Submitted:

25 March 2025

Posted:

26 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

| Molecular technology | Group or disease of interest | Sample type/info | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| LAMP | Streptococcus agalactiae, koi herpes virus, Iridovirus, and Aeromonas hydrophila | Cultured ornamental fishes | (Chang et al., 2013) |

| Vibrio parahaemolyticus | Seafood samples | (Anupama et al., 2020) | |

| Vibrio vulnificus | Various sample types | (Z. Tian et al., 2022) | |

| Decapod iridescent virus 1 (DIV1), White spot syndrome virus (WSSV), and Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei (EHP) | Clinical infection experiment using shrimp | (Hu et al., 2023) | |

| Lyophilized qPCR | Gyrodactylus salaris and Aphanomyces astaci | Environmental water samples | (Rieder et al., 2022) |

| Metabarcoding and Metagenomics | Microbial communities | Recirculating aquaculture systems | (Rieder et al., 2023) |

| Metabarcoding | Nitrifying biofilms | Freshwater, brackish, and marine biofilters | (Hüpeden et al., 2020) |

| Microbial communities | Sole (Solea senegalensis) | (Almeida et al., 2021) | |

| Skin and gill microbiomes | Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) | (Lorgen-Ritchie et al., 2022) | |

| Gut, skin, and microbiomes | Sea bass (Dicentrachus labrax) | (Nikouli et al., 2021; Meziti et al., 2024) | |

| Gut, skin, and microbiomes | Sea bream (Sparus aurata) | (Nikouli et al., 2018, 2021) | |

| Metatranscriptomics | Viruses | Multiple sources | (Mordecai et al., 2020) |

| Microbial communities | Mussels | (Rey-Campos et al., 2022) | |

| CRISPR-Cas | See Table 2 for an exhaustive list of CRISPR-Cas studies | ||

| CAS Protein | Amplification method | Detection Method | Target | Limit of Detection | Time, min | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas12a | RPA | F | Salmo salar, Salmo trutta, Salvenius alpinus | 10−5 ng/µL | <150 | Williams et al., 2019, 2021, 2022 |

| F, C | Vibrio spp. | 20 copies/μL | 120 | C. Li et al., 2022 | ||

| F, LF | Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei | 50 copies/reaction | 60 | Kanitchinda et al., 2020 | ||

| F | Vibrio spp. | 100 copies/reaction | 90 | P. Wang, Guo et al., 2023 | ||

| F, LF | Clonorchis sinensis | 1 copy/μL | 60 | Huang et al., 2023 | ||

| F | Vibrio vulnificus | 4 copies/reaction | 40-60 | X. Zhang et al., 2024 | ||

| F | Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei | 10 copies/reaction | 40 | Wang et al., 2022 | ||

| F | Renibacterium salmoninarum | 10 copies/µL | 60 | D’Agnese et al., 2023 | ||

| F, LF | Megalocytivirus | 40 copies/reaction | 60 | Sukonta et al., 2022 | ||

| F | White Spot Syndrome Virus | 200 copies/reaction | <60 | Chaijarasphong et al., 2019 | ||

| F | WSSV | 10 copies/reaction | 60 | P. Wang, Yang et al., 2023 | ||

| F | Mandarin fish ranavirus (MFR), Infectious spleen and kidney necrosis virus (ISKNV) | 1 copy/μL (MFR), 0.1 copy/μL (ISKNV) |

45-60 | Lu et al., 2024 | ||

| RAA | F | Vibrio vulnificus | 2 copies/reaction | 40 | Xiao et al., 2021 | |

| F | Cyprinid herpesvirus 2 | 10 copies/reaction | 60 | Hou et al., 2025 | ||

| dRAA | F | Aeromonas hydrophila | 2 copies/reaction | 45 | Lin et al., 2022 | |

| CE-RAA | F | Vibrio parahemolyticus | 67 CFU/ml in pure cultures, 73 CFU/g in shrimp tissues |

N/A | Lv et al., 2022 | |

| RT-RAA | F | Nervous necrosis virus | 0.5 copies/μL | 30 | Gao et al., 2018 | |

| RT-RPA | F, LF | Infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus | 9.5 copies/μL | 60 | Rong et al., 2024 | |

| F, LF | Hirame novirhabdovirus | 8.7 copies/μL | 60 | Tang et al., 2024 | ||

| F, LF | Tilapia tilapinevirus | 200 copies/reaction | <60 | Sukonta et al., 2022 | ||

| F, LF | Yellow head virus | 100 fg RNA | 90 | Aiamsa-At et al., 2023 | ||

| Cas12b | LAMP (with/without reverse transcriptase) |

F | White Spot Syndrome Virus, Taura Syndrome Virus (TSV) |

100 copies/reaction (WSSV), 200 copies/reaction (TSV) |

30 | Major et al., 2023 |

| Cas13a | RPA | F, LF | Delta smelt (Hypomesus transpacificus), Longfin smelt (Spirinchus thaleichthys), Wakasagi (Hypomesus nipponensis) | 300 copies/reaction | <60 | Baerwald et al., 2020 |

| LF | Vibrio alginolyticus | 10 copies/μL | 50 | Y. Wang et al., 2023 | ||

| F, LF | Yersinia ruckeri | RNA: 2 aM in bacterial lysates of planktonic and biofilm cultures DNA: 1 ng/reaction in biofilm samples |

70 | Calderon et al., 2024 | ||

| F, C | White Spot Syndrome Virus | 1.06 copies/reaction | 60 | Sullivan et al., 2019 | ||

| RAA | F, LF | Largemouth bass ranavirus | 31 copies/ul | 60 | Guang et al., 2024 | |

| Cas12a and Cas13a | RPA | F | White Spot Syndrome Virus, Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei | 200 copies/reaction (WSSV), 20 copies/reaction (EHP) |

<60 | Kanitchinda et al., 2024 |

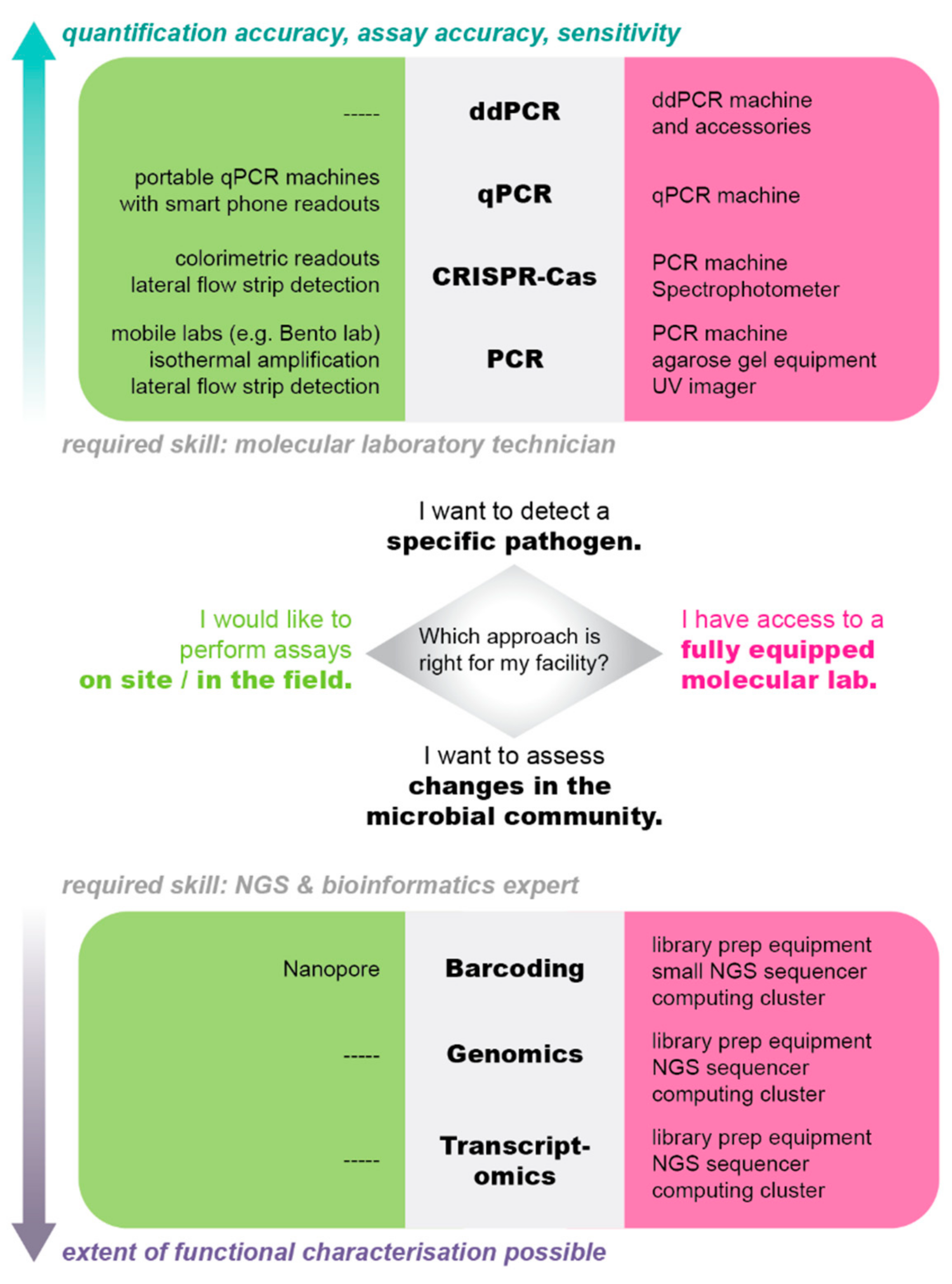

Independence from Controlled Environments

Lyophilization

Isothermal Amplification

RPA

Colorimetric Readouts

Moving away from Fish Handling

Environmental DNA and RNA

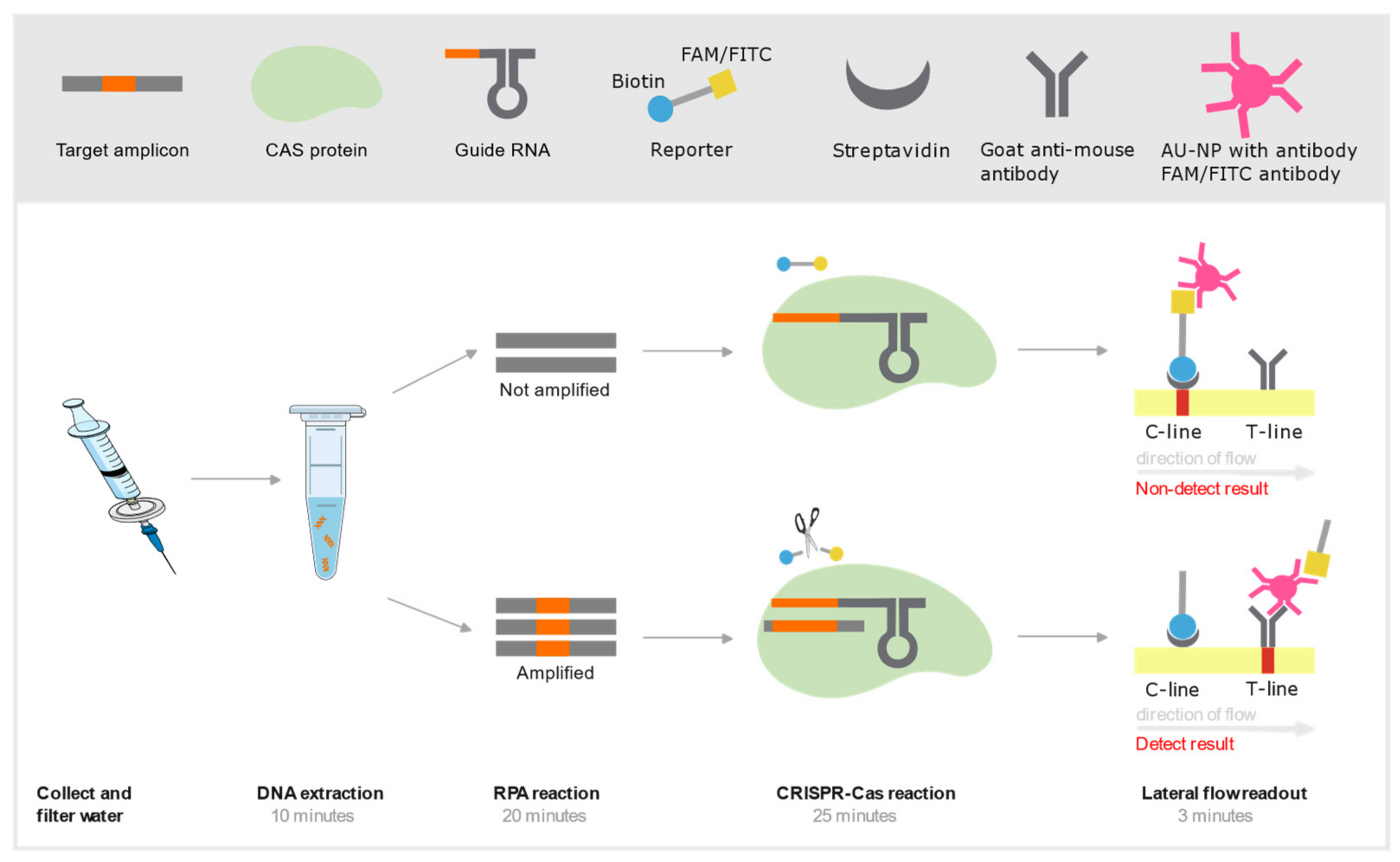

Transfer of CRISPR Technology to Aquaculture

Transfer of Microbial Community Ecology to Aquaculture

Conclusion

Author Contributions

Ethics and Integrity Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Aiamsa-At, P., Nonthakaew, N., Phiwsaiya, K., Senapin, S., & Chaijarasphong, T. (2023). CRISPR-based, genotype-specific detection of yellow head virus genotype 1 with fluorescent, lateral flow and DNAzyme-assisted colorimetric readouts. Aquaculture, 574, 739696. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D. B., Magalhães, C., Sousa, Z., Borges, M. T., Silva, E., Blanquet, I., & Mucha, A. P. (2021). Microbial community dynamics in a hatchery recirculating aquaculture system (RAS) of sole (Solea senegalensis). Aquaculture, 539. [CrossRef]

- Anupama, K. P., Nayak, A., Karunasagar, I., & Maiti, B. (2020). Rapid visual detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in seafood samples by loop-mediated isothermal amplification with hydroxynaphthol blue dye. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 36(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Bakke, I., Åm, A. L., Kolarevic, J., Ytrestøyl, T., Vadstein, O., Attramadal, K. J. K., & Terjesen, B. F. (2017). Microbial community dynamics in semi-commercial RAS for production of Atlantic salmon post-smolts at different salinities. Aquacultural Engineering, 78, 42–49. [CrossRef]

- Bass, D., Christison, K. W., Stentiford, G. D., Cook, L. S. J., & Hartikainen, H. (2023). Environmental DNA/RNA for pathogen and parasite detection, surveillance, and ecology. Trends in Parasitology, 39(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Bastos Gomes, G., Hutson, K. S., Domingos, J. A., Chung, C., Hayward, S., Miller, T. L., & Jerry, D. R. (2017). Use of environmental DNA (eDNA) and water quality data to predict protozoan parasites outbreaks in fish farms. Aquaculture, 479, 467–473. [CrossRef]

- Bentzon-Tilia, M., Sonnenschein, E. C., & Gram, L. (2016). Monitoring and managing microbes in aquaculture – Towards a sustainable industry. Microbial Biotechnology, 9(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Bloemen, B., Gand, M., Vanneste, K., Marchal, K., Roosens, N. H. C., & De Keersmaecker, S. C. J. (2023). Development of a portable on-site applicable metagenomic data generation workflow for enhanced pathogen and antimicrobial resistance surveillance. Scientific Reports, 13(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Bohara, K., Yadav, A. K., & Joshi, P. (2022). Detection of Fish Pathogens in Freshwater Aquaculture Using eDNA Methods. Diversity, 14(12), Article 12. [CrossRef]

- Cain, K. (2022). The many challenges of disease management in aquaculture. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, 53(6), 1080–1083. [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-H., Yang, S.-Y., Wang, C.-H., Tsai, M.-A., Wang, P.-C., Chen, T.-Y., Chen, S.-C., & Lee, G.-B. (2013). Rapid isolation and detection of aquaculture pathogens in an integrated microfluidic system using loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical, 180, 96–106. [CrossRef]

- Das, D., Lin, C.-W., & Chuang, H.-S. (2022). LAMP-Based Point-of-Care Biosensors for Rapid Pathogen Detection. Biosensors, 12(12), 1068. [CrossRef]

- De Schryver, P., & Vadstein, O. (2014). Ecological theory as a foundation to control pathogenic invasion in aquaculture. The ISME Journal, 8(12), Article 12. [CrossRef]

- Delamare-Deboutteville, J. (2021). Uncover aquaculture pathogens identity using Nanopore MinION.pdf. Available online: https://digitalarchive.worldfishcenter.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.12348/4931/eb0411d2c9e634acfae22ee2db9e7391.pdf?sequence2=.

- Dong, L., Meng, Y., Sui, Z., Wang, J., Wu, L., & Fu, B. (2015). Comparison of four digital PCR platforms for accurate quantification of DNA copy number of a certified plasmid DNA reference material. Scientific Reports, 5(1), 13174. 5, 1, 13174. [CrossRef]

- Ellison, A. R., Uren Webster, T. M., Rey, O., Garcia de Leaniz, C., Consuegra, S., Orozco-terWengel, P., & Cable, J. (2018). Transcriptomic response to parasite infection in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) depends on rearing density. BMC Genomics, 19(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Ellison, A. R., Uren Webster, T. M., Rodriguez-Barreto, D., de Leaniz, C. G., Consuegra, S., Orozco-terWengel, P., & Cable, J. (2020). Comparative transcriptomics reveal conserved impacts of rearing density on immune response of two important aquaculture species. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 104, 192–201. [CrossRef]

- El-Saadony, M. T., Alagawany, M., Patra, A. K., Kar, I., Tiwari, R., Dawood, M. A. O., Dhama, K., & Abdel-Latif, H. M. R. (2021). The functionality of probiotics in aquaculture: An overview. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 117, 36–52. [CrossRef]

- FAO. (2020). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020. In brief. FAO. [CrossRef]

- FAO. (2022). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. FAO. [CrossRef]

- Fossøy, F., Brandsegg, H., Sivertsgård, R., Pettersen, O., Sandercock, B. K., Solem, Ø., Hindar, K., & Mo, T. A. (2020). Monitoring presence and abundance of two gyrodactylid ectoparasites and their salmonid hosts using environmental DNA. Environmental DNA, 2(1), 53–62. [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.-W., Horng, J.-L., & Chou, M.-Y. (2022). Fish Behavior as a Neural Proxy to Reveal Physiological States. Frontiers in Physiology, 13, 937432. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M. D., Matejusova, I., Nguyen, L., Ruane, N. M., Falk, K., & Macqueen, D. J. (2018). Nanopore sequencing for rapid diagnostics of salmonid RNA viruses. Scientific Reports, 8(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F., Jiang, J.-Z., Wang, J.-Y., & Wei, H.-Y. (2018). Real-time isothermal detection of Abalone herpes-like virus and red-spotted grouper nervous necrosis virus using recombinase polymerase amplification. Journal of Virological Methods, 251, 92–98. [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y., Tan, K., Liu, L., Sun, X. X., Zhao, B., & Wang, J. (2019). Development and evaluation of a rapid and sensitive RPA assay for specific detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in seafood. BMC Microbiology, 19(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, M. C., & Spoto, G. (2017). Integration of isothermal amplification methods in microfluidic devices: Recent advances. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 90, 174–186. [CrossRef]

- Gorgannezhad, L., Stratton, H., & Nguyen, N.-T. (2019). Microfluidic-Based Nucleic Acid Amplification Systems in Microbiology. Micromachines, 10(6), Article 6. [CrossRef]

- Guptha Yedire, S., Khan, H., AbdelFatah, T., Moakhar, R. S., & Mahshid, S. (2023). Microfluidic-based colorimetric nucleic acid detection of pathogens. Sensors & Diagnostics. [CrossRef]

- Hierweger, M. M., Koch, M. C., Rupp, M., Maes, P., Paola, N. D., Bruggmann, R., Kuhn, J. H., Schmidt-Posthaus, H., & Seuberlich, T. (2017). Novel Filoviruses, Hantavirus, and Rhabdovirus in Freshwater Fish, Switzerland, 2017. Emerging Infectious Diseases. [CrossRef]

- Hook, S. E., White, C., & Ross, D. J. (2021). A metatranscriptomic analysis of changing dynamics in the plankton communities adjacent to aquaculture leases in southern Tasmania, Australia. Marine Genomics, 59, 100858. [CrossRef]

- Hu, K., Li, Y., Wang, F., Liu, J., Li, Y., Zhao, Q., Zheng, X., Zhu, N., Yu, X., Fang, S., & Huang, J. (2023). A loop-mediated isothermal amplification-based microfluidic chip for triplex detection of shrimp pathogens. Journal of Fish Diseases, 46(2), 137–146. [CrossRef]

- Hubrecht, R. C., & Carter, E. (2019). The 3Rs and Humane Experimental Technique: Implementing Change. Animals : An Open Access Journal from MDPI, 9(10), 754. [CrossRef]

- Huntingford, F., Rey, S., & Quaggiotto, M.-M. (2020). Behavioural fever, fish welfare and what farmers and fishers know. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 231, 105090. [CrossRef]

- Hüpeden, J., Wemheuer, B., Indenbirken, D., Schulz, C., & Spieck, E. (2020). Taxonomic and functional profiling of nitrifying biofilms in freshwater, brackish and marine RAS biofilters. Aquacultural Engineering, 90, 102094. [CrossRef]

- Jaroenram, W., & Owens, L. (2014). Recombinase polymerase amplification combined with a lateral flow dipstick for discriminating between infectious Penaeus stylirostris densovirus and virus-related sequences in shrimp genome. Journal of Virological Methods, 208, 144–151. [CrossRef]

- Jin, R., Zhai, L., Zhu, Q., Feng, J., & Pan, X. (2020). Naked-eyes detection of Largemouth bass ranavirus in clinical fish samples using gold nanoparticles as colorimetric sensor. Aquaculture, 528, 735554. [CrossRef]

- Kanitchinda, S., Srisala, J., Suebsing, R., Prachumwat, A., & Chaijarasphong, T. (2020). CRISPR-Cas fluorescent cleavage assay coupled with recombinase polymerase amplification for sensitive and specific detection of Enterocytozoon hepatopenaei. Biotechnology Reports, 27, e00485. [CrossRef]

- Kant, K., Shahbazi, M.-A., Dave, V. P., Ngo, T. A., Chidambara, V. A., Than, L. Q., Bang, D. D., & Wolff, A. (2018). Microfluidic devices for sample preparation and rapid detection of foodborne pathogens. Biotechnology Advances, 36(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Khan, R., Petersen, F. C., & Shekhar, S. (2019). Commensal Bacteria: An Emerging Player in Defense Against Respiratory Pathogens. Frontiers in Immunology, 10. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01203.

- Kulkarni, M. B., & Goel, S. (2020). Advances in continuous-flow based microfluidic PCR devices—A review. Engineering Research Express, 2(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. D., Pedroso, A. A., & Maurer, J. J. (2023). Bacterial composition of a competitive exclusion product and its correlation with product efficacy at reducing Salmonella in poultry. Frontiers in Physiology, 13. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphys.2022.1043383.

- Li, C., Lin, N., Feng, Z., Lin, M., Guan, B., Chen, K., Liang, W., Wang, Q., Li, M., You, Y., & Chen, Q. (2022). CRISPR/Cas12a Based Rapid Molecular Detection of Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease in Shrimp. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2021.819681.

- Li, H., Zhang, L., Yu, Y., Ai, T., Zhang, Y., & Su, J. (2022). Rapid detection of Edwardsiella ictaluri in yellow catfish (Pelteobagrus fulvidraco) by real-time RPA and RPA-LFD. Aquaculture, 552, 737976. [CrossRef]

- Liu, R., Han, G., Li, Z., Cun, S., Hao, B., Zhang, J., & Liu, X. (2022). Bacteriophage therapy in aquaculture: Current status and future challenges. Folia Microbiologica, 67(4), 573–590. [CrossRef]

- Lorgen-Ritchie, M., Clarkson, M., Chalmers, L., Taylor, J. F., Migaud, H., & Martin, S. A. M. (2022). Temporal changes in skin and gill microbiomes of Atlantic salmon in a recirculating aquaculture system – Why do they matter? Aquaculture, 558, 738352. [CrossRef]

- Mabrok, M., Elayaraja, S., Chokmangmeepisarn, P., Jaroenram, W., Arunrut, N., Kiatpathomchai, W., Debnath, P. P., Delamare-Deboutteville, J., Mohan, C. V., Fawzy, A., & Rodkhum, C. (2021). Rapid visualization in the specific detection of Flavobacterium columnare, a causative agent of freshwater columnaris using a novel recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) combined with lateral flow dipstick (LFD) assay. Aquaculture, 531, 735780. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Porchas, M., & Vargas-Albores, F. (2017). Microbial metagenomics in aquaculture: A potential tool for a deeper insight into the activity. Reviews in Aquaculture, 9(1), 42–56. [CrossRef]

- Mérou, N., Lecadet, C., Pouvreau, S., & Arzul, I. (2020). An eDNA/eRNA-based approach to investigate the life cycle of non-cultivable shellfish micro-parasites: The case of Bonamia ostreae, a parasite of the European flat oyster Ostrea edulis. Microbial Biotechnology, 13(6), 1807–1818. [CrossRef]

- Meziti, A., Nikouli, E., Papaharisis, L., Ar. Kormas, K., & Mente, E. (2024). The response of gut and fecal bacterial communities of the European sea bass (Dicentrachus labrax) fed a low fish-plant meal and yeast protein supplementation diet. Sustainable Microbiology, 1(1), qvae005. [CrossRef]

- Mordecai, G. J., Di Cicco, E., Günther, O. P., Schulze, A. D., Kaukinen, K. H., Li, S., Tabata, A., Ming, T. J., Ferguson, H. W., Suttle, C. A., & Miller, K. M. (2020). Discovery and surveillance of viruses from salmon in British Columbia using viral immune-response biomarkers, metatranscriptomics, and high-throughput RT-PCR. Virus Evolution, 7(1), veaa069. [CrossRef]

- Morsy, M. K., Zór, K., Kostesha, N., Alstrøm, T. S., Heiskanen, A., El-Tanahi, H., Sharoba, A., Papkovsky, D., Larsen, J., Khalaf, H., Jakobsen, M. H., & Emnéus, J. (2016). Development and validation of a colorimetric sensor array for fish spoilage monitoring. Food Control, 60, 346–352. [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R. L., Hardy, R. W., Buschmann, A. H., Bush, S. R., Cao, L., Klinger, D. H., Little, D. C., Lubchenco, J., Shumway, S. E., & Troell, M. (2021). A 20-year retrospective review of global aquaculture. Nature, 591(7851), Article 7851. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P. L., Sudheesh, P. S., Thomas, A. C., Sinnesael, M., Haman, K., & Cain, K. D. (2018). Rapid Detection and Monitoring of Flavobacterium psychrophilum in Water by Using a Handheld, Field-Portable Quantitative PCR System. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health, 30(4), 302–311. [CrossRef]

- Nikouli, E., Meziti, A., Antonopoulou, E., Mente, E., & Kormas, K. A. (2018). Gut Bacterial Communities in Geographically Distant Populations of Farmed Sea Bream (Sparus aurata) and Sea Bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Microorganisms, 6(3), 92. [CrossRef]

- Nikouli, E., Meziti, A., Smeti, E., Antonopoulou, E., Mente, E., & Kormas, K. A. (2021). Gut Microbiota of Five Sympatrically Farmed Marine Fish Species in the Aegean Sea. Microbial Ecology, 81(2), 460–470. [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, T., & Botelho, A. (2021). Metagenomics and other omics approaches to bacterial communities and antimicrobial resistance assessment in aquacultures. Antibiotics, 10(7). [CrossRef]

- Notomi, T., Okayama, H., Masubuchi, H., Yonekawa, T., Watanabe, K., Amino, N., & Hase, T. (2000). Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Research, 28(12), Article 12. [CrossRef]

- Novoslavskij, A., Terentjeva, M., Eizenberga, I., Valciņa, O., Bartkevičs, V., & Bērziņš, A. (2016). Major foodborne pathogens in fish and fish products: A review. Annals of Microbiology, 66(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Pavšič, J., Žel, J., & Milavec, M. (2016). Assessment of the real-time PCR and different digital PCR platforms for DNA quantification. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry, 408, 107–121. [CrossRef]

- Peters, L., Spatharis, S., Dario, M. A., Dwyer, T., Roca, I. J. T., Kintner, A., Kanstad-Hanssen, Ø., Llewellyn, M. S., & Praebel, K. (2018). Environmental DNA: A new low-cost monitoring tool for pathogens in salmonid aquaculture. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9(DEC), 3009. [CrossRef]

- Phelps, M. (2019). Increasing eDNA capabilities with CRISPR technology for real-time monitoring of ecosystem biodiversity. Molecular Ecology Resources, 19(5), 1103–1105. [CrossRef]

- Prescott, M. A., Reed, A. N., Jin, L., & Pastey, M. K. (2016). Rapid Detection of Cyprinid Herpesvirus 3 in Latently Infected Koi by Recombinase Polymerase Amplification. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health, 28(3), Article 3. [CrossRef]

- Quan, P.-L., Sauzade, M., & Brouzes, E. (2018). dPCR: A Technology Review. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 18(4), 1271. [CrossRef]

- Ramond, P., Galand, P. E., & Logares, R. (2025). Microbial functional diversity and redundancy: Moving forward. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 49, fuae031. [CrossRef]

- Rey-Campos, M., Ríos-Castro, R., Gallardo-Escárate, C., Novoa, B., & Figueras, A. (2022). Exploring the Potential of Metatranscriptomics to Describe Microbial Communities and Their Effects in Molluscs. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(24), 16029. [CrossRef]

- Rieder, J., Kapopoulou, A., Bank, C., & Adrian-Kalchhauser, I. (2023). Metagenomics and metabarcoding experimental choices and their impact on microbial community characterization in freshwater recirculating aquaculture systems. Environmental Microbiome, 18(1), 8. [CrossRef]

- Rieder, J., Martin-Sanchez, P. M., Osman, O. A., Adrian-Kalchhauser, I., & Eiler, A. (2022). Detecting aquatic pathogens with field-compatible dried qPCR assays. Journal of Microbiological Methods, 202, 106594. [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Tirado, P., Pedersen, P. B., Vadstein, O., & Pedersen, L.-F. (2018). Changes in microbial water quality in RAS following altered feed loading. Aquacultural Engineering, 81, 80–88. [CrossRef]

- Rupp, M., Pilo, P., Müller, B., Knüsel, R., von Siebenthal, B., Frey, J., Sindilariu, P.-D., & Schmidt-Posthaus, H. (2019). Systemic infection in European perch with thermoadapted virulent Aeromonas salmonicida (Perca fluviatilis). Journal of Fish Diseases, 42(5), Article 5. [CrossRef]

- Samacoits, A., Nimsamer, P., Mayuramart, O., Chantaravisoot, N., Sitthi-amorn, P., Nakhakes, C., Luangkamchorn, L., Tongcham, P., Zahm, U., Suphanpayak, S., Padungwattanachoke, N., Leelarthaphin, N., Huayhongthong, H., Pisitkun, T., Payungporn, S., & Hannanta-anan, P. (2021). Machine Learning-Driven and Smartphone-Based Fluorescence Detection for CRISPR Diagnostic of SARS-CoV-2. ACS Omega, 6(4), 2727–2733. [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, J. L., Rachinas-Lopes, P., & Arechavala-Lopez, P. (2022). Finding the “golden stocking density”: A balance between fish welfare and farmers’ perspectives. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 9. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2022.930221.

- Seuberlich, T., Kuhn, J. H., & Schmidt-Posthaus, H. (2023). Near-Complete Genome Sequence of Lötschberg Virus (Mononegavirales: Filoviridae) Identified in European Perch (Perca fluviatilis Linnaeus, 1758). Microbiology Resource Announcements, 12(4), e00028-23. [CrossRef]

- Shahin, K., Gustavo Ramirez-Paredes, J., Harold, G., Lopez-Jimena, B., Adams, A., & Weidmann, M. (2018). Development of a recombinase polymerase amplification assay for rapid detection of Francisella noatunensis subsp. Orientalis. PloS One, 13(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M. (2019). Behavioural responses in effect to chemical stress in fish: A review. International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies, 7(1), 1–5.

- Sieber, N., Hartikainen, H., & Vorburger, C. (2020). Validation of an eDNA-based method for the detection of wildlife pathogens in water. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 141, 171–184. [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, L. U. (2009). Pain perception in fish: Indicators and endpoints. ILAR Journal, 50(4), 338–342. [CrossRef]

- Soliman, H., Kumar, G., & El-Matbouli, M. (2018). Recombinase polymerase amplification assay combined with a lateral flow dipstick for rapid detection of Tetracapsuloides bryosalmonae, the causative agent of proliferative kidney disease in salmonids. Parasites & Vectors, 11(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Song, X., Coulter, F. J., Yang, M., Smith, J. L., Tafesse, F. G., Messer, W. B., & Reif, J. H. (2022). A lyophilized colorimetric RT-LAMP test kit for rapid, low-cost, at-home molecular testing of SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens. Scientific Reports, 12(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Stentiford, G. D., Peeler, E. J., Tyler, C. R., Bickley, L. K., Holt, C. C., Bass, D., Turner, A. D., Baker-Austin, C., Ellis, T., Lowther, J. A., Posen, P. E., Bateman, K. S., Verner-Jeffreys, D. W., van Aerle, R., Stone, D. M., Paley, R., Trent, A., Katsiadaki, I., Higman, W. A., … Hartnell, R. E. (2022). A seafood risk tool for assessing and mitigating chemical and pathogen hazards in the aquaculture supply chain. Nature Food, 3(2), Article 2. [CrossRef]

- Suebsing, R., Kampeera, J., Sirithammajak, S., Withyachumnarnkul, B., Turner, W., & Kiatpathomchai, W. (2015). Colorimetric Method of Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification with the Pre-Addition of Calcein for Detecting Flavobacterium columnare and its Assessment in Tilapia Farms. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health, 27(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Sukonta, T., Senapin, S., Meemetta, W., & Chaijarasphong, T. (2022). CRISPR-based platform for rapid, sensitive and field-deployable detection of scale drop disease virus in Asian sea bass (Lates calcarifer). Journal of Fish Diseases, 45(1), 107–120. [CrossRef]

- Sukonta, T., Senapin, S., Taengphu, S., Hannanta-anan, P., Kitthamarat, M., Aiamsa-at, P., & Chaijarasphong, T. (2022). An RT-RPA-Cas12a platform for rapid and sensitive detection of tilapia lake virus. Aquaculture, 560, 738538. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, T. J., Dhar, A. K., Cruz-Flores, R., & Bodnar, A. G. (2019). Rapid, CRISPR-Based, Field-Deployable Detection Of White Spot Syndrome Virus In Shrimp. Scientific Reports, 9(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, B. J. G., Finke, J. F., Saunders, R., Warne, S., Schulze, A. D., Strohm, J. H. T., Chan, A. M., Suttle, C. A., & Miller, K. M. (2022). Metatranscriptomics reveals a shift in microbial community composition and function during summer months in a coastal marine environment. Environmental DNA. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., Liu, T., Liu, C., Xu, Q., & Liu, Q. (2022). Pathogen detection strategy based on CRISPR. Microchemical Journal, 174, 107036. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z., Yang, L., Qi, X., Zheng, Q., Shang, D., & Cao, J. (2022). Visual LAMP method for the detection of Vibrio vulnificus in aquatic products and environmental water. BMC Microbiology, 22(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2016). The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

- Urban, L., Holzer, A., Baronas, J. J., Hall, M. B., Braeuninger-Weimer, P., Scherm, M. J., Kunz, D. J., Perera, S. N., Martin-Herranz, D. E., Tipper, E. T., Salter, S. J., & Stammnitz, M. R. (2021). Freshwater monitoring by nanopore sequencing. eLife, 10, e61504. [CrossRef]

- Verschuere, L., Rombaut, G., Sorgeloos, P., & Verstraete, W. (2000). Probiotic Bacteria as Biological Control Agents in Aquaculture. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 64(4), Article 4.

- Wang, P., Guo, B., Zhang, X., Wang, Y., Yang, G., Shen, H., Gao, S., & Zhang, L. (2023). One-Pot Molecular Diagnosis of Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease by Recombinase Polymerase Amplification and CRISPR/Cas12a with Specially Designed crRNA. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 71(16), 6490–6498. [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. A., de Eyto, E., Caestecker, S., Regan, F., & Parle-McDermott, A. (2022). Development and field validation of RPA-CRISPR-Cas environmental DNA assays for the detection of brown trout (Salmo trutta) and Arctic char (Salvelinus alpinus). Environmental DNA. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2014). Reducing Disease Risk in Aquaculture. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/18936.

- Wright, A., Li, X., Yang, X., Soto, E., & Gross, J. (2023). Disease prevention and mitigation in US finfish aquaculture: A review of current approaches and new strategies. Reviews in Aquaculture, n/a(n/a), Article n/a. [CrossRef]

- Xia, X., Yu, Y., Hu, L., Weidmann, M., Pan, Y., Yan, S., & Wang, Y. (2015). Rapid detection of infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus (IHHNV) by real-time, isothermal recombinase polymerase amplification assay. Archives of Virology, 160(4), Article 4. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X., Lin, Z., Huang, X., Lu, J., Zhou, Y., Zheng, L., & Lou, Y. (2021). Rapid and Sensitive Detection of Vibrio vulnificus Using CRISPR/Cas12a Combined With a Recombinase-Aided Amplification Assay. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12. [CrossRef]

- Xue, S., Xu, W., Wei, J., & Sun, J. (2017). Impact of environmental bacterial communities on fish health in marine recirculating aquaculture systems. Veterinary Microbiology, 203, 34–39. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W., Zheng, Z., Lu, K., Zheng, C., Du, Y., Wang, J., & Zhu, J. (2020). Manipulating the phytoplankton community has the potential to create a stable bacterioplankton community in a shrimp rearing environment. Aquaculture, 520, 734789. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Cao, L., Brodsky, J., Gablech, I., Xu, F., Li, Z., Korabecna, M., & Neuzil, P. (2024). Quantitative or digital PCR? A comparative analysis for choosing the optimal one for biosensing applications. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry, 174, 117676. [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).