Generalised Additive Models (GAMs)

Mean Parameter Estimation

For the estimation of the C was based on R

2, GCV scores, and model complexity. Among the 255 models, eight were considered and after performing LOO validation, the significant predictor variables for each model were identified based on p-value (0.05 significance level) as shown in

Table 3.

Interestingly, Model 3 and Model 6 revealed significance in all their predictor variables, highlighting their strong relationship with the mean parameter. For Model 3, the parametric coefficients were estimated, with both 'area' and 'I62' demonstrating significant effects on the mean. From

Table 4, the R

2 value was 0.60, indicating that 60% of the variance in the mean was explained. The GCV score was 2208814.13. The analysis revealed that both 'area' and 'I62' had statistically significant relationships with the mean parameter.

Model 6 indicated that 'area', 'I62', and 'MAE' were all significant predictors of the mean parameter. From

Table 4, the R

2 value increased to 0.70, indicating that the model explained 70% of the variance in the mean. The GCV score decreased to 483878.03. The analysis highlighted the combined influence of 'area', 'I62', and 'MAE' in predicting the mean parameter.

Among all the models, Model 6 appears to be the best choice, as it has the highest R2 value, the lowest GCV score, a lower AIC, and a lower value for df residual. However, Model 3 is less complex. Both Model 6 and Model 3 are taken into consideration in building the models.

LCV Parameter Estimation

Similarly, various models were assessed for their ability to estimate LCV while considering model complexity, goodness-of-fit metrics, and significance of predictor variables. The best eight different GAMs were chosen to estimate LCV using various predictor variables. After performing LOO validation, the significant predictor variables for each model were determined based on p-values (0.05 significance level). The models, along with their significant predictor variables, are summarised in

Table 5. Notably, Model 3 and Model 8 revealed significance in all their predictor variables, indicating a strong relationship with the LCV variable.

To evaluate the performance of these models, several metrics were considered, including AIC and df residual and goodness-of-fit statistics such as R

2 and GCV scores (as shown in

Table 6). Model 3 appears to be the most suitable choice for estimating LCV, with a good R

2 value (0.53), a low GCV score (0.16), a low AIC (-184.08), and a low value for residual (70.41). This indicates that Model 3 provides the best balance between goodness of fit and model complexity. On the other hand, Model 8 offers a good option due to its simplicity with an R

2 of 0.17 and a GCV score of 4.36. Both models 3 and 8 are taken in consideration in building the models.

LSK Parameter Estimation

Likewise, different models were evaluated in terms of their ability to predict LSK, taking into account the same factors such as model complexity, metrics indicating goodness of fit, and the importance of predictor variables. Eight distinct GAMs were developed to predict LSK, incorporating a variety of predictor variables. The summary in

Table 7 outlines the models and highlights their significant predictor variables.

After LOO validation, the models were compared based on their R

2 values, GCV, AIC and df residual as shown in

Table 8.

Among the models, Model 7 stands out as the most promising with a R2 value of 0.33, signifying that approximately 33% of the variability in LSK is explained by the model. Moreover, the GCV score for Model 7 was notably lower than that of other alternatives, indicating its effectiveness in minimising overfitting. Additionally, the model had a lower AIC and a reduced df residual. Overall, Model 7 demonstrated a significant impact of I62 and SF on LSK prediction. Both terms are statistically significant based on their p-values. On the other hand, Model 8, while less complex, still explains 17% of the deviance with a focus on I62. Both model 7 and 8 are taken in consideration in building the models.

Evaluation of GAM Model Combinations for Quantile Prediction

To explore the effectiveness of GAM analysis in quantile prediction, eight distinct combinations, denoted as GAM (a) through GAM (h), are assessed to determine their predictive capabilities. Each combination comprises specific models for Mean, LCV and LSK. They are as follow:

GAM (a): Mean (model 3) – LCV (model 8) – LSK (model 7)

GAM (b): Mean (model 3) – LCV (model 8) – LSK (model 8)

GAM (c): Mean (model 3) – LCV (model 3) – LSK (model 7)

GAM (d): Mean (model 3) – LCV (model 3) – LSK (model 8)

GAM (e): Mean (model 6) – LCV (model 8) – LSK (model 7)

GAM (f): Mean (model 6) – LCV (model 8) – LSK (model 8)

GAM (g): Mean (model 6) – LCV (model 3) – LSK (model 7)

GAM (h): Mean (model 6) – LCV (model 3) – LSK (model 8)

To determine the best combinations among the GAM models, the median of the ratio of observed to predicted values (Qobs/Qpred) and the median REr% for each combination were compared. As shown in

Table 9, for the median ratio, combinations e, f, g, and h demonstrated median ratios close to 1, suggesting a good balance between observed and predicted values. Conversely, combinations a, b, c, and d had median ratios slightly higher than 1, indicating slightly overestimated predictions. Regarding the median REr%, combinations e, f, g, and h exhibited the lowest values across all quantiles, indicating the lowest percentage of relative errors. In contrast, combinations a, b, c, and d had higher median REr% values, indicating higher relative errors in prediction. Overall, combinations e, f, g, and h performed better than combinations a, b, c, and d in terms of both median ratio and median REr%.

Log-Log Linear:

Mean Parameter Estimation

For the estimation of the mean parameter using log-log linear, nine models were evaluated to determine the best predictor variables. After conducting LOO validation, these models (presented in

Table 10) were assessed based on their significant predictor variables and overall performance.

The best models, based on the significant predictor variables and less complexity, were models 3 and 4. Model 3 included the predictor variables log(area) and log(I62), while model 4 incorporated log(area), log(I62), and log(SF) as significant predictors. From

Table 11, Model 3 showed a R

2 value of 0.75, indicating a good fit and demonstrating that the selected predictor variables explained a significant proportion of the variance in the mean parameter. Model 4 exhibited a slightly higher R

2 value of 0.76, suggesting that the addition of log(SF) as a predictor improved the model's performance. It also had a lower AIC and BIC, indicating strong explanatory power.

Overall, models 3 and 4 will be taken into consideration in building the log-log models.

LCV Parameter Estimation

In this section, log-log linear models were employed to estimate the LCV parameter. Nine models were evaluated to determine the best predictor variables for LCV. After conducting LOO validation, nine models (presented in

Table 12) were assessed based on their significant predictor variables and overall performance.

From

Table 13, Model 8, which used "log(I62)" as the only predictor variable, showed an R

2 value of 0.09. While Model 8's R

2 value is relatively low, it was the best-performing model among the options available. This model is characterised by simplicity with a single predictor variable, "log(I62)" and therefore, it is the most suitable choice for estimating LCV using the log-log linear approach.

LSK Parameter Estimation

In this section, log-log linear models were used to estimate the LSK parameter. Nine models were assessed to determine the best predictor variables for LSK. After conducting LOO validation, these models were evaluated based on their significant predictor variables and overall performance (see

Table 14).

While Model 8's adjusted R

2 value is relatively low (as shown in

Table 15), it was the best-performing model among the available options. Same as LCV, model 8 is the most suitable choice for estimating LSK using log-log linear due to its simplicity and relationship.

Evaluation of log-log Model Combinations for Quantile Prediction:

To investigate the effectiveness of log-log analysis in quantiles prediction, two specific combinations, denoted as log-log (i) and log-log (j) were examined for estimating quantiles using the Mean (from Model 3 and 4), LCV (from Model 8), and LSK (from Model 8) parameters. The combinations are as below:

Log – log (i): Mean (Model 3) – LCV (Model 8) – LSK (Model 8)

Log – log (j): Mean (Model 4) – LCV (Model 8) – LSK (Model 8)

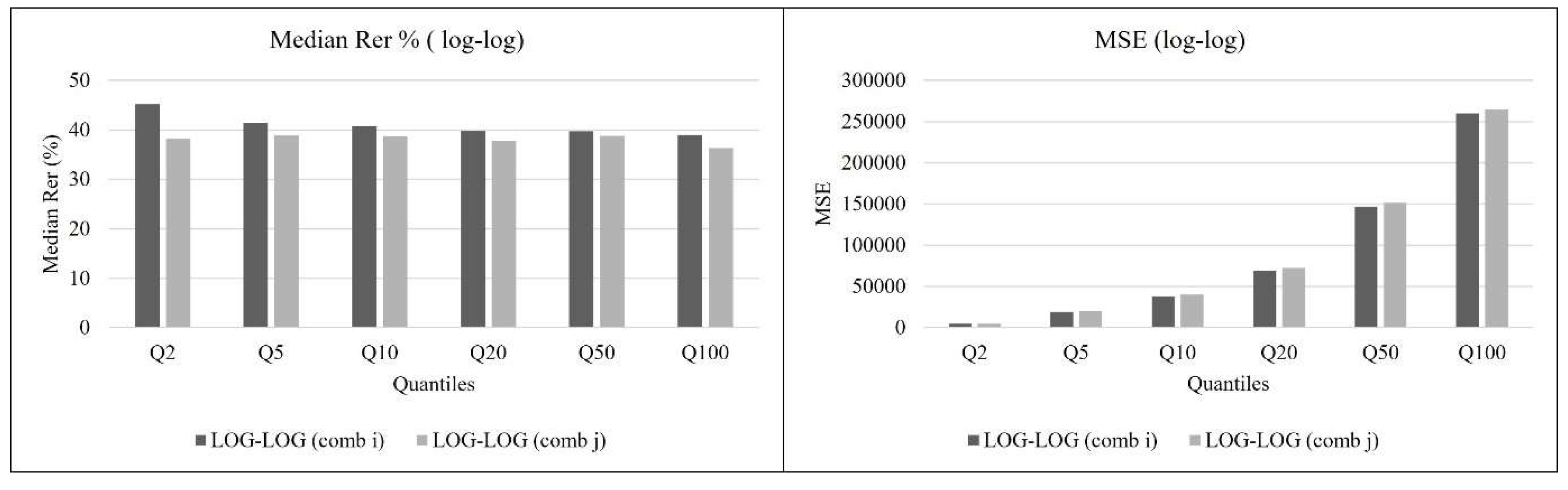

For log-log (i), the median REr, expressed as percentage, ranges from 38.92% to 45.19% and the MSE ranges from y 4493.74 to 259758.43 across different quantiles. While for log-log (j), the median REr ranges from approximately 36.32% to 38.84% with the MSE ranging from approximately 4930.74 to 265092.08 across different quantiles.

Figure 2 shows that the median REr and MSE for both models are relatively close to each other across different quantiles. This suggests that both combinations are effective in estimating quantiles using the Mean, LCV, and LSK parameters.

Comparison between GAM and Log-Log:

In summary, both GAMs and log-log linear models showed promising results for estimating different parameters (mean, LCV, and LSK). The choice between them depends on factors like model complexity, goodness of fit, and specific data characteristics.

Table 16 presents a comparison between GAM and log-log models, focusing on median REr% across the six quantiles Q

2 to Q

100. The median REr% ranges from 33% to 39% for GAM and from 35% to 45% for log-log models. Analysis of the minimum error reveals that, except for Q100, GAM generally exhibits lower median REr% compared to log-log, suggesting a better performance in most cases. Similarly, considering the maximum error, GAM demonstrates lower median REr% across all quantiles except for Q

100, giving better predictive accuracy. Notably, for quantiles Q

2, Q

5, Q

10, Q

20, and Q

50, GAM outperforms log-log model, while for Q

100, their performance is very similar.

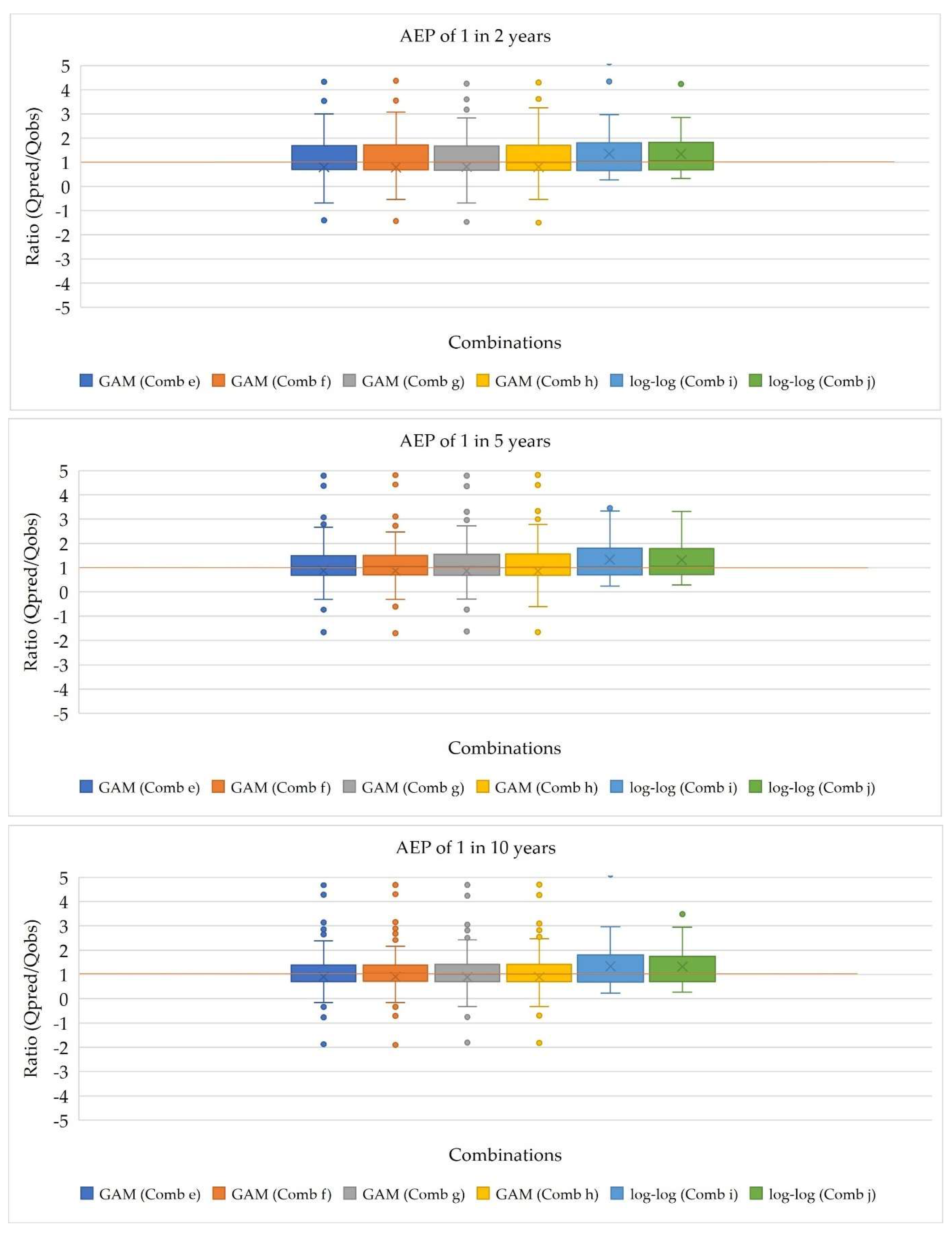

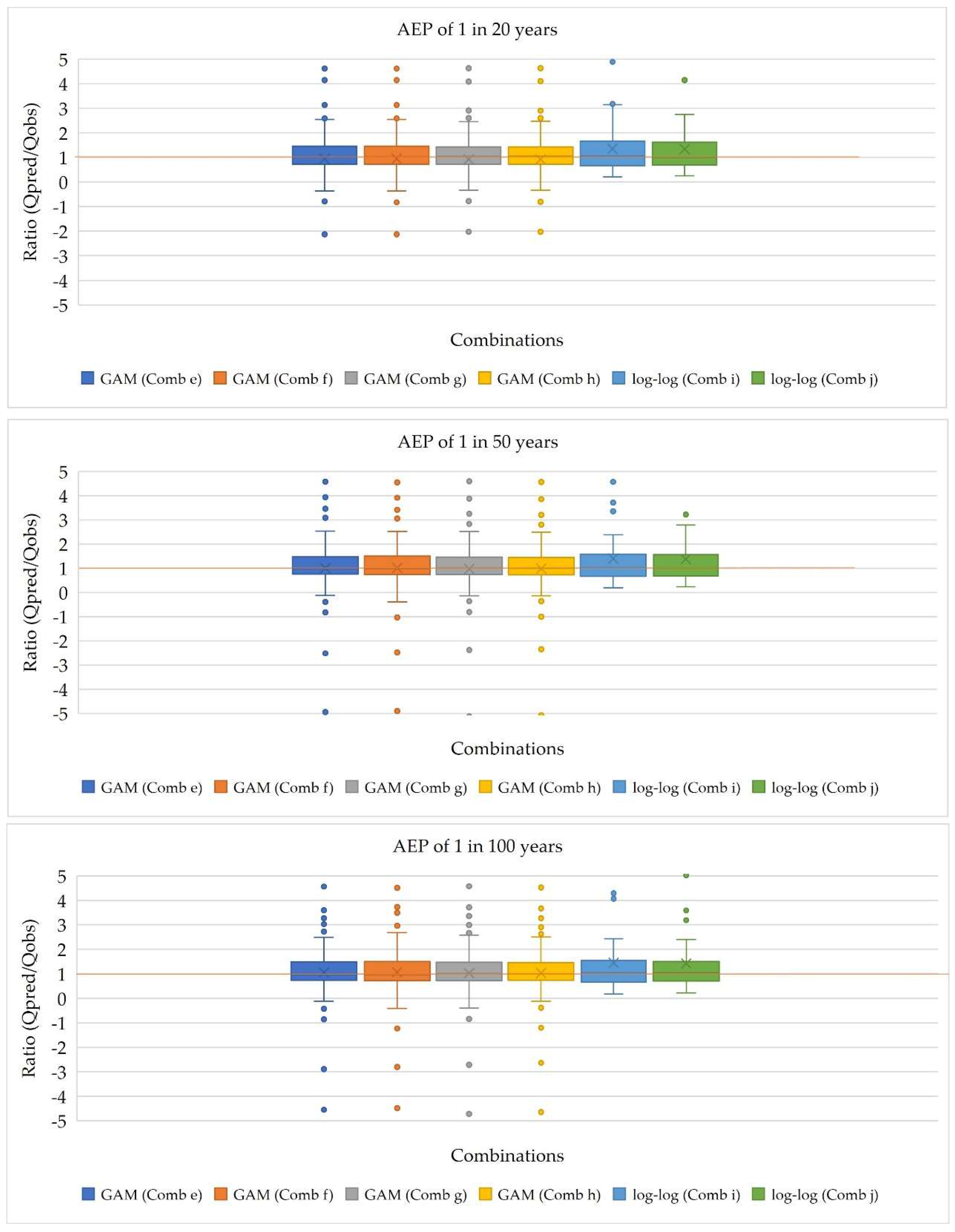

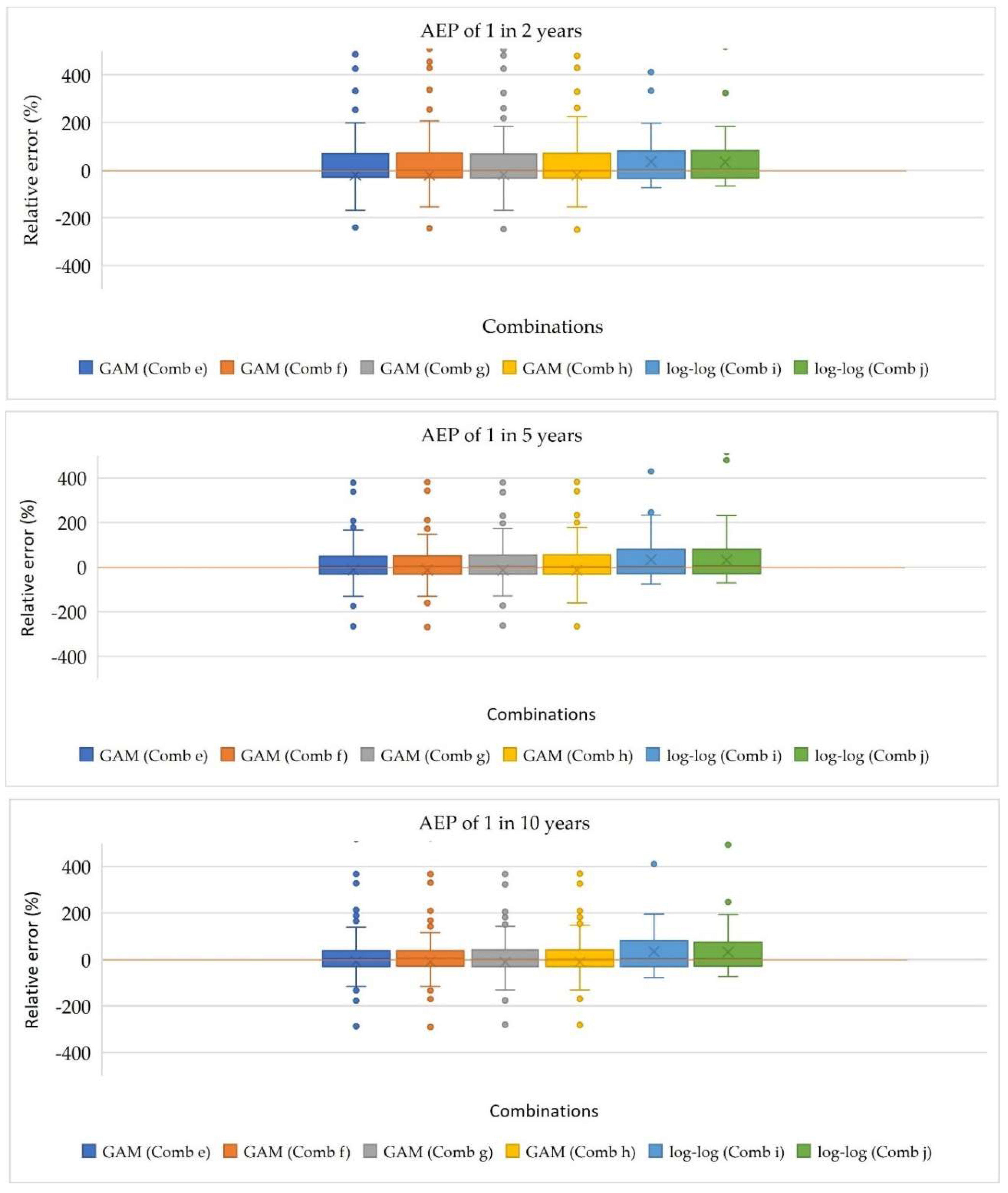

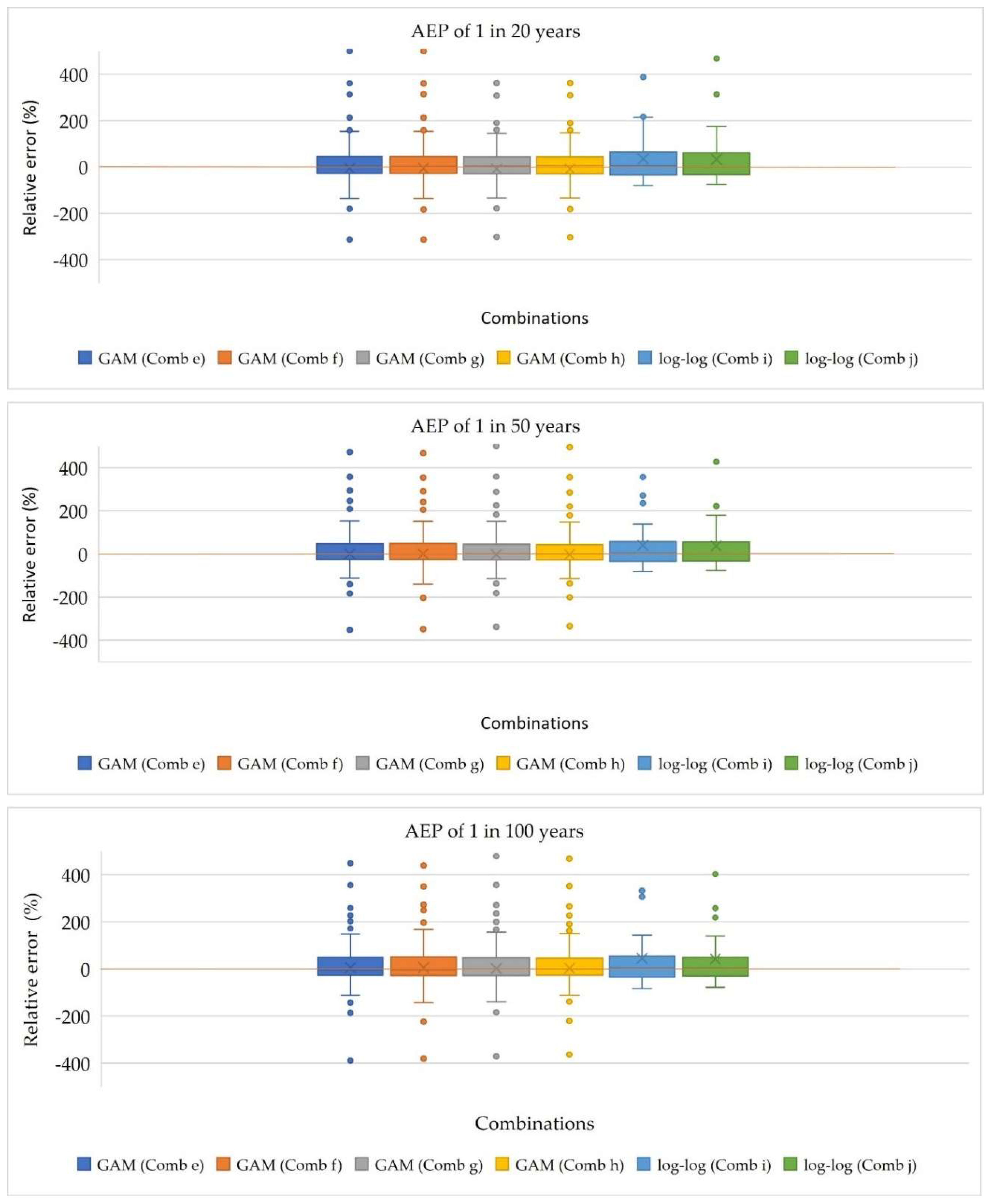

The boxplots, shown in

Figure 3 and 4, illustrates the ratio (Qpred/Qobs) for the selected combinations of models. For combinations e, f, g, and h, representing GAM models, the median values for all the AEPs closely align with the 1:1 line, indicating a strong match between predicted and observed flood quantiles. Similarly, for combinations i and j, corresponding to log-log linear models, the median values are slightly above the 1:1 line, suggesting a generally good estimation of flood quantiles compared to observed values. Consistent lower quartile values across all the combinations indicates similar performance in the lower range of the ratio values for both GAM and log-log linear models. However, the upper quartile values for GAM models are lower than those for the log-log linear models, indicating lower variability in the overestimation of flood quantiles for GAM models. Moreover, except for AEPs of 1 in 2 and 100 years, the upper whisker values for GAM models are smaller than those for log-log linear models, suggesting that while maximum overestimation may be higher for the log-log models, the variability range is wider compared to GAM models. Conversely, the lower whisker values for GAM models are larger than those for log-log linear models, indicating higher minimum overestimation for GAM models but less variability in underestimation for log-log linear models.

In conclusion, the boxplot analysis suggests that GAM models, particularly combinations e, f, g, and h, exhibit slightly better performance in estimating flood quantiles compared to the log-log linear models (combinations i and j). The close alignment of median ratio values with the 1:1 line, coupled with lower variability in overestimation, highlights the effectiveness of GAM models in accurately predicting flood magnitudes across different quantiles.

The boxplots, presented in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, reveal the distribution of the relative error % across the different combinations of models. For combinations e, f, g, and h, which represent GAM models, the median lines for all AEPs closely track with the 1:1 line, indicating a consistent pattern in error distribution. Similarly, for combinations i and j, corresponding to log-log linear models, the median lines for the relative error % values are near the 1:1 line, suggesting overall accuracy in error estimation. Consistent lower quartile values across all the combinations indicate similar performance in the lower range of relative error % values for both GAM and log-log linear models. However, the upper quartile values for GAM models are lower than those for log-log linear models, indicating less variability in the overestimation of errors for GAM models. Additionally, except for AEPs of 1 in 2 and 100 years, the upper whisker values for GAM models are smaller than those for log-log linear models, suggesting a thinner range of maximum overestimation for GAM models. Conversely, the lower whisker values for GAM models are larger than those for log-log linear models, indicating higher minimum overestimation for GAM models but less variability in underestimation for log-log linear models. Overall, the analysis of relative error % suggests that GAM models exhibit consistent error patterns across different AEPs, with less variability in overestimation compared to the log-log linear models.

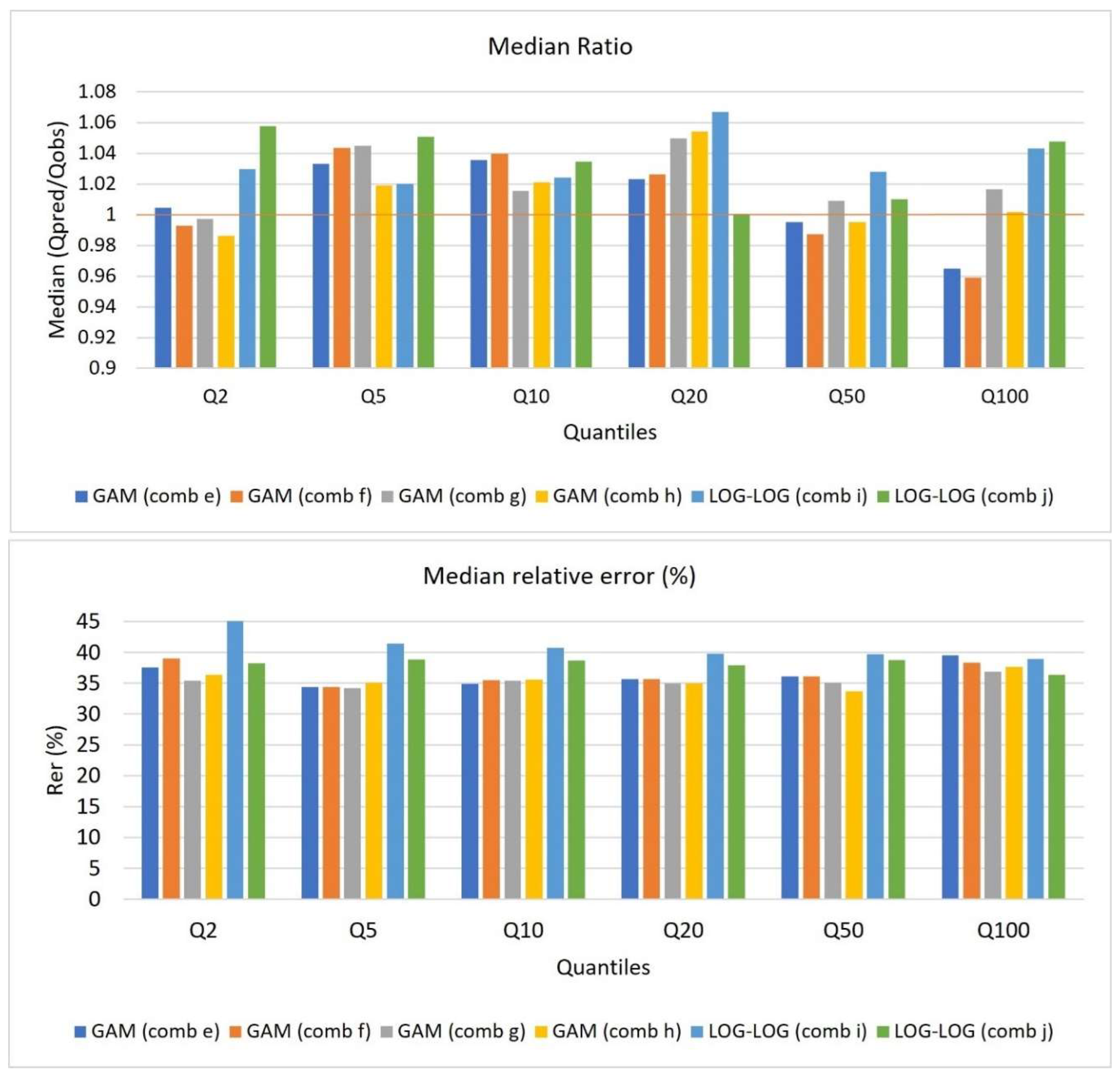

Figure 7 illustrates the comparison between median ratio and median REr% for both GAM and log-log linear models. For the GAM models (e, f, g, h) the median ratio values are generally close to 1 across all the quantiles, except for Q

100, indicating a good balance between observed and predicted values. In contrast, the log-log linear models (i, j) show median ratio values slightly above or below 1, suggesting some deviation between observed and predicted values. Therefore, GAM models provide more accurate and precise predictions compared to the log-log linear models, as indicated by the closer alignment of median ratio values to 1. Moreover, the GAM models demonstrate a better ability to capture the variability in flood magnitudes, as evidenced by their lower median REr% values across most quantiles. Conversely, the log-log linear models generally generate higher median REr% values, indicating relatively larger errors in prediction.

Overall, the findings suggest that the GAM models provide more reliable and accurate predictions of flood quantiles compared to the log-log linear models. The closer alignment of median ratio values to 1 for GAM models underscores their superior performance in capturing observed values across the different quantiles, highlighting their potential for enhancing flood prediction accuracy.

Table 17 presents the rBIAS and rRMSE percentages for different quantiles of the GAM (e, f, g, h) and log-log linear (i, j) models. For rBIAS (%), negative values indicate a tendency for underestimation, while positive values indicate overestimation. Among the GAM models (e, f, g, h), rBIAS values are consistently negative across all the quantiles, indicating a tendency for underestimation. Conversely, rBIAS values for the log-log linear models (i, j) are consistently positive, indicating a tendency for overestimation. Overall, the GAM models exhibit lowest bias values compared to the log-log linear models.

Regarding rRMSE (%), lower values indicate better model performance. Across all the quantiles, rRMSE values for the GAM models are generally lower compared to the log-log linear models. rRMSE values range from 56% to 63% for GAM and from 57% to 65% for log-log. This suggests that the GAM models have lower relative root mean square errors, indicating better performance in terms of accuracy and precision

Our results indicate that the GAM models (e, f, g, h) outperform the log-log linear models (i, j) in terms of bias and rRMSE across various quantiles, suggesting better accuracy and precision in predicting flood quantiles. Overall, based on the comparison of median ratio and median REr%, the GAM models (e, f, g, h) appear to outperform the log-log linear models (i, j) in terms of accuracy and precision in predicting flood quantiles.