Ángeles, C.; Abella-Medrano, C.A.; Escobedo-Straffón, J.L.; Aguirre-Alarcón, H.; Pérez-Silva, N.B.; Solís-Hernández, M.; Navarro-López, R.; Aguirre, A.A. Host traits, ownership behaviour and risk factors of SARS-CoV-2 infection in domestic pets in Mexico. Zoonoses Public Health 2023, Jun, 70(4), 327-340. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Figueroa, E.A.; Espinosa-Martínez, D.V.; Miranda-Ortiz, H.; Ruiz-García, E.; Figueroa-Esquivel, J.M.; Becerril-Moctezuma, M.L.; Muñoz-Rivas, A.; Ríos-Muñoz, C.A. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in companion animals from owners who tested positive for COVID-19 in the Valley of Mexico. Mol Biol Rep 2024, Jan, 25, 51(1), 186. [CrossRef]

- Calvet, G.A.; Pereira, S.A.; Ogrzewalska, M.; Pauvolid-Corrêa, A.; Resende, P.C.; Tassinari, W.S.; Costa, A.P.; Keidel, L.O.; da Rocha, A.S.B.; da Silva, M.F.B.; Dos Santos, S.A.; Lima, A.B.M.; de Moraes, I.C.V.; Mendes Junior, A.A.V.; Souza, T.D.C.; Martins, E.B.; Ornellas, R.O.; Corrêa, M.L.; Antonio, I.M.D.S.; Guaraldo, L.; Motta, F.D.C.; Brasil, P.; Siqueira, M.M.; Gremião, I.D.F.; Menezes, R.C. Investigation of SARS-CoV-2 infection in dogs and cats of humans diagnosed with COVID-19 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS One 2021, Apr, 28, 16(4), e0250853. [CrossRef]

- Santos, H.O.; Santos, E.M.S.; de Oliveira, H.D.S.; Dos Santos, W.S.; Tupy, A.A.; Souza, E.G.; Ramires, R.; Luiz, A.C.O.; de Almeida, A.C. Screening for canine coronavirus, canine influenza virus, and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 in dogs during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic. Vet World 2023, Sep, 16(9), 1772-1780. [CrossRef]

- Galhardo, J.A.; Barbosa, D.S.; Kmetiuk, L.B.; de Carvalho, O.V.; Teixeira, A.I.P.; Fonseca, P.L.C.; de Araújo, E.; Santos, L.C.G.; Queiroz, D.C.; Miranda, J.V.O.; da Silva Filho, A.P.; Castillo, A.P.; Araujo, R.N.; da Silveira, J.A.G.; Ristow, L.E.; Brandespim, D.F.; Pettan-Brewer, C.; de Sá Guimarães, A.M.; Dutra, V.; de Morais, H.A.; Dos Santos, A.P.; Agopian, R.G.; de Aguiar, R.S.; Biondo, A.W. Molecular detection and characterization of SARS-CoV-2 in cats and dogs of positive owners during the first COVID-19 wave in Brazil. Sci Rep 2023, Sep, 2, 13(1), 14418. [CrossRef]

- Alberto-Orlando, S.; Calderon, J.L.; Leon-Sosa, A.; Patiño, L.; Zambrano-Alvarado, M.N.; Pasquel-Villa, L.D.; Rugel-Gonzalez, D.O.; Flores, D.; Mera, M.D.; Valencia, P.; Zuñiga-Velarde, J.J.; Tello-Cabrera, C.; Garcia-Bereguiain, M.A. SARS-CoV-2 transmission from infected owner to household dogs and cats is associated with food sharing. Int J Infect Dis 2022, Sep, 122, 295-299. [CrossRef]

- Gautam, A.; Kaphle, K.; Shrestha, B.; Phuyal, S. Susceptibility to SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 from animal health perspective. Open Vet J 2020, Aug, 10(2), 164-177. [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo Hernández, D.A.; Chacón, M.C.; Velásquez, M.A.; Vásquez-Trujillo, A.; Sánchez, A.P.; Salazar Garces, L.F.; García, G.L.; Velasco-Santamaría, Y.M.; Pedraza, L.N.; Lesmes-Rodríguez, L.C. Seroprevalence of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 in domestic dogs and cats and its relationship with COVID-19 cases in the city of Villavicencio, Colombia. F1000Res. 2023, Aug 10, 11, 1184. [CrossRef]

- Molini, U.; Coetzee, L.M.; Engelbrecht, T.; de Villiers, L.; de Villiers, M.; Mangone, I.; Curini, V.; Khaiseb, S.; Ancora, M.; Cammà, C.; Lorusso, A.; Franzo, G.; SARS-CoV-2 in Namibian Dogs. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, Dec 13, 10(12), 2134. [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmeier, E.; Chan, T.; Agüí, C.V.; Willi, B.; Wolfensberger, A.; Beisel, C.; Topolsky, I.; Beerenwinkel, N.; Stadler, T. Detection and Molecular Characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta Variant and the Specific Immune Response in Companion Animals in Switzerland. Viruses. 2023, 15(1), 245. [CrossRef]

- Akhtardanesh, B.; Jajarmi, M.; Shojaee, M.; Salajegheh Tazerji, S.; Khalili Mahani, M.; Hajipour, P.; Gharieb, R. Molecular screening of SARS-CoV-2 in dogs and cats from households with infected owners diagnosed with COVID-19 during Delta and Omicron variant waves in Iran. Vet Med Sci 2023, Jan, 9(1), 82-90. [CrossRef]

- Agüero, B.; Berrios, F.; Pardo-Roa, C.; Ariyama, N.; Bennett, B.; Medina, R.A.; Neira, V. First detection of Omicron variant BA.4.1 lineage in dogs, Chile. Vet Q 2024, Dec, 44(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Tinto, B.; Revel, J.; Virolle, L.; Chenet, B.; Reboul Salze, F.; Ortega, A.; Beltrame, M.; Simonin, Y. Monitoring SARS-CoV-2 Seroprevalence in Domestics and Exotic Animals in Southern France. Trop Med Infect Dis 2023, Aug 25, 8(9), 426. [CrossRef]

- IDEXX. Leading veterinary diagnostic company sees no COVID-19 cases in pets. www.idexx.com/en/about-idexx/news/no-covid-19-cases-pets (accessed 31 March 2020).

- Johansen, M.D., Irving, A., Montagutelli, X. et al. Animal and translational models of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19. Mucosal Immunol 2020, 13, 877–891. [CrossRef]

- Almendros, A.; Gascoigne, E. Can companion animals become infected with Covid-19? Vet Rec 2020, Apr 4, 186(13), 419-420. [CrossRef]

- Michael, H.T.; Waterhouse, T.; Estrada, M.; Seguin, M.A. Frequency of respiratory pathogens and SARS-CoV-2 in canine and feline samples submitted for respiratory testing in early 2020. J Small Anim Pract 2021, May, 62(5), 336-342. [CrossRef]

- Piewbang, C.; Poonsin, P.; Lohavicharn, P.; Wardhani, S.W.; Dankaona, W.; Puenpa, J.; Poovorawan, Y.; Techangamsuwan, S. SARS-CoV-2 Transmission from Human to Pet and Suspected Transmission from Pet to Human, Thailand. J Clin Microbiol 2022, Nov 16, 60(11), e0105822. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wen, Z.; Zhong, G.; Yang, H.; Wang, C.; Huang, B.; Liu, R.; He, X.; Shuai, L.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, P.; Liang, L.; Cui, P.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Guan, Y.; Tan, W.; Wu, G.; Chen, H.; Bu, Z. Susceptibility of ferrets, cats, dogs, and other domesticated animals to SARS-coronavirus 2. Science 2020, May 29, 368(6494), 1016-1020. [CrossRef]

- Andreeva, A.V.; Nikolaeva, O.N. New coronavirus infection (COVID-19) in animals. Veterinarian 2021, 2, 4–11. [in Russ.]. [CrossRef]

- Temmam, S., Vongphayloth, K., Baquero, E. et al. Bat coronaviruses related to SARS-CoV-2 and infectious for human cells. Nature 2022, 604, 330–336. [CrossRef]

- Sparrer, M.N.; Hodges, N.F.; Sherman, T.; VandeWoude, S.; Bosco-Lauth, A.M.; Mayo, C.E. Role of Spillover and Spillback in SARS-CoV-2 Transmission and the Importance of One Health in Understanding the Dynamics of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Clin. Microbiol 2023, e0161022. [CrossRef]

- Brüssow, H. Viral infections at the animal–human interface-Learning lessons from the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Microb. Biotechnol. 2023, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.F.W.; Siu, G.K.H.; Yuan, S.; Ip, J.D.; Cai, J.P.; Chu, A.W.H.; Chan, W.M.; Abdullah S.M.U.; Luo, C.; Chan, B.P.C.; et al. Probable Animal-to-Human Transmission of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Delta Variant AY.127 Causing a Pet Shop-Related Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in Hong Kong. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75:e76–e81. [CrossRef]

- Yen, H.L.; Sit, T.H.C.; Brackman, C.J.; Chuk, S.S.Y.; Gu, H.; Tam, K.W.S.; Law, P.Y.T.; Leung, G.M.; Peiris, M.; Poon, L.L.M. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (AY.127) from pet hamsters to humans, leading to onward human-to-human transmission: A case study. Lancet. 2022,399:1070–1078. [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Shan, K.J.; Wang, W.; Zhang, S.; Huan, Q.; Qian, W. Evidence for a mouse origin of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. J. Genet. Genom. 2021, 48:1111–1121. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Dhama, K.; Sharun, K.; Iqbal Yatoo, M.; Malik, Y.S.; Singh, R.; Michalak, I.; Sah, R.; Bonilla-Aldana, D.K.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. COVID-19: animals, veterinary and zoonotic links. Vet Q 2020, Dec,40(1),169-182. [CrossRef]

- Salajegheh Tazerji, S.; Magalhães Duarte, P.; Rahimi, P.; Shahabinejad, F.; Dhakal, S.; Singh Malik, Y.; Shehata, A.A.; Lama, J.; Klein, J.; Safdar, M.; Rahman, M.T.; Filipiak, K.J.; Rodríguez-Morales, A.J.; Sobur, M.A.; Kabir, F.; Vazir, B.; Mboera, L.; Caporale, M.; Islam, M.S.; Amuasi, J.H.; Gharieb, R.; Roncada, P.; Musaad, S.; Tilocca, B.; Koohi, M.K.; Taghipour, A.; Sait, A.; Subbaram, K.; Jahandideh, A.; Mortazavi, P.; Abedini, M.A.; Hokey, D.A.; Hogan, U.; Shaheen, M.N.F.; Elaswad, A.; Elhaig, M.M.; Fawzy, M. Transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) to animals: an updated review. J Transl Med 2020, Sep 21,18(1),358. [CrossRef]

- Salajegheh Tazerji, S.; Gharieb, R.; Ardestani, M.M.; Akhtardanesh, B.; Kabir, F.; Vazir, B.; Duarte, P.M.; Saberi, N.; Khaksar, E.; Haerian, S.; Fawzy, M. The risk of pet animals in spreading severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and public health importance: An updated review. Vet Med Sci 2024, Jan,10(1),e1320. [CrossRef]

- Reagan, K.L.; Sykes, J.E. Canine Infectious Respiratory Disease. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2020, Mar,50(2),405-418. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.A.; Cardwell, J.M.; Leach, H.; Walker, C.A.; Le Poder, S.; Decaro, N.; Rusvai, M.; Egberink, H,; Rottier, P.; Fernandez, M.; Fragkiadaki, E.; Shields, S.; Brownlie, J. European surveillance of emerging pathogens associated with canine infectious respiratory disease. Vet Microbiol 2017, Dec,212,31-38. [CrossRef]

- Decaro, N.; Mari, V.; Larocca, V.; Losurdo, M.; Lanave, G.; Lucente, M.S.; Corrente, M.; Catella, C.; Bo, S.; Elia, G.; Torre, G.; Grandolfo, E.; Martella, V.; Buonavoglia, C. Molecular surveillance of traditional and emerging pathogens associated with canine infectious respiratory disease. Vet Microbiol 2016, Aug 30,192,21-25. [CrossRef]

- Erles, K.; Dubovi, E.J.; Brooks, H.W.; Brownlie, J. Longitudinal study of viruses associated with canine infectious respiratory disease. J Clin Microbiol 2004, Oct,42(10),4524-9. [CrossRef]

- Erles, K.; Brownlie, J. Investigation into the causes of canine infectious respiratory disease: antibody responses to canine respiratory coronavirus and canine herpesvirus in two kennelled dog populations. Arch Virol 2005, Aug,150(8),1493-504. [CrossRef]

- Schulz, B.S.; Kurz, S.; Weber, K.; Balzer, H.J.; Hartmann, K. Detection of respiratory viruses and Bordetella bronchiseptica in dogs with acute respiratory tract infections. Vet J 2014, Sep,201(3),365-9. [CrossRef]

- Sowman, H.R.; Cave, N.J.; Dunowska, M. A survey of canine respiratory pathogens in New Zealand dogs. N Z Vet J 2018, Sep,66(5),236-242. [CrossRef]

- Piewbang, C.; Rungsipipat, A.; Poovorawan, Y.; Techangamsuwan, S. Cross-sectional investigation and risk factor analysis of community-acquired and hospital-associated canine viral infectious respiratory disease complex. Heliyon 2019, Nov 14,5(11),e02726. [CrossRef]

- Maboni, G; Seguel, M.; Lorton, A.; Berghaus, R.; Sanchez, S. Canine infectious respiratory disease: New insights into the etiology and epidemiology of associated pathogens. PLoS One 2019, Apr 25,14(4),e0215817. [CrossRef]

- Bryan, H.M.; Darimont, C.T.; Paquet, P.C.; Ellis, J.A.; Goji, N.; Gouix, M.; Smits, J.E. Exposure to infectious agents in dogs in remote coastal British Columbia: Possible sentinels of diseases in wildlife and humans. Can J Vet Res 2011, Jan, 75(1), 11-7. https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/zoodis/1/ accessed on 29 November 2024.

- Shi, Y.; Tao, J.; Li, B.; Shen, X.; Cheng, J.; Liu, H. The Gut Viral Metagenome Analysis of Domestic Dogs Captures Snapshot of Viral Diversity and Potential Risk of Coronavirus. Front Vet Sci 2021, Jul 7, 8 695088. [CrossRef]

- Yondo, A.; Kalantari, A.A.; Fernandez-Marrero, I.; McKinney, A.; Naikare, H.K.; Velayudhan, B.T. Predominance of Canine Parainfluenza Virus and Mycoplasma in Canine Infectious Respiratory Disease Complex in Dogs. Pathogens 2023, Nov 15, 12(11), 1356. [CrossRef]

- Nikonenko, T.B.; Baryshnikov, P.I.; Novikov, N.A. Microbiocenoses in viral intestinal infections of dogs in the Baikal region. Bulletin of the Altai State Agrarian University 2021. 1 (195), 83-88. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/mikrobiotsenozy-pri-virusnyh-kishechnyh-infektsiyah-sobak-v-usloviyah-pribaykalya accessed on 12 November 2024 [in Russ.].

- Woolhouse, M.E.; Gowtage-Sequeria, S. Host range and emerging and reemerging pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis 2005, Dec,11(12),1842-7. [CrossRef]

- McMahon, B.J.; Morand, S.; Gray, J.S. Ecosystem change and zoonoses in the Anthropocene. Zoonoses Public Health 2018, Nov, 65(7), 755-765. [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, F.; Omar, A.H.; Buonavoglia, C.; Pratelli, A. SARS-CoV-2 and Animals: From a Mirror Image to a Storm Warning. Pathogens 2022, Dec 12, 11(12), 1519. [CrossRef]

- Shamenova, M.; Lukmanova, G.; Klivleyeva, N.; Glebova, T.; Saktaganov, N.; Baimukhametova, A.; Vetrova, E. Interspecies Transmission and Adaptation of Influenza Virus to Dogs. Microbiology and Virology 2024, 1(44), 22–41. https://imv-journal.kz/index.php/mav/article/view/215. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhao, P.; Xu, P.; Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, Z.; Yang, J. A comprehensive dataset of animal-associated sarbecoviruses. Sci Data 2023, Oct 7, 10(1), 681. [CrossRef]

- Yesilbag, K.; Aytogu, G. Coronavirus host divergence and novel coronavirus (Sars-CoV-2) outbreak. Clin Exp Ocul Trauma Infect 2020, 2(1), 139–147. https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/1081346 accessed on 11 November 2024.

- Lorusso, A.; Calistri, P.; Petrini, A.; Savini, G.; Decaro, N. Novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) epidemic: a veterinary perspective. Vet Ital 2020, 56(1), 5–10. [CrossRef]

- Klivleyeva, N.; Lukmanova, G.; Glebova, T.; Shamenova, M.; Ongarbayeva, N.; Saktaganov, N.; Baimukhametova, A.; Baiseiit, S.; Ismagulova, D.; Kassymova, G.; Rachimbayeva, A.; Murzagaliyeva, A.; Xetayeva, G.; Isabayeva, R.; Sagatova, M. Spread of Pathogens Causing Respiratory Viral Diseases Before and During CoVID-19 Pandemic in Kazakhstan. Indian J Microbiol 2023, February. [CrossRef]

- Klivleyeva, N.G.; Ongarbayeva, N.S.; Korotetskiy, I.S.; Glebova, T.I.; Saktaganov, N.T.; Shamenova, M.G.; Baimakhanova, B.B.; Shevtsov, A.B.; Amirgazin, A.; Berezin, V.E.; et al. Coding-Complete Genome Sequence of Swine Influenza Virus Isolate A/Swine/Karaganda/04/2020 (H1N1) from Kazakhstan. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2021, 10, e0078621. [CrossRef]

- Saktaganov, N.T.; Klivleyeva, N.G.; Ongarbayeva, N.S.; Glebova, T.I.; Lukmanova, G.V.; Baimukhametova, A.M. Study on Antigenic Relationships and Biological Properties of Swine Influenza a/H1n1 Virus Strains Isolated in Northern Kazakhstan in 2018. Sel'skokhozyaistvennaya Biol. 2020, 55, 355–363. [CrossRef]

- Klivleyeva, N.G.; Glebova, T.I.; Shamenova, M.G.; Saktaganov, N.T. Influenza A viruses circulating in dogs: A review of the scientific literature. Open Veterinary Journal 2022, 12(5), 676–687. [CrossRef]

- Licitra, B.N.; Duhamel, G.E.; Whittaker, G.R. Canine enteric coronaviruses: emerging viral pathogens with distinct recombinant spike proteins. Viruses 2014, 6, 3363–3376. [CrossRef]

- Esposito, A.M.; Esposito, M.M.; Ptashnik, A. Phylogenetic Diversity of Animal Oral and Gastrointestinal Viromes Useful in Surveillance of Zoonoses. Microorganisms 2022, Sep 10, 10(9), 1815. [CrossRef]

- Klivleyeva N, Saktaganov N, Glebova T, Lukmanova G, Ongarbayeva N, Webby R. Influenza A Viruses in the Swine Population: Ecology and Geographical Distribution. Viruses 2024, 16(11), 1728. [CrossRef]

- Glebova, T.I.; Klivleyeva, N.G.; Saktaganov, N.T.; Shamenova, M.G.; Lukmanova, G.V.; Baimukhametova, A.M.; Baiseiit, S.B.; Ongarbayeva, N.S.; Orynkhanov, K.A.; Ametova, A.V.; Ilicheva, A.K. Circulation of influenza viruses in the dog population in Kazakhstan (2023–2024), Open Veterinary Journal 2024, 14(8), 1896-1904 . [CrossRef]

- Lukmanova, G.; Klivleyeva, N.; Glebova, T.; Ongarbayeva, N.; Shamenova, M.; Saktaganov, N.; Baimukhametova, A.; Baiseiit, S.; Ismagulova, D.; Ismailov, E.; et al. Influenza A Virus Surveillance in Domestic Pigs in Kazakhstan 2018-2021. Ciênc. Rural 2024, 54(10), e20230403. [CrossRef]

- Glebova T.I., Klivleyeva N.G., Baimukhametova A.M., Saktaganov N.T., Lukmanova G.V., Ongarbayeva N.S., Shamenova M.G., Baimakhanova B.B. Circulation of influenza viruses in the epidemic season of 2018–2019 among people residing in Northern and Western Kazakhstan. Infekc. bolezni (Infectious diseases). 2021, 19(2), 70–75. [in Russ]. [CrossRef]

- Khalil, A.M.; Martinez-Sobrido, L.; Mostafa, A. Zoonosis and zooanthroponosis of emerging respiratory viruses. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2024, Jan 5, 13, 1232772. [CrossRef]

- Vlasova A.N., Diaz A., Damtie D., Xiu L., Toh T.-H., Soon-Yit Lee J., Saif L. J, Gray G.C., Novel Canine Coronavirus Isolated from a Hospitalized Patient With Pneumonia in East Malaysia, Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2022, 74(3), 446–454, . [CrossRef]

- Lednicky, J.A.; Tagliamonte, M.S.; White, S.K.; Blohm, G.M.; Alam, Md. M.; Iovine, N.M.; Salemi, M.; Mavian, C.; Morris G. J. Isolation of a Novel Recombinant Canine Coronavirus From a Visitor to Haiti: Further Evidence of Transmission of Coronaviruses of Zoonotic Origin to Humans, Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2022, 75(1), e1184–e1187, . [CrossRef]

- Domańska-Blicharz, K.; Woźniakowski, G.; Konopka, B.; Niemczuk, K.; Welz, M.; Rola, J.; Socha, W.; Orłowska, A.; Antas, M.; Śmietanka, K.; et al. Animal Coronaviruses in the Light of COVID-19. J. Vet. Res. 2020, 64, 333–345. [CrossRef]

- Pratelli, A. Genetic evolution of canine coronavirus and recent advances in prophylaxis. Vet Res. 2006, 37, 191–200. [CrossRef]

- USDA Confirmation of COVID-19 in Pet Dog in New York. Available online: https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USDAAPHIS/bulletins/28ead4f accessed on 1 September 2021.

- Liew, A.Y.; Carpenter, A.; Moore, T.A.; Wallace, R.M.; Hamer, S.A.; Hamer, G.L.; Fischer, R.S.B.; Zecca, I.B.; Davila, E.; Auckland, L.D. Clinical and epidemiologic features of SARS-CoV-2 in dogs and cats compiled through national surveillance in the United States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2023, 261, 480–489. [CrossRef]

- USDA Confirmed Cases of SARS-CoV-2 in Animals in the United States. Available online: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/dashboards/tableau/sars-dashboard. accessed on 15 May 2023.

- Hamer, S.A.; Ghai, R.R.; Zecca, I.B.; Auckland, L.D.; Roundy, C.M.; Davila, E.; Busselman, R.E.; Tang, W.; Pauvolid-Corrêa, A.; Killian, M.L. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 variant of concern detected in a pet dog and cat after exposure to a person with COVID-19, USA. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2022, 69, 1656–1658. [CrossRef]

- Wendling, N.M.; Carpenter, A.; Liew, A.; Ghai, R.R.; Gallardo-Romero, N.; Stoddard, R.A.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Retchless, A.C.; Ahmad, A. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant (B.1.617.2) from a fully vaccinated human to a canine in Georgia, July 2021. Zoonoses Public Health 2022, 69, 587–592. [CrossRef]

- Doerksen, T.; Lu, A.; Noll, L.; Almes, K.; Bai, J.; Upchurch, D.; Palinski, R. Near-Complete Genome of SARS-CoV-2 Delta (AY.3) Variant Identified in a Dog in Kansas, USA. Viruses 2021, 13, 2104. [CrossRef]

- Sila, T.; Sunghan, J.; Laochareonsuk, W.; Surasombatpattana, S.; Kongkamol, C.; Ingviya, T.; Siripaitoon, P.; Kositpantawong, N.; Kanchanasuwan, S.; Hortiwakul, T.; et al. Suspected Cat-to-Human Transmission of SARS-CoV-2, Thailand, July–September 2021. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 1485–1488. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, T.; Saxena, S.K. Transmission Cycle of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. In Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapeutics., S. K. Saxena Eds.; Springer Science and Business Media, LLC, Singapore, 2020, 33–42. [CrossRef]

- Plowright, R.K.; Parrish, C.R.; McCallum, H.; Hudson, P.J.; Ko, A.I.; Graham, A.L.; et al. Pathways to zoonotic spillover. Nat Rev Microbiol 2017, 15, 502–10. [CrossRef]

- Jelinek, H.F.; Mousa, M.; Alefishat, E.; Osman, W.; Spence, I.; Bu, D.; Feng, S.F.; Byrd, J.; Magni, P.A.; Sahibzada, S.; Tay, G.K.; Alsafar, H.S. Evolution, Ecology, and Zoonotic Transmission of Betacoronaviruses: A Review. Front Vet Sci 2021, May 20, 8, 644414. [CrossRef]

- Fang, R.; Yang, X.; Guo, Y.; Peng, B.; Dong, R.; Li, S.; Xu, S. SARS-CoV-2 infection in animals: Patterns, transmission routes, and drivers. Eco Environ Health 2023, Oct 13, 3(1), 45-54. [CrossRef]

- Colina, S.E.; Serena, M.S.; Echeverría, M.G.; Metz, G.E. Clinical and molecular aspects of veterinary coronaviruses. Virus Res 2021, May, 297, 198382. [CrossRef]

- Daszak, P.; Cunningham, A.A.; Hyatt, A.D. Emerging infectious diseases of wildlife-threats to biodiversity and human health. Science 2000, Jan 21, 287(5452), 443-9. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Xing, X.; Sun, D. A Mini-Review on the Common Antiviral Drug Targets of Coronavirus. Microorganisms 2024, Mar 17, 12(3)m 600. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).