Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

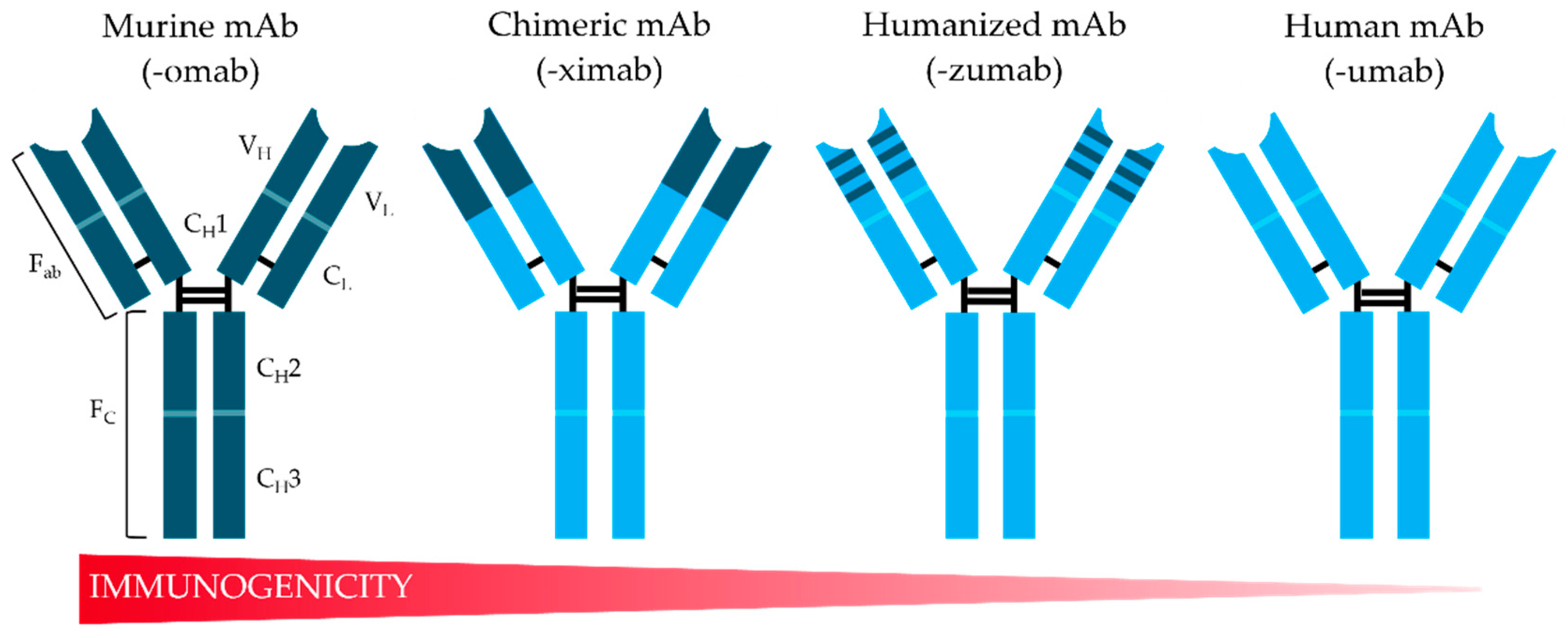

1. Historical Overview: Evolution of Recombinant mAbs

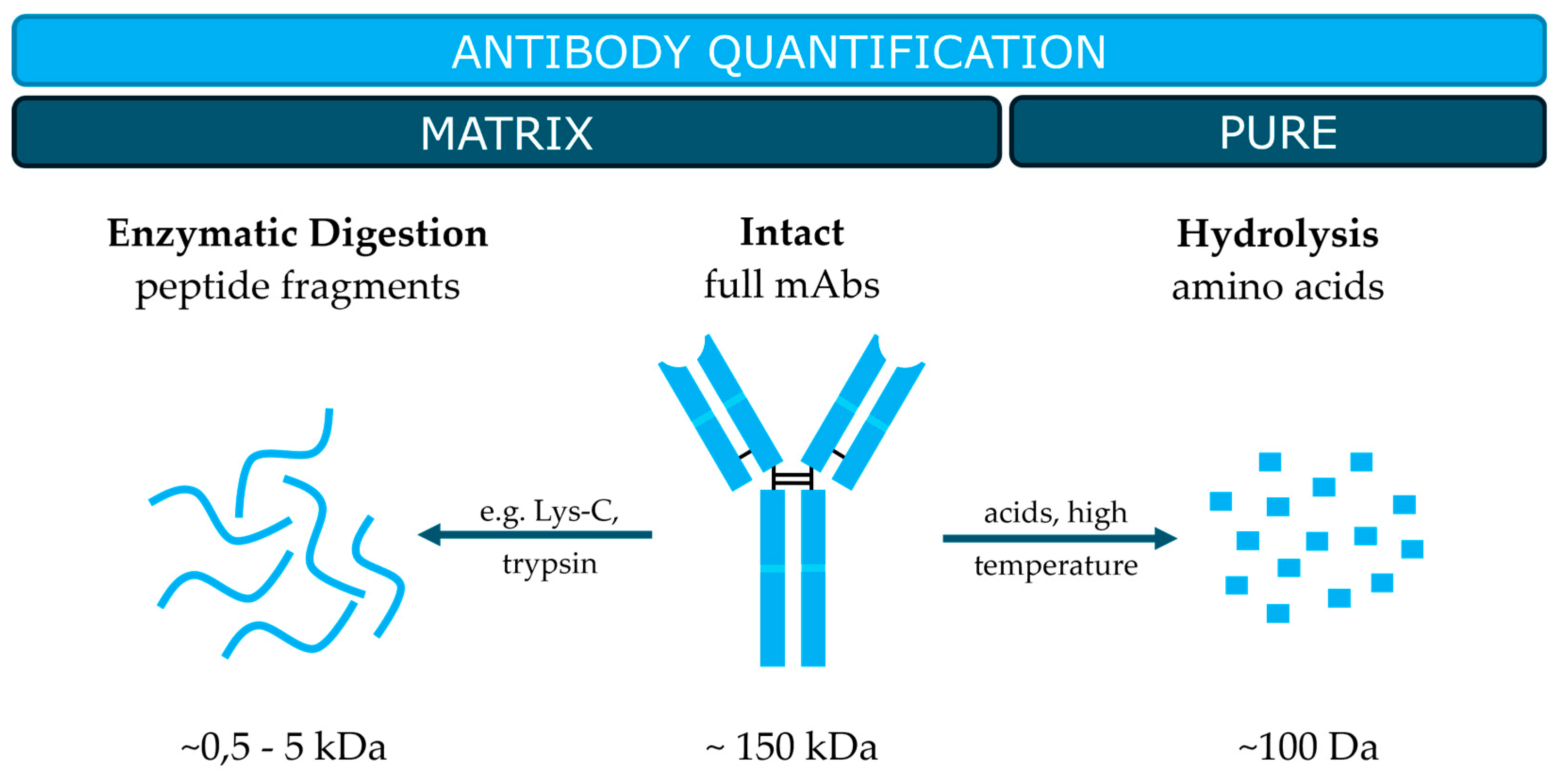

2. Current Strategies in MS-Based Quantification of Antibodies

2.1. Quantification of Enzymatically Digested Antibodies

2.2.1. Purification and Enrichment

2.2.2. Denaturation, Reduction, and Alkylation

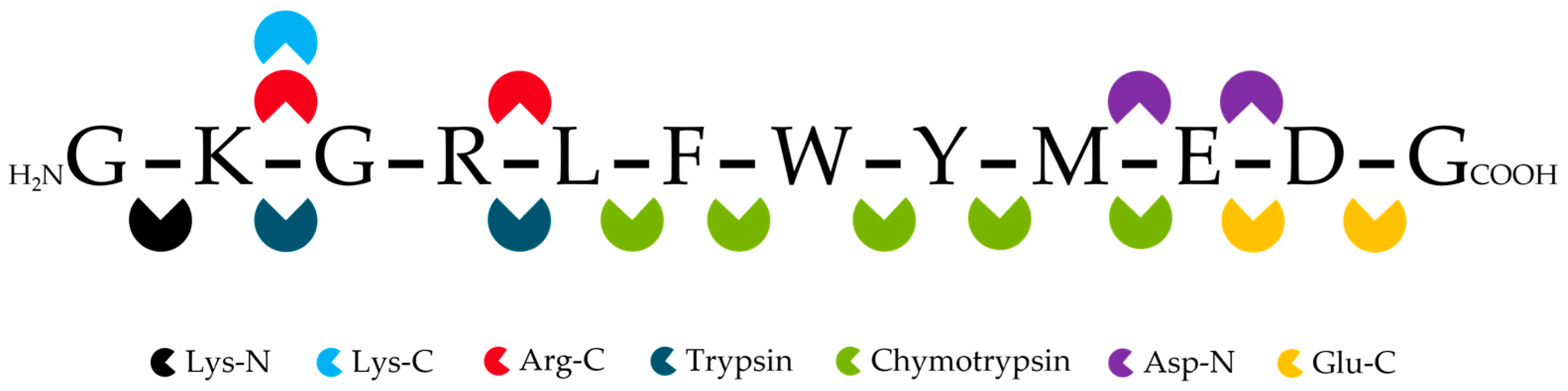

2.2.3. Digestion

| Product | Special Feature |

Denaturation | Reduction | Alkylation | Digestion conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin | |||||

|

Promega Trypsin Gold |

maximum specificity |

8 M Urea 1 hour |

DTT |

IAM 30 min |

Overnight 37°C |

| Rapid Digestion Trypsin | fast digestion | - | opt. | opt. | 1 h 70°C |

| Trypsin Platinum | recombinant enzyme, autoproteolytic resistance |

8 M GuHCl 30 min |

TCEP | IAM 30 min |

Overnight 37°C |

|

Thermo Fisher Pierce™ Trypsin |

|

1 hour at 60°C or 10 min at 95°C |

DTT |

IAA, 30 min |

4 to 24 h 37°C |

| SMART Digest Trypsin-Kit | automatable process | - | opt. | opt. | 45 min (IgG) 70°C |

| In-Solution Tryptic Digestion and Guanidination Kit | Improved ionization by guanidination of K into homo-R |

95°C 5 min |

DTT | IAM, 30 min |

2 hours at 37°C or overnight at 30°C |

|

Waters ProteinWorks eXpress Digest Kit |

High throughput of samples possible |

Digestion buffer, 80°C, 10 min |

Reduction Agent 60°C, 20 min |

Alkylation Agent 30 min |

2 h 45°C |

|

Promise Proteomics mAbXmise Kit |

Immunocapture cartridges |

opt., 4 M to 0.1 M Urea |

- |

- |

30 min to 15 h 37°C |

| Trypsin/ Lys-C Mix | |||||

|

Thermo Fisher EasyPep™ Mini MS Sample Prep Kit |

High throughput of samples possible |

Lysis Solution 95°C, 10 min |

Red. Solution |

Alk. Solution |

1 to 3 h 37°C |

| Pierce™ Trypsin/ Lys-C Protease Mix | 8 M Urea, 1 hour at 60°C or 10 min at 95°C |

DTT | IAM, 30 min |

2 to 16 hours 37°C |

|

|

Promega Rapid Digestion– Trypsin/LysC |

Fast digestion |

- |

opt. |

opt. |

1 hour 70°C |

| Trypsin/Lys-C | Quantification | 6-8 M Urea, 30 min |

DTT | IAM, 30 min |

overnight 37°C |

2.2.4. Signature Peptide Selection

2.2. Quantification of Intact Antibodies

2.3. Quantification of Hydrolysed Antibodies

3. Selection of Internal Standards for Quantification with LC-MS/MS

3.1. Intact Antibody Standards

3.2. Peptide Standards

3.3. Amino Acid Standards

4. Software Tools Supporting Targeted mAb Quantification

4.1. Commercial and Device-Specific Software

4.2. Open-Source Software Alternatives

5. Outlook: Need for Standardized Protocols, Certified Reference Materials, and New Technologies

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Köhler, G.; Milstein, C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature 1975, 256, 495-497. [CrossRef]

- Todd, P.A.; Brogden, R.N. Muromonab CD3. A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic potential. Drugs 1989, 37, 871-899. [CrossRef]

- Schroff, R.W.; Foon, K.A.; Beatty, S.M.; Oldham, R.K.; Morgan Jr, A.C. Human anti-murine immunoglobulin responses in patients receiving monoclonal antibody therapy. Cancer research 1985, 45, 879-885.

- Jaffers, G.J.; Fuller, T.; Cosimi, A.; Russell, P.; Winn, H.; Colvin, R. Monoclonal antibody therapy. Anti-idiotypic and non-anti-idiotypic antibodies to OKT3 arising despite intense immunosuppression. Transplantation 1986, 41, 572-578. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, S.L.; Johnson, M.J.; Herzenberg, L.A.; Oi, V.T. Chimeric human antibody molecules: mouse antigen-binding domains with human constant region domains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1984, 81, 6851-6855. [CrossRef]

- Brüggemann, M.; Winter, G.; Waldmann, H.; Neuberger, M.S. The immunogenicity of chimeric antibodies. Journal of Experimental Medicine 1989, 170, 2153-2157. [CrossRef]

- Faulds, D.; Sorkin, E.M. Abciximab (c7E3 Fab). A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic potential in ischaemic heart disease. Drugs 1994, 48, 583-598. [CrossRef]

- Leget, G.A.; Czuczman, M.S. Use of rituximab, the new FDA-approved antibody. Current opinion in oncology 1998, 10, 548-551. [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.T.; Dear, P.H.; Foote, J.; Neuberger, M.S.; Winter, G. Replacing the complementarity-determining regions in a human antibody with those from a mouse. Nature 1986, 321, 522-525. [CrossRef]

- Queen, C.; Schneider, W.P.; Selick, H.E.; Payne, P.W.; Landolfi, N.F.; Duncan, J.F.; Avdalovic, N.M.; Levitt, M.; Junghans, R.P.; Waldmann, T.A. A humanized antibody that binds to the interleukin 2 receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1989, 86, 10029-10033. [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, L.R.; Faulds, D. Daclizumab: a review of its use in the prevention of acute rejection in renal transplant recipients. Drugs 1999, 58, 1029-1042. [CrossRef]

- Safdari, Y.; Farajnia, S.; Asgharzadeh, M.; Khalili, M. Antibody humanization methods – a review and update. Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering Reviews 2013, 29, 175-186. [CrossRef]

- McCafferty, J.; Griffiths, A.D.; Winter, G.; Chiswell, D.J. Phage antibodies: filamentous phage displaying antibody variable domains. Nature 1990, 348, 552-554. [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.P. Filamentous fusion phage: novel expression vectors that display cloned antigens on the virion surface. Science 1985, 228, 1315-1317. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Evolution of phage display libraries for therapeutic antibody discovery. In Proceedings of the MAbs, 2023; p. 2213793.

- Frenzel, A.; Schirrmann, T.; Hust, M. Phage display-derived human antibodies in clinical development and therapy. In Proceedings of the MAbs, 2016; pp. 1177-1194.

- Sánchez-Robles, E.M.; Girón, R.; Paniagua, N.; Rodríguez-Rivera, C.; Pascual, D.; Goicoechea, C. Monoclonal Antibodies for Chronic Pain Treatment: Present and Future. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 10325. [CrossRef]

- Lonberg, N.; Taylor, L.D.; Harding, F.A.; Trounstine, M.; Higgins, K.M.; Schramm, S.R.; Kuo, C.-C.; Mashayekh, R.; Wymore, K.; McCabe, J.G.; et al. Antigen-specific human antibodies from mice comprising four distinct genetic modifications. Nature 1994, 368, 856-859. [CrossRef]

- Jakobovits, A.; Amado, R.G.; Yang, X.; Roskos, L.; Schwab, G. From XenoMouse technology to panitumumab, the first fully human antibody product from transgenic mice. Nature Biotechnology 2007, 25, 1134-1143. [CrossRef]

- Lapadula, G.; Marchesoni, A.; Armuzzi, A.; Blandizzi, C.; Caporali, R.; Chimenti, S.; Cimaz, R.; Cimino, L.; Gionchetti, P.; Girolomoni, G.; et al. Adalimumab in the Treatment of Immune-Mediated Diseases. International Journal of Immunopathology and Pharmacology 2014, 27, 33-48. [CrossRef]

- Verdin, P. Top companies and drugs by sales in 2023. Nature reviews. Drug Discovery 2024. [CrossRef]

- Barbee, M.S.; Ogunniyi, A.; Horvat, T.Z.; Dang, T.-O. Current Status and Future Directions of the Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Ipilimumab, Pembrolizumab, and Nivolumab in Oncology. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 2015, 49, 907-937. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Tang, Y.; Yang, M.; Deng, G.; Liu, H. A review of the clinical efficacy of FDA-approved antibody‒drug conjugates in human cancers. Molecular Cancer 2024, 23, 62. [CrossRef]

- Panowski, S.; Bhakta, S.; Raab, H.; Polakis, P.; Junutula, J.R. Site-specific antibody drug conjugates for cancer therapy. mAbs 2014, 6, 34-45. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Huo, S.; Xue, C.; An, B.; Qu, J. Current LC-MS-based strategies for characterization and quantification of antibody-drug conjugates. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis 2020, 10, 209-220. [CrossRef]

- Todoroki, K.; Yamada, T.; Mizuno, H.; TOYO’OKA, T. Current mass spectrometric tools for the bioanalyses of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies and antibody-drug conjugates. Analytical Sciences 2018, 34, 397-406. [CrossRef]

- Cahuzac, H.; Devel, L. Analytical Methods for the Detection and Quantification of ADCs in Biological Matrices. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 462. [CrossRef]

- Millet, A.; Khoudour, N.; Guitton, J.; Lebert, D.; Goldwasser, F.; Blanchet, B.; Machon, C. Analysis of Pembrolizumab in Human Plasma by LC-MS/HRMS. Method Validation and Comparison with Elisa. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 621. [CrossRef]

- Hallin, E.I.; Serkland, T.T.; Bjånes, T.K.; Skrede, S. High-throughput, low-cost quantification of 11 therapeutic antibodies using caprylic acid precipitation and LC-MS/MS. Analytica Chimica Acta 2024, 342789. [CrossRef]

- de Jong, K.A.; Rosing, H.; Huitema, A.D.; Beijnen, J.H. Optimized sample pre-treatment procedure for the simultaneous UPLC-MS/MS quantification of ipilimumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab in human serum. Journal of Chromatography B 2022, 1196, 123215. [CrossRef]

- Willeman, T.; Jourdil, J.-F.; Gautier-Veyret, E.; Bonaz, B.; Stanke-Labesque, F. A multiplex liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method for the quantification of seven therapeutic monoclonal antibodies: application for adalimumab therapeutic drug monitoring in patients with Crohn’s disease. Analytica chimica acta 2019, 1067, 63-70. [CrossRef]

- Tron, C.; Lemaitre, F.; Bros, P.; Goulvestre, C.; Franck, B.; Mouton, N.; Bagnos, S.; Coriat, R.; Khoudour, N.; Lebert, D.; et al. Quantification of infliximab and adalimumab in human plasma by a liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry kit and comparison with two ELISA methods. Bioanalysis 2022. [CrossRef]

- Scheffe, N.; Schreiner, R.; Thomann, A.; Findeisen, P. Development of a mass spectrometry-based method for quantification of ustekinumab in serum specimens. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 2020, 42, 572-577. [CrossRef]

- Yamaoka, K.; Irie, K.; Hiramoto, N.; Hirabatake, M.; Ikesue, H.; Hashida, T.; Shimizu, T.; Ishikawa, T.; Muroi, N. Safety and blood levels of daratumumab after switching from intravenous to subcutaneous administration in patients with multiple myeloma. Investigational New Drugs 2023, 41, 761-767. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Huang, W.; Yu, X.; Chen, C.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, F.; Yu, J.; Diao, X. A validated LC-MS/MS method for the quantitation of daratumumab in rat serum using rapid tryptic digestion without IgG purification and reduction. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2024, 116083. [CrossRef]

- Abe, K.; Shibata, K.; Naito, T.; Karayama, M.; Hamada, E.; Maekawa, M.; Yamada, Y.; Suda, T.; Kawakami, J. Quantitative LC-MS/MS method for nivolumab in human serum using IgG purification and immobilized tryptic digestion. Analytical Methods 2020, 12, 54-62. [CrossRef]

- Millet, A.; Khoudour, N.; Bros, P.; Lebert, D.; Picard, G.; Machon, C.; Goldwasser, F.; Blanchet, B.; Guitton, J. Quantification of nivolumab in human plasma by LC-MS/HRMS and LC-MS/MS, comparison with ELISA. Talanta 2021, 224, 121889. [CrossRef]

- Heudi, O.; Barteau, S.; Zimmer, D.; Schmidt, J.; Bill, K.; Lehmann, N.; Bauer, C.; Kretz, O. Towards Absolute Quantification of Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibody in Serum by LC−MS/MS Using Isotope-Labeled Antibody Standard and Protein Cleavage Isotope Dilution Mass Spectrometry. Analytical Chemistry 2008, 80, 4200-4207. [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Su, D.; Wang, J.; Jian, W.; Zhang, D. LC–MS challenges in characterizing and quantifying monoclonal antibodies (mAb) and antibody-drug conjugates (ADC) in biological samples. Current Pharmacology Reports 2018, 4, 45-63. [CrossRef]

- Hentschel, A.; Piontek, G.; Dahlmann, R.; Findeisen, P.; Sakson, R.; Carbow, P.; Renné, T.; Reinders, Y.; Sickmann, A. Highly sensitive therapeutic drug monitoring of infliximab in serum by targeted mass spectrometry in comparison to ELISA data. Clinical Proteomics 2024, 21, 16. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Liu, L.; Maia, M.; Li, J.; Lowe, J.; Song, A.; Kaur, S. A multiplexed hybrid LC–MS/MS pharmacokinetic assay to measure two co-administered monoclonal antibodies in a clinical study. Bioanalysis 2014, 6, 1781-1794. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.-H.; Liao, H.-W.; Shao, Y.-Y.; Lu, Y.-S.; Lin, C.-H.; Tsai, I.-L.; Kuo, C.-H. Development of a general method for quantifying IgG-based therapeutic monoclonal antibodies in human plasma using protein G purification coupled with a two internal standard calibration strategy using LC-MS/MS. Analytica chimica acta 2018, 1019, 93-102. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Z.; Furlong, M.T.; Wu, S.; Sleczka, B.; Tamura, J.; Wang, H.; Suchard, S.; Suri, A.; Olah, T.; Tymiak, A. Pellet digestion: a simple and efficient sample preparation technique for LC–MS/MS quantification of large therapeutic proteins in plasma. Bioanalysis 2012, 4, 17-28. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Hayes, M.; Fang, X.; Daley, M.P.; Ettenberg, S.; Tse, F.L. LC− MS/MS Approach for Quantification of Therapeutic Proteins in Plasma Using a Protein Internal Standard and 2D-Solid-Phase Extraction Cleanup. Analytical chemistry 2007, 79, 9294-9301. [CrossRef]

- Millán-Martín, S.; Jakes, C.; Carillo, S.; Bones, J. Multi-attribute method (MAM) to assess analytical comparability of adalimumab biosimilars. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2023, 234, 115543. [CrossRef]

- El Amrani, M.; Gerencser, L.; Huitema, A.D.; Hack, C.E.; van Luin, M.; van der Elst, K.C. A generic sample preparation method for the multiplex analysis of seven therapeutic monoclonal antibodies in human plasma or serum with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A 2021, 1655, 462489. [CrossRef]

- Proc, J.L.; Kuzyk, M.A.; Hardie, D.B.; Yang, J.; Smith, D.S.; Jackson, A.M.; Parker, C.E.; Borchers, C.H. A quantitative study of the effects of chaotropic agents, surfactants, and solvents on the digestion efficiency of human plasma proteins by trypsin. Journal of proteome research 2010, 9, 5422-5437. [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zhou, J.-Y.; Yang, W.; Zhang, H. Inhibition of protein carbamylation in urea solution using ammonium-containing buffers. Analytical Biochemistry 2014, 446, 76-81. [CrossRef]

- Loo, R.R.O.; Dales, N.; Andrews, P.C. Surfactant effects on protein structure examined by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Protein Science 1994, 3, 1975-1983. [CrossRef]

- Shieh, I.F.; Lee, C.-Y.; Shiea, J. Eliminating the Interferences from TRIS Buffer and SDS in Protein Analysis by Fused-Droplet Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry. Journal of Proteome Research 2005, 4, 606-612. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, J.C.; Bomgarden, R.D. Sample preparation for mass spectrometry-based proteomics; from proteomes to peptides. In Modern Proteomics–Sample Preparation, Analysis and Practical Applications; Springer: 2016; pp. 43-62.

- Lebert, D.; Picard, G.; Beau-Larvor, C.; Troncy, L.; Lacheny, C.; Maynadier, B.; Low, W.; Mouz, N.; Brun, V.; Klinguer-Hamour, C. Absolute and multiplex quantification of antibodies in serum using PSAQ™ standards and LC-MS/MS. Bioanalysis 2015, 7, 1237-1251. [CrossRef]

- Martos, G.; Bedu, M.; Josephs, R.; Westwood, S.; Wielgosz, R. Quantification of SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal IgG mass fraction by isotope dilution mass spectrometry. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2024, 416, 2423-2437. [CrossRef]

- Suttapitugsakul, S.; Xiao, H.; Smeekens, J.; Wu, R. Evaluation and optimization of reduction and alkylation methods to maximize peptide identification with MS-based proteomics. Molecular BioSystems 2017, 13, 2574-2582. [CrossRef]

- Müller, T.; Winter, D. Systematic evaluation of protein reduction and alkylation reveals massive unspecific side effects by iodine-containing reagents. Molecular & cellular proteomics 2017, 16, 1173-1187. [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, K.G.; Levitsky, L.I.; Pyatnitskiy, M.A.; Ilina, I.Y.; Bubis, J.A.; Solovyeva, E.M.; Zgoda, V.G.; Gorshkov, M.V.; Moshkovskii, S.A. Cysteine alkylation methods in shotgun proteomics and their possible effects on methionine residues. Journal of proteomics 2021, 231, 104022. [CrossRef]

- Hains, P.G.; Robinson, P.J. The impact of commonly used alkylating agents on artifactual peptide modification. Journal of proteome research 2017, 16, 3443-3447. [CrossRef]

- Geoghegan, K.F.; Hoth, L.R.; Tan, D.H.; Borzilleri, K.A.; Withka, J.M.; Boyd, J.G. Cyclization of N-terminal S-carbamoylmethylcysteine causing loss of 17 Da from peptides and extra peaks in peptide maps. Journal of proteome research 2002, 1, 181-187. [CrossRef]

- Switzar, L.; Giera, M.; Niessen, W.M. Protein digestion: an overview of the available techniques and recent developments. Journal of proteome research 2013, 12, 1067-1077. [CrossRef]

- Falck, D.; Jansen, B.C.; Plomp, R.; Reusch, D.; Haberger, M.; Wuhrer, M. Glycoforms of immunoglobulin G based biopharmaceuticals are differentially cleaved by trypsin due to the glycoform influence on higher-order structure. Journal of proteome research 2015, 14, 4019-4028. [CrossRef]

- Heissel, S.; Frederiksen, S.J.; Bunkenborg, J.; Højrup, P. Enhanced trypsin on a budget: Stabilization, purification and high-temperature application of inexpensive commercial trypsin for proteomics applications. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0218374. [CrossRef]

- Menneteau, T.; Saveliev, S.; Butré, C.I.; Rivera, A.K.G.; Urh, M.; Delobel, A. Addressing common challenges of biotherapeutic protein peptide mapping using recombinant trypsin. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2024, 243, 116124. [CrossRef]

- Reinders, L.M.; Klassen, M.D.; Teutenberg, T.; Jaeger, M.; Schmidt, T.C. Development of a multidimensional online method for the characterization and quantification of monoclonal antibodies using immobilized flow-through enzyme reactors. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2021, 413, 7119-7128. [CrossRef]

- Glatter, T.; Ludwig, C.; Ahrné, E.; Aebersold, R.; Heck, A.J.R.; Schmidt, A. Large-Scale Quantitative Assessment of Different In-Solution Protein Digestion Protocols Reveals Superior Cleavage Efficiency of Tandem Lys-C/Trypsin Proteolysis over Trypsin Digestion. Journal of Proteome Research 2012, 11, 5145-5156. [CrossRef]

- Giansanti, P.; Tsiatsiani, L.; Low, T.Y.; Heck, A.J.R. Six alternative proteases for mass spectrometry–based proteomics beyond trypsin. Nature Protocols 2016, 11, 993-1006. [CrossRef]

- Trevisiol, S.; Ayoub, D.; Lesur, A.; Ancheva, L.; Gallien, S.; Domon, B. The use of proteases complementary to trypsin to probe isoforms and modifications. PROTEOMICS 2016, 16, 715-728. [CrossRef]

- Hao, P.; Ren, Y.; Datta, A.; Tam, J.P.; Sze, S.K. Evaluation of the effect of trypsin digestion buffers on artificial deamidation. Journal of proteome research 2015, 14, 1308-1314. [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, E.; Veth, T.S.; Riley, N.M. Revisiting the effect of trypsin digestion buffers on artificial deamidation. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zeng, J.; Titsch, C.; Voronin, K.; Akinsanya, B.; Luo, L.; Shen, H.; Desai, D.D.; Allentoff, A.; Aubry, A.-F.; et al. Fully Validated LC-MS/MS Assay for the Simultaneous Quantitation of Coadministered Therapeutic Antibodies in Cynomolgus Monkey Serum. Analytical Chemistry 2013, 85, 9859-9867. [CrossRef]

- Ren, D.; Pipes, G.D.; Liu, D.; Shih, L.-Y.; Nichols, A.C.; Treuheit, M.J.; Brems, D.N.; Bondarenko, P.V. An improved trypsin digestion method minimizes digestion-induced modifications on proteins. Analytical biochemistry 2009, 392, 12-21. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Ponniah, G.; Neill, A.; Patel, R.; Andrien, B. Accurate determination of protein methionine oxidation by stable isotope labeling and LC-MS analysis. Analytical chemistry 2013, 85, 11705-11709. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Gao, Z.; Ren, X.; Sheng, J.; Xu, P.; Chang, C.; Fu, Y. DeepDigest: Prediction of Protein Proteolytic Digestion with Deep Learning. Analytical Chemistry 2021, 93, 6094-6103. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Jiskoot, W.; Schöneich, C.; Rathore, A.S. Oxidation and deamidation of monoclonal antibody products: potential impact on stability, biological activity, and efficacy. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2022, 111, 903-918. [CrossRef]

- Millán-Martín, S.; Jakes, C.; Carillo, S.; Buchanan, T.; Guender, M.; Kristensen, D.B.; Sloth, T.M.; Ørgaard, M.; Cook, K.; Bones, J. Inter-laboratory study of an optimised peptide mapping workflow using automated trypsin digestion for monitoring monoclonal antibody product quality attributes. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2020, 412, 6833-6848. [CrossRef]

- Kuzyk, M.A.; Parker, C.E.; Domanski, D.; Borchers, C.H. Development of MRM-based assays for the absolute quantitation of plasma proteins. Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.J.) 2013, 53-82. [CrossRef]

- Liebler, D.C.; Zimmerman, L.J. Targeted quantitation of proteins by mass spectrometry. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 3797-3806. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, C.; Urlaub, H. Absolute quantification of proteins using standard peptides and multiple reaction monitoring. Quantitative Methods in Proteomics 2012, 249-265. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Brunak, S. Prediction of glycosylation across the human proteome and the correlation to protein function. In Biocomputing 2002; World Scientific: 2001; pp. 310-322.

- Pugalenthi, G.; Nithya, V.; Chou, K.-C.; Archunan, G. Nglyc: a random forest method for prediction of N-glycosylation sites in eukaryotic protein sequence. Protein and Peptide Letters 2020, 27, 178-186. [CrossRef]

- Pakhrin, S.C.; Aoki-Kinoshita, K.F.; Caragea, D.; Kc, D.B. DeepNGlyPred: a deep neural network-based approach for human N-linked glycosylation site prediction. Molecules 2021, 26, 7314. [CrossRef]

- Jian, W.; Kang, L.; Burton, L.; Weng, N. A workflow for absolute quantitation of large therapeutic proteins in biological samples at intact level using LC-HRMS. Bioanalysis 2016, 8, 1679-1691. [CrossRef]

- Lanshoeft, C.; Cianférani, S.; Heudi, O. Generic Hybrid Ligand Binding Assay Liquid Chromatography High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry-Based Workflow for Multiplexed Human Immunoglobulin G1 Quantification at the Intact Protein Level: Application to Preclinical Pharmacokinetic Studies. Analytical Chemistry 2017, 89, 2628-2635. [CrossRef]

- Cong, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Hu, L.; Gu, J. Quantitative MS analysis of therapeutic mAbs and their glycosylation for pharmacokinetics study. PROTEOMICS - Clinical Applications 2016, 10, 303-314. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, X. IgG N-glycans. Advances in Clinical Chemistry 2021, 105, 1-47. [CrossRef]

- van den Broek, I.; van Dongen, W.D. LC–MS-based quantification of intact proteins: perspective for clinical and bioanalytical applications. Bioanalysis 2015, 7, 1943-1958. [CrossRef]

- Rosati, S.; Yang, Y.; Barendregt, A.; Heck, A.J.R. Detailed mass analysis of structural heterogeneity in monoclonal antibodies using native mass spectrometry. Nature Protocols 2014, 9, 967-976. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Liu, L.; Saad, O.M.; Baudys, J.; Williams, L.; Leipold, D.; Shen, B.; Raab, H.; Junutula, J.R.; Kim, A. Characterization of intact antibody–drug conjugates from plasma/serum in vivo by affinity capture capillary liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. Analytical biochemistry 2011, 412, 56-66. [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Burton, L.; Moore, I. LC–HRMS quantitation of intact antibody drug conjugate trastuzumab emtansine from rat plasma. Bioanalysis 2018, 10, 851-862. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Gu, H.; Zheng, N.; Zeng, J. Critical considerations for immunocapture enrichment LC–MS bioanalysis of protein therapeutics and biomarkers. Bioanalysis 2018, 10, 987-995. [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Weng, N.; Jian, W. LC–MS bioanalysis of intact proteins and peptides. Biomedical Chromatography 2020, 34, e4633. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Vasicek, L.A.; Hsieh, S.; Zhang, S.; Bateman, K.P.; Henion, J. Top-down LC–MS quantitation of intact denatured and native monoclonal antibodies in biological samples. Bioanalysis 2018, 10, 1039-1054. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.E.; Lebert, D.; Guillaubez, J.-V.; Samra, S.; Goucher, E.; Hart, B. Streamlined workflow for absolute quantitation of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies using Promise Proteomics mAbXmise kits and a TSQ Altis Plus mass spectrometer. Available online: https://promise-proteomics.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/tn-001753-cl-clinical-altis-mabs-tn001753-na-en.pdf (accessed on 07.08.2024).

- Rutherfurd, S.M.; Gilani, G.S. Amino Acid Analysis. Current Protocols in Protein Science 2009, 58. [CrossRef]

- Rutherfurd, S.M.; Dunn, B.M. Quantitative Amino Acid Analysis. Current Protocols in Protein Science 2011, 63. [CrossRef]

- Josephs, R.D.; Martos, G.; Li, M.; Wu, L.; Melanson, J.E.; Quaglia, M.; Beltrão, P.J.; Prevoo-Franzsen, D.; Boeuf, A.; Delatour, V. Establishment of measurement traceability for peptide and protein quantification through rigorous purity assessment—a review. Metrologia 2019, 56, 044006. [CrossRef]

- Violi, J.P.; Bishop, D.P.; Padula, M.P.; Steele, J.R.; Rodgers, K.J. Considerations for amino acid analysis by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry: A tutorial review. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2020, 131, 116018. [CrossRef]

- Kato, M.; Kato, H.; Eyama, S.; Takatsu, A. Application of amino acid analysis using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography coupled with isotope dilution mass spectrometry for peptide and protein quantification. Journal of Chromatography B 2009, 877, 3059-3064. [CrossRef]

- Stocks, B.B.; Thibeault, M.-P.; Schrag, J.D.; Melanson, J.E. Characterization of a SARS-CoV-2 spike protein reference material. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2022, 414, 3561-3569. [CrossRef]

- Stocks, B.B.; Thibeault, M.-P.; L’Abbé, D.; Stuible, M.; Durocher, Y.; Melanson, J.E. Production and Characterization of a SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein Reference Material. ACS Measurement Science Au 2022, 2, 620-628. [CrossRef]

- Louwagie, M.; Kieffer-Jaquinod, S.; Dupierris, V.; Couté, Y.; Bruley, C.; Garin, J.; Dupuis, A.; Jaquinod, M.; Brun, V. Introducing AAA-MS, a Rapid and Sensitive Method for Amino Acid Analysis Using Isotope Dilution and High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Journal of Proteome Research 2012, 11, 3929-3936. [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.-S.; Lim, H.-M.; Kim, S.-K.; Ku, H.-K.; Oh, K.-H.; Park, S.-R. Quantification of human growth hormone by amino acid composition analysis using isotope dilution liquid-chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography a 2011, 1218, 6596-6602. [CrossRef]

- Mi, W.; Josephs, R.; Melanson, J.; Dai, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, R.; Chu, Z.; Fang, X.; Thibeault, M.; Stocks, B. PAWG Pilot Study on Quantification of SARS-CoV-2 Monoclonal Antibody-Part 1. Metrologia 2022, 59, 08001. [CrossRef]

- Stocks, B.B.; Thibeault, M.-P.; L’Abbé, D.; Umer, M.; Liu, Y.; Stuible, M.; Durocher, Y.; Melanson, J.E. Characterization of biotinylated human ACE2 and SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA. 4/5 spike protein reference materials. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2024, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Catalogue: SIL-mAbs for targeted LC-MS quantification. Available online: https://promise-proteomics.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Catalogue-SIL-mAbs-2024.pdf (accessed on 07.08.2024).

- Picard, G.; Lebert, D.; Louwagie, M.; Adrait, A.; Huillet, C.; Vandenesch, F.; Bruley, C.; Garin, J.; Jaquinod, M.; Brun, V. PSAQ™ standards for accurate MS-based quantification of proteins: from the concept to biomedical applications. Journal of Mass Spectrometry 2012, 47, 1353-1363. [CrossRef]

- Ong, S.-E.; Blagoev, B.; Kratchmarova, I.; Kristensen, D.B.; Steen, H.; Pandey, A.; Mann, M. Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino Acids in Cell Culture, SILAC, as a Simple and Accurate Approach to Expression Proteomics. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2002, 1, 376-386. [CrossRef]

- Osaki, F.; Tabata, K.; Oe, T. Quantitative LC/ESI-SRM/MS of antibody biopharmaceuticals: use of a homologous antibody as an internal standard and three-step method development. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2017, 409, 5523-5532. [CrossRef]

- Smit, N.P.M.; Ruhaak, L.R.; Romijn, F.P.H.T.M.; Pieterse, M.M.; Van Der Burgt, Y.E.M.; Cobbaert, C.M. The Time Has Come for Quantitative Protein Mass Spectrometry Tests That Target Unmet Clinical Needs. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 2021, 32, 636-647. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Lee, J. Peptide purity assignment for antibody quantification by combining isotope dilution mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography. Bulletin of the Korean Chemical Society 2022, 43, 704-713. [CrossRef]

- Burkitt, W.I.; Pritchard, C.; Arsene, C.; Henrion, A.; Bunk, D.; O’Connor, G. Toward Systeme International d’Unite-traceable protein quantification: from amino acids to proteins. Analytical biochemistry 2008, 376, 242-251. [CrossRef]

- Benesova, E.; Vidova, V.; Spacil, Z. A comparative study of synthetic winged peptides for absolute protein quantification. Scientific Reports 2021, 11. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ortiz, R.; Tran, L.; Hall, M.; Spahr, C.; Walker, K.; Laudemann, J.; Miller, S.; Salimi-Moosavi, H.; Lee, J.W. General LC-MS/MS Method Approach to Quantify Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibodies Using a Common Whole Antibody Internal Standard with Application to Preclinical Studies. Analytical Chemistry 2012, 84, 1267-1273. [CrossRef]

- Bronsema, K.J.; Bischoff, R.; van de Merbel, N.C. Internal standards in the quantitative determination of protein biopharmaceuticals using liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography B 2012, 893, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Furlong, M.T.; Ouyang, Z.; Wu, S.; Tamura, J.; Olah, T.; Tymiak, A.; Jemal, M. A universal surrogate peptide to enable LC-MS/MS bioanalysis of a diversity of human monoclonal antibody and human Fc-fusion protein drug candidates in pre-clinical animal studies. Biomedical Chromatography 2012, 26, 1024-1032. [CrossRef]

- Furlong, M.T. Generic Peptide Strategies for LC–MS/MS Bioanalysis of Human Monoclonal Antibody Drugs and Drug Candidates. Protein Analysis using Mass Spectrometry: Accelerating Protein Biotherapeutics from Lab to Patient 2017, 161-181. [CrossRef]

- Administration, F.a.D. Bioanalytical Method Validation Guidance for Industry. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/bioanalytical-method-validation-guidance-industry (accessed on 07.08.2024).

- Agency, E.M. ICH guideline M10 on bioanalytical method validation and study sample analysis. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/ich-guideline-m10-bioanalytical-method-validation-step-5_en.pdf (accessed on 07.08.2024).

- Vidova, V.; Spacil, Z. A review on mass spectrometry-based quantitative proteomics: Targeted and data independent acquisition. Analytica chimica acta 2017, 964, 7-23. [CrossRef]

- Ranbaduge, N.; Yu, Y.Q. A Streamlined Compliant Ready Workflow for Peptide-Based Multi-Attribute Method (MAM). Available online: https://www.waters.com/content/dam/waters/en/app-notes/2020/720007094/720007094-zh_tw.pdf (accessed on.

- Yun W. Alelyunas, H.S., Mark D. Wrona, Weibin Chen Rapid, Sensitive, and Routine Intact mAb Quantification using a Compact Tof HRMS Platform. Available online: https://lcms.cz/labrulez-bucket-strapi-h3hsga3/2019asms_alelyunas_intactproteinquan_659b6f83aa/2019asms_alelyunas_intactproteinquan.pdf (accessed on 07.08.2024).

- Millán-Martín, S.; Jakes, C.; Carillo, S.; Bones, J. Multi-Attribute Method (MAM) Analytical Workflow for Biotherapeutic Protein Characterization from Process Development to QC. Current Protocols 2023, 3, e927. [CrossRef]

- Schneck, N.A.; Mehl, J.T.; Kellie, J.F. Protein LC-MS Tools for the Next Generation of Biotherapeutic Analyses from Preclinical and Clinical Serum. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 2023, 34, 1837-1846. [CrossRef]

- Kiyonami, R.; Schoen, A.; Prakash, A.; Nguyen, H.; Peterman, S.; Selevsek, N.; Zabrouskov, V.; Huhmer, A.; Domon, B. Rapid assay development and refinement for targeted protein quantitation using an intelligent SRM (iSRM) workflow. Available online: https://tools.thermofisher.com/content/sfs/brochures/AN468_63139_Vantage_Prot(1).pdf (accessed on 07.08.2024).

- Kiyonami, R.; Zeller, M.; Zabrouskov, V. Quantifying peptides in complex mixtures with high sensitivity and precision using a targeted approach with a hybrid linear ion trap-orbitrap mass spectrometer. Available online: https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/CMD/Application-Notes/AN-557-LC-MS-Peptides-Complex-Mixtures-AN63499-EN.pdf (accessed on 07.08.2024).

- Colangelo, C.M.; Chung, L.; Bruce, C.; Cheung, K.-H. Review of software tools for design and analysis of large scale MRM proteomic datasets. Methods 2013, 61, 287-298. [CrossRef]

- Desiere, F.; Deutsch, E.W.; King, N.L.; Nesvizhskii, A.I.; Mallick, P.; Eng, J.; Chen, S.; Eddes, J.; Loevenich, S.N.; Aebersold, R. The peptideatlas project. Nucleic acids research 2006, 34, D655-D658. [CrossRef]

- MacLean, B.; Tomazela, D.M.; Shulman, N.; Chambers, M.; Finney, G.L.; Frewen, B.; Kern, R.; Tabb, D.L.; Liebler, D.C.; MacCoss, M.J. Skyline: an open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 966-968. [CrossRef]

- Gessulat, S.; Schmidt, T.; Zolg, D.P.; Samaras, P.; Schnatbaum, K.; Zerweck, J.; Knaute, T.; Rechenberger, J.; Delanghe, B.; Huhmer, A. Prosit: proteome-wide prediction of peptide tandem mass spectra by deep learning. Nature methods 2019, 16, 509-518.

- Cox, J.; Mann, M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized ppb-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nature biotechnology 2008, 26, 1367-1372. [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.; Matic, I.; Hilger, M.; Nagaraj, N.; Selbach, M.; Olsen, J.V.; Mann, M. A practical guide to the MaxQuant computational platform for SILAC-based quantitative proteomics. Nature protocols 2009, 4, 698-705. [CrossRef]

- Tyanova, S.; Temu, T.; Cox, J. The MaxQuant computational platform for mass spectrometry-based shotgun proteomics. Nature protocols 2016, 11, 2301-2319.

- Röst, H.L.; Sachsenberg, T.; Aiche, S.; Bielow, C.; Weisser, H.; Aicheler, F.; Andreotti, S.; Ehrlich, H.-C.; Gutenbrunner, P.; Kenar, E. OpenMS: a flexible open-source software platform for mass spectrometry data analysis. Nature methods 2016, 13, 741-748. [CrossRef]

- Pfeuffer, J.; Bielow, C.; Wein, S.; Jeong, K.; Netz, E.; Walter, A.; Alka, O.; Nilse, L.; Colaianni, P.D.; McCloskey, D. OpenMS 3 enables reproducible analysis of large-scale mass spectrometry data. Nature methods 2024, 21, 365-367. [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, H.; Kanazawa, M.; Ogiwara, A.; Arita, M. MRMPROBS suite for metabolomics using large-scale MRM assays. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2379-2380. [CrossRef]

- Valot, B.; Langella, O.; Nano, E.; Zivy, M. MassChroQ: a versatile tool for mass spectrometry quantification. Proteomics 2011, 11, 3572-3577. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Weng, K.; Guo, Y.; Peng, J.; Zhu, Z.-J. An integrated targeted metabolomic platform for high-throughput metabolite profiling and automated data processing. Metabolomics 2015, 11, 1575-1586. [CrossRef]

- Team, R.C. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 07.08.2024).

- Choi, M.; Carver, J.; Chiva, C.; Tzouros, M.; Huang, T.; Tsai, T.-H.; Pullman, B.; Bernhardt, O.M.; Hüttenhain, R.; Teo, G.C. MassIVE. quant: a community resource of quantitative mass spectrometry–based proteomics datasets. Nature methods 2020, 17, 981-984. [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Pfeuffer, J.; Wang, H.; Zheng, P.; Käll, L.; Sachsenberg, T.; Demichev, V.; Bai, M.; Kohlbacher, O.; Perez-Riverol, Y. quantms: a cloud-based pipeline for quantitative proteomics enables the reanalysis of public proteomics data. Nature Methods 2024, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Jiang, H.; Lu, M.; Tong, J.; An, S.; Wang, J.; Yu, C. MRMPro: a web-based tool to improve the speed of manual calibration for multiple reaction monitoring data analysis by mass spectrometry. BMC bioinformatics 2024, 25, 60. [CrossRef]

- Mi, W.; Josephs, R.; Melanson, J.; Dai, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, R.; Chu, Z.; Fang, X.; Thibeault, M.; Stocks, B. PAWG pilot study on quantification of SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibody-part 2. Metrologia 2023, 60, 08016. [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.G.; Greenberg, N.; Panteghini, M.; Budd, J.R.; Johansen, J.V. Guidance on which calibrators in a metrologically traceable calibration hierarchy must be commutable with clinical samples. Clinical Chemistry 2023, 69, 228-238. [CrossRef]

- Diederiks, N.M.; van der Burgt, Y.E.; Ruhaak, L.R.; Cobbaert, C.M. Developing an SI-traceable Lp (a) reference measurement system: a pilgrimage to selective and accurate apo (a) quantification. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences 2023, 60, 483-501. [CrossRef]

- Ruhaak, L.R.; Romijn, F.P.; Begcevic Brkovic, I.; Kuklenyik, Z.; Dittrich, J.; Ceglarek, U.; Hoofnagle, A.N.; Althaus, H.; Angles-Cano, E.; Coassin, S. Development of an LC-MRM-MS-based candidate reference measurement procedure for standardization of serum apolipoprotein (a) tests. Clinical Chemistry 2023, 69, 251-261. [CrossRef]

- Schiel, J.E.; Mire-Sluis, A.; Davis, D. Monoclonal antibody therapeutics: the need for biopharmaceutical reference materials. In State-of-the-Art and Emerging Technologies for Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibody Characterization Volume 1. Monoclonal Antibody Therapeutics: Structure, Function, and Regulatory Space; ACS Publications: 2014; pp. 1-34.

- Schiel, J.E.; Turner, A. The NISTmAb Reference Material 8671 lifecycle management and quality plan. Analytical and bioanalytical chemistry 2018, 410, 2067-2078. [CrossRef]

- Kinumi, T.; Saikusa, K.; Kato, M.; Kojima, R.; Igarashi, C.; Noda, N.; Honda, S. Characterization and Value Assignment of a Monoclonal Antibody Reference Material, NMIJ RM 6208a, AIST-MAB. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2022, 9, 842041. [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, B.; Swart, C.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Y.; Huggett, J.; Wielgosz, R.; Niu, C.; Li, Q. Reliable biological and multi-omics research through biometrology. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 2024, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Shuford, C.M.; Walters, J.J.; Holland, P.M.; Sreenivasan, U.; Askari, N.; Ray, K.; Grant, R.P. Absolute protein quantification by mass spectrometry: not as simple as advertised. Analytical chemistry 2017, 89, 7406-7415. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Chen, H.; Zare, R.N. Ultrafast enzymatic digestion of proteins by microdroplet mass spectrometry. Nature communications 2020, 11, 1049. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; Li, Z.; Xing, X.; He, F.; Huang, J.; Xue, D. Improving the activity and thermal stability of trypsin by the rational design. Process Biochemistry 2023, 130, 227-235. [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Liu, Y.; Yu, H.; Du, K.; Gan, Y.; Huang, H. A novel strategy for thermostability improvement of trypsin based on N-glycosylation within the Ω-loop region. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology 2016, 26, 1163-1172. [CrossRef]

- Narumi, R.; Masuda, K.; Tomonaga, T.; Adachi, J.; Ueda, H.R.; Shimizu, Y. Cell-free synthesis of stable isotope-labeled internal standards for targeted quantitative proteomics. Synthetic and Systems Biotechnology 2018, 3, 97-104. [CrossRef]

| Generic name | Antibody subclass | Year of approval |

Target | Sales1 (Billion USD) |

Signature peptides2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pembrolizumab | IgG4κ | 2021 | Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) | 25.0 | ASGYTFTNYYMYWVR [28] DLPLTFGGGTK [28,29] VTLTTDSSTTTAYMELK [30] |

| Adalimumab | IgG1κ | 2002 | Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) |

14.4 | APYTFGQGTK [31,32] |

| Ustekinumab | IgG1κ | 2009 | Interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23 | 10.9 | PGQGYFDFWGQGTLVTVSSSSTK [33] GLDWIGIMSPVDSDIR [29,33] |

| Daratumumab | IgG1κ | 2016 | Hydrolase CD38 | 9.7 | SNWPPTFGQGTK [34] LLIYDASNR [35] |

| Nivolumab | IgG4κ | 2014 | PD-1 | 9.0 | ASGITFSNSGMHWVR [29,30,36,37] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).