Introduction

Sphingolipids (SLs) are a family of lipids which contain a fatty amino alcohol base called sphingosine. The

de novo biosynthesis of SLs is mediated by the enzyme serine palmitoyl transferase, which facilitates the condensation of serine and palmitoyl-CoA generating the labile intermediate 3-keto-sphinganine (3KS). 3KS is rapidly converted to dihydrosphingosine (dhSph) via 3-ketosphinganine reductase. Typically, dhSph is amino-acylated with a varying chain length fatty acid to form dihydroceramide (dhCer) by one of six ceramide synthases (CerS). The final step of

de novo synthesis occurs when one of two dihydroceramide desaturases adds a double bond between C4 and C5 in the sphingoid base to generate ceramide (Cer). To generate sphingosine (Sph), the molecule for which the family is named, the amino-acylated fatty acid is cleaved by ceramidase. Sph can then either be converted back to Cer by CerS or be phosphorylated by one of two sphingosine kinases (SphK) to form the bioactive lysophospholipid S1P [

1]. The fate of S1P is often tied to the SphK isoform which phosphorylates it [

2].

These two enzymes share the same biochemical function, yet have differential tissue expression patterns and subcellular localization which drives their biological effects. [

3] Generally, SphK1 can be found predominantly in the cytoplasm or associated with the cytoskeleton, endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi apparatus, or plasma membrane while SphK2 is mainly expressed in the nucleus and ER. [

4,

5] When examining inside-out signaling by S1P the main isoform responsible for this affect is SphK1, which is rapidly recruited to the plasma membrane during receptor mediated endocytosis. [

6] Inhibiting the activity of SphK1 results in the accumulation of dilated late endosomes and eventual cellular death in a TP53 dependent manner highlighting SphK1’s regulatory role in membrane processing after signaling events and other endocytic processes. [

6,

7] Many of the biological effects of S1P can be attributed to autocrine and paracrine signaling through the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors (S1PRs), which belong to the G Protein-Coupled Receptor (GPCR) family and are also referred to as Endothelial Differentiation Genes (EDG). There are five isotypes of S1PRs: S1PR1 (EDG-1), S1PR2 (EDG-5), S1PR3 (EDG-3), S1PR4 (EDG-6), and S1PR5 (EDG-8) [

8]. While S1P signaling plays a vital role in the cardiovascular, immune, gastrointestinal, and integumentary systems in this work we will examine the expression and function of the S1PRs in the central nervous system, discuss their role in maintaining CNS barrier function, and discuss current progress in the development of small molecule therapeutics to target their function.

G Protein Coupled Receptors

The G protein coupled receptor (GPCR) family is the largest receptor family in the human genome, with roughly 800 identified members [

9]. GPCRs respond to a variety of stimuli including neurotransmitters, hormones, bioactive lipids, and even photons [

10,

11,

12,

13]. As a result of this diversity GPCRs are involved heavily in the regulation of physiology and development of pathophysiology. All GPCRs contain seven transmembrane domains, an extracellular N-terminal ligand recognition domain, and a triple looped C-terminal tail which regulates interactions with transducer proteins and effectors [

9,

14]. The most common of these transducers are the heterotrimeric G-proteins, which are composed of a complex of Gα, Gβ, and Gγ protein subunits. Binding of a ligand to these receptors activates the receptors intrinsic guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) activity which exchanges guanine diphosphate (GDP) bound to the Gα subunit and replaces it with guanine triphosphate (GTP) causing the disassociation of the Gα subunit from the remaining Gβ, and Gγ complex (hereafter referred to as Gβγ). Once dissociated Gα and Gβγ transduce their signals through separate effector pathways until the GTP bound to the Gα subunit is hydrolyzed to GDP via intrinsic activity on the subunit itself or via regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS) proteins [

15]. While diversity in the Gβγ complex, and the γ subunit specifically, have recently become a focus of interest this work will focus on differences in the Gα subunit family that associates with the S1PRs [

16].

Gα Protein Subunit Families

There are four main families of Gα subunits (Gαs, Gαi, Gαq/11, and Gα12/13), each of which transduce their signals through a variety of effectors. Two of the families (Gαs and Gαi) regulate the activity of adenylyl cyclase (AC) which converts adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to cyclic adenosine monophosphate. Gαs stimulates AC activity increasing the intracellular concentration of cAMP, which in turn activates cAMP-regulated proteins including protein kinase A (PKA) [

17]. Alternatively, Gαi inhibits AC activity, reducing cAMP activity and inhibiting PKA [

18]. The Gαq/11 family activate β-isoforms of phospholipase C (PLCβ), which generate inositol triphosphate (IP3) via the cleavage phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PtdIns(4,5)P2]. Increased intracellular levels of IP3 induce Calcium signaling through receptors on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) [

19]. The Gα12/13 subunit activates the Ras homolog family member A (RhoA), a small GTPase that works through a variety of target proteins in a cell type specific manner [

20]. This promiscuous nature of the GPCRs allow them to regulate a wide variety of responses based off the Gα subunits, combined with the ability of multiple S1PRs to differentially couple to individual Gα subunits (Table 1), allows a diverse and robust response to S1P in the CNS.

Oligodendrocytes

Oligodendrocytes (OLGs) are the cells responsible for the myelination of neurons in the CNS. S1P receptor expression in OLGs has been found to be dependent on the maturity of the cell. S1PR1 and S1PR5 are both expressed in oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs), and continue to be detected throughout maturation into mature myelinating OLGs [

21]. Interestingly, while OLG S1PR5 expression is higher than S1PR1 expression and S1PR5 deficient mature oligodendrocytes show an impaired response to S1P stimulation, S1PR5 knockout animals have no defects in myelination. [

22] It has been proposed that this is due to compensation by S1PR1, and recent work has found that S1PR1 and S1PR5 are structurally similar with conserved lipid binding domains [

23]. Further supporting this hypothesis is the ability of both S1PR1 and S1PR5 to couple with Gαi subunits (Table 1), and the observations that responses to S1P mediated through both S1PR1 and S1PR5 confer pro-survival benefits to both OPCs and mature myelinating OLGs respectively [

24]. In addition to these findings, a comprehensive study was conducted on S1PR2 inactivation using adult male C57Bl/6 mice to better understand the receptor’s role in Multiple Sclerosis. These findings showcased the pivotal physiological roles of the receptor by demonstrating that inactivation decreases macrophages and increases the number of oligodendrocytes in a lesion area, enhances the number of remyelinated axons, and increases Oligodendrocyte progenitor cell (OPC) differentiation with no effect on proliferation or recruitment [

25].

Neurons

Neurons express S1PR1, S1PR2, and S1PR3 (Table 1), and their activation by S1P can often act in opposition to each other to mediate neuronal function. This differential signaling is dependent on the Gα protein associated with the S1PR, as similar to S1PR1 both S1PR2 and S1PR3 are able to couple to Gαi. In mature neurons S1PR1 signaling provides protection against apoptosis via reductions in the expression of the pro-apoptotic proteins BAX and HRK through activation of the Akt pathway [

26]. S1PR1 also plays a role in sensory neurons, with evidence suggesting roughly half of small diameter sensory neurons expressing S1PR1, and that activation of these neurons via S1P increases their excitability [

27]. Additionally, S1PR1 activation stimulates Rac and contributes to neuronal elongation [

28], whereas S1PR2 and S1PR3 activation stimulate Rho and inhibit Rac decreasing cell motility [

29]. Interestingly, unlike S1PR2-5, mice deficient in S1PR1 expression suffer from impaired neural tube formation contributing to embryonic death suggesting a vital role for S1PR1 in neurodevelopment [

30]. Further strengthening the role of S1PR1 in neurodevelopment are findings showing S1PR1 expression as early as E15 in mice at sites of active neurogenesis [

31]. In neural progenitor cells (NPCs) inhibition of S1PR2, but not S1PR1, has been shown to inhibit migration to the site of ischemic injury demonstrating that S1PR1 mediated migration of neuronal cells is conserved into adulthood and that this affect is opposed by S1PR2 [

32]. Uniquely, S1PR2 can also be activated by interactions with the extracellular domain of NogoA and induce RhoA activity through the Gα13 subunit, although this interaction occurs outside the S1P binding domain [

33]. NogoA mediated activation of S1PR2 results in inhibition of neurite outgrowth, cell spreading, and reductions in synaptic plasticity similar to S1P mediated S1PR2 activation providing evidence that both ligands converge on the same signal transduction pathways [

33].

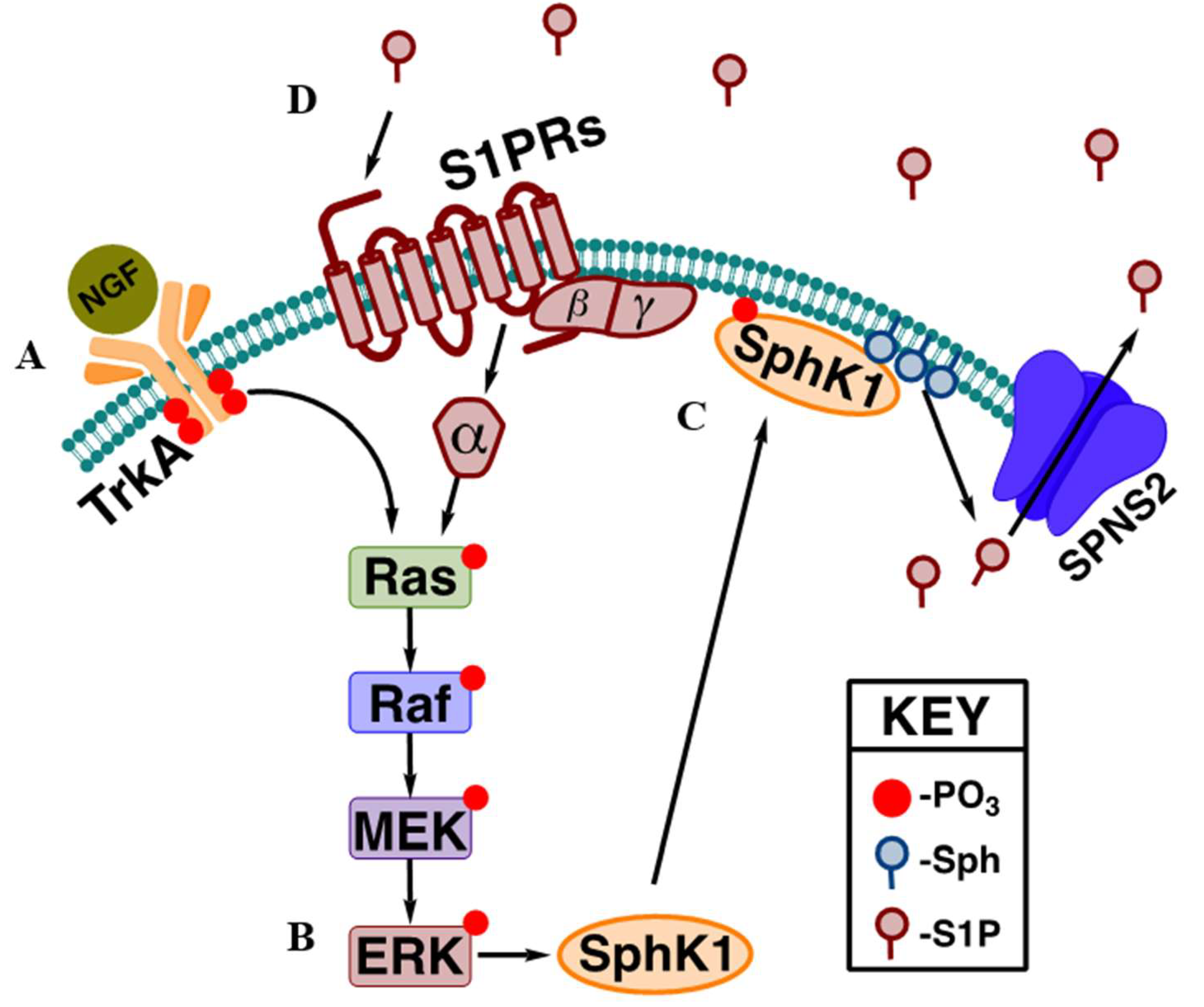

Similar to its role in ischemic injury repair, S1PR1 has also been shown to enhance neurogenesis and restore cognitive function in the hippocampus after traumatic brain injury via activation of the MEK/ERK pathway [

34]. The association of S1P signaling and the MEK/ERK pathway highlights another important role of S1P / S1PR signaling in the amplification of receptor tyrosine kinase signals. The activation of most RTKs result in the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade consisting of Ras, Raf, MEK, and ERK [

35]. The translocation of SphK1 to the plasma membrane after RTK signaling, as discussed above, is dependent on the ERK1/2 phosphorylation of SphK1 at Ser 225 [

36]. Once activated, SphK1 generates S1P, which can then be transported outside the cell to activate the S1PRs in both an autocrine and paracrine fashion [

37]. Completing the positive feedback loop, activation of Gαi coupled S1PRs can then activate the MAPK pathway reinforcing SphK1 activation and enhancing the production of S1P. This provides a mechanism by which the body can elicit a robust mitogen signaling response without the need to produce large amounts of proteins, and due to the sphingolipid salvage pathway, the sphingosine used to generate S1P can also be recovered via dephosphorylation further limiting biosynthetic needs within the cell. A classic example of this is nerve growth factor (NGF) signaling (

Figure 1) mediated through the tropomyosin receptor kinase A (TrkA) receptor [

38].

While the expression and function of S1PR1-3 is well established and characterized in neurons, the detection and characterization of S1PR4 and S1PR5 remains controversial. While there are limited reports of synaptic expression of S1PR4 and S1PR5 in rat and mouse neurons, more work needs to be done to confirm these findings [

39,

40].

Microglia

The primary innate immune cells in the CNS are specialized macrophages called microglia. Similar to other organ specific resident macrophages microglia are professional phagocytic cells which surveil their tissue environment and eliminate pathogens and cellular debris [

41]. Traditionally microglia have been described as either resting or activated, with activated microglia being divided into two distinct categories referred to as M1 and M2. M1 microglia stimulate inflammation and subsequent neurotoxicity, whereas M2 microglia promote neuroprotection via anti-inflammatory effects [

42]. With the advent of single cell RNA sequencing (ssRNAseq), single cells mass cytometry, and increased capabilities in live cell imaging it has become apparent that this may have been an oversimplification which is no more useful than body mass index as a measure of obesity [

43,

44]. Unfortunately, due to the recent discovery of this heterogeneity and the inertia behind the use of M1 and M2, much of the available knowledge on S1PR signaling available for this review still relies on this flawed classification. As such, we will describe the roles of microglial S1PR signaling including these classifications despite the inherent flaws while also acknowledging the limitations.

Microglia express S1PR1, S1PR2, and S1PR3 isoforms, although most evidence suggests that all three receptors have conserved biological effects after stimulation. In mice, exposure to the amyloid β (Aβ) peptide results in an inflammatory microglial phenotype (or M1) characterized by the increased expression of the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and S1PR1, and isoform specific S1PR1 inhibition prevents this activation by reducing Aβ induced TLR4 / S1PR1 expression increases and decreasing the levels of the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α and chemokine CXCL10 [

45]. Additionally, inhibition or siRNA mediated knockdown of S1PR1 reduces microglial activation, TNF-α, and IL-1β expression after ischemia and lipopolysaccharide stimulation [

46]. Similarly, in the context of diabetic induced cognitive deficit in mice inhibition of S1PR2 improves synaptic plasticity, decreases microglial apoptosis, reduces the levels of proinflammatory microglia, and increases the levels of anti-inflammatory microglia which has traditionally been describes as reprogramming from an M1 to an M2 phenotype [

47]. In the context of hepatic encephalopathy induced hyperammonemia S1PR2 activation contributes to astrocyte mediated hippocampal neuroinflammation, IL-1β production, and cognitive impairment through the Gβγ associated signaling cascade [

48]. S1PR3 activation after cerebral ischemia has also been shown to contribute to the development of an M1 phenotype via ERK1/2 activation, increased microglial proliferation, and the production of proinflammatory cytokines which could be reduced through the pharmacological inhibition of S1PR3 [

49]. Conversely, activation of S1PR1 during ischemia promotes an anti-inflamatory M2 phenotype by reducing ERK1/2 activation and increasing Akt phosphorylation suggesting a receptor specific response to restricted blood flow to the brain and providing the only evidence of an anti-inflammatory (M2) response in microglia [

46].

Astrocytes

Astrocytes are the most abundant cells in the brain, and these glial cells play multiple roles in the CNS dependent on the specific brain region in which they reside. Due to this spatial based diversity in function the morphology, cell surface receptor expression and production of cytokines and chemokines also varies based on their location [

50]. Astrocytes can act in opposing roles, both enhancing immune responses and inhibiting myelin repair but also dampen immune responses and support OG mediated myelin repair [

51]. Astrocytes also play roles in establishment of the blood-brain barrier, regulate brain ion homeostasis, and modulate neuronal circuit function and assembly [

52]. Due to their diverse range of function astrocytes are a complex group of cells, and characterization of the signaling pathways are far harder to elucidate than other CNS resident cells.

S1PR1 expression is induced at astrocyte-neuron contact sites, and this expression drives complexity and induces the expression of SPARCL1 and thrombospondin 4 which are involved in synapse formation [

53]. Loss of S1PR1 expression has been found to reduce astrocyte process extension and retraction, and the deletion of the gene in both

Drosophila and zebrafish results in extensive impairment of motor function [

54]. Additionally, the astrocyte specific deletion of S1PR1 or its pharmacological inhibition has a protective effect in the context of the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model of multiple sclerosis, reducing the number of reactive astrocytes and preventing astrogliosis [

55]. S1PR3 is highly expressed in astrocytes, and its expression increases in response to neuroinflammation. Stimulation of S1PR3, and to a lesser extent S1PR2, when coupled to Gα12/13 activates RhoA and potentiates inflammation by upregulating the expression IL-6, COX-2, and VEGFa [

56].

S1PRs and CNS Barrier Function

The brain microenvironment is tightly regulated to ensure proper metabolic activity, limit exposure to blood pathogens, and promote proper neuronal function. Three separate barrier systems regulate the influx and efflux molecules into the CNS, each serving distinct roles to protect the brain parenchyma. The most well characterized is the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which is comprised of a collection of astrocytes, microglia, endothelial cells, and pericytes in the capillary beds that supply the brain [

57]. The BBB is the largest of the three barrier systems, with a combined surface area between 12 and 18 meters2 in an average adult human [

58]. The next most characterized system is the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB), mainly comprised of CSF facing epithelial cells in the choroid plexus which secrete CSF into the ventricular system in the brain [

59]. Finally, tight junction expressing epithelial-like cells in the meninges form the arachnoid barrier (AB) which isolates extracellular fluid in the CNS from the rest of the body [

60]. The AB is the least characterized of the barrier systems, and it’s avascular nature results in limited impact on the influx of molecules into the CNS [

58].

Of the three S1P-S1PR signaling is best characterized in the BBB with S1PR1 and S1PR3 working together to promote proper barrier function. S1PR1 signaling in in endothelial cells activates the Rho/Rac pathway inducing cell spreading reducing gaps between neighboring cells [

61]. Additionally, S1PR1 activation promotes the expression and subcellular translocation of tight junction (TJ)proteins including claudin-5, occluding, and ZO-1 stabilizing TJs [

62]. Moreover, S1PR1 signaling also increases VE-cadherin translocation to sites of adherens junctions (AJ) at cell contact regions further stabilizing cell to cell contacts [

63]. S1PR3 signaling cells promotes endothelial cell progenitor migration and proliferation and promotes vasoconstriction in vascular smooth muscle cells contribute to barrier function [

64]. Interestingly, the loss of S1PR1 expression in mice results in results in a reversible increase of BBB permeability, suggesting that S1PR1 inhibition may provide a pharmacological strategy to increase the delivery of drugs into the CNS [

62].

S1PR Modulation

Due to the ubiquitous involvement of S1P signaling in neuroprotection, modulation of S1PR activity has gained interest in the treatment of multiple diseases. The first S1PR modulator approved by the FDA was fingolimod, which has been used to treat relapsing and remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) since 2010 [

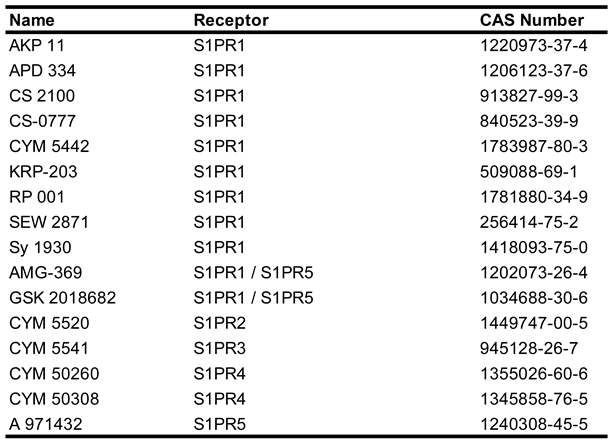

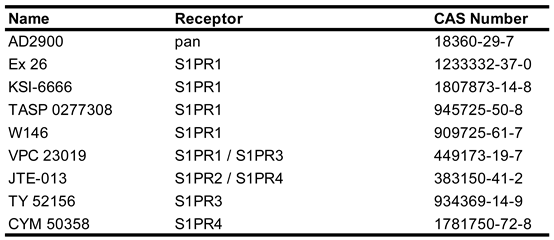

65]. To date more than 30 synthetic small molecules have been developed to modulate the activity of the S1PRs, with many being synthetic sphingosine derviatives [

66]. Physiologically, S1P receptors 1-3 are expressed in all organ systems across the body, with S1PR 5 being expressed mainly in the immune system and S1PR5 expression mostly limited to oligodendrocytes in the CNS and natural killer cells in the immune system [

67]. As previously discussed, S1P receptors bind to a diverse array of Gα proteins and can act to either in conjunction with or in opposition to each other. Due to this efforts have been made to develop and characterize both isoform specific agonists (

Table 2) and antagonists (

Table 3) to study their discrete functions and explore the potential for disease modifying treatments (DMT) [

66]. Despite the number of small molecules developed to activate or inhibit the activity of S1PRs, none of these molecules have been approved for treatment of any pathological condition.

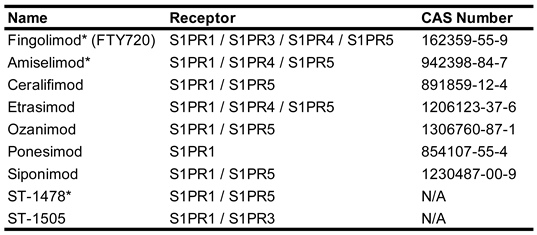

A third class of S1PR modulators, which exert their effects through functional antagonism (

Table 4), have found greater success. These drugs exert their antagonistic effects through initial activation of the S1PR followed be decreased surface expression on the cell surface resulting in desensitization of the cell to subsequent S1P induced signaling [

68]. Fingolimod (Gilenya®, Novartis) the first approved S1PR modulator, shows higher affinity to S1PR1 but is able to bind to and interact with all S1PRs except S1PR2 increasing the risk of off target effects [

69]. Attempts to increase receptor selectivity have given rise to a second generation of functional antagonists, some of which have found success in preclinical studies or clinical use both inside and outside the CNS. Of particular note are ozanimod (Zeposia®, Bristol Myers Squibb), ponesimod (Ponvory®, Vanda Pharmaceuticals), siponimod (Mayzent®, Novartis), and etrasimod (Velsipity®, Pfizer) which have all received FDA approval within the past 5 years. Ozanimod, which targets S1PR1 and S1PR5, received FDA approval in 2020 for the treatment of MS and 2021 for the treatment of Ulcerative Colitis and is currently undergoing phase III trials for the treatment of Chron’s disease [

70]. Ponesimod, which targets S1PR1, received FDA approval in 2023 for the treatment of MS and has completed phase II trials examining it’s potential in the treatment of psoriasis [

71]. Siponimod, which targets S1PR1 and S1PR5, was approved in 2019 for the treatment of MS and has just begun a phase II clinical trial to examine its potential for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (NCT06639282). Etrasimod, which targets S1PR1, S1PR4, and S1PR5, received FDA approval in 2023 for the treatment of MS, is undergoing phase II trials for treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor diarrhea (NCT06521762) and ulcerative colitis (NCT06398626), and a phase II/III trial for the treatment of Chron’s disease (NCT04173273).

Conclusion

The bioactivity of S1P was first described in 1991, but its initial effects were thought to be limited to the intercellular environment [

72]. First described as the ceramide/S1P rheostat, it was thought that S1P exerted pro-growth signals in opposition to ceramide induced apoptosis suggesting a fundamental role in cellular life or death decisions [

73]. Shortly after the description of the rheostat the first S1P receptor was identified, suggesting multiple roles for this enigmatic signaling lipid [

74]. Currently it is accepted that the rheostat works in conjunction with the autocrine and paracrine signals that the S1PRs mediate2. The S1P/S1PR signaling axis in brain health and CNS pathology has been studied extensively since the first S1PR modulator was identified [

75]. In the two decades since the development of more selective small molecule agonists and antagonists has revealed even more about the cell specific roles that S1PRs play in the CNS, shedding light on their role in brain development and homeostasis. While S1P receptors 1-3 are expressed almost ubiquitously, S1PR4 and S1PR5 expression appears to be tightly controlled and limited to specific cell types [

76]. Targeting S1PR signaling has to multiple drugs in clinical use, both inside and outside the CNS, highlighting the therapeutic potential that this pathway presents. As the number and diversity of S1P modulators continues to increase so too will our understanding of the role S1P receptors play in human physiology, and with a search for S1P on PubMed listing over 400 indexed papers per year since 2012 S1P it has been and looks to remain a consistent research focus for years to come.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.N.; Investigation: E.G., S.D., L.J.C, D.P., L.H., A.J., A.C., and J.N.; Writing-original draft: B.G. and J.N.; Writing- review and editing: B.G., S.D., and J.N.; Designing and preparing figures: B.G., S.D., and J.N.; The figure was created with BioRender. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

J.N. was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R00HD096117 and pilot funding from the Virginia Commonwealth University Parkinson’s and Movement Disorders Center; E.G., L.J.C., and L.H. were supported in part by funding and/or programmatic assistance from the VCU Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program and the VCU Fellowships for Undergraduate Research.

Acknowledgments

We regret due to the breadth of existing research on S1P and S1PR related signaling that we could not acknowledge all the researchers that have contributed to this field of study. We would also like to acknowledge the Virginia Commonwealth University Departments of Biology and Chemistry who supported the undergraduate students E.G, L.J.C., D.P., L.H., A.C. and A.J. through curricular support during the writing of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no potential conflicts of interest relating to this manuscript.

References

- Newton, J.; Milstien, S.; Spiegel, S. Niemann-Pick type C disease: The atypical sphingolipidosis. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2018, 70, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newton, J.; Lima, S.; Maceyka, M.; Spiegel, S. Revisiting the sphingolipid rheostat: Evolving concepts in cancer therapy. Exp. Cell Res. 2015, 333, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyne, S.; Adams, D.R.; Pyne, N.J. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and sphingosine kinases in health and disease: Recent advances. Prog. Lipid Res. 2016, 62, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alemany, R.; van Koppen, C.J.; Danneberg, K.; ter Braak, M.; zu Heringdorf, D.M. Regulation and functional roles of sphingosine kinases. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2007, 374, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wattenberg, B.W.; Pitson, S.M.; Raben, D.M. The sphingosine and diacylglycerol kinase superfamily of signaling kinases: localization as a key to signaling function. J. Lipid Res. 2006, 47, 1128–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, S.; Milstien, S.; Spiegel, S. Sphingosine and Sphingosine Kinase 1 Involvement in Endocytic Membrane Trafficking. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 3074–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, S.; Takabe, K.; Newton, J.; Saurabh, K.; Young, M.M.; Leopoldino, A.M.; Hait, N.C.; Roberts, J.L.; Wang, H.-G.; Dent, P.; et al. TP53 is required for BECN1- and ATG5-dependent cell death induced by sphingosine kinase 1 inhibition. Autophagy 2018, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaho, V.A.; Hla, T. An update on the biology of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors. J. Lipid Res. 2014, 55, 1596–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Anderson, P.J.; Rajagopal, S.; Lefkowitz, R.J.; Rockman, H.A. G Protein-Coupled Receptors: A Century of Research and Discovery. Circ. Res. 2024, 135, 174–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofuji, P.; Araque, A. G-Protein-Coupled Receptors in Astrocyte–Neuron Communication. Neuroscience 2020, 456, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.-F. G protein-coupled receptors function as cell membrane receptors for the steroid hormone 20-hydroxyecdysone. Cell Commun. Signal. 2020, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, S. Sphingosine 1-phosphate: a ligand for the EDG-1 family of G-protein-coupled receptors. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2000, 905, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Scheerer, P.; Hofmann, K.P.; Choe, H.-W.; Ernst, O.P. Crystal structure of the ligand-free G-protein-coupled receptor opsin. Nature 2008, 454, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanlon, C.D.; Andrew, D.J. Outside-in signaling – a brief review of GPCR signaling with a focus on the Drosophila GPCR family. J. Cell Sci. 2015, 128, 3533–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’brien, J.B.; Wilkinson, J.C.; Roman, D.L. Regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS) proteins as drug targets: Progress and future potentials. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 18571–18585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kankanamge, D.; Tennakoon, M.; Karunarathne, A.; Gautam, N. G protein gamma subunit, a hidden master regulator of GPCR signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassone-Corsi, P. The cyclic AMP pathway. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a011148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wettschureck, N.; Offermanns, S. Mammalian G Proteins and Their Cell Type Specific Functions. Physiol. Rev. 2005, 85, 1159–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syrovatkina, V.; Alegre, K.O.; Dey, R.; Huang, X.-Y. Regulation, Signaling, and Physiological Functions of G-Proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2016, 428, 3850–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.I.; Blaabjerg, M.; Freude, K.; Meyer, M. RhoA Signaling in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; Lariosa-Willingham, K.D.; Lin, F.; Webb, M.; Rao, T.S. Characterization of lysophosphatidic acid and sphingosine-1-phosphate-mediated signal transduction in rat cortical oligodendrocytes. Glia 2003, 45, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaillard, C.; et al. Edg8/S1P5: an oligodendroglial receptor with dual function on process retraction and cell survival. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci. 2005, 25, 1459–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Jia, G.; Wu, C.; Wang, W.; Cheng, L.; Li, Q.; Li, Z.; Luo, K.; Yang, S.; Yan, W.; et al. Structures of signaling complexes of lipid receptors S1PR1 and S1PR5 reveal mechanisms of activation and drug recognition. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 1263–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binish, F.; Xiao, J. Deciphering the role of sphingosine 1-phosphate in central nervous system myelination and repair. J. Neurochem. 2024, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedsadr, M.S.; Weinmann, O.; Amorim, A.; Ineichen, B.V.; Egger, M.; Mirnajafi-Zadeh, J.; Becher, B.; Javan, M.; Schwab, M.E. Inactivation of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2 (S1PR2) decreases demyelination and enhances remyelination in animal models of multiple sclerosis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018, 124, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motyl, J.; Strosznajder, J.B. Sphingosine kinase 1/sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors dependent signalling in neurodegenerative diseases. The promising target for neuroprotection in Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacol. Rep. 2018, 70, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.X.; Nicol, G.D.; Kays, J.S.; Li, C.; Xie, W.; Strong, J.A.; Zhang, J.-M. The Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptor, S1PR1, Plays a Prominent But Not Exclusive Role in Enhancing the Excitability of Sensory Neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2010, 104, 2741–2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeldt, H.M.; Hobson, J.P.; Maceyka, M.; Olivera, A.; Nava, V.E.; Milstien, S.; Spiegel, S. EDG-1 links the PDGF receptor to Src and focal adhesion kinase activation leading to lamellipodia formation and cell migration. FASEB J. 2001, 15, 2649–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, H.; Takuwa, N.; Yokomizo, T.; Sugimoto, N.; Sakurada, S.; Shigematsu, H.; Takuwa, Y. Inhibitory Regulation of Rac Activation, Membrane Ruffling, and Cell Migration by the G Protein-Coupled Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor EDG5 but Not EDG1 or EDG3. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 9247–9261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizugishi, K.; Yamashita, T.; Olivera, A.; Miller, G.F.; Spiegel, S.; Proia, R.L. Essential Role for Sphingosine Kinases in Neural and Vascular Development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 11113–11121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harada, J.; Foley, M.; Moskowitz, M.A.; Waeber, C. Sphingosine-1-phosphate induces proliferation and morphological changes of neural progenitor cells. J. Neurochem. 2004, 88, 1026–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, A.; Ohmori, T.; Kashiwakura, Y.; Ohkawa, R.; Madoiwa, S.; Mimuro, J.; Shimazaki, K.; Hoshino, Y.; Yatomi, Y.; Sakata, Y. Antagonism of Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptor-2 Enhances Migration of Neural Progenitor Cells Toward an Area of Brain Infarction. Stroke 2008, 39, 3411–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempf, A.; Tews, B.; Arzt, M.E.; Weinmann, O.; Obermair, F.J.; Pernet, V.; Zagrebelsky, M.; Delekate, A.; Iobbi, C.; Zemmar, A.; et al. The Sphingolipid Receptor S1PR2 Is a Receptor for Nogo-A Repressing Synaptic Plasticity. PLoS Biol. 2014, 12, e1001763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, H.; Zhang, X.; Su, X.; Yang, Y.; Yu, X.; He, X. Activation of Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptor 1 Enhances Hippocampus Neurogenesis in a Rat Model of Traumatic Brain Injury: An Involvement of MEK/Erk Signaling Pathway. Neural Plast. 2016, 2016, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, M.M.; Morrison, D.K. Integrating signals from RTKs to ERK/MAPK. Oncogene 2007, 26, 3113–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitson, S.M.; et al. Activation of sphingosine kinase 1 by ERK1/2-mediated phosphorylation. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 5491–5500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiegel, S.; Maczis, M.A.; Maceyka, M.; Milstien, S. New insights into functions of the sphingosine-1-phosphate transporter SPNS2. J. Lipid Res. 2019, 60, 484–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toman, R.E.; Payne, S.G.; Watterson, K.R.; Maceyka, M.; Lee, N.H.; Milstien, S.; Bigbee, J.W.; Spiegel, S. Differential transactivation of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors modulates NGF-induced neurite extension. J. Cell Biol. 2004, 166, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skoug, C.; Martinsson, I.; Gouras, G.K.; Meissner, A.; Duarte, J.M.N. Sphingosine 1-Phoshpate Receptors are Located in Synapses and Control Spontaneous Activity of Mouse Neurons in Culture. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 47, 3114–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.H.; Fehrenbacher, J.C.; Vasko, M.R.; Nicol, G.D. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Via Activation of a G-Protein-Coupled Receptor(s) Enhances the Excitability of Rat Sensory Neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2006, 96, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mass, E.; Nimmerjahn, F.; Kierdorf, K.; Schlitzer, A. Tissue-specific macrophages: how they develop and choreograph tissue biology. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2023, 23, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, S.; et al. Sulforaphane attenuates microglia-mediated neuronal necroptosis through down-regulation of MAPK/NF-κB signaling pathways in LPS-activated BV-2 microglia. Pharmacol. Res. 2018, 133, 218–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, C.; Jiang, J.; Tan, Y.; Chen, S. Microglia in neurodegenerative diseases: mechanism and potential therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ransohoff, R.M. A polarizing question: do M1 and M2 microglia exist? Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 987–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Elsherbini, A.; Crivelli, S.M.; Tripathi, P.; Harper, C.; Quadri, Z.; Spassieva, S.D.; Bieberich, E. The S1P receptor 1 antagonist Ponesimod reduces TLR4-induced neuroinflammation and increases Aβ clearance in 5XFAD mice. EBioMedicine 2023, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaire, B.P.; Lee, C.-H.; Sapkota, A.; Lee, S.Y.; Chun, J.; Cho, H.J.; Nam, T.-G.; Choi, J.W. Identification of Sphingosine 1-Phosphate Receptor Subtype 1 (S1P1) as a Pathogenic Factor in Transient Focal Cerebral Ischemia. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 55, 2320–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.; Fernandes, V.; Preeti, K.; Rajan, S.; Khatri, D.K.; Singh, S.B. S1PR2 inhibition mitigates cognitive deficit in diabetic mice by modulating microglial activation via Akt-p53-TIGAR pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 126, 111278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho-Alonso, M.; et al. Enhanced Activation of the S1PR2-IL-1β-Src-BDNF-TrkB Pathway Mediates Neuroinflammation in the Hippocampus and Cognitive Impairment in Hyperammonemic Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaire, B.P.; Song, M.-R.; Choi, J.W. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor subtype 3 (S1P3) contributes to brain injury after transient focal cerebral ischemia via modulating microglial activation and their M1 polarization. J. Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gradisnik, L.; Velnar, T. Astrocytes in the central nervous system and their functions in health and disease: A review. World J. Clin. Cases 2023, 11, 3385–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliven, B.; Miron, V.; Chun, J. The neurobiology of sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling and sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulators. Neurology 2011, 76, S9–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, N.J.; Barres, B.A. Neuroscience: Glia - more than just brain glue. Nature 2009, 457, 675–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Kordula, T.; Spiegel, S. Neuronal contact upregulates astrocytic sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 to coordinate astrocyte-neuron cross communication. Glia 2021, 70, 712–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, A.M.; Del Poeta, M. Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors and innate immunity. Cell. Microbiol. 2018, 20, e12836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.W.; Gardell, S.E.; Herr, D.R.; Rivera, R.; Lee, C.-W.; Noguchi, K.; Teo, S.T.; Yung, Y.C.; Lu, M.; Kennedy, G.; et al. FTY720 (fingolimod) efficacy in an animal model of multiple sclerosis requires astrocyte sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1P 1 ) modulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 108, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dusaban, S.S.; Chun, J.; Rosen, H.; Purcell, N.H.; Brown, J.H. Sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 3 and RhoA signaling mediate inflammatory gene expression in astrocytes. J. Neuroinflammation 2017, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cartier, A.; Hla, T. Sphingosine 1-phosphate: Lipid signaling in pathology and therapy. Science 2019, 366, aar5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, N.J.; Patabendige, A.A.K.; Dolman, D.E.M.; Yusof, S.R.; Begley, D.J. Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010, 37, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, P.; Davies, S.; Speake, T.; Millar, I. Molecular mechanisms of cerebrospinal fluid production. Neuroscience 2004, 129, 955–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derk, J.; Como, C.N.; Jones, H.E.; Joyce, L.R.; Kim, S.; Spencer, B.L.; Bonney, S.; O’rourke, R.; Pawlikowski, B.; Doran, K.S.; et al. Formation and function of the meningeal arachnoid barrier and development around the developing mouse brain. Dev. Cell 2023, 58, 635–644.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, J.G.; et al. Sphingosine 1-phosphate promotes endothelial cell barrier integrity by Edg-dependent cytoskeletal rearrangement. J. Clin. Investig. 2001, 108, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanagida, K.; Liu, C.H.; Faraco, G.; Galvani, S.; Smith, H.K.; Burg, N.; Anrather, J.; Sanchez, T.; Iadecola, C.; Hla, T. Size-selective opening of the blood–brain barrier by targeting endothelial sphingosine 1–phosphate receptor 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 4531–4536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Hla, T. S1P control of endothelial integrity. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2014, 378, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prager, B.; Spampinato, S.F.; Ransohoff, R.M. Sphingosine 1-phosphate signaling at the blood–brain barrier. Trends Mol. Med. 2015, 21, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Mathur, A.G.; Pradhan, S.; Singh, D.B.; Gupta, S. Fingolimod (FTY720): First approved oral therapy for multiple sclerosis. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2011, 2, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, S.S.; Gharai, S.R.; Sahu, S.K.; Ravichandiran, V.; Swain, S.P. The Current Landscape in the Development of Small-molecule Modulators Targeting Sphingosine-1-phosphate Receptors to Treat Neurodegenerative Diseases. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2024, 24, 2431–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyapina, E.; Marin, E.; Gusach, A.; Orekhov, P.; Gerasimov, A.; Luginina, A.; Vakhrameev, D.; Ergasheva, M.; Kovaleva, M.; Khusainov, G.; et al. Structural basis for receptor selectivity and inverse agonism in S1P5 receptors. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, V.; Akgün, K.; Ziemssen, T. Current status and new developments in sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor antagonism: fingolimod and more. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2022, 18, 675–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyckman, A.J. Modulators of Sphingosine-1-phosphate Pathway Biology: Recent Advances of Sphingosine-1-phosphate Receptor 1 (S1P1) Agonists and Future Perspectives. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 5267–5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feagan, B.G.; Schreiber, S.; Afzali, A.; Rieder, F.; Hyams, J.; Kollengode, K.; Pearlman, J.; Son, V.; Marta, C.; Wolf, D.C.; et al. Ozanimod as a novel oral small molecule therapy for the treatment of Crohn’s disease: The YELLOWSTONE clinical trial program. Contemp. Clin. Trials 2022, 122, 106958–106958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Goren, I.; Yang, B.; Lin, S.; Li, J.; Elias, M.; Fiocchi, C.; Rieder, F. Review article: the sphingosine 1 phosphate/sphingosine 1 phosphate receptor axis - a unique therapeutic target in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 55, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Desai, N.N.; Olivera, A.; Seki, T.; Brooker, G.; Spiegel, S. Sphingosine-1-phosphate, a novel lipid, involved in cellular proliferation. J. Cell Biol. 1991, 114, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuvillier, O.; Pirianov, G.; Kleuser, B.; Vanek, P.G.; Coso, O.A.; Gutkind, J.S.; Spiegel, S. Suppression of ceramide-mediated programmed cell death by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Nature 1996, 381, 800–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-J.; Van Brocklyn, J.R.; Thangada, S.; Liu, C.H.; Hand, A.R.; Menzeleev, R.; Spiegel, S.; Hla, T. Sphingosine-1-Phosphate as a Ligand for the G Protein-Coupled Receptor EDG-1. Science 1998, 279, 1552–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandala, S.; Hajdu, R.; Bergstrom, J.; Quackenbush, E.; Xie, J.; Milligan, J.; Thornton, R.; Shei, G.-J.; Card, D.; Keohane, C.; et al. Alteration of Lymphocyte Trafficking by Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor Agonists. Science 2002, 296, 346–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.; Hla, T.; Lynch, K.R.; Spiegel, S.; Moolenaar, W.H. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXVIII. Lysophospholipid Receptor Nomenclature: TABLE 1. Pharmacol. Rev. 2010, 62, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).