1. Introduction

Skeletal muscle comprises approximately 50% of total body mass and is essential for various physiological processes, including locomotion, respiration, metabolism, and energy storage [

1]. The process of muscle tissue development and regeneration, referred to as myogenesis, play vital roles in muscle mass maintenance, especially in response to injury or disease [

2,

3]. Myogenesis involves a sequence of cellular events that begin with myoblast proliferation, followed by myoblast differentiation into myocytes, and culminating in the fusion of myocytes into multinucleated myotubes, which ultimately form functional muscle fibers [

4,

5]. This process is precisely regulated by a complex network of signaling pathways, with cytoskeletal dynamics particularly critical for myoblast differentiation, fusion, and maturation [

6,

7]. Recent research has highlighted that mechanotransduction is a pivotal regulatory mechanism in skeletal myogenesis, which involves the translation of mechanical cues into biochemical signals for the myogenic transcription program [

8,

9]. Accordingly, dysregulation in cytoskeletal remodeling has been directly associated with defects in myoblast differentiation, thereby impeding the formation of myotubes from progenitor cells [

10,

11,

12,

13].

The actin cytoskeleton is especially dynamic and undergoes precise temporal and spatial remodeling, which supports the morphological and functional changes essential for myogenesis [

14,

15]. This remodeling is facilitated by various actin-binding proteins (ABPs) that coordinate actin assembly, disassembly, and stability to support rapid cellular adaptations [

15,

16]. Among these actin-binding proteins (ABPs), calponin 3 (CNN3), a member of the calponin family, regulates actomyosin interactions, cytoskeletal rearrangement, and stress fiber formation through its actin-binding ability [

17,

18]. Therefore, CNN3 plays a pivotal role in actin cytoskeleton dynamics and maintaining cytoskeletal integrity [

18,

19,

20]. Previous studies have shown that CNN3 is expressed in myoblasts and is critical for actin stabilization during trophoblast fusion in embryonic development [

18,

21]. Muscle atrophy conditions, such as sarcopenia, muscular dystrophies, and cachexia, are marked by impaired myogenic differentiation and diminished muscle regeneration [

3,

22]. Recent evidence further indicates that CNN3 levels are reduced in various muscle atrophy models, including starvation-induced atrophy in murine myotubes [

23] and human tibial muscular dystrophy [

24]. Thus, it appears CNN3 may play a role in muscle development and preservation, and its reduction might impair myogenesis and contribute to muscle atrophy. Despite its established role in actin dynamics, the specific functions of CNN3 in skeletal myogenesis, particularly regarding myogenic differentiation and myotube formation, remain largely unexplored.

Emerging evidence suggests that mechanotransduction pathways, particularly those mediated by actin dynamics, are central to determining cellular fate by modulating transcriptional programs and cell cycle progression [

25]. In this aspect, the balance between filamentous actin (F-actin) and globular actin (G-actin) plays a critical role in these pathways by controlling the nuclear translocation of Yes-associated protein-1 (YAP1), a mechanosensitive transcriptional coactivator essential for cellular responses to mechanical cues [

26,

27]. In response to elevated F-actin levels, YAP1 translocates to the nucleus, promoting cell cycle progression and proliferation [

28]. This mechanism ultimately inhibits the differentiation of progenitor cells by maintaining them in a proliferative state rather than allowing them to transition into mature myogenic cells. Thus, this F-actin-driven YAP1 activation links cytoskeletal dynamics to the suppression of myogenesis by driving the expressions of genes associated with proliferation [

26,

27,

29]. Given the role played by CNN3 in actin remodeling, it is likely involved in modulating mechanosensitive YAP1 signaling during myogenic differentiation. However, the specific role of CNN3 remains to be elucidated, and understanding its contributions could offer significant insights into muscle development and regeneration mechanisms.

This study aimed to investigate the role of CNN3 in myogenic differentiation by analyzing its influence on actin cytoskeletal dynamics and key mechanosensitive signaling pathways critical for skeletal muscle homeostasis. Specifically, we examined the effects of CNN3 knockdown on actin remodeling, YAP1 nuclear translocation, cell cycle progression, and cell proliferation, as well as its downstream impact on the expression of myogenic factors and the transition from myoblasts to myotubes. This research is the first to identify CNN3 as a pivotal regulator of myoblast proliferation and differentiation, operating through its modulation of actin organization and mechanosensitive transcriptional programming.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

C2C12 myoblasts (ATCC, CRL-1772, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in growth medium (GM) composed of DMEM containing 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 100 units/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA). To induce differentiation, cells were seeded in 35 mm dishes (~1.3x10⁵ cells per dish) and maintained in GM until ~90% confluent. Differentiation was then initiated by switching to differentiation medium (DM; DMEM containing 2% horse serum (Gibco)). Cells were incubated in DM for up to five days with medium changes every 24 hrs.

2.2. Oligonucleotide Transfection

C2C12 cells were seeded in 35 mm dishes at a density of ~1.3×10⁵ cells per dish and allowed to reach 40–50% confluency over 20–24 hrs. Transfection was performed using 200 nM scrambled control RNA (scRNA, Genolution, Seoul, Korea), CNN3 siRNA (siCNN3-1, Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea), or an alternative CNN3 siRNA (siCNN3-2, Genolution) with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in serum-free DMEM for 4 hrs. Cells were then maintained in GM for 24 hrs. Oligonucleotide sequences are detailed in

Table S1.

2.3. RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted using a Total RNA Miniprep kit (Enzynomics, Daejeon, Korea) and quantified using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Keen Innovative Solutions, Daejeon, Korea). Complementary DNA was synthesized using the miScript II RT Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Relative mRNA levels were assessed via RT-

qPCR using SYBR Green (Enzynomics) in a LightCycler 480 (Roche Applied Science, Basel, Switzerland). Reactions were performed in triplicate, and expression levels were normalized versus GAPDH using the 2–ΔΔCt method. Primer sequences and conditions are listed in

Table S2.

2.4. Cytoplasmic and Nuclear Fraction Extraction

C2C12 cells were harvested with trypsin/EDTA (Gibco) 24 hrs after transfection, and cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were separated using NE-PER Reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were incubated on ice with CER I solution for 10 minutes, and then CER II solution was added, and incubation continued for one minute. Lysates were centrifuged at ~15,000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4°C. Supernatants (cytoplasmic fractions) were transferred to clean tubes, and the remaining residues were resuspended in NER solution to obtain nuclear fractions. Equal amounts of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were immunoblotted.

2.5. Immunoblot Analysis

Total protein was extracted using lysis buffer containing 1% phosphatase inhibitor cocktail II, 0.2 mM PMSF, and 2% Triton-X in PBS (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay. Samples were denatured at 100°C for 10 minutes, and equal amounts of protein (20 µg) were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA), blocked with 5% skimmed milk in TBST (0.5% Tween 20-TBS), and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies. The following day, membranes were washed and incubated with secondary antibodies diluted at 1:10,000. Blots were visualized using TOPviewTM ECL Femto Western Substrate (Enzynomics) and analyzed with Fusion Solo software (Paris, France). The antibodies used are listed in

Table S4.

2.6. Immunocytochemistry

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes, and blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin in PBS at room temperature for 2 hrs. Cells were then incubated with an anti-myosin heavy chain (MyHC) antibody (1:100 dilution) overnight at 4°C. After washing, samples were incubated with Alexa 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Invitrogen) for 1 hour and counterstained with Hoechst 33342. Images were captured from five randomly selected fields using a Leica fluorescence microscope. Experiments were performed using at least three independent replicates. MyHC-positive areas, nucleus numbers in myotubes, and myotube widths were determined using ImageJ software. Differentiation and fusion indexes were calculated as previously described [

12]. F-actin was stained with FITC-conjugated phalloidin (Sigma).

2.7. Cell Proliferation Assay

Cell proliferation was measured using Click-iT™ EdU kit (Invitrogen). Briefly, C2C12 cells were seeded in 8-chamber slides at 3x10⁴ cells/well and transiently transfected with scRNA or siCNN3. At 24 hrs post-transfection, cells were treated with 10 µM EdU for 4 hrs at 37℃, then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS, and incubated with Click-iT reaction cocktail. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342, and fluorescent images were captured using a Leica fluorescence microscope. EdU-positive and total cell numbers were counted in five random fields using ImageJ software, and experiments were performed independently at least three times.

2.8. Cell Viability

Myoblasts were seeded in 96-well plates at 10³ cells/well and transfected with siRNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After 24 hrs, cells were incubated in GM containing 10 µL of Quanti-Max WST-8 Cell Viability Assay solution (BioMax, Seoul, Korea) for 4 hrs at 37°C. Cell viability was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Model 680, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

2.10. Flow Cytometry

Myoblasts were collected using trypsin-EDTA, centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C, rinsed with PBS, fixed in 70% ethanol overnight at 4°C, and stained for 20 minutes using the Propidium Iodide Flow Cytometry Kit (ab139418, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) for cell cycle analysis, FITC-phalloidin for F-actin quantitation, or DNase I for G-actin quantitation. Samples were analyzed using a CytoFLEX instrument (Beckman Coulter, USA).

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as means ± standard errors (SEM) from at least three independent experiments. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare group differences. When significant differences were detected, post-hoc analysis was performed using Tukey’s test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

Actin dynamics are fundamental to myogenesis, integrating mechanosensitive transcriptional programs with myogenic gene expression and cell cycle regulation to ensure the precise control of myogenic processes [

9,

15]. Although CNN3 has been shown to play a crucial role in actin cytoskeleton dynamics in various contexts, its function in the differentiation of progenitor cells during myogenesis has remained unexplored. This study reveals for the first time the critical role played by CNN3 in myogenic differentiation by demonstrating its impact on actin remodeling, YAP1 signaling, and cell cycle progression in C2C12 myoblasts. Specifically, our findings demonstrate that (i) CNN3 expression is upregulated during differentiation, (ii) CNN3 knockdown elevates F-actin levels and promotes YAP1 nuclear localization, (iii) CNN3 depletion facilitates cell cycle progression and enhances myoblast proliferation, and (iv) CNN3 knockdown results in a marked decrease in the expression of myogenic regulatory factors, and thus, impairs differentiation, fusion, and myotube formation. These findings establish CNN3 as a key regulator of the F-actin/YAP axis, crucial for balancing cell proliferation and differentiation.

During myofiber formation, actin cytoskeletal remodeling is crucial for cellular morphology, membrane reconfiguration, and the activation of myogenic transcriptional programs [

6,

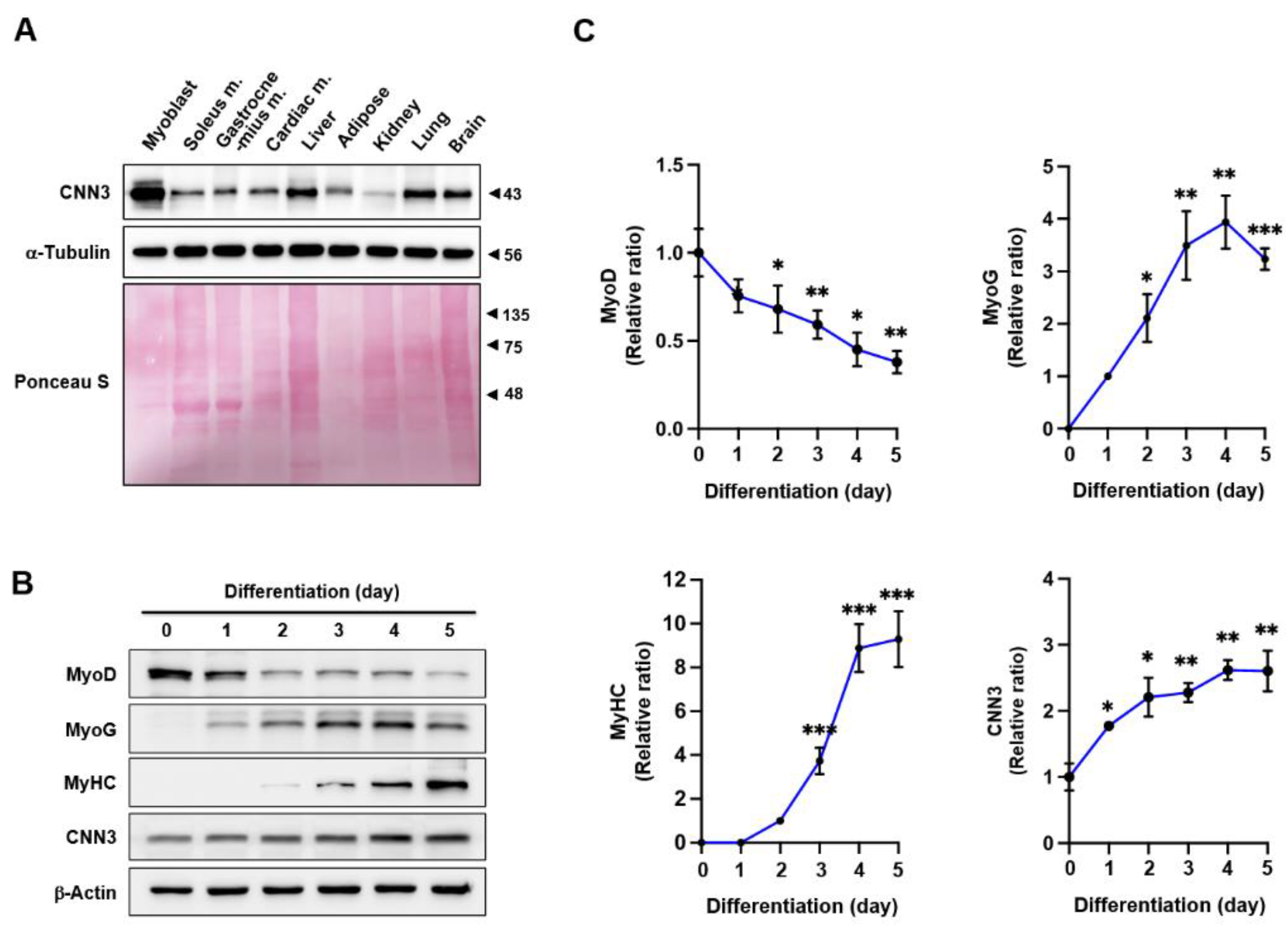

7]. Our findings indicate that CNN3 expressions increase at the onset of differentiation and remains steady throughout myotube formation (

Figure 1), implying its involvement in muscle development. Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of CNN3 in embryonic myogenesis, during which it is highly expressed in muscle tissues [

18,

33,

34]. CNN3 regulates actin cytoskeleton rearrangement during embryonic development and promotes cell fusion in trophoblasts and myoblasts [

18,

33]. Moreover, CNN3 knockout caused embryonic and postnatal lethality, highlighting its essential role in development [

34]. Our findings underscore the function of CNN3 in essential processes for myogenesis, similar to its developmental functions reported in other studies.

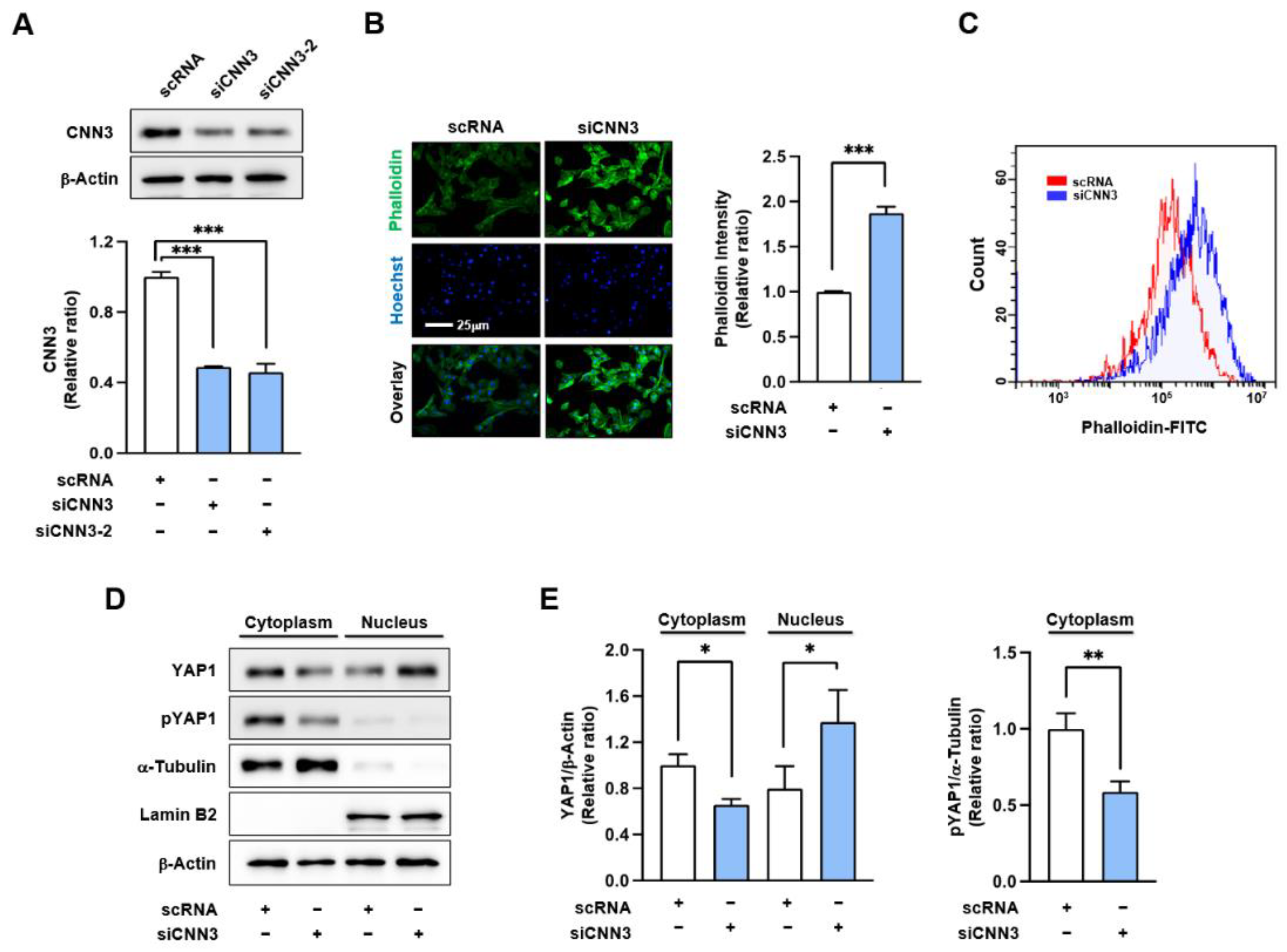

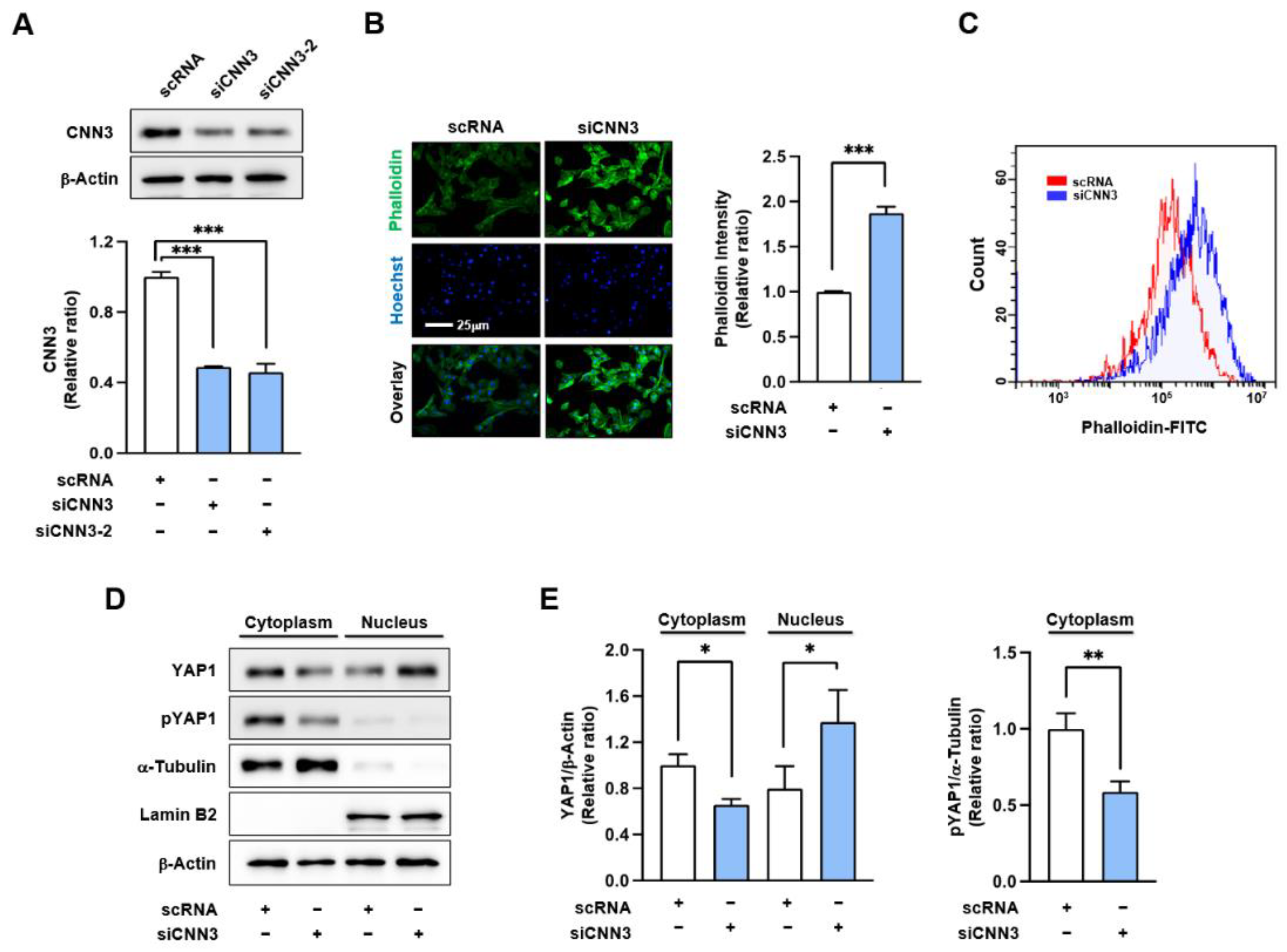

Our results further demonstrate that CNN3 knockdown increases F-actin accumulation, potentially contributing to YAP1 activation in response to mechanical stress (

Figure 2). This observation is consistent with findings in fibroblasts and epithelial cells, where CNN3 depletion has been shown to promote actin polymerization [

19,

35]. Moreover, CNN3 depletion in lens epithelial cells similarly reorganized actin stress fibers, stimulated focal adhesion formation, and activated YAP1 signaling [

36]. Although we were unable to measure actin polymerization rates directly, these observations highlight the critical role of CNN3 in cytoskeletal rearrangement. CNN3 appears to be essential for maintaining cytoskeletal integrity and regulating cell proliferation across diverse cellular contexts. Furthermore, the increased F-actin accumulation and subsequent YAP1 activation induced by siCNN3 in our model underscore the regulatory function of CNN3 in myogenesis via actin dynamics.

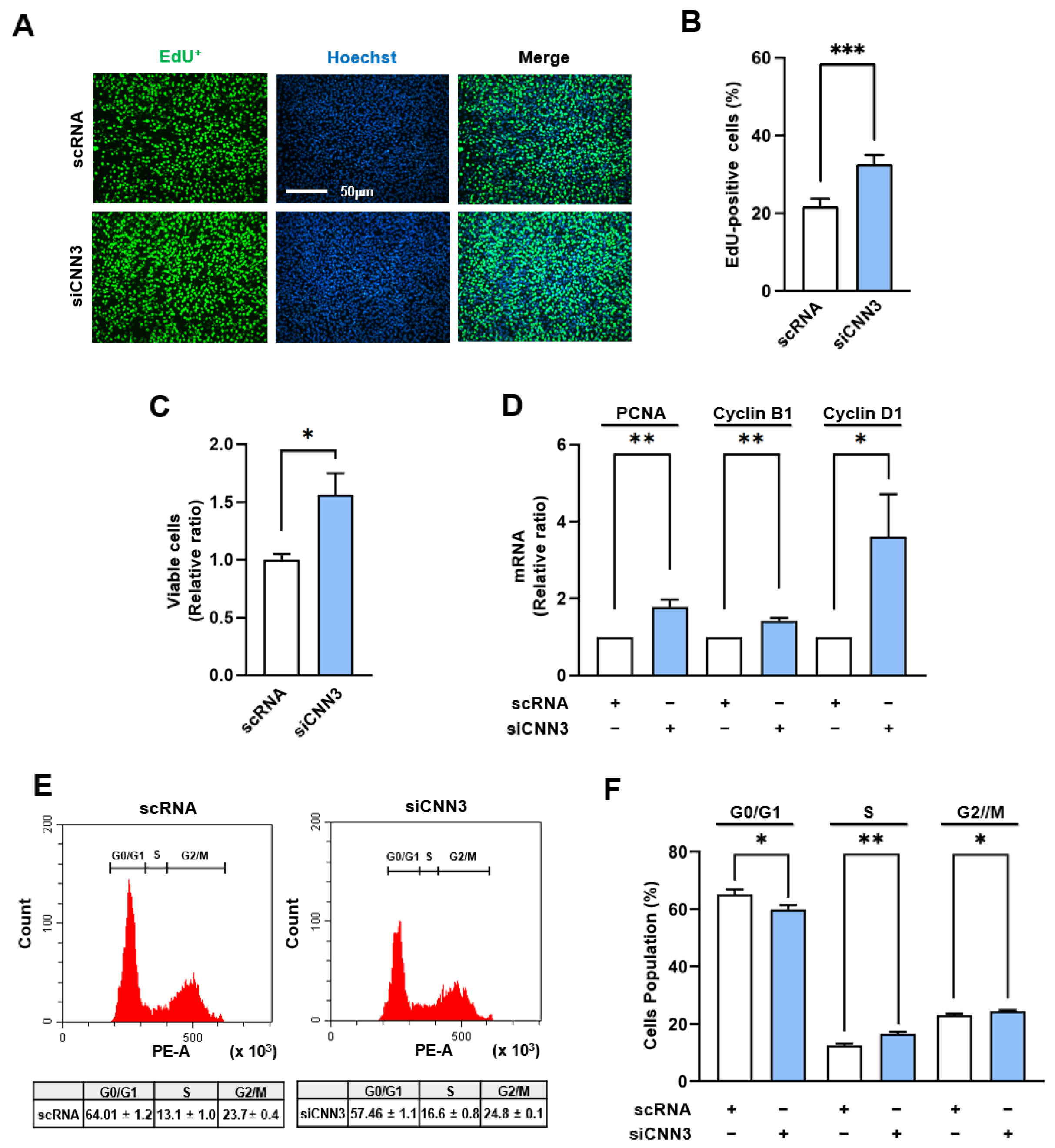

We observed that CNN3 knockdown significantly facilitates myoblast proliferation, as evidenced by increased cell viability, elevated EdU incorporation, and the upregulation of cell cycle-related genes (PCNA, cyclin B1, and cyclin D1) (Figure. 3). In addition, flow cytometry revealed the cell cycle progression in the S and G2/M phase in CNN3 depleted cells, suggesting promoted cell cycle progression. This increase in cell proliferation following CNN3 knockdown is associated with the activation of YAP1, which responds to cytoskeletal tension [

28,

37]. Because CNN3 depletion increased nuclear YAP1 levels by reducing its cytoplasmic phosphorylation, thereby preventing its degradation and increasing its nuclear accumulation. Balance between F-actin and G-actin is crucial in mechanotransduction pathways and influences the nuclear localization of YAP1 [

31,

38]. Moreover, elevated F-actin levels prompt the nuclear translocation of YAP1, thus driving cell cycle progression and proliferation, suppressing differentiation by maintaining progenitor cells in a proliferative state rather than allowing them to differentiate into mature muscle cells [

4,

31]. These findings suggest that CNN3 is essential for maintaining the mechanical cues necessary for YAP1 signaling, which promotes cell proliferation and survival.

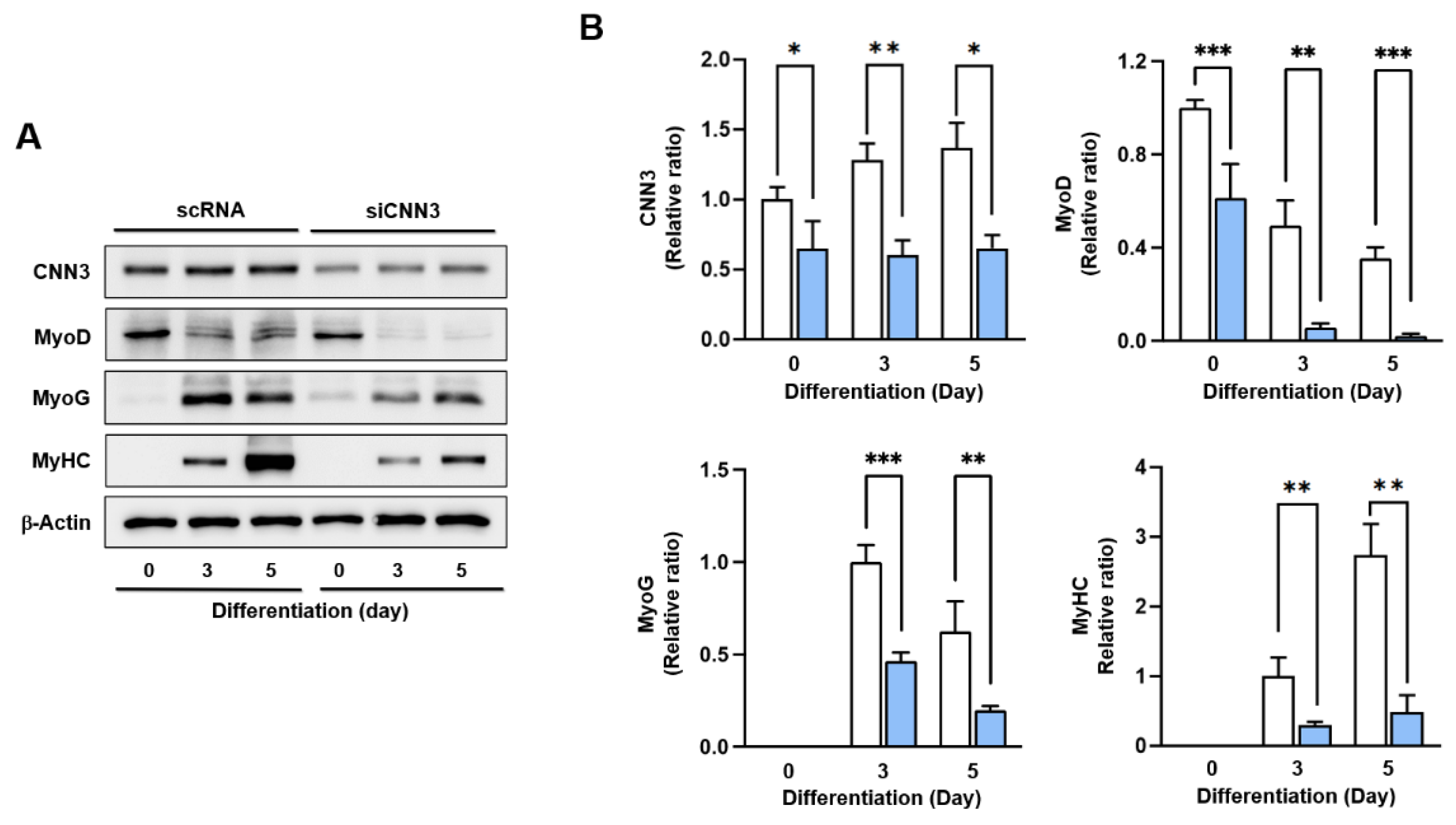

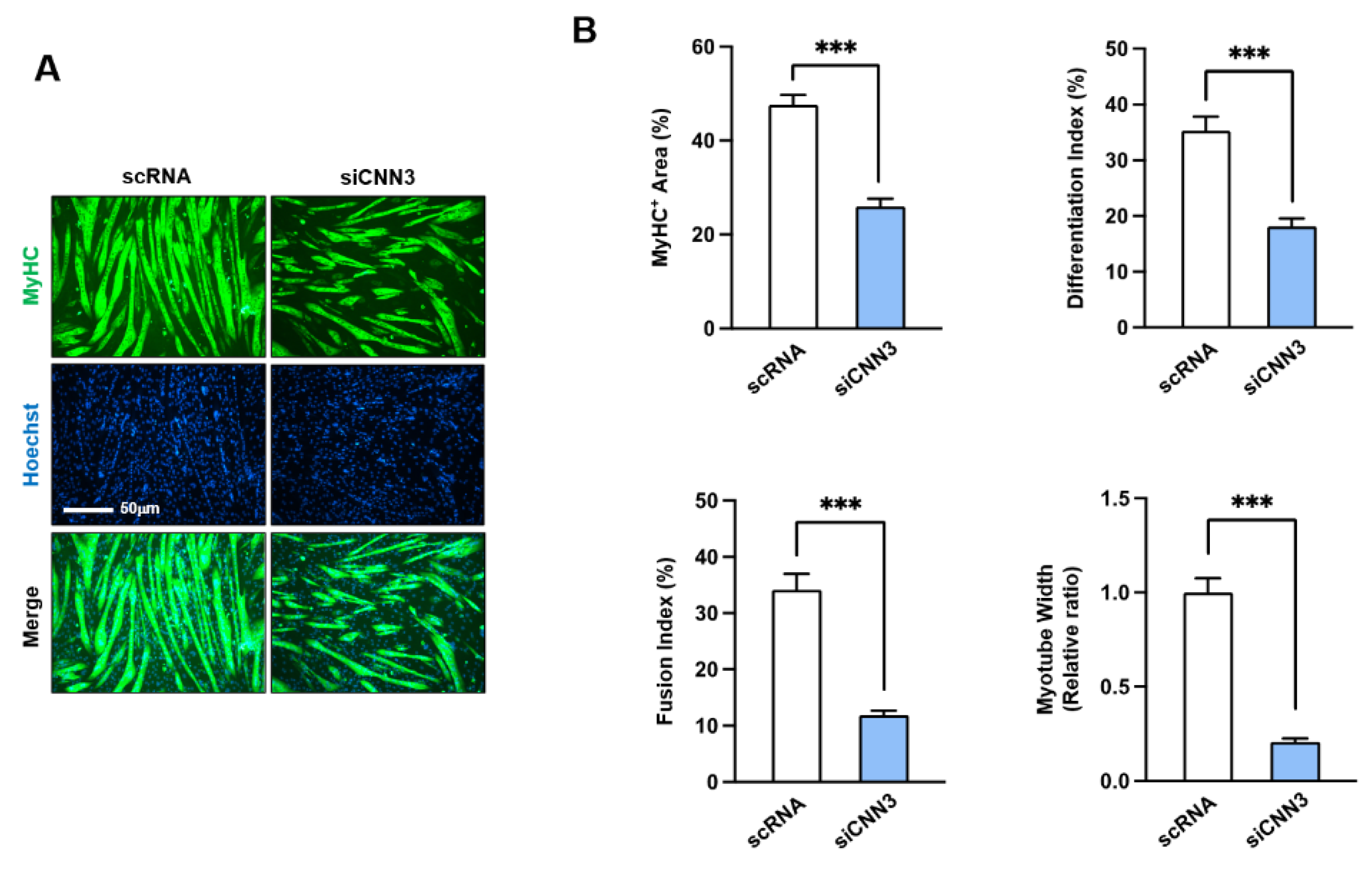

Throughout myogenesis, myoblast differentiation into myotubes requires an inverse relationship with proliferation, necessitating cell cycle arrest and cessation of proliferation [

4]. The temporal expression pattern of CNN3 during differentiation observed in this study suggests that CNN3 is crucial for exiting the proliferative cycle, thereby enabling cells to differentiate and fuse into myotubes. Recent studies have also established a connection between CNN3 expression and cell proliferation. For instance, overexpression of CNN3 inhibits the proliferation, migration, and invasion of non-small cell lung cancer cells [

39], whereas CNN3 knockout (-/-) embryos displayed increased proliferation of neuronal precursor cells [

40]. In agreement with these reports, our findings showed that CNN3 knockdown facilitated cell cycle progression and proliferation in myoblasts, leading to the suppression of myogenic differentiation (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Hence, the disrupted balance between proliferation and differentiation observed in CNN3-depleted myoblasts underscores the critical role of CNN3 in coordinating these processes during myogenesis.

The present study identifies CNN3 as a pivotal regulator of myoblast differentiation and proliferation due to its influence on actin cytoskeletal dynamics and the mechanosensitive transcription program for myogenic differentiation. CNN3 depletion leads to actin polymerization, stimulates nuclear translocations of YAP1, increases the expression of cell cycle-promoting genes, and consequently provokes the downregulation of key myogenic regulatory genes to inhibit myotube formation and myoblast proliferation. In addition, the study provides valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying skeletal myogenesis and identifies CNN3 as a potential therapeutic target for muscle-related disorders. Further investigations into the regulation and function of CNN3 would enhance our understanding of muscle biology and possibly lead to novel treatments for muscle degeneration and related conditions.

Figure 1.

Modulation of CNN3 expression during myoblast differentiation. (A) Immunoblotting was conducted to assess CNN3 expression levels in C2C12 myoblasts and various tissues from C57BL/6 mice; α-tubulin was used as a loading control. (B) C2C12 myoblasts were harvested on specified differentiation days, and the protein expression levels of MyoD, MyoG, MyHC, and CNN3 were determined by immunoblotting; β-actin was used as a loading control. (C) Protein levels were normalized versus β-actin, and relative expression ratios were calculated, setting day 0 as one for MyoD and CNN3, day 1 for MyoG, and day 2 for MyHC. Data are presented as means ± SEMs (n = 3), and asterisks indicate statistical significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Modulation of CNN3 expression during myoblast differentiation. (A) Immunoblotting was conducted to assess CNN3 expression levels in C2C12 myoblasts and various tissues from C57BL/6 mice; α-tubulin was used as a loading control. (B) C2C12 myoblasts were harvested on specified differentiation days, and the protein expression levels of MyoD, MyoG, MyHC, and CNN3 were determined by immunoblotting; β-actin was used as a loading control. (C) Protein levels were normalized versus β-actin, and relative expression ratios were calculated, setting day 0 as one for MyoD and CNN3, day 1 for MyoG, and day 2 for MyHC. Data are presented as means ± SEMs (n = 3), and asterisks indicate statistical significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

CNN3 knockdown elevated F-actin levels and increased nuclear localization of YAP1. C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with 200 nM of either control scRNA or siCNN3 (siCNN3-1 or siCNN3-2). (A) CNN3 expressions were assessed by immunoblotting 24 hrs after transfection. CNN3 expression levels were normalized to β-actin, and relative expression ratios were calculated with the control scRNA set to one. (B) Cells were stained with FITC-phalloidin (green) for F-actin and Hoechst 33342 (blue) for nuclei. Scale bar: 25 μm. Phalloidin intensities were quantified using ImageJ software. (C) F-actin levels were analyzed by flow cytometry after staining with FITC-phalloidin. (D) Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were immunoblotted for YAP1, pYAP1 (phosphorylated YAP1), and CNN3. α-Tubulin and lamin B2 served as cytoplasmic and nuclear markers, respectively, and β-actin was used as a loading control. (E) Protein levels were normalized versus β-actin, and relative expression ratios were calculated versus scRNA. Data are presented as means ± SEMs (n = 3), and asterisks indicate statistical significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

CNN3 knockdown elevated F-actin levels and increased nuclear localization of YAP1. C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with 200 nM of either control scRNA or siCNN3 (siCNN3-1 or siCNN3-2). (A) CNN3 expressions were assessed by immunoblotting 24 hrs after transfection. CNN3 expression levels were normalized to β-actin, and relative expression ratios were calculated with the control scRNA set to one. (B) Cells were stained with FITC-phalloidin (green) for F-actin and Hoechst 33342 (blue) for nuclei. Scale bar: 25 μm. Phalloidin intensities were quantified using ImageJ software. (C) F-actin levels were analyzed by flow cytometry after staining with FITC-phalloidin. (D) Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were immunoblotted for YAP1, pYAP1 (phosphorylated YAP1), and CNN3. α-Tubulin and lamin B2 served as cytoplasmic and nuclear markers, respectively, and β-actin was used as a loading control. (E) Protein levels were normalized versus β-actin, and relative expression ratios were calculated versus scRNA. Data are presented as means ± SEMs (n = 3), and asterisks indicate statistical significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

CNN3 depletion facilitated cell proliferation and cell cycle progression. C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with either control scRNA or siCNN3 and analyzed 24 hrs post-transfection. (A) Cell proliferation was evaluated by EdU incorporation (green) to label replicating cells, and Hoechst 33342 (blue) was used to counterstain nuclei. Scale bar: 50 µm. (B) The percentages of EdU-positive cells were determined using ImageJ software. (C) Viable cell numbers were measured using a cell viability assay kit. (D) mRNA levels of proliferation markers (PCNA, Cyclin B1, and Cyclin D1) were assessed by RT-qPCR and normalized versus GAPDH expression. (E-F) Cell cycle analysis was performed using flow cytometry with scatter plots. Data are presented as means ± SEMs (n = 3), and asterisks indicate statistical significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Figure 3.

CNN3 depletion facilitated cell proliferation and cell cycle progression. C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with either control scRNA or siCNN3 and analyzed 24 hrs post-transfection. (A) Cell proliferation was evaluated by EdU incorporation (green) to label replicating cells, and Hoechst 33342 (blue) was used to counterstain nuclei. Scale bar: 50 µm. (B) The percentages of EdU-positive cells were determined using ImageJ software. (C) Viable cell numbers were measured using a cell viability assay kit. (D) mRNA levels of proliferation markers (PCNA, Cyclin B1, and Cyclin D1) were assessed by RT-qPCR and normalized versus GAPDH expression. (E-F) Cell cycle analysis was performed using flow cytometry with scatter plots. Data are presented as means ± SEMs (n = 3), and asterisks indicate statistical significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Figure 4.

CNN3 knockdown suppressed expressions of myogenic regulatory factors. C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with either control scRNA or siCNN3, allowed to differentiate, and then harvested on specified differentiation days. (A) Protein expression levels of MyoD, MyoG, MyHC, and CNN3 were analyzed by immunoblotting. (B) Protein expression levels in scRNA (open column) and siCNN3 (blue column) were normalized versus β-actin. Results are presented as relative ratios versus scRNA levels on day 0 (for CNN3 and MyoD) or day 3 (for MyoG and MyHC). Data are presented as means ± SEMs (n = 3), and asterisks indicate statistical significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001); ns indicates non-significant.

Figure 4.

CNN3 knockdown suppressed expressions of myogenic regulatory factors. C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with either control scRNA or siCNN3, allowed to differentiate, and then harvested on specified differentiation days. (A) Protein expression levels of MyoD, MyoG, MyHC, and CNN3 were analyzed by immunoblotting. (B) Protein expression levels in scRNA (open column) and siCNN3 (blue column) were normalized versus β-actin. Results are presented as relative ratios versus scRNA levels on day 0 (for CNN3 and MyoD) or day 3 (for MyoG and MyHC). Data are presented as means ± SEMs (n = 3), and asterisks indicate statistical significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001); ns indicates non-significant.

Figure 5.

CNN3 depletion impaired myogenic differentiation. C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with control scRNA or siCNN3 and then allowed them to differentiate for 5 days. (A) Representative immunocytochemistry results after staining with MyHC antibody (green) and Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bar: 100 μm. (B) MyHC-positive areas, differentiation indices, fusion indices, and myotube widths were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Data are presented as means ± SEMs (n = 3), and asterisks indicate statistical significance (***P < 0.001).

Figure 5.

CNN3 depletion impaired myogenic differentiation. C2C12 myoblasts were transfected with control scRNA or siCNN3 and then allowed them to differentiate for 5 days. (A) Representative immunocytochemistry results after staining with MyHC antibody (green) and Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bar: 100 μm. (B) MyHC-positive areas, differentiation indices, fusion indices, and myotube widths were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Data are presented as means ± SEMs (n = 3), and asterisks indicate statistical significance (***P < 0.001).