Submitted:

17 December 2024

Posted:

18 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction: The Where, When, and How of DNA Replication

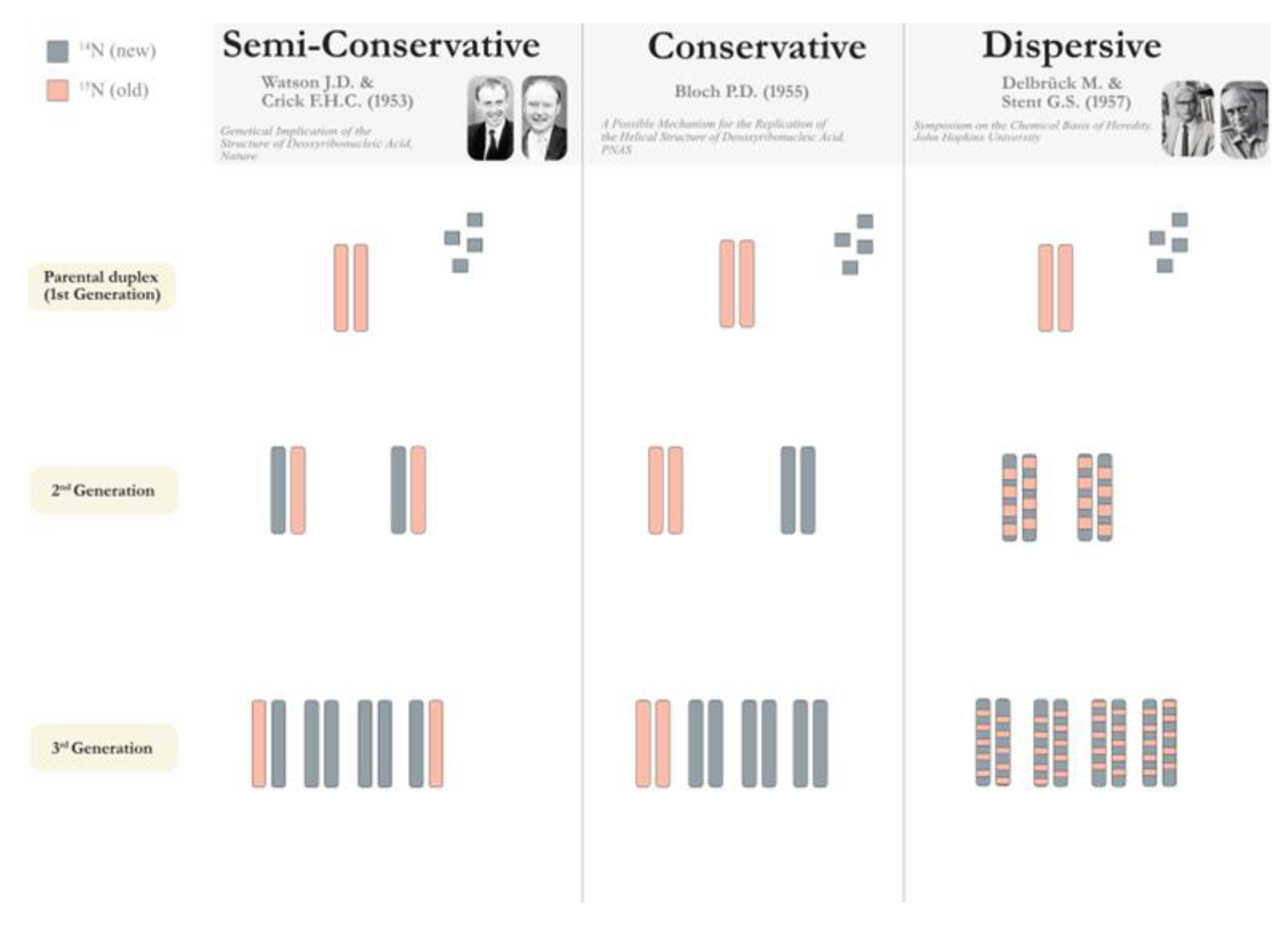

1.1. The DNA Replication Problem

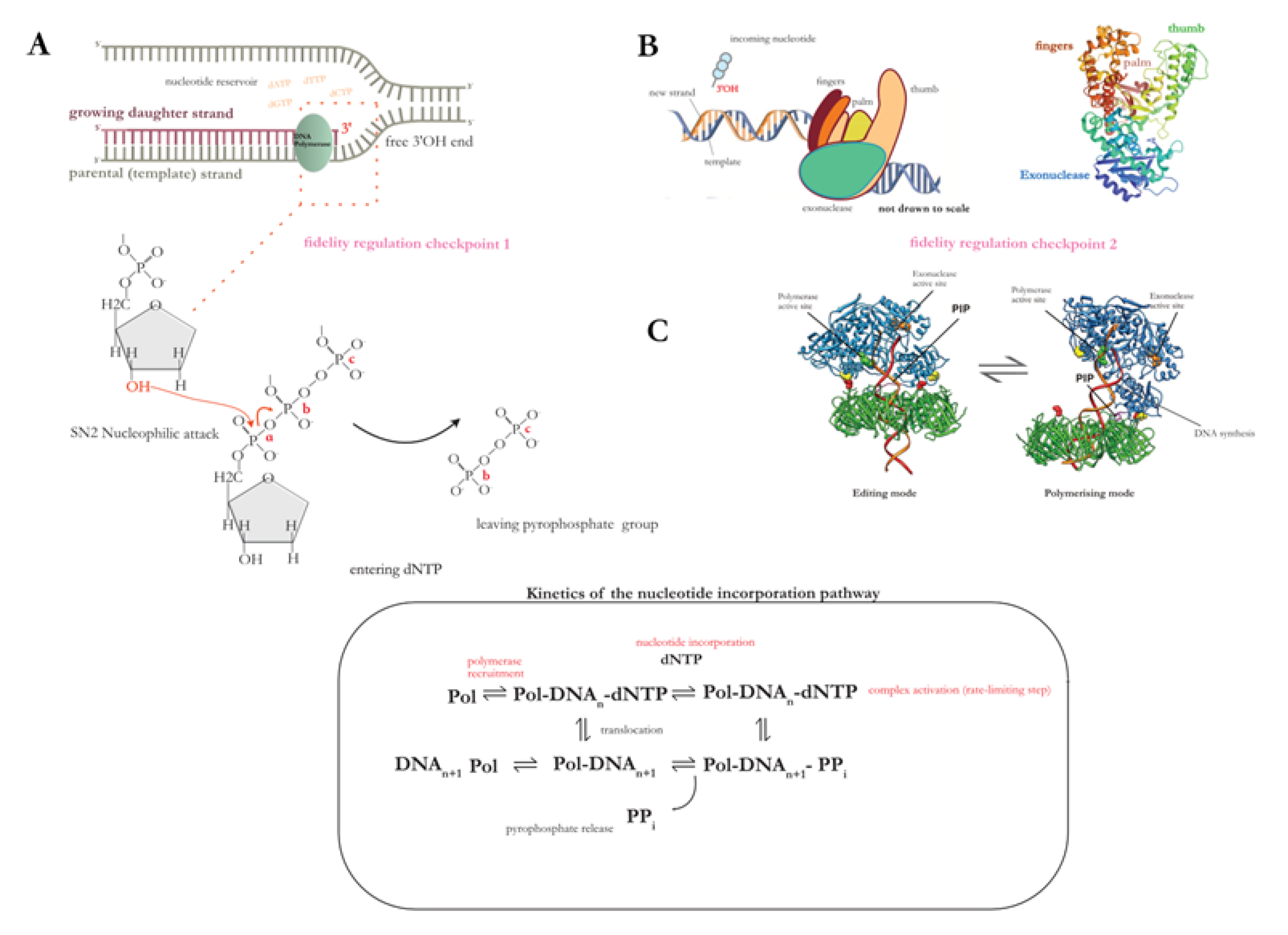

1.2. The Polymerase Puzzle

- (1)

- Is the synthesised DNA strand identical to its template?

- (2)

- Does replication proceed in a template directed manner as predicted by Watson and Crick, catalysed by DNA polymerase?

“exact copies can be made from it so that this information can be used again and elsewhere in time and space.”

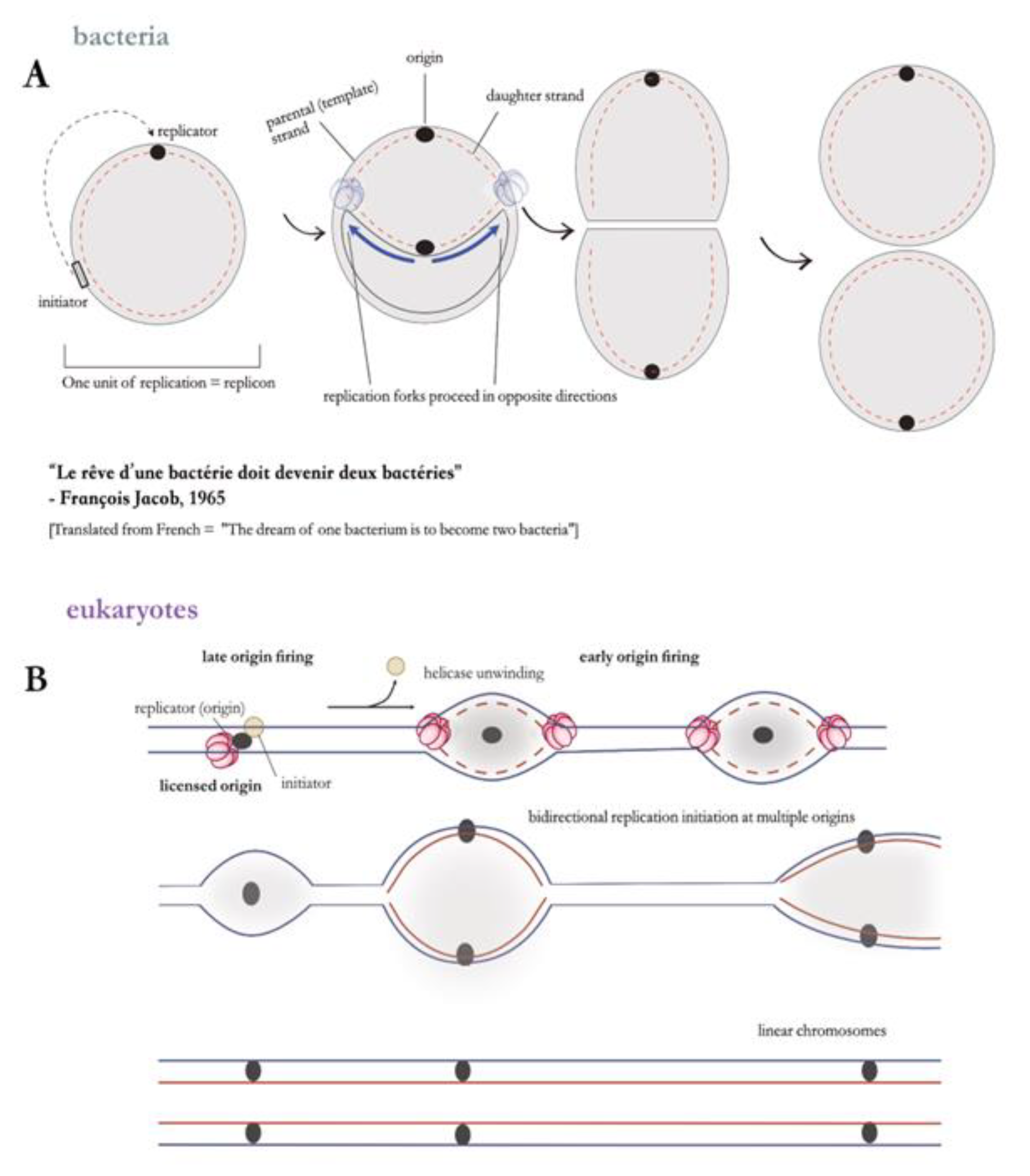

2. The Replicon Model: Leading Paradigm for the Study of DNA Replication

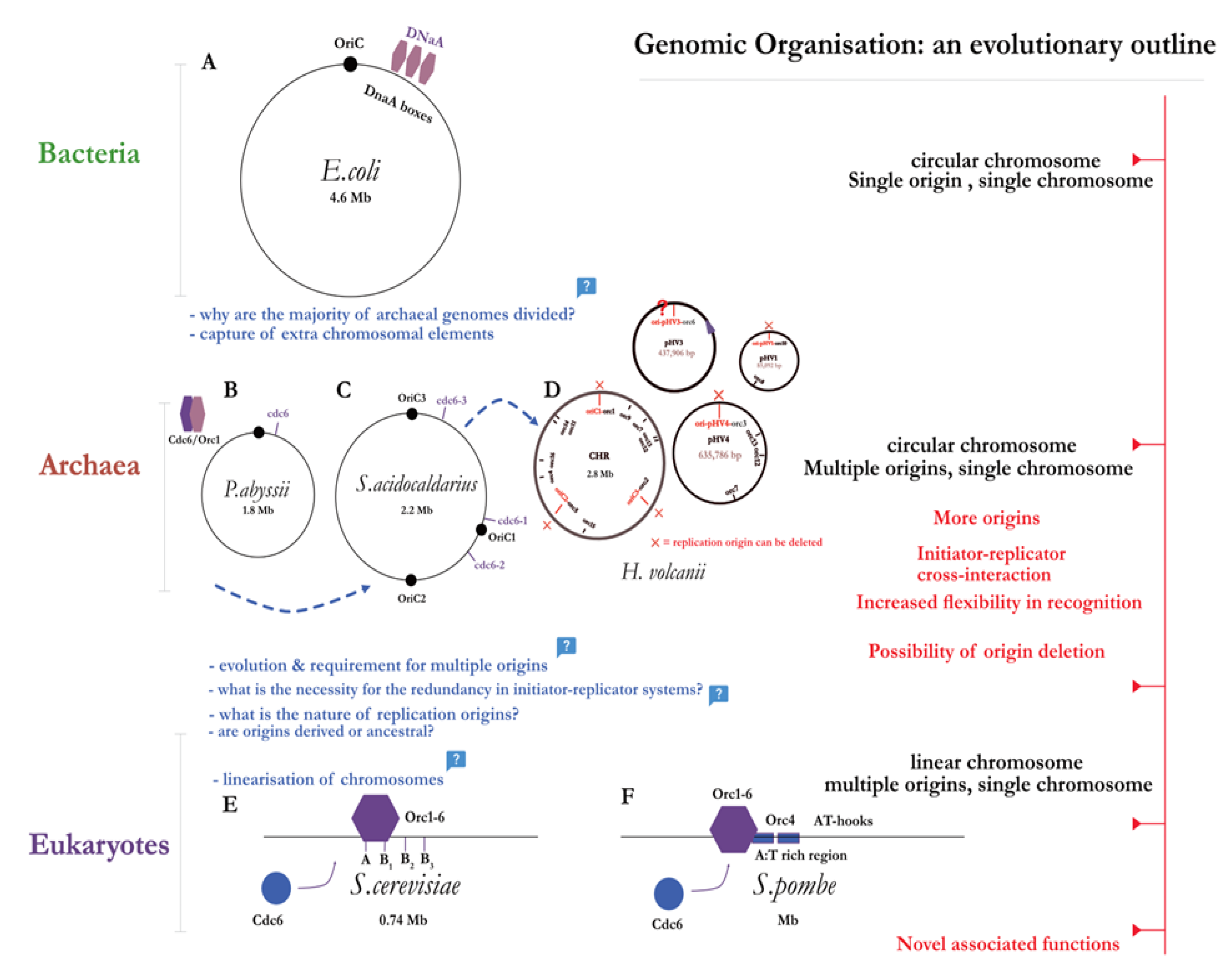

3. The Divided Genome: Nature’s Riddle

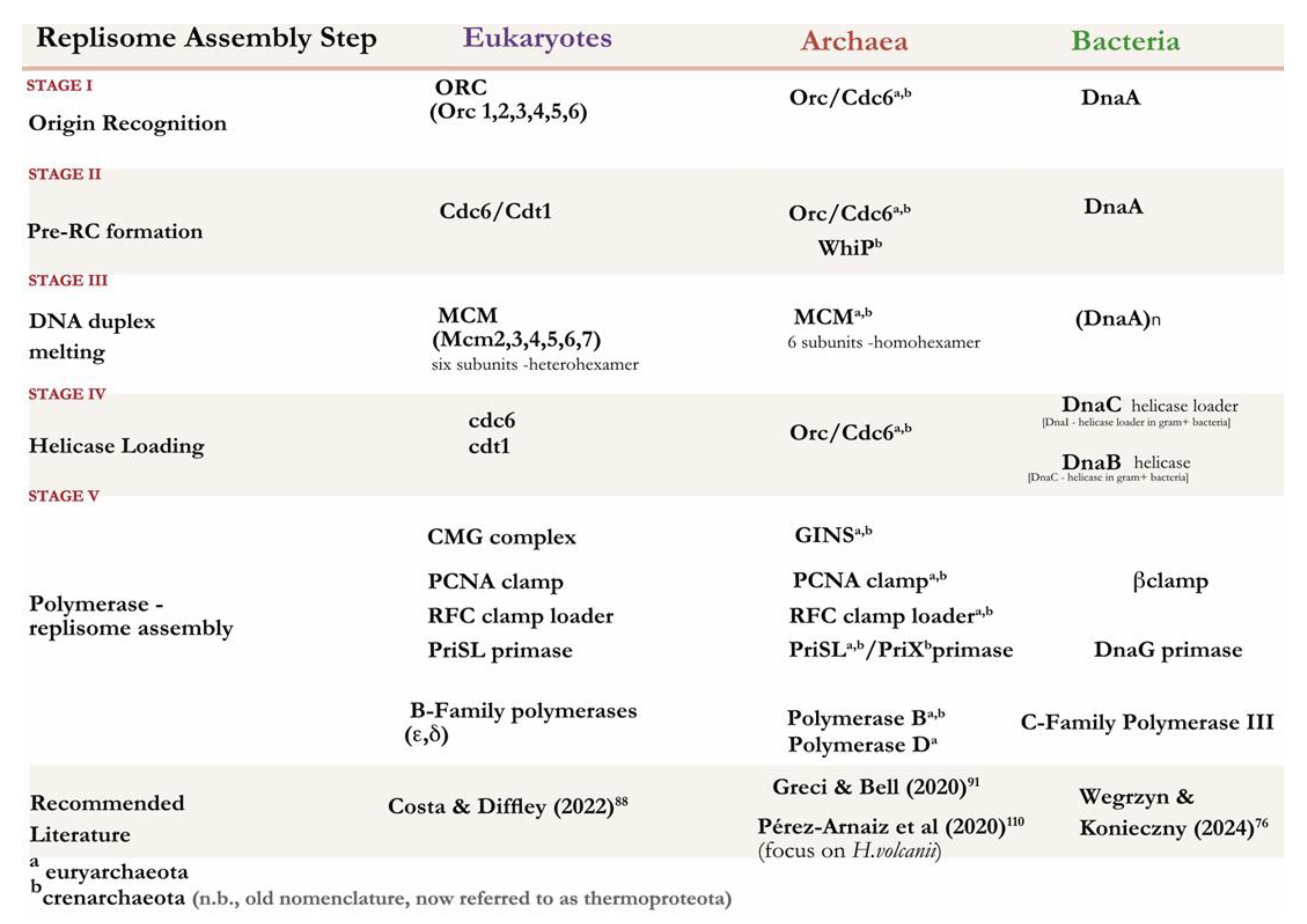

3.1. The Diversity of Replication Factors

3.2. Many Origins, One Chromosome: Time to Revisit the Single Replicon Model?

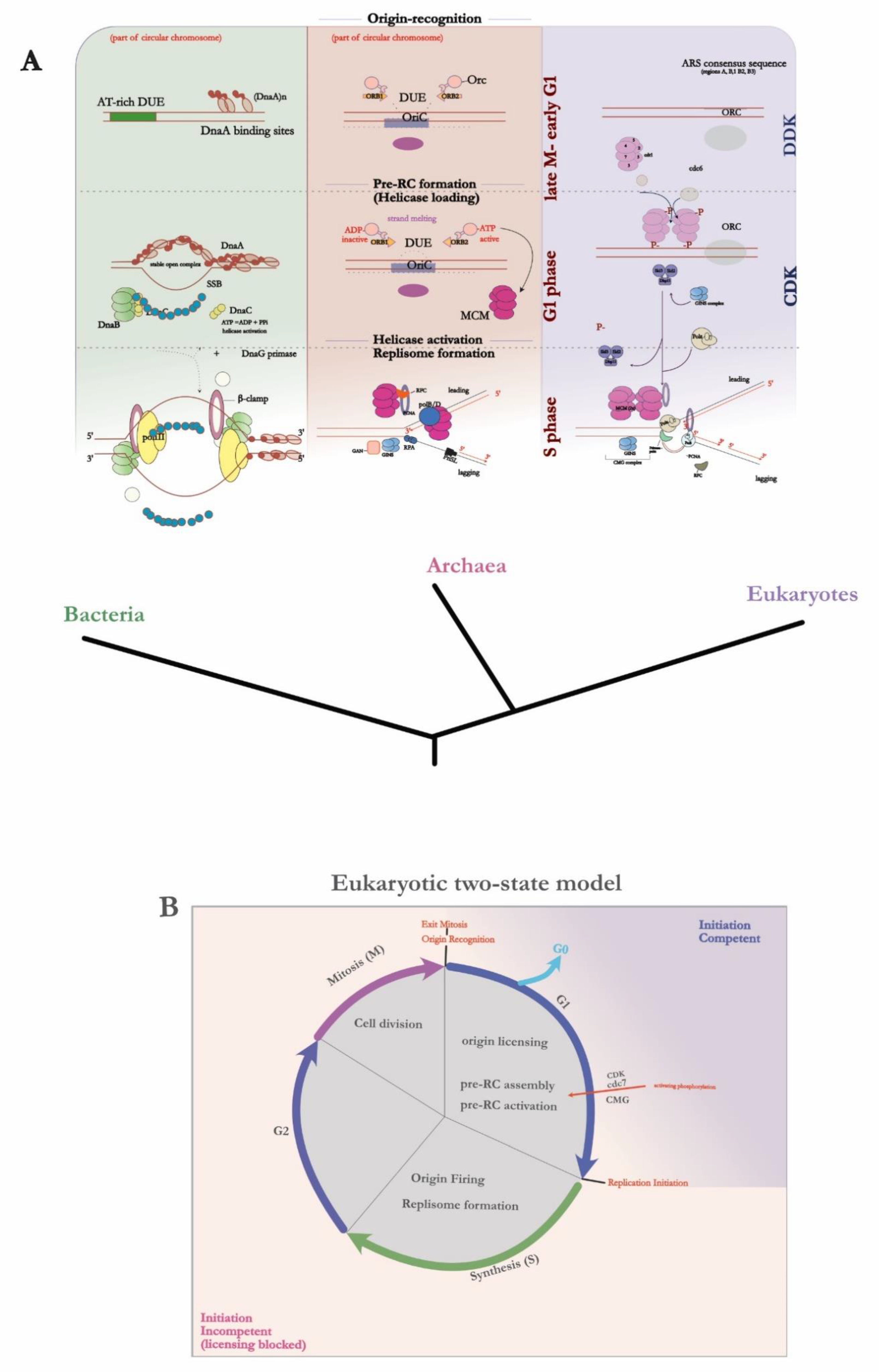

4. Where Do We Start? DNA Replication Initiation across the Three Domains of Life

|

4.1. Bacteria

4.2. Eukaryotes

4.3. Archaea

5. DNA Replication & Recombination: A Dynamic Interplay

5.1. Adding a Level of Complexity: The Assymetry of DNA Replication

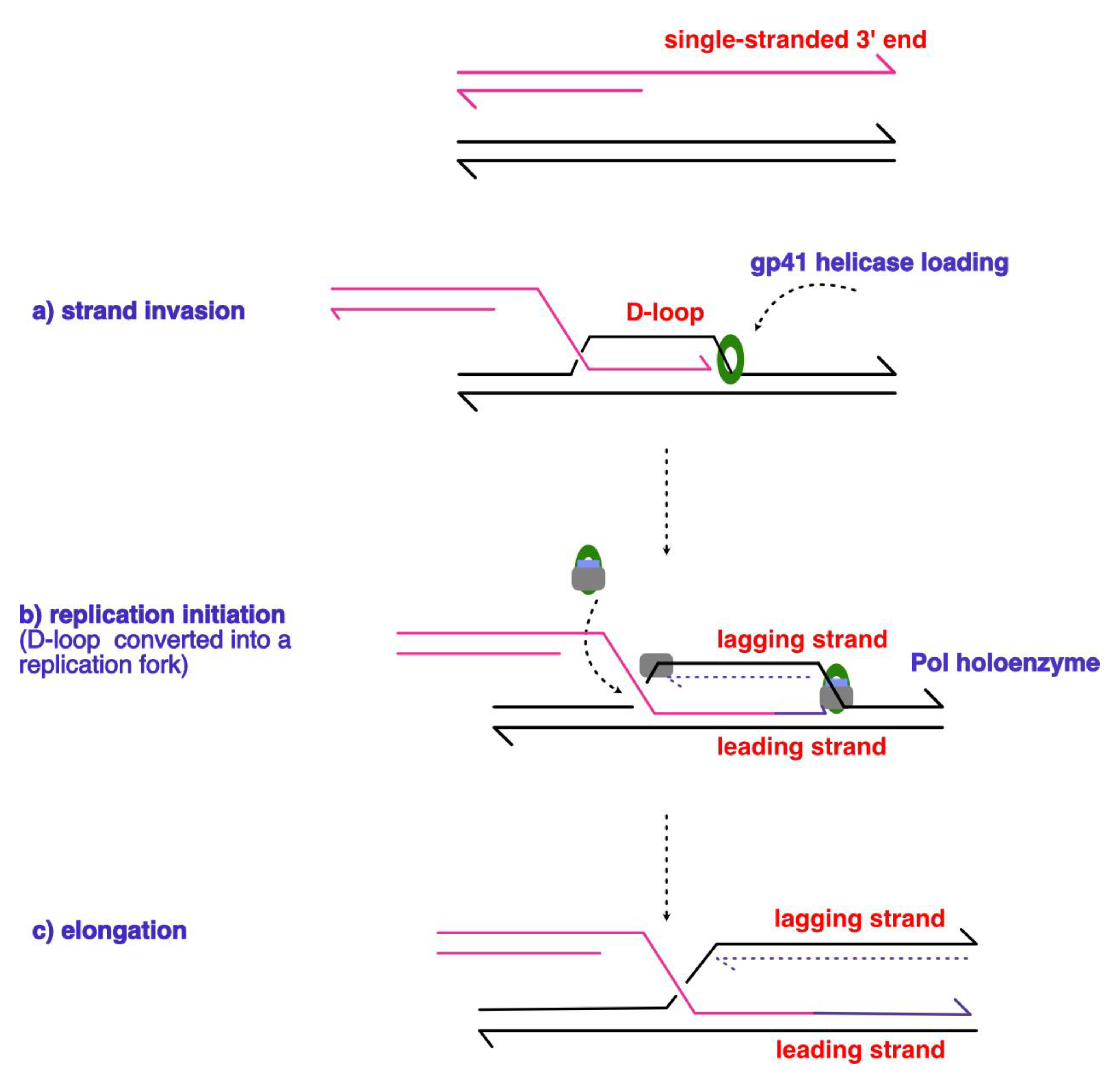

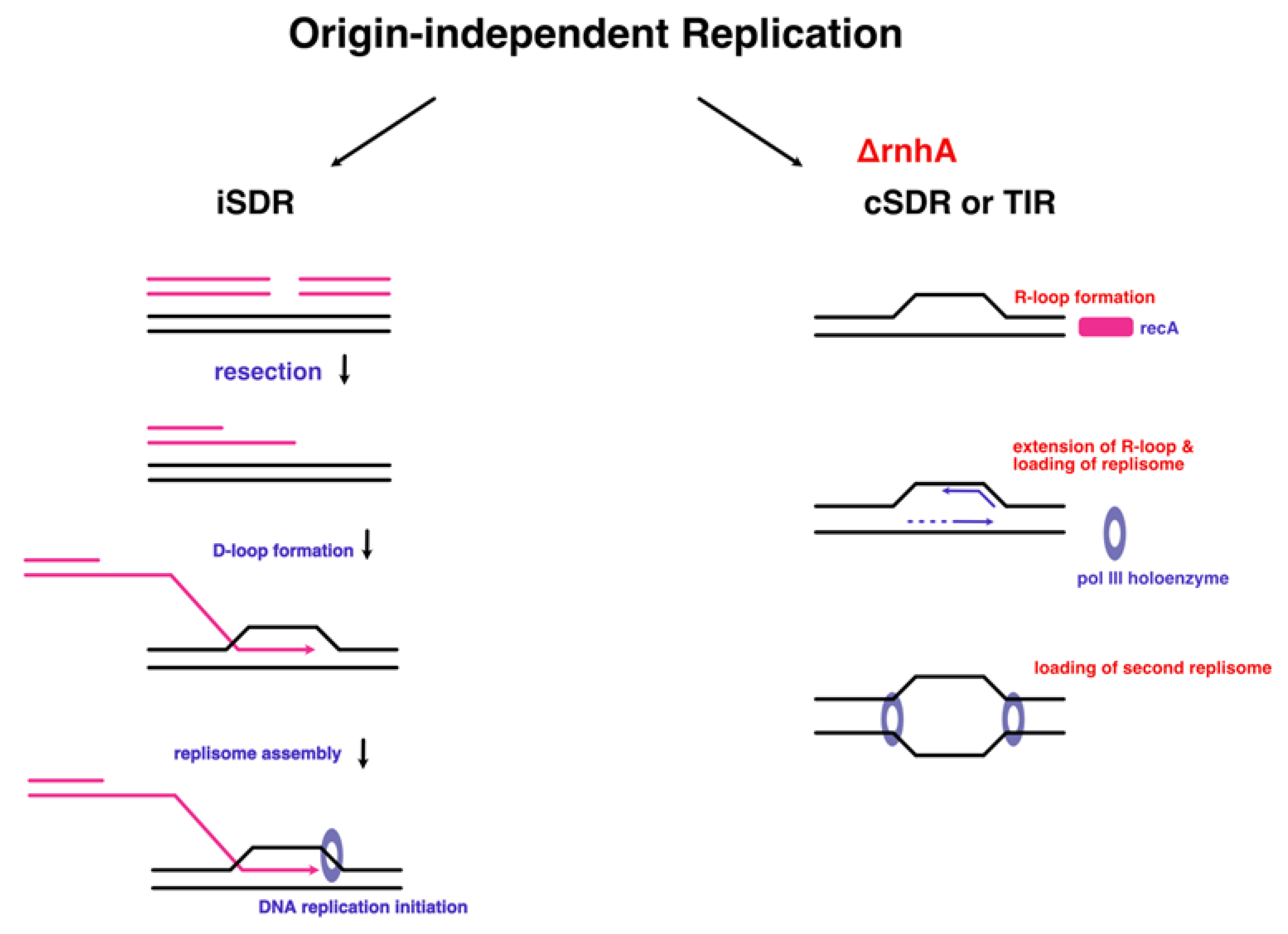

6. Recombination Dependent Replication

6.1. Clue No.1: Lessons from Viral Models

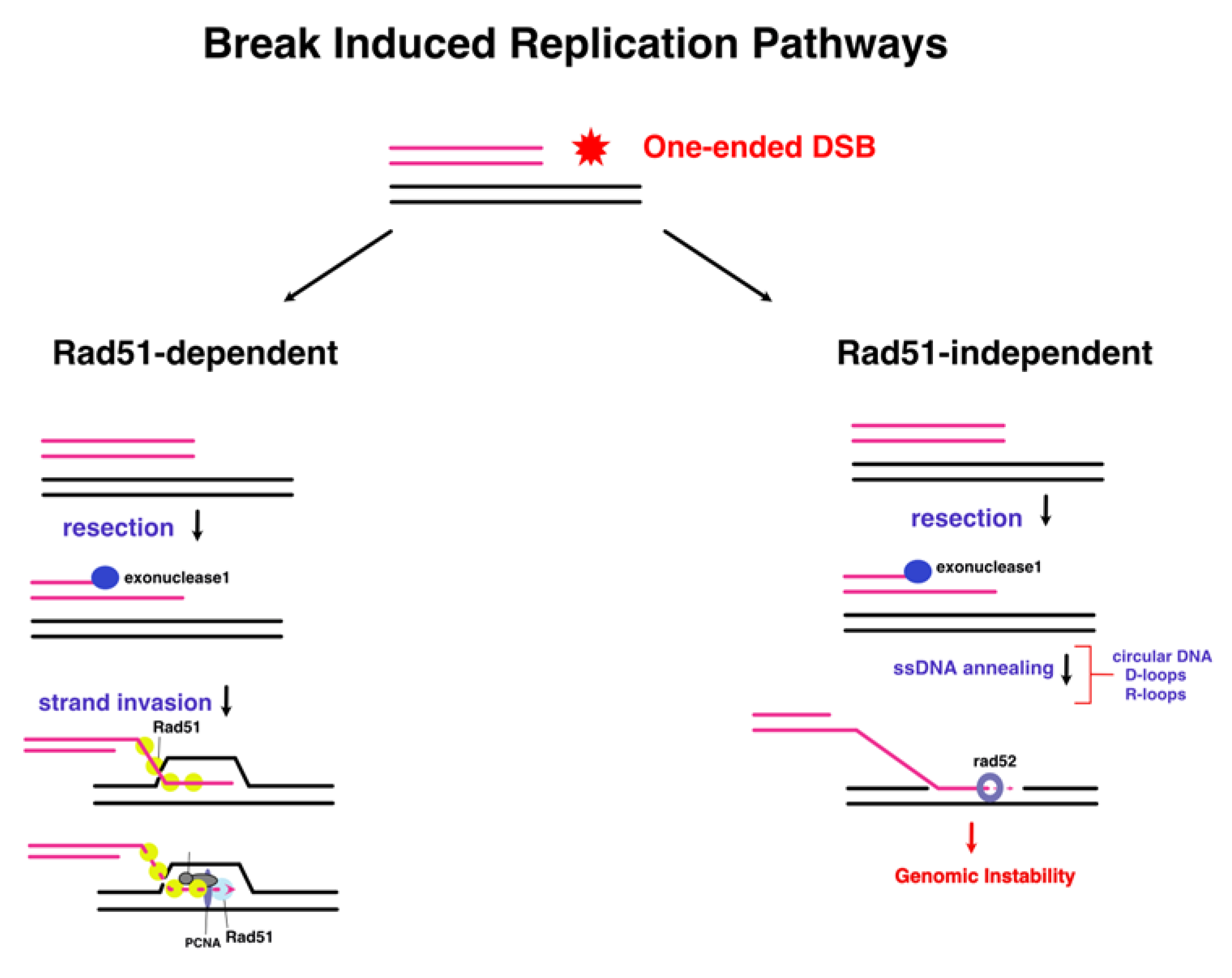

6.2. Clue No.2: Break-Induced DNA Replication in Eukaryotes

6.3. Clue No.3: Origin-Independent Replication Initiation in Bacteria and Archaea

7. Conclusions: The Archaeal Domain as a Window into Our Evolutionary Past

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gaillard, H.; García-Muse, T.; Aguilera, A. Replication Stress and Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 276–289. [CrossRef]

- Avery, O.T.; Macleod, C.M.; McCarthy, M. STUDIES ON THE CHEMICAL NATURE OF THE SUBSTANCE INDUCING TRANSFORMATION OF PNEUMOCOCCAL TYPES. J Exp Med 1944, 79, 137–158.

- De Silva, R.T.; Abdul-Halim, M.F.; Pittrich, D.A.; Brown, H.J.; Pohlschroder, M.; Duggin, I.G. Improved Growth and Morphological Plasticity of Haloferax Volcanii. Microbiology 2021, 167, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Stent, G.S. Prematurity and Uniqueness in Scientific Discovery. Sci. Am. 1972, 227, 84–93.

- Mirsky, A.E.; Pollister, A.W. CHROMOSIN, A DESOXYRIBOSE NUCLEOPROTEIN COMPLEX OF THE CELL NUCLEUS. J. Gen. Physiol. 1946, 30, 117–148. [CrossRef]

- Chargaff, E. Chemical Specificity of Nucleic Acids and Mechanism of Their Enzymatic Degradation. Experientia 1950, 6, 201–209. [CrossRef]

- Levene, P.A.; La Forge, F.B. On Chondrosamine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1915, 1, 190–191. [CrossRef]

- Hershey, A.D.; Chase, M. INDEPENDENT FUNCTIONS OF VIRAL PROTEIN AND NUCLEIC ACID IN GROWTH OF BACTERIOPHAGE. J. Gen. Physiol. 1952, 36, 39–56.

- Wyatt, H.V. How History Has Blended. Nature 1974, 249, 803–805.

- Watson, J.D.; Crick, F.H.C. Genetical Implications of the Structure of Deoxyribonucleic Acid. Nature 1953, 171, 964–967.

- Franklin, R.; Gosling, R. Molecular Configuration in Sodium Thymonucleate. Nature 1953, 171, 740–741.

- Wilkins, M.; Stokes, A.; Wilson, H. Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: Molecular Structure of Deoxypentose Nucleic Acids. Nature 1953, 171, 738–740.

- Pauling, L.; Corey, R.B. A Proposed Structure For The Nucleic Acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1953, 39, 84–97. [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.D.; Crick, F.H.C. Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids; a Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid. Nature 1953, 171, 737–738.

- Bloch, D.P. A POSSIBLE MECHANISM FOR THE REPLICATION OF THE HELICAL STRUCTURE OF DESOXYRIBONUCLEIC ACID. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1955, 41, 1058–1064. [CrossRef]

- Meselson, M.; Stahl, F.W. THE REPLICATION OF DNA IN ESCHERICHIA COLI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1958, 44, 671–682.

- Holmes, F.L. The DNA Replication Problem, 1953–1958. Cell 1998, 23, 117–120.

- Lehman, I.R.; Bessman, M.J.; Simms, E.S.; Kornberg, A. Enzymatic Synthesis of Deoxyribonucleic Acid. J. Biol. Chem. 1958, 233, 163–170. [CrossRef]

- Bessman, M.J.; Lehman, I.R.; Simms, E.S.; Kornberg, A. Enzymatic Synthesis of Deoxyribonucleic Acid. J. Biol. Chem. 1958, 233, 171–177. [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, I.; Kornberg, A.; Simms, E.S. ENZYMATIC SYNTHESES OF PYRIMIDINE AND PURINE NUCLEOTIDES. II.1 OROTIDINE-5’-PHOSPHATE PYROPHOSPHORYLASE AND DECARBOXYLASE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1954, 76.

- Cori, G.T.; Cori, C.F. CRYSTALLINE MUSCLE PHOSPHORYLASE. J. Biol. Chem. 1943, 151, 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Brutlag, D.; Kornberg, A. Enzymatic Synthesis of Deoxyribonucleic Acid. J. Biol. Chem. 1972, 247, 241–248. [CrossRef]

- Delarue, M.; Poch, O.; Tordo, N.; Moras, D.; Argos, P. An Attempt to Unify the Structure of Polymerases. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 1990, 3, 461–467. [CrossRef]

- Joyce, C.M.; Steitz, T.A. FUNCTION AND STRUCTURE RELATIONSHIPS IN DNA POLYMERASES. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1994, 63, 777–822.

- Bebenek, K.; Kunkel, T.A. Functions of DNA Polymerases. In Advances in Protein Chemistry; Elsevier, 2004; Vol. 69, pp. 137–165 ISBN 978-0-12-034269-3.

- Braithwaite, D.K.; Ito, J. Compilation, Alignment, and Phylogenetic Relationships of DNA Polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993, 21, 787–802. [CrossRef]

- Beese, L.S.; Derbyshire, V.; Steitz, T.A. Structure of DNA Polymerase I Klenow Fragment Bound to Duplex DNA. Science 1993, 260, 352–355. [CrossRef]

- Morin, J.A.; Cao, F.J.; Lázaro, J.M.; Arias-Gonzalez, J.R.; Valpuesta, J.M.; Carrascosa, J.L.; Salas, M.; Ibarra, B. Active DNA Unwinding Dynamics during Processive DNA Replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 8115–8120. [CrossRef]

- Bérut, A.; Arakelyan, A.; Petrosyan, A.; Ciliberto, S.; Dillenschneider, R.; Lutz, E. Experimental Verification of Landauer’s Principle Linking Information and Thermodynamics. Nature 2012, 483, 187–189. [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, J.; Nozawa, Y. Self-Reproducing System Can Behave as Maxwell’s Demon: Theoretical Illustration under Prebiotic Conditions. J. Theor. Biol. 1998, 194, 205–221. [CrossRef]

- Forterre, P.; Filée, J.; Myllykallio, H. Origin and Evolution of DNA and DNA Replication Machineries. In The Genetic Code and the Origin of Life; Springer US: Boston, MA, 2004; pp. 145–168 ISBN 978-0-306-47843-7.

- Rothwell, P.J.; Waksman, G. Structure and Mechanism of DNA Polymerases. In Advances in Protein Chemistry; Elsevier, 2005; Vol. 71, pp. 401–440 ISBN 978-0-12-034271-6.

- Steitz, T.A. DNA- and RNA-Dependent DNA Polymerases. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1993, 3, 31–38.

- Bębenek, A.; Ziuzia-Graczyk, I. Fidelity of DNA Replication—a Matter of Proofreading. Curr. Genet. 2018, 64, 985–996. [CrossRef]

- Ekundayo, B.; Bleichert, F. Origins of DNA Replication. PLOS Genet. 2019, 15, e1008320. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, F.; Monod, J. Genetic Regulatory Mechanisms in the Synthesis of Proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1961, 3, 318–356.

- Ryter, A.; Hirota, Y.; Jacob, F. DNA-Membrane Complex and Nuclear Segregation in Bacteria. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1968, 33, 669–676. [CrossRef]

- Morange, M. What History Tells Us XXXI. The Replicon Model: Between Molecular Biology and Molecular Cell Biology. J. Biosci. 2013, 38, 225–227. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, F.; Brenner, S.; Cuzin, F. On the Regulation of DNA Replication in Bacteria. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1963, 28, 329–348. [CrossRef]

- Huberman, J.A.; Riggs, A.D. On the Mechanism of DNA Replication in Mammalian Chromosomes. J. Mol. Biol. 1968, 32, 327–341. [CrossRef]

- Novick, R.P. Plasmid Incompatibility. Microbiol. Rev. 1987, 51, 381–395.

- Kohiyama, M.; Hiraga, S.; Matic, I.; Radman, M. Bacterial Sex: Playing Voyeurs 50 Years Later. Science 2003, 301, 802–803. [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, S.; Hirota, Y. Cloning and Mapping of the Replication Origin of Escherichia Coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1977, 74, 5458–5462. [CrossRef]

- Mackiewicz, P. Where Does Bacterial Replication Start? Rules for Predicting the oriC Region. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 3781–3791. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, T.; Yoshinaga, K.; Lother, H.; Messer, W. Purification of the E. Coli dnaA Gene Product. EMBO J. 1982, 1, 1545–1549. [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M.Q.; Yoshikawa, H. Structure of the dnaA Region of Pseudomonas Putida: Conservation among Three Bacteria, Bacillus Subtilis, Escherichia Coil and P. Putida.

- Chan, C.S.; Tye, B.K. Autonomously Replicating Sequences in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1980, 77, 6329–6333. [CrossRef]

- Broach, J.R.; Li, Y.-Y.; Feldman, J.; Jayaram, M.; Abraham, J.; Nasmyth, K.A.; Hicks, J.B. Localization and Sequence Analysis of Yeast Origins of DNA Replication. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 1983, 47, 1165–1173. [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.P.; Stillman, B. ATP-Dependent Recognition of Eukaryotic Origins of DNA Replication by a Multiprotein Complex. Nature 1992, 357, 128–134.

- Gavin, K.A.; Hidaka, M.; Stillman, B. Conserved Initiator Proteins in Eukaryotes. Science 1995, 270, 1667–1671. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.H. Increase in DNA Replication Sites in Cells Held at the Beginning of S Phase. Chromosoma 1977, 62, 291–300. [CrossRef]

- Hamlin, J.L.; Mesner, L.D.; Lar, O.; Torres, R.; Chodaparambil, S.V.; Wang, L. A Revisionist Replicon Model for Higher Eukaryotic Genomes. J. Cell. Biochem. 2008, 105, 321–329. [CrossRef]

- diCenzo, G.C.; Finan, T.M. The Divided Bacterial Genome: Structure, Function, and Evolution. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2017, 81, e00019-17. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.W.; Lower, R.P.J.; Kim, N.K.D.; Young, J.P.W. Introducing the Bacterial ‘Chromid’: Not a Chromosome, Not a Plasmid. Trends Microbiol. 2010, 18, 141–148. [CrossRef]

- Krawiec, S.; Riley, M. Organization of the Bacterial Chromosome. MICROBIOL REV 1990, 54.

- Suwanto, A.; Kaplan, S. Physical and Genetic Mapping of the Rhodobacter Sphaeroides 2.4.1 Genome: Presence of Two Unique Circular Chromosomes. J BACTERIOL 1989, 171.

- Woese, C.R.; Fox, G.E. Phylogenetic Structure of the Prokaryotic Domain: The Primary Kingdoms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1977, 74, 5088–5090. [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Beard, W.A.; Pedersen, L.G.; Wilson, S.H. Structural Comparison of DNA Polymerase Architecture Suggests a Nucleotide Gateway to the Polymerase Active Site. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2759–2774. [CrossRef]

- Myllykallio, H.; Lopez, P.; López-Garcı́a, P.; Heilig, R.; Saurin, W.; Zivanovic, Y.; Philippe, H.; Forterre, P. Bacterial Mode of Replication with Eukaryotic-Like Machinery in a Hyperthermophilic Archaeon. Science 2000, 288, 2212–2215. [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, F.; Forterre, P.; Ishino, Y.; Myllykallio, H. In Vivo Interactions of Archaeal Cdc6/Orc1 and Minichromosome Maintenance Proteins with the Replication Origin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001, 98, 11152–11157. [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, F.; Norais, C.; Forterre, P.; Myllykallio, H. Identification of Short ‘Eukaryotic’ Okazaki Fragments Synthesized from a Prokaryotic Replication Origin. EMBO Rep. 2003, 4, 154–158. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, N.P.; Dionne, I.; Lundgren, M.; Marsh, V.L.; Bernander, R.; Bell, S.D. Identification of Two Origins of Replication in the Single Chromosome of the Archaeon Sulfolobus Solfataricus. Cell 2004, 116, 25–38. [CrossRef]

- Lundgren, M.; Andersson, A.; Chen, L.; Nilsson, P.; Bernander, R. Three Replication Origins in Sulfolobus Species: Synchronous Initiation of Chromosome Replication and Asynchronous Termination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004, 101, 7046–7051. [CrossRef]

- She, Q.; Peng, X.; Zillig, W.; Garrett, R.A. Gene Capture in Archaeal Chromosomes. Nature 2001, 409, 478–478. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, N.P.; Bell, S.D. Extrachromosomal Element Capture and the Evolution of Multiple Replication Origins in Archaeal Chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007, 104, 5806–5811. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, C.-T. Multiple Replication Origins of the Archaeon Halobacterium Species NRC-1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 302, 728–734. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, H.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Xiang, H. Diversity and Evolution of Multiple Orc/Cdc6-Adjacent Replication Origins in Haloarchaea. BMC Genomics 2012, 13, 478. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M.S. DNA Replication Origins in Haloferax Volcanii. Doctoral Thesis, University of Nottingham: Nottingham, United Kingdom, 2009.

- Dyall-Smith, M.L.; Pfeiffer, F.; Klee, K.; Palm, P.; Gross, K.; Schuster, S.C.; Rampp, M.; Oesterhelt, D. Haloquadratum Walsbyi : Limited Diversity in a Global Pond. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20968. [CrossRef]

- Rozgaja, T.A.; Grimwade, J.E.; Iqbal, M.; Czerwonka, C.; Vora, M.; Leonard, A.C. Two Oppositely Oriented Arrays of Low-Affinity Recognition Sites in oriC Guide Progressive Binding of DnaA during Escherichia Coli Pre-RC Assembly: DnaA-oriC Interaction at Arrayed Sites. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 82, 475–488. [CrossRef]

- Matsui, M.; Oka, A.; Takanami, M.; Yasuda, S.; Hirota, Y. Sites of dnaA Protein-Binding in the Replication Origin of the Escherichia Coli K-12 Chromosome. J. Mol. Biol. 1985, 184, 529–533. [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M.; Noguchi, Y.; Sakiyama, Y.; Kawakami, H.; Katayama, T.; Takada, S. Near-Atomic Structural Model for Bacterial DNA Replication Initiation Complex and Its Functional Insights. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113. [CrossRef]

- Erzberger, J.P. The Structure of Bacterial DnaA: Implications for General Mechanisms Underlying DNA Replication Initiation. EMBO J. 2002, 21, 4763–4773. [CrossRef]

- Erzberger, J.P.; Berger, J.M. Evolutionary Relationships and Structural Mechanisms of AAA+ Proteins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2006, 35, 93–114. [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, D.; Eddy, M.J. The DNA Unwinding Element: A Novel, Cis-Acting Component That Facilitates Opening of the Escherichia Coli Replication Origin. EMBO J. 1989, 8, 4335–4344. [CrossRef]

- Wegrzyn, K.; Konieczny, I. Toward an Understanding of the DNA Replication Initiation in Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1328842. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, N.P.; Bell, S.D. Origins of DNA Replication in the Three Domains of Life. FEBS J. 2005, 272, 3757–3766. [CrossRef]

- Schwob, E. Flexibility and Governance in Eukaryotic DNA Replication. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2004, 7, 680–690. [CrossRef]

- Segurado, M.; Gómez, M.; Antequera, F. Increased Recombination Intermediates and Homologous Integration Hot Spots at DNA Replication Origins. Mol. Cell 2002, 10, 907–916. [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.M.; Takebayashi, S.-I.; Ryba, T.; Lu, J.; Pope, B.D.; Wilson, K.A.; Hiratani, I. Space and Time in the Nucleus: Developmental Control of Replication Timing and Chromosome Architecture. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2010, 75, 143–153. [CrossRef]

- Labib, K. How Do Cdc7 and Cyclin-Dependent Kinases Trigger the Initiation of Chromosome Replication in Eukaryotic Cells? Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 1208–1219. [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, M.; Langston, L.; Stillman, B. Principles and Concepts of DNA Replication in Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a010108–a010108. [CrossRef]

- Hartwell, L.H. Sequential Function of Gene Products Relative to DNA Synthesis in the Yeast Cell Cycle. J. Mol. Biol. 1976, 104, 803–817. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, J.F.X.; Beach, D. Cdt 1 Is an Essential Target of the Cdc 1 O/Sct 1 Transcription Factor: Requirement for DNA Replication and Inhibition of Mitosis.

- Nishitani, H.; Lygerou, Z.; Nishimoto, T.; Nurse, P. The Cdt1 Protein Is Required to License DNA for Replication in ®ssion Yeast. 2000, 404.

- Schmidt, J.M.; Yang, R.; Kumar, A.; Hunker, O.; Seebacher, J.; Bleichert, F. A Mechanism of Origin Licensing Control through Autoinhibition of S. Cerevisiae ORC·DNA·Cdc6. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1059. [CrossRef]

- Randell, J.C.W.; Bowers, J.L.; Rodríguez, H.K.; Bell, S.P. Sequential ATP Hydrolysis by Cdc6 and ORC Directs Loading of the Mcm2-7 Helicase. Mol. Cell 2006, 21, 29–39. [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.; Diffley, J.F.X. The Initiation of Eukaryotic DNA Replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2022, 91, 107–131. [CrossRef]

- Ilves, I.; Petojevic, T.; Pesavento, J.J.; Botchan, M.R. Activation of the MCM2-7 Helicase by Association with Cdc45 and GINS Proteins. Mol. Cell 2010, 37, 247–258. [CrossRef]

- Zegerman, P.; Diffley, J.F.X. Phosphorylation of Sld2 and Sld3 by Cyclin-Dependent Kinases Promotes DNA Replication in Budding Yeast. Nature 2007, 445, 281–285. [CrossRef]

- Greci, M.D.; Bell, S.D. Archaeal DNA Replication. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 74, 65–80. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, P.; Philippe, H.; Myllykallio, H.; Forterre, P. Identification of Putative Chromosomal Origins of Replication in Archaea. Mol. Microbiol. 1999, 32, 883–886. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Smith, C.L.; DeRyckere, D.; DeAngelis, K.; Martin, G.S.; Berger, J.M. Structure and Function of Cdc6/Cdc18: Implications for Origin Recognition and Checkpoint Control. Mol. Cell 2000, 6, 637–648.

- Matsunaga, F.; Glatigny, A.; Mucchielli-Giorgi, M.-H.; Agier, N.; Delacroix, H.; Marisa, L.; Durosay, P.; Ishino, Y.; Aggerbeck, L.; Forterre, P. Genomewide and Biochemical Analyses of DNA-Binding Activity of Cdc6/Orc1 and Mcm Proteins in Pyrococcus Sp. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 3214–3222. [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, F.; Takemura, K.; Akita, M.; Adachi, A.; Yamagami, T.; Ishino, Y. Localized Melting of Duplex DNA by Cdc6/Orc1 at the DNA Replication Origin in the Hyperthermophilic Archaeon Pyrococcus Furiosus. Extremophiles 2010, 14, 21–31. [CrossRef]

- Gaudier, M.; Schuwirth, B.S.; Westcott, S.L.; Wigley, D.B. Structural Basis of DNA Replication Origin Recognition by an ORC Protein. Science 2007, 317, 1213–1216. [CrossRef]

- Grainge, I. Biochemical Analysis of Components of the Pre-Replication Complex of Archaeoglobus Fulgidus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 4888–4898. [CrossRef]

- Samson, R.Y.; Xu, Y.; Gadelha, C.; Stone, T.A.; Faqiri, J.N.; Li, D.; Qin, N.; Pu, F.; Liang, Y.X.; She, Q.; et al. Specificity and Function of Archaeal DNA Replication Initiator Proteins. Cell Rep. 2013, 3, 485–496. [CrossRef]

- Dueber, E.L.C.; Corn, J.E.; Bell, S.D.; Berger, J.M. Replication Origin Recognition and Deformation by a Heterodimeric Archaeal Orc1 Complex. Science 2007, 317, 1210–1213. [CrossRef]

- Grainge, I.; Gaudier, M.; Schuwirth, B.S.; Westcott, S.L.; Sandall, J.; Atanassova, N.; Wigley, D.B. Biochemical Analysis of a DNA Replication Origin in the Archaeon Aeropyrum Pernix. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 363, 355–369. [CrossRef]

- Ausiannikava, D.; Allers, T. Diversity of DNA Replication in the Archaea. Genes 2017, 8, 56. [CrossRef]

- Akita, M.; Adachi, A.; Takemura, K.; Yamagami, T.; Matsunaga, F.; Ishino, Y. Cdc6/Orc1 from Pyrococcus Furiosus May Act as the Origin Recognition Protein and Mcm Helicase Recruiter. Genes Cells 2010, 15, 537–552. [CrossRef]

- Kelman, L.M.; O’Dell, W.B.; Kelman, Z. Unwinding 20 Years of the Archaeal Minichromosome Maintenance Helicase. J. Bacteriol. 2020, 202. [CrossRef]

- Kasiviswanathan, R.; Shin, J.-H.; Kelman, Z. Interactions between the Archaeal Cdc6 and MCM Proteins Modulate Their Biochemical Properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 4940–4950. [CrossRef]

- Samson, R.Y.; Abeyrathne, P.D.; Bell, S.D. Mechanism of Archaeal MCM Helicase Recruitment to DNA Replication Origins. Mol. Cell 2016, 61, 287–296. [CrossRef]

- Samson, R.Y.; Bell, S.D. MCM Loading—An Open-and-Shut Case? Mol. Cell 2013, 50, 457–458. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed Khalid, A.A.; Parisse, P.; Medagli, B.; Onesti, S.; Casalis, L. Atomic Force Microscopy Investigation of the Interactions between the MCM Helicase and DNA. Materials 2021, 14, 687. [CrossRef]

- Kelman, Z.; Lee, J.-K.; Hurwitz, J. The Single Minichromosome Maintenance Protein of Methanobacterium Thermoautotrophicum ⌬H Contains DNA Helicase Activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1999, 96, 14783–14788.

- Haugland, G.T.; Shin, J.-H.; Birkeland, N.-K.; Kelman, Z. Stimulation of MCM Helicase Activity by a Cdc6 Protein in the Archaeon Thermoplasma Acidophilum. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 6337–6344. [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Arnaiz, P.; Dattani, A.; Smith, V.; Allers, T. Haloferax Volcanii —a Model Archaeon for Studying DNA Replication and Repair. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200293. [CrossRef]

- Cairns, J. The Bacterial Chromosome and Its Manner of Replication as Seen by Autoradiography. J. Mol. Biol. 1963, 6, 208–213.

- Okazaki, R.; Okazaki, T.; Sakabe, K.; Sugimoto, K.; Sugino, A. Mechanism of DNA Chain Growth. I. Possible Discontinuity and Unusual Secondary Structure of Newly Synthesized Chains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1968, 59, 598–605. [CrossRef]

- Kelman, L.M.; Kelman, Z. Archaea: An Archetype for Replication Initiation Studies? Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 48, 605–615. [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, R.; Langston, L.; O’Donnell, M. A Proposal: Evolution of PCNA’s Role as a Marker of Newly Replicated DNA. DNA Repair 2015, 29, 4–15. [CrossRef]

- Leipe, D.D.; Aravind, L.; Koonin, E.V. Did DNA Replication Evolve Twice Independently? Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 3389–3401. [CrossRef]

- Forterre, P. Why Are There So Many Diverse Replication Machineries? J. Mol. Biol. 2013, 425, 4714–4726. [CrossRef]

- Lujan, S.A.; Williams, J.S.; Kunkel, T.A. DNA Polymerases Divide the Labor of Genome Replication. Trends Cell Biol. 2016, 26, 640–654. [CrossRef]

- Iyer, L.M. Origin and Evolution of the Archaeo-Eukaryotic Primase Superfamily and Related Palm-Domain Proteins: Structural Insights and New Members. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 3875–3896. [CrossRef]

- Kreuzer, K.N. Recombination-Dependent DNA Replication in Phage T4. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000, 25, 165–173. [CrossRef]

- Mosig, G.; Gewin, J.; Luder, A.; Colowick, N.; Vo, D. Two Recombination-Dependent DNA Replication Pathways of Bacteriophage T4, and Their Roles in Mutagenesis and Horizontal Gene Transfer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001, 98, 8306–8311. [CrossRef]

- Belanger, K.G.; Kreuzer, K.N. Bacteriophage T4 Initiates Bidirectional DNA Replication through a Two-Step Process. Mol. Cell 1998, 2, 693–701. [CrossRef]

- Syeda, A.H.; Hawkins, M.; McGlynn, P. Recombination and Replication. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6, a016550–a016550. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; VanLoock, M.S.; Yu, X.; Egelman, E.H. Comparison of Bacteriophage T4 UvsX and Human Rad51 Filaments Suggests That RecA-like Polymers May Have Evolved independently11Edited by M. Belfort. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 312, 999–1009. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Marians, K.J. PriA-Directed Assembly of a Primosome on D Loop DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 25033–25041. [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.M. The Phi X174-Type Primosome Promotes Replisome Assembly at the Site of Recombination in Bacteriophage Mu Transposition. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 6886–6895. [CrossRef]

- Epum, E.A.; Haber, J.E. DNA Replication: The Recombination Connection. Trends Cell Biol. 2022, 32, 45–57. [CrossRef]

- Anand, R.P.; Lovett, S.T.; Haber, J.E. Break-Induced DNA Replication. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a010397–a010397. [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Lever, R.; Cubbon, A.; Tehseen, M.; Jenkins, T.; Nottingham, A.O.; Horton, A.; Betts, H.; Fisher, M.; Hamdan, S.M.; et al. Interaction of Human HelQ with DNA Polymerase Delta Halts DNA Synthesis and Stimulates DNA Single-Strand Annealing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 1740–1749. [CrossRef]

- Malkova, A.; Ira, G. Break-Induced Replication: Functions and Molecular Mechanism. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2013, 23, 271–279. [CrossRef]

- Ravoitytė, B.; Wellinger, R. Non-Canonical Replication Initiation: You’re Fired! Genes 2017, 8, 54. [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.S. Stressed? Break-Induced Replication Comes to the Rescue! DNA Repair 2024, 142.

- Kogoma, T.; Lark, K.G. Characterization of the Replication of Escherichia Coli DNA in the Absence of Protein Synthesis: Stable DNA Replication. J. Mol. Biol. 1975, 94, 243–256. [CrossRef]

- Masai, H.; Asai, T.; Kubota, Y.; Arai, K.; Kogoma, T. Escherichia Coil PriA Protein Is Essential for Inducible and Constitutive Stable DNA Replication. EMBO J. 1994, 13, 5338–5345.

- Crossley, M.P.; Bocek, M.; Cimprich, K.A. R-Loops as Cellular Regulators and Genomic Threats. Mol. Cell 2019, 73, 398–411. [CrossRef]

- Masai, H. Replicon Hypothesis Revisited. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 633, 77–80. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M.; Malla, S.; Blythe, M.J.; Nieduszynski, C.A.; Allers, T. Accelerated Growth in the Absence of DNA Replication Origins. Nature 2013, 503, 544–547. [CrossRef]

- Kogoma, T. Recombination by Replication. Cell 1996, 85, 625-627,.

- Mc Teer, L.; Moalic, Y.; Cueff-Gauchard, V.; Catchpole, R.; Hogrel, G.; Lu, Y.; Laurent, S.; Hemon, M.; Aubé, J.; Leroy, E.; et al. Cooperation between Two Modes for DNA Replication Initiation in the Archaeon Thermococcus Barophilus. mBio 2024, 15, e03200-23. [CrossRef]

- Rosenshine, I.; Tchelet, R.; Mevarech, M. The Mechanism of DNA Transfer in the Mating System of an Archaebacterium. Science 1989, 245, 1387–1389. [CrossRef]

- Gehring, A.M.; Astling, D.P.; Matsumi, R.; Burkhart, B.W.; Kelman, Z.; Reeve, J.N.; Jones, K.L.; Santangelo, T.J. Genome Replication in Thermococcus Kodakarensis Independent of Cdc6 and an Origin of Replication. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2084. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wu, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Cai, S.; Xiang, H. Activation of a Dormant Replication Origin Is Essential for Haloferax Mediterranei Lacking the Primary Origins. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8321. [CrossRef]

- Pace, N.R.; Sapp, J.; Goldenfeld, N. Phylogeny and beyond: Scientific, Historical, and Conceptual Significance of the First Tree of Life. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 1011–1018. [CrossRef]

- Sanger, F.; Brownlee, G.G.; Barrell, B.G. A Two-Dimensional Fractionation Procedure for Radioactive Nucleotides. J. Mol. Biol. 1965, 13.

- Fox, G.E.; Woese, C.R. Classification of Methanogenic Bacteria by 16S Ribosomal RNA Characterization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1977, 74, 4537–4541.

- Albers, S.-V.; Forterre, P.; Prangishvili, D.; Schleper, C. The Legacy of Carl Woese and Wolfram Zillig: From Phylogeny to Landmark Discoveries. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 713–719. [CrossRef]

- Zillig, W.; Klenk, H.-P.; Palm, P.; Pühler, G.; Gropp, F.; Garrett, R.A.; Leffers, H. The Phylogenetic Relations of DNA-Dependent RNA Polymerases of Archaebacteria, Eukaryotes, and Eubacteria. Can. J. Microbiol. 1989, 35, 73–80. [CrossRef]

- Zillig, W. Comparative Biochemistry of Archaea and Bacteria. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1991, 1, 544–551. [CrossRef]

- Woese, C.R. Towards a Natural System of Organisms: Proposal for the Domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1990, 87, 4576–4579.

- Forterre, P.; Elie, C.; Kohiyama, M. Aphidicolin Inhibits Growth and DNA Synthesis in Halophilic Arachaebacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1984, 159, 800–802. [CrossRef]

- Ishino, Y.; Komori, K.; Cann, I.K.O.; Koga, Y. A Novel DNA Polymerase Family Found in Archaea. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 2232–2236. [CrossRef]

- Baum, B.; Spang, A. On the Origin of the Nucleus: A Hypothesis. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2023, 87, e00186-21. [CrossRef]

- Rinke, C.; Chuvochina, M.; Mussig, A.J.; Chaumeil, P.-A.; Davín, A.A.; Waite, D.W.; Whitman, W.B.; Parks, D.H.; Hugenholtz, P. A Standardized Archaeal Taxonomy for the Genome Taxonomy Database. Nat. Microbiol. 2021, 6, 946–959. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).