Submitted:

13 December 2024

Posted:

16 December 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

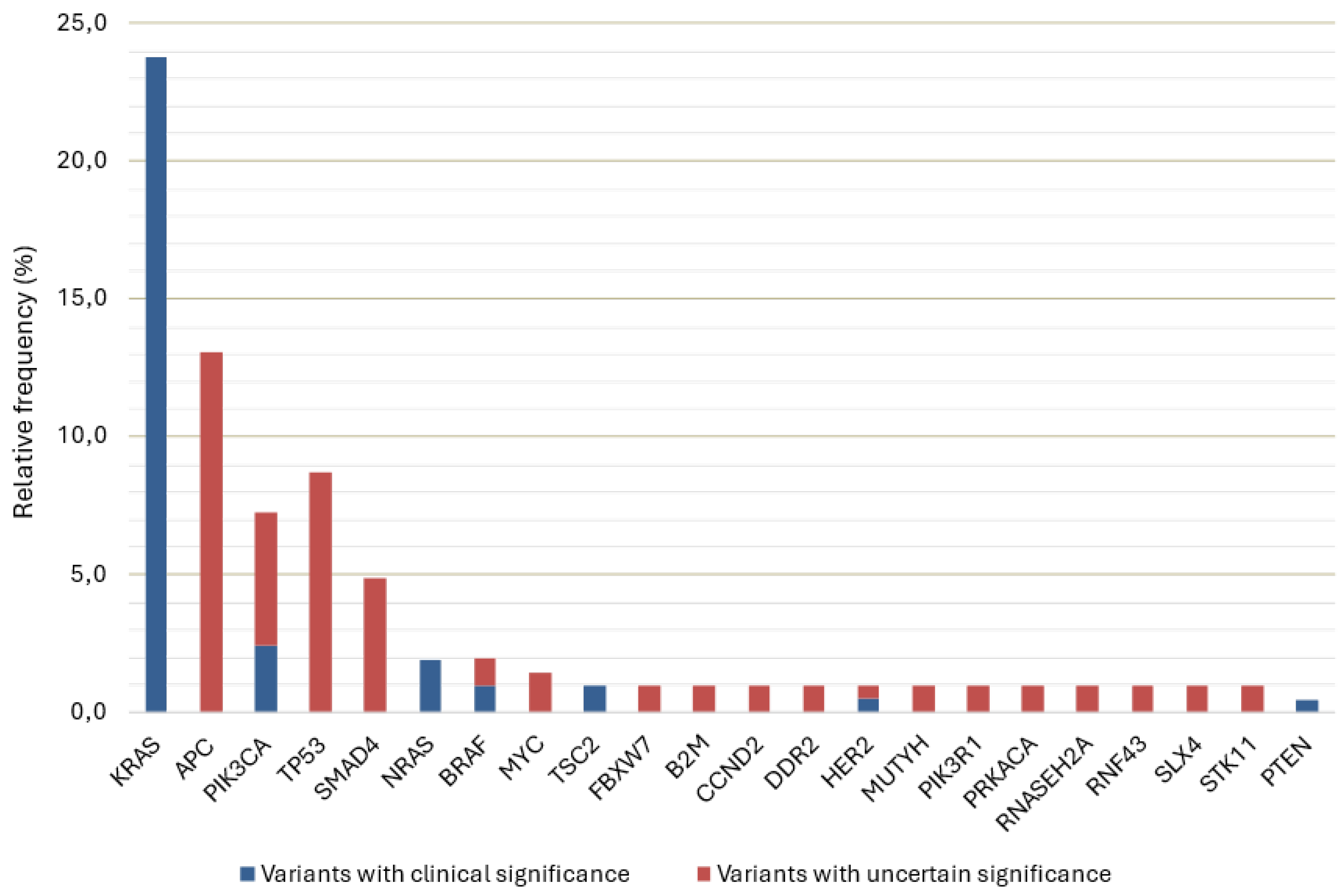

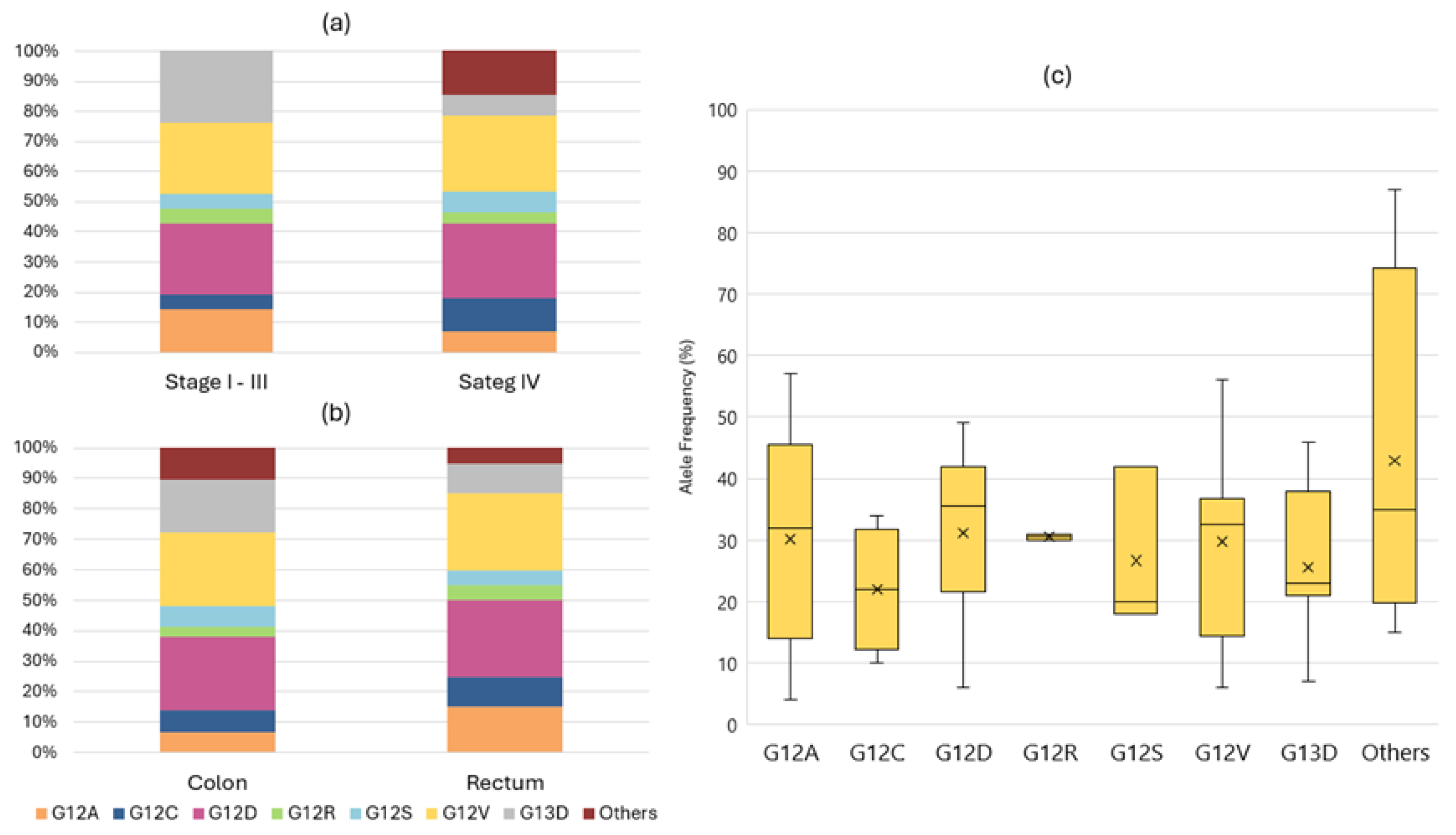

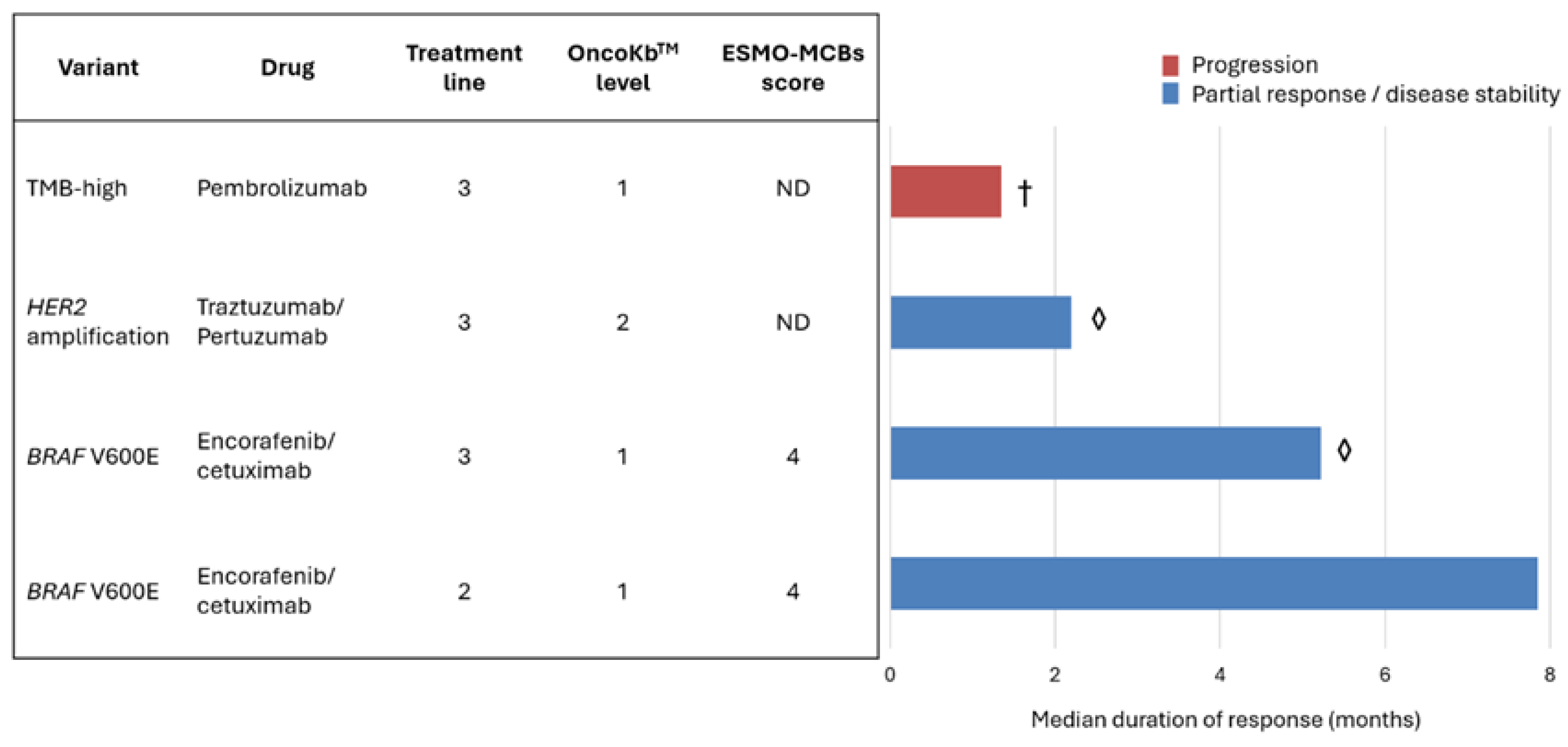

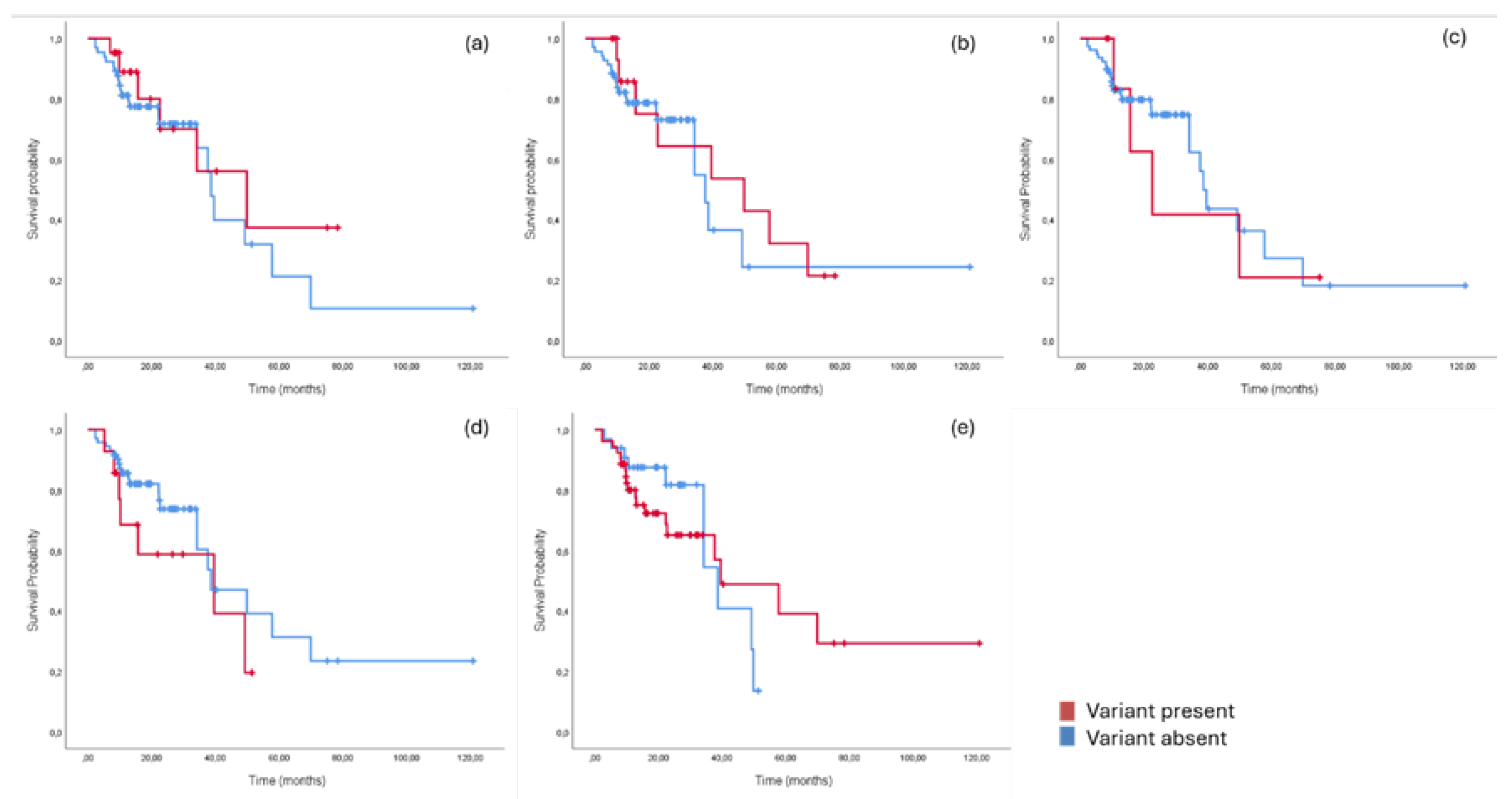

Background: Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most diagnosed cancer globally and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Despite advancements, metastatic CRC (mCRC) has a five-year survival rate below 20%. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) can identify rare actionable mutations and assess tumour mutational burden (TMB), but its clinical utility in mCRC is debated due to limited survival improvement and cost-effectiveness concerns. Methods: This retrospective study included mCRC patients (≥18 years) treated at a single oncology center who underwent NGS during treatment planning. Tumour samples were analyzed using either a 52-gene Oncomine™ Focus Assay or a 500+ gene Oncomine™ Comprehensive Assay Plus. Variants were classified by clinical significance (ESMO ESCAT) and potential benefit (ESMO-MCBS and OncoKBTM). Kaplan-Meier and Cox regression analyses evaluated survival outcomes, with significance at p<0.005. Results: Eighty-six metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients were analysed, all MMR proficient. Most cases (73.3%) underwent sequencing at metastatic diagnosis, using primary tumour samples (74.4%) and a focused NGS assay (75.6%). A total of 206 somatic variants were detected in 86.0% of patients, 31.1% of which were classified as clinically significant, predominantly KRAS mutations (76.6%), with G12D and G12V variants as the most frequent. Median overall survival (OS) was 39.5 months, with no single mutation predictive of OS. Among 33.7% RAS/BRAF wild-type patients, 65.5% received anti-EGFR therapies. Eleven patients (12.8%) had other actionable variants ESCAT level I-II, including four identified as TMB-high, four KRAS G12C, two BRAF V600E and one HER2 amplification. Four received OncoKbTM level 1-2 and ESMO-MCBS score 4, leading to disease control in three cases. Conclusions: NGS enables the detection of rare variants, supports personalized treatments, and expands therapeutic options. As new drugs emerge and genomic data integration improves, NGS is poised to enhance real-world mCRC management.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

2.2. Molecular Studies

2.3. Variant and Targeted Treatment Classification

2.4. Patient Characterization

2.5. Statistical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Detected Variants

3.3. Actionability and Therapeutic Implications

3.4. Prognostic Significance of NGS-Detected Variants

3.5. Factors Impacting NGS Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biller, L.H.; Schrag, D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. JAMA 2021, 325, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doleschal, B.; Petzer, A.; Rumpold, H. Current Concepts of Anti-EGFR Targeting in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Front Oncol 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, A.; Adam, R.; Roselló, S.; Arnold, D.; Normanno, N.; Taïeb, J.; Seligmann, J.; De Baere, T.; Osterlund, P.; Yoshino, T.; et al. Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Annals of Oncology 2023, 34, 10–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Chee, C.E.; Wong, W.; Lam, R.C.T.; Tan, I.B.H.; Ma, B.B.Y. Current Advances in Targeted Therapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer – Clinical Translation and Future Directions. Cancer Treat Rev 2024, 125, 102700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosele, M.F.; Westphalen, C.B.; Stenzinger, A.; Barlesi, F.; Bayle, A.; Bièche, I.; Bonastre, J.; Castro, E.; Dienstmann, R.; Krämer, A.; et al. Recommendations for the Use of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for Patients with Advanced Cancer in 2024: A Report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Annals of Oncology 2024, 35, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, A.J.; Gruber, A.J.; Kinnersley, B.; Chubb, D.; Frangou, A.; Caravagna, G.; Noyvert, B.; Lakatos, E.; Wood, H.M.; Thorn, S.; et al. The Genomic Landscape of 2,023 Colorectal Cancers. Nature 2024, 633, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network Colon Cancer (Version 5.2024).

- Lee, S.E.; Park, H.Y.; Hwang, D.-Y.; Han, H.S. High Concordance of Genomic Profiles between Primary and Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1Stockley, T.L.; Oza, A.M.; Berman, H.K.; Leighl, N.B.; Knox, J.J.; Shepherd, F.A.; Chen, E.X.; Krzyzanowska, M.K.; Dhani, N.; oshua, A.M.; et al. Molecular Profiling of Advanced Solid Tumors and Patient Outcomes with Genotype-Matched Clinical Trials: The Princess Margaret IMPACT/COMPACT Trial. Genome Med 2016, 8, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, L.; Saleh, R.R.; Avery, L.; Del Rossi, S.; Yu, C.; Bedard, P.L. Clinical Utility of Tumor Next-Generation Sequencing Panel Testing to Inform Treatment Decisions for Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors in a Tertiary Care Center. JCO Precis Oncol 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hernando-Calvo, A.; Nguyen, P.; Bedard, P.L.; Chan, K.K.W.; Saleh, R.R.; Weymann, D.; Yu, C.; Amir, E.; Regier, D.A.; Gyawali, B.; et al. Impact on Costs and Outcomes of Multi-Gene Panel Testing for Advanced Solid Malignancies: A Cost-Consequence Analysis Using Linked Administrative Data. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 69, 102443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.; Li, F.; Wu, M.; Luo, T.; Hammarström, K.; Torell, E.; Ljuslinder, I.; Mezheyeuski, A.; Edqvist, P.-H.; Löfgren-Burström, A.; et al. Prognostic Genome and Transcriptome Signatures in Colorectal Cancers. Nature 2024, 633, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornish, A.J.; Gruber, A.J.; Kinnersley, B.; Chubb, D.; Frangou, A.; Caravagna, G.; Noyvert, B.; Lakatos, E.; Wood, H.M.; Thorn, S.; et al. The Genomic Landscape of 2,023 Colorectal Cancers. Nature 2024, 633, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.H.; Yu, G.Y.; Hong, Y.G.; Lian, W.; Chouhan, H.; Xu, Y.; Liu, L.J.; Bai, C.G.; Zhang, W. Clinical Significance of Multiple Gene Detection with a 22-Gene Panel in Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Specimens of 207 Colorectal Cancer Patients. Int J Clin Oncol 2019, 24, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Song, I.H.; Lee, A.; Kang, J.; Lee, Y.S.; Lee, I.K.; Song, Y.S.; Lee, S.H. Enhancing the Landscape of Colorectal Cancer Using Targeted Deep Sequencing. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 8154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.M.; Datto, M.; Duncavage, E.J.; Kulkarni, S.; Lindeman, N.I.; Roy, S.; Tsimberidou, A.M.; Vnencak-Jones, C.L.; Wolff, D.J.; Younes, A.; et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation and Reporting of Sequence Variants in Cancer. The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics 2017, 19, 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, S.-F.; Cai, Z.-Z.; Kuai, W.-H.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.-T. Universal Cutoff for Tumor Mutational Burden in Predicting the Efficacy of Anti-PD-(L)1 Therapy for Advanced Cancers. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, J.; Chakravarty, D.; Dienstmann, R.; Jezdic, S.; Gonzalez-Perez, A.; Lopez-Bigas, N.; Ng, C.K.Y.; Bedard, P.L.; Tortora, G.; Douillard, J.-Y.; et al. A Framework to Rank Genomic Alterations as Targets for Cancer Precision Medicine: The ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of Molecular Targets (ESCAT). Annals of Oncology 2018, 29, 1895–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suehnholz, S.P.; Nissan, M.H.; Zhang, H.; Kundra, R.; Nandakumar, S.; Lu, C.; Carrero, S.; Dhaneshwar, A.; Fernandez, N.; Xu, B.W.; et al. Quantifying the Expanding Landscape of Clinical Actionability for Patients with Cancer. Cancer Discov 2024, 14, 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherny, N.I.; Dafni, U.; Bogaerts, J.; Latino, N.J.; Pentheroudakis, G.; Douillard, J.-Y.; Tabernero, J.; Zielinski, C.; Piccart, M.J.; de Vries, E.G.E. ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale Version 1. 1. Annals of Oncology 2017, 28, 2340–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravarty, D.; Gao, J.; Phillips, S.; Kundra, R.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Rudolph, J.E.; Yaeger, R.; Soumerai, T.; Nissan, M.H.; et al. OncoKB: A Precision Oncology Knowledge Base. JCO Precis Oncol 2017, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayle, A.; Basile, D.; Garinet, S.; Rance, B.; Laurent-Puig, P.; Blons, H.; Taieb, J.; Perkins, G. Next-Generation Sequencing Targeted Panel in Routine Care for Metastatic Colon Cancers. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13, 5750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulet Margalef, N.; Castillo, C.; Mosteiro, M.; Pérez, X.; Aguilar, S.; Ruíz-Pace, F.; Gil, M.; Cuadra, C.; Ruffinelli, J.C.; Martínez, M.; et al. Genomically Matched Therapy in Refractory Colorectal Cancer According to ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of Molecular Targets: Experience of a Comprehensive Cancer Centre Network. Mol Oncol 2023, 17, 1908–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiekman, I.A.C.; Zeverijn, L.J.; Geurts, B.S.; Verkerk, K.; Haj Mohammad, S.F.; van der Noort, V.; Roepman, P.; de Leng, W.W.J.; Jansen, A.M.L.; Gootjes, E.C.; et al. Trastuzumab plus Pertuzumab for HER2-Amplified Advanced Colorectal Cancer: Results from the Drug Rediscovery Protocol (DRUP). Eur J Cancer 2024, 202, 113988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meric-Bernstam, F.; Hurwitz, H.; Raghav, K.P.S.; McWilliams, R.R.; Fakih, M.; VanderWalde, A.; Swanton, C.; Kurzrock, R.; Burris, H.; Sweeney, C.; et al. Pertuzumab plus Trastuzumab for HER2-Amplified Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (MyPathway): An Updated Report from a Multicentre, Open-Label, Phase 2a, Multiple Basket Study. Lancet Oncol 2019, 20, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manca, P.; Corallo, S.; Lonardi, S.; Fucà, G.; Busico, A.; Leone, A.G.; Corti, F.; Antoniotti, C.; Procaccio, L.; Smiroldo, V.; et al. Variant Allele Frequency in Baseline Circulating Tumour DNA to Measure Tumour Burden and to Stratify Outcomes in Patients with RAS Wild-Type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Translational Objective of the Valentino Study. Br J Cancer 2022, 126, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-Y.; Shen, M.-Y.; Chen, W.T.-L.; Yang, C.-A. Evaluation of the Prognostic Value of Low-Frequency KRAS Mutation Detection in Circulating Tumor DNA of Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J Pers Med 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, K.; Bao, Q.; Zhao, T.; Wang, H.; Huang, L.; Wang, K.; Xing, B. Comparing Baseline VAF in Circulating Tumor DNA and Tumor Tissues Predicting Prognosis of Patients with Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastases after Curative Resection. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2024, 48, 102464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvivier, H.L.; Rothe, M.; Mangat, P.K.; Garrett-Mayer, E.; Ahn, E.R.; Al Baghdadi, T.; Alva, A.S.; Dublis, S.A.; Cannon, T.L.; Calfa, C.J.; et al. Pembrolizumab in Patients With Tumors With High Tumor Mutational Burden: Results From the Targeted Agent and Profiling Utilization Registry Study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2023, 41, 5140–5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.H.; Yu, G.Y.; Hong, Y.G.; Lian, W.; Chouhan, H.; Xu, Y.; Liu, L.J.; Bai, C.G.; Zhang, W. Clinical Significance of Multiple Gene Detection with a 22-Gene Panel in Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded Specimens of 207 Colorectal Cancer Patients. Int J Clin Oncol 2019, 24, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schell, M.J.; Yang, M.; Teer, J.K.; Lo, F.Y.; Madan, A.; Coppola, D.; Monteiro, A.N.A.; Nebozhyn, M. V.; Yue, B.; Loboda, A.; et al. A Multigene Mutation Classification of 468 Colorectal Cancers Reveals a Prognostic Role for APC. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 11743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaiano, A.; Santorsola, M.; Capuozzo, M.; Perri, F.; Circelli, L.; Cascella, M.; Ianniello, M.; Sabbatino, F.; Granata, V.; Izzo, F.; et al. The Prognostic Role of P53 Mutations in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2023, 186, 104018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Z.B.; Duan, C.Y.; Li, C.B.; Cui, L.; Ogino, S. Prognostic Role of Tumor PIK3CA Mutation in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Oncol 2016, 27, 1836–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.-C.; Rau, K.-M.; Liu, K.-W.; Chiu, C.-C.; Chen, C.-I.; Song, L.-C.; Chen, H.-P. Prognostic Impact of Codon-Specific KRAS Mutational Status on Survival in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Treated with TAS-102 or Regorafenib. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2024, 42, 75–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhullar, D.S.; Barriuso, J.; Mullamitha, S.; Saunders, M.P.; O’Dwyer, S.T.; Aziz, O. Biomarker Concordance between Primary Colorectal Cancer and Its Metastases. EBioMedicine 2019, 40, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massard, C.; Michiels, S.; Ferté, C.; Le Deley, M.-C.; Lacroix, L.; Hollebecque, A.; Verlingue, L.; Ileana, E.; Rosellini, S.; Ammari, S.; et al. High-Throughput Genomics and Clinical Outcome in Hard-to-Treat Advanced Cancers: Results of the MOSCATO 01 Trial. Cancer Discov 2017, 7, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Tourneau, C.; Delord, J.-P.; Gonçalves, A.; Gavoille, C.; Dubot, C.; Isambert, N.; Campone, M.; Trédan, O.; Massiani, M.-A.; Mauborgne, C.; et al. Molecularly Targeted Therapy Based on Tumour Molecular Profiling versus Conventional Therapy for Advanced Cancer (SHIVA): A Multicentre, Open-Label, Proof-of-Concept, Randomised, Controlled Phase 2 Trial. Lancet Oncol 2015, 16, 1324–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, S.N.; Peneva, D.; Cuyun Carter, G.; Palomares, M.R.; Thakkar, S.; Hall, D.W.; Dalglish, H.; Campos, C.; Yermilov, I. Comprehensive Review on the Clinical Impact of Next-Generation Sequencing Tests for the Management of Advanced Cancer. JCO Precis Oncol 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kato, S.; Schwaederlé, M.C.; Fanta, P.T.; Okamura, R.; Leichman, L.; Lippman, S.M.; Lanman, R.B.; Raymond, V.M.; Talasaz, A.; Kurzrock, R. Genomic Assessment of Blood-Derived Circulating Tumor DNA in Patients With Colorectal Cancers: Correlation With Tissue Sequencing, Therapeutic Response, and Survival. JCO Precis Oncol 2019, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, P.; Alifrangis, C.; Chandrasinghe, P.; Cereser, B.; Del Bel Belluz, L.; Leo, C.A.; Moderau, N.; Tabassum, N.; Warusavitarne, J.; Krell, J.; et al. The Benefit of Tumor Molecular Profiling on Predicting Treatments for Colorectal Adenocarcinomas. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 11371–11376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristics | n =86 (%) | |

| Sex Male Female |

57 (66.3) 29 (33.7) |

|

| Age (years) Median (amplitude) |

64.5 (27-80) |

|

| Stage at diagnosis II III IV |

9 (10.5) 28 (32.6) 49 (56.9) |

|

| Location of primary Colon Rectum |

49 (57.0) 37 (43.0) |

|

| Sidedness Left Right |

72 (83.7) 14 (16.3) |

|

| MMRp | 86 (100) | |

| RAS/BRAF mutant | 56 (65.1) | |

| Surgery (primary tumour) | 53 (61.6) | |

| Chemotherapy in curative setting | 39 (45.3) | |

| Number of metastatic locations Median (amplitude) |

1,62 (1-4) |

|

| Metastatic locations Liver Lung Peritoneal Lymph nodes Local recurrence Others |

58 (67.4) 33 (38.4) 20 (23.3) 16 (18.6) 6 (7.0) 6 (7.0) |

|

| NGS setting Before palliative treatment Previously treated mCRC |

63 (73.3) 23 (26.7) |

|

| NGS panel Focused assay Comprehensive assay |

65 (75.6) 21 (24.4) |

|

| Origin of biological material Primary tumour Metastasis |

59 (74.4) 27 (25.6) |

|

| Collection of biological material Surgical sample Biopsy |

49 (57.0) 37 (43.0) |

|

| ECOG PS: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; MMRp: mismatch repair proteins proficiency (tissue). |

||

| Variant/profile | N=86 (%) | ESCAT tier |

| RAS/BRAF wild-type | 29 (33.7) | ND |

| KRAS G12C | 4 (4.7) | IA |

| TMB high (>10 mut/mb) | 4 (4.7) | ICa |

| BRAF V600E | 2 (2.3) | IA |

| HER2 amplification | 1 (1.2) | IIB |

| a – ESCAT scoring for tumour-agnostic genomic alteration; ND – not defined. | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).