Submitted:

18 December 2024

Posted:

19 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

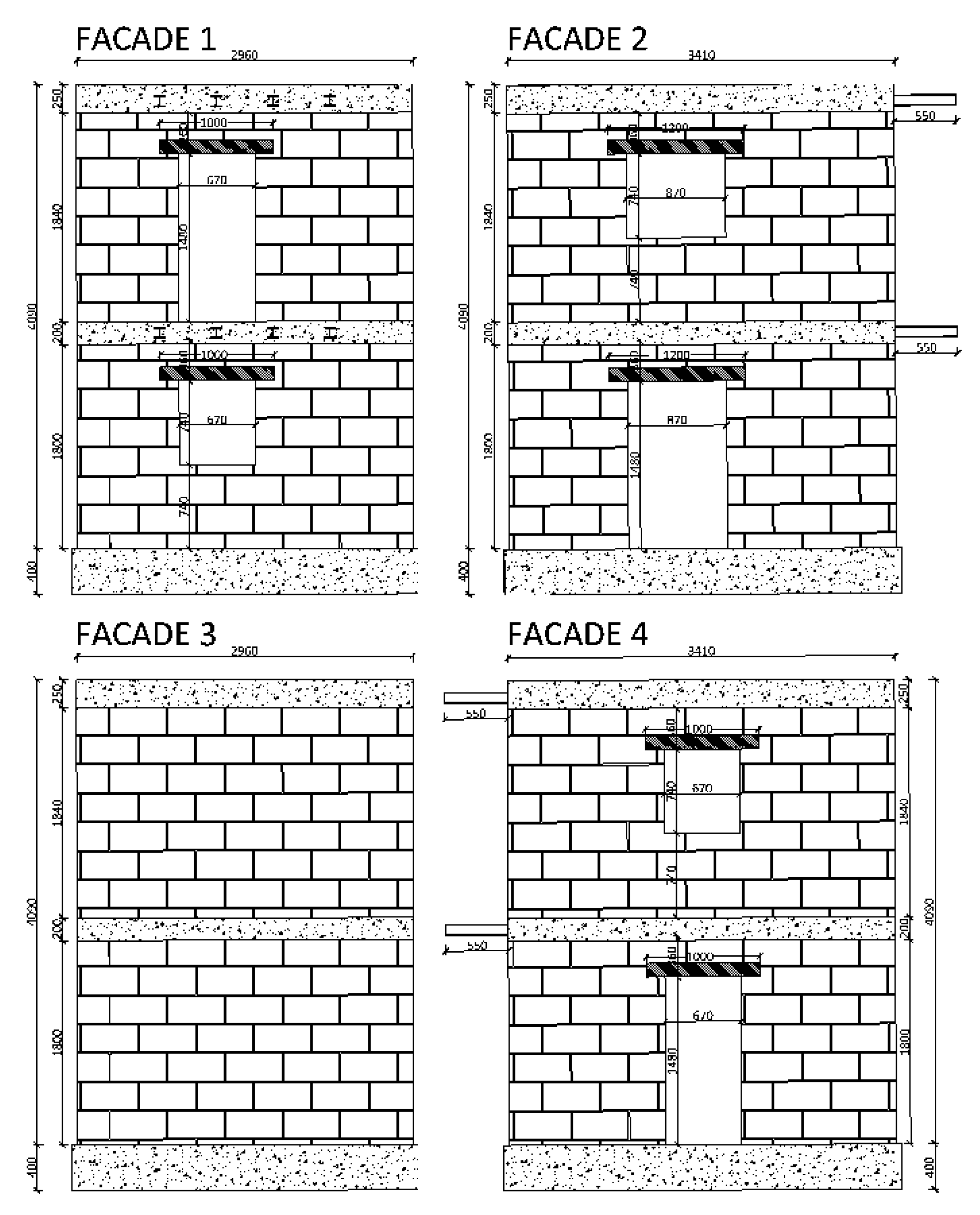

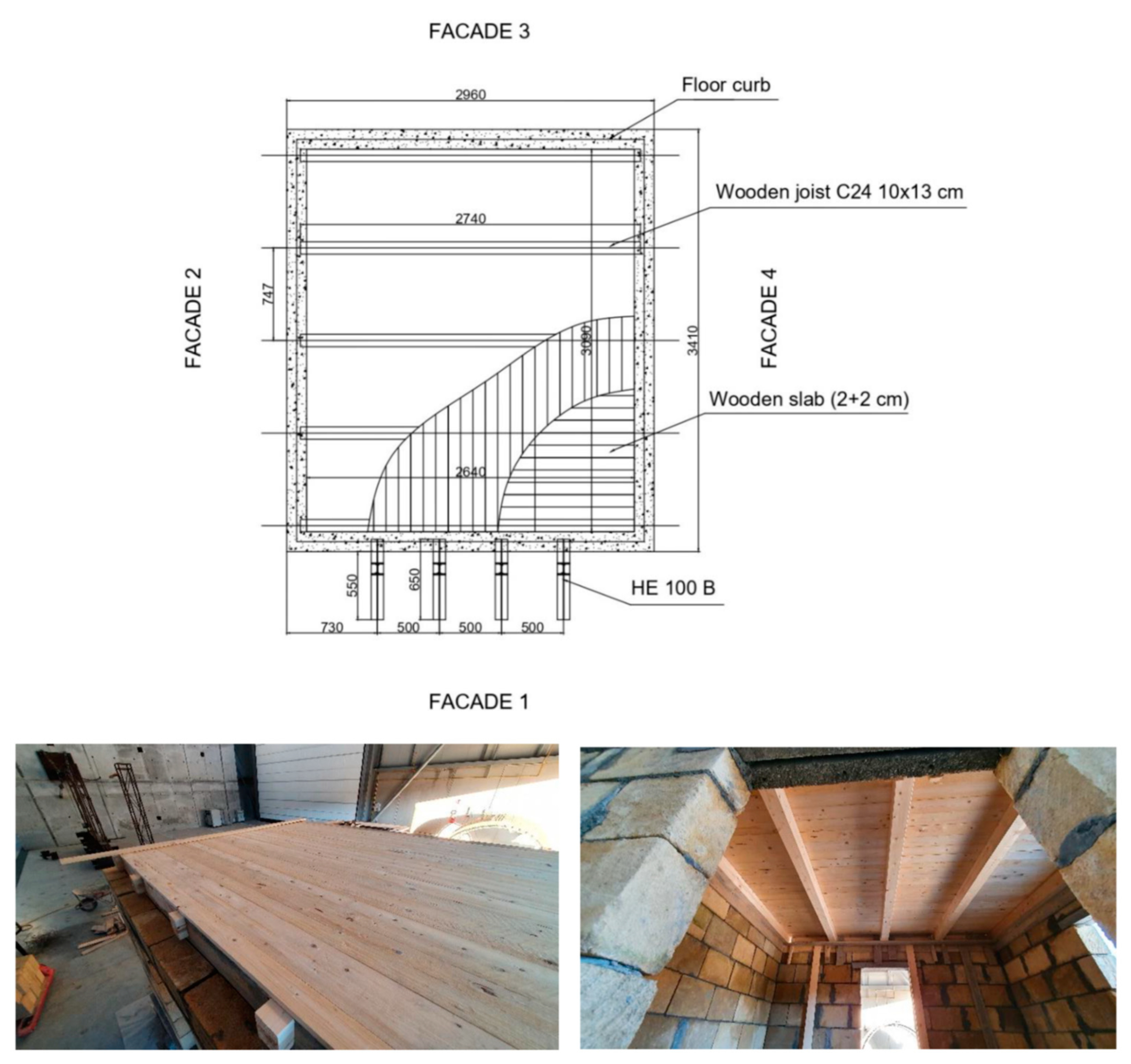

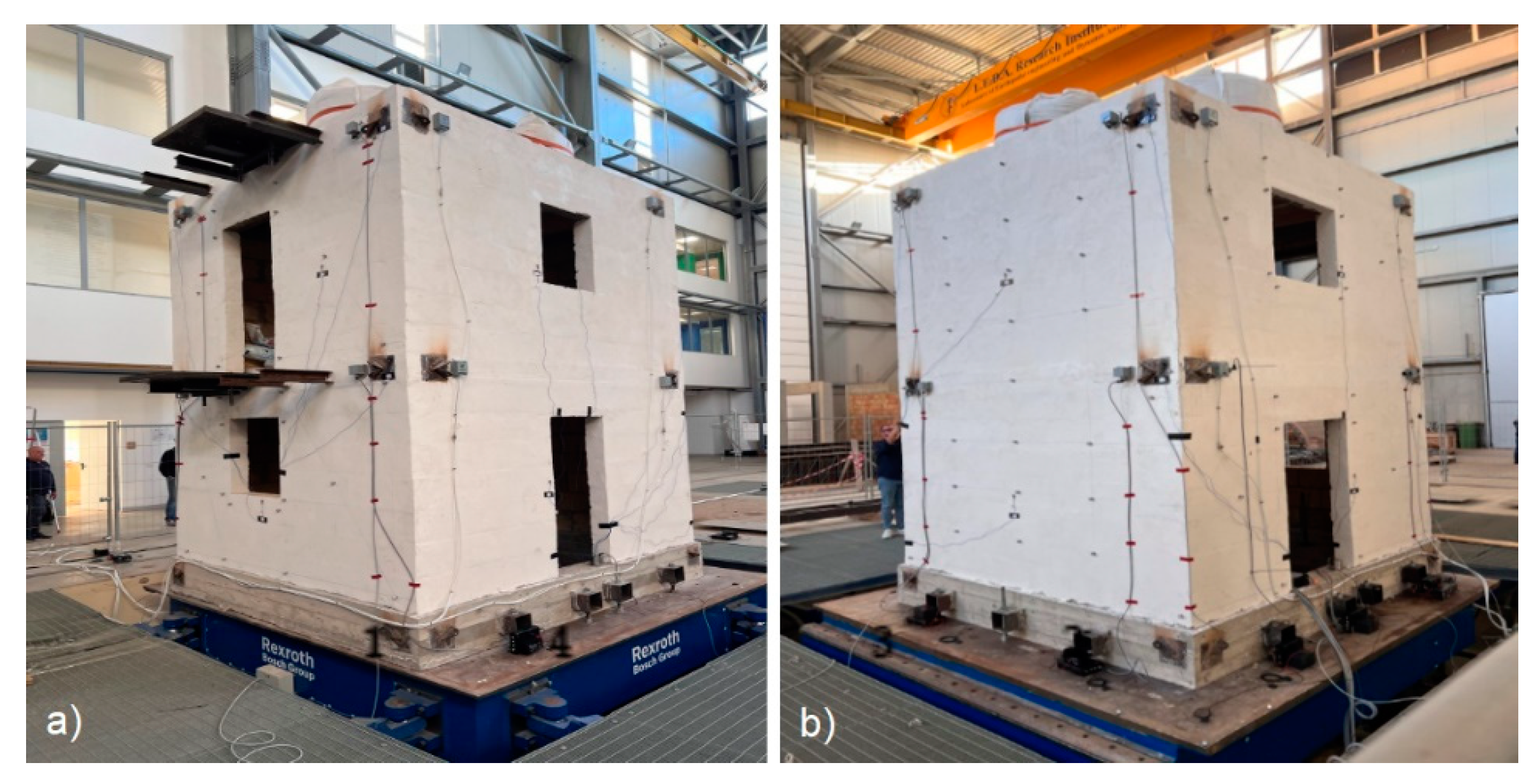

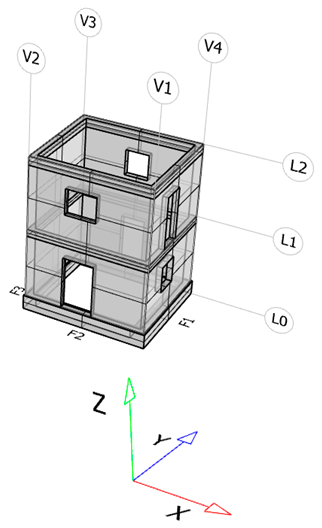

2.1. Building Characteristics

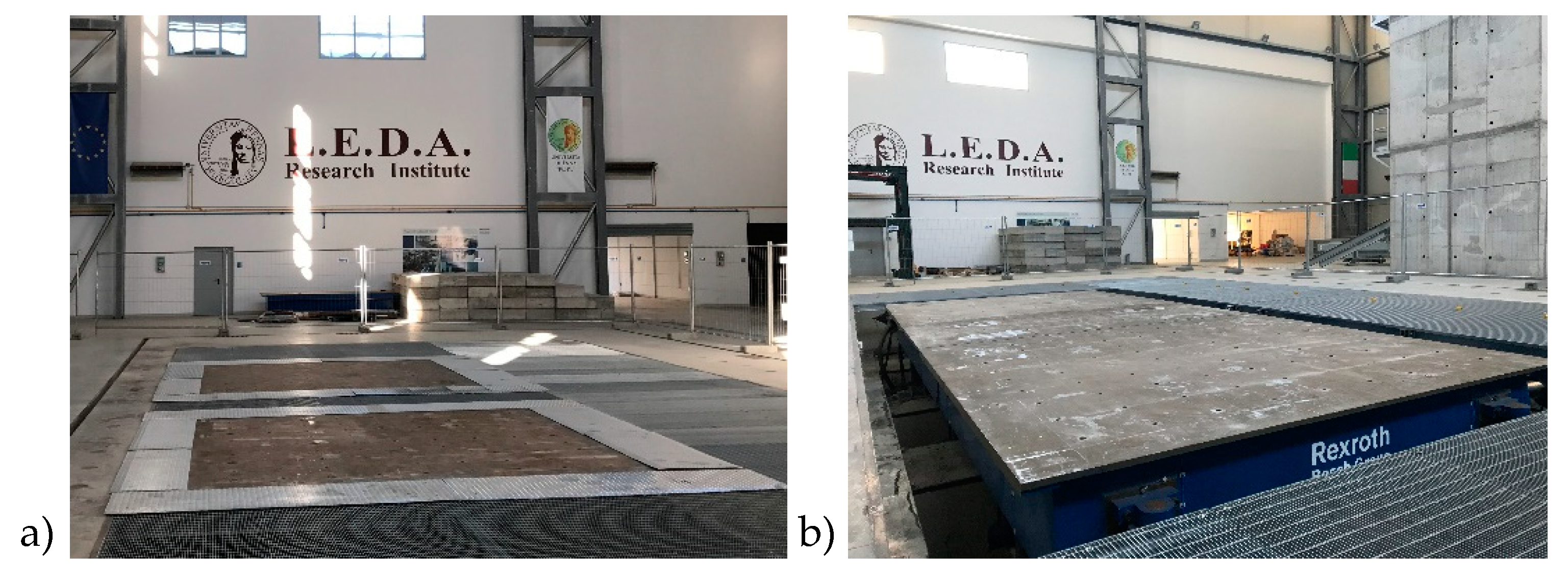

2.2. Test Facility

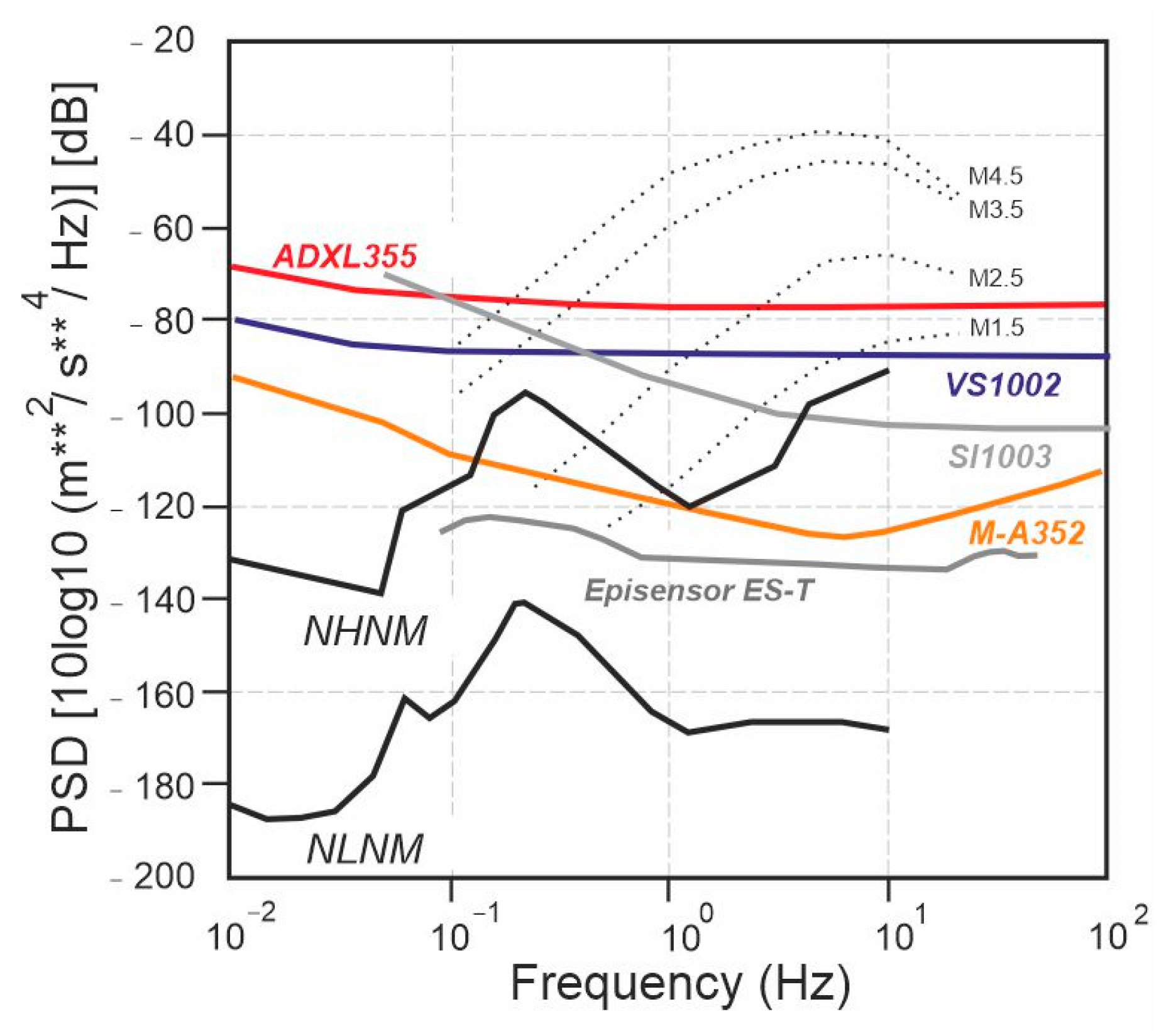

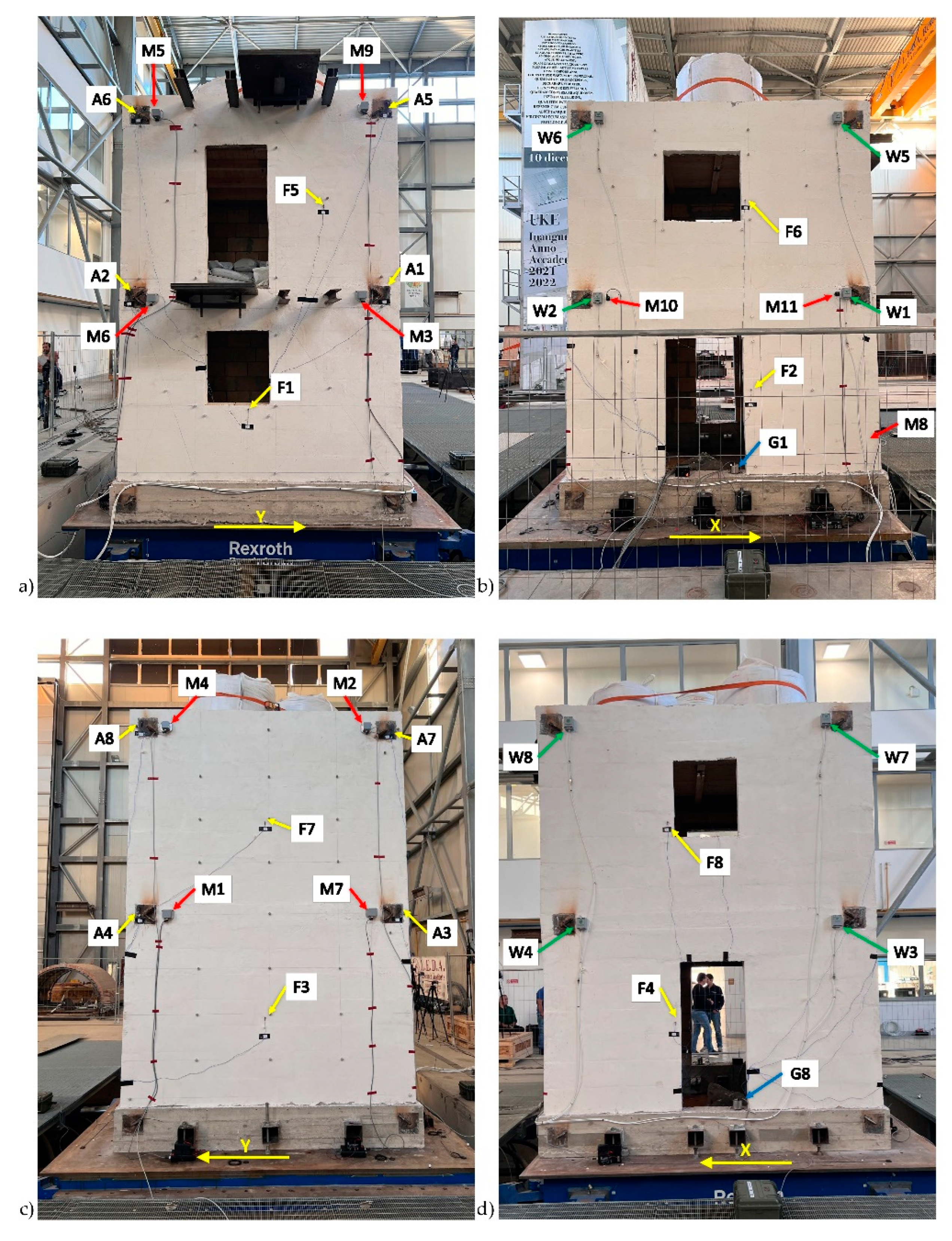

2.2. Instrumentation

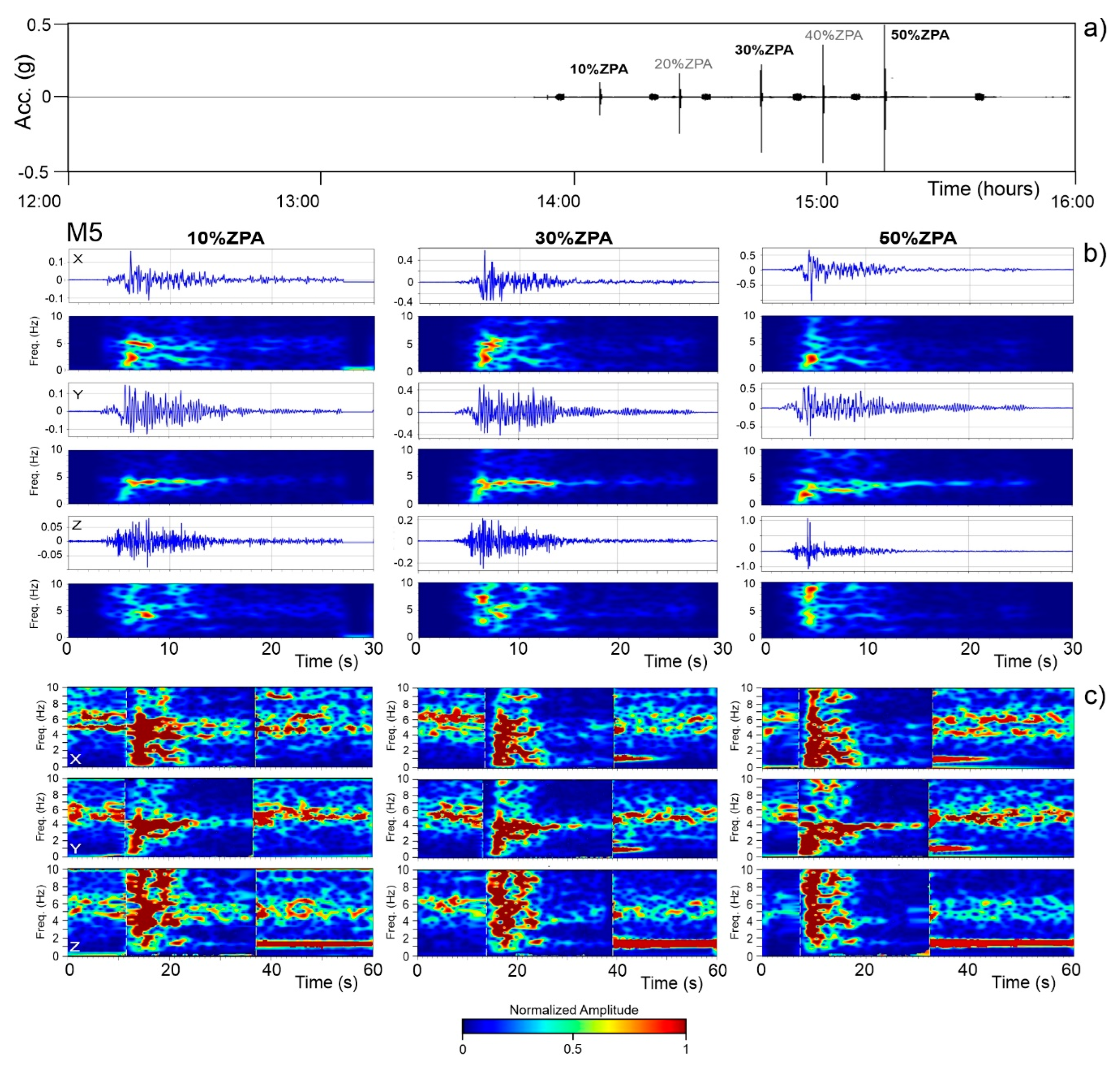

2.3. Tests Sequence

- Environmental noise when the shaking table was not operating.

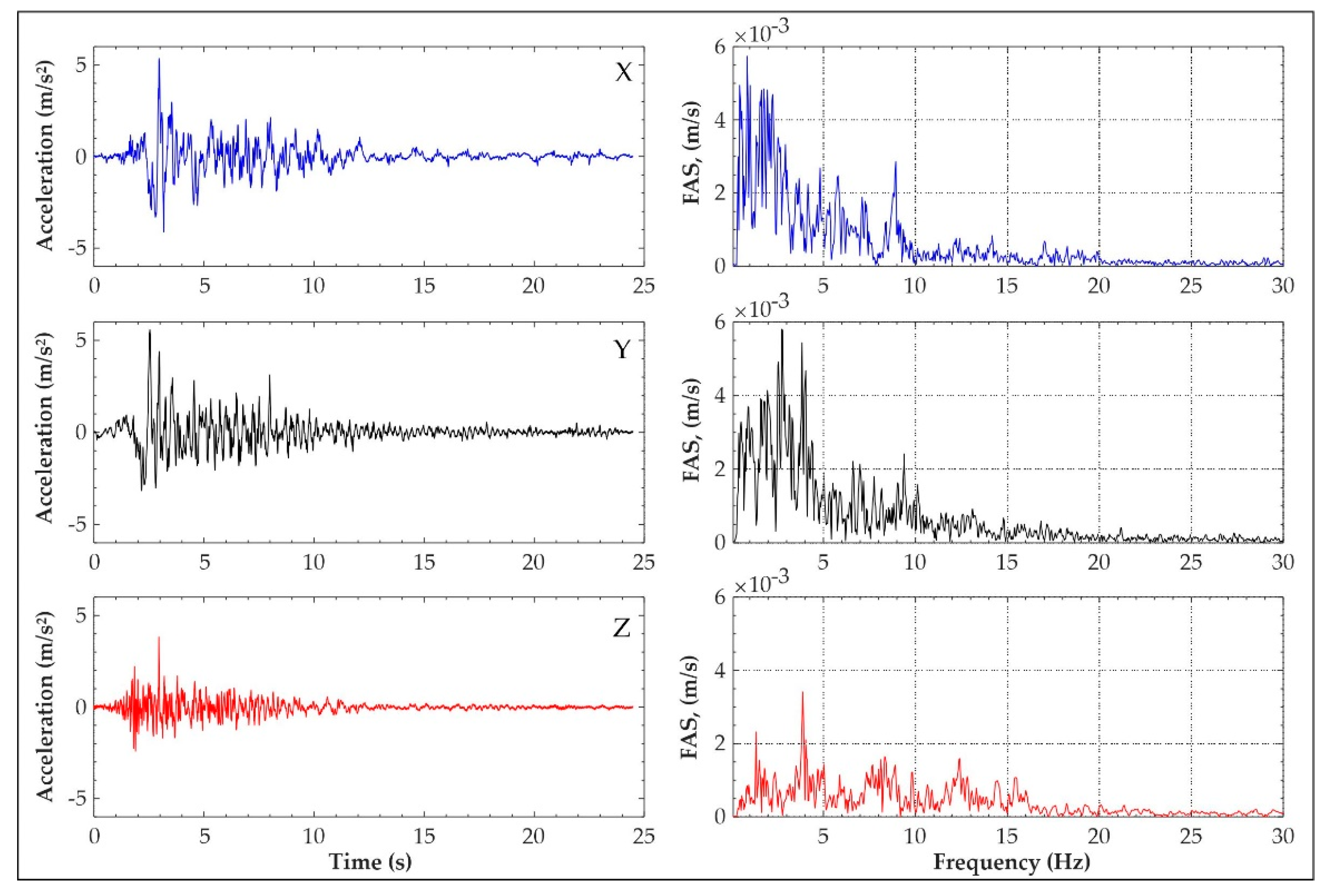

- Three-direction broadband noise excitation by reproducing on the shaking table a three-component, uncorrelated Gaussian random noise in the frequency ranges from 0.25 Hz to 60 Hz, with RMS amplitude equal to 0.03 g.

3. Results

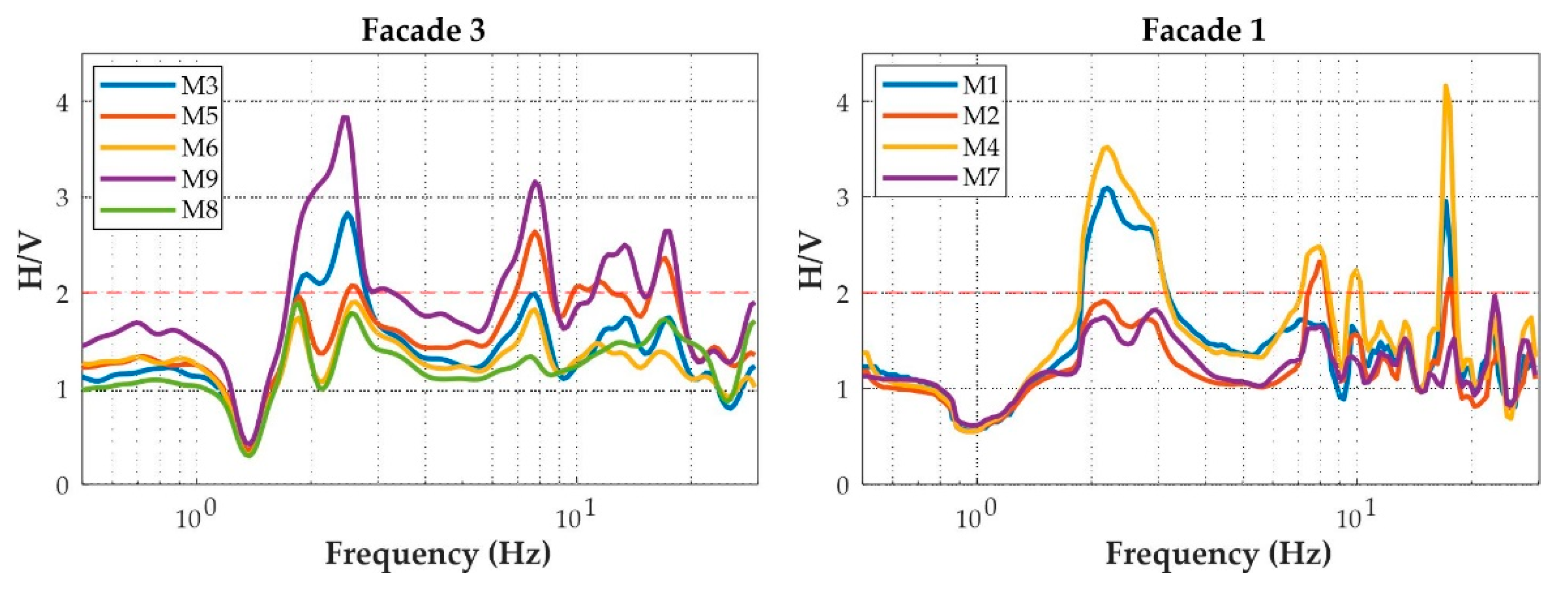

3.1. Analysis of Horizontal-to-Vertical Spectral Ratio (HVSR) of Ambient Noise

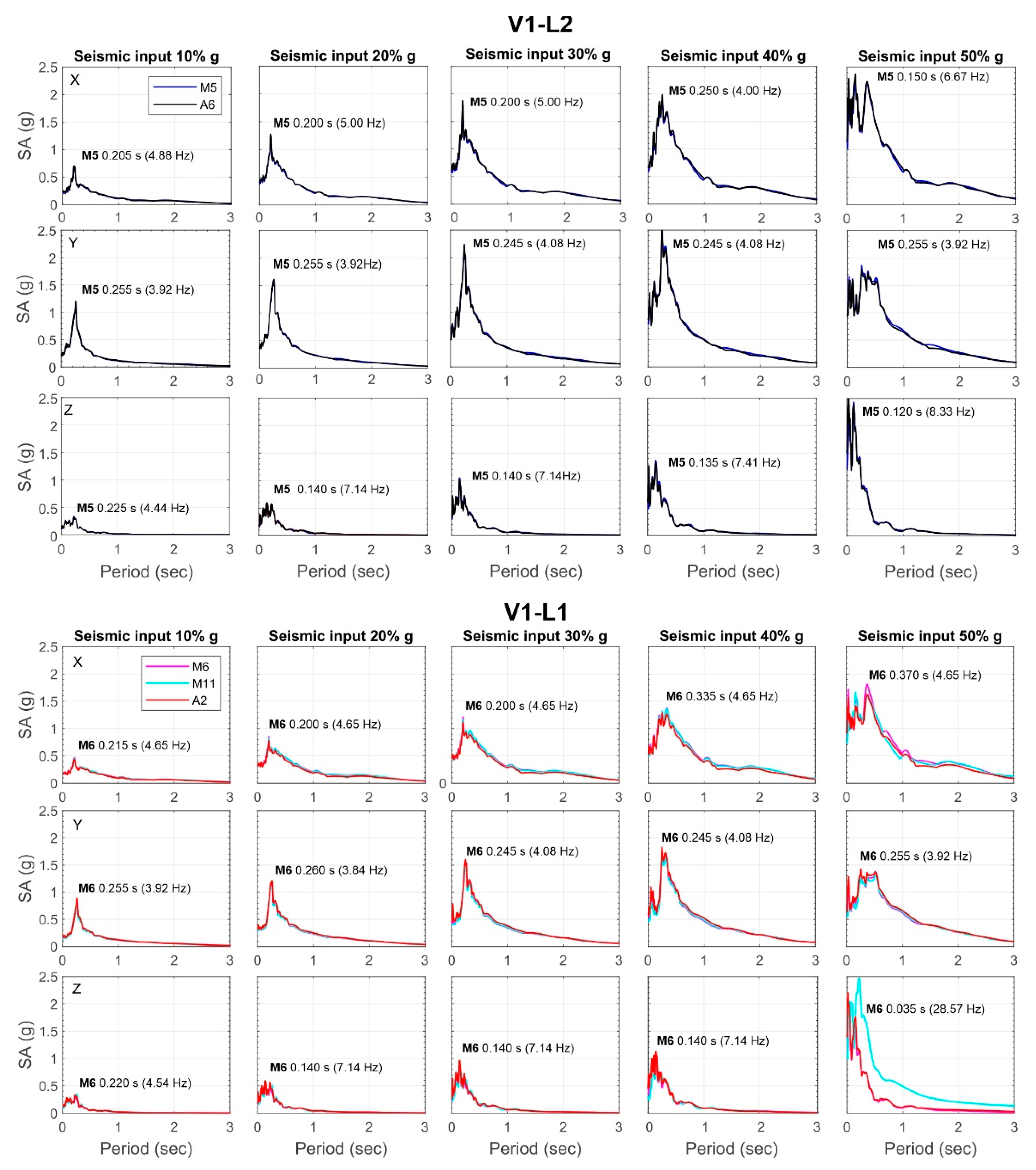

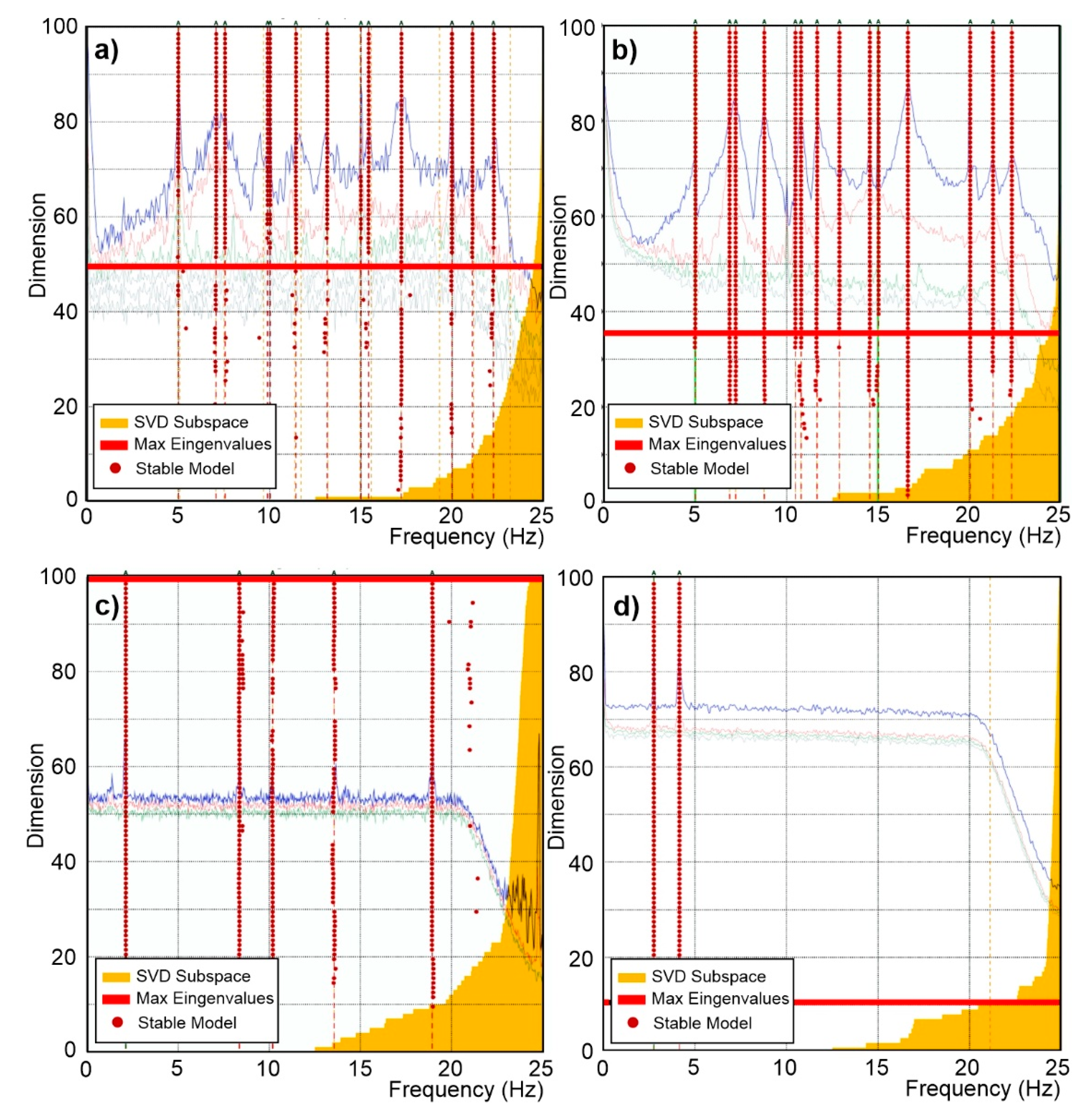

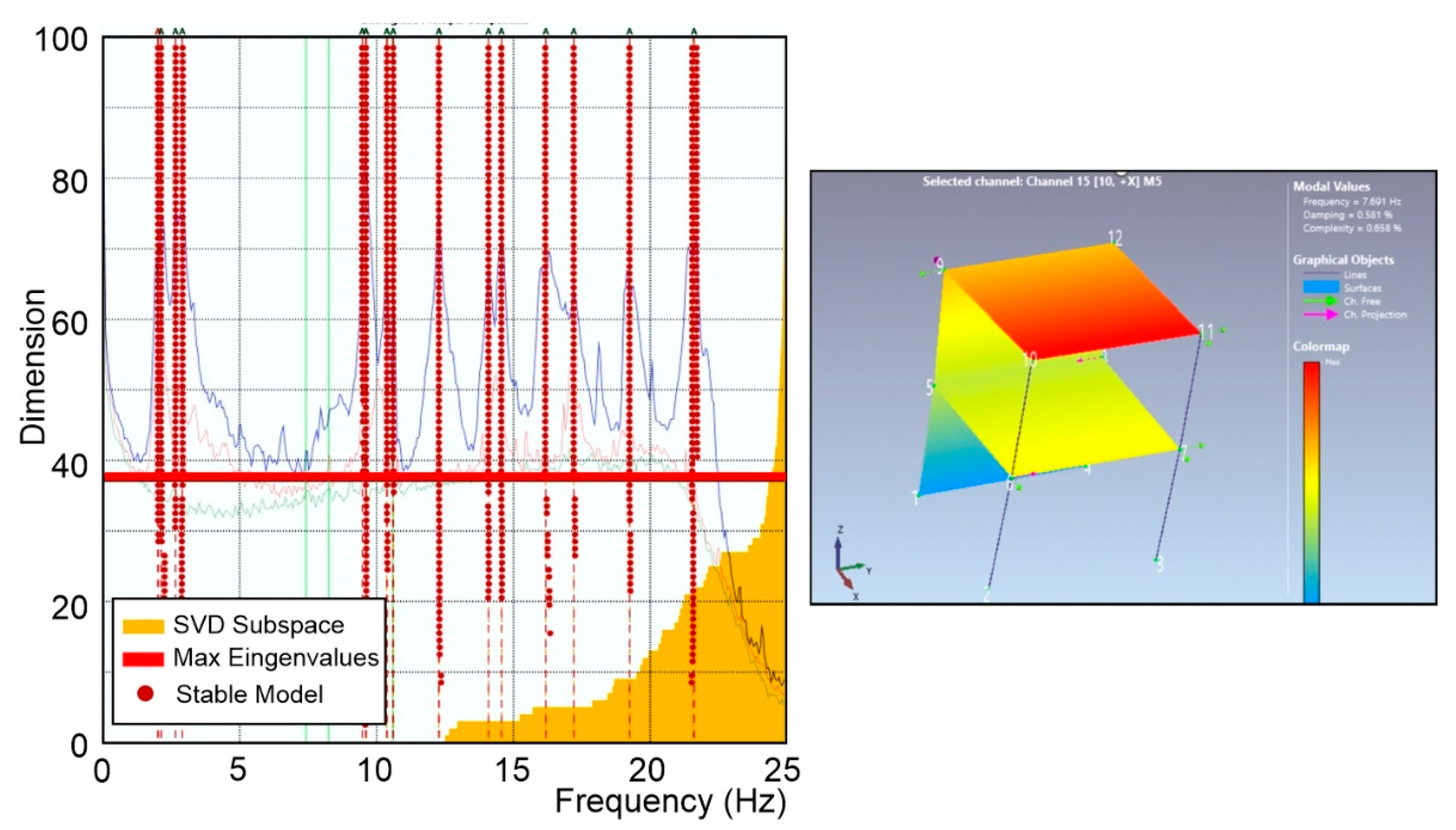

3.2. Structural Dynamic Behaviour

3.3. Strong Motion Parameters

3.4. Damage Distribution

4. Conclusions

- All the MEMS sensors used during the experiment demonstrated their ability to accurately measure the dynamic response during seismic excitation. Instead, their suitability for Operational Modal Analysis (OMA) under noisy conditions, such as during the experiment, varies significantly due to their self-noise characteristics.

- Overall, also for the piezoelectric sensors, the self-noise could become a crucial factor in very low ambient noise environments and for OMA applications, affecting the quality of results. Therefore, we retain that both piezoelectric and MEMS (Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems) accelerometers with self-noise levels below 1 µg/√Hz—or preferably below 0.5 µg/√Hz—are recommended for effective OMA analysis in environments with very low noise. In general, an ultra-lower sensor’s self-noise minimizes the interference from environmental noise, allowing for more precise identification of modal frequencies and damage detection.

- For MEMS sensors with self-noise greater than 1 µg/√Hz, their performance, as above mentioned, in very low-noise conditions may be significantly compromised and mask the acceleration signal. Additionally, other noise sources like wiring and electronic components can further degrade measurement quality. However, in SHM applications in environments with high noise levels, such as busy bridges, footbridges, or civil structures exposed to strong winds, these sensors may still provide adequate performance.

- The OMA analyses identified a frequency decrement during the test. The extensive OMA campaign and the comparison between several sensors confirmed the necessity to engage sensors with a low (or ultra-low) noise density if the frequency identification is needed, both before and after a seismic event for real applications. A suggested value of less than 1 µg/√Hz may be appropriate for analysis of stiff masonry structures. This aspect is crucial if a reliable estimation of damages has to be carried out after an event, under ambient noise conditions.

- The results obtained from Stockwell transform are coherent with expected dynamic behaviour of the structure and the impact of seismic loading. Indeed, a shift in lateral modes to lower frequencies can indicate reduced stiffness in the horizontal direction, whereas increased energy at higher frequencies in the Z-component could be attributed to vertical accelerations and structural rigidity in the vertical direction. It also indicates localized damage affecting the sensor’s response to seismic inputs, as higher frequencies are generated by local and global rocking of the masonry structure.

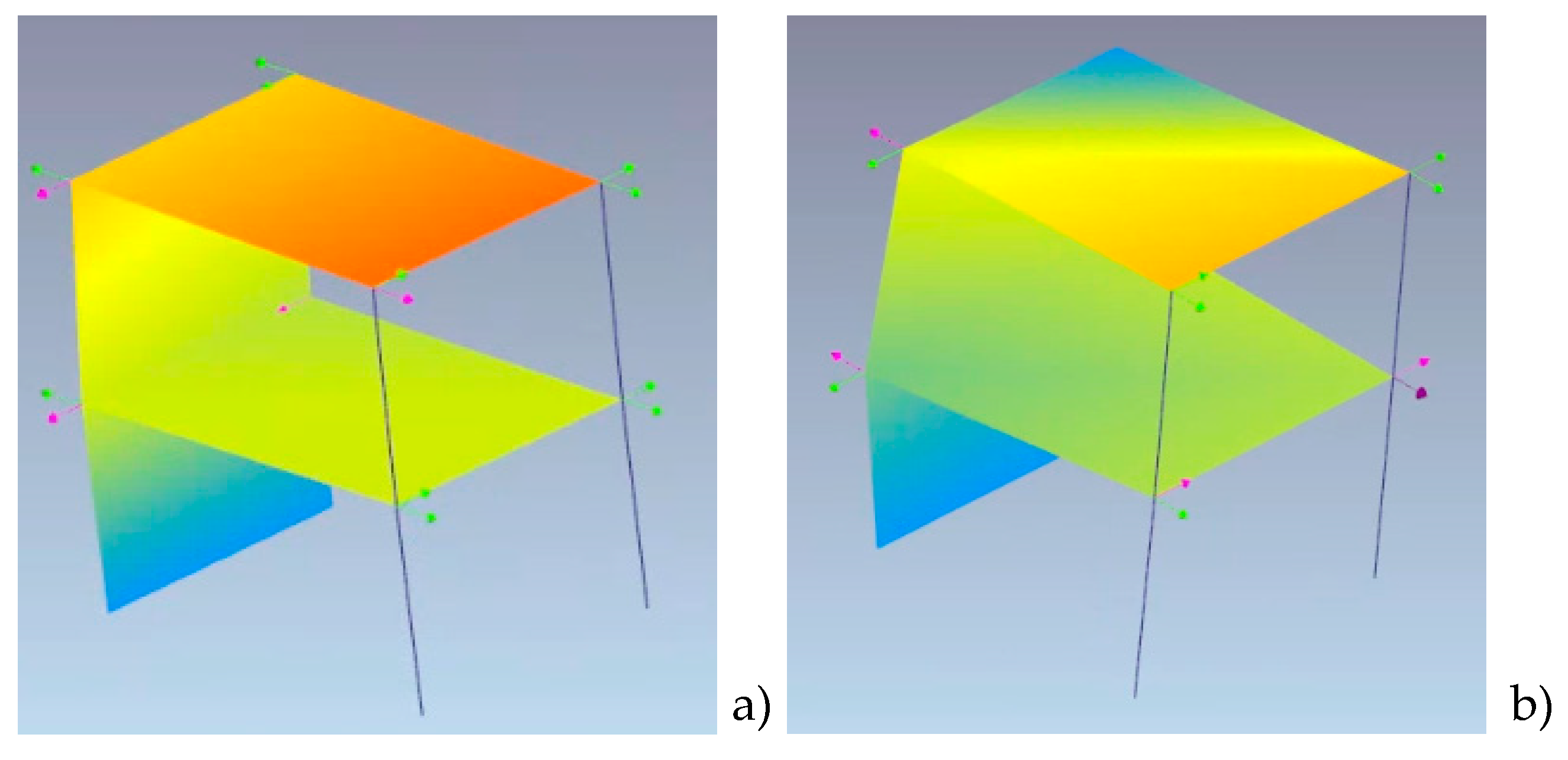

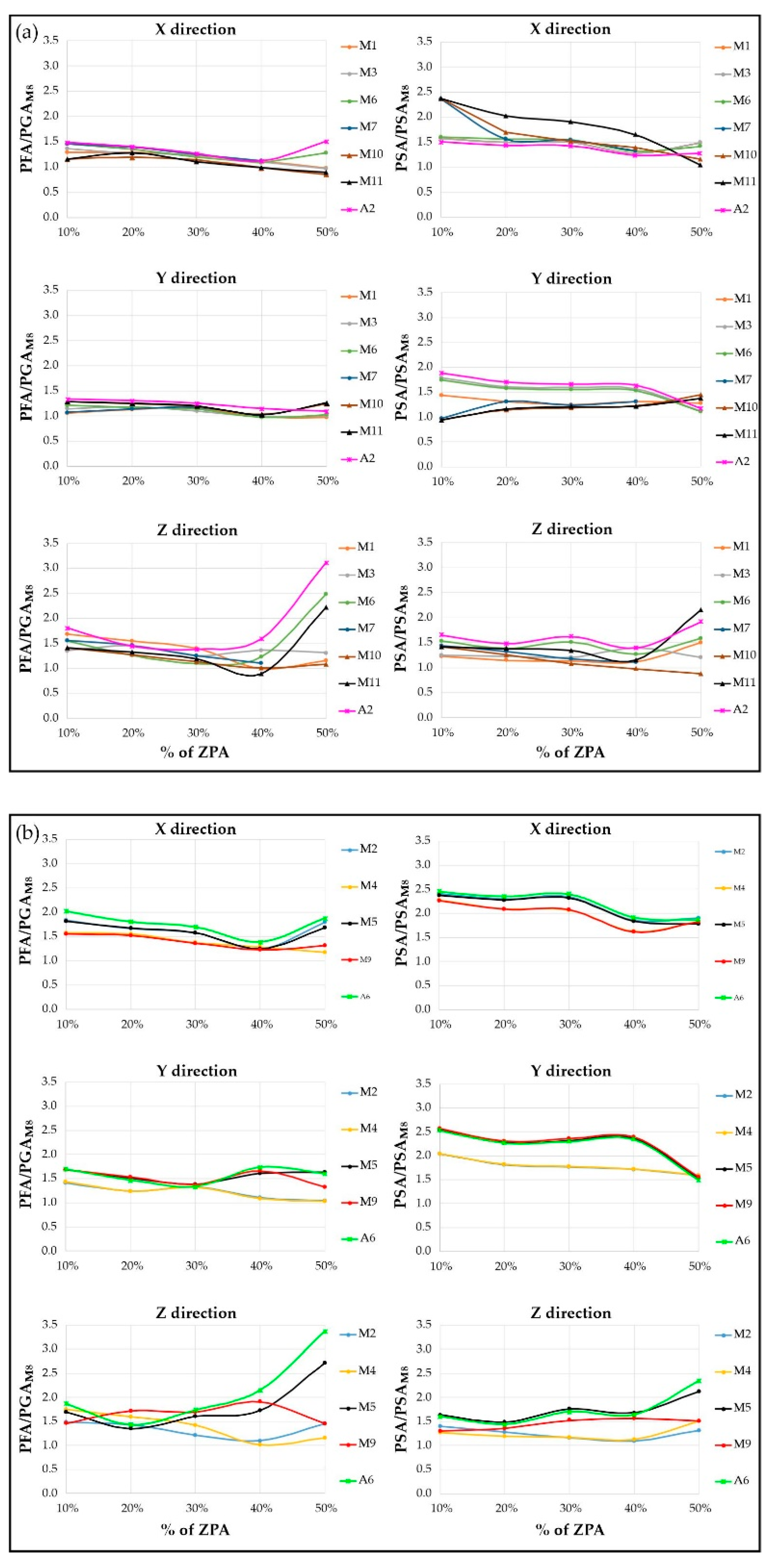

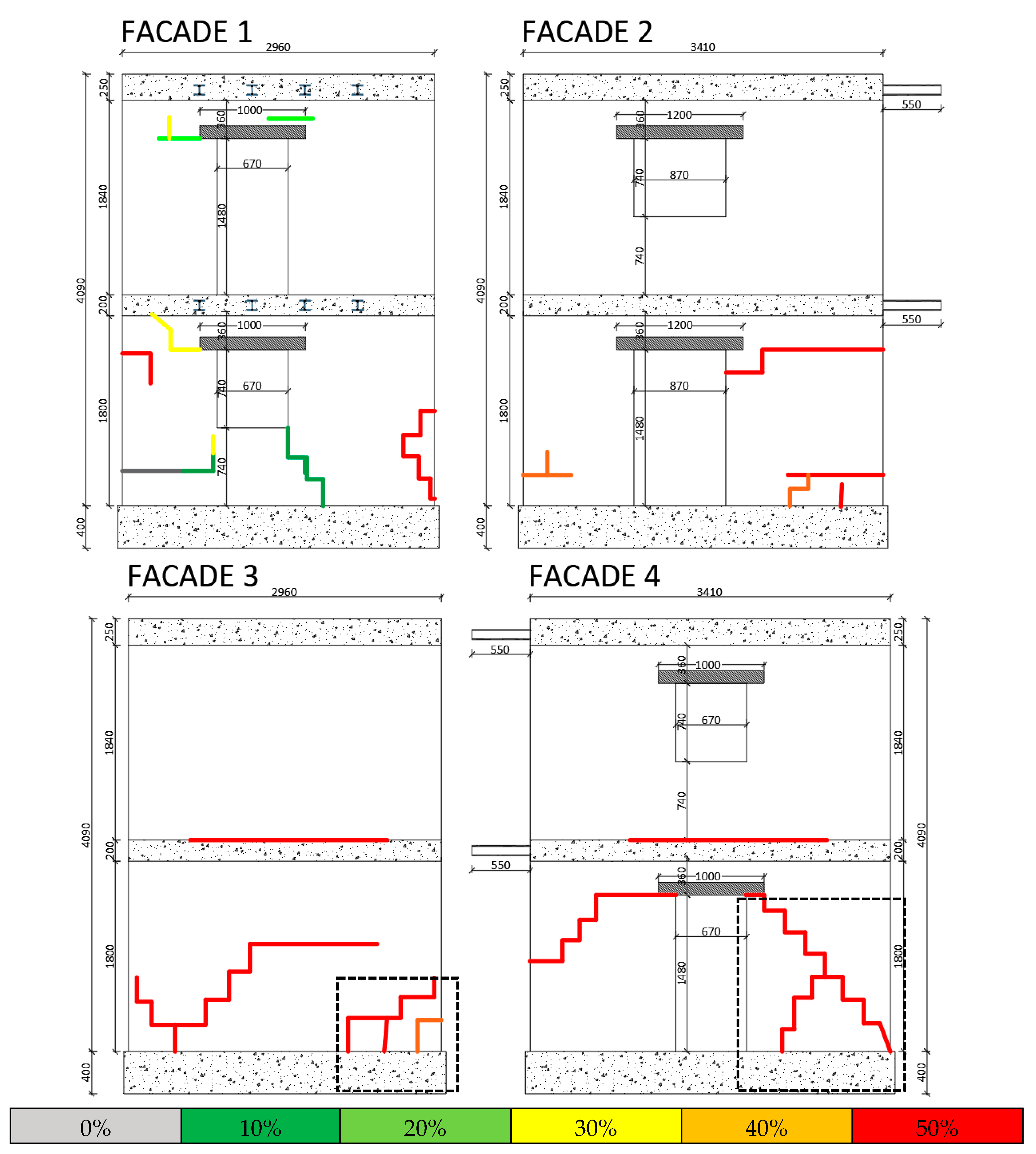

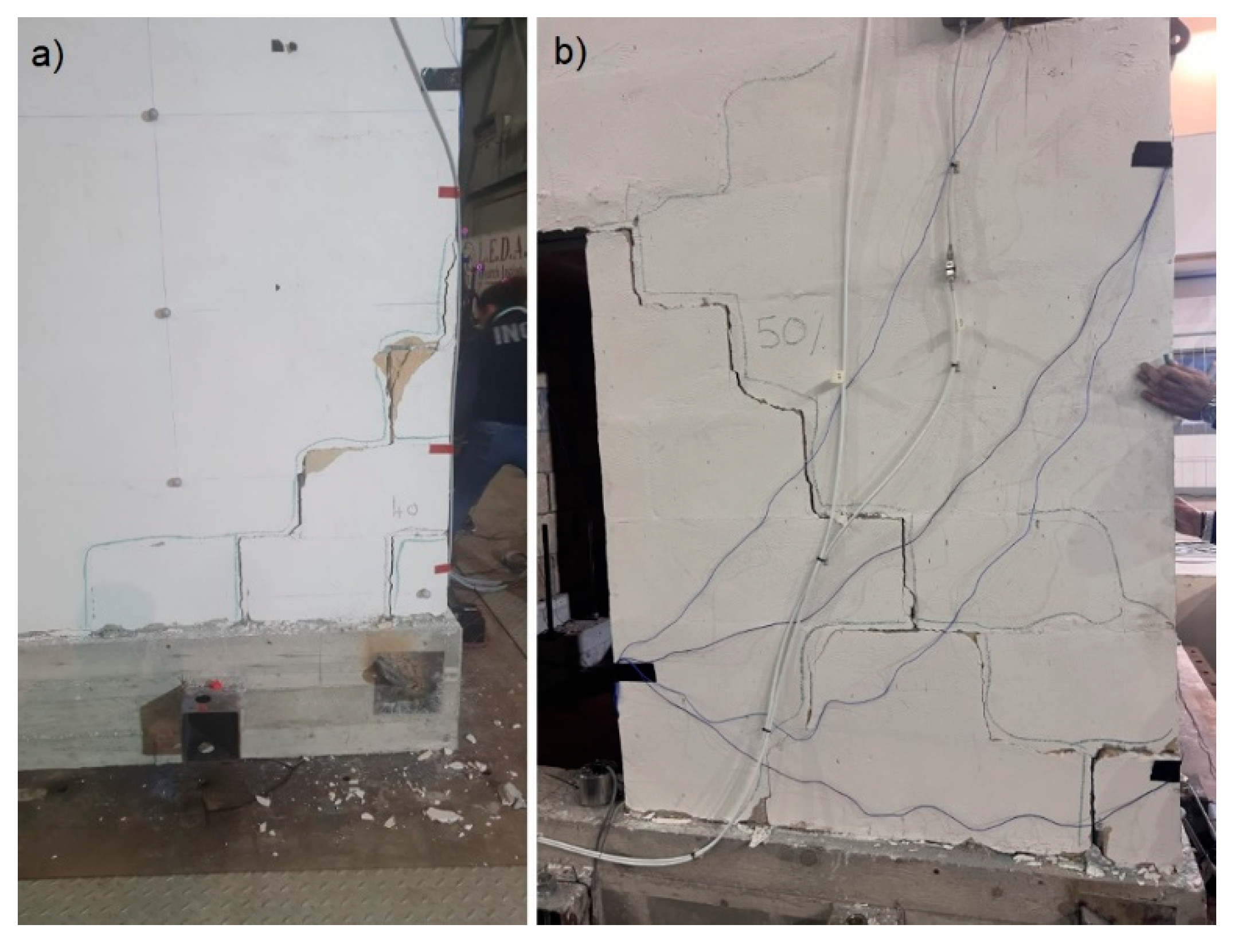

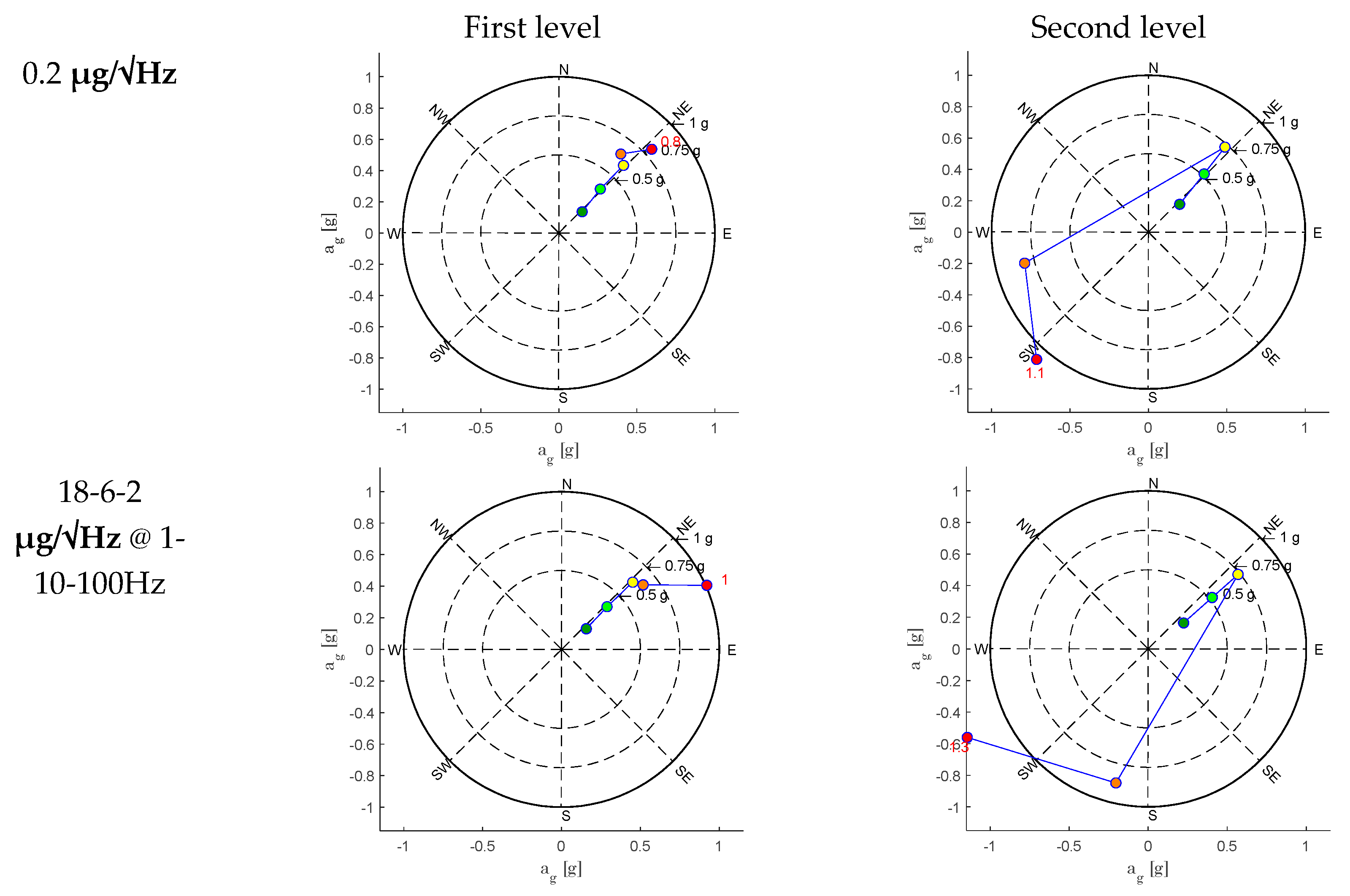

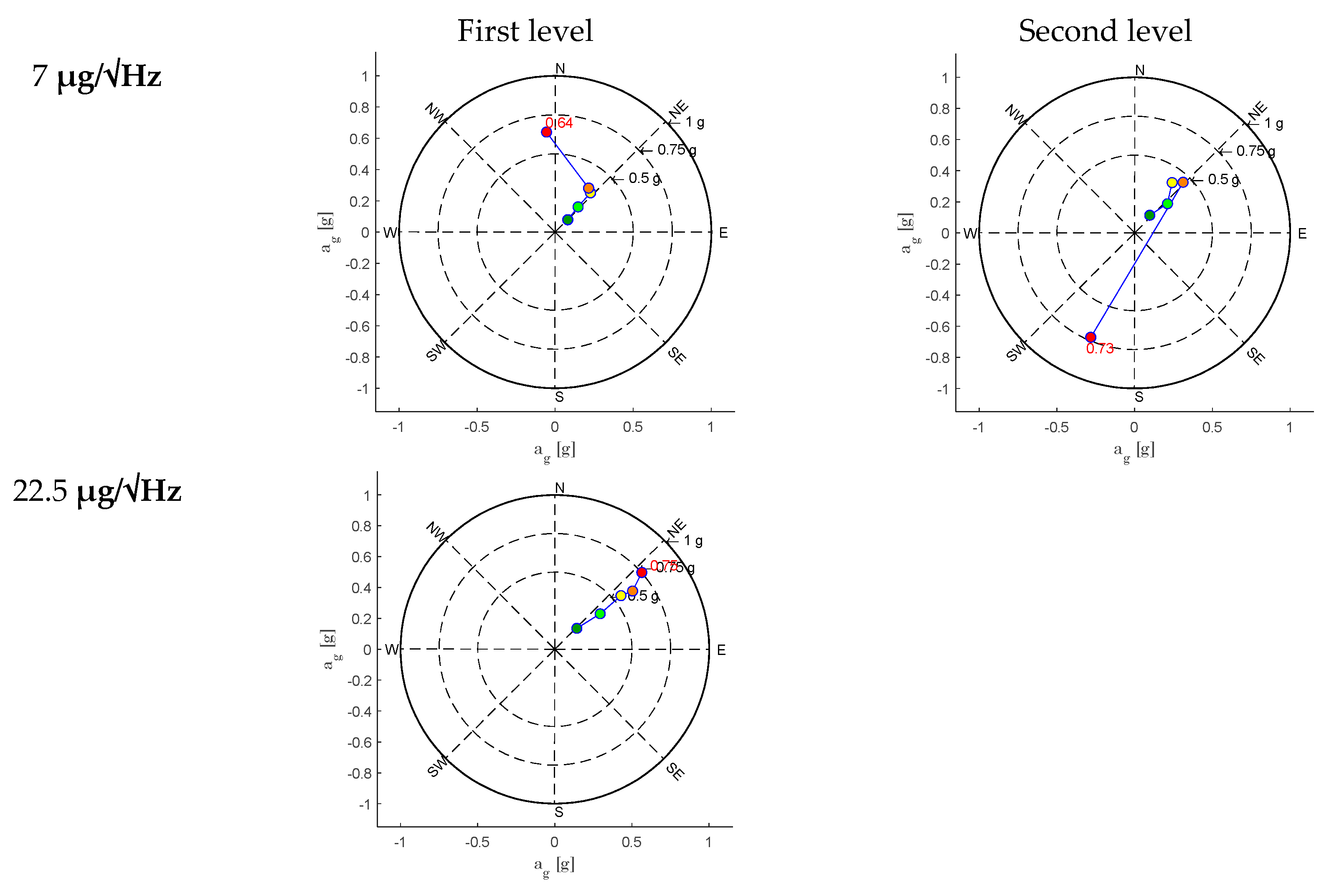

- The acceleration response maintains the same proportion among the components for the first, second, and third loading steps. This aspect can be interpreted as an elastic response condition of the structure under incremental loads. From this step onwards, and more evidently in the subsequent step, the maximum recorded acceleration shows significant variations in orientation. This phenomenon may be related to the disassembly of the masonry structure due to damage. This is consistent with the conditions observed during the experimental test, where cracking patterns emerged from the fourth loading step. The crack pattern survey, conducted after each experimental test and reported in Figure 16, illustrates that at the fourth step (40% of the load), large cracks corresponding to the vertical alignment of station M5 are evident. In the subsequent step (50%), a widespread crack pattern significantly affects the in-plane resistance of the panel and, in general, the masonry piers. This results in higher out-of-plane accelerations.

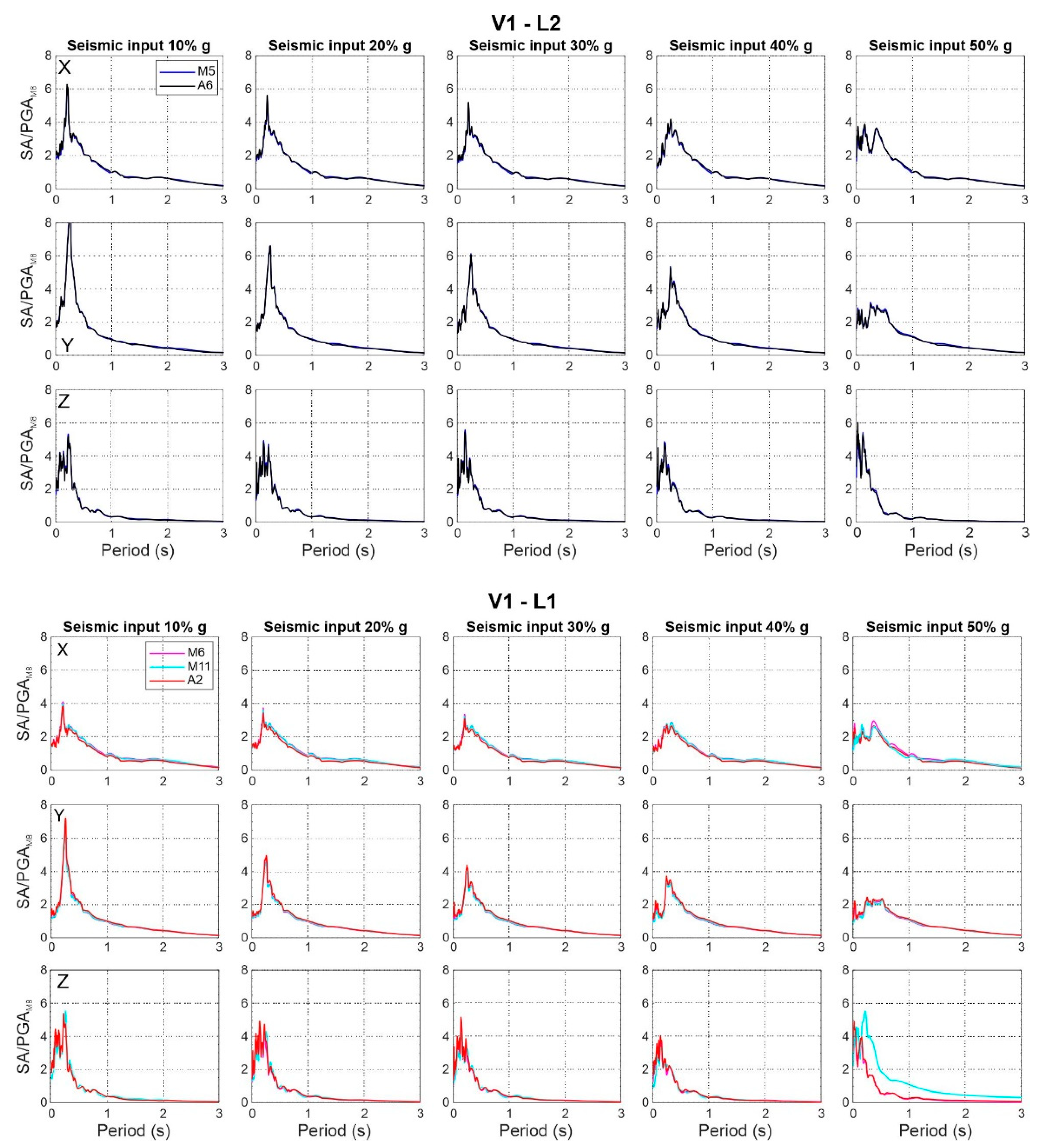

- It is evident that the amplification of motion with respect to the ground decreases as the intensity of the seismic input increases, suggesting a progressive change in the structure’s damping behaviour. The height and sharpness of the peaks in the normalized response spectra decrease, suggesting a change in the structure’s ability to dissipate seismic energy, potentially indicating higher damping.

- The eccentricity between mass and stiffness centres due to the presence of solid walls (Facade3), led to an unequally distributed damage pattern. This response closely mirrors real cases, where structural irregularities lead to the damage of the structural elements with different mechanism. As a result, shear and flexural failures of the masonry walls define the damaging at 50% of the target input level. The damage significantly affected the specimen’s dynamic behaviour, as identified by most of the sensors. It is worth noting that some differences have been identified in the acceleration peaks captured by each sensor type.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clementi, F.; Formisano, A.; Milani, G.; Ubertini, F. Structural Health Monitoring of Architectural Heritage: From the past to the Future Advances. International Journal of Architectural Heritage 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patanè, D.; Yang, W.; Occhipinti, G.; Cannizzaro, F.; Oriti, C.; Caliò, I. MonVia Project, development and application of a new sensor box. In IOMAC 2024, Napoli, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Farrar, C.R.; Worden, K. Structural Health Monitoring – A machine learning perspective, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2013.

- Iacono, F.L.; Navarra, G.; Oliva, M. Structural monitoring of “Himera” viaduct by low-cost MEMS sensors: characterization and preliminary results. Meccanica 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rainieri, C.; Fabbrocino, G. Operational Modal Analysis of Civil Engineering Structures - An Introduction and Guide for Applications. Springer, 2014.

- Friswell, M.; Mottershead, J.E. Finite element model updating in structural dynamics. Springer Science & BusinessMedia, 1995. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Iacono, F.L.; Navarra, G.; Orlando, C.; Ricciardello, A. Continuous particle swarm optimization for model updatingof structures from experimental modal analysis. Materials Research Proceedings 2023, 26, 467–472. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.F.; Luo, Z.-C.; Hu, Z.-K.; Yang, S.-Q.; Tu, L.-C.; Zhou, Z.-B.; Kraft, M. A review of high-performance MEMS sensors for resource exploration and geophysical applications. Petroleum Science 2022, 19, 2631–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Fu, Y.; Chow, R.; Spencer, B.; Park, J.; Mechitov, K. Development of a High-Sensitivity Wireless Accelerometer for Structural Health Monitoring. Sensors 2018, 18, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fertitta, G.; Yang, W.; Costanza, A.; Martino, C.; Macaluso, F.; Patanè, D. Design and test of a Smart Sensor Box for structural and seismological monitoring with a high-performance QMEMS accelerometer. in 2024 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Industry 4.0 & IoT (MetroInd4.0 & IoT), Firenze, Italy, 2024.

- Ribeiro, R.R. Lameiras. Evaluation of low-cost MEMS accelerometers for SHM: frequency anddamping identification of civil structures. Latin American Journal of Solids and Structures 2019, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Longo, Analisi dimensionale e Modellistica Fisica. Principi e applicazioni alle scienze ingegneristiche, Springer, 2011.

- Fossetti, M.; Iacono, F.L.; Minafò, G.; Navarra, G.; Tesoriere, G. A new large scale laboratory: The LEDA research centre (Laboratory of Earthquake engineering and Dynamic Analysis). In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advances in Experimental Structural Engineering (AESE 2017), Pavia, Italy, 2017.

- Iacono, F.L.; Navarra, G.; Oliva, M.; Cascone, D. Experimental investigation of the dynamic performances of the LEDA shaking tables system. In Proceedings of the AIMETA 2017—Proceedings of the 23rd Conference of the Italian Association of Theo-retical, 2017.

- Barone, G.; Iacono, F.L.; Navarra, G.; Palmeri, A. A novel analytical model of power spectral density function coherent with earthquake response spectra. In UNCECOMP 2015 - 1st ECCOMAS Thematic Conference on Uncertainty Quantification in Computational Sciences and Engineering, Hersonissos, Crete, Greece, 2015.

- Cacciola, P. A stochastic approach for generating spectrum compatible fully nonstationary earthquakes. Computers and Structures 2010, 88, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, J.; Kana, D. An iterative procedure for the generation of consistent power/response spectrum. Nuclear Engineering and Design 1981, 66, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNI ENV 1998: 2005. Eurocode 8: Design of Structures for Earthquake Resistance Part 1: General Rules, Seismic Actions and Rules for Buildings. CEN Central Secretariat Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- Pentaris, F.P. A novel horizontal to vertical spectral ratio approach in a wired structural health monitoring system. J. Sens. Sens. Syst. 2014, 3, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisidi, M.; Vallianatos, F.; Gallipoli, M. Assessing the Main Frequencies of Modern and Historical Buildings Using Ambient Noise Recordings: Case Studies in the Historical Cities of Crete (Greece). Heritage 2018, 1, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathelet, M.; Chatelain, J.; Cornou, C.; Giuseppe, D.G.; Guillier, B.; Ohrnberger, M.; Savvaidis, A. Geopsy: A User-Friendly Open-Source Tool Set for Ambient Vibration Processing. Seismological Research Letters 2020, 91, 1878–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alguhane, T.M.; Fayed, M.N.; Hussin, A.; Ismail, A.M. Simplified Equations For Estimating The Period Of Vibration Of Ksa Existing Building Using Ambient vibration testing. Journal of Multidisciplinary Engineering Science and Technology 2016, 3, 4335–4343. [Google Scholar]

- NTC18. NTC Normativa tecnica per le costruzionii - DM 14 Gennaio 2018. Ministero delle Infrastrutture e dei Trasporti, 2018.

- A. S. o. C. E. Standard Committee. ASCE/SEI 7-05: Minimum design loads for buildings and other structures. Reston, Virginia, 2005.

- van Overschee, P.; De Moor, B. Subspace identification for linear systems – Theory, Implementation, Applications. Kluwer academic Publishers, 1996.

- SVIBS. ARTeMIS Modal Help V3. SVIBS.

- Stockwell, R.; Mansinha, L.; Lowe, R. Localization of the complex spectrum: the S transform. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 1996, 44, 998–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianese, G.; Petrovic, B.; Parolai, S.; Paolucci, R. Identification of the nonlinear seismic response of buildings by a combined Stockwell Transform and deconvolution interferometry approach. Bull Earthquake Eng 2018, 16, 3103–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditommaso, R.; Iacovino, C.; Auletta, G.; Parolai, S.; Ponzo, F. Damage Detection and Localization on Real Structures Subjected to Strong Motion Earthquakes Using the Curvature Evolution Method: The Navelli (Italy) Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Masses | Floor 1 [kg] |

Floor 2 [kg] |

Balconies [kg] |

|---|---|---|---|

| G1 prototype | 10659 | 7223 | 65 |

| G1 model | 7106 | 4815 | 43 |

| Additional mass G1 | 3553 | 2408 | 22 |

| 50% of (G2+Q) | 1192 | 746 | 191 |

| Total additional mass | 4745 | 3154 | 213 |

| Actual additional mass | 4809 | 3150 | 221 |

| System characteristics | Single Tables (each) | Connected Tables |

|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | 4 x 4 m | 10 x 4 m |

| Nominal maximum payload | 60 t | 100 t |

| Frequency range | 0.01 ÷ 60 Hz | 0.01 ÷ 60 Hz |

| Max displacement | X and Y: ±0.4 m, Z: ±0.25 m | X and Y: ±0.4 m, Z: ±0.25 m |

| Max velocity | X and Y: ±2.2 m/s, Z: ±1.5 m/s | X and Y: ±1.1 m/s, Z: ±0.75 m/s |

| Max acceleration (at max. payload) | X and Y: ±1.5 g, Z: ±1.0 g | X and Y: ±1.05 g, Z: ±0.7 g |

| Company | Product | Type | N. of axes | Noise Floor [µg/ √ Hz] | Sensitivity [mV/g] | Sensitivity [µg/LSB] | Full Scale Range Dynamic Range | Bandwidth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seiko-Epson | M-A352(1) | Digital 32-bit MEMS | 3 | 0.2 at 0.5-30 Hz | 0.06 | ± 15 g > 140 dB | 0-460 Hz | |

| Safran- Colybris | SI1003 | Analog MEMS | 1 | 0.7 | 900 | ± 3 g 108.5 dB (0.1-100 Hz) | 0-500 Hz | |

| Safran- Colybris | VS1002(1) | Analog MEMS | 1 | 7 | 10000 | ± 2 g 108.5 dB (0.1-100 Hz) | 0-700 Hz | |

| Analog Device | ADXL355(1) | Digital 20-bit MEMS | 3 | 22.5 Hz at ± 2 g |

3.9 at ± 2 g | ± 2 g to ± 8 g ~ 90 dB (± 2 g) | 1-1000 Hz | |

| PCB Piezotronics | 3711B1110G (2) | Analog MEMS | 1 | 107.9 | 1000 | ± 10 g | 0-1000 Hz | |

| PCB Piezotronics | 393B04(1) | Analog Piezoelectric | 1 | 0.3 at 1 Hz 0.1 at 10 Hz |

1000 | ± 5 g | 0.06-450 Hz | |

| PCB Piezotronics | T333B50(1) | Analog Piezoelectric | 1 | 15 at 1 Hz 3.8 at 10 Hz 1.1 at 100 Hz |

1000 | ± 5 g | 0.5-3000 Hz | |

| PCB Piezotronics | 356A17(1) | Analog Piezoelectric | 3 | 18 at 1 Hz 6 at 10 Hz 2 at 100 Hz |

500 | ± 10 g | 0.5-3000 Hz | |

| Kinemetrics | Episensor ES-T | Force Balance | 3 | 0.06 at 1 Hz (± 0.25 g) | 10000 | ± 0.25 g to ± 4 g 155 dB |

DC-200 Hz |

| Graphical representation | Station Code | F | L | V | Model | Sampling rate [Hz] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

M1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | M-A352 | 200 |

| M2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | M-A352 | 200 | |

| M3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | M-A352 | 200 | |

| M4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | M-A352 | 200 | |

| M5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | M-A352 | 200 | |

| M6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | M-A352 | 200 | |

| M7 | 3 | 1 | 2 | M-A352 | 200 | |

| M8 | - | 0 | - | M-A352 | 200 | |

| M9 | 1 | 2 | 4 | M-A352 | 200 | |

| M10 | 2 | 1 | 2 | ADXL355 | 125 | |

| M11 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ADXL355 | 125 | |

| M12 | - | 0 | - | ADXL355 | 125 | |

| W1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | VS1002 | 1000 | |

| W2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | VS1002 | 1000 | |

| W3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | VS1002 | 1000 | |

| W4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | VS1002 | 1000 | |

| W5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | VS1002 | 1000 | |

| W6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | VS1002 | 1000 | |

| W7 | 4 | 2 | 3 | VS1002 | 1000 | |

| W8 | 4 | 2 | 4 | VS1002 | 1000 | |

| A1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 356A17 | 1000 | |

| A2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 356A17 | 1000 | |

| A3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 356A17 | 1000 | |

| A4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 356A17 | 1000 | |

| A5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 356A17 | 1000 | |

| A6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 356A17 | 1000 | |

| A7 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 356A17 | 1000 | |

| A8 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 356A17 | 1000 | |

| F2 | 2 | 1 | - | T333B50 | 1000 | |

| F3 | 3 | 1 | - | T333B50 | 1000 | |

| F4 | 4 | 1 | - | T333B50 | 1000 | |

| F6 | 2 | 2 | - | T333B50 | 1000 | |

| F7 | 3 | 2 | - | T333B50 | 1000 | |

| F8 | 4 | 2 | - | T333B50 | 1000 | |

| S1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 393B04 | 1000 | |

| S2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 393B04 | 1000 | |

| AccGDL | - | Shake table | - | 3711B1110G | 1000 |

| Type of excitation | Intensity [g] |

Direction |

|---|---|---|

| WN | 0.03 | X |

| WN | 0.04 | X |

| WN | 0.03 | Y |

| WN | 0.04 | Y |

| WN | 0.015 | Z |

| WN | 0.03 | Z |

| WN | 0.04 | XYZ |

| EQ | 0.05 | XYZ |

| WN | 0.03 | XYZ |

| EQ | 0.1 | XYZ |

| WN | 0.03 | XYZ |

| EQ | 0.2 | XYZ |

| WN | 0.03 | XYZ |

| EQ | 0.3 | XYZ |

| WN | 0.03 | XYZ |

| EQ | 0.4 | XYZ |

| WN | 0.03 | XYZ |

| EQ | 0.5 | XYZ |

| WN | 0.03 | XYZ |

| Formula | C | a | Fundamental Frequency f [Hz] | |

| Alguhane et al. [22] (D=2.96m) | 0.07 | 0.5 | 6.00 | |

| Alguhane et al. [22] (D=3.41m) | 0.07 | 0.5 | 6.45 | |

| EUROCODE 8 [18] - NTC18 [23] | 0.05 | 0.75 | 6,95 | |

| ASCE 7-10 [24] | 0.0488 | 0.75 | 7,12 | |

| Alguhane et al. [22] | 0.042 | 0.75 | 8.28 |

| Chunk of data | Frequency f1 [Hz] | Damping [%] | Complexity [%] |

| 01_R1345_1355 | 6.98 | 4.44 | 4.34 |

| Seismic action at 10% of the PGA max | |||

| 04_R1407_1417 | 6.46 | 8.05 | 17.47 |

| Seismic action at 20% of the PGA max | |||

| 07_R1433_1444 | 6.44 | 6.30 | 33.61 |

| Seismic action at 30% of the PGA max | |||

| 09_R1445_1451 | 5.75 | 6.72 | 26.66 |

| Seismic action at 40% of the PGA max | |||

| 12_R1500_1505 | 5.001 | 0.207 | 23.868 |

| Seismic action at 50% of the PGA max | |||

| 15_R1514_1520 | 5.014 | 7.468 | 40.055 |

| Station Code | F | L | V | Noise density [µg/√Hz] | Sampling rate [Hz] | X | Y | Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.2 | 200 | z | x | y |

| M5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.2 | 200 | z | x | y |

| W1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 1000 | x | y | - |

| W5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 1000 | x | y | - |

| M11 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 25 | 200 | x | -z | y |

| A2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 18-6-2 @ 1-10-100Hz | 1000 | X | Y | Z |

| A6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 18-6-2 @ 1-10-100Hz | 1000 | X | Y | Z |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).