1. Introduction

More than 10% of the US population is diabetic, while more than half suffer from (DR) diabetic retinopathy [

1,

2]. However, there is no treatment for non-proliferative DR (NPDR), there are no biomarkers for the progression of DR, and treatments for late-stage proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) is futile to ~30% of the diabetics receiving care [

3,

4]. With such a significant healthcare issue, new biomarkers and therapeutic targets are required to halt the progression of this incurable microvascular disease.

The etiology of DR is multifactorial. Yet, multiple studies provide strong evidence that hyperglycemia enhances retinal oxidative stress, which leads to the development of DR [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. One of the diabetes-mediated mechanisms of oxidative stress is Ferrous iron (Fe

2+) accumulation in the retina [

10]. Diabetes initiates Fe

2+ uptake in the retina [

10]. The retina’s compensatory mechanism for this iron overload is to oxidize the excess Fe

2+ to elicit extracellular release of (Fe

3+) ferric iron [

11]. Through the Fenton reaction, ferrous iron is oxidized by hydrogen peroxide, which generates ferric iron and hydroxyl radicals [

12]. These hydroxyl radicals are toxic reactive oxygen species that exacerbate oxidative stress in the diabetic retina. Enhanced oxidative stress causes retinal endothelial cell death and tight junction protein degradation in the retinal microvasculature. This can lead to retinal vascular leakage, capillary non-perfusion, and the development of NPDR and/or diabetic macular edema [

13,

14,

15].

Per the literature,

Steap4 is upregulated in the retina of diabetic rats [

16]. This is of interest because STEAP4 is a ferroxidase that catalyzes the reduction of extracellular Fe

3+ to Fe

2+ for cellular uptake [

17,

18]. Since STEAP3 maintains iron homeostasis in the thriving retina [

19,

20], it is unknown why only STEAP4 is upregulated in the diabetic retina. When extracellular Fe

3+ binds to the C-terminal transmembrane domain of STEAP4, NADPH oxidoreductase binds to the cytosolic N-terminal domain of STEAP4 [

21]. This induces extracellular iron reduction, intracellular iron uptake, and cellular production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). In this current study, we discovered that

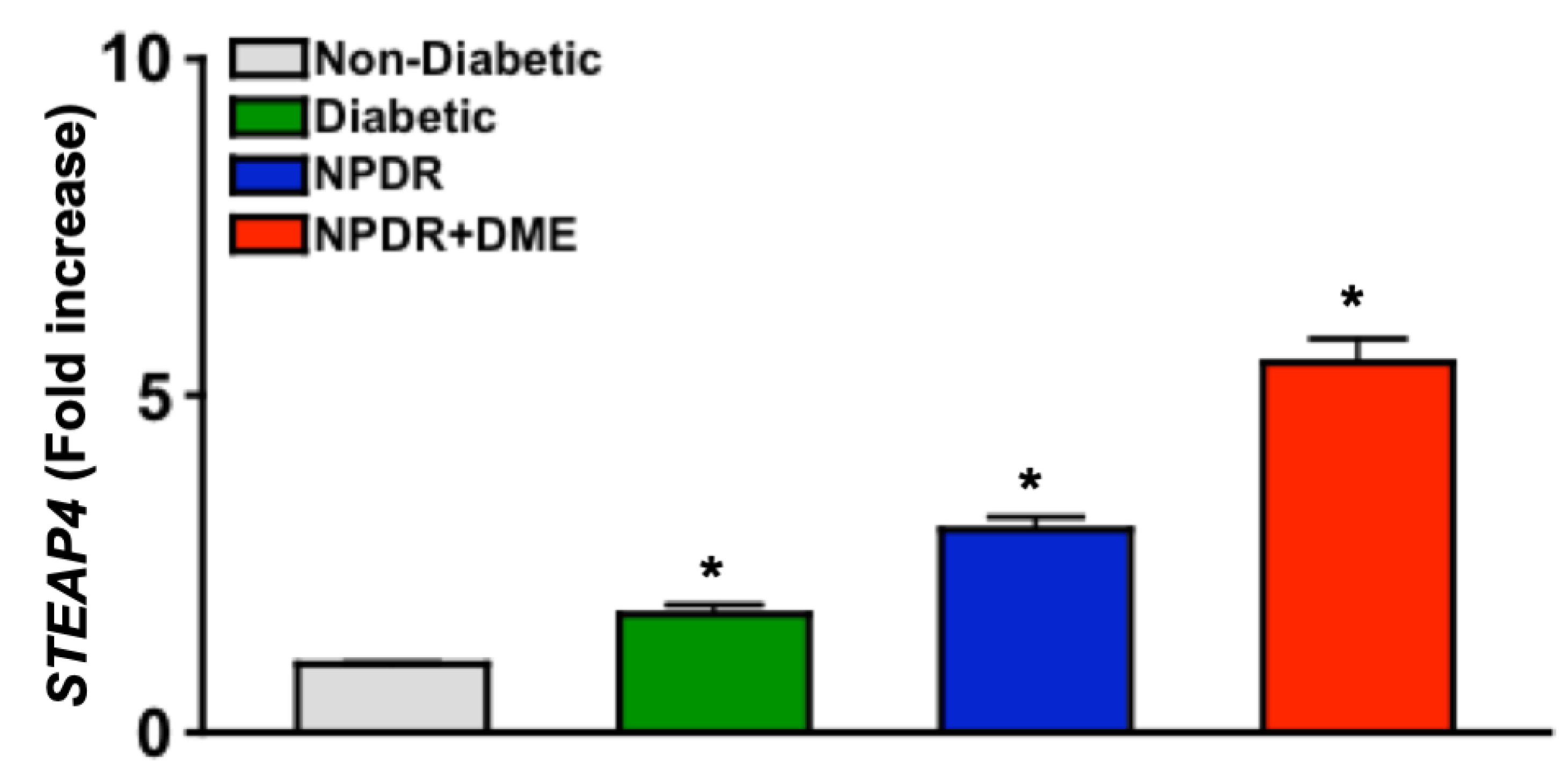

STEAP4 is upregulated in the blood of diabetic patients, and that levels of

STEAP4 correlates to the severity of DR. Suggesting that STEAP4 could be a clinically relevant biomarker for the progression of DR. Since STEAP4 produces ROS while catalyzing iron, we postulated that STEAP4 would enhance oxidative stress in the diabetic retina. Consequently, increased oxidative stress should impel vascular damage in the diabetic retina, which can lead to the onset of DR. Thus, we hypothesized that STEAP4 inhibition in the diabetic retina would decrease retinal oxidative stress and arrest vascular impairment. Thus, it is the overarching goal of this study to define the role of this potentially novel biomarker in the development of DR.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Blood Collection and PBMC Sample Preparation from Non-Diabetic and Diabetic Patients

Non-diabetic and Type II diabetic male patients were enrolled in this IRB-approved clinical study at Louis Stokes Cleveland VA Medical Center; during routine eye exams. Written patient consent was provided prior to blood and patient record collection. Non-diabetic patients, and diabetic patients: without diabetic retinopathy, with moderate (ETDRS score = 43) non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) without macular edema, or with diabetic macular edema (DME) were enrolled. Patients’ records and blood samples were de-identified and numerically coded, to protect patient privacy. Sera were isolated through centrifugation of whole blood collected in vacutainer serum separator tubes (BD SST#367985, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Blood was also collected in vacutainer sodium heparin tubes (BD #236874 Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) for isolation of PBMC. PBMC were negatively selected by magnetic bead separation; using RoboSep-S (Stemcell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada), and the EasySep human PBMC isolation kit (Stemcell Technologies #19654, Vancouver, Canada).

2.2. Quantitative PCR Analysis of STEAP4 Expression in PBMC of Diabetics

According to the manufacturer’s directions, RNA was extracted from PBMC using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Samples with an OD260/280 ratio of 2.0 were used to generate cDNA using qScript (Quanta Bio, Beverly, MA, USA). Quantitative PCR was performed on a Lightcycler 96 System (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), using Fast Start Universal SYBR green (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) as the detecting probe. STEAP4 expression was quantified using human STEAP4 primers (NM_024636), and human ACTB primers (NM_001101) as the loading control. The ΔΔCt score was equated to quantify the levels of STEAP4 mRNA expression in human donor PBMC.

2.3. Streptozotocin Induced Diabetes in C57BL/6 Mice

Male C57BL/6 mice (strain no. 000664, The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) received IP injections of 60 mg/Kg of BW (STZ) streptozotocin (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA, USA) in 0.1M citrate buffer (pH 4.5) for five consecutive days; after a 6-hour fast. Food was returned to the mice immediately after each injection, and water was provided ad lib. Diabetes was confirmed by a 6-hour fasted blood glucose (FBG), with concentrations greater than 275 mg/dL. Diabetic conditions were verified by 3 separate FBG measures 14-21 days after the last STZ injection. Blood glucose was measured using a conventional consumer glucose testing meter and strips (FBG of non-diabetic mice were 150 + 40 mg/dL). Diabetic conditions were further confirmed by quantifying the hemoglobin A1C percentage, using the Crystal Chem Mouse A1C kit and Controls (Elk Grove Village, IL, USA). Mice were weighed weekly. When body weight loss exceeded 10% per week, 0-0.2 Units of insulin (Humulin N, NPH, Eli Lilly, Indianapolis, IN, USA) was administered on an as-needed basis to maintain body weight.

2.4. Anti-STEAP4 Neutralizing Antibodies and Treatment Regimen

The anti-STEAP4 neutralizing antibody is an antagonist that blocks Fe3+ binding to the STEAP4 C-terminal domain. Human STEAP4 neutralizing peptide was conjugated to STEAP4 antibody (PEP-0524-neutralizing peptide + PA5-20407-antibody, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) per manufacturer’s instructions; and used to block STEAP4 activity in human Müller glia and human retina endothelial cells (hREC). Neutralizing peptide (CVDNTLTRIRQGWERN of NP_078912.2) was conjugated to STEAP4 antibody, per the manufacturer’s instructions (MyBioSource, San Diego, CA, USA); and used to inhibit STEAP4 activity in 661W mouse cells and mouse retinas. For intravitreal injections, anti-STEAP4 was further conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (Imject mcKLH, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). Non-diabetic controls and diabetic C57BL/6 mice received one intravitreal injection of 1 μl saline containing 5 μg of KLH conjugated with anti-STEAP4 (MBS421017-neutralizing peptide + MBS426997-STEAP4 antibody); 1-week after diabetic conditions were confirmed.

Anti-STEAP4 was administered through intravitreal injections to anesthetized mice that received an IP injection of Ketamine: Xylazine cocktail. Proparacaine was applied to numb the eye, and tropicamide was applied to dilate the pupil. A beveled needle (34-gauge NanoFil, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) was used to establish a route to the vitreous cavity. The needle was immediately replaced with a blunt-tip 34-gauge needle, attached to a micro-syringe (Sub-Microliter Injection System, and World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) filled with saline containing 5 μg of anti-STEAP4. After anti-STEAP4 was administered through an intravitreal injection of one eye, eyes were covered with GenTeal 0.3% Hypromellose gel (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA); to protect the corneas from drying. To prevent infection, ophthalmic bacitracin-neomycin-polymyxin triple antibiotic ointment was applied to the procedure eye once daily for 3 consecutive days after the anti-STEAP4 injection was administered.

2.5. Western Immunoblot and Automated WES Analysis of Retina Lysates

Retinas were pooled (n = 6), and homogenized in RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher, Rockland, IL). Levels of protein was quantified in each sample using a BCA assay (Pierce, Waltham, MA, USA), and normalized in buffer to generate equal amounts of protein in samples. Samples of protein lysates were loaded onto SDS Tris-glycine gels and transferred to a PVDF membrane using the BioRad Trans-blot Turbo system (BioRad, Hercules, CA). Western immunoblots were incubated in Intercept blocking buffer (Li-Cor, Lincoln, Nebraska) for 1 hour at room temperature, and further incubated in blocking buffer containing 1:1000 of STEAP4 antibody (ABS998, Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA) for 18 hours at 4°C. Western immunoblots were washed, and incubated with the secondary antibody, and imaged on a Li-Cor Odyssey Imaging System using studio software (LiCor, Lincoln, NE, USA). Quantification was determined by normalizing samples to levels of β-actin in each sample (#8827, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA).

Alternatively, levels of Occludin in protein lysates was quantified using automated WES (Protein Simple, Biotechne, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Samples were loaded on WES cartridges and run according to manufacturer’s instructions, using anti-mouse Occludin antibody (DSHB, Iowa City, IA, USA). Occludin was quantified by an electropherogram generated by WES software; the area under the curve quantitates the level of Occludin in each protein lysate sample.

2.6. Immunofluorescence and Microscopy Analysis of Retina Cross Sections

Slides of retina cryostat sections from non-diabetic and diabetic mouse were blocked in 5% goat serum (R&D Systems Normal Goat Serum #DY005, Minneapolis, MN, USA), for 2 hours at room temperature. For iron analysis, anti-Ferritin antibody (Abcam #ab75973, Cambridge, UK) was diluted 1:100 in PBS + 0.05% TWEEN-20 (Promega #H5152, Madison, WI, USA), applied to slides and incubated for 18h at 4°C. Slides were washed in 3x PBS + 0.05% TWEEN-20 and incubated with goat secondary antibody conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 fluorochrome (Jackson Immuno Research Labs, West Grove, PA) for 2 hours at room temperature. Slides were mounted using DAPI-Fluor mount-G (Southern Biotech #0100-20, Birmingham, AL, USA). Alternatively, cross sections were incubated with primary antibodies; anti-STEAP4 and/or anti-Vimentin (anti-STEAP4 #ABS988, Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA or anti-Vimentin #ab92547, Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA) for 18h at 4°C. Slides were washed with PBS + 0.05% TWEEN-20 and then stained with secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488 or 647, Jackson Immuno Research Labs, West Grove, PA). Since both antibodies were generated from a rabbit host, rabbit serum and Fab fragments were used to prevent non-specific staining.

Lipid peroxidation was examined using 4-Hydroy-2-nonenal (4HNE) staining in retina cryostat sections of diabetic mice. Sections were blocked in 5% normal goat serum, stained with rabbit anti-serum directed against 4HNE (HNE11-S, Alpha Diagnostic, San Antonio, TX, USA), and anti-STEAP4 or anti-Vimentin. Slides were then incubated with Alexa 488 or 647 conjugated secondary antibodies. Images were then viewed on a Leica DMI 6000B widefield microscope, and the Olympus Fluoview FV1200 Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope for 4HNE colocalization analyses.

2.7. Retina Cell Lines

Human retina endothelial cells (hREC) of the microvasculature were purchased from Cell Systems (Catalog #ACBRI, Kirkland, WA, USA). Purity of cells were verified by Cell System to have cytoplasmic uptake of Di-I-Ac-LDL, and positivity of cytoplasmic VWF/Factor VII and CD31. Cells were cultured in manufacturer’s recommended media.

Human Müller glia were isolated from the posterior section of retinal globes from human cadaver eyes (Eversight, Cleveland, OH, USA). Müller glia were mechanically isolated, cultured in DMEM/HAM F12 media at 37°C with 5% CO2, and collected after 3 passages. Cell purity was confirmed by flow cytometry analysis (>99% Vimentin+/GS+).

The 661W cells were a generous gift from Dr. Timothy Kern. This photoreceptor-like cone cell line originated from mouse retina tumors of transgenic mice expressing Sv40T-antigen controlling the interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein promoter, which express photoreceptor cone opsins [

22,

23].

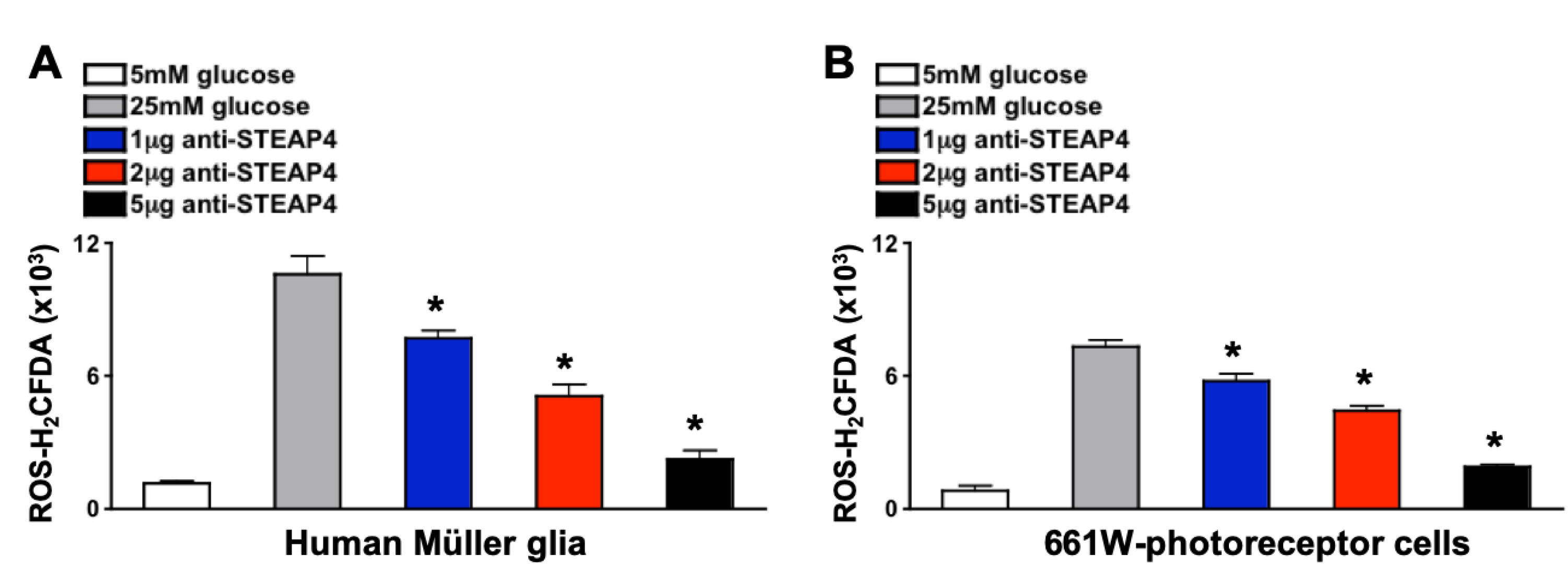

2.8. Detection of Reactive Oxygen Species

Human Müller glia or 661W cells (1x105 cells/well) were cultured in euglycemic or hyperglycemic conditioned media. All treated cells were cultured in optimal conditions (media containing 5mM of glucose) with 1, 2, or 5 μg of anti-human or anti-mouse STEAP4 neutralizing antibody. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. Untreated and anti-STEAP4 treated cells either remained in media containing 5mM of glucose or media was changed, and cells were cultured in hyperglycemic conditions (media containing 25mM of glucose) for 18 hours. Cells were collected and incubated with 10μM H2CFDA (Invitrogen # D399, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at 37°C for 30 minutes in the dark. Levels of ROS were quantified by measuring H2CFDA (ROS fluorescent indicator) on a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD, San Jose, CA, USA).

Alternatively, retina cells were isolated as previously described [

24]. Briefly, cells were isolated from retinas using the Worthington papain dissociation kit (Worthington Biochemical #LK003150, Lakewood, NJ, USA), followed by collagenase incubation for 1 hour at 37°C. Retina cells were washed in PBS, and incubated in H

2CFDA (Invitrogen #D399, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 30 minutes in the dark at 37°C. Levels of ROS- H

2CFDA were quantified on a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD, San Jose, CA, USA).

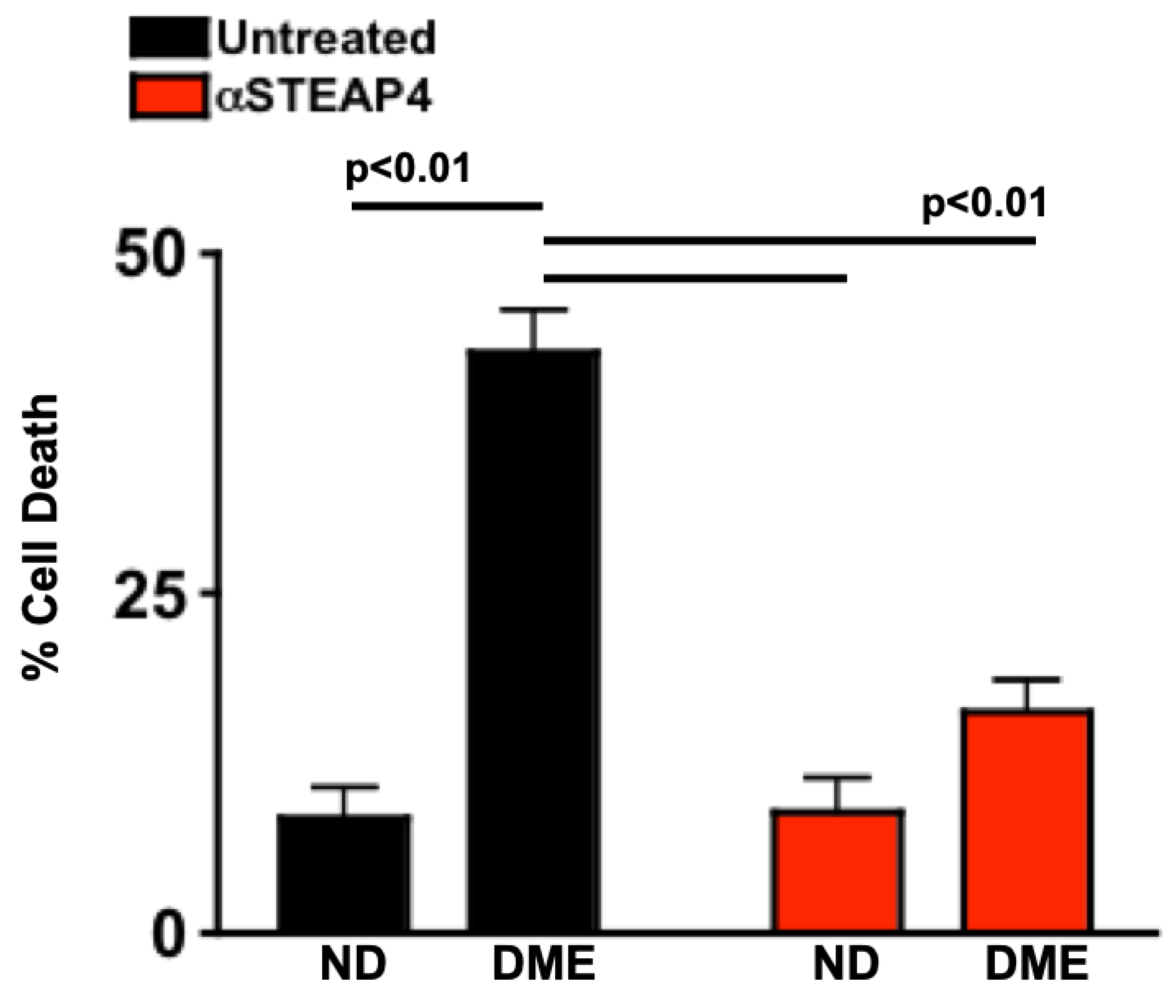

2.9. Human Sera Induced Retinal Vascular Cell Death Analysis

Human vascular cell death assays were performed, as previously described [

25]. Briefly, 1x10

6 hREC/well were cultured in a 6-well plate containing 2 ml of Cell Systems’ media with or without 5 μg of anti-STEAP4 for 2 hours at 37°C with 5% CO

2. After cells reached 80% confluency, 1 ml of media was removed and replaced with 1 ml of human serum of non-diabetic patients or diabetics with NPDR+DME. Cells were incubated with media containing sera for 18 hours at 37°C with 5% CO

2. Cells were collected, stained with 7-AAD (eBioscience #00-6993-50, San Diego, CA), and analyzed for cell death by flow cytometry analyses of 7-AAD positivity.

4. Discussion

Taken together, the results from this study provide strong evidence that STEAP4 is upregulated in diabetic humans and mice. In the diabetic retina, both iron and STEAP4 are increased, which enhances retinal oxidative stress. This then initiates tight junction protein degradation and endothelial cell death in the diabetic retina. These subtle vascular impairments can lead to the development of diabetic retinopathy and vision loss [

13]. When retina cells and mice were treated with anti-STEAP4 these intrinsic pathologies of diabetic retinopathy were halted.

STEAP 1- 4 isoforms are metalloreductases that promote and regulate cellular uptake of iron to maintain homeostasis. All of these STEAP isoforms are expressed in the retina, but only STEAP3 regulates iron homeostasis in the thriving retina [

18,

19]. However, STEAP4 is the only isoform upregulated in the diabetic retina [

16]. In murine models of colon cancer, systemic ablation of STEAP4 halted iron overload and disease pathogenesis in mice [

18,

19]. Analogous to these findings, we discovered both iron and STEAP4 were upregulated in the diabetic retina, and that STEAP4 impelled photoreceptor cells and Müller glia to produce ROS. Consequently, STEAP4 enhances retinal oxidative stress, which is a pivotal precursor to the retinal pathogenesis and the development of diabetic retinopathy [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

The etiology of diabetic retinopathy is multifactorial. Yet, multiple studies provide strong evidence that oxidative stress leads to the development of diabetic retinopathy [

5]. Diabetes mediates chronic inflammation and oxidative stress, which causes gradual changes in the retinal microvasculature. These early-stage changes cause tight junction protein degradation and retina endothelial cell death [

36]. Leading to capillary non-perfusion, vascular leakage, and the onset of non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR). In some cases, these intrinsic pathologies mediate macular edema in the diabetic retina; altering vision [

3]. Here we discovered that

STEAP4 expression was significantly increased in PBMC of diabetics with NPDR and edema than patients with less severe NPDR and no edema. Subsequently, vascular cell death was halted when human retina endothelial cells were treated with anti-STEAP4 prior to the addition of sera from patients with NPDR and edema. Providing strong evidence that STEAP4 impacts the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy by exacerbating oxidative stress in the diabetic retina.

There is lacking consensus on the role of STEAP4 in adipocytes and diabetes onset [

32,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. Opposing results of the impact of STEAP4 on insulin resistance and glucose intolerance in humans than in mice have been reported [

39,

43]. The mechanistic basis for these reported inhibitory and inductive roles of STEAP4 in diabetes onset remains unclear. Defining the impact of STEAP4 in diabetes onset, rather than its role in the onset of a diabetic complication (diabetic retinopathy) is beyond the scope of this study. Since there have been reported discrepancies between human results and Type II diabetic mice, we used the STZ-Type I diabetic mouse model to mechanistically examine our clinical finding. Thus, defining the role of STEAP4 in the development of diabetic retinopathy in STZ-diabetic mice removes the extrinsic factors that could impede the onset of diabetes; thus, halting the onset of diabetic retinopathy in wild-type diabetic mice.

Collectively, the results from the human ex vivo and murine in vivo studies reveal the relevance of our original discovery that levels of STEAP4 significantly increasing in correlation to the severity of diabetic retinopathy. Thus, suggesting that STEAP4 could be a clinically relevant biomarker for the progression of diabetic retinopathy, and a novel therapeutic target for the development of diabetic retinopathy.

Author Contributions

The authors contributions to this study are as follows: conceptualization, B.E.T., S.J.H., C.L., and P.R.T.; methodology, B.E.T., S.J.H., C.L., Z.T., K.B., and P.R.T.; validation, B.E.T., S.J.H., C.L., Z.T., K.B., and P.R.T.; formal analysis, B.E.T., S.J.H., C.L., Z.T., K.B., and P.R.T.; investigation, B.E.T., S.J.H., C.L., Z.T., K.B., and P.R.T.; resources, P.R.T.; data curation, B.E.T., S.J.H., C.L., Z.T., K.B., and P.R.T.; writing—original draft preparation, B.E.T., S.J.H., C.L., Z.T., K.B., and P.R.T.; writing—review and editing, P.R.T.; project administration, P.R.T.; and funding acquisition, P.R.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

STEAP4 expression in PBMC of non-diabetic and diabetic patients. Fold increase of STEAP4 expression in PBMC (n=15/group) from non-diabetic patients (grey), diabetics without retinopathy (Diabetic: green), and diabetics with non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR: blue) without and with diabetic macular edema (NPDR+DME: red). * = p < 0.01 calculated by 1-way nested ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc unpaired student t-test.

Figure 1.

STEAP4 expression in PBMC of non-diabetic and diabetic patients. Fold increase of STEAP4 expression in PBMC (n=15/group) from non-diabetic patients (grey), diabetics without retinopathy (Diabetic: green), and diabetics with non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR: blue) without and with diabetic macular edema (NPDR+DME: red). * = p < 0.01 calculated by 1-way nested ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc unpaired student t-test.

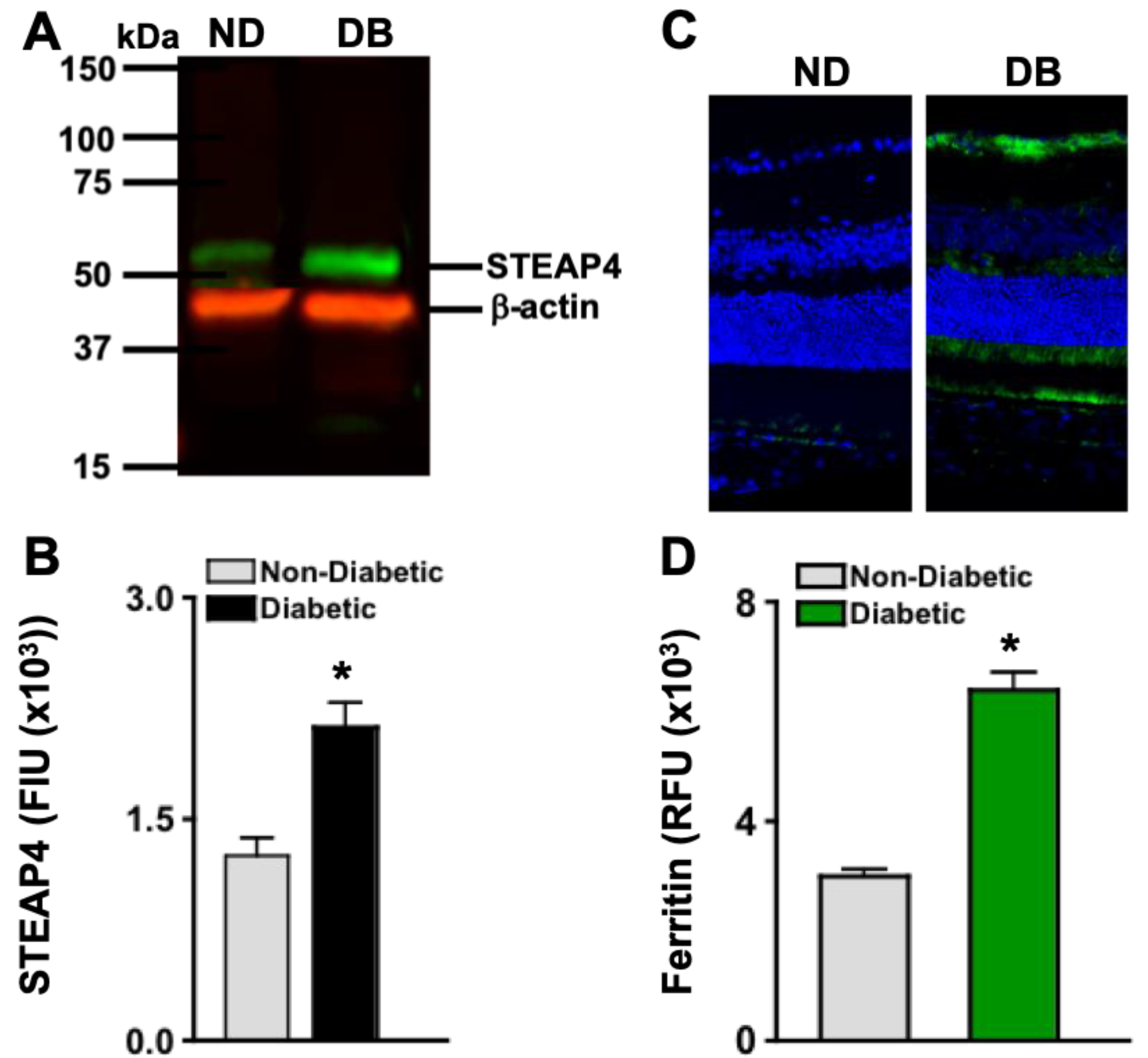

Figure 2.

STEAP4 and iron in the retinas of non-diabetic and diabetic mice. A) Representative immunoblot of STEAP4 (52 kDa: green) and β-actin (42 kDa: red) of protein lysates, and B) FIU (fluorescent intensity) quantification of all protein samples (n=3/group) from non-diabetic (grey) and diabetic (black) mice; 2-months post-diabetes. C) Representative images of ferritin (green) and DAPI (blue) stained retina cross sections of non-diabetic (ND) and diabetic (DB) mice. D) Metamorph quantification of relative ferritin fluorescence in all retinas examined (n=5/group) of non-diabetic (grey) and diabetic (green) mice; 2-months post diabetes. *=p< 0.01 per ANOVA and t-test.

Figure 2.

STEAP4 and iron in the retinas of non-diabetic and diabetic mice. A) Representative immunoblot of STEAP4 (52 kDa: green) and β-actin (42 kDa: red) of protein lysates, and B) FIU (fluorescent intensity) quantification of all protein samples (n=3/group) from non-diabetic (grey) and diabetic (black) mice; 2-months post-diabetes. C) Representative images of ferritin (green) and DAPI (blue) stained retina cross sections of non-diabetic (ND) and diabetic (DB) mice. D) Metamorph quantification of relative ferritin fluorescence in all retinas examined (n=5/group) of non-diabetic (grey) and diabetic (green) mice; 2-months post diabetes. *=p< 0.01 per ANOVA and t-test.

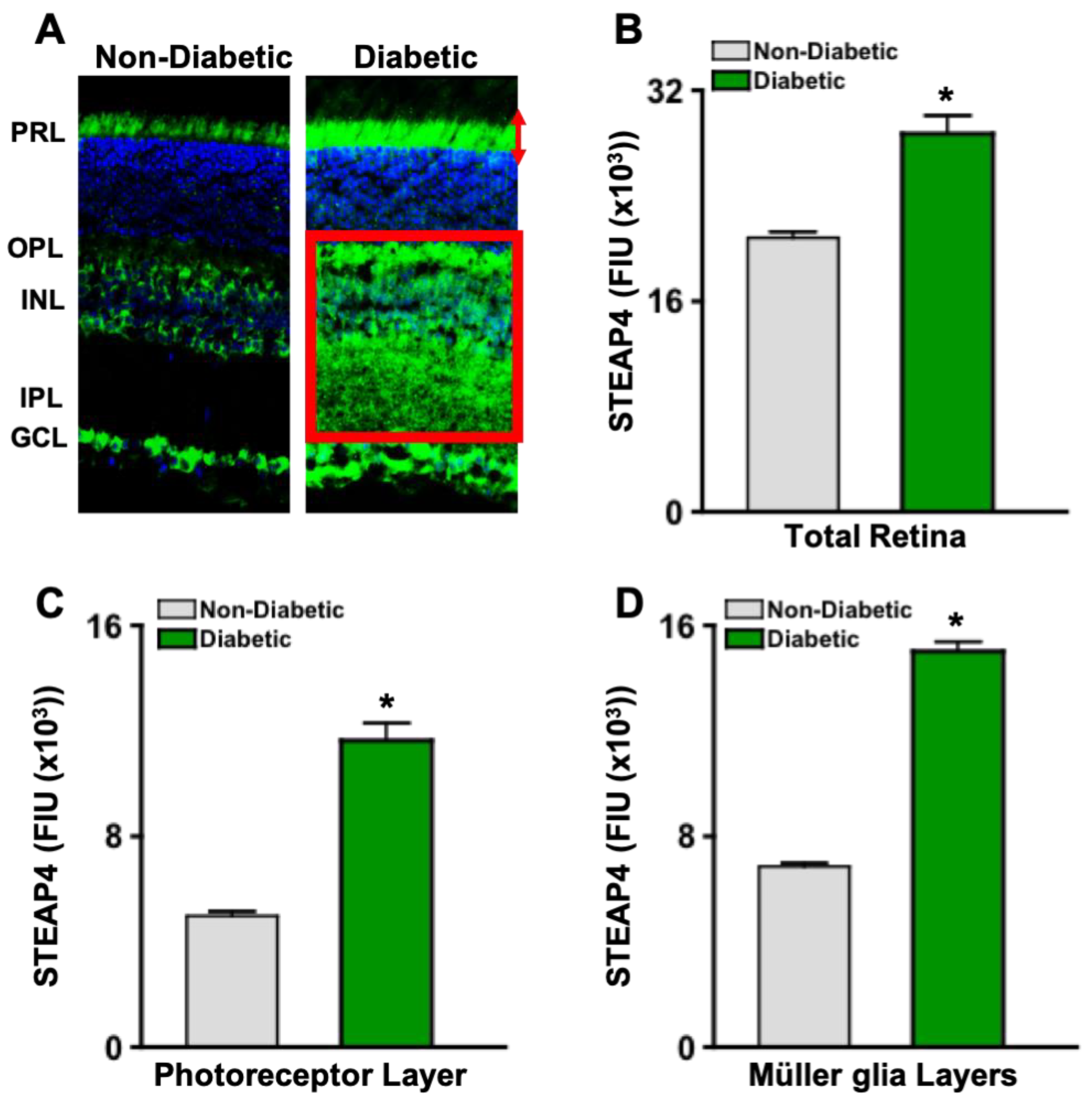

Figure 3.

STEAP4 in photoreceptor and Müller glia layers of murine retinas. A) Images of STEAP4 (green) and DAPI (blue) in 8 μM cross sections of retinas from non-diabetic and diabetic mice. STEAP4 in the photoreceptor layer is outlined by red arrows, and in the Müller glia layers is highlighted by a red box. Levels of STEAP4-fluorescence (FIU) in the total retina (B), photoreceptor layer (C), and retina layers where Müller glia reside (D) of non-diabetic (grey) and diabetic (green) mice (n=5/group); 2-months post-diabetes. *=p<0.01 per ANOVA and unpaired student t-test.

Figure 3.

STEAP4 in photoreceptor and Müller glia layers of murine retinas. A) Images of STEAP4 (green) and DAPI (blue) in 8 μM cross sections of retinas from non-diabetic and diabetic mice. STEAP4 in the photoreceptor layer is outlined by red arrows, and in the Müller glia layers is highlighted by a red box. Levels of STEAP4-fluorescence (FIU) in the total retina (B), photoreceptor layer (C), and retina layers where Müller glia reside (D) of non-diabetic (grey) and diabetic (green) mice (n=5/group); 2-months post-diabetes. *=p<0.01 per ANOVA and unpaired student t-test.

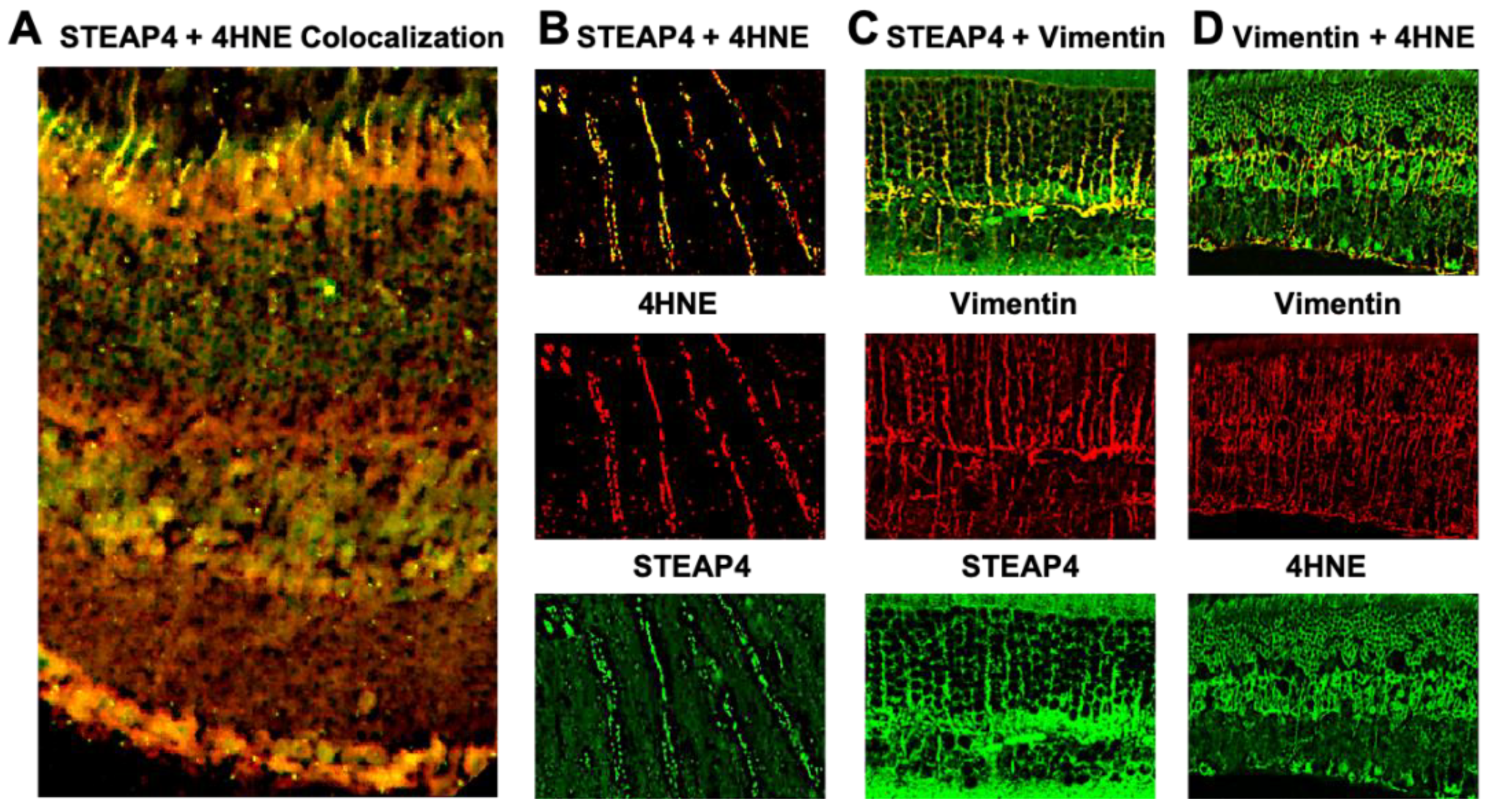

Figure 4.

STEAP4 and 4HNE in photoreceptors and Müller glia of diabetic mice. A) Widefield image of merged (yellow) STEAP4 (green) and 4HNE (red) in a retinal cross section from a diabetic mouse. B) Representative confocal images of photoreceptor outer segment, displaying STEAP4 (green) and 4HNE (red) colocalization (yellow). C) Confocal images of STEAP4 (green) colocalized in Vimentin (red) stained Müller glia. D) Confocal images of 4HNE (green) colocalization (yellow) in Vimentin (red) stained Müller glia. All images are representative of retina cross sections from diabetic mice analyzed (n=5) 2-months after diabetic conditions were confirmed.

Figure 4.

STEAP4 and 4HNE in photoreceptors and Müller glia of diabetic mice. A) Widefield image of merged (yellow) STEAP4 (green) and 4HNE (red) in a retinal cross section from a diabetic mouse. B) Representative confocal images of photoreceptor outer segment, displaying STEAP4 (green) and 4HNE (red) colocalization (yellow). C) Confocal images of STEAP4 (green) colocalized in Vimentin (red) stained Müller glia. D) Confocal images of 4HNE (green) colocalization (yellow) in Vimentin (red) stained Müller glia. All images are representative of retina cross sections from diabetic mice analyzed (n=5) 2-months after diabetic conditions were confirmed.

Figure 5.

ROS production in anti-STEAP4 treated photoreceptors and Müller glia. Müller glia (A) (n=6) and (B) 661W photoreceptor-like cone cells (n=6) were incubated in euglycemic conditioned media containing 5mM of glucose (white), or hyperglycemic conditioned media containing 25mM of glucose without (grey) or with: 1 μg (blue), 2 μg (red), or 5 μg (black) of anti-STEAP4 for 18h. Human Müller glia (A) and mouse 661W cells (B) were collected and incubated with H2CFDA (ROS indicator) for flow cytometry quantification of ROS. * =p < 0.01, which was equated by 2-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc unpaired student t-test. .

Figure 5.

ROS production in anti-STEAP4 treated photoreceptors and Müller glia. Müller glia (A) (n=6) and (B) 661W photoreceptor-like cone cells (n=6) were incubated in euglycemic conditioned media containing 5mM of glucose (white), or hyperglycemic conditioned media containing 25mM of glucose without (grey) or with: 1 μg (blue), 2 μg (red), or 5 μg (black) of anti-STEAP4 for 18h. Human Müller glia (A) and mouse 661W cells (B) were collected and incubated with H2CFDA (ROS indicator) for flow cytometry quantification of ROS. * =p < 0.01, which was equated by 2-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc unpaired student t-test. .

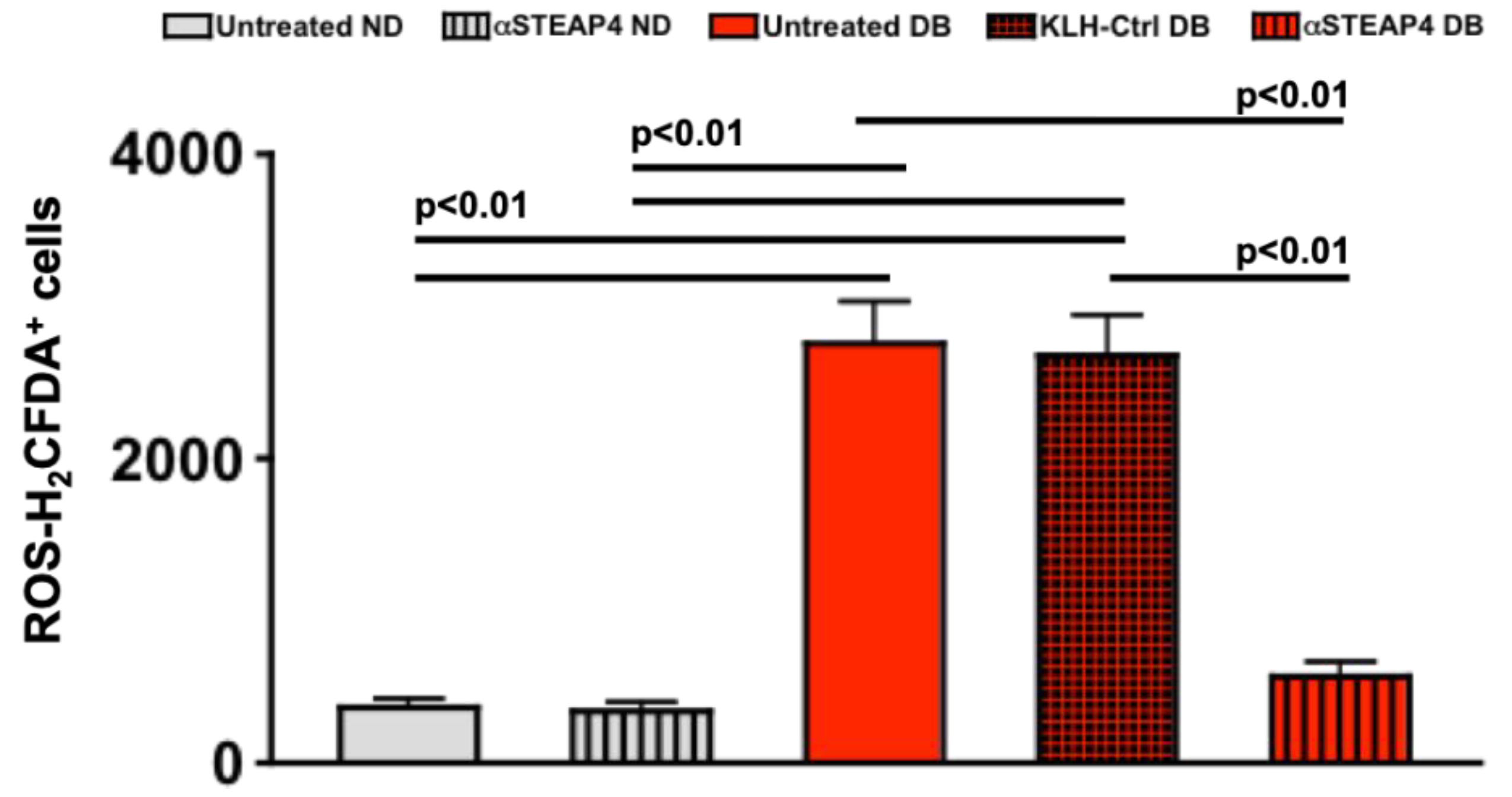

Figure 6.

ROS in anti-STEAP4 treated murine retinas. Non-diabetic (ND) and diabetic (DB) mice remained untreated or received one intravitreal injection of 5 μg of anti-STEAP4+KLH; 1-week after diabetes was confirmed. Isolated retina cells were incubated with H2CFDA for flow cytometry analysis of ROS in retinas of untreated non-diabetic (grey), anti-STEAP4 treated non-diabetic (grey striped), untreated diabetic (red), KLH treated diabetic controls (black and red checkered), and anti-STEAP4 treated diabetic (red striped) C57BL/6 mice (n=5/group); 2-months post-diabetes. p-values were equated using 2-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc unpaired student t-tests.

Figure 6.

ROS in anti-STEAP4 treated murine retinas. Non-diabetic (ND) and diabetic (DB) mice remained untreated or received one intravitreal injection of 5 μg of anti-STEAP4+KLH; 1-week after diabetes was confirmed. Isolated retina cells were incubated with H2CFDA for flow cytometry analysis of ROS in retinas of untreated non-diabetic (grey), anti-STEAP4 treated non-diabetic (grey striped), untreated diabetic (red), KLH treated diabetic controls (black and red checkered), and anti-STEAP4 treated diabetic (red striped) C57BL/6 mice (n=5/group); 2-months post-diabetes. p-values were equated using 2-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc unpaired student t-tests.

Figure 7.

Levels of Occludin in protein lysates from murine retinal vasculature. Representative WES gel (A) and electropherogram (B) of Occludin (65 kDa) in protein lysates of retinal vasculature of untreated (DB CTRL: blue) and anti-STEAP4 treated (αSTEAP: red) diabetic mice. C) Occludin quantifications in all protein lysate samples (n=5/group) analyzed from retinas of untreated (blue) and anti-STEAP4 treated (red) diabetic mice; 2-months post-diabetes. * = p < 0.01 per 2-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc unpaired student t-test analyses. .

Figure 7.

Levels of Occludin in protein lysates from murine retinal vasculature. Representative WES gel (A) and electropherogram (B) of Occludin (65 kDa) in protein lysates of retinal vasculature of untreated (DB CTRL: blue) and anti-STEAP4 treated (αSTEAP: red) diabetic mice. C) Occludin quantifications in all protein lysate samples (n=5/group) analyzed from retinas of untreated (blue) and anti-STEAP4 treated (red) diabetic mice; 2-months post-diabetes. * = p < 0.01 per 2-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-hoc unpaired student t-test analyses. .

Figure 8.

Human retina endothelial cell death in cells cultured with patient sera. Untreated (black) or anti-STEAP4 treated (red) hREC (1 x 106) were cultured with sera of non-diabetics (ND) or sera of patients with NPDR and diabetic macular edema (DME) for 18h. Cells were collected and incubated with 7-AAD for flow cytometry analysis of hREC cell death (n=15/group). p-value was calculated using 2-way ANOVA analysis and Tukey’s post-hoc unpaired student t-tests. .

Figure 8.

Human retina endothelial cell death in cells cultured with patient sera. Untreated (black) or anti-STEAP4 treated (red) hREC (1 x 106) were cultured with sera of non-diabetics (ND) or sera of patients with NPDR and diabetic macular edema (DME) for 18h. Cells were collected and incubated with 7-AAD for flow cytometry analysis of hREC cell death (n=15/group). p-value was calculated using 2-way ANOVA analysis and Tukey’s post-hoc unpaired student t-tests. .

Table 1.

Clinical Data of Non-Diabetic and Diabetic Patient Donors.

Table 1.

Clinical Data of Non-Diabetic and Diabetic Patient Donors.

| Group |

HbA1C (%) |

Cholesterol (mg/dL) |

NFBG (mg/dL) |

| Non-Diabetic |

5.53 + 0.12 |

135.08 + 22.61 |

90.27 + 13.54 |

| Diabetic without Retinopathy |

7.78 + 0.85 * |

136.53 + 23.83 |

203.33 + 23.83 * |

| NPDR |

7.59 + 1.49 * |

130.07 + 21.72 |

201.27 + 24.13 * |

| NPDR+DME |

9.39 + 1.89 * |

135.21 + 20.21 |

224.07 + 22.79 * |

Table 2.

Clinical data of non-diabetic and STZ-diabetic mice receiving anti-STEAP4 treatment.

Table 2.

Clinical data of non-diabetic and STZ-diabetic mice receiving anti-STEAP4 treatment.

| Group |

HbA1C (%) |

Body Weight (g) |

| Untreated Non-Diabetic |

3.91 + 0.26 |

35.22 + 4.18 |

| Untreated Diabetic |

10.51 + 2.02 * |

27.56 + 2.13 * |

| αSTEAP4-Treated Non-Diabetic |

3.82 + 0.25 |

36.01 + 4.42 |

| αSTEAP4-Treated Diabetic |

11.05 + 1.55 * |

26.51 + 1.01 * |

| KLH-Treated Non-Diabetic |

3.89 + 0.29 |

35.98 + 4.07 |

| KLH-Treated Diabetic |

10.85 + 1.11 * |

27.09 + 2.17 * |