Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 viral entry requires membrane fusion, facilitated by fusion peptides within its spike protein. While these predominantly hydrophobic peptides insert into target membranes, their precise mechanistic role in membrane fusion remains incompletely understood. Here, we investigate how FP1, the N-terminal fusion peptide sequence, modulates membrane stability and barrier function across various model membrane systems. Through a complementary suite of biophysical techniques—including electrophysiology, fluorescence spectroscopy, and atomic force microscopy—we demonstrate that FP1 significantly promotes pore formation and alters membrane mechanical properties. Our findings reveal that FP1 reduces the energy barrier for membrane defect formation and stimulates the appearance of stable conducting pores, with effects modulated by membrane composition and mechanical stress. The observed membrane-destabilizing activity suggests that beyond its anchoring function, FP1 may facilitate viral fusion by locally disrupting membrane integrity. These results provide mechanistic insights into SARS-CoV-2 membrane fusion mechanisms and highlight the complex interplay between fusion peptides and target membranes during viral entry.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

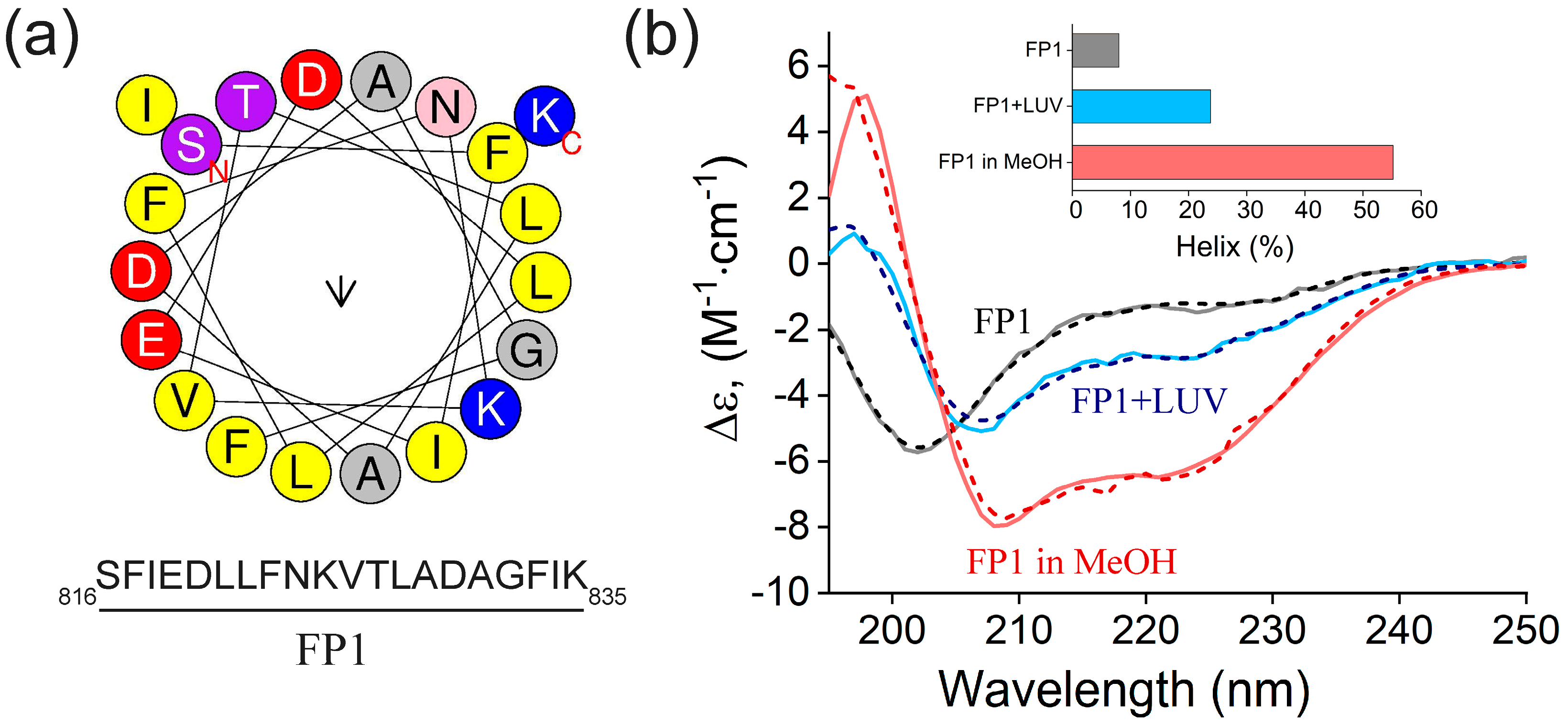

2.1. Circular Dichroism Analysis of FP1 Peptide: Structural Changes and Membrane Interaction

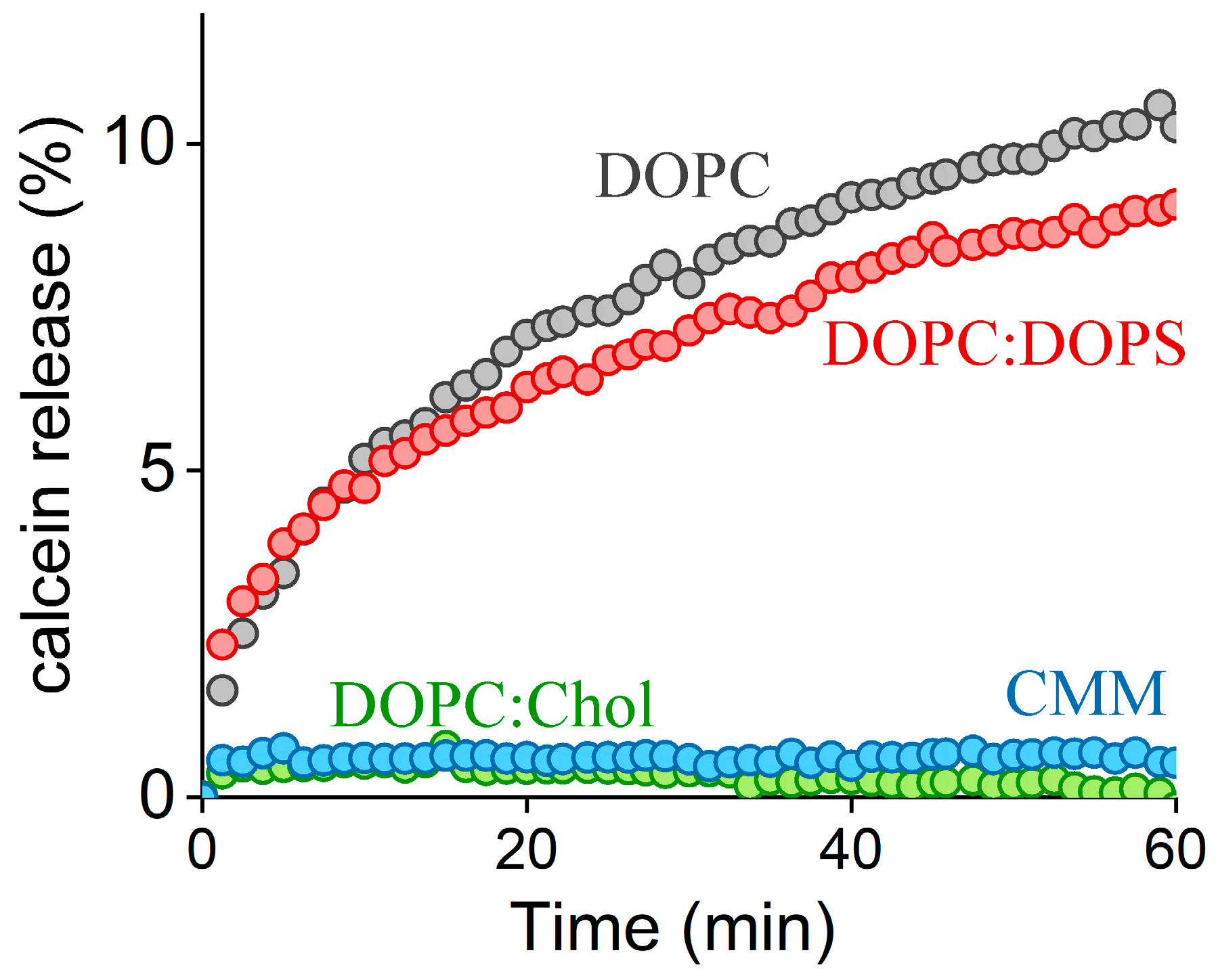

2.2. FP1-Induced Membrane Permeabilization: Effects of Lipid Composition

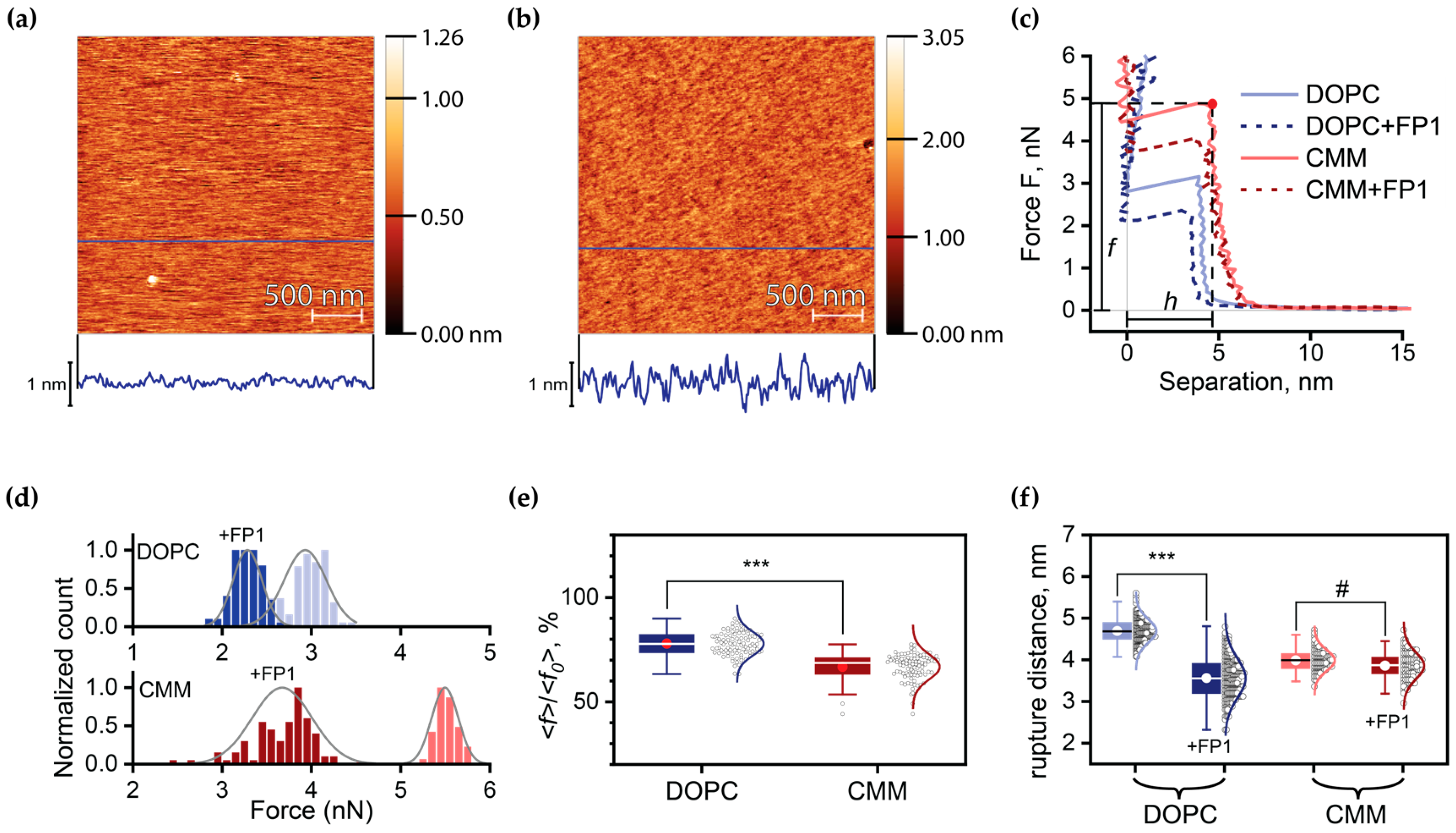

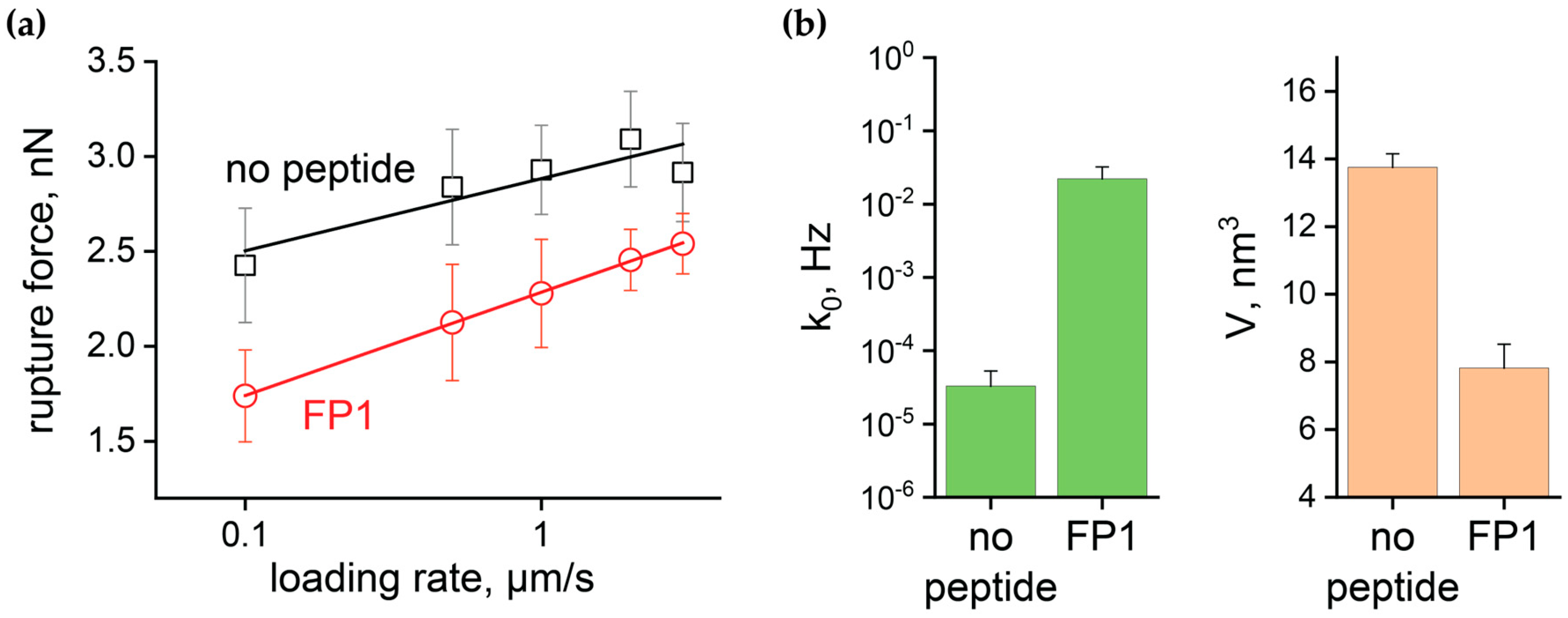

2.3. Quantitative Analysis of FP1-Induced Membrane Destabilization via AFM Force Spectroscopy

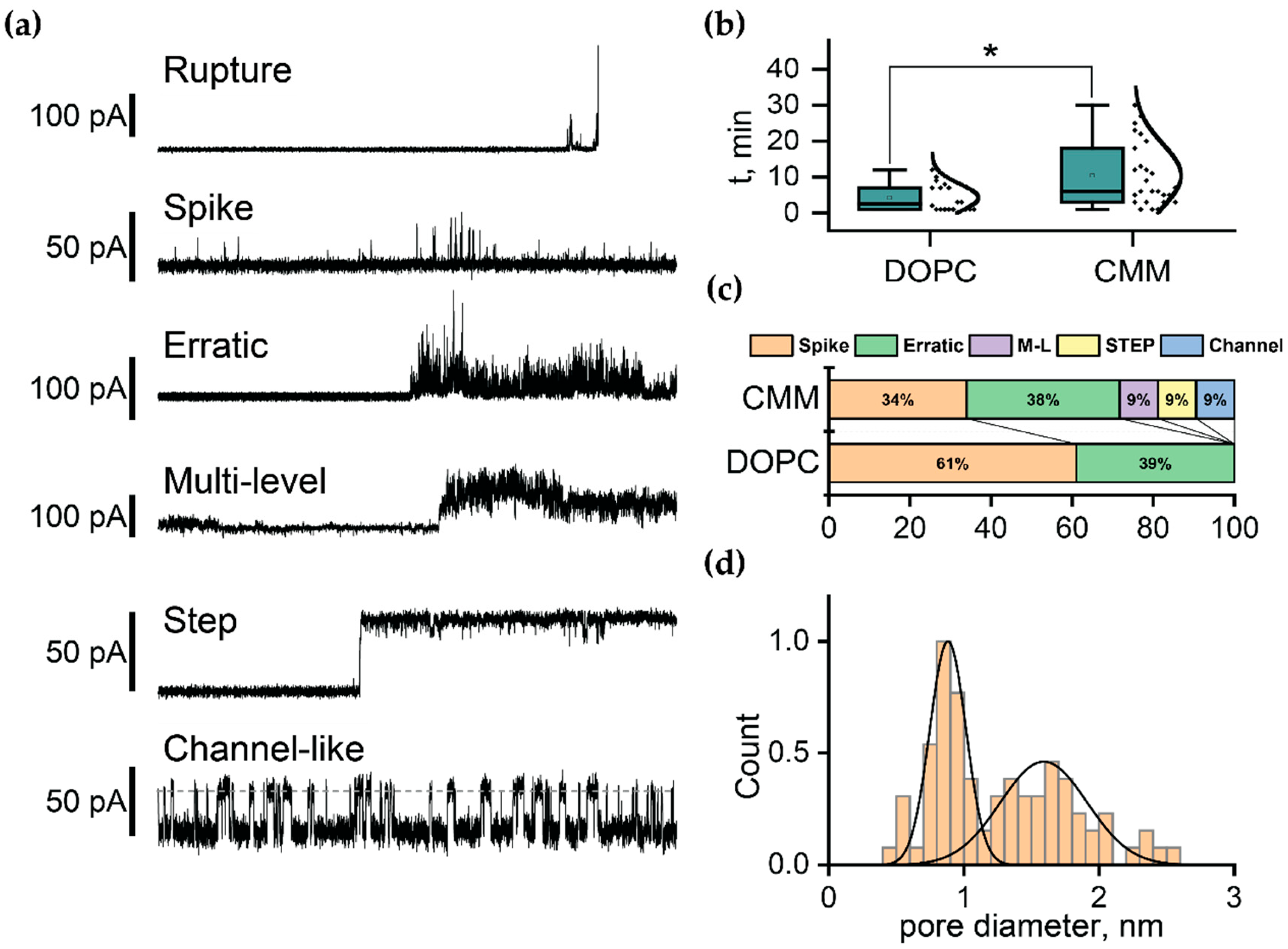

2.4. Electrophysiological Characterization of FP1-Induced Membrane Defects

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simon, M.; Veit, M.; Osterrieder, K.; Gradzielski, M. Surfactants – Compounds for Inactivation of SARS-CoV-2 and Other Enveloped Viruses. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 55, 101479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millet, J.K.; Whittaker, G.R. Physiological and Molecular Triggers for SARS-CoV Membrane Fusion and Entry into Host Cells. Virology 2018, 517, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, H.; Bhattacharjya, S. Mechanistic Insights of Host Cell Fusion of SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 from Atomic Resolution Structure and Membrane Dynamics. Biophys. Chem. 2020, 265, 106438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akimov, S.A.; Molotkovsky, R.J.; Kuzmin, P.I.; Galimzyanov, T.R.; Batishchev, O.V. Continuum Models of Membrane Fusion: Evolution of the Theory. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmans, M.; Marelli, G.; Smirnova, Y.G.; Müller, M. Mechanics of Membrane Fusion/Pore Formation. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2015, 185, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, S.; Shinoda, W. Free Energy Analysis along the Stalk Mechanism of Membrane Fusion. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlovsky, Y.; Kozlov, M.M. Stalk Model of Membrane Fusion: Solution of Energy Crisis. Biophys. J. 2002, 82, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeffner, S.; Reusch, T.; Weinhausen, B.; Salditt, T. Energetics of Stalk Intermediates in Membrane Fusion Are Controlled by Lipid Composition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlovsky, Y.; Chernomordik, L.V.; Kozlov, M.M. Lipid Intermediates in Membrane Fusion: Formation, Structure, and Decay of Hemifusion Diaphragm. Biophys. J. 2002, 83, 2634–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryham, R.J.; Klotz, T.S.; Yao, L.; Cohen, F.S. Calculating Transition Energy Barriers and Characterizing Activation States for Steps of Fusion. Biophys. J. 2016, 110, 1110–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, F.S.; Melikyan, G.B. The Energetics of Membrane Fusion from Binding, through Hemifusion, Pore Formation, and Pore Enlargement. J. Membr. Biol. 2004, 199, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, C.B.; Farzan, M.; Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 Entry into Cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, S.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, M.; Lan, Q.; Xu, W.; Wu, Y.; Ying, T.; Liu, S.; Shi, Z.; Jiang, S.; et al. Fusion Mechanism of 2019-nCoV and Fusion Inhibitors Targeting HR1 Domain in Spike Protein. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 765–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, B.; Li, J.; Chen, M.; Deng, R.; Wong, G.; Lavillette, D.; Meng, G. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Engagement of ACE2 Primes S2′ Site Cleavage and Fusion Initiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2022, 119, e2111199119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, T.; Peng, H.; Sterling, S.M.; Walsh, R.M.; Rawson, S.; Rits-Volloch, S.; Chen, B. Distinct Conformational States of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. Science 2020, 369, 1586–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.-H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.-M.; Yang, W.-L.; Yang, F.-Y.; Zhang, L.; Huang, W.-J.; Hou, W.; Fan, C.-F.; Jin, R.-H.; Feng, Y.-M.; Wang, Y.-C.; et al. Cathepsin L Plays a Key Role in SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Humans and Humanized Mice and Is a Promising Target for New Drug Development. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, S.L.; Jung, H.; Hummer, G. Binding of SARS-CoV-2 Fusion Peptide to Host Endosome and Plasma Membrane. J. Phys. Chem. B 2021, 125, 7732–7741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgun, D.; Lihan, M.; Kapoor, K.; Tajkhorshid, E. Binding Mode of SARS-CoV-2 Fusion Peptide to Human Cellular Membrane. Biophys. J. 2021, 120, 2914–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yuan, H.; Li, X.; Wang, H. Spike Protein Mediated Membrane Fusion during SARS-CoV-2 Infection. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 95, e28212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Wu, Z.; Chen, L. Different Binding Modes of SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 Fusion Peptides to Cell Membranes: The Influence of Peptide Helix Length. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 4261–4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, J.M.; Ward, A.E.; Odongo, L.; Tamm, L.K. Viral Membrane Fusion: A Dance Between Proteins and Lipids. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2023, 10, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernomordik, L.V.; Kozlov, M.M. Mechanics of Membrane Fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008, 15, 675–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, A.L.; Freed, J.H. SARS-CoV-2 Fusion Peptide Has a Greater Membrane Perturbating Effect than SARS-CoV with Highly Specific Dependence on Ca2+. J. Mol. Biol. 2021, 433, 166946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppisetti, R.K.; Fulcher, Y.G.; Van Doren, S.R. Fusion Peptide of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Rearranges into a Wedge Inserted in Bilayered Micelles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 13205–13211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Bidon, M.; Jaimes, J.A.; Whittaker, G.R.; Daniel, S. Coronavirus Membrane Fusion Mechanism Offers a Potential Target for Antiviral Development. Antiviral Res. 2020, 178, 104792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madu, I.G.; Roth, S.L.; Belouzard, S.; Whittaker, G.R. Characterization of a Highly Conserved Domain within the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Spike Protein S2 Domain with Characteristics of a Viral Fusion Peptide. J VIROL 2009, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacon, C.; Tucker, C.; Peng, L.; Lee, C.-C.D.; Lin, T.-H.; Yuan, M.; Cong, Y.; Wang, L.; Purser, L.; Williams, J.K.; et al. Broadly Neutralizing Antibodies Target the Coronavirus Fusion Peptide. 2022.

- Khelashvili, G.; Plante, A.; Doktorova, M.; Weinstein, H. Ca2+-Dependent Mechanism of Membrane Insertion and Destabilization by the SARS-CoV-2 Fusion Peptide. Biophys. J. 2021, 120, 1105–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria, A.; Batchu, K.C.; Matsarskaia, O.; Prévost, S.F.; Russo, D.; Natali, F.; Seydel, T.; Hoffmann, I.; Laux, V.; Haertlein, M.; et al. Strikingly Different Roles of SARS-CoV-2 Fusion Peptides Uncovered by Neutron Scattering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 2968–2979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.L.; Freed, J.H. Negatively Charged Residues in the Membrane Ordering Activity of SARS-CoV-1 and -2 Fusion Peptides. Biophys. J. 2022, 121, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalaín, J. SARS-CoV-2 Protein S Fusion Peptide Is Capable of Wrapping Negatively-Charged Phospholipids. Membranes 2023, 13, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Doren, S.R.; Scott, B.S.; Koppisetti, R.K. SARS-CoV-2 Fusion Peptide Sculpting of a Membrane with Insertion of Charged and Polar Groups. Structure 2023, 31, 1184–1199.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niort, K.; Dancourt, J.; Boedec, E.; Al Amir Dache, Z.; Lavieu, G.; Tareste, D. Cholesterol and Ceramide Facilitate Membrane Fusion Mediated by the Fusion Peptide of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 32729–32739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, S.; Mekhedov, E.; McCormick, C.D.; Blank, P.S.; Zimmerberg, J. Lipid-Dependence of Target Membrane Stability during Influenza Viral Fusion. J. Cell Sci. 2019, 132, jcs218321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlanda, P.; Mekhedov, E.; Waters, H.; Schwartz, C.L.; Fischer, E.R.; Ryham, R.J.; Cohen, F.S.; Blank, P.S.; Zimmerberg, J. The Hemifusion Structure Induced by Influenza Virus Haemagglutinin Is Determined by Physical Properties of the Target Membranes. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frolov, V.A.; Dunina-Barkovskaya, A.Y.; Samsonov, A.V.; Zimmerberg, J. Membrane Permeability Changes at Early Stages of Influenza Hemagglutinin-Mediated Fusion. Biophys. J. 2003, 85, 1725–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risselada, H.J.; Marelli, G.; Fuhrmans, M.; Smirnova, Y.G.; Grubmüller, H.; Marrink, S.J.; Müller, M. Line-Tension Controlled Mechanism for Influenza Fusion. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molotkovsky, R.; Galimzyanov, T.; Jiménez-Munguía, I.; Pavlov, K.; Batishchev, O.; Akimov, S. Switching between Successful and Dead-End Intermediates in Membrane Fusion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.L.; Tamm, L.K. Shallow Boomerang-Shaped Influenza Hemagglutinin G13A Mutant Structure Promotes Leaky Membrane Fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 37467–37475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribá, P.V.; Busquets, X.; Inokuchi, J.; Balogh, G.; Török, Z.; Horváth, I.; Harwood, J.L.; Vígh, L. Membrane Lipid Therapy: Modulation of the Cell Membrane Composition and Structure as a Molecular Base for Drug Discovery and New Disease Treatment. Prog. Lipid Res. 2015, 59, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, V.; Loi, S.; Müller, H.; Bamberg, E.; Butt, H.-J. Tip Penetration through Lipid Bilayers in Atomic Force Microscopy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2002, 23, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra V., O.; Fernandes, T.F.D.; Milhiet, P.-E.; Costa, L. Compression, Rupture, and Puncture of Model Membranes at the Molecular Scale. Langmuir 2020, 36, 5709–5716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafskaia, E.N.; Pavlova, E.R.; Latsis, I.A.; Malakhova, M.V.; Ivchenkov, D.V.; Bashkirov, P.V.; Kot, E.F.; Mineev, K.S.; Arseniev, A.S.; Klinov, D.V.; et al. Non-Toxic Antimicrobial Peptide Hm-AMP2 from Leech Metagenome Proteins Identified by the Gradient-Boosting Approach. Mater. Des. 2022, 224, 111364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafskaia, E.N.; Nadezhdin, K.D.; Talyzina, I.A.; Polina, N.F.; Podgorny, O.V.; Pavlova, E.R.; Bashkirov, P.V.; Kharlampieva, D.D.; Bobrovsky, P.A.; Latsis, I.A.; et al. Medicinal Leech Antimicrobial Peptides Lacking Toxicity Represent a Promising Alternative Strategy to Combat Antibiotic-Resistant Pathogens. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 180, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micsonai, A.; Moussong, É.; Wien, F.; Boros, E.; Vadászi, H.; Murvai, N.; Lee, Y.-H.; Molnár, T.; Réfrégiers, M.; Goto, Y.; et al. BeStSel: Webserver for Secondary Structure and Fold Prediction for Protein CD Spectroscopy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W90–W98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmore, L.; Wallace, B.A. Protein Secondary Structure Analyses from Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy: Methods and Reference Databases. Biopolymers 2008, 89, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzwarth, G.; Doty, P. The Ultraviolet Circular Dichroism of Polypeptides1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, R.; Douguet, D.; Antonny, B.; Drin, G. HELIQUEST: A Web Server to Screen Sequences with Specific α-Helical Properties. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 2101–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashkirov, P.V.; Kuzmin, P.I.; Chekashkina, K.; Arrasate, P.; Vera Lillo, J.; Shnyrova, A.V.; Frolov, V.A. Reconstitution and Real-Time Quantification of Membrane Remodeling by Single Proteins and Protein Complexes. Nat. Protoc. 2020, 15, 2443–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwood, S.; Choi, Y.; Leonenko, Z. Preparation of DOPC and DPPC Supported Planar Lipid Bilayers for Atomic Force Microscopy and Atomic Force Spectroscopy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 3514–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, E.; Heinrich, V.; Ludwig, F.; Rawicz, W. Dynamic Tension Spectroscopy and Strength of Biomembranes. Biophys. J. 2003, 85, 2342–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, H.-J.; Franz, V. Rupture of Molecular Thin Films Observed in Atomic Force Microscopy. I. Theory. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 66, 031601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loi, S.; Sun, G.; Franz, V.; Butt, H.-J. Rupture of Molecular Thin Films Observed in Atomic Force Microscopy. II. Experiment. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 66, 031602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akimov, S.A.; Volynsky, P.E.; Galimzyanov, T.R.; Kuzmin, P.I.; Pavlov, K.V.; Batishchev, O.V. Pore Formation in Lipid Membrane I: Continuous Reversible Trajectory from Intact Bilayer through Hydrophobic Defect to Transversal Pore. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basso, L.G.M.; Zeraik, A.E.; Felizatti, A.P.; Costa-Filho, A.J. Membranotropic and Biological Activities of the Membrane Fusion Peptides from SARS-CoV Spike Glycoprotein: The Importance of the Complete Internal Fusion Peptide Domain. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Biomembr. 2021, 1863, 183697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robustelli, J.; Baumgart, T. Membrane Partitioning and Lipid Selectivity of the N-Terminal Amphipathic H0 Helices of Endophilin Isoforms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Biomembr. 2021, 1863, 183660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, A.; Haldar, S.; Wang, E.; Blank, P.S.; Akimov, S.A.; Galimzyanov, T.R.; Pastor, R.W.; Zimmerberg, J. Planar Aggregation of the Influenza Viral Fusion Peptide Alters Membrane Structure and Hydration, Promoting Poration. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliger, Y.; Aharoni, A.; Rapaport, D.; Jones, P.; Blumenthal, R.; Shai, Y. Fusion Peptides Derived from the HIV Type 1 Glycoprotein 41 Associate within Phospholipid Membranes and Inhibit Cell-Cell Fusion. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 13496–13505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.K. Architecture of a Nascent Viral Fusion Pore. EMBO J. 2010, 29, 1299–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-Medina, N.; Mescola, A.; Alessandrini, A. Effects of the Peptide Magainin H2 on Supported Lipid Bilayers Studied by Different Biophysical Techniques. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Biomembr. 2018, 1860, 2635–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Dalzini, A.; Song, L. Cholesterol and Phosphatidylethanolamine Lipids Exert Opposite Effects on Membrane Modulations Caused by the M2 Amphipathic Helix. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Biomembr. 2019, 1861, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franquelim, H.G.; Gaspar, D.; Veiga, A.S.; Santos, N.C.; Castanho, M.A.R.B. Decoding Distinct Membrane Interactions of HIV-1 Fusion Inhibitors Using a Combined Atomic Force and Fluorescence Microscopy Approach. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Biomembr. 2013, 1828, 1777–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashkirov, P.V.; Kuzmin, P.I.; Vera Lillo, J.; Frolov, V.A. Molecular Shape Solution for Mesoscopic Remodeling of Cellular Membranes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2022, 51, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Composition | Molar ratios | Abbreviation |

| DOPC | 100 | - |

| DOPC-Chol | 70-30 | - |

| DOPC-DOPS | 90-10 | - |

| DOPC:Chol:DOPE:DOPS | 35.7:35:20.9:8.3 [41] | CMM |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).